Submitted:

10 July 2023

Posted:

11 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

I. Introduction

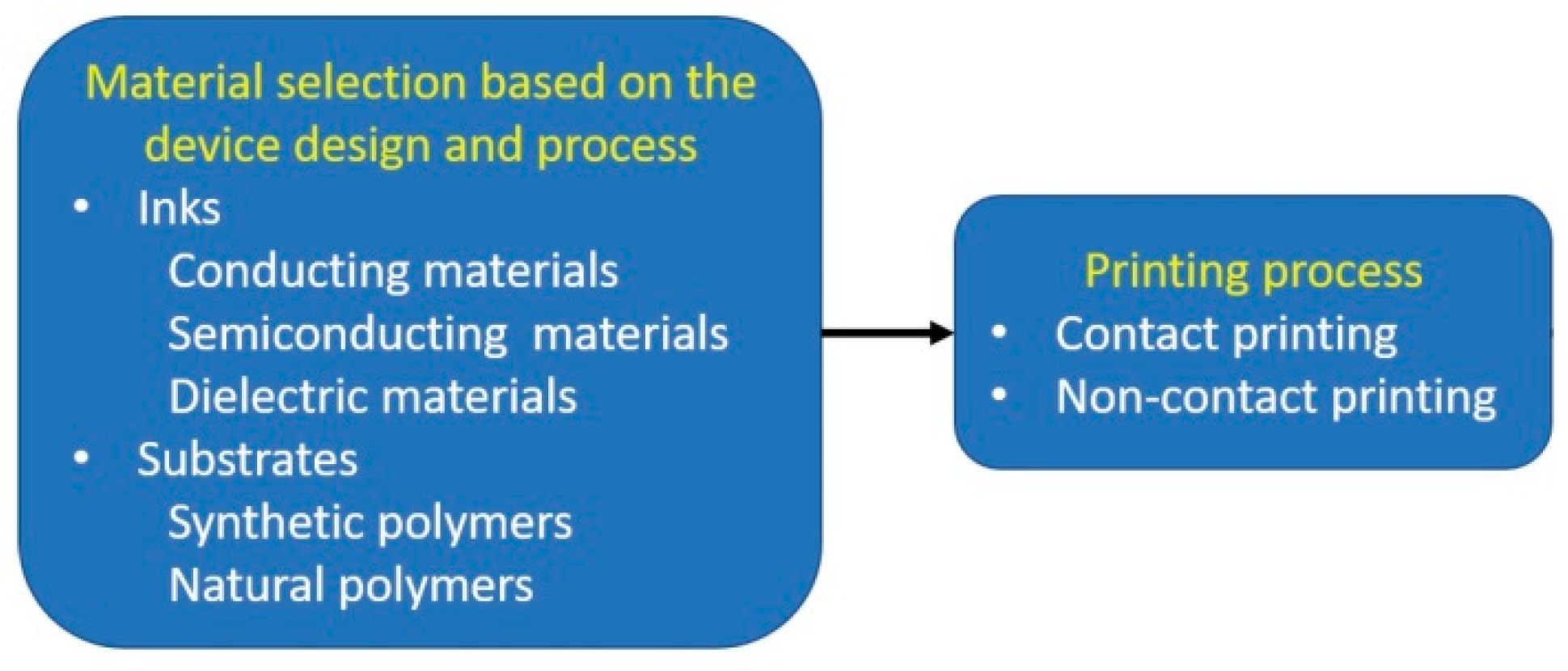

II. Materials for Printed Photonic Devices

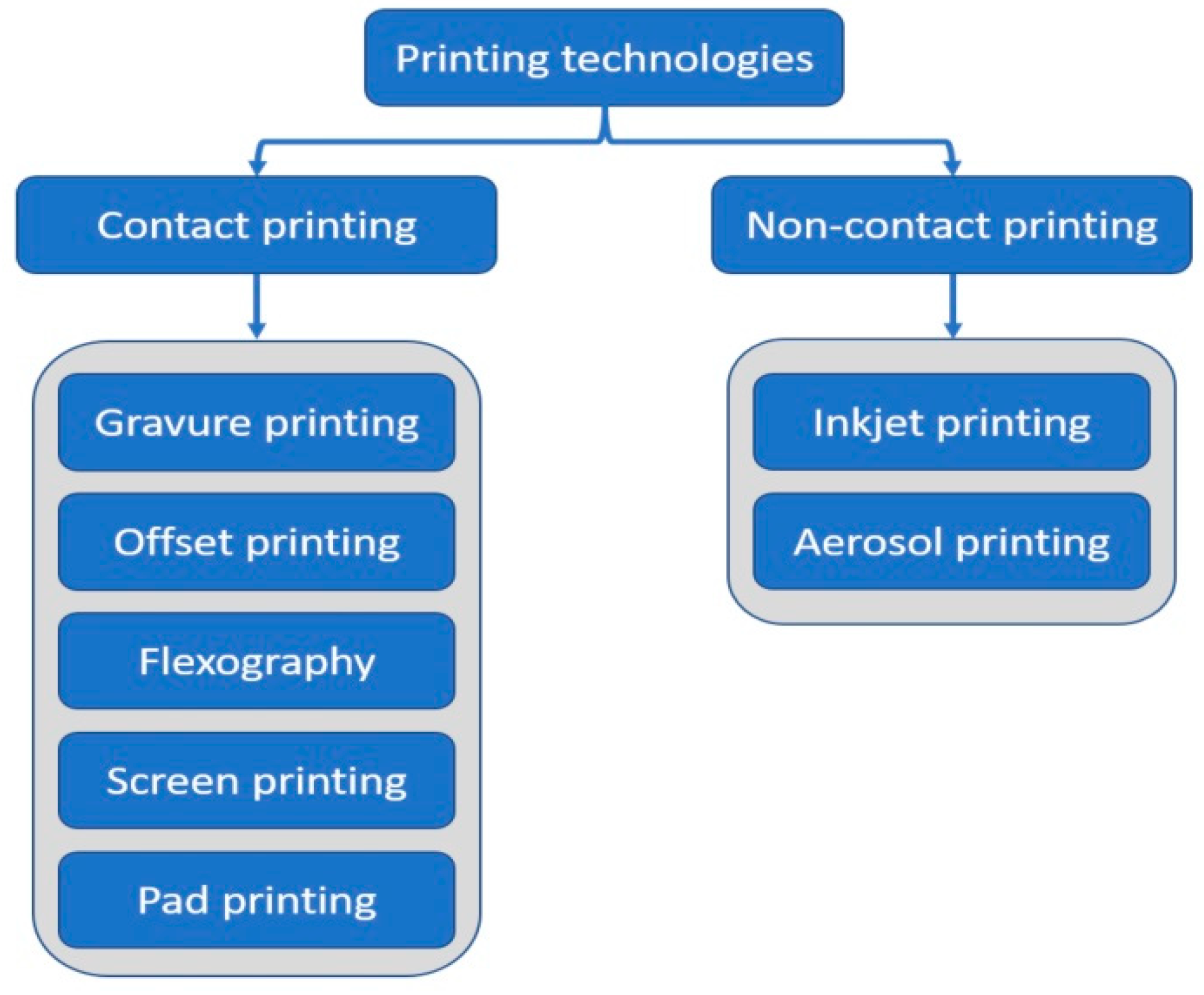

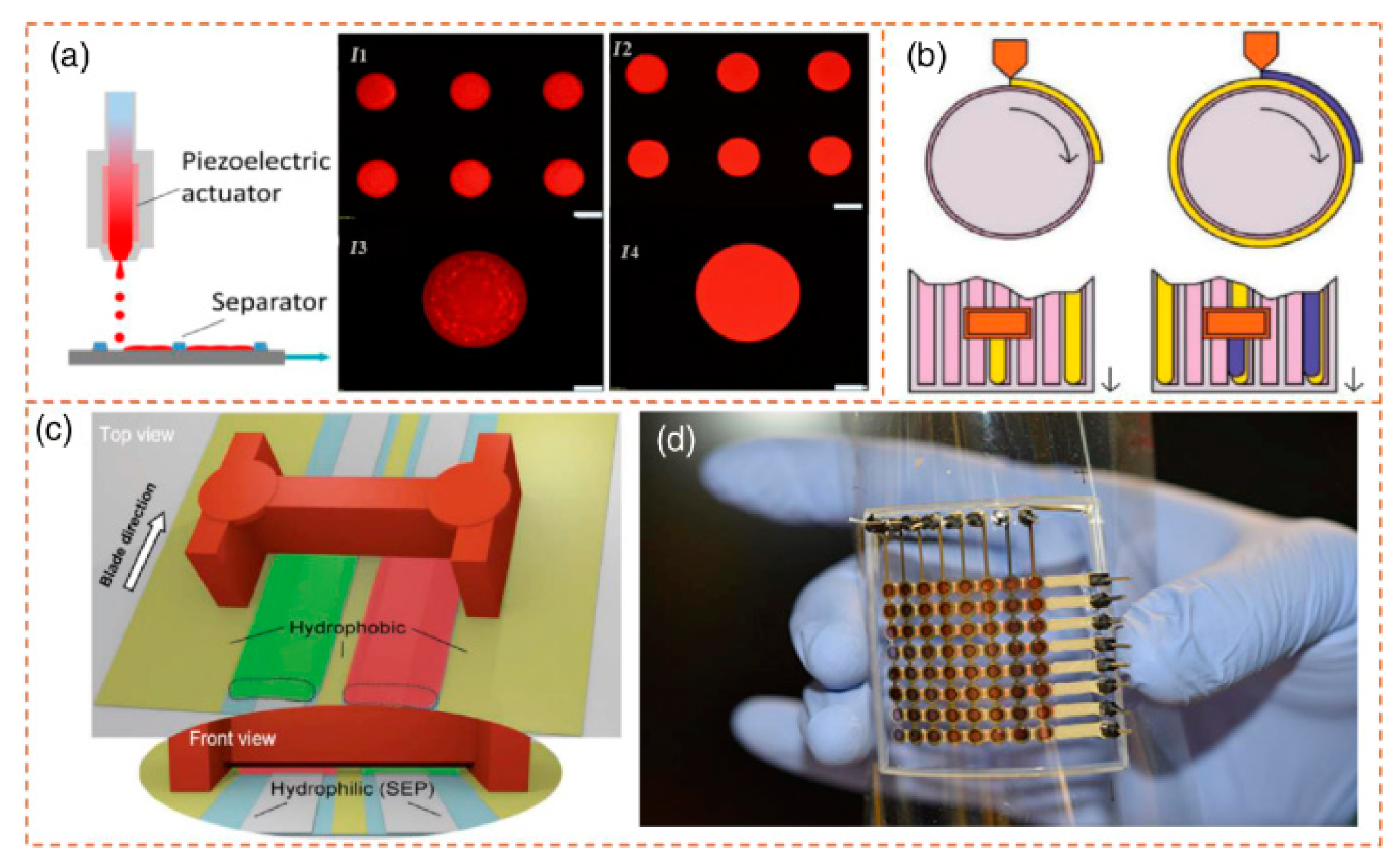

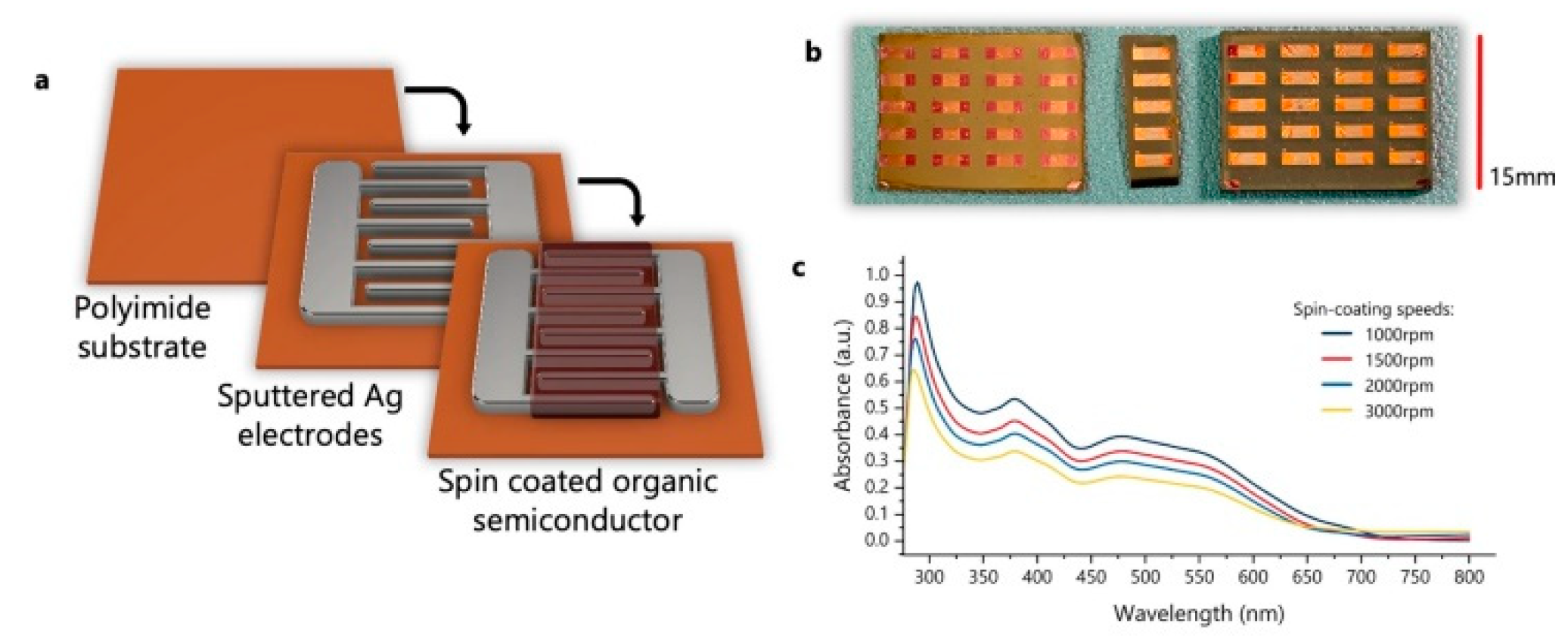

III. Printing Techniques for Photonic Devices

IV. Device components and their use in Printed Photonic Devices

V. Applications of Printed Photonic Devices

VI. Challenges and Future Perspectives for Printed Photonic Devices

VII. Conclusion

Funding

Acknowledgments

References

- S. Chung, K. Cho, and T. Lee. Recent Progress in Inkjet-Printed Thin-Film Transistors. Advanced Science, 2019, 6, 1801445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A. Awad, F. Fina, A. Goyanes, S. Gaisford, and A. W. Basit Advances in Powder Bed Fusion 3D Printing in Drug Delivery and Healthcare. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2021, 174, 406–424. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J. Zhu, P. Wu, Y. Chao, J. Yu, W. Zhu, Z. Liu, and C. Xu, Recent Advances in 3D Printing for Catalytic Applications. Chemical Engineering Journal 2022, 433, 134341. [CrossRef]

- Z. Xia, T. Cai, X. Li, Q. Zhang, J. Shuai, and S. Liu Recent Progress of Printing Technologies for High-Efficient Organic Solar Cells. Catalysts 2023, 13, 156. [CrossRef]

- M. E. Prendergast, and J. A. Burdick. Recent Advances in Enabling Technologies in 3D Printing for Precision Medicine. Advanced Materials 2020, 32, 1902516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. F. Fernandes, C. Majidi, and M. Tavakoli. Digitally Printed Stretchable Electronics: A Review. J. Mater. Chem. C 2019, 7, 14035–14068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. L. O. Júnior, R. M. Neves, F. M. Monticeli. and L. Dall Agnol, Smart Fabric Textiles: Recent Advances and Challenges. Textiles, 2022, 2, 582–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H.-L. Kao, C.-H. Chuang, and C.-L. Cho, “Inkjet-Printed Filtering Antenna on a Textile for Wearable Applications,” in 2019 IEEE 69th Electronic Components and Technology Conference (ECTC), 2019, pp. 258–263.

- X. Du, S. P. Wankhede, S. Prasad. A. Shehri, J. Morse, and N. Lakal A Review of Inkjet Printing Technology for Personalized-Healthcare Wearable Devices. J. Mater. Chem. C 2022, 10, 14091–14115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Borghetti, E. Cantù, E. Sardini. and M. Serpellon Future Sensors for Smart Objects by Printing Technologies in Industry 4.0 Scenario. Energies 2020, 13, 5916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. C. Righini, J. Krzak, A. Lukowiak, G. Macrelli, S. Varas, and M. Ferrari From Flexible Electronics to Flexible Photonics: A Brief Overview. Optical Materials 2021, 115, 111011. [CrossRef]

- H. Kajii, M. Yoshinaga, T. Karaki, M. Kawata, H. Okui, M. Morifuji, and M. Kondow, “Invited: Polymer Light-Emitting Devices with Selectively Transparent Photonic Crystals Consisting of Printed Inorganic/Organic Hybrid Dielectric Films,” in 2019 IEEE International Meeting for Future of Electron Devices, Kansai (IMFEDK), 2019, pp. 31–34.

- J. Manzi, A. E. Weltner, T. Varghese, N. McKibben, M. Busuladzic-Begic, D. Estrada, and H. Subbaraman, “Plasma-Jet Printing of Colloidal Thermoelectric Bi2Te3 Nanoflakes for Flexible Energy Harvesting,” Nanoscale, 2023, 15, 6596–6606.

- M. Saeidi-Javash, W. Kuang, C. Dun, and Y. Zhang, “3D Conformal Printing and Photonic Sintering of High-Performance Flexible Thermoelectric Films Using 2D Nanoplates,” Advanced Functional Materials, 2019, 29, 1901930. [CrossRef]

- Dadras-Toussi, V. Raghunathan, S. Majd, and M. R. Abidian, “Direct Laser 3D Printing of Organic Semiconductor Microdevices for Bioelectronics and Biosensors,” in 2022 44th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), 2022, pp. 1569–1572.

- L. Zhang, H. Yang, Y. Tang, W. Xiang, C. Wang, T. Xu, X. Wang, M. Xiao, and J. Zhang, “High-Performance CdSe/CdS@ZnO Quantum Dots Enabled by ZnO Sol as Surface Ligands: A Novel Strategy for Improved Optical Properties and Stability,” Chemical Engineering Journal, vol. 428, pp. 131159, 2022.

- Y. Ji, W. Xu, I. L. Rasskazov, H. Liu, J. Hu, M. Liu, D. Zhou, X. Bai, H. Ågren, and H. Song, “Perovskite Photonic Crystal Photoelectric Devices,” Applied Physics Reviews, 2022, 9, 041319. [CrossRef]

- H. Fudouzi and Y. Xia, “Colloidal crystals with tunable colors and their use as photonic papers,” Langmuir, 2003, 19, 9653–9660. [CrossRef]

- K. Kumar, H. Duan, R. S. Hegde, S. C. Koh, J. N. Wei, and J. K. Yang, “Printing color at the optical diffraction limit,” Nat. Nanotechnol., 2012, 7, 557–561.

- S. Ye, Q. Fu, and J. Ge, “Invisible Photonic Prints Shown by Deformation,” Advanced Functional Materials, 2014, 24, 6430–6438. [CrossRef]

- S. Sun, Z. Zhou, C. Zhang, Y. Gao, Z. Duan, S. Xiao, and Q. Song, “All-dielectric full-color printing with TiO2 metasurfaces,” ACS Nano, 2017, 11, 4445–4452.

- H. Kim, J. Ge, J. Kim, S.-E. Choi, H. Lee, H. Lee, W. Park, Y. Yin, and S. Kwon, “Structural colour printing using a magnetically tunable and lithographically fixable photonic crystal,” Nat. Photonics, 2009, 3, 534–540. [CrossRef]

- S. D. Smith, “Lasers, Nonlinear Optics and Optical Computers,” Nature, 1985, 316, 319–324. [CrossRef]

- R. Yan, P. Pausauskie, J. Huang, and P. Yang, “Direct Photonic–Plasmonic Coupling and Routing in Single Nanowires,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2009, 106, 21045–21050. [CrossRef]

- M. Law, D. J. Sirbuly, J. C. Johnson, J. Goldberger, R. J. Saykally, and P. Yang, “Nanoribbon Waveguides for Subwavelength Photonics Integration,” Science, 2004, 305, 1269–1273. [CrossRef]

- J. L. O’Brien, A. Furusawa, and J. Vučković, “Photonic Quantum Technologies,” Nature Photon, 2009, 3, 687–695. [CrossRef]

- C. J. Barrelet, A. B. Greytak, and C. M. Lieber, “Nanowire Photonic Circuit Elements,” Nano Lett., 2004, 4, 1981–1985. [CrossRef]

- W. L. Barnes, A. Dereux, and T. W. Ebbesen, “Surface Plasmon Subwavelength Optics,” Nature, 2003, 424, 824–830. [CrossRef]

- D. J. Sirbuly, M. Law, P. Pauzauskie, H. Yan, A. V. Maslov, K. Knutsen, C.-Z. Ning, R. J. Saykally, and P. Yang, “Optical Routing and Sensing with Nanowire Assemblies,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2005, 102, 7800–7805. [CrossRef]

- P. A. Winckler, “Reader in the History of Books and Printing,” Greenwood Publishing Group; Information Handling Services: Englewood, CO, USA, vol. 26, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- K. Busch, S. K. Busch, S. Lölkes, R. B. Wehrspohn, and H. Föll (Eds.), Photonic Crystals: Advances in Design, Fabrication, and Characterization. Somerset, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2006.

- D. Sundaramurthi, S. D. Sundaramurthi, S. Rauf, and C. Hauser, “3D Bioprinting Technology for Regenerative Medicine Applications,” 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. Soref, “The Past, Present, and Future of Silicon Photonics,” IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics, 2006, 12, 1678–1687.

- M. Del Pozo, J. A. H. P. Sol, A. P. H. J. Schenning, and M. G. Debije, “4D Printing of Liquid Crystals: What’s Right for Me?,” Advanced Materials, 2022, 34, 2104390.

- F. P. W. Melchels, J. Feijen, and D. W. Grijpma, “A Review on Stereolithography and Its Applications in Biomedical Engineering,” Biomaterials, 2010, 31, 6121–6130. [CrossRef]

- B. Derby, “Printing and Prototyping of Tissues and Scaffolds,” Science, 2012, 338, 921–926. [CrossRef]

- C. N. LaFratta, J. T. Fourkas, T. Baldacchini, and R. A. Farrer, “Multiphoton Fabrication,” Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 2007, 46, 6238–6258.

- J. Fischer and M. Wegener, “Three-Dimensional Optical Laser Lithography beyond the Diffraction Limit,” Laser & Photonics Reviews, 2013, 7, 22–44. [CrossRef]

- Z. Cui, Printed Electronics: Materials, Technologies and Applications. John Wiley & Sons, 2016.

- L. Liu, Z. L. Liu, Z. Shen, X. Zhang, and H. Ma, “Highly Conductive Graphene/Carbon Black Screen Printing Inks for Flexible Electronics,” Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, vol. 582, pp. 12–21, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. L. Morgan, D. J. Curtis, and D. Deganello, “Control of Morphological and Electrical Properties of Flexographic Printed Electronics through Tailored Ink Rheology,” Organic Electronics, vol. 73, pp. 212–218, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Verboven and, W. Deferme, “Printing of Flexible Light Emitting Devices: A Review on Different Technologies and Devices, Printing Technologies and State-of-the-Art Applications and Future Prospects,” Progress in Materials Science, vol. 118, p. 100760, 2021.

- P. G. V. Sampaio, M. O. A. González, P. de Oliveira Ferreira, P. da Cunha Jácome Vidal, J. P. P. Pereira, H. R. Ferreira, and P. C. Oprime, “Overview of Printing and Coating Techniques in the Production of Organic Photovoltaic Cells,” International Journal of Energy Research, 2020, 44, 9912–9931. [CrossRef]

- L. Jiang, A. Nishant, J. Frish, T. S. Kleine, L. Brusberg, R. Himmelhuber, K.-J. Kim, J. Pyun, S. Pau, R. A. Norwood, T. L. Koch, “SmartPrint Single-Mode Flexible Polymer Optical Interconnect for High Density Integrated Photonics,” J. Lightwave Technol., JLT, 2022, 40, 3839–3844. [CrossRef]

- S. Khan, S. Ali, and A. Bermak, “Recent Developments in Printing Flexible and Wearable Sensing Electronics for Healthcare Applications,” Sensors, 2019, 19, 1230. [CrossRef]

- G. Reddy, R. Katakam, K. Devulapally, L. A. Jones, E. D. Gaspera, H. M. Upadhyaya, N. Islavath, and L. Giribabu, “Ambient Stable, Hydrophobic, Electrically Conductive Porphyrin Hole-Extracting Materials for Printable Perovskite Solar Cells,” J. Mater. Chem. C, 2019, 7, 4702–4708. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, R. Brito-Pereira, B. F. Gonçalves, I. Etxebarria, and S. Lanceros-Mendez, “Recent Developments on Printed Photodetectors for Large Area and Flexible Applications,” Organic Electronics, vol. 66, pp. 216–226, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Scott and Z. Ali, “Fabrication Methods for Microfluidic Devices: An Overview,” Micromachines, 2021, 12, 319. [CrossRef]

- E. S. Rosker, R. E. S. Rosker, R. Sandhu, J. Hester, M. S. Goorsky, and J. Tice, “Printable Materials for the Realization of High Performance RF Components: Challenges and Opportunities,” International Journal of Antennas and Propagation, vol. 2018, p. e9359528, 2018. [CrossRef]

- B. R. Hunde and A. D. Woldeyohannes, “3D Printing and Solar Cell Fabrication Methods: A Review of Challenges, Opportunities, and Future Prospects,” Results in Optics, vol. 11, p. 100385, 2023.

- Wiklund, A. Karakoç, T. Palko, H. Yiğitler, K. Ruttik, R. Jäntti, and J. Paltakari, “A Review on Printed Electronics: Fabrication Methods, Inks, Substrates, Applications and Environmental Impacts,” J. Manuf. Mater. Process., 2021, 5, 89. [Google Scholar]

- C. H. Rao, K. Avinash, B. K. S. V. L. Varaprasad, and S. Goel, “A Review on Printed Electronics with Digital 3D Printing: Fabrication Techniques, Materials, Challenges and Future Opportunities,” J. Electron. Mater., 2022, 51, 2747–2765.

- C. Tong, “Printed Flexible Organic Light-Emitting Diodes,” in Advanced Materials for Printed Flexible Electronics, C. Tong, Ed. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2022, pp. 347-399. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S. Masoumi, D. Gedefaw, S. O’Shaughnessy, D. Baran, and A. Pakdel, “Flexible Solar and Thermal Energy Conversion Devices: Organic Photovoltaics (OPVs), Organic Thermoelectric Generators (OTEGs) and Hybrid PV-TEG Systems,” Applied Materials Today, vol. 29, p. 101614, 2022.

- J. Lee, J.-M. Lee, A. Facchetti, T. J. Marks, and S. K. Park, “Recent Advances in Low-Dimensional Nanomaterials for Photodetectors,” Small Methods, vol. n/a, no. n/a, p. 2300246. [CrossRef]

- X. Chen, X. Wang, Y. Pang, G. Bao, J. Jiang, P. Yang, Y. Chen, T. Rao, and W. Liao, “Printed Electronics Based on 2D Material Inks: Preparation, Properties, and Applications toward Memristors,” Small Methods, 2023, 7, 2201156.

- Y. Fukuta, T. Miyata, and Y. Hamanaka, “Fabrication of Two-Dimensional Hybrid Organic–Inorganic Lead Halide Perovskites with Controlled Multilayer Structures by Liquid-Phase Laser Ablation,” J. Mater. Chem. C, 2023, 11, 910–916. [CrossRef]

- S. Park, W. Shou, L. Makatura, W. Matusik, and K. (Kelvin) Fu, “3D Printing of Polymer Composites: Materials, Processes, and Applications,” Matter, 2022, 5, 43–76.

- X. -Y. Han, Z.-L. Wu, S.-C. Yang, F.-F. Shen, Y.-X. Liang, L.-H. Wang, J.-Y. Wang, J. Ren, L.-Y. Jia, H. Zhang, S.-H. Bo, G. Morthier, and M.-S. Zhao, “Recent Progress of Imprinted Polymer Photonic Waveguide Devices and Applications,” Polymers, 2018, 10, 603. [CrossRef]

- W. Wu, “Inorganic Nanomaterials for Printed Electronics: A Review,” Nanoscale, vol. 9, 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Parola, B. Julián-López, L. D. Carlos, and C. Sanchez, “Optical Properties of Hybrid Organic-Inorganic Materials and Their Applications,” in Advanced Functional Materials, 2016, 26, 6506–6544.

- C. Lee and P. J. Schuck, “Photodarkening, Photobrightening, and the Role of Color Centers in Emerging Applications of Lanthanide-Based Upconverting Nanomaterials,” in Annual Review of Physical Chemistry, 2023, 74, 415–438. [CrossRef]

- K. -S. Kwon, M. K. Rahman, T. H. Phung, S. D. Hoath, S. Jeong, and J. S. Kim, “Review of Digital Printing Technologies for Electronic Materials,” in IEEE Transactions on Flexible Electronics, 2020, 5, 043003. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yao, X. Xia, Z. Cheng, K. Wei, X. Jiang, J. Dong, and H. Zhang, “All-Optical Modulator Using MXene Inkjet-Printed Microring Resonator,” in IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics, 2020, 26, 1–6. [CrossRef]

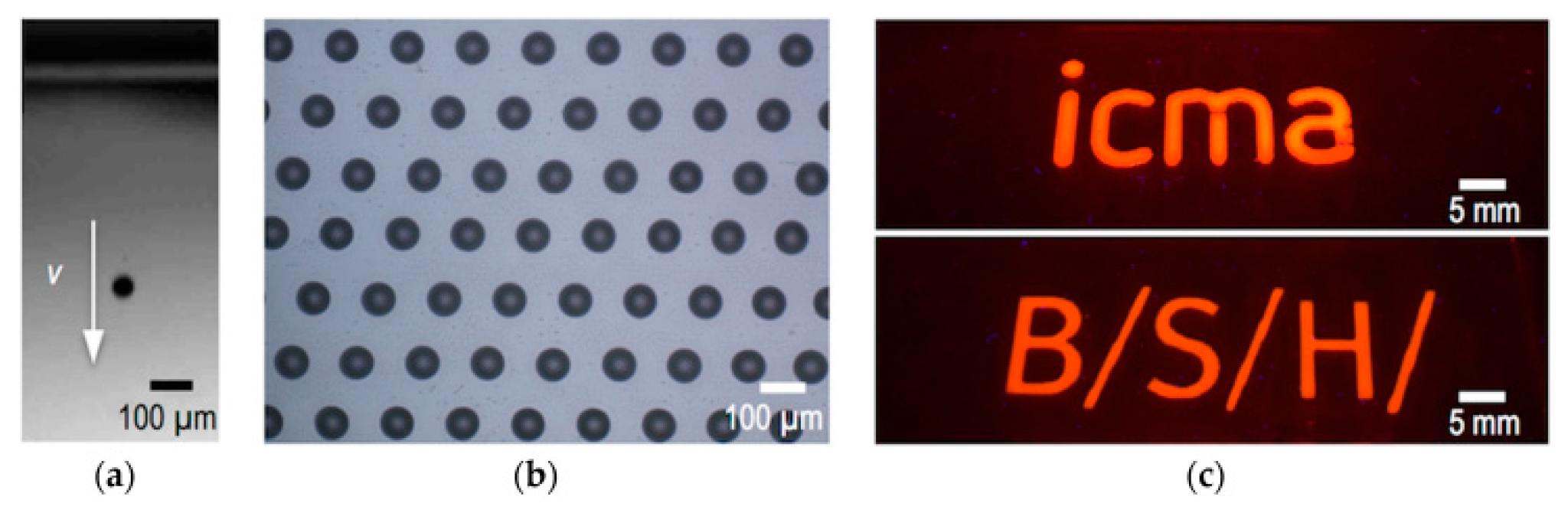

- J. Alamán, R. Alicante, J. I. Peña, and C. Sánchez-Somolinos, “Inkjet Printing of Functional Materials for Optical and Photonic Applications,” in Materials, 2016, 9, 910. [CrossRef]

- C. Ru, J. Luo, S. Xie, and Y. Sun, “A Review of Non-Contact Micro- and Nano-Printing Technologies,” in Journal of Micromechanics and Microengineering, 2014, 24, 053001. [CrossRef]

- E. B. Secor, “Principles of Aerosol Jet Printing,” in IEEE Transactions on Flexible Electronics, 2018, 3, 035002.

- S. Binder, M. Glatthaar, and E. Rädlein, “Analytical Investigation of Aerosol Jet Printing,” in Aerosol Science and Technology, vol. 48, pp. 924–929, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, C. D. Frisbie, and L. F. Francis, “Optimization of Aerosol Jet Printing for High-Resolution, High-Aspect Ratio Silver Lines,” in ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, vol. 5, pp. 4856–4864, 2013.

- V. Vlnieska, E. Gilshtein, D. Kunka, J. Heier, and Y. E. Romanyuk, “Aerosol Jet Printing of 3D Pillar Arrays from Photopolymer Ink,” in Polymers, 2022, 14, 3411. [CrossRef]

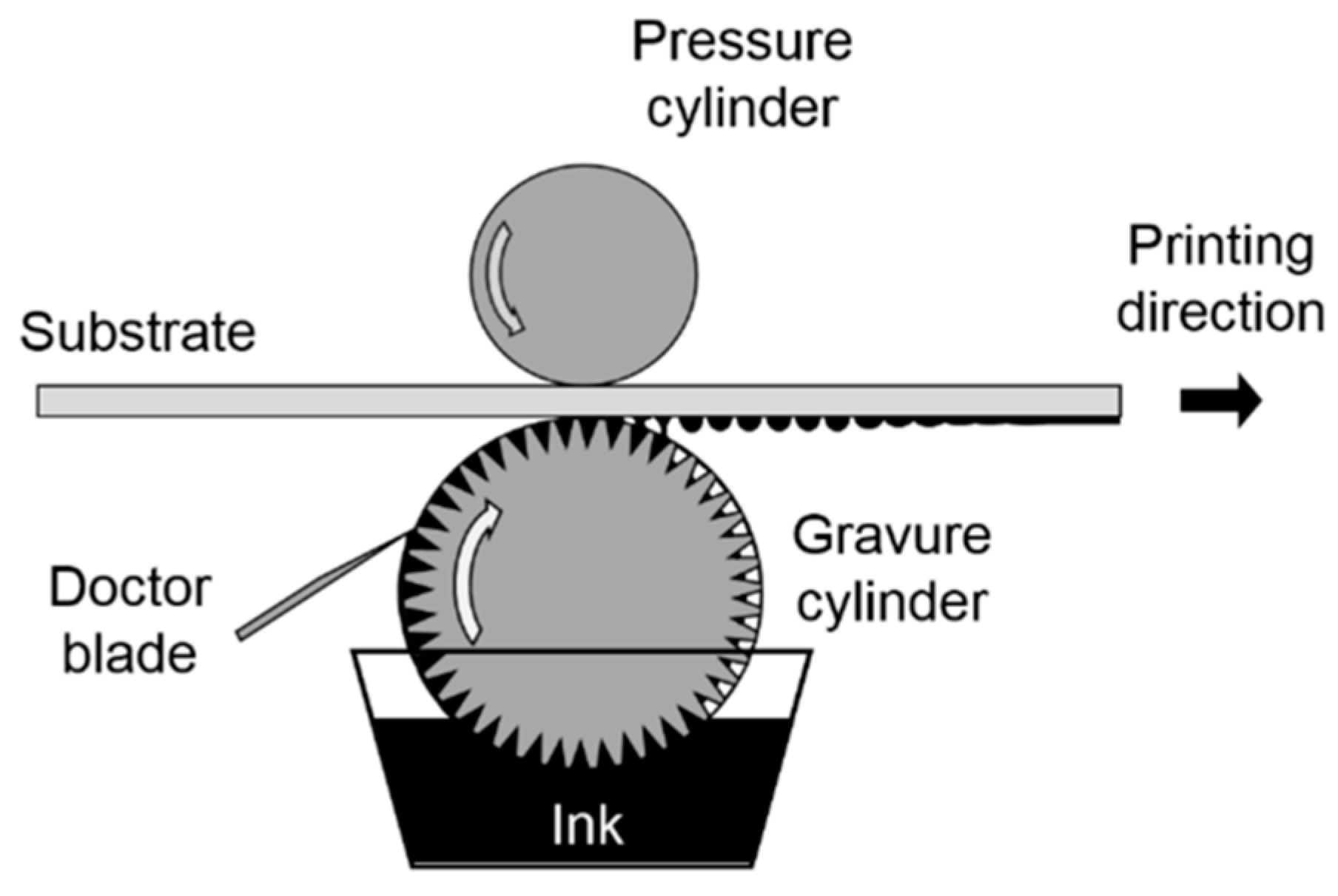

- G. Grau, J. Cen, H. Kang, R. Kitsomboonloha, W. J. Scheideler, and V. Subramanian, “Gravure-Printed Electronics: Recent Progress in Tooling Development, Understanding of Printing Physics, and Realization of Printed Devices,” in IEEE Transactions on Flexible Electronics, 2016, 1, 023002.

- S. Witomska, T. Leydecker, A. Ciesielski, and P. Samorì, “Production and Patterning of Liquid Phase–Exfoliated 2D Sheets for Applications in Optoelectronics,” in Advanced Functional Materials, 2019, 29, 1901126. [CrossRef]

- G. Sico, M. Montanino, C. T. Prontera, A. De Girolamo Del Mauro, and C. Minarini, “Gravure printing for thin film ceramics manufacturing from nanoparticles,” in Ceramics International, vol. 44, pp. 19526–19534, 2018. [CrossRef]

- G. Sico, M. Montanino, F. Loffredo, C. Borriello, and R. Miscioscia, “Gravure Printing for PVDF Thin-Film Pyroelectric Device Manufacture,” in Coatings, 2022, 12, 1020. [CrossRef]

- S. Fu, L. Yu, and J. Chen, “Advances in Gravure Printing for Printed Electronics: Materials and Manufacturing Perspectives,” in Journal of Materials Chemistry C, 2018, 6, 2615–2632.

- D. Valentine, T. A. D. Valentine, T. A. Busbee, J. W. Boley, J. R. Raney, A. Chortos, A. Kotikian, J. D. Berrigan, M. F. Durstock, and J. A. Lewis, “Hybrid 3D printing of soft electronics,” in Advanced Materials, vol. 29, pp. 1703817, 2017. [CrossRef]

- H. Kamal Alm, G. Ström, J. Schoelkopf, and P. Gane, “Ink-Lift-off during Offset Printing: A Novel Mechanism behind Ink–Paper Coating Adhesion Failure,” in Journal of Adhesion Science and Technology, 2015, 29, 370–391. [CrossRef]

- D. Maddipatla, B. B. Narakathu, and M. Atashbar, “Recent Progress in Manufacturing Techniques of Printed and Flexible Sensors: A Review,” in Biosensors, 2020, 10, 199. [CrossRef]

- G. Arrabito, Y. Aleeva, R. Pezzilli, V. Ferrara, P. G. Medaglia, B. Pignataro, and G. Prestopino, “Printing ZnO Inks: From Principles to Devices,” in Crystals, 2020, 10, 449. [CrossRef]

- Q. Liu, B. Tian, J. Liang, and W. Wu, “Recent Advances in Printed Flexible Heaters for Portable and Wearable Thermal Management,” in Materials Horizons, 2021, 8, 1634–1656. [CrossRef]

- N. Gafurov, T. H. Phung, B.-H. Ryu, I. Kim, and T.-M. Lee, “AI-Aided Printed Line Smearing Analysis of the Roll-to-Roll Screen Printing Process for Printed Electronics,” Int. J. of Precis. Eng. and Manuf.-Green Tech., 2023, 10, 339–352. [CrossRef]

- F. Marra, S. Minutillo, A. Tamburrano, and M. S. Sarto, “Production and Characterization of Graphene Nanoplatelet-Based Ink for Smart Textile Strain Sensors via Screen Printing Technique,” Materials & Design, vol. 198, p. 109306, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Jaafar, S. Schoinas, and P. Passeraub, “Pad-Printing as a Fabrication Process for Flexible and Compact Multilayer Circuits,” Sensors, 2021, 21, 6802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekcin, S. Paker, and S. K. Bahadir, “UHF-RFID Enabled Wearable Flexible Printed Sensor with Antenna Performance,” AEU - International Journal of Electronics and Communications, vol. 157, p. 154410, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X. Chen, W. Su, Z. Cui, and W.-Y. Lai, “In-Depth Investigation of Inkjet-Printed Silver Electrodes over Large-Area: Ink Recipe, Flow, and Solidification,” Advanced Materials Interfaces, 2022, 9, 2102548. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Y. Du, Q. Jiang, N. Kempf, C. Wei, M. V. Bimrose, A. N. M. Tanvir, H. Xu, J. Chen, D. J. Kirsch, J. Martin, B. C. Wyatt, T. Hayashi, M. Saeidi-Javash, H. Sakaue, B. Anasori, L. Jin, M. D. McMurtrey, and Y. Zhang, “High-Throughput Printing of Combinatorial Materials from Aerosols,” Nature, 2023, 617, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. A. M, H. Moon, G. Cho, and J. Lee, “Fully Roll-to-Roll Gravure Printed Electronics: Challenges and the Way to Integrating Logic Gates,” Jpn. J. Appl. Phys., vol. 61, no. SE, p. SE0802, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Havenko, M. S. Havenko, M. Ohirko, P. Ryvak, and O. Kotmalova, “Determining the Factors That Affect the Quality of Test Prints at Flexographic Printing,” Rochester, NY, , 2020. 27 April. [CrossRef]

- Q. Lin, Y. Zhu, Y. Wang, D. Li, Y. Zhao, Y. Liu, F. Li, and W. Huang, “Flexible Quantum Dot Light-Emitting Device for Emerging Multifunctional and Smart Applications,” Advanced Materials, vol. n/a, no. n/a, p. 2210385. [CrossRef]

- Sun, D. Liu, F. Zhu, and D. Yan, “An Efficient Solid-Solution Crystalline Organic Light-Emitting Diode with Deep-Blue Emission,” Nat. Photon., 2023, 17, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang, C. Xu, X. Yu, H. Zhang, and M. Han, “Multilayer Flexible Electronics: Manufacturing Approaches and Applications,” Materials Today Physics, vol. 23, p. 100647, 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. -H. Chen, H. Gliemann, and C. Wöll, “Layer-by-Layer Assembly of Metal-Organic Framework Thin Films: Fabrication and Advanced Applications,” Chemical Physics Reviews, 2023, 4, 011305. [CrossRef]

- K. Guo, Z. Tang, X. Chou, S. Pan, C. Wan, T. Xue, L. Ding, X. Wang, J. Huang, F. Zhang, and B. Wei, “Printable Organic Light-Emitting Diodes for next-Generation Visible Light Communications: A Review,” APN, 2023, 2, 044001. [CrossRef]

- D. Nayak and R. B. Choudhary, “A Survey of the Structure, Fabrication, and Characterization of Advanced Organic Light Emitting Diodes,” Microelectronics Reliability, vol. 144, p. 114959, 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Bairaktaris, F. Khan, K. D. J. I. Jayawardena, D. M. Frohlich, and R. A. Sporea, “Printable and Flexible Photodetectors via Scalable Fabrication for Reading Applications,” Commun Eng, 2022, 1, 1–12. [CrossRef]

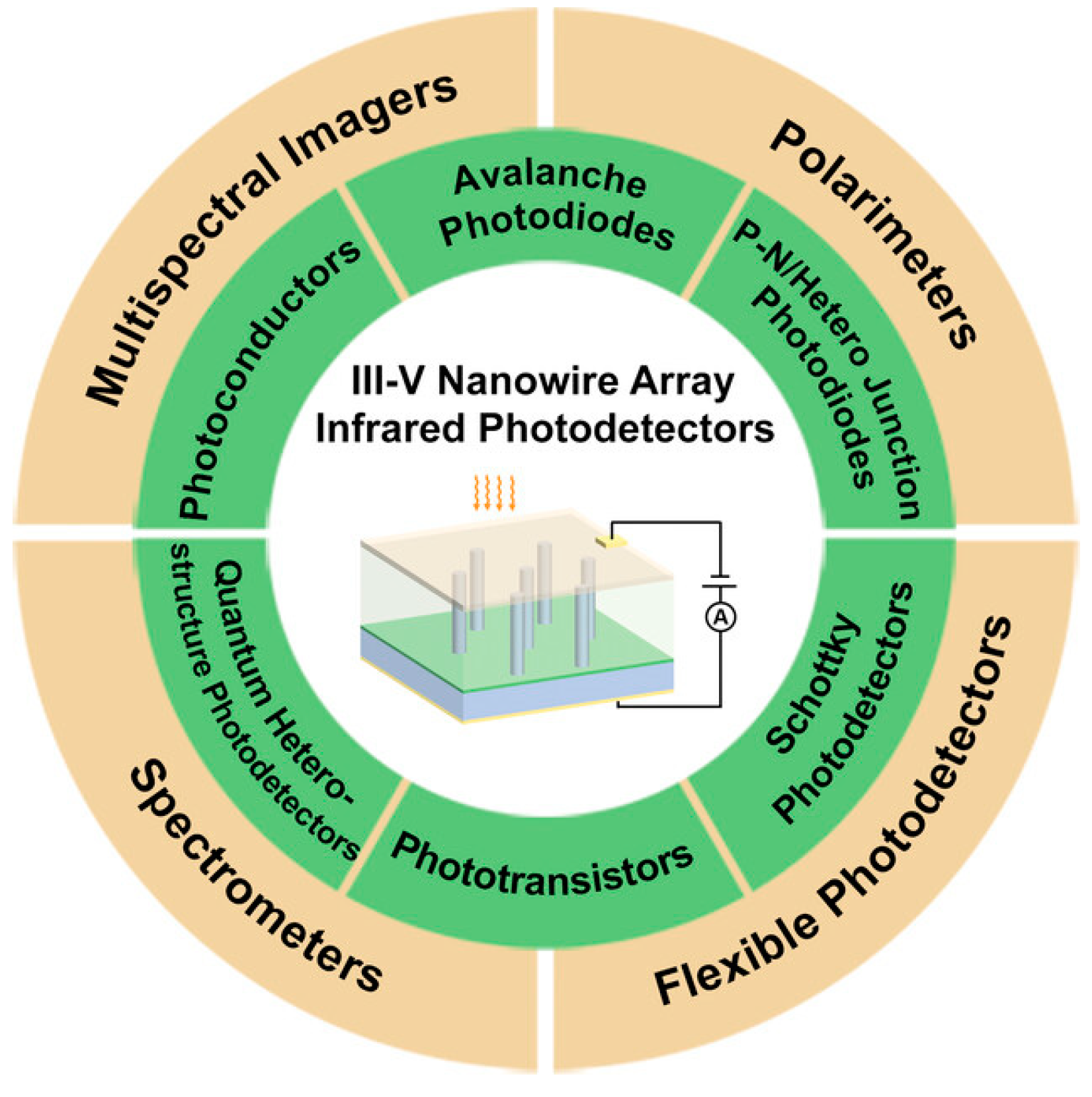

- Z. Li, Z. Z. Li, Z. He, C. Xi, F. Zhang, L. Huang, Y. Yu, H. H. Tan, C. Jagadish, and L. Fu, “Review on III–V Semiconductor Nanowire Array Infrared Photodetectors,” Advanced Materials Technologies, vol. n/a, p. 2202126. [CrossRef]

- S. N. Khonina, G. S. Voronkov, E. P. Grakhova, N. L. Kazanskiy, R. V. Kutluyarov, and M. A. Butt, “Polymer Waveguide-Based Optical Sensors—Interest in Bio, Gas, Temperature, and Mechanical Sensing Applications,” Coatings, 2023, 13, 549.

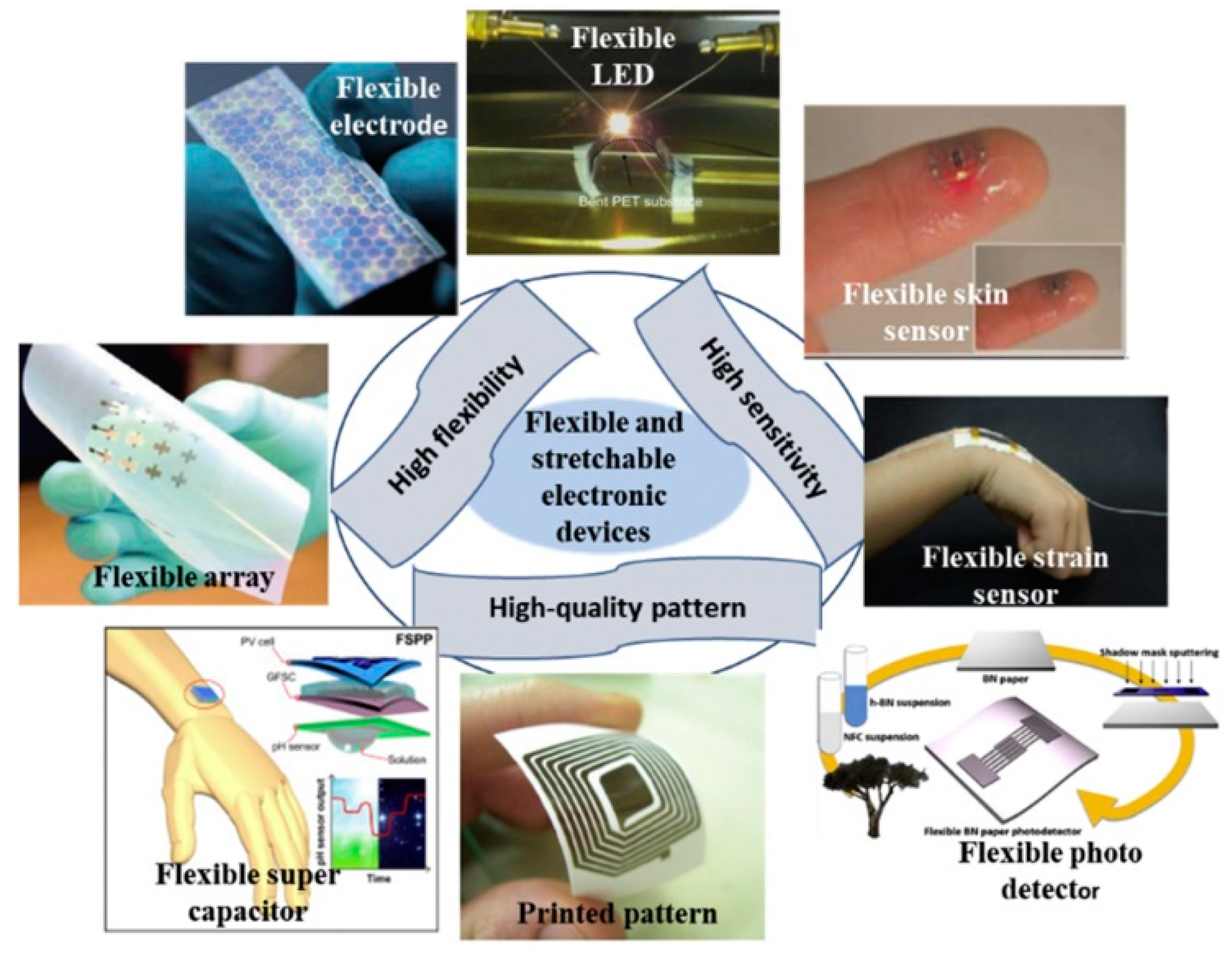

- L. Yin, J. Lv, and J. Wang, “Structural Innovations in Printed, Flexible, and Stretchable Electronics,” Advanced Materials Technologies, 2020, 5, 2000694.

- H. Lin, Z. Luo, T. Gu, L. C. Kimerling, K. Wada, A. Agarwal, and J. Hu, “Mid-Infrared Integrated Photonics on Silicon: A Perspective,” Nanophotonics, 2018, 7, 393–420. [CrossRef]

- Camposeo, L. Persano, M. Farsari, and D. Pisignano, “Additive Manufacturing: Applications and Directions in Photonics and Optoelectronics,” Advanced Optical Materials, 2019, 7, 1800419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E.-H. Lee, S. G. Lee, B. H. O, S.-G. Park, K. H. Kim, J. K. Kang, and Y. W. Choi, “Integration of Polymer-Based Optical Waveguide Arrays and Micro/Nano-Photonic Devices for Optical Printed Circuit Board (O-PCB) Application,” in Optoelectronic Integrated Circuits VII, vol. 5729, SPIE, 2005, pp. 118–129. [CrossRef]

- J. Alamán, M. López-Valdeolivas, R. Alicante, F. J. Medel, J. Silva-Treviño, J. I. Peña, and C. Sánchez-Somolinos, “Photoacid Catalyzed Organic–Inorganic Hybrid Inks for the Manufacturing of Inkjet-Printed Photonic Devices,” J. Mater. Chem. C, 2018, 6, 3882–3894. [CrossRef]

- N. C. Raut and K. Al-Shamery, “Inkjet Printing Metals on Flexible Materials for Plastic and Paper Electronics,” J. Mater. Chem. C, 2018, 6, 1618–1641. [CrossRef]

- F. Zangeneh-Nejad and R. Fleury, “Acoustic Analogues of High-Index Optical Waveguide Devices,” Sci Rep, 2018, 8, 10401. [CrossRef]

- N. Cennamo, L. Saitta, C. Tosto, F. Arcadio, L. Zeni, M. E. Fragalá, and G. Cicala, “Microstructured Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensor Based on Inkjet 3D Printing Using Photocurable Resins with Tailored Refractive Index,” Polymers, 2021, 13, 2518. [CrossRef]

- F. A. Sabah, I. A. Razak, E. A. Kabaa, M. F. Zaini, and A. F. Omar, “Characterization of Hybrid Organic/Inorganic Semiconductor Materials for Potential Light Emitting Applications,” Optical Materials, vol. 107, p. 110117, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Biria, F.-H. Chen, and I. D. Hosein, “Enhanced Wide-Angle Energy Conversion Using Structure-Tunable Waveguide Arrays as Encapsulation Materials for Silicon Solar Cells,” physica status solidi (a), 2019, 216, 1800716. [CrossRef]

- P. -I. Dietrich, M. Blaicher, I. Reuter, M. Billah, T. Hoose, A. Hofmann, C. Caer, R. Dangel, B. Offrein, U. Troppenz, M. Moehrle, W. Freude, and C. Koos, “In Situ 3D Nanoprinting of Free-Form Coupling Elements for Hybrid Photonic Integration,” Nature Photon, 2018, 12, 241–247. [CrossRef]

- Z. M. Bi and L. Wang, “Advances in 3D Data Acquisition and Processing for Industrial Applications,” Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing, 2010, 26, 403–413. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang, B. Tao, Z. Gong, W. Yu, and Z. Yin, “A Mobile Robotic 3-D Measurement Method Based on Point Clouds Alignment for Large-Scale Complex Surfaces,” IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, vol. 70, pp. 1-11, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Makarenko, D. I. Sorokin, A. Ulanov, and A. Lvovsky, “Aligning an Optical Interferometer with Beam Divergence Control and Continuous Action Space,” in Proceedings of the 5th Conference on Robot Learning, PMLR, pp. 918-927, 2022.

- S. Biria, T. S. Wilhelm, P. K. Mohseni, and I. D. Hosein, “Direct Light-Writing of Nanoparticle-Based Metallo-Dielectric Optical Waveguide Arrays Over Silicon Solar Cells for Wide-Angle Light Collecting Modules,” Advanced Optical Materials, 2019, 7, 1900661.

- J. Zhu, J. Liu, T. Xu, S. Yuan, Z. Zhang, H. Jiang, H. Gu, R. Zhou, and S. Liu, “Optical Wafer Defect Inspection at the 10 Nm Technology Node and Beyond,” Int. J. Extrem. Manuf., 2022, 4, 032001. [CrossRef]

- M. Yang, M.-W. Chon, J.-H. Kim, S.-H. Lee, J. Jo, J. Yeo, S. H. Ko, and S.-H. Choa, “Mechanical and Environmental Durability of Roll-to-Roll Printed Silver Nanoparticle Film Using a Rapid Laser Annealing Process for Flexible Electronics,” Microelectronics Reliability, 2014, 54, 2871–2880. [CrossRef]

- M. Zhuldybina, X. Ropagnol, and F. Blanchard, “Towards In-Situ Quality Control of Conductive Printable Electronics: A Review of Possible Pathways,” Flex. Print. Electron., 2021, 6, 043007. [CrossRef]

- N. Palavesam, S. Marin, D. Hemmetzberger, C. Landesberger, K. Bock, and C. Kutter, “Roll-to-Roll Processing of Film Substrates for Hybrid Integrated Flexible Electronics,” Flex. Print. Electron., 2018, 3, 014002. [CrossRef]

- K. Maize, Y. Mi, M. Cakmak, and A. Shakouri, “Real-Time Metrology for Roll-To-Roll and Advanced Inline Manufacturing: A Review,” Advanced Materials Technologies, 2023, 8, 2200173.

- L. K. Van Vugt, B. Piccione, C.-H. Cho, P. Nukala, and R. Agarwal, “One-Dimensional Polaritons with Size-Tunable and Enhanced Coupling Strengths in Semiconductor Nanowires,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A., 2011, 108, 10050–10055. [CrossRef]

- B. Peng, Ş. K. Özdemir, F. Lei, F. Monifi, M. Gianfreda, G. L. Long, S. Fan, F. Nori, C. M. Bender, and L. Yang, “Parity–Time-Symmetric Whispering-Gallery Microcavities,” Nature Phys, 2014, 10, 394–398.

- L. Chang, X. Jiang, S. Hua, C. Yang, J. Wen, L. Jiang, G. Li, G. Wang, and M. Xiao, “Parity–Time Symmetry and Variable Optical Isolation in Active–Passive-Coupled Microresonators,” Nature Photon, 2014, 8, 524–529.

- Y. Z. N. Htwe and M. Mariatti, “Printed Graphene and Hybrid Conductive Inks for Flexible, Stretchable, and Wearable Electronics: Progress, Opportunities, and Challenges,” Journal of Science: Advanced Materials and Devices, 2022, 7, 100435.

- Y. Khan, A. E. Ostfeld, C. M. Lochner, A. Pierre, and A. C. Arias, “Monitoring of Vital Signs with Flexible and Wearable Medical Devices,” Advanced Materials, 2016, 28, 4373–4395. [CrossRef]

- J. Bandodkar and J. Wang, “Non-Invasive Wearable Electrochemical Sensors: A Review,” Trends in Biotechnology, 2014, 32, 363–371. [CrossRef]

- Verboven, J. Stryckers, V. Mecnika, G. Vandevenne, M. Jose, and W. Deferme, “Printing Smart Designs of Light Emitting Devices with Maintained Textile Properties,” Materials, 2018, 11, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Fatima, A. S. Fatima, A. Haleem, S. Bahl, M. Javaid, S. K. Mahla, and S. Singh, “Exploring the Significant Applications of Internet of Things (IoT) with 3D Printing Using Advanced Materials in Medical Field,” Materials Today: Proceedings, vol. 45, pp. 4844-4851, 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Barandun, L. Gonzalez-Macia, H. S. Lee, C. Dincer, and F. Güder, “Challenges and Opportunities for Printed Electrical Gas Sensors,” ACS Sens., 2022, 7, 2804–2822. [CrossRef]

- D. T. Phan, S. Mondal, L. H. Tran, V. T. M. Thien, H. V. Nguyen, C. H. Nguyen, S. Park, J. Choi, and J. Oh, “A Flexible, and Wireless LED Therapy Patch for Skin Wound Photomedicine with IoT-Connected Healthcare Application,” Flex. Print. Electron., 2021, 6, 045002.

- S. Kirchmeyer, “The OE-A Roadmap for Organic and Printed Electronics: Creating a Guidepost to Complex Interlinked Technologies, Applications and Markets,” Transl. Mater. Res., 2016, 3, 010301.

- T. Ahmadraji, L. Gonzalez-Macia, T. Ritvonen, A. Willert, S. Ylimaula, D. Donaghy, S. Tuurala, M. Suhonen, D. Smart, A. Morrin, V. Efremov, R. R. Baumann, M. Raja, A. Kemppainen, and A. J. Killard, “Biomedical Diagnostics Enabled by Integrated Organic and Printed Electronics,” Anal. Chem., 2017, 89, 7447–7454. [CrossRef]

- Nagamine, A. Nomura, Y. Ichimura, R. Izawa, S. Sasaki, H. Furusawa, and H. Matsui, “Printed Organic Transistor-Based Biosensors for Non-Invasive Sweat Analysis,” Analytical Sciences, 2020, 36, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. -Y. Ma and N. Soin, “Recent Progress in Printed Physical Sensing Electronics for Wearable Health-Monitoring Devices: A Review,” IEEE Sensors Journal, 2022, 22, 3844–3859.

- W. C. Ma and W. Y. Yeong, “3D Printing and Electronics: Future Trend in Smart Drug Delivery Devices,” Materials Today: Proceedings, vol. 70, pp. 162-167, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Beg, W. H. Almalki, A. Malik, M. Farhan, M. Aatif, Z. Rahman, N. K. Alruwaili, M. Alrobaian, M. Tarique, and M. Rahman, “3D Printing for Drug Delivery and Biomedical Applications,” Drug Discovery Today, 2020, 25, 1668–1681. [CrossRef]

- S. Razavi Bazaz, O. Rouhi, M. A. Raoufi, F. Ejeian, M. Asadnia, D. Jin, and M. Ebrahimi Warkiani, “3D Printing of Inertial Microfluidic Devices,” Sci Rep, 2020, 10, 5929. [CrossRef]

- Raza, U. Hayat, T. Rasheed, M. Bilal, and H. M. N. Iqbal, “‘Smart’ Materials-Based near-Infrared Light-Responsive Drug Delivery Systems for Cancer Treatment: A Review,” Journal of Materials Research and Technology, 2019, 8, 1497–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Yang, N. H. Yang, N. Liang, J. Wang, R. Chen, R. Tian, X. Xin, T. Zhai, and J. Hou, “Transfer-Printing a Surface-Truncated Photonic Crystal for Multifunction-Integrated Photovoltaic Window,” Nano Energy, vol. 112, p. 108472, 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. Brunetti, A. Operamolla, S. Castro-Hermosa, G. Lucarelli, V. Manca, G. M. Farinola, and T. M. Brown, “Printed Solar Cells and Energy Storage Devices on Paper Substrates,” Advanced Functional Materials, 2019, 29, 1806798. [CrossRef]

- S. Razza, S. Castro-Hermosa, A. Di Carlo, and T. M. Brown, “Research Update: Large-Area Deposition, Coating, Printing, and Processing Techniques for the Upscaling of Perovskite Solar Cell Technology,” APL Materials, 2016, 4, 091508. [CrossRef]

- M. Gaikwad, A. C. Arias, and D. A. Steingart, “Recent Progress on Printed Flexible Batteries: Mechanical Challenges, Printing Technologies, and Future Prospects,” Energy Technology, 2015, 3, 305–328.

- P. Lechêne, M. P. Lechêne, M. Cowell, A. Pierre, J. W. Evans, P. K. Wright, and A. C. Arias, “Organic Solar Cells and Fully Printed Super-Capacitors Optimized for Indoor Light Energy Harvesting,” Nano Energy, vol. 26, pp. 631-640, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Smith, D. Jevtics, B. Guilhabert, M. D. Dawson, and M. J. Strain, “Hybrid Integration of Chipscale Photonic Devices Using Accurate Transfer Printing Methods,” Appl. Phys. Rev., 2022, 9, 041317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Jakobsen, et al. “The Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec) on the James Webb Space Telescope - I. Overview of the Instrument and Its Capabilities,” A&A, vol. 661, p. A80, 2022.

- Ouellette, A. Lesage-Landry, B. Scheffel, S. Hoogland, F. P. García de Arquer, and E. H. Sargent, “Spatial Collection in Colloidal Quantum Dot Solar Cells,” Adv. Funct. Mater., 2020, 30, 1908200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Herbert, H. E. Fowler, J. M. McCracken, K. R. Schlafmann, J. A. Koch, and T. J. White, “Synthesis and Alignment of Liquid Crystalline Elastomers,” Nat. Rev. Mater., 2022, 7, 23–38. [CrossRef]

- H. Li, “34.3: Invited Paper: Printing Pixel Circuits on Light Emitting Diode Array for AMLED Displays,” SID Symp. Dig. Tech. Papers, vol. 50, no. S1, pp. 376-378, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Gulses, S. Rai, J. Padiyar, S. Crowley, A. Martin, G. Islas, R. M. Kurtz, T. Forrester, and D. Guimary, “Laser Beam Shaping with Computer-Generated Holograms for Fiducial Marking,” in Laser Beam Shaping XIX, SPIE, 2019, vol. 11107, pp. 92-98. [CrossRef]

- W. Alyami, A. Kyme, and R. Bourne, “Histological Validation of MRI: A Review of Challenges in Registration of Imaging and Whole-Mount Histopathology,” J. Magn. Reson. Imaging, 2022, 55, 11–22. [CrossRef]

- F. Li and A. K.-Y. Jen, “Interface Engineering in Solution-Processed Thin-Film Solar Cells,” Acc. Mater. Res., 2022, 3, 272–282. [CrossRef]

- Y. Sun, Y. Jiang, X. W. Sun, S. Zhang, and S. Chen, “Beyond OLED: Efficient Quantum Dot Light-Emitting Diodes for Display and Lighting Application,” Chem. Rec., 2019, 19, 1729–1752. [CrossRef]

- H. Y. Lee and S. Kim, “Nanowires for 2D Material-Based Photonic and Optoelectronic Devices,” Nanophotonics, 2022, 11, 2571–2582. [CrossRef]

- Lall, K. Goyal, K. Schulze, and C. Hill, “Print-Consistency and Process-Interaction for Inkjet-Printed Copper on Flexible Substrate,” in ASME Digital Collection, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Chakravarty, M. Teng, R. Safian, and L. Zhuang, “Hybrid Material Integration in Silicon Photonic Integrated Circuits,” J. Semicond., 2021, 42, 041303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Li, H. Xie, E. L. Lim, A. Hagfeldt, and D. Bi, “Recent Progress of Critical Interface Engineering for Highly Efficient and Stable Perovskite Solar Cells,” Adv. Energy Mater., 2022, 12, 2102730. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang et al., “Plasma-Assisted Self-Assembled Monolayers for Reducing Thermal Resistance across Graphite Films/Polymer Interfaces,” Compos. Sci. Technol., vol. 229, p. 109690, 2022.

- J. Sánchez-Bodón et al., “Bioactive Coatings on Titanium: A Review on Hydroxylation, Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAMs) and Surface Modification Strategies,” Polymers, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 165, 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Szostak et al., “In Situ and Operando Characterizations of Metal Halide Perovskite and Solar Cells: Insights from Lab-Sized Devices to Upscaling Processes,” Chem. Rev., 2023, 123, 3160–3236. [CrossRef]

- H. Liu et al., “Technical Challenges and Perspectives for the Commercialization of Solution-Processable Solar Cells,” Adv. Mater. Technol., 2021, 6, 2000960. [CrossRef]

- Z. Xu et al., “Functional Layers of Inverted Flexible Perovskite Solar Cells and Effective Technologies for Device Commercialization,” Small Struct., 2023, 4, 2200338. [CrossRef]

- J. I. Kim et al., “Strategies to Extend the Lifetime of Perovskite Downconversion Films for Display Applications,” Adv. Mater., vol. n/a, no. n/a, p. 2209784. [CrossRef]

- Q. Lu et al., “A Review on Encapsulation Technology from Organic Light Emitting Diodes to Organic and Perovskite Solar Cells,” Adv. Funct. Mater., 2021, 31, 2100151. [CrossRef]

- C. Tong, “Fundamentals and Design Guides for Printed Flexible Electronics,” in Advanced Materials for Printed Flexible Electronics, C. Tong, Ed. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–51, 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. -M. Choi et al., “Overview and Outlook on Graphene and Carbon Nanotubes in Perovskite Photovoltaics from Single-Junction to Tandem Applications,” Adv. Funct. Mater., 2022, 32, 2204594. [CrossRef]

- H. Schröder, W. H. Schröder, W. Lewoczko-Adamczyk, and D. Weber, “Enabling Photonic System Integration by Applying Glass Based Microelectronic Packaging Approaches,” in Proc. 2022, vol. 266, p. 03020. [CrossRef]

- A. Rafique et al., “Recent Advances and Challenges Toward Application of Fibers and Textiles in Integrated Photovoltaic Energy Storage Devices,” Nano-Micro Lett. , 2023, 15, 40. [CrossRef]

- F. Wen et al., “Advances in Chemical Sensing Technology for Enabling the Next-Generation Self-Sustainable Integrated Wearable System in the IoT Era,” Nano Energy, vol. 78, p. 105155, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Sutherland, H. C. Weerasinghe, and G. P. Simon, “A Review on Emerging Barrier Materials and Encapsulation Strategies for Flexible Perovskite and Organic Photovoltaics,” Adv. Energy Mater., 2021, 11, 2101383. [CrossRef]

- R. F. P. Junio et al., “Development and Applications of 3D Printing-Processed Auxetic Structures for High-Velocity Impact Protection: A Review,” Eng., 2023, 4, 903–940. [CrossRef]

- W. Zong et al., “Recent Advances and Perspectives of 3D Printed Micro-Supercapacitors: From Design to Smart Integrated Devices,” Chem. Commun., 2022, 58, 2075–2095. [CrossRef]

- C. Xin et al., “A Comprehensive Review on Additive Manufacturing of Glass: Recent Progress and Future Outlook,” Mater. Des., vol. 227, p. 111736, 2023. [CrossRef]

| Materials | Advantages | Limitations | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymers | i) Easy to process ii) Lightweight and low cost iii) Flexible |

i) Low conductivity ii) Moderate thermal stability |

[58,59] |

| Inorganic | i) Excellent optical properties ii) High refractive index, |

i) Limited flexibility ii) Expensive |

[60] |

| Hybrid | i) Mix of inorganic and organic properties | i) Optimization challenges ii) Complex fabrication |

[61] |

| Nano-materials | i) Enhanced functionality ii) Tunable properties |

i) Limited scalability ii) High cost |

[62] |

| Printing Technique | Scalability | Advantages | Applications | Printing Speed | Limitations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inkjet Printing | Scalable | Compatible with various materials, control of droplet size with precision. | Various | Moderate to High | Clogging, ink formulation challenges, and issues with substrate compatibility | [85] |

| Aerosol Printing | Scalable | Scalable and compatible with various materials in high speed deposition requirements. | Large-area deposition | High | Challenges in achieving uniform deposition thickness and precise control of droplet size | [86] |

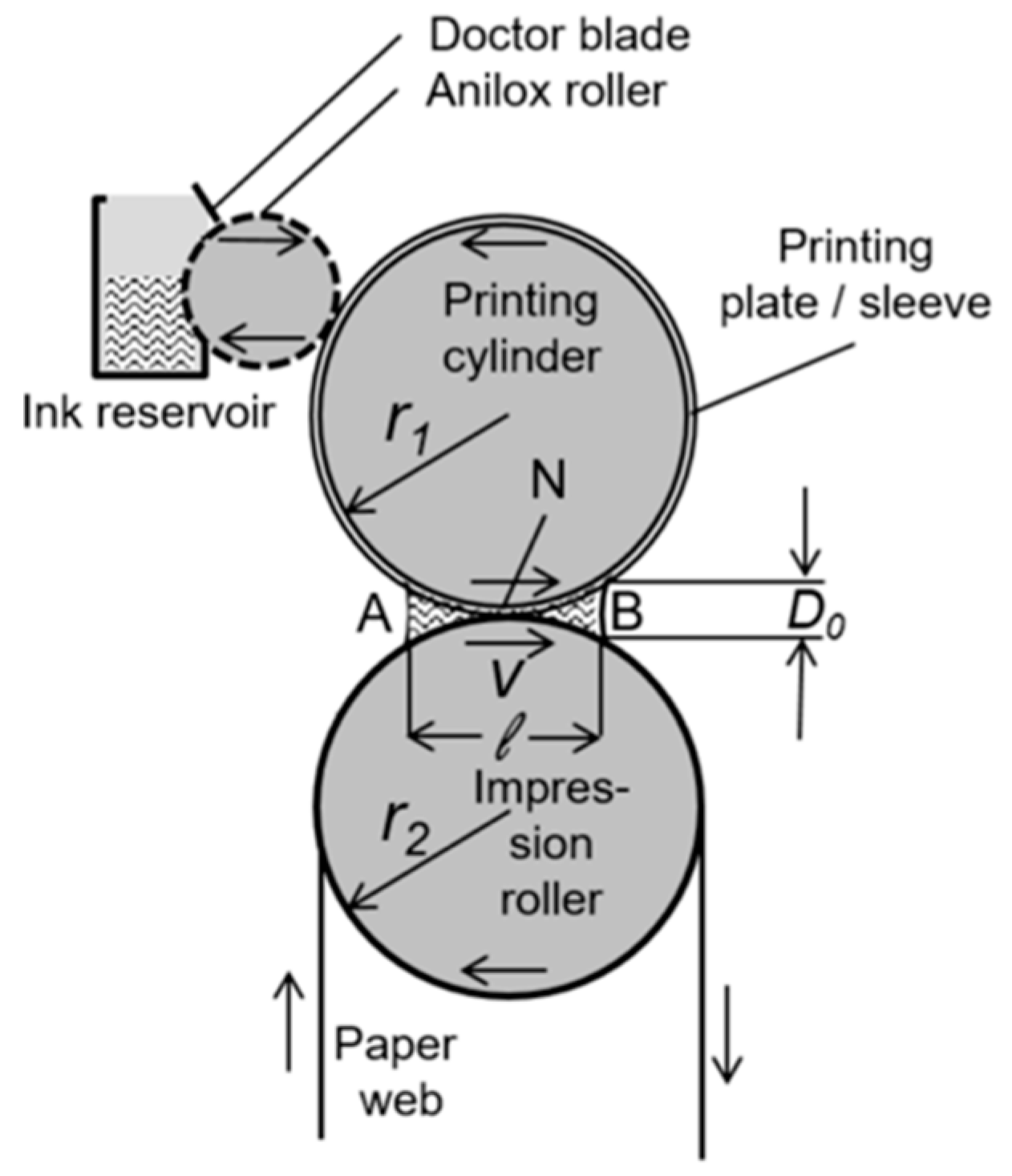

| Gravure Printing | High | Good reproducibility and ink transfer efficiency. Precise deposition with high speed. | Mass production | High | Limited flexibility due to fixed pattern. Expensive plate fabrication mechanism | [87] |

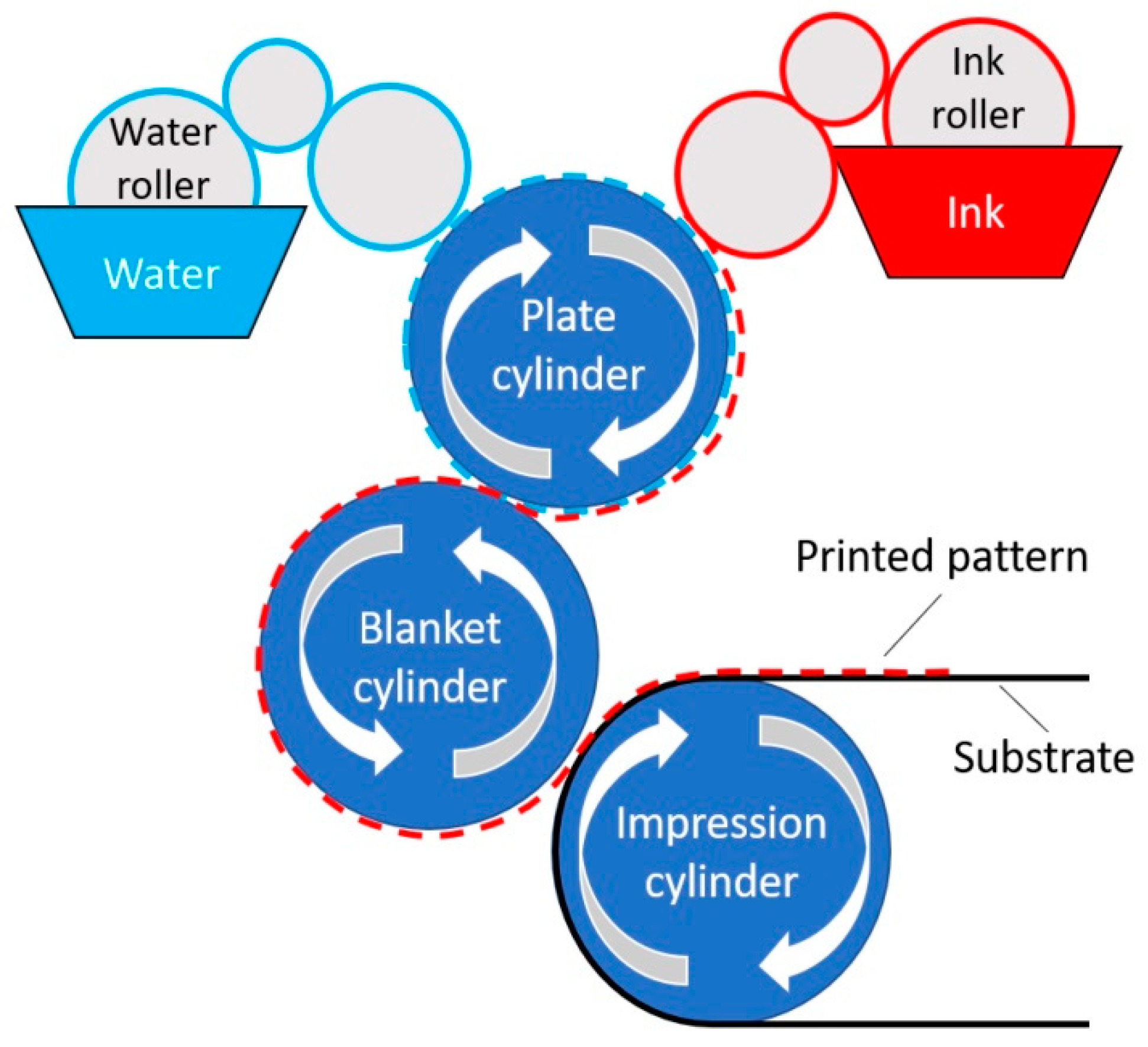

| Offset Printing | Moderate | Excellent color reproduction and applicable to a variety of substrates | Commercial printing | High | Complex setup and expensive, inability to quickly make adjustments | [77] |

| Flexographic Printing | High | High ink transfer efficiency, fast printing speeds, and appropriate for many materials and substrates | Packaging, large-area | High | Challenges in attaining high resolution, Limited ink transfer consistency on irregular surfaces | [88] |

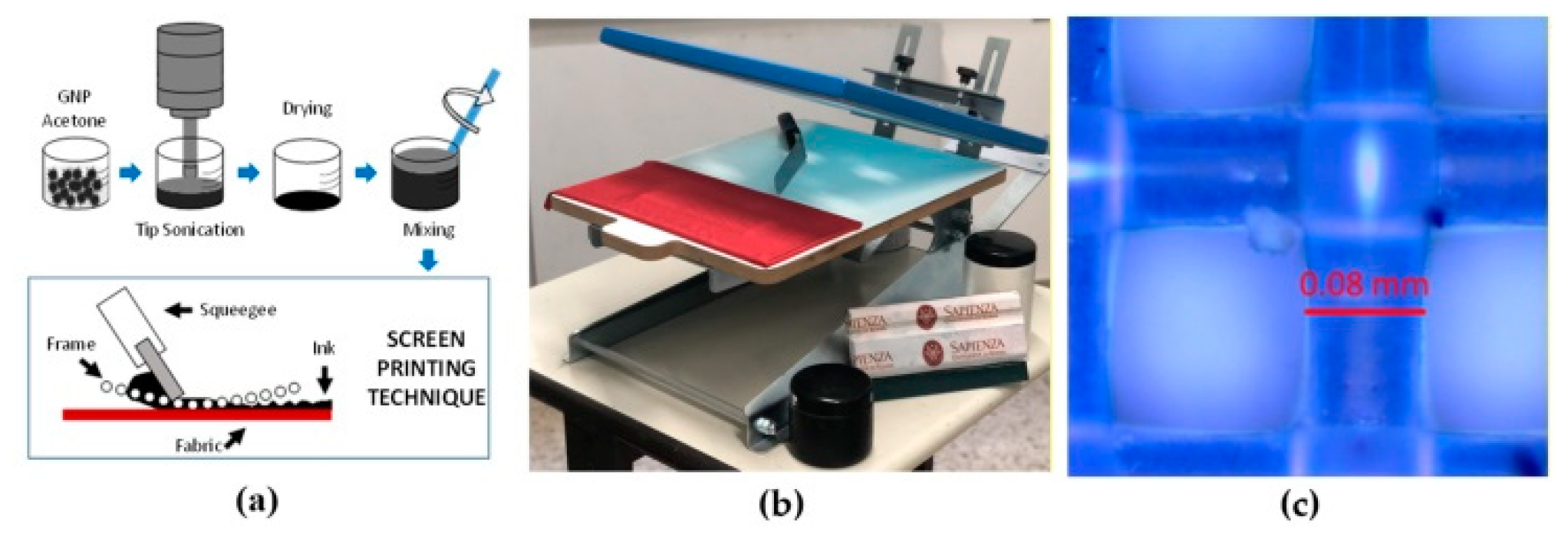

| Screen Printing | Moderate | Simple and Versatile. High throughput. Can be used for a variety of substrates. Low cost | Displays, sensors | Moderate | Limited resolution due to mesh size constraints. Restricted to mostly thick film depositions. | [81] |

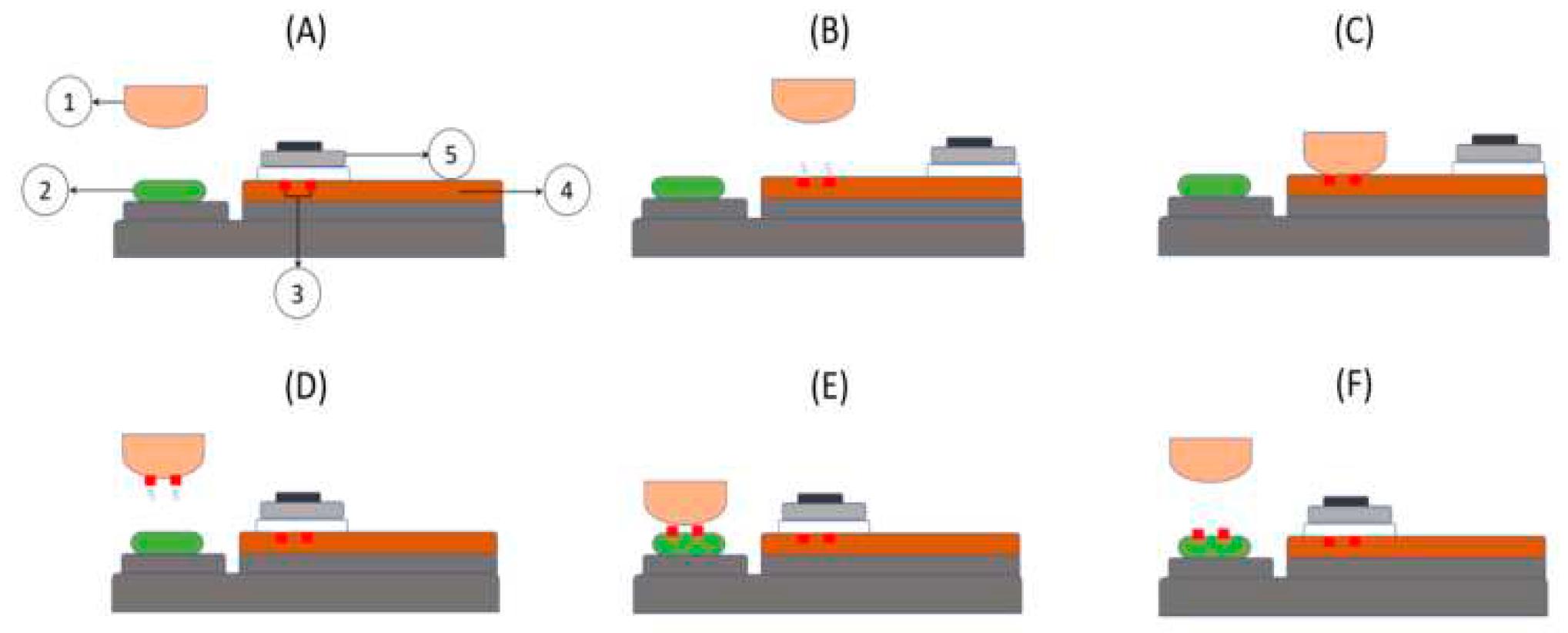

| Pad Printing | Moderate | Versatile and able to print on irregular surfaces with high printing resolution. | Three-dimensional objects | Moderate | Challenges in consistent ink transfer | [83] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).