3.1.1. SPR immunosensors

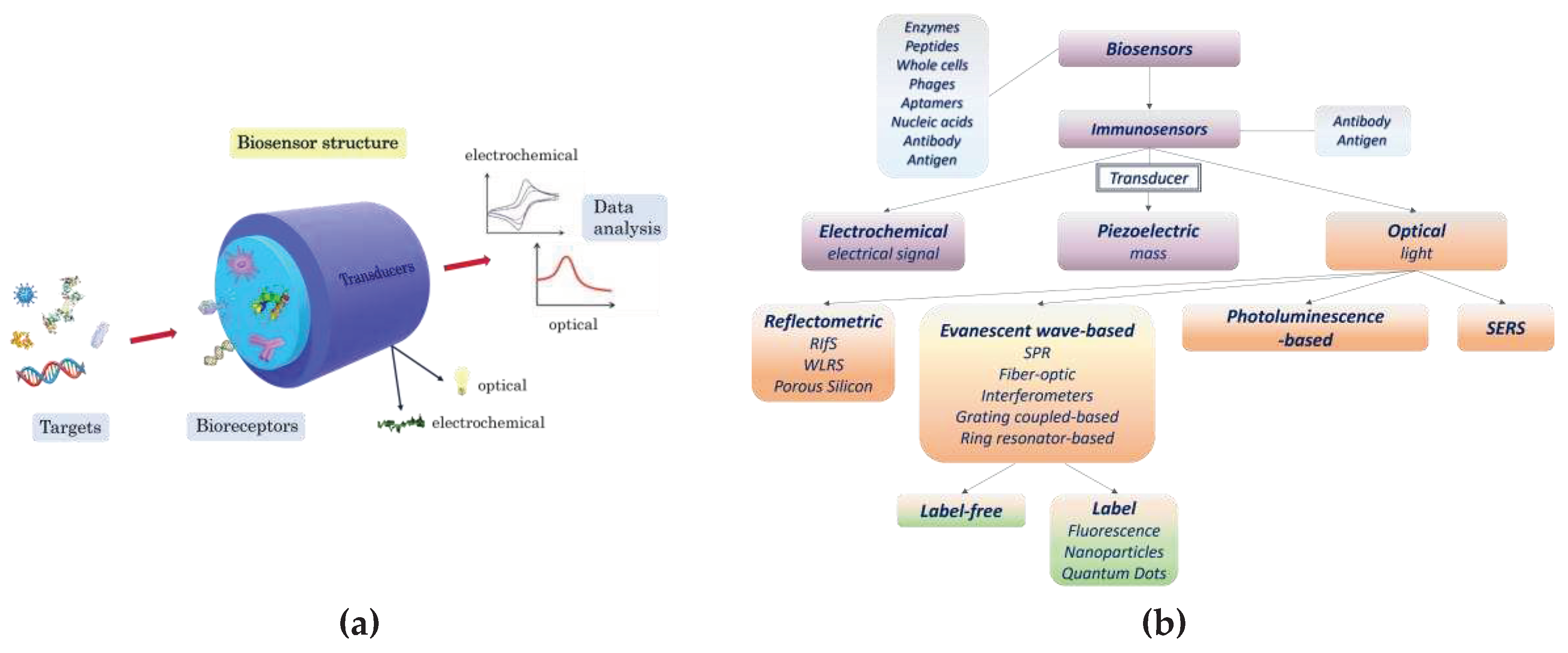

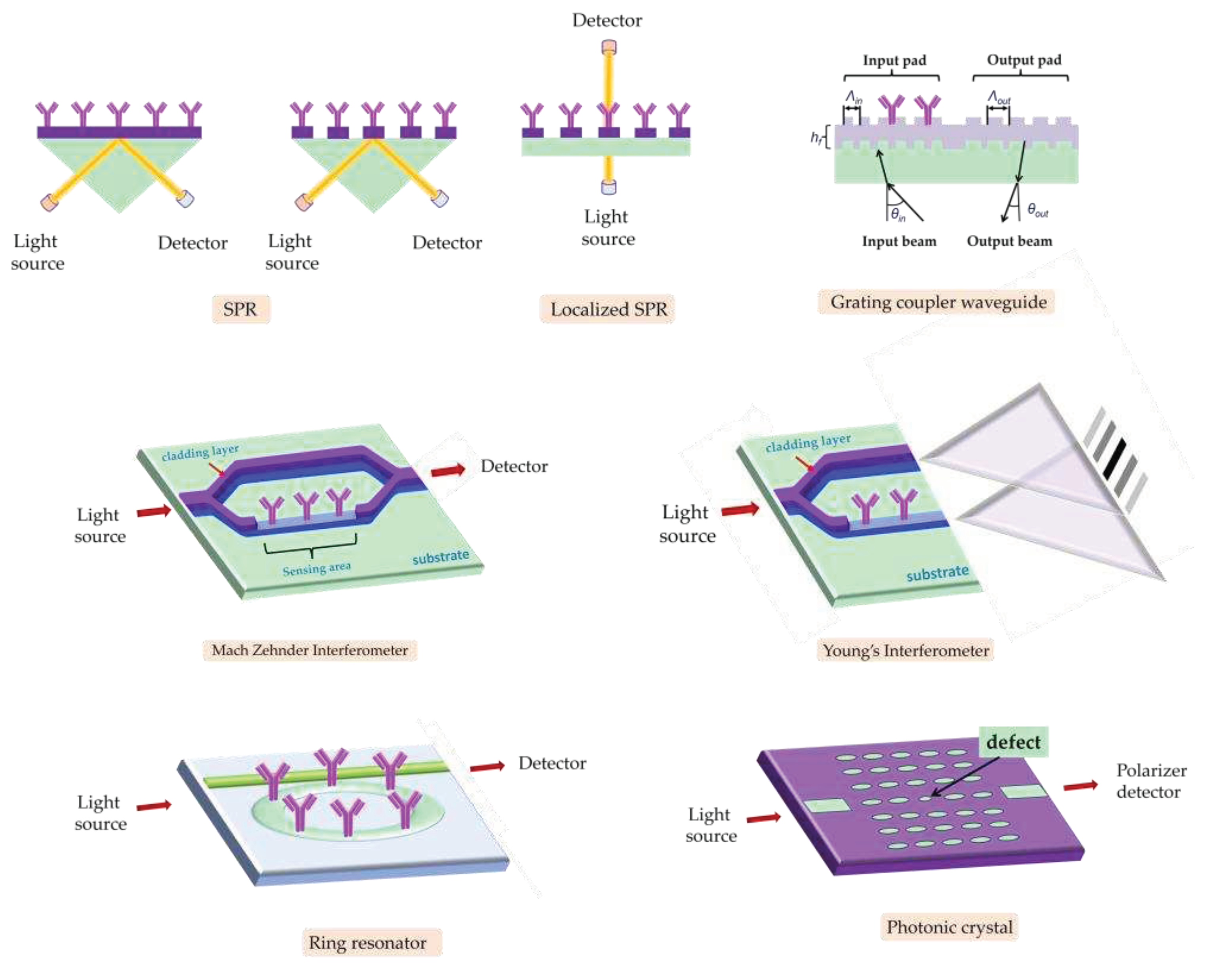

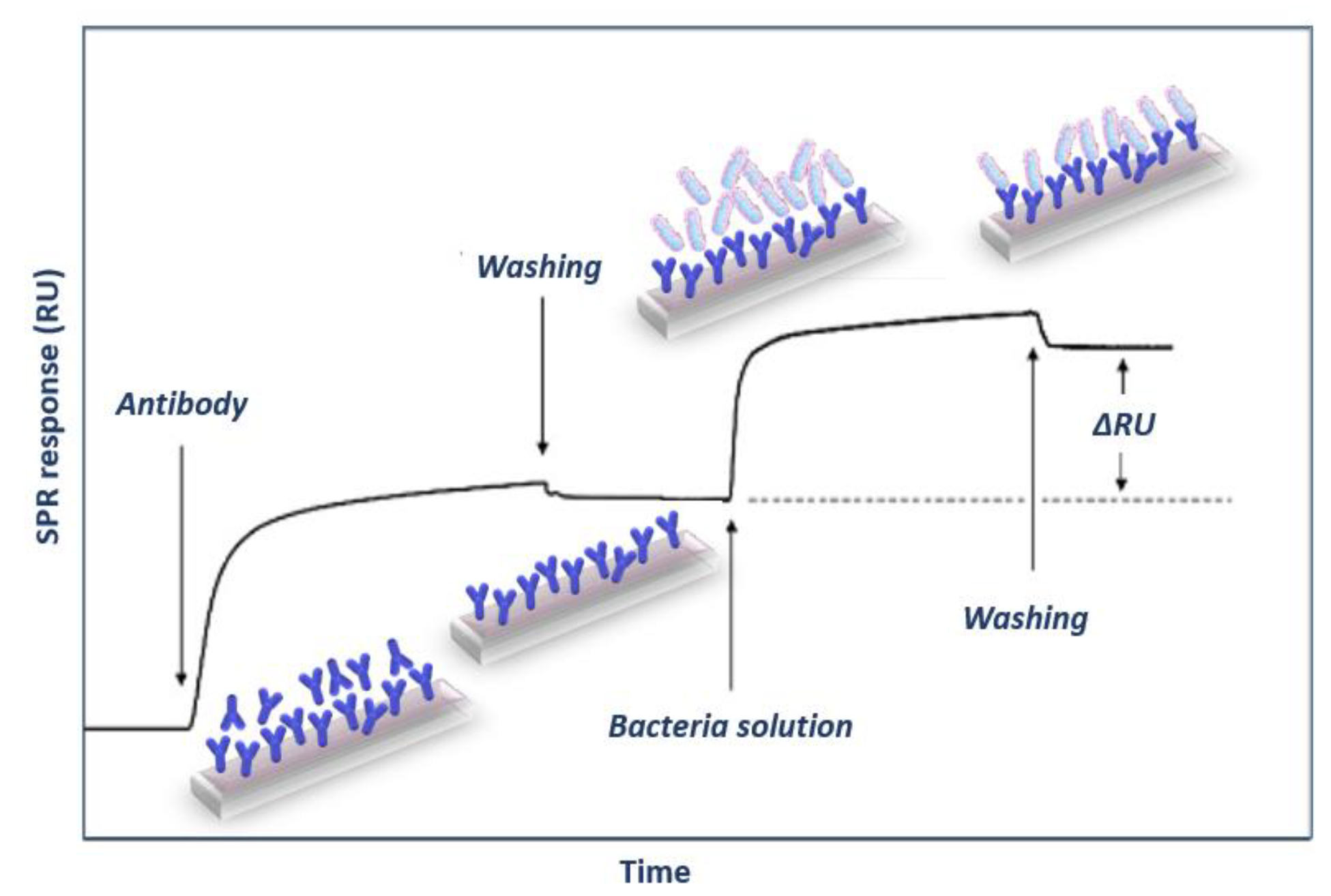

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) based immunosensors are the optical biosensors most frequently used for single or multiplex, label-free foodborne pathogenic bacterial detection due to their high detection sensitivity and monitoring of binding reactions in real-time. The SPR phenomenon relies on excitation of metal free electrons (surface plasmons) when polarized light strikes at a certain angle a metal layer (usually gold) deposited on the surface of an optically transparent material (prism, grating coupler or dielectric waveguide). The excited plasmons create an evanescent wave field at the solution/gold interface. This wave is very sensitive to refractive index changes at the gold layer surface occurring due to a biomolecular reaction, and as a result, the angle of incident light has to change during the course of the reaction to preserve the surface plasmon wave, providing the means to monitor in real-time these reactions. Thus, it is possible to monitor both the immobilization of specific biomolecules (e.g., antibodies) as well as the binding of analyte to them in real-time (

Figure 5) [

41,

44].

The first report regarding detection of bacteria with an SPR sensor is dated back to 1998 [

63], and was based on a sandwich immunoassay for detection of Escherichia

coli O157:H7. The sensor was modified with protein A or protein G and a mouse monoclonal or a rabbit polyclonal antibody, respectively, was then immobilized. Depending on the antibody used for detection, LODs in the range 5–7x10

7 cfu/mL have been achieved. Vibrio

cholerae O1 was also identified with an SPR biosensor functionalized with a protein G layer [

64]. The sensor chip was modified with a self-assembled monolayer of a mixture of 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid and hexanethiol on which protein G was covalently bound and used to immobilize a monoclonal antibody specific to V.

cholera O1. The LOD of the assay was 10

5 cfu/mL. The same antibody immobilization approach was employed to immobilize onto SPR chips an antibody against Legionella pneumophila achieving a LOD of 10

5 cfu/mL [

65]. Salmonella

enterica serovar Enteritidis and Escherichia

coli have been detected in spiked skim milk by a direct binding assay on SPR chips modified with protein G to which the anti-bacteria specific antibodies were then bound [

66]. The LOD achieved after 1-h assay was 25 cfu/mL for E.

coli and 23 cfu/mL for Salmonella. Detection of Salmonella groups B, D and E with SPR has been also reported employing a sandwich assay format and using antibody pairs from different animals [

67]. It was found that the LOD improved 200 times compared to direct detection [

67]. The benefits of the sandwich immunoassay format for bacteria detection have been also demonstrated in a study for detection of Staphylococcus

aureus with SPR, where the LOD was improved from 1x10

7 to 1x10

5 cfu/mL when a sandwich immunoassay format was followed instead of direct detection [

68]. In another report, where the direct binding assay was compared to a sandwich assay for detection of E.

coli O157:H7, a 1000-fold improvement in sensitivity was reported leading to an LOD of 10

3 cfu/mL [

69]. The immobilization of the polyclonal antibody against E.

coli was performed through covalent bonding to a monolayer of mixed thiol-terminated polyethylene glycol with alkane or carboxyl-group ends. In another report, the free amine groups of protein A were converted to thiol groups, through reaction with 2-iminothiolane, to facilitate its immobilization onto SPR chips, which are then modified with an antibody against Salmonella

paratyphi [

70]. A LOD of 10

2 cfu/mL was achieved employing the antibody modified chip in a direct binding assay. In another study, the SPR chip was modified with brushes of poly(carboxybetaine acrylamide) to reduce the non-specific binding of bacteria to its surface, while antibody modified gold nanoparticles were used as labels to increase the detection sensitivity [

71]. This immunosensor could detect E.

coli O157:H7 in hamburger and cucumber samples at concentrations as low as 57 and 17 cfu/mL and Salmonella spp. at 7.4x10

3 and 11.7x10

3 cfu/mL, respectively [

71]. Gold nanoparticles modified with an antibody against Campylobacter

jejuni were also employed as labels in an SPR sandwich immunoassay that allowed the detection of this bacterium at concentrations as low as 4x10

4 cfu/mL [

72]. A gold-labelled secondary antibody was also employed to increase the detection sensitivity in a sandwich SPR for L.

monocytogenes by 2-4 orders of magnitude compared to the direct binding assay, providing a LOD of 10

2 cfu/mL [

73]. In another study, in order to achieve signal enhancement, a precipitate 3,3’,5,5’-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate was used in combination with an antibody labelled with horse radish peroxidase (HRP) to detect bacteria captured by an antibody attached to SPR chip through covalent bonding to a self-assembled monolayer of mercaptoundecanoic acid [

74]. Following this approach, a 250% signal enhancement was achieved with respect to the assay not employing the HRP/TMB system leading to a LOD of 10

4 cfu/mL for detection of E.

coli in spinach leaves [

74]. SPR chips have been modified in a plasma reactor in presence of cyclopropylamine vapors to induce reactive moieties containing nitrogen which were in turn used to immobilize antibodies using glutaraldehyde activation [

75]. The chips were employed to detect Salmonella typhimurium by a direct binding assay that provided a LOD of 10

5 cfu/mL.

Along with the optimization of the SPR assays for bacteria detection, effort was devoted to sample treatment methods aiming either to improve detection sensitivity or alleviate non-specific matrix effects. For example, the performance of an SPR sensor for the detection of live, heat-killed, or detergent-lysed E.

coli O157:H7 cells was investigated and LODs of 10

6, 10

5, and 10

4 cfu/mL, respectively, were reported [

76]. The differences observed were ascribed to changes in cell size and morphology upon treatment with ethanol, whereas treatment with detergent led probably to fragmentation of cells to smaller particles that were recognized more efficiently by the antibody. The effect of sample preparation method was also evident in another study for detection of E.

coli O157:H7 in different food samples [

77]. In this study, milk, apple juice, and ground beef patties were spiked with E.

coli O157:H7 at various concentrations and then analyzed with a portable SPR instrument commercialized by Texas Instruments Inc. under the tradename SPREETA

TM. The sensor chip was modified with neutravidin to enable immobilization of biotinylated antibodies against E.

coli O157:H7. The spiked milk and apple juice samples were run without pretreatment, whereas the ground beef sample was extracted with buffer and homogenized prior to analysis. The LODs achieved ranged from 10

2–10

3 cfu/mL depending on the sample analyzed. In another report, where a sandwich SPR assay for Salmonella with LOD of 1.25×10

5 cells/mL was developed [

78], the authors claimed that the presence of milk did not affect the assay performance alleviating the need for sample preparation or clean-up steps.

It has been suggested that the detection of whole bacteria using SPR generally results in lower sensitivity compared to other techniques, due to the limited penetration of bacteria by the electromagnetic field and the small difference of refractive index between bacterial cytoplasm and the surrounding aqueous medium [

79]. Thus, instead of running over the sensor the sample, the sample is incubated with the pathogen specific antibody and after separation of free from bound antibody, the free antibody is quantified. This assay format is known as subtraction inhibition assay (SIA) and has been applied for the detection of L.

monocytogenes [

80], E.

coli O157:H7 [

81], and B.

anthracis spores [

82]. The LODs reported were 1×10

5, 3.0×10

4, and 10

4 cfu/mL, respectively, and were one order of magnitude lower than those achieved with the direct binding assay. The SIA format was also applied for the detection of fungal cells that are considerably larger than the bacterial ones [

83]. Thus, it has been applied for the detection of sporangia of Phytophthora

infestans [

83], and of Puccinia

striiformis with LODs of 2.2×10

6 sporangia/mL and 3.1×10

5 urediniospores/mL, respectively [

84]. A similar assay format was also applied for the SPR detection of Cryptosporidium

parvum oocysts with a LOD of 1x10

2 oocysts/mL [

85]. In a different approach for indirect bacteria detection by SPR, a polyclonal antibody against a cell extract enriched for the invasion-associated protein, internalin B, was used to develop an inhibition assay for Listeria

monocytogenes [

86]. After incubation of bacteria containing solutions with the antibody, the mixture was injected over an SRP chip modified with purified-recombinant internalin B and the signal was inversely proportional to L.

monocytogenes concentration achieving a LOD of 2x10

5 cells/mL.

In addition to single bacteria detection, multiplexed bacteria detection with SPR systems has been also explored. Thus, an antibody microarray was developed on a SPR chip for the simultaneous detection of either S.

typhimurium, E.

coli O157:H7, Yersinia

enterocolitica and Legionella

pneumophila by modifying the chip with protein G to allow immobilization of the specific for each bacterium antibody at different areas of the chip through spotting [

87]. All bacteria were detected simultaneously each at a concentration of 10

5 cfu/mL. E.

coli O157:H7, L.

monocytogenes, Campylobacter

jejuni and S.

choleraesuis were also simultaneously detected using a multi-channel SPR system [

88]. The whole chip surface was modified with streptavidin and the four bacteria antibodies were immobilized using an 8-channel fluidic (2 channels per antibody; one for the specific and the other for the non-specific signal monitoring). The LODs achieved were 1.4×10

4 cfu/mL for E.

coli, 4.4×10

4 cfu/mL for S.

choleraesuis, 1.1×10

5 cfu/mL for C.

jejuni, and 3.5×10

3 cfu/mL for L.

monocytogenes. An SPR imaging device was combined with an array of antibodies specific against different serotypes of L.

monocytogenes aiming to monitoring the growth of live listeria cells in culture [

89]. Emphasis was given to the characterization of the antibodies rather than the analytical performance of the sensor. Similarly, the detection of Salmonella with an SPR imaging array was optimized and LODs of 2.1x10

6 and 7.6x10

6 cfu/mL, in buffer and chicken carcass rinse have been demonstrated [

90]. An SPR imaging sensor has also been applied for the simultaneous label-free detection of Salmonella spp., Shiga-toxin producing E.

coli (STEC) and L.

monocytogenes in chicken carcass rinse [

89]. The specific for each bacterium antibodies were immobilized on the same chip and an LOD for Salmonella of 10

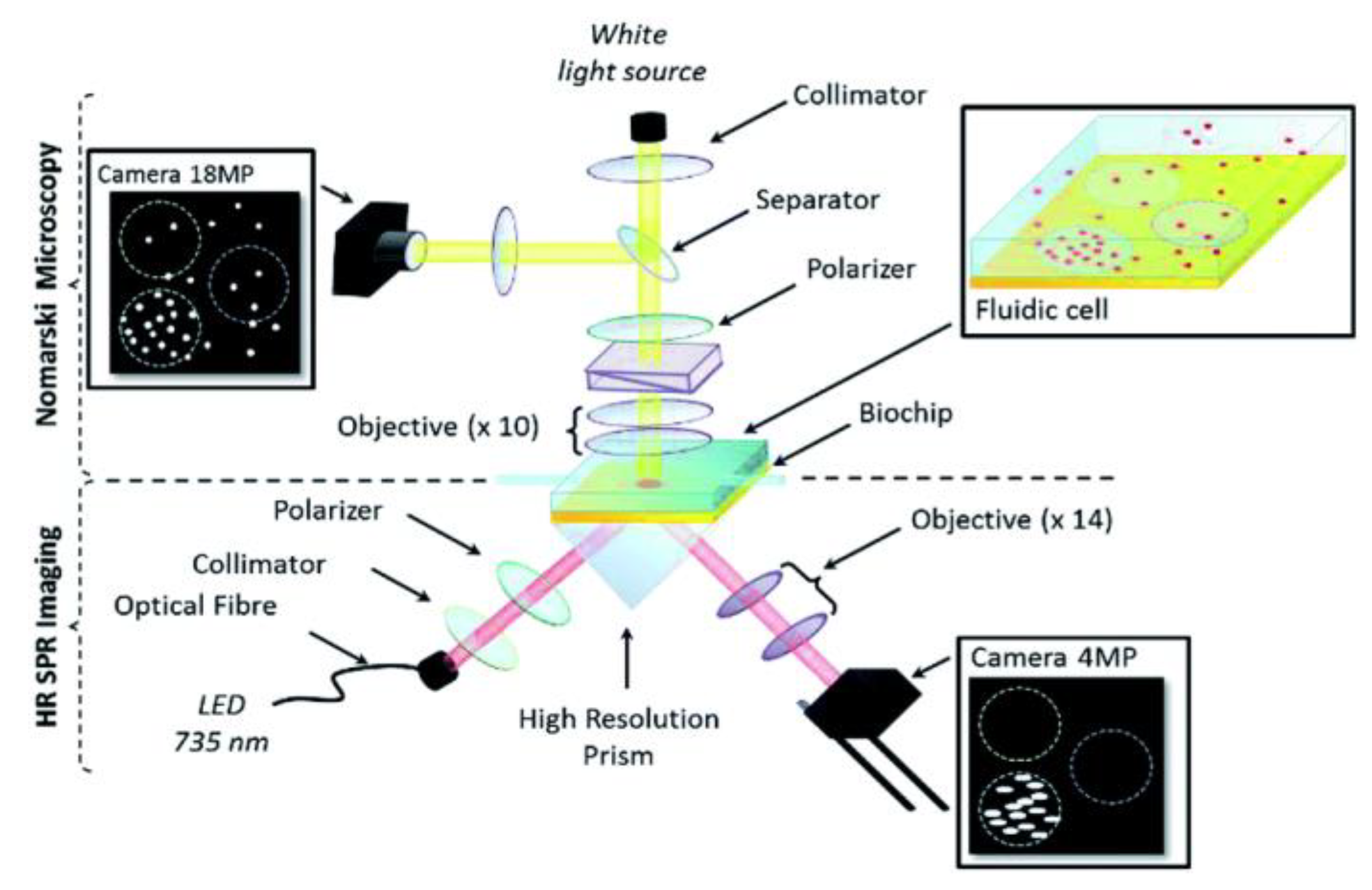

6 cfu/mL was achieved. An SPR imaging sensor (

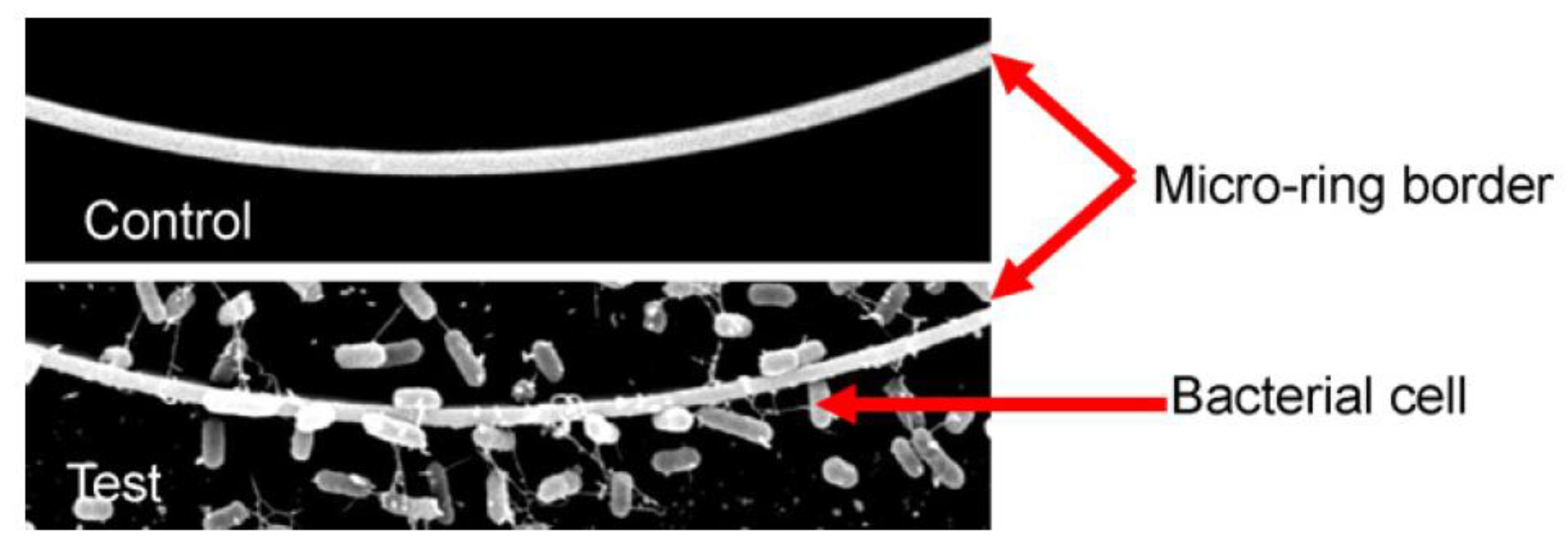

Figure 6) was also implemented for the simultaneous detection of Listeria

monocytogenes and Listeria

innocua achieving a LOD of 2×10

2 cfu/mL for both bacteria after 7-hour incubation of the sample in the fluidic cell attached to SPR chip [

92].

Despite the fact that SPR has found numerous applications in diverse fields and relatively few companies have commercialized devices based on this transduction principle, the majority of these instruments are suitable for use in a lab. Thus, much effort has been devoted on reducing the equipment size and complexity in order to build up systems appropriate for analysis at the point-of-need. The SPREETA

TM SPR biosensor mentioned above was a successful outcome of such an effort. It included an AlGaAs light emitting diode (LED, 840 nm), a polarizer, a temperature sensor, two photodiode arrays, and a reflecting mirror combined with a gold-coated glass slide and a silicone rubber gasket of two channels. The instrument was accompanied by a software that provided all the information related to analysis of SPR curve, the real time binding, the layer thickness and flow cell temperatures. In addition to determination of E.

coli O157:H7 in various food samples [

77], SPREETA

TM SPR biosensor has been also explored for the detection of Campylobacter

jejuni with an LOD of 10

3 cfu/mL [

93]. SPREETA™ was also employed to develop a sensor to detect E.

coli O157:H7 in laboratory cultures [

94]. The sensitivity and specificity of detection were determined. Thus, for an assay of 35 min, a LOD for E.

coli O157:H7 of 8.7x10

6 cfu/mL was determined in single bacteria culture, whereas in mixed cultures with non-target bacteria concentrations up to 10

6 cfu/mL or less the LOD was 10

7 cfu/mL. . For higher concentrations of non-target bacteria, the sensor sensitivity was negatively affected. In another report, using also the SPREETA™ SPR sensor for E.

coli detection an LOD of 90 cfu/mL is reported for a direct binding assay that lasted less than 30 min [

95]. A reason for the better performance achieved, with respect to previous reports, could be attributed to the fact that the specific antibody was immobilized onto the chip surface by streptavidin and not directly. Finally, SPREETA™ was applied to detect Salmonella

typhimurium at concentrations equal to or higher than 1x10

6 cfu/mL in chicken [

96]. To increase the detection sensitivity of a SPREETA™ sensor for the detection of E.

coli, Au coated magnetic nanoparticles were modified with an antibody against E.

coli and used to concentrate E.

coli cells from water samples but also as labels in a SPR sandwich immunoassay using SPREETA™ chips, that were modified with an anti-E.

coli antibody, achieving a detection limit of 3 cfu/mL [

97].

Apart from SPREETA™, other attempts to create portable instruments based on the SPR principle of detection have been reported in the literature. Thus, a portable instrument that combined microfluidic and SPR technologies on a single platform was applied for the determination of E.

coli and S.

aureus in spiked samples [

98]. In this set-up an LED was used to illuminate a gold covered rectangular prism and the reflected light was captured by a CMOS sensor and then transferred for processing to a PC. The chip was modified with 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid to facilitate the covalent binding of protein G in which an antibody against the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of E.

coli was captured enabling E.

coli detection at a concentration of 3.2x10

5 cfu/mL. In another attempt, Salmonella

typhimurium was detected in the range of 10

7 to 10

9 cfu/mL within 1 h using a SPR biosensor in which the incident light from a diode laser (instead of a LED) was directed to the gold film by a rotating mirror and the light reflected from the metal film was captured by a CMOS image sensor [

99].

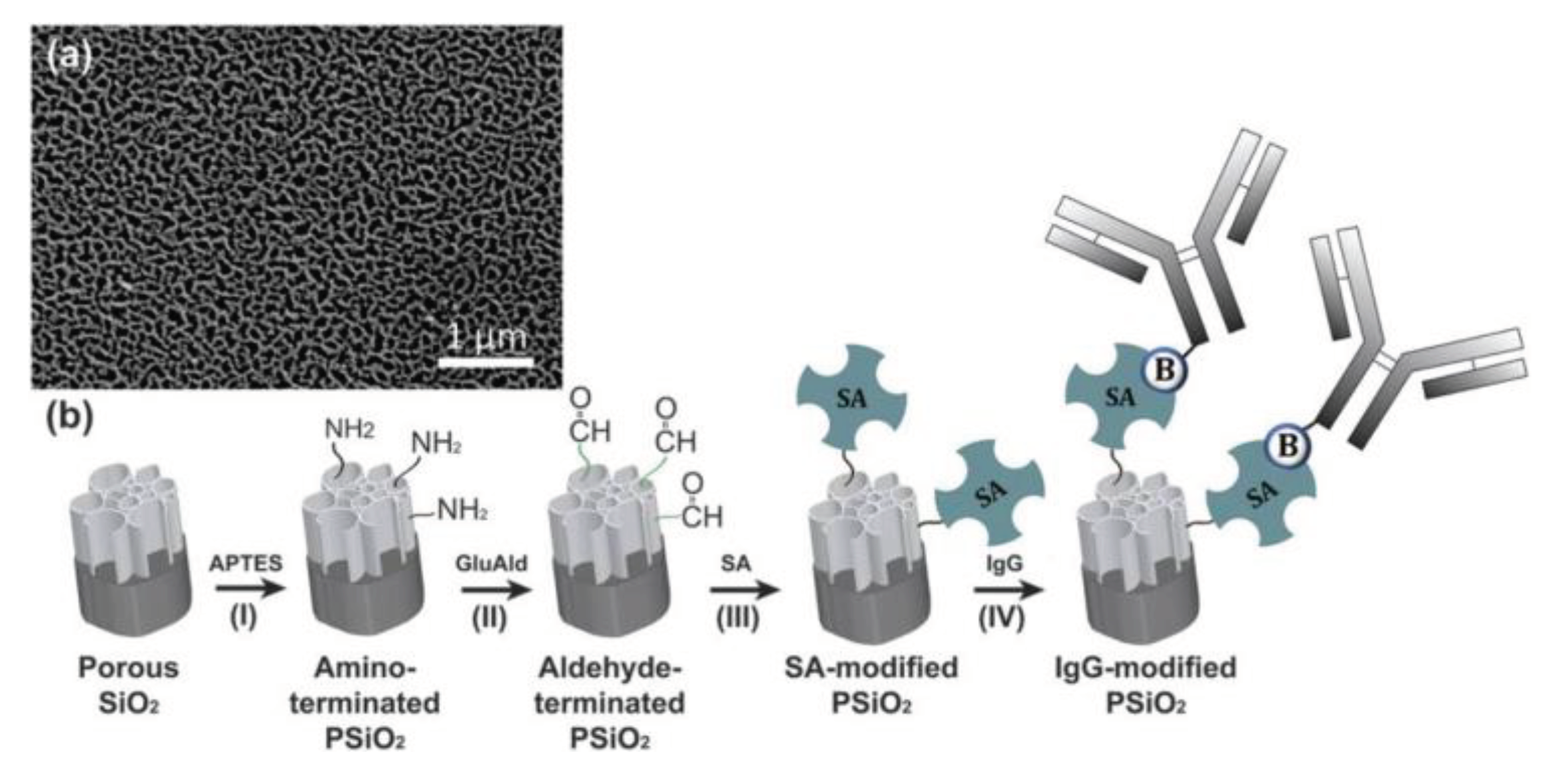

Another approach to surpass the portability limitations of standard SPR instruments is the implementation of localized SPR or LSPR transduction approach. In LSPR, the continuous metal surface is replaced by noble-metal nanoparticles (nanospheres, nanorods, or nanodisks) of sub-wavelength size around which the surface plasmons are localized [

100]. The light that strikes the nanostructures, excites the surface plasmons and when resonance is achieved, certain wavelengths are scattered from the nanostructures. Thus, immunoreactions can be monitored in real-time as shifts in the resonance wavelength [

101]. The advent of LSPR opened up new horizons for detection of pathogens, especially in the direction of portable systems. Nonetheless, the first report showed that LSPR was less sensitive than the classical SPR configuration [

102] or more vulnerable to interferences from the matrix of the samples analyzed [

103]. More recent reports, however, show improved detection sensitivity achieved mainly through optimization of the dimensions and stability of the nanoparticles [

104]. Thus, an LSPR sensor was developed for the determination of E.

coli O157:H7 employing spherical gold nanoparticles non-covalently modified with a specific anti-E.

coli avian antibody. A LOD of 10 cfu/mL was achieved in less than 2 h making the sensor suitable for E.

coli O157:H7 determination at the point-of-need [

104]. Instead of using non-continuous gold surfaces, structuring of the gold film through its deposition onto a nanostructured fluoropolymer enabled the development of a SPR sensor based on grating-coupled long-range surface plasmons which was employed for detection of E.

coli O157:H7 through a sandwich immunoassay implementing metal nanoparticles modified with another anti-E.

coli O157:H7 antibody as labels to achieve a LOD of 50 cfu/mL [

105].

The reports regarding bacteria detection with SPR based immunosensors are summarized in

Table 1.

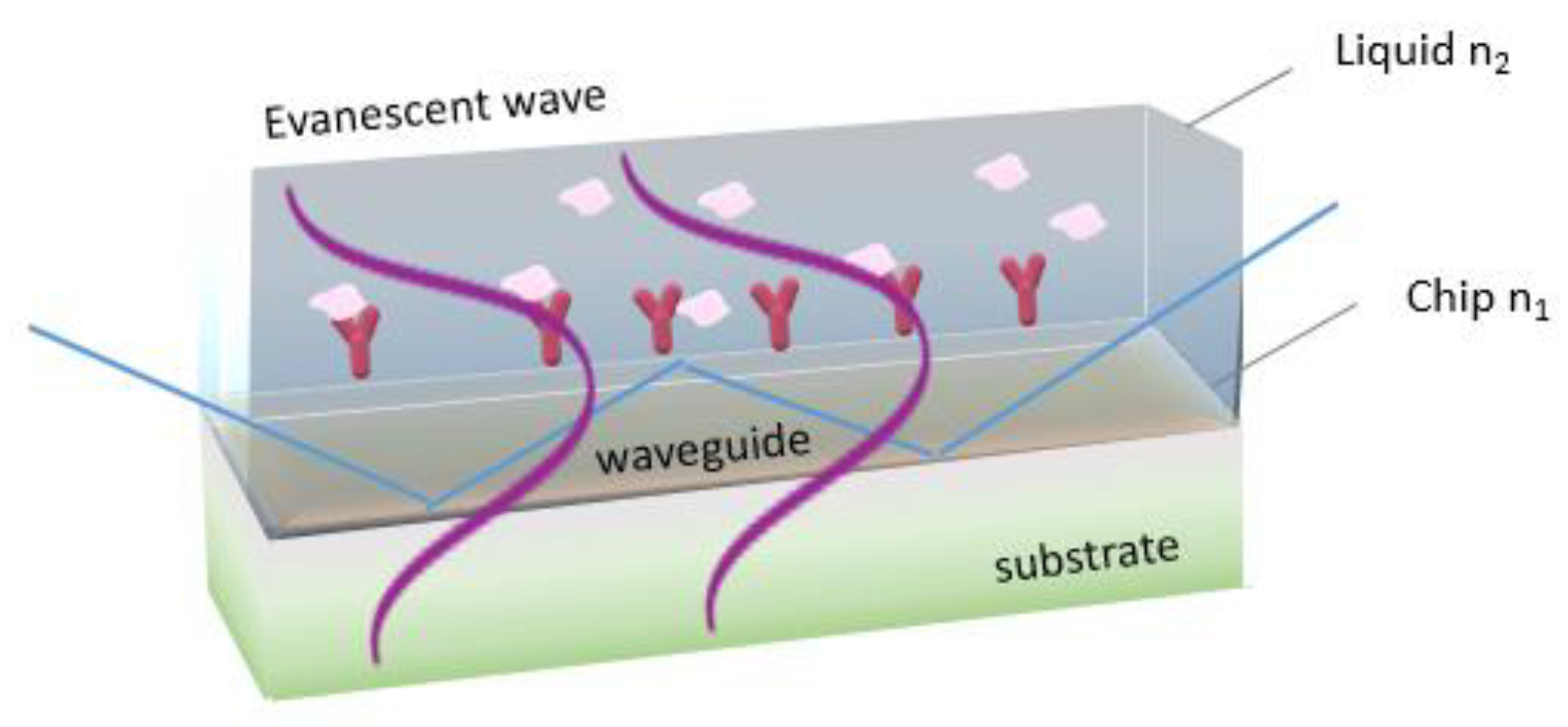

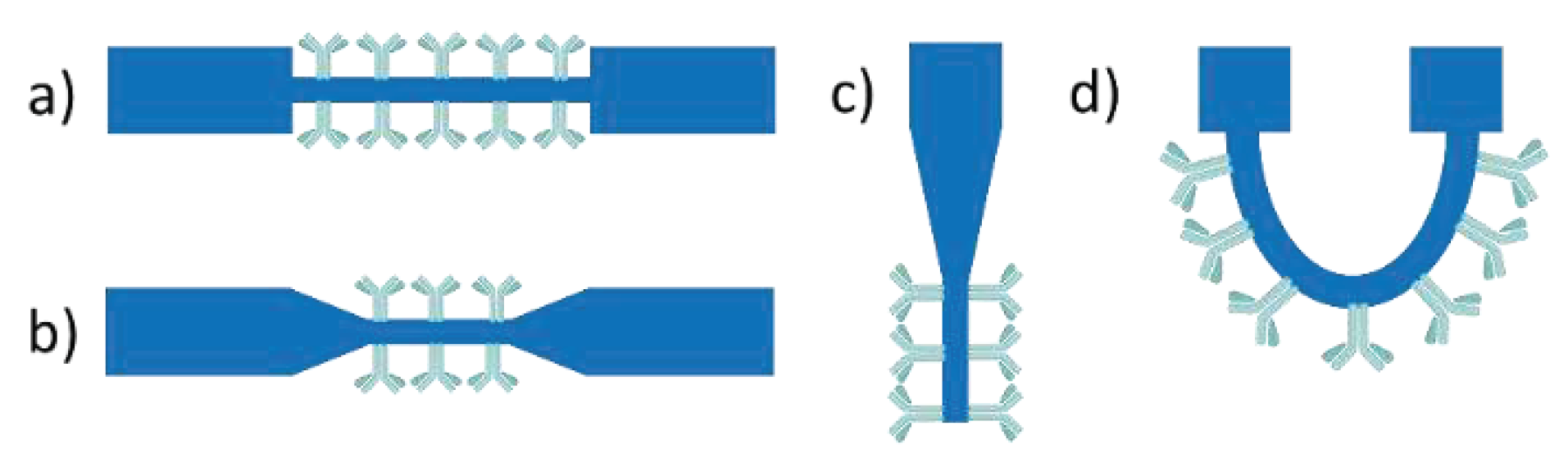

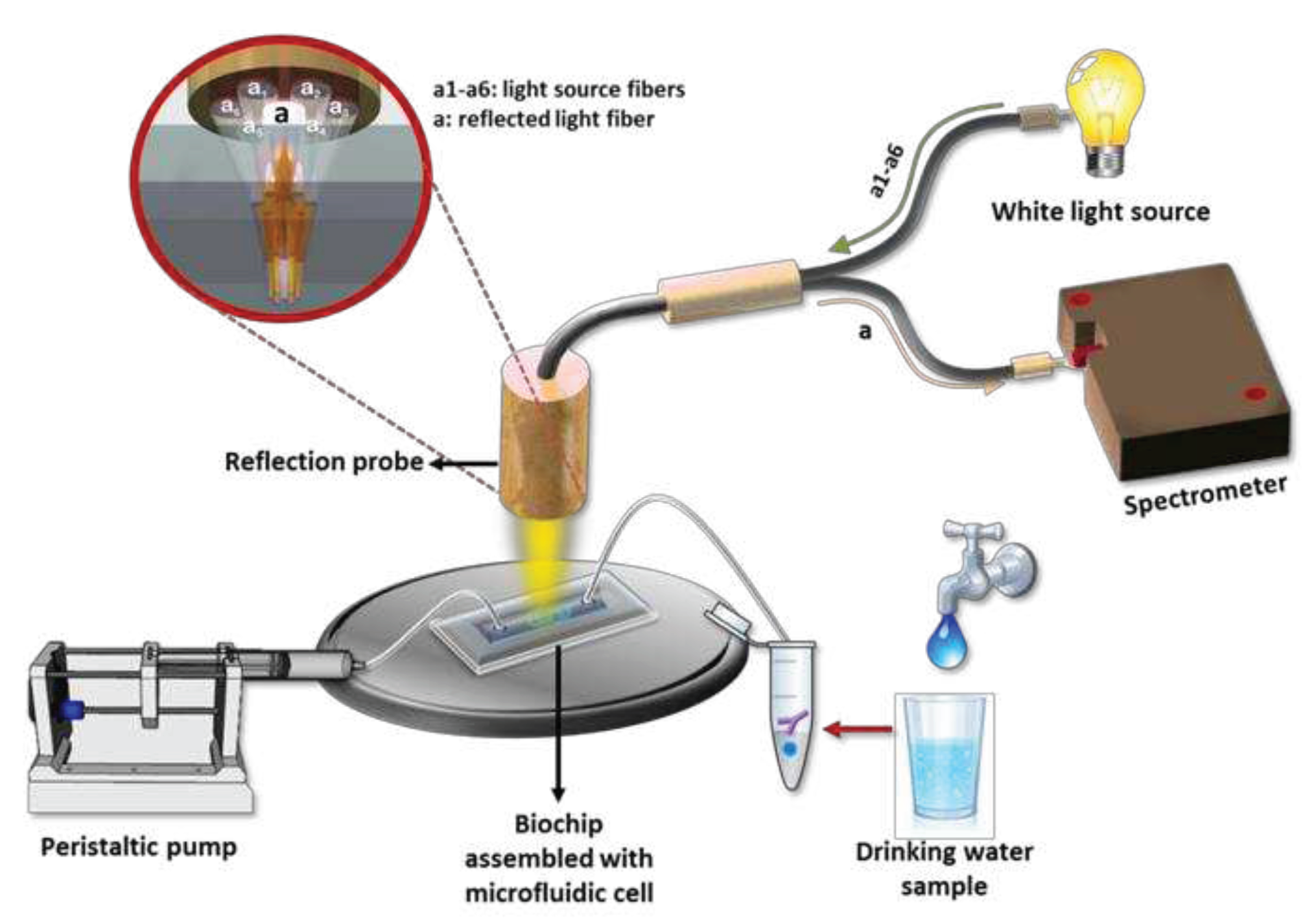

3.1.2. Fiber optic immunosensors

Fiber optic immunosensors rely on immobilization of immunoreagents onto a part of the optical fiber from which the cladding layer has been removed to allow interaction of the waveguided photons through the evanescent wave field with the analyte in the solution surrounding the fiber (

Figure 7). In order to increase the evanescent field effect, fiber tapering is applied either in the form of a tapered tip or of a continuous tapered fiber [

45,

106]. Tapered tips are created by reducing gradually the diameter at the end of an optical fiber down to nanometers. In order to obtain the highest possible sensitivity due to reaction, the recognition biomolecules are immobilized on the tip region with the smallest diameter where the evanescent field is stronger. Continuous tapered fibers have usually a biconical taper, comprised from a region of decreasing diameter, a region of constant diameter called the waist, and a region of increasing diameter [

107]. Sensing is taking place on the waist region where the evanescent field exhibits its higher intensity, whereas the emitted light is collected from the region of increasing diameter [

108]. Fiber optic biosensors have been widely employed in the field of foodborne pathogen detection due to their convenience, small size, lack of electromagnetic interference, cost-effectiveness, high sensitivity and accuracy [

109].

The first label-free approach for the detection of pathogens was realized using a U-bent optical fiber sensor [

110]. Bending a de-cladded fiber into a U-shaped structure enhances the penetration depth of evanescent wave and hence sensitivity of the probe. This system could detect E.

coli in concentrations lower than 10

3 cfu/mL with an assay duration of 1 h. A similar approach employing a plastic fiber optic sensor with a U-shaped sensing probe functionalized with an antibody against E.

coli serotype O55 was employed for E.

coli detection resulting in a LOD of 10

3 cfu/mL for an assay duration of 10 minutes per sample [

111]. Upon exposure of the sensor to bacteria solutions, the output signal decreased with time due to the attachment of the bacteria that increased the refractive index value close to the probe.

Several fiber optic immunosensors employing labels have been also reported for bacteria detection. Thus, tapered fiber tips have been used for detection of Salmonella in culture medium [

112] and E.

coli O157:H7 in ground beef [

113] with LODs of 10

4 and 10

3 cfu/mL, respectively. The first employed silica fibers with tapered tips that were modified with mercaptosilane to facilitate the covalent bonding of an anti-Salmonella antibody, while a second antibody labeled with a fluorescent dye was used as detection antibody. In the second report [

113], polystyrene fibers were first coated with biotinylated bovine serum albumin and then reacted with streptavidin and biotinylated anti-E.

coli antibody. A fluorescently labeled antibody was also used for detection. Polystyrene fibers were also integrated into a portable instrument commercialized under the name RAPTOR

TM. This instrument was used for the detection of S.

typhimurium in rinse-water from sprouted alfalfa seeds through modification of the fibers first with streptavidin and then with a biotinylated antibody [

114]. A second fluorescently labeled antibody was used for detection achieving a LOD of 10

5 cfu/mL. The RAPTOR™ biosensor has been also used to detect Enterococcus

faecalis with a LOD of 5.0x10

5 cells/mL [

115], and L.

monocytogenes with LODs ranging from 10

3 to 4.3x10

3 cfu/mL [

116,

117,

118]. In all cases, sandwich immunoassays were implemented with the exception of [

117] where a fluorescently labeled aptamer (aptamer A8) specific for internalin A, an invasin protein of L.

monocytogenes, was used for detection. A version of RAPTOR

TM that supported multiplexed determinations was applied for the detection of L.

monocytogenes, E.

coli O157:H7 and S.

enterica in several meat products [

119]. The LOD achieved were 50 cfu/mL for S.

enterica and 10

3 cfu/mL for L.

monocytogenes.

Fluorescence resonance energy transfer, i.e., the non-radiative energy transfer from a fluorescent donor molecule to an acceptor one when these two are in close proximity, has been also implemented for detection of S.

typhimurium with an optical fiber tip sensor in ground beef sample [

120]. The anti-Salmonella antibody was labelled with the donor fluorophore (AlexaFluor 546) and protein G was labeled with the acceptor fluorophore (Alexa Fluor 594). Upon binding of S.

typhimurium to the antibody, the induced conformation changes reduced the distance between the donor and acceptor molecules, resulting in increase of emitted fluorescence achieving an LOD of 10

5 cfu/g of sample.

In recent years, fiber optic immunosensors based on surface modifications with nanomaterials show significant improvements compared to conventional fiber optic sensors regarding the speed and the sensitivity of the detection. For example, a fiber optic biosensor modified with zinc oxide (ZnO) nanorods for the detection of E.

coli in water with a LOD of 10

3 cfu/mL was developed [

121].

Fiber optic sensors in which the exposed fiber core has been coated with a gold layer to take advantage of the SPR phenomenon have been also used for bacteria detection. Such a sensor has been employed for the detection of Legionella

pneumophila by a direct assay after modification of the fiber gold-covered area with 11-mercaptoundecanoic to allow the covalent bonding of an anti-L.

pneumophila antibody [

122]. A LOD of 10 cfu/mL was achieved for a direct assay that lasted 1 h. In another report, a fiber optic SPR sensor was modified with MoS

2 nanosheets on which the specific antibodies were attached and a LOD of 94 cfu/mL for E.

coli was achieved compared to 391 cfu/mL received from fibers without MoS

2 nanosheets [

123]. The reports regarding bacteria detection with fiber optic based immunosensors are summarized in

Table 2.

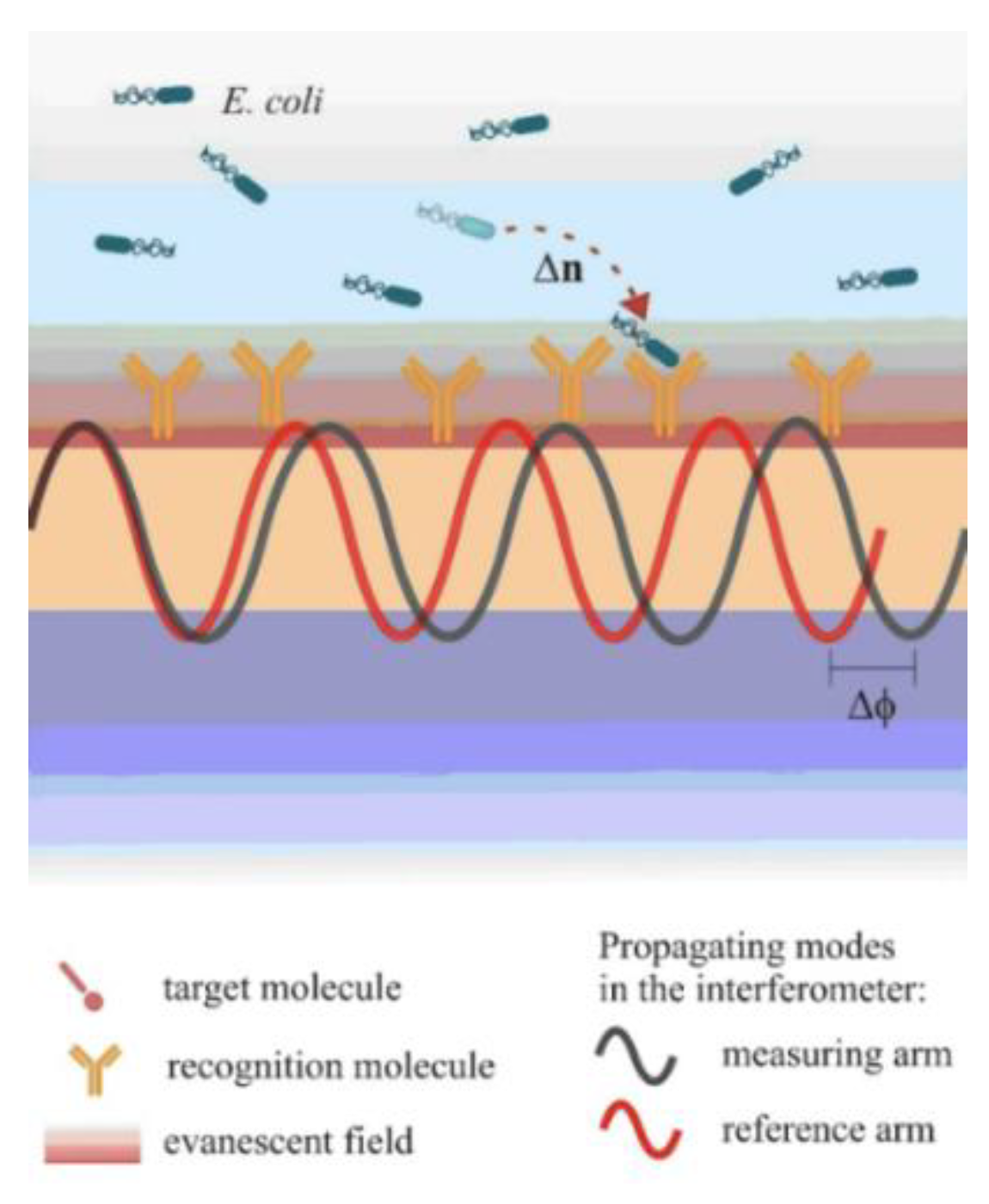

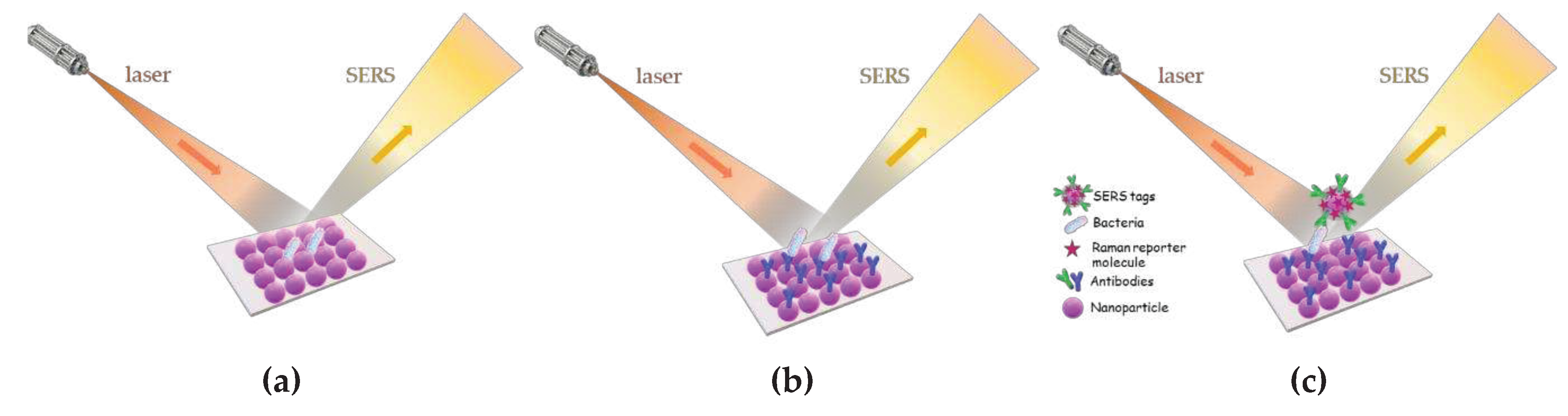

3.1.3. Interferometric immunosensors

Interferometric immunosensors is another category of devices that have been implemented for the detection of different bacteria in food matrices. These sensors could detect refractive index changes down to 10

-8 RIU and have demonstrated excellent analytical performance regarding the determination of analytes in complex matrices [

124,

125]. The most popular configurations of interferometric sensors are Mach-Zehnder (MZI) [

125,

126,

127,

128], Young (YI) [

129], Hartman [

130,

131,

132] and bi-modal interferometers [

133,

134].

In Mach-Zehnder interferometers, a waveguide splits into two arms, one that can detect the variations in the refractive index over its surface through a window in the cladding layer (sensing arm), and the other that is fully covered by the cladding layer and operates as reference (reference arm) [

124,

125]. The two arms combine again after some point to a single waveguide and the output light intensity is monitored. Biomolecular reactions taking place onto the sensing arm window change its surface refractive index and cause a phase difference between the light beams guided in the two arms. Thus, the output light is a cosine function of the input light. This means that the sensitivity to effective refractive index changes would be maximum at the quadrature points and minimum in the vicinity of the extrema. Regarding the geometrical characteristics of the transducer, most MZIs are symmetric, i.e., the sensing and the reference arms have equal length while asymmetric MZIs, i.e., MZIs with different length of the two arms, have been also explored. The majority of MZI-based detection systems implement monochromatic light sources, i.e., lasers, which complicate instrument miniaturization and development of portable systems; therefore broad-band light sources have been explored instead of lasers. To this direction, external broad-band light sources have been coupled to MZIs integrated on the substrate [

126,

127] or silicon light emitting diodes (LED) integrated onto the same silicon chip with planar silicon nitride waveguides have been implemented [

125,

127]. It should be noticed that the detection sensitivities in terms of refractive index achieved with these configurations were comparable to those of MZIs implementing lasers as light sources.

A Young interferometer (YI) consists also of a waveguide divided into two arms by means of a Y-junction. The critical difference between MZIs and YIs is that in the second case, the two waveguides do not combine again but the output light interferes in air and the “interferogram” created is depicted on a CCD array. Thus, in YIs the changes in the effective refractive index over the sensing arm due to binding reactions that cause the phase difference between the two interfering beams is recorded as a shift of the interference fringes [

124]. There are considerably fewer reports of integrated YIs as compared to MZIs; nonetheless, it has been demonstrated that for a particular application YI-based sensors can be more sensitive than an SPR, a grating coupler or a commercially available reflectometric interference spectroscopy (RIfS) sensor.

Hartman interferometers are based on planar waveguides in which the two modes of light, TE and TM, propagate and interact with the adlayer on the same path [

124]. Changes in the refractive index cause phase shifts of the two polarizations that are not equal, because the sensitivity of the two modes to refractive index changes differs.

Bimodal interferometers are the third and most recently developed category of interferometric sensors [

124]. In a bimodal interferometer the transducer is a single waveguide with two different zones; the first supporting a single-mode and a second supporting two-modes (fundamental and first order modes). Those two modes interfere and propagate until they reach the waveguide's output. When refractive index changes occur at the waveguide surface, due to binding reactions, the interference pattern at the waveguide output also changes since the velocity with which the two modes propagate depends on the refractive index of the waveguide adlayer.

The first report for bacteria detection based on interferometric sensors was the immunochemical detection of S.

typhimurium with a Hartman interferometer [

130]. The sensor could detect 5x10

8 cfu/mL of Salmonella in a direct assay that lasted 40 min. An integrated two-channel Hartman interferometer was also applied for the detection of S.

typhimurium in spiked chicken rinse fluid [

132]. Detection by direct binding of Salmonella cells to antibody modified waveguides was compared to a sandwich assay. Both configurations provided a LOD of 10

4 cfu/mL for assay duration of 10 min.

Mach-Zehnder interferometers (MZIs) have been also employed for bacteria detection. Thus, integrated onto silicon chips MZIs were modified with an antibody against L.

monocytogenes following a chemical activation protocol specific for silicon nitride so as to limit antibody attachment to the sensing windows areas [

126]. The protocol consisted of chip treatment with HF for creation of amine groups onto the silicon nitride followed by reaction with glutaraldehyde to enable covalent bonding of antibody through their free amine group. A LOD of 10

5 cfu/mL was achieved for a direct binding 15-min assay. In another report the MZIs waveguide was formed by patterning a photoresist layer deposited on a glass coverslip [

127]. The immobilization of an antibody against E.

coli was performed after modification of sensing arm with an aminosilane and subsequent activation with glutaraldehyde. The assay duration was 10 min and the LOD 10

6 cfu/mL. In another report, a chip integrating ten MZIs along with the respective silicon light emitting diodes was employed for the simultaneous detection of S.

typhimurium and E.

coli through a competitive immunoassay format [

128]. The chip was activated with aminosilane and then the liposaccharides of S.

typhimurium and E.

coli were spotted onto the sensing arm windows of different MZIs of the chip and immobilized through physical adsorption. MZIs spotted with the blocking protein (bovine serum albumin) were used as reference sensors. For the assay, mixtures of calibrators or samples with the bacteria specific antibodies were run over the chip followed by reaction with biotinylated secondary antibodies and streptavidin for signal enhancement. Following this format, LODs of 40 cfu/mL for S. typhimurium and 110 cfu/mL in both water and milk were achieved for a 10-min assay [

128].

Regarding Young interferometers there are no reports for detection of bacteria, although they have been employed for the immunochemical detection of viruses, and more specifically of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) achieving a LOD of 850 particles/mL [

129]. On the other hand, the label-free detection of B.

cereus and E.

coli with a bimodal interferometric immunosensor has been also reported [

132]. The immobilization of antibodies was carried out either by physical adsorption of aminosilane modified chips or by covalent binding to chips modified with a carboxysilane after conversion of surface carboxyl groups to active ester groups. The device could detect 70 cfu/mL of B.

cereus in 12.5 min and 40 cfu/mL of E.

coli detection in 25 min. The same bimodal interferometric sensor was also applied for the detection of multidrug-resistance bacteria genes without amplification through a DNA hybridization assay [

133].

Table 3 summarizes the application area and analytical performance of integrated interferometric sensors.