1. Introduction

Additive manufacturing (AM) of electrical, optical and mechanical prototypes has eased the production and error elimination in recent few years. Rapid prototyping and characterization of optical components using optically transparent materials may have potential to become an advantageous economic alternative to the commercial optical components [

1]. AM is a four step process where the 3D-structure to be manufactured is designed in Computer Aided Design (CAD) software. In this particular case, the authors focus on designing of optical components e.g. light guiding structures such as waveguides (WGs) and lenses. This design is sliced to create a layered structure. Subsequently, a 3D-printing system manufactures the prototype layer by layer based on one of the following manufacturing processes and/ or their derivatives:

Stereolithography (SLA) apparatus: This process is the oldest and one of the most accurate processes used for AM of optical components. It uses a photosensitive resin or a proportionate combination of polymethyl methcrylate (PMMA) and Polyurthane material along with methacrylic acids and monoesters. The UV-Laser hardens the photosensitive resin layer by layer based on vat polymerization and the excess resin material on the formed layer is subsequently wiped by a wiper as explained in detail in [

2].

Material Jetting: This process uses droplets of photosensitive resin that is subsequently hardened or solidified using incoherent UV-sources or a coherent UV-Laser. Multi-Jet and Polyjet process are widely used examples of material jetting. We can achieve high resolution in the range of 50

for 3D-printing using material jetting process [

3]. Some of the materials e.g.

Vero clear or

Vero Ultra Clear are widely used for manufacturing of transparent objects.

Fused Filament Fabrication (FFF): This process uses polymer filaments for 3D-printing of objects. The filament material is extruded using a print head and deposited on a build platform. More precisely, a molten thermoplastic filament using a heated nozzle is extruded on the print bed. This is cost-efficient and a very fast AM process [

4,

5]. Typical filaments used for manufacturing of optical components are PMMA, Polyethylene terephthalate glycol (PETG), Acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) and its derivatives.

The materials used for manufacturing of optical components are usually derivatives of acrylic material and/ or combination of optically transparent polyurethane [

6]. In case of 3D-printing of optical components, material absorption is a crucial factor during the material choice. From previous research of the authors, the overall losses in optical components originate from material absorption and coupling losses [

7]. The losses due to material absorption are observed in the range of 2 dB/ cm [

4]. On top comes scattering loss by rough surfaces that must be minimized.

As far as the German market is considered, the revenue generated by 3D-printing of components has grown up to 3.56 billion US

$ within the last 10 years, the photonics industry has an overall revenue generation of 50 billion US

$. If the classic and 3D printed manufacturing processes are complementarily combined, this may turn out to be economically a beneficial alternative to the current manufacturing techniques [

8,

9]. However, all of these AM processes also in common show a pivotal drawback that the surfaces are not of optical quality and require post-processing. Moreover, the surface resolution and optical transparency highly depend on the layer by layer manufacturing of the 3D-printed structure. In case of FFF, the XY layer thickness of the 3D-printing systems is approximated in the range of 500

and for SLA, this value lies in the range of 250

. The surface roughness is principally caused by this limited print resolution as mentioned in [

10], but as well due to air gaps during the 3D-printing. Infill density variation and layer by layer extrusion or deposition of the material are also dominant parameters accountable for increased surface roughness. For instance, the surface roughness of the unprocessed 3D-objects manufactured using FFF process lies in the range of 50

while with SLA produced objects feature a surface roughness in the range of 15

[

2,

7]. In order to reduce scattering loss and achieve transparency, the surface roughness must be in the range of

or smaller [

11,

12,

13], i.e. below 80 nm for visible light components.

Inexpensive methods for post-processing the rough surfaces involve polishing and lacquering. In both cases, the surface curvature and features may be affected which will have impact on the device performance, in particular for refractive elements like lenses. A first step to enhance the surface quality can already be undertaken during AM when support structures are required to establish the printing process that must be later removed. In [

14], we discussed the use of water soluble materials as support structures to avoid the post-processing efforts in case of FFF 3D-printing. This method is rather well suited to achieve a surface roughness of up to 50

. However, this is by far not sufficient for an optical quality surface finish.

Some dip-coating processes have yet already been demonstrated. The typical dip-coating process involves immersing the object to be coated in the desired lacquer. This process creates a fairly thick uniform layer of lacquer on the rough surface [

15]. Some automation based dip-coating techniques developed for FFF 3D-printers are also in practice [

16]. Moreover, it is also a worthwhile approach to analyze the sheer, compression and tensile properties of the dip-coated materials [

17]. As the surface roughness of the coating layers are necessarily to be in the range of a few 10

, it is helpful to use soft matter nanomechanics for further material analysis [

18]. Indirect 3D-printing based dip-coating techniques are cutting edge technologies for the dip-coating of fibers and 3D-structures [

19].

Thin film dip coating as necessary for optical components uses a volatile solvent to create a uniform layer of coating material over the surface [

20]. This method creates small air bubbles on the coated area due to the evaporation of solvent. Other coating processes use injection of material over the surface to be coated and spinning of coating solvent over the surface as described in [

21,

22]. A further widely used option is spin coating [

23], working nicely for comparatively flat structures, e.g. metallic sheets. Moreover, microgel based dip-coating methods are more popular for coating of optical fibers, however, in case of dip-coating of optical components there is a need of index-matched oils to avoid refraction [

24]. Polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) based dip-coating of plastic optical fibers using simultaneous UV-hardening is discussed in [

25]. This process is suitable for optical fibers that are manufactured by a traditional fiber pulling setup. A multiple dip-coating based technique discussed in [

26] gives an insight of economical approach to dip-coating. Some other research on dip-coating involves use of capillary force and meniscus formation technique with angled immersion of optical component in the solvent. This meniscus recoating method, however, is highly immersion angle-dependent [

27,

28]. PMMA was also demonstrated as material for dip-coated anti-reflection coating of Vero Clear-based optical components[

29]. The layer thickness is of key importance for ARC coatings and must be adapted to the required wavelength.

In this manuscript we demonstrate a dip-coating process using the same resin as was previously used for the 3D-printed object resulting in perfect refractive index matching of coating layer and object, irrespective of the operation wavelength.

The structure of remaining article is as follows.

Section 2 discusses different conventional post-processing techniques and introduces novel dip-coating process.

Section 3 gives an overview of the results achieved using dip-coating of optical components followed by conclusion and outlook in

Section 4.

2. Post-Processing of Optical Components and Resin-Based Dip-Coating Process

For demonstration of the performance of dip-coating process, we manufactured optical WGs, as well as plano-convex lenses and Fresnel lenses by the SLA-based 3D-printer

Formlabs Form 3 using

Formlabs Clear Resin V4,Formlabs. The system offers a Z-resolution (layer thickness) of 25

and an XY resolution of 250

. It operates using a UV light source at 375

wavelength for vat polymerization and subsequently deposits the layers of hardened photosensitive resin on print bed. The membrane-based resin tank of the

Formlabs Form 3 3D-printer stored at the bottom along with the timely wiping function avoids the formation of satellite droplets during the whole 3D-printing process and after the removal of the structure from build platform. We manufactured these 3D-structures with support structures to hold the actual 3D-printed prototype during the whole printing process. An optimized version of low force SLA process adapts the effortless removal of support structure by leaving less support marks on the 3D-printed structure [

30,

31]. Subsequently, the prototypes are washed using iso-propyl alcohol to remove any resin residues from the prototype for up to 20 minutes in an ultrasonic cleaner (

FormWash from Formlabs). Next, a hardening device (

FormCure from Formlabs) equipped with a 405

UV-light hardens the sample for 15 minutes at a temperature of

C. The hardened prototypes feature a surface roughness in the range of 10

± 3

, causing severe light scattering. Initial rough polishing with emery paper of grit size 1200

removes the small marks of support structures from the 3D-objects.

For benchmarking, we first employ existing surface finish post-processing techniques, polishing and lacquering as discussed in detail in [

2]. We initially use unprocessed lens prototypes with surface roughness of 10

± 3

. These roughness values are not optimized and the authors observed no difference in lateral and axial direction of surface roughness. For polishing, we use a grit size 2500

emery polishing paper, for lacquering we employ a spray coating technique. For the latter, a refractive index-compensated oil may be necessary to avoid refraction. In both cases, the remaining roughness is in the range of

- 3

(arithmetic average), yet still insufficient for optical components. We remark that several polishing rounds with progressively finer grits would yield optical quality surface finish but this is quite time-intensive and may not be very homogeneous particularly for curved or uneven surfaces. For demonstrating the dip-coating process, we 3D-printed 3

and 6

long circular WGs, with diameters 500

and 1

as well as rectangular WGs with cross section of 500

× 500

and 1

× 1

and similar lengths as above, and plano-convex lenses and Fresnel lenses with focal length of 3

and 2

respectively, both with a diameter of

. Moreover, the Fresnel lens has in total of 15 annular rings. The length of each annular cross section is

. The implemented 3D-printing process has a minimum feature size of 250

, therefore the authors initially manufactured and characterized only the multimodal WG structures.

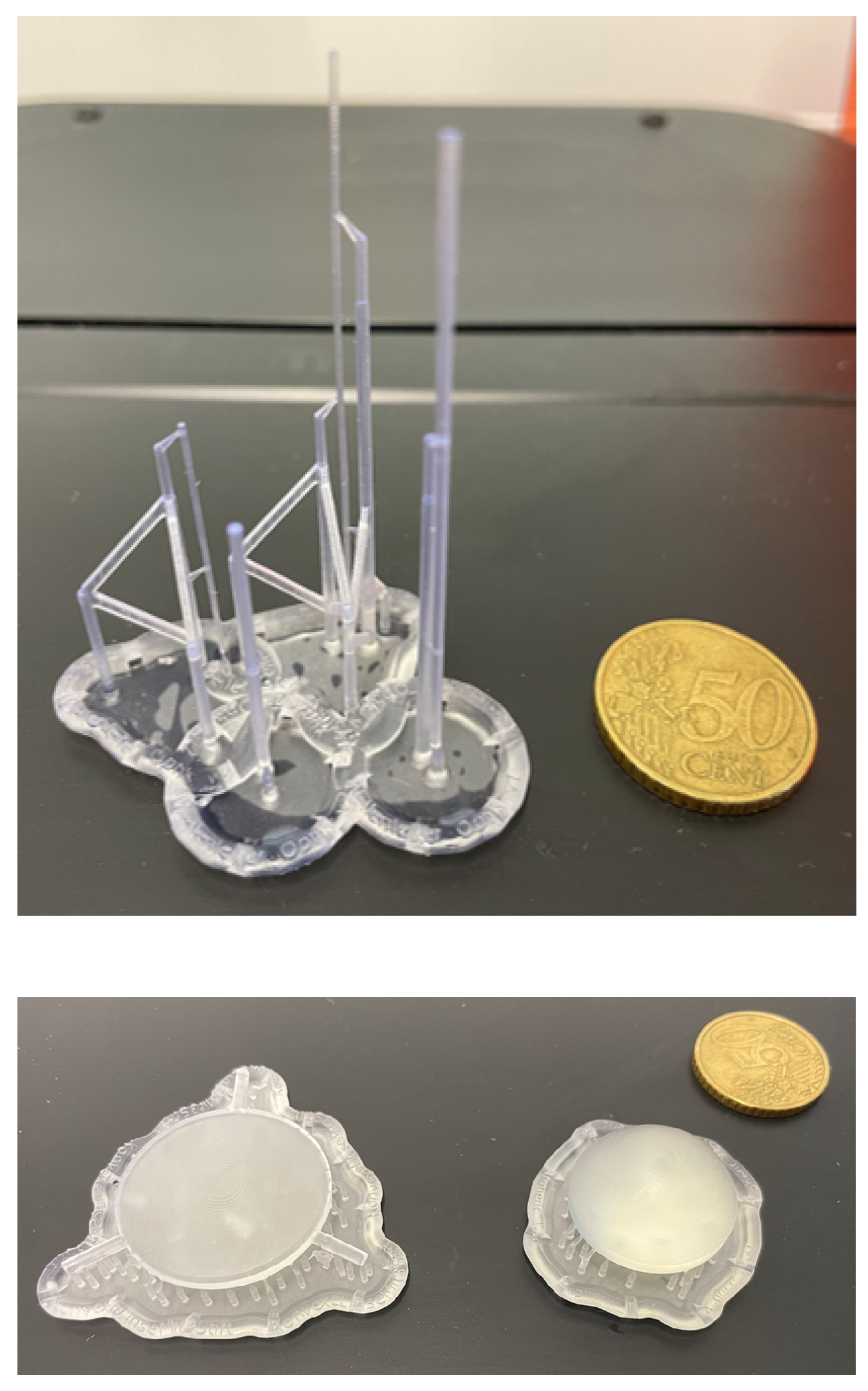

Figure 1 depicts the manufactured optical components using

Formlabs Form 3.

We then used the same Formlabs Clear resin V4 as the agent for dip-coating. This features the advantage that the same material is used for AM and dip-coating, resulting in perfect refractive index matching and thermal parameters. At room temperature, the photosensitive resin features a viscosity similar to honey. For lowering the viscosity and achieving thinner and more homogeneous coating films, the resin is heated under a fume hood to remove toxic gases using a magnetic stirrer-based stove to temperatures of up to C where the viscosity is similar to that of water. We then immerse the 3D-printed optical components in the liquefied resin for 10 seconds. We also verify timely that the temperature of the heated photosensitive resin remains constant throughout the dip-coating process. Subsequently, the dip-coated optical components prototypes are hardened using Formlabs Form Cure for 20 minutes without heating using suitable prototype holders so that the optically active surfaces of the coated prototypes remain untouched. In case of dip-coating of Fresnel lenses, only the flat surface of the lens is dip-coated initially and the surface with the annular rings remains intact. In Step 2, we then immersed the surface with annular rings only for a fraction of seconds, and then the lens is convulsed until the excess satellite droplets from the surface come off. This method confirms that the annular rings of the Fresnel lens are not coated in such a way that the lens properties change dynamically.

An alternative and simple approach to the heating of Formlabs Clear resin V4 is by placing the beaker holding resin solvent in hot water (temperature initially up to C). The convection effect causes the resin to heat up unifromly to a temperature of C yielding a viscosity similar to maple syrup. We investigated this approach for further optimization with increased water temperatures of up to C and a viscosity similar to that of water is achieved for a short duration of five minutes.

Based on the results of dip-coating using Formlabs Clear Resin V4, the authors experimented the dip-coating process on some thermoplastics with nearly equal refractive indices e.g. cyclic olefin copolymer (TOPAS) and Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS) and achieved a consistent coating layer thickness in the range of 25 . The future scope of this research involves testing the same process on a wide variety of materials, e.g. Ormocore, SU-8 etc.

3. Measurements and Results

After manufacturing of the WGs and lens prototypes and subsequent photosensitive resin-based dip-coating, we measure the surface roughness of the prototypes. We used a

Keyence VHX7000 microscope with X500-X5000 objective for the measurement of surface roughness of uncoated samples. This microscope has a minimum measurement resolution of 100

. The roughness computation is carried out using the depth-of-field recording method and subsequent 3D reconstruction of the surface yielding the surface roughness as an arithmetic average (

), that is, the deviation of surface roughness from mean height. We measured the surface roughness of the prototypes post-processed using lacquering and dip-coating using

Keyence VHX7000 microscope. For the dip-coated prototypes where the surface roughness is significantly lower than 100

, we used the surface profiler device

DEKTAK 6M from

Bruker Corporation. This profiler is best suited for surface coating measurements and has a height resolution of the order of 1

. The surface roughness of the dip-coated prototypes in the range of the system’s resolution, i.e. ∼ 5 nm. However, we observed a superimposed curvature on the order of 10/m, and some defects with a height of

-

on the surface. These minor negligible defects may be the reaction of hardening process after dip-coating.

Table 1 compares the surface roughness achieved after different post-processing techniques, e.g. polishing and lacquering.

The results tabulated in

Table 1 only represent those achieved by individual post-processing techniques and are tabulated only for comparison of state-of-the-art procedures with the new dip-coating process. We also measured the approximate thickness of the dip-coating layer. For this we used rectangular WG structures of cross section 1

× 1

and 500

× 500

followed by the dip-coating.

The cross section of dip coated WGs is observed similar to the previous measurements, using the

Keyence VHX-7000 microscope equipped with X500-X5000 objective. After repeating the observation and measurements at corners of the multiple WG prototypes axially and laterally, we validated the results to approximate the thickness of the dip-coating layer in the range of 21

± 3

. In order to ascertain that the dip coating process does not cause additional losses, the optical attenuation is verified using the cut-back technique based on [

32] and a 1550 nm laser

(Thorlabs MCLS1) beam. The laser beam of beam diameter 1

adjusted using a commercial lens of focal length 4

is passed initially through free space as a reference measurement. After that, the laser beam is passed again through both the rectangular and circular WGs mounted on suitable opto-mechanical holder. Special holders are used to fix the WGs and an iris is used to avoid the direct coupling of laser beam into the power meter. At the receiver side, we used an optical power meter

(Thorlabs PM320E with Thorlabs S122C sensor head) covering wavelengths from 700

- 1800

.

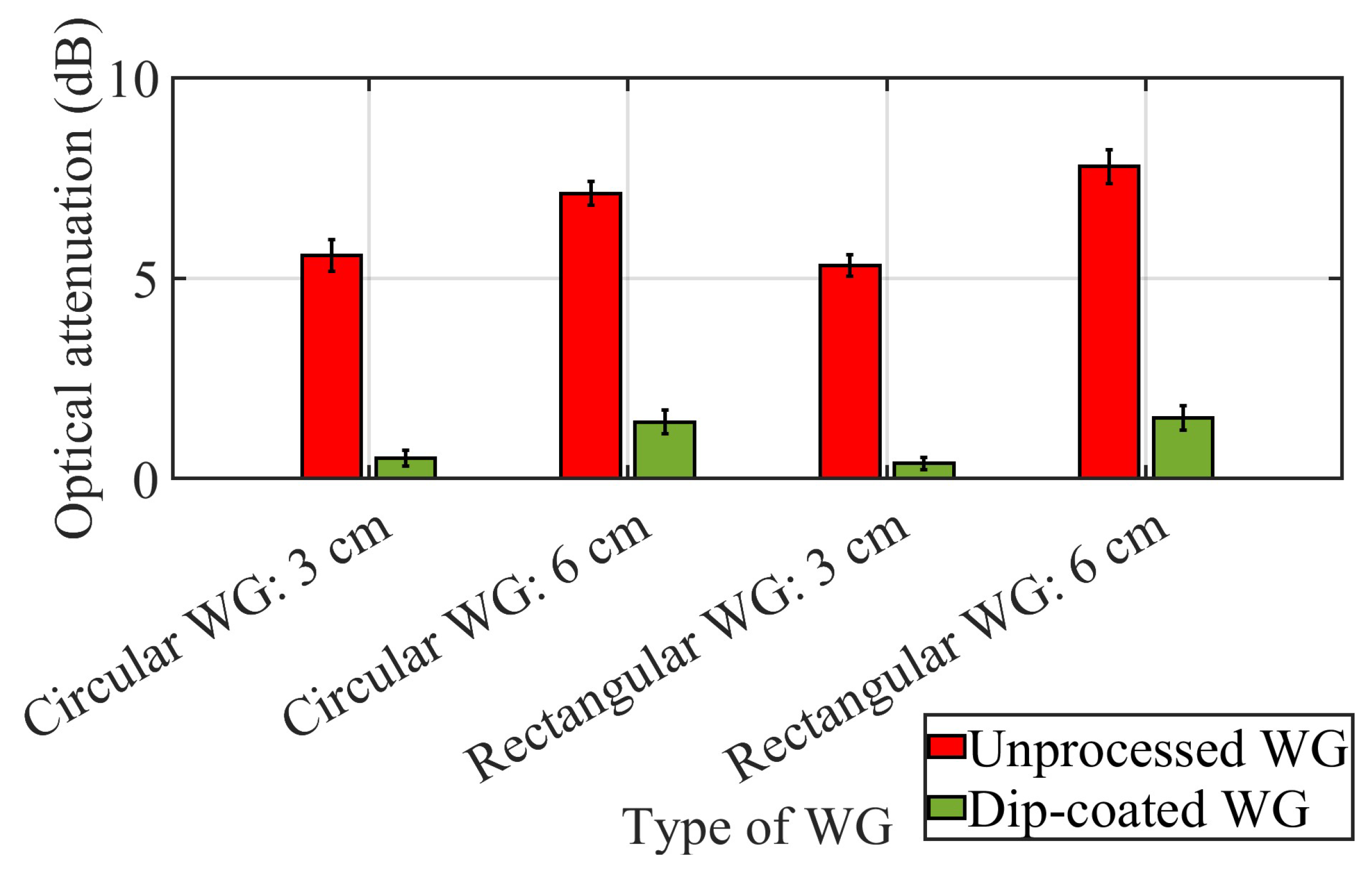

Figure 2 shows the attenuation of WG obtained for different rectangular and circular WGs before and after dip coating along with the SD. As compared to our previous results from

Section 1, the waveguiding losses are in the range of 1 dB-1.5 dB per cm of the WG. Comparing before and after dip coating, the losses are reduced by more than 4 dB in all cases. Moreover, rectangular WGs seem to feature slightly lower losses than circular WGs. Distribution of dip-coated resin material over rectangular WGs as compared to circular WGs can be related to the dipping angle and position of the WGs inside the resin material.

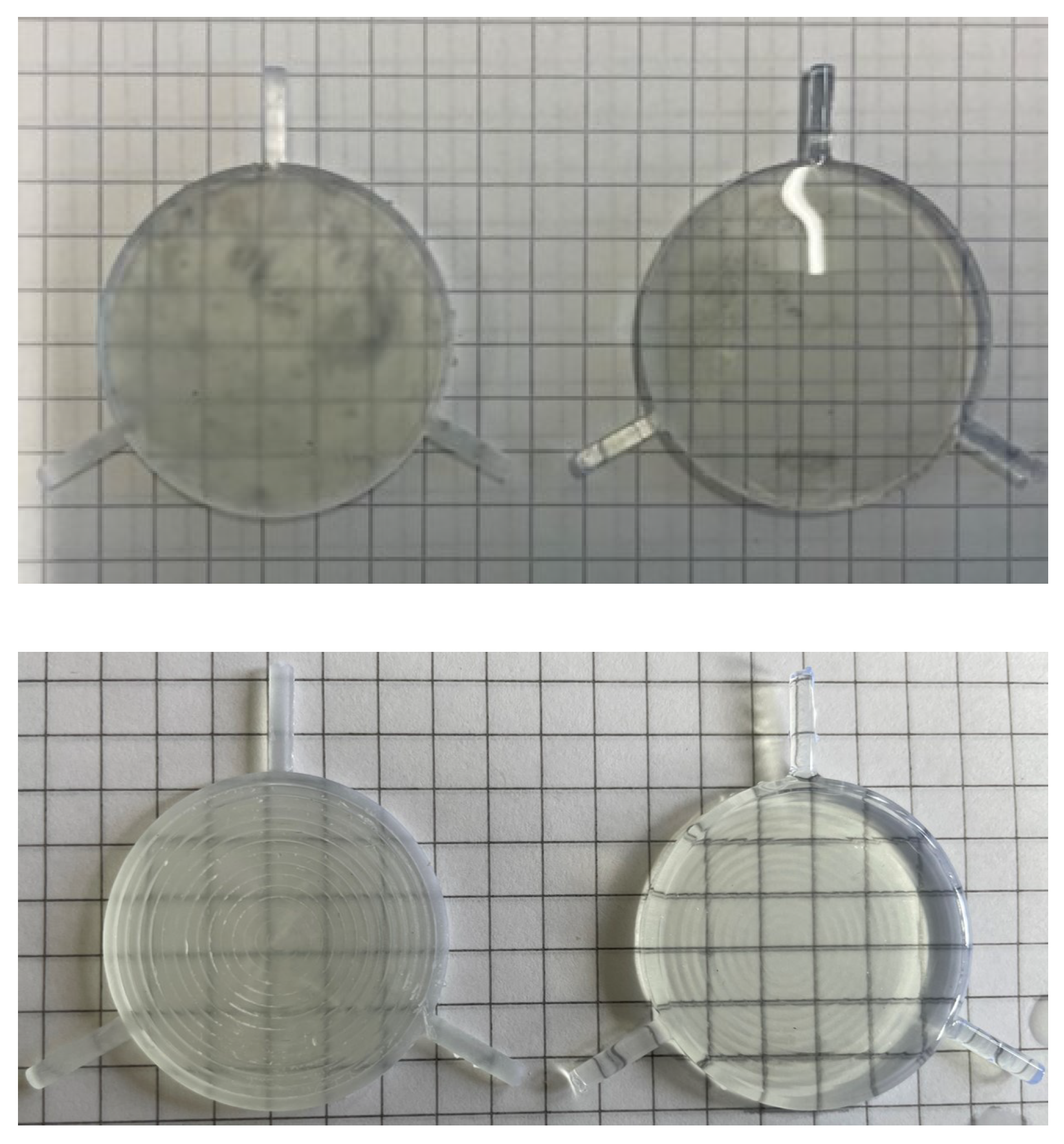

We also dip-coated plano-convex lenses as well as Fresnel lenses with

Formlabs Clear Resin V4.

Figure 3 shows the difference between unprocessed lens prototypes and dip-coated lens prototypes. The strongly improved transparency is apparent. The dip-coated lens further does not show any physical colors as they would appear due to Fabry-Pérot interference if the refractive index of the coating layer was not identical to the refractive index of the lens.

Last but not least, we characterize the focal length of the manufactured and dip-coated lenses. As previously implemented for characterization, we use a wavelength of 1550 derived from the Thorlabs MCLS1 laser source. We measure the power on the optical axis by varying the distance between the plano-convex lens and sensor head in the steps of 1 each using a Newport MM4006 automated motion controller equipped with Newport CMA25CCCL motors connected to XYZ-stage. Corresponding optical power is measured using Thorlabs PM320E with Thorlabs S122C sensor head and the optical attenuation is calculated for both unprocessed and dip-coated plano-convex lens prototypes. The focal length of the dip-coated plano-convex lens is ± based on the lowest optical attenuation achieved. We repeated similar experiment for the Fresnel lens and the focal length of the Fresnel lens is approximated at ± , very close to the design focal length of 2 . We have analyzed multiple unprocessed and dip-coated lens prototypes to approximate the typical error characteristics. The focal lengths of the dip-coated lens prototypes lie in the range of the manufacturing tolerances. This also confirms that the dip-coating process exhibits minimal substantial effect on overall functioning of the lens prototypes.

4. Conclusion and Outlook

We have demonstrated post-processing of additively manufactured optical components with a dip-coating process using the same resin as previously used for AM. The surface roughness caused by the printing process in the range of 10 ± 3 was reduced to the 5 level using dip-coating, enabling shiny, optically smooth surfaces. As the same resin is used for manufacturing and coating, there are no Fabry-Pérot effects visible proofing close to perfect refractive index matching. The inexpensive dip-coating process only requires heating of the resin (Formlabs Clear Resin V4) to C where the viscosity becomes similar to that of water providing the thickness of coated layer of 21 ± 3 . This ensures that the resin distributes uniformly over the surface of 3D-printed objects proven by comparing the design focal length with a measurement of a dip-coated lens. The difference between the two was only 3.3% of the order of the measurement- and 3D-printing accuracy. The results and observations allow to deduce that the dip-coating process is a feasible and economical approach of post-processing of 3D-printed optical components providing promising surface roughness in the nanometer-range with optical quality. The authors carried out post-processing of optical components manufactured primarily using photosensitive resin material and some thermoplastics e.g. ABS, Cyclic-olefin-copolymer (TOPAS). The future scope of the process optimization aims for further investigation and applicability analysis of the dip-coating process for the wide range of thermoplastics and UV-curable photosensitive resins.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.; methodology, A.S.; measurements, A.S. and S.P; validation, A.S.; writing, A.S., review and editing, S.P. and O.S.; supervision, S.P. and O.S.; project administration, A.S., S.P. and O.S.; funding acquisition, S.P. and O.S.

Funding

This research was funded by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German research foundation) grant number 502254396.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to Tobias Christophliemke for his inputs towards the new approaches and for making all the test environments available in the laboratory.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- G. Berglund, A. Wisniowiecki, J. Gawedzinski, B. Applegate, T. S. Tkaczyk; "Additive manufacturing for the development of optical/photonic systems and components," Optica 9, 623-638, 2022; [CrossRef]

- A. Shrotri, M. Beyer, O. Stb̎be, "Manufacturing and analyzing of cost-efficient fresnel lenses using stereolithography," Proc. SPIE 11349, 3D Printed Optics and Additive Photonic Manufacturing II, 113490N, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Elkaseer, K. Chen, J. Janhsen, O. Refle, V. Hagenmeyer, S. Scholz, "Material jetting for advanced applications: A state-of-the-art review, gaps and future directions," Additive Manufacturing, Volume 60, Part A, 103270, ISSN 2214-8604, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Beyer, A. Shrotri, and O. Stübbe, "Evaluation of stereolithography processes for the production of lens prototypes," in Production Engineering and Management, pp. 227-239,2019.

- J. Zigon, M. Kariz, M. Pavlic, "Surface Finishing of 3D-Printed Polymers with Selected Coatings," MDPI Polymers, Nov 26;12(12):2797, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Heinrich, "3D Printing of Optical Components," Springer Series in Optical Sciences, ISBN978-3-030-58959-2, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Shrotri, A. K. Mukherjee, S. Lohöfener, A. Springer, O. Stübbe and S. Preu, "Additive manufacturing and characterization of hollow core metal and topas waveguides for Terahertz sensor systems," 2023 48th International Conference on Infrared, Millimeter, and Terahertz Waves (IRMMW-THz), Montreal, QC, Canada, 2023, pp. 1-2. [CrossRef]

- https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/289933/umfrage/umsatz-der-deutschen-photonik-industrie/.

- https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/1078952/umfrage/umsatz-mit-3d-druck-weltweit/.

- A. P. Golhin, R. Tonello, J. R. Frisvad et al.; "Surface roughness of as-printed polymers: a comprehensive review," Int J Adv Manuf Technol 127, 987–1043, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Hari, J. Patadiya, B. Kandasubramanian, "Recent advancements in 3D printing methods of optical glass fabrication: A technical perspective," Hybrid Advances, Volume 7, 100289, ISSN 2773-207X, 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. Vaidya, O. Solgaard, "3D printed optics with nanometer scale surface roughness," Microsyst Nanoeng 4, 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Trost, "Light scattering and roughness properties of optical components for 13.5 nm", Doctoral Dissertation, Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena, 2015; https://www.db-thueringen.de/receive/dbt_mods_00027041.

- A. Shrotri, A. k. Mukherjee, O. Stübbe and S. Preu, "THz-Characterization of Additively Manufactured Spiral Shaped Waveguides," 2023 IEEE 11th Asia-Pacific Conference on Antennas and Propagation (APCAP), Guangzhou, China, 2023, pp. 1-2, . [CrossRef]

- A. K. Sarkar, D. Sarmah, S. Baruah, P. Datta, "An Optimized Dip Coating Approach for Metallic, Dielectric, and Semiconducting Nanomaterial-Based Optical Thin Film Fabricatio," MDPI Coatings, 13, 1391, 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. Rauh, O. Bienek, I. D. Sharp, M. Stutzmann; "Conversion of a 3D printer for versatile automation of dip coating processes," Rev. Sci. Instrum., 94 (8): 083901, 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. S. Bhamra, B. J. Tighe; "Mechanical properties of contact lenses: The contribution of measurement techniques and clinical feedback to 50 years of materials development," Contact Lens and Anterior Eye, Volume 40, Issue 2, Pages 70-81, ISSN 1367-0484, 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. Magazzù, C. Marcuello; "Investigation of Soft Matter Nanomechanics by Atomic Force Microscopy and Optical Tweezers: A Comprehensive Review," MDPI Nanomaterials, 13, 963. [CrossRef]

- G. El Chawich, J. El Hayek, V. Rouessac, et. al., "Design and Manufacturing of Si-Based Non-Oxide Cellular Ceramic Structures through Indirect 3D Printing," MDPI Materials, 15, 471 . [CrossRef]

- M. A. Butt, "Thin-Film Coating Methods: A Successful Marriage of High-Quality and Cost-Effectiveness—A Brief Exploration," MDPI Coatings, 12, 1115, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Liang, Y. Chen, B. Zhang, X. Zhang, J. Liu, C. Shen, Y. Cui, X. Guo, "Optimization of dip-coating methods for the fabrication of coated microneedles for drug delivery,", Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology, Volume 55, 101464, ISSN 1773-2247, 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. Berglund, T. Tkaczyk, "Enabling consumer-grade 3D-printed optical instruments – a case study on design and fabrication of a spectrometer system using low-cost 3D printing technologies," Opt. Continuum 1, 516-526, 2022; [CrossRef]

- Y. Shan, J. Hua, H. Mao, "3D Printing of Optical Lenses Assisted by Precision Spin Coating," Adv. Funct. Mater, 2407165, 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. Scherino, M. Giaquinto, A. Micco, A. Aliberti, E. Bobeico, V. La Ferrara, M. Ruvo, A. Ricciardi, A. Cusano, "A Time-Efficient Dip Coating Technique for the Deposition of Microgels onto the Optical Fiber Tip," MDPI Fibers, 6, 72, 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. Evertz, D. Schrein, E. Olsen, G.-A. Hoffmann, L. Overmeyer, "Dip coating of thin polymer optical fibers," Optical Fiber Technology, Volume 66, 2021, 102638, ISSN 1068-5200. [CrossRef]

- Y. Bauckhage, A. Heinrich, "Optimierung der Oberflächengüte additiv gefertigter transmittierender Optiken mittels Dip-Coating," DGaO-Proceedings, ISSN: 1614-8436 – urn:nbn:de:0287-2018-P053-6; http://www.dgao-proceedings.de.

- T. Trinh, M.-S.Smihi, L. Koev, R. Zielinski, "Dip coating process for optical elements," Hoya Optical Labs of America Inc, US20040096577A1.

- D. Chekkaramkodi, L. Jacob, M. Shebeeb C, R. Umer, H. Butt, "Review of vat photopolymerization 3D printing of photonic devices," Additive Manufacturing, Volume 86, 104189, ISSN 2214-8604, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Canning, C. Clark, M. Dayao, D. de LaMela, M. Logozzo, J. Zhao, "Anti-Reflection Coatings on 3D-Printed Components," MDPI Coatings, 11, 1519, 2011. [CrossRef]

- https://formlabs.com/.

- E. Wang, F. Yang, X. Shen, Z. Li, X. Yang, X. Zhang, W. Peng, "Investigation and Optimization of the Impact of Printing Orientation on Mechanical Properties of Resin Sample in the Low-Force Stereolithography Additive Manufacturing," MDPI Materials, 15, 6743. [CrossRef]

- Y. Vlasov, S. McNab, "Losses in single-mode silicon-on-insulator strip waveguides and bends," Opt. Express 12, 1622-1631 (2004).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).