1. Introduction

Nowadays, natural antioxidants derived from fruits and vegetables have gained interest as important food additives and nutraceutical supplements. The number of publications related to antioxidants and their applications has significantly increased in the last few years (Arias et al., 2022; Domínguez et al., 2020; Fraga et al., 2019; Lorenzo et al., 2018; Lyu et al., 2020). The purpose of using antioxidants in a food product is to delay oxidation reaction by inhibiting the formation of free radicals or by interrupting the propagation of the free radicals (Domínguez et al., 2019; Halliwell, 1995; Ribeiro et al., 2019). In general, many plant tissues develop antioxidant compounds under constant oxidative stress to protect themselves from free radicals, reactive oxygen species and prooxidants generated both exogenously (heat and light) and endogenously (H2O2 and transition metals). These antioxidant species are known as natural antioxidants. Some common examples of natural antioxidants include flavonoids, phenolic acids, carotenoids and vitamins (ascorbic acid, beta-carotene, tocopherols). They are efficient in scavenging free radicals, chelating pro-oxidant metal ions or are acting as reducing agents (Agati et al., 2007; Arias et al., 2022; Ozsoy et al., 2009).

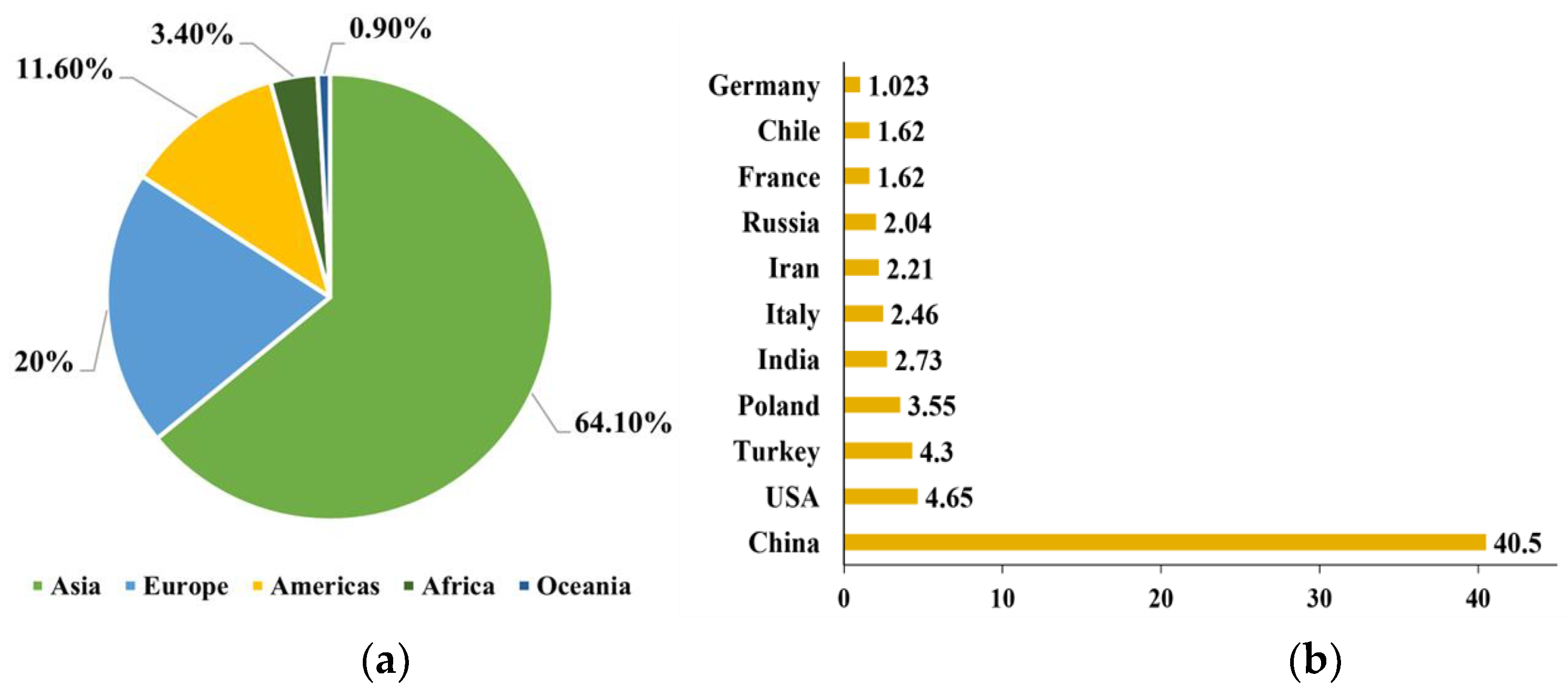

Apples (Malus domestica) are the most consumed fruits as they contain various bioactive compounds, including: pectins, dietary fibers, vitamins, oligosaccharides, triterpenic acids and phenolic compounds, such as flavonols, dihydrochalcones, anthocyanidins, hydroxycinnamic acids and hydroxybenzoic acids. Because of the higher content of these phenolic compounds (>20 mmol TE/kg), apples are well known for their high antioxidant properties (Ćetković et al., 2008; Cömert et al., 2020; Kalinowska et al., 2020; Raudone et al., 2017). According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, more than 86 million tons of apples were produced globally in 2020 (FAO, 2020). The global production of apples from 2012-2020 is reported in

Figure 1A. Based on these data, Asia stands as the largest producer (64.10 %), followed by Europe providing 20 % of total global production. America comes in the third rank by contributing with 11.6 % of apples in the last decade. The main apple producers in Europe are Poland, France, and Italy with more than 7.6 million tons of apples in 2020 as shown in

Figure 1B.

Generally, apples are consumed as fresh fruit. In 2019 more than 57 million tons of apple were consumed globally (Al Daccache et al., 2020). However, fresh apples are deteriorating and lost prior to consumption because of their short shelf life and presence of spoilage pathogens. The use of preservatives, manufacturing and cooking processes including pasteurization and addition of some additives can reduce the spoilage of fresh fruits.

Apples are also widely consumed in the form of processed food products. Typical examples of processed products from apples include juices, sauces, jams, apple pies, apple cider vinegar, wine, apple snacks (chips). Among all processed apple products, apple juice is the most produced product (65%)(Cruz et al., 2018; Lyu et al., 2020).

During the processing of apples, a high amount of by-products is produced. This by-product is called pomace and is constituted by a mixture of peel, core, seed, calyx, stem and soft tissue. It is mainly considered as a waste with processing companies facing problems discarding them in a sustainable way. Most of the time, apple pomace is used as fertilizer, for animal fodder or as a substrate for aerobic fermentation (Dugmore et al., 2017; Mirzaei-Aghsaghali & Maheri-Sis, 2008). However, the disposal of apple by-products as waste causes huge losses (Parfitt et al., 2010). Several studies have shown that apple by-products possess high biological activities due to the high content of phenolic compounds, vitamins, and carotenoids (de la Rosa et al., 2019). Therefore, apples and apple by-products are potential sources to extract natural antioxidants to be used in food, cosmetic and nutraceutical industries.

In this review, the antioxidant properties of apples and apple by-products are explained focusing on their phenolic content, extraction techniques, and potential applications in the food industry.

2. Antioxidant Compounds Present in Apple and Apple by-Products

Apples have gained special attention due to their chemical composition, especially for their antioxidant characteristics. Among four groups (vitamins, carotenoids, polyphenols and minerals) of non-enzymatic natural antioxidants, vitamins and phenolic compounds are the main constituents responsible for the antioxidant’s properties of apples (Daccha et al.2020; Skinner et al. 2023; Arias et al. 2022). In the following paragraph, the main group (with their subgroups) of antioxidant compounds are described.

2.1. Vitamins

Apples are a rich source of vitamins, especially vitamin C and E. Based on vitamin C content, apples are placed as the second highest ranked fruit after cranberries (Skinner et al. 2023). The concentration of vitamin C ranges from 2 to 35 mg/100 g based on the apple variety and it is found in two forms in apples such as ascorbic acid, and its oxidized form, dehydroascorbic acid (Daccha et al.2020; Campeanu et al. 2009). It has been reported that vitamin C has antioxidant properties with free radical–scavenging activity of EC50 = 0.35 (here EC50 is the concentration required to obtain a 50% antioxidant effect). On the other hand, vitamin E is mainly present in the apple seeds. As a result, apple pomace is a rich source of vitamin E, and it has been found that the concentration of vitamin E in apple pomace is 5.5 mg /100 g with a free radical–scavenging activity of EC50 = 0.30. Other vitamins found in apples are vitamin B12 and vitamin D, but they are present in trace amounts (Skinner et al. 2023).

2.2. Phenolic Compounds

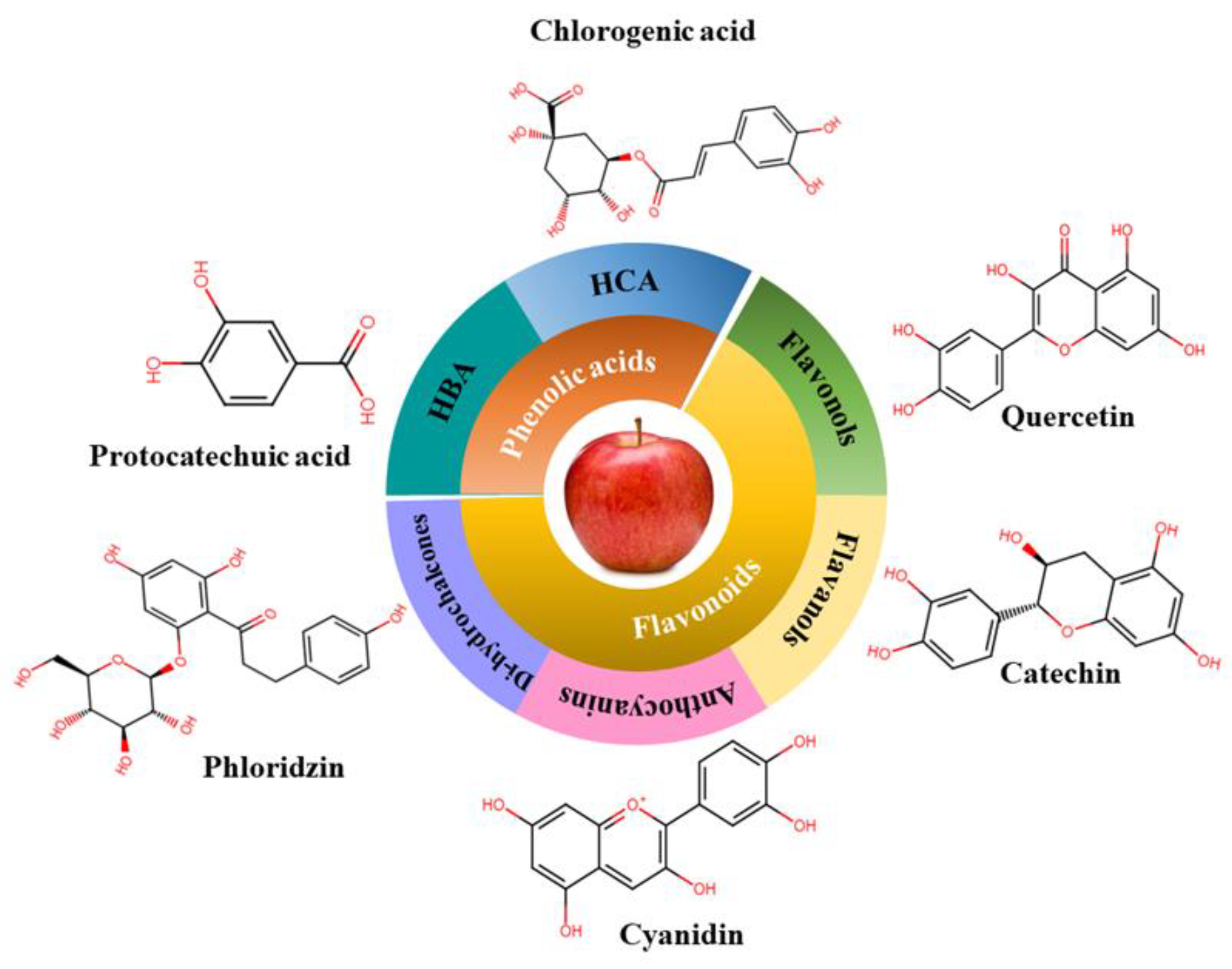

Phenolic compounds are one of the largest classes of plant secondary metabolites with biological functions in humans. They contain one or more aromatic rings in their molecular structures with one or more hydroxyl groups, which are responsible for exhibiting biological functions. To date, more than 60 phenolic compounds have been found in apples (da Silva et al., 2021; Kalinowska et al., 2020), which are mainly constituted by phenolic acids and flavonoids (

Figure 2). The mostly reported phenolic acids

2.2.1. Phenolic Acids

Phenolic acids are the major components belonging to non-flavonoids group of phenolic compounds. They are aromatic acids with a phenolic ring and an organic carboxylic acid (C6–C1 skeleton). They are also known as phenol carboxylic acids. According to their classification, they are mainly two types: hydroxybenzoic acids (C6-C1) and hydroxycinnamic acids (C6-C3) (Trigo et al., 2020).

Hydroxybenzoic acids are the derivatives of benzoic acid, found in fruits mostly in the conjugated form (esters or glycosides) but can also be present in the free form. Generally, they are bound to components of cell walls (such as cellulose or lignin or even forming protein complexes) that can be connected to sugars or organic acids (Barros et al., 2009). Examples of hydroxybenzoic acids present in apples include gallic acid, protocatechuic acid, vanillic acid, syringic acid (Bondonno et al., 2017; da Silva et al., 2021; Kalinowska et al., 2020; Kschonsek et al., 2018). On the other hand, hydroxycinnamic acids are rarely available in free form and are mainly present in conjugated forms (glycosylated or esters). The most reported hydroxycinnamic acids found in apples are quinic and caffeic acid, and estimated range was 4 to 18% of total phenolic compounds based on apple varieties. Furthermore, 5́-caffeoylquinic or chlorogenic acid, p-coumaroylquinic, and p-coumaric are also present in apple. They are mostly abundant in apple peel in comparison to apple flesh (Barros et al., 2009; Kschonsek et al., 2018; Nkuimi Wandjou et al., 2020).

2.2.2. Flavonoids

Apples are enriched with flavonoids. Among eight subclasses of flavonoid apples contain mainly four subclasses such as flavonols (71-90%), flavanols-3-ols (1-11%), anthocyanins (1-3%), chalcones/dihydrochalcones (2-6%) The most abundant flavonols found in apples are quercetin glycosides, (with quercetin 3-glycoside) whereas Catechins, epicatechins, and procyanidin B2 are the major compounds belonging to flavan-3-ols (they are mainly present in apples peel and pulp) (Bondonno et al., 2017; Hyson, 2011). The third subgroup ‘‘anthocyanins‘‘ include cyanidin 3-galactoside which is the most abundant in red apples peel as it is responsible for the red color. Examples of phenolic compounds belonging to dihydrochalcone are phloridzin and phloretin. These compounds are more abundant in apple seeds and apple pomace and mainly found in conjugated forms (linked to the fruit sugar content, such as glucose and xyloglucan) (da Silva et al., 2020; Jakobek & Barron, 2016).

3. Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Apple and Apple by-Products

The yield of total phenolic content and antioxidant properties of phenolic compounds from apple and apple by-products is greatly influenced by the extraction techniques and conditions (Casazza et al., 2020; Górnaś et al., 2015). The main purpose of extraction is to recover all compounds present in apple, without any chemical modifications (Bekele et al., 2014). Several studies have been published demonstrating different extraction techniques and conditions to recover phenolic compounds from apple, and apple by-products. In general, the extraction of phenolic compounds for apple can be achieved by using conventional or innovative extraction techniques (López-fernández et al., 2020; Perussello et al., 2017).

3.1. Conventional Extraction

The widely reported conventional methods for the extraction of phenolic compounds from apples are maceration, Soxhlet extraction, and hydro-distillation. Conventional Soxhlet extraction is mainly used for the recovery of volatile compounds from apples specially aroma compounds (as the recovered extracts provide the aroma closest to the fresh fruit) whereas, vacuum hydro-distillation is used to extract volatile and polar components from plant matrices (Mehinagic et al., 2003; Rabetafika et al., 2014). Indeed, Soxhlet extraction is found to be effective to extract phenolic compounds such as phlorizin, epicatechin, quercetin, and phloretin from apple pomace with a yield of (TPC) 4.13 mg/g (Ferrentino et al., 2018). The right choice of the solvent is a crucial factor for these extraction methods. Extraction solvent should be selected based on polarity of phenolic compounds. For phenolic compounds, ethanol, acetone, methanol or acidified methanol, water or combination of water with methanol/ethanol were the most recommended solvents as mentioned by several authors. Water is a suitable solvent to extract phenolic compounds from apple pomace like hydroxycinnamic acids and flavonoids (dihydrochalcones, flavanols) (Hernández-Carranza et al., 2016). However, it is not the right choice for some phenolic compounds like quercetin glycosides (Reis et al., 2012). On the other hand, only pure organic solvents are not sufficient to extract polar phenolic compounds. For this purpose, it is important to use more polar solvents in a combination. For example, methanol is an appropriate solvent to extract chlorogenic acid and phlorizin and the optimized conditions for extraction using methanol were 84.5% methanol for 15 min at 28 °C. However, acetone (65%) shows high selectivity for the recovery of most polyphenols with high antioxidant properties by performing a maceration for 20 min at 10 °C (Alberti et al., 2014). Sometimes, multiple-step extraction is required to extract 100% of phenolic compounds. In multi-step extraction different types of solvents are used. According to Reis et al. (2012), three steps extraction was able to recover the total phenolic content from apple pomace. The first solvent was water which yielded 67% and the 2nd and 3rd steps were performed using methanol and acetone to obtain a yield of 17% and 16 %, respectively (Reis et al., 2012).

Fromm et al. (2013) used a magnetic stirrer to optimize the extraction based on time and temperature from apple seeds. For this purpose, the authors conducted the experiments at different temperatures (0–42 ° C) and extraction time (60–1440 min) using aqueous acetone (60-70% v/v) and reported the optimum value was at 25 °C for 60 min. Moreover, other authors have also demonstrated that the optimum temperature was 60 ° C to extract phenolic compounds from apple pomace but reduced extraction time was observed (from 60 min to 30 min) while using aqueous methanol (80%, v/v) and ethanol (50%, v/v) (da Silva et al., 2020; Fromm et al., 2013).

However, the major drawbacks of conventional extraction techniques are the lack of the temperature control, exposure to light, longer extraction time and the large quantity of organic solvents required, which may reduce the extraction yields, and the extract concentration of target compounds. These drawbacks lead to seek innovative techniques that are closer to the concept of “green” technologies (Azmir et al., 2013; Putnik et al., 2018). In fact, these alternative technologies are aimed at providing safe compounds by minimizing or eliminating the drawbacks of the conventional techniques (Soquetta et al., 2018).

3.2. Innovative Extraction

The most innovative techniques are ultrasound assisted extraction (UAE), microwave-assisted extraction (MAE), supercritical fluid extraction (SFE), pressurized liquid extraction, pulsed electric fields (PEF) (Alirezalu et al., 2020). Phenolic compounds of apple can easily be extracted by microwave-assisted extraction (MAE). In MAE microwave energy is used to heat solvents in contact with a sample to allow the analytes partitioning from the sample matrix into the solvent. In general, ethanol is used as a solvent in this method with specific ratio that is 22.9:1 (solvent: raw material). MAE showed higher efficiency at a shorter time for the extraction of phenolic compounds from apple pomace in comparison to conventional methods (Soxhlet and maceration) (Bai et al., 2010).

Ultrasound assisted extraction (UAE) is regarded as sustainable technology as it needs a moderate investment of solvent and energy. Furthermore, it is very cheap, easy to operate, and reproducible due to its capability to work under atmospheric pressure and at an ambient temperature. UAE technique shows potential to increase the yield of polyphenols thanks to the enhancement of the diffusion of a solvent through the cell walls, and thus increases the release of the cell components (nutritional components and phenolic compounds) extraction (Khawli et al., 2019; Medina-Torres et al., 2017). It has been reported that, the yield of phenolic compounds from apple pomace using UAE (even with the same extraction conditions) is 20 % and 30% higher than conventional method (Pingret et al., 2012; Virot et al., 2010). Recently, UAE combined with natural deep eutectic solvents (NADES) has developed. It has been reported that, UAE and NADES with optimized parameters showed better efficiency in terms of TPC, TFC and radical scavenging activity in comparison to the conventional solvent such as water, ethanol and 30% hydro-ethanolic solution. The best NADES was found choline chloride in combination with glycerol (1:2) and choline chloride with Lactic acid (1:3). For both two cases values for TPC, TFC and radical scavenging activity by DPPH were higher in comparison to the conventional solvents (Rashid et al., 2022). The yield for apple pomace polyphenol is also higher for UAE method in comparison to MAE method and the value of yields were 10.2 mg/g and 3.8 mg/g, respectively (He et al., 2015). The optimal conditions for the extraction process of polyphenols from apple pomace were reported by Vigor with an ultrasonic power of 0.142 W/g, a temperature of 40.1 °C and sonication time of 45 min whereas the best yield was reported by Pingret et al. (2012) with an ultrasound intensity of 0.76 W/cm2 at 40 °C for 40 min (Pingret et al., 2012; Virot et al., 2010).

Supercritical fluid extraction is another example of green and efficient technology. This technology is mainly used to extract essential oils from plant-based by-products. At present, several studies have been conducted to recover high-added value compounds using this technology. Carbon dioxide is the most used fluid in supercritical fluid extraction as it possesses low toxicity, low critical temperature (31.1° C) and high safety profile with or without ethanol (5%) as co-solvent. The use of organic co-solvents (e.g., ethanol, methanol, acetone) is required to increase the solubility of polar polyphenols during extraction as carbon dioxide is a non-polar solvent. By changing the extraction parameters (pressure, temperature, ethanol concentration, extraction time) it is also possible to extract specific phenolic compounds precisely from a complex mixture of natural compounds. It has been demonstrated that, extraction using SFE to extract phenolic compounds from freeze dried apple pomace at 30 MPa and 45 °C for 2 h with ethanol as co solvent exhibited a higher antioxidant activity (5.63 ± 0.10 mg TEA/g of extract) in comparison to conventional extraction technologies such as Soxhlet with ethanol (2.05 ± 0.21mg TEA/g of extract) and boiling water maceration (1.14 ± 0.01mg TEA/g of extract) (Barba et al., 2016; Ferrentino et al., 2018).

Finally, although UAE showed promising results for the extraction of polyphenols from apple and apple by-products, further research studies should be carried out to demonstrate the optimal process conditions for each extraction technique in order to recover phenolic compounds with high antioxidant activity using kinetic approaches.

4. Applications of Apple Phenolic Compounds in Food Products

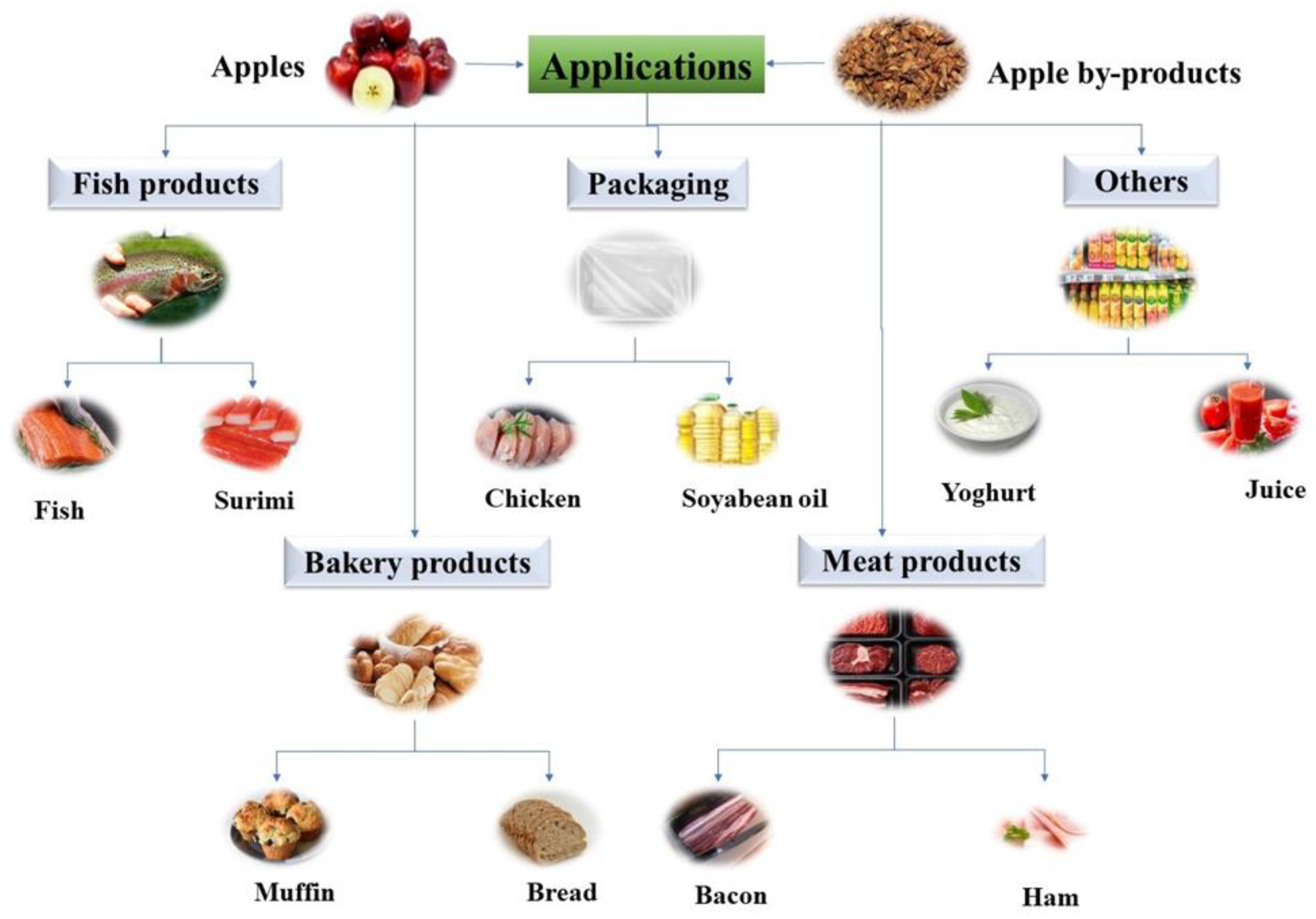

Nowadays, food products fortification using apple or apple by-products has gained more attention as they are a good source of dietary fibers and bioactive compounds. This product, rich in natural antioxidants, could play an important role in replacing the synthetic ones (Filipčev et al., 2010; Li et al., 2020). In the following sections, food products formulated with the incorporation of apple or by-products are described as shown in

Figure 3.

4.1. Bread and Bakery Products

There has been a growing interest in utilizing apple and apple by-products powder in bread and bakery products (as baked goods are suitable foods to be fortified). The addition of dried apple powder ( 5 and 10%) increased the antioxidant capacity of wheat bread up to 38.5% and 61.9% when compared with control bread. Overall, the sensory properties were acceptable regardless of the control samples (Filipčev et al., 2010). Furthermore, recent studies have demonstrated that the total polyphenol content and antioxidant potential of wheat bread increased while formulated with defatted 5% and 20% apple seed powder of different varieties (Golden Delicious, Idared, and Šumatovka). The results showed that the total polyphenol content was 1.7 and 2.9 times higher with 1.1 and 2.1 times higher antioxidant capacity in comparison to the control bread (Purić et al., 2020). In addition, the antioxidant properties of other bakery products such as cakes, buns, cookies, and muffins enriched with apple pomace were investigated by several researchers. For instance, increased antioxidant properties with improved sensory attributes (fruity flavor) were observed when muffins were prepared with 20% of apple pomace (Sudha et al., 2007, 2016). Similarly, another study reported that muffins blended with up to 32% of apple peel powder (Idared and Northern Spy) showed higher total phenolic content, total antioxidant capacity, dietary fiber content and water holding capacity (Rupasinghe et al., 2008). Several published works have investigated the effect of total polyphenol content and total dietary fiber content in cookies enriched with apple pomace (5%, 10%, 15%, 20%, and 25%). The best result was obtained when the cookies were prepared by adding apple pomace powder (10%) with acceptable sensory attributes and nutritional composition. (Jung et al., 2015; Usman et al., 2020). Other important applications of apple pomace powder involved the preparation of a gluten-free bread with satisfactory sensory quality and biscuits with a low glycemic index. In detail, biscuit products blended with 10% and 20% of dried apple pomace were able to decrease the glycemic index. It has been found that glycemic index values were reduced with the increasing concentration of apple pomace and the values were 65.7 and 60.8 for 10% and 20%, respectively whereas the value was 70.4 for the control sample. Moreover, the overall results for sensory analysis were quite acceptable except for the color as it became darker in comparison to the control one (Alongi et al., 2019; Rocha Parra et al., 2015). Finally, the addition of apple and apple pomace powder in bread and bakery products has a positive impact in terms of total phenolic content, total antioxidant capacity, and acceptable sensory properties (except color). Generally, most of the studies reported that bakery products blended with apple pomace powder became darker due to the probability of nonenzymatic browning of apple carbohydrates that could undergo caramelization or Maillard reaction during heating treatments (Alongi et al., 2019; Jung et al., 2015).

4.2. Fish and Fish Products

Natural antioxidants derived from apples have gained much interest for their antioxidative characteristics. Thus, they become an important factor in the preservation of food products (containing long-chain unsaturated fatty acids) to prevent lipid oxidation. For example, Rupasinghe et al. (2010) applied two different apple peel extracts to protect fish products from the oxidation. For this purpose, an initial apple peel extract was prepared using 95% ethanol (including primary and secondary metabolites) whereas the second extract was collected from the first after removing two metabolites (sugars and organic acids). The total phenolic content of the second extract was higher than the first one with values equal to 42,025.5 μg/ml and 399.1 μg/ml, respectively. Similarly, the second extract was more potent compared to the first extract in terms of antioxidant capacity (while performing FRAP, ORAC, and DPPH• assays). The antioxidant capacity values for the second extracts were 317 (FRAP assay) and 134 (ORAC assay) times higher than the first extracts. In addition, lipid oxidation in fish oil was investigated by exposing it to major precursors to initiate oxidation (2,2′-Azobis(2-amidinopropane) dihydrochloride (AAPH), heat and UV light). The reason for using such types of precursors is to facilitate the irreversible and inevitable oxidative degradation of the double bounds located within unsaturated fatty acids and produce unstable oxidation products. In this condition, the inhibition capacity for lipid oxidation of the second extract was comparable with commercial synthetic antioxidants such as butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT). The induction time of BHT (24.5 h with 200 μg/ml) and the second apple extract (25.2 h with 400 μg/ml) resulted higher compared to the induction time (13.6 h) of the first extract (20,000 μg/ml). The study proved that phenolic compounds recovered from apples can act as natural antioxidants depending on their concentration (Domínguez et al., 2019; Rupasinghe et al., 2010). Furthermore, the effect of apple peel extract on lipid and protein oxidation of rainbow trout samples were evaluated during their storage (4 days at 4° C) by several researchers. For this purpose, trout fish fillets were minced using a meat blender equipped with a 3-mm plate (Pars Khazar Co., Iran). Then, 3 replicates were prepared (80 g of each) for mixing 5 different concentrations (10, 20, 30, 50, and 100 mg of gallic acid equivalent/kg mince) of apple peel extracts. All samples (control and treated) were kept at 4° C for 96 h and analyzed at a time interval of 0, 24, 48 and 96 h, respectively.

The formation of secondary (thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances; TBARS) lipid oxidation products were lower in treated trout samples (1.04 mg malonaldehyde (MDA) equivalent/kg) compared to control samples (3.07 mg malonaldehyde (MDA) equivalent/kg) after 4 days of storage. Similar behavior, i,e lower levels of protein oxidation, were also observed in samples treated with peel extracts (Bitalebi et al., 2019; Hellwig, 2019). Finally, for the fish product (surimi prepared from grass carp fish) the effect of Qinguan young apple polyphenols (especially chlorogenic acid, epicatechin and phlorizin) on lipid oxidation was tested during storage for 7 days at 4° C. For this purpose, 0.05% and 0.10% apple polyphenols extracts were added to the surimi samples. The results showed that the formation of lipid oxidation products were lower in comparison to control samples (without antioxidants). The TBARS value was higher (1.3 mg MDA/kg) in the control sample whereas the sample enriched with apple polyphenols extract showed a lower value (0.3 mg MDA/kg) (Sun et al., 2017).

4.3. Meat and Meat Products

Apple polyphenols obtained from apple pomace and peel could play an important role in inhibiting oxidation (lipid and protein) and retaining the quality of meat and meat products. For instance, Sun et al. (2010) evaluated the effect of apple polyphenols concentration ranging from 300 to 1000 ppm on ham products formulated from pork or beef meat. The samples were analyzed in terms of sensory analysis, lipid and protein oxidation during a refrigerated storage period of 35 days. The incorporation of apple peel polyphenols (500 ppm) significantly retained the color of stored pork hams. However, the addition was ineffective for beef hams. All treated samples did not report lipid oxidation while no significant differences were observed for protein oxidation (Sun et al., 2010). Another study was performed to detect total phenolic content and free radical scavenging activity (RSA) on chicken patty and beef jerky prepared by adding 10 % and 20 % of apple pomace. The results showed that beef jerkies with 20% apple pomace had higher RSA in comparison to control sample (Jung et al., 2015). Similarly, chicken sausage blended with 3%, 4% and 9% of apple pomace exhibited an increase in antioxidant activity with higher fiber content and nice color (Yadav et al., 2016).

The lipid and protein oxidation were also analyzed on industrialized meat product (dry-fried bacon) to observe the effect of apple polyphenol (AP). The TBARS value was lower in bacon treated with AP (300 mg/ kg) and the value was 0.59 mg MDA/kg whereas the control sample presented a value of 1.03 mg MDA/kg. This result indicated that the AP treated bacon sample delayed the lipid oxidation. Similarly, the addition of same amount of AP exhibited the strongest inhibitory effect against protein oxidation among all studied plant polyphenols (tea polyphenol and cinnamon polyphenol) that exhibited less effect on the color of the bacon sample. The protein carbonyl value was 2.30 nmol/mg protein (as protein carbonyl content is a useful indicator for the determination of protein oxidation in meat and meat products) whereas the control sample showed high carbonyls content value of 3.21 nmol/mg protein (Deng et al., 2022). Furthermore, the effect of apple pomace was evaluated on boneless mutton meat (both cooked and uncooked) against lipid oxidation. For this purpose, mutton meat with 10% fat was added with 1%, 3% and 5% apple pomace powder (APP), respectively to prepare goshtaba. The highest inhibitory effect was found for meat samples (both cooked and uncooked) prepared with 5 % APP (Rather et al., 2015).

4.4. Functional Packaging Materials

The demand for functional packaging materials has gained increasing attention as they are formulated either by adding antioxidants or coating on food packaging materials. The purpose of using functional packaging materials is to reduce food oxidation (main cause of food spoilage) (Gaikwad et al., 2016). In addition, several research studies are performed to develop biodegradable packaging materials incorporated with natural antioxidants for food applications to replace synthetic and non-biodegradable materials (Lan et al., 2021; Lin et al., 2022; Sun et al., 2018). Functional packaging materials made from polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) matrix incorporated with apple pomace powder (from 1 up to 10% w/w) showed higher antioxidant activity when used as packaging material by preserving soybean oil stored at 23 or 60° C. The antioxidant activity was directly proportional to the concentration of apple powder added to PVA. In addition, lipid oxidation of packaging was also evaluated for the same sample in terms of TBARS value. The oxidative index reduced with increasing temperature (23-60 °C). In fact, no differences were observed in TBARS value when samples were stored at 23 °C whereas it was lower at 60 °C (Gaikwad et al., 2016). Another example of functional packaging material includes chitosan film formulated with thinned young apple polyphenols (YAP). It has been reported that chitosan (biopolymer) film with (1 % w/v) YAP exhibited 3 times higher antioxidant activity compared to control film. The reason for the enhanced antioxidant activity was due to presence of large amount of polyphenols (chlorogenic acid and phlorizin as major phenolic compounds) in thinned young apple (Sun et al., 2017). Chitosan film incorporated YAP was applied on freshwater fish (grass carp) fillets to evaluate the effect of lipid and protein oxidation during cold storage. The wrapping with chitosan-YAP film of fish fillet allowed the protection of the product from both lipid and protein oxidation. The results showed that the formation of peroxides was lower in wrapped fillet in comparison to control one and thus retarded the lipid oxidation process. Similar results were observed in wrapped fillet for protein oxidation as the formation of total volatile basic nitrogen was decreased. The inhibitory activity of the film against lipid and protein oxidation was considered due to the antioxidant properties of thinned young apple (Sun et al., 2018). The effect of apple by-products (peel and pomace) polyphenols incorporated into chitosan (CS) film were also investigated in several studies. For CS based apple peel polyphenols (1 % w/v) film, enhanced antioxidant and antimicrobial activities were observed in comparison to the control film. The radical scavenging activity were nearly increased by 4 folds for both DPPH and ABTS assays and the antimicrobial activity against Bacillus cereus, Escherichia coli, Salmonella typhimurium and Staphylococcus aureus was increased by more than 2 folds (Riaz et al., 2018). On the other hand, the effect of Fuji apple polyphenol as a coating material (apple peel powder and carboxymethylcellulose) was also evaluated in patties prepared from beef during 10 days of storage in the refrigerator. The use of the active coating was able to protect uncooked beef patties from lipid oxidation and microbial growth without changing the sensory attributes (Shin et al., 2017).

Furthermore, CS based with 5%w/v red apple pomace extract (APE) exhibited the strongest antioxidant properties while CS based film with nanosized TiO2 and APE showed the highest antimicrobial activity among all studied films (CS film; CS-APE film; CS-TiO2 film; CS-TiO2- APE film). The radical scavenging ability of DPPH assay was increased by nearly 4 times and the antimicrobial activity against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus was increased by 7 and 8 times, respectively (Lan et al., 2021).

Finally, the antioxidant activity and lipid oxidation of edible films prepared with cassava starch, sodium carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) and apple polyphenol (AP) were evaluated. Results obtained from DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging activity assays showed increased antioxidant activity in comparison to control film and a dose dependent response was observed (based on the concentration of AP added in the films) for antioxidant activity. The results of lipid oxidation assay for chicken meat during storage at 4 °C for 7 days exhibited lower value for TBARS. the value was 0.092 mg MDA/kg (which was much lower than the control film with a value of 0.178 mg MDA/kg). The optimum concentration of AP was 70 mg/mL for this edible film, based on its oxidation inhibition capacity as well as other physical and mechanical properties (Lin et al., 2022). It can be concluded that the addition of apple polyphenols in packaging materials (either natural or synthetic) showed better inhibitory effect against lipid and protein oxidation and better antioxidant performance. Therefore, packaging material incorporated with apple polyphenols could be a potential alternative to ensure food safety and shelf-life extension for highly perishable food items (fish, meat, fruit, and vegetables).

4.5. Other Products

The antioxidant properties of other food products such as noodles, vegetable juices, and yoghurt were also investigated when apple pomace was added. In detail, noodles were formulated with 10 % and 25 % apple pomace. The incorporation of 10 % apple pomace powder in samples had positive effect on nutritional properties in terms of dietary fiber content, protein content, and antioxidant activity. Also, the sensory attributes (color, flavor, taste, and texture) were improved without affecting the cooking or texture properties of noodles. On the other side, noodles produced with 25 % of apple pomace in the wheat flour were significantly affected in terms of color, flavor, taste, and texture (Yadav and Gupta, 2015).

Similarly, the study on carrot and tomato juices revealed that both samples enriched with apple peel extracts showed an increase in the antioxidant capacity and the increased value was equal to 160 mg gallic acid equivalent (GAE) /L. For this purpose, oxidative stability of juices enriched with apple peel extracts and commercial antioxidants (BHT/BHA) was evaluated. The samples treated with apple peel extracts (20 mg/L of GAE) and commercial antioxidants (25 μM) were stable during their storage while the control samples reported high lipid hydroperoxides with values above the threshold (Massini et al., 2016).

Another important potential application of apple extracts is the fortification of yoghurt. The use of apple pomace extracts in yogurt formulation provided a final product with improved fiber content and antioxidant properties compared to the plain yogurt. For instance, yoghurt fortified with apple pomace extracts (3.3%) showed an enhancement of the total phenolic content and antioxidant activity. The values were 2 times and 3 times higher respectively in comparison to the control (Fernandes et al., 2019). On the other hand, the effect of apple peel extract (APE) on probiotic yoghurt was also investigated. In this regard, probiotic yoghurt was made by adding different concentrations of APE (1%, 2%, 3%, 4% and 5%, respectively). The results exhibited higher total phenolic content and antioxidant capacity in fortified probiotic yoghurts compared to control sample. The enhancement of total phenolic content and antioxidant capacity was correlated to the quantity of APPE added to probiotic yoghurts. Therefore, probiotic yoghurt formulated with 5% of APE showed the highest total phenolic content and inhibition of the oxidation (expressed in percentage) among all with values equal to 9.52 g GAE/100 g of DW and 47%, respectively during 21 days of refrigerated storage (Ahmad et al., 2020).

5. Conclusions

Apples and apple by-products are rich sources of phenolic compounds. Therefore, the extraction of phenolic compounds from apples and their application into processed foods as natural food additives could play an important role in replacing synthetic antioxidants and conventional packaging materials. The high phenolic content of apple and apple by-products (powder and extracts) facilitates the development of the final products with increased antioxidant properties without affecting the sensory attributes. In addition, the proper utilization of apples and apple by-products minimizes the detrimental effect on the environment and contributes to a positive effect on the economy. However, when moving to the application, the main drawback found for fortified bakery products is the undesirable change in color (darker and brownish). On the other hand, the alteration of color in meat products positively influences the sensory panelists. This underlines the need to perform more studies to investigate the effect of the addition of such ingredient to foods.

Moreover, more investigations are also required regarding safety issues of apple derived products, especially for apple by-products as they contain measurable levels of pesticide residues. They can be effectively removed by applying some techniques such as ozonation and washing (with sodium bicarbonate) prior to processing. Other concerns regarding safety issues of apple derived products include the release of cyanide glycosides from apple seeds and the accumulation of patulin due to fungal growth. Its maximum level has been established by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) equal to 50 μg/kg (of product) for adults and 10 μg/kg for infants and young children.

These conclusions clearly emphasize the need to take into account several issues for future application dealing with apples and apples derived by-products.

Author Contributions

conceptualization, U.A. and K.M.; writing—original draft preparation, U.A.; writing—review and editing, U.A. and G.F.; supervision, M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Open Access Publishing Fund of the Free University of Bozen-Bolzano.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Agati, G.; Matteini, P.; Goti, A.; Tattini, M. Chloroplast-located flavonoids can scavenge singlet oxygen. New Phytol. 2007, 174, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Daccache, M.; Koubaa, M.; Maroun, R.G.; Salameh, D.; Louka, N.; Vorobiev, E. Impact of the Physicochemical Composition and Microbial Diversity in Apple Juice Fermentation Process: A Review. Molecules 2020, 25, 3698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, A.; Zielinski, A.A.F.; Zardo, D.M.; Demiate, I.M.; Nogueira, A.; Mafra, L.I. Optimisation of the extraction of phenolic compounds from apples using response surface methodology. Food Chem. 2014, 149, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Khalique, A.; Shahid, M.Q.; Rashid, A.A.; Faiz, F.; Ikram, M.A.; Ahmed, S.; Imran, M.; Khan, M.A.; Nadeem, M.; et al. Studying the Influence of Apple Peel Polyphenol Extract Fortification on the Characteristics of Probiotic Yoghurt. Plants 2020, 9, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alirezalu, K.; Pateiro, M.; Yaghoubi, M.; Alirezalu, A.; Peighambardoust, S.H.; Lorenzo, J.M. Phytochemical constituents, advanced extraction technologies and techno-functional properties of selected Mediterranean plants for use in meat products. A comprehensive review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 100, 292–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alongi, M.; Melchior, S.; Anese, M. Reducing the glycemic index of short dough biscuits by using apple pomace as a functional ingredient. LWT 2018, 100, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, A.; Feijoo, G.; Moreira, M.T. Exploring the potential of antioxidants from fruits and vegetables and strategies for their recovery. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2022, 77, 102974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmir, J.; Zaidul, I.S.M.; Rahman, M.M.; Sharif, K.M.; Mohamed, A.; Sahena, F.; Jahurul, M.H.A.; Ghafoor, K.; Norulaini, N.A.N.; Omar, A.K.M. Techniques for extraction of bioactive compounds from plant materials: A review. J. Food Eng. 2013, 117, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Yue, T.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, H. Optimization of microwave-assisted extraction of polyphenols from apple pomace using response surface methodology and HPLC analysis. J. Sep. Sci. 2010, 33, 3751–3758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barba, F.J.; Zhu, Z.; Koubaa, M.; Sant’Ana, A.S.; Orlien, V. Green alternative methods for the extraction of antioxidant bioactive compounds from winery wastes and by-products: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 49, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, L.; Dueñas, M.; Ferreira, I.C.; Baptista, P.; Santos-Buelga, C. Phenolic acids determination by HPLC–DAD–ESI/MS in sixteen different Portuguese wild mushrooms species. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2009, 47, 1076–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekele, E.A.; Annaratone, C.E.; Hertog, M.L.; Nicolai, B.M.; Geeraerd, A.H. Multi-response optimization of the extraction and derivatization protocol of selected polar metabolites from apple fruit tissue for GC–MS analysis. Anal. Chim. Acta 2014, 824, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitalebi, S.; Nikoo, M.; Rahmanifarah, K.; Noori, F.; Gavlighi, H.A. Effect of apple peel extract as natural antioxidant on lipid and protein oxidation of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) mince. Int. Aquat. Res. 2019, 11, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondonno, N.P.; Bondonno, C.P.; Ward, N.C.; Hodgson, J.M.; Croft, K.D. The cardiovascular health benefits of apples: Whole fruit vs. isolated compounds. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 69, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campeanu, G. , Neata, G., & Darjanschi, G. (2009). Chemical Composition of the Fruits of Several Apple Cultivars Growth as Biological Crop. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca, 37, 161–164.

- Casazza, A.A.; Pettinato, M.; Perego, P. Polyphenols from apple skins: A study on microwave-assisted extraction optimization and exhausted solid characterization. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2020, 240, 116640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćetković, G.; Čanadanović-Brunet, J.; Djilas, S.; Savatović, S.; Mandić, A.; Tumbas, V. Assessment of polyphenolic content and in vitro antiradical characteristics of apple pomace. Food Chem. 2008, 109, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cömert, E.D.; Mogol, B.A.; Gökmen, V. Relationship between color and antioxidant capacity of fruits and vegetables. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2019, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, M.G.; Bastos, R.; Pinto, M.; Ferreira, J.M.; Santos, J.F.; Wessel, D.F.; Coelho, E.; Coimbra, M.A. Waste mitigation: From an effluent of apple juice concentrate industry to a valuable ingredient for food and feed applications. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 193, 652–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, L.C.; Souza, M.C.; Sumere, B.R.; Silva, L.G.; da Cunha, D.T.; Barbero, G.F.; Bezerra, R.M.; Rostagno, M.A. Simultaneous extraction and separation of bioactive compounds from apple pomace using pressurized liquids coupled on-line with solid-phase extraction. Food Chem. 2020, 318, 126450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, L.C.; Viganó, J.; Mesquita, L.M.d.S.; Dias, A.L.B.; De Souza, M.C.; Sanches, V.L.; Chaves, J.O.; Pizani, R.S.; Contieri, L.S.; Rostagno, M.A. Recent advances and trends in extraction techniques to recover polyphenols compounds from apple by-products. Food Chem. X 2021, 12, 100133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Rosa, L.A.; Moreno-Escamilla, J.O.; Rodrigo-García, J.; Alvarez-Parrilla, E. Phenolic compounds. In Postharvest Physiology and Biochemistry of Fruits and Vegetables; Yahia, E., Carrillo-Lopez, A., Eds.; Cambridge, UK, 2018; pp. 253–271 ISBN 9780128132784.

- Deng, S.; Shi, S.; Xia, X. Effect of plant polyphenols on the physicochemical properties, residual nitrites, and N-nitrosamine formation in dry-fried bacon. Meat Sci. 2022, 191, 108872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, R.; Gullón, P.; Pateiro, M.; Munekata, P.E.S.; Zhang, W.; Lorenzo, J.M. Tomato as Potential Source of Natural Additives for Meat Industry. A Review. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, R.; Pateiro, M.; Gagaoua, M.; Barba, F.J.; Zhang, W.; Lorenzo, J.M. A Comprehensive Review on Lipid Oxidation in Meat and Meat Products. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 429–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugmore, T.I.J.; Clark, J.H.; Bustamante, J.; Houghton, J.A.; Matharu, A.S. Valorisation of Biowastes for the Production of Green Materials Using Chemical Methods. Top. Curr. Chem. 2017, 375, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P.A.R.; Ferreira, S.S.; Bastos, R.; Ferreira, I.; Cruz, M.T.; Pinto, A.; Coelho, E.; Passos, C.P.; Coimbra, M.A.; Cardoso, S.M.; et al. Apple Pomace Extract as a Sustainable Food Ingredient. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrentino, G.; Morozova, K.; Mosibo, O.K.; Ramezani, M.; Scampicchio, M. Biorecovery of antioxidants from apple pomace by supercritical fluid extraction. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 186, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipčev, B.; Lević, L.; Bodroža-Solarov, M.; Mišljenović, N.; Koprivica, G. Quality Characteristics and Antioxidant Properties of Breads Supplemented with Sugar Beet Molasses-Based Ingredients. Int. J. Food Prop. 2010, 13, 1035–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, C.G.; Croft, K.D.; Kennedy, D.O.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A. The effects of polyphenols and other bioactives on human health. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 514–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fromm, M.; Loos, H.M.; Bayha, S.; Carle, R.; Kammerer, D.R. Recovery and characterisation of coloured phenolic preparations from apple seeds. Food Chem. 2013, 136, 1277–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaikwad, K.K.; Lee, J.Y.; Lee, Y.S. Development of polyvinyl alcohol and apple pomace bio-composite film with antioxidant properties for active food packaging application. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 53, 1608–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górnaś, P.; Mišina, I.; Olšteine, A.; Krasnova, I.; Pugajeva, I.; Lācis, G.; Siger, A.; Michalak, M.; Soliven, A.; Segliņa, D. Phenolic compounds in different fruit parts of crab apple: Dihydrochalcones as promising quality markers of industrial apple pomace by-products. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2015, 74, 607–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.K. , & Yadav, S. ( 4, 99–106.

- Halliwell, B. (1995). Letters to the Editors THE DEFINITION AND MEASUREMENT OF ANTIOXIDANTS IN. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 18(I), 125–126.

- He, Y.; Lu, Q.; Liviu, G. Effects of extraction processes on the antioxidant activity of apple polyphenols. CyTA - J. Food 2015, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellwig, M. The Chemistry of Protein Oxidation in Food. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 16742–16763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Carranza, P.; Avila-Sosa, R.; Guerrero-Beltran, J.A.; Navarro-Cruz, A.R.; Corona-Jiménez, E.; Ochoa-Velasco, C.E. Optimization of Antioxidant Compounds Extraction from Fruit By-Products: Apple Pomace, Orange and Banana Peel. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2016, 40, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyson, D.A. A Comprehensive Review of Apples and Apple Components and Their Relationship to Human Health. Adv. Nutr. Int. Rev. J. 2011, 2, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakobek, L.; Barron, A.R. Ancient apple varieties from Croatia as a source of bioactive polyphenolic compounds. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2016, 45, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Cavender, G.; Zhao, Y. Impingement drying for preparing dried apple pomace flour and its fortification in bakery and meat products. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 52, 5568–5578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinowska, M.; Gryko, K.; Wróblewska, A.M.; Jabłońska-Trypuć, A.; Karpowicz, D. Phenolic content, chemical composition and anti-/pro-oxidant activity of Gold Milenium and Papierowka apple peel extracts. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Khawli, F.; Pateiro, M.; Domínguez, R.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Gullón, P.; Kousoulaki, K.; Ferrer, E.; Berrada, H.; Barba, F.J. Innovative Green Technologies of Intensification for Valorization of Seafood and Their By-Products. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kschonsek, J.; Wolfram, T.; Stöckl, A.; Böhm, V. Polyphenolic Compounds Analysis of Old and New Apple Cultivars and Contribution of Polyphenolic Profile to the In Vitro Antioxidant Capacity. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, W.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, X.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J. Development of red apple pomace extract/chitosan-based films reinforced by TiO2 nanoparticles as a multifunctional packaging material. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 168, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Yang, R.; Ying, D.; Yu, J.; Sanguansri, L.; Augustin, M.A. Analysis of polyphenols in apple pomace: A comparative study of different extraction and hydrolysis procedures. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2020, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Peng, S.; Shi, C.; Li, C.; Hua, Z.; Cui, H. Preparation and characterization of cassava starch/sodium carboxymethyl cellulose edible film incorporating apple polyphenols. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 212, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Fernández, O.; Domínguez, R.; Pateiro, M.; Munekata, P.E.; Rocchetti, G.; Lorenzo, J.M. Determination of Polyphenols Using Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry Technique (LC–MS/MS): A Review. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, J.M.; Pateiro, M.; Domínguez, R.; Barba, F.J.; Putnik, P.; Kovačević, D.B.; Shpigelman, A.; Granato, D.; Franco, D. Berries extracts as natural antioxidants in meat products: A review. Food Res. Int. 2018, 106, 1095–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, F.; Luiz, S.; Azeredo, D.R.; Cruz, A.; Ajlouni, S.; Ranadheera, C.S. Apple Pomace as a Functional and Healthy Ingredient in Food Products: A Review. Processes 2020, 8, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massini, L.; Rico, D.; Martin-Diana, A.B.; Barry-Ryan, C. Apple peel flavonoids as natural antioxidants for vegetable juice applications. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2016, 242, 1459–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Torres, N.; Ayora-Talavera, T.; Espinosa-Andrews, H.; Sánchez-Contreras, A.; Pacheco, N. Ultrasound Assisted Extraction for the Recovery of Phenolic Compounds from Vegetable Sources. Agronomy 2017, 7, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehinagic, E.; Prost, C.; Demaimay, M. Representativeness of Apple Aroma Extract Obtained by Vacuum Hydrodistillation: Comparison of Two Concentration Techniques. J. Food Sci. 2003, 68, 2411–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei-Aghsaghali, A. & Maheri-Sis, N. (2008). Nutritive Value of Some Agro-Industrial by-Products for Ruminants - a Review. World J. Zool., 3, 40–46.

- Wandjou, J.G.N.; Lancioni, L.; Barbalace, M.C.; Hrelia, S.; Papa, F.; Sagratini, G.; Vittori, S.; Dall’Acqua, S.; Caprioli, G.; Beghelli, D.; et al. Comprehensive characterization of phytochemicals and biological activities of the Italian ancient apple ‘Mela Rosa dei Monti Sibillini’. Food Res. Int. 2020, 137, 109422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozsoy, N. , Candoken, E., & Akev, N. (2009). Implications for degenerative disorders. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, 2(2), 99–106.

- Parfitt, J.; Barthel, M.; Macnaughton, S.; Julian, P.; Mark, B.; Sarah, M.; R, J.; M, N.; I, U.; W, L.; et al. Food waste within food supply chains: quantification and potential for change to 2050. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 3065–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perussello, C.A.; Zhang, Z.; Marzocchella, A.; Tiwari, B.K. Valorization of Apple Pomace by Extraction of Valuable Compounds. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2017, 16, 776–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pingret, D.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.-S.; Le Bourvellec, C.; Renard, C.M.G.C.; Chemat, F. Lab and pilot-scale ultrasound-assisted water extraction of polyphenols from apple pomace. J. Food Eng. 2012, 111, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purić, M.; Rabrenović, B.; Rac, V.; Pezo, L.; Tomašević, I.; Demin, M. Application of defatted apple seed cakes as a by-product for the enrichment of wheat bread. LWT 2020, 130, 109391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnik, P.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Barba, F.J.; Roohinejad, S.; Režek Jambrak, A.; Granato, D.; Montesano, D.; Bursać Kovačević, D. Novel Food Processing and Extraction Technologies of High-Added Value Compounds from Plant Materials. Foods 2018, 7, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabetafika, H.N.; Bchir, B.; Blecker, C.; Richel, A. Fractionation of apple by-products as source of new ingredients: Current situation and perspectives. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 40, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, R.; Wani, S.M.; Manzoor, S.; Masoodi, F.; Dar, M.M. Green extraction of bioactive compounds from apple pomace by ultrasound assisted natural deep eutectic solvent extraction: Optimisation, comparison and bioactivity. Food Chem. 2023, 398, 133871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, S.A.; Akhter, R.; Masoodi, F.A.; Gani, A.; Wani, S.M. Utilization of apple pomace powder as a fat replacer in goshtaba: a traditional meat product of Jammu and Kashmir, India. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2015, 9, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudone, L.; Raudonis, R.; Liaudanskas, M.; Janulis, V.; Viskelis, P. Phenolic antioxidant profiles in the whole fruit, flesh and peel of apple cultivars grown in Lithuania. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 216, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, S.F.; Rai, D.K.; Abu-Ghannam, N. Water at room temperature as a solvent for the extraction of apple pomace phenolic compounds. Food Chem. 2012, 135, 1991–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riaz, A.; Lei, S.; Akhtar, H.M.S.; Wan, P.; Chen, D.; Jabbar, S.; Abid, M.; Hashim, M.M.; Zeng, X. Preparation and characterization of chitosan-based antimicrobial active food packaging film incorporated with apple peel polyphenols. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 114, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, J.S.; Santos, M.J.M.C.; Silva, L.K.R.; Pereira, L.C.L.; Santos, I.A.; Lannes, S.C.D.S.; da Silva, M.V. Natural antioxidants used in meat products: A brief review. Meat Sci. 2019, 148, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, A.F.R.; Ribotta, P.D.; Ferrero, C. Apple pomace in gluten-free formulations: effect on rheology and product quality. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 50, 682–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupasinghe, H.P.V.; Erkan, N.; Yasmin, A. Antioxidant Protection of Eicosapentaenoic Acid and Fish Oil Oxidation by Polyphenolic-Enriched Apple Skin Extract. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 58, 1233–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupasinghe, H.V.; Wang, L.; Huber, G.M.; Pitts, N.L. Effect of baking on dietary fibre and phenolics of muffins incorporated with apple skin powder. Food Chem. 2008, 107, 1217–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.-H.; Chang, Y.; Lacroix, M.; Han, J. Control of microbial growth and lipid oxidation on beef product using an apple peel-based edible coating treatment. LWT 2017, 84, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, R.C.; Gigliotti, J.C.; Ku, K.-M.; Tou, J.C. A comprehensive analysis of the composition, health benefits, and safety of apple pomace. Nutr. Rev. 2018, 76, 893–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soquetta, M.B.; Terra, L.d.M.; Bastos, C.P. Green technologies for the extraction of bioactive compounds in fruits and vegetables. CyTA - J. Food 2018, 16, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudha, M.; Baskaran, V.; Leelavathi, K. Apple pomace as a source of dietary fiber and polyphenols and its effect on the rheological characteristics and cake making. Food Chem. 2007, 104, 686–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudha, M.L.; Dharmesh, S.M.; Pynam, H.; Bhimangouder, S.V.; Eipson, S.W.; Somasundaram, R.; Nanjarajurs, S.M. Antioxidant and cyto/DNA protective properties of apple pomace enriched bakery products. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 53, 1909–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, W.; Sun, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, G.; Zhou, G.; Xu, X.; Xu, X.; Peng, Z.; Peng, Z. EFFECT OF APPLE POLYPHENOL ON OXIDATIVE STABILITY OF SLICED COOKED CURED BEEF AND PORK HAMS DURING CHILLED STORAGE. J. Muscle Foods 2010, 21, 722–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Sun, J.; Thavaraj, P.; Yang, X.; Guo, Y. Effects of thinned young apple polyphenols on the quality of grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus) surimi during cold storage. Food Chem. 2017, 224, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Sun, J.; Chen, L.; Niu, P.; Yang, X.; Guo, Y. Preparation and characterization of chitosan film incorporated with thinned young apple polyphenols as an active packaging material. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 163, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Sun, J.; Liu, D.; Fu, M.; Yang, X.; Guo, Y. The preservative effects of chitosan film incorporated with thinned young apple polyphenols on the quality of grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus) fillets during cold storage: Correlation between the preservative effects and the active properties of the film. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2018, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigo, J.P.; Alexandre, E.M.C.; Saraiva, J.A.; Pintado, M.E. High value-added compounds from fruit and vegetable by-products – Characterization, bioactivities, and application in the development of novel food products. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 60, 1388–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Ahmed, S.; Mehmood, A.; Bilal, M.; Patil, P.J.; Akram, K.; Farooq, U. Effect of apple pomace on nutrition, rheology of dough and cookies quality. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, 3244–3251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virot, M.; Tomao, V.; Le Bourvellec, C.; Renard, C.M.; Chemat, F. Towards the industrial production of antioxidants from food processing by-products with ultrasound-assisted extraction. Ultrason. Sonochemistry 2010, 17, 1066–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Malik, A.; Pathera, A.; Islam, R.U.; Sharma, D. Development of dietary fibre enriched chicken sausages by incorporating corn bran, dried apple pomace and dried tomato pomace. Nutr. Food Sci. 2016, 46, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).