Submitted:

04 July 2023

Posted:

10 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Physical properties of chia seeds from different origins

2.3. Proximate chemical composition

2.4. Amino acid profile

2.5. Oil extraction and fatty acids’ profile

2.6. Mineral composition and phytic acid determination

2.7. Statistical analysis

3. Results and discussion

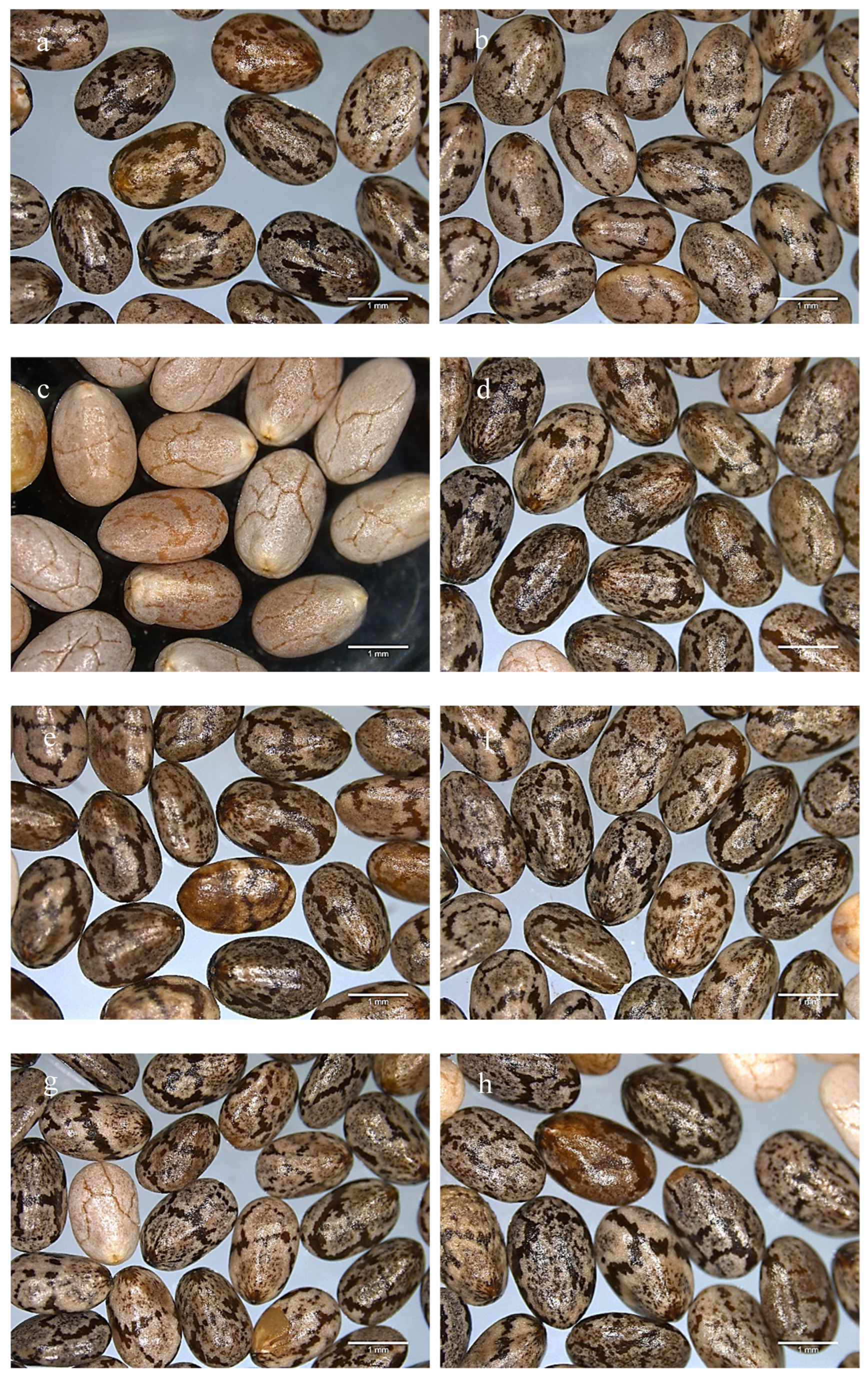

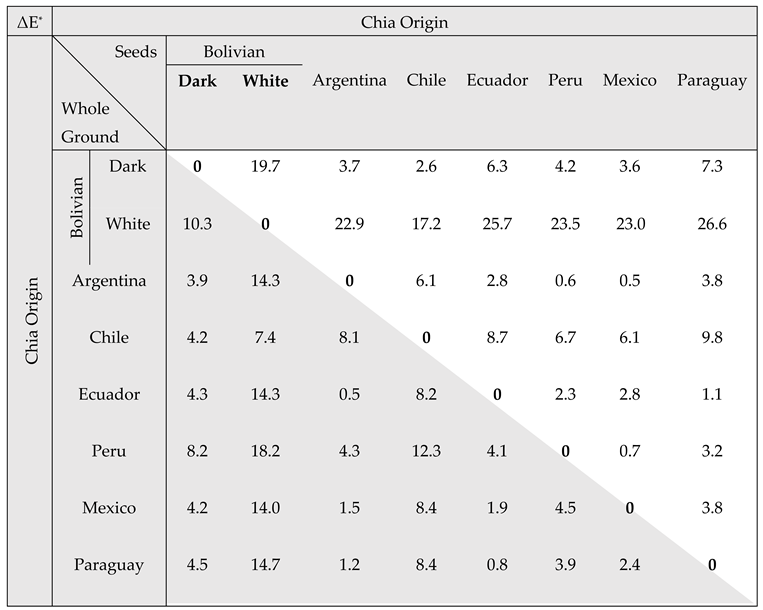

3.1. Physical properties and morphology of chia seeds from different origins

3.2. Proximate chemical composition of seeds

| Component (g/100g d.m.) |

Bolivian | Argentina | Chile | Ecuador | Peru | Mexico | Paraguay | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dark | White | |||||||||||||||

| Moisture | 8.62 | ± 0.13g | 7.09 | ± 0.11a | 8.20 | ± 0.10d | 9.15 | ± 0.21h | 7.89 | ± 0.15c | 8.46 | ± 0.08f | 8.35 | ± 0.08e | 7.13 | ± 0.10b |

| Protein | 21.4 | ± 0.4d | 24.3 | ± 0.0e | 20.3 | ± 0.1c | 22.2 | ± 0.1d | 17.7 | ± 0.1a | 19.4 | ± 0.0b | 20.2 | ±0.0c | 20.4 | ± 0.1c |

| Lipids | 32.1 | ± 0.8bc | 29.0 | ± 0.0a | 30.6 | ± 0.7ab | 34.9 | ± 0.6d | 30.8 | ± 0.1ab | 30.5 | ± 0.6ab | 30.1 | ±0.5ab | 34.5 | ± 0.2cd |

| Ash | 4.48 | ± 0.21a | 4.34 | ± 0.03a | 4.43 | ± 0.28a | 4.79 | ± 0.27a | 4.31 | ± 0.24a | 4.79 | ± 0.03a | 4.47 | ± 0.32a | 4.34 | ± 0.22a |

| Total Dietary Fiber* | 20.0 | ± 0.8de | 18.5 | ± 1.5bc | 18.4 | ± 1.3cd | 21.1 | ± 0.1ef | 22.4 | ± 0.4f | 26.0 | ± 0.3e | 17.0 | ± 0.6ab | 16.8 | ± 0.2a |

| Soluble (S) | 4.55 | ± 0.01bc | 5.41 | ± 1.20c | 2.80 | ± 0.61a | 4.21 | ± 0.65abc | 3.50 | ± 0.80ab | 5.46 | ± 1.50d | 4.25 | ± 0.10abc | 4.51 | ± 0.05abc |

| Insoluble (I) | 15.5 | ± 0.0c | 13.1 | ± 1.2b | 15.6 | ± 0.6c | 16.9 | ± 0.6cd | 18.8 | ± 0.9d | 20.5 | ± 1.5a | 12.8 | ± 0.1b | 12.3 | ± 0.1b |

| Ratio (S)/(I) | 1:4.4 | 1:2.5 | 1:5.6 | 1:4.1 | 1:5.5 | 1:3.8 | 1:3.0 | 1:2.7 | ||||||||

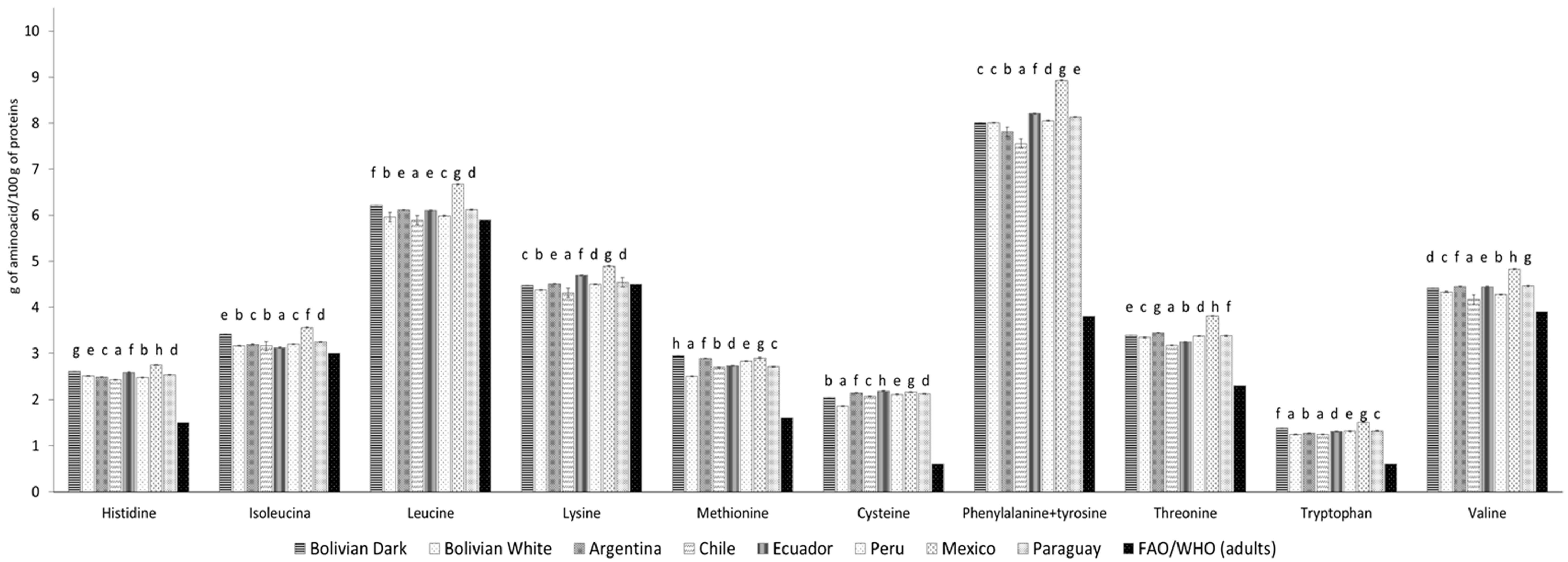

3.3. Amino acid profile

3.4. Fatty acids profile

3.5. Mineral composition

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Muñoz, L.A.; Cobos, A.; Diaz, O.; Aguilera, J.M. Chia Seed (Salvia hispanica): An Ancient Grain and a New Functional Food. Food Reviews International 2013, 29, 394-408. [CrossRef]

- Ayerza, R.; Coates, W. Protein content, oil content and fatty acid profiles as potential criteria to determine the origin of commercially grown chia (Salvia hispanica L.). Industrial Crops and Products 2011, 34, 1366-1371. [CrossRef]

- American-Dietetic-Association. Position of the American Dietetic Association: Health Implications of Dietary Fiber; 0002-8223; 10// 2008; pp. 1716-1731.

- EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, N., and Allergies (NDA). Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for carbohydrates and dietary fibre. EFSA Journal 2010, 8, 1462. [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Oliveros, M.R.; Paredes-López, O. Isolation and Characterization of Proteins from Chia Seeds (Salvia hispanica L.). Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2013, 61, 193-201. [CrossRef]

- Marcinek, K.; Krejpcio, Z. Chia seeds (Salvia hispanica): health promoting properties and therapeutic applications – a review. Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig. 2017, 68, 123-129.

- Sloan, E. Top 10 functional food trends. Food Technology 2018.

- Orozco de Rosas, G.; Durán Puga, N.; González Eguiarte, D.R.; Zarazúa Villaseñor, P.; Ramírez Ojeda, G.; Mena Munguía, S. Proyecciones de cambio climático y potencial productivo para Salvia hispánica L. en las zonas agrícolas de México. Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas 2014, 5, 1831-1842.

- Ayerza, R.; Coates, W. Influence of environment on growing period and yield, protein, oil and α-linolenic content of three chia (Salvia hispanica L.) selections. Industrial Crops and Products 2009, 30, 321-324. [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Authorising the placing on the market of Chia seed (Salvia hispanica) as novel food ingredient under Regulation (EC) No 258/97 of the European Parliament and of the Council (2009/827/EC). Official Journal of the Europen Union 2009, L 294/14-294/15.

- EFSA. Authorising the placing on the market of chia oil (Salvia hispanica) as a novel food ingredient under Regulation (EC) No 258/97 of the European Parliament and of the Council (2014/890/EU). Official Journal of the Europen Union 2014, L 353/15-294/16.

- CBI. Exporting chia seeds to Europe. 2019.

- Muñoz, L.A.; Cobos, A.; Diaz, O.; Aguilera, J.M. Chia seeds: Microstructure, mucilage extraction and hydration. Journal of Food Engineering 2012, 108, 216-224. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nature methods 2012, 9, 671-675. [CrossRef]

- Tunde-Akintunde, T.Y.; Akintunde, B.O. Some Physical Properties of Sesame Seed. Biosystems Engineering 2004, 88, 127-129. [CrossRef]

- Ixtaina, V.Y.; Nolasco, S.M.; Tomás, M.C. Physical properties of chia (Salvia hispanica L.) seeds. Industrial Crops and Products 2008, 28, 286-293. [CrossRef]

- AACC. Method 30 - 20: Crude fat in grain and stock feeds, method 44 -15A: Moisture, method 46-13: Crude protein-Micro-Kjeldahl method, method 54 - 21: Farinograph method for flour.; AACC: Sain Paul, Minnesota, 1995.

- AACC. Method 08-03.01: Ash -- Rapid Method; AACC: Cereals & Grains Association, 2000.

- Lee, S.C.; Prosky, L.; De Vries, J.W. Determination of total, soluble, and insoluble dietary fiber in foods: enzymatic-gravimetric method, MES-TRIS buffer: collaborative study. Journal of the Association of Official Analytical Chemists 1992, 75, 395-416.

- ISO 13903. ISO 13903:2005 Animal feeding stuffs — Determination of amino acids content. 2005.

- EU 152/2009. No 152/2009 Methods of sampling and analysis for the official control of feed. 2009.

- Folch, J.; Lees, M.; Sloane Stanley, G.H. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. The Journal of biological chemistry 1957, 226, 497-509.

- Rincón-Cervera, M.Á.; Galleguillos-Fernández, R.; González-Barriga, V.; Valenzuela, R.; Speisky, H.; Fuentes, J.; Valenzuela, A. Fatty Acid Profile and Bioactive Compound Extraction in Purple Viper's Bugloss Seed Oil Extracted with Green Solvents. Journal of the American Oil Chemists' Society 2020, 97, 319-327. [CrossRef]

- Razavi, S.; Mortazavi, S.A.; Matia-Merino, L.; Hosseini-Parvar, S.H.; Motamedzadegan, A.; Khanipour, E. Optimisation study of gum extraction from Basil seeds (Ocimum basilicum L.). International Journal of Food Science & Technology 2009, 44, 1755-1762. [CrossRef]

- Knez Hrnčič, M.; Ivanovski, M.; Cör, D.; Knez, Ž. Chia Seeds (Salvia hispanica L.): An Overview-Phytochemical Profile, Isolation Methods, and Application. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 2019, 25, 11. [CrossRef]

- Amato, M.; Caruso, M.C.; Guzzo, F.; Galgano, F.; Commisso, M.; Bochicchio, R.; Labella, R.; Favati, F. Nutritional quality of seeds and leaf metabolites of Chia (Salvia hispanica L.) from Southern Italy. European Food Research and Technology 2015, 241, 615-625. [CrossRef]

- Mokrzycki, W.S.; Tatol, M. Colour difference ΔE - a survey. Machine Graphics & Vision International Journal 2011, 20, 1230-0535.

- Challacombe, C.A.; Seetharaman, K.; Duizer, L.M. Sensory Characteristics and Consumer Acceptance of Bread and Cracker Products Made from Red or White Wheat. Journal of Food Science 2011, 76, S337-S346. [CrossRef]

- Pereira da Silva, B.; Anunciação, P.C.; Matyelka, J.C.d.S.; Della Lucia, C.M.; Martino, H.S.D.; Pinheiro-Sant'Ana, H.M. Chemical composition of Brazilian chia seeds grown in different places. Food Chemistry 2017, 221, 1709-1716. [CrossRef]

- Ayerza, R.; Coates, W. Composition of chia (Salvia hispanica) grown in six tropical and subtropical ecosystems of South America. Tropical Science 2004, 44, 131-135. [CrossRef]

- Porras-Loaiza, P.; Jiménez-Munguía, M.T.; Sosa-Morales, M.E.; Palou, E.; López-Malo, A. Physical properties, chemical characterization and fatty acid composition of Mexican chia (<i>Salvia hispanica</i>L.) seeds. International Journal of Food Science & Technology 2014, 49, 571-577. [CrossRef]

- Maradini Filho, A.M.; Ribeiro Pirozi, M.; Da Silva Borges, J.T.; Pinheiro Sant'Ana, H.M.; Paes Chaves, J.B.; Dos Reis Coimbra, J.S. Quinoa: Nutritional, functional, and antinutritional aspects. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2017, 57, 1618-1630. [CrossRef]

- Venskutonis, P.R.; Kraujalis, P. Nutritional Components of Amaranth Seeds and Vegetables: A Review on Composition, Properties, and Uses. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2013, 12, 381-412. [CrossRef]

- Bozan, B.; Temelli, F. Chemical composition and oxidative stability of flax, safflower and poppy seed and seed oils. Bioresource Technology 2008, 99, 6354-6359. [CrossRef]

- de Lamo, B.; Gómez, M. Bread Enrichment with Oilseeds. A Review. Foods 2018, 7. [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Zheng, L.; Jin, J.; Li, X.; Fu, J.; Wang, M.; Guan, Y.; Song, X. Phytochemical and Biological Characteristics of Mexican Chia Seed Oil. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 2018, 23, 3219. [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Scientific Opinion on principles for deriving and applying Dietary Reference Values. EFSA Journal 2010, 8, 1458. [CrossRef]

- 38. FDA. Nutrition Facts Label: Dietary Fiber. 2018, 2018.

- EFSA. Dietary Reference Values for nutrients Summary report. 2017, 14, e15121E. [CrossRef]

- WHO/FAO/UNU. Protein and aminoacid requirements in human nutrition; WHO, World Health Organization: 2007.

- Olivos-Lugo, B.L.; Valdivia-López, M.; Tecante, A. Thermal and physicochemical properties and nutritional value of the protein fraction of Mexican chia seed (Salvia hispanica L.). Food Sci Technol Int 2010, 16, 89-96. [CrossRef]

- Ayerza, R. Seed composition of two chia (salvia hispanica L.) genotypes which differ in seed color. Emirates Journal of Food and Agriculture 2013, 27, 495-500.

- Ding, Y.; Lin, H.-W.; Lin, Y.-L.; Yang, D.-J.; Yu, Y.-S.; Chen, J.-W.; Wang, S.-Y.; Chen, Y.-C. Nutritional composition in the chia seed and its processing properties on restructured ham-like products. Journal of Food and Drug Analysis 2018, 26, 124-134. [CrossRef]

- Miranda-Ramos, K.; Millán-Linares, M.C.; Haros; Claudia, M. Effect of Chia as Breadmaking Ingredient on Nutritional Quality, Mineral Availability, and Glycemic Index of Bread. Foods 2020, 9, 663. [CrossRef]

- Ixtaina, V.Y.; Martínez, M.L.; Spotorno, V.; Mateo, C.M.; Maestri, D.M.; Diehl, B.W.K.; Nolasco, S.M.; Tomás, M.C. Characterization of chia seed oils obtained by pressing and solvent extraction. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2011, 24, 166-174. [CrossRef]

- Kulczyński, B.; Kobus-Cisowska, J.; Taczanowski, M.; Kmiecik, D.; Gramza-Michałowska, A. The Chemical Composition and Nutritional Value of Chia Seeds-Current State of Knowledge. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1242. [CrossRef]

- Mihafu, F.D.; Kiage, B.N.; Okoth, J.K.; Nyerere, A.K. Nutritional Composition and Qualitative Phytochemical Analysis of Chia Seeds (Salvia hispanica L.) Grown in East Africa. Current Nutrition & Food Science 2020, 16, 988-995. [CrossRef]

- EFSA NDA Panel. Safety of chia seeds (Salvia hispanica L.) as a novel food for extended uses pursuant to Regulation (EU) 2015/2283. 2019, 17, e05657. [CrossRef]

- Mohd Ali, N.; Yeap, S.K.; Ho, W.Y.; Beh, B.K.; Tan, S.W.; Tan, S.G. The Promising Future of Chia, Salvia hispanica L. Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology 2012, 2012, 9. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Sun, B.; Zhang, D. Association of Dietary n3 and n6 Fatty Acids Intake with Hypertension: NHANES 2007–2014. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1232. [CrossRef]

- Simopoulos, A.P. The importance of the ratio of omega-6/omega-3 essential fatty acids. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2002, 56, 365-379. [CrossRef]

- Simopoulos, A.P. The omega-6/omega-3 fatty acid ratio: health implications. OCL 2010, 17, 267-275. [CrossRef]

- Simopoulos, A.P. An Increase in the Omega-6/Omega-3 Fatty Acid Ratio Increases the Risk for Obesity. Nutrients 2016, 8, 128.

- Boschin, G.; D’Agostina, A.; Annicchiarico, P.; Arnoldi, A. The fatty acid composition of the oil from Lupinus albus cv. Luxe as affected by environmental and agricultural factors. European Food Research and Technology 2007, 225, 769-776. [CrossRef]

- Food and Nutrition Board. Nutrient Recommendations: Dietary Reference Intakes (DRI). DRI Table: Recommended Dietary Allowances and Adequate Intakes, Total Water and Macronutrients 2017.

- Barreto, A.; Gutierrez, É.; Silva, M.; Silva, F.; Silva, N.; Lacerda, I.; Labanca, R.; Araújo, R. Characterization and Bioaccessibility of Minerals in Seeds of Salvia hispanica L. American Journal of Plant Sciences 2016, 07, 2323-2337. [CrossRef]

- USDA. FoodData Central Search Results: Seeds, chia seeds, dried. Available online: https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/fdc-app.html#/food-details/170554/nutrients (accessed on.

- Singh, B.; Schuelze, D.G. Soil Minerals and Plant Nutrition. Nature Education Knowledge 2015, 6.

- EFSA. Review of labelling reference intake values. EFSA Journal 2009, 1-14.

- Bojórquez-Quintal, E.; Escalante-Magaña, C.; Echevarría-Machado, I.; Martínez-Estévez, M. Aluminum, a Friend or Foe of Higher Plants in Acid Soils. Frontiers in Plant Science 2017, 8. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Safety evaluation of certain food additives and contaminants. 2011, 119-207.

- Scherer, H.W. Sulphur in crop production — invited paper. European Journal of Agronomy 2001, 14, 81-111. [CrossRef]

- van de Poll, M.C.; Dejong, C.H.; Soeters, P.B. Adequate range for sulfur-containing amino acids and biomarkers for their excess: lessons from enteral and parenteral nutrition. J Nutr 2006, 136, 1694s-1700s. [CrossRef]

- Baroni, T.R. Caracterizacão nutricional e funcional da farinha de chia (Salvia Hispanica) e sua aplicacao no desenvolvimento de pães. Universidade de Sao Paulo, 2013.

- Hurrell, R.; Egli, I. Iron bioavailability and dietary reference values. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2010, 91, 1461S-1467S. [CrossRef]

- Piste, P.; Sayaji, D.; Avinash, M. Calcium and its Role in Human Body. Int J Res Pharm Biomed Sci 2012, 4, 2229-3701.

- Fretham, S.J.B.; Carlson, E.S.; Georgieff, M.K. The Role of Iron in Learning and Memory. Advances in Nutrition 2011, 2, 112-121. [CrossRef]

- De Benoist, B.; Cogswell, M.; Egli, I.; McLean, E. Worldwide prevalence of anaemia 1993-2005; WHO Global Database of anaemia. 2008.

- Lieu, P.T.; Heiskala, M.; Peterson, P.A.; Yang, Y.J.M.a.o.m. The roles of iron in health and disease. 2001, 22, 1-87. [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.H.; Wuehler, S.E.; Peerson, J.M. The Importance of Zinc in Human Nutrition and Estimation of the Global Prevalence of Zinc Deficiency. 2001, 22, 113-125. [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Units | Bolivian | Argentina | Chile | Ecuador | Peru | Mexico | Paraguay | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dark | White | ||||||||||||||||

| 1000-seed mass | g | 1.38 | ± 0.01e | 1.26 | ± 0.02b | 1.26 | ± 0.03b | 1.26 | ± 0.01b | 1.10 | ± 0.02a | 1.31 | ± 0.02d | 1.29 | ± 0.02d | 1.46 | ± 0.01c |

| Bulk density | g/m3 | 69.7 | ± 1.1d | 68.2 | ± 0.3abc | 69.4 | ± 0.4cd | 71.2 | ± 0.4e | 68.5 | ± 1.9bcd | 67.0 | ± 0.1a | 67.8 | ± 0.2ab | 72.9 | ± 0.1f |

| True Density | g/m3 | 1154 | ± 40cd | 1162 | ± 0cd | 1102 | ± 0b | 1163 | ± 0d | 1110 | ± 0ab | 1147 | ± 0c | 1122 | ± 0a | 1153 | ± 0cd |

| Porosity (ε) | % | 94.0 | ± 0.5e | 94.1 | ± 0.1f | 93.7 | ± 0.2b | 93.9 | ± 0.2d | 93.83 | ± 0.9a | 94.2 | ± 0.0g | 94.0 | ± 0.1e | 93.7 | ± 0.1a |

| Length | mm | 1.98 | ± 0.11b | 2.02 | ± 0.10cd | 2.00 | ± 0.12bd | 1.87 | ± 0.09a | 1.87 | ± 0.12a | 2.03 | ± 1.14cd | 2.01 | ± 0.10bd | 2.06 | ± 0.10c |

| Width | mm | 1.35 | ± 0.13e | 1.35 | ± 0.09de | 1.25 | ± 0.12b | 1.37 | ± 0.09e | 1.19 | ± 0.10a | 1.31 | ± 0.13cd | 1.30 | ± 0.12c | 1.31 | ± 0.08cd |

| Thickness | mm | 0.957 | ± 0.081a | 1.08 | ± 0.12c | 0.953 | ± 0.078a | 1.01 | ± 0.09b | 0.946 | ± 0.085a | 0.937 | ± 0.091a | 0.973 | ± 0.086a | 1.01 | ± 0.11b |

| Equivalent diameter | mm | 0.833 | ± 0.002a | 0.828 | ± 0.012a | 0.878 | ± 0.010c | 0.833 | ± 0.016a | 0.867 | ± 0.003c | 0.838 | ± 0.019ab | 0.859 | ± 0.010bc | 0.843 | ± 0.021ab |

| Sphericity (Φ) | % | 0.691 | ± 0.038c | 0.706 | ± 0.033d | 0.667 | ± 0.024b | 0.734 | ± 0.034e | 0.686 | ± 0.034ac | 0.667 | ± 0.034b | 0.678 | ± 0.028abc | 0.678 | ± 0.036ab |

| Surface area | mm2 | 5.86 | ± 0.52d | 6.42 | ± 0.58e | 5.61 | ± 0.63b | 5.93 | ± 0.55cd | 5.15 | ± 0.55a | 5.76 | ± 0.65bd | 5.84 | ± 0.57d | 6.11 | ± 0.55c |

| Volume | mm3 | 1.31 | ± 0.01a | 1.30 | ± 0.02a | 1.38 | ± 0.02c | 1.31 | ± 0.03a | 1.36 | ± 0.01c | 1.32 | ± 0.03ab | 1.35 | ± 0.02bc | 1.32 | ± 0.03ab |

| Arithmetic mean diameter | mm | 1.43 | ± 0.06d | 1.48 | ± 0.06c | 1.40 | ± 0.08b | 1.42 | ± 0.06bd | 1.33 | ± 0.07a | 1.42 | ± 0.08bd | 1.43 | ± 0.07bd | 1.46 | ± 0.06c |

| Geometric mean diameter | mm | 1.36 | ± 0.06d | 1.43 | ± 0.06e | 1.33 | ± 0.08b | 1.37 | ± 0.06cd | 1.28 | ± 0.07a | 1.35 | ± 0.08bd | 1.36 | ± 0.07d | 1.39 | ± 0.06c |

| Color parameters | Bolivian | Argentina | Chile | Ecuador | Peru | Mexico | Paraguay | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dark | White | ||||||||||||||||

| Seeds | L* | 39.6 | ± 0.5c | 59.2 | ± 0.9e | 36.3 | ± 0.2b | 42.1 | ± 0.8d | 33.5 | ± 0.6a | 35.7 | ± 0.8b | 36.3 | ± 0.6b | 32.6 | ± 0.5a |

| a* | 1.40 | ± 0.26a | 3.27 | ± 0.47de | 2.82 | ± 0.05cd | 1.66 | ± 0.47a | 2.84 | ± 0.13cd | 2.77 | ± 0.02bc | 2.31 | ± 0.07b | 3.35 | ± 0.22e | |

| b* | 11.1 | ± 0.3a | 12.1 | ± 0.1c | 12.2 | ± 0.1c | 10.8 | ± 0.4a | 11.6 | ± 0.2b | 12.2 | ± 0.1c | 12.2 | ± 0.2c | 11.9 | ± 0.1bc | |

| Whole Ground Seeds | L* | 49.8 | ± 0.0d | 58.9 | ± 0.0f | 46.0 | ± 0.0c | 54.0 | ± 0.1e | 45.8 | ± 0.1c | 41.7 | ± 0.0a | 45.7 | ± 0.1d | 45.7 | ± 0.1b |

| a* | 1.81 | ± 0.02c | 3.57 | ± 0.03f | 2.26 | ± 0.03e | 1.35 | ± 0.05a | 2.31 | ± 0.03e | 2.28 | ± 0.07a | 1.47 | ± 0.02b | 1.97 | ± 0.07d | |

| b* | 11.0 | ± 0.0f | 15.4 | ± 0.0h | 10.3 | ± 0.0d | 10.4 | ± 0.0e | 9.9 | ± 0.0c | 9.5 | ± 0.0b | 11.5 | ± 0.0g | 9.2 | ± 0.0a | |

|

| Amino acid composition g/100g seeds |

Bolivian | Argentina | Chile | Ecuador | Peru | Mexico | Paraguay | |||||||||

| Dark | White | |||||||||||||||

| No essential | ||||||||||||||||

| Alanine | 1.21 | ± 0.01d | 1.09 | ± 0.04c | 0.969 | ± 0.011b | 1.10 | ± 0.06c | 0.897 | ± 0.002a | 0.942 | ± 0.020ab | 1.11 | ± 0.01c | 1.04 | ± 0.03c |

| Arginine | 2.62 | ± 0.05e | 2.18 | ± 0.15d | 1.98 | ± 0.04bc | 2.16 | ± 0.11cd | 1.78 | ± 0.08a | 1.92 | ± 0.01ab | 2.28 | ± 0.06d | 2.16 | ± 0.11cd |

| Aspartic acid | 2.25 | ± 0.02f | 1.93 | ± 0.08de | 1.75 | ± 0.01bc | 1.83 | ± 0.11cd | 1.47 | ± 0.02a | 1.65 | ± 0.01b | 2.03 | ± 0.01e | 1.81 | ± 0.06cd |

| Glutamic acid | 4.41 | ± 0.10c | 3.78 | ± 0.23b | 3.40 | ± 0.04a | 3.76 | ± 0.28b | 3.17 | ± 0.01a | 3.41 | ± 0.01a | 3.98 | ± 0.06b | 3.83 | ± 0.15b |

| Glycine | 1.14 | ± 0.01f | 1.03 | ± 0.03de | 0.955 | ± 0.029bc | 0.967 | ± 0.047bc | 0.880 | ± 0.011a | 0.937 | ± 0.004b | 1.06 | ± 0.01e | 1.00 | ± 0.01cd |

| Proline | 0.944 | ± 0.074d | 0.819 | ± 0.047bc | 0.821 | ± 0.044abc | 0.809 | ± 0.036bc | 0.752 | ± 0.041a | 0.875 | ± 0.069bcd | 0.933 | ± 0.037cd | 0.851 | ± 0.013abcd |

| Serine | 1.37 | ± 0.07e | 1.21 | ± 0.04d | 1.09 | ± 0.02bc | 1.17 | ± 0.06cd | 0.969 | ± 0.020a | 1.06 | ± 0.00ab | 1.22 | ± 0.04d | 1.12 | ± 0.03bcdc |

| Essential amino acid | ||||||||||||||||

| Tryptophan | 0.333 | ± 0.016a | 0.321 | ± 0.001 a | 0.268 | ± 0.001a | 0.299 | ± 0.001a | 0.253 | ± 0.005a | 0.278 | ± 0.016a | 0.331 | ± 0.013a | 0.297 | ± 0.020a |

| Cysteine | 0.497 | ± 0.004d | 0.475 | ± 0.004cd | 0.453 | ± 0.002bc | 0.497 | ± 0.009d | 0.422 | ± 0.000a | 0.447 | ± 0.023ab | 0.475 | ± 0.021cd | 0.479 | ± 0.002cd |

| Methionine | 0.671 | ± 0.006de | 0.686 | ± 0.025e | 0.610 | ± 0.018bc | 0.646 | ±0.042cde | 0.527 | ± 0.018a | 0.598 | ± 0.004b | 0.637 | ± 0.006bcd | 0.609 | ± 0.004bc |

| Histidine | 0.673 | ± 0.042d | 0.606 | ± 0.023c | 0.525 | ± 0.021ab | 0.583 | ± 0.042c | 0.500 | ± 0.008a | 0.524 | ± 0.000ab | 0.603 | ± 0.006c | 0.571 | ± 0.008bc |

| Isoluecine | 0.847 | ± 0.012d | 0.795 | ± 0.044cd | 0.673 | ± 0.023ab | 0.758 | ± 0.071c | 0.604 | ± 0.002a | 0.675 | ± 0.018ab | 0.781 | ± 0.003cd | 0.729 | ± 0.023bc |

| Leucine | 1.60 | ± 0.05d | 1.45 | ± 0.08c | 1.29 | ± 0.01ab | 1.42 | ± 0.11c | 1.18 | ± 0.00a | 1.27 | ± 0.04ab | 1.47 | ± 0.01c | 1.38 | ± 0.04bc |

| Lysine | 1.17 | ± 0.03d | 1.04 | ± 0.04c | 0.952 | ± 0.021ab | 1.04 | ± 0.05c | 0.907 | ± 0.008a | 0.951 | ± 0.006ab | 1.08 | ± 0.04c | 1.02 | ± 0.06bc |

| Phenylalanine | 1.27 | ± 0.01d | 1.12 | ± 0.06c | 0.985 | ± 0.049ab | 1.08 | ± 0.08bc | 0.939 | ± 0.038a | 1.01 | ± 0.04ab | 1.16 | ± 0.02c | 1.08 | ± 0.03bc |

| Threonine | 0.896 | ± 0.030e | 0.789 | ± 0.015cd | 0.726 | ± 0.004b | 0.762 | ± 0.042bc | 0.628 | ± 0.008a | 0.714 | ± 0.025b | 0.837 | ± 0.001d | 0.759 | ± 0.024bc |

| Tyrosine | 0.878 | ± 0.007c | 0.741 | ± 0.048ab | 0.663 | ± 0.054a | 0.734 | ± 0.040ab | 0.647 | ± 0.006a | 0.689 | ± 0.035a | 0.806 | ± 0.086bc | 0.748 | ± 0.045ab |

| Valine | 1.16 | ± 0.00d | 1.03 | ± 0.06c | 0.939 | ± 0.021ab | 1.00 | ± 0.07bc | 0.859 | ± 0.003a | 0.905 | ± 0.009a | 1.06 | ± 0.00c | 1.00 | ± 0.02bc |

| EAAs | 9.98 | 9.04 | 8.08 | 8.81 | 7.46 | 8.06 | 9.22 | 8.67 | ||||||||

| Parameter Fatty acid |

Units or Reference Values | Bolivian | Argentina | Chile | Ecuador | Peru | Mexico | Paraguay | ||||||||||

| Dark | White | |||||||||||||||||

| Palmitic acid | C16:0 | g/100g d.m. | 2.11 | ± 0.15g | 2.15 | ± 0.25h | 1.89 | ± 0.22a | 1.91 | ± 0.12b | 2.10 | ± 0.13f | 1.95 | ± 0.11c | 2.02 | ± 0.25e | 2.00 | ± 0.14d |

| Stearic acid | C18:0 | g/100g d.m. | 0.94 | ± 0.23c | 1.01 | ± 0.18f | 0.84 | ± 0.47a | 0.86 | ± 0.04b | 0.95 | ± 0.04d | 1.01 | ± 0.06f | 1.05 | ± 0.11g | 1.00 | ± 0.11e |

| Arachidic acid | C20:0 | g/100g d.m. | 0.07 | ± 0.00b | 0.08 | ± 0.02c | 0.07 | ± 0.00b | 0.06 | ± 0.00a | 0.07 | ± 0.00b | 0.08 | ± 0.02c | 0.07 | ± 0.05b | 0.08 | ± 0.01c |

| ƩSFA | 3.12 | 3.24 | 2.80 | 2.83 | 3.12 | 3.04 | 3.14 | 3.08 | ||||||||||

| Palmitoleic acid | C16:1n7 | g/100g d.m. | 0.05 | ± 0.01a | 0.08 | ± 0.01d | 0.06 | ± 0.01b | 0.06 | ± 0.04b | 0.07 | ± 0.01c | 0.06 | ± 0.01b | 0.07 | ± 0.01c | 0.06 | ± 0.01b |

| Oleic acid | C18:1n9 | g/100g d.m. | 1.74 | ± 0.40d | 2.02 | ± 0.21g | 1.50 | ± 0.16b | 1.40 | ± 0.03a | 1.55 | ± 0.07c | 1.97 | ± 0.23f | 2.67 | ± 0.19h | 1.96 | ± 0.10e |

| Vaccenic acid | C18:1n7 | g/100g d.m. | 0.14 | ± 0.05c | 0.14 | ± 0.00c | 0.13 | ± 0.11b | 0.13 | ± 0.08b | 0.14 | ± 0.08c | 0.13 | ± 0.09b | 0.12 | ± 0.08a | 0.13 | ± 0.06b |

| ƩMUFA | 1.93 | 2.24 | 1.69 | 1.59 | 1.76 | 2.16 | 2.86 | 2.15 | ||||||||||

| Linoleic acid (LA) | C18:2n6c | g/100g d.m. | 5.56 | ± 0.25e | 5.66 | ± 0.11f | 5.28 | ± 0.30c | 4.88 | ± 0.31a | 5.15 | ± 0.34b | 5.50 | ± 0.66d | 5.97 | ± 0.13g | 5.56 | ± 0.52e |

| γ-Linolenic acid | C18:3n6 | g/100g d.m. | 0.05 | ± 0.01a | 0.06 | ± 0.04b | 0.05 | ± 0.01a | 0.05 | ± 0.01a | 0.06 | ± 0.00b | 0.06 | ± 0.01b | 0.05 | ± 0.02a | 0.05 | ± 0.01a |

| α-Linolenic acid (ALA) | C18:3n3 | g/100g d.m. | 16.9 | ± 1.1c | 15.6 | ± 0.5b | 18.2 | ± 0.8g | 18.4 | ± 0.6h | 17.4 | ± 0.0d | 18.1 | ± 0.6f | 14.9 | ± 0.2a | 18.0 | ± 0.3e |

| ƩPUFA | 22.49 | 21.32 | 23.57 | 23.28 | 22.64 | 23.62 | 20.93 | 23.59 | ||||||||||

| LA/ALA | C18:2n6c/ C18:3n3 | g/g | 1/3 | 1/2.8 | 1/3.5 | 1/3.8 | 1/3.4 | 1/3.3 | 1/2.5 | 1/3.2 | ||||||||

| % of contribution of AI E% for LAa | FAO | 2.5 E% | 13.2 | 13.5 | 12.6 | 11.6 | 12.3 | 13.1 | 14.2 | 13.2 | ||||||||

| EFSA | 4 E% | 8.27 | 8.42 | 8.27 | 7.26 | 7.66 | 8.18 | 8.88 | 8.27 | |||||||||

| % of DRI of LAa | EFSA | 17 g/day (Male) | 4.91 | 4.99 | 4.66 | 4.31 | 4.54 | 4.85 | 5.27 | 4.91 | ||||||||

| 12 g/day (Female) | 7.0 | 7.1 | 6.6 | 6.1 | 6.4 | 6.8 | 7.5 | 7.0 | ||||||||||

| % of contribution of AI E% for ALAa | FAO/EFSA | 0.5 E% | 201 | 186 | 217 | 218 | 208 | 215 | 177 | 214 | ||||||||

|

% of DRI of ALAa |

EFSA | 1.6 g/day (Male) | 158 | 146 | 171 | 172 | 164 | 169 | 140 | 169 | ||||||||

| 1.1 g/day (Female) | 230 | 213 | 249 | 250 | 238 | 246 | 203 | 245 | ||||||||||

| Parameter | Units | Bolivian | Argentina | Chile | Ecuador | Peru | Mexico | Paraguay | ||||

| Dark | White | |||||||||||

| Ins P6 | g/100g d.m. | 2.6 ± 0.0d | 1.5 ± 0.03a | 2.2 ± 0.04c | 2.6 ± 0.05d | 2.2 ± 0.07c | 1.9 ± 0.0b | 2.3 ± 0.06c | 2.2 ± 0.01c | |||

| Macroelements | Na | mg/100g d.m. | 1.2 ± 1.4a | 1.0± 0.5a | 1.3 ± 0.1a | 1.0 ± 0.0a | 1.2 ± 0.0a | 1.4 ± 0.1a | 1.2 ± 0.6a | 0.8 ± 0.0a | ||

| Ca | mg/100g d.m. | 498.9 ± 0.1ab | 492.3 ± 0.3ab | 537.1 ± 0.1abc | 671.1 ± 0.2c | 481.5 ± 0.2ab | 613.4 ± 0.2bc | 530.9 ± 0.3ab | 460 ± 0.1a | |||

| P | mg/100g d.m. | 549.6 ± 0.4d | 393.9 ± 0.7a | 472.3 ± 0.5bc | 661.9 ± 0.4e | 482 ± 0.4bcd | 409.1 ± 0.8ab | 474.2 ± 1.1bc | 540.3 ± 0.7cd | |||

| Mg | mg/100g d.m. | 280.8 ± 0.5abc | 262.6 ± 0.2ab | 263.8 ± 0.3ab | 321.6 ± 0.3d | 301.2 ± 0.9bcd | 261.7 ± 0.3a | 250 ± 0.4a | 308.6 ± 0.2cd | |||

| Microelements | Zn | mg/100g d.m. | 3.69 ± 0.00e | 4.83 ± 0.01cd | 2.69 ± 0.03a | 5.16 ± 0.01f | 3.69 ± 0.00cd | 3.55 ± 0.01bc | 3.37 ± 0.04b | 3.94 ± 0.01d | ||

| Fe | mg/100g d.m. | 7.79 ± 0.58a | 7.55 ± 0.25a | 6.12 ± 0.06a | 5.57 ± 0.13a | 5.74 ± 0.02a | 23.4 ± 0.97b | 4.23 ± 0.05a | 4.64 ± 0.00a | |||

| Mn | mg/100g d.m. | 2.06 ± 0.04c | 1.47 ± 0.01b | 2.49 ± 0.00d | 0.94 ± 0.00a | 3.95 ± 0.02f | 2.58 ± 0.01d | 2.96 ± 0.04e | 5.95 ± 0.01g | |||

| Cu | mg/100g d.m. | 1.07 ± 0.01b | 1.50 ± 0.01cd | 0.91 ± 0.01a | 1.58 ± 0.00d | 1.42 ± 0.01cd | 1.28 ± 0.00c | 0.86 ± 0.01a | 1.32 ± 0.02c | |||

| Al | mg/100g d.m. | 1.95 ± 0.37a | 2.15 ± 0.11a | 3.02 ± 0.01a | 0.59 ± 0.03a | 4.35 ± 0.39a | 41.15 ± 0.16b | 0.8 ± 0.02a | 0.25 ± 0.03a | |||

| S | mg/100g d.m. | 180 ± 1abc | 216 ± 1d | 175± 0ab | 223± 1d | 170 ± 1a | 194 ± 1c | 166 ± 0a | 190 ± 1bc | |||

| Ratio | Ins P6/Ca < 0.24 | mol/mol | 0.37 | 0.22 | 0.29 | 0.27 | 0.32 | 0.22 | 0.30 | 0.35 | ||

| Ins P6/Fe < 1 | mol/mol | 32.9 | 20.2 | 35.6 | 46.1 | 37.9 | 8.0 | 52.6 | 47.8 | |||

| Ins P6/Zn < 15 | mol/mol | 81.4 | 37.1 | 94.9 | 58.3 | 69.1 | 61.3 | 77.3 | 65.8 | |||

| Contribution to DRIs (%)b | Na | DRIsa 1500 | mg/day | 4.7 | 4.9 | 5.4 | 6.7 | 4.8 | 6.1 | 5.3 | 4.6 | |

| Ca | DRIsa 1000 | mg/day | 7.4 | 7.4 | 8.1 | 10.1 | 7.2 | 9.2 | 8.0 | 6.9 | ||

| P | DRIsa 550 | mg/day | 15.0 | 10.7 | 12.9 | 18.1 | 13.2 | 11.2 | 12.9 | 12.9 | ||

| Mg | DRIsa 350*/300* | mg/day | 12.0/14.0 | 11.3/13.1 | 11.3/13.2 | 13.8/16.1 | 12.9/15.1 | 11.2/13.1 | 10.7/12.5 | 13.2/15.4 | ||

| Zn | DRIsa 11/8 | mg/day | 5.0/6.9 | 6.6/9.1 | 3.7/5.0 | 6.6/9.1 | 5.0/6.9 | 4.8/6.7 | 4.6/6.3 | 4.6/6.3 | ||

| Fe | DRIsa 11/7 | mg/day | 10.6/16.7 | 10.3/16.2 | 8.4/13.1 | 7.6/11.9 | 7.8/12.3 | 31.9/50.1 | 5.8/9.1 | 6.3/9.9 | ||

| Mn | DRIsa 2.3/1.8 | mg/day | 13.4/17.2 | 13.4/17.2 | 16.2/20.8 | 6.1/7.8 | 25.8/32.9 | 16.8/21.5 | 19.3/24.7 | 38.8/49.6 | ||

| Cu | DRIsa 1.6/1.3 | mg/day | 10.0/12.4 | 14.1/17.3 | 8.5/10.5 | 14.8/18.2 | 13.3/16.4 | 12/14.8 | 8.1/9.9 | 12.4/15.2 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).