Submitted:

07 June 2023

Posted:

07 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

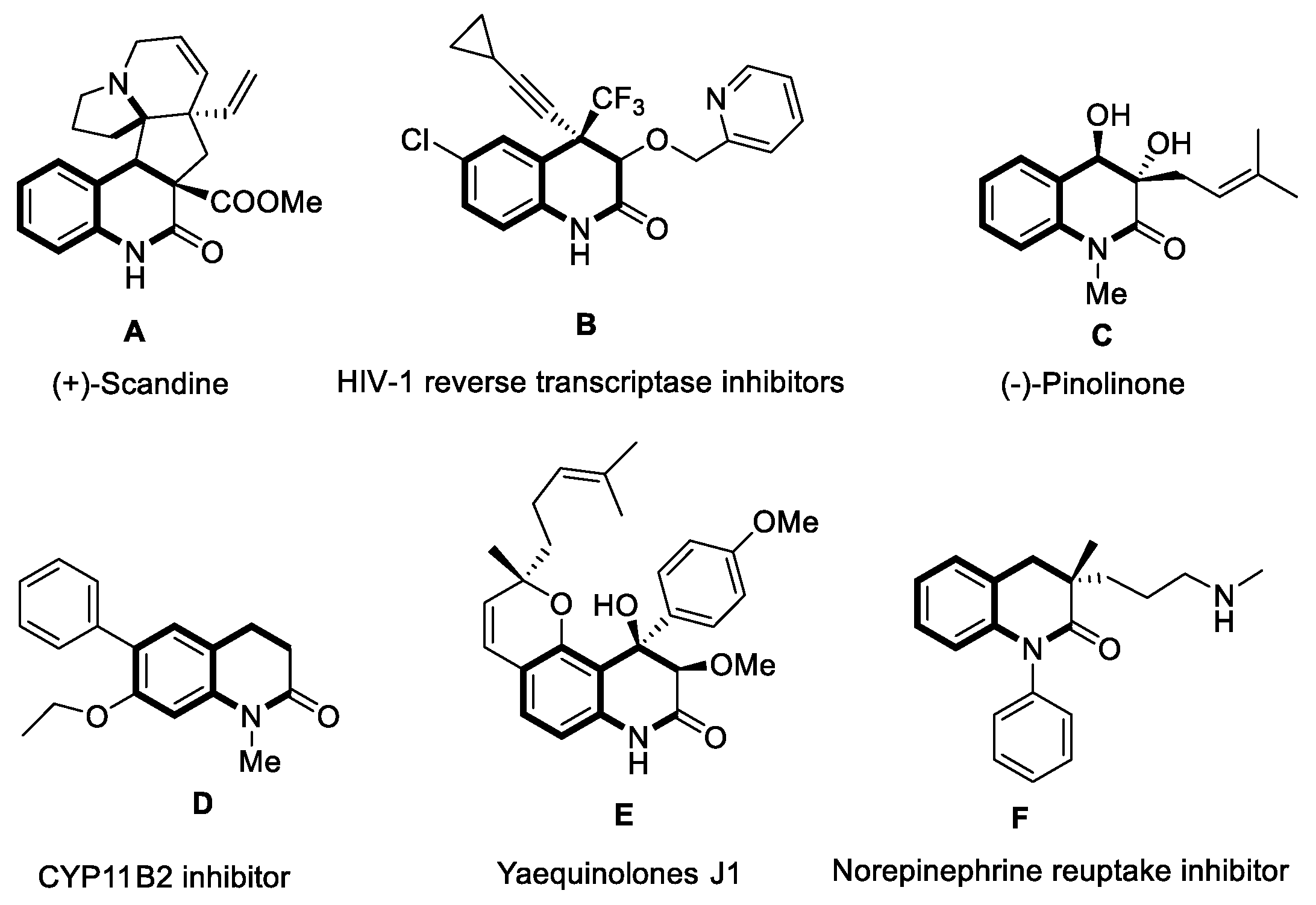

1. Introduction

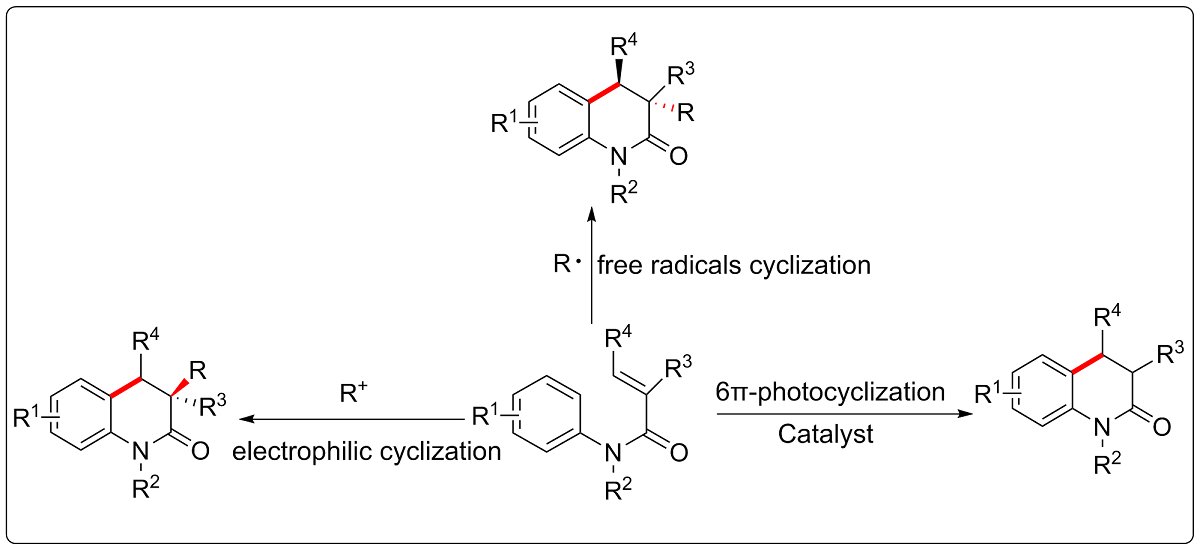

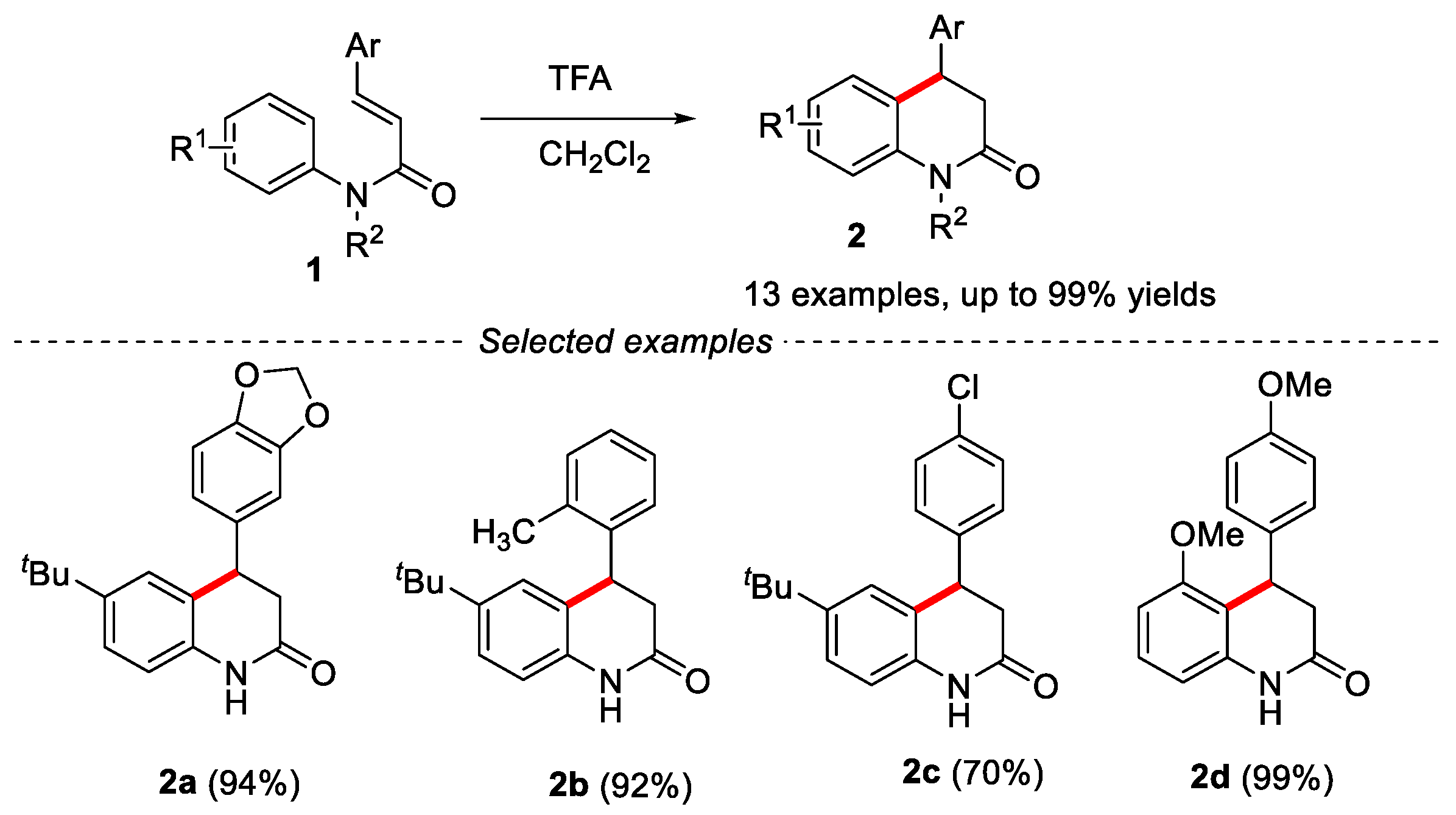

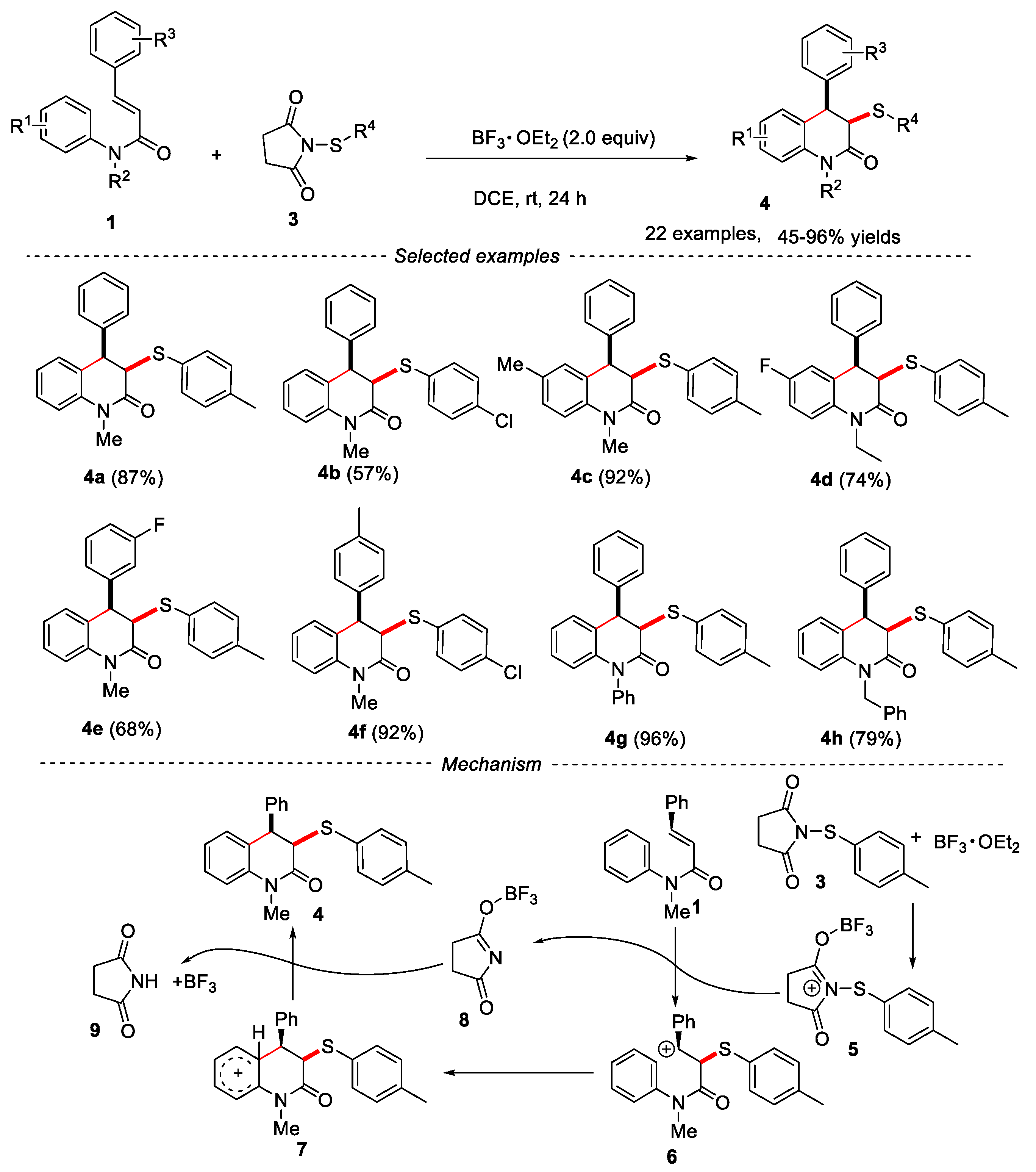

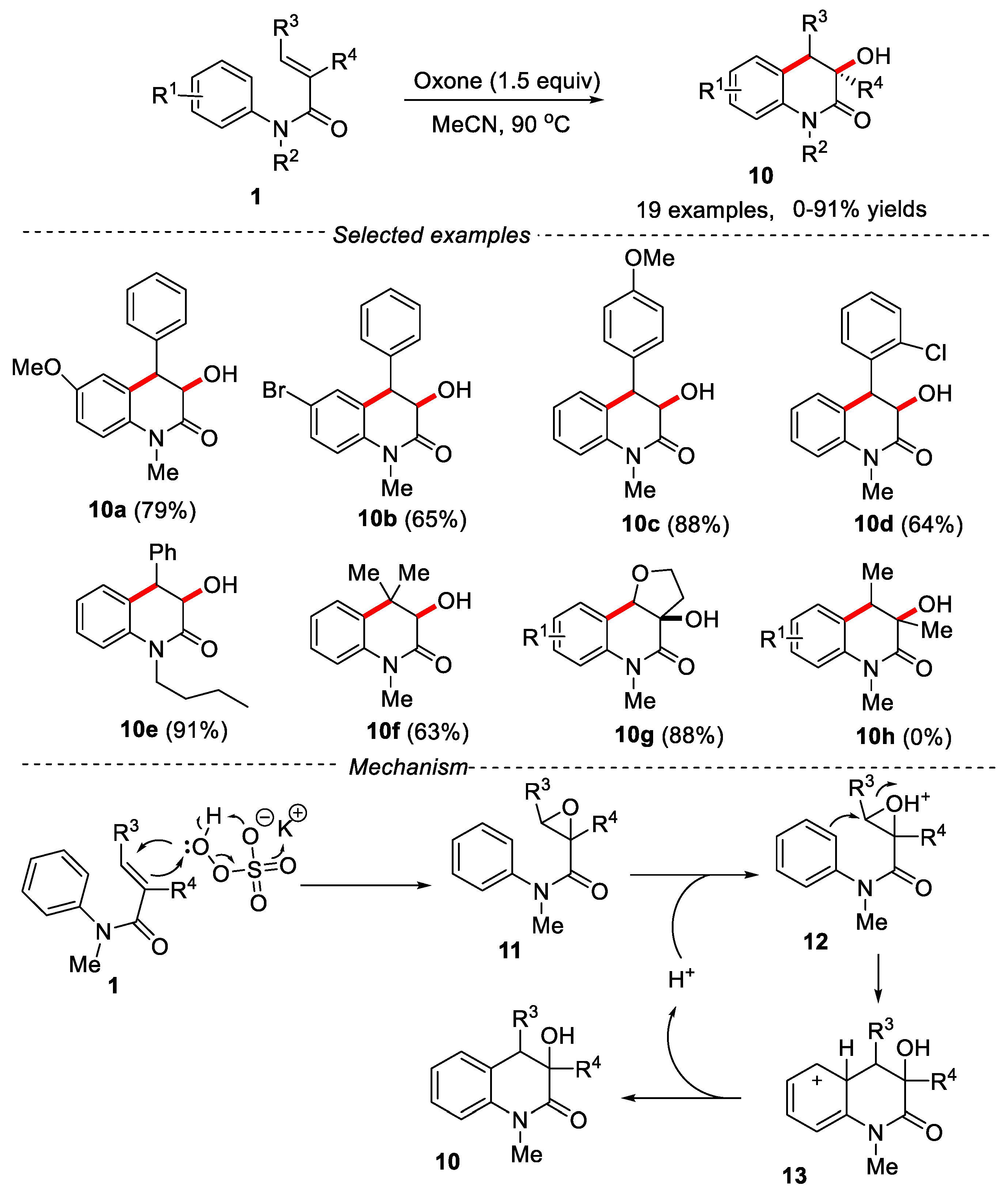

2. Synthesis of 3,4-dihydroquinolin-2(1H)-ones via electrophilic cyclization reactions

3. Synthesis of 3,4-dihydroquinolin-2(1H)-ones via different free radicals initiated cyclization reactions

3.1. Synthesis of 3,4-dihydroquinolin-2(1H)-ones using alkyl radicals.

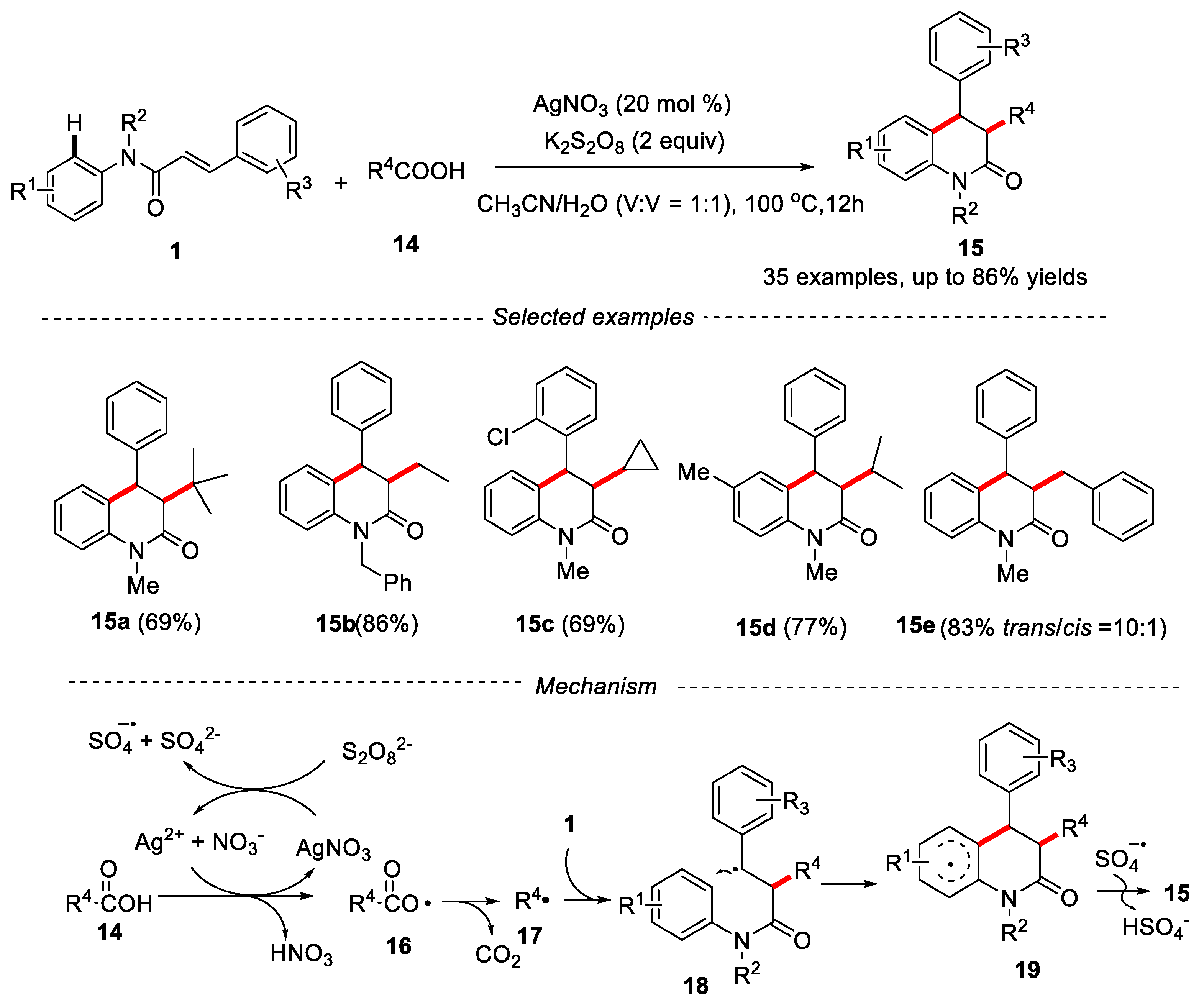

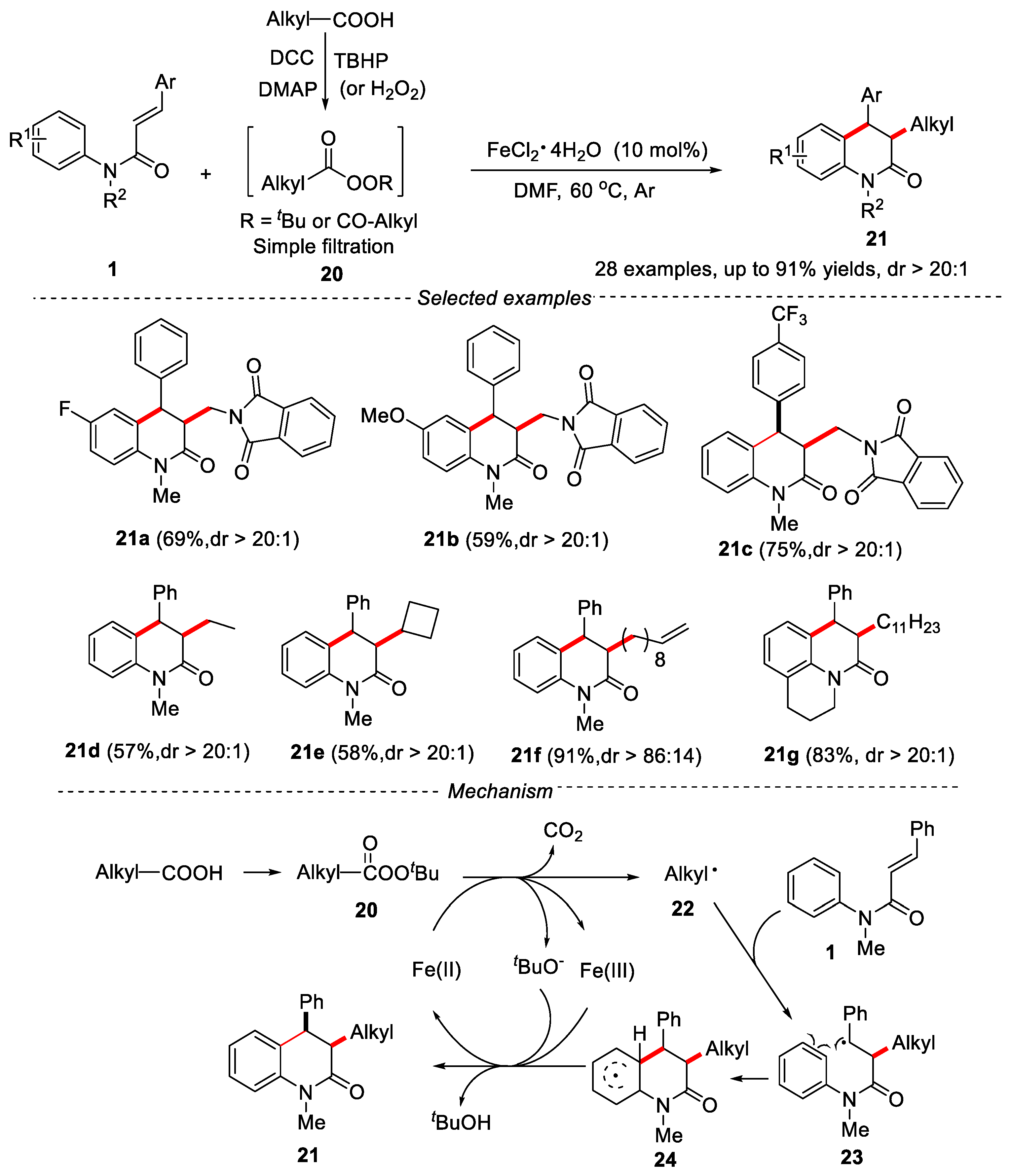

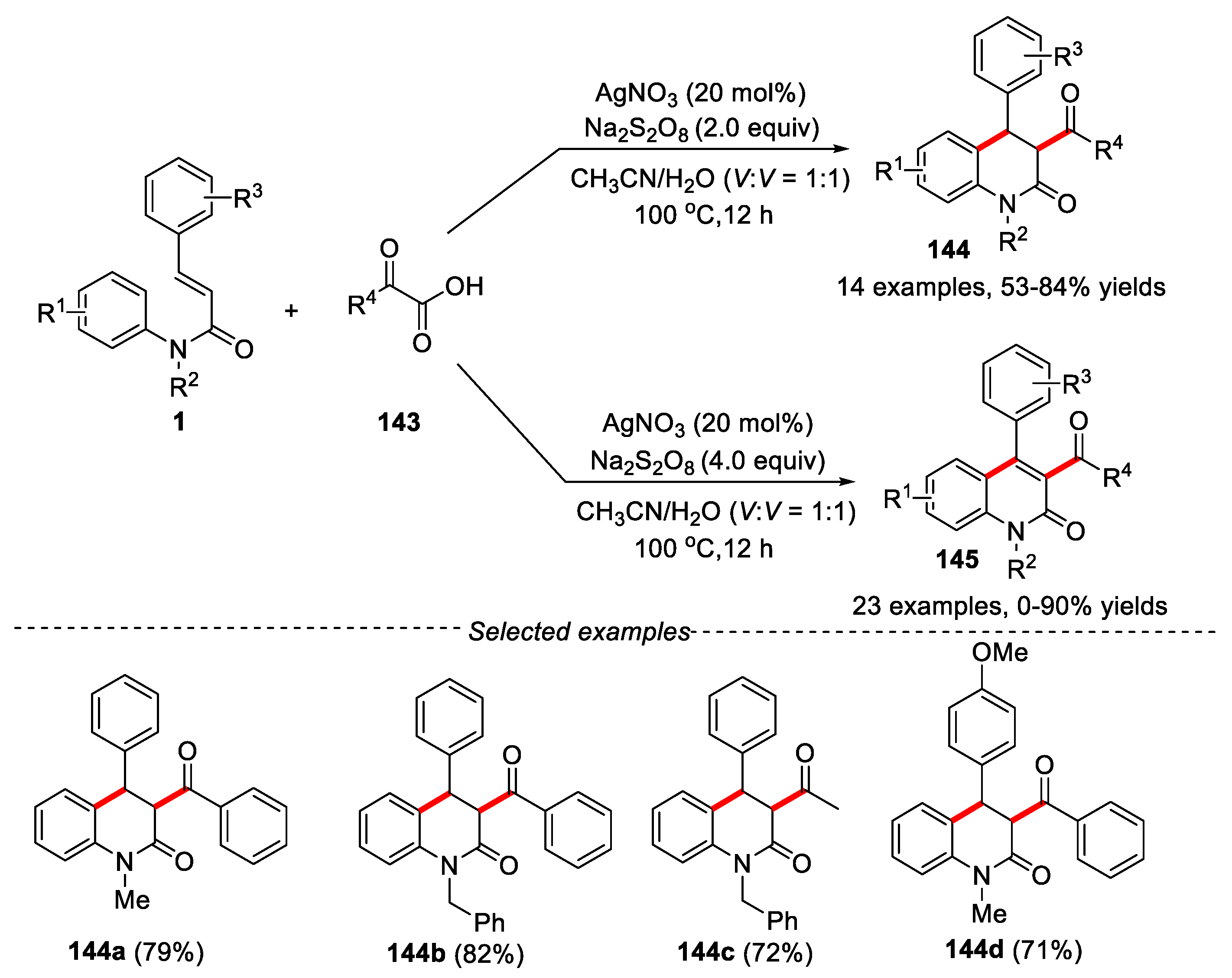

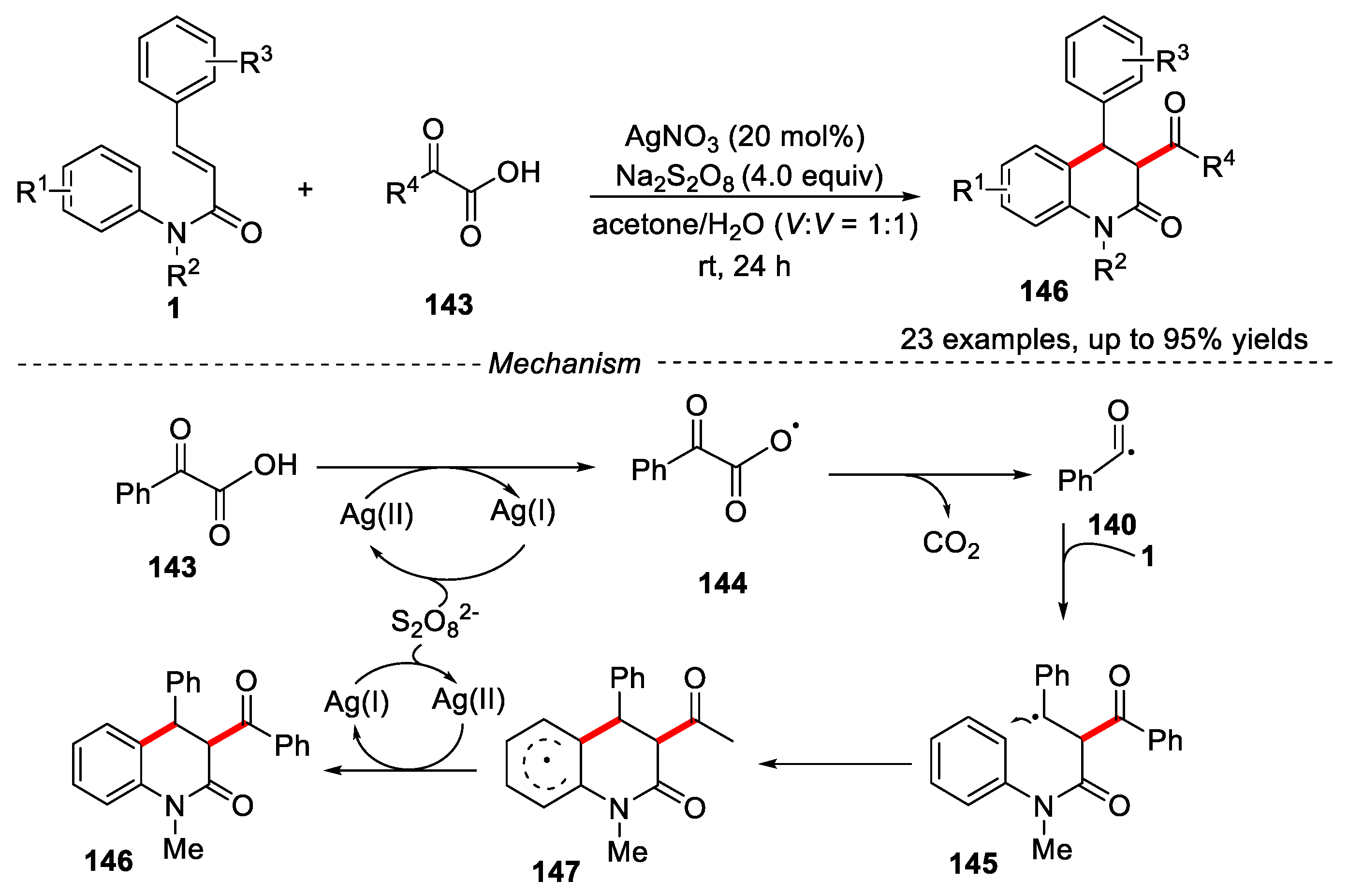

3.1.1. Carboxylic acids as alkyl radical precursors

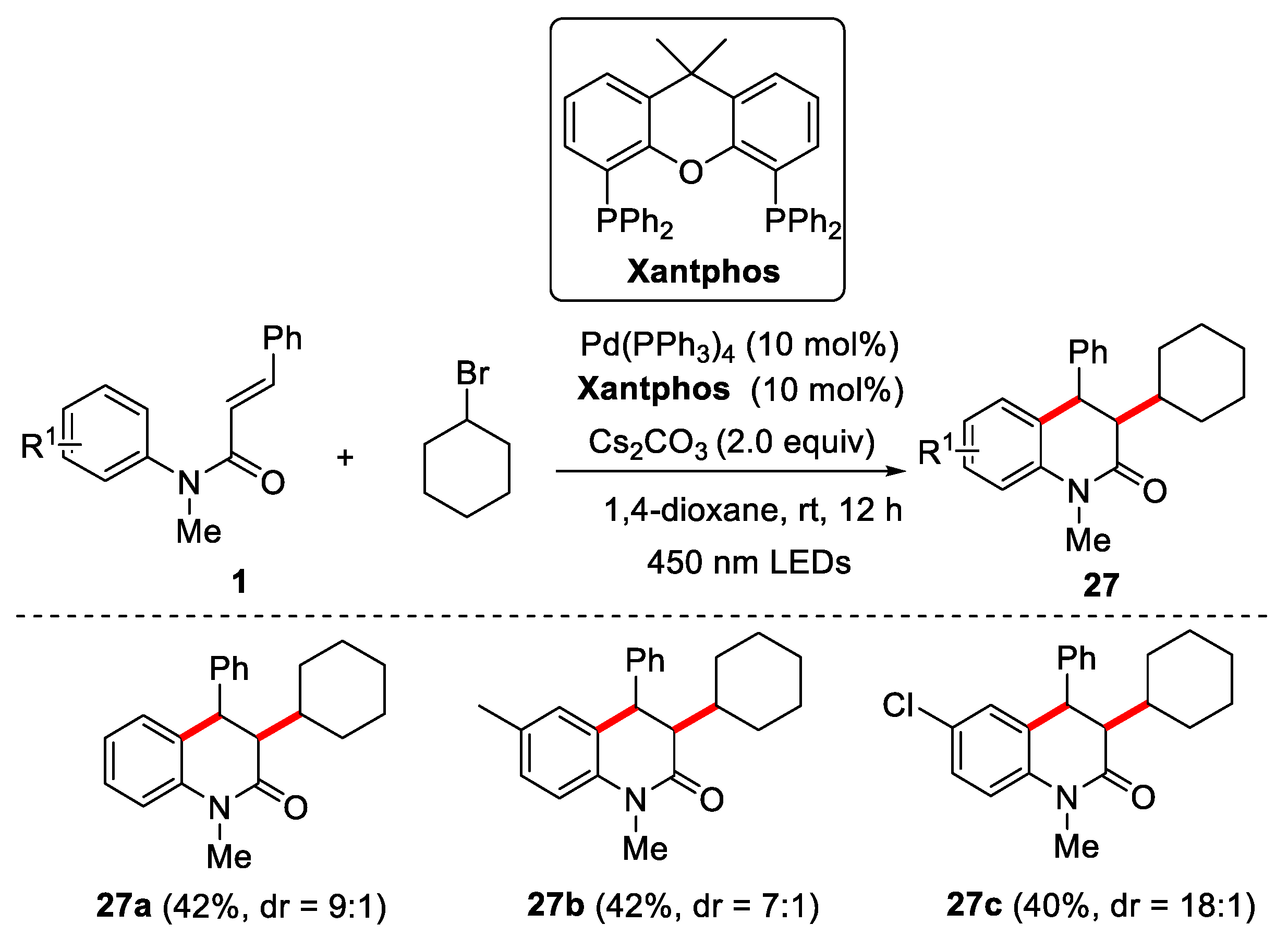

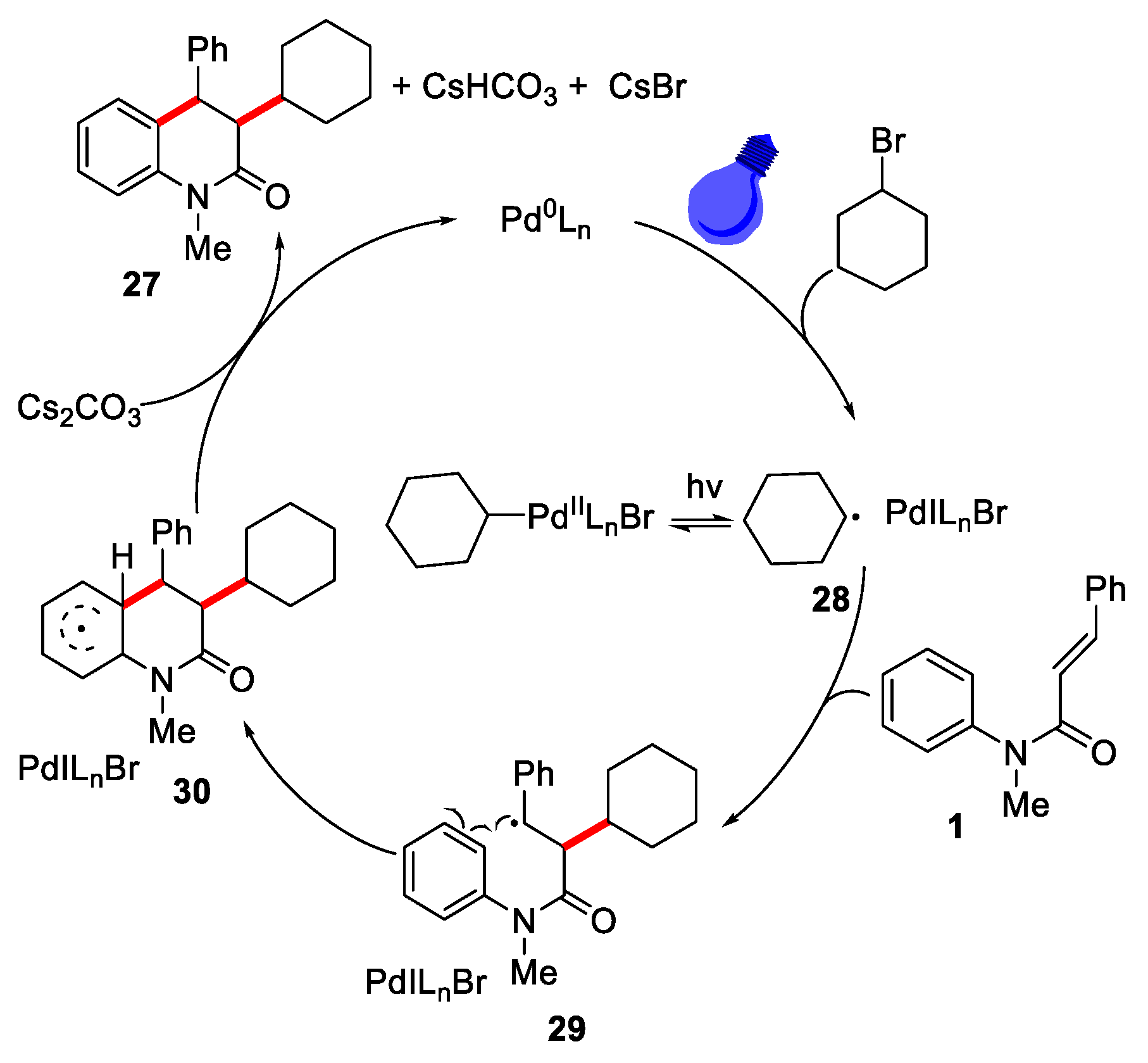

3.1.2. Alkyl halides as alkyl radical precursors

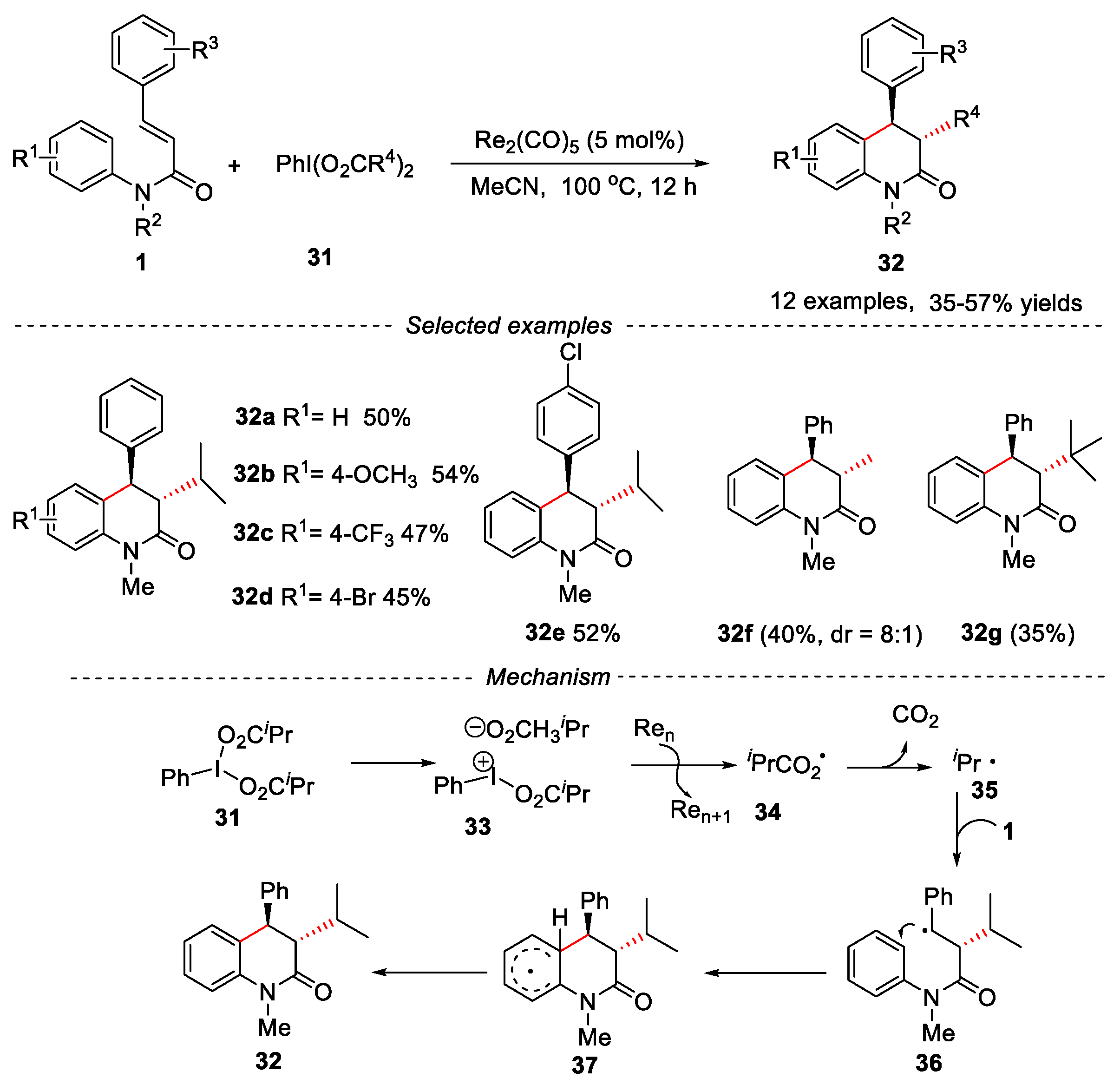

3.1.3. Hypervalent iodine (III) reagent (HIR) as alkyl radical precursors

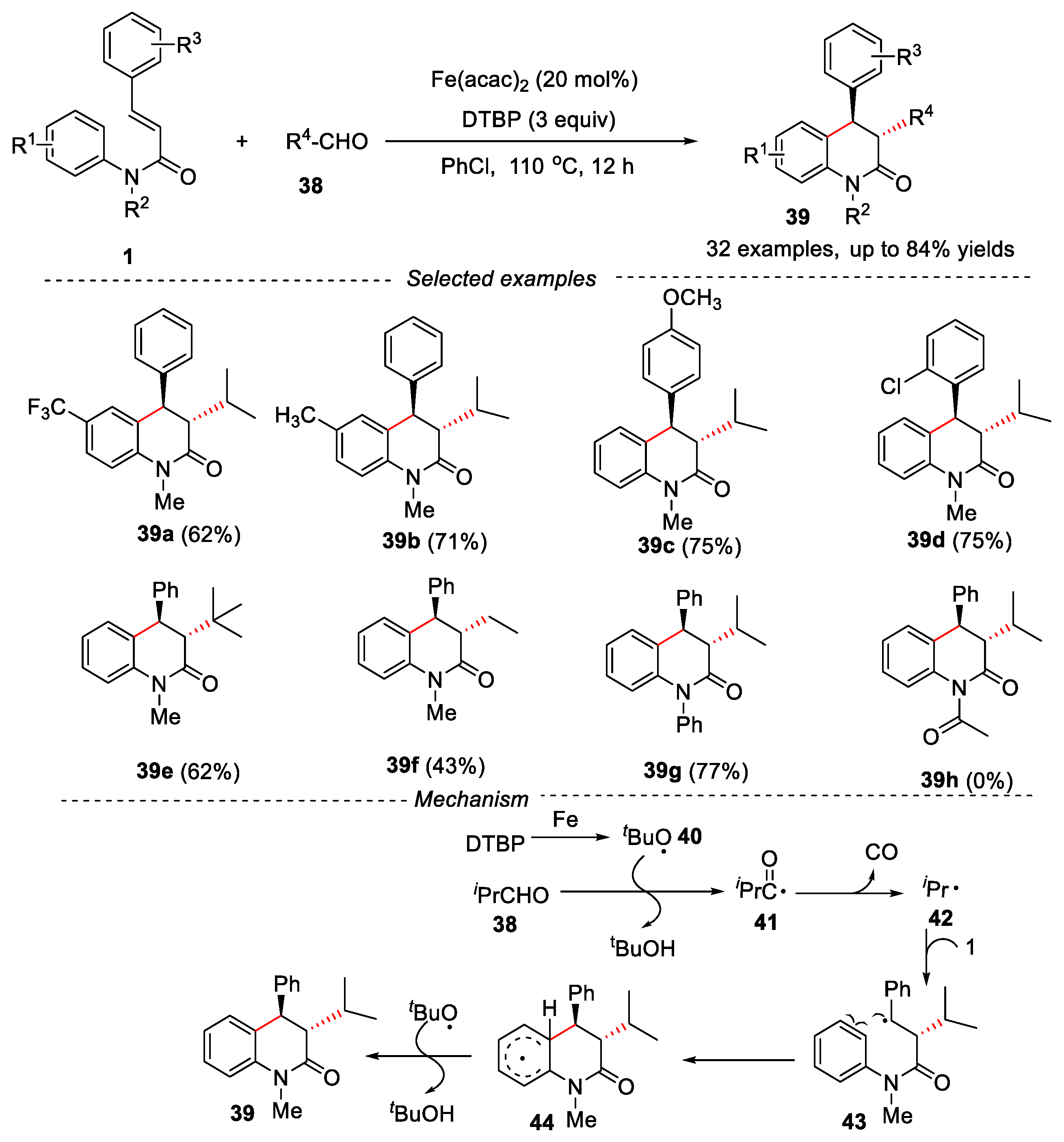

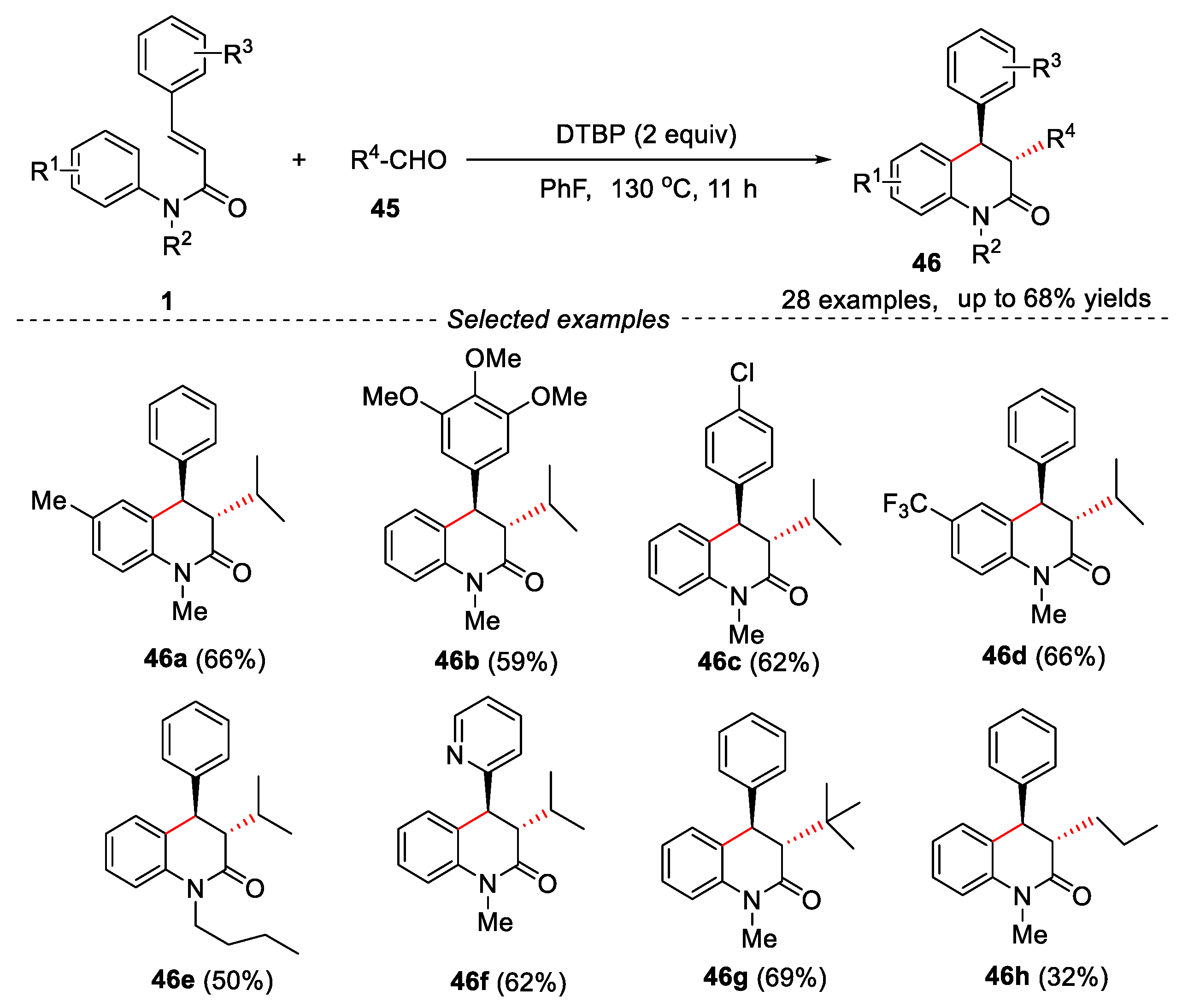

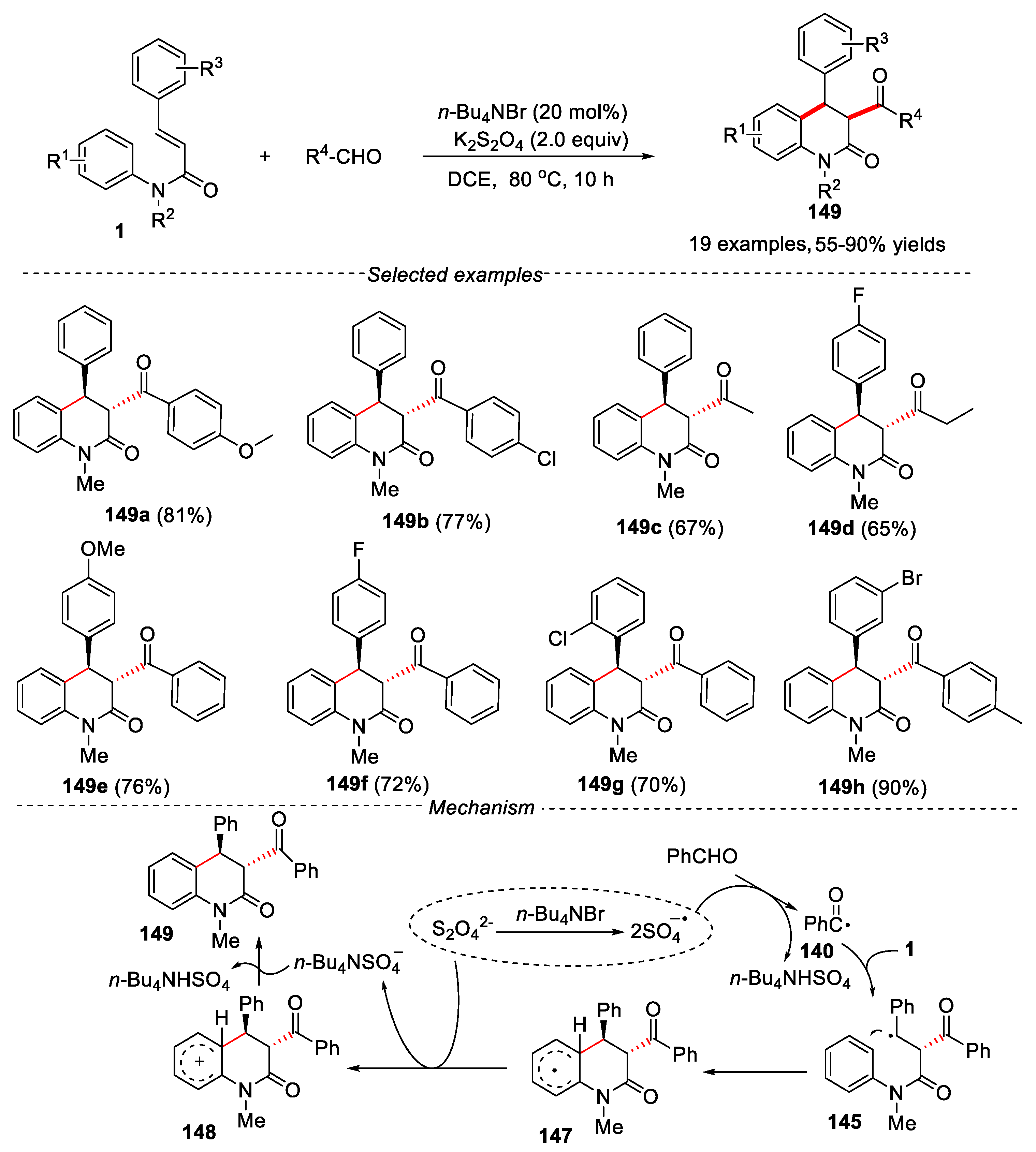

3.1.4. Aliphatic aldehydes as alkyl radical precursors

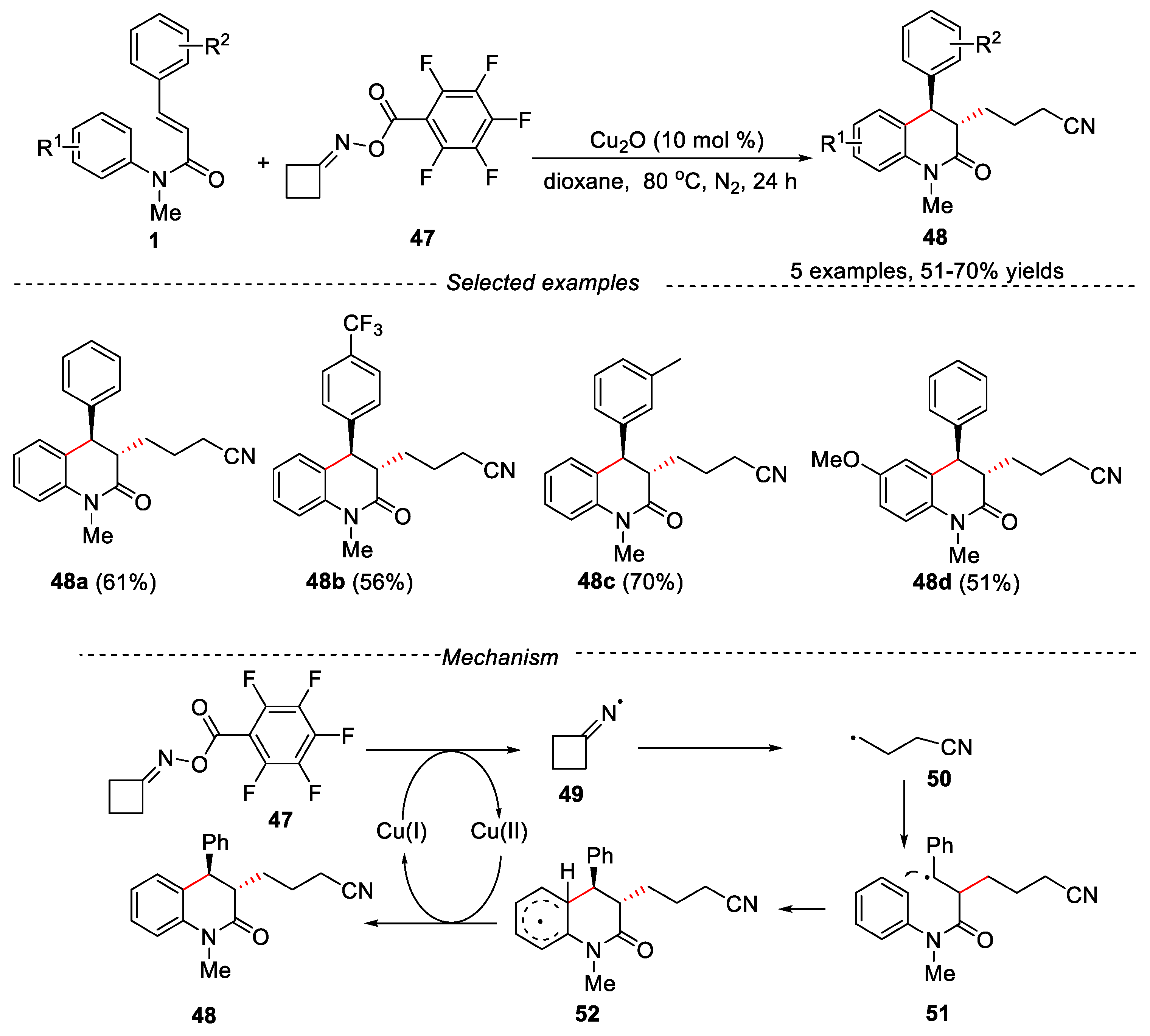

3.1.5. Cyclohexanone oxime ester as alkyl radical precursors

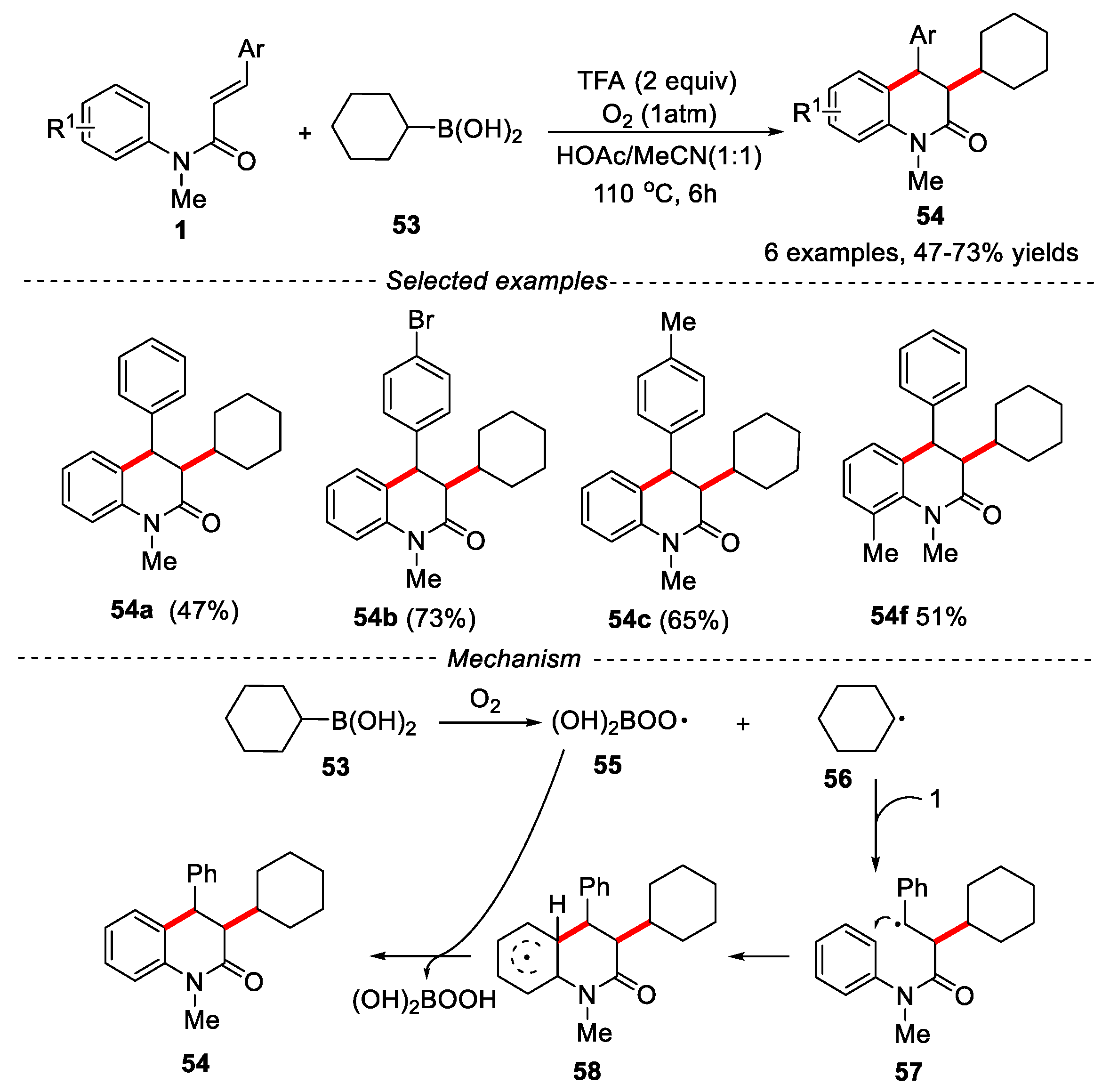

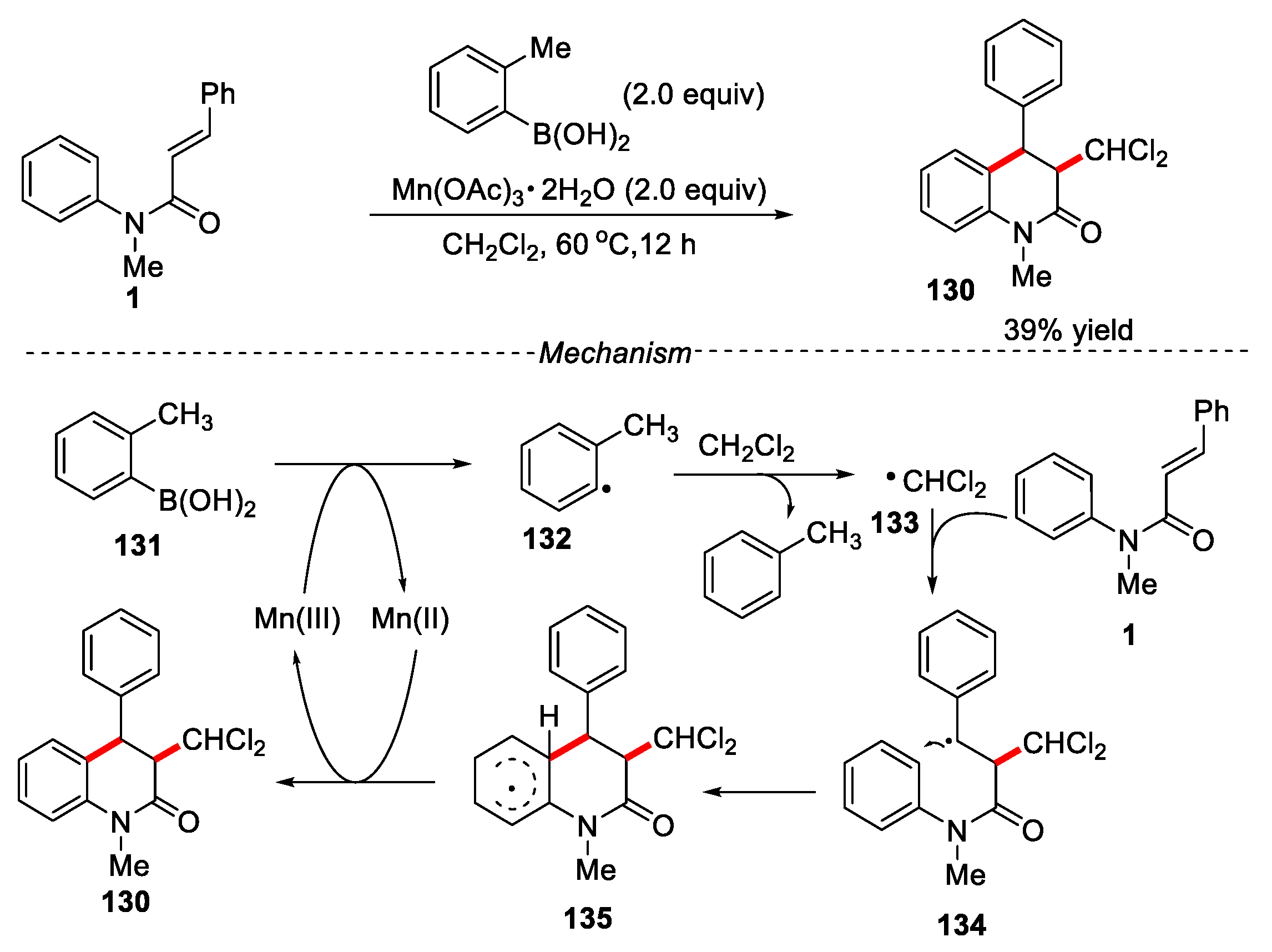

3.1.6. Organoboronic acid as alkyl radical precursors

3.2. Synthesis of 3,4-dihydroquinolin-2(1H)-ones using fluoroalkyl radicals

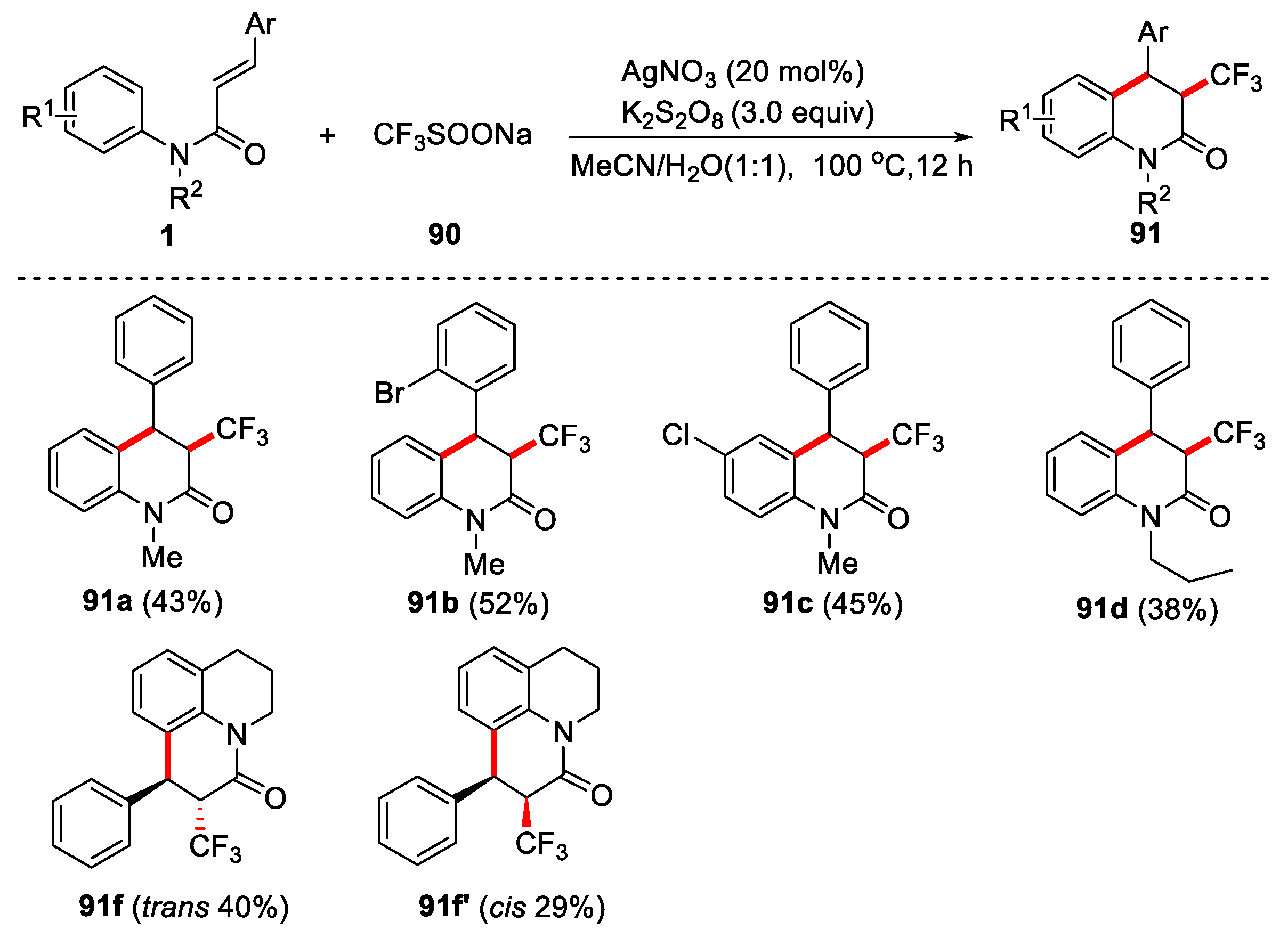

3.2.1. Using CF3SO2Na or HCF2SO2Na as fluorine sources

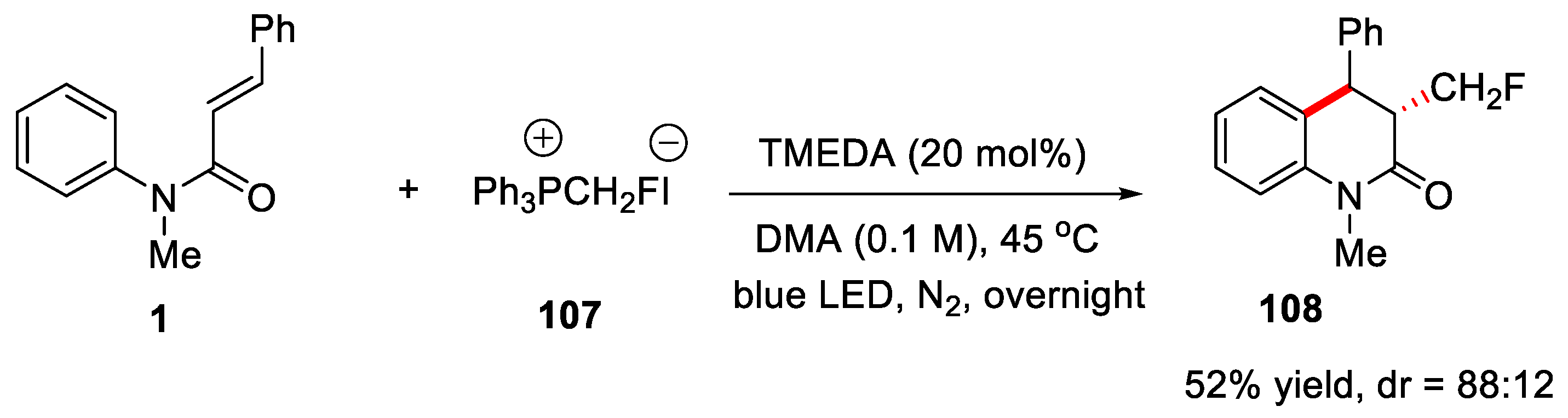

3.2.2. Using Ph3PCH2FI as fluorine sources

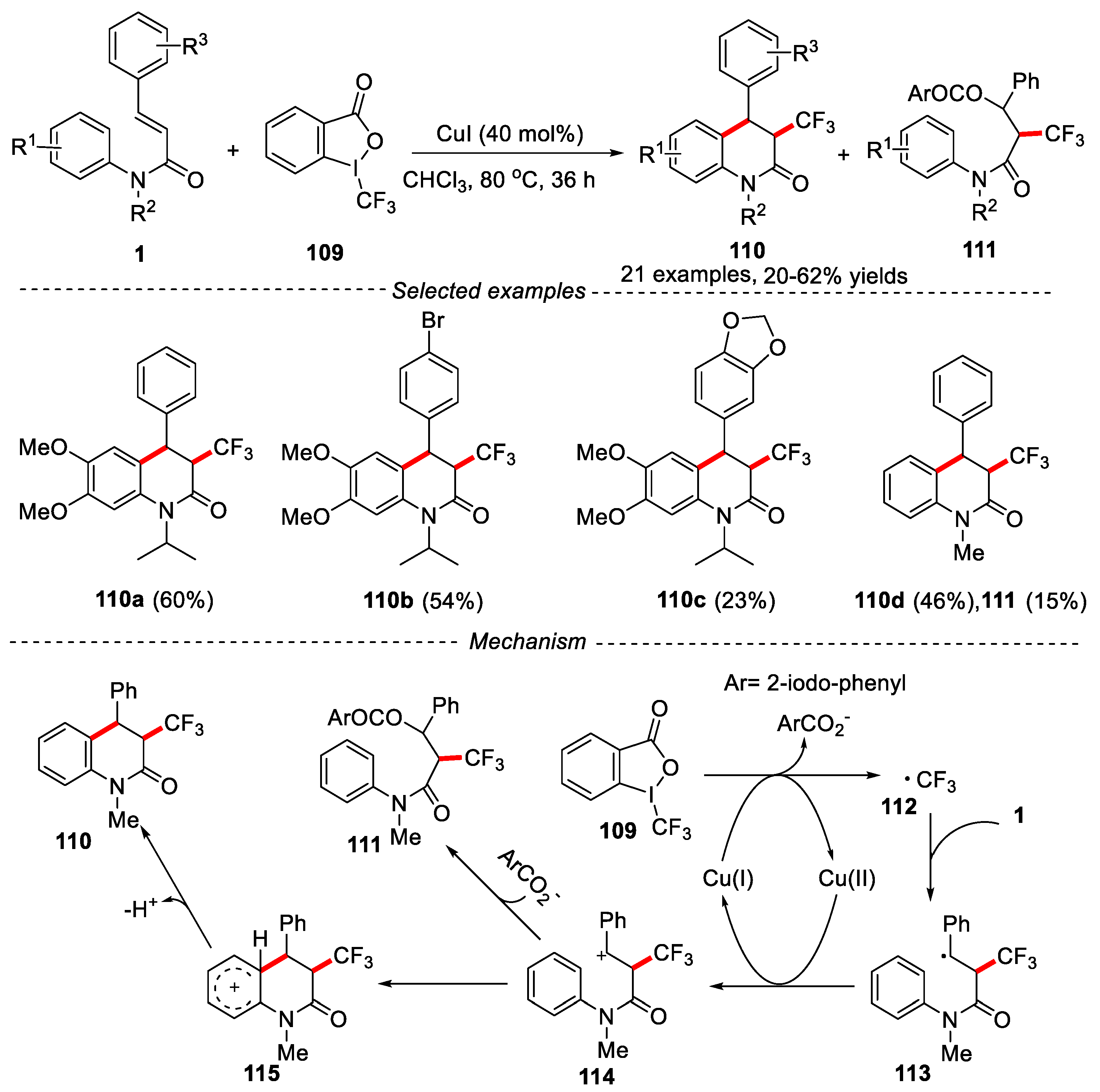

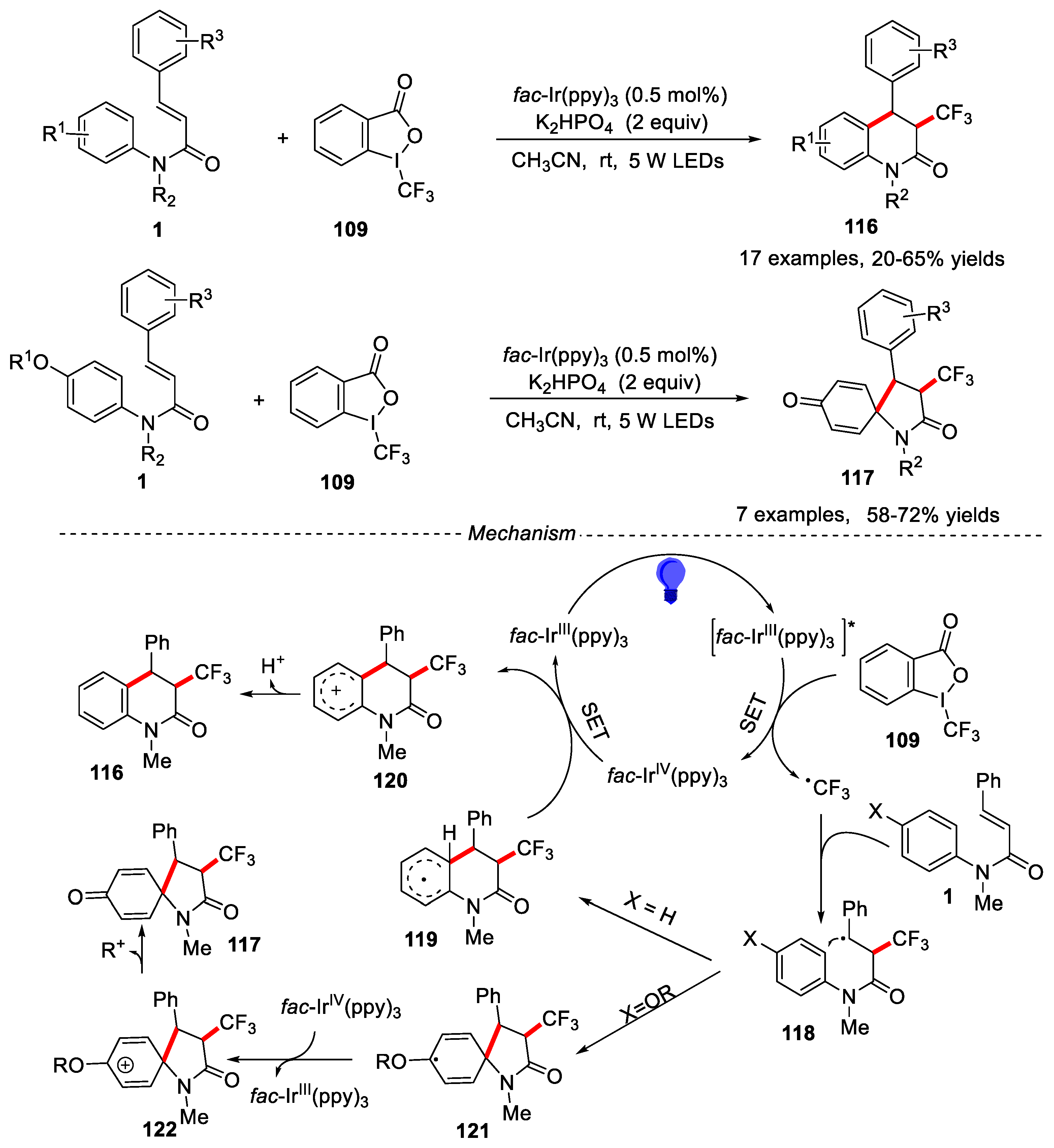

3.2.3. Using Togni's Reagents as fluorine sources

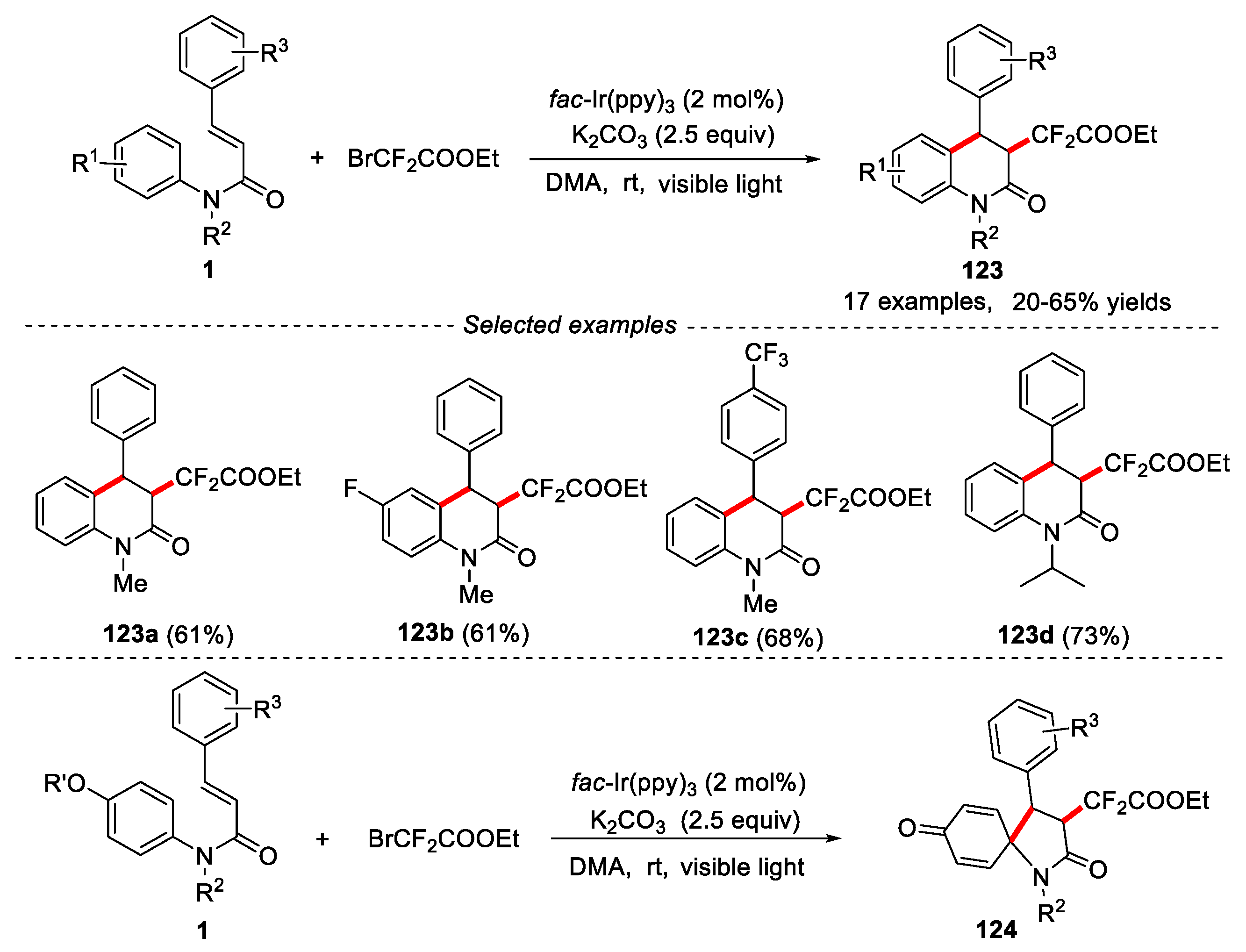

3.2.4. Using BrCF2COOEt as a CF2 sources

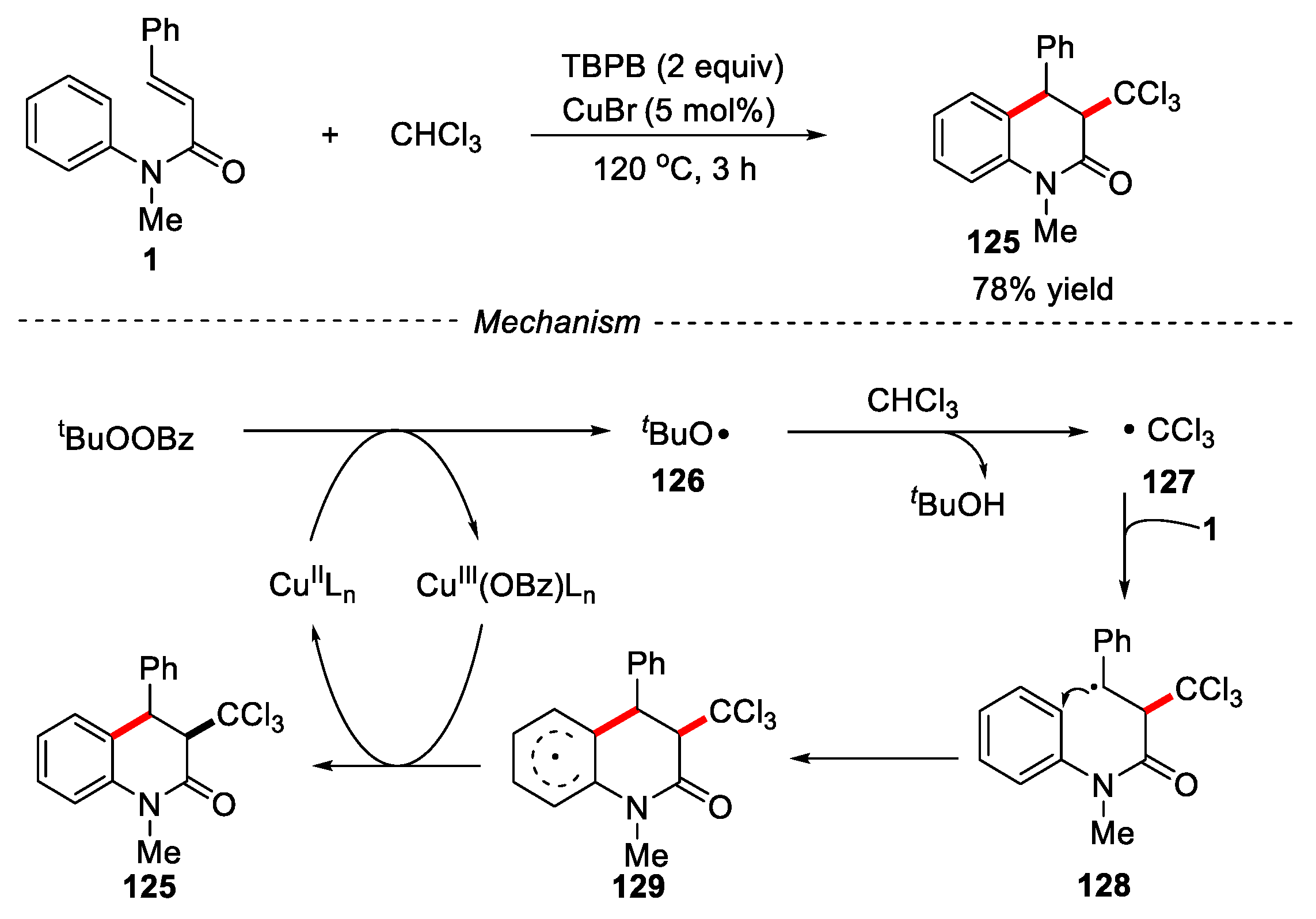

3.3. Synthesis of 3,4-dihydroquinolin-2(1H)-ones using chloroalkyl radicals

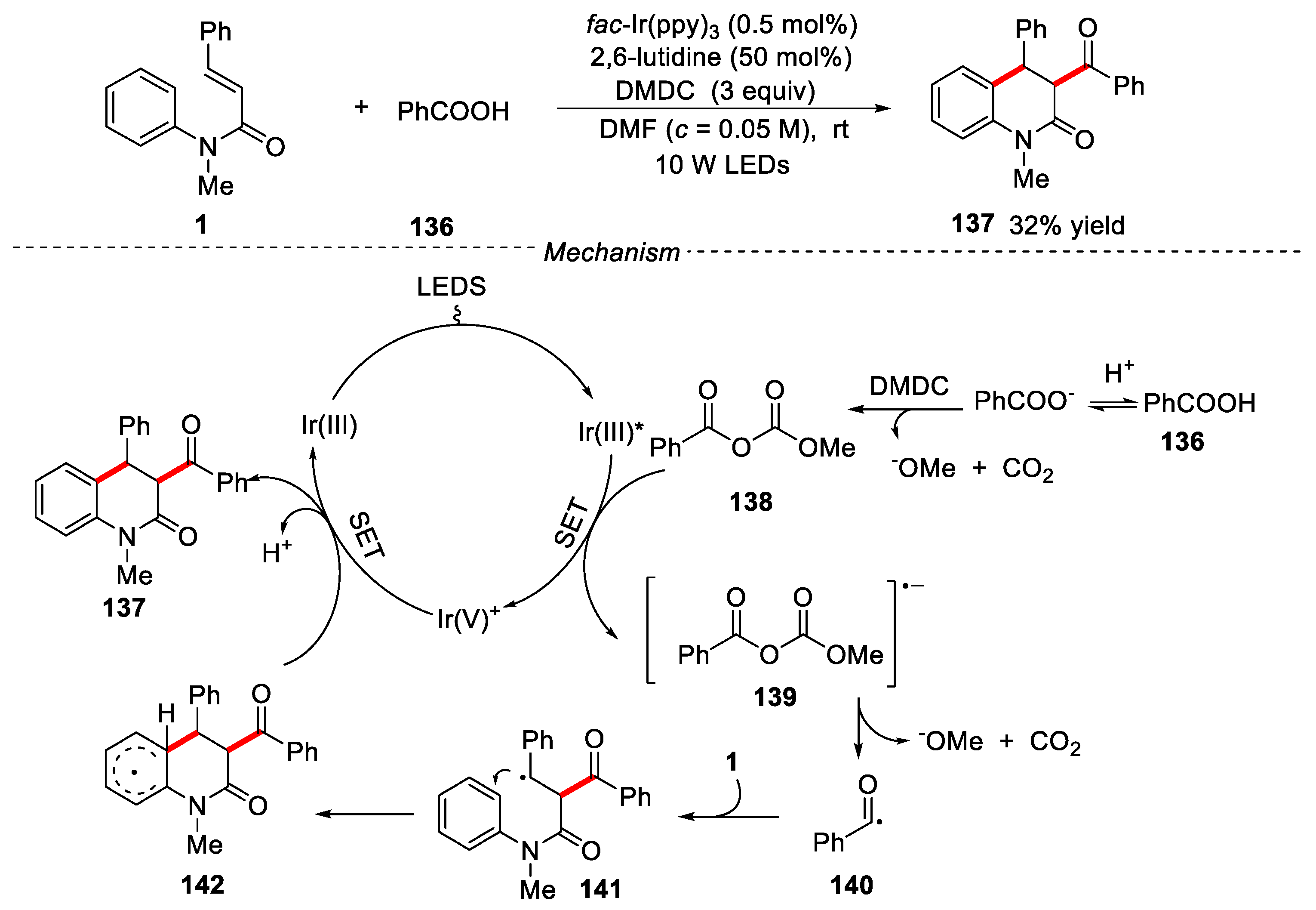

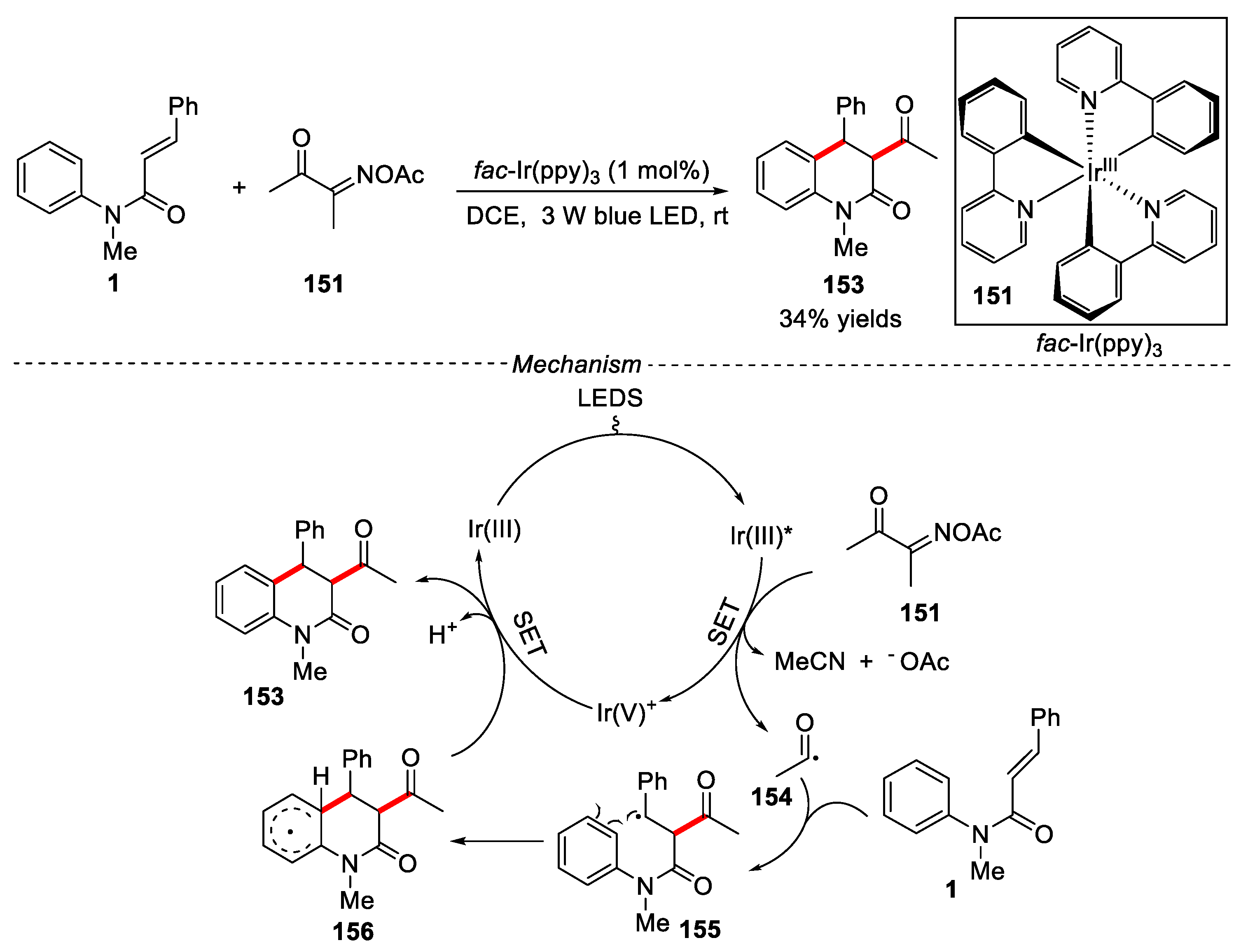

3.4. Synthesis of 3,4-dihydroquinolin-2(1H)-ones using acyl radicals

3.5. Synthesis of 3,4-dihydroquinolin-2(1H)-ones using phosphorus-containing free radicals.

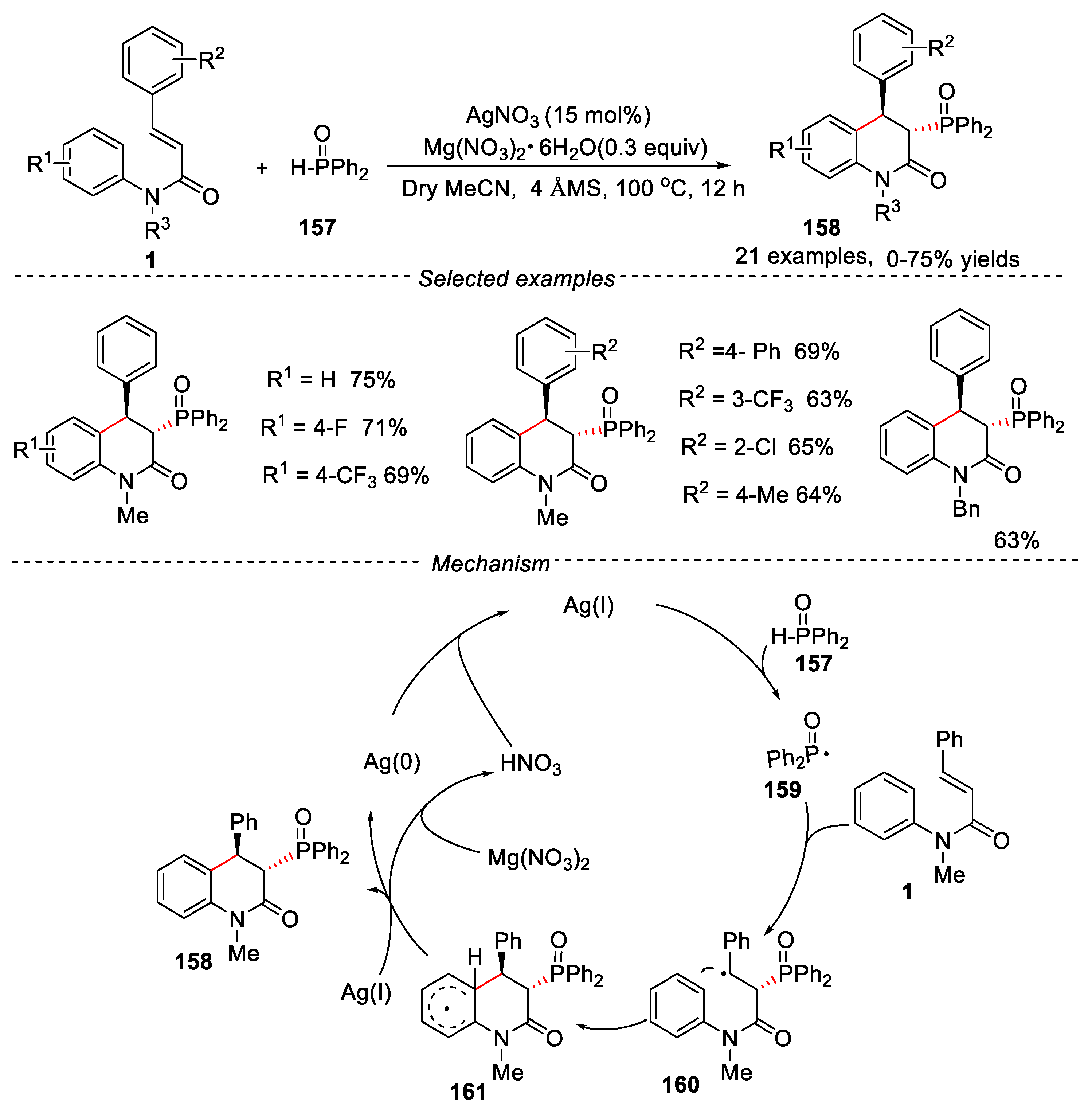

3.6. Synthesis of 3,4-dihydroquinolin-2(1H)-ones using sulphur-containing free radicals

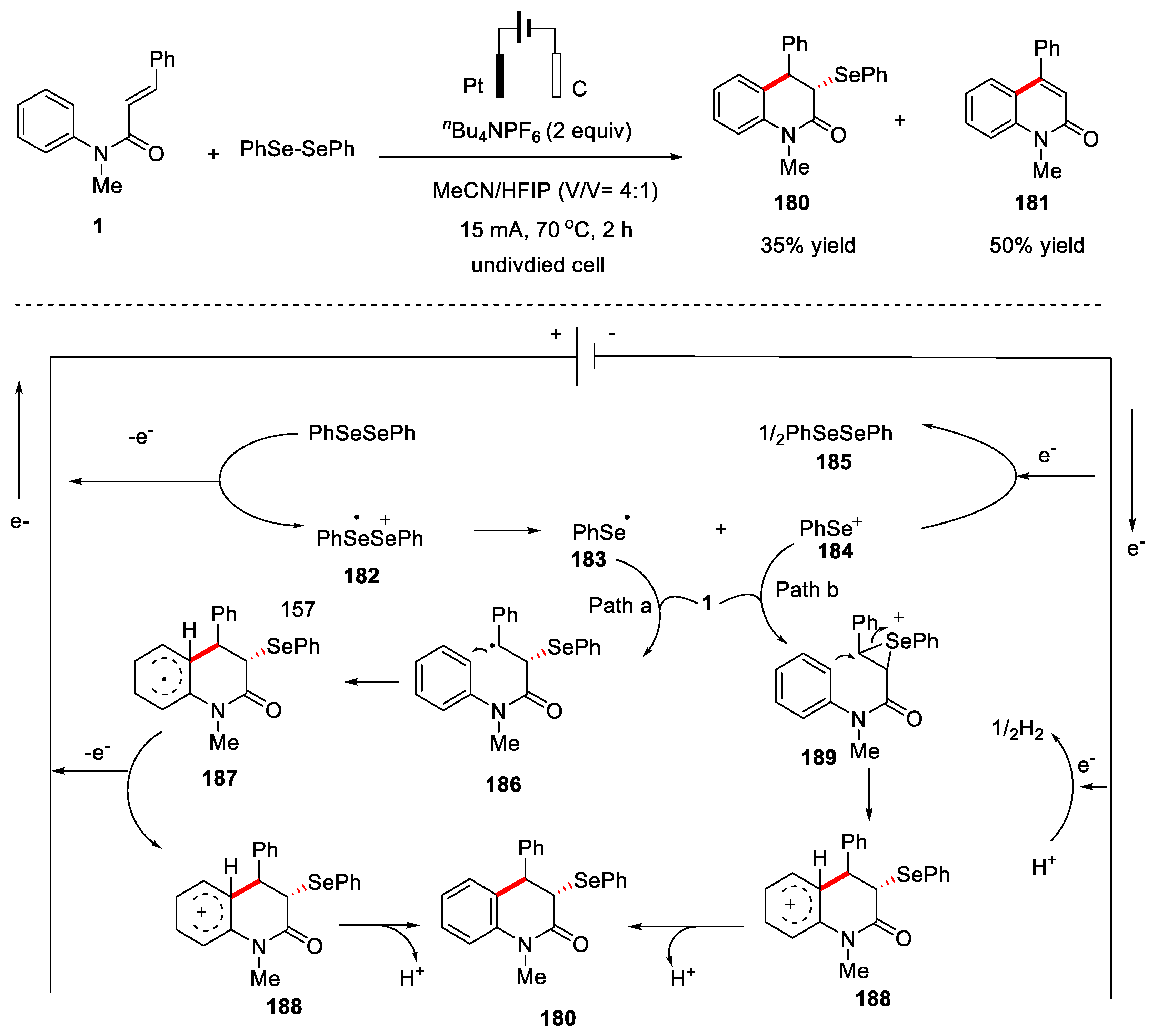

3.7. Synthesis of 3,4-dihydroquinolin-2(1H)-ones using selenyl free radicals

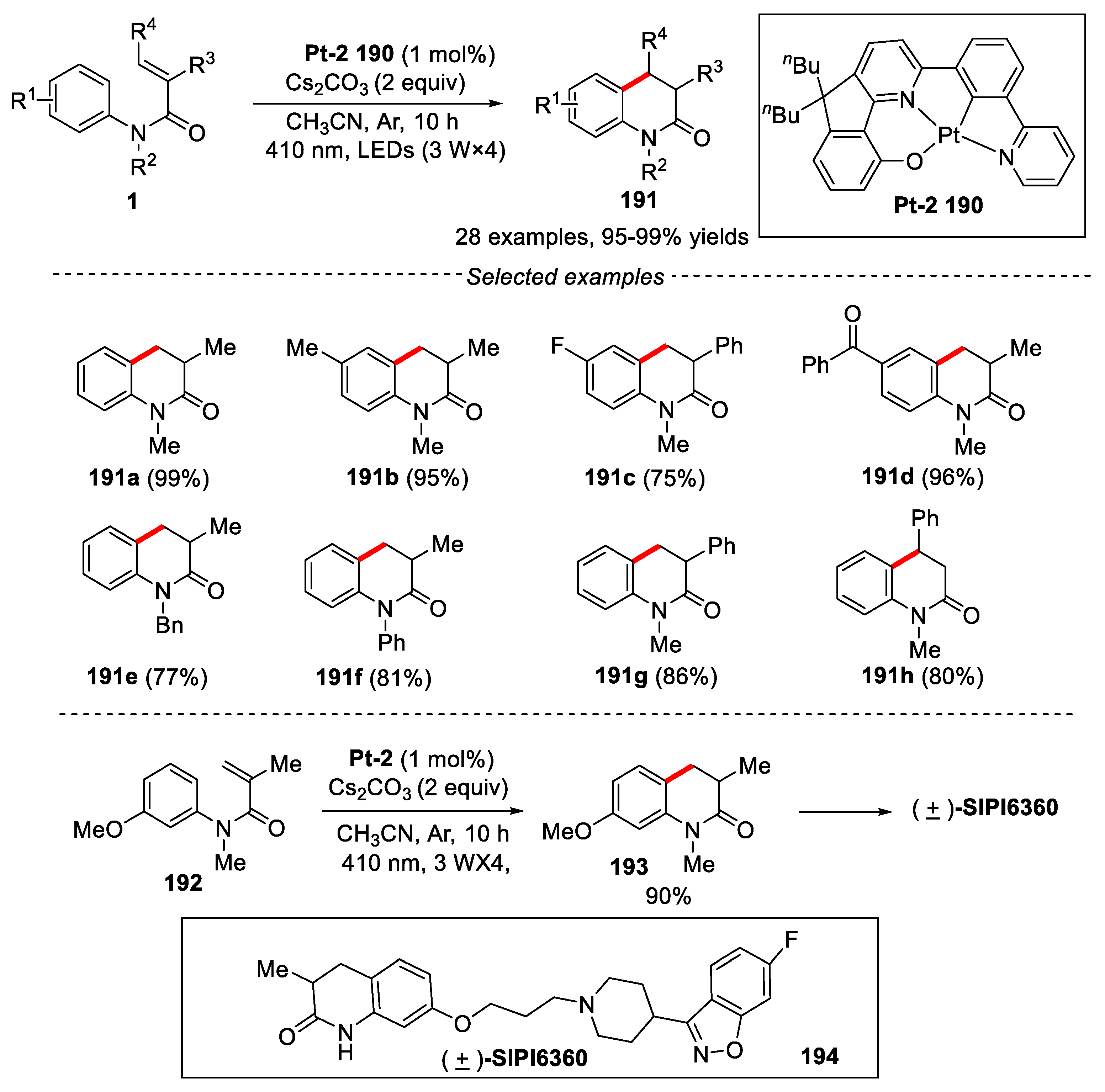

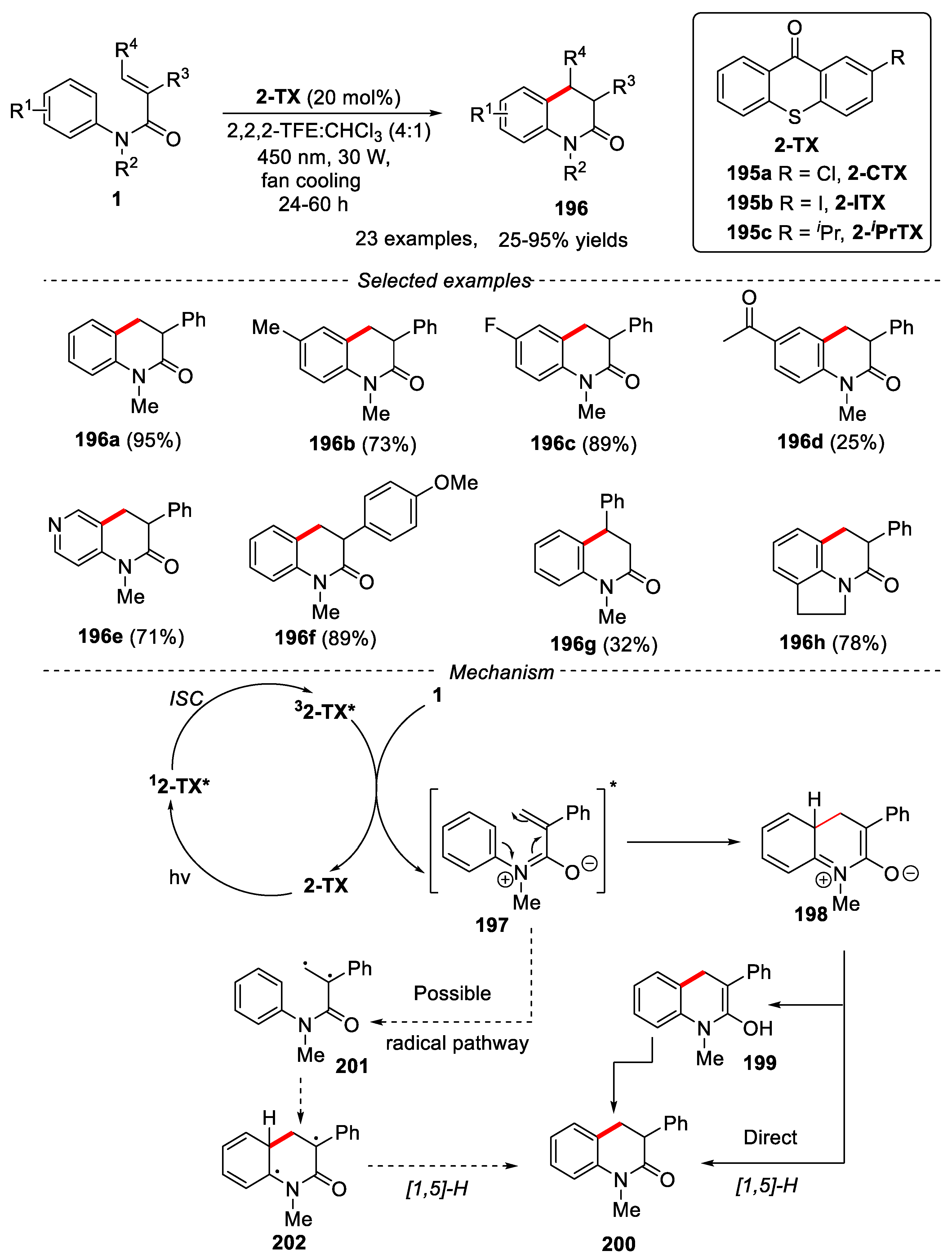

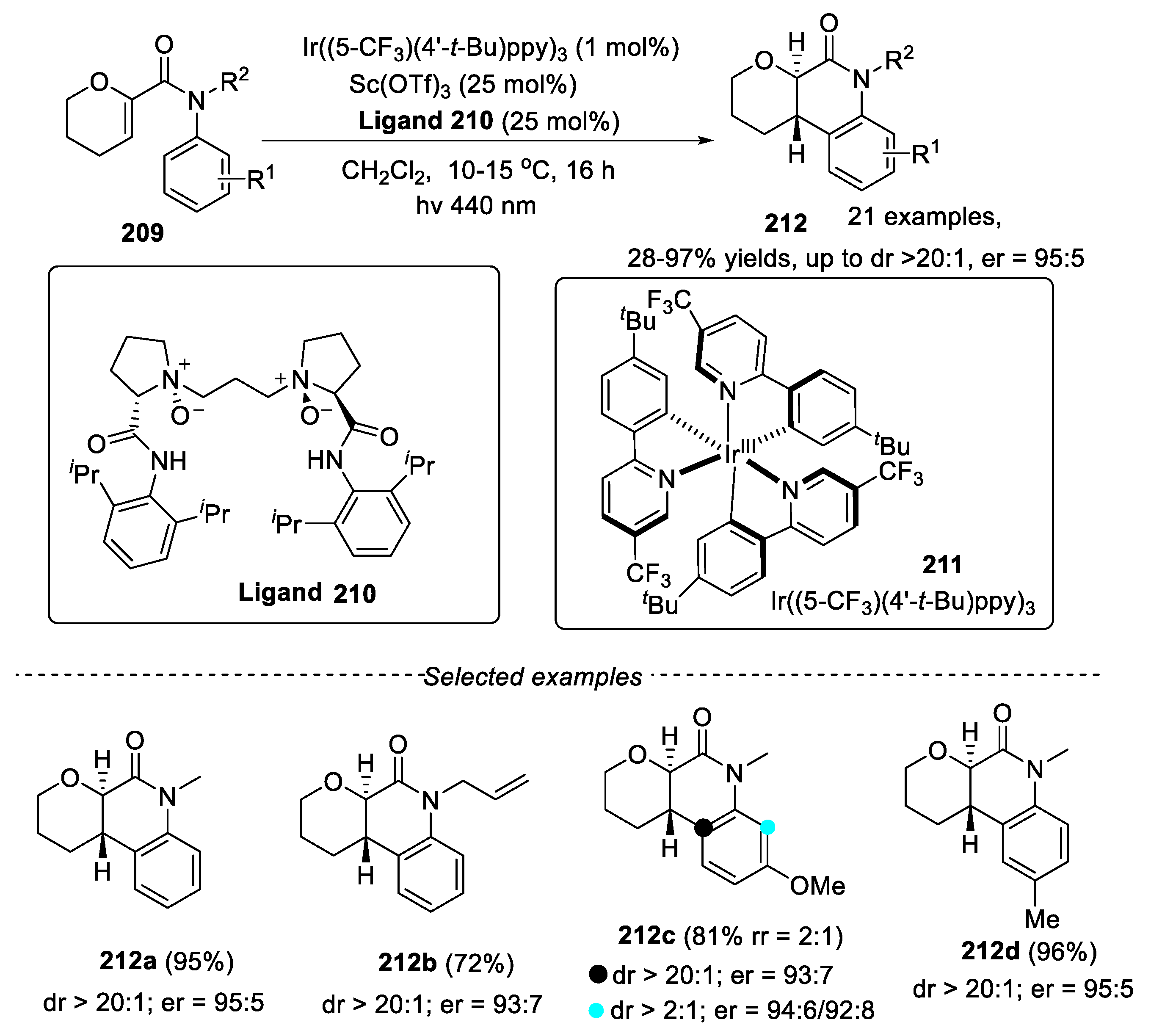

4. Synthesis of 3,4- dihydroquinolin-2(1H)-ones using photoredox cyclization

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gao, X.-H.; Fan, Y.-Y.; Liu, Q.-F.; Cho, S.-H.; Pauli, G. F.; Chen, S.-N.; Yue, J.-M. Unprecedented dimeric quinoline alkaloids with antimycobacterial activity from melodinus suaveolens. Org. Lett., 2019, 21, 7065–7068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.; McHugh, R. J.; Cordova, B. C.; Klabe, R. M.; Bacheler, L. T.; Erickson-Viitanen, S.; Rodgers, J. D. Synthesis and evaluation of novel quinolinones as HIV-1 reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett., 2001, 11, 1943–1945. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ito, C.; Itoigawa, M.; Otsuka, T.; Tokuda, H.; Nishino, H.; Furukawa, H. Constituents of boronia pinnata. J. Nat. Prod., 2000, 63, 1344–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Q.; Yin, L.; Hartmann, R. W. Selective dual inhibitors of CYP19 and CYP11B2: targeting cardiovascular diseases hiding in the shadow of breast cancer. J. Med. Chem., 2012, 55, 7080–7089. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Uchida, R.; Imasato, R.; Shiomi, K.; Tomoda, H.; Omura, S. Yaequinolones J1 and J2, novel insecticidal antibiotics from penicillium sp. FKI-2140. Org. Lett., 2005, 7, 5701–5704. [Google Scholar]

- Beadle, C. D.; Boot, J.; Camp, N. P.; Dezutter, N.; Findlay, J.; Hayhurst, L.; Masters, J. J.; Penariol, R.; Walter, M. W. 1-Aryl-3,4-dihydro-1H-quinolin-2-one derivatives, novel and selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett., 2015, 15, 4432–4437. [Google Scholar]

- François, X. F.; Jérôme, C.; Cécile, Z.; Eric, F. Preparation of 2-quinolones by sequential Heck reduction–cyclization (HRC) reactions by using a multitask palladium catalyst. Chem. Eur. J., 2009, 15, 7238–7245. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuritani, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Kawasaki, M.; Mase, T. Novel approach to 3,4-dihydro-2(1H)-quinolinone derivatives via cyclopropane ring expansion. Org. Lett., 2009, 11, 1043–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsubusaki, T.; Nishino, H. Manganese(III)-mediated facile synthesis of 3,4-dihydro-2(1H)-quinolinones: selectivity of the 6-endo and 5-exo cyclization. Tetrahedron, 2009, 65, 9448–9459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joachim, H.; Ho, Y. L.; Stephen, P. M.; Adam, N.; Rachel, J. S.; Amanda, J. C.; David, H.; Gordon, G. W. Convergent synthesis of dihydroquinolones from o-aminoarylboronates. Tetrahedron, 2009, 65, 9002–9007. [Google Scholar]

- Fujita, K.; Takahashi, Y.; Owaki, M.; Yamamoto, K.; Yamaguchi, R. Synthesis of five-, six-, and seven-membered ring lactams by Cp*Rh complex-catalyzed oxidative N-heterocyclization of amino alcohols. Org. Lett., 2004, 6, 2785–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, J. T.M.; Santos, M. S.; Pissinati, E. F.; da Silva, G. P.; Paixo, M. W. Recent advances on photoinduced cascade strategies for the synthesis of N-heterocycles. Chem. Rec., 2021, 21, 2666–2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.-H.; Li,Y. ; Li, J.-H.; Xiang, J.-N.; Deng, W. Recent advances in radical-mediated [2+2+m] annulation of 1,n-enynes. Sci China Chem, 2019, 62, 1463–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mieriņa, I.; Jure, M.; Stikute, A. Synthetic approaches to 4-(het)aryl-3,4-dihydroquinolin-2(1H)-ones. Chem. Heterocycl. Com., 2016, 52, 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, J. M.; Tatipaka, H. B.; McGuffin, S. A.; Chennamaneni, N. K.; Karimi, M.; Arif, J.; Verlinde, C. L. M. J.; Buckner, F. S.; Gelb, M. H. Second generation analogues of the cancer drug clinical candidate tipifarnib for anti-chagas disease drug discovery. J. Med. Chem., 2010, 53, 3887–3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safina, L. Y.; Selivanova, G. A.; Koltunov, K. Y.; Shteingarts, V. D. Synthesis of polyfluorinated 4-phenyl- 3,4-dihydroquinolin-2-ones and quinolin-2-ones via superacidic activation of N-(polyfluorophenyl)cinnamamides. Tetrahedron Lett., 2009, 50, 5245–5247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Foresee, L. N.; Tunge, J. A. Trifluoroacetic acid-mediated hydroarylation: synthesis of dihydrocoumarins and dihydroquinolones. J. Org. Chem., 2005, 70, 2881–2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, D.; Xin, X.; Zhang, R.; Zhou, F.; Dong, D. PPA-Mediated C-C bond formation: a synthetic route to substituted indeno[2,1-c]quinolin-6(7H)-ones. Org. Lett 2013, 15, 776–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Han, S.; Jin, G. H.; Lee, H. J.; Kim, W.-Y.; Ryu, J.-H.; Jeon, R. Synthesis and anticancer activity of aminodihydroquinoline analogs: identification of novel proapoptotic agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett., 2013, 23, 3976–3978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, A. Synthesis of 4-aryl-3-arylthio-3,4-dihydroquinolin-2(1H)-ones via cyclization of N-arylcinnamamides with N-thiosuccinimides. Synlett, 2017, 49, 575–582. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.-Z.; Liu, L.; Gou, Q.; Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Li, W.-T.; Luo, F.; Yuan, M.; Chen, T.; He, W.-M. Synthesis of hydroxyl-containing oxindoles and 3,4-dihydroquinolin-2-ones through oxone-mediated cascade arylhydroxylation of activated alkene. Green Chem., 2020, 22, 8369–8374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.-F.; Zhu, S.-L.; Chen, C.; Wang, H.; Liang, Y.-M. Silver-catalyzed decarboxylative addition/cyclization of activated alkenes with aliphatic carboxylic acids. J. Org.Chem., 2016, 81, 1277–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, W.-P.; Wang, J.-T.; Yang, L.-R.; Yuan, J.-W.; Xiao, Y.-M.; Mao, P. and Qu, L.-B. Silver-catalyzed radical tandem cyclization for the synthesis of 3,4-disubstituted dihydroquinolin-2(1H)-ones. Org. Lett., 2014, 16, 204–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Z.; and Du, D.-M. FeCl2-catalyzed decarboxylative radical alkylation/cyclization of cinnamamides: access to dihydroquinolinone and pyrrolo[1,2-a]indole analogues. J. Org. Chem., 2018, 83, 5149–5159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuentragool, P.; Kurandina, D.; Gevorgyan, V. Catalysis with palladium complexes photoexcited by visible light. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 11586–11598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.-J.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, G.; Liu, H.; Yu, D.-G. Palladium-catalyzed radical-type transformations of alkyl halides. Chin. J. Org. Chem., 2017, 37, 1322–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.-H.; Wei, W.-T.; Zhou, M.-B.; Song, R.-J.; Li, J.-H. Palladium-catalyzed oxidative difunctionalization of alkenes with α-carbonyl alkyl bromides initiated through a Heck-type insertion: a route to indolin-2-ones. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 2014, 53, 6650−6654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Guo, L.-N.; Duan, X.-H. Palladium-catalyzed alkylarylation of acrylamides with unactivated alkyl halides. J. Org. Chem., 2016, 81, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.-J.; Cao, G.-M.; Zhang, Z.-P.; Yu, D.-G. Visible light-induced palladium-catalysis in organic synthesis. Chem. Lett., 2019, 48, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.-H.; Wei, W.-T.; Zhou, M.-B.; Song, R.-J.; Li, J.-H. Palladium-catalyzed oxidative difunctionalization of alkenes with alpha-carbonyl alkyl bromides initiated through a Heck-type insertion: a route to indolin-2-ones. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 2014, 53, 6650–6654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Wei, J.; Huang, X.; Song, J.; Zhang, J. Photoinduced palladium-catalyzed intermolecular radical cascade cyclization of N-arylacrylamides with unactivated alkyl bromides. Org. Lett., 2021, 23, 5635–5635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciesielski, J.; Dequirez, G.; Retailleau, P.; Gandon, V.; Dauban, P. Rhodium-catalyzed alkene difunctionalization with nitrenes. Chem. – Eur. J., 2016, 22, 9338–9347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Wang, C. Rhenium-catalyzed alkylarylation of alkenes with PhI(O2CR)2 via decarboxylation to access indolinones and dihydroquinolinon. Org. Chem. Front., 2020, 7, 3234–3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.-J.; He, Q.; and Yang, L. Metal-free oxidative decarbonylative coupling of aromatic aldehydes with arenes: direct access to biaryls. Chem. Commun., 2015, 51, 5925–5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, R.-J.; Kang, L.; Yang, L. Metal-free oxidative decarbonylative coupling of aliphatic aldehydes with azaarenes: successful Minisci-type alkylation of various heterocycles. Adv. Synth. Catal., 2015, 357, 2055–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.-X.; Luan, X.-Q.; Xie, Z.-Y.; Yang, L.; Pei, Y. Fe-catalyzed decarbonylative cascade reaction of N-aryl cinnamamides with aliphatic aldehydes to construct 3,4-dihydroquinolin-2(1H)-ones. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 5262–5268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Luo, Z.; Liu, C.-F.; Wang, X. ; Deng, L; Gao. Jie. Metal-free synthesis of 3,4-dihydroquinolin-2(1H)-ones via cascade oxidative decarbonylative radical alkylation/cyclization of cinnamamides with aliphatic aldehydes. Asian J. Org. Chem., 2019, 8, 1903–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.-Y.; Zhao, Q.-Q.; Chen, J.; Xiao, W.-J.; Chen, J.-R. When light meets nitrogen-centered radicals: from reagents to catalysts. Acc. Chem. Res., 2020, 53, 1066−1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, J.-Y.; Gao, P.; Xu, S.-L; Guo, L.-N. Copper-catalyzed redox-neutral cyanoalkylarylation of activated alkenes with cyclobutanone oxime esters. J. Org. Chem., 2018, 83, 1046–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanzone, J. R.; Hu, C. T.; Woerpel, K. A. Uncatalyzed carboboration of seven-membered-ring trans-alkenes: formation of air-stable trialkylboranes. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2017, 139, 8404–8407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darses, S.; Genet, J. P. Potassium Organotrifluoroborates: new perspectives in organic synthesis. Chem. Rev., 2008, 108, 288–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiple, I. B.; Su, S.; Rodriguez, R. A.; Gianatassio, R.; Fujiwara, Y.; Sobel, A. L.; Baran, P. S. Direct C-H arylation of electron deficient heterocycles with arylboronic acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2010, 132, 13194–13196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, A.; Zhang, L.; Tan, R. X.; Liu, Z.-Q. Molecular oxygen-promoted general and site-specific alkylation with organoboronic acid. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 14489–14497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

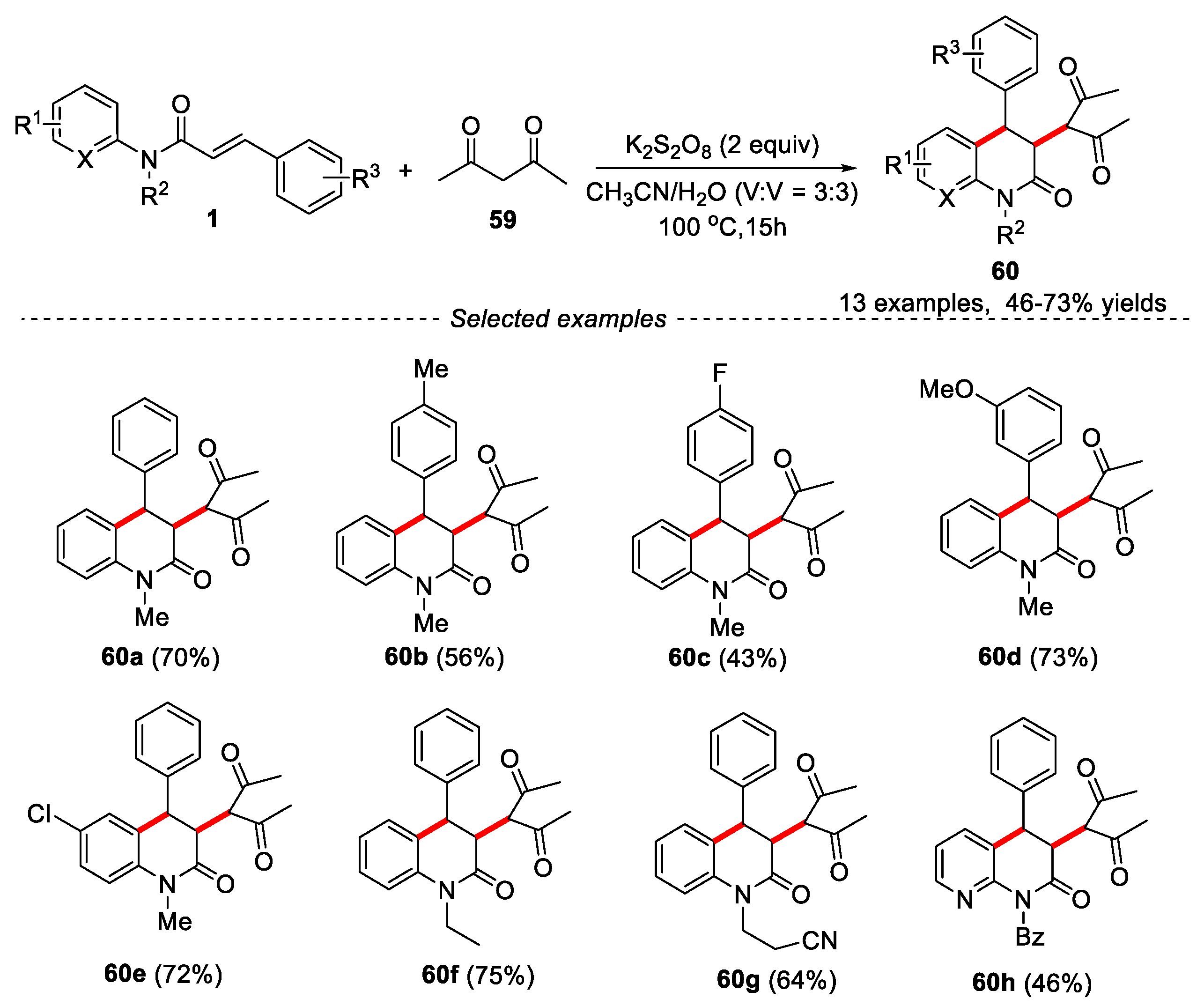

- Wang, H.; Sun, B.; Yang, J.; Wang, J.; Mao, P.; Yang, L.; Mai, W. The synthesis of 3,4-disubstituted dihydroquinolin-2(1H)-one under metal free conditions in aqueous solution. J. Chem. Res., 2014, 38, 542–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

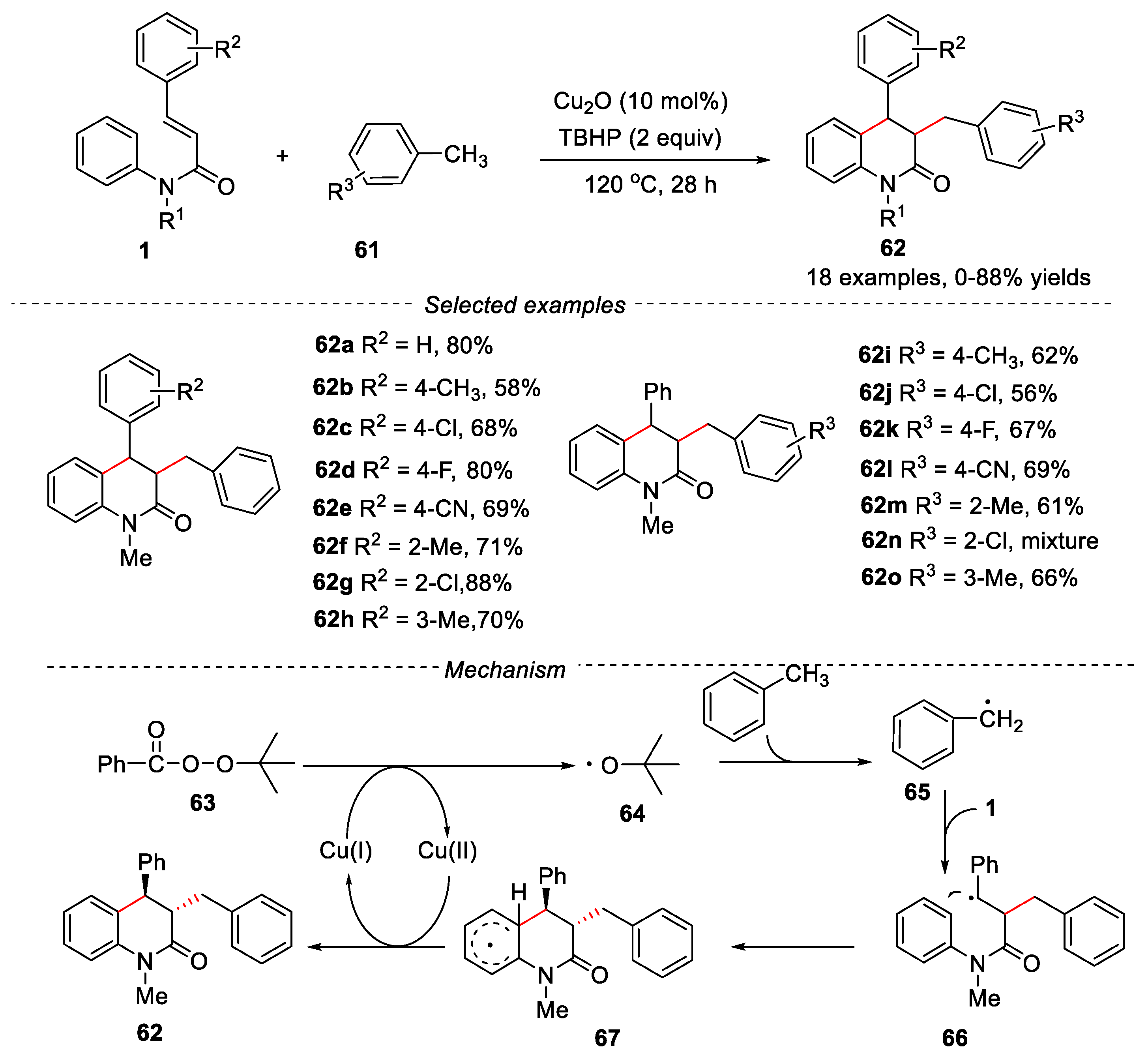

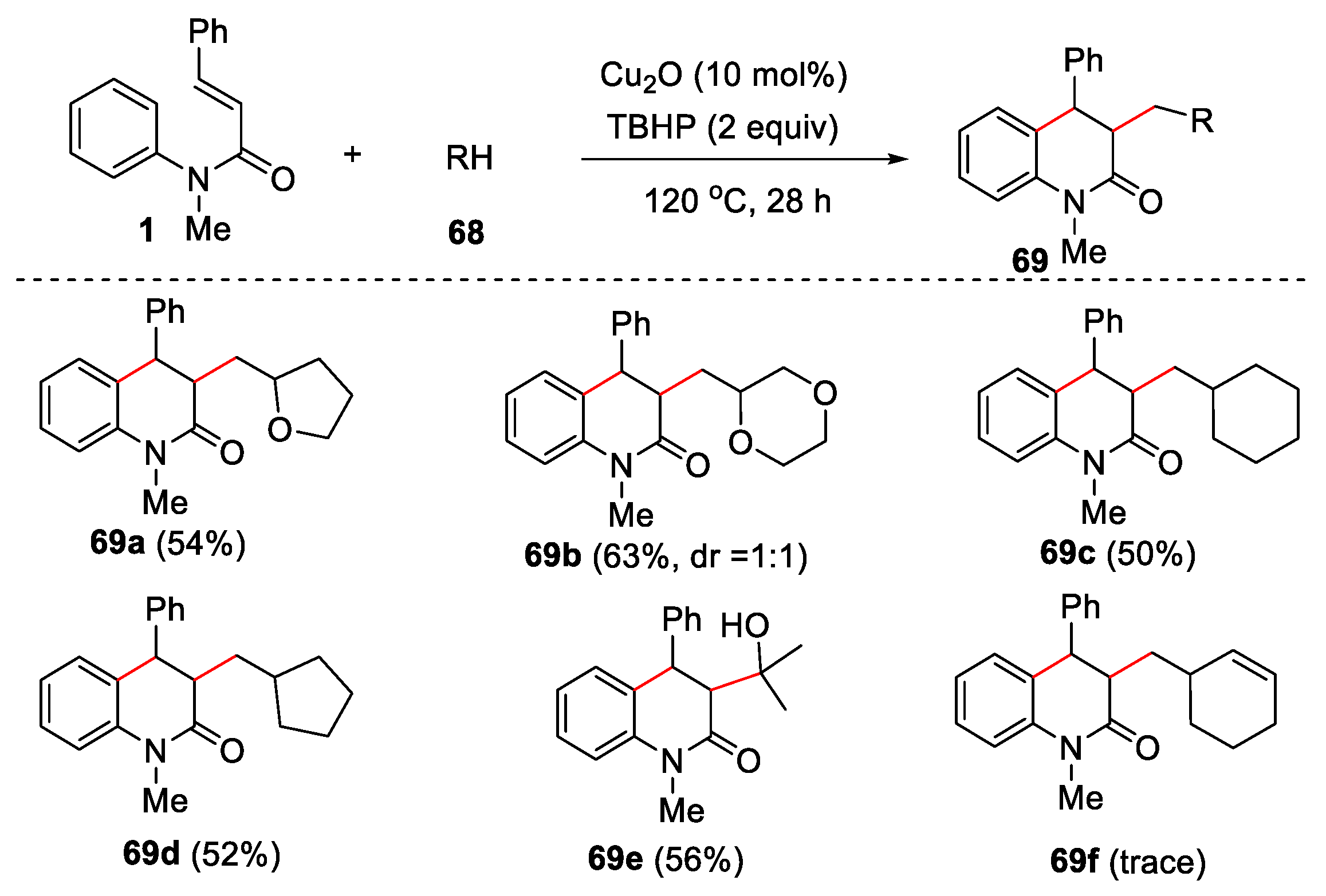

- Zhou, S.-L.; Guo, L.-Na.; Wang, S.; Duan, X.-H. Copper-catalyzed tandem oxidative cyclization of cinnamamides with benzyl hydrocarbons through cross-dehydrogenative coupling. Chem. Commun., 2014, 50, 3589−3591. [Google Scholar]

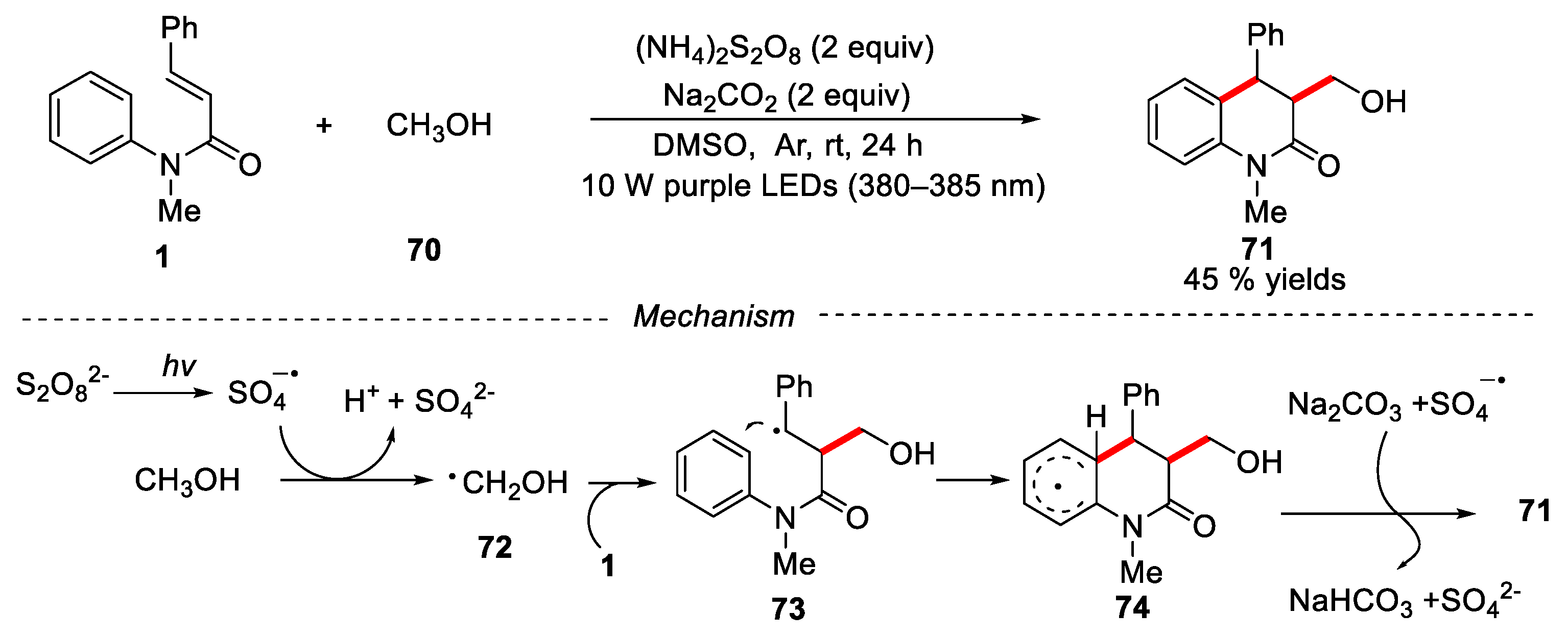

- Xu, D.; Yu, Y.; Huang, F.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, W. Photo-induced C(sp3)-H functionalization for the synthesis of 3,3-disubstituted oxindoles. Asian J. Org. Chem., 2022, 11, e202200131 (1-5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

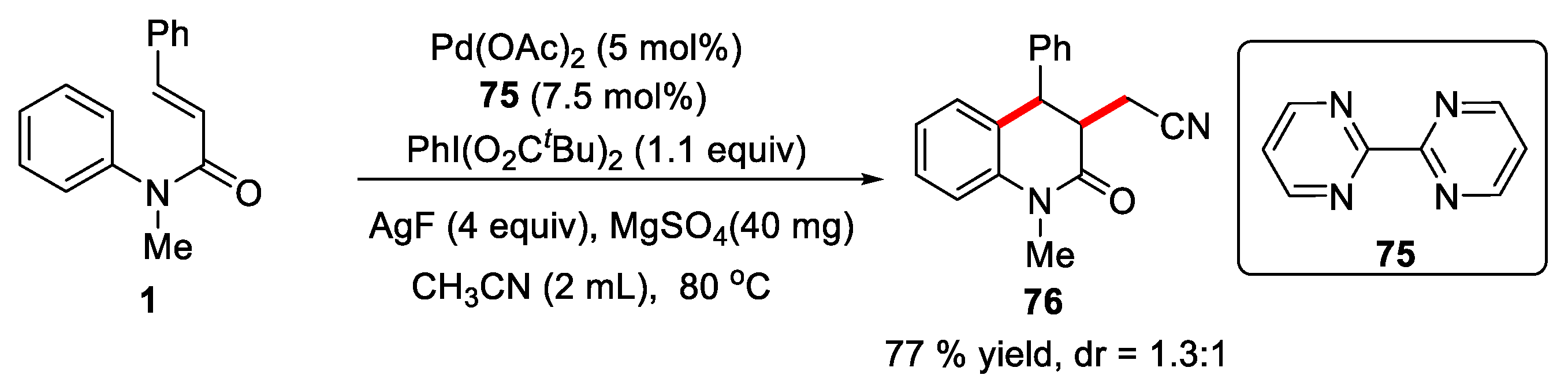

- Wu, T.; Mu, X.; Liu, G. Palladium-catalyzed oxidative arylalkylation of activated alkenes: dual C-H bond cleavage of an arene and acetonitrile. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 2011, 50, 12578–12581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

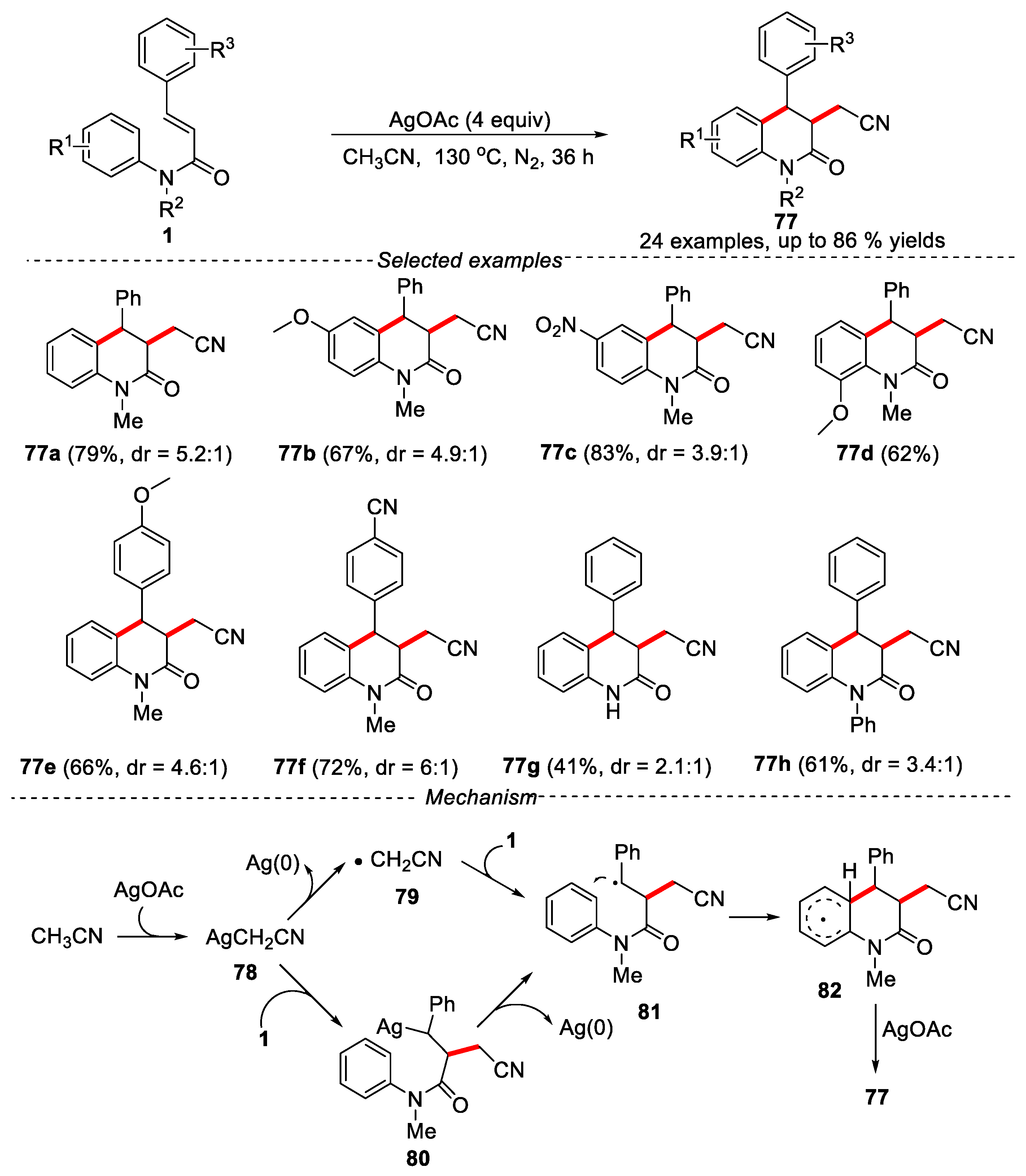

- Wang, K.; Chen, X.; Yuan, M.; Yao, M.; Zhu, H.; Xue, Y.; Luo, Z.; Zhang, Y. Silver-mediated cyanomethylation of cinnamamides by direct C(sp3)−H functionalization of acetonitrile. J. Org. Chem 2018, 83, 1525–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

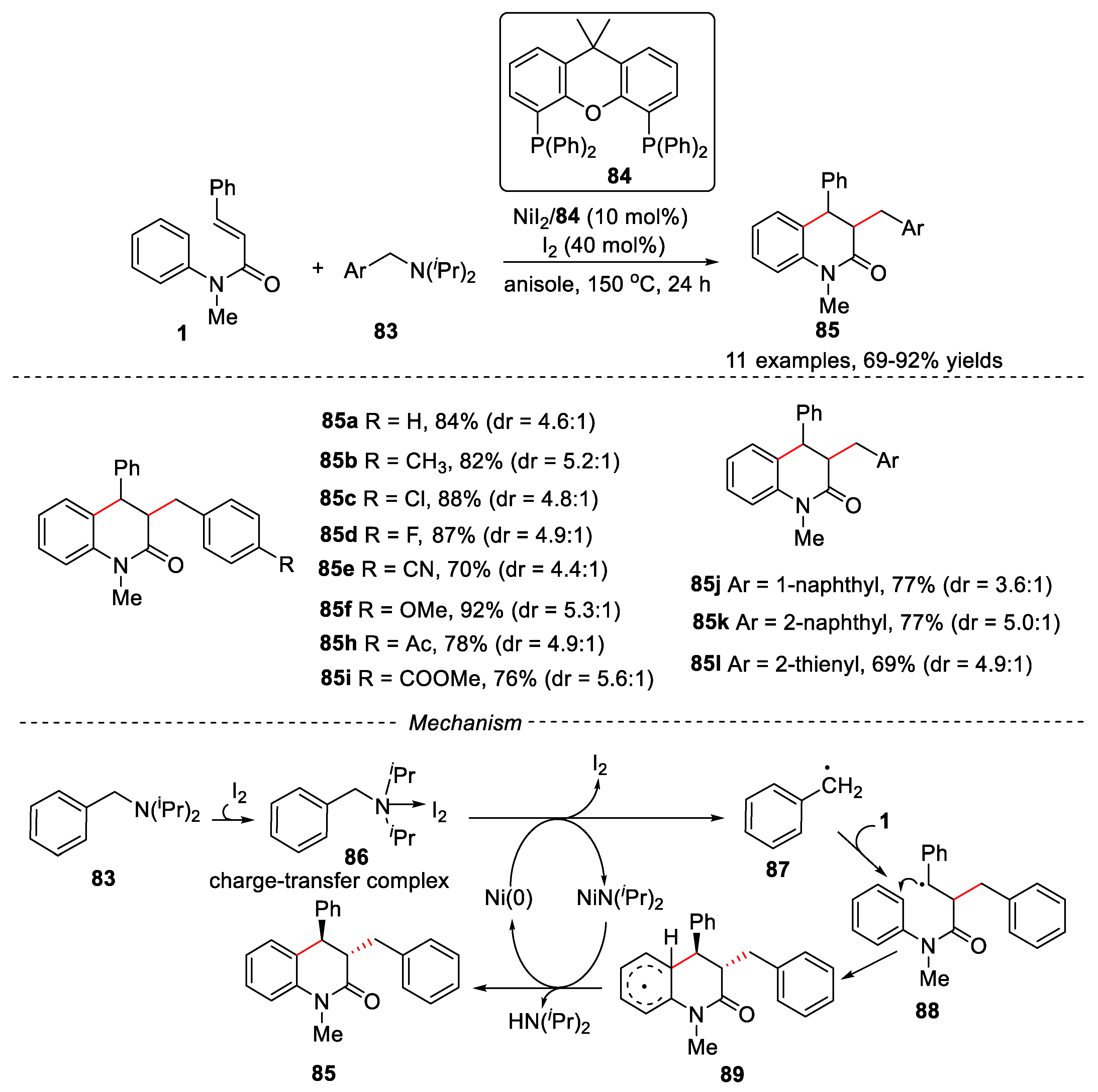

- Yu, H.; Hu, B.; Huang, H. Nickel-catalyzed alkylarylation of activated alkenes with benzylamines via C-N bond activation. Chem. –Eur. J., 2021, 24, 7114−7117. [Google Scholar]

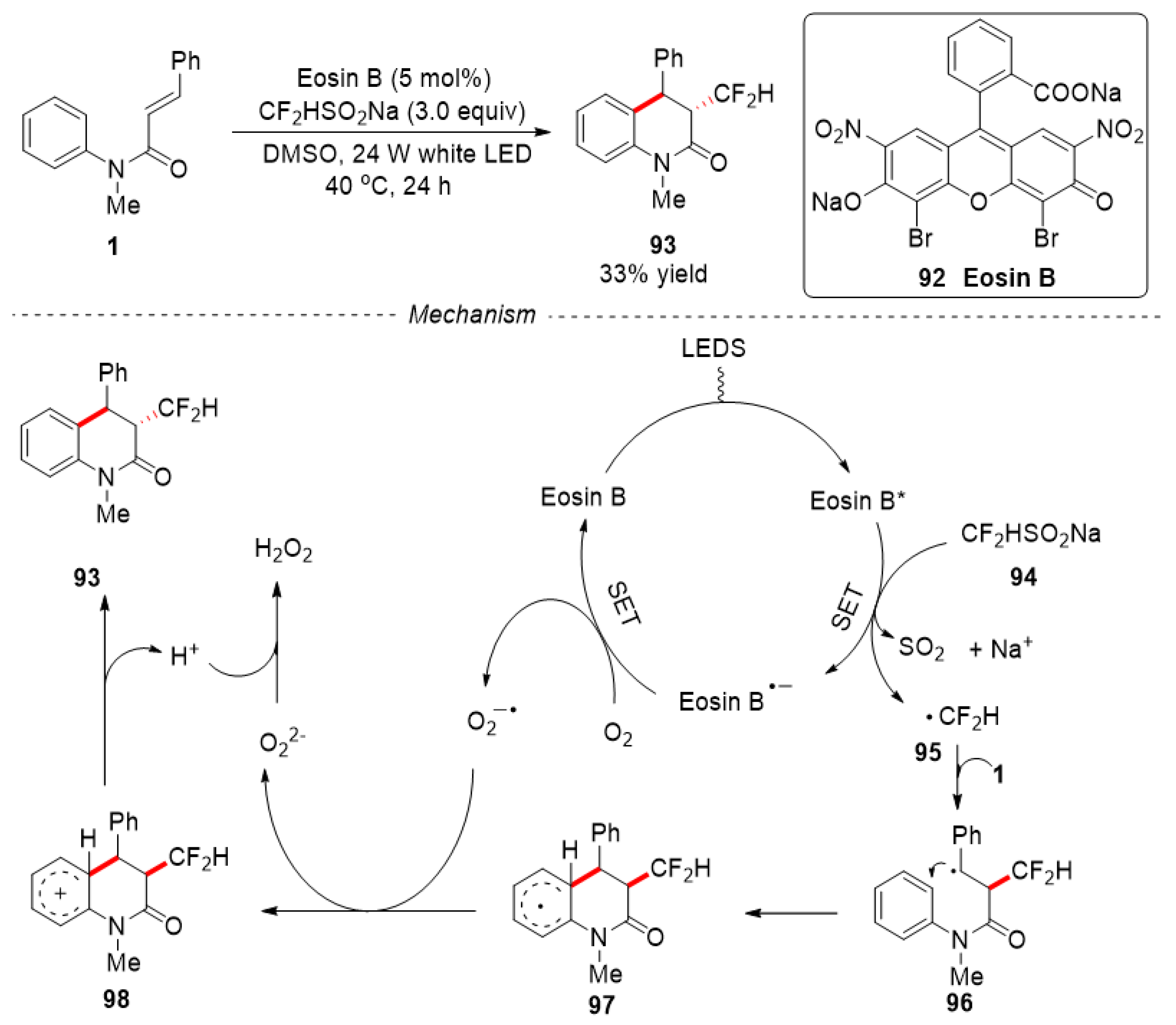

- Lu, M.-J.; Liu, Z.-J.; Zhang, J.-W.; Tian, Y.; Qin, H.-G.; Huang, M.-Q.; Hua, S.-R.; Cai, S.-Y. Synthesis of oxindoles through trifluoromethylation of N-aryl acrylamides by photoredox catalysis. Org.Biomol. Chem., 2018, 16, 6564–6568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Dai, P.; Yan, Z.; Wang, Y.; Shao, J.; Wu, Y.; Deng, C.; Zhang, W. Metal-free, visible-light-induced radical trifluoromethylation/cyclization of N-benzamides with CF3SO2Na to synthesize CF3-containing isoquinoline-1,3-diones. Chemistryselect, 2019, 4, 10329–10333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, S.; Wang, S.; Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, W.; Deng, C. Synthesis of CF2H-containing isoquinoline-1,3-diones through metal-free, visible-light and air-promoted radical difluoromethylation/cyclization of N-benzamides. Tetrahedron 2021, 79, 131822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

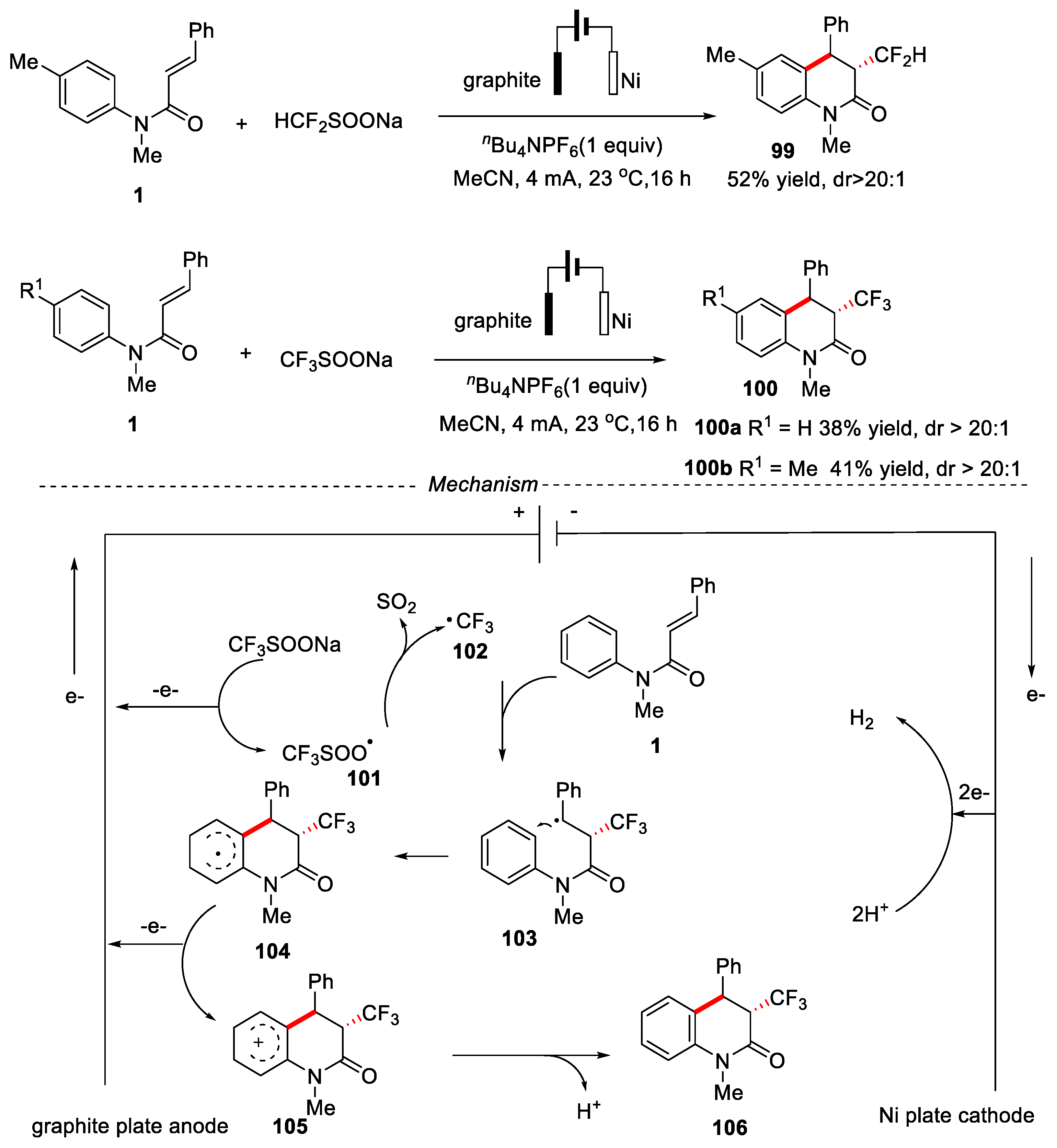

- Ruan, Z.; Huang, Z.; Xu, Z.; Mo, G.; Tian, X.; Yu, X.-Y.; Ackermann, L. Catalyst-free, direct electrochemical tri- and difluoroalkylation/cyclization: access to functionalized oxindoles and quinolinones. Org. Lett., 2019, 21, 1237−1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Lu, Y.; Sheng, H.; Zhang, C.-S.; Su, X.-D.; Wang, Z.-X.; Chen, X.-Y. Visible-light-induced selective photolysis of phosphonium iodide salts for monofluoromethylations. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 2021, 60, 25477–25484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.-Y.; Huang, J.; Sun, K.; He, W.-M. Recent advances in transition-metal-free trifluoromethylation with Togni’s reagents. Org. Chem. Front., 2022, 9, 1152–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.-M.; Bai, W.; Wang, S.-H.; Yang, B.-M.; Tu, Y.-Q.; Zhang, F.-M. Copper-catalyzed tandem trifluoromethylation/ semipinacol rearrangement of allylic alcohols, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 2013, 52, 9781–9785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Mück-Lichtenfeld, C.; Daniliuc, C. G.; Studer, A. 6-Trifluoromethyl-phenanthridines through radical trifluoromethylation of isonitriles. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 2013, 52, 10792–10795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Han, G.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Q. Copper-catalyzed aryltrifluoromethylation of N-phenylcinnamamides: access to trifluoromethylated 3,4-dihydroquinolin-2(1H)-ones. Adv. Synth. Catal., 2015, 357, 2464–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Yang, C.; Gao, G.-L.; Zheng, L.; Xia, W. Visble-light induced trifluoromethylation of N-arylcinnamamides for the synthesis of CF3-containing 3,4-disubstituted dihydroquinolinones and 1-azaspiro[4.5]decanes. Org. Lett., 2015, 14, 3478–3481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, J. D.; Tucker, J. W.; Konieczynska, M. D.; Stephenson, C. R. J. Intermolecular atom transfer radical addition to olefins mediated by oxidative quenching of photoredox catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2011, 133, 4160–4163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallentin, C. J.; Nguyen, J. D.; Finkbeiner, P.; Stephenson, C. R. J. Visible light-mediated atom transfer radical addition via oxidative and reductive quenching of photocatalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2012, 134, 8875−8884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Xu, P.; Cheng, Y.; Zhu, C. Visible-light-induced radical tandem aryldifluoroacetylation of cinnamamides: access to difluoroacetylated quinolone-2-ones and 1-azaspiro[4.5]decanes. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2015, 357, 3057–3063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C. W.; Lee, P. Y.; and Yu, W. Y. Copper-catalyzed cross-dehydrogenative coupling of N-arylacrylamides with chloroform using tert-butyl peroxybenzoate as oxidant. Tetrahedron Lett., 2015, 56, 2559–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xu, J.; Gao, Y.; Fang, H.; Tang, G.; Zhao, Y. Cascade arylalkylation of activated alkenes: synthesis of chloroand cyano-containing oxindole. J. Org. Chem., 2015, 80, 2621−2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergonzini, G.; Cassani, C.; Wallentin, C.-J. Acyl radicals from aromatic carboxylic acids by means of visible-light photoredox catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 2015, 54, 14066–14069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, W.-P.; Sun, G.-C.; Wang, J.-T.; Song, G.; Mao, P.; Yang, L.-R.; Yuan, J.-W.; Xiao, Y.-M; Qu, L.-B. Silver-catalyzed radical tandem cyclization: an approach to direct synthesis of 3-acyl-4-arylquinolin-2(1H)-ones. J. Org. Chem., 2014, 79, 8094−8102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Guo, L.-N.; Duan, X.-H. Silver-catalyzed tandem radical acylarylation of cinnamamides in aqueous media. RSC Adv., 2014, 4, 52986–52990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, W.-P.; Wang, J.-T.; Xiao, Y.-M.; Mao, P.; Lu, K. A novel direct synthesis of 3-acyl-4-aryldihydroquinolin-2(1H)-ones via metal-free radical tandem cyclization between N-arylcinnamamides and aldehydes. Tetrahedron, 2015, 71, 8041–8051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, J. C. Functionalised oximes: emergent precursors for carbon-, nitrogen- and oxygen-centred radicals. Molecules, 2016, 21, 63−86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Lei, T.; Chen, B.; Tung, C.-H; Wu, L.-Z. Photocatalytic C−C bond activation of oxime ester for acyl radical generation and application. Org. Lett., 2019, 21, 4153−4158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, H. A.; Guiry, P. J. Recent developments in the application of oxazoline-containing ligands in asymmetric catalysis. Chem. Rev., 2004, 104, 4151–4202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumgartner, T.; Réau, R. Organophosphorus π-conjugated materials. Chem. Rev., 2006, 106, 4681–4727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Gu, Z.; Li, Z.; Pan, C.; Li, W.; Hu, H.; Zhu, C. Silver-catalyzed cascade radical cyclization: a direct approach to 3,4-disubstituted dihydroquinolin-2(1H)-ones through activation of the P−H bond and functionalization of the C(sp2 )−H bond. J. Org. Chem., 2016, 81, 2122−2127. [Google Scholar]

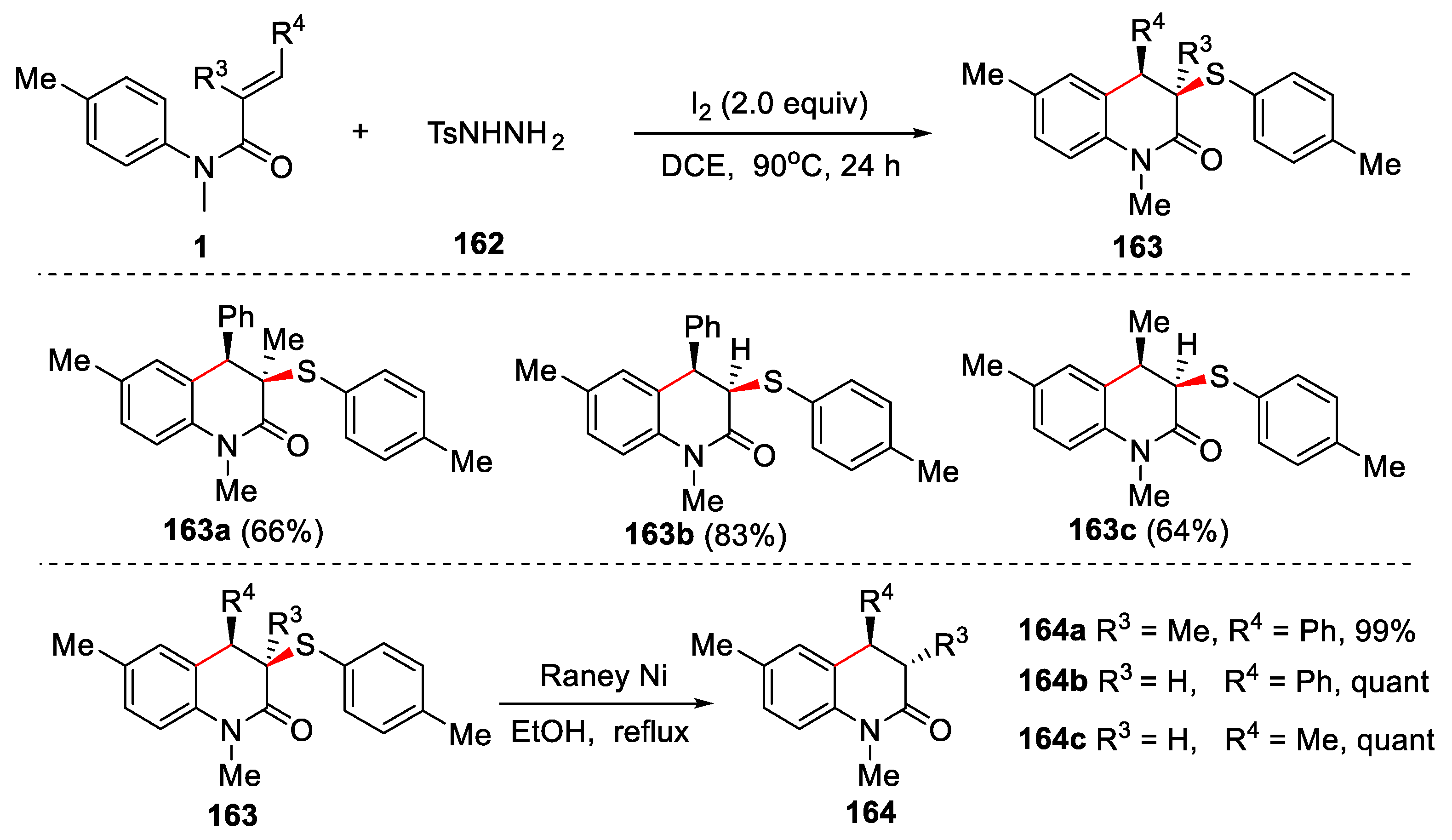

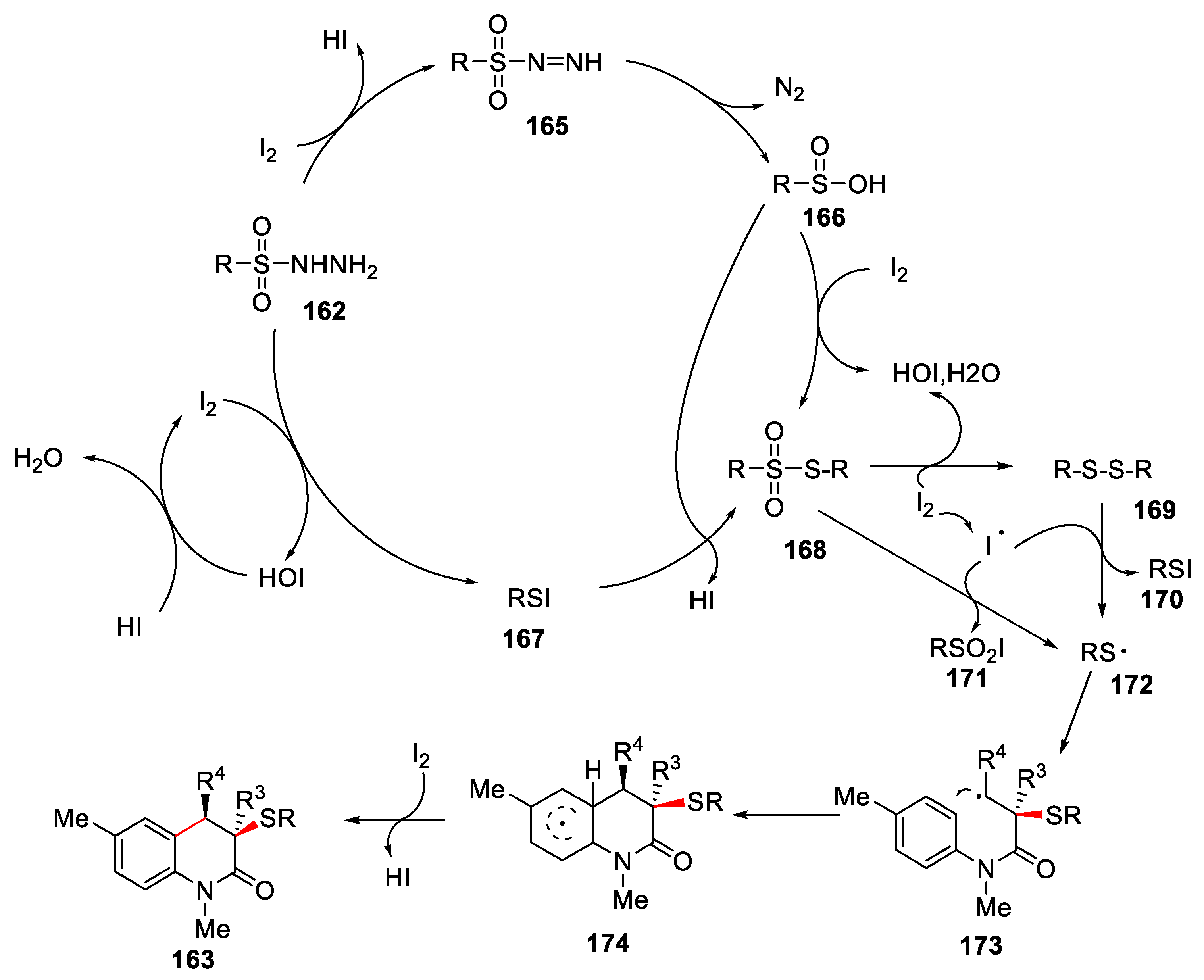

- Wang, F.-X.; Tian, S.-K. Cyclization of N-arylacrylamides via radical arylsulfenylation of carbon−carbon double bonds with sulfonyl hydrazides. J. Org. Chem., 2015, 80, 12697−12703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Rakesh, K. P.; Ravidar, L.; Fang, W.-Y.; Qin, H.-L. Pharmaceutical and medicinal significance of sulfur (SVI)-containing motifs for drug discovery: a critical review. Eur. J. Med. Chem., 2019, 162, 679−734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

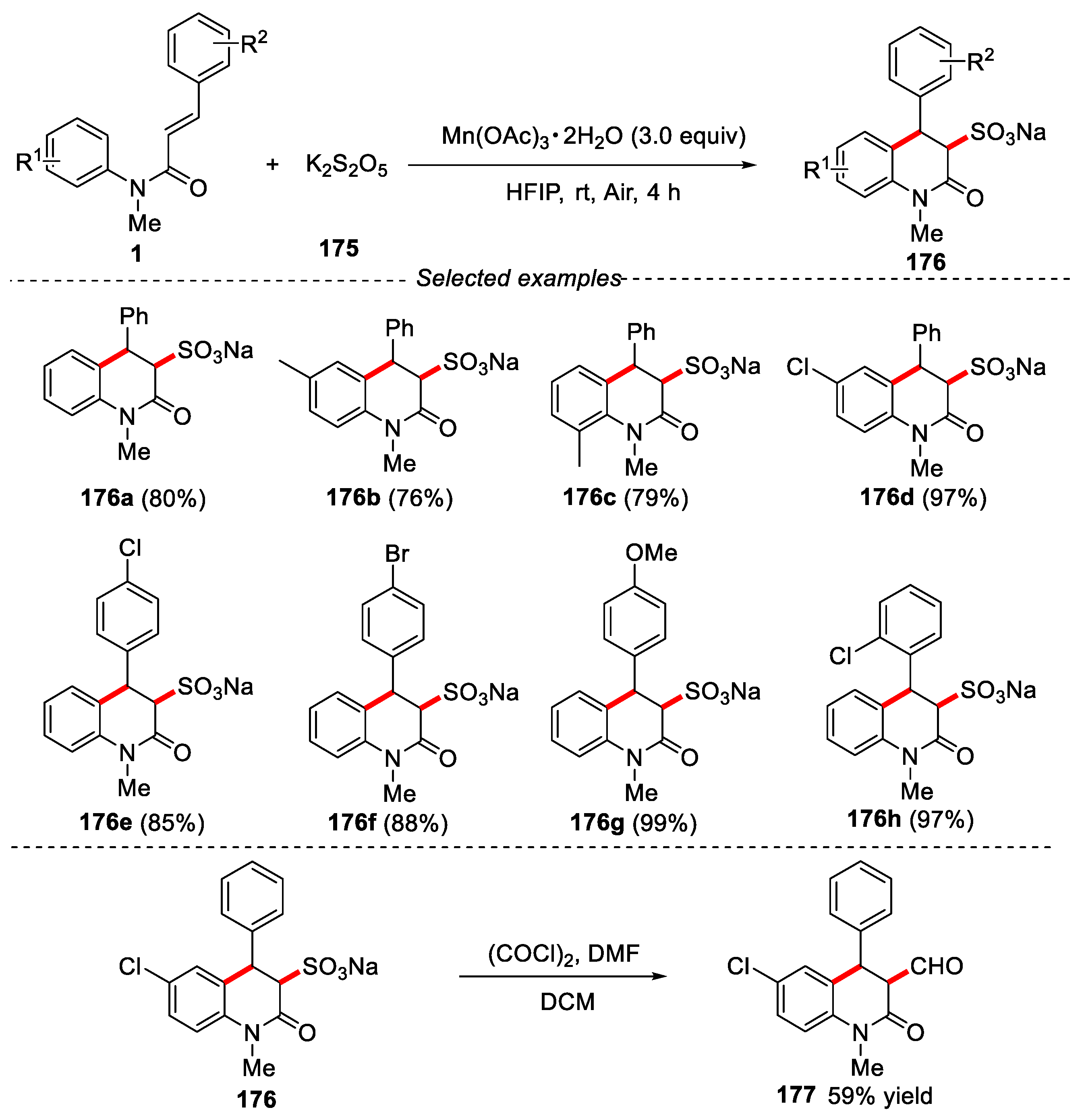

- Han, B.; Ding, X.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, X.; Qi, Y.; Liang, S. Mn (OAc)3-promoted sulfonation-cyclization cascade via the SO3– radical: the synthesis of heterocyclic sulfonates. Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 8255–8260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

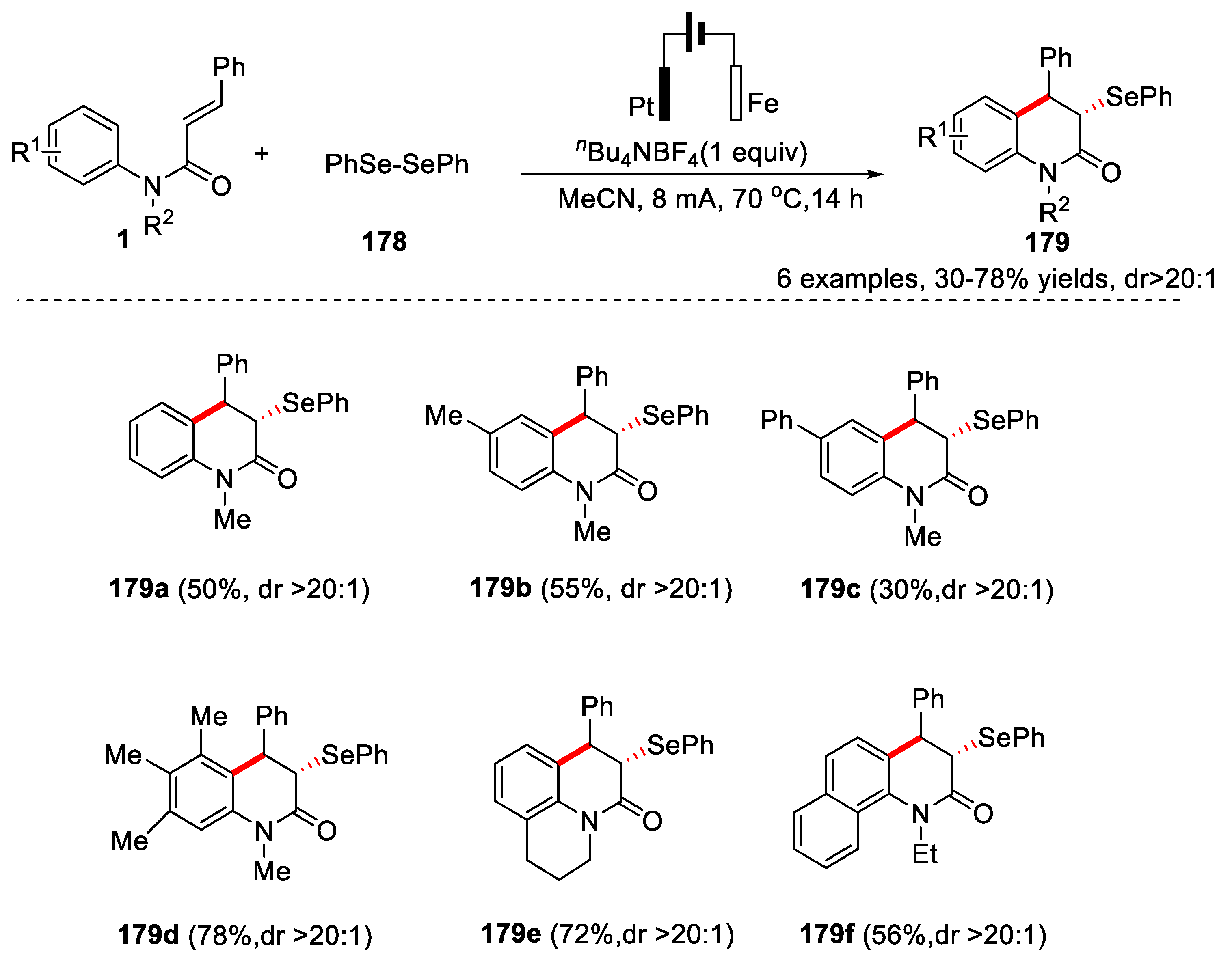

- Cheng, X.; Hasimujiang, B.; Xu, Z.; Cai, H.; Chen, G.; Mo, G.; Ruan, Z. Direct electrochemical selenylation/cyclization of alkenes: access to functionalized benzheterocycles. J. Org. Chem., 2021, 86, 16045−16058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.-Y.; Zhong, Y.-F.; Mo, Z.-Y.; Wu, S.-H.; Xu, Y.-L.; Tang, H.-T.; Pan, Y.-M. Synthesis of seleno oxindoles via electrochemical cyclization of N-arylacrylamides with diorganyl diselenides. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2021, 363, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, O. L.; Adams, W. R. Photochemical transformations. XXII. Photoisomerization of substituted acrylic acids and acrylamides to beta-lactones and beta-lactams. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1968, 90, 2333–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhong, S.; Ji, X.; Deng, G.-J.; Huang, H. Hydroarylation of activated alkenes enabled by proton-coupled electron transfer. ACS Catal., 2021, 11, 4422–4429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-L.; Yang, X.-L.; Shen, S.; Niu, X. Synthesis of 10-phenanthrenols via photosensitized triplet energy transfer, photoinduced electron transfer, and cobalt catalysis. J. Org. Chem., 2022, 87, 16458−16472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Lam, T.-L.; Liu, Y.; Tang, Z.; Che, C.-M. Photoinduced hydroarylation and cyclization of alkenes with luminescent platinum(II) complexes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 2021, 60, 1383−1389. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.-W.; Liu, Y.; Jin, X.-Q.; Sun, Y.-Y.; Gu, S.-L.; Fu, L.; Li, J.-Q. Development and kilogram-scale synthesis of a D2/5-HT2A receptor dual antagonist (±)-SIPI 6360. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2016, 20, 1662–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oddy, M. J.; Kusza, D. A.; Petersen, W. F. Visible-light mediated metal-free 6π-photocyclization of N-acrylamides: thioxanthone triplet energy transfer enables the synthesis of 3,4-dihydroquinolin-2-ones. Org. Lett., 2021, 23, 8963−8967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popescu, M. V.; Mekereeya, A.; Alegre-Requena, J. V.; Paton, R. S.; Smith, M. D. Visible-light-mediated heterocycle functionalization via geometrically interrupted [2 + 2] cycloaddition. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 23020–23024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Münster, N.; Parker, N. A.; van Dijk, L.; Paton, R. S.; Smith, M. D. Visible light photocatalysis of 6π heterocyclization. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 2017, 56, 9468−9472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Zhong, S.; Ji, X. , Deng, G.-J.; Huang, H. Photoredox cyclization of N-arylacrylamides for synthesis of dihydroquinolinones. Org. Lett., 2022, 24, 349−353. [Google Scholar]

- Raghunathan, R.; Jockusch, S.; Sibi, M. P.; Sivaguru, J. Evaluating thiourea/urea catalyst for enantioselective 6π-photocyclization of acrylanilides. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chem., 2016, 331, 84−88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumarasamy, E.; Ayitou, A. J. L.; Vallavoju, N.; Raghunathan, R.; Iyer, A.; Clay, A.; Kandappa, S. K.; Sivaguru, J. Tale of twisted molecules. Atropselective photoreactions: taming light induced asymmetric transformations through non-biaryl atropisomers. Acc. Chem. Res., 2016, 49, 2713−2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayitou, A. J. L.; Sivaguru, J. Light-induced transfer of molecular chirality in solution: enantiospecific photocyclization of molecularly chiral acrylanilides. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2009, 131, 5036–5037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, A.; Ugrinov, A.; Sivaguru, J. Understanding conformational preferences of atropisomeric hydrazides and its influence on excited state transformations in crystalline media. Molecules, 2019, 24, 3001−3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, B. A.; Solon, P.; Popescu, M.V.; Du, J.-Y.; Paton, R.; Smith, M. D. Catalytic enantioselective 6π photocyclization of Aacrylanilides. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2023, 145, 171−178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).