Submitted:

10 July 2023

Posted:

11 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

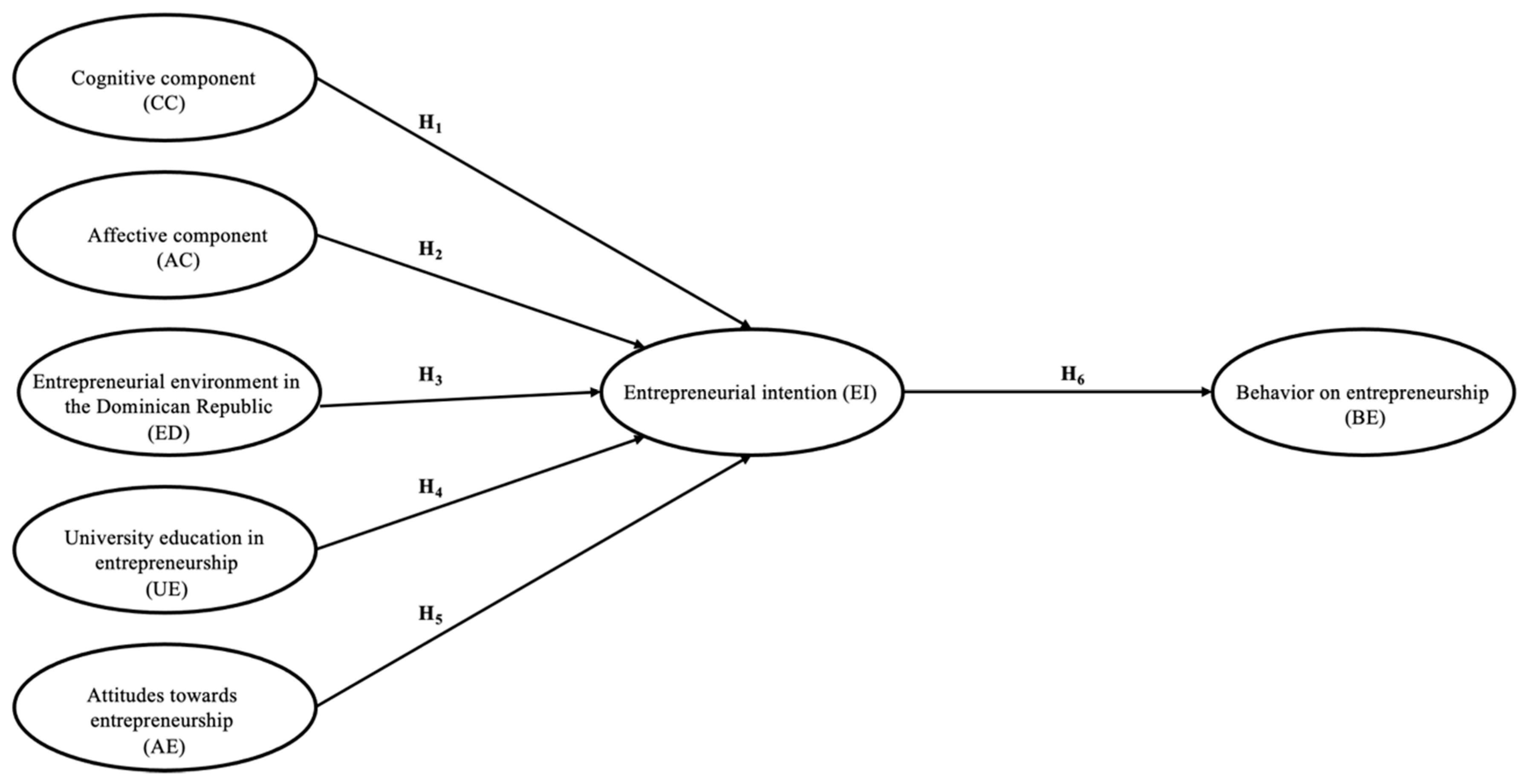

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

2.1. Cognitive and Affective Component of Entrepreneurial Intention

2.2. Business Environment, University Training in Entrepreneurship and Attitudes Towards Entrepreneurship on Entrepreneurship Intention

2.3. Entrepreneurial Intention and Entrepreneurial Behaviour

3. Methodology

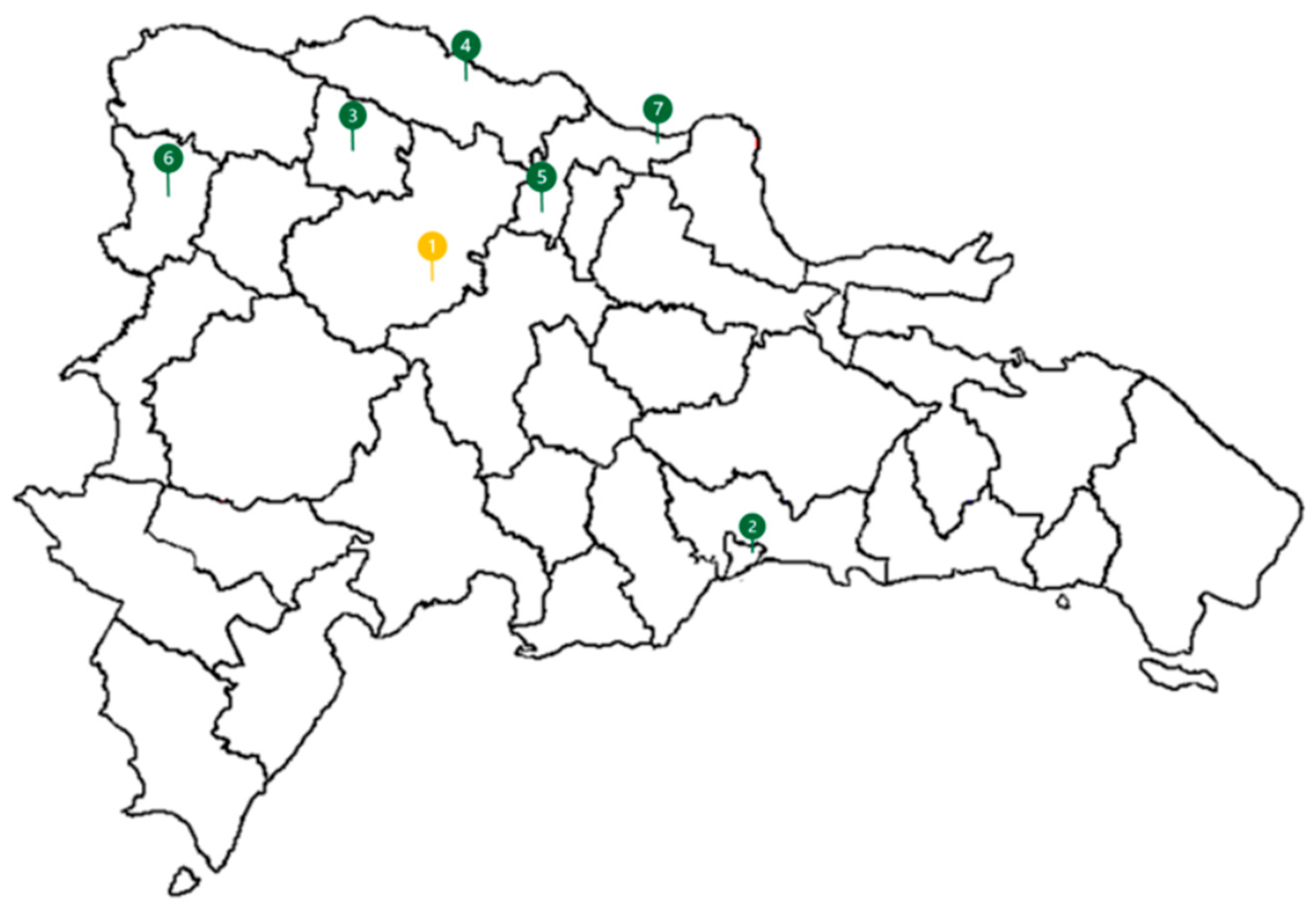

3.1. Context of the Study

3.2. Measurements

3.3. Data Collection and Sample Profile

3.4. Verification Strategy and Preliminary Data Analysis

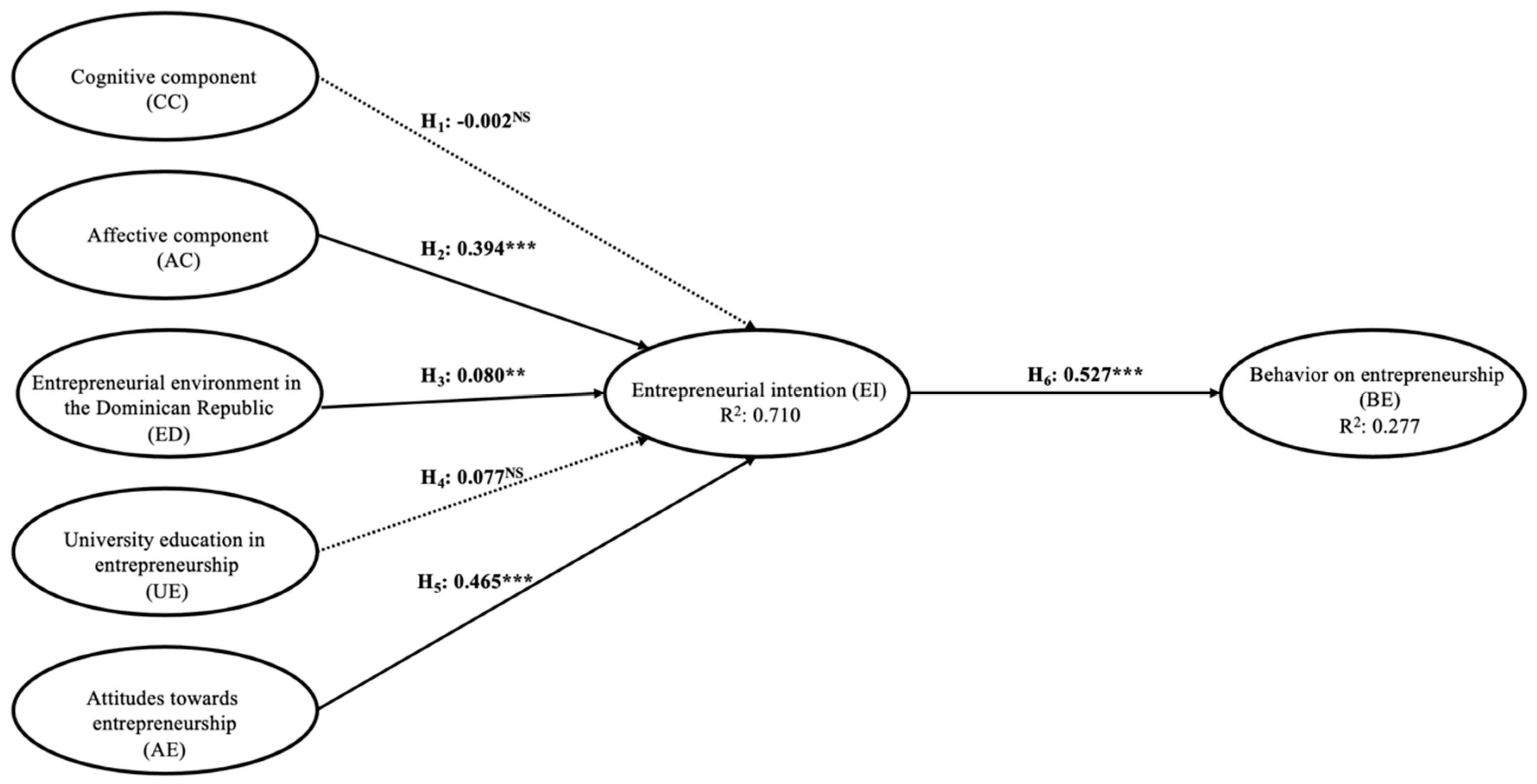

4. Results

4.1. Analysis of the Measurement Model

4.2. Analysis of the Structural Model

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Research Lines

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jena, R.K. Measuring the impact of business management Student's attitude towards entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intention: A case study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 107, 106275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez-Vega, U.; Muñiz-Umana, G.; José, A.; Santos-Corrada, M. Innovation as competitiveness driving force through the resources and capacities of SMEs in Costa Rica, Puerto Rico, and Dominican Republic. J. Small Bus. Strategy 2021, 31, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olarewaju, A.D.; Gonzalez-Tamayo, L.A.; Maheshwari, G.; Ortiz-Riaga, M.C. Student entrepreneurial intentions in emerging economies: Institutional influences and individual motivations. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2023, 30, 475–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Liu, X.; Sha, J. How does the entrepreneurship education influence the students' innovation? Testing on the multiple mediation model. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.; Hamilton, M.; Fabian, K. Entrepreneurial drivers, barriers and enablers of computing students: Gendered perspectives from an Australian and UK university. Stud. High. Educ. 2020, 45, 1892–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jubari, I.; Bahari, S.B.S.; Kamarudin, N.; Fadzli, A. Examining attitudinal determinants of startup intention among university students of hospitality and tourism. Int. J. Hum. Potentials Manag. 2019, 1, 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, A.T.; Do, T.H.H.; Vu, T.B.T.; Dang, K.A.; Nguyen, H.L. Factors affecting entrepreneurial intentions among youths in Vietnam. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 99, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobylinska, U.; Ryciuk, U. Selected contextual factors and entrepreneurial intentions of students on the example of Poland. Eng. Manag. Prod. Serv. 2022, 14, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koe, W.L. The relationship between individual entrepreneurial orientation (IEO) and entrepreneurial intention. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2016, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, I.B. Fostering an entrepreneurial mindset: A typology for aligning instructional strategies with three dominant entrepreneurial mindset conceptualizations. Ind. High. Educ. 2022, 36, 236–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hintikka, J.; Taipale-Erävala, K.; Lehtinen, U.; Eskola, L. Let’s be entrepreneurs – Finnish youth’s attitudes toward entrepreneurship. J. Enterp. Communities People Places Glob. Econ. 2023, 17, 856–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feola, R.; Vesci, M.; Botti, A.; Parente, R. The determinants of entrepreneurial intention of young researchers: Combining the theory of planned behavior with the triple helix model. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2019, 57, 1424–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, G. From green entrepreneurial intentions to green entrepreneurial behaviors: The role of university entrepreneurial support and external institutional support. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2021, 17, 963–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, T.; Farrukh, M.; Heidler, P.; Tautiva, J.A.D. Entrepreneurial intention: Creativity, entrepreneurship, and university support. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boubker, O.; Arroud, M.; Ouajdouni, A. Entrepreneurship education versus management students’ entrepreneurial intentions. A PLS-SEM approach. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2021, 19, 100450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, A.C. Experiential learning within the process of opportunity identification and exploitation. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2005, 29, 473–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.A. The role of affect in the entrepreneurial process. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 328–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.T.; Nguyen, T.N.Q.; Tran, Q.H.M. When giving is good for encouraging social entrepreneurship. Australas. Mark. J. (AMJ) 2020, 28, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayton, J.C.; Cholakova, M. The role of affect in the creation and intentional pursuit of entrepreneurial ideas. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2012, 36, 41–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragan, G.B.; Schin, G.C.; Sava, V.; Panait, A.A. Career path changer: The case of public and private sector entrepreneurial employee intentions. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2022, 28, 26–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Fernández, H.; Delgado-García, J.B.; Martín-Cruz, N.; Rodríguez-Escudero, A.I. The role of affect in the development of entrepreneurial intentions. Entrep. Res. J. 2020, 12, 20190124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavazos-Arroyo, J.; Puente-Díaz, R.; Agarwal, N. An examination of certain antecedents of social entrepreneurial intentions among Mexico residents. Rev. Bus. Manag. 2017, 19, 180–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aidis, R.; Estrin, S.; Mickiewicz, T. Institutions and entrepreneurship development in Russia: A comparative perspective. J. Bus. Ventur. 2008, 23, 656–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, E.J.; Wdowiak, M.A.; Almer-Jarz, D.A.; Breitenecker, R.J. The effects of attitudes and perceived environment conditions on students' entrepreneurial intent. Educ. Train. 2009, 51, 272–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krivokuća, M.; Ćoćkalo, D.; Bakator, M. The potential of digital entrepreneurship in Serbia. Anali Ekon. Fak. u Subotici 2021, 10.5937/AnEkSub2145097K, 97–115. [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Wu, L. The impact of higher education on entrepreneurial intentions of university students in China. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2008, 15, 752–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, S.; Yousafzai, S.; Yani-De-Soriano, M.; Muffatto, M. The role of perceived university support in the formation of students’ entrepreneurial intention. In Sustainable Entrepreneurship, Lindgreen, A., Vallaster, C., Maon, F., Yousafzai, S., Florencio, B.P., Eds. Routledge: London, 2018; pp. 3–23.

- Karimi, S.; Biemans, H.J.A.; Lans, T.; Chizari, M.; Mulder, M. The impact of entrepreneurship education: A study of Iranian students' entrepreneurial intentions and opportunity identification. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2016, 54, 187–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, R. Does university play significant role in shaping entrepreneurial intention? A cross-country comparative analysis. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2016, 23, 790–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.; Chowdhury, R.A.; Hoque, N.; Ahmad, A.; Mamun, A.; Uddin, M.N. Developing entrepreneurial intentions among business graduates of higher educational institutions through entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial passion: A moderated mediation model. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2022, 20, 100647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatten, T.S.; Ruhland, S.K. Student attitude toward entrepreneurship as affected by participation in an SBI program. J. Educ. Bus. 1995, 70, 224–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C. Demographic factors, family background and prior self-employment on entrepreneurial intention - Vietnamese business students are different: Why? J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2018, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, O.A.; Devesh, S.; Ubaidullah, V. Implication of attitude of graduate students in Oman towards entrepreneurship: An empirical study. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2017, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Păunescu, C.; Popescu, M.C.; Duennweber, M. Factors determining desirability of entrepreneurship in Romania. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien-Chi, C.; Sun, B.; Yang, H.; Zheng, M.; Li, B. Emotional competence, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial intention: A study based on China college students' social entrepreneurship project. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 547627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, H.; Lee, C.H.; Xiang, Y. Entrepreneurship education and students’ entrepreneurial intention in higher education. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israr, M.; Saleem, M. Entrepreneurial intentions among university students in Italy. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2018, 8, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, J.; Jin, Y.; Wang, T.; Lin, C.-L.; Xu, D. Factors influencing entrepreneurial intention of university students in China: Integrating the perceived university support and theory of planned behavior. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millman, C.; Li, Z.; Matlay, H.; Wong, W.C. Entrepreneurship education and students' internet entrepreneurship intentions. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2010, 17, 569–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J. The theory of planned behavior and prediction of entrepreneurial intention among Chinese undergraduates. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2013, 41, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinnar, R.S.; Hsu, D.K.; Powell, B.C.; Zhou, H. Entrepreneurial intentions and start-ups: Are women or men more likely to enact their intentions? Int. Small Bus. J. 2018, 36, 60–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neneh, B.N. From entrepreneurial alertness to entrepreneurial behavior: The role of trait competitiveness and proactive personality. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2019, 138, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayolle, A.; Gailly, B. The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial attitudes and intention: Hysteresis and persistence. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2015, 53, 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirokova, G.; Osiyevskyy, O.; Bogatyreva, K. Exploring the intention–behavior link in student entrepreneurship: Moderating effects of individual and environmental characteristics. Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 34, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceresia, F.; Mendola, C. Entrepreneurial self-identity, perceived corruption, exogenous and endogenous obstacles as antecedents of entrepreneurial intention in Italy. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Murad, M.; Shahzad, F.; Khan, M.A.S.; Ashraf, S.F.; Dogbe, C.S.K. Entrepreneurial passion to entrepreneurial behavior: Role of entrepreneurial alertness, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and proactive personality. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Dominican Republic: Overview. Available online: https://www.bancomundial.org/es/country/dominicanrepublic/overview. (accessed on 19 March 2023).

- Tshikovhi, N.; Shambare, R. Entrepreneurial knowledge, personal attitudes, and entrepreneurship intentions among South African Enactus students. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2015, 13, 152–158. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, I.A.; Amjed, S.; Jaboob, S. The moderating role of entrepreneurship education in shaping entrepreneurial intentions. J. Econ. Struct. 2020, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Guenther, P.; Guenther, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Zaefarian, G.; Cartwright, S. Improving PLS-SEM use for business marketing research. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2023, 111, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Alamer, A. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) in second language and education research: Guidelines using an applied example. Res. Methods Appl. Linguist. 2022, 1, 100027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigdon, E.E.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. On comparing results from CB-SEM and PLS-SEM: Five perspectives and five recommendations. Mark. ZFP J. Res. Manag. 2017, 39, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. Evaluation of the structural model. In Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook, Hair, J.F., Hult, G.T.M., Ringle, C.M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N.P., Ray, S., Eds. Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 115–138.

- Hair, J.F.; Matthews, L.M.; Matthews, R.L.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated guidelines on which method to use. Int. J. Multivar. Data Anal. 2017, 1, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.M. SmartPLS 3. SmartPLS GmbH, boenningstedt. J. Serv. Sci. Manag. 2015, 10, 32–49. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, F.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Ryu, K. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) in hospitality research. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 514–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W.; Marcolin, B.L.; Newsted, P.R. A partial least squares latent variable modeling approach for measuring interaction effects: Results from a Monte Carlo simulation study and an electronic-mail emotion/adoption study. Inf. Syst. Res. 2003, 14, 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorrell, G.; Ford, N.; Madden, A.; Holdridge, P.; Eaglestone, B. Countering method bias in questionnaire-based user studies. J. Doc. 2011, 67, 507–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, A.H.; Malhotra, A.; Segars, A.H. Knowledge management: An organizational capabilities perspective. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2001, 18, 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Hubona, G.; Ray, P.A. Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Academic Press: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Pérez, V.; Montes-Merino, A.; Rodríguez-Ariza, L.; Galicia, P.E.A. Emotional competencies and cognitive antecedents in shaping student’s entrepreneurial intention: The moderating role of entrepreneurship education. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2019, 15, 281–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.; Obschonka, M.; Schwarz, S.; Cohen, M.; Nielsen, I. Entrepreneurial self-efficacy: A systematic review of the literature on its theoretical foundations, measurement, antecedents, and outcomes, and an agenda for future research. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 110, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Lin, C.; Zhao, G.; Zhao, D. Research on the effects of entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial self-efficacy on college students' entrepreneurial intention. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Mean | SD | Norm. | Cronbach | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavior on entrepreneurship (BE) | 0.875 | ||||

| BE1 | I enjoy the lectures on entrepreneurship provided at the university | 3.83 | 1.210 | 0.000C | |

| BE2 | The lectures on entrepreneurship I received at the university have increased my interest in pursuing an entrepreneurial career | 3.87 | 1.173 | 0.000C | |

| BE3 | I consider entrepreneurship as a very important subject at the university | 4.50 | 0.889 | 0.000C | |

| BE4 | The entrepreneurial subjects I have taken at university have prepared me to make decisions to pursue an entrepreneurial career. | 3.88 | 1.132 | 0.000C | |

| BE5 | I am happy to have had a business education at my university | 4.13 | 1.133 | 0.000C | |

| BE6 | I sincerely consider entrepreneurship as a desired career option | 4.23 | 0.935 | 0.000C | |

| BE7 | The entrepreneurship education I have received at university will encourage me to venture into entrepreneurship after graduation. | 4.02 | 1.066 | 0.000C | |

| BE8 | My entrepreneurship teachers have helped me to meet and interact with successful entrepreneurs. | 3.71 | 1.208 | 0.000C | |

| BE9 | The entrepreneurship staff at my university helps students meet successful entrepreneurs who motivate them to become entrepreneurs. | 3.59 | 1.221 | 0.000C | |

| Cognitive component (CC) | 0.937 | ||||

| CC1 | The entrepreneurship courses have enabled me to identify business-related opportunities. | 4.01 | 1.042 | 0.000C | |

| CC2 | Entrepreneurship subjects have taught me how to create services and/or products that can meet the needs of customers. | 3.88 | 1.138 | 0.000C | |

| CC3 | The entrepreneurship courses have taught me how to develop successful business plans. | 3.82 | 1.137 | 0.000C | |

| CC4 | Due to entrepreneurship subjects, I now have skills to create a new business. | 3.98 | 1.142 | 0.000C | |

| CC5 | With entrepreneurship subjects, I can now successfully identify sources of business opportunities. | 3.95 | 1.037 | 0.000C | |

| CC6 | The entrepreneurship courses have taught me how to carry out feasibility studies. | 3.85 | 1.088 | 0.000C | |

| CC7 | Entrepreneurship subjects have stimulated my interest in entrepreneurship. | 4.08 | 1.087 | 0.000C | |

| CC8 | Through entrepreneurship subjects, my skills, knowledge and interest in entrepreneurship have improved. | 4.11 | 1.047 | 0.000C | |

| CC9 | Overall, I am very satisfied with the way entrepreneurship subjects are taught at my university. | 3.92 | 1.196 | 0.000C | |

| Affective component (AC) | 0.762 | ||||

| AC1 | I would like to be an entrepreneur after my studies. | 4.56 | 0.861 | 0.000C | |

| AC2 | I am attracted by the idea of becoming an entrepreneur and working for myself. | 4.60 | 0.797 | 0.000C | |

| AC3 | I really consider self-employment as something very important | 4.63 | 0.717 | 0.000C | |

| AC4 | The entrepreneurship subjects at university have effectively prepared me to establish a career in entrepreneurship. | 3.94 | 1.124 | 0.000C | |

| Entrepreneurial intention (EI) | 0.867 | ||||

| EI1 | A career as an entrepreneur is attractive to me | 4.31 | 0.952 | 0.000C | |

| EI2 | If I had the resources, I would like to start a business | 4.66 | 0.728 | 0.000C | |

| EI3 | The people I care about would approve of my intention to become an entrepreneur. | 4.57 | 0.698 | 0.000C | |

| EI4 | Most people who are important to me would approve of me becoming an entrepreneur. | 4.57 | 0.689 | 0.000C | |

| EI5 | Being an entrepreneur gives me satisfaction | 4.49 | 0.824 | 0.000C | |

| EI6 | Being an entrepreneur gives me more advantages than disadvantages | 4.38 | 0.848 | 0.000C | |

| EI7 | I prefer to be an entrepreneur among several options | 4.33 | 0.902 | 0.000C | |

| Entrepreneurial environment in the Dominican Republic (ED) | 0.775 | ||||

| ED1 | The Dominican Republic is an excellent country to start a business | 3.67 | 1.114 | 0.000C | |

| ED2 | Local government supports entrepreneurs | 3.11 | 1.198 | 0.000C | |

| ED3 | It would be very difficult to raise the money to start a new business in the Dominican Republic. | 3.58 | 1.098 | 0.000C | |

| ED4 | I know how to access the assistance I need to start a new business. | 3.48 | 1.153 | 0.000C | |

| ED5 | I am aware of the programmes offered by the country to help people start businesses | 2.99 | 1.328 | 0.000C | |

| University education in entrepreneurship (EU) | 0.862 | ||||

| EU1 | The subject of business organization gave me new knowledge about entrepreneurship | 3.98 | 1.129 | 0.000C | |

| EU2 | The entrepreneurship training course provided me with new knowledge about entrepreneurship. | 4.22 | 1.047 | 0.000C | |

| EU3 | The undergraduate thesis proposal course gave me new knowledge about entrepreneurship. | 4.27 | 1.026 | 0.000C | |

| EU4 | The graduate thesis proposal course gave me new knowledge about entrepreneurship. | 4.36 | 1.010 | 0.000C | |

| Attitudes towards entrepreneurship (AE) | 0.881 | ||||

| AE1 | If I had the opportunity, I would like to start a company | 4.63 | 0.745 | 0.000C | |

| AE2 | Being an entrepreneur would give me great satisfaction | 4.58 | 0.747 | 0.000C | |

| AE3 | Becoming an entrepreneur appeals to me | 4.52 | 0.796 | 0.000C | |

| Indicators/compounds | Loads (Sig.) | r_A | rC | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affective component (AC) AC1 AC2 AC3 AC4 |

0.873 0.901 0.845 0.511 |

0.844 | 0.871 | 0.638 |

| Cognitive component (CC) CC1 CC2 CC3 CC4 CC5 CC6 CC7 CC8 CC9 |

0.795 0.799 0.813 0.853 0.824 0.799 0.828 0.847 0.792 |

0.942 | 0.948 | 0.667 |

|

Entrepreneurial environment in the Dominican Republic (ED) ED1 ED2 ED3 ED4 ED5 |

0.786 0.811 0.528 0.750 0.699 |

0.816 | 0.842 | 0.521 |

| Entrepreneurial intention (EI) EI1 EI2 EI3 EI4 EI5 EI6 EI7 |

0.759 0.742 0.659 0.696 0.867 0.761 0.740 |

0.880 | 0.899 | 0.561 |

| Attitudes towards entrepreneurship (AE) AE1 AE2 AE3 |

0.873 0.900 0.923 |

0.884 | 0.926 | 0.808 |

| Behavior on entrepreneurship (BE) BE1 BE2 BE3 BE4 BE5 BE6 BE7 BE8 BE9 |

0.720 0.762 0.630 0.753 0.818 0.614 0.780 0.627 0.769 |

0.877 | 0.898 | 0.515 |

| University education in entrepreneurship (EU) EU1 EU2 EU3 EU4 |

0.841 0.868 0.849 0.806 |

0.863 | 0.906 | 0.708 |

| Discriminant Validity (HT-MT Ratio) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC | AE | CC | BE | ED | EI | EU | |

| AC | |||||||

| AE | 0.743 | ||||||

| CC | 0.640 | 0.388 | |||||

| BE | 0.695 | 0.433 | 0.885 | ||||

| ED | 0.388 | 0.258 | 0.619 | 0.560 | |||

| EI | 0.872 | 0.857 | 0.493 | 0.562 | 0.379 | ||

| EU | 0.627 | 0.429 | 0.848 | 0.797 | 0.555 | 0.530 | |

| Hypothesis | b | R2 | f2(Sig.) | Correlation | Explained variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EI H1: CC H2: AC H3: ED H4: EU H5: AE BE H6: EI |

´ 0.002 0.394 0.080 0.077 0.465 0.527 |

0.710 0.277 |

0.000(0.999) 0.276(0.006) 0.016(0.289) 0.008(0.498) 0.441(0.000) 0.384(0.000) |

0.460 0.745 0.340 0.471 0.761 0.527 |

-0.092% 29.35% 2.72% 3.62% 35.38% 27.77% |

| Hypothesis put forward | b | t(p.lim.) | IC95% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5% | 97.5% | |||

| H1: CC → EI | -0.002NS | 0.041(0.967) | -0.087 | 0.086 |

| H2: AC → EI | 0.394*** | 6.471(0.000) | 0.273 | 0.511 |

| H3: ED → EI | 0.080** | 2.341(0.019) | 0.017 | 0.152 |

| H4: EU → EI | 0.077NS | 1.49(0.135) | -0.023 | 0.179 |

| H5: AE → EI | 0.465*** | 9.431(0.000) | 0.369 | 0.561 |

| H6: EI → BE | 0.527*** | 12.941(0.000) | 0.449 | 0.607 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).