1. Introduction

In recent decades, there has been an increasing focus on the environment and global warming due to the substantial greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) released into the atmosphere because of anthropogenic activities. These activities include the ongoing urbanization processes in developing countries and the global expansion of the building construction sector [

1] which disrupt natural balances [

2]. The European Union is a member of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) adopted at the Rio Earth Summit in 1992 which is the principal international agreement on climate policy action whereby international community recognizes the need “to act collectively to protect people and the environment and to contain greenhouse gas emissions”. In 1997 the UNFCCC subscribes the Kyoto Protocol which introduces the first ever legally binding emission reduction targets for developed countries. As a global issue, climate change requires countries worldwide to work collaboratively to limit the global warming: with the Paris Agreement adopted during the meeting of the parties to the UNFCCC in 2015 governments agreed “to keep the increase in global average temperature to well below 2°C above the pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit it to 1.5 °C”. [

3]. For these reasons the European Union Green Deal has set the goal to cut emissions by at least 55% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels and to reach the climate neutrality by 2050 [

4].

The building and construction sector has a significant impact on the phenomenon of the climate change: it represents one of the main causes of pollution due to the excessive emissions released into the environment as a result of the processes of heating and cooling systems in buildings. In fact, almost the 40% of the energy consumption and related carbon emissions [

5], about the 50% of resources use such as steel, cement, and glass and 38% of waste produced in the European Union derives from the construction, renovation and living in of the buildings [

6]. In particular, the main energy consumption in EU households is related for the 77,9% for homes space and water heating, the other 14,5% for lighting and appliances and the 0,4% for space cooling [

7]. According to the EU Building Stock Observatory (BSO), the building stock is aging and is composed by the 75% of buildings built before 1990 with a renewal rate around 1,2% [

8].

The EU Building Stock Observatory (BSO) is a web tool that monitors the energy performance of buildings across Europe. It was established in 2016 and aims to provide a better understanding of the energy performance of the building sector through reliable, consistent and comparable data [

9].

In particular, in Italy the building stock is heterogeneous and quite dated and, according to the ISTAT (National Institute of Statistics) data related to the 15th general population and housing census till 9 October 2011, of the 2.740.018 residential buildings, only the 14% was constructed after 1990 (379.190 buildings), the 53% between 1946 and 1990 (1.444.160), the 12% between 1919 and 1945 (328.988) and the 21% before 1919 (587.680): it means that the enactment of legislation that requires to pay an increasing attention on the rational use of energy and to the thermal insulation of buildings starts with the emanation of the Law n° 10 of 1991 named “Regulations for the implementation of the National Energy Plan for the rational energy use, energy saving and development of renewable energy sources”

(“Norme per l’attuazione del Piano Energetico Nazionale in materia di uso razionale dell’energia, di risparmio energetico e sviluppo di fonti rinnovabili di energia”) and it does not involve the 86% of the Italian building stock. For this reason, a deep renovation is necessary [

10]. It is clear that European and Italian construction industry needs to be decarbonized, so in this order new sustainable strategies have to be developed: the effective tool to implement this kind of policy and to try to reach the goals of climate neutrality and avoid the dependence on energy imports is the energy efficiency and energy renovation of the building stock such as the rational use of energy during all the construction phases and also the inclusion of systems powered by Renewable Energy Sources (RES) [

8]. The energy efficiency is defined as the proportion between performance and energy input, in other words it represents the ratio of what is produced, and the energy used for its purpose. Greater energy efficiency and energy saving can be achieved both through the application of simple and complex technologies, components, and systems and through a more conscious and responsible end-user behavior: the energy efficiency has the objective of primary energy saving, CO2 emission reductions and the consequent reduction of energy costs. It appears necessary to promote the transformation of existing buildings into high-performance energy constructions through implementations of various kinds of interventions such as on the building envelope of roofs, walls, transparent closures, on lighting systems upgrading, on thermal energy production and distribution systems or on the installation of energy production systems based on renewables [

11].

Another significant aspect concerns the topic of Nearly Zero Energy Buildings (NZEB): it is defined as a building that has extremely high energy performance in terms of water supply, lighting, and ventilation [

12] and very low or almost zero energy needs covered from renewable sources, concept introduced with the European Directive n° 31/2010 [

13]. Since 2021, all new buildings or those undergoing major first-level renovation must satisfy the technical and performance requirements imposed by Appendix 1 of Ministerial Decree 26/6/2015 for near-zero energy buildings (nZEB). At the Italian scale, the nZEB minimum requirements include, in addition to the overall limit on energy consumption, prescriptions on thermal performance indices to be compared with the reference building, the global average coefficient of heat transfer by transmission, the summer equivalent solar area per unit of useful surface area, and the efficiencies of winter and summer air conditioning and domestic hot water production systems [

14].

On December 2021, the European Commission proposed a revision of the “Energy Performance of Buildings Directive—EPDB”, as part of the “fit for 55” package, to achieve a minimum 55 percent reduction in the EU’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2030, as required by the 2021 European Climate Act [

15]. This revision of the EPBD sets out how the EU can achieve a zero-emission and fully decarbonized building stock by 2050, in particular by increasing the rate of renovation for the worst-performing buildings in each EU member state. The European Commission’s proposal requires all new buildings in the EU to be zero-emission from 2030 (by 2027 for all new public buildings). To ensure more harmonized standards among member states, EU-wide minimum energy performance requirements will be established. Residential buildings should achieve Class E by 2030 and Class D by 2033.

The issue of energy efficiency of the national building stock is particularly relevant because 86 % of existing buildings predates the enactment of any energy laws and regulations, making it imperative to apply the energy efficiency interventions. Numerous research studies have focused on the development of guidelines for energy efficiency improvements in the national and international building stock, based on a analysis of typological, morphological, and geographical characteristics of buildings. Various aspects have been examined, including the thermal transmittance of transparent and opaque surfaces, the location within a specific climatic zone, the construction era, orientation, and the type of building elements. Among the different research investigations that aim to define methodologies for nationwide energy retrofit actions, one notable project is TABULA [

16]. This project outlines potential measures for energy savings and the reduction of CO2 emissions deriving from buildings. However, the project does not delve into the analysis of the costs associated with these interventions or the aspect related to energy class jump.

In this article, the authors propose a support decision tool to immediately identify the combination of energy efficiency solutions for multi-apartment residential buildings constructed between 1976 and 1990, that ensures the achievement of the European EPBD directive targets.

The tool also performs an analysis of the costs incurred and the benefits obtained from these interventions in terms of the energy class improvement for every climatic Italian zone. It can be extended to the international condominium building sector, not only national.

2. Materials and Methods

With a view to formulating technological solutions aimed at promoting Deep Renovation interventions in the housing sector of Italian building heritage, as well as internationally, the imperative to achieve the class advancement goals by 2030 and 2033 paves the way for the rehabilitation of the existing built environment based on sustainability principles and the utilization of renewable energy solutions. It appears highly practical to conceptualize an integrated decision support tool, rooted in a methodological procedure, that defines standardized interventions to be applied in the context of a specific existing building structure within the building heritage, considering its current state.

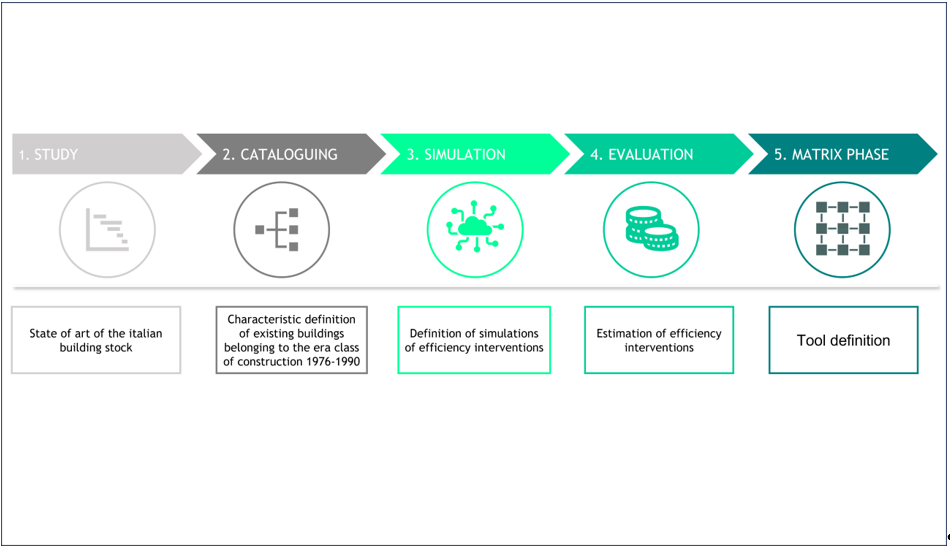

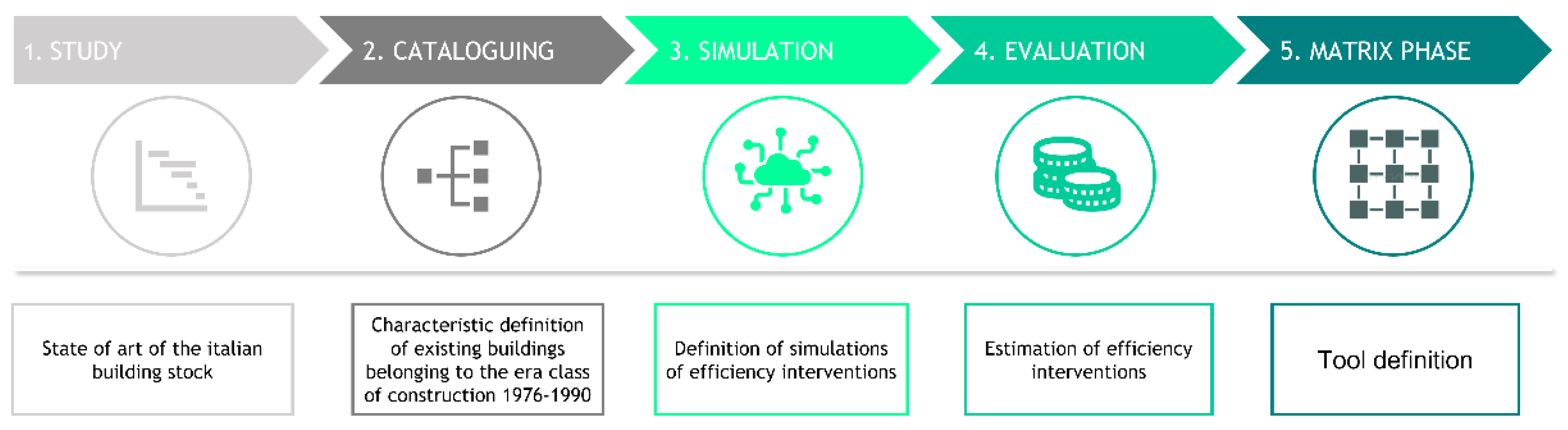

The methodology developed to obtain the tool for pre-calculated identification of energy efficiency solutions for existing buildings is based on 5 steps:

1st step: Italian residential building stock state of art study.

2nd step: Characterization and cataloging of existing buildings pertaining to the construction era class of 1976-1990.

3rd step: Definition of simulations of energy efficiency interventions.

4th step: Economic estimation of energy efficiency interventions.

5th step: Dynamic Matrix elaboration

An outline of the methodology developed to obtain a tool for the identification of the efficiency solution for the existing multi-apartment residential buildings, is shown in

Figure 1.

2.1. Italian Residential Building Stock State of Art Study

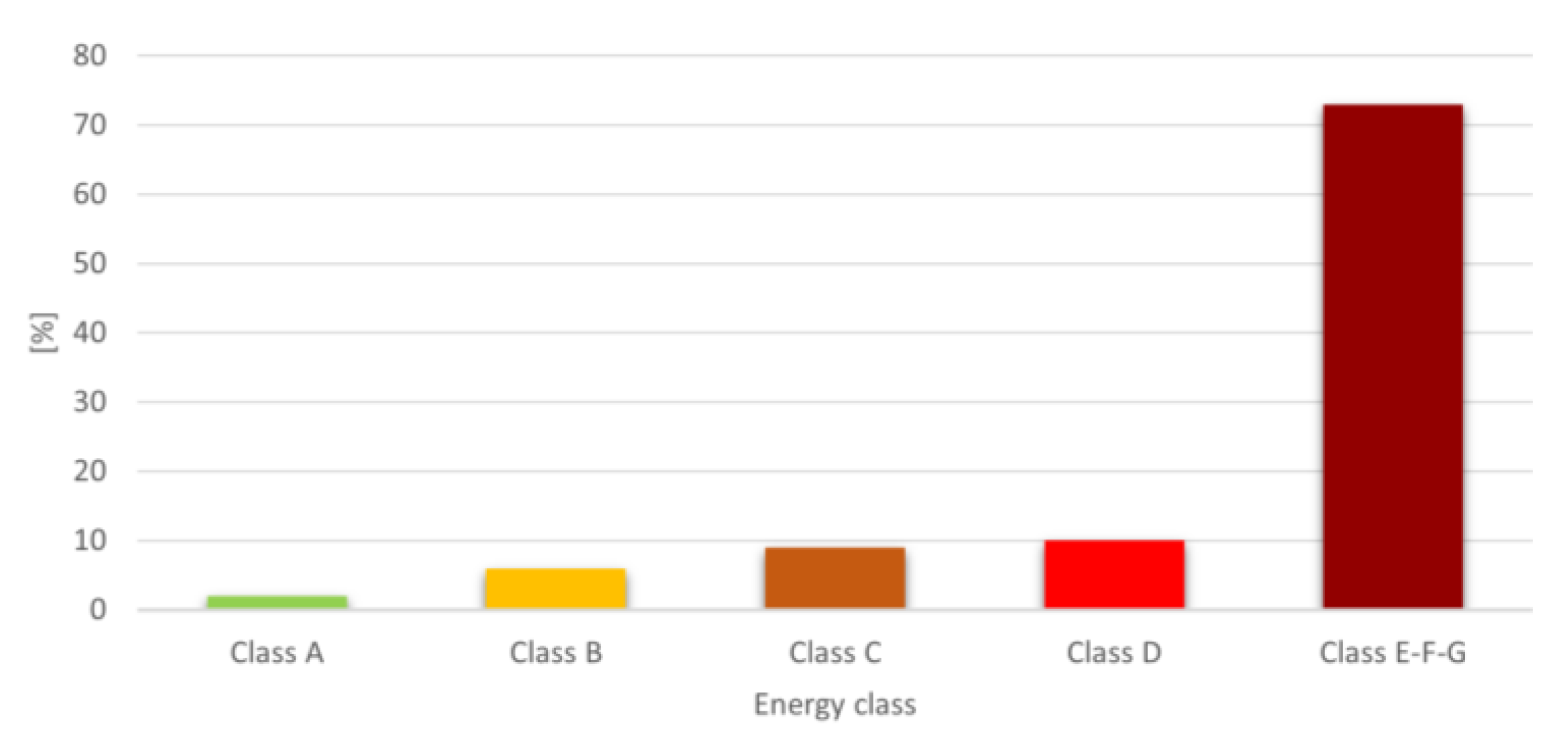

Analyzing the diagram of residences classified by class energy rating in different countries, it shows that Italy ranks on the third place with more than 70% of the buildings characterized by low energy performance and with an energy class higher than D resulting among the worst values (

Figure 2) [

17].

The national real estate stock is predominantly composed of buildings falling into energy classes F and G, accounting for 25% and 37.3% respectively, according to the Energy Performance Certificates Information System—SIAPE during the period 2016-2019, based on ENEA’s calculations [

18].

Fortunately, an increase in nZEB is occurring in all regions of Italy, the number of which amounted to approximately 1,400 buildings in 2018, mostly new construction (90%) and residential use (85%), as indicated by the nZEB Observatory. Non-residential nZEB buildings thus show an increasing trend, thanks in part to the incentive policies for public buildings that are currently in use [

19].

According to ISTAT data, of the 14,515,795 units of the Italian residential building stock, more than half of the residential buildings, which is about 60 percent, were built from the post-World War II period until the 1990s [

19]. As described before, in Italy of the 2.740.018 residential buildings the 53% was constructed between 1946 and 1990 (1.444.160). The construction-era class from 1976 to 1990 was found to be the most prevalent in Italy, so the research will focus on this specific reporting period.

2.2. Characterization and Cataloging of Existing Buildings Pertaining to the Construction Era Class of 1976–1990

The first step of the methodological procedure consists on the determination of those parameters aimed at the classification of the national residential building stock as extensively explored within the bibliography of the research [

20]: an elaborated preliminary classification of the building by parameters of reference—climatic zone, class of era of construction, building type (“Abacus of building envelope types: stratigraphy and characteristics”), building type, characteristics of the building envelope—is the first step towards a further correct formulation of the minimum interventions to be submitted on building structures belonging to a given era of construction and from certain defined typological, constructive and energy features in order to guarantee its minimum double energy class jump in its sustainable renovation of the building envelope and system.

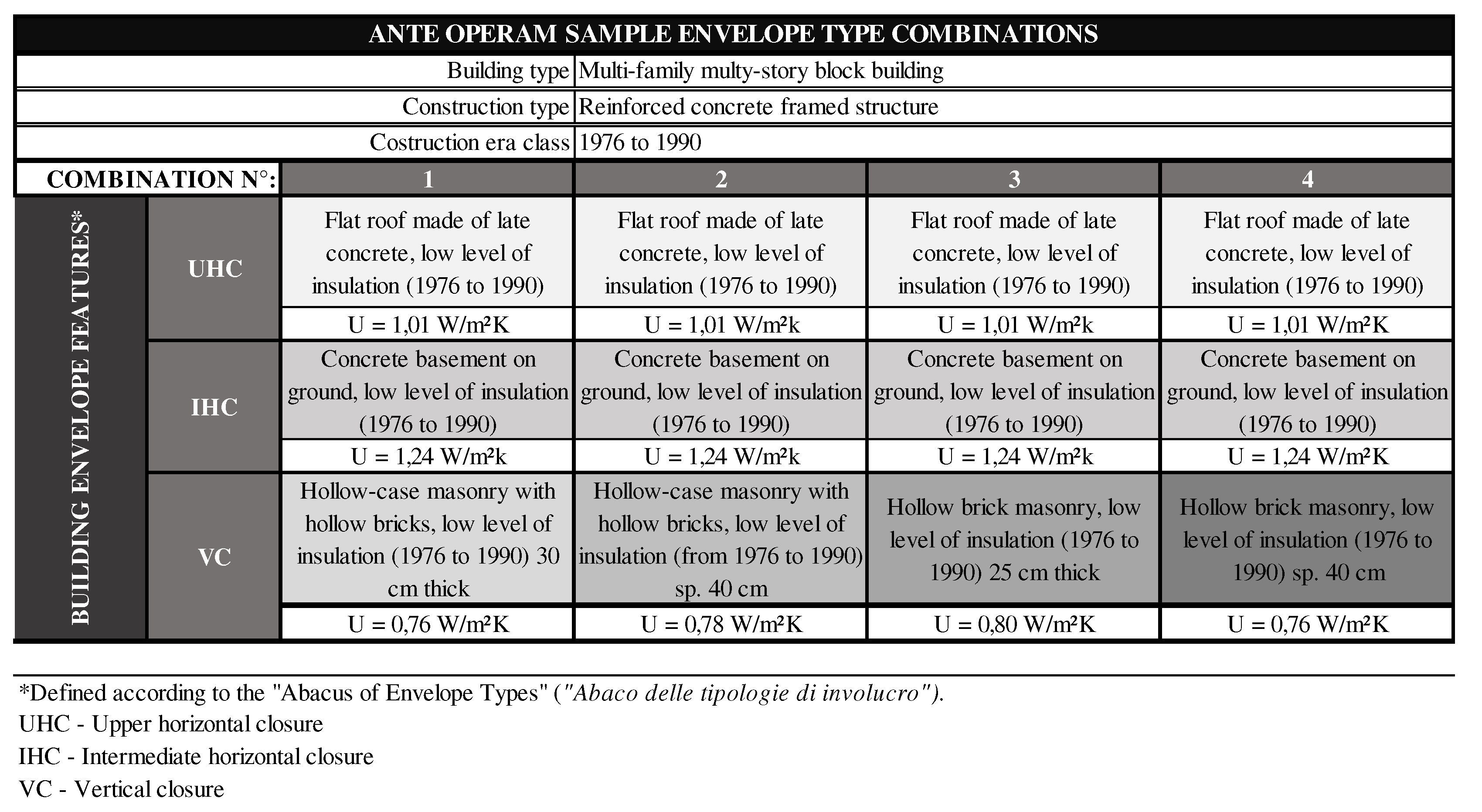

The simulations are being conducted on the Italian territory climate zones ranging from A to F. It is worth underlining that on climate zone A only 0.04 % of the Italian building stock is built. Furthermore, always for the following zone, the values of the minimum transmittances to be respected for the insulation of transparent and opaque dispersing surfaces turn out to be equivalent to the values for buildings in climate zone B [

20]: this means that the subsequent combinations of interventions will present the same technical specifications. In order to formulate a support decision tool to select the energy efficiency of the building, the characteristics of the building envelope are standardized, and, for this reason, they are deduced from the “Abacus of Building Envelope Types” [

20]: for the following sample, four different combinations are identified derived from the characteristics of the building envelope encountered in the era of construction currently analyzed for each of which the energy class of the state of the art (Ante Operam) is extrapolated. The Ante Operam combinations focus on the characteristics of the dispersing surfaces—bordering the exterior—and are the following: top horizontal closure, bottom horizontal closure and opaque vertical closure.

Figure 3.

Combinations of the opaque envelope types in the Ante Operam referred to the era class of construction 1976-1990.

Figure 3.

Combinations of the opaque envelope types in the Ante Operam referred to the era class of construction 1976-1990.

Regarding the typology of windows, during the period between 1976 and 2005, windows were mainly double-glazed windows with an air gap generally with wooden frames with a ggl,ŋ of 0,75 and a thermal transmittance U of 2,80 W/m2K. These specifications are used in the simulation. Similarly, to what was done for the envelope types, the most commonly used conditioning system typology used in the period class of construction was considered, namely, as a generator, a standard boiler for a centralized system with an atmospheric burner and a chimney > 10 m with an efficiency n of 0.73 and, as emission terminals, radiators whose specifications are given in the UNI/TS 11300-2 standard [

21]. Such a building, with its different construction types reencountered in the defined age class, is placed within six different climatic zones (

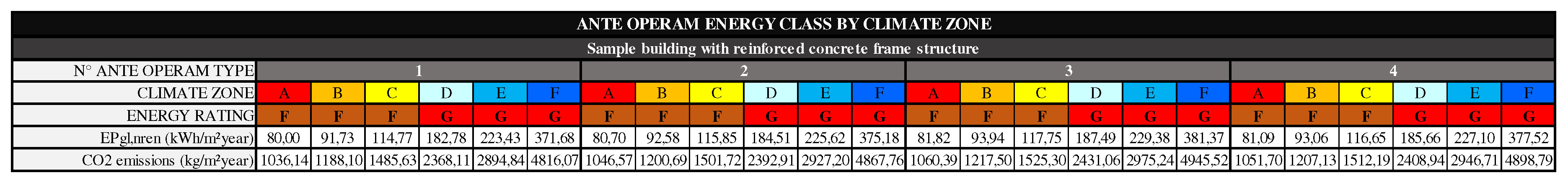

Figure 4) chosen. It is found, as was to be expected, that for all four building types, the energy class of the state of the art turns out to be comparable for the same climate zone (

Figure 5).

Contextually, for each building type identified, the energy class rating obtained from the Energy Performance Certificate is defined within all six Italian climate zones. This phase of investigation is conducted with the support of the Energy Modeling Software through which the energy models of the typologies of the sample actual state are determined.

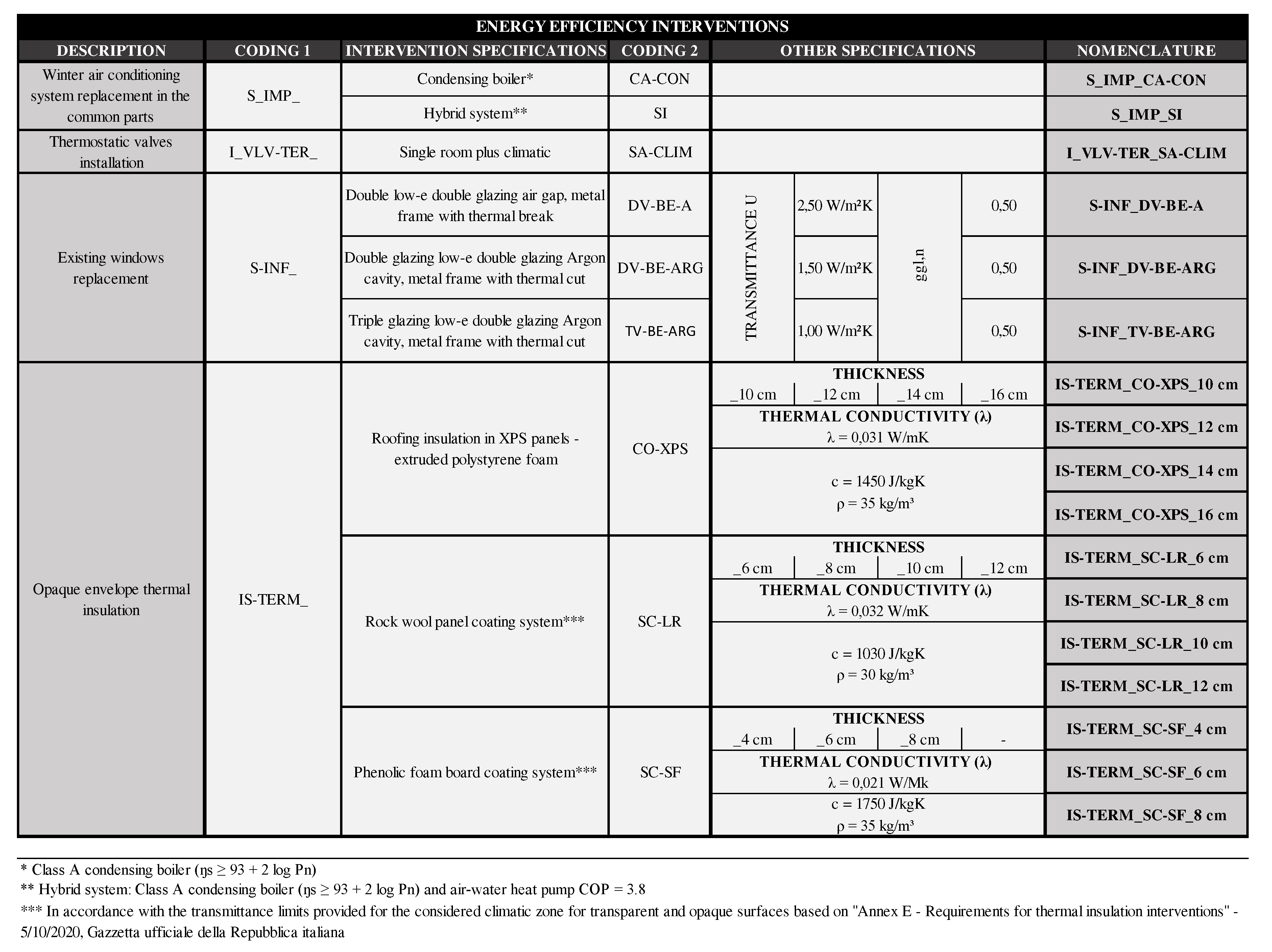

2.3. Definition of Simulations of Efficiency Interventions

In the subsequent phase, all the potential combinations of energy efficiency upgrading interventions, varying in their impact on the building and residents, are formulated. These interventions aim to achieve a transition to at least energy class E by 2030 and energy class D by 2033, compared to the existing state of the art, for each identified Ante Operam typology. All Post Operam simulations of the sample are conducted, once again, using the energy performance certificate software.

The methodological process for conducting all case simulations is specifically focused on a single typological combination. This combination is precisely determined by the fact that, for all four building types, there exists a similar building structure type where, as demonstrated, the same energy class was achieved in the Ante Operam phase. Firstly, interventions that can be replicated uniformly across each condominium building are identified. These interventions can be of three types:

Interventions on the envelope (whether opaque or transparent),

Interventions for the replacement of the existing conditioning system,

Combined interventions for the building envelope and systems (

Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Possible energy efficiency interventions definition with their own nomenclature.

Figure 6.

Possible energy efficiency interventions definition with their own nomenclature.

Each intervention has its unique nomenclature derived from its specific aspects. To achieve the energy class jump to E by 2030 and the energy class jump to D by 2033, possible combinations of leading and trailing interventions are defined. All combinations of the simulated interventions are generated while adhering to minimum transmittance values of the architectural components, including horizontal opaque structures (roofs and floors), vertical opaque structures (perimeter walls), and vertical transparent structures (windows and doors). The specific amounts of these components are adjusted based on the climatic area where the building is located, as stipulated in “Allegato E—Requisiti degli interventi di isolamento termico” (5/10/2020, Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana [

22]), calculated according to UNI EN ISO 6946:2007 standards. Additionally, the replacement systems must meet minimum efficiency requirements. For the replacement of the winter air conditioning system in common areas, two options are considered: installing a condensing boiler (S_IMP_CO-CON) or implementing a hybrid system that combines a heat pump with a condensing boiler (S_IMP_SI). The leading intervention, which involves replacing the standard boiler with a condensing boiler, must meet the requirement of a minimum useful thermal efficiency at load equal to 100%, as mandated by the regulations, where ŋs ≥ 93+2logPn. Additionally, the system itself must belong to product class A.

The intervention involving the installation of a hybrid system must always incorporate a condensing boiler belonging to product class A. The hybrid system should have a useful thermal efficiency at 100% load equal to ŋs ≥ 93+2logPn, and the heat pump component should have a minimum Coefficient Of Performance (COP) of 3.8 for air-water heat pumps with a useful heating thermal output less than 35 kW. These requirements apply to interventions with a work start date after October 6, 2020, which includes the simulation case. Furthermore, the ratio of the rated useful heating output of the heat pump to the rated useful heating output of the boiler must be ≤ 0.5 [

23]. Moreover, in conjunction with such interventions, where technically feasible, there is an obligation to install low thermal inertia thermostatic valves (or other modulating type thermoregulation system) to control the flow rate at the existing heating bodies (I_VLV-TER_SAM-CLIM) [

22].

Regarding the efficiency of the vertical opaque envelope, simulations are conducted using two different types of thermal insulation with distinct technical specifications and cost per square meter: rock wool and phenolic foam. The first type of insulation (IS-TERM_SC-LR_sp) is commonly utilized for external cladding due to its water-repellent and fire-retardant properties, recyclability, excellent sound absorption, and resistance to mold, fungi, and bacteria formation. It falls within the low-price range (<30 €/sqm) and has a good thermal conductivity value (λ = 0.032 W/mK). The second type of insulation (IS-TERM_SC-SF_sp) belongs to the medium-high price range (>70 and < 100 €/sqm), but it boasts an excellent thermal conductivity value (λ = 0.021 W/mK), allowing for thinner panels to be applied on the facade compared to the first option of rock wool insulation. The selection of these two different insulation solutions is motivated by the desire to subsequently compare the simulations based on the cost-effectiveness of the class jump ratio and the final price.

For opaque horizontal surfaces, such as roofs, the preferred insulation material used is XPS (Extruded Expanded Polystyrene). XPS offers excellent impact resistance and has a good thermal conductivity value (λ = 0.031 W/mK). Additionally, it falls within the low-price range (<30 €/sqm). The thickness of the insulation panels will be determined based on the requirement to comply with the maximum values of thermal transmittance for the specific climate zone. Consequently, the insulation thickness will increase when transitioning from climate zone A to climate zone F. Concerning the efficiency of the transparent envelope, the simulations incorporate three distinct types of window frames, with varying transmittance and specifications depending on the climate zone in which they will be installed as replacements for existing ones. The most commonly employed window frame types are as follows:

low-emissivity double-glazed window frames with air gap and metal frame with thermal break from the manufacturer transmittance Uf = 2.5 W/sq mK and solar factor gg,l = 0.50 (S-INF_DV-BE-A);

low-emissivity double-glazed window frames with Argon cavity and metal frame with thermal break from manufacturer transmittance Uf=1.50 W/sqmK and solar factor gg,l = 0.50 (S-INF_DV-BE-ARG);

low-emissivity triple-glazed window frames with Argon cavity and metal frame with thermal break from manufacturer transmittance Uf= 1.00 Q/sqmK and solar factor gg,l = 0.50 (S-INF_TV-BE-ARG).

Appendix A presents the complete set of combinations derived from the simulation conducted on the selected sample, serving as a guide for improving the energy efficiency of the Italian residential building stock constructed during the 1970s and 1980s. The table below provides the specifications for each combination, with their nomenclature derived from the climate zone in which the condominium building is situated. The combinations are categorized based on the specific technical element on which the interventions are focused: envelope only, air conditioning system only, or a combination of interventions targeting both the envelope and system.

2.4. Economic Estimation of Energy Efficiency Interventions

In this phase, the costs per square meter for each combination of interventions are determined to classify them into specific price ranges: low, medium-low, medium, medium-high, or high. This allows beneficiaries of this tool to align their chosen intervention typology with their budgetary constraints. Following the identification of the potential intervention combinations, the Energy Performance Certificates (A.P.E.) for the various Post Operam scenarios are systematically processed, considering the new energy class ranking. The ranking begins with minimal class jumps and progresses towards more comprehensive interventions that yield higher energy performance, particularly in cases of mixed interventions targeting both the building envelope and systems. Furthermore, for each combination, the parametric cost per square meter is estimated and depicted on a graph, reflecting the magnitude of the cost within the low, medium, or high range (

Figure 7).

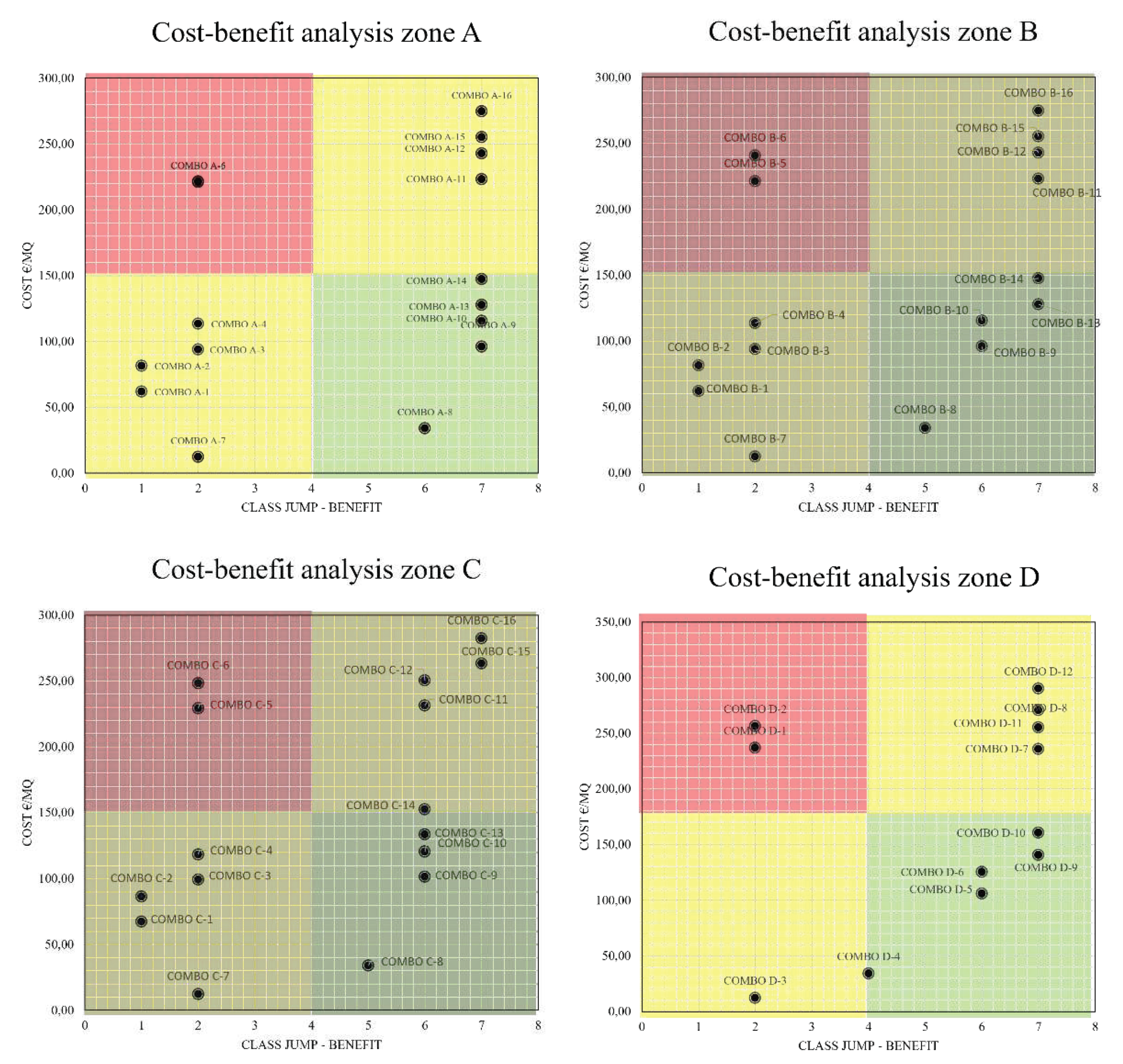

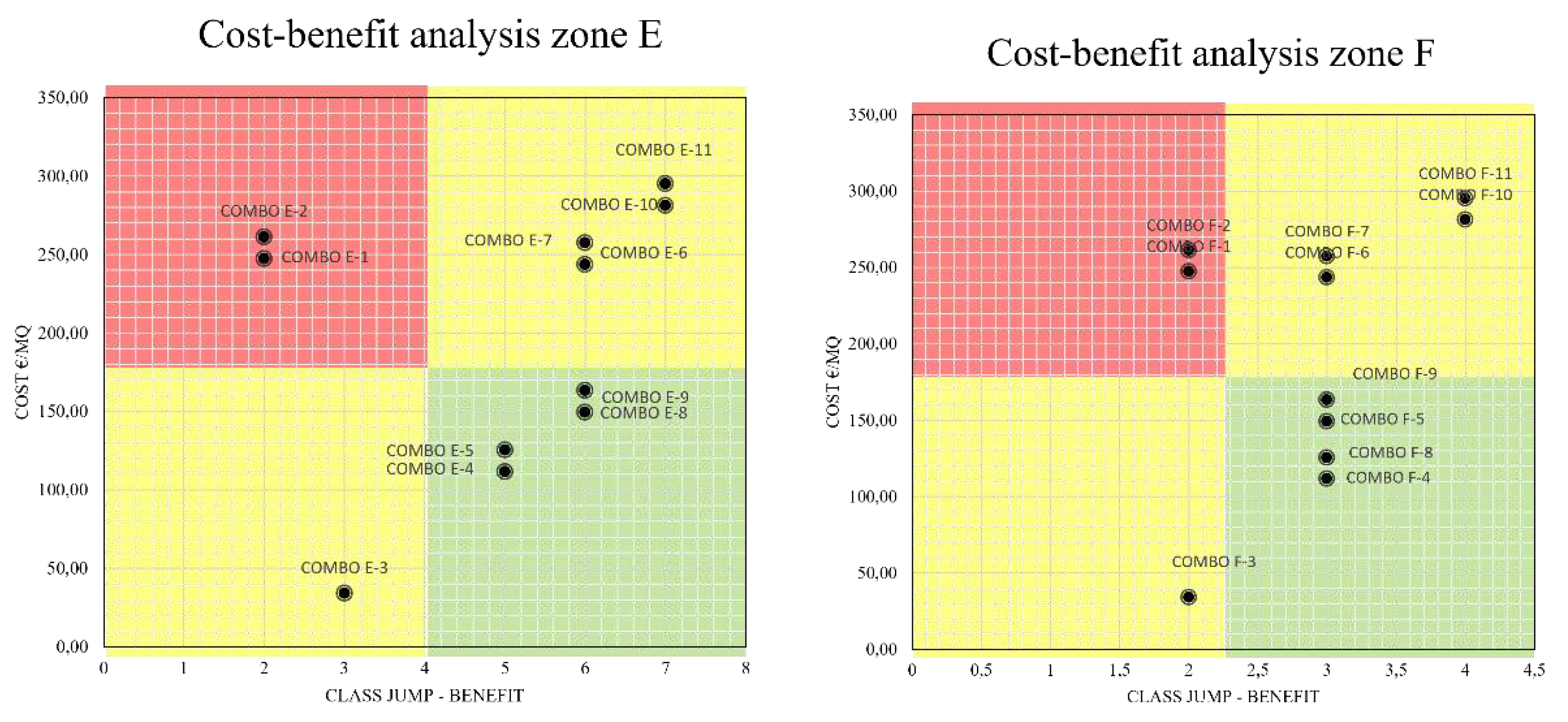

This phase of the study involves data processing and the identification of all intervention combinations associated with a specific energy class jump. The graphs in

Figure 8, categorized by climate zone, display all the intervention combinations (COMBO_Climatic Zone—N°). The green areas represent the most cost-effective interventions in terms of quality-price ratio, while the yellow areas indicate moderately convenient interventions. The red areas represent interventions that are less economically viable, considering the combination of high costs and minimal energy class improvement. These cost estimates were derived from an example building, using the DEI 2023 Price List (“Prezzario DEI 2023”) as a reference.

3. Results

The study of the national building stock clearly indicates that existing buildings constitute a crucial sector for reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the forthcoming years. In this context, the proposed research aims to develop a support decision tool for enhancing the energy efficiency of existing buildings through an analysis of the building heritage and a systematic approach to refurbishment.

The research has led to the development of a tool to identify the combination of energy efficiency solutions most suitable for the building’s characteristics and the climatic zone.

Appendix 2 provides a dynamic summary matrix of all intervention combinations categorized by climate zone, Ante Operam energy class, intervention type, Post Operam energy class, number of energy class jumps, and cost per square meter.

The tool allows users to determine the climatic zone in which the building, subject to future energy efficiency interventions, is located. Subsequently, the characteristics of the opaque and transparent building envelope before the intervention, as well as the type of installed system, are identified. The tool automatically presents the user with the most suitable combinations of solutions for the specific case study. Additionally, it allows further selection of combinations based on cost, within a specified price range.

4. Discussion

The cost-benefit analysis tables provided by each combination offer a clear and summarized overview of the most and least advantageous interventions to be performed. From the cost-benefit analysis (

Figure 8), it is evident that the most favorable interventions, considering the amount spent and the achieved class jump, across all six climate zones, involve the replacement of the existing air conditioning system with a hybrid system and the installation of thermostatic valves. Similarly, interventions that include rock wool insulation for opaque surfaces show favorable cost-effectiveness. On the other hand, interventions solely focused on the opaque and transparent envelope appear to be less advantageous. The proposed tool for enhancing the energy efficiency of buildings constructed in the 1970s and 1980s provides standardized intervention solutions that can be immediately applied to achieve the desired class jump, aiming for a minimum of class E by 2030 and class D by 2033, while considering cost-effectiveness.

5. Conclusions and Future Developments

The national and international construction sectors are in urgent need of a substantial decarbonization process, particularly in the context of deep renovation of the built environment, as the existing building stock is outdated. The improvement of energy efficiency in existing condominium buildings is becoming increasingly critical due to the European directive “EPBD,” which mandates member countries to achieve a minimum of energy class E by 2030 and class D by 2033. The research proposes a tool that addresses this need by providing a systematic approach to enhancing the energy efficiency of condominium buildings constructed between 1976 and 1990.

The tool develops a matrix of standardized interventions based on the number of energy classes skipped (starting from energy class E in the post-operam phase) and the resulting outcomes in terms of expenses per square meter and benefits obtained. This tool not only enables the determination of the energy class that can be achieved through the implementation of specific combinations of interventions, as outlined in

Appendix A of the article, but also assesses their cost-effectiveness.

Importantly, this tool is of significant relevance for future European directives, which are expected to become more stringent in the pursuit of decarbonizing the built environment. Furthermore, future developments of the energy efficiency tool will focus on creating an advanced BIM-based tool that can automatically identify recommended interventions for users based on factors such as climatic zone, building typology, construction type, and cost considerations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Appendix A: Summary of all the hypothesized intervention combinations in the simulations; Appendix B: summary dynamic matrix of all combinations of interventions.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, E.P. and C.Z.; methodology, E.P.; validation, C.Z., E.P. and F.C.; investigation, C.Z.; data curation, C.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, C.Z. and E.P.; writing—review and editing, C.Z. and E.P; visualization, F.C.; supervision, F.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

The

Appendix A summarizes all the combinations of interventions hypothesized in the simulations, along with their specific descriptions and reference nomenclature, which allow achieving a certain energy class in the Post Operam from an existing energy class. They range from the simplest interventions to more complex ones, divided into: interventions on the opaque and transparent building envelope, interventions on the conditioning system, and mixed interventions.

Appendix B

The

Appendix B represents the matrix that reports, for each climatic zone, the Ante-Operam energy class, the type of intervention desired, the name of the combination, the number of skipped energy classes, and the target final energy class based on the cost-benefit ratio.

References

- A. S. Cordero, S.G. Melgar, J.M. Andujar Marquez. “Green Building Rating Systems and the New Framework Level(s): A Critical Review of Sustainability Certification within Europe”. Energies 2019, 13, 66. [CrossRef]

- Cumo, F.; Giustini, F.; Pennacchia, E.; Romeo, C. “Support Decision Tool for Sustainable Energy Requalification the Existing Residential Building Stock. The Case Study of Trevignano Romano”. Energies 2021, 14, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris Agreement on Climate Change. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/climate-change/paris-agreement/.

- Ramos Ruiz, G.; Olloqui del Olmo, A. “Climate Change Performance of nZEB Buildings”. Buildings 2022, 12, 1755. 2022; 12, 1755. [CrossRef]

- Gago, A.; Labandeira, X.; Hanemann, M.; Ramos, A. (2013) “Climate Change, Buildings and Energy Prices”. Alcoa Advancing Sustainability Initiative to Research and Leverage Actionable Solutions on Energy and Environmental Economics. Journal “Economics for energy”.

- “Global Alliance for Buildings and Construction, International Energy Agency and the United Nations Environment Programme. 2019 Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction: Towards a Zero-Emission, Efficient and Resilient Buildings and Construction Sector”. Available online: https://www.unenvironment.org/resources/publication/2019-global-status-report-buildings-and-construction-sector.

- Eurostat. Energy Consumption in Households. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Energy_consumption_in_households (accessed on 23 November 2020).

- Magrini, A.; Lentini, G.; Cuman, S.; Bodrato, A.; Marenco, L., “From nearly zero energy buildings (NZEB) to positive energy buildings (PEB): The next challenge -The most recent European trends with some notes on the energy analysis of a forerunner PEB example”, Dev. Built Environ. 3(2020). [CrossRef]

- European Commission. EU Building Stock Observatory. Available online: https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/energy-efficiency/energy-efficient-buildings/eu-building-stock-observatory_en (accessed on 31 November 2023).

- Censimento Popolazione Abitazioni: costruisci le tue tavole con data warehouse. Available online: http://dati-censimentopopolazione.istat.it/Index.aspx.

- Agostinelli, S. , “DEEP RENOVATION. Criteri di efficientamento energetico degli edifici”. Project “NERSELVES Interreg Europe Horizon (2020)”.

- Sung, U.J.; Kim, S.H. , “Development of a Passive and Active Technology Package Standard and Database for Application to Zero Energy Buildings in South Korea”. Energies 2019, 12, 1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milardi, M.; Musarella, C.C. “Smart envelope and climate context” 2019 IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 296 012040.

- Ministero dello Sviluppo Economico, Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Tutela del Territorio e del Mare, Ministero delle Infrastrutture e dei Trasporti. “Strategia per la riqualificazione energetica del parco immobiliare nazionale”, 2020.

- Parlamento Europeo, Energy Performance of Buildings Directive. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/ATAG/2023/739377/EPRS_ATA (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- Ballarini, I.; Corgnati, S.P.; Corrado, V. Use of reference buildings to assess the energy saving potentials of the residential building stock: The experience of TABULA project. Energy Policy 2014, 68, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggieri, G.; Andreolli, F.; Zangheri, P. “A Policy Roadmap for the Energy Renovation of the Residential and Educational Building Stock in Italy”. Energies 2023, 16, 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camera dei deputati Ufficio rapporti con l’Unione europea XVIII Legislatura (12 aprile 2022), Pacchetto “Pronti per il 55%”: la revisione della direttiva sulla prestazione energetica nell’edilizia. Available online: http://documenti.camera.it/leg18/dossier/pdf/ES065.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2023).

- Ministero dello Sviluppo Economico, Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Tutela del Territorio e del Mare, Ministero delle Infrastrutture e dei Trasporti. “Strategia per la riqualificazione energetica del parco immobiliare nazionale”, 2020.

- Cumo, F. (CITERA, La Sapienza), F. Giustini (CITERA, La Sapienza), E. Pennacchia (CITERA, La Sapienza), “Stato dell’arte di soluzioni tecnologiche di involucro edilizio esistenti come base per interventi di Deep Renovation del patrimonio immobiliare nel settore abitativo”, pp. 11-12, pp. 99-118, 12/2019.

- “Tabula—Fascicolo sulla tipologia ediliza italiana” redatto dal gruppo di ricerca TEBE del Politecnico di Torino.

- “Allegato E—Requisiti degli interventi di isolamento termico”—5/10/2020, Gazzetta ufficiale della Repubblica italiana.

- Agenzia nazionale efficienza energetica ENEA, “Vadenecum: Sistemi ibridi (comma 2.1; articolo 14, D.L. 63/2013 e ss.mm.ii.—Requisiti tecnici dell’intervento”, pp. 2, 25/01/2021.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).