Submitted:

30 June 2023

Posted:

30 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

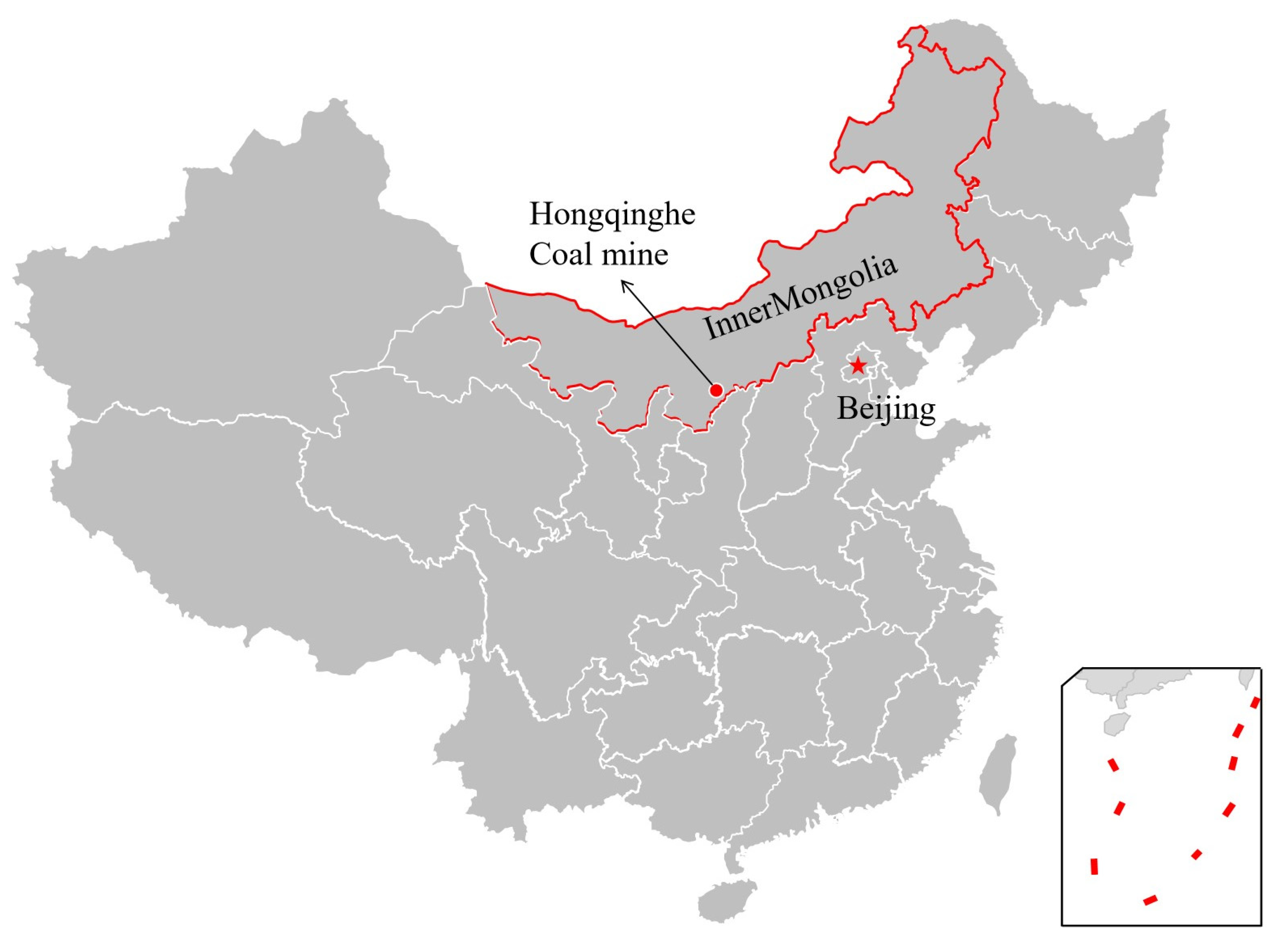

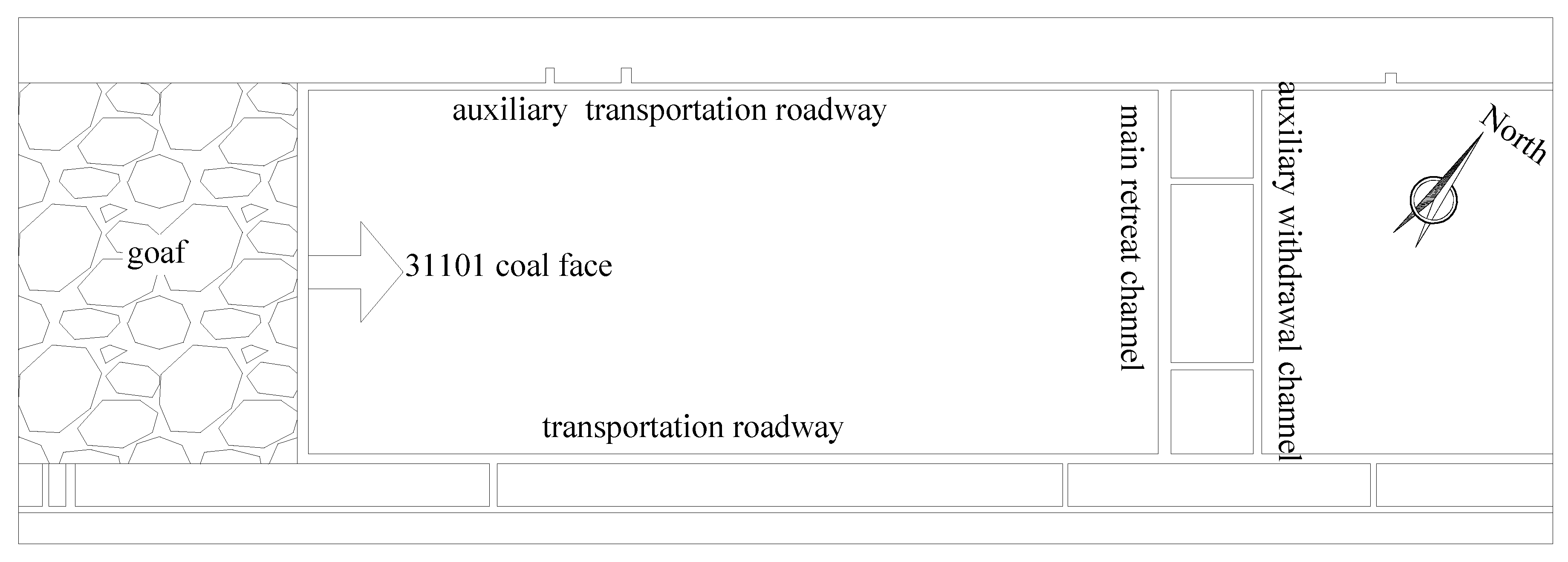

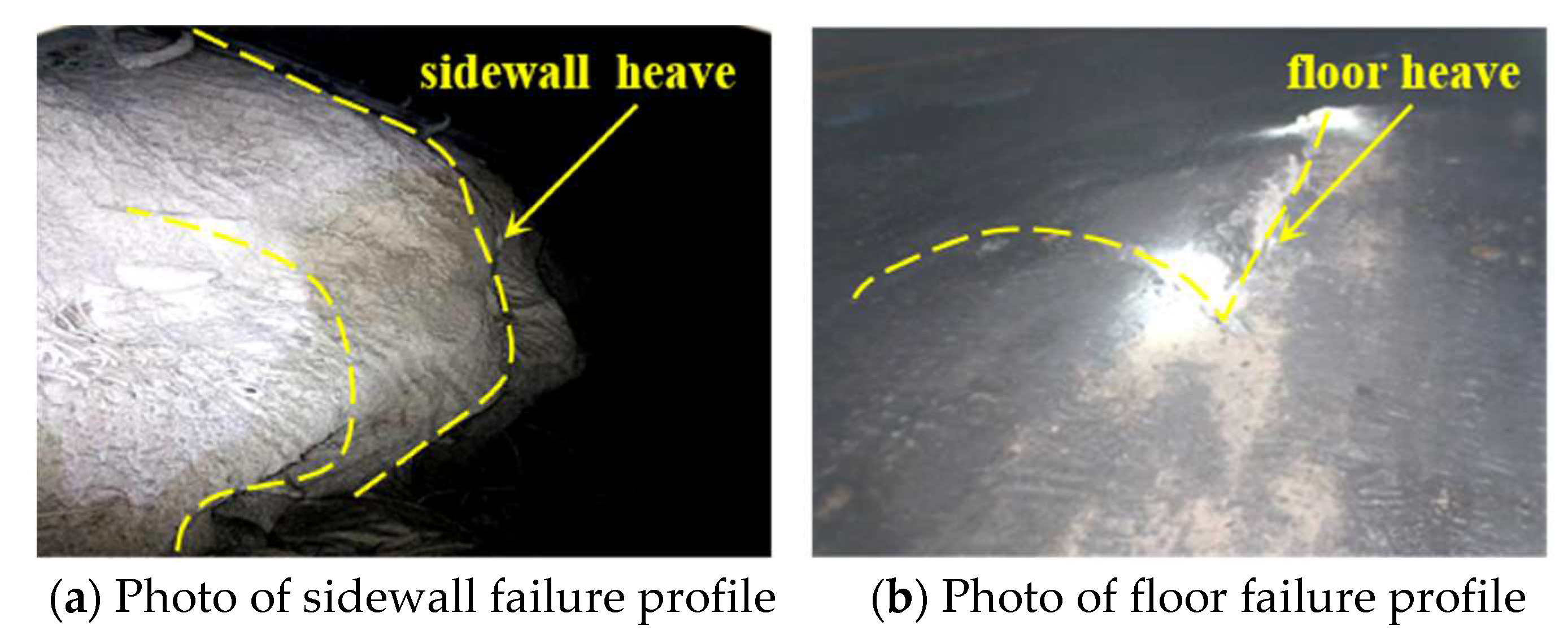

2. Analysis of engineering situations

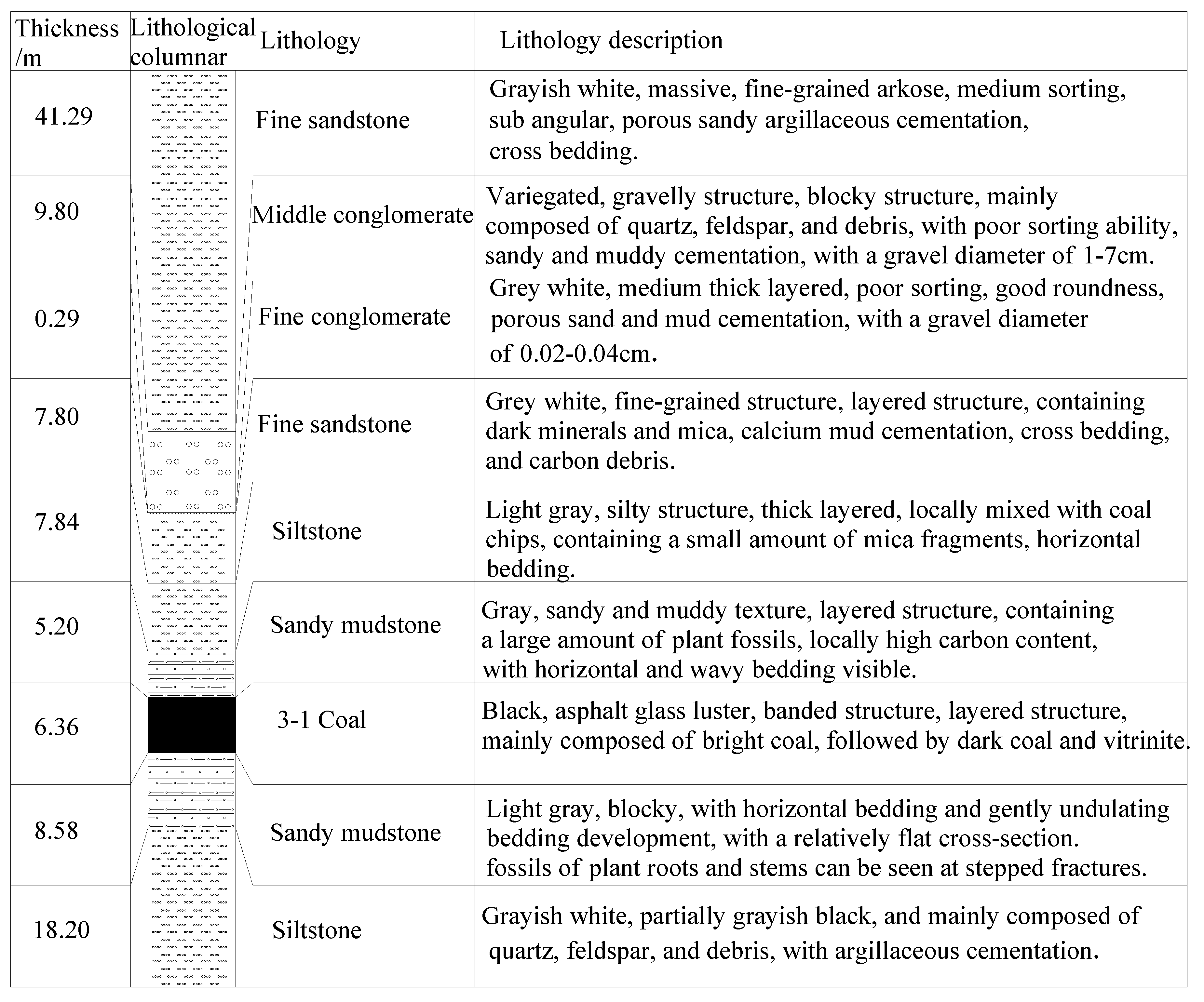

2.1. Engineering geology

2.2. Support parameters and solutions

- Roof support adopts 6 left-hand threaded steel longitudinal bolts, the specification isφ22mm ×L 2400mm, and the row and column spacing is 1000 mm ×1000 mm. Adopting arch-shaped high-strength tray, with a steel grade of no less than Q235 and a specification of 150 mm × 150 mm × 10mm, with an arch height of not less than 34mm, equipped with self-aligning ball pads and drag-reducing nylon washers.

- Sidewall support adopts 5 bolts, and the row and column spacing is 850 mm×1000 mm, and whose parameters are the same as the roof. The sidewall hangs 16# wire braided metal diamond mesh with a size of 5800 mm×1100 mm.

- The floor is supported by two bolts and each bolt is fitted with two resin cartridges of MSSK2350 and MSK2350. The pretension force is not less than 300 N.m.

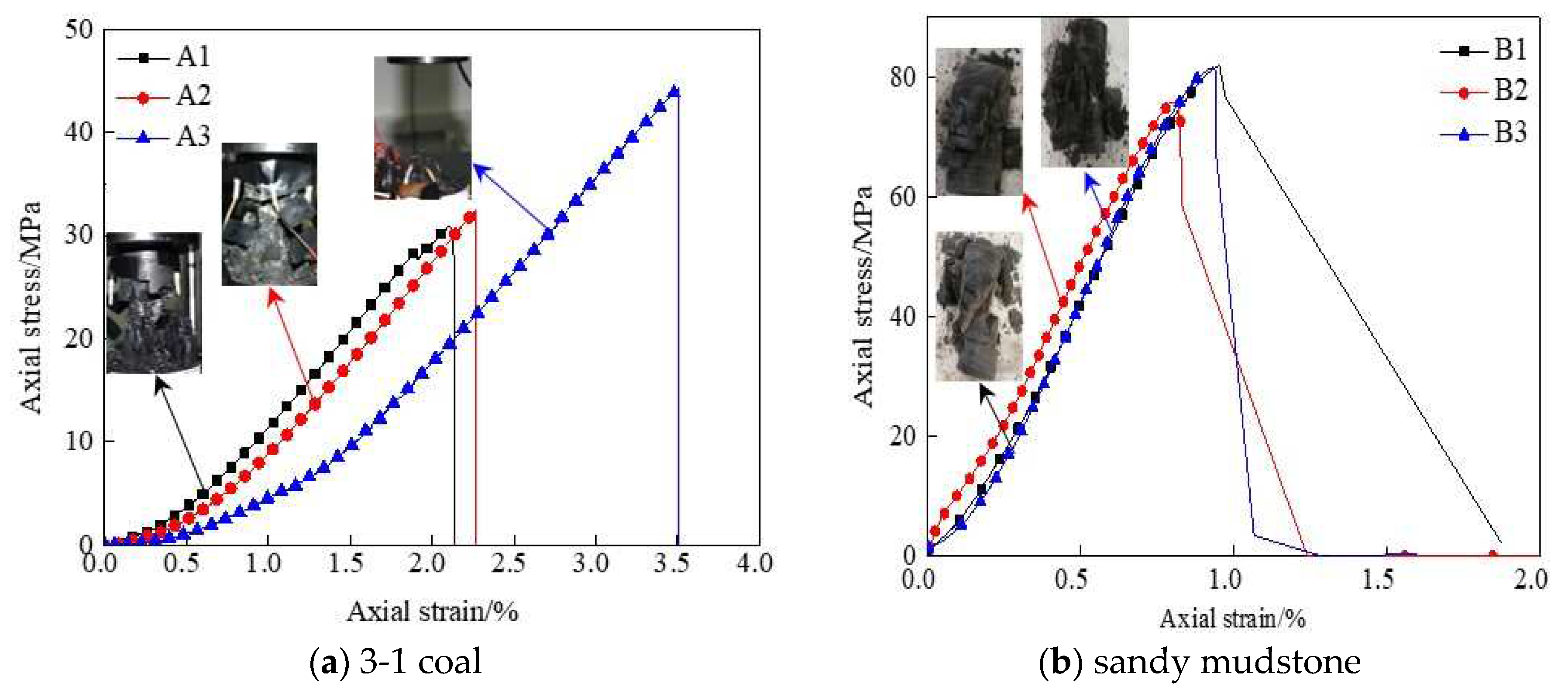

3. Laboratory experiments

3.1. Determination of long-term strength of coal and rock

- By creep test. In this method, the long-term strength of rock is determined by creep experiments which are roughly equivalent to the softening critical load.

- By empirical formula: The calculation formula reads:

3.2. Mineral composition and microstructure of deep surrounding rocks

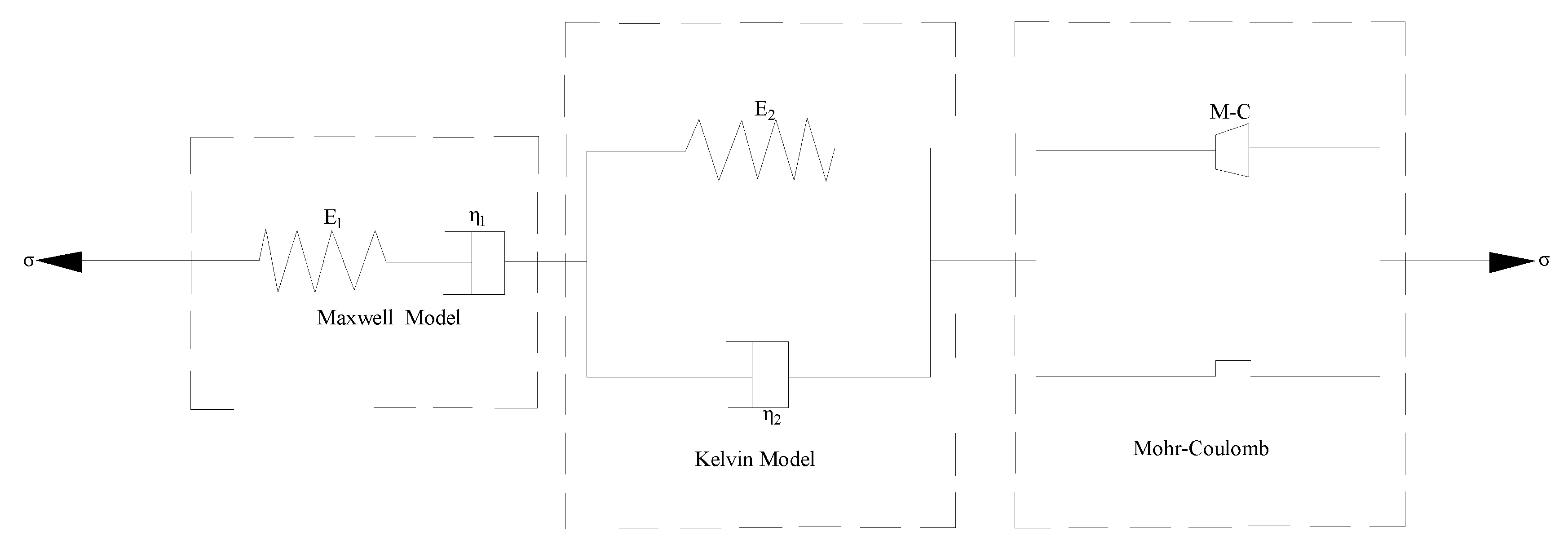

4. Cvisc creep numerical simulation

4.1. Elasto-viscoplastic creep constitutive model

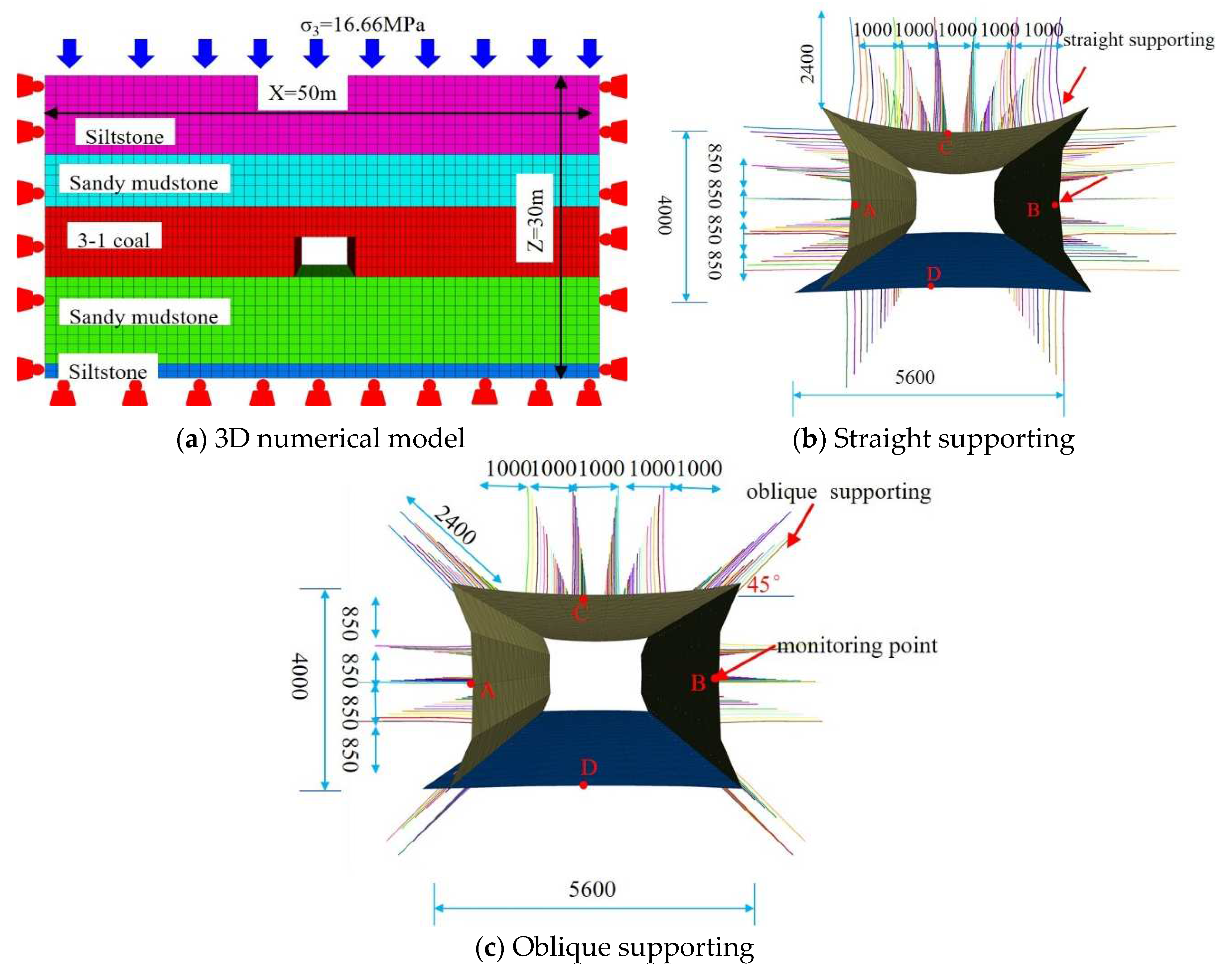

4.2. Numerical model description

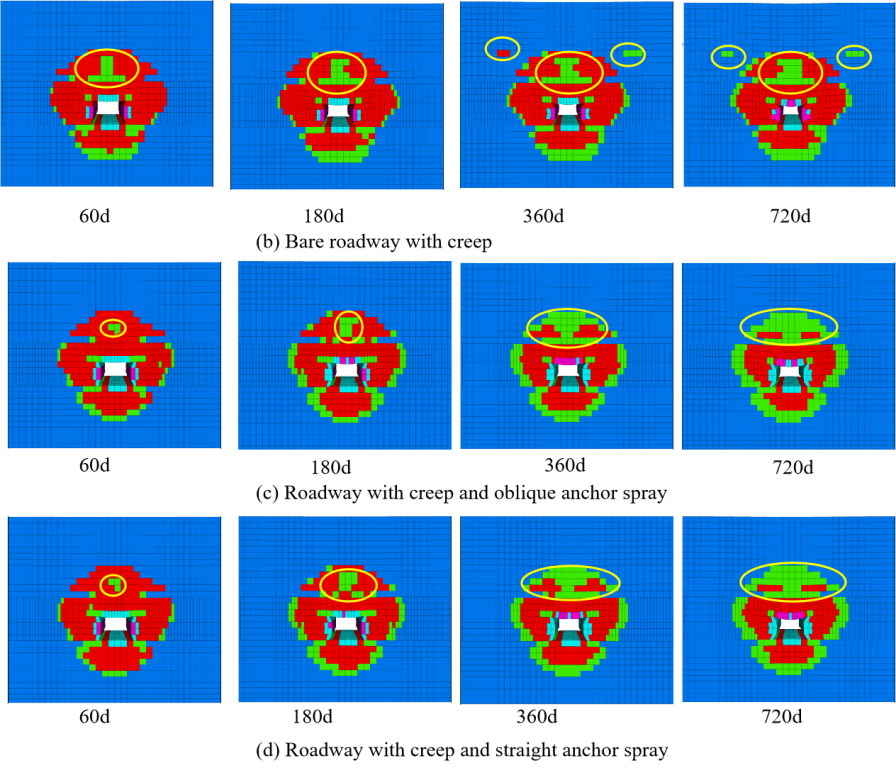

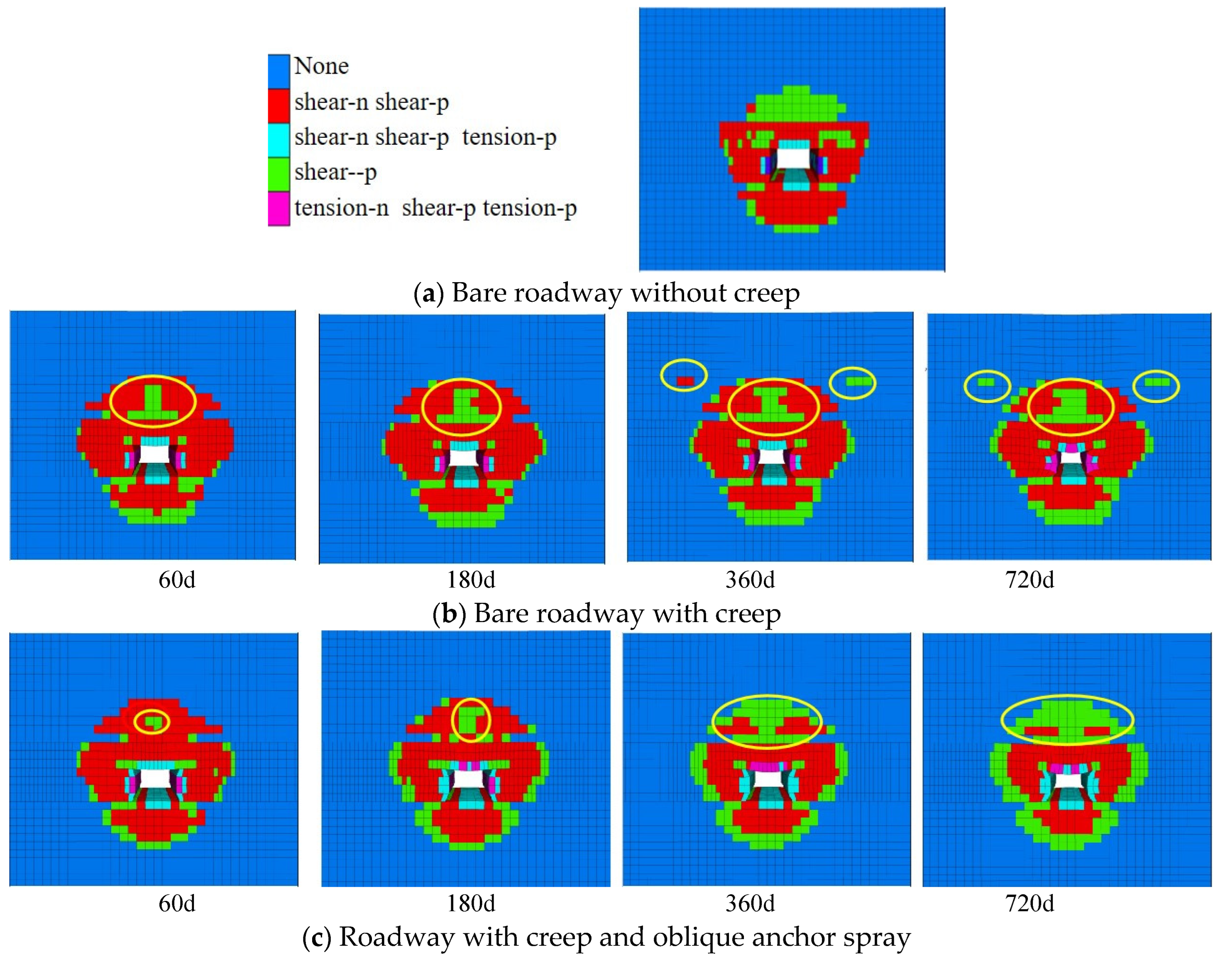

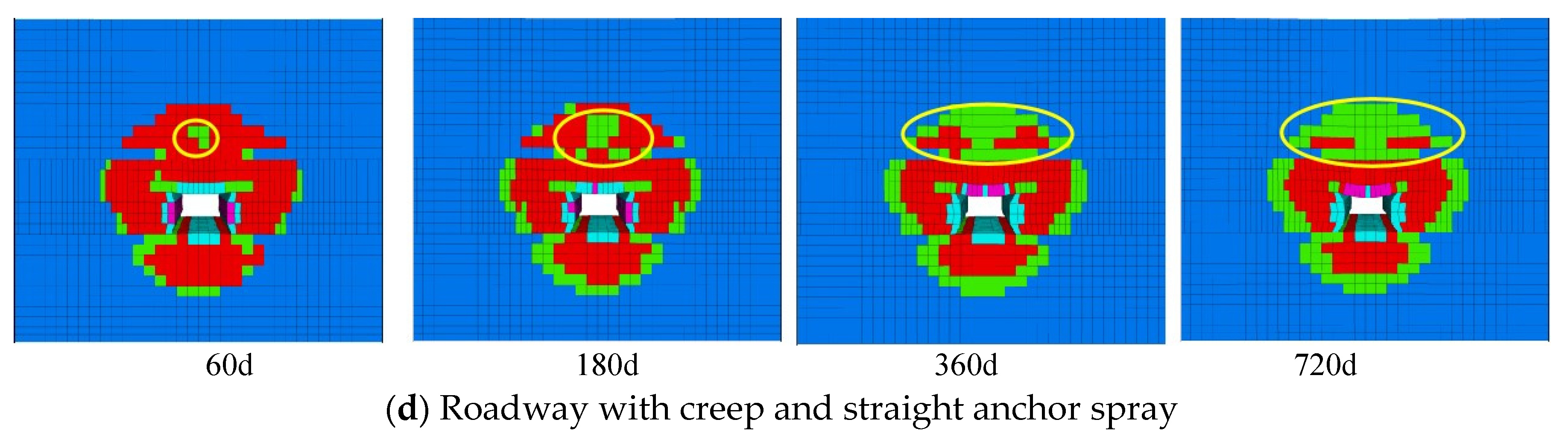

4.3. Analysis of plastic zone

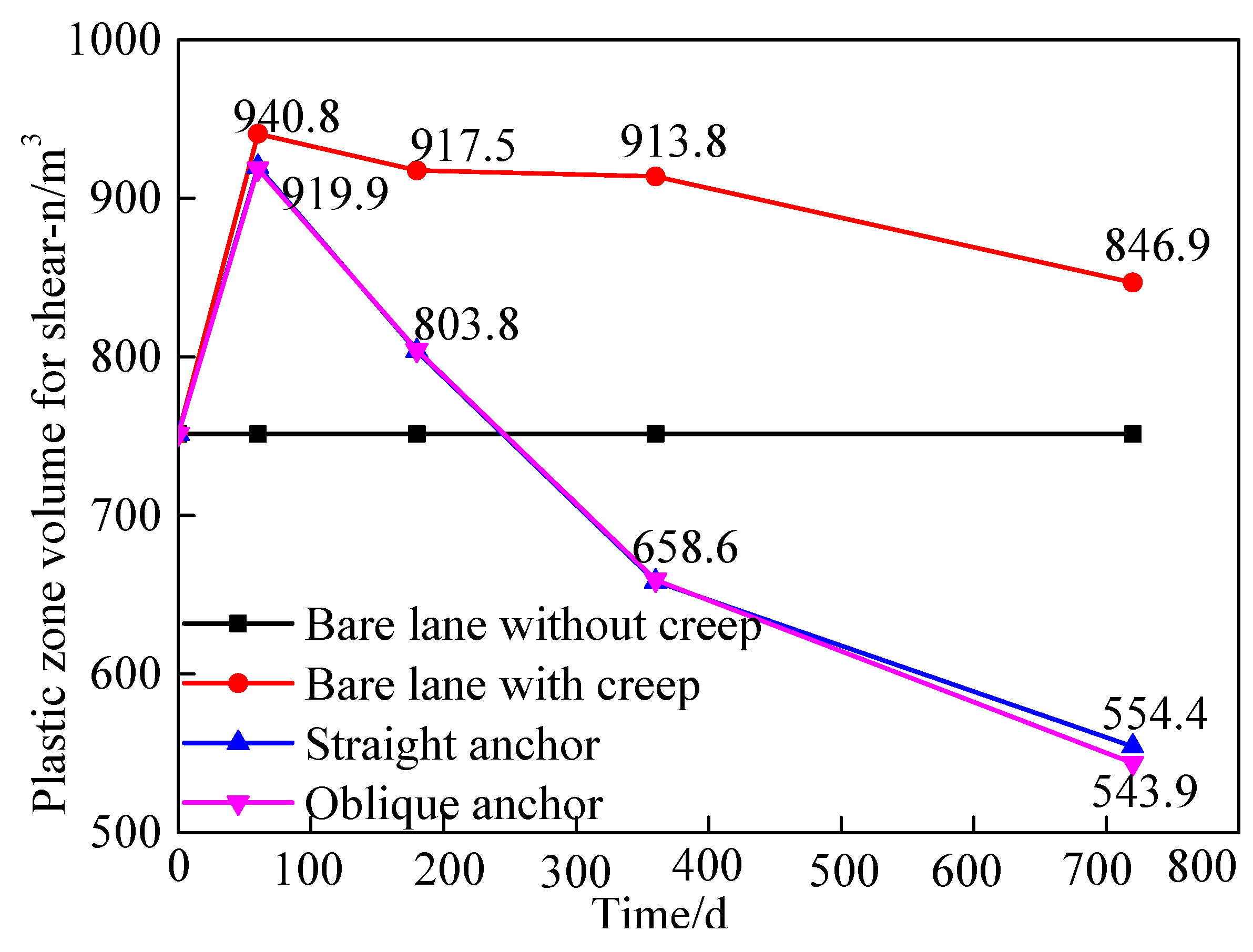

4.3.1. The volume variation of shear-n zone

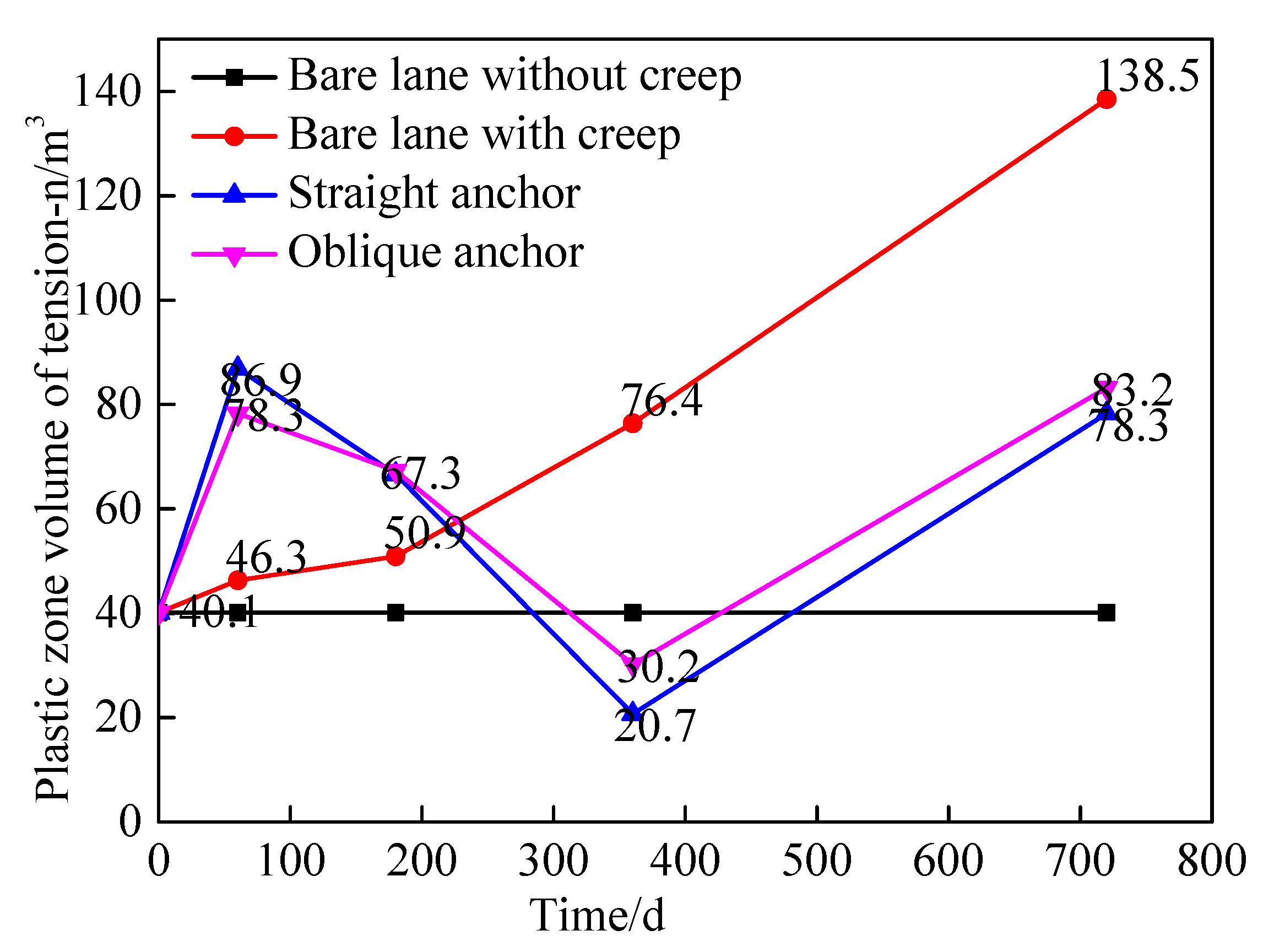

4.3.2. The volume variation of tension-n zones

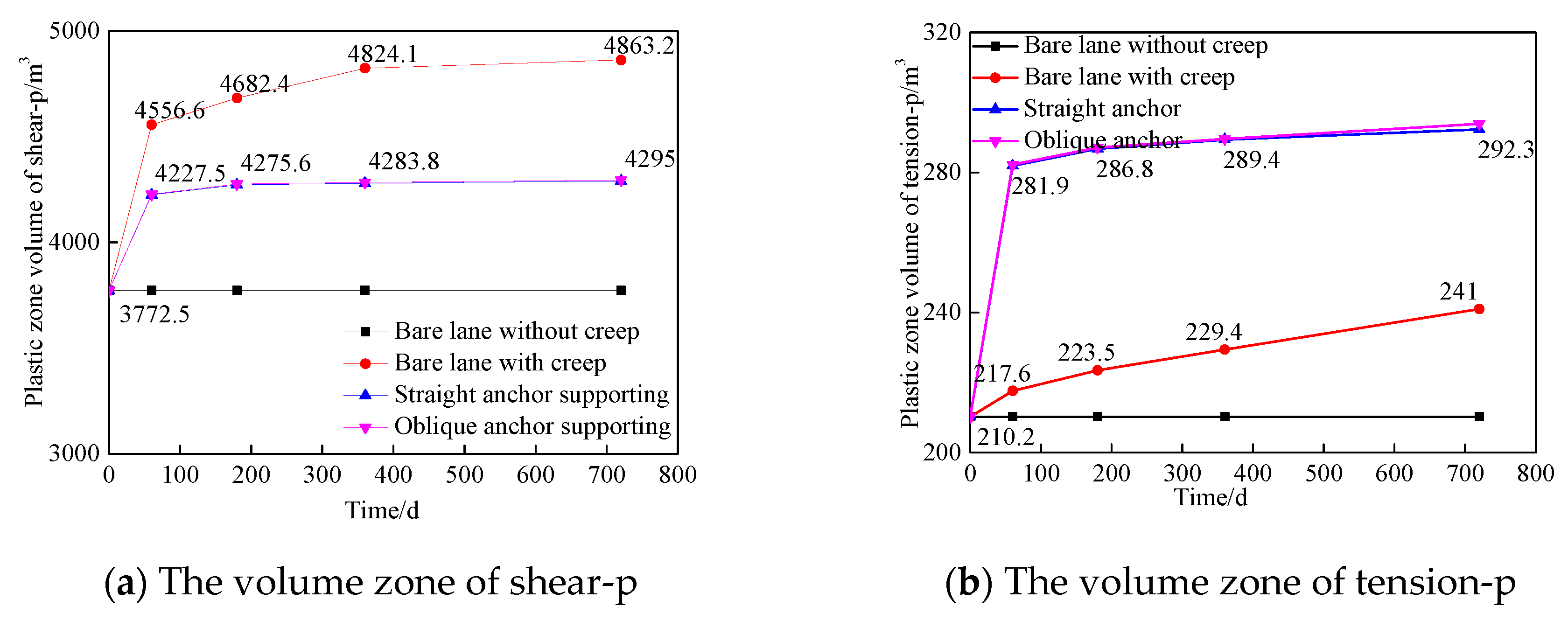

4.3.3. The volume variation of tension-p and shear-p zones

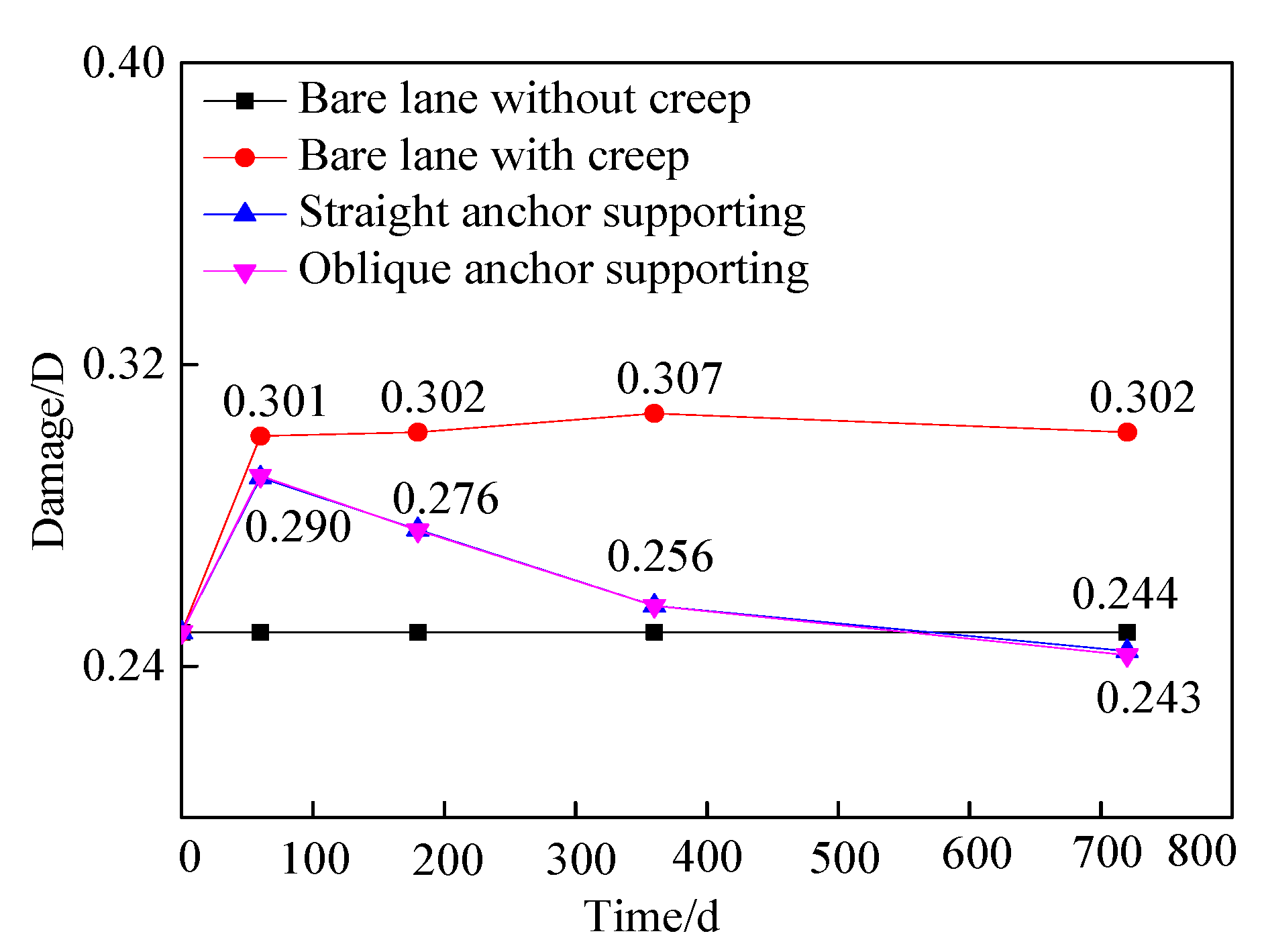

4.4. Analysis of damage variables

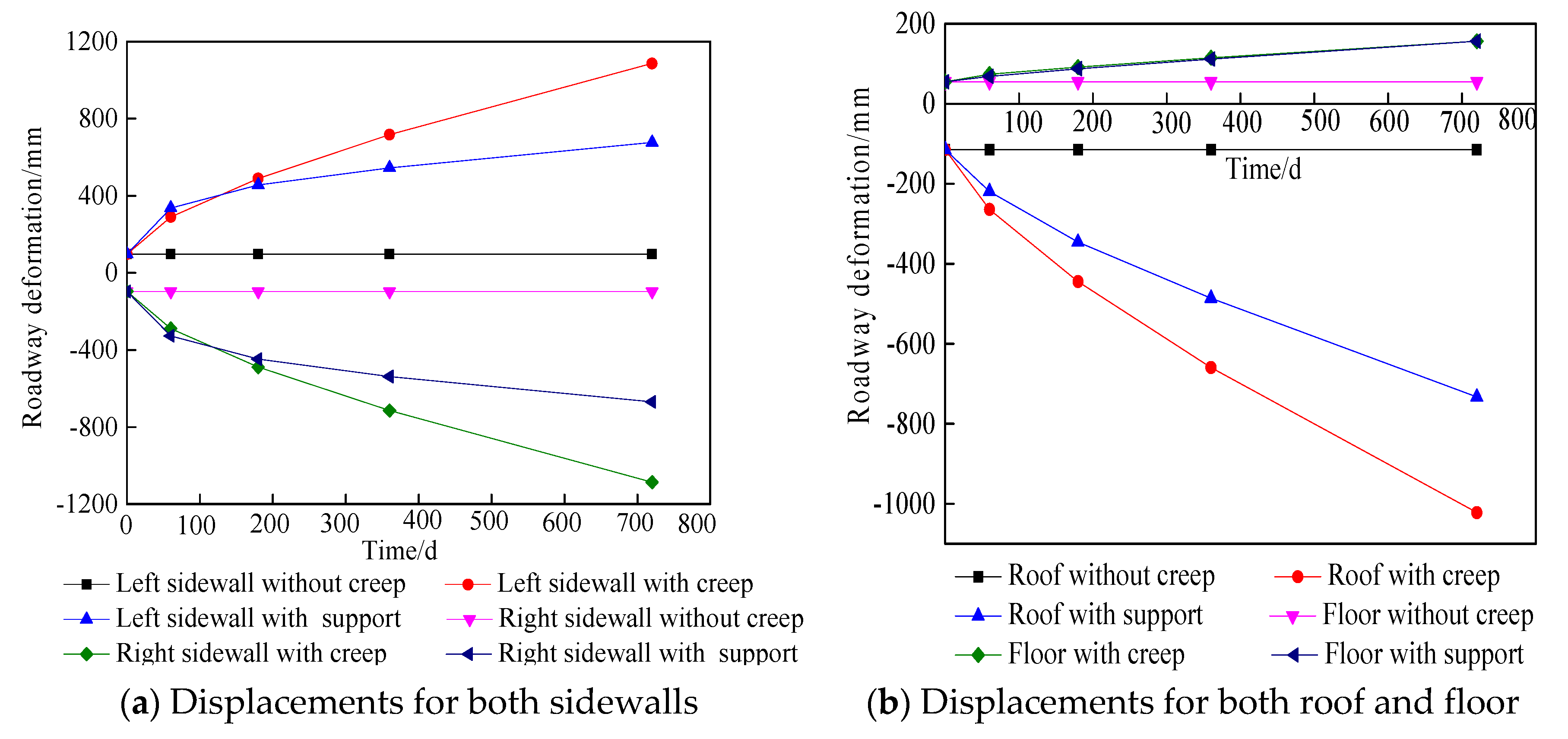

4.5. Analysis of the displacement field

5. Engineering applications

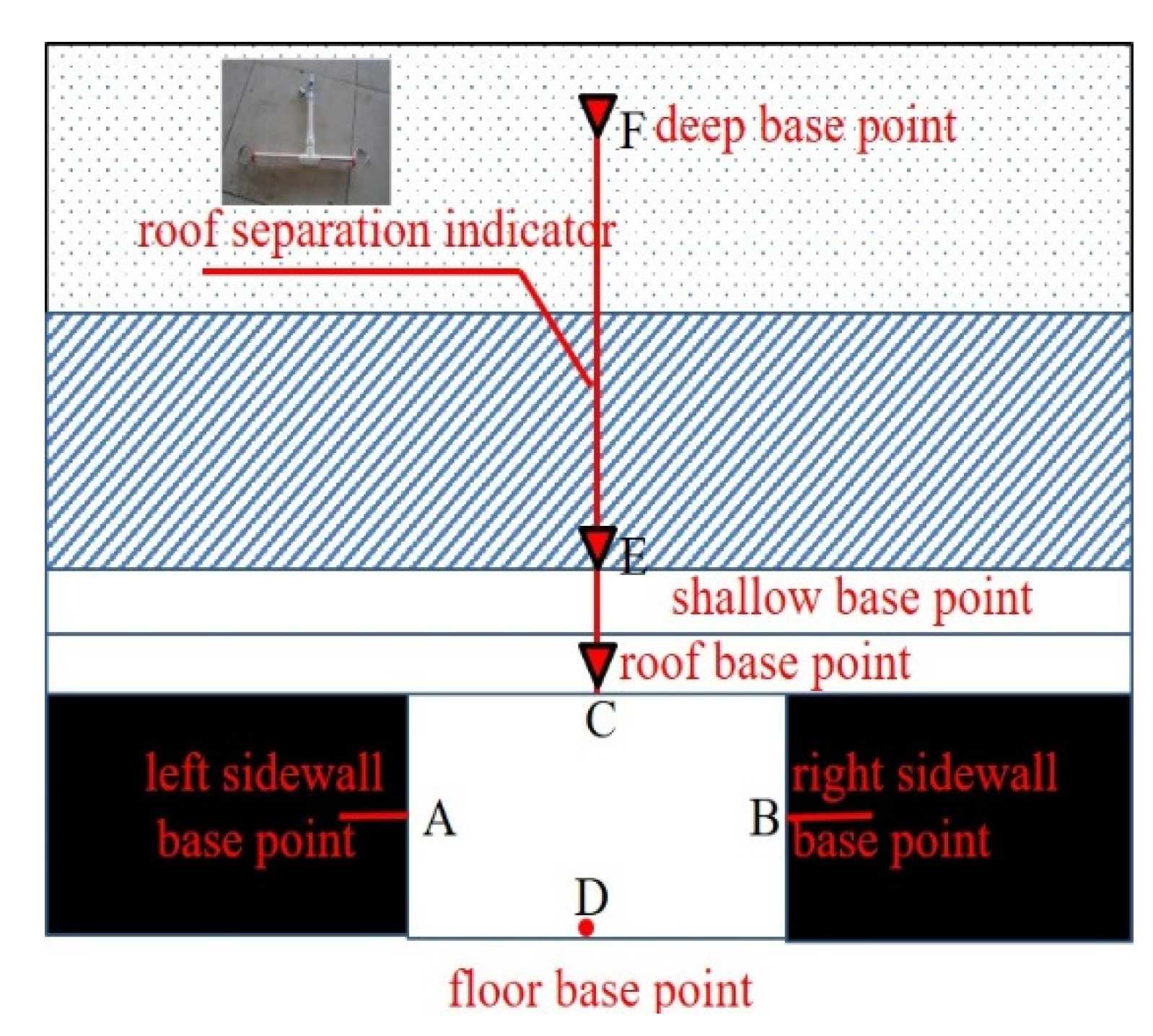

5.1. Measuring point arrangement

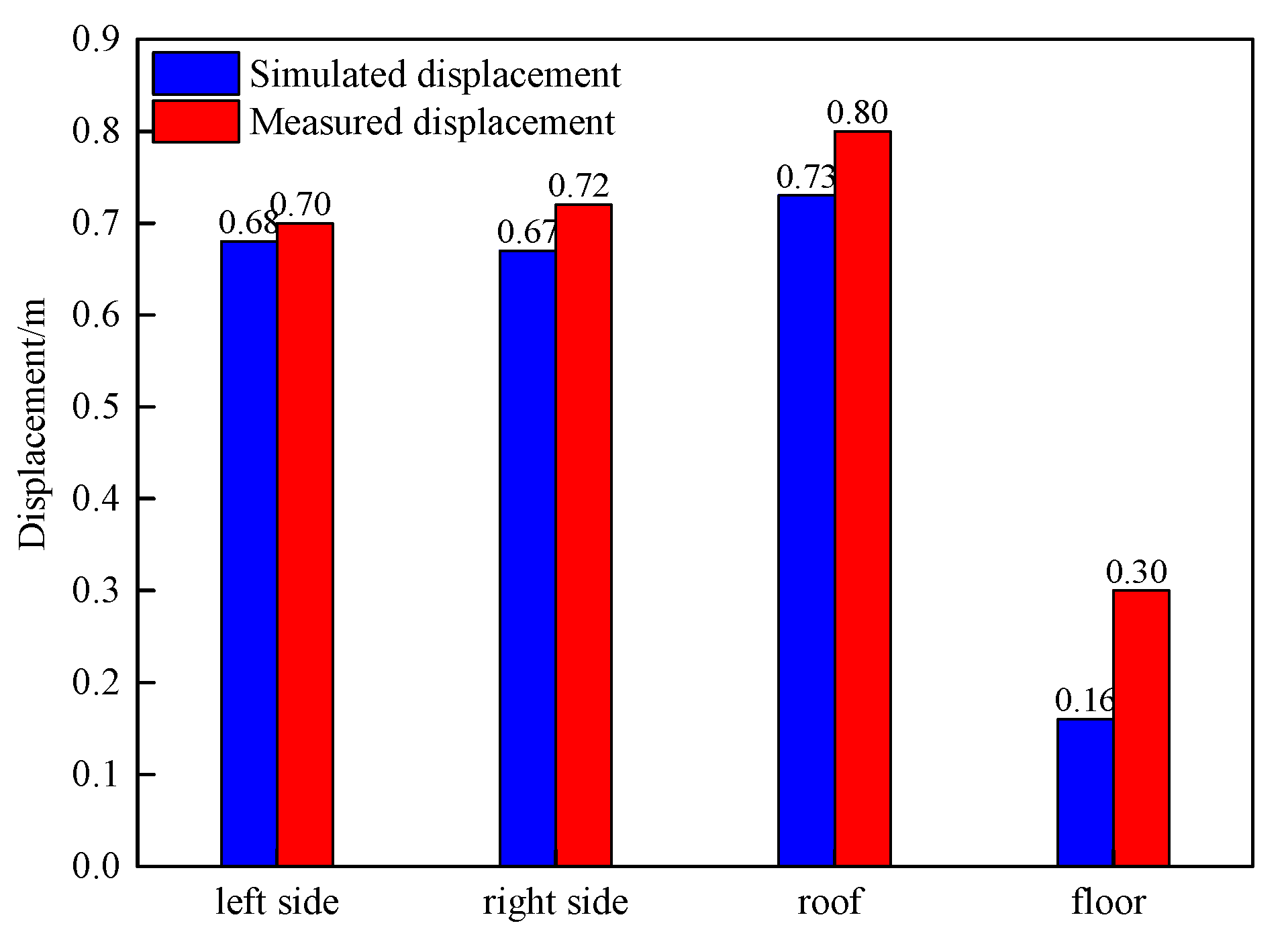

5.2. Model validation by engineering practice

6. Conclusion

- The long-term strength of coal is lower than sandy mudstone. The long-term strength of the sandy mudstone, coal respectively are 39.95 MPa, 18.65 MPa. The creep deformation of coal is more obvious than sandy mudstone.

- Under the high-stress environment in deep coal mines, creep has a significant influence on the deformation of coal and rock. Under bare roadway conditions, the creep composed 45 % ~ 88 % of the deformation, and the damage is 17.5 %.

- After roadway excavation, the creep of the surrounding rock can be divided into three stages: the acceleration stage (0~60 d), the decaying stage (60~360 d) , and the stable stage (360~720 d). In the acceleration stage, the displacement and damage of the surrounding rock increase rapidly; in the decaying stage, the displacement of surrounding rock and the damage slowly increase; in the stable stage, the displacement slowly increases and the damage decreases.

- Bolting and shotcrete can effectively suppress the displacement and damage of surrounding rock. Bolting and shotcrete closed the surrounding rock and maintained the residual strength of the surrounding rock, supporting and surrounding rock together acted as the load-bearing structure, this increased the stress threshold of the surrounding rock rheology and increased the stability of the roadway. In terms of restraining the creep displacement of the surrounding rock, there is no difference between the straight anchor and the oblique anchor. In terms of restraining the shear plastic zone, the oblique anchor has an advantage, and the straight has an advantage in suppressing the tensile plastic zone.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Name | Preload ( kN) |

Breaking load (kN) | Sidewall support density (m2/piece) | Roof support density (m2/piece) | Floor support density (m2/piece) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anchor | 60 | 144 | 2.5 | 2.14 | 0.71 |

References

- Bai JB, Hou CZ, Huang HF (2004). Numerical simulation of the stability of narrow coal pillars along goaf roadway. Chin J Rock Mech Eng 23 (20): 3475-3475.

- Chen ZQ, He C, Dong WJ, et al(2018).Comparative analysis of physical and mechanical properties and study on energy damage evolution mechanism of Jurassic and Cretaceous muddy sandstones in northern Xinjiang [J] Geotechnical Mechanics, 39 (8): 1-13.

- Chen GQ, Guo F, Wang JC, et al(2017). Experimental study on triaxial creep properties of quartz sandstone after freezing and thawing [J] Geotechnical Mechanics, 38 (S1): 203-210.

- Cai MF(2013).Rock mechanics and Engineering. 2nd Edition [M]. Beijing: Science Press.

- Cai Yu, Cao Ping(2016). A non-stationary rock creep model considering damage based on the Burgers model [J] Geotechnical Mechanics, 37 (S2): 369-374.

- Cheng AP, Fu ZX, Liu LS, et al(2022) Creep Hardening Damage Characteristics and Nonlinear Constitutive Model of Cemented Fill [J] Journal of Mining and Safety Engineering, 39 (03): 449-457.

- Chen GX, Guo BB, Hao Z(2020). The starting conditions of rock burst under the influence of accelerated creep in the surrounding rock of circular tunnels [J] Journal of Coal Science 45 (10): 3401-3407.

- Dong EY, Wang WJ, Ma NJ, et al(2018). Analysis and control technology of anchoring spatiotemporal effect considering surrounding rock creep [J] Journal of Coal Science 43 (05): 1238-1248.

- Gong H, Li CH, Zhao K(2015). The b-value characteristics of short-term creep sound emission in red sandstone [J] Journal of Coal Science 40 (S1): 85-92.

- Guo H, Liu Y, Cui BQ, et al(2018). Research on creep damage model of filling paste [J] Mining Research and Development 38 (3): 104-108.

- Helal H , Homand-Etienne F , Josien J P(1988) . Validity of uniaxial compression tests for indirect determination of long-term strength of rocks[J]. International Journal of Mining and Geological Engineering, 6(3):249-257.

- Hu Bo, Wang ZL, Liang B, et al(2015). Experimental study on creep characteristics of rocks [J] Experimental Mechanics,30 (4): 438-446.

- Huang HF, Juneng P, Huang M, et al(2017). A Nonlinear Creep Damage Model for Soft Rock and Its Experimental Study [J] Hydrology, geological engineering Geology 44 (3): 49-54.

- Huang WP, Li C, Xing WB, et al(2018). The long term asymmetric large deformation mechanism and control technology of kilometer-deep roadway under creep state [J] Journal of Mining and Safety Engineering 35 (3): 481-489.

- He MC, Jing HH, Sun XM (2002). Soft Rock Engineering Mechanics. Science Press, Beijing, pp 18-21.

- Hu K, Feng Q, Li H, Hu Q (2018). Study on creep characteristics and constitutive model for Thalam rock mass with a fracture in a tunnel. Geotech Geol Eng 36:827–834.

- Jiang ZB(2016). Experimental study on creep characteristics of rocks under multiple environmental effects and mechanical models Dalian Maritime University.

- Jiang DY, He Y, Ouyang ZH, et al(2017). Statistical analysis of acoustic emission energy and cross-sectional morphology of sandstone under uniaxial creep [J] Journal of Coal Science, 42 (06): 1436-1442.

- Jiang FX, Feng Y, KOUAME K J A, et al(2015). Study on the "creep type" impact mechanism of high ground stress extra-thick coal seam [J] Journal of Geotechnical Engineering, 37 (10): 24-30.

- Jia GS, Kang LJ (2002). Study on stability of coal pillars in mining roadway with fully mechanized caving mining. J China Coal Soc 27 (1): 6-10.

- Kang HP, Fan MJ, Gao FQ, et al(2015). Deformation Characteristics and Support Technology of Surrounding Rocks in Deep Well Tunnels Exceeding Kilometers [J] Journal of rock mechanics and Engineering, 34 (11): 2227-2241.

- Lajtai E Z (1991). Time-dependent behavior of the rock mass. Geotech Geol Eng 9(2):109-124.

- Liu XX, Li SN, Zhou YM, et al(2020). Study on creep characteristics and long-term strength of high-stress argillaceous siltstone [J] Journal of rock mechanics and Engineering, 39 (1): 138-146.

- Li GY(2017). Experimental study on the influence of water on the creep mechanical properties of coal and rock [D] Xi'an University of Science and Technology.

- Liu YK(2012). Research on the Damage Evolution and Rheological Characteristics of Deep Rock Mass under the Action of Water and Rock [D] Central South University.

- Li P(2017). Experimental study on acoustic emission under the coupling effect of coal rock seepage and creep [J] Mining Safety and Environmental Protection 44 (4): 19-23.

- Liu CX, Wang L, Zhang XL, et al(2017). Microscopic damage mechanism analysis of short-term creep tests of deep well coal and rock under different confining pressures [J] Geotechnical Mechanics,38 (9): 2583-2588.

- Li LC, Xu T, Tang CA, et al(2007). Numerical simulation of rock creep instability and failure process under uniaxial compression [J] Geotechnical Mechanics, 28 (9): 1978-1983.

- Lu YL, Wang LG(2015) Numerical simulation of rock creep damage and fracture process based on microcrack evolution [J] Journal of Coal Science, 40 (6): 1276-1283.

- Liu KY, Xue YT, Zhou H. A Nonlinear Viscoelastic-plastic Creep Model for Soft Rock with Unsteady Parameters [J] Journal of China University of Mining and Technology, 2018, 47 (4): 921-928.

- Liu JW, Wang YJ, Song XM (2017). Numerical simulation of creep law of coal roadway supported by ultra-thousand deep wells. Min Research Development 37(6):14-17.

- Ma QY, Yu PY, Yuan P(2018). Experimental study on the influence of dry wet cycle on the creep characteristics of deep siltstone [J] Journal of rock mechanics and Engineering, 37 (3): 593-600.

- Niroshan N, Yin L , Sivakugan N, et al(2018). Relevance of SEM to Long-Term Mechanical Properties of Cemented Paste Backfill[J]. Geotechnical and Geological Engineering, 36:2171-2187.

- Pan YS, Zhu P, Wang DL(1998). The creep simulation test and numerical analysis of deep tunnel floor heave and its prevention and control [J] Journal of Heilongjiang Institute of Mining and Technology, 8 (02): 1-7.

- Shen Z, Wang J, Ning JG, et al(2021). Study on the creep characteristics of filling materials considering the content of cement [J] Mining Research and Development, 41 (6): 57-65.

- Shen MR, Chen JF(2006). Rock mechanics [M] Shanghai: Tongji University Press.

- Song YJ, Lei SY, Liu XK(2012). A Nonlinear Creep Model of Rock Based on Hardening and Damage Effects [J] Journal of Coal Science, 37 (S02): 287-292.

- Song YF, Pan YS, Li ZH, et al(2018). Research on the creep instability of isolated coal pillars under rockburst [J] Coal Mine Safety, 49 (5): 47-50.

- Wang YC, Wang YY, Li JG(2019). Research on the creep mechanism of shale under chemical corrosion effect [J] Coal Mine Safety, 50 (8): 67-71.

- Wang YY, Sheng DF(2019)Research on the entire process of rock creep considering damage based on the Burgers model [J] Mechanics Quarterly, 40 (1): 143-148.

- Wang GG, Zhu ST, Jiang FX, et al(2019). Research on the mechanism and prevention of overall instability and impact of isolated coal bodies in kilometer-deep mine tunnels [J] Journal of Mining and Safety Engineering36(5):968-976.

- Wei SJ,Gou PF,Yu CS (2013). Simulation and control technology of surrounding rock creep of large section broken chamber. J Min Saf Eng 30 (4): 489-494.

- Xu P, Yang SQ(2018).Numerical simulation of creep mechanical properties of composite rock under triaxial compression [J] Journal of Mining and Safety Engineering, 35 (1): 179-187.

- Yao QL, Zhu L, Huang QX, et al(2019). Experimental study on the influence of water content on the creep characteristics of fine-grained feldspar lithic sandstone [J] Journal of Mining and Safety Engineering,36 (5): 1034-1042.

- Yin GZ, He B, Wang H, et al(2015). Creep damage and failure law of overlying rock under the influence of deep mining [J] Journal of Coal Science 40 (6): 1390-1395.

- Yin ZP, Liu XF, Zhang JN(2017). A Nonlinear Creep Damage Model for Aqueous Rock Mass and Its Application [J] Journal of Applied Mechanics 34 (2): 377-383.

- Yang YJ, Xing LY, Zhang YQ, et al(2015) Study on the long-term stability of gypsum pillar based on creep test [J] Journal of rock mechanics and Engineering, 34 (10): 2106-2113.

- Yang YJ, Duan HQ, Liu CX, et al(2017). Reasonable Setting of Uphill Protection Coal Pillars in Deep Well Mining Areas Considering Long-Term Stability [J] Journal of Mining and Safety Engineering, 34 (5): 921-927.

- Yang Y, Tian RD(2016). Creep law of coal pillars left underground in coal mines [J] Journal of Liaoning University of Engineering and Technology: Natural Science Edition, 35 (10): 1026-1031.

- Zhang QY, Zhang LY, Xiang W, et al(2017) Study on triaxial creep test of gneissic granite considering temperature effect [J] Geotechnical Mechanics, 38 (9): 2507-2514.

- Zhao BY, Liu DY, Zhu KS, et al(2011). Experimental study on uniaxial direct tensile creep characteristics of Chongqing red sandstone [J] Journal of rock mechanics and Engineering, 30 (S2): 3960-3965.

- Zuo Y Y, Han L, Hu H, Luo SY, Zhang Y, Cheng XM(2018). Visco-elastic–Plastic Creep Constitutive Relation of Tunnels in Soft Schist. Geotech Geol Eng 36(1):389-400.

- Zhang SC, Sheng DF, An WJ, et al(2021). Nonlinear viscoelastic plastic analysis of rubber asphalt composite materials based on improved Burgers model [J] Mechanics Quarterly, 42 (03): 528-537.

- Zhao YL, Ma WH, Tang JZ, et al(2016). A rock variable parameter creep damage model based on plastic expansion and its engineering application [J] Journal of Coal, 41 (12): 2951-2959.

- Zhang JF, Wang K, Zhang XQ, et al(2017). Numerical study on the width of residual coal pillars under the influence of creep failure [J] Mining Research and Development,37 (11): 51-54.

| Specimen(No.) | UCS(MPa) | E(GPa) | Density(g.cm-3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 32.19 | 2.02 | 1.31 |

| A2 | 33.73 | 2.01 | 1.36 |

| A3 | 46.09 | 1.87 | 1.14 |

| B1 | 82.08 | 10.52 | 2.17 |

| B2 | 76.49 | 10.54 | 2.14 |

| B3 | 81.23 | 9.75 | 2.14 |

| Buried depth (m) | Maximum principal stress (MPa) | Intermediate principal stress (MPa) | Minimum principal stress (MPa) | Burst orientation (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 718 | 24.21 | 21.40 | 16.51 | 45 |

| 731 | 21.00 | 20.65 | 16.81 | 45 |

| average | 22.60 | 21.00 | 16.66 | 45 |

| Rocktpe | Bulk (GPa) | GK (GPa) | GM (GPa) | ηK (GPa.h) | ηM (GPa.h) | Cohesion (MPa) | Internal friction angle (°) | Tensile strength (MPa) | Dilatancy angle (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| siltstone | 2.02 | 132.6 | 6.1 | 937 | 23079 | 1.60 | 26.1 | 1.75 | 11.6 |

| Sandy mudstone | 2.80 | 156.3 | 5.3 | 937 | 15702 | 1.67 | 28.2 | 0.32 | 10.7 |

| 3-1 coal | 1.86 | 55.6 | 3.7 | 631 | 8703 | 1.28 | 21.8 | 0.15 | 15.3 |

| Sandy mudstone | 2.79 | 156.3 | 5.3 | 937 | 15702 | 1.61 | 27.7 | 0.30 | 10.7 |

| siltstone | 2.02 | 132.6 | 6.1 | 1331 | 23079 | 1.60 | 26.1 | 1.75 | 11.6 |

| Density (kg.m-3) | Elastic modulus/GPa | Poisson's ratio | Internal friction angle/(°) | Cohesion (MPa) | Tensile strength (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2350 | 25.0 | 0.18 | 35 | 7.5 | 4.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).