Submitted:

11 July 2023

Posted:

12 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Objective and analytical framework

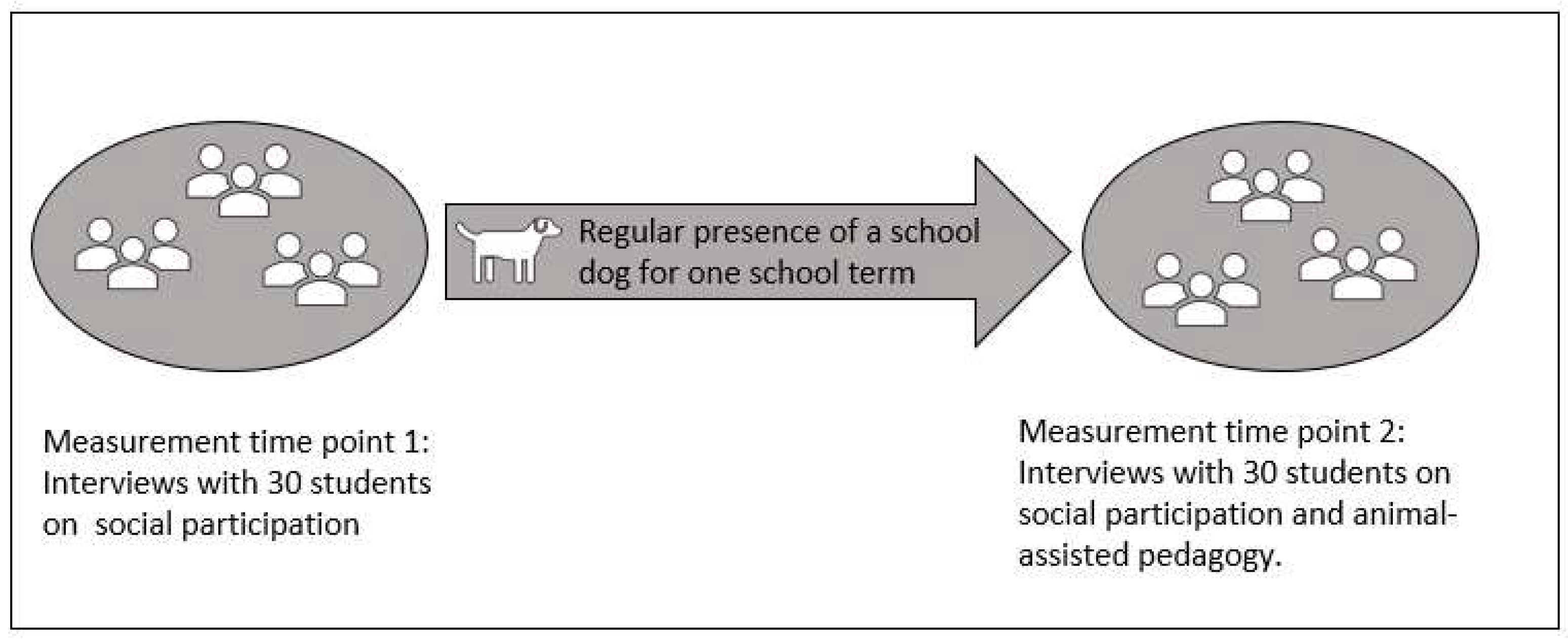

2.2. Method and design

2.3. Sampling

2.4. Analysis

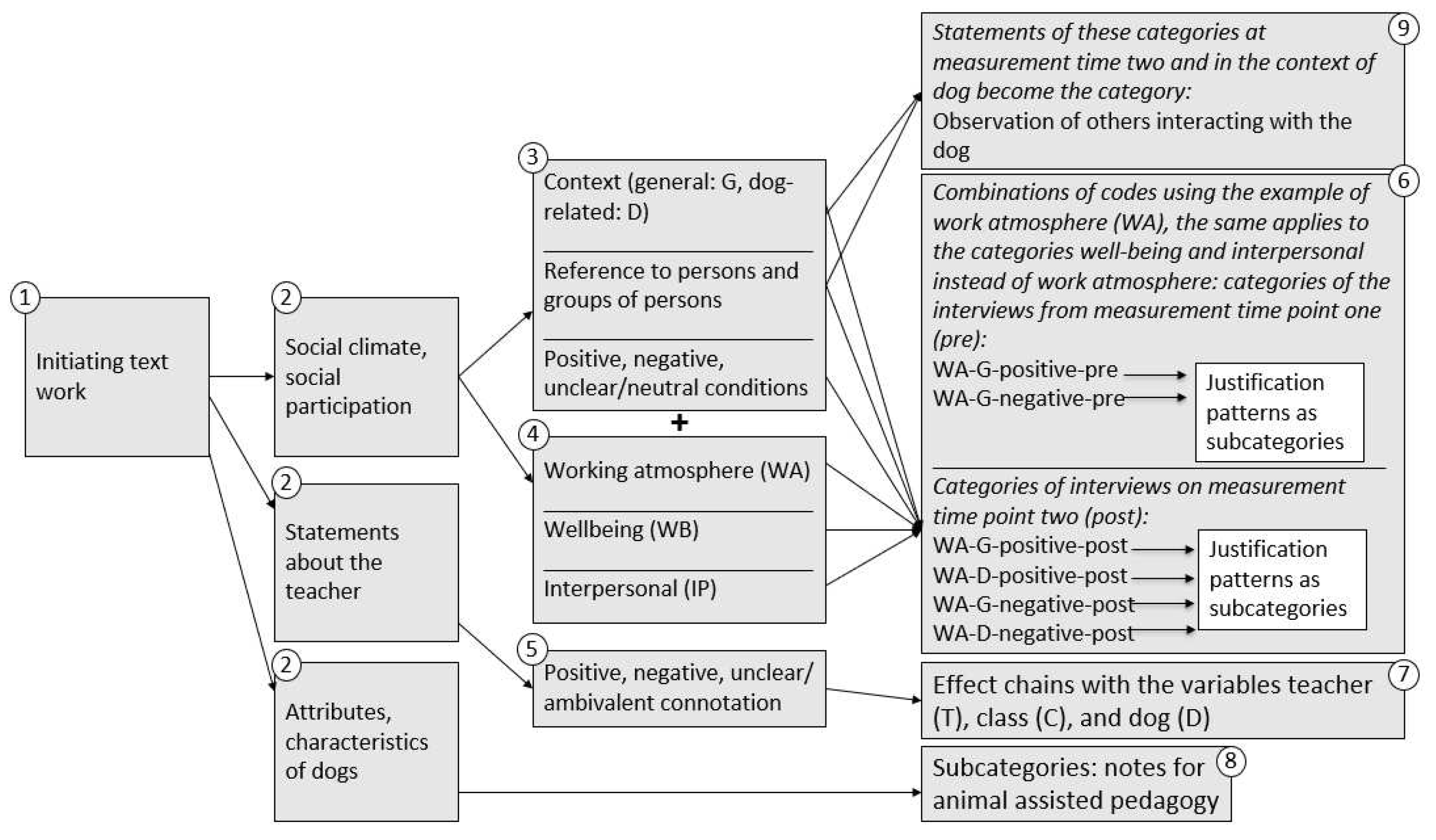

- Initiating text work with the aid of the postscripts and the full transcripts of the problem-centered interviews

- Coding of pre-formulated main categories: A Social climate and social participation, B Learners’ perceptions of the teacher, and C Comments on Attributes and characteristics of dogs, regardless of the topic of social climate

- Category formation: Coding along the main categories A in a) Assessment (positive, problematic, and unclear/neutral) and in b) Context (dog, no dog). Moreover, the main category A was categorized in a differentiated manner, in c) the References (to oneself, to individuals (others), and to everyone, that is to say, the whole class and generally formulated statements).

- Formation of subcategories along the main category A: Coding as Working atmosphere, Interpersonal, and Well-being

- Category formation: Coding along the main categories B in Assessment (positive, problematic, and unclear/neutral)

- Combination of subcategories and emphasis of Justification patterns as further subcategories along the categories Working atmosphere, Interpersonal, and Well-being and further Differentiation of the justification patterns if necessary

- The statements about the teacher from the post-interviews are coded into the Impact chains category. The impact refers to the interaction of teacher – dog – class.

- Along the main category C: The Statements about attributes and the Meaning attributions to dogs are coded into three thematic subcategories.

- Expanding on the subcategory Individuals and Everyone as well as Context dog at the second measurement time point, selected statements are coded as the category Observations of others interacting with the dog.

3. Results

3.1. Part 1: Implications of animal-assisted education for social participation and so-cial climate

3.1.1. Working atmosphere

3.1.2. Well-being and uneasiness

3.1.3. Interpersonal dimension

3.1.4. Perception of the teacher

3.2. Results part 2: Potential of animal-assisted education

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Böttinger T. Förderbedarf gleich Ausgrenzung?: Ein systematischer Forschungsreview zur sozialen Dimension schulischer Inklusion in der Primarstufe in Deutschland. Empirische Sonderpädagogik 2021;13(3):216–37.

- Wüthrich S, Sahli Lozano C, Torchetti, L. & Lüthi, M. Zusammenhänge des peerbezogenen Klassenklimas und der sozialen Partizipation von Schüler*innen mit kognitiven und sozial-emotionalen Beeinträchtigungen. Empirische Sonderpädagogik 2022;14(2):123–38.

- Krawinkel S, Südkamp A, Tröster H. Soziale Partizipation in inklusiven Grundschulkassen: Bedeutung von Klassen- und Lehrkraftmerkmalen. Empirische Sonderpädagogik 2017;9(3):277–95.

- Schmitt R. Die soziale Partizipation von Schüler(inne)n in Lerngruppen der inklusiven Grundschule. In: Donie C, Foerster F, Obermayr M, Deckwerth A, Kammermeyer G, Lenske G et al., editors. Grundschulpädagogik zwischen Wissenschaft und Transfer: Jahrbuch Grundschulforschung. Wiesbaden: Springer VS; 2019, p. 290–295.

- Schürer S. Soziale Partizipation von Kindern mit sonderpädagogischem Förderbedarf in den Bereichen Lernen und emotionale-soziale Entwicklung in der allgemeinen Grundschule: Ein Literaturreview. Empirische Sonderpädagogik 2020;12(4):295–319.

- Blumenthal Y, Blumenthal S. Zur Situation von Grundschülerinnen und Grundschülern mit sonderpädagogischem Förderbedarf im Bereich emotionale und soziale Entwicklung im inklusiven Unterricht.: Longitudinale Betrachtung von Klassenklima, Lehrer-Schüler-Beziehung und sozialer Partizipation. Zeitschrift für Pädagogische Psychologie 2021:1–16.

- Crede J, Wirthwein L, Steinmayr R, Bergold S. Schülerinnen und Schüler mit sonderpädagogischem Förderbedarf im Bereich emotionale und soziale Entwicklung und ihre Peers im inklusiven Unterricht.: Unterschiede in sozialer Partizipation, Schuleinstellung und schulischem Selbstkonzept. Zeitschrift für Pädagogische Psychologie 2019;33(3-4):207–21.

- Zurbriggen C, Venetz M. Soziale Partizipation und aktuelles Erleben im gemeinsamen Unterricht. Empirische Pädagogik 2016;30(1):98–112.

- Henke T, Bosse S, Lambrecht J, Jäntsch C, Jaeuthe J., Spörer N. Mittendrin oder nur dabei?: Zum Zusammenhang zwischen sonderpädagogischem Förderbedarf und sozialer Partizipation von Grundschülerinnen und Grundschülern. Zeitschrift für Pädagogische Psychologie 2017;31(2):111–23.

- Vock M, Gronostaj A, Kretschmann J, Westphal A. “Meine Lehrer mögen mich” - Soziale Integration von Kindern mit sonderpädagogischem Förderbedarf im gemeinsamen Unterricht in der Grundschule.: Befunde aus dem Pilotprojekt “Inklusive Grundschule” im Land Brandenburg. DDS - Die Deutsche Schule 2018;110(2):124–38.

- Felder F. Die Grenzen eines Rechts auf schulische Inklusion und die Bedeutung für den Gemeinsamen Unterricht. Psychologie in Erziehung und Unterricht 2014;62(1):18–29.

- Beetz A. Hunde im Schulalltag: Grundlagen und Praxis. 5th ed. München: Ernst Reinhardt Verlag; 2021.

- Kotrschal K, Ortbauer B. Behavioral effects of the presence of a dog in a classroom. Anthrozös 2003;16(2):147–59.

- Hergovich A, Monshi B, Semmler G, Zieglmayer V. The effects of the presence of a dog in the classroom. Anthrozös 2002;15(1):37–50.

- Meints K, Brelsford VL, Dimolareva M, Mare’chal L, Pennigton K, Rowan E. Can dogs reduce stress levels in school children? effects of dog-assisted interventions on salivary cortisol in children with and without special educational needs using randomized controlled trials. PLoS One 2022;17(6).

- Brelsford VL, Meints K, Gee NR, Pfeffer K. Animal-assisted interventions in the classroom: A systematic review. Int. J.Environ. Res. Public Health 2017;14(7):669.

- Clarke AM, Morreale S, Field CA, Hussein Y, Barry MM. What works in enhancing social and emotional skills development during childhood and adolescence?: A review of the evidence on the effectiveness of school-based and out-of-school programmes in the UK; 2015.

- Dicé F, Santaniello A, Gerardi F, Menna LF, Freda M. Meeting the emotion!: Application of the Federico II Model for pet therapy to an experience of animal assisted education (AAE) in a primary school. Pratiques psychologiques 2017;23:455–63.

- O’Haire ME, McKenzie SJ, McCune S, Slaughter V. Effects of Classroom Animal-Assisted Activities on Social Functioning in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 2014:162–8.

- Berry A, Borgi M, Francia N, Alleva E, Cirulli F. Use of assistance and therapy dogs for children with autism spectrum disorders: A critical review of the current evidence. J. Altern Complement Med. 2013;19(2):73–80.

- Bert F, Gualano MR, Camussi E, Pieve G, Voglino G, Siliquini R. Animal-assisted intervention: A systematic review of benefits and risks. Eur J Integr Med 2016;8(5):695–706.

- Wice M, Goyal N, Forsyth N, Noel K, Castano E. The Relationship Between Humane Interactions with Animals, Empathy, and Prosocial Behavior among Children. Human-Animal Interaction Bulletin 2020;8(1):38–49.

- Julius H, Beetz A, Kotrschal K, Turner DC, Uvnäs-Morberg K. Bindung zu Tieren: Psychologische und neurobiologische Grundlagen tiergestützter Interventionen. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 2014.

- Flynn E, Brandl Denson E, Mueller MK, Gandenberger J, Morris K. N. Human-animal-environment interactions as a context for youth social-emotional health and wellbeing: Practitioners’ perspectives on processes of change, implementation, and challenges. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice 2020;41.

- Purewal R, Christley R, Kordas K, Joinson C, Meints K, Gee N et al. Companion Animals and Child/Adolescent Development: A Systematic Review of the Evidence. International journal of environmental research and public health 2017;14(3).

- Beetz A, Uvnäs-Morberg K, Julius H, Kotrschal K. Psychosocial and psycho-physiological effects of human-animal interactions: the possible role of oxytocin. Frontiers in psychology 2012;3:1–15.

- Beetz A, Julius H, Turner DC, Kotrschal K. Effects of social support by a dog on tress modulation in male children with insecure attachment. Frontiers in psychology 2012(3):1–9.

- Juvonen J, Lessard LM, Rastogi R, Schacter HL, Smith DS. Promoting Social Inclusion in Educational Settings: Challenges and Opportunities. Educational Psychologist 2019;54(4):250–70.

- Mombeck M. Tiergestützte Pädagogik – Soziale Teilhabe – Inklusive Prozesse. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden; 2022.

- Flick U. Qualitative Sozialforschung: Eine Einführung. Reinbeck: Rowohlt; 2007.

- Groeben N, Wahl D, Schlee J, Scheele B. Das Forschungsprogramm Subjektive Theorien: Eine Einführung in die Psychologie des reflexiven Subjekts. Tübingen: Francke; 1988.

- Laucken U. Naive Verhaltenstheorie: Ein Ansatz zur Analyse des Konzeptrepertoires, mit dem im alltäglichen Lebensvollzug das Verhalten der Mitmenschen erklärt und vorhergesagt wird. Zugl.: Tübingen, Univ., Diss. 1st ed. Stuttgart: Klett; 1974.

- Dann H-D. Pädagogisches Verstehen: Subjektive Theorien und erfolgreiches Handeln von Lehrkräften. In: Reusser K, Reusser-Weyneth M, editors. Verstehen: Psychologischer Prozess und didaktische Aufgabe. Bern: Huber; 1994, p. 163–182.

- Flick U, Kardorff E von, Steinke I (eds.). Qualitative Forschung: Ein Handbuch. Reinbek: Rowohlt; 2015.

- Flick U, Kardorff E von, Steinke I. Was ist qualitative Forschung? Einleitung und Überblick. In: Flick, U; Kardorff, E. von; Steinke I. (Hg.), Qualitative Forschung: Ein Handbuch (11. Aufl., S. 13-29), p. 13–29.

- Krappmann L. Soziologische Dimensionen der Identität: Strukturelle Bedingungen für die Teilnahme an Interaktionsprozessen. Konzepte der Humanwissenschaften. 4th ed. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta; 1975.

- Witzel A. Das problemzentrierte Interview. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung 1985;1(1):0–25.

- Gee NR, Fine AH, Schuck S. Animals in Educational Settings: Research and Practice. In: Fine AH, editor. Handbook on Animal-Assisted Therapy: Foundations and Guidelines for Animal-Assisted Interventions, 4th ed. Burlington: Elsevier Science; 2015, p. 195–2010.

- Helfferich C. Die Qualität qualitativer Daten: Manual für die Durchführung qualitativer Interviews. 4th ed. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften / Springer; 2011.

- Dresing T, Pehl T. Praxisbuch Interview, Transkription & Analyse: Anleitung und Regelsysteme für qualitativ Forschende. Marburg: Eigenverlag; 2018.

- Kuckartz U. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Methoden, Praxis, Computerunterstützung. Grundlagentexte Methoden. 3rd ed. Weinheim: Beltz Juventa; 2016.

- Qualitätsnetzwerk Schulbegleithunde e.V. (2022). Available online: https://schulbegleithunde.de/kampagne-gleichwuerdigkeit/ (accessed on 20. June 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).