Submitted:

06 July 2023

Posted:

07 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

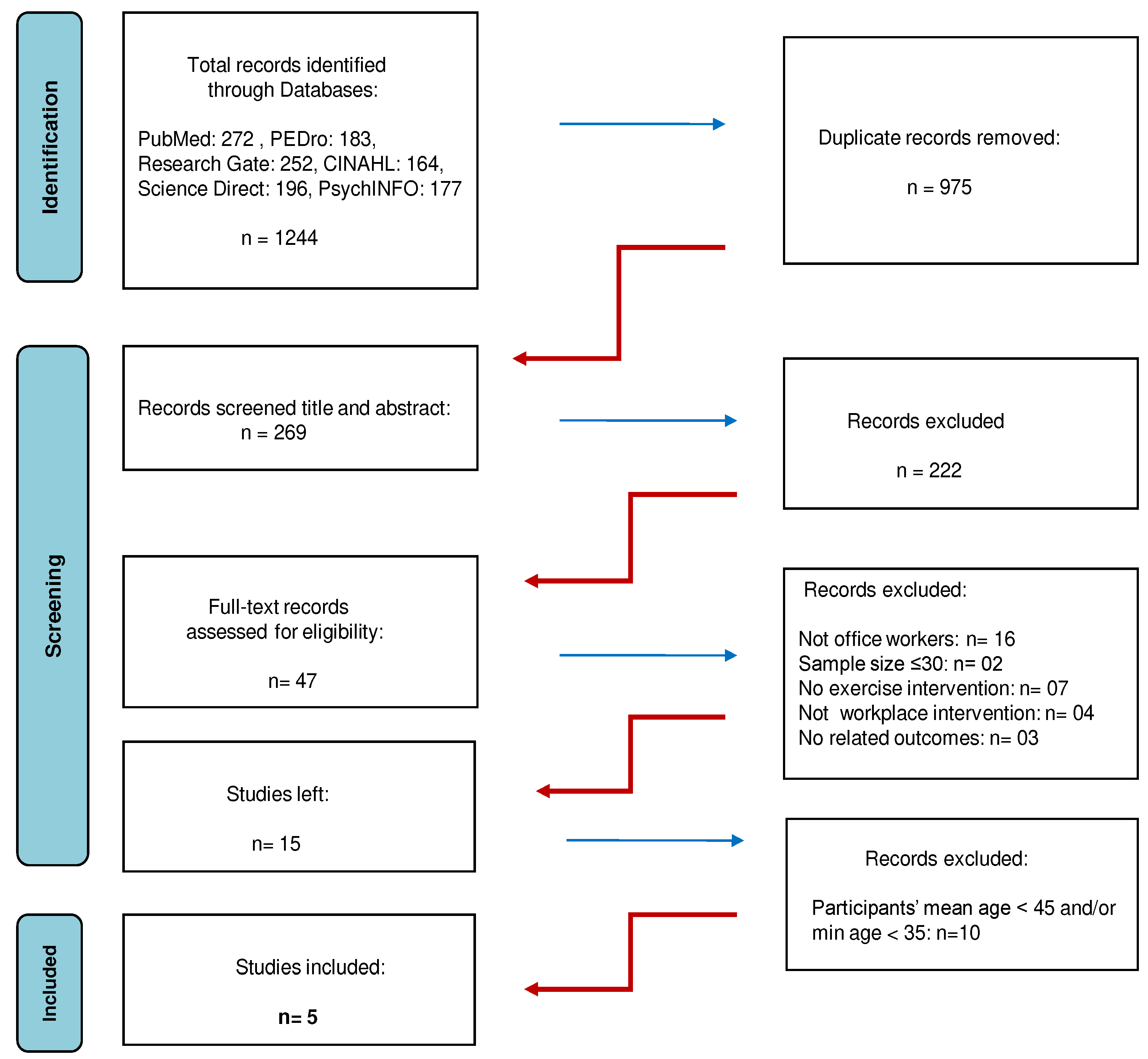

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data sources and search strategy

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria - Study selection

2.3. Quality assessment

2.4. Data extraction and synthesis

- Strong evidence: consistent findings (at least 75% of the trials report statistically significant results in the same direction) among 1 or more high quality RCTs

- Moderate evidence: consistent findings (at least 75% of the trials report statistically significant results in the same direction) among multiple (2 or more) low quality RCTs and/or 1 moderate quality RCT

- Limited evidence: 1 low-quality RCT

- Conflicting evidence: inconsistent findings among multiple RCTs

- No evidence: no RCTs

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the included studies

3.2. Participants’ demographics

3.3. Quality of the reviewed RCTs

3.4. Clinical homogeneity

3.5. Types and effects of workplace exercise intervention

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Systematic Review Registration

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khan, M.K. Technological advancements and 2020. Telecommun Syst. 2020, 73, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teychenne, M.; Costigan, S.A.; Parker, K. The association between sedentary behaviour and risk of anxiety: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2015, 15, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, G.; Hedge, A. Effect of workstation configuration on musculoskeletal discomfort, productivity, postural risks, and perceived fatigue in a sit-stand- walk intervention for computer-based work. Appl Ergon. 2021, 90, 103211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trott, M.; Driscoll, R.; Iraldo, E.; Pardhan, S. Changes and correlates of screen time in adults and children during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Med. 2022, 48, 101452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandrasekaran, B.; Ganesan, T.B. Sedentarism and chronic disease risk in COVID 19 lockdown - a scoping review. Scott Med J. 2021, 66, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockwell, S.; Trott, M.; Tully, M. et al. Changes in physical activity and sedentary behaviours from before to during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown: a systematic review. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders & Ergonomics CDC. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/workplacehealthpromotion/health-strategies/musculoskeletal-disorders/index.html. (assessed on September 5th, 2022). 5 September.

- Hoe, V.C.; Urquhart, D.M.; Kelsall, H.L.; Zamri, E.N.; Sim, M.R. Ergonomic interventions for preventing work-related musculoskeletal disorders of the upper limb and neck among office workers. CDSR. 2018, 10, CD008570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izawa, K.P.; Oka, K. Sedentary behavior and health-related quality of life among Japanese living overseas. Gerontol and Geriatr Med. 2018, 4, 2333721418808117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainsbridge, C.P.; Cooley, D.; Dawkins, S.; de Salas, K.; Tong, J.; Schmidt, M.W.; Pedersen, S.J. Taking a stand for office-based workers’ mental health: The return of the microbreak. Public Health Front. 2020, 8, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masala, D.; Mannocci, A.; Sinopoli, A.; D’Egidio, V.; Villari, P.; La Torre, G. Physical activity and its importance in the workplace. Ig Sanita Pubbl. 2017, 2, 159–169. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, J.P.; Hedge, A.; Yates, T.; Copeland, R.J.; Loosemore, M.; Hamer, M.; Bradley, G.; Dunstan, D.W. The sedentary office: An expert statement on the growing case for change towards better health and productivity. BJSM. 2015, 49(21), 1357–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitoulas, S.; Konstantis, V.; Drizi, I.; Vrouva, S.; Koumantakis, G.A.; Sakellari, V. The Effect of Physiotherapy Interventions in the Workplace through Active Microbreak Activities for Employees with Standing and Sedentary Work. Healthcare. 2022, 10, 2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundstrup, E.; Seeberg, K.G.V.; Bengtsen, E.; Andersen, L.L. A systematic review of workplace interventions to rehabilitate musculoskeletal disorders among employees with physical demanding work. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2020, 30, 30,588–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Eerd, D.; Munhall, C.; Irvin, E.; Rempel, D.; Brewer, S.; van der Beek, A.J.; Dennerlein, J.T.; Tullar, J.; Skivington, K.; Pinion, C.; Amick, B. Effectiveness of workplace interventions in the prevention of upper extremity musculoskeletal disorders and symptoms: An update of the evidence. Occup. Environ. Med. 2016, 73, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). OECD Labour Force Statistics. 2021. OECD Publishing, Paris.

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey. 2021. https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat03.htm (assessed on September 5th, 2022) 2021. https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat03. 5 September.

- Australian Bureau of Labor Force Statistics. Labour Force, Australia, Detailed Labour force status by age, social marital status and sex. 2022. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/labour/employment-and-unemployment/labour-force-australia-detailed/latest-release (assessed on September 5th, 2022). 5 September.

- Dordoni, P.; Argentero, P. When age stereotypes are employment barriers: A conceptual analysis and a literature review on older worker stereotypes. Ageing Int. 2015, 40, 393–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harasty, C.; Ostermeier, M. Population Ageing: Alternativemeasures of dependency andimplications for the future of work. ILO 2020, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Poscia, A.; Moscato, U.; La Milia, D.I.; Milovanovic, S.; Stojanovic, J.; Borghini, A.; Collamati, A.; Ricciardi, W.; Magnavita, N. Workplace health promotion for older workers: A systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016, 16, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnavita, N. Project Policy Brief 9: Workplace Health Promotion for older workers in European countries. Project Health 65+ Health Promotion and Prevention of Risk. Actions for Seniors. European research funded by EU-CHAFEA. Chief researcher for workplace action for health 2014-2017.2016.

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D. et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ.2021,372,71. [CrossRef]

- de Morton, N.A. The PEDro scale is a valid measure of the methodological quality of clinical trials: A demographic study. Austr J Physiother. 2009, 55, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paci, M.; Bianchini, C.; Baccini, M. Reliability of the PEDro scale: comparison between trials published in predatory and non-predatory journals. Arch Physiother. 2022, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkins, M.R.; Moseley, A.M.; Sherrington, C.; Herbert, R.D.; Maher, C.G. Growth in the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) and use of the PEDro scale. Br J Sports Med. 2013, 47, 188–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, B.R.; Hilfiker, R.; Egger, M. PEDro's bias: Summary quality scores should not be used in meta-analysis. J. Clin. Epidem. 2013, 66, 75–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moseley, A.M.; Herbert, R.D.; Maher, C.G.; Sherrington, C.; Elkins, M.R. Reported quality of randomized controlled trials of physiotherapy interventions has improved over time. J. Clin. Epidem. 2011, 64, 594–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbert, R.; Moseley, A.; Sherrington, C. PEDro: a database of randomised controlled trials in physiotherapy. Health information management. HIMAA. 1998, 28, 186–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armijo-Olivo, S.; da Costa, B.R.; Cummings, G.G.; Ha, C.; Fuentes, J.; Saltaji, H. et al. PEDro or Cochrane to assess the quality of clinical trials? a meta-epidemiological study. PLoS One.2015,10:e0132634. [CrossRef]

- Andersen, C.H.; Andersen, L.L.; Gram, B.; Pedersen, M.P.; Mortensen, O.S.; Zebis, M.K.; Sjøgaard, G. Influence of frequency and duration of strength training for effective management of neck and shoulder pain: a randomised controlled trial. BJSM. 2012, 46, 1004–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalager, T.; Bredahl, T.G.V.; Pedersen, M.T.; Boyle, E.; Andersen, L.L.; Sjøgaard, G. Does training frequency and supervision affect compliance, performance and muscular health? A cluster randomized controlled trial. Man Ther. 2015, 20, 657–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoglund, L.; Josephson, M.; Wahlstedt, K.; Lampa, E.; Norbäck, D. Qigong training and effects on stress, neck-shoulder pain and life quality in a computerised office environment. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2011, 17, 54–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Pozo-Cruz, B.; Gusi, N.; del Pozo-Cruz, J.; Adsuar, J.C.; Hernandez-Mocholí, M.; Parraca, J.A. Clinical effects of a nine-month web-based intervention in subacute non-specific low back pain patients: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2013, 27, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaeding, T.S.; Karch, A.; Schwarz, R.; Flor, T.; Wittke, T.C.; Kück, M.; Böselt, G.; Tegtbur, U.; Stein, L. Whole-body vibration training as a workplace-based sports activity for employees with chronic low-back pain. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2017, 27, 2027–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radwan, A.; Ashton, N.; Gates, T.; Kilmer, A.; Van Fleet, M. Effect of different pillow designs on promoting sleep comfort, quality, & spinal alignment: A systematic review. Eur J Integr Med.2021;42,101269.

- Bernard, H.R. Research Methods in Anthropology. Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Altamira Press, Lanham. Sixth Edition. ISBN-13: 978-1442268883, ISBN-10: 1442268883.2006,62-89.

- Chess, L.E.; Gagnier, J.J. Applicable or non-applicable: investigations of clinical heterogeneity in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016, 16, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mac Nee, W.; Rabinovich, R.A.; Choudhury, G. Ageing and the border between health and disease. Eur Respir J. 2014, 44, 1332–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaul, E.; Barron, J. Age-Related Diseases and Clinical and Public Health Implications for the 85 Years Old and Over Population. Front Public Health. 2017, 5, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawdeng, S.; Sihawong, R.; Janwantanakul, P. Work ability in aging office workers with musculoskeletal disorders and non-communicable diseases and its associated factors: a cross-sectional study. Int J Occup Saf Ergon. 2021, 19, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.M.; Nguyen, V.H.; Kim, J.H. Physical Exercise and Health-Related Quality of Life in Office Workers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. IJERPH. 2021, 18, 3791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radwan, A.; Barnes, L.; De Resh, R.; Englund, C.; Gribanoff, S. Effects of active microbreaks on the physical and mental well-being of office workers: A systematic review. Cogent Engin. 2022, 9, 2026206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sihawong, R.; Sitthipornvorakul, E.; Paksaichol, A.; Janwantanakul, P. Predictors for chronic neck and low back pain in office workers: a 1-year prospective cohort study. J Occup Health. 2016, 58, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sihawong, R.; Janwantanakul, P.; Sitthipornvorakul, E.; Pensri, P. Exercise therapy for office workers with nonspecific neck pain: a systematic review. J Man Phys Ther. 2011, 34, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tersa-Miralles, C.; Bravo, C.; Bellon, F.; Pastells-Peiró, R.; Rubinat Arnaldo, E.; Rubí-Carnacea, F. Effectiveness of workplace exercise interventions in the treatment of musculoskeletal disorders in office workers: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2022, 12, e054288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Coombes, B.K.; Sjøgaard, G.; Jun, D.; O'Leary, S.; Johnston, V. Workplace-Based Interventions for Neck Pain in Office Workers: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Phys Ther. 2018, 98, 40–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyussenbayev, A. Age Periods Of Human Life. ASSRJ. 2017, 4, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aullianingrum, P.; Hendra, H. Risk Factors of Musculoskeletal Disorders in Office Workers. The Indonesian JOSH.2022:11(Special Issue),68-77.

- Okezue, O.C.; Anamezie, T.H.; Nene, J.J.; Okwudili, J.D. Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders among Office Workers in Higher Education Institutions: A Cross-Sectional Study. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2020, 30, 715–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piranveyseh, P.; Motamedzade, M.; Osatuke, K.; Mohammadfam, I.; Moghimbeigi, A.; Soltanzadeh, A.; Mohammadi, H. Association between psychosocial, organizational and personal factors and prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders in office workers. Int J OccupSaf Ergon. 2016, 22, 267–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akrouf, Q.A.; Crawford, J.O.; Al-Shatti, A.S.; Kamel, M.I. Musculoskeletal disorders among bank office workers in Kuwait. East Mediterr Health J. 2010, 16, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besharati, A.; Daneshmandi, H.; Zareh, K.; Fakherpour, A.; Zoaktafi, M. Work-related musculoskeletal problems and associated factors among office workers. Int J Occup Saf Ergon. 2020, 26, 632–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardahan, M.; Simsek, H. Analyzing musculoskeletal system discomforts and risk factors in computer-using office workers. Pak J Med Sci. 2016, 32, 1425–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; He, L.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, S. Visual display terminal use increases the prevalence and risk of work-related musculoskeletal disorders among Chinese office workers: a cross-sectional study. J Occup Health. 2012, 54, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janwantanakul, P.; Pensri, P.; Jiamjarasrangsri, V.; Sinsongsook, T. Prevalence of self-reported musculoskeletal symptoms among office workers. Occup Med (Lond). 2008, 58, 436–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, J.Z.R.; Chen, X.; Johnston, V. Workplace-Based Exercise Intervention Improves Work Ability in Office Workers: A Cluster Randomised Controlled Trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019, 16, 2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, L.L.; Zebis, M.K. Process evaluation of workplace interventions with physical exercise to reduce musculoskeletal disorders. Int J Rheumatol.2014;2014,761363. [CrossRef]

- Gram, B.; Andersen, C.; Zebis, M.K.; Bredahl, T.; Pedersen, M.T.; Mortensen, O.S.; Jensen, R.H.; Andersen, L.L.; Sjøgaard, G. Effect of Training Supervision on Effectiveness of Strength Training for Reducing Neck/Shoulder Pain and Headache in Office Workers: Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Biomed Res Int. 2014, 2014, 693013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, C.H.; Andersen, L.L.; Zebis, M.K.; Sjøgaard, G. Effect of scapular function training on chronic pain in the neck/shoulder region: a randomized controlled trial. J Occup Rehabil. 2014, 24, 316–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahidi, B.; Curran-Everett, D.; Maluf, K.S. Psychosocial, Physical, and Neurophysiological Risk Factors for Chronic Neck Pain: A Prospective Inception Cohort Study. J Pain. 2015, 16, 1288–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grana, E.; Velonakis E.; Tziaferi S.; Sourtzi, P. Effectiveness of intervention programs to manage musculoskeletal disorders at the workplace- Scoping Review. Nurs Care & Res.2020,57,93-117.

- Marshall, A.L. Challenges and opportunities for promoting physical activity in the workplace. J Sci Med Sport/Sports Med Aust.2004,7,60-6. [CrossRef]

- Rongen, A.; Robroek, S.J.; van Ginkel, W.; Lindeboom, D.; Altink, B.; Burdorf, A. Barriers and facilitators for participation in health promotion programs among employees: a six-month follow-up study. BMC Public Health. 2014, 14, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Number | Keywords | Synonyms, Relevant Terms |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Office workers | “Office employee*” OR “Clerical worker*” OR “Desk based worker*” OR “Administrative worker*” OR “Computer user*” OR “Computer operator*” OR “Occupational group*” |

| 2 | Older | “Senior*” OR “Elder” OR “Elderly” OR “Ageing” OR “Aged”OR “Middle-aged” OR “Mature” |

| 3 | Exercise Intervention | “Exercises” OR “Program*” OR “Exercise activity*” OR “Exercise therapy” OR “Exercise method*” OR “Interventions” OR “Method*” OR “Prevent*” OR “Promote*” |

| 4 | Workplace | “Work” |

| 5 | Microbreaks | “Microbreak” OR “Work break*” OR “Short break*” OR “Micropause*” |

| 6 | Workability | “Productivity” OR “Absenteeism” OR “Presenteeism” OR “Musculoskeletal discomfort” OR “Musculoskeletal symptom*“ OR “Musculoskeletal pain” OR “Musculoskeletal complaint*” OR “Musculoskeletal injury*” OR “Musculoskeletal disease*” OR “Musculoskeletal problem*” OR “Musculoskeletal disorders” |

| 7 | Well-Being | “Work satisfaction” OR “Job satisfaction” OR “Attitude*” OR “Active ageing” OR “Life style*” |

| Final Search: 1 AND 2 AND 3 AND 4 AND 5 AND 6 AND 7 | ||

| P | Population | Office workers with minimum age 35 years old and participants’ mean age ≥ 45 |

| I | Intervention | Microbreaks that included exercise in the workplace during working hours |

| C | Comparison | No microbreaks, other type of microbreaks |

| O | Outcome | At least one of the study results refers to the effects of the exercise intervention |

| PEDro Scale / Study | Andersen et al., 2012 |

Dalager et al., 2015 |

Del Pozo-Cruz. et al., 2013 | Kaeding et al., 2017 |

Skoglund . et al., 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specification of eligibility criteria | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Random allocation to groups | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Concealed allocation | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Baseline similarity of group | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Blinding of subjects | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Blinding of therapists | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Blinding of assessors | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ○ |

| Drop out <15% | ○ | ○ | ● | ● | ● |

| Intention-to-treat analysis | ● | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ |

| Reported statistical comparisons | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Reported point and variability measures | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| PEDro Score | 5/10 | 5/10 | 6/10 | 7/10 | 5/10 |

| Modified PEDro Scale for Ergonomics Re-search (MPSER) | Andersen et al., 2012 |

Dalager et al., 2015 |

Del Pozo-Cruz et al., 2013 | Kaeding et al., 2017 |

Skoglund et al., 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adequate explanation of procedures | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Randomized allocation or randomized sequence of interventions and measurements | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Blinding of assessors | ○ | ● | ● | ● | ○ |

| Drop out <15% | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Intention-to-treat analysis | ● | ○ | ○ | ● | ○ |

| Reported statistical comparisons | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Reported point and variability measures | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| MPSER Score | 6/7 | 6/7 | 6/7 | 7/7 | 5/7 |

| Study | Type of exercise intervention | Reported outcomes | Effect of exercise intervention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Andersen et al, 2012 | strengthening intervention | Exercise intervention effectively reduced neck and shoulder pain in office workers compared with the control group. | Positive* |

| Dalager et al., 2015 | strengthening intervention | Only the training groups improved significantly their muscle strength and endurance. | Positive* |

| Del Pozo-Cruz et al., 2013 | intervention that concludes strengthening and postural reminders and stretching and exercises to improve postural stability | The exercise intervention showed clinical improvements in quality of life and selected lower back pain outcomes in the experimental group compared to the control group. | Positive* |

| Kaeding et al., 2017 | isometric intervention with vibration | There are significant effects of exercise training in the Intervention Group compared to the Control Group, regarding the primary outcome subjective disability, the pain-related disability as measured, the health-related quality of life, the health effective physical activity and the post-interventional sick leave. | Positive* |

| Skoglund et al., 2011 | active exercise with simultaneous breathing | Exercise intervention is not more effective than nointervention. | Neutral** |

| Type of exercise intervention | Study | Effect of exercise intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Strengthening intervention | a) Andersen et al., 2012 b) Dalager et al., 2015 |

Strong evidence |

| Strengthening intervention andpostural reminders and stretching and exercises to improve postural stability |

Del Pozo-Cruz et al., 2013 |

Strong evidence |

| Isometric intervention with vibration | Kaeding et al., 2017 | Strong evidence |

| Active exercise with simultaneous breathing | Skoglund et al., 2011 | Moderate evidence |

| Study | Exclusion criteria of the participants |

|---|---|

| Andersen et al., 2012 | a) hypertension (systolic Blood Pressure >160mmHg, diastolic BP >100 mmHg), b) cardiovascular diseases, c) symptomatic herniated disc or severe disorders of the cervical spine, d) postoperative conditions in the neck and shoulder region, e) history of severe trauma or other serious disease and f) pregnancy |

| Dalager et al., 2015 | a) hypertension (systolic Blood Pressure >160 mmHg, diastolic BP >100 mmHg), b) cardiovascular diseases, c) symptomatic herniated disc or severe disorders of the cervical spine, d) postoperative conditions in the neck and shoulder region, e) history of severe trauma or other serious disease and f) pregnancy |

| Del Pozo-Cruz et al., 2013 | a) diagnosed cause of backache, b) reported chronic backache, c) clinical red flags such as disc disease, d) any other major disease and e) a lack of fluency in Spanish |

| Kaeding et al., 2017 | a) thrombosis, b) surgeries in the last 6-8 weeks, c) artificial joint replacements in the last 6 months, d) coronary heart disease or arterial occlusive disease, e) insufficiently treated hypertension, f) diabetes mellitus (with advanced microangiopathies, gangrenes, diabetic feet, retinal problems), g) cardiac or brain pacemaker, h) pregnancy, i) acute inflammation of the musculoskeletal system (activated arthrosis or arthropathy), j) acute tendinopathies in body parts affected by the intervention, k) acute hernias, l) acute radicular pain or complicate back pain, m) recent fractures in body partsinvolved in the intervention, n) rheumatoid arthritis, o) epilepsy and p) intrauterine device |

| Skoglund et al., 2011 | no exclusion criteria |

| Study | PEDro and MPSER Score |

|---|---|

| Andersen et al., 2012 | PEDro: 5 /10 MPSER: 6 /7 |

| Dalager et al., 2015 | PEDro: 5 /10 MPSER: 6 /7 |

| Del Pozo-Cruz et al., 2013 | PEDro: 6 /10 MPSER: 6 /7 |

| Kaeding et al., 2017 | PEDro: 7 /10 MPSER: 7 /7 |

| Skoglund et al., 2011 | PEDro: 5 /10 MPSER: 5 /7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).