1. Introduction

Respiratory clinical management for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis [ALS] patients prior to the COVID-19 pandemic was predicated upon clinic-based quarterly pulmonary function testing [Ackrivo 2019; Khamankar 2018]. Both prior to, and during, the pandemic, attempts to monitor pulmonary function testing via unsupervised At-Home Telespirometry (AHT) were variably affected by technical performance and adherence issues [Rutkove 2019,2020; Geronimo 2019; Helleman 2022, Shefner 2022]. Surveillance of rates of decline with upright or erect forced vital capacity [eFVC] and supine forced vital capacity [sFVC] together have proven precision in predicting onset of respiratory failure with decrease in survival in ALS [Elamin 2019; Pirola 2019; Schmidt 2006] compared with eFVC changes alone [Ackrivo 2019; Baumann 2010; Varrato 2000; Lechtzin 2002]. In this report, we describe the implementation of a novel internet-supervised respiratory monitoring system previously deployed for cystic fibrosis [Ong 2021]. Internet-supervised AHT measured eFVC and sFVC in ALS patients was reported to a clinical dashboard with pulmonologist and neurologist review of pulmonary function testing to provide respiratory information for patient management. The deployment, accuracy, feasibility/adherence and acceptance of eFVC and sFVC measured by internet-supervised AHT in the home setting in ALS patients longitudinally is reported in this pilot implementation study.

Long-term pulmonary surveillance is a critical part of the management of the ALS patient over the disease course. The eFVC and sFVC rate of change was found to be an independent predictor of survival in ALS [Elamin 2019]. Beginning 17 months after ALS onset, in those ALS patients initiating non-invasive ventilation, over 50 % predicted eFVC loss has occurred by the 6 months prior to initiation of non-invasive ventilation (NIV) [Panchabhai, 2019]. While some ALS patients may not manifest eFVC decline in this time after onset, it is crucial to have a system in place to monitor these early changes in eFVC that might occur during` the 3-month intervals between quarterly ALS Clinic visits. Access to pulmonary function testing has significantly contributed to delay in initiation of respiratory care with NIV [Georges, 2017] which underscores the necessity to advance development of remote respiratory monitoring capabilities for ALS patients in the intervals between quarterly canonical ALS Clinic visits.

We describe the implementation and integration of internet - supervised AHT in an ALS multidisciplinary specialty outpatient clinic. The primary objectives assess the deployment, accuracy, feasibility/adherence and acceptability of measuring eFVC and sFVC obtained with in-clinic-conventional [Viaire and Vyasis, USA] and in-clinic-portable as well as at-home-portable [MIR Spirobank Smart, Italy] spirometers according to American Thoracic Society / European Respiratory Society [ATS/ERS] standards [Graham 2019]. The secondary objectives analyze longitudinal changes in eFVC and sFVC measured in the total population with a linear random mixed effects model stratified by eFVC baseline at entry compared with quantal % predicted drops in eFVC and sFVC measured in each subject by clinic-based and internet-based respiratory therapist supervised coaching.

Abbreviations Forced Vital Capacity (FVC); Erect Forced Vital Capacity (eFVC); Supine Forced Vital Capacity (sFVC); At-Home Telespirometry (AHT); Non-Invasive Ventilation (NIV); Global Lung Index 2012 (GLI-2012); Research Electronic Data Capture (Red Cap); Electronic Medical Record (EMR)

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design: Subject Recruitment, Equipment – MIR spirometer / ZephyRx Dashboard, Respiratory Therapist / Caregiver procedures in clinic and in-home settings, Data Acceptability, Medical Record Data Integration and Respiratory Care Management, Research Electronic Data Capture (RedCap) Database Procedures

2.1.1. Subject Recruitment

Participants had a Revised El Escorial-Awaji Criteria classified diagnosis of ALS and were offered remote monitoring of eFVC and sFVC irrespective of their baseline eFVC and requirement for use of NIV support. Personal use of smartphone and Internet availability from home were required to perform supervised home-based spirometry. Testing from home was scheduled not to exceed once every 30 days in accordance with medical insurance reimbursement guidelines.

2.1.2. Spirometer / Software

A single patient-use, pre-calibrated, handheld turbine MIR Spirobank Smart spirometer, with volume accuracy +/- 2.5% that complies with the ATS 2019 standards (Sacco 2020), was provided to each patient with an integrated software application for online-access to respiratory data transmitted via personal smart phones. Volume accuracy of the portable spirometer hand-held device has been separately validated at +/- 3% or 50 ml and flow accuracy at +/- 5% or 200 ml [Degryse 2012].

The internet-based clinical dashboard and software mobile application [ZephyRx], under FDA Enforcement Discretion, was the implemented platform used for collecting respiratory data from the MIR Spirobank Smart spirometer [Ong 2021, Berlinski 2023].

Real-time data reporting allows patients and providers to access results automatically displayed and time-stamped in a live clinic dashboard [https://dashboard.zephyrx.com]. The mobile application was downloaded on the patient’s personal iOS or Android smartphone with Blue-tooth enabled connection to portable spirometer using clinic Wi-Fi. If the clinic Wi-Fi connection failed, the portable pulmonary function testing was conducted from home as close to the time of the clinic spirometry as possible. Demographic information, including patient name, gender, birth date, ethnicity, current height and weight at the time of respiratory test, was entered into the dashboard and updated when necessary. eFVC and sFVC in liters and expressed as a percentage of predicted vital capacity based on the Global Lung Initiative GLI-2012 predictive equations [Quanjer 2012] was automatically generated, visually displayed with flow-volume loop and trend observed over period of remote monitoring. A Consent to Share message was displayed on the application screen for patients to grant permission to share their data with Upstate University Hospital as required for encrypted data to be manually uploaded to HIPAA-compliant Electronic Medical Record (EMR). Pulmonary function test and demographic data were stored in the cloud-based ZephyRx database prior to entry into EMR and Research Electronic Data Capture (Red Cap).

2.1.3. Respiratory Therapist Procedures

The conventional laboratory spirometer and portable spirometer were used to measure eFVC and sFVC in clinic with no pre-determined assigned order. To prevent fatigue from multiple repositioning, patients were asked to conduct the supine breathing tests sequentially using portable and conventional spirometers. Sufficient rest time between maneuvers was encouraged, so that the respiratory therapist and patient agreed that the next maneuver could begin. Minimal inter-test intervals were two minutes per protocol but could be longer depending on fatigue, if present. Three university hospital-based respiratory therapists performed supervised measurements directly at both in-person clinic and via internet at-home locations with a uniform technique and supervised vigorous coaching. In-person training of the patient and caregiver was facilitated at the ALS clinic by MIR Spirometer-trained respiratory therapists and ALS clinic staff and their feedback was sought routinely. Nose clips were applied, and patient’s lips sealed around the mouthpiece. Respiratory therapist performed an assessment of tight seal around the mouthpiece and switch over to a full oronasal face mask interface, when needed, to ensure an adequate seal for eFVC and sFVC measurement without leak. If oronasal mask was used, consistency of interface was maintained throughout the procedure. Patients were first asked to breath at least 3 tidal breaths until end-expiratory lung volume was stable within 15% of tidal volume, then take in maximal inspiration and breathe out to the limit of maximal expiration. A minimum of three acceptable eFVC and sFVC maneuvers were attempted to meet reproducibility criteria. If the difference in eFVC or sFVC between the largest and second largest acceptable maneuver was >150 ml [or 10% eFVC or sFVC], then additional trials were undertaken, if possible. The largest value from acceptable maneuvers was selected by the respiratory therapist and reported as the best value [Miller 2008, Graham 2019]. AHT required Respiratory Therapist to maintain internet connectivity and troubleshoot missed firmware updates and Wi-Fi signal interference from other electronics, while simultaneously observing the patient and computer display. Although the same coaching instructions were provided by respiratory therapists throughout the entire spirometric maneuver, respiratory therapists perceived that AHT requires significantly more attention than in-person clinic encounter to complete the testing maneuvers. This increased attention and time-spent resulted from the increased performance of in-home sFVC measurements compared with in-clinic sFVC measurements.

2.1.4. Caregiver Procedures

Caregiver instruction considered ALS-specific barriers to remote testing including loss of hand dexterity or limb paralysis, oral-facial weakness, and cognitive-behavioral impairment; particularly in taking a deep inspiration, temporarily holding the breath and then controlling blowing out the entire vital capacity. The techniques of applying nose clips, ensuring no mechanical obstruction between mouth and cylinder, and maximizing seal around mouthpiece or oronasal mask use were emphasized. Careful transfers to obtain sFVC, caregiver assistance for simultaneously maneuvering a smartphone and hand-held spirometer throughout respiratory testing, maintenance and disinfection of spirometer, were part of safety instruction requirements.

2.1.5. Data Acceptability

FVC data and performance of exhalation profile were reviewed and accepted or rejected by respiratory therapist. Data dashboard reported acceptable and repeatable eFVC and sFVC maneuvers based on ATS 2019 quality standards. Acceptability of exhalation loop was met in 53 out of 119 FVC measurements (47%) conducted from home comparable with reports in ALS [Sanjak 2010; Rutkove 2019, 2020; Geronimo 2019; Murray 2021; Sheffner 2022]. Repeatability of FVC maneuver was met in 9 out of 119 measurements (7.6%), In the ALS population studied, repeatability was very low and attributed to fatigue. ATS/ERS criteria have been studied in quality assurance studies. In young subjects with and without neuromuscular disease, ALS, Parkinson disease, and elderly subjects with and without cognitive impairment, decreased acceptability and repeatability benchmarks have been noted [Mayer 2015; Czajkowska-Malinowska 2013; Hampson 2017; Turkeshi 2017; Allen 2009]. In one previous study, this decrease in repeatability was noted at FVC below 70 %predicted [Sanjak 2010]. FVC measurements that do not meet technical criteria for acceptability were determined to be clinically useful by respiratory therapist supervising AHT and included in the analysis per current recommendations to employ modified criteria (Mayer 2015; Graham 2019).

2.1.6. Medical Record Data Integration and Respiratory Care Management.

Although the ZephyRx dashboard automatically reports highest value and generates acceptability and repeatability feedback, the respiratory therapist can confirm or override the system. Subsequent to measurement, the interpretation of results and quality feedback were reviewed and approved by board-certified pulmonologists in real time for entry into electronic medical record. Respiratory data review was conducted and treatment plan recommendations were made by board-certified neurologists, primarily caring for the ALS patients, including consultation, as needed, with board-certified pulmonologists.

2.1.7. Research Electronic Data Capture (RedCap) Database Procedures The Upstate Medical University Institutional Review Board (IRB 1795328) approved the compilation of standard clinical, clinimetric and pulmonary function measurements from electronic health records of consecutive ALS patients at a single-center in Central New York that launched AHT between July 2020 to June 2021 in Research Electronic Data Capture (RedCap) Database for analysis.

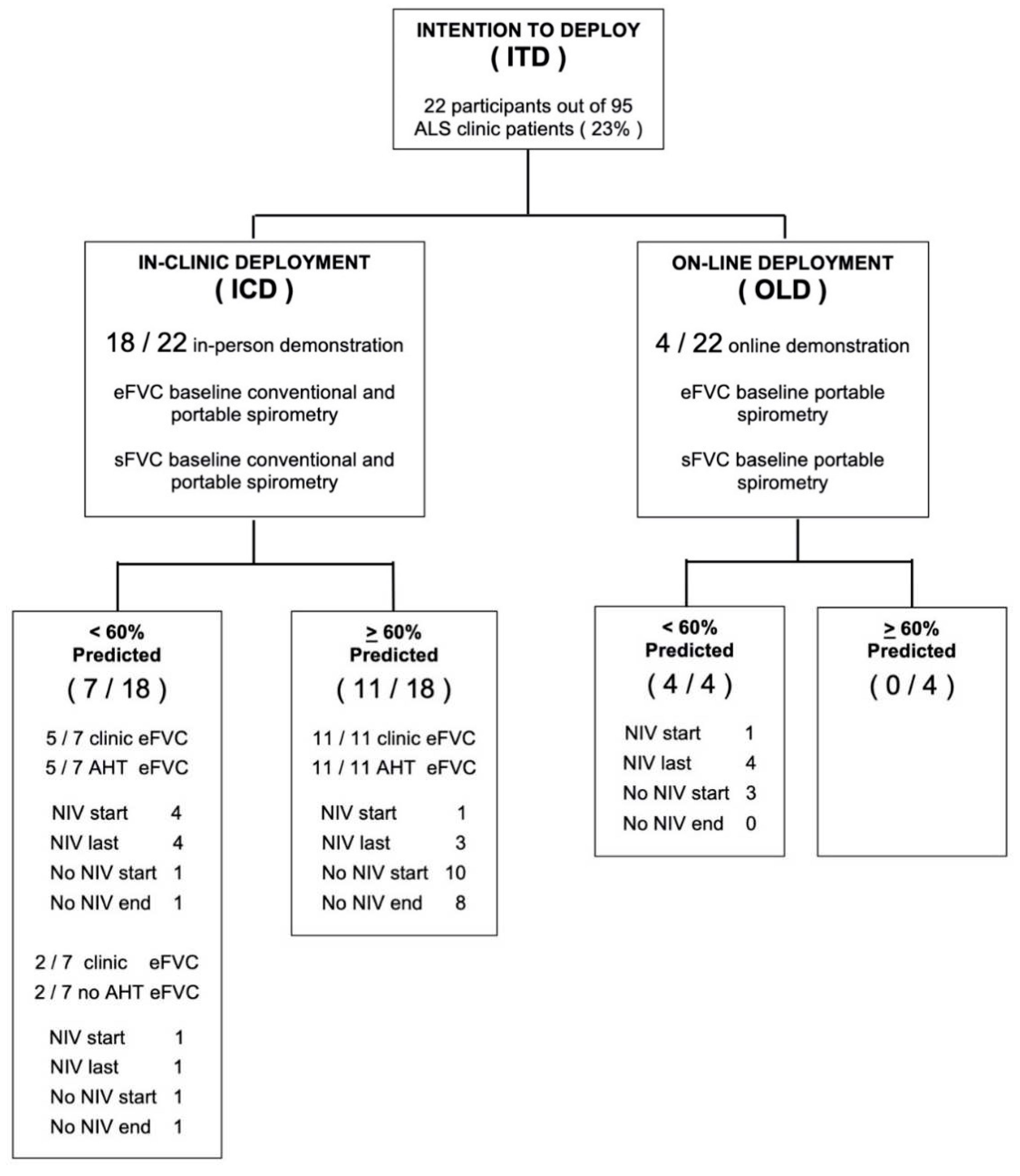

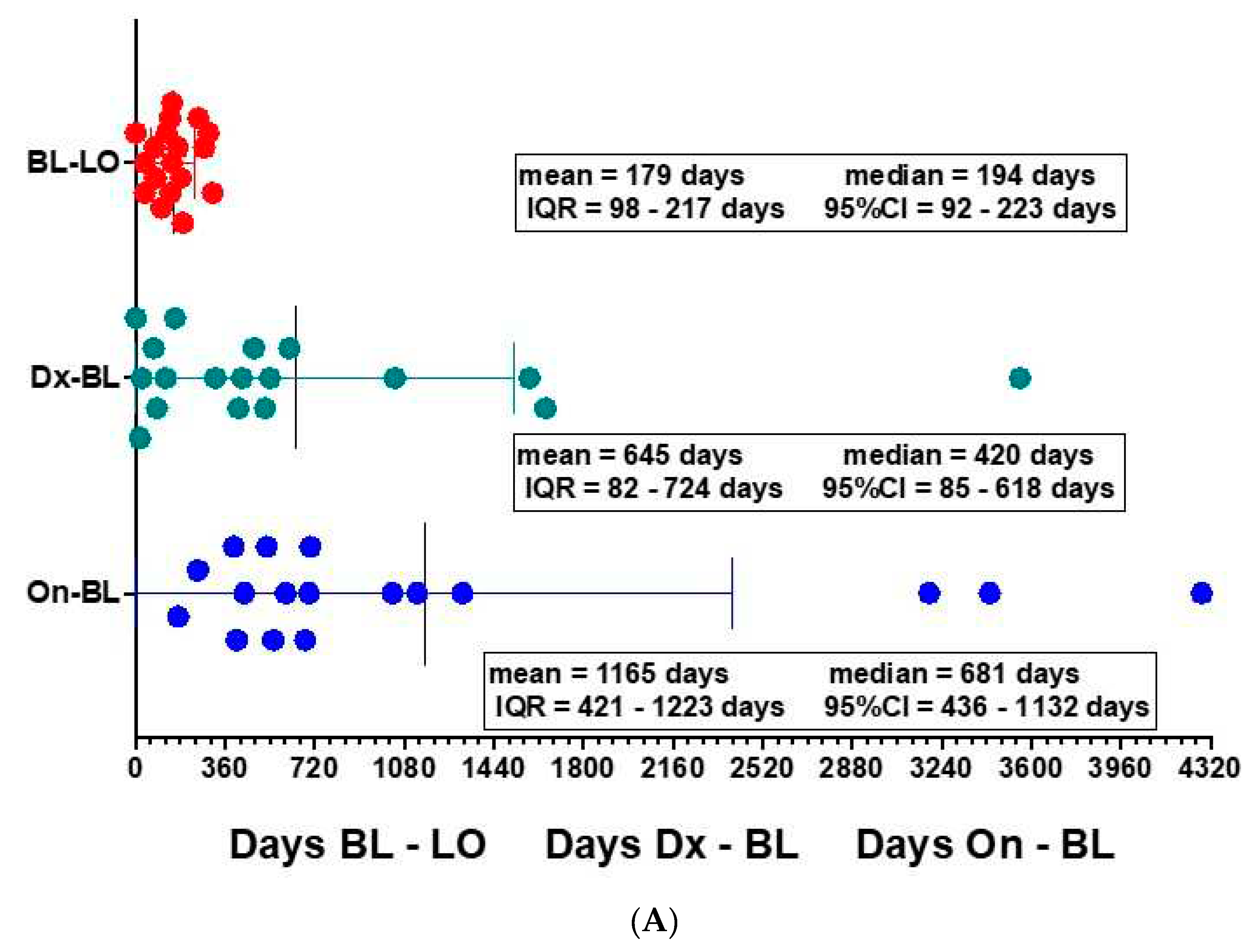

2.2. Study Initiation: Deployment

Deployment The initial deployment included 22 ALS participants from a total of 95 ALS clinic patients (23%) seen between July 2020 to June 2021 comparable to the initial deployment rate of MIR Spirometer-ZephyRx system in cystic fibrosis clinics in the United States (Ong 2021). The mean age of patients was 65 years old. Participants were grouped according to baseline eFVC % predicted using conventional spirometry (See

Table 1). Eighteen participants (81.8 %) presented to clinic for conventional spirometry and demonstration of use of portable spirometry. Sixteen participants (72.7%) acquired at least one remote test using portable spirometry from home. Standard stratification of entry eFVC into tertiles: > 80% predicted and above, 60% - 80% predicted, and < 60% predicted was altered to stratification by stratification above and below median

> 60% predicted and < 60 % predicted based on lack of comparable subject membership in tertiles (Chio 2022). The mean number of supervised AHT measurements was 3.8 for entry eFVC

> 60 % predicted and 0.9 for entry eFVC

<60 % predicted over the observation period. Two participants with eFVC< 60% predicted at baseline, initiated portable testing at clinic but elected not to monitor respiratory testing from home. Dropout was attributed to anxiety from readily viewing FVC results on smartphone and lack of motivation due to use of NIV (See

Figure 1). Eighteen participants (81.8 %) completed at least one in-clinic visit but four participants (18.2 %) with relatively advanced disease stages were completely unable to travel to clinic for the entire study duration due to pandemic conditions prevailing at the time of recruitment.

Table 2 shows the profile of these patients who were unable to physically access the ALS clinic and therefore portable spirometers were deployed directly to their homes with on-line demonstration of AHT.

Three sub-cohorts are defined –

[

1] Intention To Deploy [ ITD ] = 22;

[

2] In-Clinic Deployment [ ICD ] = 18 consisting of subjects who received In-Clinic Laboratory eFVC sFVC prior to Internet – Supervised At Home Telespirometry (AHT); and [

3] Online Deployment [ OLD ] = 4 consisting of subjects who initiated Online eFVC sFVC

Internet – Supervised AHT without In-Clinic Laboratory eFVC sFVC.

ICD subjects had 6 NIV at BL increasing by 2 NIV to 8 / 18 NIV.

OLD subjects had 1 NIV at BL increasing by 3 NIV to 4 / 4 NIV.

ITD subjects had a total of 7 NIV at BL increasing by 5 to 12/22 NIV

2.3. Statistical Analyses

2.3.1. eFVC and sFVC Slope Analysis – Random Effects Linear Models

To evaluate whether the linear trend of eFVC over time differs by eFVC at baseline or by NIV usage, random effects linear models were fitted to subjects in the In-Clinic Deployment Intention to Deploy cohort, where time measured in months, age at onset or diagnosis, onset to diagnosis interval, baseline ALS-FRS-R at start of eFVC measurement, in addition to the > 60% predicted / < 60 % predicted baseline stratification and time by the > 60% predicted / < 60 % predicted baseline stratification interaction, were included as fixed effects and subject was included as random effect.

2.3.2. eFVC and sFVC Decrease between FVC Measurements – Rate Analysis

eFVC % predicted and sFVC % predicted on each succeeding measurement was compared with the previous measurement. When the change in eFVC % predicted was greater than 3 % predicted per month, the measurement was designated as an eFVC 3 % predicted drop [ Fallat 1979; Schiffman1993 ; Elamin 2019 ]. When the change in sFVC was greater than 1 % predicted per month, the measurement was designated as sFVC 1% predicted drop.

We analyzed the rate of drops of eFVC 3 % and sFVC 1% per month across the > 60 % predicted and < 60 % predicted stratification groups to gain insights with regard to the possible relationship of the eFVC and sFVC at baseline measurement with the rate of drops during observation with internet-supervised AHT.

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 9.4.1 [458] for macOS [GraphPad Software, La Jolla California USA,

www.graphpad.com 2022], MedCalc for Windows, version 20.114 – 32 bit [MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium

https://www.medcalc.org, 2022], R software version 4.1.3, or SAS/STAT software version 9.4, when appropriate.

3. Results

3.1. Validation of ZephyRx Dashboard Software in ALS: FVC % predicted value Reference Equation Accuracy During Repeated Measurements

Spirometric reference standardization methodology is a foundation for the accuracy and validity of clinical measurements of pulmonary function in ALS patients (van Eijk 2019 ). Independent tabulation of eFVC % predicted values was performed using GLI-2012 online calculator equations based on age, height, gender, ethnicity and compared with ZephyRx dashboard-derived values for each eFVC and sFVC measurement. A third of dashboard-reported eFVC and sFVC measurements were found to be decreased by 1% predicted than manually calculated measurements (29 out of 87 AHT) and appeared to be a fairly consistent difference in the first 1/3 of home spirometry followed longitudinally. This finding was reviewed with the ZephyRx software development team. The ZephyRx Dashboard algorithm results were assessed to identify a possible systematic error to account for the difference. ZephyRx Dashboard, using birth date to automatically update age to one decimal place, applied GLI-2012 Lookup Equations with repeated AHT measurements over time and was confirmed to be performed accurately. Age, as of time of spirometry, must be reported to one decimal place to provide accurate baseline percent predicted vital capacity values. [Graham 2019]

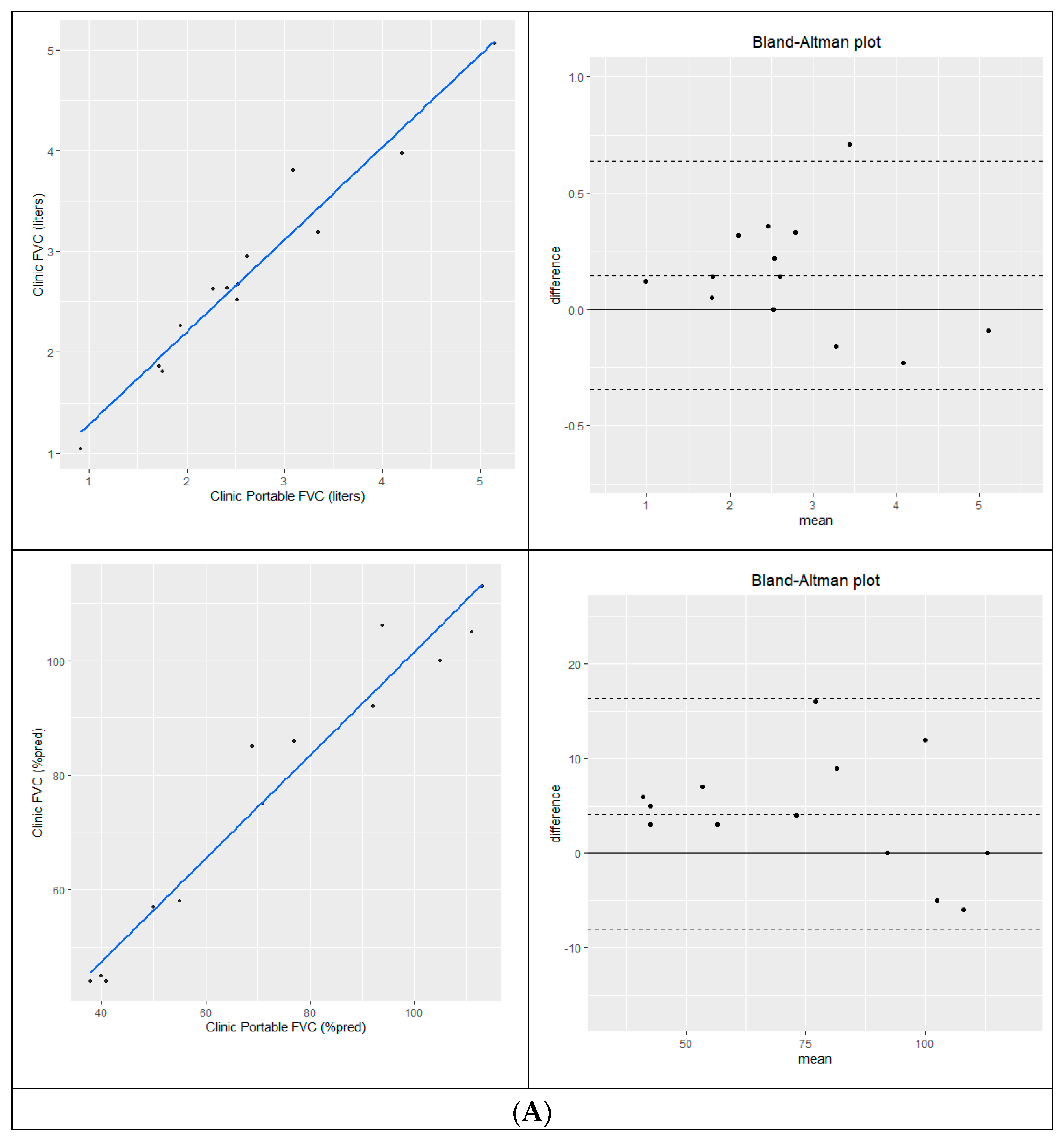

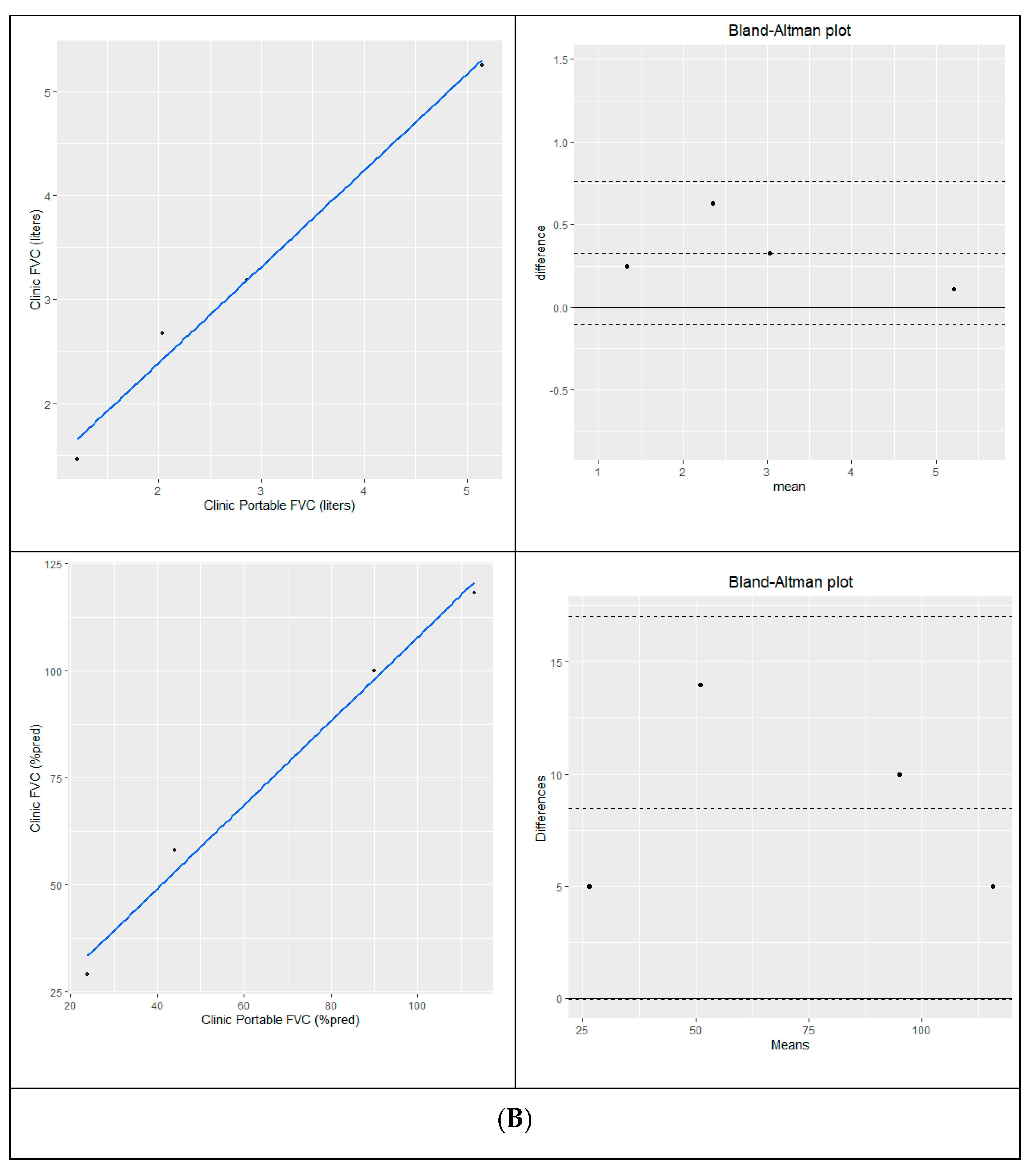

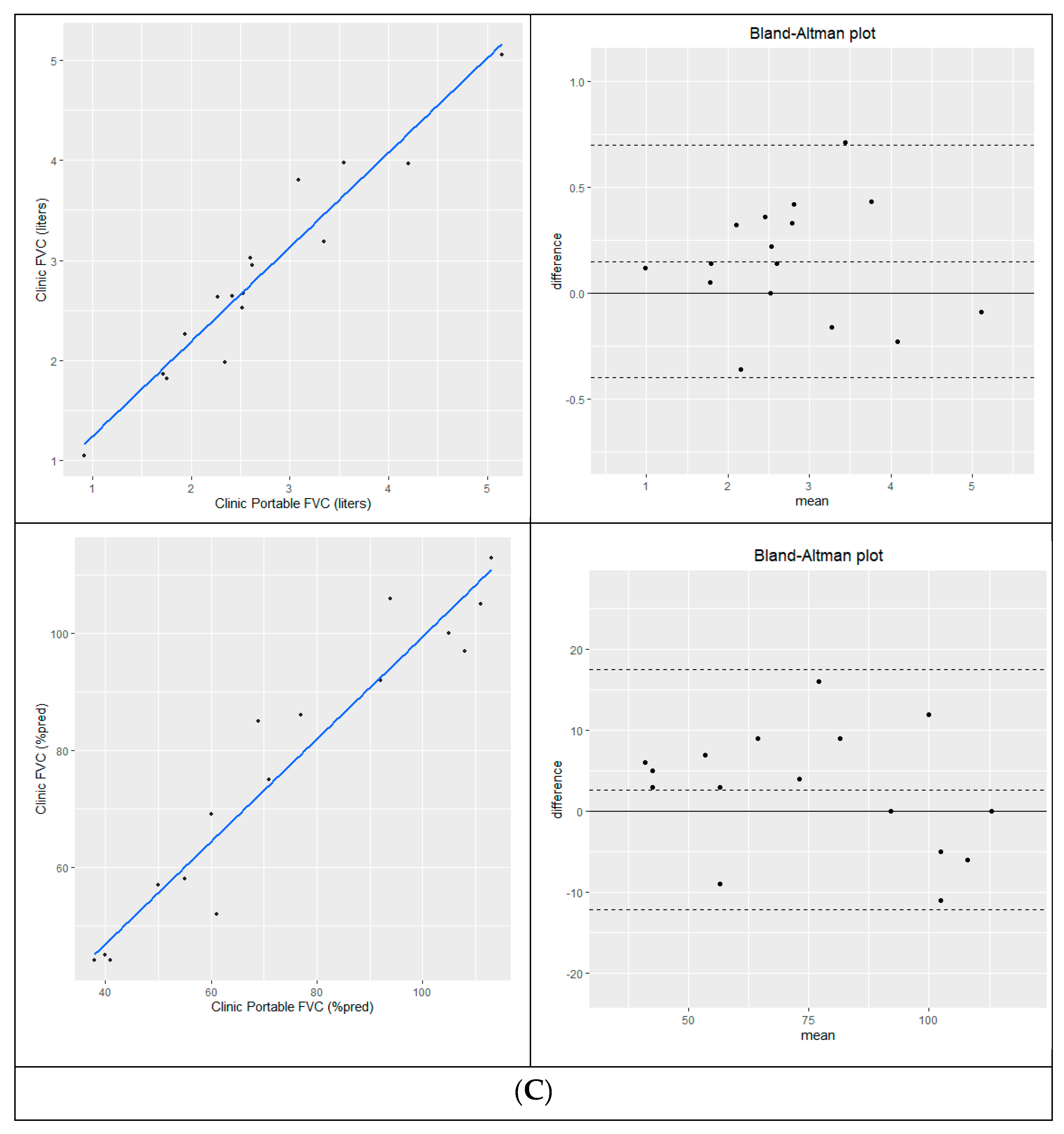

3.2. Validation of MIR Spirometer in ALS: FVC % predicted Baseline Portable Spirometry Compared with Conventional Spirometry | Confirmation of Measurement Bias

Accuracy of internet-supervised AHT was assessed by validation of portable eFVC and sFVC with conventional eFVC and sFVC measured in ALS clinic as direct liter measurements and as transformed age, gender adjusted percent predicted vital capacity according to GLI-2012 equations (van Eijk 2019). Pearson correlation coefficient assessed the correlation between eFVC and sFVC measurement using conventional and portable spirometry, and Bland-Altman analysis was performed to evaluate the mean difference of potential measurement bias with 95% limits of agreement.

3.2.1. FVC % predicted Baseline Portable Spirometry Compared with Conventional Spirometry

Measurement of eFVC using conventional and portable spirometry acquired during the same clinic visit [N=13] were highly correlated in liters [R

2=0.95, p < 0.0001] and % predicted [R

2=0.952, p < 0.0001]. Bland-Altman analysis showed good agreement with a mean difference of 0.147L [conventional – portable]; 95% limits of agreement =-0.345L to 0.639L and 4.1 %predicted [conventional-portable] with 95% limits of agreement [-8.0 %p-16.3 %p]. In-clinic sFVC [N=4] measurements were highly correlated in liters [R

2=0.987, p=0.007] and % predicted [R

2=0.987, p=0.007] with a mean difference of = 0.330L [conventional – portable]; 95% limits of agreement =-0.101L to 0.761L and 8.5% predicted [conventional-portable] with 95% limits of agreement [0.0 %p -17.0 %p]. Same day eFVC and sFVC study correlation and Bland-Altman analysis are shown in

Figure 2A-B.

Baseline portable spirometry that could not be obtained at clinic was measured from home within a week. Cross-sectional analysis of clinic and home spirometry within a plus-minus 7-day window is a validation method that has been used to assess repeatability and reliability in a cystic fibrosis study [Paynter 2021]. Measurement of eFVC using conventional and portable spirometry acquired within a 7-day period [N=16] were highly correlated in liters [R

2=0.926; p<0.0001] and % predicted [R

2=0.922, p < 0.001]. Bland-Altman analysis of 16 pairs of eFVC conventional and portable spirometry acquired within a 7-day time frame showed a mean difference of 0.150 L [conventional – portable]; 95% limits of agreement [ -0.40L, 0.70L ] and 2.7 % predicted [conventional-portable] with 95% limits of agreement [ -12.1%, 17.5% ] is shown in

Figure 2C.

3.2.2. Confirmation of Measurement Bias

The presence of a higher conventional spirometer value compared with portable MIR spirometer value confirmed measurement bias. This measurement bias had been previously reported for the MIR Spirometer in non-ALS primary pulmonary disease populations but is within the ATS/ERS guidelines [Degryse 2012; Geronimo 2019].

3.3. Longitudinal Measurement of eFVC and sFVC:

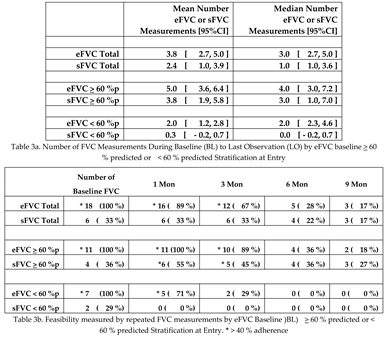

3.3.1. Number of FVC Measurements Stratified by eFVC baseline > 60 % predicted or < 60 % predicted at Entry:

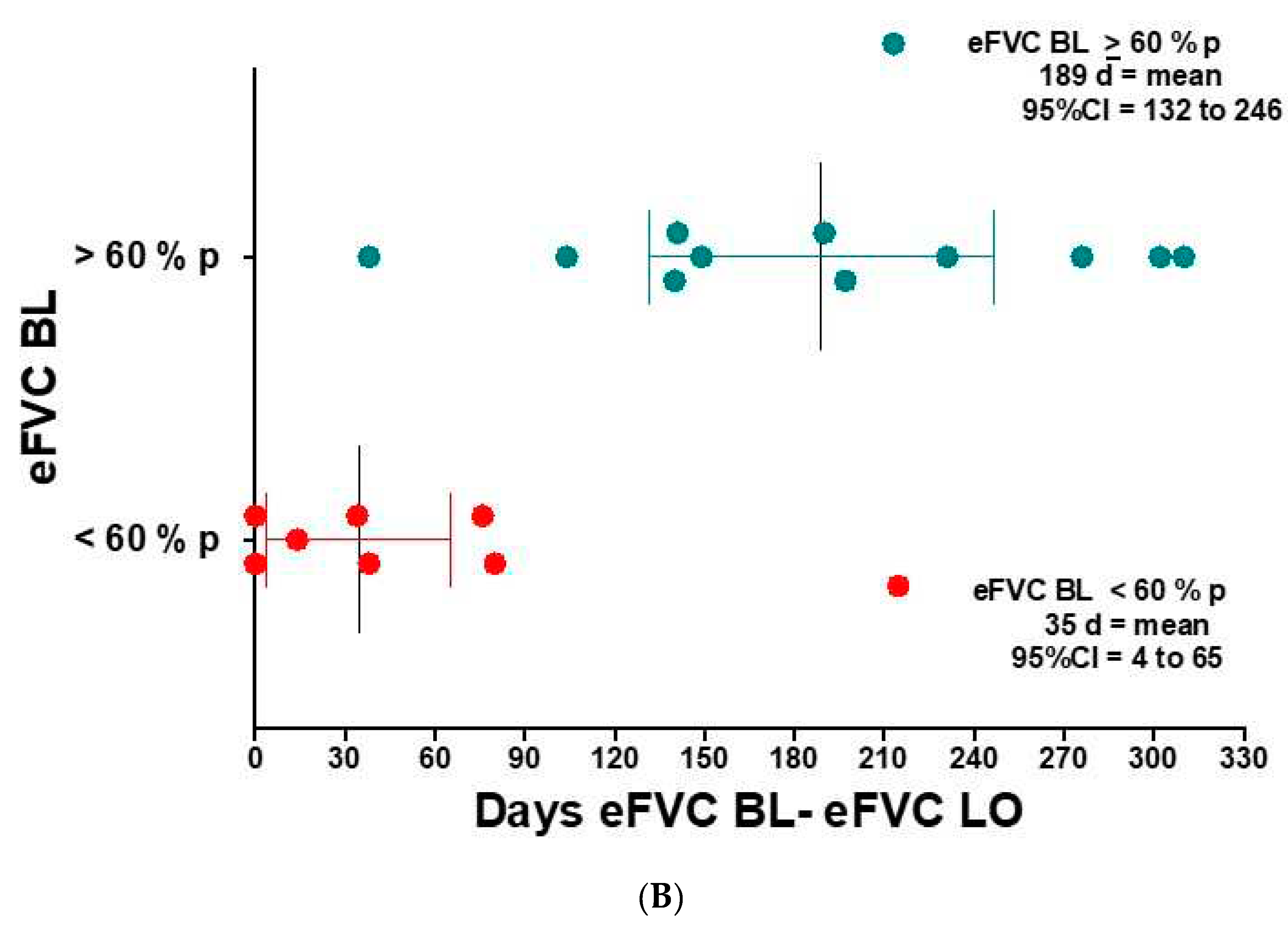

In this pilot implementation study of AHT in 18 ALS subjects in the In-clinic Deployment cohort, we recruited incident (13 - newly diagnosed < 3 years from onset) and prevalent (5 - slowly progressive > 3 years from onset) ALS subjects. The incident ALS subjects were within three years from diagnosis [See

Figure 3A]. Respiratory symptoms in ALS subjects are differentially present according to the measurement values of eFVC and sFVC [ Varrato 2001; Schmidt 2006]. ALS subjects were stratified by eFVC %p [Chio 2022; Torrieri 2022: Fallat 1979] at initial baseline evaluation. ALS subjects in the lowest eFVC group (< 60 % predicted) constituted a cohort with statistically significant shortest follow-up observation period [median= 35 days] [ANOVA; P = 0.0018] compared with the

> 60 % predicted group [See

Figure 3B].

3.3.2. Feasibility and Adherence

eFVC measurements are significantly (Chi square Yates correction P = 0.0021) more common than sFVC measurements in this first US clinic-based implementation study of internet-supervised AHT in ALS patients [

Table 3a ]. Higher adherence to supine testing of FVC was reported with remote monitoring from home. There were thirty-five sFVC measurements out of 52 AHT [67.31%] vs. 9 sFVC measurements out of 21 conventional spirometry measurements [42.86%] [ Chi-square P =0.0533]. Lack of mobility and difficulty with transfers were the most frequently encountered barrier in performing supine testing in clinic and at home.

The overall feasibility measured by repeated eFVC measurements through 3 months was 67% in the Syracuse ALS Center clinic-based ALS study [

Table 3b]. This observation is consistent with other ALS studies: 82% in US Norris ALS Center clinic-based study (Fallat 1979), 80 % in Strasbourg France clinic-based study (Enache 2017), 43% in Brisbane Australia clinic-based study (Baumann 2010), 64% in US VA Tampa clinic-based study (Elamin 2019), 51% in US ALS at Home telehealth-based study (Rutkove 2020), 100% in Utrecht selected subject 3 month observational research study (Helleman 2022). eFVC measurements are not statistically different by baseline FVC % predicted

> 60 % predicted versus < 60 % predicted but eFVC measurements are significantly (Chi square Yates correction P = 0.0263) decreased at and after 3 months observation in the < 60 %p eFVC baseline group. The number of eFVC measurements (P= 0.0025) and sFVC measurements (P= 0.0025) were statistically significantly less in the < 60 %p baseline eFVC subjects compared with the

> 60 % predicted eFVC subjects reflecting the shortened observation period in this group.

3.4. Longitudinal Measurement of eFVC and sFVC:

Longitudinal Graph of eFVC and sFVC Measurements from Baseline to Last Measurement Random Effects Linear Model Slope Analysis | Individual Inter-Quarterly Interval Analysis | Survival Analysis Differentiated by eFVC baseline > 60 % predicted and < 60 % predicted at Entry

eFVC and sFVC changes may be assessed by [

1] slope changes in each ALS subject, [

2] slope changes measured for ALS subject populations by Random Effects Linear Model Slope Analysis and [

3] occurrence of prespecified changes in eFVC and sFVC between measurements over time.

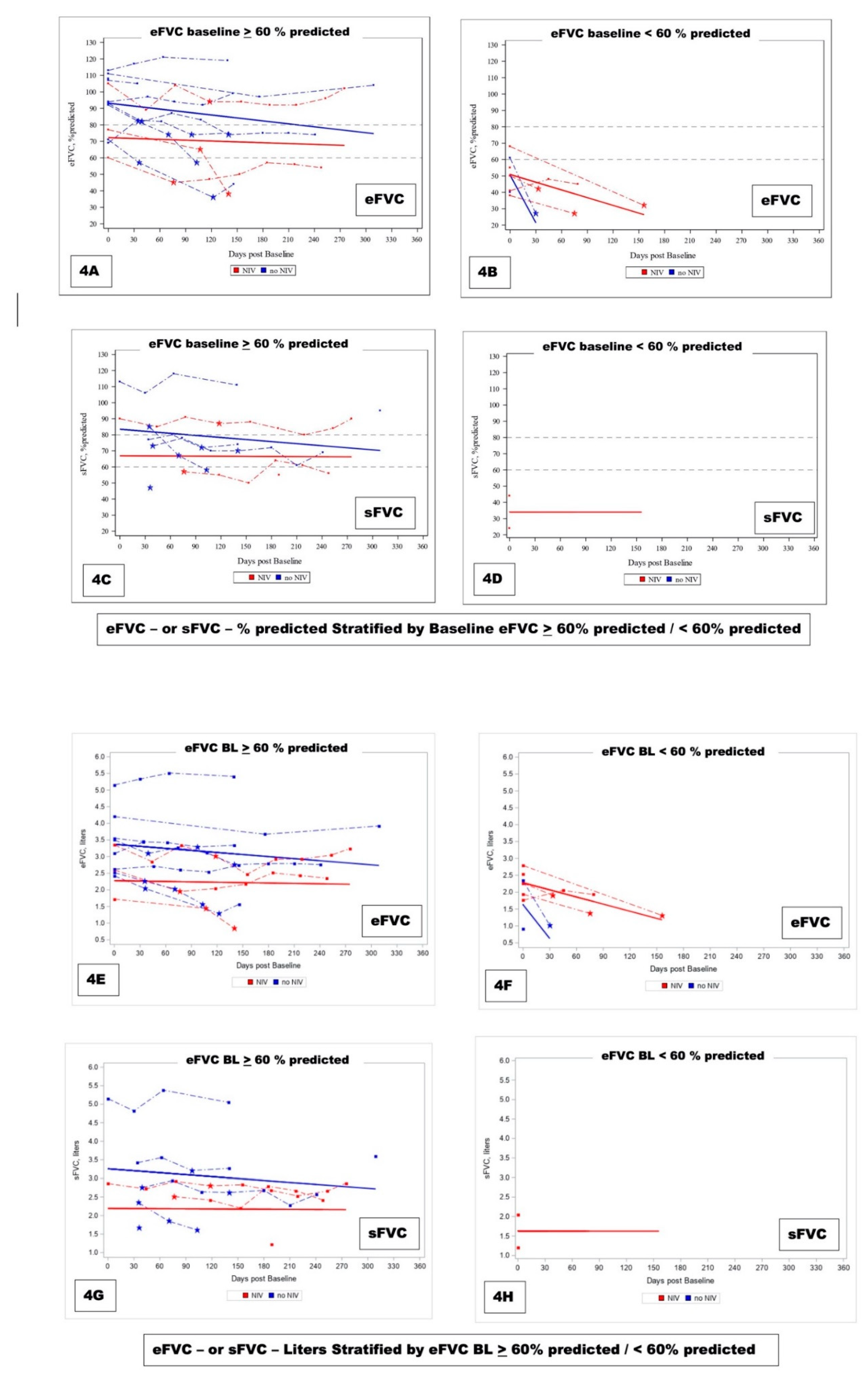

3.4.1. Longitudinal Graph of eFVC and sFVC Measurements from Baseline (BL) to Last Observation ( LO )

eFVC and sFVC were graphed longitudinally [

Figure 4 ] and monthly rate of change was analyzed with slope measurement using all data per patient (Pirola 2019). The monthly rate of change of eFVC and sFVC was measured in patients stratified according to their designated baseline seated eFVC obtained with initial conventional clinic or at home portable (if no baseline clinic data) spirometry as

> 60 % predicted versus < 60 % predicted with subsequent FVC obtained remotely through internet-supervised AHT. The use of NIV is shown in a longitudinal plot to reflect NIV use vs. no NIV use according to baseline eFVC % predicted in

Figure 4A-B-C-D and in liters in

Figure 4E-F-G-H.

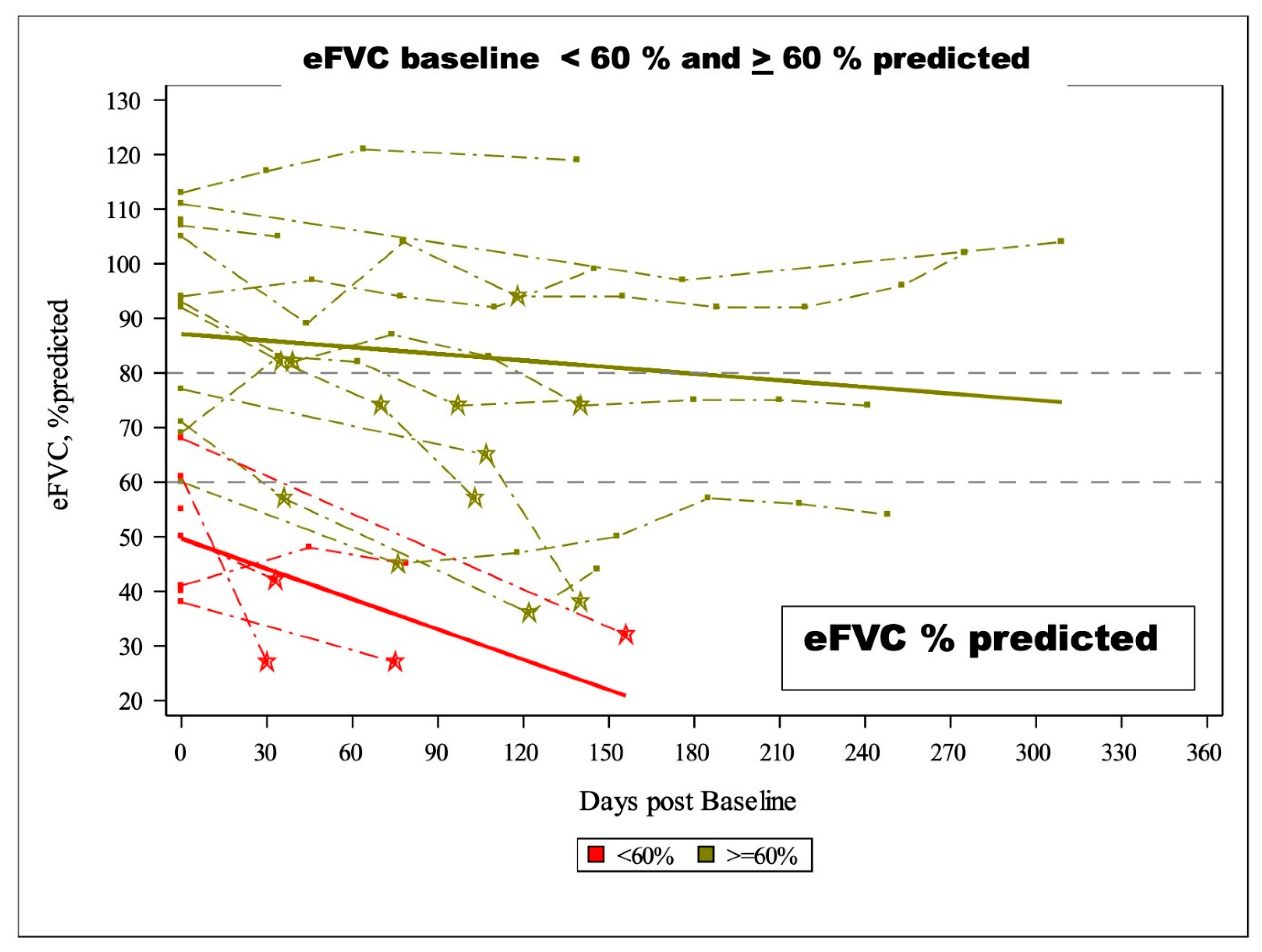

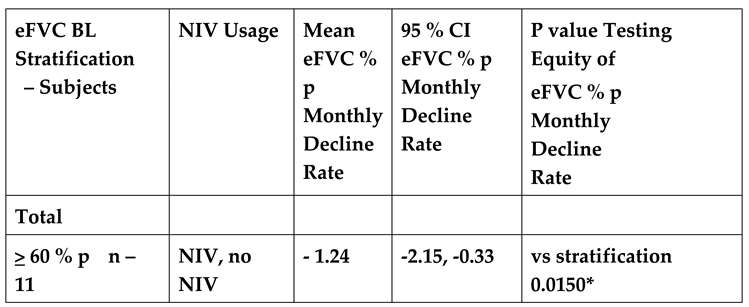

3.4.2. Random effects linear model measuring total cohort eFVC and sFVC slope change over time in cohorts stratified by eFVC baseline (BL) > 60 % predicted or < 60 % predicted at Entry

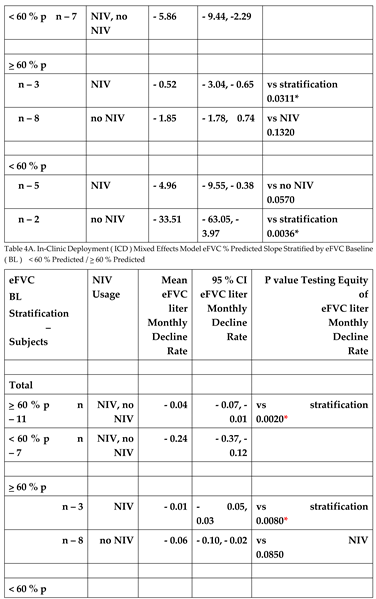

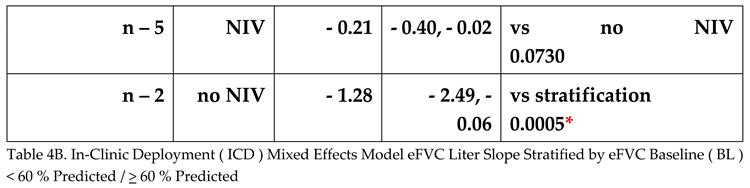

The random effects linear model provided slopes for the ICD cohort {NIV and no NIV together; NIV alone, no NIV alone} stratified by the eFVC > 60 % predicted and < 60 % predicted BL cohorts. Adjustments in the random effects linear mixed model included (1) age at onset or diagnosis, (2) onset to diagnosis interval (incident or prevalent), (3) baseline ALSFRS-R at start of FVC measurement, (4) stratification by eFVC > 60 % predicted or < 60 % predicted BL cohort membership, (5) time, and (6) time by stratification by eFVC > 60 % predicted or < 60 % predicted BL cohort membership interaction.

In the random effects linear model, the slope of eFVC decline was statistically significantly faster in eFVC < 60% predicted BL cohort (

Figure 5,

Table 4A 4B). The mean eFVC slope decline for the eFVC

> 60 % predicted BL cohort was – 1.24 % predicted per month [ 95% CI - 2.15 ,- 0.33% predicted ] statistically significantly (P=0.015) less compared with the – 5.86 % predicted per month [ 95% CI - 9.44, - 2.29 % predicted ] decline for the eFVC < 60 % predicted BL cohort.

There was no mitigating effect by NIV in either cohort. In

Figure 4 solid red lines corresponding to model derived slopes for ALS subjects on NIV and blue lines corresponding to ALS subjects not using NIV suggested trends that were not found to be statistically significant (

Table 4A 4B).

In this pilot implementation study, there were not sufficient sFVC data over time to fully evaluate the relationship between rate of change of sFVC alluded to in previously reported analyses of sFVC (Elamin 2019, Ackrivo 2019, Heiman-Patterson 2021).

Figure 5. eFVC % predicted longitudinal measurements obtained with AHT without designating ALS subjects on NIV and stratified by eFVC baseline < 60 % predicted and > 60 % predicted. Slopes correspond to Mixed Effects Model for ICD cohort demonstrating statistically significant faster decline in eFVC baseline < 60 % predicted cohort.

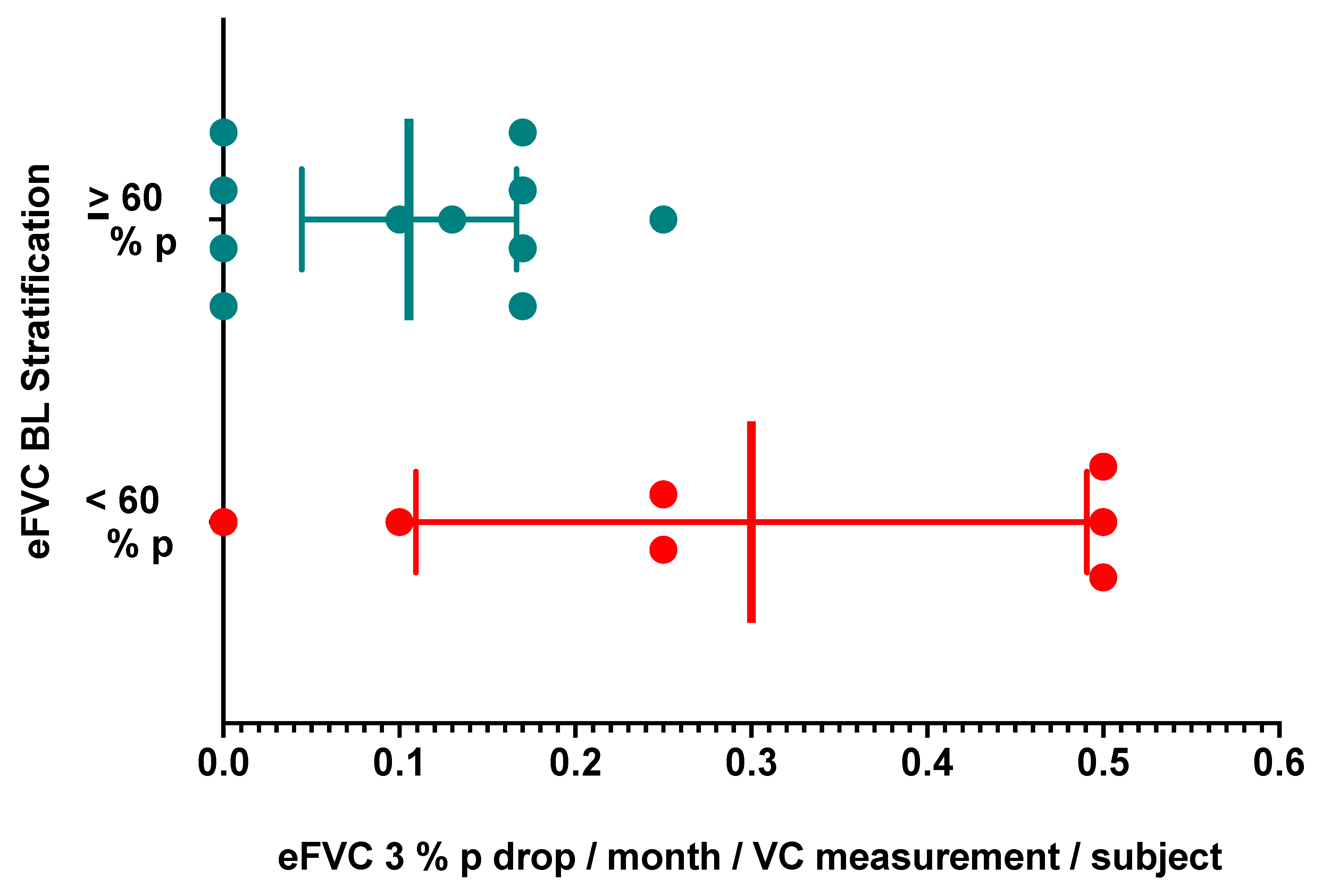

3.4.3. Individual Per-Patient eFVC > 3 % predicted (%p) per month and sFVC > 1 %p per month Drops Occurring Longitudinaly Stratified by eFVC baseline > 60 % Predicted and < 60 % Predicted

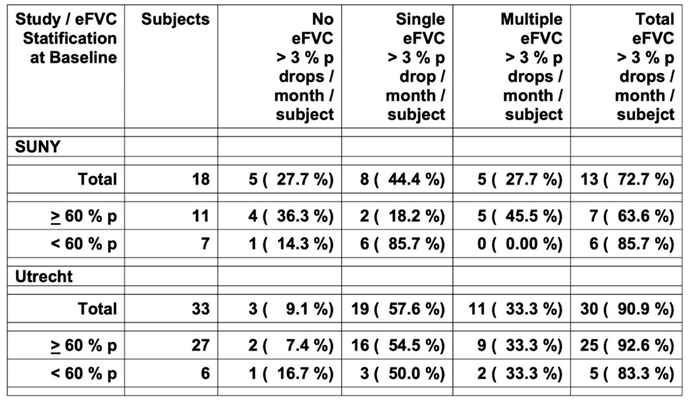

In a larger cohort of 73 ALS participants, a decrease in eFVC slope of greater than 3 %p per month and a decrease in sFVC slope of greater than 1 %p per month over six months observation measured by slope analysis identified a group of ALS participants with statistically significant worse survival compared with ALS subjects who did not demonstrate this change (Pirola 2019). We assessed prospectively a patient-based interval occurrence of these eFVC and sFVC drops to permit a new discovery between eFVC measurements rather than eFVC slope analysis over multiple measurements occurring after many eFVC and sFVC mesurements. We tabulated the inter-interval occurrences of a change in eFVC slope of greater than 3 %p per month and a change in sFVC slope of greater than 1 %p per month during each succeeding vital capacity measurement interval in 18 ALS subjects.

We confirmed that 13/18 ALS subjects (72.7 %) had single or multiple eFVC decreases by 3 % predicted / month during the observation period (

Table 5 ) similar to that reported in 30/33 subjects (90.9 %) from the Utrecht ALS AHT dataset (Helleman 2022). The proportion of eFVC drops of > 3 % predicted per month was not statistically significantly different in the ALS subjects with eFVC baseline < 60 % predicted (85.7 % SUNY, 83.3 % Utrecht) compared with the eFVC baseline

> 60 % predicted (63.6 % SUNY, 92.6 % Utrecht), The proportion of eFVC drops are comparable in both eFVC cohorts stratified by eFVC baseline < 60 % Predicted and

> 60 % predicted; however, in our pilot implementation study the observation period was shorter for the eFVC baseline < 60 % predicted cohort. The mean eFVC > 3 % predicted / month drop rate was 0.3000 [ 95 % CI = 0.1093, 0.4907 ] drops per month per vital capacity measurement per subject in the eFVC baseline < 60 % predicted cohort statistically significantly [ t test P = 0.0137; Mann-Whitney P = 0.0468 ] higher compared with the drop rate of 0.1055 [ 95 % CI = 0.0444, 0.1665 ] in the eFVC baseline

> 60 % predicted cohort [

Figure 6 ]. The comparable multiple > 3 % predicted eFVC drops per month per subject [ 27.7 % SUNY, 33.3 % Utrecht ] are consistent with the 30.1 % rate in the Italian dataset previously reported over 6 months (Pirola 2019). Further analyses in larger datasets are needed to evaluate how these measurements may provide prospective information with respect to ALS progression measured by clinimetric scales, eFVC and survival.

eFVC > 3 % Predicted Drop per Month in SUNY Upstate Medical University – Syracuse New York In – Clinic Deployment Cohort and University Medical Centre Utrecht – Amsterdam Medical Centre ALS Subjects Stratified by FVC Baseline ( BL ) < 60 % Predicted / > 60 % Predicted

Figure 6. eFVC 3 % predicted drop per month per eFVC measurement per subject calculated by delta eFVC % predicted between eFVC measurements divided by days between eFVC measurements per subject corrected to 30-day month rate for subjects in eFVC BL < 60 % predicted and > 60 % predicted cohorts.

3.4.4. Non-invasive Ventilation Management Based on Internet-Supervised AHT

Prompt initiation of NIV in five out of total of 22 patients (23%) of whom 3/4 (75%) were home-bound without access to clinic-based pulmonary function testing, had low eFVC at initial AHT (12-48% predicted), low ALS-FRS-R (14 to 28 out of 48), and received remote AHT training without conventional spirometry. This group of patients obtained eFVC measurements that supported NIV prescription and initiation.

Due to baseline NIV use at AHT deployment, the Intention to Deploy AHT (ITD) Set (N=22) {all ALS patients slated to start AHT} and Full Analysis Set (N=20) [FAS] {all ALS patients who started and continued AHT} are comparable. In those ALS patients not on NIV, statistically significantly [ Chi-Square P=0.0293 ] more NIV initiations occurred in ALS patients [3/4=75%] followed at home with portable spirometry alone compared with ALS patients [2/12=17%] followed in clinic and at home with conventional and portable spirometry.

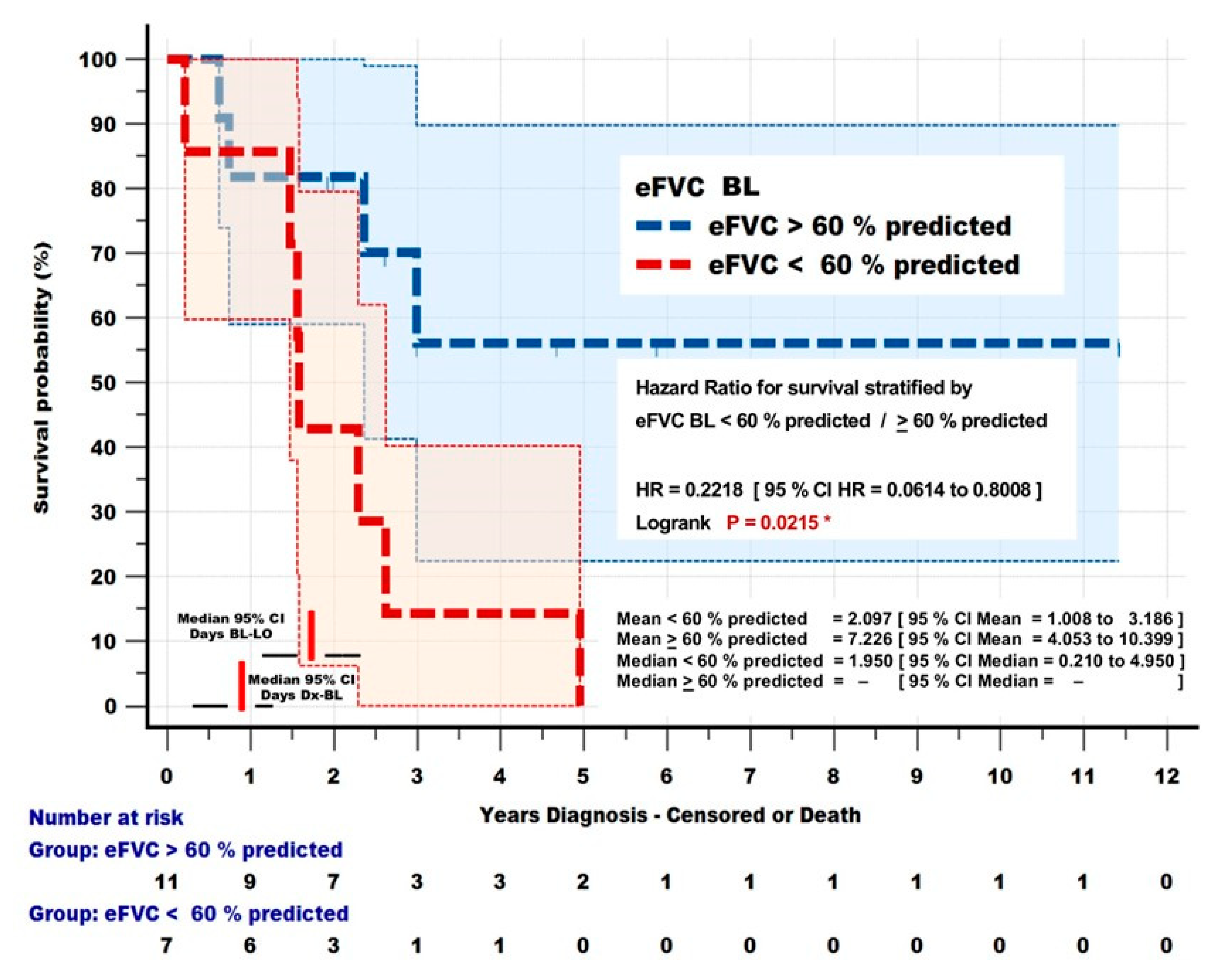

3.4.5. Survival Analysis Differentiated by eFVC baseline > 60 % predicted and < 60 % predicted at Entry

ALS subjects with eFVC baseline < 60 %p at entry into observation, who had statistically significant increased eFVC 3 % predicted drops, also demonstrated statistically significant (< 60 %p mean = 766 days, 95%CI= 368, 1162 days;

> 60 %p mean = 2638 days, 95%CI = 1479, 3797 days; HR = 0.2218 95% CI = 0.07614, 0.8008; P = 0.0215) decreased survival compared with the

> 60% predicted cohort [

Figure 7]. The authors acknowledge that the subgroup analysis of 18 participants is a small sample size, however a similar survival analysis has been performed to measure effects of NIV on survival in a randomized controlled trial in ALS (Bourke 2006).

Figure 7. Survival Dependence on eFVC BL. Kaplan Meier survival analysis of ALS subjects monitored by Internet - Supervised AHT who had eFVC BL < 60 % predicted [ 7 ] and

> 60 % predicted [ 11 ]. eFVC BL < 60 % predicted was associated with a significant [ P = 0.0215 ] reduction in survival [ HR = 0.2218 ].

4. Discussion

We demonstrated the feasibility of implementing internet-supervised at home telespirometry to measure eFVC and sFVC remotely in an ALS multidisciplinary clinic in the USA. Reported difference in spirometric values can be due to systematic difference in spirometric reference standards or a true difference in pulmonary function [Van Eijk 2019]. We confirmed that, as previously described, there can be a systematic difference between conventional and portable spirometry. The calculated eFVC and sFVC as percentage of predicted values based on GLI-2012 was implemented in this deployment. In order to confirm that the same reference standard, GLI-2012 was displayed by the software application, we used a web-based tool to calculate % predicted eFVC and confirmed that spirometric values were standardized according to GLI-2012 [gli-calculator.ersnet.org]. Software applications with video instruction, real-time prompts to guide technique, and automatic data quality analysis of acceptability and repeatability, require vetting by independent ALS neuromuscular and pulmonary researchers within the ALS clinical workspace as we now have initiated to support the creation of guidelines for internet-supervised home spirometryin ALS.

In our sample of ALS patients introduced to internet- supervised AHT, supervision and coaching were seen to contribute to increased adherence in measuring voluntary maximal pulmonary function. Self-directed measurements of vital capacity is a viable option for other chronic pulmonary disorders. The ALS patient will encounter numerous difficulties in performance of AHT that can be augmented with expert coaching that may occur according to the pace of the patient more easily in a home situation. It is imperative that standardized eFVC and sFVC measurements are obtained using the same coaching technique and the same spirometer interface [Pellegrino 2020]. Professional coaching by respiratory therapists seek to achieve highest quality standards in pulmonary function testing recognizing that the ALS population has potential motor and cognitive limitations [Masa 2011].

The non-randomized sequence of testing in clinic with a conventional spirometer first followed with portable spirometer may have contributed to eFVC obtained with portable spirometry to be lower than FVC obtained with conventional spirometry but other validation conventional-portable spirometer studies have reported similar findings. Respiratory therapists took the utmost care to ensure patient comfort and prevent fatigue, although given the number of tests fatigue may not have been completely avoided. Seated eFVC using both conventional and portable spirometers during the same-day [

Figure 2A] and within 7-day encounter [

Figure 2C] showed no significant difference in FVC supporting reproducibility of measurements obtained with portable spirometry. Supine FVC may reveal early diaphragmatic weakness with or without orthopnea [Lechtzin 2002, Pihtili 2021]. Performance of testing in supine position, with enhanced ability to detect respiratory insufficiency, may be less burdensome when conducted from home with caregiver assistance as more subjects performed sFVC in the home setting.

Stratification of vital capacity according to eFVC % predicted at baseline may allow for the characterization of disease trajectory and FVC trajectory clusters [Chio 2022; Ackrivo 2019, Elamin 2019, Pirola 2019], and prospectively identify an inflection time point estimate of acceleration in FVC decline [Sato 2019]. The result analysis of eFVC and sFVC between clinic visits may allow for earlier detection of respiratory complications according to a cohort membership. Clinicians can recommend individualized frequency of monitoring eFVC and sFVC over time to allow for the initiation of ventilator support in a timely manner. When NIV is not already initiated based on clinical symptomatology or other documentation with nocturnal oximetry of hypoxia, then monthly eFVC and sFVC measurement should be initiated when eFVC is below 80 percent predicted for strategic timing of NIV. Overall, awareness of a decline in eFVC and sFVC enables preparation for impending respiratory failure and promotes both decision-making with advanced directives and the introduction of palliative and hospice care.

The longitudinal tracking of eFVC and sFVC and the determination of rate-of-change from erect to supine (delta e-s FVC) led to the initiation of NIV support at an average eFVC of 65% predicted in 89 veterans with ALS [Elamin 2019]. Cohort membership was based on site of onset, with the observation that the rate of change was variable among different cohorts [Elamin 2019]. AHT may allow for delta FVC to be used for initiating NIV given the increased opportunity to obtain supine studies from home. In our sample population, NIV was initiated based on internet-supervised AHT for patients that did not have access to clinic and would otherwise not have qualified for ventilation support based on Medicare guidelines. This was made possible with remote AHT training, without conventional spirometry.

We present, in this pilot implementation study, evidence that the rate of eFVC decline is greater in ALS subjects in the baseline eFVC stratification < 60 % predicted. We noted that sFVC measurement is more consistently performed by subjects in the home setting and that fewer measurements of sFVC were performed in subjects with the baseline eFVC stratification < 60 %predicted

A practice gap between neuromuscular and pulmonary physicians is fueled by the lack of training opportunities, practice guidelines, and insurance payments for what is a high-effort and time-consuming endeavor [Hansen-Flaschen J 2021]. The ceiling frequency of monthly home monitoring by AHT regardless of patient respiratory status was made on the basis of Medicare billing requirements. Our respiratory therapists and Pulmonologists billed CPT codes 94014, 94015 and 94016 once in a 30-day period. Because the frequency of respiratory testing at-home far exceeded the frequency of in-clinic visits scheduled every 3 months, a greater volume and frequency of respiratory data was generated. The larger number of detectable declines in eFVC led to increased medical decision-making by ALS neurologists anticipating and addressing respiratory compromise with Pulmonologist guidance. The development of the supervised AHT program requires a pre-defined protocol to manage data review requirements and care coordination. The close scrutiny of abnormal and declining vital capacity in ALS is time-sensitive.

The patient records reviewed from this single university hospital-based ALS clinic, together with other publications, increases the knowledge base with heuristic data that internet- supervised AHT may be performed routinely in ALS specialty clinics across the different populations of ALS patients. We showed in this initial pilot implementation study the relative feasibility, accuracy and potential usefulness of internet-supervised telespirometry in the home setting can be integrated into a clinical management structure for ALS patients and currently is approved for medical insurance reimbursement. One of the most dramatic observations from this small study was the recognition between quarterly ALS multidisciplinary clinics of actionable respiratory function patient needs. An unexpected observation was the benefit of accomplishing respiratory function testing in the home setting before the quarterly ALS multidisciplinary clinics. The completion of this task prior to the ALS multidisciplinary clinic allowed more patient time for other clinical issues and reduced clinic-based fatigue that accompanied trying to complete pulmonary function testing during the in-person clinic visit.

5. Conclusions

An evaluation of the benefits of measuring slow vital capacity via internet-supervised AHT is ongoing in a multi-center [NCT05106569] prospective clinical study to ascertain whether frequent surveillance of slow vital capacity from home in a larger set of ALS subjects with internet-supervised AHT will confirm comparable measurement accuracy over time, and lead to better outcomes in relation to use of NIV as well as other clinical devices and provide improvement in overall respiratory care management that minimize patient and caregiver fatigue.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, EIY, DW. and BRB.; methodology, EIY, DW and BRB.; software, DW and BRB.; validation, EIY., DW and BRB.; formal analysis, EIY, DW an BRB.; investigation, EIY.; resources, JC, JM, BN, ER, SH, CC, YF, JM, BS, DM, LD, EB, UD; data curation, EIY and DW.; writing—original draft preparation, EIY, DW. and BRB.; writing—review and editing, EIY, DW. and BRB.; supervision, EIY, DW. and BRB.; project administration, EIY.; funding acquisition, EIY. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported by Tim Green Fund of Upstate Foundation for the purchase of portable spirometers and use of ZephyRx data dashboard. The funding source was not involved in the study design, writing and submission of article for publication. ZephyRx did not fund the analysis or writing of this manuscript. The Upstate University Hospital Neuroscience Institute ALS Research and Treatment Center is recognized by the National Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Association, through a rigorous on-site audit program, as a Certified Treatment Centers of Excellence in Clinical Care and Research. The ALS Center is also part of the Upstate University Hospital Neuroscience Institute Muscular Dystrophy Association Neuromuscular / ALS CARE Program. The ALS Center is a member clinic in the North East ALS (NEALS) Consortium and a actively participating member in the NEALS sponsored HEALEY ALS Platform Trial Program. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Upstate Medical University (IRB 1795328). Patient consent was waived due to retrospective study used de-identified data. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Dr. David McLain Ph.D. for proofreading and editing of the article. The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Ackrivo, J.; Hansen-Flaschen, J.; Wileyto, E.P.; Schwab, R.J.; Elman, L.; Kawut, S.M. Development of a prognostic model of respiratory insufficiency or death in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2019, 53, 1802237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamankar, N.; Coan, G.; Weaver, B.; Mitchell, C.S. Associative Increases in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Survival Duration With Non-invasive Ventilation Initiation and Usage Protocols. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutkove, S.B.; Qi, K.; Shelton, K.; Liss, J.; Berisha, V.; Shefner, J.M. ALS longitudinal studies with frequent data collection at home: study design and baseline data. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2018, 20, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutkove, S.B.; Narayanaswami, P.; Berisha, V.; Liss, J.; Hahn, S.; Shelton, K.; Qi, K.; Pandeya, S.; Shefner, J.M. Improved ALS clinical trials through frequent at-home self-assessment: a proof of concept study. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2020, 7, 1148–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geronimo, A.; Simmons, Z. Evaluation of remote pulmonary function testing in motor neuron disease. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2019, 20, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helleman, J.; Bakers, J.N.E.; Pirard, E.; Berg, L.H.v.D.; Visser-Meily, J.M.A.; Beelen, A. Home-monitoring of vital capacity in people with a motor neuron disease. J. Neurol. 2022, 269, 3713–3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shefner J, Paganoni S, Cudcowicz M, Berry J, Hahn S, Stegmann G, Liss J, Berisha V, Kittle G, Bailey A, Macklin E, on behalf of the HEALEY ALS Platform Trial Study Baseline Speech Assessment and Vital Capacity Measured Remotely and in Clinic in the HEALEY ALS Platform Trial Poster presented at European Network to Cure ALS meeting 22; 216. doi https://www.encals.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Abstracts_ENCALS2022. 20 June.

- Elamin, E.M.; Wilson, C.S.; Sriaroon, C.; Crudup, B.; Pothen, S.; Kang, Y.C.; White, K.T.; Anderson, W.M. Effects of early introduction of non-invasive positive pressure ventilation based on forced vital capacity rate of change: Variation across amyotrophic lateral sclerosis clinical phenotypes. Int. J. Clin. Pr. 2018, 73, e13257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirola, A.; De Mattia, E.; Lizio, A.; Sannicolò, G.; Carraro, E.; Rao, F.; Sansone, V.; Lunetta, C. The prognostic value of spirometric tests in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis patients. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2019, 184, 105456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, E.P.; Drachman, D.B.; Wiener, C.M.; Clawson, L.; Kimball, R.; Lechtzin, N. Pulmonary predictors of survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Use in clinical trial design. Muscle Nerve 2005, 33, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackrivo, J.; Hansen-Flaschen, J.; Jones, B.L.; Wileyto, E.P.; Schwab, R.J.; Elman, L.; Kawut, S.M. Classifying Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis by Changes in FVC. A Group-based Trajectory Analysis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 200, 1513–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, F.; Henderson, R.D.; Morrison, S.C.; Brown, M.; Hutchinson, N.; Douglas, J.A.; Robinson, P.J.; McCombe, P.A. Use of respiratory function tests to predict survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. 2010, 11, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varrato, J.; Siderowf, A.; Damiano, P.; Gregory, S.; Feinberg, D.; McCluskey, L. Postural change of forced vital capacity predicts some respiratory symptoms in ALS. Neurology 2001, 57, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechtzin, N.; Wiener, C.M.; Shade, D.M.; Clawson, L.; Diette, G.B. Spirometry in the Supine Position Improves the Detection of Diaphragmatic Weakness in Patients With Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Chest 2002, 121, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, T.; Van Citters, A.D.; Dowd, C.; Fullmer, J.; List, R.; Pai, S.-A.; Ren, C.L.; Scalia, P.; Solomon, G.M.; Sawicki, G.S. Remote monitoring in telehealth care delivery across the U.S. cystic fibrosis care network. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2021, 20, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panchabhai, T.S.; Cabodevila, E.M.; Pioro, E.P.; Wang, X.; Han, X.; Aboussouan, L.S. Pattern of lung function decline in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: implications for timing of noninvasive ventilation. ERJ Open Res. 2019, 5, 00044–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georges, M.; Golmard, J.-L.; Llontop, C.; Shoukri, A.; Salachas, F.; Similowski, T.; Morelot-Panzini, C.; Gonzalez-Bermejo, J. Initiation of non-invasive ventilation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and clinical practice guidelines: Single-centre, retrospective, descriptive study in a national reference centre. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2016, 18, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, B.L.; Steenbruggen, I.; Miller, M.R.; Barjaktarevic, I.Z.; Cooper, B.G.; Hall, G.L.; Hallstrand, T.S.; Kaminsky, D.A.; McCarthy, K.; McCormack, M.C.; et al. Standardization of Spirometry 2019 Update. An Official American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society Technical Statement. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 200, e70–e88, Sacco 2020 QC Declaration concerning MIR Spirobank Smart spirometers Oct 2020.pdf https://support.zephyrx.com/support/solutions/articles/63000263422-qc-declaration-concerning-mir-spirobank-smart-spirometers. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berlinski, A.; Leisenring, P.; Willis, L.; King, S. Home Spirometry in Children with Cystic Fibrosis. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degryse, J.; Buffels, J.; Van Dijck, Y.; Decramer, M.; Nemery, B. Accuracy of Office Spirometry Performed by Trained Primary-Care Physicians Using the MIR Spirobank Hand-Held Spirometer. Respiration 2012, 83, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quanjer, P.H.; Stanojevic, S.; Cole, T.J.; Baur, X.; Hall, G.L.; Culver, B.H.; Enright, P.L.; Hankinson, J.L.; Ip, M.S.M.; Zheng, J.; et al. Multi-ethnic reference values for spirometry for the 3–95-yr age range: the global lung function 2012 equations. Eur. Respir. J. 2012, 40, 1324–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.R.; Hankinson, J.; Brusasco, V.; Burgos, F.; Casaburi, R.; Coates, A.; Crapo, R.; Enright, P.; Van Der Grinten, C.P.M.; Gustafsson, P.; et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur. Respir. J. 2005, 26, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanjak, M.; Salachas, F.; Frija-Orvoen, E.; Theys, P.; Hutchinson, D.; Verheijde, J.; Pianta, T.; Stewart, H.; Brooks, B.R.; Meininger, V.; et al. Quality control of vital capacity as a primary outcome measure during phase III therapeutic clinical trial in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. 2010, 11, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray D, Rooney J, Al-Chalabi A, Bunte T, Chiwera T, Choudhury M, Chio A, Fenton L, Fortune J, Maidment L, Manera U, Mcdermott C, Meldrum D, Meyjes M, Tattersall R, Torrieri MC, Van Damme P, Vanderlinden E, Wood C, Van Den Berg LH, Hardiman O. Correlations between measures of ALS respiratory function: is there an alternative to FVC? Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2021 Nov;22(7-8):495-504.

- Mayer OH, Finkel RS, Rummey C, Benton MJ, Glanzman AM, Flickinger J, Lindström BM, Meier T. Characterization of pulmonary function in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2015 May;50(5):487-94.

- Czajkowska-Malinowska, M.; Tomalak, W.; Radliński, J. Quality of Spirometry in the Elderly. Adv. Respir. Med. 2013, 81, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampson, N.B.; Kieburtz, K.D.; LeWitt, P.A.; Leinonen, M.; Freed, M.I. Prospective evaluation of pulmonary function in Parkinson's disease patients with motor fluctuations. Int. J. Neurosci. 2016, 127, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turkeshi, E.; Zelenukha, D.; Vaes, B.; Andreeva, E.; Frolova, E.; Degryse, J.-M. Predictors of poor-quality spirometry in two cohorts of older adults in Russia and Belgium: a cross-sectional study. npj Prim. Care Respir. Med. 2015, 25, 15048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.C.; Baxter, M. A comparison of four tests of cognition as predictors of inability to perform spirometry in old age. Age Ageing 2009, 38, 537–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chio, A.; Moglia, C.; Canosa, A.; Manera, U.; Vasta, R.; Grassano, M.; Palumbo, F.; Torrieri, M.C.; Solero, L.; Mattei, A.; et al. Respiratory support in a population-based ALS cohort: demographic, timing and survival determinants. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2022, 93, 1024–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eijk, R.P.; Bakers, J.N.; van Es, M.A.; Eijkemans, M.J.; Berg, L.H.v.D. Implications of spirometric reference values for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2019, 20, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paynter, A.; Khan, U.; Heltshe, S.L.; Goss, C.H.; Lechtzin, N.; Hamblett, N.M. A comparison of clinic and home spirometry as longitudinal outcomes in cystic fibrosis [published online ahead of print, 2021 Aug 30]. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2022, 21, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chio, A.; Moglia, C.; Canosa, A.; Manera, U.; Vasta, R.; Grassano, M.; Palumbo, F.; Torrieri, M.C.; Solero, L.; Mattei, A.; et al. Respiratory support in a population-based ALS cohort: demographic, timing and survival determinants. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2022, 93, 1024–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrieri MC, Manera U, Mora G, et al. Tailoring patients' enrollment in ALS clinical trials: the effect of disease duration and vital capacity cutoffs. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2022;23(1-2):108-115.

- Fallat, R.J.; Jewitt, B.; Bass, M.; Kamm, B.; Norris, F.H. Spirometry in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Arch. Neurol. 1979, 36, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffman, P.L.; Belsh, J.M. Pulmonary Function at Diagnosis of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Chest 1993, 103, 508–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enache, I.; Pistea, C.; Fleury, M.; Schaeffer, M.; Oswald-Mammosser, M.; Echaniz-Laguna, A.; Tranchant, C.; Meyer, N.; Charloux, A. Ability of pulmonary function decline to predict death in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2017, 18, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, F.; Henderson, R.D.; Morrison, S.C.; Brown, M.; Hutchinson, N.; Douglas, J.A.; Robinson, P.J.; McCombe, P.A. Use of respiratory function tests to predict survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. 2010, 11, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiman-Patterson, T.D.; Khazaal, O.; Yu, D.; Sherman, M.E.; Kasarskis, E.J.; Jackson, C.E. ; the PEG NIV study Group Pulmonary function decline in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2021, 22, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourke, S.C.; Tomlinson, M.; Williams, T.L.; Bullock, R.E.; Shaw, P.J.; Gibson, G.J. Effects of non-invasive ventilation on survival and quality of life in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A randomized controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2006, 5, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellegrino, G.M.; Papa, G.F.S.; Centanni, S.; Corbo, M.; Kvarnberg, D.; Tobin, M.J.; Laghi, F. Measuring vital capacity in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Effects of interfaces and reproducibility. Respir. Med. 2020, 176, 106277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masa, J.F.; Gonzalez, M.T.; Pereira, R.; Mota, M.; Riesco, J.A.; Corral, J.; Zamorano, J.; Rubio, M.; Teran, J.; Farre, R. Validity of spirometry performed online. Eur. Respir. J. 2010, 37, 911–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pihtili, A.; Bingol, Z.; Durmus, H.; Parman, Y.; Kiyan, E. Diaphragmatic dysfunction at the first visit to a chest diseases outpatient clinic in 500 patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve 2021, 63, 683–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Iwata, A.; Kurihara, M.; Nagashima, Y.; Mano, T.; Toda, T. Estimating acceleration time point of respiratory decline in ALS patients: A novel metric. J. Neurol. Sci. 2019, 403, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen-Flaschen, J. Respiratory Care for Patients With Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis in the US: In Need of Support. JAMA Neurol. 2021, 78, 1047–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).