Submitted:

14 July 2023

Posted:

17 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

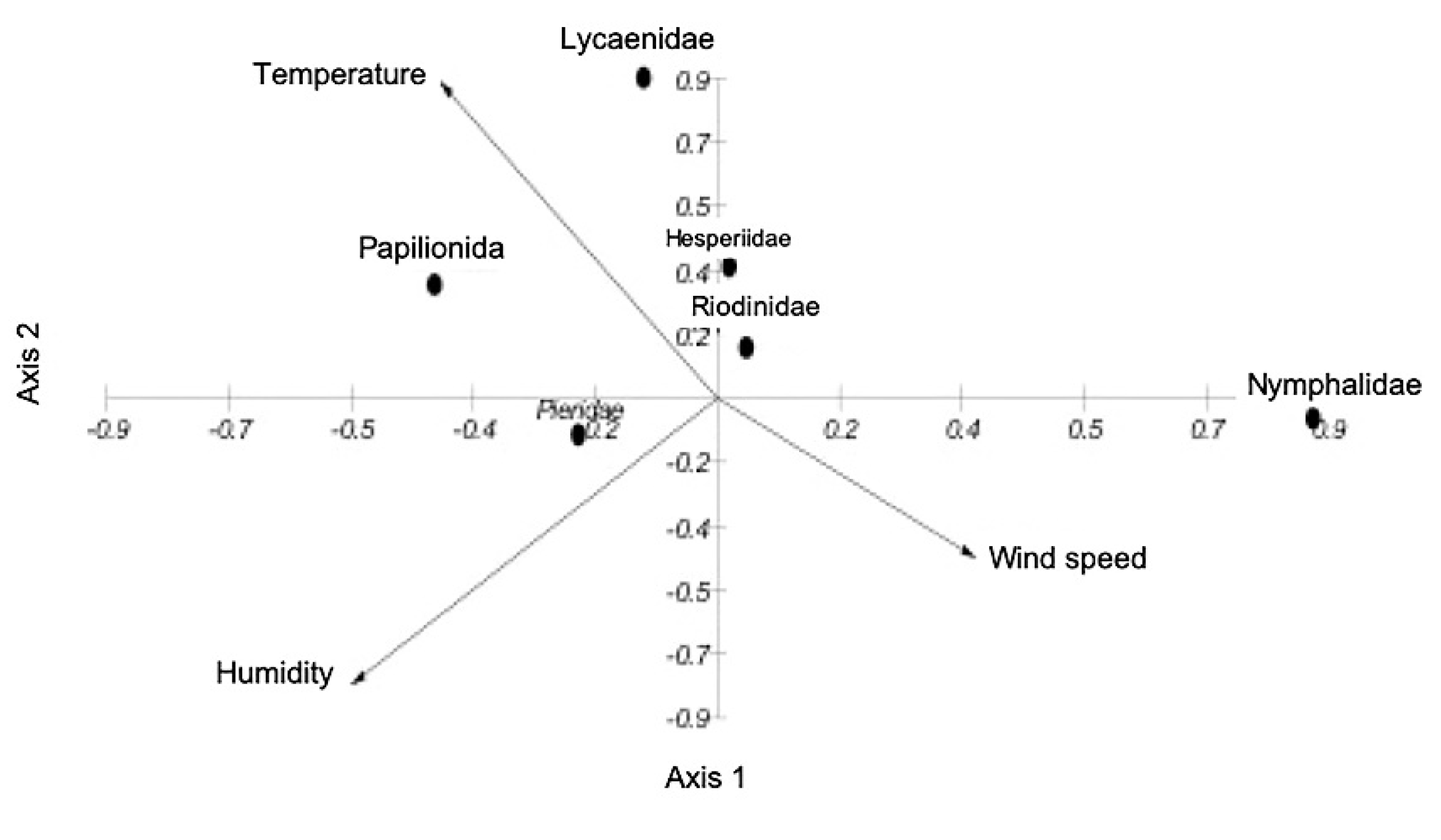

3.1. Abundance and diversity

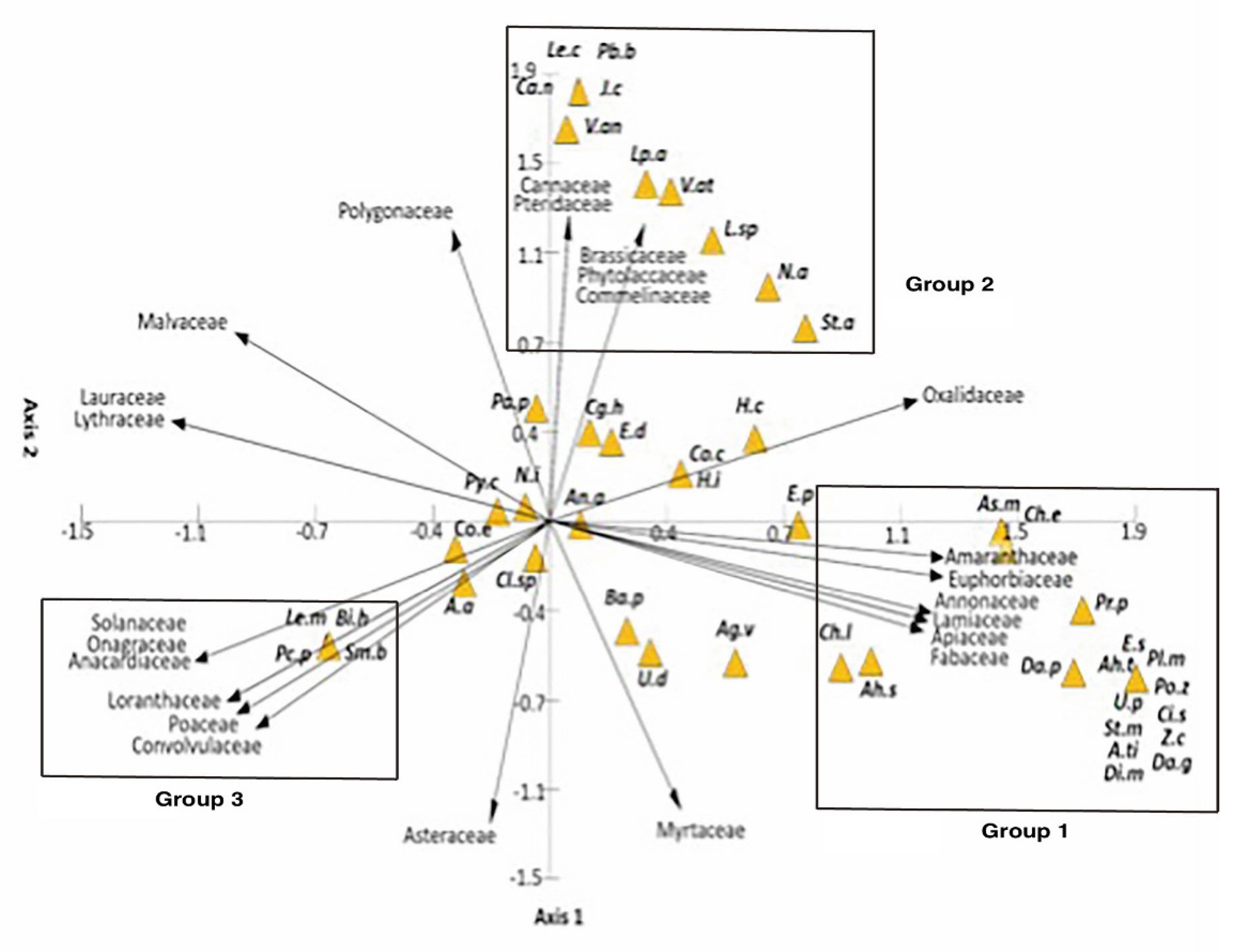

3.2. Influence of plants on the butterfly community

4. Discussion

4.1. Abundance and diversity

4.2. Influence of plants on the butterfly community

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abós, F. El pluricultivo y la presencia de márgenes mantienen la diversidad biológica en los agrosistemas. Ecología 2002, 16, 273–285. [Google Scholar]

- Albino, C.; Cervantes, H.; López, M.; Ríos-Casanova, L.; Lira, R. Patrones de diversidad y aspectos etnobotánicos de las plantas arvenses del valle de Tehuacán-Cuicatlán: el caso de San Rafael, municipio de Coxcatlán, Puebla. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 2011, 82, 1005–1019. [Google Scholar]

- Alignier, A.; Bretagnolle, V.; Petit, S. Spatial patterns of weeds along a gradient of landscape complexity. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2012, 13, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baquero, E.; Moraza, M.L.; Ariño, H.A.; Jordana, R. Mariposas Diurnas de Pamplona. Ayuntamiento de Pamplona: España; 2011.

- Clarke, K.R. Non-parametric multivariate analyses of changes in community structure. Aust. J. Ecol. 1993, 18, 117–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clausen, H.; Holbeck, H.; Reddersen, J. Factors influencing abundance of butterflies and burnet moths in the uncultivated habitats of an organic farm in Denmark. Biol. Conserv. 2001, 98, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collinge, S.K.; Prudic, K.L.; Oliver, J.C. Effects of Local Habitat Characteristics and Landscape Context on Grassland Butterfly Diversity. Conserv. Biol. 2003, 17, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colwell, R.K. EstimateS: statistical estimation of species richness and shared species from simples, version 8.0. 2006. Available from: http://purl. oclc. org/estimates.

- Davis, J.D.; Hendrix, S.D.; Debinski, D.M.; Hemsley, C.J. Butterfly, bee and forb community composition and cross-taxon incongruence in tallgrass prairie fragments. J. Insect Conserv. 2007, 12, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davros, N.M.; Debinski, D.M.; Reeder, K.F.; Hohman, W.L. Butterflies and Continuous Conservation Reserve Program Filter Strips: Landscape Considerations. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2006, 34, 936–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Castillo, J.C. Especies de Malezas Asociadas a Cultivos del Bajío de Guanajuato, México. Celaya, Guanajuato: Programa de Sanidad Vegetal, SAGARPA. 2010. Available from: http://www.agricolaunam.org.mx/colecciones%20virtuales/Malezas%20del%20Bajio%20JUAN%20CARLOS%20DELGADO.pdf.

- Erhardt, A. Diurnal Lepidoptera: Sensitive Indicators of Cultivated and Abandoned Grassland. J. Appl. Ecol. 1985, 22, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahrig, L.; Girard, J.; Duro, D.; Pasher, J.; Smith, A.; Javorek, S.; King, D.; Lindsay, K.F.; Mitchell, S.; Tischendorf, L. Farmlands with smaller crop fields have higher within-field biodiversity. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2014, 200, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fascinetto, Z.P. Dinámica e Identificación de la Comunidad de Mariposas Diurnas (Lepidoptera: Rhopalocera) Asociadas a un Agroecosistema en Atlixco, Puebla. Unpublished thesis, Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, México. 2015.

- Hernández, D.M.F. Butterflies of the agricultural experiment station of tropical roots and tubers, and Santa Ana, Camagüey, Cuba: an annotated list. Acta ZoolÓGica Mex. 2007, 23, 43–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, A.L.; Sheaffer, C.C. Tautges NE, Putnam DH, Hunter M. Alfalfa, Wildlife and the Environment. National Alfalfa and Forage Alliance, St. Paul: Minnesota; 2019.

- Gámez, A.; De Gouveia, M.; Álvarez, W.; Pérez, H.; Mondragón, A.; Alvarado, H.; Vásquez, C. Flora arvense asociada a un agroecosistema tipo conuco en la comunidad de Santa Rosa de Ceiba Mocha en el estado Guárico. Bioagro 2014, 26, 177–182. [Google Scholar]

- Gerell, R. Management of roadside vegetation: effects on density and species diversity of butterflies in Scania, south Sweden. Entomologisk Tidskrift 1997, 118, 171–176. [Google Scholar]

- Giuliano, D.; Cardarelli, E.; Bogliani, G. Grass management intensity affects butterfly and orthopteran diversity on rice field banks. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 267, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassberg, J. A Swift Guide to the Butterflies of Mexico and Central America. Sunstreak Books: Princeton University Press; 2018.

- González-Estébanez, F.J.; García-Tejero, S.; Mateo-Tomás, P.; Olea, P.P. Effects of irrigation and landscape heterogeneity on butterfly diversity in Mediterranean farmlands. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2011, 144, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, S.D.; Shapiro, A.M. Exotics as host plants of the California butterfly fauna. Biol. Conserv. 2003, 110, 413–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grill, A.; Cleary, D.F. Diversity patterns in butterfly communities of the Greek nature reserve Dadia. Biol. Conserv. 2003, 114, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurevitch, J.; Chester Jr, S.T. Analysis of repeated measures experiments. Ecology 1986, 67, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, O.; Harper, D.A.T.; Ryan, P.D. Past Palaeontological, Software version 1.18. Copyright Hammer and Harper; 2003.

- Hassannejad, S.; Ghafarbi, S.P. Weed flora survey in alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) fields of Shabestar (northwest of Iran). Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2014, 60, 971–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Mejía, C.; Llorente-Bousquets, J.; Vargas-Fernández, I.; Luis-Martínez, A. 2008: Las mariposas (Hesperioidea y Papilionoidea) de Malinalco, Estado de México. Rev. Mex. De Biodivers. 2014, 79, 117–130. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Mejía, C.; Flores-Gallardo, A.; Llorente-Bousquets, J. Morfología del corion en Leptophobia (Lepidoptera: Pieridae) e importancia Taxonómica. Southwest. Entomol. 2015, 40, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, P.E.; Bastida, F.; Pujadas, S.A.; Pallavicini, Y.; Izquierdo, F.J.; González, A.J.L. Efecto de la intensificación agrícola en la diversidad taxonómica y funcional de las especies arvenses del banco de semillas en cultivos cerealistas. Poster session presented at: XV Congreso de la Sociedad Española de Malherbología. 2015 Octubre 19-22, Sevilla, España.

- Hintze, J. Software NCSS, PASS and GESS, Kaisville Utah: NCSS; 2008.

- Iwashina, T. Flavonoid Function and Activity to Plants and Other Organisms. Biol. Sci. Space 2003, 17, 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwema, D.; Janes, E.; Rosenberger, D. Late Summer Butterfly Species Richness and Abundance in Bourbonnais Township, Northeastern Illinois. Department of Biological Sciences, Olivet Nazarene University; 2016.

- Jaccard, P. Nouvelles recherches sur la distribution florale. Bull. De La Société Vaudoise Des Sci. Nat. 1908, 44, 223–270. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Valverde, A.; Hortal, J. Las curvas de acumulación de especies y la necesidad de evaluar los inventarios biológicos. Rev. IbÉRica De Aracnol. íA 2003, 8, 151–161. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D.E. Métodos Multivariados Aplicados al Análisis de Datos, International Thomson, México; 1998.

- Kitahara, M.; Sei, K.; Fujii, K. Patterns in the structure of grassland butterfly communities along a gradient of human disturbance: further analysis based on the generalist/specialist concept. Popul. Ecol. 2000, 42, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivinen, S.; Luoto, M.; Kuussaari, M.; Saarinen, K. Effects of land cover and climate on species richness of butterflies in boreal agricultural landscapes. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2007, 122, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, P.K.; Locke, C.; Lee-Mӓder, E. Assessing a farmland set-aside conservation program for an endangered butterfly: USDA State Acres for Wildlife Enhancement (SAFE) for the Karner blue butterfly. J. Insect Conserv. 2017, 21, 929–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovach, W.L. MVSP-A MultiVariate Statistical Package for Windows. Verion 3.13. Pentraeth, Wales: Kovach Computing Services; 2004.

- Kuussaari, M.; Heliölä, J.; Luoto, M.; Pöyry, J. Determinants of local species richness of diurnal Lepidoptera in boreal agricultural landscapes. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2007, 122, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loos, J.; Dorresteijn, I.; Hanspach, J.; Fust, P.; Rakosy, L.; Fischer, J. Low-Intensity Agricultural Landscapes in Transylvania Support High Butterfly Diversity: Implications for Conservation. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e103256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magurran, A.E. Diversity Indices and Species Abundance Models. Ecological Diversity and Its Measurement: Springer, Dordrecht; 1988.

- Mas, M.T.; Verdú, A.M.C. Biodiversidad de la flora arvense en cultivos de mandarino según el manejo del suelo en las interfilas. Boletín De Sanid. Veg. Plagas 2005, 31, 231–242. [Google Scholar]

- Marín, L.; León-Cortés, J.L.; Stefanescu, C. The effect of an agro-pasture landscape on diversity and migration patterns of frugivorous butterflies in Chiapas, Mexico. Biodivers. Conserv. 2008, 18, 919–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Noble, J.I.; Meléndez-Ramírez, V.; Delfín-González, H.; Pozo, C. Mariposas de la selva mediana subcaducifolia de Tzucacab, con nuevos registros para Yucatán, México. Rev. Mex. de Biodivers. 2015, 86, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munguira, M.L.; Thomas, J.A. Use of Road Verges by Butterfly and Burnet Populations, and the Effect of Roads on Adult Dispersal and Mortality. J. Appl. Ecol. 1992, 29, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oostermeijer, J.; van Swaay, C. The relationship between butterflies and environmental indicator values: a tool for conservation in a changing landscape. Biol. Conserv. 1998, 86, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroza, S.A.; Ríos, F.J.L.; Torres, M.M.; Cantú BJE, Piceno SC, Yáñez CLG. Eficiencia del agua de riego en la producción de maíz forrajero (Zea mays L.) y alfalfa (Medigaco sativa): impacto social y económico. Terra Latinoamericana 2014, 32, 231–239. [Google Scholar]

- Pozo de la Tijera, M.C.; Salas-Suárez, N.; Maya-Martínez, A.; Prado-Cuellar, B. Uso y Monitoreo de los Recursos Naturales en el Corredor Biológico Mesoamericano (Áreas Focales Xpujil-Zoh Laguna y Carrillo Puerto). Colegio de la Frontera Sur, Unidad Chetumal, CONABIO; 2005.

- Proctor, M.; Yeo, P.; Lack, A. The Natural History of Pollination. HarperCollins Publishers, Britain; 1996. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Hernández, A.; Micó, E.; Marcos-García, M.d.L. .; Brustel, H.; Galante, E. The “dehesa”, a key ecosystem in maintaining the diversity of Mediterranean saproxylic insects (Coleoptera and Diptera: Syrphidae). Biodivers. Conserv. 2014, 23, 2069–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarinen, K. A comparison of butterfly communities along field margins under traditional and intensive management in SE Finland. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2002, 90, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sans, F.X.; Armengot, L.; Bassa, M.; Blanco-Moreno, J.M.; Caballero-López, B.; Chamorro, L.; José-María, L. La intensificación agrícola y la diversidad vegetal en los sistemas cerealistas de secano mediterráneos: implicaciones para la conservación. Rev. Ecosistemas 2013, 22, 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Santiago, L.J.A.; García, B.L.E.; Rojas, J.C.; Perales, R.H. Host selection behavior of Leptophobia aripa (Lepidoptera: Pieridae). Fla. Entomol. 2006, 89, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawchik, J.; Dufrêne, M.; Lebrun, P. Estimation of habitat quality based on plant community, and effects of isolation in a network of butterfly habitat patches. Acta Oecologica 2003, 24, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, T.; Parish, T. Factors affecting the abundance of butterflies in field boundaries in Swavesey fens, Cambridgeshire, UK. Biol. Conserv. 1995, 73, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabashnik, B.E. Host range evolution: the shift from native legume hosts to alfalfa by the butterfly, Colias philodice eriphyle. Evolution 1983, 37, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tórrez, M.; Arendt, W.; Maes, J.M. Comunidades de aves y lepidópteros diurnos y las relaciones entre ellas en bosque nuboso y cafetal de Finca Santa Maura, Jinotega. Encuentro 2013, 60–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valtonen, A.; Saarinen, K.; Jantunen, J. Intersection reservations as habitats for meadow butterflies and diurnal moths: Guidelines for planning and management. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 79, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vibrans, H.; Tenorio, L.P. Malezas de México. Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, CONABIO, México; 2012.

- Villarreal, H.; Álvarez, M.; Córdoba, S.; Escobar, F.; Fagua, G.; Gast, F.; Mendoza, H.; Ospina, M.; Umaña, A. Manual de Métodos para el Desarrollo de Inventarios de Biodiversidad. Instituto de Investigaciones de Recursos Biológicos Alexander Von Humboldt. Colombia; 2006.

- Villaseñor, J.L.; Espinosa-Garcia, F.J. The alien flowering plants of Mexico. Divers. Distrib. 2004, 10, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villaseñor, J.L. Checklist of the native vascular plants of Mexico. Rev. Mex. de Biodivers. 2016, 87, 559–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wettstein, W.; Schmid, B. Conservation of arthropod diversity in montane wetlands: effect of altitude, habitat quality and habitat fragmentation on butterflies and grasshoppers. J. Appl. Ecol. 1999, 36, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano-González, G.; Ortiz-Ordóñez, G. Diversidad de Lepidópteros diurnos en tres localidades del corredor biológico y multicultural Munchique-Pinche, Cauca, Colombia. Bol. Cient. Mus. Hist. Nat. 2009, 13, 241–224. [Google Scholar]

| Families | Taxa | Abundance | Ethnobotanical use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apiaceae | Foeniculum vulgare, Mill., 1768 | 3 | curative and comestible |

| Asteraceae | *Aldama dentata, La Llave, 1824 | 19 | forage |

| *Bidens odorata, L., 1753 | 32 | curative, forage and comestible | |

| *Galinsoga parviflora, Cav., 1796 | 4 | forage | |

| *Sanvitalia procumbens, Lam., 1792 | 13 | curative and ornament | |

| Taraxacum officinale, F.H.Wigg., 1780 | 56 | curative, forage, comestible, and melliferous | |

| Brassicaceae | *Lepidium virginicum, L., 1753 | 6 | curative, forage and comestible |

| Nasturtium officinale, W.T. Aiton, 1812 | 4 | curative and comestible | |

| Amaranthaceae | Alternanthera sp., Forssk, 1775 | 40 | -- |

| Chenopodium album, L., 1753 | 4 | Curative | |

| Phytolaccaceae | *Phytolacca americana, L., 1753 | 3 | curative, comestible, ornament and to colour |

| Polygonaceae | *Persicaria hydropiperoides, (Michx.) Small, 1903 | 2 | curative, forage and to colour |

| Rumex conglomeratus, Murray, 1770 | 8 | curative and comestible | |

| Commelinaceae | *Commelina diffusa, Burm.f., 1768 | 60 | curative, forage and ornament |

| Fabaceae | *Erythrina coralloides, Moc. y Sessé ex DC., 1825 | 1 | curative, comestible, ornament and artisan |

| Melilotus albus, Medik, 1786 | 2 | forage and melliferous | |

| Medicago lupulina, L., 1753 | 31 | forage and melliferous | |

| *Vigna luteola, (Jacq.) Benth., 1859 | 3 | curative and comestible | |

| Trifolium repens, L., 1753 | 586 | forage and comestible | |

| Lamiaceae | Leonotis nepetifolia, (L.) R.Br.,1811 | 56 | curative, ornament and melliferous |

| *Salvia mexicana, L., 1753 | 4 | forage, comestible, ornament and melliferous | |

| *Salvia longistyla, Benth, 1833 | 93 | Curative | |

| Lauraceae | *Persea americana, Mill., 1768 | 5 | curative and comestible |

| Annonaceae | Annona cherimola, Mill., 1768 | 2 | comestible and combustible |

| Euphorbiaceae | *Euphorbia heterophylla, L., 1753 | 2 | curative |

| Ricinus communis, L., 1753 | 74 | curative | |

| Malvaceae | *Anoda cristata, (L.) Schltdl., 1837 | 6 | curative, forage, comestible and ornament |

| *Kearnemalvastrum lacteum, (Ait.) D.M.Bates, 1967 | 2 | curative, and forage | |

| Malva parviflora, L., 1753 | 9 | curative, forage and comestible | |

| *Sida haenkeana, C.Presl, 1835 | 32 | -- | |

| Lythraceae | *Cuphea angustifolia, Jacq. ex Koehne, 1877 | 8 | curative |

| Myrtaceae | *Psidium guajava, L., 1753 | 5 | curative, forage, comestible, artisan, to colour and combustible |

| Onagraceae | *Oenothera rosea, L´Hér. ex Ait., 1789 | 70 | Curative and ornament |

| Oxalidaceae | *Oxalis corniculata, L., 1753 | 98 | curative, forage, comestible and ornament |

| Poaceae | Arundo donax, L., 1753 | 37 | curative, forage, artisan and construction |

| Bromus carinatus, Hook. & Arn., 1840 | 6 | forage and comestible | |

| Chloris gayana, Kunth., 1829 | 1096 | forage | |

| *Ixophorus unisetus, (J.Presl) Schltdl.,1861 | 44 | forage | |

| *Setaria parviflora, (Poir.) Kerguélen, 1987 | 28 | forage | |

| Pteridaceae | Adiantum sp., L., 1753 | 10 | - |

| Loranthaceae | *Psittacanthus calyculatus, G.Don, 1834 | 1 | curative and artisan |

| Anacardiaceae | Schinus molle, L., 1753 | 1 | curative, forage, comestible, to colour, combustible and construction |

| Convolvulaceae | *Ipomoea purpurea, (L.) Roth., 1787 | 28 | curative and ornament |

| Solanaceae | *Physalis philadelphica, Lam., 1786 | 2 | curative, forage and comestible |

| *Solanum americanum, Mill., 1768 | 4 | curative, comestible and melliferous | |

| *Solanum lanceolatum, Cav., 1795 | 17 | curative, forage, comestible, and melliferous | |

| Solanum sp., L., 1753 | 3 | - | |

| Cannaceae | Canna indica, L., 1753 | 90 | comestible, ornament and artisan |

| 24 | 48 | 2710 |

| Families | Species | Abundance | Nectarfeeding | Yeastfeeding | Mud-puddling |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pieridae | Colias eurytheme Boisduval, 1852 | 1035 | x | - | - |

| Colias cesonia (Stoll,1790) | 5 | x | - | - | |

| **Eurema mexicana (Boisduval, 1836) | 2 | x | - | - | |

| Eurema salome (Reakirt, 1866) | 2 | x | - | - | |

| **Eurema daira (Godart, 1819) | 23 | x | - | x | |

| **Eurema proterpia (Fabricius, 1775) | 11 | x | x | x | |

| Eurema boisduvaliana (C. Felder & R. Felder, 1865) | 3 | x | - | - | |

| Leptophobia aripa (Boisduval, 1836) | 99 | x | - | - | |

| Catasticta nimibice (Boisduval, 1836) | 1 | x | - | - | |

| **Ascia monuste (Linnaeus, 1764) | 11 | x | - | - | |

| Nathalis iole Boisduval, 1836 | 22 | x | - | - | |

| Phoebis boisdusvalii (C. Felder & R. Felder, 1861) | 1 | x | - | - | |

| Phoebis agarithe (Boisduval, 1836) | 2 | x | x | x | |

| Nymphalidae | Chlosyne lacinia (Geyer, 1837) | 20 | x | - | - |

| *Chlosyne ehrenbergii (Geyer, [1833]) | 64 | x | - | - | |

| Vanessa atalanta (Frühstorfer, 1909) | 16 | x | x | - | |

| Vanessa annabella (Field, 1971) | 8 | x | - | - | |

| Anthanassa texana (W.H. Edwards, 1863) | 16 | x | - | - | |

| * Phyciodes pallescens (R. Felder, 1869) | 3 | x | - | - | |

| Anthanassa sitalces (A. Hall, 1917) | 6 | x | - | - | |

| Agraulis vanillae (Riley, 1926) | 2 | x | - | - | |

| Anaea aidea (Guérin-Méneville,[1844]) | 17 | - | x | - | |

| Dione moneta Butler, 1873 | 1 | x | - | - | |

| Danaus gilippus (H.W. Bates, 1863) | 2 | x | - | - | |

| **Danaus plexippus (Linnaeus, 1758) | 15 | x | - | - | |

| Junonia coenia Hübner, [1822] | 1 | x | - | - | |

| Asterocampa idyja (Geyer, [1828]) | 1 | x | x | - | |

| Cissia similis (Butler, 1867) | 1 | - | x | - | |

| Nymphalis antiopa (Linnaeus, 1758) | 3 | x | x | ||

| Biblis hyperia (Cramer, 1779) | 1 | - | x | - | |

| **Smyrna blomfidia (Fabricius, 1781) | 1 | - | x | - | |

| Morpho polyphemus Westwood, 1851 | 5 | - | x | - | |

| *Hamadryas atlantis (H. Bates, 1864) | 1 | - | x | - | |

| Cyllopsis sp. R. Felder, 1869 | 14 | x | x | - | |

| Papilionidae | Battus philenor (Linnaeus, 1771) | 38 | x | - | - |

| Parides photinus (Doubleday, 1844) | 13 | x | - | x | |

| Papilio polyxenes Cramer, 1782 | 8 | x | - | - | |

| Lycaenidae | Hemiargus isola (Reakirt, [1867]) | 3 | x | x | x |

| Hemiargus ceraunus (Butler & H. Druce, 1872) | 8 | x | x | x | |

| Strymon melinus Hübner, 1818 | 1 | x | - | - | |

| Strymon astiocha (Prittwitz, 1865) | 5 | x | - | - | |

| Ziegleria ceromia (Hewitson, 1877) | 1 | x | - | x | |

| Leptotes marina (Reakirt, 1868) | 9 | x | x | x | |

| Leptotes cassius (Cramer, 1775) | 3 | x | x | x | |

| Riodinidae | Calephelis spp. Grote & Robinson, 1869 | 35 | x | - | - |

| Hesperiidae | Pyrgus communis (Grote, 1872) | 109 | x | x | x |

| Ancyloxypha arene (W.H. Edwards, 1871) | 60 | x | - | - | |

| Lerema spp. Scudder, 1872 | 4 | x | - | - | |

| Urbanus dorantes (Stoll, 1790) | 17 | x | - | - | |

| Urbanus procne (Plötz, 1881) | 2 | x | - | - | |

| Pholisora mexicana (Reakirt, 1867) | 1 | x | - | - | |

| Cogia hippalus (W.H. Edwards, 1882) | 6 | x | - | - | |

| Poanes zabulon (Boisduval & Le Conte, [1837]) | 2 | x | - | - | |

| Pyrrhopyge chalybea Scudder, 1872 | 1 | x | - | - | |

| Cymaenes fraus (Godman, 1900) | 1 | x | - | - | |

| Pompeius pompeius (Latreille, [1824]) | 3 | x | - | - | |

| Staphylus spp. Godman & Salvin, 1896 | 4 | x | - | - | |

| 6 | 57 | 1749 |

| Group | Plant species | Butterfly species | p | r2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Erythrina coralloides | Ascia monuste | 0.0001 | 0.42 |

| Anthanassa texana | 0.004 | 0.164 | ||

| Anthanassa sitalces | 0.0001 | 0.609 | ||

| 1 | Salvia longistyla | Ascia monuste | 0.0001 | 0.503 |

| Anthanassa texana | 0.004 | 0.067 | ||

| Anthanassa sitalces | 0.0001 | 0.718 | ||

| Chlosyne lacinia | 0.006 | 0.208 | ||

| 1 | Melilotus albus | Anthanassa sitalces | 0.014 | 0.066 |

| 1 | Leonotis nepetifolia | Chlosyne ehrenbergii | 0.019 | 0.032 |

| 1 | Alternanthera sp. | Chlosyne ehrenbergii | 0.0001 | 0.378 |

| Ziegleria ceromia | 0.0001 | 0.385 | ||

| 1 | Melilotus albus | Anthanassa sitalces | 0.014 | 0.066 |

| 1 | Vigna luteola | Chlosyne ehrenbergii | 0.0002 | 0.104 |

| 1 | Euphorbia heterophylla | Chlosyne ehrenbergii | 0.0009 | 0.078 |

| Ziegleria ceromia | 0.0003 | 0.104 | ||

| 1 | Ricinus communis | Ziegleria ceromia | 0.0001 | 0.88 |

| 2 | Lepidium virginicum | Leptophobia aripa | 0.0001 | 0.909 |

| 2 | Nasturtium officinale | Leptophobia aripa | 0.0001 | 0.039 |

| 2 | Commelina diffusa | Leptophobia aripa | 0.007 | 0.01 |

| 2 | Canna indica | Leptophobia aripa | 0.0001 | 0.049 |

| Junonia coenia | 0.0020 | 0.286 | ||

| Vanessa anabella | 0.0010 | 0.303 | ||

| 3 | Chloris gayana | Biblis hyperia | 0.001 | 0.561 |

| 3 | Bromus carinatus | Smyrna blomfildia | 0.003 | 0.201 |

| 3 | Ixophorus unisetus | Smyrna blomfildia | 0.003 | 0.194 |

| Plant species | Migratory butterfly species | p | r2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Erythrina coralloides | Eurema daira | 0.0009 | 0.231 |

| Ascia monuste | 0.0001 | 0.420 | |

| Aldama dentata | Eurema proterpia | 0.0275 | 0.070 |

| Medicago lupulina | Eurema proterpia | 0.0001 | 0.570 |

| Sanvitalia procumbens | Eurema proterpia | 0.0018 | 0.362 |

| Salvia longistyla | Ascia monuste | 0.0001 | 0.503 |

| Leonotis nepetifolia | Ascia monuste | 0.007 | 0.087 |

| Alternanthera sp. | Danaus plexippus | 0.027 | 0.194 |

| Chloris gayana | Smyrna blomfildia | 0.001 | 0.598 |

| Bromus carinatus | Smyrna blomfildia | 0.003 | 0.201 |

| Ixophorus unisetus | Smyrna blomfildia | 0.003 | 0.194 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).