Submitted:

04 July 2023

Posted:

05 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

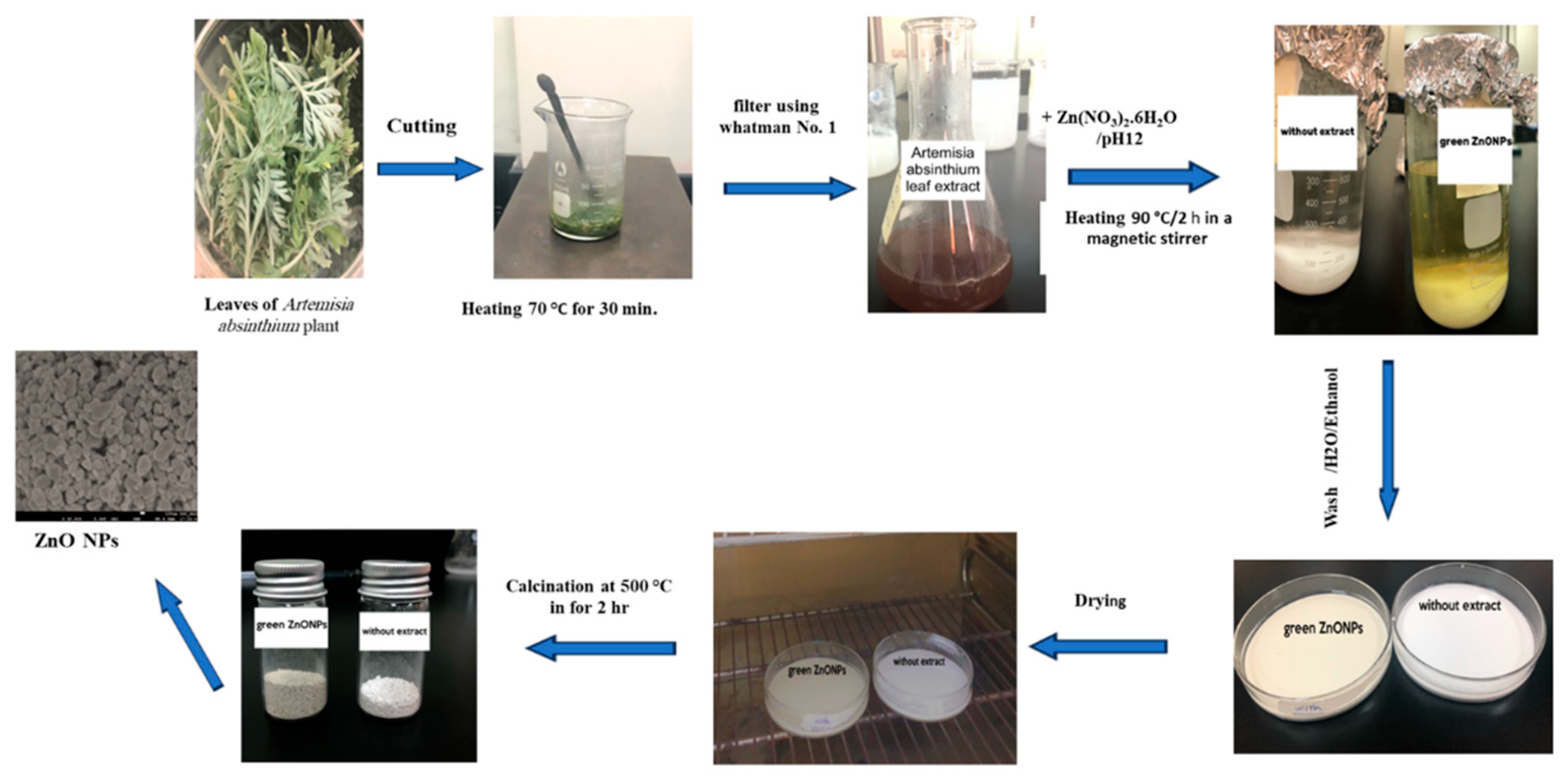

2.2.1. Plant Extract

2.2.2. Green Synthesis of ZnO NPs

2.3. Characterization Techniques

2.3.1. Characterization of Artemisia absinthium Extract

Flavonoids Test

Wagner’s Test

Frothing Test

Ferric Chloride Test

2.3.2. Characterization of ZnO NPs

XRD—Diffraction Analysis

SEM and EDX Analysis

FTIR Analysis

UV–Vis Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of A. absinthium Leaf Extract

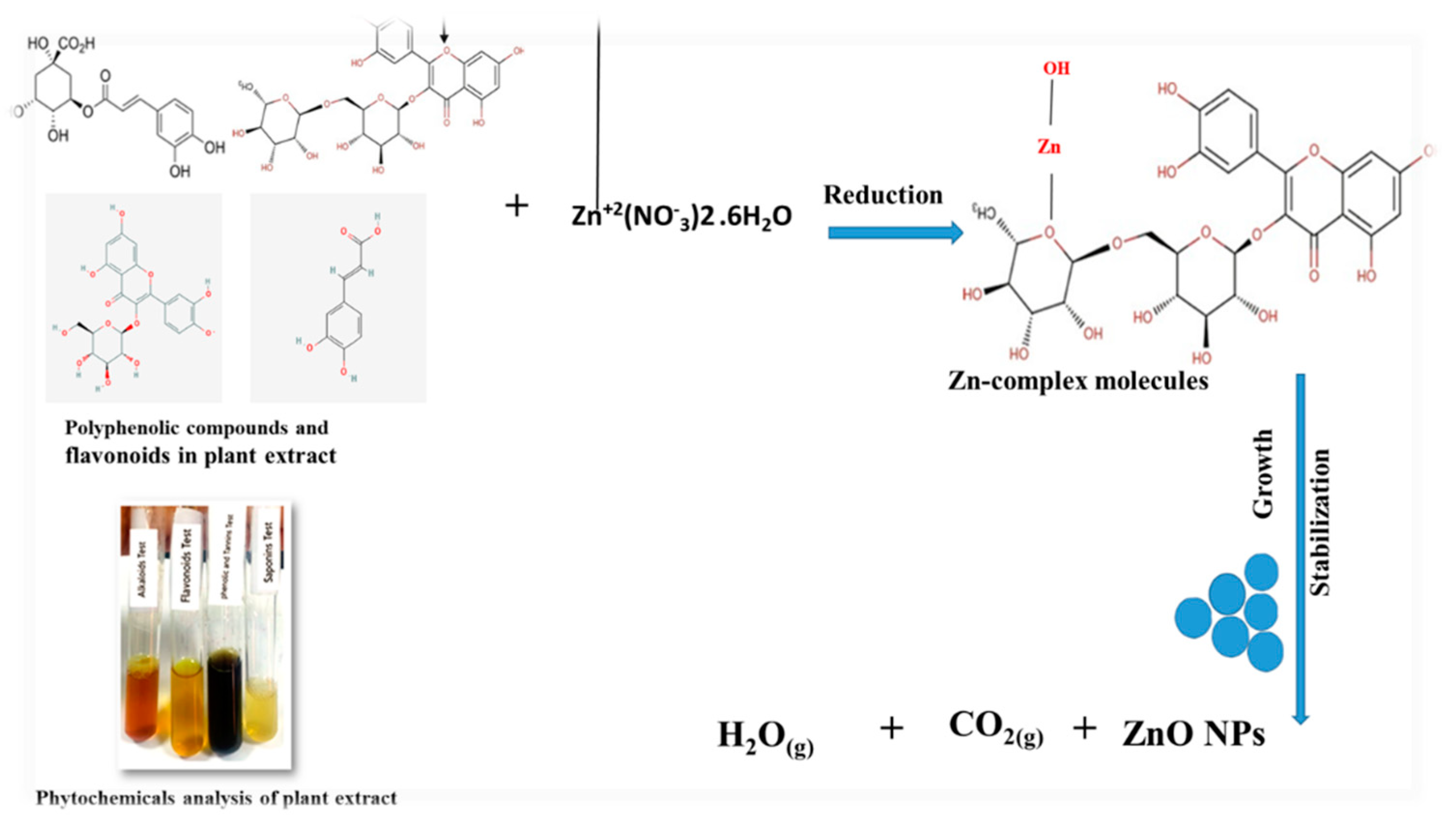

3.1.1. Identification of Active Ingredients

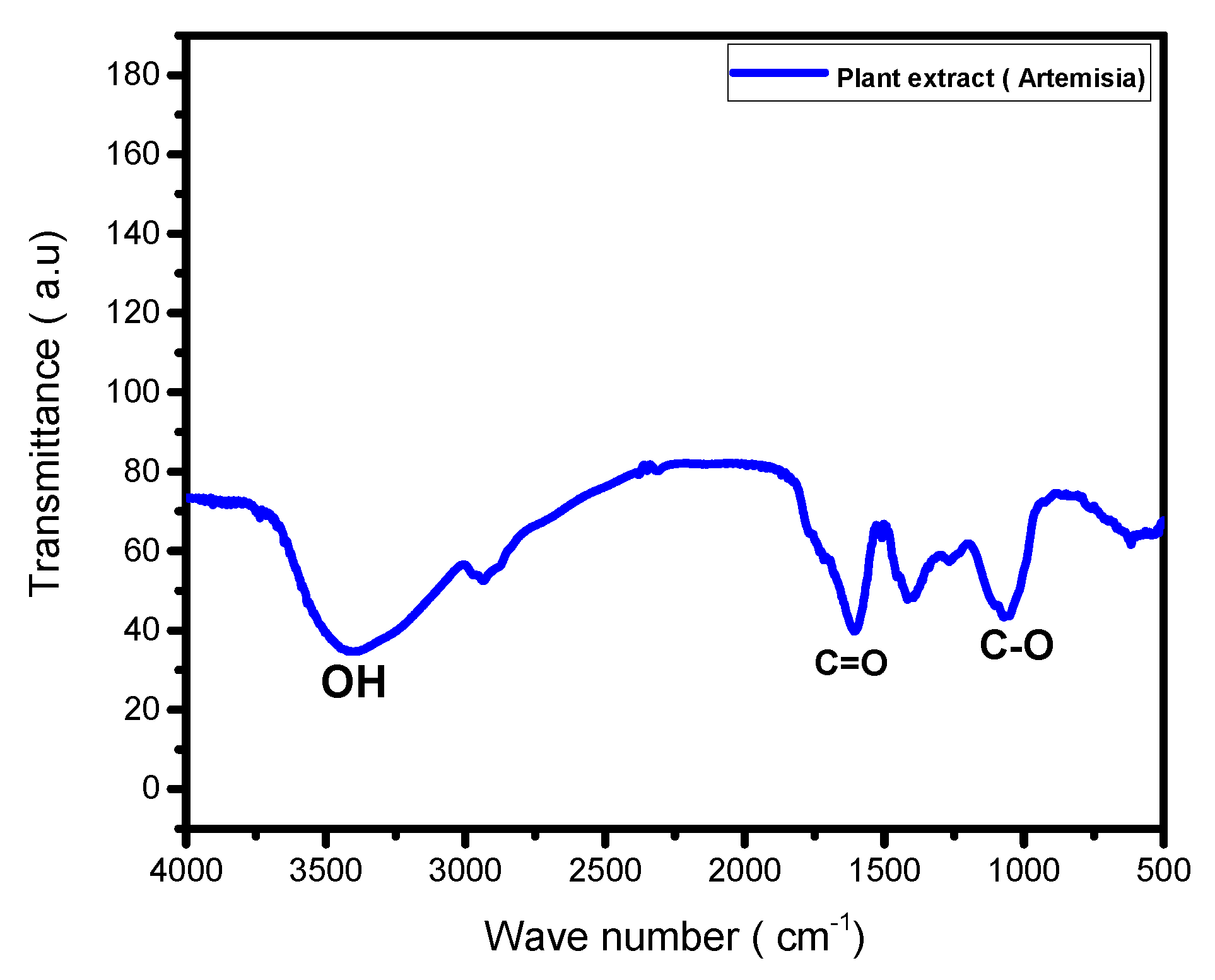

3.1.2. FTIR Analysis

3.2. Characterization of ZnO NPs

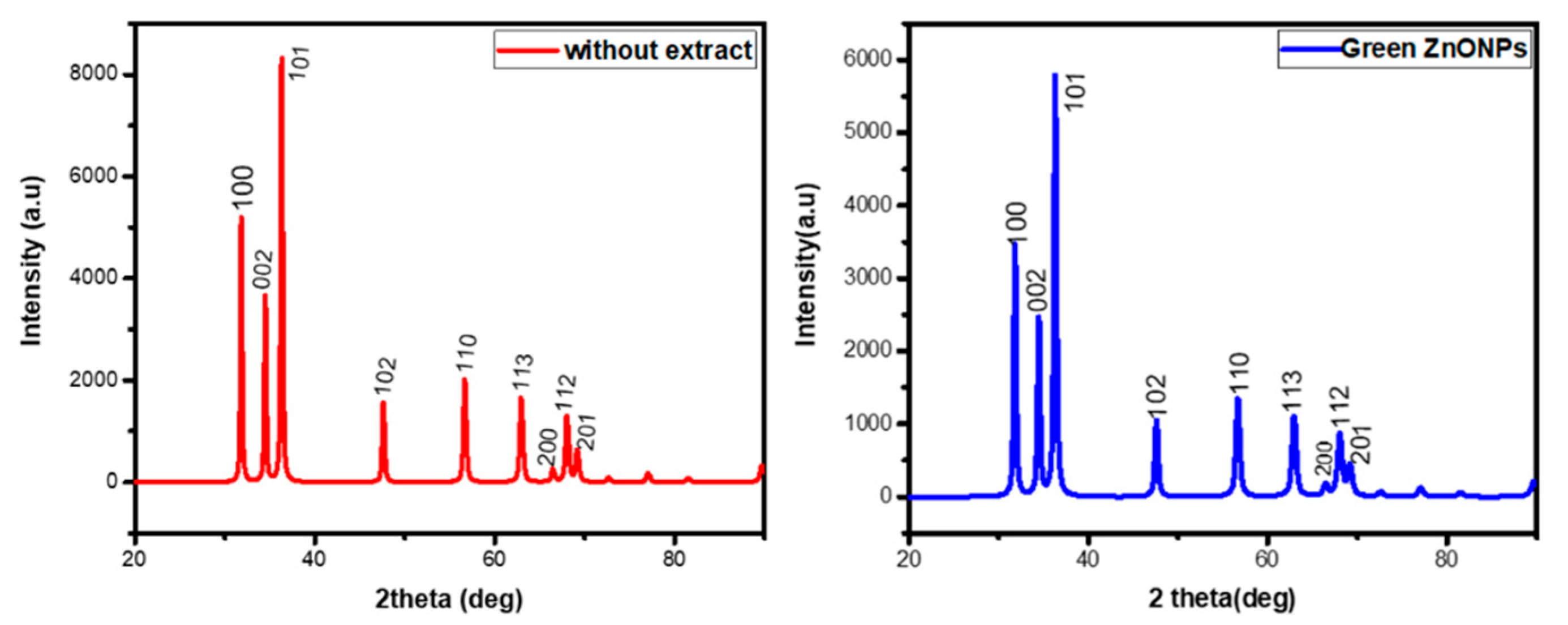

3.2.1. X-ray Diffraction

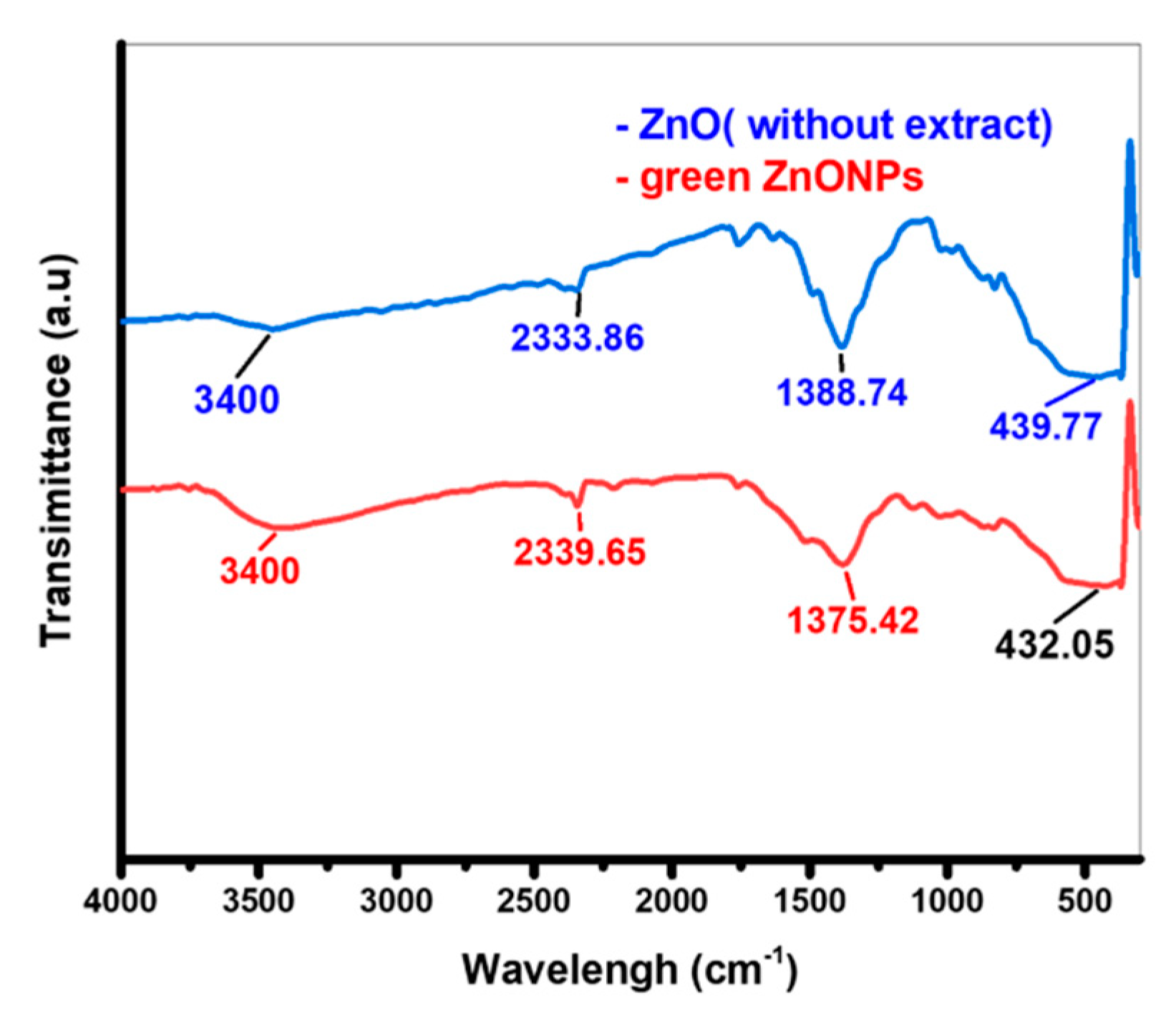

3.2.2. FTIR Analysis

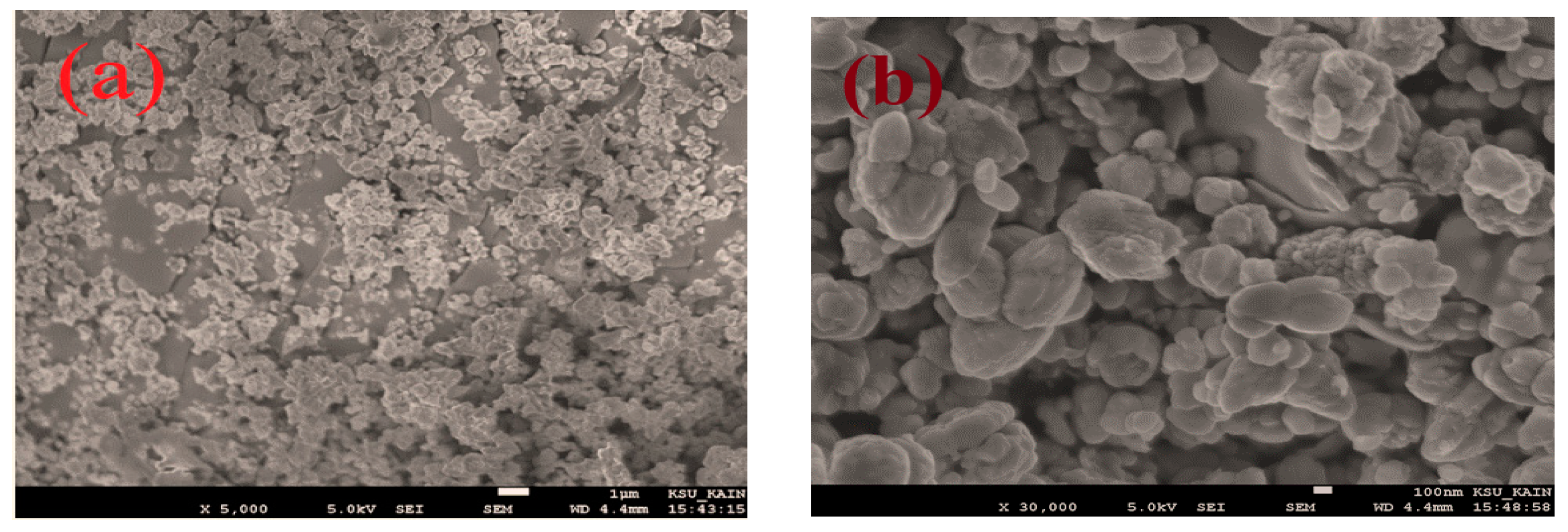

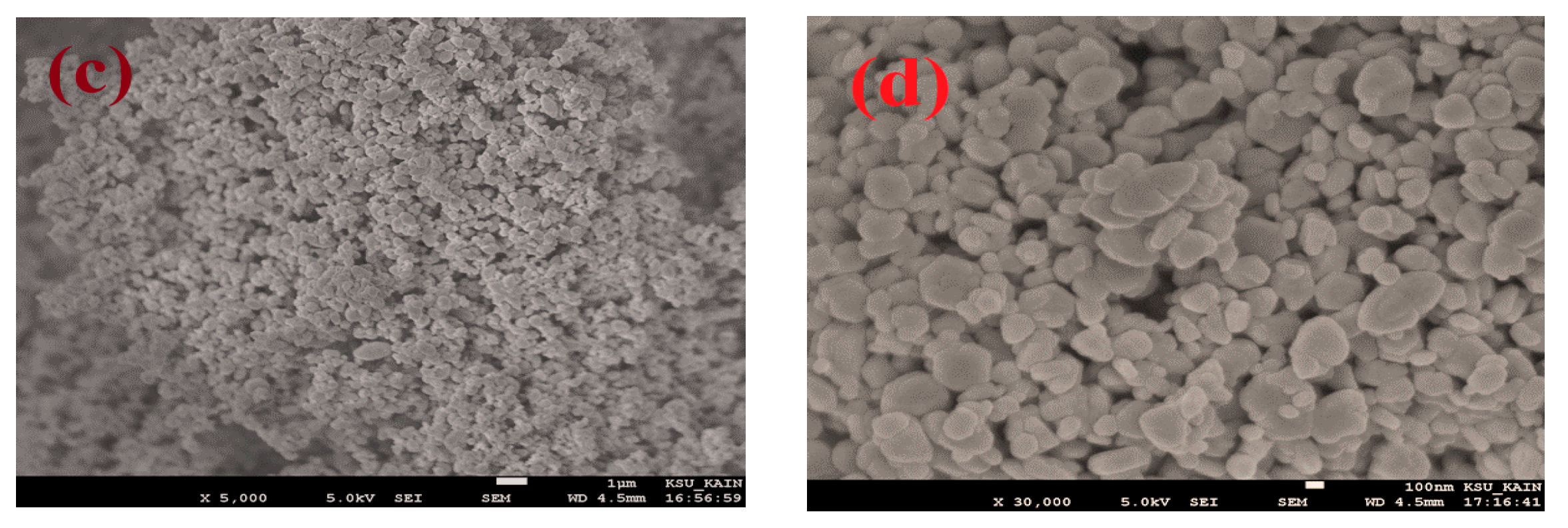

3.2.3. SEM Analysis

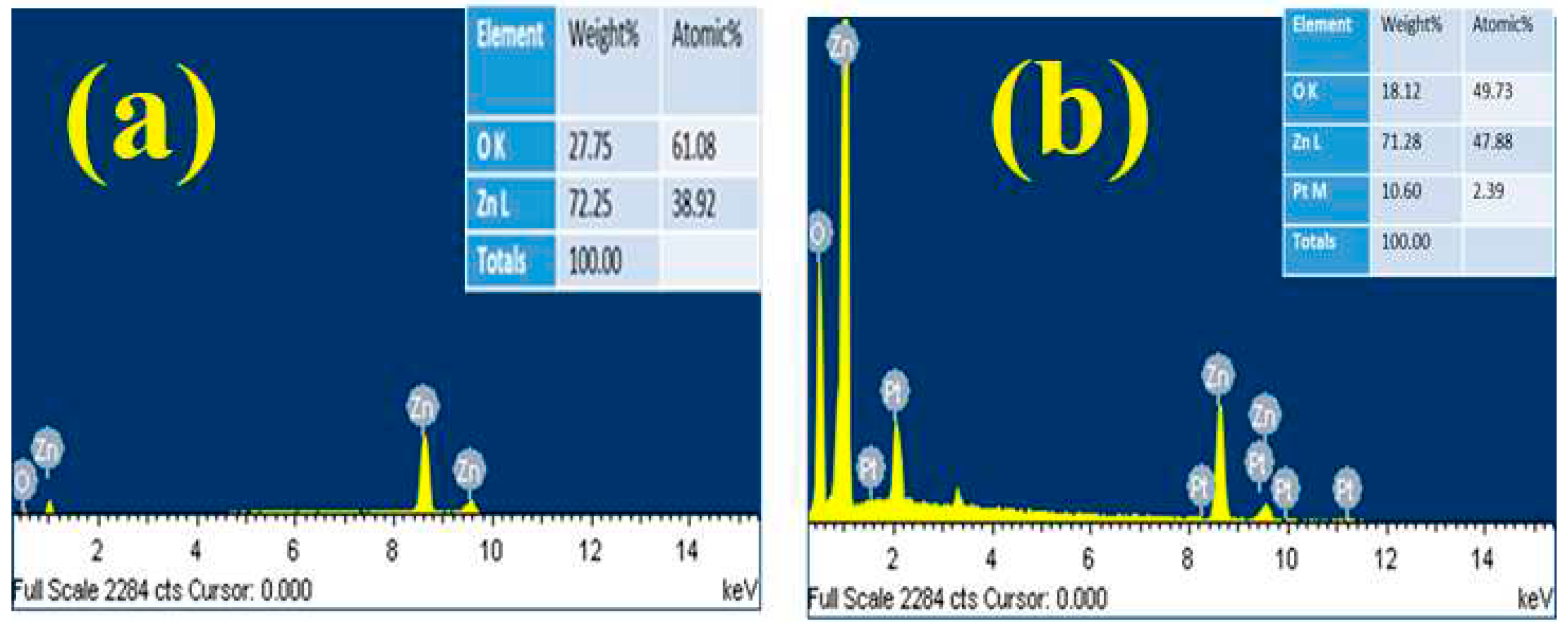

3.2.4. EDAX Analysis

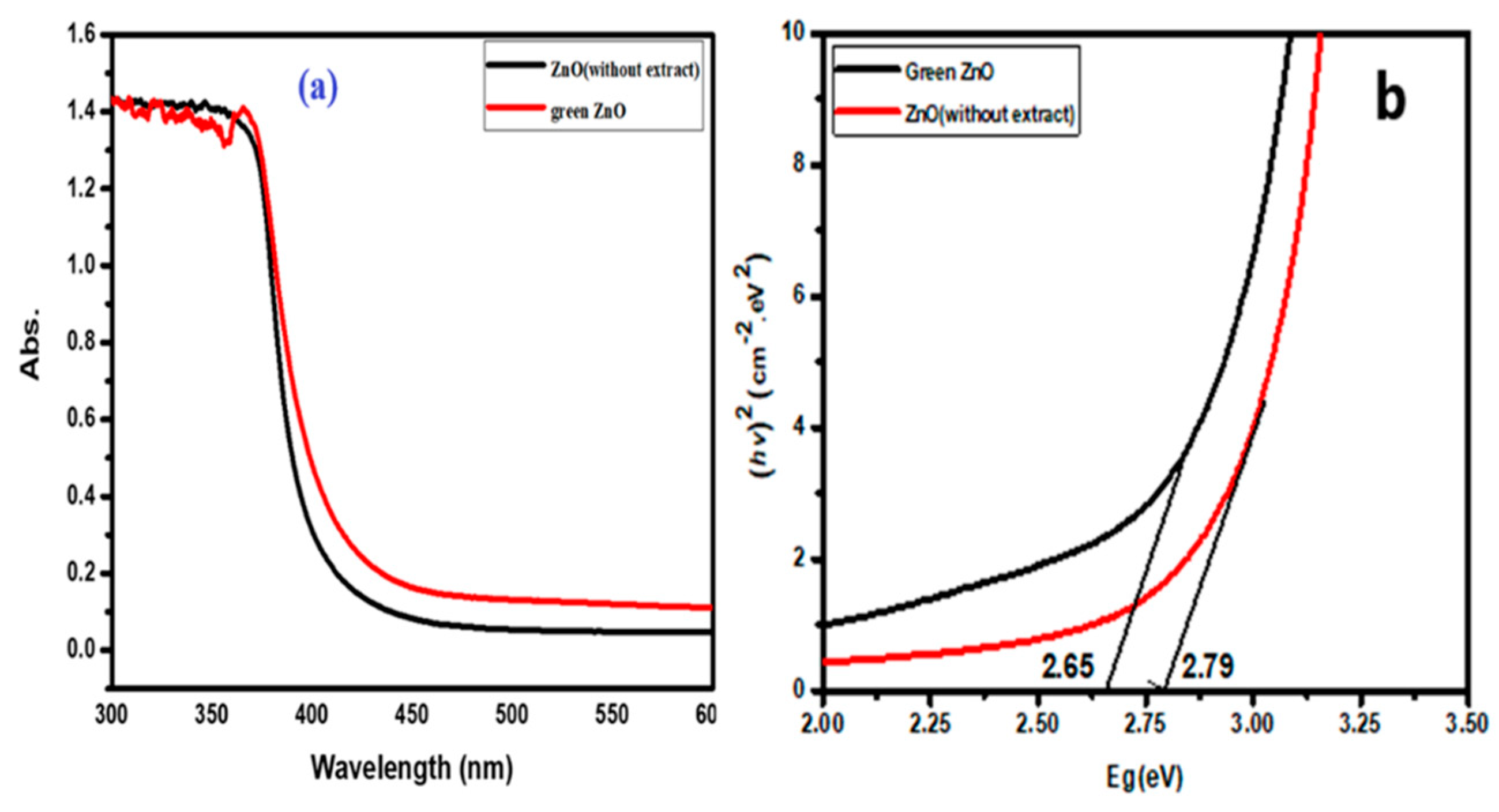

3.2.5. DRS Analysis

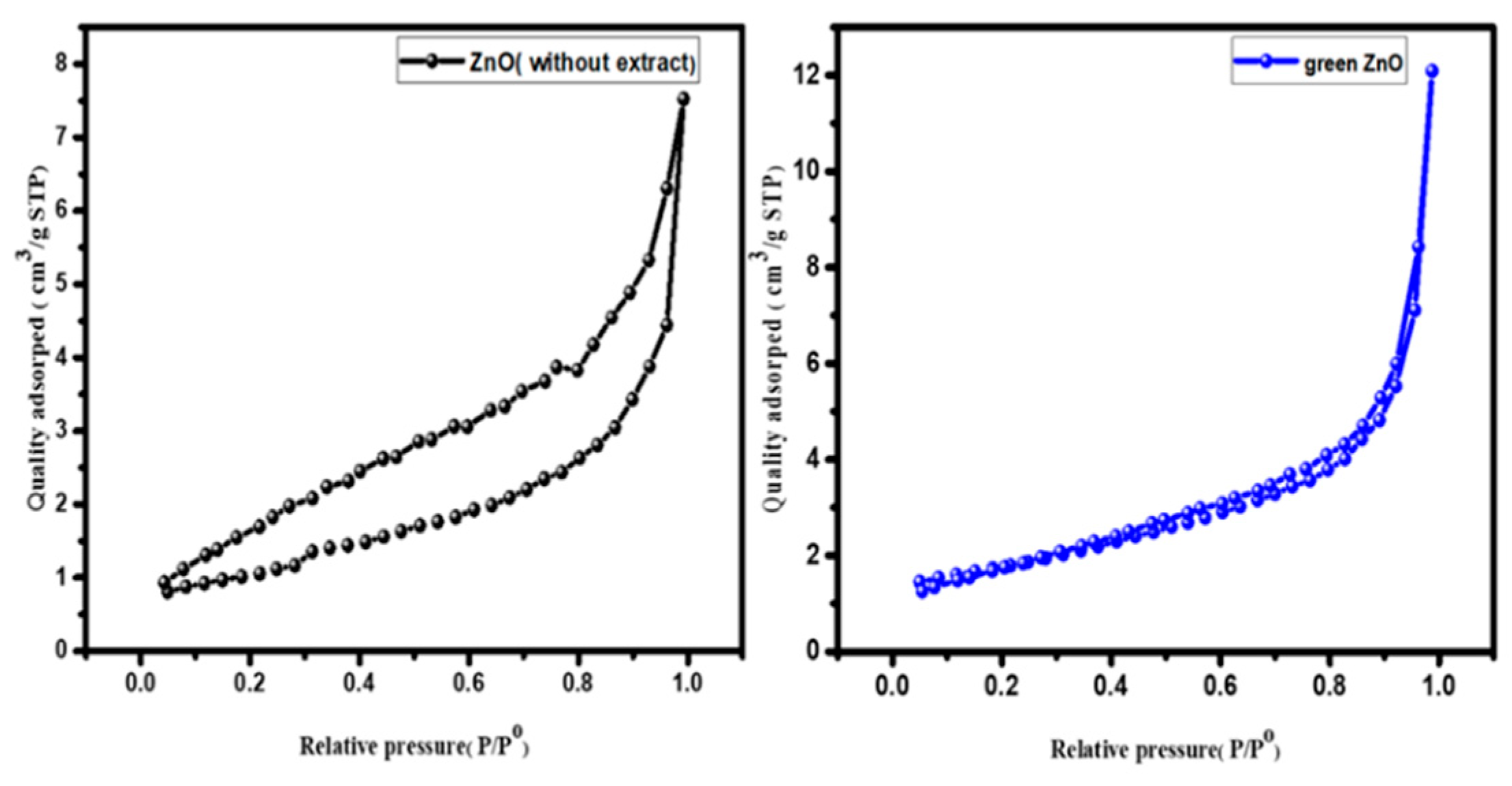

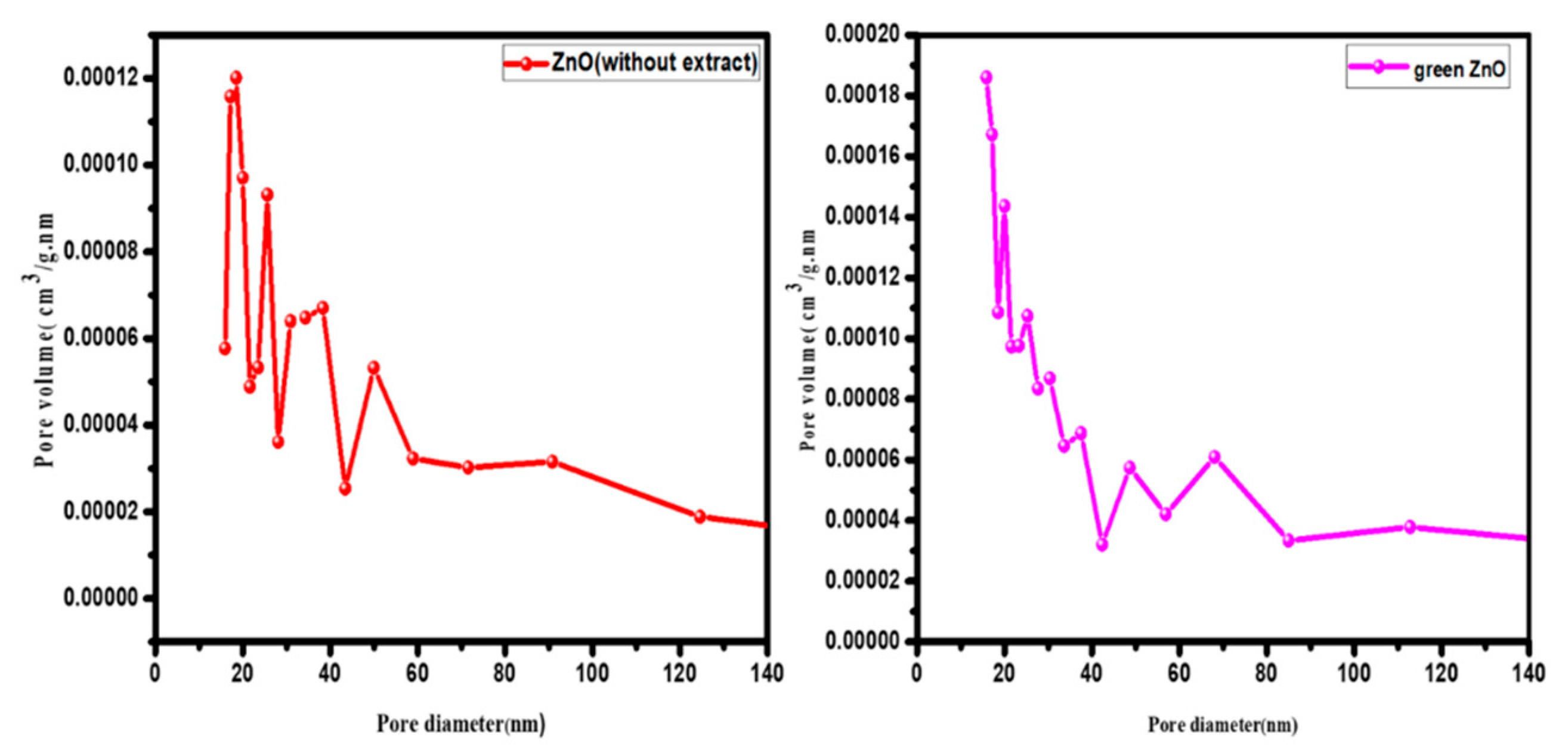

3.2.6. BET Determination

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rahman, F.; Majed Patwary, M.A.; Bakar Siddique, M.A.; Bashar, M.S.; Haque, M.A.; Akter, B.; Rashid, R.; Haque, M.A.; Royhan Uddin, A.K.M. Green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Cocos nucifera leaf extract: Characterization, antimicrobial, antioxidant and photocatalytic activity. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2022, 9, 220858. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.220858. [CrossRef]

- Abdelbaky, A.S.; El-mageed, T.A.A.; Babalghith, A.O.; Selim, S.; Mohamed, A.M.H.A. Green Synthesis and Characterization of ZnO Nanoparticles Using Pelargonium odoratissimum (L.) Aqueous Leaf Extract and Their Antioxidant, Antibacterial and Anti-inflammatory Activities. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1444. [CrossRef]

- Islam, F.; Shohag, S.; Uddin, J.; Islam, R.; Nafady, M.H. Exploring the Journey of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) toward Biomedical Applications. Materials 2022, 15, 2160. [CrossRef]

- Faisal, S.; Jan, H.; Shah, S.A.; Shah, S.; Khan, A.; Akbar, M.T.; Rizwan, M.; Jan, F.; Wajidullah; Akhtar, N.; et al. Green Synthesis of Zinc Oxide (ZnO) Nanoparticles Using Aqueous Fruit Extracts of Myristica fragrans: Their Characterizations and Biological and Environmental Applications. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 9709–9722. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.1c00310. [CrossRef]

- Karam, S.T.; Abdulrahman, A.F. Green Synthesis and Characterization of ZnO Nanoparticles by Using Thyme Plant Leaf Extract. Photonics 2022, 9, 594. [CrossRef]

- Sundrarajan, M.; Ambika, S.; Bharathi, K. Plant-extract mediated synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using Pongamia pinnata and their activity against pathogenic bacteria. Adv. Powder Technol. 2015, 26, 1294–1299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apt.2015.07.001. [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, A.; Marsudi, M.A.; Amal, M.I.; Ananda, M.B.; Stephanie, R.; Ardy, H.; Diguna, L.J. ZnO nanostructured materials for emerging solar cell applications. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 42838–42859. https://doi.org/10.1039/d0ra07689a. [CrossRef]

- Subhan, M.A.; Neogi, N.; Choudhury, K.P. Industrial Manufacturing Applications of Zinc Oxide Nanomaterials: A Comprehensive Study. Nanomanufacturing 2022, 2, 265–291. https://doi.org/10.3390/nanomanufacturing2040016. [CrossRef]

- Liewhiran, C.; Tamaekong, N.; Wisitsoraat, A.; Tuantranont, A.; Phanichphant, S. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical Ultra-sensitive H 2 sensors based on flame-spray-made Pd-loaded SnO 2 sensing films. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2013, 176, 893–905. [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Miranda, J.L.; Molina, G.A.; González-Reyna, M.A.; España-Sánchez, B.L.; Esparza, R.; Silva, R.; Estévez, M. Antibacterial and Anti-Inflammatory Properties of ZnO Nanoparticles Synthesized by a Green Method Using Sargassum Extracts. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1474. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24021474. [CrossRef]

- Djearamane, S.; Xiu, L.J.; Wong, L.S.; Rajamani, R.; Bharathi, D.; Kayarohanam, S.; De Cruz, A.E.; Tey, L.H.; Janakiraman, A.K.; Aminuzzaman, M.; et al. Antifungal Properties of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles on Candida albicans. Coatings 2022, 12, 1864. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings12121864. [CrossRef]

- Kumar Jangir, L.; Kumari, Y.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, M.; Awasthi, K. Investigation of luminescence and structural properties of ZnO nanoparticles, synthesized with different precursors. Mater. Chem. Front. 2017, 1, 1413–1421. https://doi.org/10.1039/c7qm00058h. [CrossRef]

- Pino, P.; Bosco, F.; Mollea, C.; Onida, B. Antimicrobial Nano-Zinc Oxide Biocomposites for Wound Healing Applications: A Review. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 970. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics15030970. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R. Polymer precursor method for the synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles: A Novel Approach. Research Square, 2023, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, S.; Lee, L.O.; Lem, C.; Ton-that, C.; Schleuning, M.; Ho, A.; Phillips, M.R. Correlative Study of Enhanced Excitonic Emission in ZnO Coated with Al Nanoparticles using Electron and Laser Excitation. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2553. [CrossRef]

- Bode, A.M.; Roh, E. Are FDA-approved sunscreen components effective in preventing solar UV-induced skin cancer? Cells 2020, 9, 1674. [CrossRef]

- Barcaui, C.B.; Gomes, E.E.; Lupi, O.; Marc, C.R. Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia. 2022, 97, 204 -222.

- Synthesis, N.; Harharah, H.N.; Elboughdiri, N.; Tahoon, M.A. Plant and Microbial Approaches as Green Methods for the Synthesis of Nanomaterials: Synthesis, Applications, and Future Perspectives. Molecules 2023, 28, 463. [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.; Fawcett, D.; Sharma, S.; Tripathy, S.K. Green Synthesis of Metallic Nanoparticles via Biological Entities. Materials 2015, 8, 7278–7308. [CrossRef]

- Meera, V.P.A.S.; Maria, C.G.A. Green synthesis of nanoparticles from biodegradable waste extracts and their applications : A critical review. Nanotechnol. Environ. Eng. 2022, 8,377-397. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41204‐022‐00276‐8. [CrossRef]

- Baig, N.; Kammakakam, I.; Falath, W. Nanomaterials: a review of synthesis methods, properties, recent progress, and challenges. Mater. Adv. 2021, 2, 1821–1871. https://doi.org/10.1039/d0ma00807a. [CrossRef]

- Rashid, I.M.; Salman, S.D.; Mohammed, A.K.; Mahdi, Y.S. Green Synthesis of Nickle Oxide Nanoparticles for Adsorption of Dyes. Sains Malays. 2022, 51, 533–546. https://doi.org/10.17576/jsm-2022-5102-17. [CrossRef]

- Bawazeer, S.; Rauf, A.; Uzair, S.; Shah, A.; Shawky, A.M.; Awthan, Y.S. Al Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Tropaeolum majus: Phytochemical screening and antibacterial studies. Green Process. Synth. 2021, 10, 85–94. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Fikadu, A.; Bachheti, A.; Husen, A. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences Biogenic fabrication of nanomaterials from flower-based chemical compounds, characterization and their various applications: A review. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 27, 2551–2562. [CrossRef]

- Adeyemi, J.O.; Oriola, A.O.; Onwudiwe, D.C. Plant Extracts Mediated Metal-Based Nanoparticles: Synthesis and Biological Applications. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 627. [CrossRef]

- Izwanie, N.; Basri, H.; Harun, Z. Heliyon Zinc oxide from aloe vera extract: Two-level factorial screening of biosynthesis parameters. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03156. [CrossRef]

- Ramzan, M.; Ayub, F.; Shah, A.A.; Naz, G.; Shah, A.N.; Malik, A.; Sardar, R.; Telesiński, A.; Kalaji, H.M.; Dessoky, E.S.; et al. Synergistic Effect of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles and Moringa oleifera Leaf Extract Alleviates Cadmium Toxicity in Linum usitatissimum: Antioxidants and Physiochemical Studies. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 900347. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.900347. [CrossRef]

- Stan, M.; Popa, A.; Toloman, D.; Silipas, T.D.; Vodnar, D.C. Antibacterial and antioxidant activities of ZnO nanoparticles synthesized using extracts of Allium sativum, Rosmarinus officinalis and Ocimum basilicum. Acta Metall. Sin. Engl. Lett. 2016, 29, 228–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40195-016-0380-7. [CrossRef]

- Noukelag, S.K.; Mohamed, H.E.A.; Moussaa, B.; Razanamahandry, L.C.; Ntwampe, S.K.O.; Arendse, C.J.; Maaza, M. Investigation of structural and optical properties of biosynthesized Zincite (ZnO) nanoparticles (NPs) via an aqueous extract of Rosmarinus officinalis (rosemary) leaves. MRS Adv. 2020, 5, 2349–2358. https://doi.org/10.1557/adv.2020.220. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Y.; Raouf Malik, A.; Iqbal, T.; Hammad Aziz, M.; Ahmed, F.; Abolaban, F.A.; Mansoor Ali, S.; Ullah, H. Green synthesis of ZnO and Ag-doped ZnO nanoparticles using Azadirachta indica leaves: Characterization and their potential antibacterial, antidiabetic, and wound-healing activities. Mater. Lett. 2021, 305, 130671. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2021.130671. [CrossRef]

- US, P.; Pujar, A.; Yadawe, M. Study on Green Synthesis, Characterization and Anticancer Activity of Thorium Nanoparticles Using Tomato (Lycopersicon Esculentum) Extract. IOSR J. Appl. Chem. 2018, 11, 25–29. https://doi.org/10.9790/5736-1107032529. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Miceli, F.A.; Oliva-Llaven, M.Á.; Luján-Hidalgo, M.C.; Velázquez-Gamboa, M.C.; González-Mendoza, D.; Sánchez-Roque, Y. Zinc Oxide Phytonanoparticles’ Effects on Yield and Mineral Contents in Fruits of Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L. cv. Cherry) under Field Conditions. Sci. World J. 2021, 2021, 5561930. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5561930. [CrossRef]

- Bhat, R.R.; Rehman, M.U.; Shabir, A.; Mir, M.; Ahmad, A.; Khan, R.; Masoodi, M.H.; Madkhali, H.; Ganaie, M.A. Chemical Composition and Biological Uses of Artemisia absinthium (Wormwood). In Plant and Human Health; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; Volume 3. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04408-4_3. [CrossRef]

- Allemailem, K.S. Aqueous Extract of Artemisia annua Shows In Vitro Antimicrobial Activity and an In Vivo Chemopreventive Effect in a Small-Cell Lung Cancer Model. Plants 2022, 11, 3341. [CrossRef]

- Monirian, F.; Abedi, R.; Balmeh, N.; Mahmoudi, S.; Mirzaei, F. In-vitro antibacterial effects of Artemisia extracts on clinical strains of P. aeruginosa, S. pyogenes, and oral bacteria. Jorjani Biomed. J. 2020, 8, 35–43. https://doi.org/10.29252/jorjanibiomedj.8.3.35. [CrossRef]

- Ikram, M.A.M.; Ul, M.I.A.; Avais, H.M. Green synthesis and evaluation of n-Type ZnO nanoparticles doped with plant extract for use as alternative antibacterials. Appl. Nanosci. 2020, 10, 3787–3803. [CrossRef]

- Vera, J.; Herrera, W.; Hermosilla, E.; Díaz, M.; Parada, J.; Seabra, A.B.; Tortella, G.; Pesenti, H.; Ciudad, G.; Rubilar, O. Antioxidant Activity as an Indicator of the Efficiency of Plant Extract-Mediated Synthesis of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 784. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox12040784. [CrossRef]

- Jayachandran, A.; Aswathy, T.R.; Nair, A.S. Green synthesis and characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Cayratia pedata leaf extract. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2021, 26, 100995. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, V.; Gusain, D.; Sharma, Y.C. Synthesis, characterization and application of zinc oxide nanoparticles (n-ZnO). Ceram. Int. 2013, 39, 9803–9808. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2013.04.110. [CrossRef]

- Hajiashra, S.; Motakef, N. Heliyon Preparation and evaluation of ZnO nanoparticles by thermal decomposition of MOF-5. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02152. [CrossRef]

- Demissie, M.G.; Sabir, F.K.; Edossa, G.D.; Gonfa, B.A. Synthesis of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Using Leaf Extract of Lippia adoensis (Koseret) and Evaluation of Its Antibacterial Activity. J. Chem. 2020, 2020, 7459042. [CrossRef]

- Faisal, M.; Bahadar, S.; Rahman, M.M.; Jamal, A.; Abdullah, M.M. Applied Surface Science Fabrication of ZnO nanoparticles based sensitive methanol sensor and efficient photocatalyst. Appl. Nanosci. 2012, 258, 7515–7522. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.S.; Venkateswarlu, P.; Rao, V.R.; Rao, G.N. Synthesis, characterization and optical properties of zinc oxide nanoparticles. Int. Nano Lett. 2013, 3, 30. [CrossRef]

- Suresh, D.; Nethravathi, P.C.; Rajanaika, H. Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing Green synthesis of multifunctional zinc oxide (ZnO) nanoparticles using Cassia fistula plant extract and their photodegradative , antioxidant and antibacterial activities. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2015, 31, 446–454. [CrossRef]

- Taha, K.K.; Zoman, M.; Al Outeibi, M.; Al Modwi, S.A.A.; Bagabas, A.A. Green and sonogreen synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles for the photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue in water. Nanotechnol. Environ. Eng. 2019, 4, 10. [CrossRef]

| No. | Active Components | Test | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Phenolics | FeCl3 | + |

| 2 | Alkaloids | Wagner’s reagent | + |

| 3 | Saponins | foam test | + |

| 4 | Flavonoids | alkaline test | + |

| No. of Peaks | Indices | Location (2θ) | FWHM (2θ) | Size (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100 | 31.8405 | 0.25611 | 32.25 |

| 2 | 002 | 34.4993 | 0.27379 | 30.38 |

| 3 | 101 | 36.3291 | 0.28256 | 29.59 |

| 4 | 102 | 47.6240 | 0.34103 | 25.46 |

| 5 | 110 | 56.6831 | 0.3981 | 22.67 |

| 6 | 113 | 62.9548 | 0.43834 | 21.25 |

| 7 | 200 | 66.4807 | 0.48187 | 19.71 |

| 8 | 112 | 68.0481 | 0.48285 | 19.85 |

| 9 | 201 | 69.1720 | 0.52439 | 18.40 |

| Average size | 24.39 |

| No. of Peaks | Indices | Location (2θ) | FWHM (2θ) | Size (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100 | 31.8216 | 0.34989 | 23.61 |

| 2 | 002 | 34.47333 | 0.37528 | 22.16 |

| 3 | 101 | 36.30893 | 0.37771 | 22.13 |

| 4 | 102 | 47.60253 | 0.4578 | 18.96 |

| 5 | 110 | 56.67089 | 0.54533 | 16.55 |

| 6 | 113 | 62.93347 | 0.60605 | 15.36 |

| 7 | 200 | 66.56221 | 0.66134 | 14.37 |

| 8 | 112 | 68.03501 | 0.69904 | 13.71 |

| 9 | 201 | 69.15222 | 0.43528 | 22.16 |

| Average size | 18.77 |

| Samples | BET (m2/g) |

Pore Volume (cm3/g) |

Average Pore Diameter (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZnO (without extract) | 4.003 | 0.011 | 18.455 |

| Green ZnO | 6.032 | 0.017 | 15.876 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions, or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).