1. Introduction

Arrowroot (

Maranta arundinacea L.) is a tuber plant with a rhizome root elongated like an arrow. Arrowroot tubers have been considered inferior commodities and have not been utilized optimally. Arrowroot tuber is one of the commodity sources of carbohydrates which can be processed into starch or flour. Starch can be used as a food thickener, stabilizer, and emulsifier [

1]. Starches commonly found in the market are corn starch (maize) and cassava starch (tapioca), even though many other starch sources have the potential to be developed, one of which is arrowroot starch.

Native arrowroot starch has several limitations, such as low thermal stability and susceptibility to acidic conditions, which are generally used in processing in the food industry [

2]. To improve the characteristic of native arrowroot starch, modifications were applied. A modification method that can be used to enhance thermal stability is the heat-moisture treatment (HMT) method [

3,

4]. However, several studies have shown that HMT increases starch syneresis [

5,

6]. Dual modification technology is an alternative to overcome the weakness of HMT starch by combining HMT modification treatment with other modification treatments, for example, chemical modification. This study combined both modified treatments using heat-moisture treatment and octenylsuccinilation using octenyl-succinic anhydride (OSA). Modification of OSA has advantages because it can increase the hydrophobicity of starch [

7,

8]. OSA starch can be applied as an emulsifier or used as a fat replacer in high-fat products resulting in decreased fat products [

8,

9,

10].

Information regarding the modification of arrowroot starch modified by two methods, HMT and OSA is still limited. This current study aimed to determine the physicochemical and pasting properties of native and modified starches, both single and dual modifications using HMT and OSA in the reverse sequence. HMT and OSA-modified starch is expected to be an ingredient in the manufacture of a functional food because each single modification treatment has advantages from a health perspective, namely HMT-modified starch has highly slowly digestible starch making it suitable for diabetics [

11], while single OSA modification can produce starch which can replace the role of fat, to produce low-fat products [

8].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The raw material used in this research is arrowroot tubers (Maranta arundinacea L.) cultivated in Pangandaran, West Java, Indonesia. All chemicals used for the modification process were 2-octen-1-ylsuccinic anhydride (OSA) (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), hydrochloric acid, sodium hydroxide, ethanol 95%, acetic acid, isopropanol, AgNO3, and phenolphthalein, with specification analytical grade.

2.2. Arrowroot Starch Isolation

Arrowroot starch isolation method was followed according to Marta, et al. [

11] with a slight modification. The tubers were peeled and cut into small pieces, then soaked in water with a tuber/water ratio of 1:5. The tubers were crushed to form a pulp using a blender (Sharp EM-121-BK, Japan) for 2 minutes. The resulting slurry is squeezed using a muslin cloth. The slurry was allowed to precipitate for 18 hours. Then decanted until the grey layer was removed with a spatula, and the starch was washed and re-precipitated by centrifugation (SL 16 Centrifuge, Thermo Scientific, USA) at 5000 rpm for 2-3 minutes. This process was repeated 3-4 times until the starch was completely clean, indicated by the absence of a grey layer. Then starch was dried in a drying oven at 50 ºC for 24 hours. The dry starch was then ground and sieved with a 100-mesh sieve.

2.3. Heat-Moisture Treated (HMT) Starch Preparation

Preparation of HMT-starch refers to Marta, et al. [

12]. The moisture content of arrowroot starch was adjusted to 30% (±2%) by adding distilled water. Then it was equilibrated at 4 ºC for 24 hours in the refrigerator. The starch was transferred to a tightly closed Teflon and heated at 100 ºC for 8 hours. The modified starch was dried in a drying oven at 50 ºC for 24 hours, and then was ground and sieved (sieve no. 100 mesh).

2.4. Octenylsuccinilated (OSA) Starch Preparation

Preparation of OSA-starch refers to Marta, et al. [

13] with a slight modification. Starch was dissolved in distilled water to form a starch suspension of 30% (w/w). The pH of the starch suspension was adjusted to pH 8 using 1 M NaOH. When the pH was reached, 3% OSA (w/w) was added, and OSA was carried out slowly. The suspension was stirred for 3 hours. During the modification process, the pH of the suspension was adjusted and maintained in the range of 8.0-8.5 using 1 M NaOH and 1 M HCl. After the reaction, the starch suspension was neutralized to pH 6.5 using 1 M HCl. Starch was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 2-3 minutes. The precipitated starch was washed using distilled water and then centrifuged again, and this process was repeated 2-3 times. Then the starch was dried in a drying oven at 50 ºC for 24 hours. The dried modified starch was ground and sieved (No. 100 mesh sieve).

2.5. Dual Modification by HMT followed by OSA (HMT-OSA)

The native starch of arrowroot was modified by HMT, as mentioned in section 2.3 then followed by OSA modification, as mentioned in section 2.4, and the obtained starch was named HMT-OSA starch.

2.6. Dual Modification by OSA followed by HMT (OSA-HMT)

The native starch of arrowroot was modified by OSA, as mentioned in section 2.4, then followed by HMT modification, as mentioned in section 2.3, and the obtained starch was named OSA-HMT starch.

2.7. Granule Morphology Observation Using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

Granular morphology was determined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), a JEOL JSM-6360 LA at 15 kV. Mounted starch samples were coated with gold/palladium at 8-10 mA for 10-15 min under low pressure (less than 10 tors). Representative digital images of native and modified starch granules were obtained at 5000 and 10000 magnifications.

2.8. Starch Crystallinity using X-Ray Diffractometer (XRD)

The crystallinity of native and modified arrowroot starch was measured using PAN Analytical X’Pert PRO series PW3040/x0 (X-ray diffraction) that operated using Cu-K alpha radiation with a wavelength of 1.540 nm as an X-ray source at 30 mA and 40 kV. The diffraction angle (2θ) scanning was from 3.0º to 50.0º with a scanning rate time of 2.9 s. Crystallinity was calculated using OriginLab Program.

2.9. Thermal Properties Determination Using Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

Thermal properties of starch were measured using differential scanning calorimetry (DSC-Q100, TA Instruments). The parameters observed were To (onset temperature), Tp (peak temperature), Tc (conclusion temperature), and ∆H (enthalpy of gelatinization). Starch was made into a slurry, with the ratio of water and starch being 3:1. The slurry was then hermetically sealed using a DuPont encapsulation press before weighing. Then the sample was heated at a rate of 5 °C/min from 20 to 100 °C.

2.10. Pasting Properties Determination Using Rapid Visco Analyzer (RVA)

The pasting properties of arrowroot starch were determined using a Rapid Visco Analyzer (RVA StarchMaster 2, Parten Instruments). 3 g of starch samples were added with 25 mL of distilled water in the RVA canister tube and stirred in an RVA canister at 960 rpm for 10 seconds. RVA was set with a temperature profile, initially held at 50 ºC for 1 minute, the heating from 50 to 95 ºC for 3.7 minutes, the temperature was held at 95 ºC for 2.5 minutes, then cooling to 50 ºC in 3.8 minutes and kept at 50 ºC for 2 minutes. The gel was then maintained at 50 ºC for 2 minutes with constant paddle rotational speed (160 rpm) used throughout the analysis, and the total analysis time was 12 minutes. The pasting properties included the following parameters: pasting temperature (PT), peak viscosity (PV), hold viscosity (HV), final viscosity (FV), breakdown (BD), and setback (SB).

2.11. Texture Profile Analysis Evaluation Using Texture Analyzer (TA)

Texture properties of RVA gels were evaluated on a Texture Analyzer TA-XT express enhanced (Stable Micro System, Surrey, UK) and exponent lite express software for data collection and calculation. The gelatinized starch in the canister after the RVA measurement was poured into cylindrical plastic tubes (20 mm diameter, 40 mm deep) and then kept at 4 ºC for 24 hours to form a solid gel. Each gel sample in the tube was penetrated with a cylindrical probe (P36/R) at a speed of 5 mm/s to a distance of 10 mm for two penetration cycles. The texture profile curves were used to calculate hardness, adhesiveness, springiness, cohesiveness, and gumminess.

2.12. Functional Properties

Swelling volume and solubility in arrowroot starch were measured refers to Marta, et al. [

13]. The sample's 0.35 g (d.b) was mixed with 10 mL distilled water and put into a centrifuge tube. Then it was mixed using a vortex mixer for 20 seconds. Then the sample was heated in a water bath for 30 minutes at a temperature of 92.5 ºC and stirred regularly. The sample was cooled for 1 minute in ice water and centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 15 minutes, then, the supernatant was separated, and the volume was measured. Swelling volume was calculated using the equation:

After being separated, the supernatant was dried in a drying oven for 24 hours. Solubility was calculated using the equation:

Water absorption capacity (WAC) and oil absorption capacity (OAC) were measured using the method Marta, et al. [

13]. One gram (d.b) of the starch sample was added with 10 mL of distilled water or oil into a centrifuge tube, then mixed using a vortex for 20 seconds. Samples were stored at room temperature for 1 hour and then centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 30 minutes. The volume of the supernatant (water or oil) was measured and separated. WAC and OAC are calculated using the following equation:

Freeze-thaw stability or syneresis was determined by a previous method [

12] with a slight modification. An aqueous starch suspension (5%) was prepared and heated at 95 ºC for 30 minutes with constant light stirring, then cooled to room temperature in an ice water bath. Then 20 g aliquots of the paste were taken and put into a centrifuge tube, and then a freeze-thaw cycle was carried out with storage at 4 ºC for 24 hours, then frozen at -15 °C for 48 hours and thawed at 25 ºC for 3 hours. Then the samples were centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 15 minutes. After centrifugation, the supernatant removed from the gel was weighed, and the syneresis was calculated using the following equation:

2.13. Color Analysis Using CM-5 Spectrophotometer

The starch color was measured using a CM-5 Spectrophotometer (Konica Minolta Co., Osaka, Japan) with Spectra Magic Software. The samples were placed in a glass cell and above the light source. After that, measurements were taken at room temperature. The parameters measured were CIE-lab, namely the L*, a*, and b* values in each sample. L* value indicates the lightness (whiteness/darkness), representing dark (0) to light (100); a* value indicates the degree of red-green color ((+) redness/(-) greenness); and b* value indicates the degree of the yellow-blue color ((+) yellowness/(-) blueness). The following equation was used to calculate the total color differences between starch samples [

14]:

L*, a*, b* were parameters for modified starch and ,, were parameters for native starch.

The values for whiteness were determined using the following equation [

15]:

2.14. Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± SD of triplicate experiments. All data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a further Duncan test to compare the sample mean at a significance level of 5% (p < 0.05). All data were analyzed using Statistical Software Program (IBM SPSS Statistics version 25).

3. Results

3.1. Granule Morphology

The Granule morphology of native and modified arrowroot starches is presented in

Figure 1. The granules of arrowroot starch are spherical, and ellipsoid to oval-shaped. There was no damage on the surface of starch granules after OSA. In HMT-modified starch, both single and dual modifications (HMT, HMT-OSA, and OSA-HMT), the damage occurred on the surface of the granules, where the surface became rougher due to the formation of fine cracks.

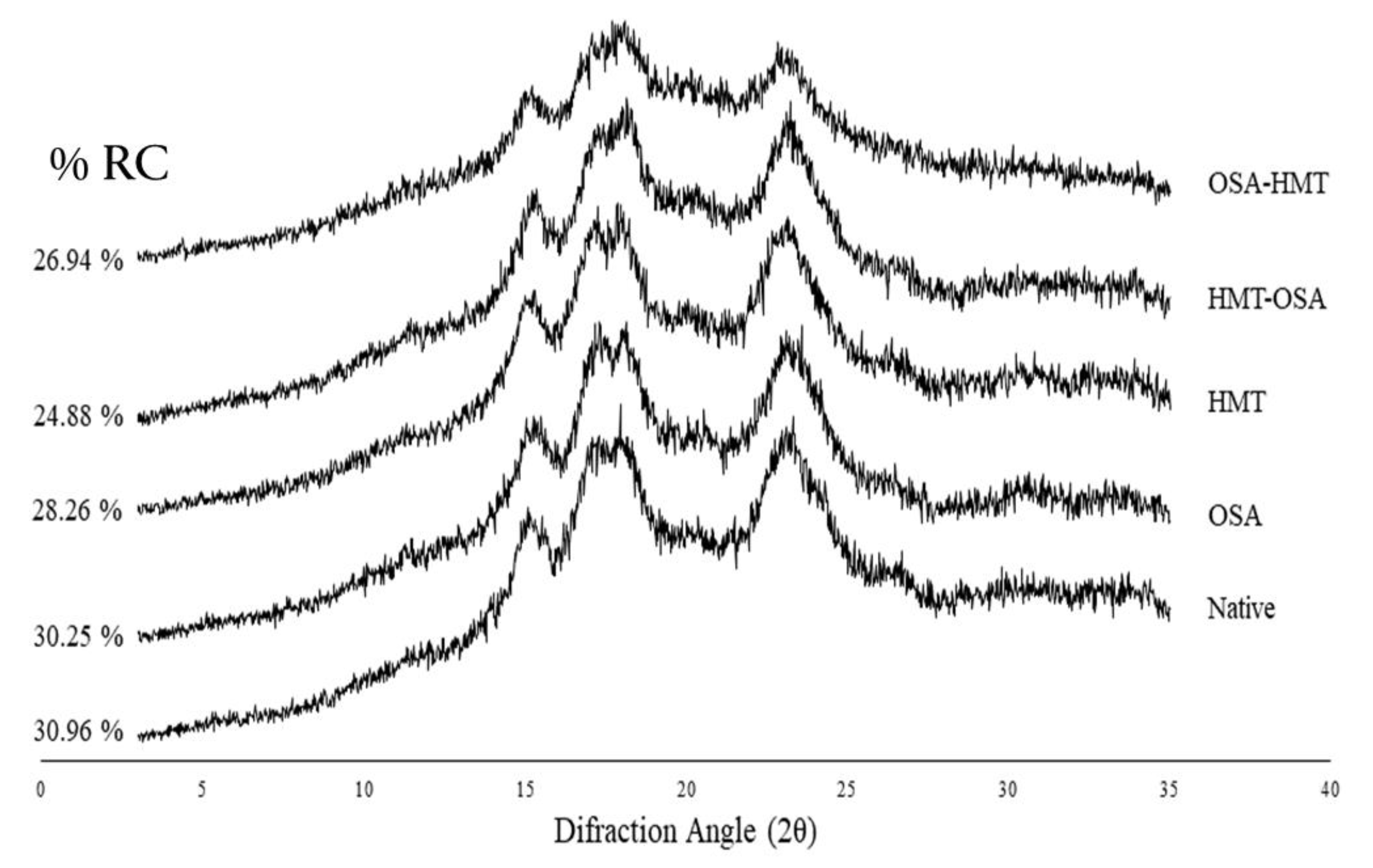

3.2. Starch Crystallinity

Native arrowroot starch has an A-type crystalline pattern which was indicated by several diffraction peaks at 15°, 17°, 18°, 23°, and 26° 2θ (

Figure 2). All modification treatments did not alter the crystallinity pattern whereas change the relative crystallinity (RC) of native arrowroot starch. All modified starches have a lower relative crystallinity than native starch. In HMT-modified starch, both single and dual modifications (HMT, HMT-OSA, and OSA-HMT) have a greater effect on RC than single OSA modification.

3.3. Thermal Properties

DSC is used for thermal analysis to determine the transition of starch crystallinity caused by heating. The native of starch gelatinization is determined by the following parameters: (1) T

o or temperature onset, which is the temperature at which gelatinization begins, also defined as the melting temperature of the weakest crystals in starch granules; (2) T

p or peak temperature which represents the endothermic peak on the DSC thermogram; (3) T

c or conclusion temperature is the final temperature at which the sample is wholly gelatinized or crystalline melting temperature (high-perfection crystalline); and (4) ΔH or enthalpy (J/g) calculated based on the DSC endotherm, expressing the energy required to break the double helix structure during starch gelatinization [

12,

16].

The thermal properties of native and modified arrowroot starches are presented in

Table 1. All modified starch has a lower T

o and T

p than native, except for OSA-HMT starch. The temperature range (T

c-T

o) of modified starches increased whereas enthalpy decreased after modification from 45.83 ºC to 47.80 – 67.50 ºC and 528.54 (J/g) to 67.11 – 198.33 (J/g), respectively.

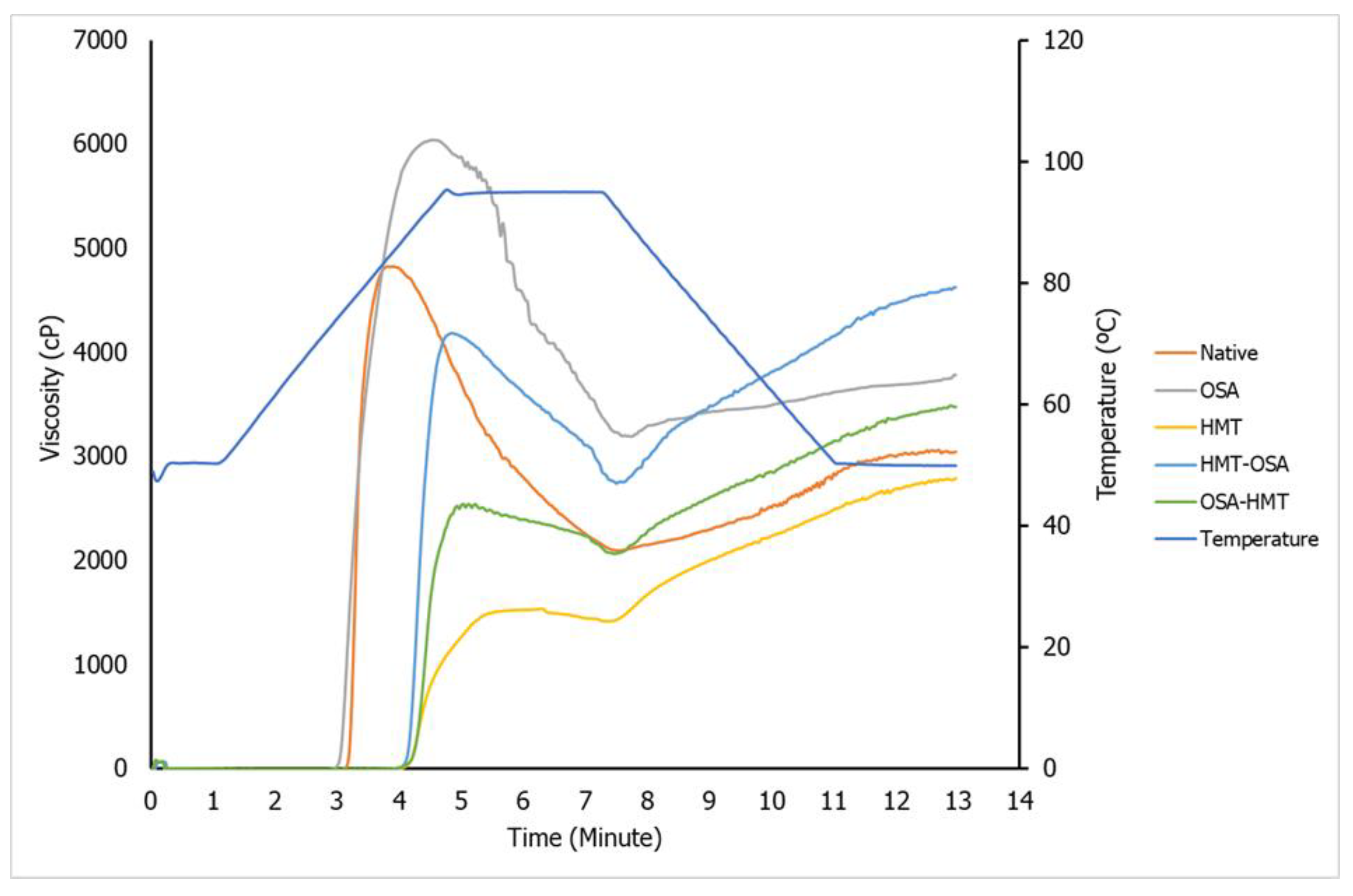

3.4. Pasting Properties

The viscoamylograph and pasting properties parameters of native and modified arrowroot starches are presented in

Figure 3 and

Table 2, respectively. Both single HMT and dual modifications (HMT-OSA, OSA-HMT) increased PT and SB of native, conversely, decreased PV and BD viscosity of native starch. Whereas, single OSA has the opposite trend compared with the other modification treatments.

3.5. Texture Properties

Texture properties parameters of native and modified arrowroot starches are presented in

Table 3. Both single modifications, OSA and HMT alone, increased the gel hardness of native arrowroot starch, conversely affect on the dual modifications. All modified starches have higher adhesiveness and lower springiness and cohesiveness than native starch. Both dual modifications, HMT-OSA and OSA-HMT, decreased the gumminess of native arrowroot starch from 208.95 to 29.21 – 59.60.

3.6. Functional Properties

OSA modification, both single OSA and dual HMT-OSA significantly increased SV of native starch, but conversely trend for OSA-HMT. All modified starch has lower solubility and higher syneresis than native starch. HMT starch, both single HMT and dual modifications (HMT-OSA, OSA-HMT) increased water absorption capacity (WAC) and decrease oil absorption capacity (OAC) of native starch. All modification treatments increased the syneresis of native starch.

WAC describes the amount of water available for gelatinization [

12]. WAC of native and modified arrowroot starches ranges from 0.83 – 1.60 g/g (d.b). The WAC of native arrowroot starch is 1.13 g/g db, which is smaller than the previous study, 1.81 g/g db [

17]. OAC shows the ability of starch to absorb oil, and this is an indication of the emulsifying potential of starch [

18]. The OAC of native and modified arrowroot starches ranges from 2.15 – 2.33 g/g db. All modification methods, except for OSA decreased the OAC of native starch from 2.33 g/g db to 2.15 – 2.21 g/g db.

Table 4.

Functional properties of native and modified arrowroot starches.

Table 4.

Functional properties of native and modified arrowroot starches.

| Treatment |

Swelling Volume (ml/g db) |

Solubility (%) |

WAC (g/g db) |

OAC (g/g db) |

Syneresis (%) |

| Native |

16.27 ± 0.12c

|

9.33 ± 0.14c

|

1.13 ± 0.20b

|

2.33 ± 0.03b

|

7.02 ± 0.06a

|

| OSA |

25.84 ± 0.56e

|

9.13 ± 0.21b

|

0.83 ± 0.10a

|

2.31 ± 0.07b

|

18.71 ± 0.96b

|

| HMT |

11.46 ± 0.54a

|

8.92 ± 0.14a

|

1.35 ± 0.05c

|

2.15 ± 0.12a

|

38.76 ± 0.49c

|

| HMT-OSA |

17.66 ± 0.17d

|

9.08 ± 0.09b

|

1.41 ± 0.07c

|

2.21 ± 0.09a

|

59.06 ± 2.27d

|

| OSA-HMT |

14.31 ± 0.34b

|

8.90 ± 0.04a

|

1.60 ± 0.06d

|

2.20 ± 0.04a

|

65.80 ± 3.54e

|

3.7. Color Characteristics

The color parameters of native and modified arrowroot starches are presented in

Table 5. HMT modification, both single HMT and dual modifications (HMT-OSA and OSA-HMT) significantly decreased the L* value of native arrowroot starch. Single OSA did not alter a

* value, whereas HMT modification both single and dual give a different effect on a

* value of native arrowroot starch. Native and OSA-modified arrowroot starches have a negative value of a

* which indicated the color tends to greenness, whereas all HMT modifications have a positive value of a

* which was indicated the color tends to redness.

Figure 3.

The color of arrowroot starch (a) native, (b) OSA, (c) HMT, (d) HMT-OSA, and (e) OSA-HMT. The color image was captured from Spectrophotometer CM-5.

Figure 3.

The color of arrowroot starch (a) native, (b) OSA, (c) HMT, (d) HMT-OSA, and (e) OSA-HMT. The color image was captured from Spectrophotometer CM-5.

4. Discussion

4.1. Granule morphology

Native arrowroot starch has a round, oval shape with a granular surface that is slightly textured without cracks. The morphology of OSA starch granules did not show significant changes compared to native starch granules. Whereas, the HMT caused damage to the starch granules, where cracks formed, and the surface of the granules became rougher. This was due to the thermal strength, which changes the morphology of arrowroot starch [

11]. Both dual-modified starch granules (OSA-HMT and HMT-OSA) showed similar surface characteristics to HMT starch. The surface of the granules becomes rougher, and there were indentations. This indicated that thermal treatment significantly dominates the alteration of granule morphology of dual-modified arrowroot starch.

4.2. Crystallinity

X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) is the method for assessing and quantifying long-range crystalline order in starch [

19].

Figure 2 shows that native and modified starches have a similar crystallinity pattern that was an A-type crystalline pattern as indicated by several diffraction peaks at 2θ 15°, 17°, 18°, 23°, and 26° [

20], which indicated that all modification treatment did not significantly affect the crystalline type of native arrowroot starch. Several studies have reported that native arrowroot starch has an A-type crystalline pattern [

1,

21]. However, this result was not in agreement with another study by Nogueira, et al. [

22] which reported that arrowroot starch has a C-type crystalline pattern, indicating a mixture of polymorphs type A and B. The HMT showed no change in the crystalline pattern, similar to the study of Marta, et al. [

11] on banana starch and a similar trend on OSA-sago starch [

13].

Relative crystallinity (RC) was calculated based on the ratio of the diffraction peak area (crystalline area) to the total diffraction area [

23]. All modification treatments decreased the RC of native starch. Arrowroot native starch has an RC of 30.96%, which was in range with the other studies that of 52,84% [

24] and 28,8-30,2% [

25]. Several studies have reported that HMT decreased the RC, such as in sago starch [

13]; banana starch [

11] [

13]; mango kernel starch [

26]; breadfruit starch [

6]; rice, cassava, and pinhão starches [

27]. Decreased RC in hydrothermally modified starches, both single HMT and dual modifications (HMT, HMT-OSA, and OSA-HMT) can be associated with changes in the crystalline phase (amylopectin) of starch, where dehydration and double helix movements can disrupt starch crystallinities and change crystal orientation of the semi-crystalline fraction to the amorphous phase [

28,

29,

30] or possibly partial gelatinization [

4,

31]. The RC of OSA starches, both single and dual modified starches (OSA, OSA-HMT, and HMT-OSA) was smaller than its native starch, which was in line with some previous studies [

13,

32,

33]. These results indicated that OSA esterification occurs in the amorphous region of starch granules and slightly changes the starch crystal structure.

4.3. Thermal Properties

Esterification using OSA on arrowroot starch causes a decrease in T

o, T

p, and ΔH compared to native starch which was in agreement with some previous studies [

34,

35]. The decrease in temperature and gelatinization enthalpy was caused by the disruption of the crystal structure of the starch granules because OSA molecules tend to weaken the interactions between starch macromolecules, which allows the granules to swell and melt at lower temperatures [

7]. The decrease in T

o, T

p, T

c, and ΔH values in HMT starch might be due to the weak interactions between amylose-amylose, amylose-amylopectin, and amylose-lipid, which caused imperfect crystal formation. Some previous studies reported that HMT-modified starch showed higher gelatinization parameters (T

o, T

p, T

c) than native starch [

12,

28,

36,

37]. Dual HMT-OSA starch tends to have thermal profile characteristics that are almost similar to single modified both OSA and HMT starches, but OSA-HMT starch gives an entirely different thermal profile than other modified starches, where there is an increase in T

o, T

p, and T

c.

4.4. Pasting Properties

The increase in PT and decrease PV on HMT starch, both single HMT and dual modifications (HMT-OSA and OSA-HMT) could be due to the partial breakage of the ordered chain structure and the rearranging of the broken molecules, facilitated by the high temperature (100 °C) and limited moisture content (30%) during HMT. As a result, the forces of the intra-granular bonds would be augmented, and the linkages between starch chains would be strengthened. The HMT-treated starch samples needed greater heat for structural breakdown and paste production, resulting in a lower paste viscosity. On the other hand, an increase in PV was observed in single OSA-treated starch. According to Bajaj, et al. [

8], substituting bulky octenyl groups could decrease the inter and intramolecular bond between starch granules, resulting in limited incorporation of water into starch molecules. When OSA groups are substituted, the starch granule is destroyed, which enhances swelling and raises PV. The hydrophobic properties of OSA also increased the viscosity of starch. This characteristic was discovered advantageous for making mayonnaise with improved emulsion stability [

8].

The significant difference in PV between HMT-OSA and OSA-HMT-treated starch is because HMT facilitated this OSA particle to attack more –OH group in starch. According to Park, et al. [

38], HMT before cross-linking could increase the phosphate content of the starch, showing that the HMT facilitates the incorporation of the cross-linking agent to react more with starch granules. This similar occurred in the octenyl group as well. The OSA modification increased the BD which was in line with some previous studies [

8,

39], whereas the other modifications significantly decreased the BD of the native starches. The lower BD indicated the higher thermal stability of starch. All HMT modifications, both single and dual modifications have a higher SB than native and single OSA starch, which indicated that HMT increases the ability of starch to retrograde.

4.5. Texture Properties

Texture parameters in starch have an important role because starch is a texturizer agent such as a thickening and gelling agent. TPA (texture profile analysis) is used to observe texture parameters such as hardness, adhesiveness, springiness, cohesiveness, and gumminess [

40]. Gel hardness or hardness is related to the strength of the gel network, and changes in hardness are related to the effect of swelling granules and amylose content [

40,

41], hardness increases with increasing amylose content. The gel network structure depends on the quantity and intensity of hydrogen bonds formed between the amylose chains [

42]. The increased hardness of both single HMT and OSA starch compared to native starch is thought to be related to the starch's ability to swell because decreased swelling makes the granules stiffer. Furthermore, reduced amylose leaching also reduces the amount of water in the gel network. Therefore the gel structure will be more compact, and the hardness will increase [

40]. The hardness of dual-modified starch (OSA-HMT and HMT-OSA starch) decreased very sharply compared to native starch and single-modified starch. The adhesiveness of native starch was higher than all modified starch, which was in line with the other studies [

43,

44]. All modification treatments did not significantly affect the springiness of starch gel, whereas decreased the cohesiveness which might be due to the degradation of starch molecules, resulting in a weaker starch network structure. Gumminess is the elasticity of a semi-solid product, and this parameter depends on the level of hardness and cohesiveness of the product [

45]. Dual-modified starches tend to have low value, especially HMT-OSA starches. The low level of elasticity in this dual-modified starch is influenced by its low hardness and small cohesive strength compared to single-modified starch (OSA and HMT).

4.6. Functional Properties

Swelling volume (SV) measures the hydration capacity of starch molecules due to the presence of water trapped in granules [

46]. SV is related to amylose leaching or the solubility of starch [

47]. Due to the solubility is the result of leaching out of amylose, which dissociates and diffuses out of the starch granules during the gelatinization process, which causes swelling in the starch [

10].

The SV of HMT starch decreased when compared to native, which was in line with other studies [

2,

12,

48]. Furthermore, the decrease might be due to the rearrangement of starch molecules, increased intramolecular forces [

48], and amylose-amylose, amylopectin-amylose, amylopectin-amylopectin interactions which become stronger where the starch granules become more rigid [

11]. Among other modified starches, OSA starch has the highest SV. Furthermore, Park, et al. [

47] reported that the SV of OSA arrowroot starch was significantly higher than its native starch. This increase in swelling strength is associated with an increase in the ability of water to percolate into starch granules [

49]. HMT-OSA-modified starch had a higher SV than OSA-HMT starch. It was presumed that the HMT process resulted in cracks and porous starch granules. When the OSA treatment was applied, the presence of succinate groups could weaken the internal bonds in the starch granules and increase the percolation of water so that the SV of HMT-OSA starch became higher [

49,

50].

All modified starches have lower solubility than native starch, which was caused by amylose leaching during the starch gelatinization process. Amylose is in the crystalline region and relatively small in size and linear shape, making it easier to leach out from the starch granules [

25]. However, another study [

24] has reported that HMT on corn starch increased its solubility which was influenced by the treatment time; the longer the treatment time, the more solubility [

2].

Among the modified starches, OSA-starch has the lowest WAC (0.83 g/g d.b). The reduced WAC on OSA starch was due to the presence of a hydrophobic substituent group from OSA that replaces the hydroxyl group on starch granules which causes an increase in the hydrophobicity of starch [

51]. Whereas HMT starch increased WAC (1.35 g/g db), which was in agreement with some previous studies [

47,

52]. The increased WAC of HMT-starch was caused by the breaking of hydrogen bonds in the crystalline and amorphous regions resulting in the expansion of the amorphous areas, which increased the hydrophilic properties of starch [

18,

53]. The presence of pores on the surface of starch granules can also increase WAC because it will be easier for water to diffuse into the granules [

12]. The increased WAC in dual-modified starch (HMT-OSA and OSA-HMT) was significantly influenced by the second modification treatment applied because HMT-OSA starch showed a lower WAC than OSA-HMT starch. OSA treatment after HMT was suspected to reduce starch hydrophilicity and increase its hydrophobicity due to the presence of OSA groups so decreased WAC.

The esterification process with OSA increased starch's hydrophobicity, thereby increasing the OAC [

7]. On the other hand, the OAC is related to the degree of substitution (DS), where the absorption capacity of oil increases with the degree of substitution of OSA [

54].

Freeze-thaw stability was determined as syneresis (%). Syneresis releases water from gel or starch paste during cooling, storage, and freeze-thawing [

55]. High syneresis indicates low stability at low-temperature storage [

12]. Native arrowroot starch has the lowest syneresis among other starches, which was in agreement with some previous studies on arrowroot starch [

56,

57]. All modification applied in this study tends to increase syneresis. However, when compared among modified starches, OSA starch has higher stability, which indicated that OSA starch is more stable at low-temperature storage conditions. A previous study reported that the modification of starch into succinate derivatives (OSA starch) can improve the freeze-thaw stability (FTS) of corn and amaranth starch [

46]. This is associated with a steric effect on the OSA group, which can prevent starch chain alignment when stored at low temperatures [

7], whereas in this study OSA modification can not improve FTS of native arrowroot starch. Increased syneresis in HMT starch might be due to the resulting random interactions reducing the water-holding capacity of the starch gel [

58]. The intensity of syneresis depends on various factors, such as the composition of the amylose fraction, the length of the amylopectin chains, and the degree of polymerization of amylose and amylopectin [

53].

4.7. Color Analysis

Color is a characteristic that has an important role in determining the quality and level of consumer acceptance in selecting a product. In flour or starch products, consumers generally prefer products that are white or bright in color. Color testing of products, mainly arrowroot starch, can be carried out using a spectrophotometer (Spectrophotometer CM-5) to determine the color intensity (L*, a*, and b*) of native and modified starches.

The highest lightness (L*) was shown by OSA starch (96.39), while HMT starch showed the lowest lightness (94.96). There was a significant difference in lightness, especially for HMT-modified starch. This is presumably because thermal treatment can cause the degradation of color pigments in starch. The redness (a*) in arrowroot starch with a negative value is indicated by both native and OSA starches, which indicated a tendency to be green in color. Meanwhile, the positive values for HMT starches, both single HMT and dual modified starches (HMT-OSA and OSA-HMT starches) indicated that these starches tended to be red. The color shift to red was caused by the application of thermal treatment. The level of yellowness (b*) in all arrowroot starch (native and modified) has a positive value indicating that all starch leads to a yellow color. The highest b* value was shown by HMT starch (4.07), while the lowest was indicated by OSA starch (2.13). It means that HMT starch is more yellow than OSA starch (

Figure 3).

The whiteness index (WI) is based on a scale of 0-100, with the highest value described as the highest level of lightness. The WI value is positively correlated with the L* value; the higher the WI, the higher the L* value. HMT-modified starch, both single HMT and dual-modified starches had low WI. The HMT modification process that was carried out reduced the lightness level of starch. Total color difference (∆E) is a parameter used to assess how much change or difference in the Lab* value results in ingredients or food after specific treatments [

59]. Dual modification, especially OSA-HMT starch, has the smallest ∆E value which indicated that the color produced between native and OSA-HMT starch was not much different. Whereas HMT starch showed the highest ∆E value, in which there was a significant difference/change in starch color compared to native starch.

5. Conclusions

All modification treatments, both single and dual modifications had significant effects on granule morphology, crystallinity, thermal, pasting, and functional properties, texture, and color characteristics of native arrowroot starch. The granules of arrowroot starch are spherical, and ellipsoid to oval-shaped. There was no damage on the surface of starch granules after OSA. In HMT-modified starch, both single and dual modifications (HMT, HMT-OSA, and OSA-HMT), the damage occurred on the surface of the granules. Native and modified starches have a similar crystallinity pattern that was an A-type crystalline pattern. All modification treatments decreased the RC of native starch, where HMT has a greater effect on RC than OSA. Both single HMT and dual modification (HMT-OSA, OSA-HMT) increased PT and SB, conversely, decreased PV and BD viscosity of native starch. All HMT treatments, both single and dual modifications can improve the thermal stability of native starch, especially HMT single treatment. Whereas OSA single treatment has the opposite trend compared with the other modification treatments. OSA starch has a firm texture characteristic which was indicated by the high value of hardness and gumminess. Both single OSA treatment and HMT-OSA significantly increased SV of native starch, but conversely trend for OSA-HMT. All modified starches have lower solubility and higher syneresis than native starch. Both single HMT modification and dual modifications (HMT-OSA, OSA-HMT) increase WAC and decrease the OAC of native starch. HMT starch both single and dual modifications have low L* and WI values, while OSA starch has the brightest color among other starches.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.M. and M.D.; methodology, H.M. and D.S.; software, A.R.; validation, H.M, Y.C., and M.D.; formal analysis, A.R. and G.P.S.; investigation, H.M. and T.Y.; data curation, D.S., A.R. and G.P.S.; writing—original draft preparation, H.M., A.R. and G.P.S.; writing—review and editing, Y.C., M.D. and T.Y.; visualization, A.R. and G.P.S.; supervision, H.M., Y.C. and M.D.; funding acquisition, H.M. and Y.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Grant of Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology (MoECRT), Republic of Indonesia [grant number: 2393/UN6.3.1/PT.00/2022] and The APC was funded by Universitas Padjadjaran.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the facilities, scientific and technical support from Advanced Characterization Laboratories Cibinong – Integrated Laboratory of Bioproduct, National Research and Innovation Agency through E-Layanan Sains, Badan Riset dan Inovasi Nasional.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- Tarique, J.; Sapuan, S.M.; Khalina, A.; Sherwani, S.F.K.; Yusuf, J.; Ilyas, R.A. Recent Developments in Sustainable Arrowroot (Maranta Arundinacea Linn) Starch Biopolymers, Fibres, Biopolymer Composites and Their Potential Industrial Applications: A Review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 13, 1191–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepe, L.S.; Moraes, J.; Albano, K.M.; Telis, V.R.; Franco, C.M. Effect of Heat-Moisture Treatment on the Structural, Physicochemical, and Rheological Characteristics of Arrowroot Starch. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2016, 22, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polesi, L.F.; Sarmento, S.B.S. Structural and Physicochemical Characterization of Rs Prepared Using Hydrolysis and Heat Treatments of Chickpea Starch. Starch - Stärke 2011, 63, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavareze, E.d.R.; Dias, A.R.G. Impact of Heat-Moisture Treatment and Annealing in Starches: A Review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 83, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahyana, Y.; Wijaya, E.; Halimah, T.S.; Marta, H.; Suryadi, E.; Kurniati, D. The Effect of Different Thermal Modifications on Slowly Digestible Starch and Physicochemical Properties of Green Banana Flour (Musa Acuminata Colla). Food Chem. 2019, 274, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marta, H.; Cahyana, Y.; Arifin, H.R.; Khairani, L. Comparing the Effect of Four Different Thermal Modifications on Physicochemical and Pasting Properties of Breadfruit (Artocarpus Altilis) Starch. Int. Food Res J. 2019, 26, 269–276. [Google Scholar]

- Sweedman, M.C.; Tizzotti, M.J.; Schäfer, C.; Gilbert, R.G. Structure and Physicochemical Properties of Octenyl Succinic Anhydride Modified Starches: A Review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 92, 905–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajaj, R.; Singh, N.; Kaur, A. Properties of Octenyl Succinic Anhydride (Osa) Modified Starches and Their Application in Low Fat Mayonnaise. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 131, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; He, X.; Huang, Q. Effects of Hydrothermal Pretreatment on Subsequent Octenylsuccinic Anhydride (Osa) Modification of Cornstarch. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 101, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura-Campos, M.; Chel-Guerrero, L.; Betancur-Ancona, D. Synthesis and Partial Characterization of Octenylsuccinic Starch from Phaseolus Lunatus. Food Hydrocoll. 2008, 22, 1467–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marta, H.; Cahyana, Y.; Djali, M. Densely Packed-Matrices of Heat Moisture Treated-Starch Determine the Digestion Rate Constant as Revealed by Logarithm of Slope Plots. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 58, 2237–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marta, H.; Cahyana, Y.; Bintang, S.; Soeherman, G.P.; Djali, M. Physicochemical and Pasting Properties of Corn Starch as Affected by Hydrothermal Modification by Various Methods. Int. J. Food Prop. 2022, 25, 792–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marta, H.; Hasya, H.N.; Lestari, Z.I.; Cahyana, Y.; Arifin, H.R.; Nurhasanah, S. Study of Changes in Crystallinity and Functional Properties of Modified Sago Starch (Metroxylon Sp.) Using Physical and Chemical Treatment. Polymers 2022, 14, 4845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ačkar, Đ.; Babić, J.; Šubarić, D.; Kopjar, M.; Miličević, B. Isolation of Starch from Two Wheat Varieties and Their Modification with Epichlorohydrin. Carbohydr. Polym. 2010, 81, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, W.; Wang, H.; Ye, Q. Effects of a Highly Resistant Rice Starch and Pre-Incubation Temperatures on the Physicochemical Properties of Surimi Gel from Grass Carp (Ctenopharyn Odon Idellus). Food Chem. 2014, 145, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Fu, X.; He, X.; Luo, F.; Gao, Q.; Yu, S. Effect of Ultrasonic Treatment on the Physicochemical Properties of Maize Starches Differing in Amylose Content. Starch - Stärke 2008, 60, 646–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyothi, A.N.; Sheriff, J.T.; Sajeev, M.S. Physical and Functional Properties of Arrowroot Starch Extrudates. J. Food Sci. 2009, 74, E97–E104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adebowale, K.O.; Olu-Owolabi, B.I.; Olawumi, E.k.; Lawal, O.S. Functional Properties of Native, Physically and Chemically Modified Breadfruit (Artocarpus Artilis) Starch. Ind Crops Prod 2005, 21, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, F.; Gidley, M.; Flanagan, B. Infrared Spectroscopy as a Tool to Characterise Starch Ordered Structure- a Joint Ftir-Atr, Nmr, Xrd and Dsc Study. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Rubio, A.; Flanagan, B.M.; Gilbert, E.P.; Gidley, M.J. A Novel Approach for Calculating Starch Crystallinity and Its Correlation with Double Helix Content: A Combined Xrd and Nmr Study. Biopolymers 2008, 89, 761–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villas-Boas, F.; Franco, C.M.L. Effect of Bacterial Β-Amylase and Fungal A-Amylase on the Digestibility and Structural Characteristics of Potato and Arrowroot Starches. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 52, 795–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, G.F.; Fakhouri, F.M.; de Oliveira, R.A. Extraction and Characterization of Arrowroot (Maranta Arundinaceae L.) Starch and Its Application in Edible Films. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 186, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marta, H.; Cahyana, Y.; Djali, M.; Arcot, J.; Tensiska, T. A Comparative Study on the Physicochemical and Pasting Properties of Starch and Flour from Different Banana (Musa Spp.) Cultivars Grown in Indonesia. Int. J. Food Prop. 2019, 22, 1562–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handarini, K.; Hamdani, J.S.; Cahyana, Y.; Setiasih, I.S. Gaseous Ozonation at Low Concentration Modifies Functional, Pasting, and Thermal Properties of Arrowroot Starch (Maranta Arundinaceae). Starch - Stärke 2020, 72, 1900106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso, A.G.; del Mastro, N.L. Physicochemical Characterization of Irradiated Arrowroot Starch. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2019, 158, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharti, I.; Singh, S.; Saxena, D.C. Exploring the Influence of Heat Moisture Treatment on Physicochemical, Pasting, Structural and Morphological Properties of Mango Kernel Starches from Indian Cultivars. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 110, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, B.; Pinto, V.Z.; Vanier, N.L.; Zavareze, E.d.R.; Colussi, R.; Evangelho, J.A.d.; Gutkoski, L.C.; Dias, A.R.G. Effect of Single and Dual Heat–Moisture Treatments on Properties of Rice, Cassava, and Pinhao Starches. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 98, 1578–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, Q.; Xu, X.; Qi, L.; Dong, Z.; Luo, Z.; Lu, X.; Peng, X. Structural Changes of Waxy and Normal Maize Starches Modified by Heat Moisture Treatment and Their Relationship with Starch Digestibility. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 177, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, R.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Li, G.; Shan, Y.; Ding, S. Effects of Heat-Moisture and Acid Treatments on the Structural, Physicochemical, and in Vitro Digestibility Properties of Lily Starch. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 148, 956–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, R. The Impact of Heat-Moisture Treatment on Molecular Structures and Properties of Starches Isolated from Different Botanical Sources. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2010, 50, 835–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, S.I.; Singh, S.; Saxena, D.C. Effect of Heat-Moisture and Acid Treatment on Physicochemical, Pasting, Thermal and Morphological Properties of Horse Chestnut (Aesculus Indica) Starch. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 57, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.-Q.; Song, X.-Y.; Ruan, H.; Chen, F. Octenyl Succinic Anhydride Modified Early Indica Rice Starches Differing in Amylose Content. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 2775–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Ma, M.; Xu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Sui, Z.; Corke, H. Octenyl Succinic Anhydride Modification Alters Blending Effects of Waxy Potato and Waxy Rice Starches. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 190, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Zhou, C.-w.; Wang, R.-z.; Yang, L.; Du, S.-s.; Wang, F.-p.; Ruan, H.; He, G.-q. Lipase-Coupling Esterification of Starch with Octenyl Succinic Anhydride. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 87, 2137–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhosale, R.; Singhal, R. Effect of Octenylsuccinylation on Physicochemical and Functional Properties of Waxy Maize and Amaranth Starches. Carbohydr. Polym. 2007, 68, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, J.H.; Kim, H.R.; Kim, Y.; Lee, J.S.; Park, H.J.; Moon, T.W.; Lee, C.J. Structural Characteristics of Low-Digestible Sweet Potato Starch Prepared by Heat-Moisture Treatment. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 151, 1049–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, Z.; Yao, T.; Zhao, Y.; Ye, X.; Kong, X.; Ai, L. Effects of Heat–Moisture Treatment Reaction Conditions on the Physicochemical and Structural Properties of Maize Starch: Moisture and Length of Heating. Food Chem. 2015, 173, 1125–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.Y.; Ma, J.-G.; Kim, J.; Lee, D.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Kwon, D.-J.; Kim, J.-Y. Effect of Dual Modification of Hmt and Crosslinking on Physicochemical Properties and Digestibility of Waxy Maize Starch. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 75, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- No, J.; Mun, S.; Shin, M. Properties and Digestibility of Octenyl Succinic Anhydride-Modified Japonica-Type Waxy and Non-Waxy Rice Starches. Molecules 2019, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molavi, H.; Razavi, S.M.A. Dynamic Rheological and Textural Properties of Acorn (Quercus Brantii Lindle.) Starch: Effect of Single and Dual Hydrothermal Modifications. Starch - Stärke 2018, 70, 1800086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, L.; Singh, J.; McCarthy, O.; Singh, H. Physico-Chemical, Rheological and Structural Properties of Fractionated Potato Starches. J. Food Eng. 2007, 82, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Gao, Q. Effect of Dual Modification with Ultrasonic and Electric Field on Potato Starch. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 150, 637–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedi, E.; Pourmohammadi, K.; Abbasi, S. Dual-Frequency Ultrasound for Ultrasonic-Assisted Esterification. Food Sci Nutr 2019, 7, 2613–2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colussi, R.; Halal, S.; Zanella Pinto, V.; Bartz, J.; Gutkoski, L.; Zavareze, E.; Dias, A. Acetylation of Rice Starch in an Aqueous Medium for Use in Food. Lebensmittel-Wissenschaft und-Technologie 2015, 1, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczesniak, A.S. Texture Is a Sensory Property. Food Qual Prefer. 2002, 13, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, P.N.; Singhal, R.S. Effect of Succinylation on the Corn and Amaranth Starch Pastes. Carbohydr. Polym. 2002, 48, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.J.; Olawuyi, I.F.; Lee, W.Y. Characteristics of Low-Fat Mayonnaise Using Different Modified Arrowroot Starches as Fat Replacer. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 153, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jyothi, A.N.; Sajeev, M.S.; Sreekumar, J.N. Hydrothermal Modifications of Tropical Tuber Starches. 1. Effect of Heat-Moisture Treatment on the Physicochemical, Rheological and Gelatinization Characteristics. Starch - Stärke 2010, 62, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shogren, R.L.; Viswanathan, A.; Felker, F.; Gross, R.A. Distribution of Octenyl Succinate Groups in Octenyl Succinic Anhydride Modified Waxy Maize Starch. Starch - Stärke 2000, 52, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ačkar, Đ.; Babić, J.; Jozinović, A.; Miličević, B.; Jokić, S.; Miličević, R.; Rajič, M.; Šubarić, D. Starch Modification by Organic Acids and Their Derivatives: A Review. Molecules 2015, 20, 19554–19570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehboob, S.; Ali, T.M.; Alam, F.; Hasnain, A. Dual Modification of Native White Sorghum (Sorghum Bicolor) Starch Via Acid Hydrolysis and Succinylation. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 64, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biliaderis, C.G. , BeMiller, J.; Whistler, R., Eds. Academic Press: San Diego, 2009; pp.293-372.Starch. In Starch (Third Edition), BeMiller, J.; Whistler, R., Eds. Academic Press: San Diego, 2009; Whistler, R., Eds. Academic Press: San Diego, 2009; pp. 293–372. [Google Scholar]

- Sindhu, R.; Devi, A.; Khatkar, B. Physicochemical, Thermal and Structural Properties of Heat Moisture Treated Common Buckwheat Starches. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Singh, A.K.; Yadav, D.N.; Arora, S.; Vishwakarma, R.K. Impact of Octenyl Succinylation on Rheological, Pasting, Thermal and Physicochemical Properties of Pearl Millet (Pennisetum Typhoides) Starch. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 73, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-F.; Kaur, L.; Singh, J. Chapter 7 - Chemical Modification of Starch. In Starch in Food (Second Edition); Sjöö, M., Nilsson, L., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing, 2018; pp. 283–321. [Google Scholar]

- Charles, A.L.; Cato, K.; Huang, T.-C.; Chang, Y.-H.; Ciou, J.-Y.; Chang, J.-S.; Lin, H.-H. Functional Properties of Arrowroot Starch in Cassava and Sweet Potato Composite Starches. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 53, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, E.; Lares, M. Chemical Composition, Mineral Profile, and Functional Properties of Canna (Canna Edulis) and Arrowroot (Maranta Spp.) Starches. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition 2005, 60, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, B.S.; Guleria, P.; Yadav, R.B. Hydrothermal Modification of Indian Water Chestnut Starch: Influence of Heat-Moisture Treatment and Annealing on the Physicochemical, Gelatinization and Pasting Characteristics. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 53, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutlu, N.; Pandiselvam, R.; Kamiloglu, A.; Saka, I.; Sruthi, N.U.; Kothakota, A.; Socol, C.T.; Maerescu, C.M. Impact of Ultrasonication Applications on Color Profile of Foods. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022, 89, 106109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).