Submitted:

17 July 2023

Posted:

18 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.4. Analytical strategies

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Preliminary analyses

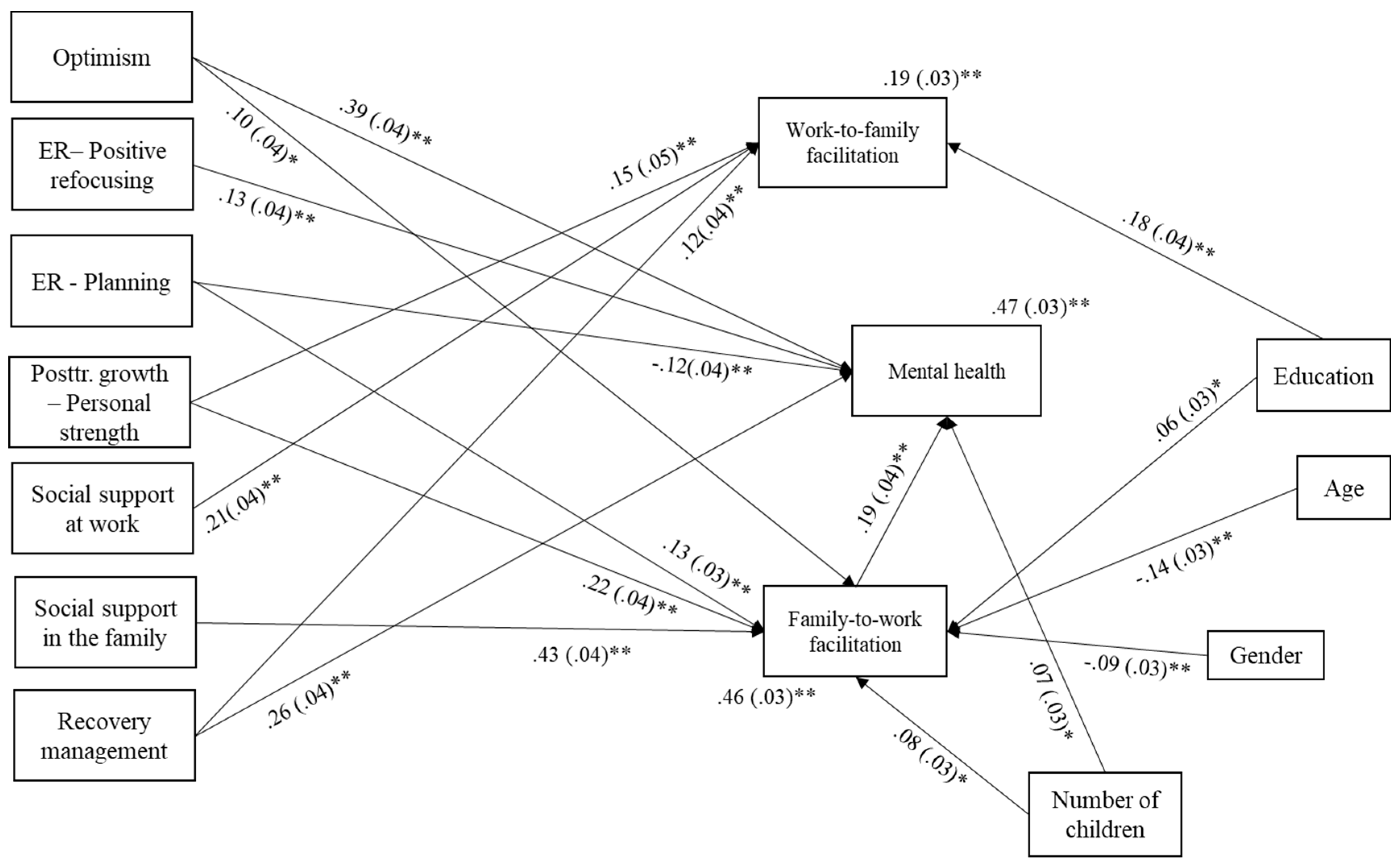

3.2. Testing the hypothesized model

Interpreting the model results

4. Discussion

4.1. Predicting work-to-family and family-to-work facilitation in parents of children with disabilities in Croatia

4.2. Predicting mental health in parents of children with disabilities in Croatia and the mediational role of work-to-family and family-to-work facilitation

4.3. Limitations and future research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mental Health Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response (accessed on 6 July 2023).

- Ionio, C.; Colombo, C.; Brazzoduro, V.; Mascheroni, E.; Confalonieri, E.; Castoldi, F.; Lista, G. Mothers and Fathers in NICU: The Impact of Preterm Birth on Parental Distress. Europe’s Journal of Psychology 2016, 12, 604–621. [CrossRef]

- Starc, B. Parenting in the Best Interests of the Child and Support to Parents | UNICEF Available online: https://www.unicef.org/croatia/en/reports/parenting-best-interests-child-and-support-parents (accessed on 6 July 2023).

- Gérain, P.; Zech, E. Does Informal Caregiving Lead to Parental Burnout? Comparing Parents Having (or Not) Children With Mental and Physical Issues. Front Psychol 2018, 9, 884. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, L.M.; Sellmaier, C.; Brannan, A.M.; Brennan, E.M. Employed Parents of Children with Typical and Exceptional Care Responsibilities: Family Demands and Workplace Supports. J Child Fam Stud 2023, 32, 1048–1064. [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.J.; Clark, C. Employed Parents of Children with Disabilities and Work Family Life Balance: A Literature Review. Child Youth Care Forum 2017, 46, 857–876. [CrossRef]

- Morris, L.A. The Impact of Work on the Mental Health of Parents of Children with Disabilities. Family Relations 2014, 63, 101–121. [CrossRef]

- Bulger, C.A.; Hoffman, M.E. Segmentation/Integration of Work and Nonwork Domains: Global Considerations. In The Cambridge handbook of the global work–family interface; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, US, 2018; pp. 701–719 ISBN 978-1-108-40126-5.

- Lewis, S.; Beauregard, T.A. The Meanings of Work–Life Balance: A Cultural Perspective. In The Cambridge Handbook of the Global Work–Family Interface; Shockley, K.M., Johnson, R.C., Shen, W., Eds.; Cambridge Handbooks in Psychology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2018; pp. 720–732 ISBN 978-1-108-41597-2.

- Williams, J.C.; Berdahl, J.L.; Vandello, J.A. Beyond Work-Life “Integration.” Annu Rev Psychol 2016, 67, 515–539. [CrossRef]

- Slišković, A.; Tokić, A.; Šimunić, A.; Ombla, J.; Nikolić Ivanišević, M. Dobrobit Zaposlenih Roditelja Djece s Teškoćama u Razvoju: Pregled Dosadašnjih Spoznaja, Smjernice Za Daljnja Istraživanja i Praktične Implikacije. Contemp. psychol. 25, 47–69.

- Mahmic, S.; Kern, M.L.; Janson, A. Identifying and Shifting Disempowering Paradigms for Families of Children With Disability Through a System Informed Positive Psychology Approach. Front Psychol 2021, 12, 663640. [CrossRef]

- Wehmeyer, M.L. The Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology and Disability. Oxford Library of Psychology; Oxford University Press, 2013; ISBN 978-0-19-539878-6.

- Beighton, C.; Wills, J. How Parents Describe the Positive Aspects of Parenting Their Child Who Has Intellectual Disabilities: A Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil 2019, 32, 1255–1279. [CrossRef]

- Lodewyks, M.R. Parent and Child Perceptions of the Positive Effects That a Child with a Disability Has on the Family, University of Manitoba, 2009.

- Lodewyks, M.R. Positive Impacts of Children with Disabilities. Transition 2015, 45.

- Manor-Binyamini, I. Positive Aspects of Coping among Mothers of Adolescent Children with Developmental Disability in the Druze Community in Israel. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability 2016, 41, 97–106. [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, J.P.; Oliver, M.; Yashar, B.M. Rewards and Challenges of Parenting a Child with Down Syndrome: A Qualitative Study of Fathers’ Perceptions. Disability and Rehabilitation 2021, 43, 3562–3573. [CrossRef]

- Strecker, S.; Hazelwood, Z.J.; Shakespeare-Finch, J. Postdiagnosis Personal Growth in an Australian Population of Parents Raising Children with Developmental Disability. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability 2014, 39, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Shakespeare-Finch, J.; Taku, K.; Calhoun, L.G. Components of the Theoretical Model of Posttraumatic Growth. In Posttraumatic Growth; Routledge, 2018 ISBN 978-1-315-52745-1.

- Janoff-Bulman, R. Posttraumatic Growth: Three Explanatory Models. Psychological Inquiry 2004, 15, 30–34.

- Stewart, M.; Knight, T.; McGillivray, J.; Forbes, D.; Austin, D.W. Through a Trauma-Based Lens: A Qualitative Analysis of the Experience of Parenting a Child with an Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability 2017, 42, 212–222. [CrossRef]

- Counselman-Carpenter, E.A. The Presence of Posttraumatic Growth (PTG) in Mothers Whose Children Are Born Unexpectedly with Down Syndrome. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability 2017, 42, 351–363. [CrossRef]

- Young, S.; Shakespeare-Finch, J.; Obst, P. Raising a Child with a Disability: A One-Year Qualitative Investigation of Parent Distress and Personal Growth. Disability & Society 2019, 35, 629–653. [CrossRef]

- Barnett, D.; Clements, M.; Kaplan-Estrin, M.; Fialka, J. Building New Dreams: Supporting Parents’ Adaptation to Their Child With Special Needs. Infants & Young Children 2003, 16, 184.

- Krakovich, T.; Mcgrew, J.; Yu, Y.; Ruble, L. Stress in Parents of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: An Exploration of Demands and Resources. Journal of autism and developmental disorders 2016, 46. [CrossRef]

- Gérain, P.; Zech, E. Informal Caregiver Burnout? Development of a Theoretical Framework to Understand the Impact of Caregiving. Front Psychol 2019, 10, 1748. [CrossRef]

- Tahmouresi, N.; Bender, C.; Schmitz, J.; Baleshzar, A.; Tuschen-Caffier, B. Similarities and Differences in Emotion Regulation and Psychopathology in Iranian and German School-Children: A Cross-Cultural Study. Int J Prev Med 2014, 5, 52–60.

- Garnefski, N.; Kraaij, V. Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire - Development of a Short 18-Item Version (CERQ-Short). Personality and Individual Differences 2006, 41, 1045–1053. [CrossRef]

- Woodman, A.C.; Hauser-Cram, P. The Role of Coping Strategies in Predicting Change in Parenting Efficacy and Depressive Symptoms among Mothers of Adolescents with Developmental Disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 2013, 57, 513–530. [CrossRef]

- Craig, A.; Cooper, R.E. 11 - Symptoms of Acute and Chronic Fatigue. In State and Trait; Smith, A.P., Jones, D.M., Eds.; Academic Press: London, 1992; pp. 289–339 ISBN 978-0-12-650353-1.

- Headrick, L.; Newman, D.A.; Park, Y.A.; Liang, Y. Recovery Experiences for Work and Health Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis and Recovery-Engagement-Exhaustion Model. J Bus Psychol 2023, 38, 821–864. [CrossRef]

- Geurts, S.A.E.; Sonnentag, S. Recovery as an Explanatory Mechanism in the Relation between Acute Stress Reactions and Chronic Health Impairment. Scand J Work Environ Health 2006, 32, 482–492. [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B.S. Stress, Adaptation, and Disease. Allostasis and Allostatic Load. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1998, 840, 33–44. [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S.; Fritz, C. The Recovery Experience Questionnaire: Development and Validation of a Measure for Assessing Recuperation and Unwinding from Work. J Occup Health Psychol 2007, 12, 204–221. [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, S.; Venz, L.; Casper, A. Advances in Recovery Research: What Have We Learned? What Should Be Done Next? J Occup Health Psychol 2017, 22, 365–380. [CrossRef]

- Ombla, J.; Slišković, A.; Nikolić Ivanišević, M.; Šimunić, A.; Ljubičić, M. Kako zaposleni roditelji djece s teškoćama u razvoju usklađuju zahtjeve radne i obiteljske uloge?: Kvalitativno istraživanje. Rev. sociol. (Online) 2023, 53, 67–97. [CrossRef]

- Kurtz-Nelson, E.; McIntyre, L.L. Optimism and Positive and Negative Feelings in Parents of Young Children with Developmental Delay. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 2017, 61, 719–725. [CrossRef]

- Rafferty, D.; preston, M.; Sullivan, W.; Ekas, N. Chaotic Family Environments and Depressive Symptoms in Parents of Autistic Children: The Protective Role of Optimism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 2022, 96, 102000. [CrossRef]

- Khusaifan, S.J.; El Keshky, M.E.S. Social Support as a Protective Factor for the Well-Being of Parents of Children with Autism in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Pediatric Nursing 2021, 58, e1–e7. [CrossRef]

- Hill, E.J. Work-Family Facilitation and Conflict, Working Fathers and Mothers, Work-Family Stressors and Support. Journal of Family Issues 2005, 26, 793–819. [CrossRef]

- Holmes, E.K.; Thomas, C.R.; Petts, R.J.; Hill, E.J. Chapter 10 - The Work-Family Interface. In Cross-Cultural Family Research and Practice; Halford, W.K., van de Vijver, F., Eds.; Academic Press, 2020; pp. 323–354 ISBN 978-0-12-815493-9.

- Frone, M.R. Work-Family Balance. In Handbook of occupational health psychology; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, US, 2003; pp. 143–162 ISBN 978-1-55798-927-7.

- Grzywacz, J.G.; Bass, B.L. Work, Family, and Mental Health: Testing Different Models of Work-Family Fit. Journal of Marriage and Family 2003, 65, 248–261.

- Wayne, J.H.; Grzywacz, J.G.; Carlson, D.S.; Kacmar, K.M. Work–Family Facilitation: A Theoretical Explanation and Model of Primary Antecedents and Consequences. Human Resource Management Review 2007, 17, 63–76. [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Bekteshi, L. Antecedents and Outcomes of Work–Family Facilitation and Family–Work Facilitation among Frontline Hotel Employees. International Journal of Hospitality Management 2008, 27, 517–528. [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, M.; Mahajan, R. The Effect of Optimism on the Work-Family Interface and Psychological Health of Indian Police. Policing: An International Journal 2021, 44, 725–740. [CrossRef]

- Wepfer, A.G.; Allen, T.D.; Brauchli, R.; Jenny, G.J.; Bauer, G.F. Work-Life Boundaries and Well-Being: Does Work-to-Life Integration Impair Well-Being through Lack of Recovery? J Bus Psychol 2018, 33, 727–740. [CrossRef]

- Rotondo, D.M.; Kincaid, J.F. Conflict, Facilitation, and Individual Coping Styles across the Work and Family Domains. Journal of Managerial Psychology 2008, 23, 484–506. [CrossRef]

- Al-Yagon, M.; Cinamon, R.G. Work–Family Relations among Mothers of Children with Learning Disorders. European Journal of Special Needs Education 2008, 23, 91–107. [CrossRef]

- Parchomiuk, M. Work-Family Balance and Satisfaction with Roles in Parents of Disabled Children. Community, Work & Family 2022, 25, 353–373. [CrossRef]

- Slišković, A. Kratki upitnik mentalnog zdravlja. In Zbirka psihologijskih skala i upitnika, svezak 10; Ćubela-Adorić, V., Burić, I., Macuka, I., Nikolić Ivanišević, M., Slišković, A., Eds.; Morepress, 2020; pp. 27–38.

- Wayne, J.H.; Musisca, N.; Fleeson, W. Considering the Role of Personality in the Work–Family Experience: Relationships of the Big Five to Work–Family Conflict and Facilitation. Journal of Vocational Behavior 2004, 64, 108–130. [CrossRef]

- Buljan, T. Prediktori usklađivanja obiteljske i radne uloge za vrijeme pandemije koronavirusa. info:eu-repo/semantics/masterThesis, University of Zagreb. University of Zagreb, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences. Department of Psychology, 2020.

- Penezić, Z. SKALA OPTIMIZMA - PESIMIZMA (O-P skala). In Zbirka psihologijskih skala i upitnika, svezak 1; Lacković-Grgin, K., Proroković, A., Ćubela, V., Penezić, Z., Eds.; 2002; pp. 15–17.

- Chang, E.C.; D’Zurilla, T.J.; Maydeu-Olivares, A. Assessing the Dimensionality of Optimism and Pessimism Using a Multimeasure Approach. Cogn Ther Res 1994, 18, 143–160. [CrossRef]

- Garnefski, N.; Kraaij, V.; Spinhoven, P. Negative Life Events, Cognitive Emotion Regulation and Emotional Problems. Personality and Individual Differences 2001, 30, 1311–1327. [CrossRef]

- Soldo, L.; Vulić-Prtorić, A. Upitnik Kognitivne Emocionalne Regulacije (CERQ). In Zbirka psihologijskih skala i upitnika, svezak 9; Slišković, A., Burić, I., Ćubela-Adorić, V., Nikolić, M., Tucak Junaković, I., Eds.; Morepress, 2018; pp. 47–58.

- Macuka, I. Upitnik posttraumatskog rasta. In Zbirka psihologijskih skala i upitnika, Svezak 10; Ćubela-Adorić, V., Burić, I., Macuka, I., Nikolić Ivanišević, M., Slišković, A., Eds.; Morepress, 2020; pp. 121–130.

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Calhoun, L.G. The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: Measuring the Positive Legacy of Trauma. J Trauma Stress 1996, 9, 455–471. [CrossRef]

- Šimunić, A.; Gregov, L.; Proroković, A. Skala socijalne podrške na poslu i u obitelji. In Zbirka psihologijskih skala i upitnika 8; Tucak Junaković, I., Burić, I., Ćubela-Adorić, V., Proroković, A., Slišković, A., Eds.; Morepress, 2016; pp. 45–53.

- TIBCO® Data Science - Workbench 14.1.0 Available online: https://docs.tibco.com/products/tibco-data-science-workbench-14-1-0 (accessed on 6 July 2023).

- Mplus User’s Guide Available online: https://www.statmodel.com/html_ug.shtml (accessed on 6 July 2023).

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 1999, 6, 1–55. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. An Introduction to Structural Equation Modeling. In Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook; Hair Jr., J.F., Hult, G.T.M., Ringle, C.M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N.P., Ray, S., Eds.; Classroom Companion: Business; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 1–29 ISBN 978-3-030-80519-7.

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, Second Edition; Guilford Publications, 2005; ISBN 978-1-59385-075-3.

- Lapierre, L.M.; Li, Y.; Kwan, H.K.; Greenhaus, J.H.; DiRenzo, M.S.; Shao, P. A Meta-Analysis of the Antecedents of Work–Family Enrichment. Journal of Organizational Behavior 2018, 39, 385–401. [CrossRef]

- Stryzhak, O. The Relationship between Education, Income, Economic Freedom and Happiness. SHS Web Conf. 2020, 75, 03004. [CrossRef]

- Ratniewski, J. Antecedents of Work-Family Facilitation: The Role of Coping Styles, Organizational and Family Support, and Gender Role Attitudes. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering 2013, 74.

- Lapierre, L.M.; Allen, T.D. Control at Work, Control at Home, and Planning Behavior: Implications for Work–Family Conflict. Journal of Management 2012, 38, 1500–1516. [CrossRef]

- Penninx, B.W.J.H. A Happy Person, a Healthy Person? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2000, 48, 590–592. [CrossRef]

- Ciglar, J. Rodne razlike u ravnoteži između posla i obitelji i predikcija zadovoljstva životom. info:eu-repo/semantics/masterThesis, University of Zagreb. Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences. Department of Psychology, 2021.

- Kimura, M. Social Determinants of Self-Rated Health among Japanese Mothers of Children with Disabilities. Preventive Medicine Reports 2018, 10, 129–135. [CrossRef]

- Kimura, M.; Yamazaki, Y. Having Another Child without Intellectual Disabilities: Comparing Mothers of a Single Child with Disability and Mothers of Multiple Children with and without Disability. J Intellect Disabil 2019, 23, 216–232. [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F. Dispositional Optimism. Trends Cogn Sci 2014, 18, 293–299. [CrossRef]

- Laranjeira, C.; Querido, A. Hope and Optimism as an Opportunity to Improve the “Positive Mental Health” Demand. Front Psychol 2022, 13, 827320. [CrossRef]

- Bourke-Taylor, H.M.; Joyce, K.S.; Morgan, P.; Reddihough, D.S.; Tirlea, L. Maternal and Child Factors Associated with the Health-Promoting Behaviours of Mothers of Children with a Developmental Disability. Research in Developmental Disabilities 2021, 118, 104069. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S.; Willis, K.; Bismark, M.; Smallwood, N. A Time for Self-Care? Frontline Health Workers’ Strategies for Managing Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic. SSM - Mental Health 2021, 2, 100053. [CrossRef]

- Luis, E.; Bermejo-Martins, E.; Martinez, M.; Sarrionandia, A.; Cortes, C.; Oliveros, E.Y.; Garces, M.S.; Oron, J.V.; Fernández-Berrocal, P. Relationship between Self-Care Activities, Stress and Well-Being during COVID-19 Lockdown: A Cross-Cultural Mediation Model. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e048469. [CrossRef]

- Avasthi, A.; Sahoo, S. Impact, Role, and Contribution of Family in the Mental Health of Industrial Workers. Ind Psychiatry J 2021, 30, S301–S304. [CrossRef]

- Masten, A.S.; Coatsworth, J.D. The Development of Competence in Favorable and Unfavorable Environments. Lessons from Research on Successful Children. Am Psychol 1998, 53, 205–220. [CrossRef]

- Masten, A.S. Resilience Theory and Research on Children and Families: Past, Present, and Promise. Journal of Family Theory & Review 2018, 10, 12–31. [CrossRef]

- Hill, E.J.; Allen, S.; Jacob, J.; Bair, A.F.; Bikhazi, S.L.; Van Langeveld, A.; Martinengo, G.; Parker, T.T.; Walker, E. Work—Family Facilitation: Expanding Theoretical Understanding Through Qualitative Exploration. Advances in Developing Human Resources 2007, 9, 507–526. [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Descriptive parameters |

|---|---|

| Age | M=40.9, SD=6.15, Min=23 Max=66 |

| Education | Elementary school (N=4); Secondary school (N=237); Bachelor’s degree (N=90) Master’s degree (N=205) Doctoral degree (N=35) |

| Marital status | Extramarital union (N=57) Married (N=450) Separated or divorced (N=46) Single (N=14) Widow/er (N=4) |

| Number of children | Mode=2 (f=267), Min=1, Max=6 |

| Number of children with disabilities | Mode=1 (f=514); Min=1, Max=4 |

| Highest degree of disability among children | 4th ̊- most severe level of impairment (N=204) 3rd ̊ - severe level of impairment (N=158) 2nd ̊ - moderate level of impairment (N=70) 1st ̊ - mild level of impairment (N=35) Do not know/not sure (N=104) |

| Employment sector | Public (N=265) Private (N=306) |

| Partner's employment | Yes (N=463) No (N=24) Caregiver (N=20) |

| N | M | SD | Min | Max | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (0-men; 1-women) |

571 | 0.91 | 0.29 | 0.00 | 1.00 | -2.78 | 5.74 |

| Age | 564 | 40.90 | 6.15 | 23.00 | 66.00 | 0.27 | 0.24 |

| Education | 571 | 3.05 | 1.02 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 0.20 | -1.35 |

| Number of children | 571 | 2.20 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 6.00 | 1.05 | 1.57 |

| Optimism | 571 | 3.62 | 0.70 | 1.00 | 5.00 | -0.76 | 1.09 |

| Emotional regulation – Positive refocusing | 571 | 3.24 | 0.86 | 1.00 | 5.00 | -0.26 | -0.09 |

| Emotional regulation – Planning | 571 | 4.05 | 0.64 | 1.00 | 5.00 | -0.62 | 1.34 |

| Posttraumatic growth – Personal strength | 571 | 3.31 | 1.09 | 0.00 | 5.00 | -0.92 | 0.88 |

| Recovery management | 568 | 2.80 | 1.06 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 0.15 | -0.68 |

| Social support at work | 565 | 4.98 | 1.26 | 1.00 | 7.00 | -0.72 | 0.61 |

| Social support in the family | 566 | 5.27 | 1.27 | 1.25 | 7.00 | -0.66 | -0.15 |

| Work-to-family facilitation | 566 | 2.91 | 0.83 | 1.00 | 5.00 | -0.06 | -0.09 |

| Family-to-work facilitation | 563 | 3.41 | 0.82 | 1.00 | 5.00 | -0.27 | -0.03 |

| Mental health | 571 | 3.75 | 0.86 | 1.00 | 6.00 | -0.49 | 0.09 |

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (0-men; 1-women) |

-.10 | -.01 | -.04 | .04 | .04 | .06 | .05 | -.15 | -.00 | -.08 | .00 | -.09 | -.09 |

| Age | - | .10 | .12 | -.07 | -.04 | -.05 | -.05 | .09 | -.07 | -.08 | .01 | -.17 | -.04 |

| Education | - | -.15 | -.04 | -.10 | -.01 | -.10 | -.05 | .03 | -.00 | .15 | .00 | -.05 | |

| Number of children | - | .16 | .12 | .09 | .13 | .04 | .05 | .06 | -.02 | .13 | .17 | ||

| Optimism | - | .47 | .34 | .52 | .35 | .36 | .39 | .27 | .45 | .58 | |||

| ER – Positive refocusing | - | .19 | .38 | .23 | .16 | .20 | .17 | .26 | .40 | ||||

| ER – Planning | - | .26 | .05 | .13 | .15 | .11 | .29 | .11 | |||||

| PTG – Personal strength | - | .26 | .22 | .25 | .25 | .42 | .44 | ||||||

| Enjoying time for self | - | .32 | .38 | .26 | .29 | .46 | |||||||

| Social support at work | - | .48 | .33 | .35 | .29 | ||||||||

| Social support in the family | - | .18 | .56 | .42 | |||||||||

| Work-to-family facilitation |

- | .35 | .18 | ||||||||||

| Family-to-work facilitation |

- | .42 | |||||||||||

| Mental health | - |

| Model relationship | Standardized estimate (STDYX) | Standard error (STDYX) | Two-tailed p-value (STDYX) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-significant path coefficients | |||

| Optimism → Work-to-family facilitation | .090 | .050 | .084 |

| Work-to-family facilitation → Mental health | -0.073 | .037 | .051 |

| Indirect effects: | Non-standardized estimates of the indirect effect | 95% confidence interval (k=1000) |

|---|---|---|

| Optimism → Family-to-work facilitation → Mental health | 0.020 | 0.005 ; 0.046 |

| Emotional regulation: Planning → Family-to-work facilitation → Mental health | 0.042 | 0.019 ; 0.074 |

| Posttraumatic growth: Personal strength → Family-to-work facilitation → Mental health | 0.041 | 0.021 ; 0.069 |

| Social support in the family → Family-to-work facilitation → Mental health | 0.070 | 0.040 ; 0.105 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).