1. Introduction

Aerobic spore formers are mainly Gram-positive bacteria of the

Bacillus genus sharing the ability to form metabolically quiescent (endo)spores in response to environmental conditions that do not allow cell growth [

1]. For these organisms spore formation is a survival strategy since spores are extremely stable cells, resistant to harsh conditions such as high temperatures, low pH, absence of water and nutrients, presence of lytic enzymes, toxic chemicals and UV irradiations [

1]. In response to the renewed presence of water, nutrients and of favorable environmental conditions, spores germinate, originating vegetative cells able to grow and eventually to sporulate again [

2].

Also due to their resistance properties,

Bacillus spores are ubiquitous in nature and can be isolated from common and extreme environments [

1,

2].

Bacillus spores are also abundantly present in the gut of animals, where they enter as contaminants of food and water and safely transit the gastric barrier. In the intestine some of the ingested spores germinate [

3,

4,

5,

6], the germination-derived cells grow and temporarily colonize that niche, before re-sporulating in the terminal part of the intestine and leaving the body as spores [

7,

8].

Ingested spores of various

Bacillus species have health beneficial effects [

3,

5] and provide protection against bacterial [

9] and viral infections [

10]. Such probiotic effects have been ascribed to various mechanisms, including the promotion of the development of the Gut-Associated Lymphoid Tissue (GALT) [

11], the induction of the production of cytokines in mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN) (IL-1, IL-5, IL-6, IFN- g and TNF-a) and spleen (IFN-γ and TNF-a) [

12], the upregulation of the expression of the Toll-like receptors TLR2 and TLR4 [

13], the protection of human intestinal cells from oxidative stress [

14] by inducing the nuclear translocation of the transcriptional factor Nrf-2 that, in turn, activates stress-response genes [

15]. More recently,

B. subtilis cells have been shown to have regulatory effects on epithelial differentiation by inhibiting the Notch pathway and, as a consequence, shifting differentiation toward a secretory cell fate [

16]. Such Toll-like receptor 2-dependent effect causes an increased number of Paneth and goblet cells in the intestine that in turn results in the production of antimicrobial peptides [

16]. An additional mechanism by which spores exert their beneficial effects is the modulation of the microbial composition of the gut, exerted by favoring the prevalence of other potentially beneficial bacteria such as

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii [

17],

Akkermansia muciniphila and

Bifidobacterium spp. [

18].

In the intestine germination-derived cells produce a variety of metabolites that mediate the interaction with the host intestinal and immune cells. Examples of such beneficial molecules produced by several

Bacillus strains are enzymes, such as the NattoKinase (NK), a serine protease characterized by a potent thrombolytic activity and proposed for the treatment of multiple cardiovascular diseases [

19], and the Glutamic Acid Decarboxylase (GAD), able to catalyze the synthesis of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), the most common inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system that also regulates cardiovascular functions such as blood pressure and heart rate [

20]. In addition, peptides and lipopeptides with antimicrobial activity [

21,

22] and quorum-sensing peptides [

23] are also produced by several

Bacillus strains. An example is the Competence and Sporulation Factor (CSF), a quorum sensing pentapeptide secreted by

B. subtilis cells that is also recognized by human epithelial cells in which it induces the synthesis of the heat-shock (HS) proteins [

23]. In a murine model, CSF prevents oxidant-induced intestinal epithelial injuries and loss of barrier function, exerting a cytoprotective activity [

24]. CSF is only produced by members of the

B. subtilis species but other species produce different peptides (CSF-like) similarly able to induce the synthesis of the heat-shock (HS) proteins in human cells

in vitro [

25]. More recently, CSF has been recognized as a key factor for the anti-neurodegenerative activity of

B. subtilis in the model organism

Caenorabditis elegans [

26].

B. subtilis strains able to produce biofilm, CSF and nitric oxide (NO) were shown to extend the longevity of

C. elegans downregulating the insulin-like signaling system, thus opening the possibility that ingested spores of

B. subtilis could contribute to delay the development of age-related diseases [

27,

28].

In this work, several Bacillus strains were isolated from intestinal samples of healthy children not under probiotic or antibiotic treatment. Four of these strains that were not hemolytic and not resistant to antibiotics, were assigned to the B. velenzensis (MV4 and MV11), B. subtilis (MV24) and Priestia megaterium (formerly B. megaterium) (MV30) species and characterized at the genomic and physiological level.

2. Results

2.1. Preliminary characterization and selection of strains with probiotic potentials

Fecal samples of healthy children (Methods) were collected, heat-treated as previously reported [

29], plated on Difco Sporulation (DS) medium and incubated aerobically at 37°C for 24-48 hours. Putative siblings, colonies of apparently identical morphology originated from the same intestinal sample, were eliminated. All colonies that did not show a free spore or a forming spore still within a sporagium were also eliminated.

A total of 32 aerobic spore formers (MV2-MV33) were selected for further characterization. Cells of all 32 strains showed a rod shaped morphology under the light microscope and were able to form phase bright, ellipsoidal endospores localized in central or sub-terminal position. Only strain MV19 formed apparently unusual spores that have been described elsewhere [

30]. In addition to spores, strains MV19 [

30], MV21, MV26 and MV30 formed multiple parasporal granules (possibly inclusion bodies) (

Supplementary Materials Figure S1).

All 32 isolates were screened for the hemolytic activity on blood agar plates. Isolates appearing greenish were considered able to oxidize the iron of the hemoglobin molecules within red blood cells and indicated as alpha-hemolytic; isolates forming a clear halo around their colonies were considered able to lyse red blood cells and indicated as beta-hemolytic; isolates that did not appear greenish and did not form any halo were considered not hemolytic and indicated as gamma-hemolytic. As shown in

Supplementary Materials Table S1, 10 out of 32 isolates were not hemolytic.

The ten not hemolytic strains were analyzed for their resistance to the panel of eight antibiotics indicated as relevant for members of the

Bacillus genus by the European Food Safety Authority, (EFSA, 2012). As shown in

Table 1, four of the ten considered strains (MV4, MV11, MV24 and MV30) were sensitive to all tested antibiotics, four (MV6, MV14, MV20 and MV26) were resistant to a single antibiotic and the remaining two strains were resistant to three (MV15) and four (MV17) antibiotics over the EFSA breakpoint values, respectively. The four strains sensitive to all antibiotics (MV4, MV11, MV24 and MV30) were considered as potential probiotics and used for further characterization.

2.2. Species assignment and phylogenetic analysis

The four isolates were used to extract total DNA and the genomic sequences obtained with a coverage of about 30x. The genomes are approximately 4.0 Mbp long for MV4, MV11 and MV24, and about 5.8 Mbp for MV30 (

Table 2). The total number of ORFs was 3,860, 3,956 and 4,380 for MV4, MV11 and MV24 respectively, and higher for MV30 (6,003) (

Table 2). No plasmid sequences were detected in any of the strains (not shown). All genome sequences were deposited in the GenBank database (Methods).

Based on the analysis of the sequence of the 16S RNA genes MV4 and MV11 were tentatively considered as belonging to the

B. velezensis species while MV24 and MV30 to the

B. subtilis and

Priestia megaterium (formerly

Bacillus megaterium) species, respectively. The Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) of the four genomes was determined against the genome of a type strain of each of the putative species and confirmed the species assignment suggested by the 16S RNA gene analysis (

Table 3).

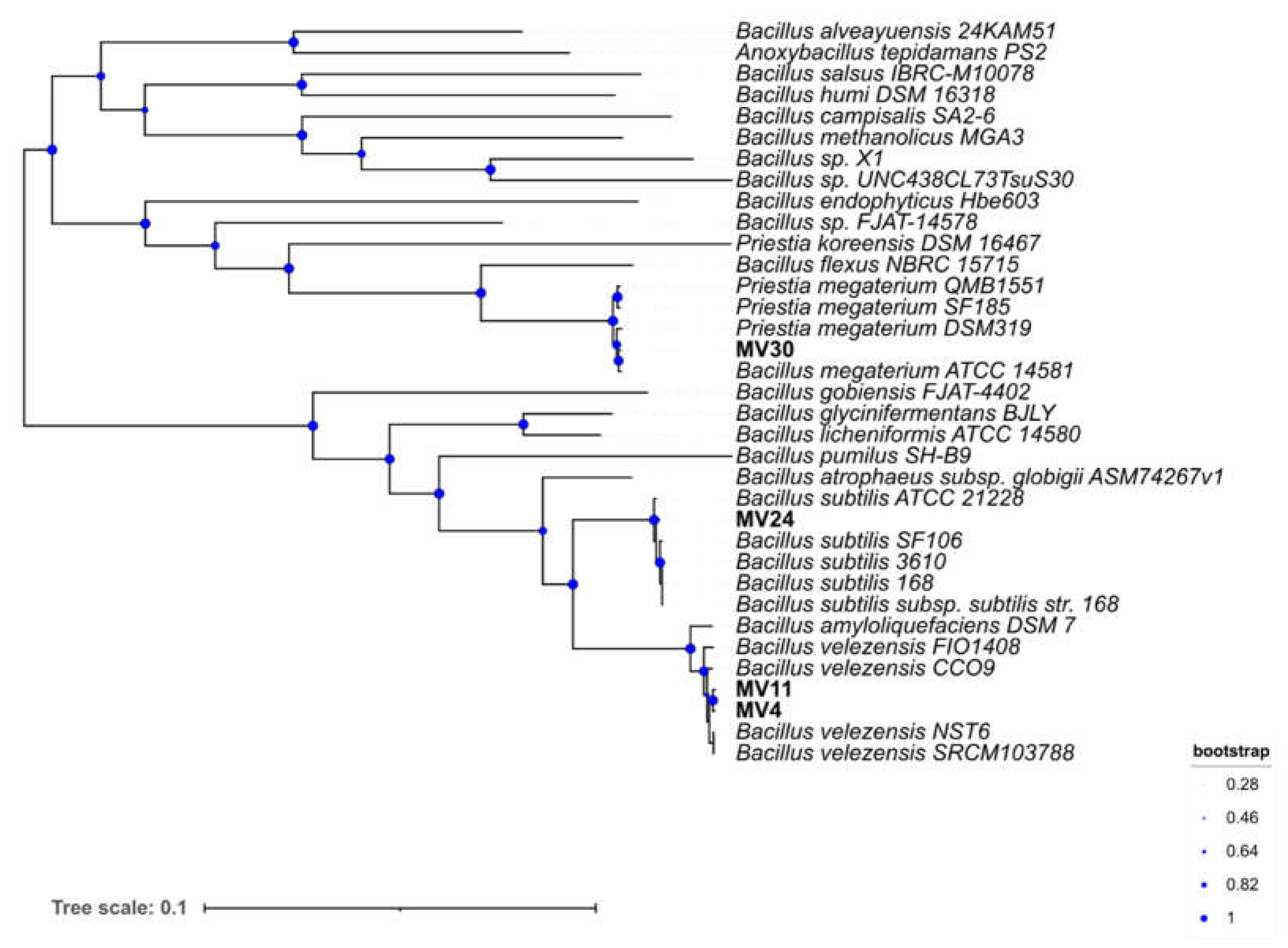

The phylogeny of the four strains was further characterized by comparing 49 universally conserved genes (Methods) with those of several other strains of related species. A phylogenetic tree was generated by Insert Genome into Species Tree app in KBase (

Figure 1).

2.3. Genome analyses

MV4, MV11, MV24 and MV30 genomes were screened for the presence of toxin genes previously found in various other

Bacillus strains [

31,

32]. As reported in

Supplementary Materials Table S2, homologs of most of the genes coding for virulence factors were not found in MV4, MV11, MV24 or MV30. Homologs of the

hlyIII gene, coding for the channel-forming protein Hemolysin III, were found in all four genomes as well as in the non-pathogenic strains

B. clausii KSM-K16 and

B. subtilis 168 (

Supplementary Materials Table S2). The two

B. velenzensis strains and MV30 also contained homologs of the

cysC gene coding for an adenylyl-sulfate-kinase similar to the

Pseudomonas adenylyl-sulfate-kinase phytotoxin (

Supplementary Materials Table S2). Only the genome of MV30 contains two homologs of the

cylR2 gene, coding for a DNA binding protein of

Enterococcus acting as a repressor of the cytolysin operon (

Supplementary Materials Table S2).

The functional annotation of the four genomes was performed by using the EggNOG (evolutionary genealogy of genes: Non-supervised Orthologous Groups) database, a public resource classification database able to provide Cluster Orthologous Groups (COGs) of proteins with functional annotations (

Supplementary Materials Figure S2). For all four strains the majority of the annotated genes were classified into the “Unknown Category” (S category in

Supplementary Materials Figure S2). According to this annotation system, the next most represented classes for all four strains were “amino acid transport and metabolism”, “transcription” and “carbohydrate transport and metabolism” (respectively E, K and G categories in

Supplementary Materials Figure S2).

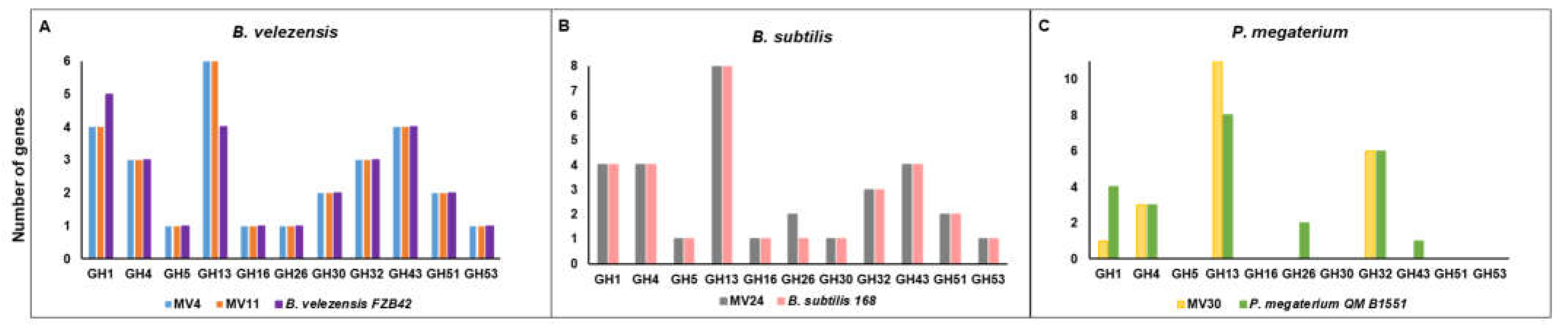

The genomes of the four isolates were also annotated using the Carbohydrate-Active enZymes (CAZymes) database in comparison with the genome of a reference strain of the respective species. MV4 and MV11 showed a number of genes putatively coding for glycosyl-hydrolase (GH) and a total number of CAZymes bigger than a reference strain of

B. velenzensis (

Table 4). MV24 and MV30 showed, respectively, a slightly bigger and smaller number of CAZymes than their reference strains (

Table 4). The GH category contains various hydrolases that act on the glycosidic bond and is divided into families. Some families such as GH1, GH4, GH5, GH16 and GH32 contain enzymes involved in the degradation of cellulose, starch and sucrose while the GH26, GH30, GH43, GH51 and GH53 contain enzymes specialized in the degradation of hemicellulose, xylan and cellobiose [

33].

Figure 2 reports the abundance of the GH families mainly involved in the degradation of plant polysaccharides found in the four MV genomes. With respect to a reference strain of the same species, MV4, MV11 and MV30 contain more genes for the GH13 family and less genes for the GH1 family, respectively containing enzymes specialized in the degradation of starch or monosaccharides (

Figure 2).

MV30 also does not contain GH26 and GH43, present in the

P. megaterium reference strain and coding for enzymes involved in the degradation of mannans or arabinose/xylose, respectively. The GH profile of the

B. subtilis strain MV24 was very similar to that of the reference strain with the only difference in the number of GH26 (degradation of mannans) higher in MV24 than in

B. subtilis 168 (

Figure 2).

The genome sequences of the four strains were also analyzed to search for homologs of nattokinase (EC 3.4.21.62), using as query the protein sequence found in Bacillus subtilis subsp. natto BEST195 (accession No. BAI84580.1). Homologs were present in MV4 (85.86% identity, MV4_3335), MV11 (86.13%, Contig_6_158) and MV24 (99.21%, MV24_0328), while no homologs of the nattokinase coding gene were present in the MV30.

The presence of homologs of the glutamate decarboxylase (GAD), an enzyme that converts glutamate to γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), was also investigated and a homolog with an identity of 77.9% with the GAD of other Bacillus species (WP_049107856.1) was found only in the MV30 genome (MV30_2943).

2.4. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities

The four genomes were analyzed to identify genes coding for antimicrobials and antioxidants. The antiSMASH

(Antibiotics

& Secondary Metabolite Analysis Shell

) database was used to assess the presence of genes associated with the synthesis of antimicrobials and secondary metabolites. The genome of the two

B. velenzensis isolates contain seven (MV4) and five (MV11) clusters with a cut-off similarity value of at least 80% (

Supplementary Materials Table S3). Both strains potentially produce macrolactin H, bacillaene, fengycin, bacillibactin and bacilysin while only MV4 also codes for difficidin and surfactin (

Supplementary Materials Table S3). The genome of the

B. subtilis strain MV24 codes for bacillibactin, bacilysin, subtilosin A and fengycin while genes coding for surfactin were present but with a similarity value slightly lower than the threshold limit of 80% (

Supplementary Materials Table S3). No clusters with significant similarity were found in the genome of MV30 (

Supplementary Materials Table S3). To validate the genomic predictions on the potential production of antimicrobials, the MV strains were tested against a panel of target microorganisms by agar diffusion assay with cell-free supernatants. Consistently with the

in-silico prediction, MV30 did not show any antimicrobial activity against the target bacteria (

Table 5). The other three strains were active against

L. monocytogenes and

B. cereus while only strains of the

B. velenzensis species (MV4 and MV11) were weakly active against some other bacteria and a strain of

Candida albicans (

Table 5).

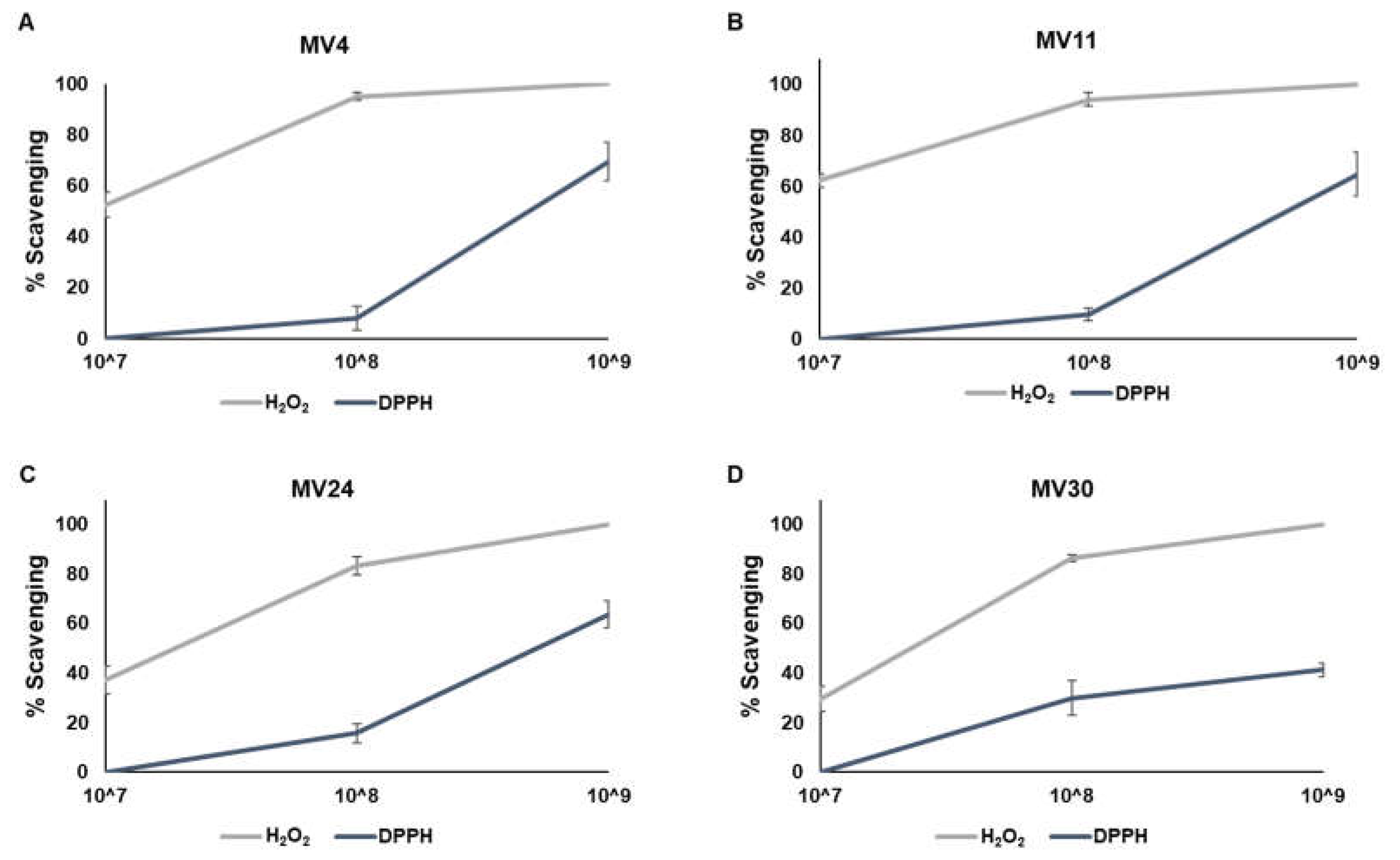

All four genomes were screened for the presence of genes coding for antioxidants. Homologs of the enzymes catalase (CAT; EC:1.11.1.6) and superoxide dismutase (SOD; EC:1.15.1.1) were present in all four genomes. In particular, MV4, MV11 and MV24 contain three CAT (MV4_0856, MV4_0864, MV4_1319 in MV4; Contig_4_193; Contig_4_217 Contig_6_12 in MV11; MV24_3061, MV24_0468, MV24_1926 in MV24) and three SOD (MV4_0856, MV4_1319, MV4_0864 in MV4; 1_870, 2_130, 1_878 in MV11; MV24_2302, MV24_1406, MV24_2295) homologs. MV30 genome only contains one homolog of each enzyme (CAT:MV30_1299 and SOD:MV30_1877).

The four strains were then tested for their antioxidant activity. Vegetative cells (collected after 24 hours of aerobic growth at 37°C) (Methods) were tested for the scavenging activity against hydrogen peroxidase (H

2O

2) or free radicals (by α,α-diphenyl-β-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) method), as previously reported [

14]. As shown in

Figure 3, the H

2O

2-scavenging activity was stronger than the anti-free radicals activity with between 80 and 90% of H

2O

2 elimination with 1x10

8 cells and a total H

2O

2 elimination with 1x10

9 cells of all four strains. Over 60% of free radical elimination was observed with 1x10

9 cells of MV4, MV11 and MV24 (

Figure 3A-C), while about 40% of free radicals reduction was observed with the same number of MV30 cells (

Figure 3D).

2.5. Matrix formation

In

B. subtilis, the model system for spore formers, the biofilm matrix components include secreted proteins, extracellular DNA (cDNA) and an exopolysaccharide (EPS) [

34]. The genes coding for the secreted proteins and for the EPS are clustered in the

epsA-O and

tapA-sipW-tasA operons that are controlled by the master regulators SinI-SinR and Spo0A [

34]. In

B. cereus also products of the

pur operon, coding for enzymes needed for purine biosynthesis, are required for biofilm formation [

35]. The genomes of MV4, MV11, MV24 and MV30 were analyzed for the presence of all these genes involved in matrix formation. As reported in

Supplementary Materials Table S4, all four genomes contain homologs of the

epsA-O and

tapA-sipW-tasA operons, of their regulators and of the

pur operon.

All four strains were analyzed for their ability to produce biofilm in different media in comparison with a

B. subtilis laboratory collection strain producing minimal amounts of biofilm (PY79) and a natural strain of the same species known to produce large amounts of biofilm (NCIB3610) [

36]. In our experimental conditions (aerobic growth at 37 °C) all four strains produced different amounts of matrix in different media (

Figure 4). The two

B. velenzensis strains produced a low amount of biofilm in rich (LB) medium and higher amounts in sporulation-inducing (DSM) or minimal (LB) media (

Figure 4). Similarly, to the reference strain of

B. subtilis NCBI3610,

B. subtilis MV24 produced the highest amount of matrix in minimal (S7) medium, however while the amount of biofilm produced by the two strains was almost identical in LB and DSM media, in minimal medium MV24 produced significantly more biofilm than NCIB3610 (

Figure 4). MV30 showed a different pattern of biofilm formation with the highest amount produced in LB medium and the lowest in the sporulation-inducing medium (

Figure 4).

2.6. Production of CSF or CSF-like peptides

Several

Bacillus strains produce and secrete peptides sensed by human epithelial cells, such as the CSF pentapeptide of

B. subtilis able to induce a cytoprotective heat-shock response [

23,

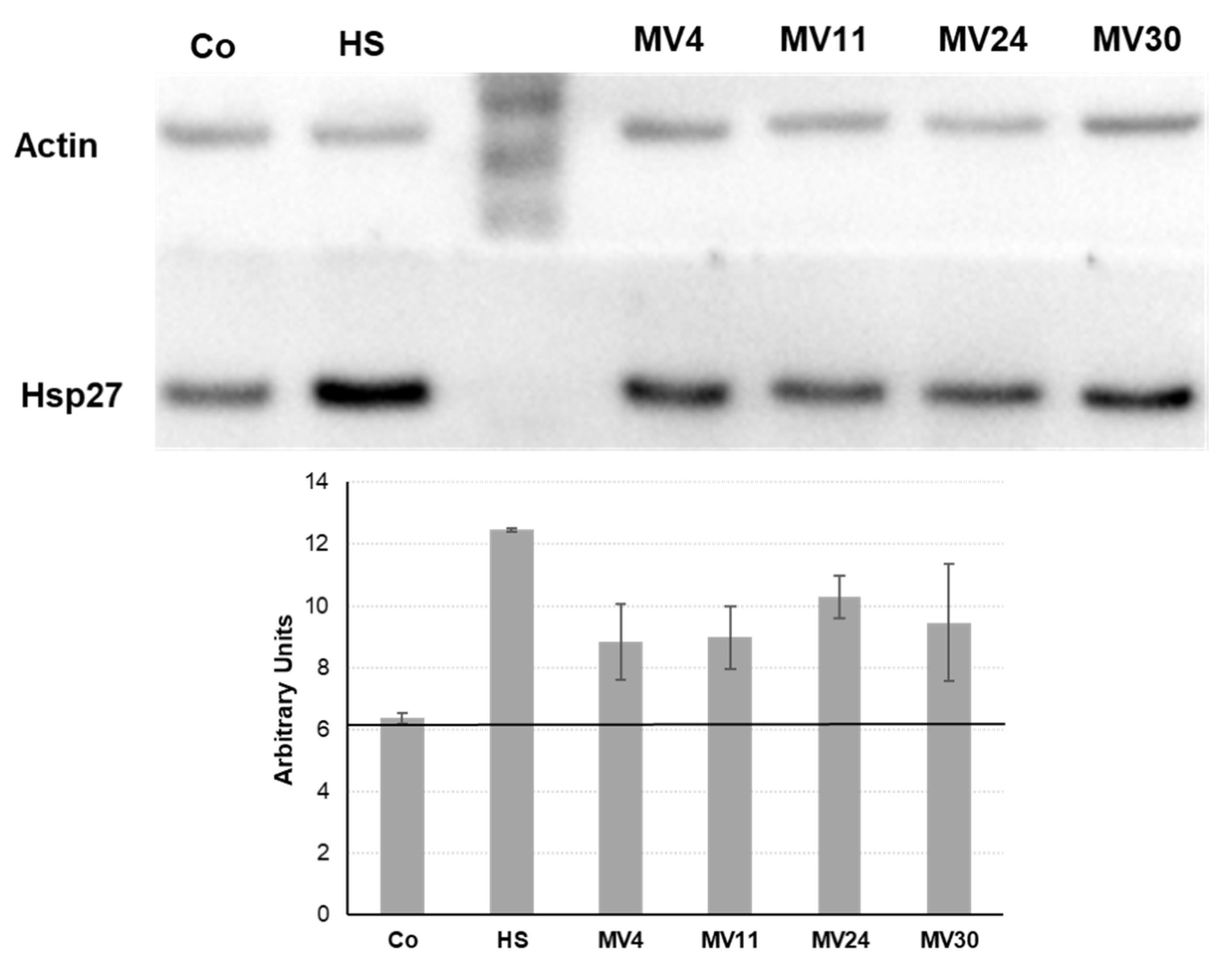

25]. The four MV strains were evaluated for their ability to induce a heat-shock response in human epithelial cells. HT-29 colon carcinoma cells were either heat-shocked (

30 min at 45 °C) or treated with 20% vol/vol of cell free conditioned medium (CM) from the four MV strains and Hps27 induction evaluated by western blotting with anti-Hsp27 antibody (

Figure 5).

After normalization of the intensity of the obtained signals with those of the β-actin extracted from the same cells, the levels of Hsp27 after the treatment with the CM of each of the four strains appeared higher than the threshold level obtained with uninduced HT-29 cells (

Figure 5). Although the experiment was not quantitative, it suggested that the CM of all four MV strains was able to induce the expression of the heat-shock protein Hsp27 in the HT-29 cells and, therefore, that all four strains secreted CSF or CSF-like peptides.

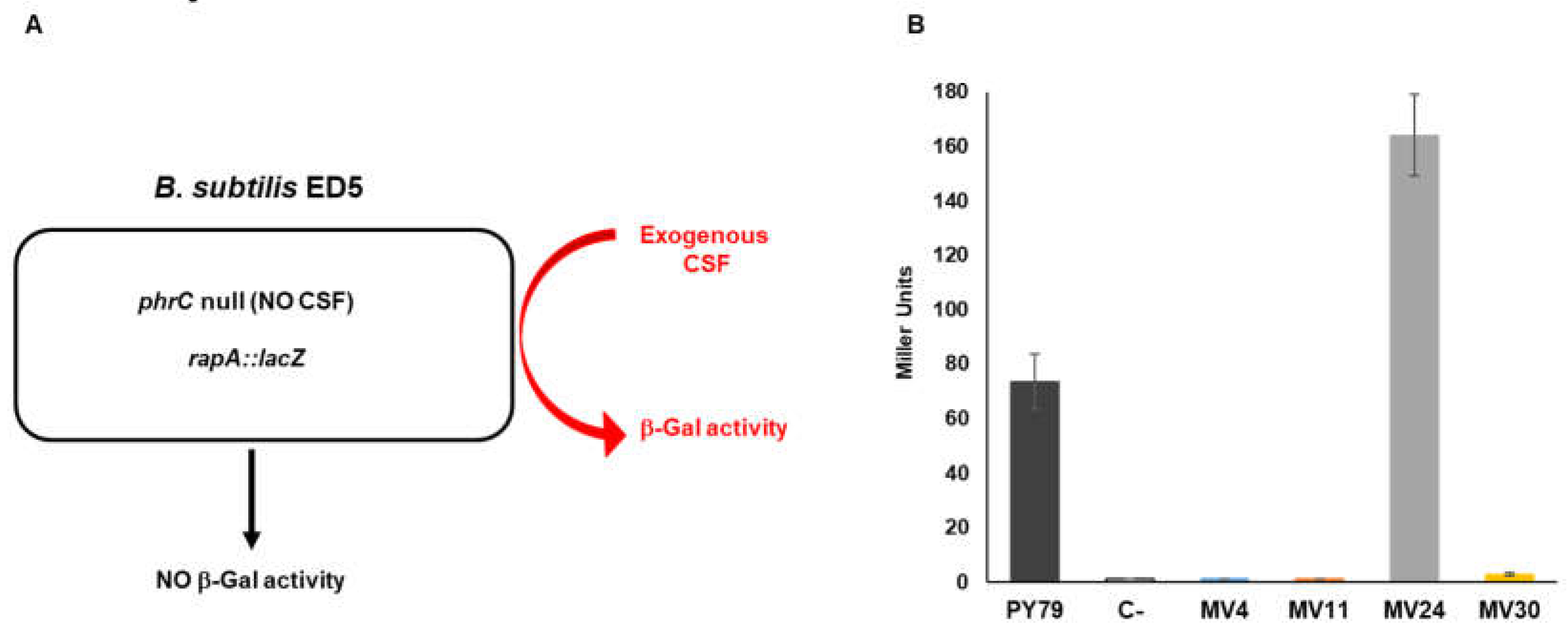

A quantitative evaluation of the amount of secreted CSF was obtained by using a recombinant strain of

B. subtilis carrying a null mutation in the gene coding for CSF (

phrC) and a gene fusion between the promoter of the CSF-controlled gene

rapA and the coding part of the reporter gene

lacZ of

Escherichia coli [

25]. The recombinant strain ED5, not producing CSF, does not express the gene fusion but responds to exogenous CSF producing β-galactosidase (

Figure 6A) [

25]. Cells of ED5 growing in LB medium were supplemented (20% vol/vol) with the CM of the four MV and control strains, and tested for β-galactosidase production, as previously reported [

25]. The

B. subtilis isolate MV24 induced β-galactosidase at levels about two-fold higher than the laboratory collection strain of the same species (PY79) (

Figure 6B). As expected, the three strains not belonging to the

B. subtilis species did not induce β-galactosidase, suggesting that they produce CSF-like peptides able to induce a heat-shock response in epithelial cells [

25] (

Figure 5) but unable to activate

rapA transcription in

B. subtilis (

Figure 6B).

3. Discussion

Four aerobic spore formers strains isolated from intestinal samples of healthy children were selected as potentially probiotics for being not hemolytic and sensitive to all antibiotics indicated as relevant for spore formers by the EFSA. The four strains were unambiguously assigned to species that are in the Qualified Presumption of Safety (QPS) list of the EFSA (

https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/topics/topic/qualified-presumption-safety-qps) and are marketed as probiotics for human or animal use [

3,

6], therefore indicating that they could be considered as safe for human use. This assumption is supported by the

in silico observation that the four MV genomes do not carry putative genes coding for known

Bacillus toxins. Indeed, the only gene present in all four genomes coding for a putative toxin is the

hlyIII gene, common to pathogenic and non-pathogenic bacteria. The product of

hlyIII was, however, not sufficient to cause an alpha- or a beta-hemolytic phenotype to the four MV strains. A gene coding for a putative phytotoxin,

cysC, is carried by MV4, MV11 and MV30 while only the latter strain contains the

cylR2 gene, a homolog of a transcriptional repressor of a cytolysin operon of

Enterococcus.

All four strains formed biofilm and showed antioxidant activity

in vitro. In addition to these potentially useful properties, MV4, MV11 and MV30 have a gene coding for a nattokinase (NK) homolog while MV30 has a gene coding for the enzyme glutamate decarboxylase (GAD), able to convert glutamate into g-aminobutyric acid (GABA). NK is a serine-protease of the subtilisin family that when orally ingested exhibits fibrinolytic, antithrombotic and antihypertensive effects [

37]. GABA is an inhibitory neurotransmitter that improves various physiological illnesses, including diabetes, hypertension, and depression in humans [

38]. Therefore, the potential to produce NK and/or GABA is considered a relevant property for a potential probiotic strain.

The four MV strains considered in this study also produced and secreted CSF (MV24) or CSF-like (MV4, MV11 and MV30) peptides. In addition to inducing anti-inflammatory and cytoprotective responses both

in vitro and

in vivo [

23,

24], these molecules have a role in the anti-neurodegenerative activity of

B. subtilis in the model organism

C. elegans [

26,

27,

28]. Ingested spores of strains producing such molecules could have beneficial effects for the treatment of inflammatory and age-related neurodegenerative diseases.

MV4, MV11, MV24 and MV30 strains do not pose safety concerns and have beneficial properties, therefore can be considered for in vivo experiments aimed at testing their role as probiotics for human use.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacterial isolation and characterization

Fecal samples of healthy children (from 10 months to 10 years old) that had not been under antibiotic or probiotic treatment in the previous three months were collected and about 1 g of feces homogenized in sterile Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and heat-treated at 80 °C for 20 minutes. The samples were, then, serially diluted and plated on Difco Sporulation Medium (DSM, for 1L: 8 g/L Nutrient Brdfr4eoth, 1 g/L KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 1 mM Ca(NO3)2, 10 μM MnCl2, 1 μM FeSO4, Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) and incubated overnight at 37 °C. The colonies were selected and isolated as previously described [

29]. All isolates were tested for hemolytic activity by spotting 10µL of growing cells on Columbia Agar plates supplemented with 5% defibrinated horse blood (ThermoScientific) and, after 24 hours of incubation at 37 °C, the clear halo around the colonies indicated a positive result. The non-hemolytic strains were then tested for their antibiotic susceptibility by plating 0.5 McFarland of bacteria on LB agar plates (for 1L: 10 g/L Bacto-Tryptone, 5/L g Bacto yeast extract, 10 g/L NaCl, pH 7.0). Antibiotic-impregnated MIC test strips (Liofilchem®) were then placed on the plates and incubated overnight at 37 °C. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was measured at the intersection of the inhibition halo and the antibiotic strip. The strains were indicated as resistant (R) if the antibiotic concentration exceeded the threshold level set by the EFSA for

Bacillus strains [

39].

4.2. Whole-Genome Sequencing and Bioinformatic Analysis

Bacterial genomic DNA was extracted from exponentially growing cells as previously reported [

40]. Genome sequencing of MV4, MV11, MV24 and MV30 was performed with Illumina MiSeq Sequencing System by GenProbio (Parma, Italy). Genome assemblies were performed with SPAdes v3.14.0 by means of MEGAnnotator pipeline [

41]. The genomes of MV4, MV11, MV24 and MV30 have been deposited in GenBank as BioProject numbers

PRJNA977871, PRJNA977867, PRJNA977868, PRJNA977866 and accession numbers CP127102, JASNWD000000000, JASPFH000000000, JASPFG000000000, respectively. For phylogenetic analyses all genomic sequences were imported into the KBase system to create a genome set that subsequently was employed to build the tree, using Insert Genome Into SpeciesTree – v2.2.0. The phylogenomic trees were visualized on the Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL, platform v6). Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) values between the sequenced genomes and the closest bacteria were obtained using Ezbiocloud tool (

https://www.ezbiocloud.net/tools/ani).

For the detection of toxin-associated genes, the genome of the strains was analyzed using the VF analyzer pipeline [

42] as described above [

29].

The presence of homologs of nattokinase and glutamate decarboxylase was investigated in aminoacid sequences of MV strains using protein BLAST alignment (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi?PAGE=Proteins).

Secondary metabolite biosynthesis gene clusters were searched for using the web-based genome mining tool antiSMASH (http://antismash.secondarymetabolites.org).

Functional annotations of MV genomes were obtained using EggNOG-mapper v2 (

http://eggnog-mapper.embl.de). Similarly, the genomes were also scanned using the dbCAN2 server (

https://bcb.unl.edu/dbCAN2/blast.php) that integrated three tools/databases for automated CAZyme annotation [

43].

4.3. Antimicrobial and biofilm production assays

Antimicrobial activity was assessed as previously described [

43]. Briefly, 10µL of supernatant were spotted onto LB agar plates and the plates were air dried. Then 100 µL of an exponential culture of each of the target strains was mixed with 10 mL of 0.7% LB agar and plated. Fresh medium was used as a negative control. The plates were incubated overnight at 37 °C and the antimicrobial activity determined as the diameter of the inhibition halo.

Biofilm formation was tested as previously reported [

30]. Briefly, growing cells were inoculated into 24-well culture plates with three different media: LB, DSM [

44] and S7 minimal medium (for 1L: (50 mM morpholine-propane-sulfonic acid (MOPS) (adjusted to pH 7.0 with KOH), 10 mM (NH

4)

2SO

4, 5 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.0), 2 mM MgCl

2, 0.9 mM CaCl

2, 50 μM MnCl

2, 5 μM FeCl

3, 10 μM ZnCl

2, 2 μM thiamine hydrochloride, 20 mM sodium glutamate, 1% glucose, 0.1 mg/mL phenylalanine, and 0.1 mg/mL tryptophan) [

45]. The plates were incubated for 48h at 37 °C, and then biofilm production was assessed by crystal violet assay as previously described in [

46]. The experiment was performed in triplicate.

4.4. Antioxidant Activity Tests

4.4.1. Hydrogen Peroxide Scavenging assay

The hydrogen peroxide stability was measured by following absorbance at 240 nm of 1 mL of fresh hydrogen peroxide solution [50 mM Potassium Phosphate Buffer, pH 7.0; 0.036% (w/w) H

2O

2]. Quantitative determination of H

2O

2 scavenging activity of cells of MV strains was measured by the loss of absorbance at 240 nm as previously described [

14]. Briefly, 10

7, 10

8 and 10

9 cells/mL of selected strains were incubated at RT in 1 mL of 0.036% of hydrogen peroxide solution. After 30 minutes the hydrogen peroxide concentration in the supernatant was determined by measuring the absorbance at 240 nm. The percentage of peroxide removed was calculated as reported below:

H2O2 removed (%) = (1−Asample/Acontrol) × 100

4.4.2. DPPH assay

The α,α-diphenyl-β-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) free radical scavenging method was used to evaluate the potential antioxidant activity of MV strains [

14]. Different concentrations of the cells of each strain (10

7, 10

8 and 10

9 cells/mL) were incubated in a final volume of 1 mL of 50mM of citrate phosphate buffer (pH 7) containing 0.1 mM of freshly prepared DPPH (giving absorbance ≤ 1.0). The reaction was allowed to proceed for 30 min in the dark at room temperature. The DPPH free radical scavenging activity was then monitored by determining the absorbance at 515 nm and calculated according to the following equation:

DPPH radical scavenging activity (%) = (1−Asample/Acontrol) × 100

where Asample is the absorbance of the reacted mixture of DPPH with the extract sample, and Acontrol is the absorbance of the DPPH solution.

4.5. Growth and treatment of HT-29 cells with bacterial conditioned medium

HT-29 cells (ATCC HTB-38), derived from colon adenocarcinoma, were grown in RPMI 1640 medium (EuroClone S.p.A.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. HT-29 cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO

2 [

44]. At 80% confluence, cells were harvested and diluted in 6-well plates to a total concentration of 5.5x106 cells per well. Bacterial conditioned medium (CM), required for the treatment of the HT-29 cells, was obtained by growing bacterial cells in minimal S7 medium, aerobically, for 16 h at 37 °C [

47]. The culture was then centrifuged (7,000 rpm for 10 min) and the supernatant (CM) was filtered through a 0.22 µm low protein binding filter (Millex, Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). The obtained CM was used for HT-29 cells treatment at a concentration of 20% v/v in complete growth medium as previously reported [

48]. After 24 h incubation of HT-29 cells with 20%CM, cells were harvested, lysed and cell extracts were prepared for Western blot analysis as described below. A heat-shock treatment (45 °C for 30 minutes) was performed prior to cell lysis for heat-shock proteins induction in HT-29 cells (not treated with CM), used as a positive control. The experiment was repeated in triplicate.

4.6. Protein extraction, SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis

Cells were scraped and harvested in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 5 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate and protease inhibitors) and the cell lysates were incubated on ice for 40 minutes followed by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 30 minutes to remove cellular debris. Protein concentration was determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad, Italy). Subsequently, 2X Laemmli buffer (SIGMA, Italy) was added, proteins were boiled at 100 °C for 5 minutes and separated on a 12% SDS-PAGE gel. Proteins were transferred (2 hours at 100V, 4 °C) to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore). The membranes were blocked in a PBS-Tween20 (0.2%) buffer, with 5% (w/v) Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA, PanReac AppliChem] and incubated with the primary antibodies anti-HSP27 and anti-β-Actin (Elabscience®), diluted 1:500 and 1:1,000 respectively, in a PBS-Tween20-2.5% BSA solution overnight at 4°C. After several washes with PBS-Tween20 buffer, the membranes were incubated with 1:7,000 anti-rabbit secondary antibody (SantaCruz) for 2 hours and then visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; GE-Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK) using horseradish peroxidase conjugated secondary antibody (Santa-Cruz Biotechnology) and analyzed using Quantity One® software from the ChemiDoc™ XRS system (Bio-Rad). Band intensity was evaluated using ImageQuant analysis. Values were normalized to the β-Actin and band intensity was measured as follows: [ Reference sample β-Actin / Treated sample β-Actin ] × Band quantity (https://www.bio-rad.com/it-it/applications-technologies/image-analysis-quantitation-for-western-blotting?ID=PQEERM9V5F6X).

4.7. β-galactosidase activity

The β-galactosidase activity was evaluated as previously described [49]. Briefly, growing cells of strain ED5 (comQ::kan phrC::cat srfA::lacZ) were supplemented with 50% (v/v) of the CM of each intestinal isolated Bacillus strain (MV4, MV11, MV24, MV30). The growth was followed at 37 °C under aerobic conditions, until the stationary phase of growth. Then, 1mL of these cultures were harvested and centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 5 min. The pellet was resuspended in 1mL of Z-buffer (0.06 M Na2HPO4, 0.04 M NaH2PO4, 0.01 M KCl, 0.001 M MgSO4 and 0.05M β-mercaptoethanol) and 10µL of toluene. Tubes were incubated at 30 °C for 20 min and vortexed every 5 minutes. The enzymatic reaction was started by adding 200µL of Ortho-nitrophenyl-β-galactoside (ONPG) solution (4 mg/mL ONPG in Z-Buffer without β-mercaptoethanol) and incubated at 30 °C. When the color was clearly yellow (A 420nm ~0.3), the reaction was stopped by adding 500µL of 1M Na2CO3 and reaction time was recorded. Tubes were then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 5 min and the assorbance at 420nm was recorded for each sample immediately. The β-galactosidase activity was expressed in Miller Units, as described in [49].

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree. The genomes were imported into the Kbase system and the phylogenetic tree constructed by using Insert Genome Into SpeciesTree - v2.2.0. Bootstrap confidence values were generated using 1,000 permutations.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree. The genomes were imported into the Kbase system and the phylogenetic tree constructed by using Insert Genome Into SpeciesTree - v2.2.0. Bootstrap confidence values were generated using 1,000 permutations.

Figure 2.

Number of predicted genes encoding cellulose/hemicellulose degradation enzymes found in the genome of MV4, MV11 (A), MV24 (B), and MV30 (C) compared to the indicated reference strains.

Figure 2.

Number of predicted genes encoding cellulose/hemicellulose degradation enzymes found in the genome of MV4, MV11 (A), MV24 (B), and MV30 (C) compared to the indicated reference strains.

Figure 3.

Evaluation of the ability of MV4 (A), MV11 (B), MV24 (C) and MV30 (D) cells to reduce hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, grey line) and the radical 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH, blue line). The assay was performed using suspensions of 107, 108 and 109 cells and was repeated in triplicate.

Figure 3.

Evaluation of the ability of MV4 (A), MV11 (B), MV24 (C) and MV30 (D) cells to reduce hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, grey line) and the radical 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH, blue line). The assay was performed using suspensions of 107, 108 and 109 cells and was repeated in triplicate.

Figure 4.

Biofilm production assay performed on the four bacterial strains in three different media: LB (blue bars), DSM (orange bars) and S7 (grey bars). The assay was performed in triplicate. B. subtilis strains NCIB3610 and PY79 were used as positive and negative controls, respectively.

Figure 4.

Biofilm production assay performed on the four bacterial strains in three different media: LB (blue bars), DSM (orange bars) and S7 (grey bars). The assay was performed in triplicate. B. subtilis strains NCIB3610 and PY79 were used as positive and negative controls, respectively.

Figure 5.

Effect of the conditioned medium (CM) of the four strains on Hsp27 production in HT-29 intestinal cells. Representative western blot performed with anti-Hsp27 antibodies (A) and a densitometric analysis obtained by the average of three different experiments (B). The band intensity of each sample was evaluated by Image Quant analysis and normalized for the β-Actin intensity of the same sample. The black continuous line indicates the uninduced level of Hsp27 in HT-29 cells.

Figure 5.

Effect of the conditioned medium (CM) of the four strains on Hsp27 production in HT-29 intestinal cells. Representative western blot performed with anti-Hsp27 antibodies (A) and a densitometric analysis obtained by the average of three different experiments (B). The band intensity of each sample was evaluated by Image Quant analysis and normalized for the β-Actin intensity of the same sample. The black continuous line indicates the uninduced level of Hsp27 in HT-29 cells.

Figure 6.

Production of CSF pentapeptide. (A) Schematic representation of the mutant strain of B. subtilis ED5 unable to produce CSF (phrC null) carrying the rapA::lacZ gene fusion. The mutant alone does not produce endogenous CSF but responds to exogenous CSF producing β-galactosidase. (B) Beta-galactosidase activity measured with ED5 cells treated with the supernatants of MV4, MV11, MV24 and MV30. Supernatants of PY79 (B. subtilis wild-type) and ED5 (isogenic phrC deletion mutant) were used as positive and negative control, respectively. The β-galactosidase is expressed in Miller Units and data are the average of three independent experiments.

Figure 6.

Production of CSF pentapeptide. (A) Schematic representation of the mutant strain of B. subtilis ED5 unable to produce CSF (phrC null) carrying the rapA::lacZ gene fusion. The mutant alone does not produce endogenous CSF but responds to exogenous CSF producing β-galactosidase. (B) Beta-galactosidase activity measured with ED5 cells treated with the supernatants of MV4, MV11, MV24 and MV30. Supernatants of PY79 (B. subtilis wild-type) and ED5 (isogenic phrC deletion mutant) were used as positive and negative control, respectively. The β-galactosidase is expressed in Miller Units and data are the average of three independent experiments.

Table 1.

Sensitivity levels to a panel of selected antibiotics.1.

Table 1.

Sensitivity levels to a panel of selected antibiotics.1.

| Strain |

Van |

Gen |

Kan |

Strep |

Ery |

Clin |

Tet |

Chl |

| MV4 |

1.500 |

0.500 |

0.750 |

8.000 |

0.094 |

0.750 |

8.000 |

1.000 |

| MV6 |

0.500 |

0.125 |

2.000 |

R2

|

0.125 |

0.190 |

1.000 |

0.250 |

| MV11 |

0.190 |

0.750 |

0.500 |

1.000 |

0.047 |

0.125 |

2.000 |

2.000 |

| MV14 |

3.000 |

0.125 |

0.750 |

8.000 |

0.250 |

4.000 |

R1

|

5.000 |

| MV15 |

0.380 |

0.250 |

R2

|

2.000 |

0.380 |

R2

|

0.250 |

R2

|

| MV17 |

0.047 |

0.500 |

R2

|

R2

|

R2

|

0.750 |

0.750 |

R2

|

| MV20 |

0.190 |

0.250 |

0.500 |

1.000 |

0.125 |

R2

|

1.000 |

0.750 |

| MV24 |

1.500 |

0.500 |

1.500 |

3.000 |

0.380 |

0.380 |

0.094 |

4.000 |

| MV26 |

0.125 |

0.047 |

0.125 |

1.000 |

0.064 |

R2

|

0.250 |

2.000 |

| MV30 |

0.125 |

0.047 |

0.190 |

8.000 |

0.064 |

4.000 |

0.500 |

1.500 |

|

EFSABreakpoints

|

4.000 |

4.000 |

8.000 |

8.000 |

4.000 |

4.000 |

8.000 |

8.000 |

Table 2.

General features of the MV4, MV11, MV24 and MV30 genomes.

Table 2.

General features of the MV4, MV11, MV24 and MV30 genomes.

| |

MV4 |

MV11 |

MV24 |

MV30 |

| Size (bp) |

3,987,695 |

4,035,847 |

4,116,400 |

5,853,282 |

| Number of contigs |

36 |

58 |

112 |

35 |

| Average Coverage |

58 |

23 |

41 |

133 |

| Number of predicted ORFs |

3,860 |

3,956 |

4,380 |

6,003 |

| Average GC (percentage) |

46.35 |

46.2 |

43.26 |

37.46 |

Table 3.

Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) (%) based on whole genome alignments.

Table 3.

Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) (%) based on whole genome alignments.

| |

B. velezensis FZB42 |

B. subtilis

168 |

P. megaterium

QM B1551 |

| MV4 |

98.36 |

77.3 |

68.77 |

| MV11 |

98.36 |

77.04 |

68.44 |

| MV24 |

77.3 |

98.54 |

68.97 |

| MV30 |

68.31 |

68.58 |

97.42 |

Table 4.

Number of genes putatively coding for the six CAZyme categories.

Table 4.

Number of genes putatively coding for the six CAZyme categories.

| Species and strain |

GH |

GT |

PL |

CE |

CBM |

AA |

Total |

| B. velezensis MV4 |

47 |

37 |

3 |

11 |

16 |

3 |

117 |

| B. velezensis MV11 |

48 |

37 |

3 |

11 |

16 |

3 |

118 |

|

B. velezensis FZB42 |

40 |

35 |

3 |

13 |

14 |

5 |

110 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| B. subtilis MV24 |

56 |

39 |

7 |

14 |

22 |

3 |

141 |

|

B. subtilis 168 |

56 |

34 |

7 |

14 |

23 |

4 |

138 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| P. megaterium MV30 |

49 |

42 |

1 |

20 |

23 |

5 |

140 |

|

P. megaterium QM B1551 |

53 |

42 |

1 |

24 |

21 |

5 |

146 |

Table 5.

Antimicrobial activity of MV4, MV11, MV24 and MV30 against a panel of target strains.

Table 5.

Antimicrobial activity of MV4, MV11, MV24 and MV30 against a panel of target strains.

| |

MV4 |

MV11 |

MV24 |

MV30 |

|

Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 7644 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

|

Bacillus cereus ATCC 10987 |

++ |

++ |

+ |

- |

|

Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Streptococcus faecalis ATCC 33186 |

+/- |

+/- |

- |

- |

|

Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 |

+/- |

+/- |

- |

- |

|

Salmonella enterica typhi ATCC 14028 |

+/- |

+/- |

- |

- |

|

Citrobacter rodensis ATCC 14580 |

+/- |

+/- |

- |

- |

|

Shigella sonnei ATCC 25931 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Pseudomonas fluorescens ATCC 13525 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Candida albicans ATCC 14028 |

+/- |

+/- |

- |

- |