Submitted:

30 June 2023

Posted:

30 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Introduction

1.2. Objective and Scope

1.3. Research Question and Hypothesis

1.4. Significance of the Research

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodology

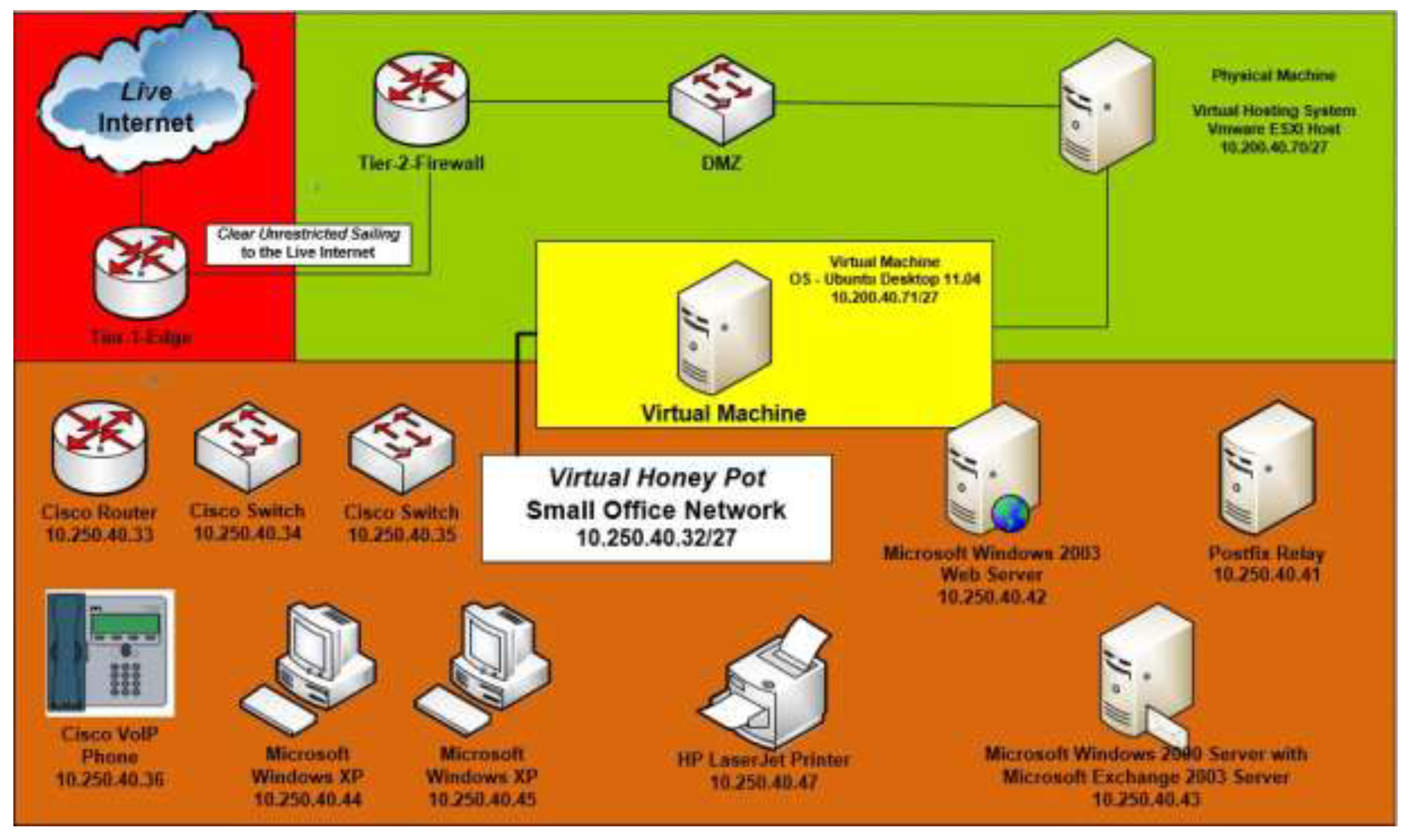

2.2. Data Collection

2.4. Validation

3. Results

3.1. Introduction to Results

3.2. Data Collection and Preprocessing Results

3.2.1. Summary and Descriptive Analysis

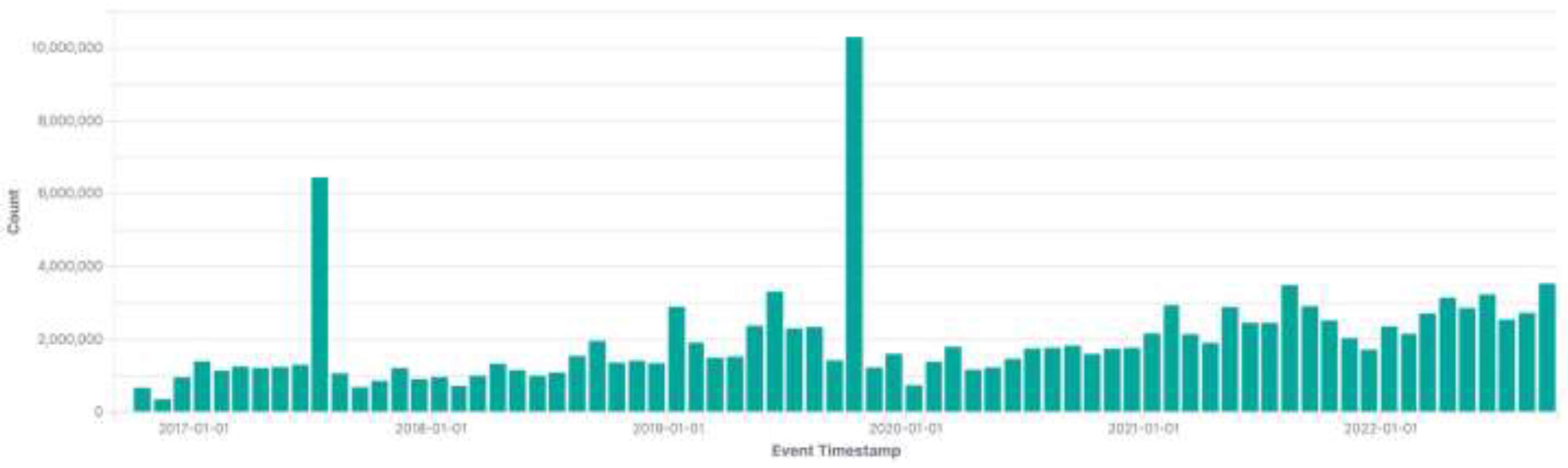

3.2.2. Temporal Analysis

3.2.3. Correlation Analysis

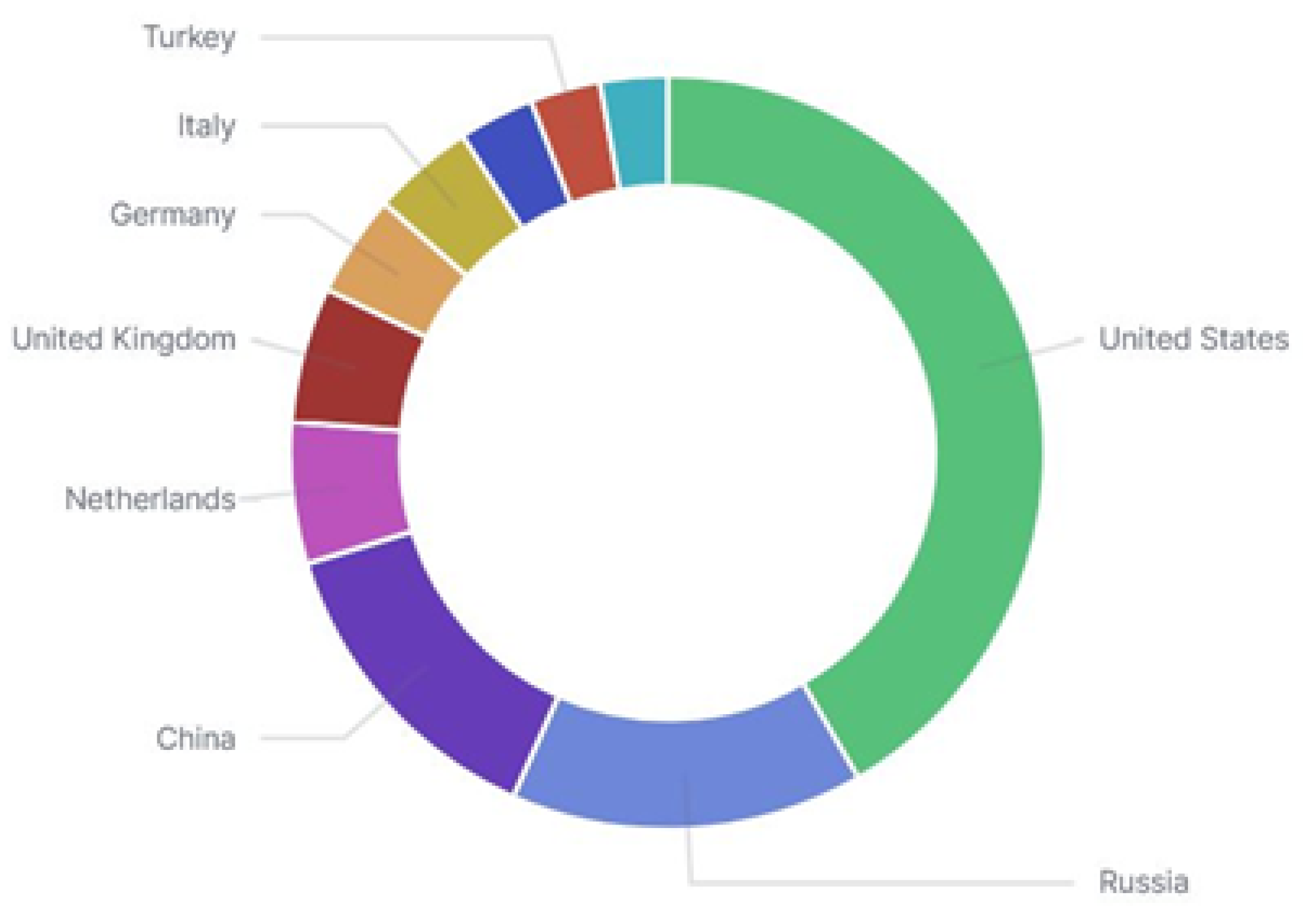

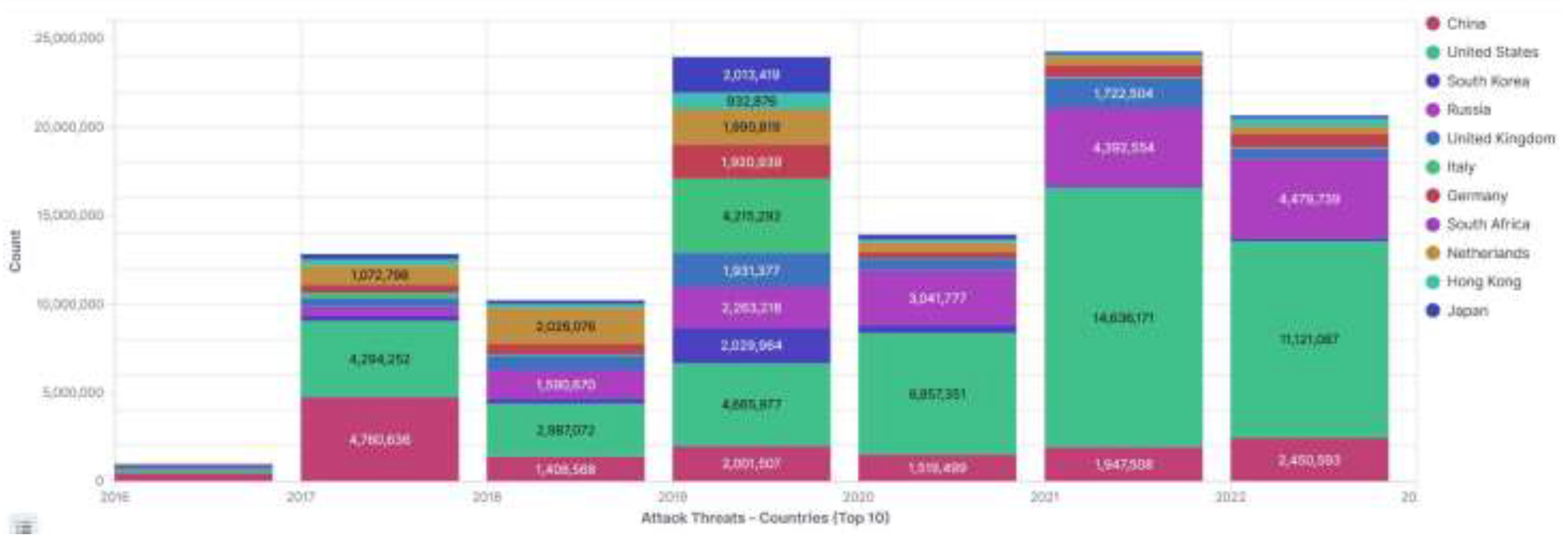

3.2.4. Geographic Analysis

3.2.5. Threat Intelligence Analysis

3.2.6. Source IP Address Analysis

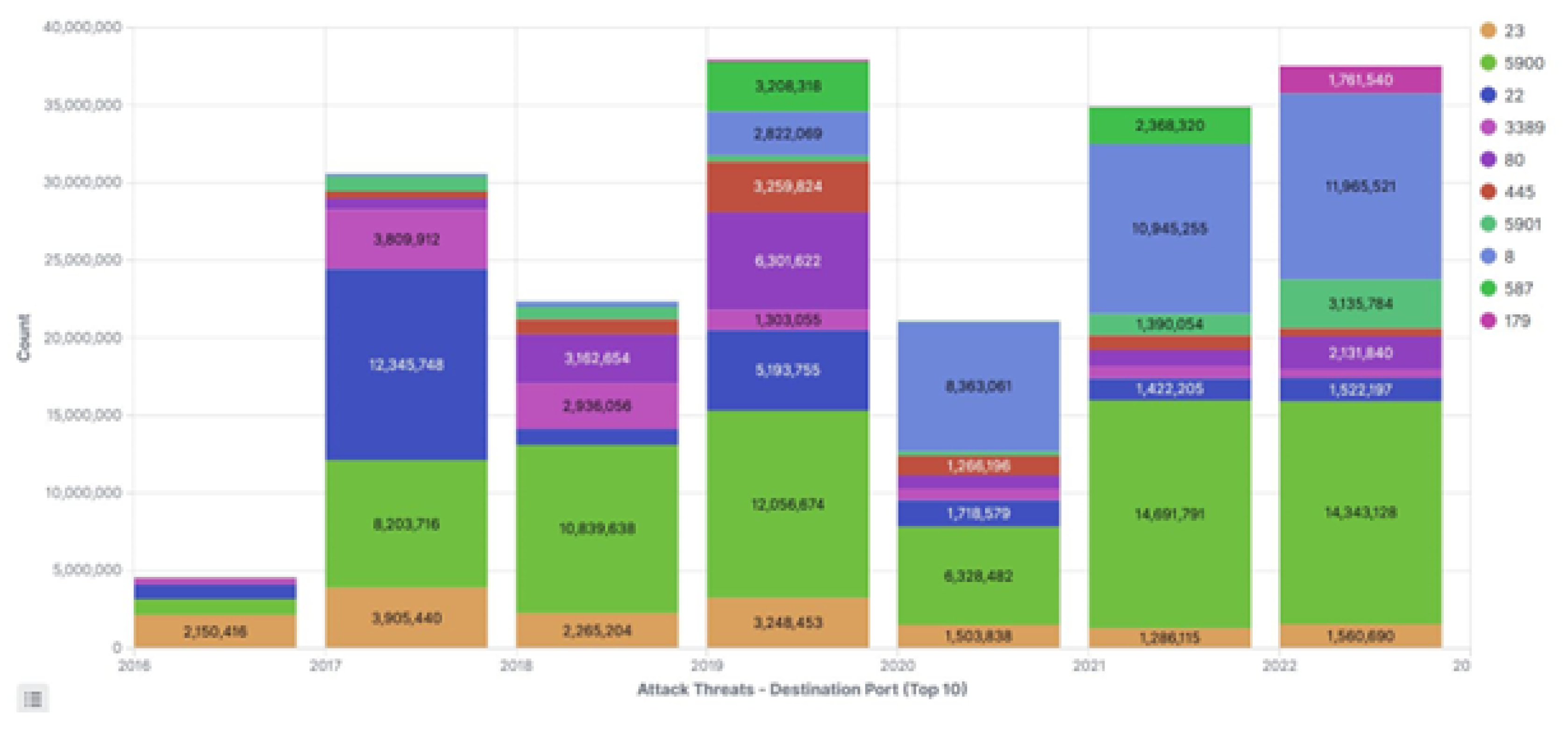

3.2.7. Destination Ports Analysis

3.2.8. Destination Services Analysis

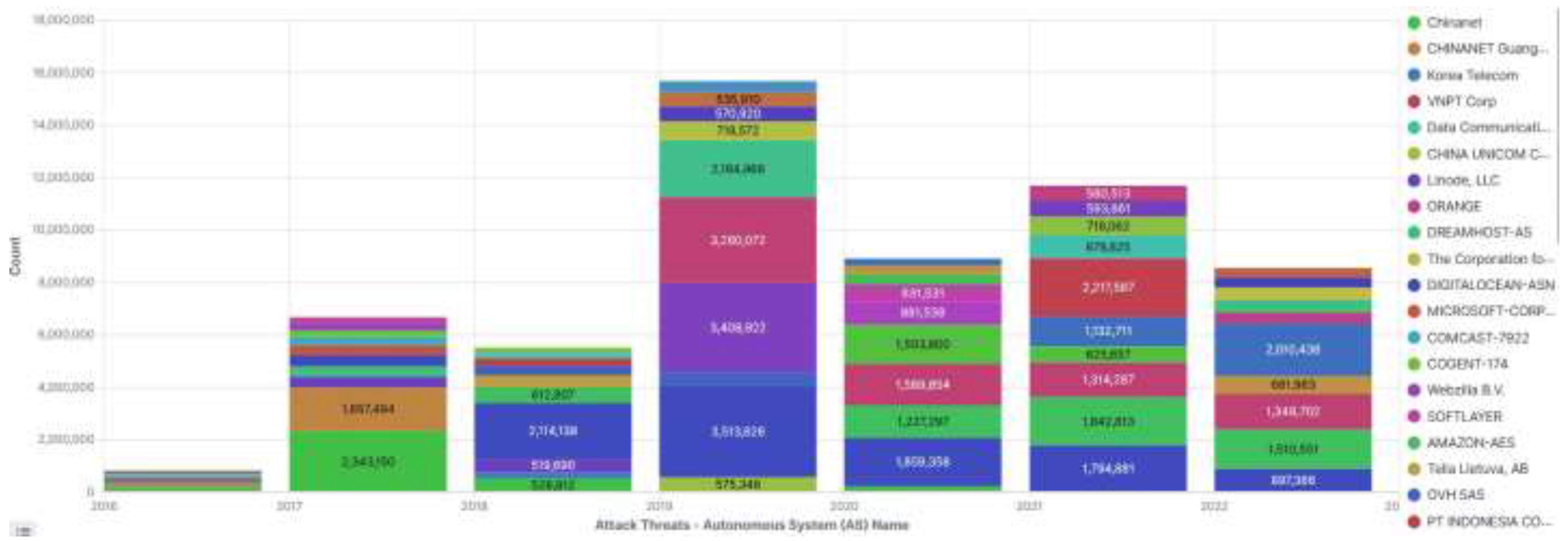

3.2.9. Autonomous System Numbers and Names Analysis

3.2.10. Behavior Analysis

3.2.11. Clustering Analysis

- From October 2016 to June 2017, all instances were part of cluster 2 and were not identified as anomalies.

- July 2017 exhibited a substantially higher attack count, forming cluster 0, yet was not designated as an anomaly.

- Attack counts returned to lower levels similar to pre-July 2017, forming part of cluster 2 with no anomalies detected through to the end of 2018.

- From 2019 to 2020, attack counts similar to those of July 2017 were noted, forming part of cluster 0. These instances were not marked as anomalies, indicating these levels of aggression were more common during this period.

- An anomaly was detected in October 2019, with an attack count significantly higher than surrounding months.

- From 2021 onwards, the attack counts remained high and were classified into cluster 1, with no anomalies detected during this period.

3.2.12. Anomaly Detection with Clustering

- The attack count was consistently high in Cluster 2 from October 2016 until September 2018, after which a significant anomaly occurred in July 2017 with a sudden surge to 3,001,792.

- Cluster 0 dominated the attack landscape from October 2018 through to September 2019, except for a spike to 5,032,632 in October 2019, which was categorized as Cluster 1 and marked as an anomaly.

- From October 2019 onwards, Cluster 0 and 1 have alternated, with exceptionally high attack counts associated with Cluster 1.

3.3. Validation of Results

3.4. Summary of Results

4. Discussion Section

4.1. Introduction

4.2. Interpretation of Results

4.3. Data Collection and Preprocessing

4.3.1. Descriptive Analysis

4.3.2. Temporal Analysis

4.3.3. Correlation Analysis

4.3.4. Geographic Analysis

4.3.5. Threat Analysis

4.3.6. Source IP Address Analysis

4.3.7. Destination Ports Analysis

4.3.8. Destination Services Analysis

4.3.9. Autonomous System Numbers and Names Analysis

4.3.10. Behavior Analysis

4.3.11. Clustering Analysis

4.3.12. Anomaly Detection with Clustering

4.4. Comparison to Previous Research

4.5. Practical Implications and Recommendations

- Utilizing Cluster Analysis for Network Traffic: As revealed by cluster analysis, the diversity in network behavior patterns underscores the need for flexible and adaptive security measures. By identifying which cluster a particular network behavior falls into, practitioners can apply security measures tailored to that cluster's characteristics.

- Temporal Monitoring of Network Traffic: The time-series analysis of attack counts emphasized the criticality of time-based network traffic monitoring. Recognizing periods of heightened anomaly occurrence can guide timely interventions, possibly preventing potential attacks.

- Behavior Score as an Indicator: A behavior score is a powerful tool for quantifying potential anomalies. Organizations can incorporate this scoring system into their network monitoring routines to help identify abnormal behavior that may pose a security threat. Regular re-evaluation and adjustment of the scoring system, based on evolving network patterns, are recommended to maintain its effectiveness.

- Geographical and Autonomous System Analysis: The high frequency of anomalies originating from specific geographical locations and autonomous systems suggests that these aspects cannot be ignored while assessing network security. Enhanced monitoring and possibly stricter security measures could be considered for traffic from identified high-risk areas and systems.

- Proactive and Holistic Approach: The findings suggest a proactive and holistic approach to network security is necessary. This involves responding to threats as they occur and continuously monitoring, learning from the data, and anticipating potential vulnerabilities.

4.6. Limitations and Future Research

- Limited Scope of Network Data: The data used in this study came from a specific network, which might have unique characteristics not universally applicable to all networks. Future research could broaden the scope by including data from multiple networks varying in size, nature, and location to increase the generalizability of the results.

- Temporal Constraints: The analysis was performed on historical data. The dynamic nature of network behavior and evolving cyber threats may render some identified patterns less relevant over time. Continuous monitoring and time-series analysis are thus needed to keep the findings updated.

- Binary Classification of Anomalies: The current study classifies network behavior as normal or abnormal without further categorizing the nature of the anomalies. Future research could focus on classifying different types of irregularities, which could provide more nuanced insights into the behavior patterns associated with different kinds of threats.

- Solely Quantitative Approach: This study employed a predominantly quantitative approach. Future research could benefit from integrating qualitative methods, such as expert opinions or case studies, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of network anomalies and associated threats.

- Overlooked Factors: This study did not incorporate factors such as the type of network protocol, the application associated with the network traffic, and specific details about the source and target systems. Including these factors could provide additional dimensions to the analysis, leading to richer and more detailed insights.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Summary of Main Findings

- Geographic Analysis: The study established that the source country of IP addresses significantly affects the behavior score, indicating potential network anomalies. A clear association between specific countries, notably the United States, Germany, and China, and higher behavior scores were identified.

- Organizational Analysis: In the context of the Autonomous System Numbers (ASNs) and associated organization names, the research discovered specific organizations, such as 'DigitalOcean-ASN,' 'F3 Netze e.V.', and 'Zwiebelfreunde e.V.,' were frequently linked to IP addresses with high behavior scores. This finding points towards the relevance of considering ASNs and organizational information in network anomaly detection.

- Behavioral Analysis: The data-driven behavior scoring mechanism developed in this study revealed that a higher frequency of connection requests was often associated with higher behavior scores. In addition, the analysis demonstrated that the proportion of abnormal behavior was higher in certain source countries and organizations.

- Validation of Results: The results were validated using cross-validation techniques, confirming the findings' robustness. It also emphasized the importance of constant updates and recalibrations of the models as cyber threats evolve.

5.2. Contributions to the Field

- Integrative Anomaly Detection Approach: The study provides a novel integrative approach to network anomaly detection, combining geographic, organizational, and behavioral elements into a unified framework. This holistic model acknowledges network anomalies' complex, multifaceted nature, setting a new standard for future studies in this area.

- Expanded Geographical and Organizational Context: By highlighting the role of the source country and the associated organization in network anomalies, the study underscores the importance of context in cybersecurity analysis. It demonstrates the value of considering these often-overlooked factors and adds a new dimension to our understanding of network behaviors.

- Behavior Scoring Mechanism: The introduction and validation of a data-driven behavior scoring mechanism represents a significant methodological contribution. This mechanism quantifies anomalous behavior and provides a benchmark for comparing and predicting anomalies.

- Robust Validation Process: The study's validation process provides a rigorous framework for evaluating the performance of anomaly detection systems, contributing to the methodological rigor of the field. Utilizing cross-validation techniques, this process is an essential model for future research.

- Empirical Evidence: The study offers robust empirical evidence, demonstrating transparent relationships between geographic, organizational, and behavioral characteristics and network anomalies. This practical grounding enriches the theoretical basis of the field and provides real-world applicability to the findings.

5.3. Practical Implications

- Enhanced Network Monitoring: Integrating geographic, organizational, and behavioral elements into a single anomaly detection framework provides a more multifaceted understanding of network behavior. This enhanced perspective can inform real-time network monitoring and improve the identification and response to potential threats.

- Risk Assessment and Management: The behavior scoring mechanism developed in this study allows for quantitative assessment of network anomalies, providing an invaluable tool for risk management. With this approach, organizations can prioritize resources based on the severity and frequency of identified anomalies.

- Tailored Cybersecurity Strategies: By acknowledging the role of geographic and organizational context in network anomalies, this study empowers organizations to develop tailored cybersecurity strategies. For instance, organizations could apply stricter controls or more rigorous monitoring for network traffic from countries or organizations associated with higher behavior scores.

- Benchmarking and Predictive Analysis: This research validated the scoring mechanism and offers a standard measure for network anomalies. This benchmark can compare network behaviors across time and context, aiding predictive analysis and allowing organizations to proactively anticipate and respond to potential threats.

- Cybersecurity Training and Education: The insights derived from this study can be integrated into cybersecurity training programs, enhancing awareness about the complex nature of network anomalies. The scoring mechanism can serve as a teaching tool, helping practitioners understand how multiple elements can contribute to abnormal behaviors.

5.4. Potential Areas for Future Research Include

- Further Refinement of the Scoring Mechanism: While the behavior scoring mechanism employed in this study has proven useful, further refinement may lead to even more accurate anomaly detection. Machine learning algorithms could be incorporated to refine the scoring algorithm dynamically based on evolving network behaviors.

- Longitudinal Study: This research is essentially a snapshot of network anomalies at a particular time. Future research should continue to examine network behavior over an extended period to identify any emerging temporal patterns or trends.

- Individual vs. Organizational Behavior: This study has focused on anomalies at an aggregate level. Future research might delve into whether different types of organizations (e.g., based on industry, size, or geography) exhibit different patterns of network anomalies. Similarly, individual user behaviors within organizations could be studied to identify potential insider threats.

- Comparison Across Different Network Types: This research has used a dataset from a specific type of network. A valuable direction for future research could be to replicate this study using data from different networks (e.g., corporate networks, IoT networks) to examine whether similar patterns emerge.

- Integration of Additional Data Sources: Integrating other open-source intelligence data, such as cyber threat intelligence feeds, with the analyzed network data might provide richer context and enable more accurate anomaly detection.

- Implications for Cybersecurity Policy and Regulation: Building on the findings of this study, future research could explore the impact on cybersecurity policy and regulation. For instance, how might insights on geographic and organizational factors inform policy decisions related to cross-border data flows or industry-specific cybersecurity regulations?

5.5. Regarding Future Research Directions

- Adaptation to Evolving Cyber Threat Landscape: The cyber threat landscape is evolving rapidly, and future research needs to adapt to these changes. Emerging threats, such as those targeting cloud environments, artificial intelligence, and Internet of Things (IoT) devices, require unique approaches to anomaly detection.

- Leveraging AI and Machine Learning: The use of advanced artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning techniques for anomaly detection offers a promising area for future exploration. This could include the application of deep learning, reinforcement learning, or other AI techniques to improve the effectiveness of anomaly detection.

- Integration of Threat Intelligence: Integrating threat intelligence with anomaly detection could significantly improve identifying and responding to threats. Future research could explore how threat intelligence can be effectively incorporated into anomaly detection systems.

- Focus on Privacy-Preserving Anomaly Detection: With the increasing importance of privacy, future research should focus on developing anomaly detection techniques that respect user privacy. Techniques such as differential privacy or federated learning could be investigated.

- Investigating the Human Factor: The role of the human factor in cybersecurity is often overlooked. Future research could explore how human behavior impacts the effectiveness of anomaly detection and what steps can be taken to improve user awareness and behavior.

- Advancing Regulatory Frameworks: As this study indicates, cybersecurity is a global concern. Therefore, increasing the understanding of regulatory and policy frameworks for anomaly detection on a global scale could be another promising future research direction.

5.6. Final Thoughts

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Farokhnia Hamedani, M. Essays on Cybersecurity and Information Privacy. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, University of South Florida, 2023. 30421027. [Google Scholar]

- Rosa, F.R. Global Internet Interconnection Infrastructure: Materiality, Concealment, and Surveillance in Contemporary Communication. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, American University, 2019. 13902857. [Google Scholar]

- Adewopo, V. Exploring Open Source Intelligence for Cyber Threat Prediction. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, University of Cincinnati, 2021. 28890231. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, S. Tackling Network-Level Adversaries Using Models and Empirical Observations. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, State University of New York at Stony Brook, 2021. 28718487. [Google Scholar]

- Muoi, T.D. Handling Network Attacks Exploiting Routing Information Asymmetries. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, National University of Singapore (Singapore), 2022. 29352339. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G. An Empirical Analysis on Threat Intelligence: Data Characteristics and Real-World Uses, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, University of California, San Diego, 2020. 27955013.

- Hillis, J.S. Enterprise Advanced Persistent Threat Group Identification and Technique Discovery, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, Marymount University, 2023. 30484790.

- Alsarhan, H.F. Real-Time Machine Learning-based Intrusion Detection System (IDS) for Internet of Things (IoT) Networks. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, The George Washington University, 2023. 30000678. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Haija, Q.A.; Krichen, M.; Elhaija, W.A. Machine-Learning-Based Darknet Traffic Detection System for IoT Applications. Electronics 11, 556. [CrossRef]

- Luitel, A. A Framework for Modeling Data Breach Risk Using Machine Learning Models for High-Dimensional Panel Data, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, The George Washington University, 2022. 28865998.

- Ongun, T. Resilient Machine Learning Methods for Cyber-Attack Detection. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, Northeastern University, 2023. 30418436. [Google Scholar]

- Mengidis, N.; Panagiotou, P.; Tsikrika, T.; Vrochidis, S.; Kompatsiaris, I. Host-based Intrusion Detection Using Signature-based and AI-driven Anomaly Detection Methods. Information & Security 50, 37–48. [CrossRef]

- Panagiotou, P.; Mengidis, N.; Tsikrika, T.; Vrochidis, S.; Kompatsiaris, I. An in Depth Analysis of Open Source Tools: Host Intrusion Detection System, Intrusion Detection System, and Honeypots, and How They Can Protect a SME’s Network. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, Utica College, 2019. 22622076. [Google Scholar]

- Butt, S.M.; Reaiche, C. Cognitive Analysis of Intrusion Detection System. Journal of Siberian Federal University. Engineering & Technologies 15, 102–120. [CrossRef]

- Barron, T. Addressing the Imbalance between Attackers and Defenders Using Cyber Deception. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, State University of New York at Stony Brook, 2020. 28091212. [Google Scholar]

- Bobish, M. Sharing Cyber Threat Information Between the United States’ Public and Private Sectors. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, Utica University, 2023. 30488959. [Google Scholar]

- Alowaisheq, E. Security Traffic Analysis Through the Lenses Of: Defenders, Attackers, and Bystanders. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, Indiana University, 2020. 28259642. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, S. Network Intrusion Detection and Deep Learning Mechanisms. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, Florida Atlantic University, 2023. 30417958. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, Y.; Kim, K. Comparison of Anomaly Detection Accuracy of Host-based Intrusion Detection Systems based on Different Machine Learning Algorithms. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications 11, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Hu, Y. Research on Attributes Reduction Method of Intrusion Detection Data Based on Rough Set Theory. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboah Boateng, E. Unsupervised Machine Learning Methods for Detecting Process Control Anomalies in Industrial Control Systems, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, Tennessee Technological University, 2023. 30313772.

- Moore, K.E. Analyzing Small Business Strategies to Prevent External Cybersecurity Threats. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, Walden University, 2023. 30424695. [Google Scholar]

- Moriano Salazar, P. Anomaly Detection in Real-World Temporal Networks. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, Indiana University, 2019. 13865635. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, I.J., Jr. Maintaining Small Retail Business Profitability by Reducing Cyberattacks. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, Walden University, 2020. 28024279. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, T. The Role of Stress among Cybersecurity Professionals. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, The University of Alabama, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Descriptive Statistics | |

|---|---|

| count | 2191.000000 |

| mean | 45741.001826 |

| std | 58788.500082 |

| min | 0.000000 |

| 25% | 16037.000000 |

| 50% | 28447.000000 |

| 75% | 58430.500000 |

| max | 888203.000000 |

| Column 1 | Column 2 | Correlation | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| malicious-subnet-misp-bro.txt | malicious-subnet-misp-ip-dst.txt | 1 | 0 |

| malicious-ip-uceprotect-dnsbl-3.txt | malicious-ip-uceprotect-dnsbl-2.txt | 1 | 0 |

| malicious-ip-firehol-anonymous.txt | malicious-ip-firehol-proxies.txt | 0.987332677 | 0 |

| malicious-ip-dan-torlist-exit-ip.txt | malicious-ip-dan-torlist.txt | 0.933264363 | 0 |

| malicious-ip-blocklist-ssh.txt | malicious-ip-blocklist.txt | 0.880540508 | 0 |

| malicious-subnet-spamhaus-drop.txt | malicious-subnet-snort-pulled-pork.txt | 0.845672856 | 0 |

| malicious-subnet-snort-pulled-pork.txt | malicious-subnet-firehol-spamhaus_drop.txt | 0.845672856 | 0 |

| malicious-ip-firehol-webclient.txt | malicious-ip-firehol-webserver.txt | 0.822205602 | 0 |

| malicious-ip-misp-bro-ipv4.txt | malicious-ip-misp-ip-dst-ipv4.txt | 0.784329101 | 0 |

| malicious-subnet-firehol-anonymous.txt | malicious-subnet-firehol-proxies.txt | 0.783025671 | 0 |

| Threat Intelligence Feed or Repository | Matches | Total Source IP |

|---|---|---|

| malicious-subnet-uceprotect-dnsbl-3.txt | 581,115 | 44.138% |

| malicious-subnet-uceprotect-dnsbl-2.txt | 300,891 | 22.854% |

| malicious-subnet-firehol-webserver.txt | 91,983 | 6.986% |

| malicious-ip-misp-ip-dst-ipv4.txt | 41,701 | 3.167% |

| malicious-ip-misp-bro-ipv4.txt | 28,080 | 2.133% |

| Source IP | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 23.139.224.114 | 2,217,585 | 2.215% |

| 162.142.125.128 | 1,045,622 | 1.044% |

| 100.27.42.150 | 758,851 | 0.758% |

| 100.27.42.187 | 754,386 | 0.754% |

| 100.27.42.157 | 693,224 | 0.693% |

| 64.227.110.98 | 687,625 | 0.688% |

| 92.63.197.18 | 677,060 | 0.677% |

| 143.110.156.7 | 580,346 | 0.580% |

| 161.35.232.85 | 569,259 | 0.569% |

| 93.115.29.34 | 531,990 | 0.532% |

| Source-IP | Source-Country | Source-AS-Org-Name | Behavior Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 185.220.103.9 | United States | CALYX-AS | 136 | |

| 95.85.7.220 | United States | DIGITALOCEAN-ASN | 136 | |

| 60.191.87.89 | China | CT-HangZhou-IDC | 136 | |

| 23.129.64.216 | United States | EMERALD-ONION | 120 | |

| 171.25.193.80 | Sweden | Foreningen for digitala fri- och rattigheter | 120 | |

| 199.249.230.87 | United States | QUINTEX | 120 | |

| 92.255.85.9 | Russia | Chang Way Technologies Co. Limited | 120 | |

| 83.229.82.236 | Netherlands | Kamatera Inc | 120 | |

| 66.102.248.138 | United States | Chinanet | 105 | |

| 60.9.97.113 | Mongolia | CHINA UNICOM China169 Backbone | 105 | |

| 89.190.159.189 | South Africa | Alsycon B.V. | 105 |

| Behavior Score | Count |

|---|---|

| 0 | 617042 |

| 1 | 368742 |

| 3 | 269550 |

| 6 | 36685 |

| 10 | 13606 |

| 15 | 4606 |

| 21 | 2571 |

| 36 | 1280 |

| 28 | 1222 |

| 45 | 628 |

| 55 | 306 |

| 66 | 151 |

| 78 | 77 |

| 91 | 49 |

| 105 | 34 |

| 120 | 25 |

| 136 | 11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).