Submitted:

16 June 2023

Posted:

19 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

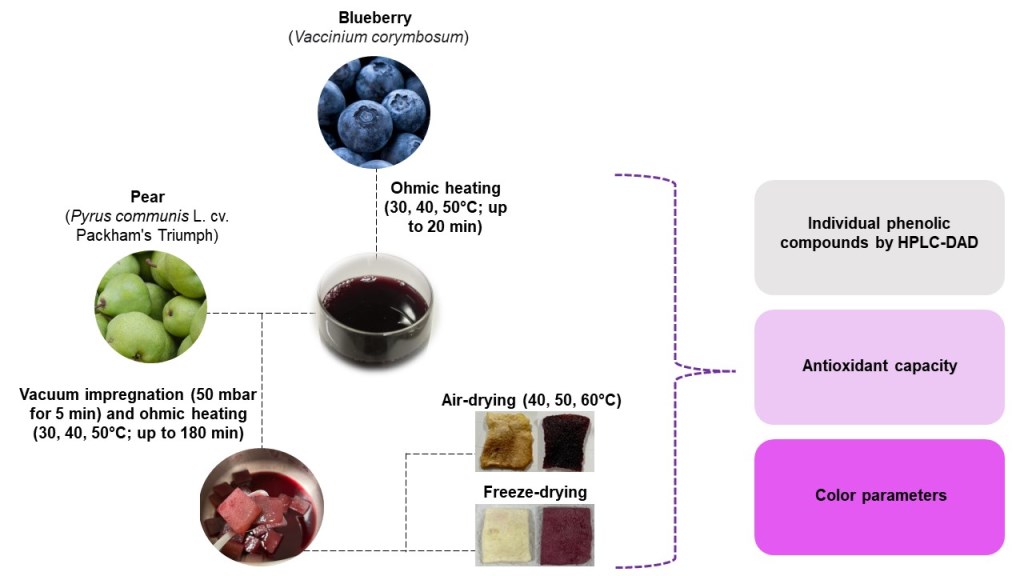

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Samples

2.3. Blueberry treatment by OH

2.4. VI-OH of pear slices with blueberry juice

2.5. Drying processes of pear slices with blueberry juice

2.6. Total phenolic, flavonoid, and anthocyanin contents

2.6.1. Total phenolic content (TPC)

2.6.2. Total flavonoid content (TFC)

2.6.3. Total monomeric anthocyanin content (TMA)

2.7. Antioxidant capacity

2.7.1. DPPH

2.7.2. FRAP

2.8. Color parameters

2.9. Phenolic compounds by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)

2.10. Statistical analysis

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Blueberry treatment by OH

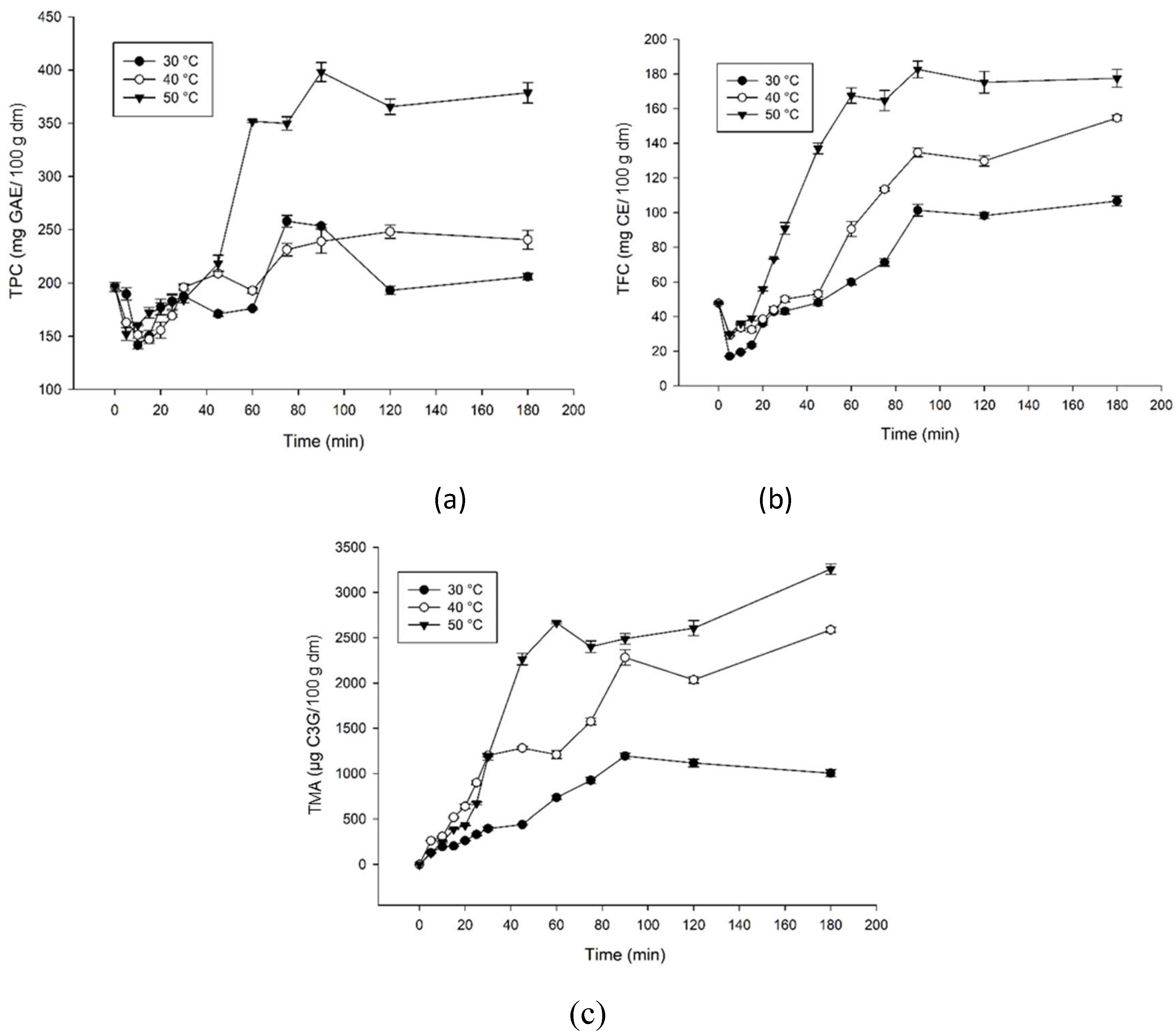

3.2. VI-OH of pear slices with blueberry juice

3.3. Drying processes of pear slices with blueberry juice

4. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brahem, M.; Renard, C.M.G.C.; Eder, S.; Loonis, M.; Ouni, R.; Mars, M.; Le Bourvellec, C. Characterization and quantification of fruit phenolic compounds of European and Tunisian pear cultivars. Food Res Int 2017, 95, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Li, X.; Wang, T.; Gao, W. Nutritional composition of pear cultivars (Pyrus Spp.). In Nutritional Composition of Fruit Cultivars; Elsevier, 2016; pp. 573–608.

- Muñoz-Fariña, O.; López-Casanova, V.; García-Figueroa, O.; Roman-Benn, A.; Ah-Hen, K.; Bastias-Montes, J.M.; Quevedo-León, R.; Ravanal-Espinosa, M.C. Bioaccessibility of phenolic compounds in fresh and dehydrated blueberries (Vaccinium Corymbosum L.). Food Chem Adv 2023, 2, 100171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, A.M.; Angeloni, S.; Abouelenein, D.; Acquaticci, L.; Xiao, J.; Sagratini, G.; Maggi, F.; Vittori, S.; Caprioli, G. A New HPLC-MS/MS method for the simultaneous determination of 36 polyphenols in blueberry, strawberry and their commercial products and determination of antioxidant activity. Food Chem 2022, 367, 130743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolniak-Ostek, J.; Kłopotowska, D.; Rutkowski, K.P.; Skorupińska, A.; Kruczyńska, D.E. Bioactive compounds and health-promoting properties of pear (Pyrus Communis L.) fruits. Molecules 2020, 25, 4444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker Pertuzatti, P.; Teixeira Barcia, M.; Gómez-Alonso, S.; Teixeira Godoy, H.; Hermosin-Gutierrez, I. Phenolics Profiling by HPLC-DAD-ESI-MSn aided by principal component analysis to classify rabbiteye and highbush blueberries. Food Chem 2021, 340, 127958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia, M.P.; Alibas, I. Influence of the drying methods on color, vitamin C, anthocyanin, phenolic compounds, antioxidant activity, and in vitro bioaccessibility of blueberry fruits. Food Biosci 2021, 42, 101179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavez-Guajardo, C.; Ferreira, S.R.S.; Mazzutti, S.; Guerra-Valle, M.E.; Sáez-Trautmann, G.; Moreno, J. Influence of in vitro digestion on antioxidant activity of enriched apple snacks with grape juice. Foods 2020, 9, 1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Valle, M.E.; Moreno, J.; Lillo-Pérez, S.; Petzold, G.; Simpson, R.; Nuñez, H. Enrichment of apple slices with bioactive compounds from pomegranate cryoconcentrated juice as an osmodehydration agent. J Food Qual 2018, 2018, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J.; Gonzales, M.; Zúñiga, P.; Petzold, G.; Mella, K.; Muñoz, O. Ohmic heating and pulsed vacuum effect on dehydration processes and polyphenol component retention of osmodehydrated blueberries (Cv. Tifblue). Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol 2016, 36, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Sastry, S.K. Ohmic heating assisted lye peeling of pears. J Food Sci 2018, 83, 1292–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J.; Echeverria, J.; Silva, A.; Escudero, A.; Petzold, G.; Mella, K.; Escudero, C. Apple snack enriched with L-arginine using vacuum impregnation/ohmic heating technology. Food Sci Technol Int 2017, 23, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akman, P.K.; Uysal, E.; Ozkaya, G.U.; Tornuk, F.; Durak, M.Z. Development of probiotic carrier dried apples for consumption as snack food with the impregnation of Lactobacillus Paracasei. LWT 2019, 103, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbiah, V.; Duan, X.; Agar, O.T.; Dunshea, F.R.; Barrow, C.J.; Suleria, H.A.R. Comparative study on the effect of different drying techniques on phenolic compounds in australian beach-cast brown seaweeds. Algal Res 2023, 72, 103140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC Official Methods of Analysis; 18th ed.; AOAC International: Gaithersburg, 2010.

- Waterhouse, A.L. Determination of total phenolics. In Current Protocols in Food Analytical Chemistry; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dewanto, V.; Wu, X.; Adom, K.K.; Liu, R.H. Thermal processing enhances the nutritional value of tomatoes by increasing total antioxidant activity. J Agric Food Chem 2002, 50, 3010–3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Durst, R.W.; Wrolstad, R.E.; Eisele, T.; Giusti, M.M.; Hach, J.; Hofsommer, H.; Koswig, S.; Krueger, D.A.; Kupina; , S. ; et al. Determination of total monomeric anthocyanin pigment content of fruit juices, beverages, natural colorants, and wines by the pH differential method: collaborative study. J AOAC Int 2005, 88, 1269–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaipong, K.; Boonprakob, U.; Crosby, K.; Cisneros-Zevallos, L.; Hawkins Byrne, D. Comparison of ABTS, DPPH, FRAP, and ORAC assays for estimating antioxidant activity from guava fruit extracts. J Food Comp Anal 2006, 19, 669–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.F.; Strain, J.J. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: the FRAP assay. Anal Biochem 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, A.; Hermosín-Gutiérrez, I.; Mardones, C.; Vergara, C.; Herlitz, E.; Vega, M.; Dorau, C.; Winterhalter, P.; von Baer, D. Polyphenols and antioxidant activity of calafate (Berberis Microphylla) fruits and other native berries from southern Chile. J Agric Food Chem 2010, 58, 6081–6089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkis, J.R.; Jaeschke, D.P.; Tessaro, I.C.; Marczak, L.D.F. Effects of ohmic and conventional heating on anthocyanin degradation during the processing of blueberry pulp. LWT 2013, 51, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zou, B.; Li, X.; Dai, R. Ohmic heating in fruit and vegetable processing: quality characteristics, enzyme inactivation, challenges and prospective. Trends Food Sci Technol 2021, 118, 601–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Gómez, J.; Varo, M.Á.; Mérida, J.; Serratosa, M.P. Influence of drying processes on anthocyanin profiles, total phenolic compounds and antioxidant activities of blueberry (Vaccinium Corymbosum). LWT 2020, 120, 108931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enaru, B.; Drețcanu, G.; Pop, T.D.; Stǎnilǎ, A.; Diaconeasa, Z. Anthocyanins: factors affecting their stability and degradation. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrera-Balandrano, D.D.; Chai, Z.; Beta, T.; Feng, J.; Huang, W. Blueberry anthocyanins: an updated review on approaches to enhancing their bioavailability. Trends Food Sci Technol 2021, 118, 808–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeb, A. Concept, mechanism, and applications of phenolic antioxidants in foods. J Food Biochem 2020, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, F.; Zhong, Y. Measurement of antioxidant activity. J Funct Foods 2015, 18, 757–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negri Rodríguez, L.M.; Arias, R.; Soteras, T.; Sancho, A.; Pesquero, N.; Rossetti, L.; Tacca, H.; Aimaretti, N.; Rojas Cervantes, M.L.; Szerman, N. Comparison of the quality attributes of carrot juice pasteurized by ohmic heating and conventional heat treatment. LWT 2021, 145, 111255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debbarma, T.; Thangalakshmi, S.; Tadakod, M.; Singh, R.; Singh, A. Comparative analysis of ohmic and conventional heat-treated carrot juice. J Food Process Preserv 2021, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvishi, H.; Salami, P.; Fadavi, A.; Saba, M.K. Processing kinetics, quality and thermodynamic evaluation of mulberry juice concentration process using ohmic heating. Food Bioprod Process 2020, 123, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, J.-Y.; Gao, W.-Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.-Y.; Cao, J.-G.; Huang, L.-Q. Chemical composition and anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities of eight pear cultivars. J Agric Food Chem 2012, 60, 8738–8744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Barrow, C.J.; Dunshea, F.R.; Suleria, H.A.R. A Comparative investigation on phenolic composition, characterization and antioxidant potentials of five different Australian grown pear varieties. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abalos, R.A.; Naef, E.F.; Aviles, M.V.; Gómez, M.B. Vacuum impregnation: a methodology for the preparation of a ready-to-eat sweet potato enriched in polyphenols. LWT 2020, 131, 109773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tylewicz, U.; Tappi, S.; Mannozzi, C.; Romani, S.; Dellarosa, N.; Laghi, L.; Ragni, L.; Rocculi, P.; Dalla Rosa, M. Effect of pulsed electric field (PEF) pre-treatment coupled with osmotic dehydration on physico-chemical characteristics of organic strawberries. J Food Eng 2017, 213, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J.; Zúñiga, P.; Dorvil, F.; Petzold, G.; Mella, K.; Bugueño, G. Osmodehydration assisted by ohmic heating/pulse vacuum in apples (cv. fuji): retention of polyphenols during refrigerated storage. Int J Food Sci Technol 2017, 52, 1203–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, F.M.; Ersus Bilek, S. Ultrasound-assisted vacuum impregnation on the fortification of fresh-cut apple with calcium and black carrot phenolics. Ultrason Sonochem 2018, 48, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albuquerque, B.R.; Heleno, S.A.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Phenolic compounds: current industrial applications, limitations and future challenges. Food Funct 2021, 12, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giada, M. de L.R. Food Phenolic compounds: main classes, sources and their antioxidant power. In Oxidative Stress and Chronic Degenerative Diseases - A Role for Antioxidants; InTech, 2013; pp. 87–112.

- Alara, O.R.; Abdurahman, N.H.; Ukaegbu, C.I. Extraction of phenolic compounds: a review. Curr Res Food Sci 2021, 4, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuolo, M.M.; Lima, V.S.; Maróstica Junior, M.R. Phenolic compounds. In Bioactive Compounds; Elsevier, 2019; pp. 33–50 ISBN 9780128147757.

- de la Rosa, L.A.; Moreno-Escamilla, J.O.; Rodrigo-García, J.; Alvarez-Parrilla, E. Phenolic compounds. In Postharvest Physiology and Biochemistry of Fruits and Vegetables; Elsevier, 2019; pp. 253–271 ISBN 9780128132784.

- Öztürk, A.; Demirsoy, L.; Demirsoy, H.; Asan, A.; Gül, O. Phenolic compounds and chemical characteristics of pears (Pyrus Communis L.). Int J Food Prop 2015, 18, 536–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaudanskas, M.; Zymonė, K.; Viškelis, J.; Klevinskas, A.; Janulis, V. Determination of the phenolic composition and antioxidant activity of pear extracts. J Chem 2017, 2017, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Saroglu, O.; Karadag, A.; Diaconeasa, Z.; Zoccatelli, G.; Conte-Junior, C.A.; Gonzalez-Aguilar, G.A.; Ou, J.; Bai, W.; Zamarioli, C.M.; et al. Available technologies on improving the stability of polyphenols in food processing. Food Front 2021, 2, 109–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes-Ávila, J.; López-Angulo, G.; Delgado-Vargas, F. Tannins in fruits and vegetables: chemistry and biological functions. In Fruit and Vegetable Phytochemicals; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: Chichester, UK, 2017; pp. 221–268. [Google Scholar]

- Das, A.K.; Islam, Md.N.; Faruk, Md.O.; Ashaduzzaman, Md.; Dungani, R. Review on tannins: extraction processes, applications and possibilities. S Afr J Bot 2020, 135, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Villalba, R.; González-Sarrías, A.; Giménez-Bastida, J.A.; Selma, M.V.; Espín, J.C.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A. Metabolism of dietary (poly)phenols by the gut microbiota. In Comprehensive Gut Microbiota; Elsevier, 2022; pp. 149–175.

- Chen, Z.; Zheng, S.; Li, L.; Jiang, H. Metabolism of flavonoids in human: a comprehensive review. Curr Drug Metab 2014, 15, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosme, P.; Rodríguez, A.B.; Espino, J.; Garrido, M. Plant phenolics: bioavailability as a key determinant of their potential health-promoting applications. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Temperature (°C) | Time (min) | TPC (mg GAE/100 mL) |

TFC (mg CE/100 mL) |

TMA (µg C3G/100 mL) |

Antioxidant capacity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPPH (µmol TE/100 mL) |

FRAP (µmol TE/100 mL) |

|||||

| Non-treated juice | 152.00 ± 3.14 a | 90.93 ± 0.50 a | 354.03 ± 9.23 a | 327.94 ± 5.54 a | 403.84 ± 0.84 a | |

| 30 | 5 | 156.54 ± 3.27 ab | 97.45 ± 1.09 b | 473.15 ± 9.64 b | 343.77 ± 5.02 b | 403.24 ± 2.80 a |

| 10 | 161.69 ± 4.48 b | 96.98 ± 3.76 b | 642.35 ± 11.23 d | 371.00 ± 7.94 c | 409.77 ± 1.66 ab | |

| 15 | 174.12 ± 2.28 cd | 124.49 ± 0.41 e | 1074.72 ± 19.42 hi | 419.88 ± 3.15 e | 428.97 ± 7.40 c | |

| 20 | 188.97 ± 6.44 f | 134.46 ± 1.64 g | 1219.04 ± 23.26 j | 430.16 ± 2.35 e | 464.97 ± 7.52 e | |

| 40 | 5 | 175.93 ± 2.28 cd | 110.02 ± 1.64 c | 512.53 ± 19.26 c | 335.16 ± 9.46 ab | 425.04 ± 7.07 bc |

| 10 | 178.36 ± 1.28 de | 118.09 ± 2.49 d | 826.34 ± 11.53 e | 365.44 ± 7.51 c | 430.84 ± 8.00 c | |

| 15 | 179.27 ± 2.57 de | 122.83 ± 2.05 e | 1024.12 ± 34.24 g | 366.27 ± 5.91 c | 438.17 ± 9.38 cd | |

| 20 | 182.30 ± 2.28 e | 136.59 ± 1.48 gh | 1085.53 ± 16.13 i | 382.11 ± 9.14 d | 449.10 ± 9.20 de | |

| 50 | 5 | 170.78 ± 2.09 c | 118.32 ± 3.96 d | 442.53 ± 11.53 b | 330.72 ± 4.73 a | 428.04 ± 15.95 c |

| 10 | 172.90 ± 0.90 cd | 129.71 ± 1.06 f | 969.23 ± 28.24 f | 361.83 ± 9.27 c | 448.44 ± 19.06 de | |

| 15 | 195.03 ± 6.05 g | 148.57 ± 0.50 i | 1040.42 ± 19.53 gh | 392.38 ± 4.88 d | 519.10 ± 12.23 f | |

| 20 | 201.09 ± 1.57 h | 139.43 ± 1.48 h | 1035.14 ± 16.35 g | 427.11 ± 2.09 e | 562.24 ± 3.67 g | |

| Time (min) |

DPPH | FRAP | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 °C | 40 °C | 50 °C | 30 °C | 40 °C | 50 °C | |

| Non-treated pear | 630.53 ± 3.62 c,A | 630.93 ± 1.45 d,A | 630.54 ± 1.76 c,A | 619.54 ± 11.53 e,A | 619.73 ± 11.24 f,A | 619.54 ± 11.23 d,A |

| 5 | 534.67 ± 6.54 a,C | 471.35 ± 3.56 a,B | 454.74 ± 9.53 a,A | 402.42 ± 5.35 a,B | 371.43 ± 7.45 a,A | 401.76 ± 5.23 a,B |

| 10 | 521.24 ± 11.25 a,B | 478.74 ± 18.54 ab,A | 476.35 ± 20.64 a,A | 402.73 ± 3.73 a,A | 407.53 ± 3.84 b,A | 443.24 ± 11.23 b,B |

| 15 | 549.42 ± 7.63 a,B | 499.35 ± 10.45 ab,A | 576.19 ± 18.45 b,C | 416.35 ± 16.53 ab,A | 427.54 ± 3.35 bc,A | 535.74 ± 2.34 c,B |

| 20 | 545.56 ± 19.54 a,AB | 515.74 ± 13.45 bc,A | 553.24 ± 15.74 b,B | 432.74 ± 5.63 b,A | 447.45 ± 12.64 c,A | 794.05 ± 11.35 e,B |

| 25 | 584.86 ± 22.74 b,B | 548.73 ± 6.63 c,A | 624.74 ± 20.02 c,C | 435.63 ± 10.63 bc,A | 488.24 ± 11.35 d,B | 833.34 ± 5.36 f,C |

| 30 | 617.92 ± 21.34 bc,A | 656.43 ± 19.45 d,A | 730.93 ± 21.03 d,B | 456.23 ± 11.73 c,A | 561.63 ± 17.36 e,B | 994.56 ± 10.64 g,C |

| 45 | 644.23 ± 26.75 c,A | 718.03 ± 4.73 e,B | 987.93 ± 12.64 e,C | 499.92 ± 7.34 d,A | 702.02 ± 27.74 h,B | 1111.82 ± 35.54 h,C |

| 60 | 638.73 ± 29.42 c,A | 750.82 ± 25.34 e,B | 974.55 ± 7.95 e,C | 615.03 ± 11.03 e,A | 663.06 ± 9.34 g,A | 1377.45 ± 30.63 k,B |

| 75 | 746.35 ± 11.02 d,A | 903.35 ± 18.12 f,B | 998.63 ± 12.64 e,C | 781.53 ± 19.85 h,B | 702.34 ± 24.53 h,A | 1222.34 ± 16.35 i,C |

| 90 | 747.93 ± 3.24 d,A | 952.30 ± 3.63 g,B | 1061.83 ± 6.63 f,C | 741.46 ± 2.39 g,A | 886.66 ± 28.13 j,B | 1278.64 ± 24.35 j,C |

| 120 | 756.82 ± 10.86 d,A | 1046.26 ± 30.2 h,B | 1044.92 ± 22.73 f,B | 672.14 ± 5.98 f,A | 743.25 ± 6.84 i,B | 1204.35 ± 5.63 i,C |

| 180 | 755.64 ± 36.92 d,A | 1197.11 ± 58.64 i,B | 1109.44 ± 19.46 g,B | 813.63 ± 26.34 i,A | 1124.45 ± 32.35 k,B | 1278.34 ± 13.36 j,C |

| Sample | TPC (mg GAE/100 g dm) |

TFC (mg CE/100 g dm) |

TMA (µg C3G/100 g dm) |

Antioxidant capacity | Color parameters | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPPH (µmol TE/100 g dm) |

FRAP (µmol TE/100 g dm) |

L* | a* | b* | ||||

| P | 228.03 ± 5.74 g | 84.76 ± 5.31 e | - | 838.42 ± 8.79 d | 876.34 ± 12.54 d | 76.16 ± 2.75 e | -3.36 ± 0.10 a | 17.86 ± 0.56 d |

| P40 | 24.16 ± 1.25 abc | 3.42 ± 0.30 ab | - | 35.27 ± 1.24 a | 38.24 ± 1.12 a | 48.23 ± 1.51 c | 13.17 ± 0.40 e | 32.86 ± 1.43 fg |

| P50 | 23.82 ± 4.43 ab | 1.82 ± 0.08 a | - | 33.74 ± 1.52 a | 37.25 ± 1.53 a | 46.33 ± 1.93 c | 14.28 ± 0.65 f | 32.58 ± 1.36 f |

| P60 | 52.17 ± 2.45 cd | 6.74 ± 0.34 b | - | 127.36 ± 3.35 b | 145.25 ± 5.36 b | 38.33 ± 1.98 b | 13.59 ± 0.78 ef | 26.33 ± 1.44 e |

| PF | 8.65 ± 0.24 a | 1.21 ± 0.04 a | - | 30.73 ± 1.03 a | 35.23 ± 1.35 a | 70.43 ± 2.66 d | 7.75 ± 0.44 d | 34.40 ± 1.67 g |

| PI | 299.90 ± 7.50 h | 120.26 ± 5.43 f | 6290.02 ± 100.23 d | 1031.85 ± 14.42 e | 1097.43 ± 19.42 e | 20.57 ± 0.83 a | 6.16 ± 0.35 c | 1.43 ± 0.09 ab |

| PI40 | 67.33 ± 3.83 de | 12.73 ± 0.51 c | 1690.27 ± 50.24 bc | 136.73 ± 2.35 b | 153.45 ± 5.24 b | 18.86 ± 0.94 a | 2.08 ± 0.10 b | 1.32 ± 0.09 a |

| PI50 | 118.46 ± 6.83 f | 12.14 ± 0.45 c | 1180.53 ± 30.74 a | 123.27 ± 3.69 b | 142.53 ± 6.34 b | 21.50 ± 0.95 a | 6.24 ± 0.49 c | 3.11 ± 0.21 b |

| PI60 | 95.03 ± 2.75 ef | 15.64 ± 0.93 cd | 1900.62 ± 100.27 c | 218.12 ± 5.47 c | 254.78 ± 5.35 c | 19.26 ± 0.73 a | 1.73 ± 0.15 b | 1.29 ± 0.07 a |

| PIF | 47.64 ± 2.54 bcd | 18.25 ± 1.01 d | 1490.31 ± 110.71 b | 136.03 ± 4.24 b | 155.84 ± 4.24 b | 36.08 ± 2.07 b | 13.44 ± 0.61 e | 12.58 ± 0.83 c |

| Phenolic compound |

Blueberry juice (mg/100 mL) |

Pear slices (mg/100 g dry matter) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | P40 | P50 | P60 | PF | PI | PI40 | PI50 | PI60 | PIF | ||

| Anthocyanin | |||||||||||

| Pelargonin | 62.22 ± 2.62 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| Cyanidin 3-glucosidase | 3.24 ± 0.15 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| Petunidin 3-glucosidase | 6.83 ± 0.31 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| Cyanidin | 23.55 ± 1.09 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 20.18 ± 0.90 b | 0.76 ± 0.05 a | 0.69 ± 0.03 a | 0.56 ± 0.03 a | 0.87 ± 0.04 a |

| Malvidin | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| Non-anthocyanin flavonoid | |||||||||||

| Epigallocatechin | 125.47 ± 5.65 | 169.98 ± 5.90 f | 34.10 ± 1.51 bc | 35.86 ± 1.46 bc | 40.91 ± 1.75 c | 11.33 ± 0.58 a | 347.92 ± 15.95 g | 62.39 ± 2.97 d | 58.32 ± 2.45 d | 80.48 ± 3.69 e | 27.36 ± 1.27 b |

| Catechin | 18.49 ± 1.02 | 35.69 ± 1.60 d | 24.13 ± 1.09 ab | 25.44 ± 0.91 b | 31.01 ± 1.43 c | 23.49 ± 0.89 ab | 68.43 ± 2.82 e | 22.27 ± 0.95 a | 25.38 ± 0.90 b | 31.89 ± 1.60 c | 25.12 ± 1.08 b |

| Epigallocatechingallate | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| Epicatechin | 30.81 ± 1.50 | 27.48 ± 1.41 g | 5.53 ± 0.28 c | 5.63 ± 0.27 c | 6.61 ± 0.30 d | 7.75 ± 0.29 e | 9.51 ± 0.47 f | 2.58 ± 0.12 a | 2.64 ± 0.11 ab | 3.05 ± 0.14 ab | 4.51 ± 0.17 c |

| Myricetin | 8.84 ± 0.45 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 9.98 ± 0.39 c | 2.14 ± 0.09 a | 2.00 ± 0.10 a | 1.91 ± 0.08 a | 2.62 ± 0.10 b |

| Quercetin | 2.28 ± 0.10 | nd | 0.36 ± 0.02 a | 0.48 ± 0.02 b | 0.55 ± 0.03 c | 0.35 ± 0.02 a | nd | 0.66 ± 0.03 d | 0.75 ± 0.03 e | 0.96 ± 0.05 f | 0.67 ± 0.03 d |

| Phenolic acid | |||||||||||

| Gallic acid | 3.31 ± 0.14 | 8.08 ± 0.30 g | 7.70 ± 0.25 f | 7.24 ± 0.22 e | 6.69 ± 0.27 d | 7.01 ± 0.22 de | 4.73 ± 0.16 c | 4.36 ± 0.15 b | 4.18 ± 0.16 b | 3.80 ± 0.14 a | 4.01 ± 0.15 ab |

| Caffeic acid | 5.17 ± 0.24 | 2.44 ± 0.11 e | 0.85 ± 0.03 c | 0.87 ± 0.04 c | 0.93 ± 0.04 c | 0.90 ± 0.04 c | 1.75 ± 0.07 d | 0.53 ± 0.02 a | 0.59 ± 0.03 ab | 0.62 ± 0.03 b | 0.59 ± 0.03 ab |

| p-Coumaric acid | 3.04 ± 0.14 | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| Sum | 293.25 ± 7.45 | 243.68 ± 4.88 | 72.68 ± 2.50 | 75.52 ± 2.73 | 86.69 ± 2.97 | 50.83 ± 1.88 | 462.49 ± 18.53 | 95.70 ± 3.97 | 94.56 ± 3.37 | 123.27 ± 4.69 | 65.74 ± 2.56 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).