Importance of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition in prostate cancer

Prostate cancer represents the second most common malignancy and is the fifth most common cause of cancer deaths among men worldwide [

1]. Due to its unique heterogeneity, prostate cancer shows a broad spectrum of clinical behavior regarding progression rate. It may be an indolent or rapid form of prostate cancer, as well as it can exhibit different mortality rates. The newest statistics show that prostate malignancy continues to account for approximately 86.8% of the local stage, and 1.5% of the regional stage among men aged equal to or more than 50 years [

2]. At this stage of the disease, prostate cancer is completely treatable, with the 5-year survival rates for both stages reaching almost 100% [

3]. The difficulties associated with the treatment of prostate cancer patients begin at the systemic stage. In these patients, according to the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Stage, the 5-year survival rate is only 30% [

2]. They constitute 5.1% of the population of men diagnosed with prostate cancer, and the treatment program for these patients is mainly based on the use of ablation androgen ablation, which involves reducing the stimulating effects of androgens on prostate cancer cells [

3]. This therapeutic procedure makes it possible to achieve apparent improvement in the patient's condition, lowering the concentration of prostate specific antigen (PSA) in patients' blood serum, leading to the regression of primary and secondary tumors in 80% of patients. The response phase to hormone therapy, unfortunately, subsides after about 18-24 months of treatment and progresses to the hormone resistance phase, in which the prognosis of patients is much worse, and in most cases, palliative treatment is used. An in-depth understanding of the biology underlying the formation of metastases cancer represents a turning point in the diagnosis of cancer, its early detection, the prognosis of survival time, and the establishment of a plan of oncological treatment of prostate cancer patients. The key issue is to understand the mechanisms of migration and invasion of prostate cancer cells and impact of deregulated factors responsible for modulating the process of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) as the first stage of metastasis formation. The opportunity to rapidly assess expression levels of factors involved in the EMT process under hospital conditions could improve the diagnosis of patients with prostate cancer. The knowledge of the impact of deregulation of the aforementioned factors on the EMT process could provide a basis for the development of effective targeted therapies and influence the therapeutic effects of the advanced stage of this disease.

Definition of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition process

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition is a physiological process that is fundamental to embryogenesis, starting from the implantation stage, through embryo formation, gastrulation and ending with organogenesis, and moreover, it also occurs in the process of tissue regeneration [

4,

5,

6]. The EMT phenomenon also plays a significant role in pathological processes, particularly during cancer progression, in which the expression of genes encoding proteins characteristic of the EMT process associated with embryonic development is observed [

7,

8]. Metastasis formation in cancer involves detachment from the tumor mass of individual cells that have lost intercellular connections and adhesion properties [

9,

10]. The proliferation of cancer cells in the organism, depends, among other things, on a change in cellular phenotype in the epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Thus, pathological activation of the EMT process causes epithelial cells to acquire a mesenchymal phenotype, characterized by increased migratory potential and invasiveness, which allows cancer cells to enter blood vessels (intravasation). Cancer cells migrating through blood vessels must acquire the ability to survive in the deficiency of adhesion by developing a mechanism to prevent anoikis [

11]. It is also worth mentioning that at the site of the primary malignant lesion, mesenchymal cells are characterized by a higher level of ability to penetrate capillary blood vessels, which further promotes their proliferation. At distant sites, circulating tumor cells leave the blood vessels and settle in the new location, forming secondary tumors (metastatic foci). The reverse process of EMT occurs, namely mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET), during which cancer cells regain their epithelial phenotype, extracellular matrix (ECM) contact, and intercellular adhesion [

12].

Changes accompanying the epithelial-mesenchymal transition

Cellular changes

The hallmark of cells undergoing EMT is a high capacity to move and migrate through the ECM. The process of transdifferentiation of fused and stabilized epithelial cells with an epithelial phenotype to a mesenchymal phenotype, giving the cells unique characteristics that facilitate their spread in the body, occurs through a series of physical changes in epithelial cells that make them capable of invading tissues, both adjacent and distant. These changes include a transient loss of intercellular connections, leading to a change in the apical-basal polarity of cells and a reorganization of the cellular cytoskeleton. The change in expression of epithelial (decrease in keratin expression) and mesenchymal (increase in vimentin expression) markers that accompanies the EMT process also results in a change in the shape of epithelial cells to a fibroblastoid shape, facilitating cell migration. Integrity with the basement membrane is abolished in the case of cells with a high migratory status, capable of forming secondary cancer foci. Epithelial cells begin to express mesenchymal markers such as N-cadherin, vimentin, fibronectin and extracellular matrix metalloproteinase activity. Classically, EMT is also characterized by the loss of epithelial markers such as E-cadherin and β-catenin, thereby activating a specific transcriptional program, leading to an increased level of cellular invasivenessundergoing lesions [

13]. There is a strong association between the expression of E-cadherin and the membrane fraction of β-catenin and the progression of prostate cancer to the metastatic stage, which is a potential prognostic marker of disease progression [

14].

Genetic alterations

Transcription factors such as SNAIL (Snail Family Transcriptional Repressor 1), SLUG (Snail Family Transcriptional Repressor 2), ZEB1 (Zinc Finger E-box Binding Homeobox 1), ZEB2 (Zinc Finger E-box Binding Homeobox 2), and TWIST (Twist Family bHLH Transcription Factor 1) are major modulators of the signaling pathways of the EMT process. These transcriptional regulators inhibit the expression of E-cadherin while promoting the expression of mesenchymal markers: N-cadherin and/or R-cadherin and vimentin, as well as the expression of cellular matrix and focal adhesion proteins [

13]. Some of the transcription factors function as markers of adverse disease progression [

15]. In turn, microRNA (microRNA, miRNA) and non-coding RNA molecules can regulate or be regulated by key genes of the EMT process and affect the course of cancer cell proliferation in the body. The best-known non-coding RNA molecules that meet these criteria are the microRNA-200 family of molecules and the miR-34 family of molecules. An example of this relationship is the microRNA-200c-3p/ZEB2 loop in prostate cancer, which may have important implications for the design of treatment strategies for invasive and metastatic prostate cancer in the future.

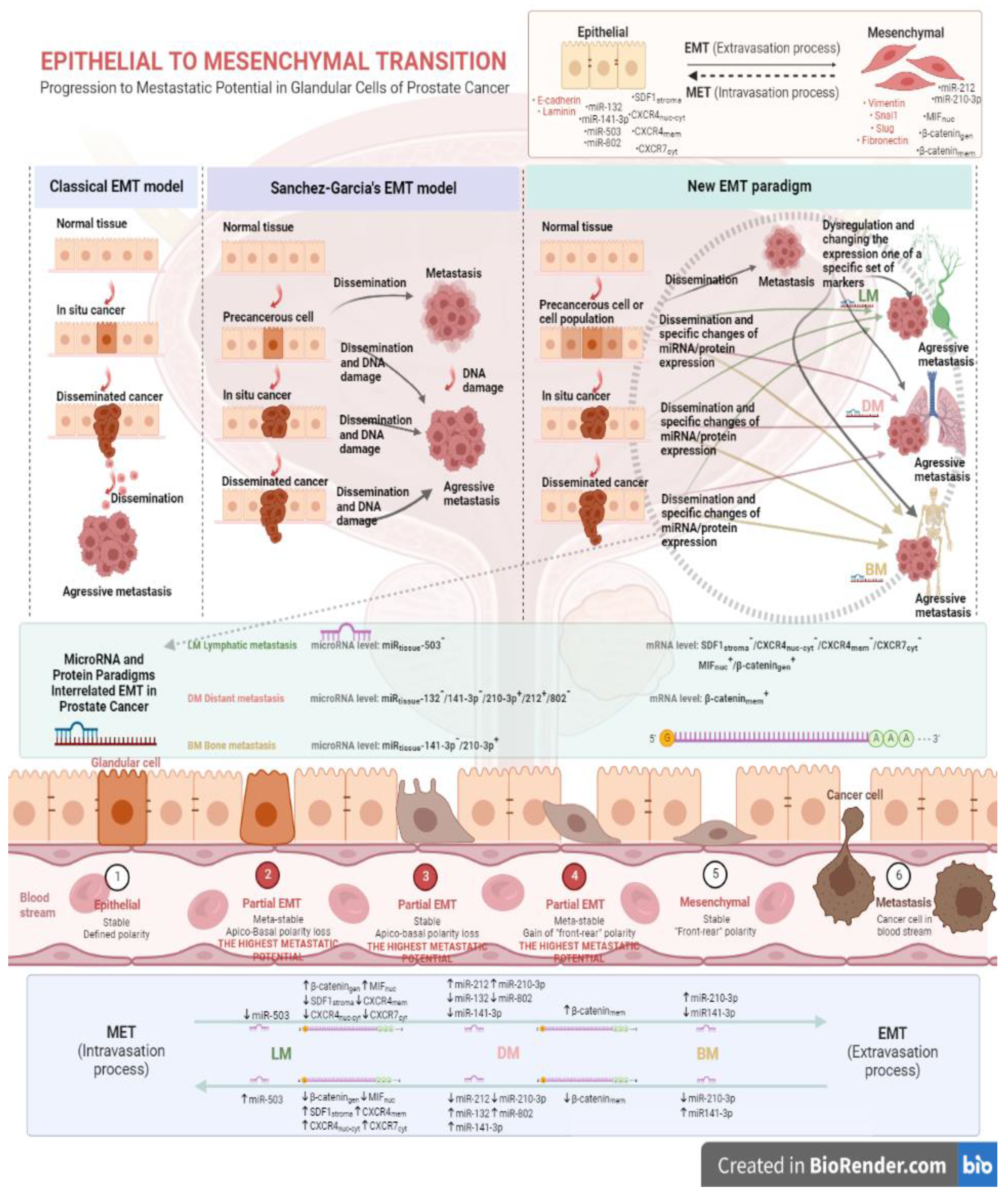

A model of the process of epithelial-mesenchymal transition for prostate cancer

The conventional model of tumor progression indicates that a pivotal role in the process belongs to transcription factors, which possess the ability to re-program prostate cancer cells, giving them the capacity to develop cancer metastases. According to this model, EMT phenomenon is only activated in occasional cancer cells. The expression profile of ECM proteins and cytoskeleton proteins is also altered as the disease progresses. An alternative model of prostate cancer progression was proposed by Sánchez-Garcίa in 2009, stating that pathological activation of EMT-related proteins can continuously drive the spread of metastasis in the body from the primary cancer focus [

28]. Nowadays, we understand that the process of epithelial-mesenchymal transition is influenced directly or indirectly by many regulatory factors, that can be classified as the inductors, regulators and effectors of EMT process, as a consequence leading to the progression of the disease.

The findings of latest research on the effects of some selected tissue biomarkers on the epithelial-mesenchymal transition process for prostate cancer are somewhat consistent with the Sánchez-Garcίa's proposed model of the EMT phenomenon. In the published scientific papers, it has been shown that the altered levels of expression of specific tissue mediators at the level of miRNA and/or mRNA/protein can affect chosen prostate cancer cells, resulting in pathological activation of the EMT program. It is also well known that throughout the tumor progression of the prostate cancer, the levels of expression of these specific tissue mediators gradually change, while the Sánchez-Garcίa model does not consider this. Diagnosed patients with primary prostate cancer, whose disease is characterized by cellular plasticity, manifest a significantly worse prognosis. Thus, one cannot approach the theme of tumor progression in prostate cancer and other cancers with the unequivocal thesis that the EMT process in a cancer cell involves a complete transition from an epithelial phenotype to a pure mesenchymal phenotype, with no intermediate states, as in human embryonic development. This EMT meta-state, which is also known as partial EMT, is characterized by the co-existence of cancer cells with both an incompletely suppressed epithelial phenotype and not fully achieved mesenchymal phenotype. In 2011, Dieter and co-authors demonstrated that cancer cells from a xenograft model of human colon cancer, only under conditions in which stem cells are present and then when they show the capacity for self-renewal, are able to form liver metastases [

29]. A further example of phenotypic plasticity is the budding type of early-stage colorectal cancer which positively correlates with a poorer patient prognosis, compared to those colon cancers exhibiting a non-budding type, due to the fact that the cancer cells manifest an EMT phenotype and possess stem cell properties [

30]. Furthermore, a poorer prognosis amongst those patients with diagnosed tumor budding in colorectal cancer has been demonstrated by the formation of lymph node metastases, and distant metastases into the liver and lungs [

30]. The results obtained during our scientific study are also consistent with the phenotypic plasticity of cancer cells undergoing EMT. The tumor-initiating cancer cells of early-stage prostate cancer may form lymph node metastases or distant metastases to the lungs or skeletal system; however, at each stage of tumor progression, a specific group of tissue factors with symptomatic expression will be involved, from which it will be possible to determine the type of tumor metastasis forming.

Drivers associated with epithelial-mesenchymal transition and progression to the lethal stage of prostate cancer based on latest research

Over the last decade, scientific research in the area of cancer development has been focused on finding 'target proteins' which mediate both the tumor transformation process and the metastasis process of prostate cancer patients and other malignant tumors. Indeed, the strongest diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic potential, therefore, belong to factors that stimulate systemic progression already at an early stage of the disease.

Factors of the inflammation-cancer-epithelial-mesenchymal transition axis

Chronic inflammation can trigger the process of carcinogenesis. The inflammatory response cells can secrete a number of factors that promote both the initiation and progression of cancer and can also induce the epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Well-developed tumors stimulate the inflammatory response by secreting cytokines, chemokines and growth factors that recruit populations of infiltrating immune cells directly into the tumor microenvironment (TME). The inflammatory response potentially exerts control over the tumor, but may instead be intercepted by the tumor to stimulate its own growth towards a metastatic form.

Macrophage migration inhibitory factor

One of the pro-inflammatory cytokines considered to be the link between chronic inflammation and the tumor progression is macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF). MIF leads to the activation of the metastatic process of tumor cells by affecting the reduction of E-cadherin expression and the increase of N-cadherin levels [

31]. In addition, our own studies have shown that an important role in the process of tumor progression of prostate cancer is displayed by the nuclear fraction of the MIF protein. It has been proven that nuclear MIF negatively correlates with the overall expression of β-catenin, so it is likely that the MIF factor affects the abnormal activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, stimulating the translocation of the active form of β-catenin into the cell nucleus to function as an activator of transcription [

32]. Moreover, the nuclear fraction of the MIF protein is responsible for participating in the process of lymph node metastasis formation in prostate cancer. Previous study confirmed significantly higher expression of the nuclear fraction of MIF protein in patients with lymph node metastasis, compared to prostate cancer patients without lymph node metastasis (p<0.05). The same study also found that pathological activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway affects the progression of prostate cancer to the systemic stage, through the formation of both lymph node and distant metastases [

33]. The effect of MIF factor on accelerating tumor growth and metastasis in pancreatic cancer was also confirmed by Funamizu and his co-authors. Performing studies on mouse models overexpressing MIF, they proved, significant tumor growth (p<0.001) in mice with MIF overexpression, compared to control mouse cells [

34].

Stromal Cell-Derived Factor-1 and its binding receptors

The interaction of stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1) with C-X-C motif chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4) or C-X-C motif chemokine receptor type 7 (CXCR7) affects the regulation of many physiological and pathological processes. CXCR7 affect the regulation of many physiological and pathological processes, such as cell proliferation and differentiation, adhesion, migration, and cancer cell metastasis. The binding receptors, CXCR4 and CXCR7, are metabotropic receptors present on the surface of human tumor cells [

35] that interact with the G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) and can be activated by the common ligand SDF-1. These molecules play a key role in TME by promoting tumor progression, and they also manage tumor cell proliferation and migration and the recruitment of immune and stromal cells in TME. SDF-1 eliminates T cells from the TME through a concentration gradient that inhibits access of immunoactive cells and promotes blood vessel formation within the tumor [

36]. The presence of CXCR4 and CXCR7 binding receptors, among others, was detected on human rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) cells. In this study, the binding receptors were shown to be involved in conferring metastatic potential to RMS cells through CXCR7's effect on tumor cell adhesion and CXCR4's mediation of migration-related signals [

35,

37]. Blocking of CXCR4 and CXCR7 signaling pathways may therefore prevent prostate cancer progression to the metastatic stage in a dualistic manner, by inhibiting the growth, migration and chemotaxis of tumor cells and by promoting the presence of T cells in the TME. In studies on human prostate cancer tissues, authors proved that both SDF-1 factor and its binding receptors CXCR4 and CXCR7 are involved in lymph node metastasis. A decrease in the expression of the SDF-1 protein subfraction was noted in patients with current lymph node metastases, compared to patients without metastases. A similar phenomenon was noted for binding receptors: the nuclear-cytoplasmic fraction of CXCR4 protein and the cytoplasmic fraction of CXCR7 protein - a decrease in the expression of these proteins was evident in tissues from patients with lymph node metastases present [

38]. Previous studies have shown that human prostate cancer cells producing CXCR7 have the ability to proliferate faster, form metastases and develop blood vessels [

35]. Modern approaches to targeted therapy for prostate cancer indicate targeting the approach simultaneously to immune checkpoints and the SDF-1/CXCR4/CXC7 axis.

MicroRNAs modulating the epithelial-mesenchymal transition process

An important mechanism regulating the expression of genes associated with tumor progression in prostate cancer is represented by miRNA molecules. These constitute a group of short, single-stranded, non-coding RNA molecules. Mature miRNA molecules, approximately 19-23 nucleotides in length, are synthesized from double-stranded precursors, with the participation of polymerase II, and are incorporated into RNA-induced silencing complexes (miRISC). They thus have the ability to post-transcriptionally silence target genes by attaching to the 3' untranslated regions (3'UTR) of the target gene's mRNA, thereby inducing mRNA degradation or inhibition of translation. MiRNA molecules are also involved in regulating important cellular processes, such as those of cell differentiation or proliferation, and modulate epigenetic regulatory processes. Depending on the target genes on which miRNA molecules affect, they can function as oncogenes or suppressor genes.

A major regulatory role in the EMT process is attributed to miRNA-200 and miRNA-205 molecules, which have the ability to repress transcription factors associated with E-cadherin activity, namely ZEB1 and ZEB2, and inhibit the activity of other transcription factors associated with the EMT process, such as TWIST1. In contrast, miRNA-132 and miRNA-212 molecules inhibit the activity of the transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) protein, which, by blocking the SOX4 factor, modulates the EMT process, and, in addition, miRNA-132 has a silencing effect on the activity of the ZEB2 protein [

39].

MiRNAs exhibit highly tissue-specific expression, which makes it possible to differentiate between normal and diseased tissue on the basis of changes in their expression levels, but also to distinguish between different types of cancer. It appears that by using miRNA molecule profiles specific for prostate cancer, on the basis of changes in the expression level of these molecules, it is possible to predict the level of aggressiveness of the tumor, predict disease progression and classify tumor stage. Latest research has detailed nine miRNA molecules closely associated with the metastatic process in prostate cancer patients. Among others, overexpression of miR-210-3p and deregulation of miR-141-3p have been shown to be associated with the presence of metastasis in prostate cancer patients, particularly distant metastasis and bone metastasis [

40]. Furthermore, based on the performed meta-analysis, the distinctive miRNA signatures for individual types of metastasis in prostate cancer patients were distinguished. The results of our own study were synthesized and are shown in

Figure 1.

The abnormal expression profile of miRNA molecules can be a plausible diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for prostate cancer patients, including being used to evaluate the stage of the disease, estimate survival time, predict disease progression, and typify the kind of metastasis. Moreover, the assessment of disease progression on the basis of an abnormal profile of miRNA molecules may prove to be a helpful tool in the selection of targeted or patient-specific treatment.

Relationships between particular miRNA molecules and the proteins in the epithelial-mesenchymal transition process

Indeed, an unexplained issue in this dissertation remains the identification of correlations between the individual factors involved in the EMT process, in the miRNA-protein profiles extracted, in the course of our own research, that characterize the different types of metastasis in patients with prostate cancer (

Figure 1). Information about such correlations, to an incomplete extent, is provided from scientific studies performed to date. Wenjing and co-authors showed that the mir-503 molecule is responsible for suppressing the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway by leading to an increase in the expression of the glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta (GSK-3β) and p-β-catenin, while reducing the levels of both factors in gastric cancer cells [

41]. In contrast, Pengbo and co-workers showed that inhibition of mir-212 leads to activation of the forkhead box M1 (FOXM1) factor, but has an inhibitory effect on the canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway by suppressing factors such as wingless-type like signaling (Wnt), lymphoid enhancer binding factor 1 (LEF-1), myelocytomatosis (c-Myc) and the nuclear fraction of β-catenin in hepatocellular carcinoma [

42]. In contrast, Lun-Qing and the other co-authors of the research paper demonstrated that overexpression of miR-802 leads to activation of the Wnt/β-catenin and nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells/p65 (NF-κβ/p65) signaling pathway in lung cancer cells, showing an increase in nuclear β-catenin fraction and p65 protein levels [

43].

Determining the reciprocal effects of the miRNA molecules and proteins studied may lead to the delineation of new signalling pathways associated with tumour progression in prostate cancer. Indeed, there are literature reports of a possible regulatory effect of the chemokine SDF-1 on selected miRNA molecules. Potter and his co-authors in their study on bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) indicated that SDF-1, by interacting with certain miRNA molecules, modulates the migration process of BMSCs [

44]. Cytokines and mediators of the inflammatory process can regulate the expression of miRNA molecules,

through which they also indirectly affect the regulation of many genes [

45,

46]. Yang and the other co-authors of this paper demonstrated that the factor MIF stimulated an increase in miR-301b expression thereby having an inhibitory effect on nuclear receptor subfamily 3 group C member 2 (NR3C2) in pancreatic cancer patients. Functional studies showed that reduced NR3C2 expression levels correlated with a worse prognosis in these patients. Furthermore, the same study showed that genetic deletion of MIF disrupted the MIF-miR-301b-NR3C2 signaling axis, inhibiting metastatic spread and formation and prolonging survival in a genetically engineered mouse model [

47]. Confirmation of such relationships between proteins and miRNA molecules in prostate cancer patients could suggest that inflammation plays a key role in tumor initiation and progression in prostate cancer patients, and that the chemokine SDF-1 and the pro-inflammatory cytokine MIF could be early markers of disease progression and a starting point for individualized treatment selection. The use of miRNA-protein profiles in the oncological diagnosis of prostate cancer patients as a tool to help classify the stage of patients diagnosed with this cancer seems to be future-oriented.

Summary

The EMT phenomenon is a multi-pathway programme with numerous regulatory factors responsible for specific cellular signaling pathways. These factors interact to form a communication network through which cancer progression occurs. A modern model of tumor cells spreading to lymph nodes or distant organs shows that metastatic pathologies are defined by a unique set of altered tissue-specific factors leading to activation of the EMT process and initiation of the invasive-metastatic cascade in prostate cancer patients. In secondary foci, tumor cells change their phenotype to epithelial as a result of the reverse process, MET. Deregulation of specific factors determining the mesenchymal phenotype of migrating cells is a transitional process until these cells return to their original state to form metastatic foci. This demonstrates that changes in the expression of factors involved in the epithelial-mesenchymal transition are variable, and from these alterations, it is possible to determine the stage of the disease and assess the prognosis of patients. The quest for effective treatment of metastatic prostate cancer should therefore focus on silencing or balancing the deregulated expression of EMT-related factors to reverse its function to baseline. Further research should therefore be directed towards a multifaceted analysis of the factors responsible for regulating the EMT process, the importance of which is already crucial in the first stages of tumor initiation. Further progress in the area of epithelial-to-mesenchymal cell transformation in prostate cancer patients will facilitate the translation of this achievement into the possibility of implementing advanced oncological diagnosis, early disease prognosis and treatment directed at stabilizing miRNA and mRNA/protein levels. The use of miRNAs or mRNAs/proteins as biomarkers or direct pharmacological targets has the potential to change the approach to treating patients with metastatic prostate cancer and provide tangible therapeutic benefits.

Conclusions

1. Altered expression levels of specific sets of miRNA molecules may be potential predictors of prostate cancer progression to the systemic stage and may be useful in differentiating types of metastasis.

2. High expression levels of the nuclear fraction of the MFI protein may be a potential predictor of disease progression in patients with prostate cancer.

3. Low levels of expression of the sub-endothelial fraction of SDF-1 protein and its binding receptors: the membrane fraction of CXCR4 protein and the nuclear-cytoplasmic fraction of CXCR7 protein may be independent predictors of disease progression to the systemic stage in patients with prostate cancer.

4. The determination of expression levels of miRNA molecules and proteins in prostate cancer patients, in combination with standard tumor markers, may provide a valuable prognostic tool or serve to improve disease staging classification.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from the Healthcare Foundation (Bydgoszcz, Poland)

Contributions

This paper was planned by MPK, and she is responsible for the overall conception of the work, writing the manuscript, and drafting of the manuscript. MPK was responsible for creating figures. DG supervised the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript

Conflicts of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A; et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fillon, M. Rates of advanced prostate cancer continue to increase. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020, 70, 427–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts and Figures 2021. Atlanta, Ga Am Cancer Soc. 2021.

- Hay, E.D. The mesenchymal cell, its role in the embryo, and the remarkable signaling mechanisms that create it. Dev. Dyn. 2005, 233, 706–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moustakas A, Heldin CH. Signaling networks guiding epithelial-mesenchymal transitions during embryogenesis and cancer progression. Cancer Sci. 2007, 98, 1512–1520. [CrossRef]

- Hugo H, Ackland ML, Blick T, Lawrence MG, Clements JA, Williams ED; et al. Epithelial - Mesenchymal and mesenchymal - Epithelial transitions in carcinoma progression. J. Cell. Physiol. 2007, 213, 374–383. [CrossRef]

- Brabletz T, Jung A, Spaderna S, Hlubek F, Kirchner T. Migrating cancer stem cells - An integrated concept of malignant tumour progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2005, 5, 744–749. [CrossRef]

- Gotzmann J, Mikula M, Eger A, Schulte-Hermann R, Foisner R, Beug H; et al. Molecular aspects of epithelial cell plasticity: Implications for local tumor invasion and metastasis. Mutat. Res. - Rev. Mutat. Res. 2004, 566, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savagner, P. Leaving the neighborhood: Molecular mechanisms involved during epithelial-mesenchymal transition. BioEssays. 2001, 23, 912–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin T, Getsios S, Caldelari R, Godsel LM, Kowalczyk AP, Müller EJ; et al. Mechanisms of plakoglobin-dependent adhesion: Desmosome-specific functions in assembly and regulation by epidermal growth factor receptor. J Biol Chem. 2005, 280, 40355–40363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddig PJ, Juliano RL. Clinging to life: Cell to matrix adhesion and cell survival. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2005, 24, 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirkan, B. The roles of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET) in breast cancer bone metastasis: Potential targets for prevention and treatment. J. Clin. Med. 2013, 2, 264–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaves LP, Melo CM, Saggioro FP, Borges R, Squire JA. Epithelial – Mesenchymal Transition Signaling and Prostate Precision Therapeutics. 2021, 71, 209–249.

- Gravdal K, Halvorsen OJ, Haukaas SA, Akslen LA. A Switch from E-Cadherin to N-Cadherin Expression Indicates Epithelial to Mesenchymal T ransition and Is of Strong and Independent Importance for the Progress of Prostate Cancer. 2007, 13, 21–24.

- Armstrong AJ, Healy P, Halabi S, Vollmer R, Lark A, Kemeny G; et al. Evaluation of an Epithelial Plasticity (EP) Biomarker Panel in Men with Localized Prostate Cancer. 2016, 19, 40–45.

- Zhang J, Zhang H, Qin Y, Chen C, Yang J, Song N; et al. MicroRNA-200c-3p/ZEB2 loop plays a crucial role in the tumor progression of prostate carcinoma. Ann Transl Med. 2019, 7, 141–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burrell RA, Swanton C. Re-Evaluating Clonal Dominance in Cancer Evolution. Trends Cancer. 2016, 2, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assaraf YG, Brozovic A, Gonc AC, Jurkovicova D, Sarmento-ribeiro AB, Xavier CPR; et al. The multi-factorial nature of clinical multidrug resistance in cancer. 2019, 46, 100645.

- Vasan N, Baselga J, Hyman DM. A view on drug resistance in cancer. Nature. 2019, 575, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiery JP, Acloque H, Huang RYJ, Nieto MA. Review Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transitions in Development and Disease. 2009; 871–890.

- Chaffer CL, Juan BPS, Lim E, Weinberg RA. EMT, cell plasticity and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2016, 35, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuxe J, Mayor R, Nieto MA, Puisieux A, Runyan R, Savagner P; et al. Guidelines and definitions for research on epithelial–mesenchymal transition. 2020, 21, 341–352.

- Inoue A, Seidel MG, Wu W, Kamizono S, Ferrando AA, Bronson RT; et al. Slug, a highly conserved zinc finger transcriptional repressor, protects hematopoietic progenitor cells from radiation-induced apoptosis in vivo. 2002, 2, 279–288.

- Olmeda D, Moreno-bueno G, Flores JM, Fabra A, Portillo F, Cano A. SNAI1 Is Required for Tumor Growth and Lymph Node Metastasis of Human Breast Carcinoma MDA-MB-231 Cells. 2007, 68, 956.

- Pastushenko I, Blanpain C. EMT Transition States during Tumor Progression and Metastasis. Trends Cell Biol. 2019, 29, 212–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert AW, Weinberg RA. Linking EMT programmes to normal and neoplastic epithelial stem cells. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008, 21, 325–338. [Google Scholar]

- Williams ED, Gao D, Thompson EW. Controversies around epithelial– mesenchymal plasticity in cancer metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2019, 19, 716–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-García, I. The Crossroads of Oncogenesis and Metastasis. N Engl J Med. 2009, 360, 297–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dieter SM, Ball CR, Hoffmann CM, Nowrouzi A, Herbst F, Zavidij O; et al. Distinct types of tumor-initiating cells form human colon cancer tumors and metastases. Cell Stem Cell. 2011, 9, 357–365. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brabletz, T. To differentiate or not-routes towards metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2012, 12, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guda MR, Rashid MA, Asuthkar S, Jalasutram A, Caniglia JL, Tsung AJ; et al. Pleiotropic role of macrophage migration inhibitory factor in cancer. Am J Cancer Res. 2019, 9, 2760–2773. [Google Scholar]

- Shang S, Hua F, Hu ZW. The regulation of β-catenin activity and function in cancer: Therapeutic opportunities. Oncotarget. 2017, 8, 33972–33989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parol-Kulczyk M, Gzil A, Maciejewska J, Bodnar M, Grzanka D. Clinicopathological significance of the EMTrelated proteins and their interrelationships in prostate cancer. An immunohistochemical study. PLoS ONE. 2021, 16, e0253112. [Google Scholar]

- Funamizu N, Hu C, Lacy C, Schetter A, Zhang G, He P; et al. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor induces epithelial to mesenchymal transition, enhances tumor aggressiveness and predicts clinical outcome in resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2012, 132, 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- Maksym RB, Tarnowski M, Grymula K, Tarnowska J, Wysoczynski M, Liu R; et al. The role of stromal-derived factor-1 - CXCR7 axis in development and cancer. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2009, 625, 31–40. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santagata S, Ieranò C, Trotta AM, Capiluongo A, Auletta F, Guardascione G; et al. CXCR4 and CXCR7 Signaling Pathways: A Focus on the Cross-Talk Between Cancer Cells and Tumor Microenvironment. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 591386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grymula K, Tarnowski M, Wysoczynski M, Drukala J, Barr FG, Ratajczak J; et al. Overlapping and distinct role of CXCR7-SDF-1/ITAC and CXCR4-SDF-1 axes in regulating metastatic behavior of human rhabdomyosarcomas. Int J Cancer. 2010, 127, 2554–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parol-Kulczyk M, Gzil A, Ligmanowska J, Grzanka D. Prognostic significance of SDF-1 chemokine and its receptors CXCR4 and CXCR7 involved in EMT of prostate cancer. Cytokine. 2022, 150, 155778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klymenko Y, Kim O, Stack MS. Complex determinants of epithelial: Mesenchymal phenotypic plasticity in ovarian cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2017, 9, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parol M, Gzil A, Bodnar M, Grzanka D. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the prognostic significance of microRNAs related to metastatic and EMT process among prostate cancer patients. J. Transl. Med. 2021, 19, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li W, Li J, Mu H, Guo M, Deng H. MiR-503 suppresses cell proliferation and invasion of gastric cancer by targeting HMGA2 and inactivating WNT signaling pathway. Cancer Cell Int. 2019, 19, 164.

- Jia P, Wei G, Zhou C, Gao Q, Wu Y, Sun X; et al. Upregulation of MiR-212 inhibits migration and tumorigenicity and inactivates Wnt/β-catenin signaling in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2018, 17, 1533034618765221. [Google Scholar]

- Wang LQ, Chen G, Liu XY, Liu FY, Jiang SY, Wang Z. microRNA-802 promotes lung carcinoma proliferation by targeting the tumor suppressor menin. Mol Med Rep. 2014, 10, 1537–1542.

- Potter ML, Smith K, Vyavahare S, Kumar S, Periyasamy-Thandavan S, Hamrick M; et al. Characterization of Differentially Expressed miRNAs by CXCL12/SDF-1 in Human Bone Marrow Stromal Cells. Biomol Concepts. 2021, 12, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asirvatham AJ, Magner WJ, Tomasi TB. miRNA regulation of cytokine genes. Cytokine. 2009, 45, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty C, Sharma AR, Sharma G, Lee SS. The Interplay among miRNAs, Major Cytokines, and Cancer-Related Inflammation. Mol. Ther. - Nucleic Acids. 2020, 20, 606–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang S, He P, Wang L, Wang J, Schetter A, Tang W; et al. Abstract 4789: A novel MIF signaling pathway drives the malignant character of pancreatic cancer by targeting NR3C2. Cancer Res. 2017, 76, 3838–3850. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).