Submitted:

29 May 2023

Posted:

30 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Measures

2.1.1. Cognitive Functioning

2.1.2. Sensory Impairment

2.1.3. Social Isolation

2.1.4. Covariates

2.2. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

3.2. Direct Associations

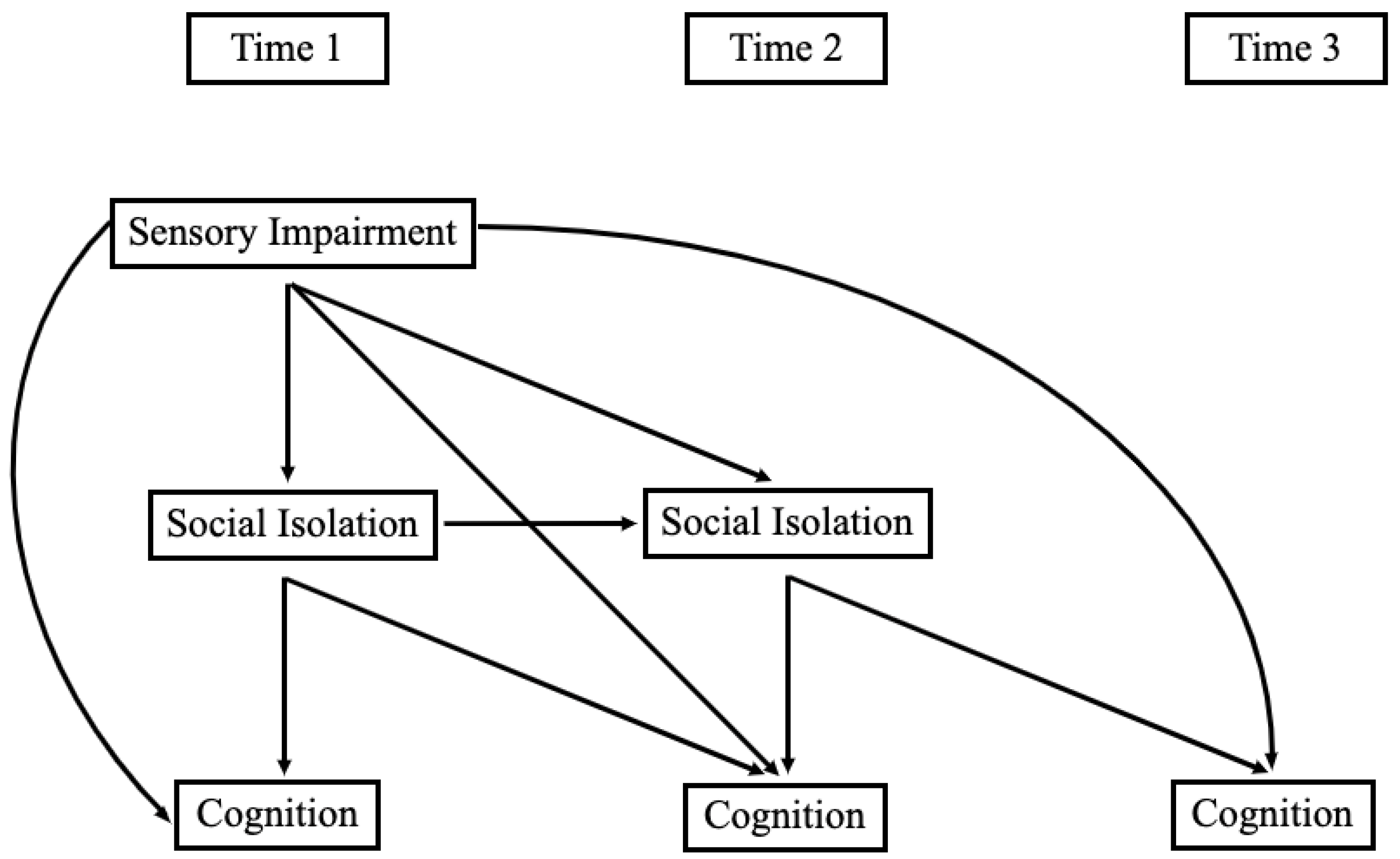

- How do sensory impairments relate to social isolation concurrently and across time? Contrary to our expectations, neither VI nor HI were significantly associated with social isolation concurrently or across time. Unlike VI and HI alone, DSI was associated with higher social isolation one year later in both Model 1 (β = .079, p < .05) and Model 2 (β = .086, p < .05).

- How do sensory impairments relate to cognitive functioning across time among Hispanic older adults? As seen in Model 1 of Table 3, VI was negatively associated with concurrent orientation (β = -.111, p < .01) and executive function scores (β = -.109, p < .05), as well as with learning/memory (β = -.124, p < .05) and executive function (β = -.103, p < .01) one year later. VI was also associated with lower executive function scores one year later when covariates were added in Model 2 (β = -.079, p < .05). HI was not associated with measures of cognitive functioning in this sample. As seen in Table 4, DSI was negatively associated with orientation scores concurrently in Model 1 (β = -.094, p < .05) and with learning/memory across one year in Model 1 (β = -.143, p < .01) and Model 2 (β = -.091, p < .05).

- What is the relationship between social isolation and cognitive functioning among Hispanic older adults? As displayed in Table 3, social isolation was negatively associated with concurrent orientation in Model 2 (β = -.091, p < .05) and executive function in Model 1 (β = -.099, p < .05) and Model 2 (β = -.113, p < .05). Social isolation was also related to lower learning/memory across one year in Model 1 (β = -.084, p < .05) and Model 2 (β = -.111, p < .01).

3.3. Indirect Associations

- 4.

- Are sensory impairments related indirectly to cognitive functioning through social isolation? There were no significant indirect associations between VI, HI, or DSI and cognitive functioning through social isolation.

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

References

- Arnold, M.L.; Hyer, K.; Small, B.J.; Chisolm, T.; Saunders, G.H.; McEvoy, C.L.; Lee, D.J.; Dhar, S.; Bainbridge, K.E. Hearing aid prevalence and factors related to use among older adults from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. JAMA Otolaryngol.—Head Neck Surg. 2019, 145, 501–508. [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.M. Prevalence of open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension in Latinos: The Los Angeles Latino eye study. Evid. -Based Eye Care 2005, 6, 14–15. [CrossRef]

- Campos, B.; Ullman, J.B.; Aguilera, A.; Dunkel Shetter, C. Familism and psychological health: The intervening role of closeness and social support. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2014, 20, 191–201. [CrossRef]

- Campos, C.L.; Rodriguez, C.J. High blood pressure in Hispanics in the United States. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2019, 34, 350–358. [CrossRef]

- Cao, G. -Y.; Chen, Z.-S.; Yao, S.-S.; Wang, K.; Huang, Z.-T.; Su, H.-X.; Luo, Y.; De Fries, C.M.; Hu, Y.-H.; Xu, B. The association between vision impairment and cognitive outcomes in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging & Mental Health 2023, 27, 350–356. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.J.; Kanaya, A.M.; Araneta, M.R.; Saydah, S.H.; Kahn, H.S.; Gregg, E.W.; Fujimoto, W.Y.; Imperatore, G. Prevalence of diabetes by race and ethnicity in the United States 2019, 2011-2016. JAMA, 322, 2389. [CrossRef]

- Chin, A.L.; Negash, S.; Hamilton, R. Diversity and disparity in dementia: the impact of ethnoracial differences in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2011, 25, 187–195. [CrossRef]

- Corona, K.; Campos, B.; Chen, C. Familism is associated with psychological wellbeing and physical health. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 2017, 39, 46–65. [CrossRef]

- Cohn, D.; Passel, J.S. (2018). A record 64 million Americans live in multigenerational households. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/04/05/a-record-64-million-americans-liveinmultigenerational- households/.

- Cruickshanks, K.J.; Dhar, S.; Dinces, E.; Fifer, R.C.; Gonzalez, F.; Heiss, G.; Hoffman, H.J.; Lee, D.J.; Newhoff, M.; Tocci, L.; Torre, P.; Tweed, T.S. Hearing impairment prevalence and associated risk factors in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. JAMA Otolaryngol. —Head Neck Surg. 2015, 141, 641–648. [CrossRef]

- Darin-Mattsson, A.; Fors, S.; Karcholt, I. Different indicators of socioeconomic status and their relative importance as determinants of health in older age. Int. J. Equity Health 2017, 16, 173. [CrossRef]

- Davidson, J.G. S.; Guthrie, D.M. Older adults with a combination of vision and hearing impairment experience higher rates of cognitive impairment, functional dependence, and worse outcomes across a set of quality indicators. J. Aging Health 2019, 31, 85–108. [CrossRef]

- Ehrlich, J.R.; Goldstein, J.; Swenor, B.K.; Whitson, H.; Langa, K.M.; Veliz, P. (2022) Addition of vision impairment to a life-course model of potentially modifiable dementia risk factors in the US. JAMA Neurology, 79 623-626. [CrossRef]

- Fuller-Iglesias, H.R.; Antonucci, T.C. Familism, social network characteristics, and well-being among older adults in Mexico. J. Cross-Cult. Gerontol. 2016, 31, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Gallegos, M.L.; Segrin, C. Family connections and the Latino health paradox: Exploring the mediating role of loneliness in the relationships between the Latina/o cultural value of familism and health. Health Commun. 2022, 37, 1204–1214. [CrossRef]

- Gallo, L.C.; Penedo, F.J.; Espinosa de los Monteros, K.; Arguelles, W. Resiliency in the face of disadvantage: Do Hispanic cultural characteristics protect health outcomes? J. Personal. 2009, 77, 1707–1746. [CrossRef]

- Goman, A.M.; Lin, F.R. Prevalence of hearing loss by severity in the United States. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, 1820–1822. [CrossRef]

- Hawton, A.; Green, C.; Dickens, A.P.; Richards, S.H.; Taylor, R.S.; Edwards, R.; Greaves, C.J.; Campbell, J.L. The impact of social isolation on the health status and health-related quality of life of older people. Qual. Life Res. 2011, 20, 57–67. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, M.M.; Bamaca-Colbert, M.Y. A behavioral process model of familism. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 2016, 8, 463–483. [CrossRef]

- Herren, D. J.; Kohanim, S. Disparities in vision loss due to cataracts in Hispanic women in the United States. Seminars in Ophthalmology 2016, 31, 353–357. [CrossRef]

- Heyl, V.; Wahl, H.-W. Experiencing age-related vision and hearing impairment: The psychosocial dimension. J. Clin. Outcomes Manag. 2014, 21, 323–335.

- Holt-Lunstad, J.; Smith, T.B.; Baker, M.; Harris, T.; Stephenson, D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 10, 227–237. [CrossRef]

- Kasper, J.D.; Freedman, V.A.; Spillman, B.C. (2013). Classification of persons by dementia status in the National Health and Aging Trends Study. Technical Paper #5.

- Kuo, P.-L.; Huang, A.R.; Ehrlich, J.R.; Kasper, J.; Lin, F.R.; McKee, M.M.; Reed, N.S.; Swenor, B.K.; Deal, J.A. Prevalence of concurrent functional vision and hearing impairment and association with dementia in community-dwelling medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e211558. [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.R.; Albert, M. Hearing loss and dementia–who is listening? Aging Ment. Health 2014, 18, 671–673. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, Q.; Abuduxukuer, K.; Hou, Y.; Wei, J.; Liu, H.; Luo, J.; Gao, G.; Zhou, Y. Is there a correlation between sensory impairments and social isolation in middle-aged and older Chinese population? Cross-sectional and longitudinal evidence from a nationally representative survey. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1098109. [CrossRef]

- Livingston, G.; Huntley, J.; Sommerlad, A.; Ames, D.; Ballard, C.; Banerjee, S.; Brayne, C.; Burns, A.; Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Cooper, C.; Costafreda, S.G.; Dias, A.; Fox, N.; Gitlin, L.N.; Howard, R.; Kales, H.C.; Kivimäki, M.; Larson, E.B.; Ogunniyi, A.;... Mukadam, N. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet 2020, 396, 413–446. [CrossRef]

- Locher, J.L.; Ritchie, C.S.; Roth, D.L.; Baker, P.S.; Bodner, E.V.; Allman, R.M. Social isolation, support, and capital and nutritional risk in an older sample: Ethnic and gender differences. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 60, 747–761. [CrossRef]

- Markides, K.S.; Eschbach, K. Aging, migration, and mortality: Current status of research on the Hispanic Paradox. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B 2005, 60, S68– S75. [CrossRef]

- Min, J.W.; Barrio, C. Cultural values and caregiver preference for Mexican-American and non-Latino White elders. J. Cross-Cult. Gerontol. 2009, 24, 225–239. [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan, N.; Assi, L.; Varadaraj, V.; Motaghi, M.; Sun, Y.; Couser, E.; Ehrlich, J.R.; Whitson, H.; Swenor, B.K. Vision Impairment and cognitive decline among older adults: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Nathan, N.; Joos, K.M. Glaucoma disparities in the Hispanic population. Semin. Ophthalmol. 2016, 31, 394–399. [CrossRef]

- Noe-Bustamante, L.; Lopez, M.H.; Krogstad, J.M. (2020, July 7). U.S. Hispanic population surpassed 60 million in 2019, but growth has slowed. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/07/07/u-shispanic- population-surpassed-60-million-in-2019-but-growth-has-slowed/.

- Patel, N.; Stagg, B.C.; Swenor, B.K.; Zhou, Y.; Talwar, N.; Ehrlich, J.R.; (2020). Association of co-occurring dementia and selfreported visual impairment with activity limitations in older adults. JAMA Ophthalmology, 138, 756-763. [CrossRef]

- Rajan, K.B.; Weuve, J.; Barnes, L.L.; McAninch, E.A.; Wilson, R.S.; Evans, D.A. Population estimate of people with clinical Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment in the United States (2020-2060). Alzheimer’s and Dementia. 17 2021, 1873-2056. [CrossRef]

- Read, S. ; Comas-Herrera, A.; Grundy, E. Social isolation and memory decline in later life. The J. Gerontol. : Ser. B 2020, 75, 367–376. [CrossRef]

- Samper-Ternent, R.; Kuo, Y.F.; Ray, L.A.; Ottenbacher, K.J.; Markides, K.S.; Al Snih, S. (2012) Prevalence of health conditions and predictors of mortality in oldest old Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic whites. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 13 254-9. [CrossRef]

- Santini, Z.I.; Jose, P.E.; Cornwell, E.Y.; Koyanagi, A.; Nielsen, L.; Hinrichsen, C.; Meilstrup, C.; Madsen, K.R.; Koushede, V. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and symptoms of depression and anxiety among older Americans (NSHAP): A longitudinal mediation analysis. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e62–e70. [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.; Frank C. R.; Ehrlich, J.R. The association between vision impairment and social participation in community-dwelling adults: A systematic review. Eye 2020, 34, 290– 298. [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A.; Harper, M.; Pedersen, E.; Goman, A.; Suen, J.J.; Price, C.; Applebaum, J.; Hoyer, M.; Lin, F.R.; Reed, N.S. Hearing loss, loneliness, and social isolation: A systematic review. Otolaryngol. —Head Neck Surg. 2020, 162, 622–633. [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.J.; Weisskirch, R.S.; Hurley, E.A.; Zamboanga, B.L.; Park, I.J. K.; Kim, S.Y.; Umaña-Taylor, A.; Castillo, L.G.; Brown, E.; Greene, A.D. Communalism, familism, and filial piety: Are they birds of a collectivist feather? Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2010, 16, 548–560. [CrossRef]

- Swenor, B.K.; Ramulu, P.Y.; Willis, J.R.; Friedman, D.; Lin, F.R. Research letters: The prevalence of concurrent hearing and vision impairment in the United States. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013, 173, 312–313. [CrossRef]

- Trujillo Tanner, C.; Yorgason, J; Richardson, S.; White, A.; Redelfs, A.; Stagg, B.; Erlich, J; Markides, K (2022). Social isolation among Hispanic older adults with sensory impairments: Toward culturally sensitive measurement. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 77, 2091-2100. [CrossRef]

- US Census, B. (2021). Hispanic population to reach 111 million by 2060. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/2018/comm/hispanic-projectedpop. html#:~:text=Hispanic%20Population%20to%20Reach%20111%20Million%20by%202060.

- Uribe, J.A.; Swenor, B.K.; Muñoz, B.E.; West, S.K. Uncorrected refractive error in a Latino population: Proyecto VER. Ophthalmology 2011, 118, 805–811. [CrossRef]

- Vargas Bustamante, A.; Fang, H.; Rizzo, J.A.; Ortega, A.N. (2009). Understanding observed and unobserved health care access and utilization disparities among US Latino adults. Medical Care Research and Review. 66 561–577. [CrossRef]

- Varma, R.; Paz, S.H.; Azen, S.P.; Klein, R.; Globe, D.; Torres, M.; Shufelt, C.; Preston-Martin, S.; Los Angeles Latino Eye Study Group. The Los Angeles Latino Eye Study: Design, methods, and baseline data. Ophthalmology 2004, 111, 1121–1131. [CrossRef]

- Vega, W.A.; Rodriguez, M.A.; Gruskin, E. (2009). Health disparities in the Latino Population. Epidemiologic Reviews. 31 99-112. [CrossRef]

- Vincent, G.K.; Velkoff, V.A. (2010). The next four decades: The older population in the United States: 2010 to 2050. U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2010/demo/p25-1138.pdf.

- Wang, Q. ; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, D.; Zhou, C. Dual sensory impairment as a predictor of loneliness and isolation in older adults: National Cohort Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2022, 8, e39314. [CrossRef]

- Whitson, H.E.; Cronin-Golomb, A.; Cruickshanks, K.J.; Gilmore, G.C.; Owsley, C.; Peelle, J.E.; Recanzone, G.; Sharma, A.; Swenor, B.; Yaffe, K.; Lin, F.R. American Geriatrics Society and National Institute on Aging bench-to-bedside conference: Sensory impairment and cognitive decline in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2018, 66, 2052–2058. [CrossRef]

- West, J.S.; Lynch, S.M. Demographic and socioeconomic disparities in life expectancy with hearing impairment in the United States. J. Gerontol. : Ser. B 2021, 76, 944–955. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X.; Freedman, V.A.; Shah, K.; Hu, R.X.; Stagg, B.C.; Ehrlich, J.R. Selfreported vision impairment and subjective well-being in older adults: A longitudinal mediation analysis. J. Gerontol. : Ser. A 2020, 75, 589–595. [CrossRef]

- Yorgason, J.; Trujillo Tanner, C.; Richardson, S.; Burch, A.; Stagg, A.; Wettstein, M.; Hill, M. The longitudinal association of late-life visual and hearing difficulty and cognitive function: The role of social isolation. J. Aging Health Sage Publ. 2022, 34, 765–774. [CrossRef]

| Variable | N (%) or Mean (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Age Groups 65–69 70–74 75–79 80–84 85–89 ≥ 90 |

151 (27.11%) 141 (25.31%) 106 (19.03%) 88 (15.80%) 46 (8.26%) 25 (4.49%) |

|

| Sex Male (coded as 1) Female (coded as 0) |

246 (44.17%) 311 (55.83%) |

|

| Education Level Less than High School High School Trade/Some college College degree |

318 (57.09%) 87 (15.62%) 83 (14.90%) 69 (12.39%) |

|

| Marital Status | ||

| Married | 276 (49.64%) | |

| Not Married | 280 (50.36%) | |

| Smoking Status | ||

| Smoker | 19 (5.57%) | |

| Non-Smoker | 322 (94.43) | |

| Hearing Disability | ||

| Hearing Loss | 117 (21.47%) | |

| No Hearing Loss | 417 (78.53%) | |

| Vision Disability | ||

| Vision Loss | 85 (15.29%) | |

| No Vision Loss | 471 (84.71%) | |

| Dual Sensory Disability | ||

| Hearing/Vision Loss | 37 (6.98%) | |

| No Hearing/Vision Loss | 493 (93.02%) | |

| Social Isolation | 0-4 | |

| Time 1 | 1.88 (.98) | |

| Time 2 | 1.81 (.98) | |

| Executive Function | 0-5 | |

| Time 1 | 3.19 (1.17) | |

| Time 2 | 3.22 (1.32) | |

| Time 3 | 3.10 (1.37) | |

| Learning/Memory | 0-9 | |

| Time 1 | 3.01 (1.76) | |

| Time 2 | 2.95 (1.87) | |

| Time 3 | 2.83 (1.89) | |

| Orientation | 0-8 | |

| Time 1 | 5.50 (1.42) | |

| Time 2 | 5.63 (1.58) | |

| Time 3 | 5.42 (1.62) | |

| Health | 1.20 (.89) | 0-4 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. T1 HL | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 2. T1 VL | .25*** | 1 | |||||||||||

| 3. T1 DI | .52** | .65** | 1 | ||||||||||

| 4. T1 Social Iso | .04 | -.05 | -.05 | 1 | |||||||||

| 5. T2 Social Iso | .06 | .00 | .06 | .56*** | 1 | ||||||||

| 6. T1 Exec Fun | -.00 | -.08* | -.05 | -.08* | -.10* | 1 | |||||||

| 7. T2 Exec Fun | -.02 | -.15** | -.10* | -.13** | -.06 | .56*** | 1 | ||||||

| 8. T3 Exec Fun | -.04 | -.12* | -.06 | -.04 | .01 | .50*** | .56*** | 1 | |||||

| 9. T1 Learning | -.07 | -.05 | -.04 | .01 | .04 | .14** | .16*** | .15** | 1 | ||||

| 10. T2 Learning | -.11* | -.15** | -.17*** | -.05 | -.07 | .16*** | .29*** | .32*** | .44*** | 1 | |||

| 11. T3 Learning | -.12* | -.01 | -.08 | -.05 | -.06 | .18*** | .24*** | .35*** | .37*** | .57*** | 1 | ||

| 12. T1 Orient | -.09* | -.11* | -.07 | -.04 | -.01 | .20*** | .25*** | .23*** | .20*** | .25*** | .20*** | 1 | |

| 13. T2 Orient | -.06 | -.12** | -.11* | -.01 | -.06 | .22*** | .29*** | .34*** | .21*** | .36*** | .32*** | .60*** | 1 |

| 14. T3 Orient | -.10 | -.10 | -.11* | .04 | .01 | .28*** | .41*** | .39*** | .17** | .31*** | .36*** | .41*** | .49*** |

| Learning/Memory B (SE) |

Orientation B (SE) |

Executive Function B (SE) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 |

| VI -> T1 CF | -.035 (.04) | .009 (.04) | -.111** (.04) | -.045 (.04) | -.109* (.05) | -.056 (.04) |

| VI -> T2 CF | -.124* (.05) | -.077 (.05) | -.045 (.04) | -.020 (.04) | -.103** (.04) | -.079* (.04) |

| VI -> T3 CF | .073 (.05) | .093† (.05) | -.046 (.04) | -.029 (.04) | -.057 (.05) | -.046 (.05) |

| HI -> T1 CF | -.070 (.05) | -.022 (.05) | -.076† (.05) | -.030 (.04) | .022 (.05) | .065 (.04) |

| HI -> T2 CF | -.037 (.05) | -.001 (.05) | -.003 (.04) | .020 (.04) | .004 (.04) | .035 (.04) |

| HI -> T3 CF | -.080† (.04) | -.056 (.04) | -.035 (.05) | -.017 (.04) | -.031 (.05) | -.012 (.05) |

| T1 Social Isolation -> T1 CF | .009 (.04) | .008 (.04) | -.045 (.04) | -.091* (.04) | -.099* (.04) | -.113* (.05) |

| T2 Social Isolation -> T2 CF | -.084* (.04) | -.111** (.04) | -.047 (.04) | -.037 (.04) | .002 (.04) | -.042 (.04) |

| T2 Social Isolation -> T3 CF | -.010 (.04) | -.037 (.04) | .047 (.05) | -.017 (.05) | .078† (.04) | .084† (.05) |

| VI -> T1 Social Isolation | -.066 (.05) | -.058 (.05) | -.066 (.05) | -.056 (.05) | -.064 (.05) | -.055 (.05) |

| VI -> T2 Social Isolation | .009 (.04) | .022 (.04) | .009 (.04) | .022 (.04) | .009 (.04) | .022 (.04) |

| HI -> T1 Social Isolation | .056 (.05) | .049 (.05) | .057 (.05) | .051 (.05) | .055 (.05) | .048 (.05) |

| HI -> T2 Social Isolation | .044 (.04) | .051 (.04) | .043 (.04) | .050 (.04) | .043 (.04) | .050 (.04) |

| VI -> T1 Social Isolation -> T1 CF | -.001 (.00) | .000 (.00) | .003 (.00) | .005 (.01) | .006 (.01) | .006 (.01) |

| VI -> T2 Social Isolation -> T2 CF | -.001 (.00) | -.002 (.01) | .000 (.00) | -.001 (.00) | .000 (.00) | -.001 (.00) |

| VI -> T2 Social Isolation -> T3 CF | .000 (.00) | -.001 (.00) | .000 (.00) | .000 (.00) | .001 (.00) | .002 (.00) |

| HI -> T1 Social Isolation -> T1 CF | .001 (.00) | .000 (.00) | -.003 (.00) | -.005 (.01) | -.005 (.01) | -.005 (.01) |

| HI -> T2 Social Isolation -> T2 CF | -.004 (.01) | -.006 (.01) | -.002 (.00) | -.002 (.00) | .000 (.00) | -.002 (.00) |

| HI -> T2 Social Isolation -> T3 CF | .000 (.00) | -.002 (.00) | .002 (.00) | -.001 (.00) | .003 (.00) | .004 (.01) |

| Sample Size (N) | 557 | 557 | 557 | 557 | 557 | 557 |

| Chi-Square Model Fit | .70 | .27 | 1.19 | 1.81 | 7.90* | 10.19* |

| RMSEA | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .05 | .07 |

| CFI | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | .99 | .99 |

| R2 of T3 CF | .35*** | .43*** | .30*** | .38*** | .37*** | .40*** |

| Learning/Memory B (SE) |

Orientation B (SE) |

Executive Function B (SE) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 |

| DSI -> T1 CF | -.041 (.04) | .013 (.04) | -.094* (.04) | -.031 (.04) | -.064 (.05) | -.015 (.05) |

| DSI -> T2 CF | -.143** (.04) | -.091* (.04) | -.060 (.05) | -.026 (.05) | -.081† (.04) | -.042 (.04) |

| DSI -> T3 CF | -.001 (.04) | .013 (.04) | -.050 (.05) | -.031 (.05) | -.017 (.05) | .000 (.05) |

| T1 Social Isolation -> T1 CF | .006 (.04) | .008 (.04) | -.047 (.04) | -.091* (.04) | -.097* (.04) | -.110* (.05) |

| T2 Social Isolation -> T2 CF | -.077* (.04) | -.106* (.04) | -.044 (.04) | -.034 (.04) | .008 (.04) | -.038 (.04) |

| T2 Social Isolation -> T3 CF | -.012 (.04) | -.039 (.04) | .048 (.05) | -.017 (.05) | .077† (.04) | .083† (.05) |

| DSI -> T1 Social Isolation | -.05 (.05) | -.056 (.05) | -.052 (.05) | -.055 (.05) | -.051 (.05) | -.056 (.05) |

| DSI -> T2 Social Isolation | .079* (.04) | .086* (.04) | .079* (.04) | .086* (.04) | .079* (.04) | .086* (.04) |

| DSI -> T1 Social Isolation -> T1 CF | .000 (.00) | .000 (.00) | .002 (.00) | .005 (.01) | .005 (.01) | .006 (.01) |

| DSI -> T2 Social Isolation -> T2 CF | -.006 (.01) | -.009 (.01) | -.003 (.00) | -.003 (.00) | .001 (.00) | -.003 (.00) |

| DSI -> T2 Social Isolation -> T3 CF | -.001 (.00) | -.003 (.00) | .004 (.00) | -.001 (.01) | .006 (.00) | .007 (.01) |

| Sample Size (N) | 557 | 557 | 557 | 557 | 557 | 557 |

| Chi-Square | .90 | .27 | 1.05 | 1.80 | 7.94* | 10.14* |

| RMSEA | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .05 | .07 |

| CFI | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | .99 | .99 |

| R2 of T3 CF | .34*** | .42*** | .30*** | .38*** | .36*** | .40*** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).