Submitted:

16 June 2023

Posted:

16 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

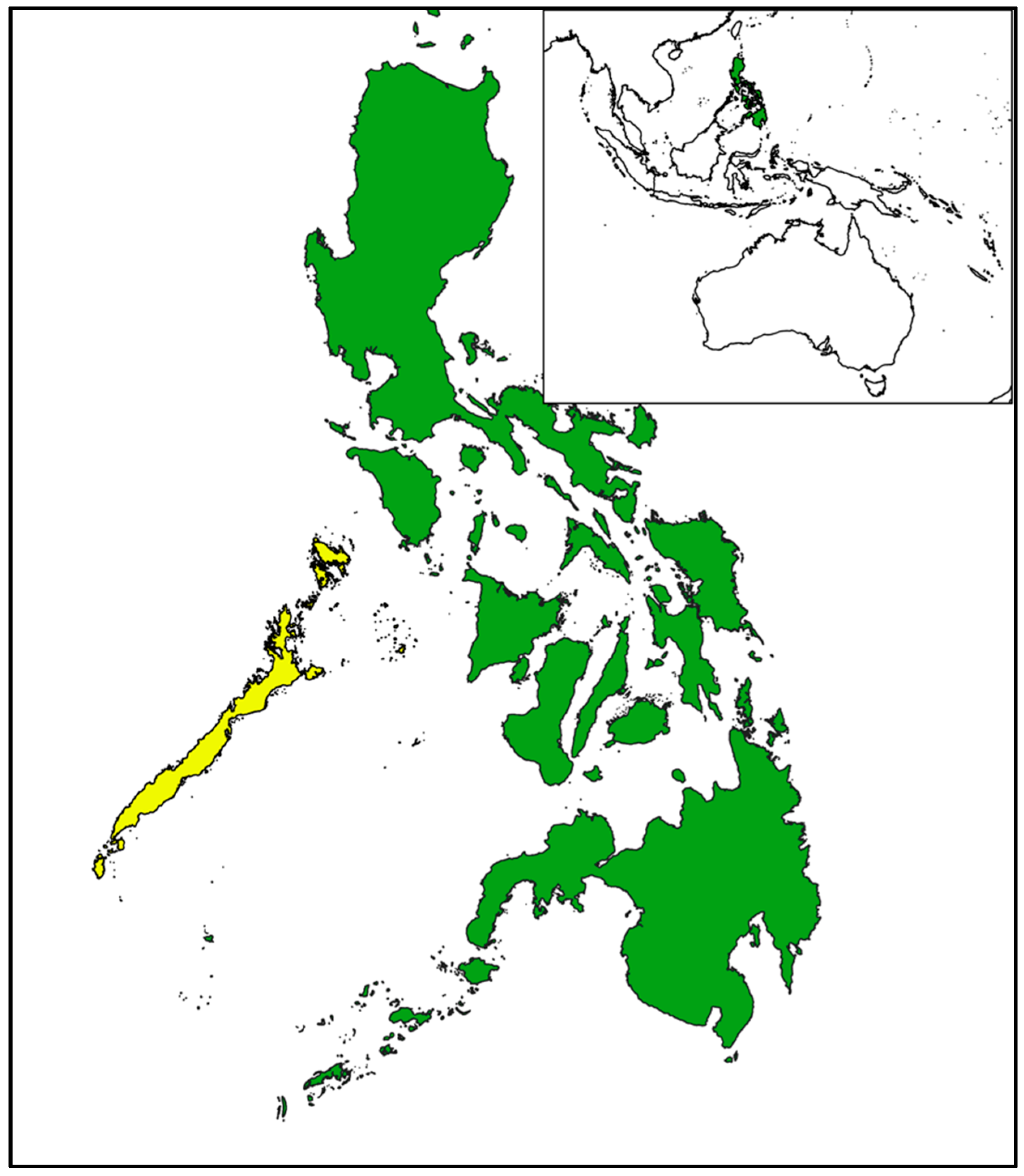

2.1. Study site and sample collection

2.2. X-ray fluorescence

2.2. 13C and 15N stable isotope analysis

3. Statistical analyses

4. Results

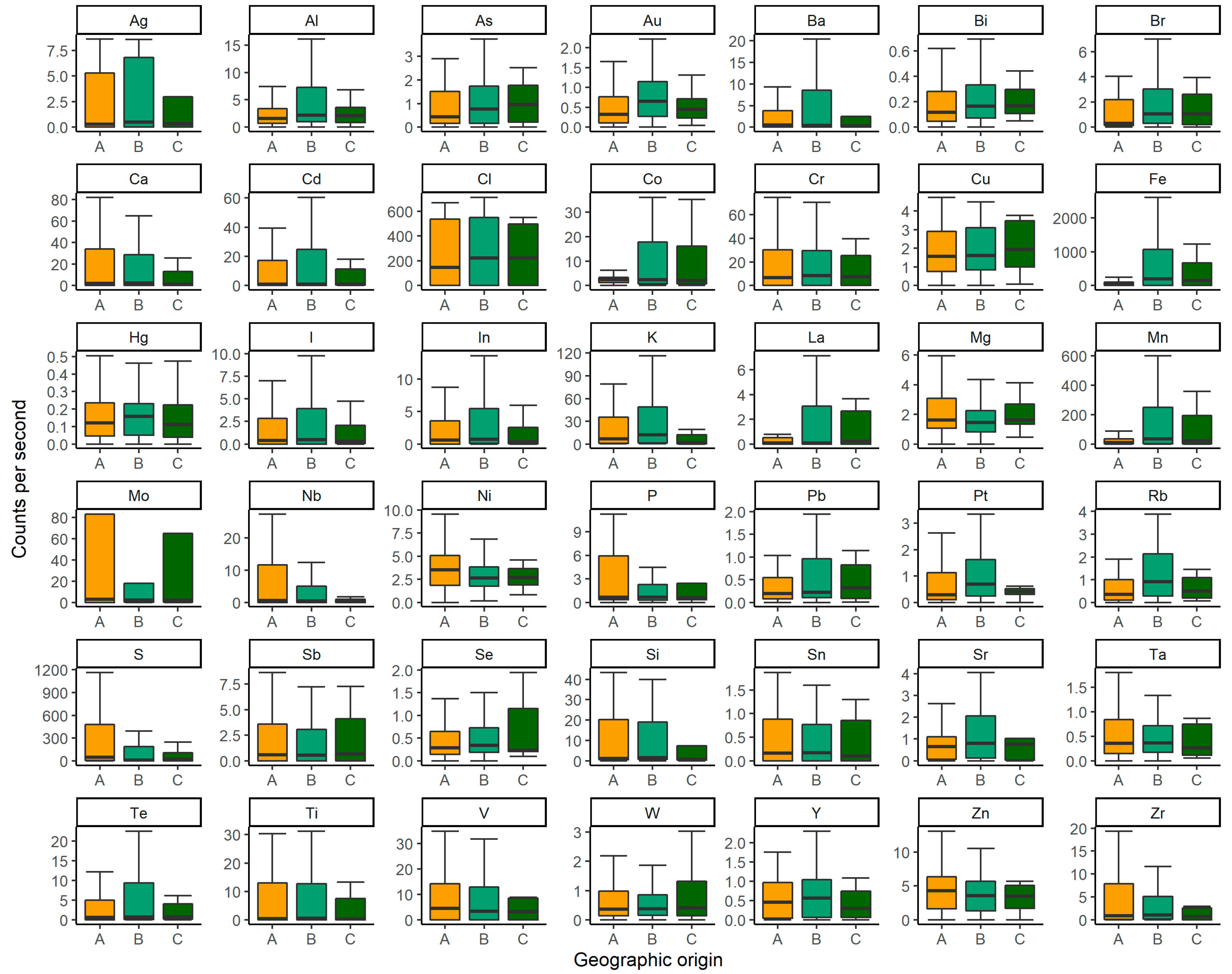

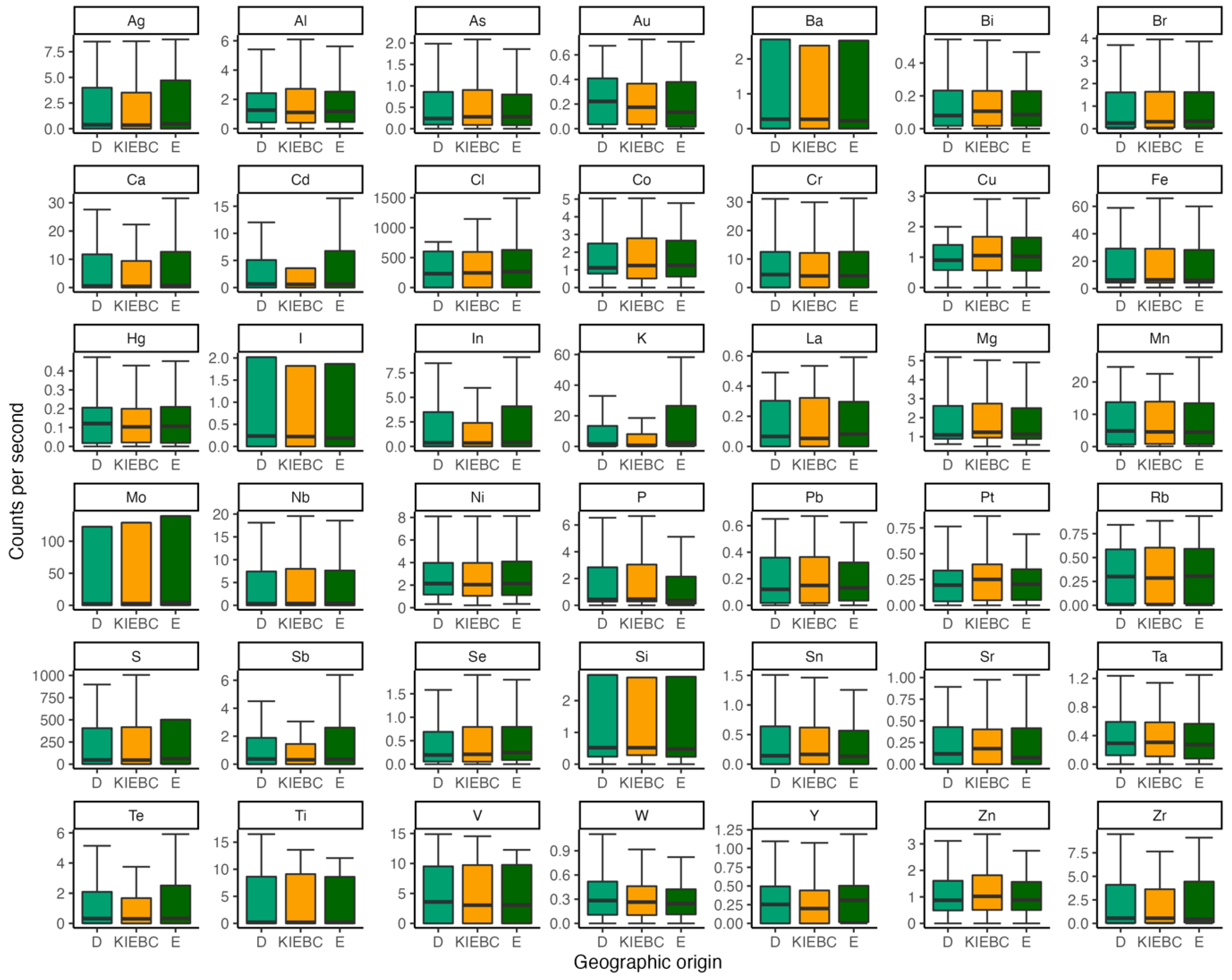

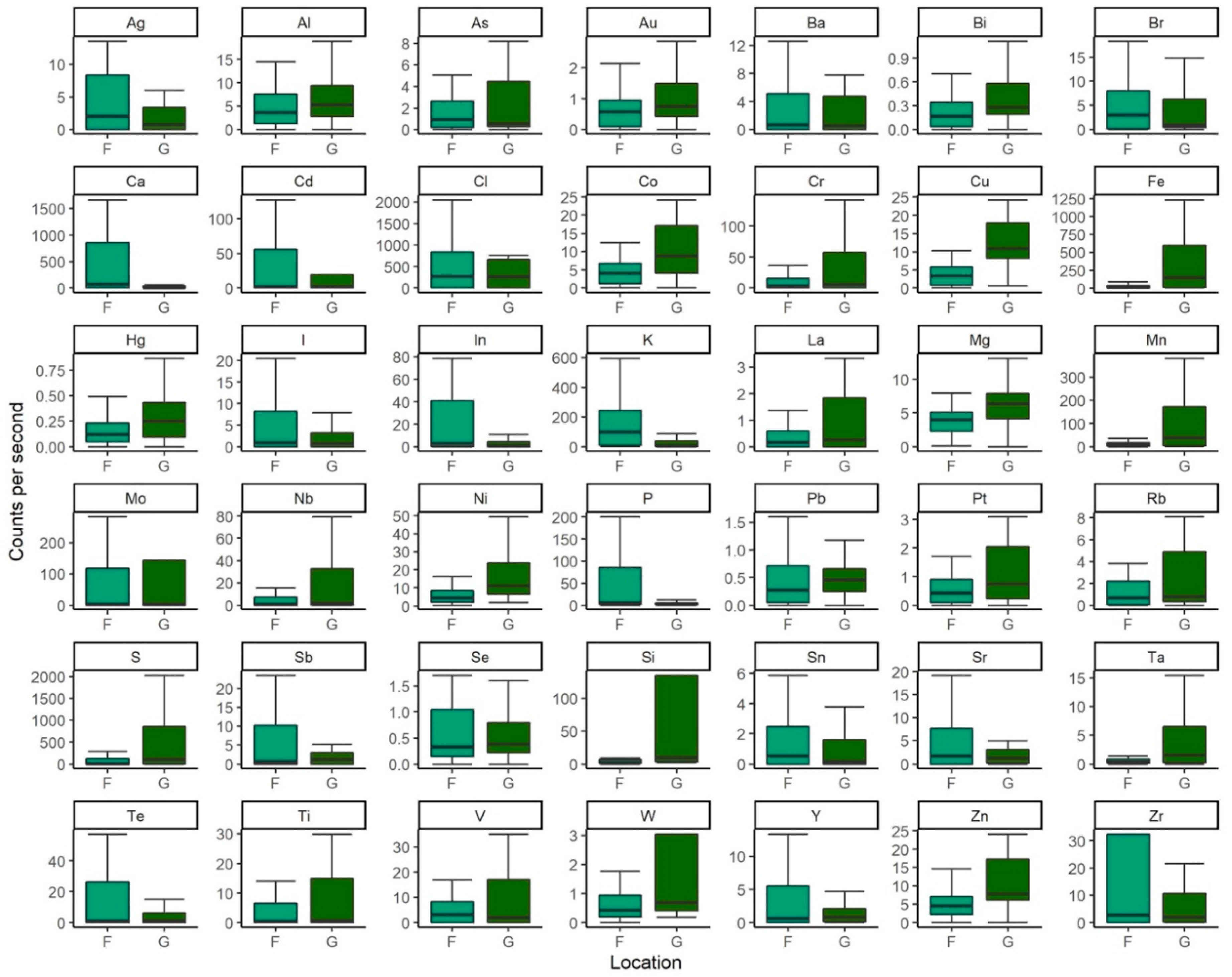

4.1. X-ray fluorescence

4.2. 13C and 15N stable isotopes

4.3. Predictive stable isotope models

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- Zimmerman, M.E., The Black Market for Wildlife: Combating Transnational Organized Crime in the Illegal Wildlife Trade. Journal of Transnational Law, 2003. 36: p. 1657-1689.

- Symes, W.S., et al., The gravity of wildlife trade. Biological Conservation, 2018. 218: p. 268-276. [CrossRef]

- Scheffers, B.R., et al., Global wildlife trade across the tree of life. Science, 2019. 366: p. 71-76.

- Rehman, A., et al., Use of DNA Barcoding to Control the Illegal Wildlife Trade: A CITES Case Report from Pakistan. Journal of Bioresource Management, 2015. 2(2). [CrossRef]

- Omifolaji, J.K., et al., Dissecting the illegal pangolin trade in China: An insight from seizures data reports. Nature Conservation, 2022. 46: p. 17-38. [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.G., et al., Quantitative methods of identifying the key nodes in the illegal wildlife trade network. Proceedings National Academy of Science USA, 2015. 112(26): p. 7948-53. [CrossRef]

- Gaur, A., et al., The origin of Indian Star tortoises (Geochelone elegans) based on nuclear and mitochondrial DNA analysis: A story of rescue and repatriation. Conservation Genetics, 2005. 7(2): p. 231-240. [CrossRef]

- Kahler, J.S. and M.L. Gore, Beyond the cooking pot and pocket book: Factors influencing noncompliance with wildlife poaching rules. International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice, 2012. 36(2): p. 103-120. [CrossRef]

- Farine, D.R., Mapping illegal wildlife trade networks provides new opportunities for conservation actions. Anim Conserv, 2020. 23(2): p. 145-146.

- van Uhm, D., Illegal wildilfe trade to the EU and harms to the World, in Environmental Crime in Transnational Context: Global Issues in Green Enforcement and Criminology, T. Spapens, R. White, and W. Huismen, Editors. 2016, Routledge: Abingdon, Oxon.

- Poulsen, J.R., et al., Poaching empties critical Central African wilderness of forest elephants. Current Biology, 2017. 27: p. R123-R138. [CrossRef]

- Maisels, F., et al., Devastating decline of forest elephants in central Africa. PLoS One, 2013. 8(3): p. e59469. [CrossRef]

- Challender, D.W.S., et al., International trade and trafficking in pangolins, 1900–2019, in Biodiversity of the World: Conservation from Genes to Landscapes, Pangolins. 2020, Academic Press. p. 259-276.

- Emslie, R., Diceros bicornis ssp. longipes, in The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T39319A45814470. 2020.

- ‘t Sas-Rolfes, M., et al., Illegal wildlife trade: Scale, processes, and governance. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 2019. 44: p. 201-228.

- Thomson, J., Captive breeding of selected taxa in cambodia and viet nam: A reference manual for farm operators and cites authorities. 2008, TRAFFIC Southeast Asia, Greater Mekong Programme.

- Tensen, L., Under what circumstances can wildlife farming benefit species conservation? Global Ecology and Conservation, 2016. 6: p. 286-298.

- Lyons, J.A. and D.J.D. Natusch, Wildlife laundering through breeding farms: Illegal harvest, population declines and a means of regulating the trade of green pythons (Morelia viridis) from Indonesia. Biological Conservation, 2011. 144(12): p. 3073-3081. [CrossRef]

- Nijman, V. and C.R. Shepherd, Trade in non-native, CITES-listed, wildlife in Asia, as exemplifi ed by the trade in freshwater turtles and tortoises (Chelonidae) in Thailand. Contributions to Zoology, 2007. 76(3): p. 207-211.

- Moyle, B., Wildlife markets in the presence of laundering: a comment. Biodiversity and Conservation, 2017. 26(12): p. 2979-2985. [CrossRef]

- Nijman, V., An overview of international wildlife trade from Southeast Asia. Biodiversity and Conservation, 2009. 19(4): p. 1101-1114. [CrossRef]

- Cruz, R.M., et al., Wildlife Trade in Southern Palawan, Philippines. Banwa, 2007. 4(1): p. 12-26.

- Sy, E.Y., et al., Endangered by trade: seizure analysis of the critically endangered Philippine Forest Turtle Siebenrockiella leytensis from 2004–2018. Philippine Journal of Systematic Biology 2020.

- Schoppe, S., et al., Conservation Needs of the Critically Endangered Philippine Forest Turtle, Siebenrockiella leytensis, in Palawan, Philippines. Chelonian Conservation and Biology, 2010. 9(2): p. 145-153. [CrossRef]

- Chavez, L. Philippine forest turtles stand a 'good chance' after first wild release. Mongabay 2021 28 June 2021 28 June 2021]; Available from. https://news.mongabay.com/2021/06/philippine-forest-turtles-stand-a-good-chance-after-first-wild-release/.

- Griffiths, R.A. and L. Pavajeau, Captive breeding, reintroduction, and the conservation of amphibians. Conserv Biol, 2008. 22(4): p. 852-61.

- Asian Turtle Trade Working Group. Siebenrockiella leytensis. 2000 [cited 2020 12 October]; [CrossRef]

- Diesmos, A., et al., Siebenrockiella leytensis (Taylor 1920) – Palawan Forest Turtle, Philippine Forest Turtle, in Conservation Biology of Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises. 2012.

- Sy, E.Y., The Palawan forest turtle. TRAFFIC Bulletin, 2013. 25(1): p. 9.

- Schoppe, S. and C.R. Shepherd, The Palawan Forest Turtle: Under threat from international trade. TRAFFIC Bulletin, 2013. 25(1): p. 9-11.

- Schoppe, S., C.R. Shepherd, and C. Beastall, The Palawan Forest Turtle: The story of a rare turtle found, then feared lost, only to be rediscovered – now faces extinction. The Tortoise, 2013. 1(2): p. 108-117.

- CITES, Appendices I, II and III, CITES, Editor. 2021.

- Boussekey, M., An integrated approach to conservation of the Philippine or Red-vented cockatoo: Cacatua haematuropygia. International Zoo Yearbook, 2000. 37(1): p. 137-146. [CrossRef]

- Birdlife International. Cacatua haematuropygia. 2017 [cited 2020 13 October]; [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, E.C., et al., The birds of the Philippines: an annotated check-list. Vol. 12. 1991: British Ornithologists' Union Tring, UK.

- Schoppe, S., et al., Chapter 7 - Philippine pangolin Manis culionensis (de Elera, 1915), in Pangolins: Science, Society and Conservation, D.W.S. Challender, J.C. Nash, and C. Waterman, Editors. 2020, Elsevier Inc.

- Heinrich, S., et al., Where did all the pangolins go? International CITES trade in pangolin species. Global Ecology and Conservation, 2016. 8: p. 241-253. [CrossRef]

- Aceto, M., The use of ICP-MS in food traceability, in Advances in food traceability techniques and technologies. 2016, Elsevier. p. 137-164.

- Salvo, A., et al., Toxic and essential metals determination in commercial seafood: Paracentrotus lividus by ICP-MS. Natural product research, 2016. 30(6): p. 657-664. [CrossRef]

- Bonizzoni, L., et al., Comparison between XRF, TXRF, and PXRF analyses for provenance classification of archaeological bricks. X-Ray Spectrometry, 2013. 42(4): p. 262-267. [CrossRef]

- Natusch, D.J., et al., Serpent's source: Determining the source and geographic origin of traded python skins using isotopic and elemental markers. Biological Conservation, 2017. 209: p. 406-414.

- Croudace, I.W., Rindby, A., Rothwell, R.G., ITRAX: description and evaluation of a new multi-function X-ray core scanner, in New Techniques in Sediment Core Analysis, R.G. Rothwell, Editor. 2006, Geological Society, London: London. p. 51-63. [CrossRef]

- McGladdery, C., et al., Elemental assessment of vegetation via portable X-ray fluorescence (PXRF) spectrometry. J Environ Manage, 2018. 210: p. 210-225. [CrossRef]

- Weindorf, D.C., N. Bakr, and Y. Zhu, Advances in portable X-ray fluorescence (PXRF) for environmental, pedological, and agronomic applications, in Advances in agronomy. 2014, Elsevier. p. 1-45. [CrossRef]

- Hobson, K.A. and L.I. Wassenaar, Tracking animal migration with stable isotopes. Terrestrial Ecology Series, ed. K.A. Hobson and L.I. Wassenaar. 2008, USA: Elsevier Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- Brandis, K.J., et al., Using feathers to map continental-scale movements of waterbirds and wetland importance. Conservation Letters, 2021. e12798(e12798). [CrossRef]

- Hobson, K.A., Using stable isotopes to trace long-distance dispersal in birds and other taxa. Diversity and Distributions, 2005. 11: p. 157-164. [CrossRef]

- Hobson, K.A., Tracing origins and migration of wildlife using stable isotopes: a review. Oecologia, 1999. 120: p. 314-326. [CrossRef]

- Sung, Y.H., et al., Assessing the diet of the endangered Beale’s eyed turtle (Sacalia bealei) using faecal content and stable isotope analyses: Implications for conservation. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems, 2021. 31(10): p. 2804-2813. [CrossRef]

- Andersson, A.A., et al., Stable isotope analysis as a tool to detect illegal trade in critically endangered cockatoos. Animal Conservation, 2021. 10.1111/acv.12705(10.1111/acv.12705). [CrossRef]

- Brandis, K.J., et al., Novel detection of provenance in the illegal wildlife trade using elemental data. Scientific Reports, 2018. 8:15380. [CrossRef]

- Dempson, J. and M. Power, Use of stable isotopes to distinguish farmed from wild Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar. Ecology of Freshwater Fish, 2004. 13(3): p. 176-184. [CrossRef]

- Hammershøj, M., et al., Danish free-ranging mink populations consist mainly of farm animals: Evidence from microsatellite and stable isotope analyses. Journal for Nature Conservation, 2005. 13(4): p. 267-274. [CrossRef]

- Dittrich, C., U. Struck, and M.O. Rödel, Stable isotope analyses—A method to distinguish intensively farmed from wild frogs. Ecology and Evolution, 2017. 7(8): p. 2525-2534. [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, S., B. Streit, and D.E. Jacob, Assigning elephant ivory with stable isotopes, in Isotopic Landscapes in Bioarchaeology. 2016, Springer. p. 213-220. [CrossRef]

- Andersson, A., et al., Stable isotope analysis as a tool to detect illegal trade in critically endangered cockatoos. Animal Conservation, 2021. 24(6): p. 1021-1031. [CrossRef]

- DeNiro, M.J. and S. Epstein, Influence of diet on the distribution of carbon isotopes in animals. Geochimica et cosmochimica acta, 1978. 42(5): p. 495-506. [CrossRef]

- DeNiro, M.J. and S. Epstein, Influence of diet on the distribution of nitrogen isotopes in animals. Geochimica et cosmochimica acta, 1981. 45(3): p. 341-351. [CrossRef]

- Mumby, J.A., et al., Diet and trophic niche space and overlap of Lake Ontario salmonid species using stable isotopes and stomach contents. Journal of Great Lakes Research, 2018. 44(6): p. 1383-1392. [CrossRef]

- Hua, L., et al., Captive breeding of pangolins: current status, problems and future prospects. ZooKeys, 2015(507): p. 99.

- Paritte, J.M. and J.F. Kelly, Effect of cleaning regime on stable-isotope ratios of feathers in Japanese Quail (Coturnix japonica). The Auk, 2009. 126: p. 165-174. [CrossRef]

- Dunnington, D., xrftools: XRF Tools for R. R package version 0.0.1.9000, 2021.

- Chen, T., et al., Xgboost: extreme gradient boosting. R package version 1.3.2.1, 2021. 1(4): p. 1-4.

- Chen, T. and C. Guestrin. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. in Proceedings of the 22nd acm sigkdd international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining. 2016.

- Lenth, R., emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means. 2020.

- Gherase, M.R., J.E. Mader, and F. D.E.B., The radiation dose from a proposed measurement of arsenic and selenium in human skin. Physics in Medicine and Biology, 2010. 55: p. 5499-5514. [CrossRef]

- Specht, A.J., et al., Feasibility of a portable X-ray fluorescence device for bone lead measurements of condor bones. Sci Total Environ, 2018. 615: p. 398-403. [CrossRef]

- Irshad, N., et al., Distribution, abundance and diet of the Indian pangolin (Manis crassicaudata). Animal Biology, 2015. 65(1): p. 57-71. [CrossRef]

- Sopsop, L.B., Floral survey in the coastal forest of Rasa wildlife sanctuary, Narra, Palawan, Philippines. Journal of Environmental Science and Management, 2011. 14(1): p. 71-76.

- Diesmos, A.C., et al., Rediscovery of the Philippine forest turtle, Heosemys leytensis (Chelonia; Bataguridae), from Palawan Island, Philippines. Asiatic Herpetological Research, 2004. 10: p. 22-27.

- Pietersen, D.W., et al., Diet and prey selectivity of the specialist myrmecophage, Temminck's ground pangolin. Journal of Zoology, 2016. 298(3): p. 198-208. [CrossRef]

- Chesson, L.A., et al., Applying the principles of isotope analysis in plant and animal ecology to forensic science in the Americas. Oecologia, 2018. 187(4): p. 1077-1094. [CrossRef]

- Alacs, E.A., et al., DNA detective: a review of molecular approaches to wildlife forensics. Forensic Science, Medicine, and Pathology, 2010. 6: p. 180-194. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., et al., Molecular tracing of confiscated pangolin scales for conservation and illegal trade monitoring in Southeast Asia. Global Ecology and Conservation, 2015. 4: p. 414-422. [CrossRef]

- Mwale, M., et al., Forensic application of DNA barcoding for identification of illegally traded African pangolin scales. Genome, 2017. 60(3): p. 272-284. [CrossRef]

- van Uhm, D., Wildlife and laundering: Interaction between the under and upper world, in Green Crimes and Dirty Money, T. Spapens, et al., Editors. 2018, Routledge: London.

- Van Song, N., Wildlife Trading in Vietnam; Situation, Causes and Solutions. The Journal of Environment and Development, 2008. 17(2): p. 145-165.

- Thomas-Walters, L., et al., Taking a more nuanced look at behavior change for demand reduction in the illegal wildlife trade. Conservation Science and Practice, 2020. 2(9). [CrossRef]

- Kurland, J. and S.F. Pires, Assessing U.S. Wildlife Trafficking Patterns: How Criminology and Conservation Science Can Guide Strategies to Reduce the Illegal Wildlife Trade. Deviant Behavior, 2017. 38(4): p. 375-391. [CrossRef]

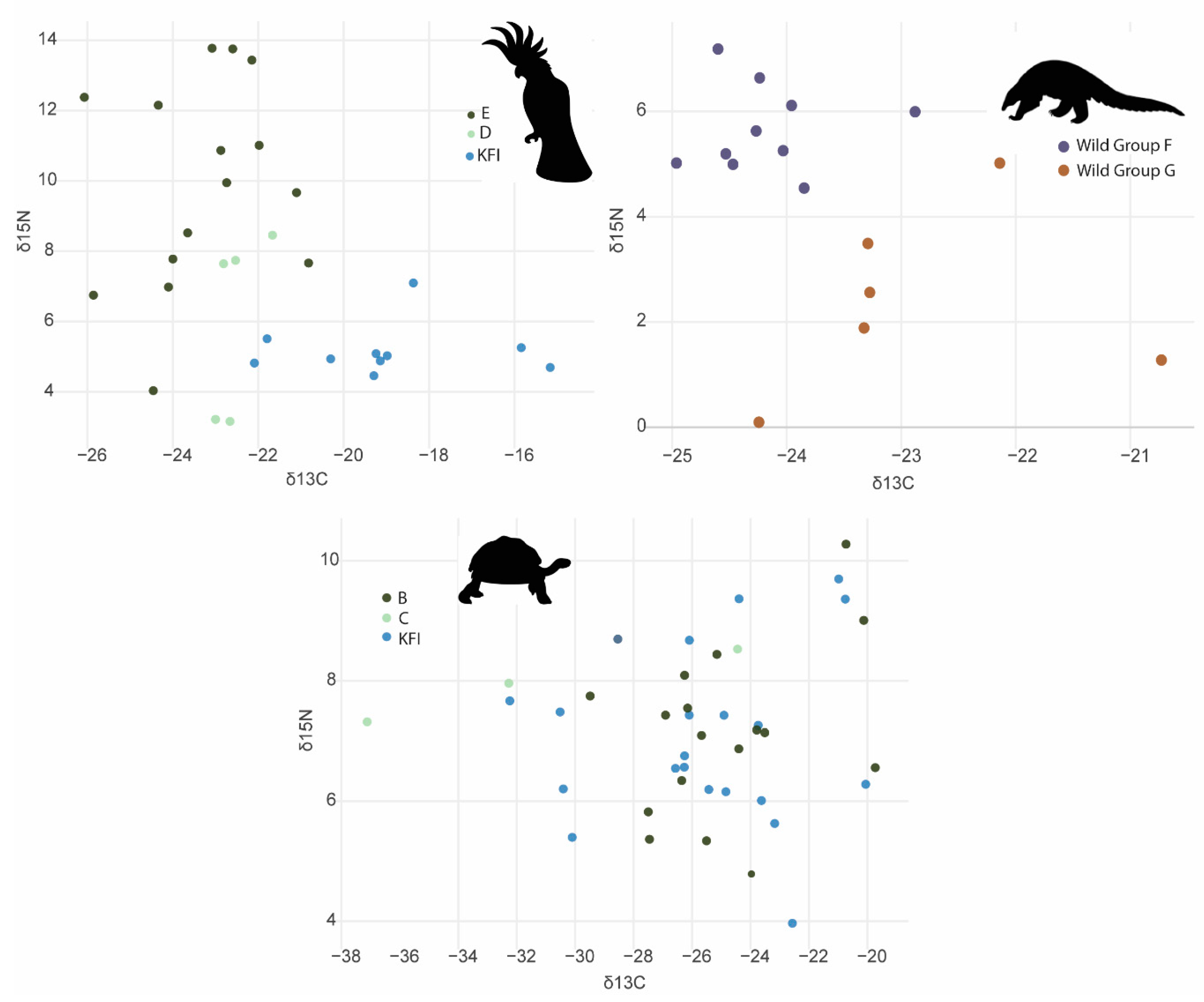

| Common Name | Species Name | Sample | Provenance | Site | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Palawan forest turtle | Siebenrockiella leytensis | Scute | Captive | KFI | 24 |

| Wild | B | 18 | |||

| C | 3 | ||||

| Philippine cockatoo | Cacatua haematuropygia | Feather | Captive | KFI | 20 |

| Wild | D | 24 | |||

| E | 21 | ||||

| Philippine pangolin | Manis culionensis | Claw | Wild | F | 10 |

| Scale | Wild | G | 6 | ||

| Species | Response variable | pXRF model % accuracy ±SD |

SIA model % accuracy ±SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Palawan forest turtle | Captive or wild | 88±12% | 66±16% |

| Geographic origin | 94±5% | 73±14% | |

| Philippine cockatoo | Captive or wild | 78±2% | 28±1% |

| Geographic origin | 62±9% | 27±2% | |

| Philippine pangolin | Group | 93±14% | 41±25% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).