Submitted:

08 June 2023

Posted:

09 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and methods

2.1. Experimental sites

2.2. Implementation of experiment

2.3. Nitrate leaching evaluation

2.4. Evaluation of protein percentage

2.5. Statistical analysis

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Analysis of variance

| Texture | S.O.V. | Grain yield | Dry matter | Protein % | N leaching |

| Sandy loam | Year | 16013581.4** | 221562237.5** | 8.28** | 0.005** |

| Year×Rep | 62185.9 | 43891.1 | 4.56 | 0.00 | |

| Application Time (AT) | 964579** | 1361045** | 13.2** | 0.006** | |

| Fertilizer Source (FS) | 79043.6n.s | 492n.s | 16.7** | 0.002** | |

| Year×TA | 110140.3n.s | 436469.2** | 1.6** | 0.00** | |

| Year×FS | 342727** | 477564** | 13.09** | 0.00** | |

| TA×FS | 398092.5** | 433432.2** | 6.4** | 0.002** | |

| Year×TA×FS | 498971.2** | 466510.2** | 0.71** | 0.002** | |

| Error | 42385.2 | 24300.1 | 0.23 | 0.00 | |

| C.V (%) | 9.12 | 14.4 | 4.9 | 0.41 | |

| Silty clay loam | Year | 4683751.6** | 6029696.22** | 6.5** | 0.005** |

| Year×Rep | 29678.6 | 24907.4 | 7.8 | 0.00 | |

| Application Time (AT) | 557473.9** | 693657.4** | 0.32n.s | 0.007** | |

| Fertilizer Source (FS) | 250785.1** | 275918.5** | 7.63** | 0.002** | |

| Year×TA | 168810.6** | 149574** | 1.17** | 0.00** | |

| Year×FS | 188446.5** | 481251.8** | 0.07n.s | 0.00** | |

| TA×FS | 642222.9** | 763590.7** | 0.18n.s | 0.002** | |

| Year×TA×FS | 58298.1* | 53240.7* | 0.4** | 0.002** | |

| Error | 15732.7 | 14767.4 | 0.1 | 0.00 | |

| C.V (%) | 8.92 | 3.36 | 3.5 | 0.75 | |

| Silty clay | Year | 2853762.1** | 1401790.7** | 22** | 0.006** |

| Year×Rep | 23909.7 | 45327.7 | 12.2 | 0.00 | |

| Application Time (AT) | 277543.3** | 241390.7** | 2** | 0.006** | |

| Fertilizer Source (FS) | 2216.9n.s | 27112.9n.s | 25.2** | 0.002** | |

| Year×TA | 420654.7** | 227112.9** | 1.89** | 0.00** | |

| Year×FS | 110082.7* | 273868.5** | 0.01** | 0.00** | |

| TA×FS | 654012.7** | 134501.8* | 0.54** | 0.002** | |

| Year×TA×FS | 737541.5** | 206590.7** | 0.9** | 0.002** | |

| Error | 34957.3 | 32516.6 | 0.05 | 0.00 | |

| C.V (%) | 6.86 | 4.9 | 3.21 | 0.54 |

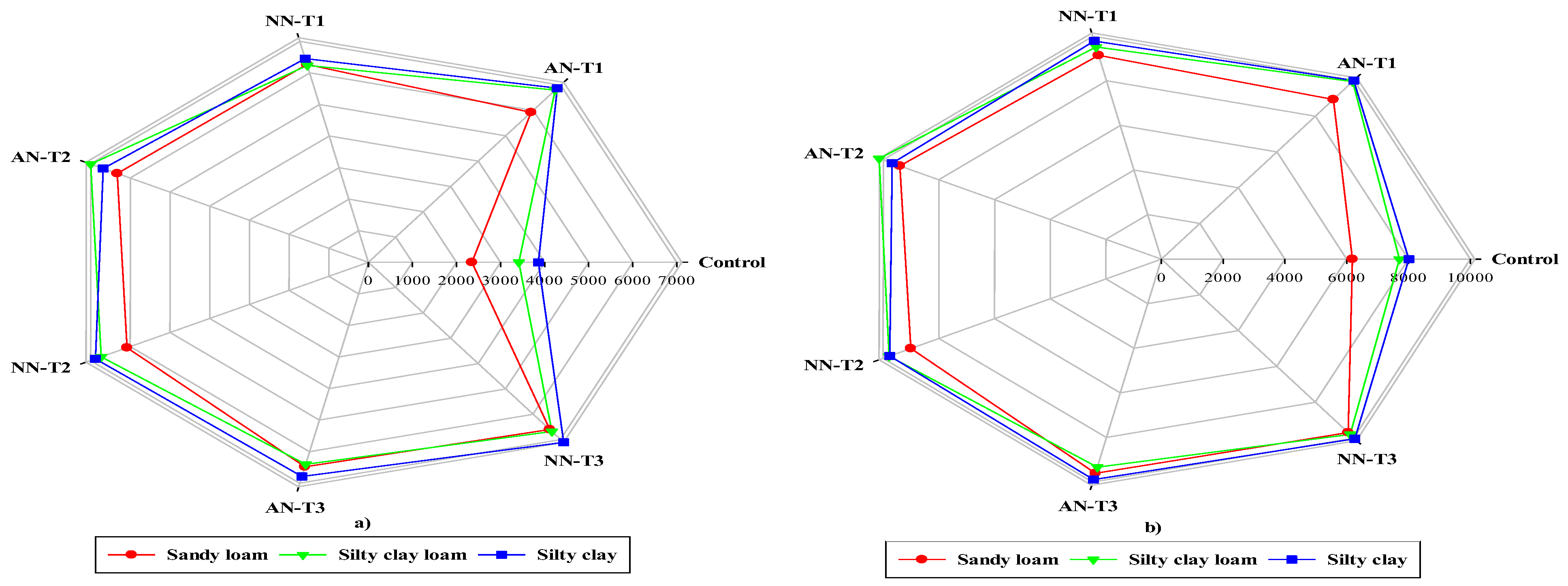

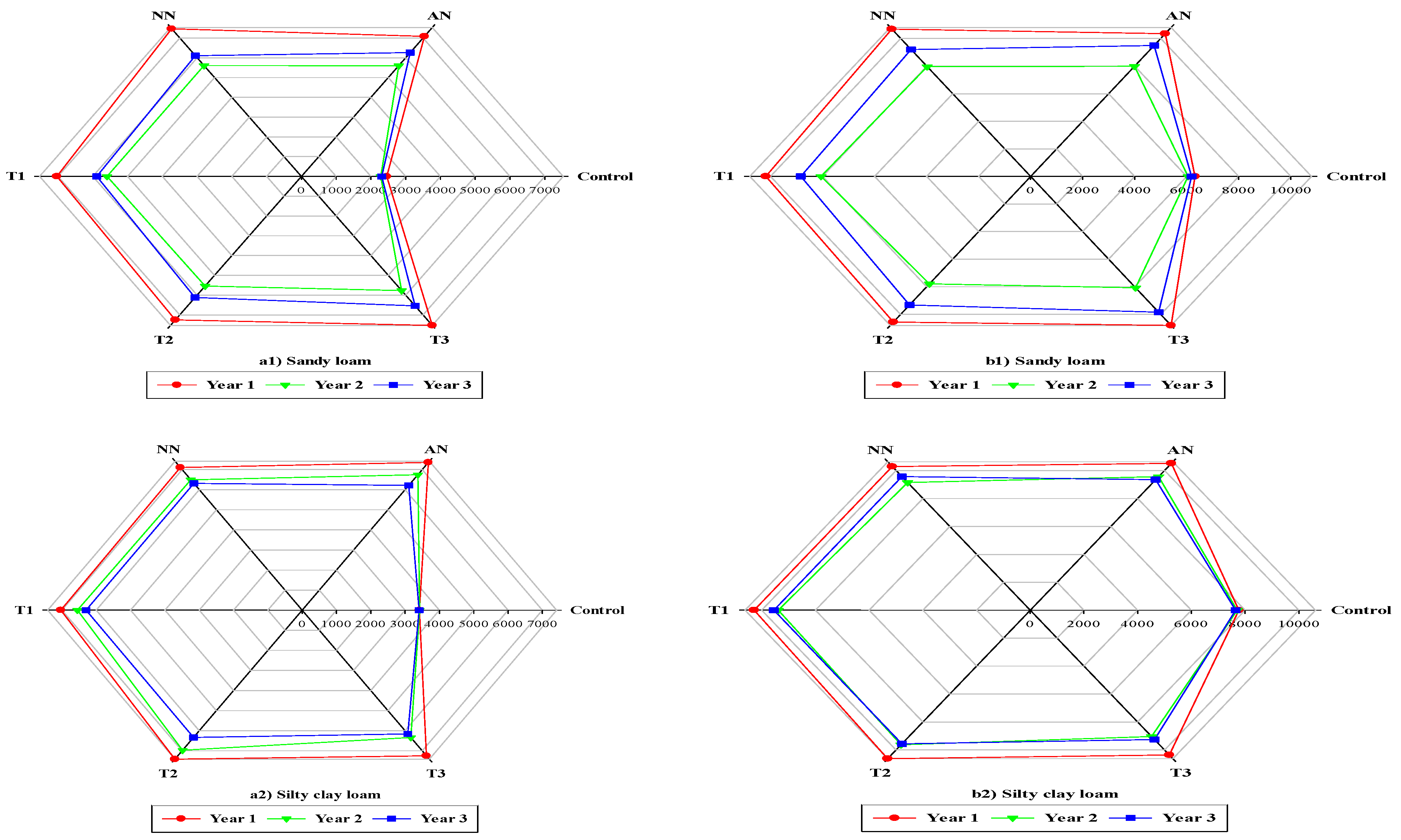

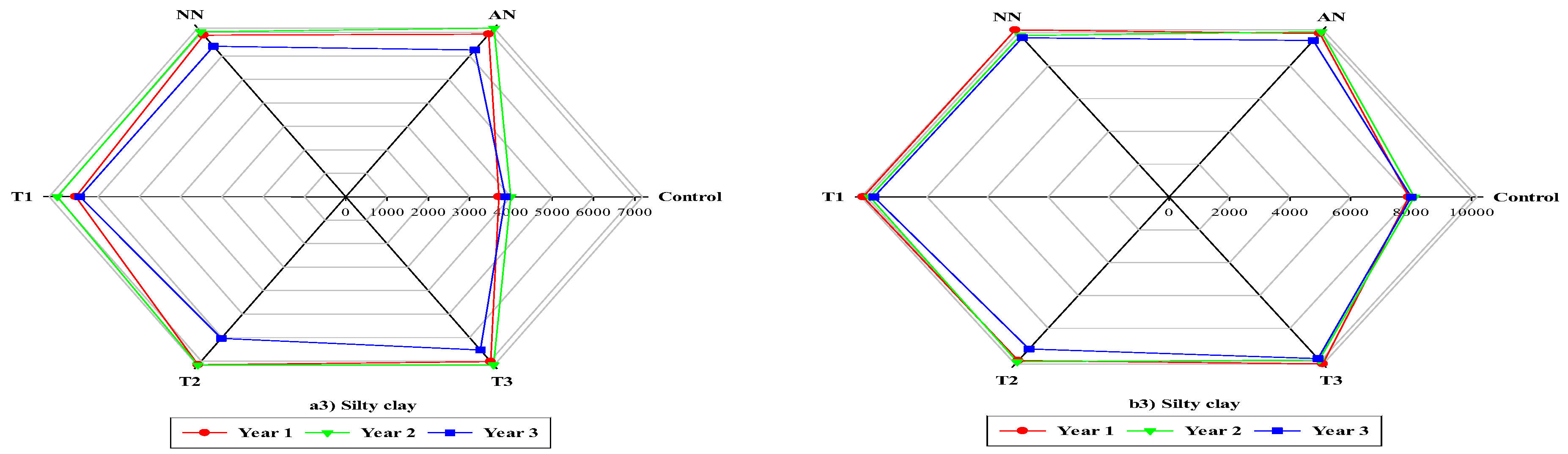

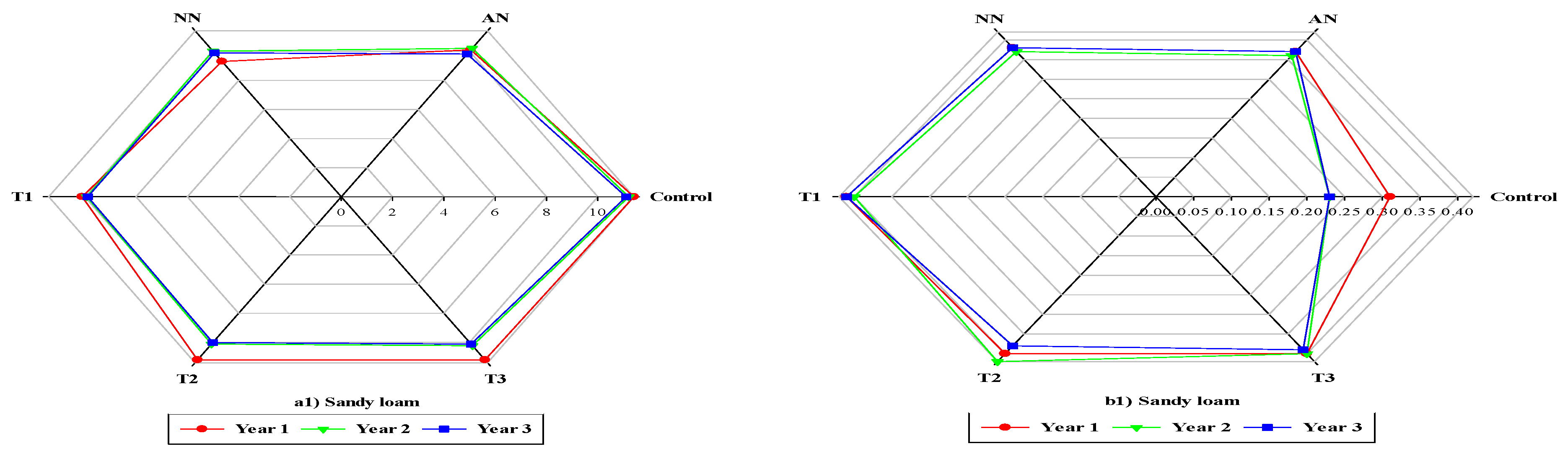

3.2. Grain yield and Dry matter

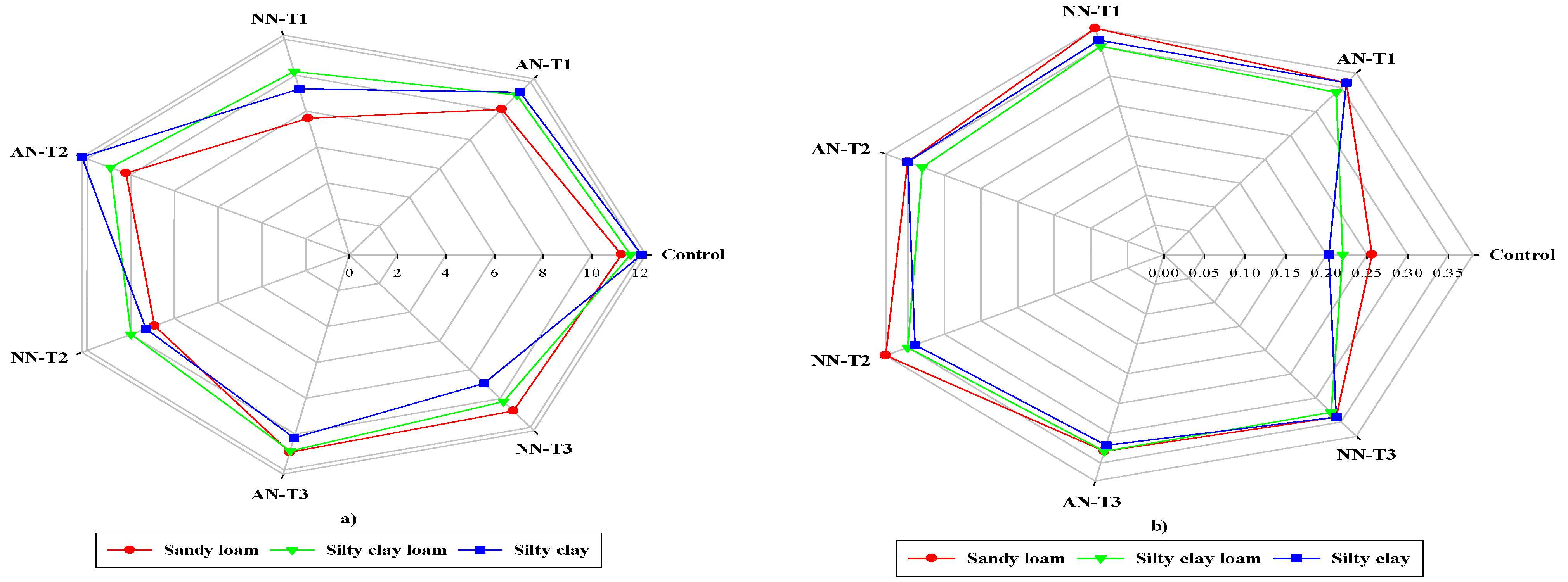

3.3. Protein percentage and Nitrate leaching

3.4. Interaction effects

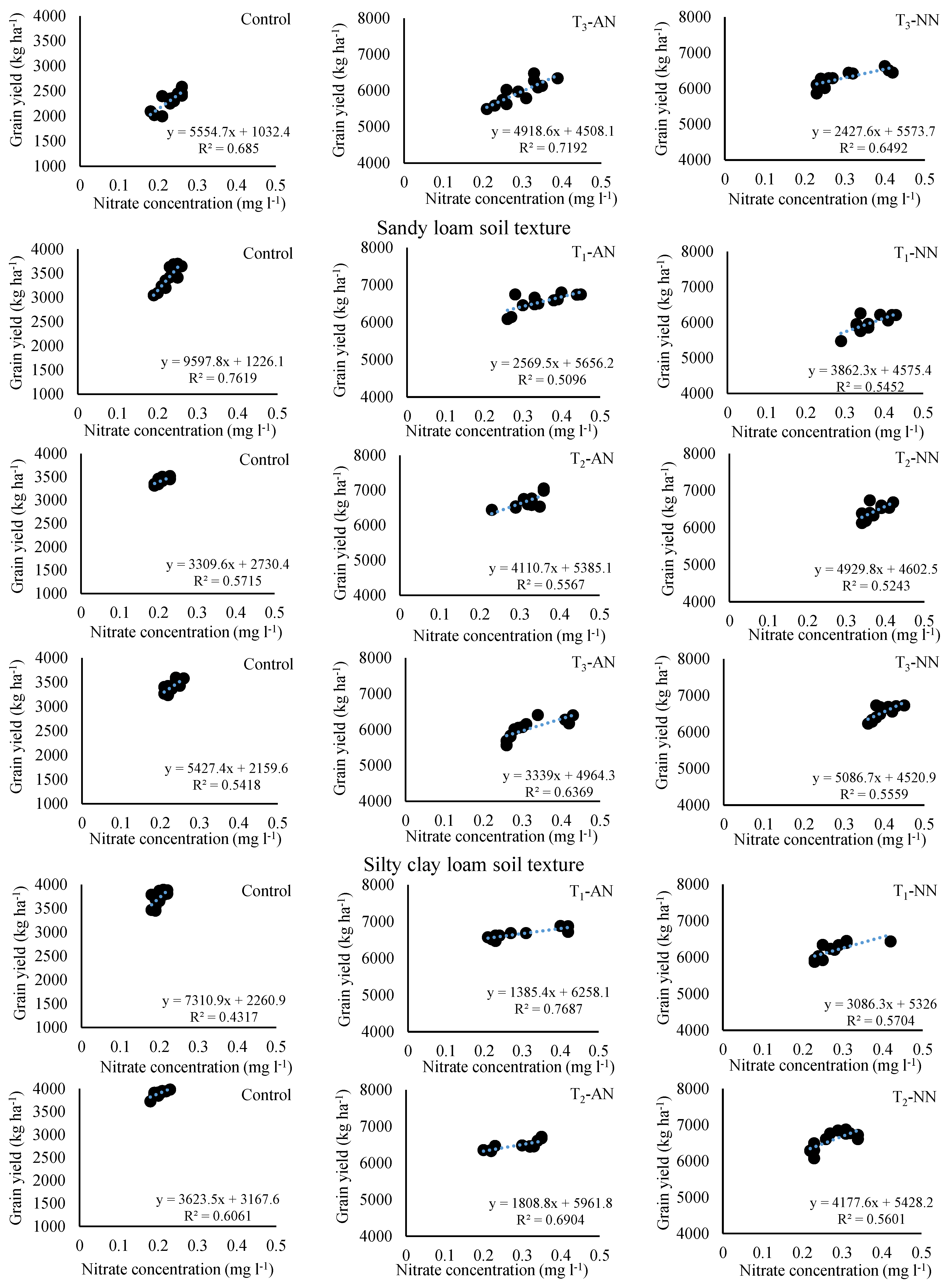

3.5. Correlation coefficients

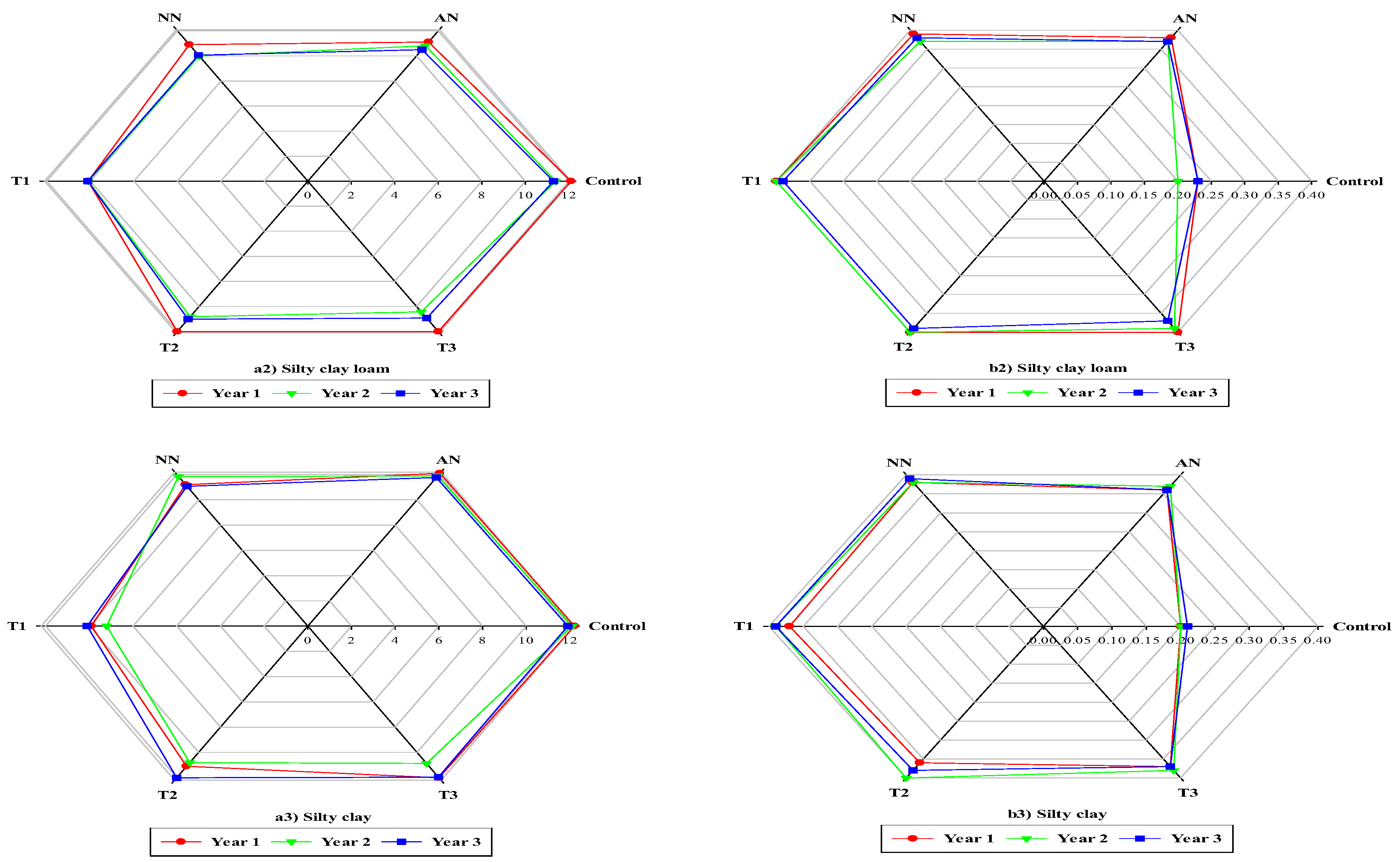

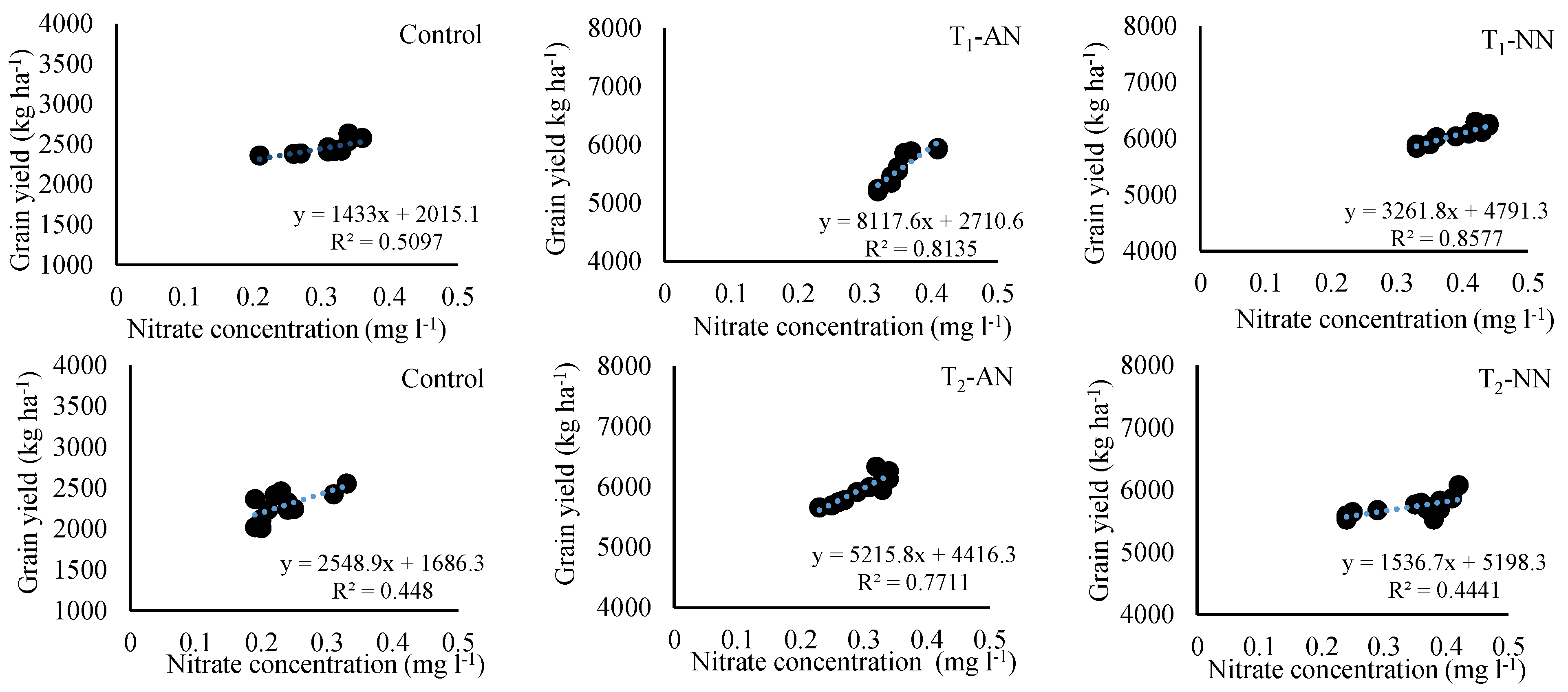

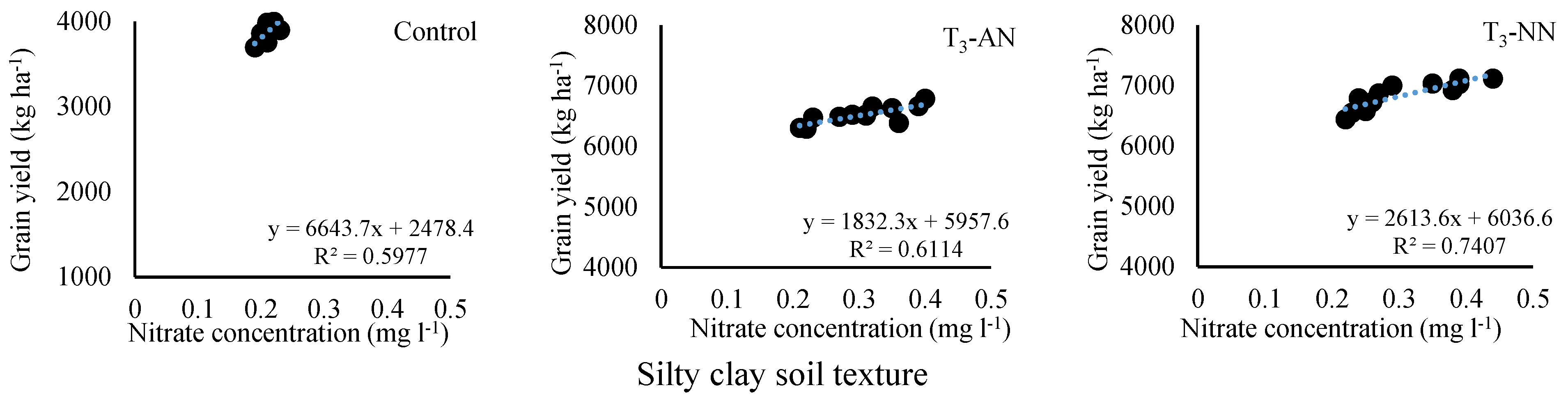

3.6. Relationship between grain yield and nitrate leaching

4. Conclusion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hochman, Z. Yield gap analysis with local to global relevance: a review. Field Crops Res. 2013, 143, 417. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, N.; Thompson, S.; Turchini, G.M. Organic aquaculture productivity, environmental sustainability, and food security: insights from organic agriculture. Food Secur. 2020, 12, 1253–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT. Aquastat. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2023.

- FAPRI. FAPRI, US and World Agricultural Outlook. Food and Agriculture Research Institute, Iowa. 2023.

- Sheibani, S.; Ghadiri, H. Integration effects of split nitrogen fertilization and herbicide application on weed management and wheat yield. J. Agr. Sci. Tech. 2012, 14, 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Sharafi, S. Predicting Iran’s future agro-climate variability and coherence using zonation? based PCA. Italian Journal of Agrometeorology 2022, 2, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Chaudhary, A.; Ahlawat, O.P.; Naorem, A.; Upadhyay, G.; Chhokar, R.S.; Gill, S.C.; Khippal, A.; Tripathi, S.C.; Singh, G.P. Crop residue management challenges, opportunities and way forward for sustainable food-energy security in India: A review. Soil and Tillage Research. 2023, 228, 105641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafi, S.; Kazemi, A.; Amiri, Z. Estimating energy consumption and GHG emissions in crop production: A machine learning approach. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 408, 137242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Cai, H.; Wang, X.; Ma, C.; Lu, Y.; Ding, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Saddique, Q. Exploring optimal irrigation and nitrogen fertilization in a winter wheat-summer maize rotation system for improving crop yield and reducing water and nitrogen leaching. Agricultural Water Management. 2020, 228, 105904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Buresh, R.J.; Huang, J.; Zhong, X.; Zou, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, G.; Liu, Y.; Hu, R.; Tang, Q.; et al. Improving nitrogen fertilization in rice by sitespecific N management. A review. Agronomy for sustainable development. 2010, 30, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafi, S. Effectiveness of different methods of zinc application to increase grain micronutrients of rainfed wheat under reduced nitrogen application rate. Journal of Crop Science and Biotechnology. 2023, 26, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodley, A.; Drury, C.; Yang, X.; Reynolds, W.; Calder, W.; Oloya, T. Streaming urea ammonium nitrate with or without enhanced efficiency products impacted corn yields, ammonia, and nitrous oxide emissions. Agronomy Journal 2018, 110, 444–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linton, N.F.; Machado, P.V.F.; Deen, B.; Wagner-Riddle, C.; Dunfield, K.E. Long-term diverse rotation alters nitrogen cycling bacterial groups and nitrous oxide emissions after nitrogen fertilization. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2020, 149, 107917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnett, T.; Conn, V.; Kaiser, B.N. Root based approaches to improving nitrogen use efficiency in plants. Plant cell environment 2009, 32, 1272–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishfaq, M.; Akbar, N.; Zulfiqar, U.; Ali, N.; Jabran, K.; Nawaz, M.; Farooq, M. Influence of nitrogen fertilization pattern on productivity, nitrogen use efficiencies, and profitability in different rice production systems. Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition 2020, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway, J.N.; Leach, A.M.; Bleeker, A.; Erisman, J.W. A chronology of human understanding of the nitrogen cycle. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences. 2013, 368, 20130120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coskun, D.; Britto, D.T.; Shi, W.; Kronzucker, H.J. Nitrogen transformations in modern agriculture and the role of biological nitrification inhibition. Nature Plants. 2017, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabak, M.; Lepiarczyk, A.; Filipek-Mazur, B.; Lisowska, A. Efficiency of nitrogen fertilization of winter wheat depending on sulfur fertilization. Agronomy Journal. 2020, 10, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, A.; Liu, H.; Zhai, L.; Lei, B.; Ren, T. An optimal regional nitrogen application threshold for wheat in the North China Plain considering yield and environmental effects. Field Crops Research 2017, 207, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, S.M.; Messina, C.D.; Vyn, T.J. Simultaneous gains in grain yield and nitrogen efficiency over 70 years of maize genetic improvement. Scientific reports 2019, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehman, H.U.; Basra, S.M.; Wahid, A. Optimizing nitrogen-split application time to improve dry matter accumulation and yield in dry direct seeded rice. International Journal of Agriculture and Biology 2013, 15, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, P.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, A.; Li, X.; Ma, D.; Xin, X.; Zhang, C.; Wu, S.; Garland, G.; Pereira, E.I. Nitrate accumulation and leaching potential reduced by coupled water and nitrogen management in the Huang-Huai-Hai Plain. Science of the Total Environment. 2018, 610, 1020–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delin, S. Site-specific nitrogen fertilization demand in relation to plant available soil nitrogen and water 2005, vol 2005, 6.

- Wang, Z.; Miao, Y.; Li, S. Effect of ammonium and nitrate nitrogen fertilizers on wheat yield in relation to accumulated nitrate at different depths of soil in drylands of China. Field Crops Research. 2015, 183, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafi, S.; Ghaleni, M. Spatial assessment of drought features over different climates and seasons across Iran. Theor. Appl. Climatol 2022, 147, 941–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Analytical biochemistry 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SAS I. Base SAS 9.4 procedures guide: statistical procedures Cary, NC, USA: SAS Institute Inc, 2013.

- Golba, J.; Rozbicki, J.; Gozdowski, D.; Sas, D.; Madry, W.; Piechocinski, M.; Kurzynska, L.; Studnicki, M.; Derejko, A. Adjusting yield components under different levels of N applications in winter wheat. International Journal of Plant Production. 2013, 7, 139–150. [Google Scholar]

- Soltani, A.; Robertson, M.; Manschadi, A. Modeling chickpea growth and development: Nitrogen accumulation and use. Field crops research 2006, 99, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Guo, T.; Wang, C. Effects of nitrogen fertilizer applied at different development stages on the activities of photosynthetic enzymes in winter wheat flag leaves. Plant Physiology Communications. 2006, 42, 1091. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Mei, X.; Nangia, V.; Guo, R.; Liu, Y.; Hao, W.; Wang, J. Effects of different nitrogen fertilizers on the yield, water-and nitrogen-use efficiencies of drip-fertigated wheat and maize in the North China Plain. Agricultural Water Management. 2021, 243, 106474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Huang, G. The effect of nitrogen rates on yields and nitrogen use efficiencies during four years of wheat–maize rotation cropping seasons. Agronomy Journal. 2016, 108, 2076–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, T.; Doerge, T.; Ottman, M. Improved nitrogen management in irrigated durum wheat using stem nitrate analysis: II. interpretation of nitrate-nitrogen concentrations. Agronomy Journal 1991, 83, 353–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafi, S.; Sharifdost, F.; Mohajeri, F. Effect of Fe, Zn and Cu on quantity and quality characteristics and nutrient accumulation in wheat. Journal of Crop Science and Biotechnology 2021, 24, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Experimental Site |

Soil texture | pH | EC (ds cm-3) |

Soil Bulk Density (g cm-3) | O.C (%) |

O.M (%) |

N (%) |

P (mg kg-1) |

K (mg kg-1) |

| 1 | Sandy loam | 7.4 | 1.54 | 1.56 | 1.02 | 1.76 | 0.09 | 13.1 | 235 |

| 2 | Silty clay loam | 7.32 | 1.51 | 1.51 | 1.21 | 2.08 | 0.1 | 14.2 | 281 |

| 3 | Silty clay | 7.12 | 1.52 | 1.51 | 1.53 | 2.63 | 0.12 | 15.2 | 301 |

| Traits | GY | DM | PP | N-L |

| GY | 1 | |||

| DM | 0.93** | 1 | ||

| PP | 0.24n.s | 0.34n.s | 1 | |

| N-L | -0.55* | -0.88** | -0.51* | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).