Submitted:

06 February 2025

Posted:

07 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Socioeconomic Factors and Cognition

1.2. The Mediating Role of Social Participation and Social Support

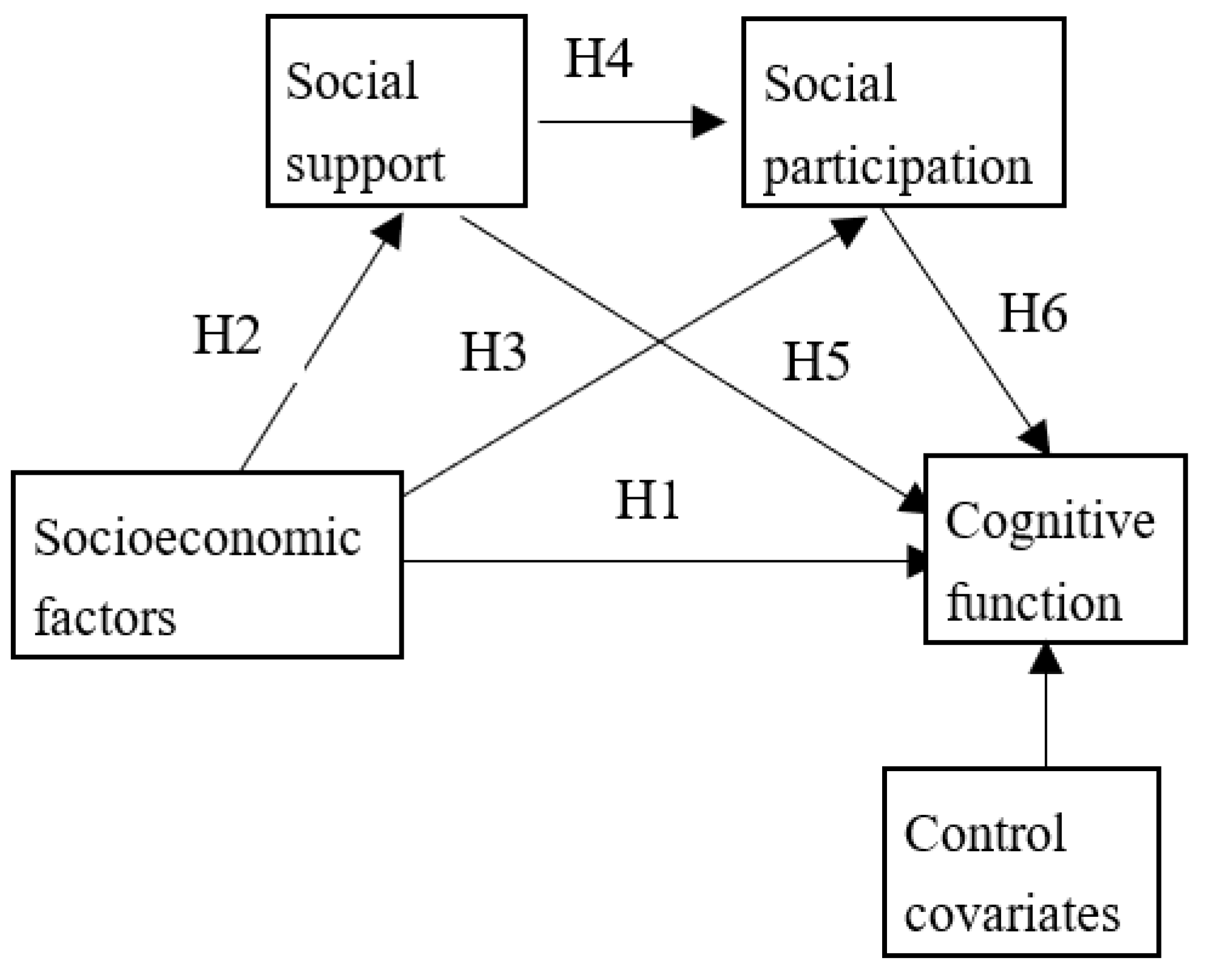

1.3. The Conceptual Model of Present Study

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Cognitive Function

2.2.2. Socioeconomic Factors

2.2.3. Social participation and social support

2.2.4. Covariates

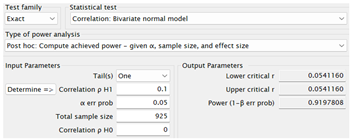

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Analysis for Common Method Bias

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis for the Study Variables

3.3. Mediation Effect Analysis

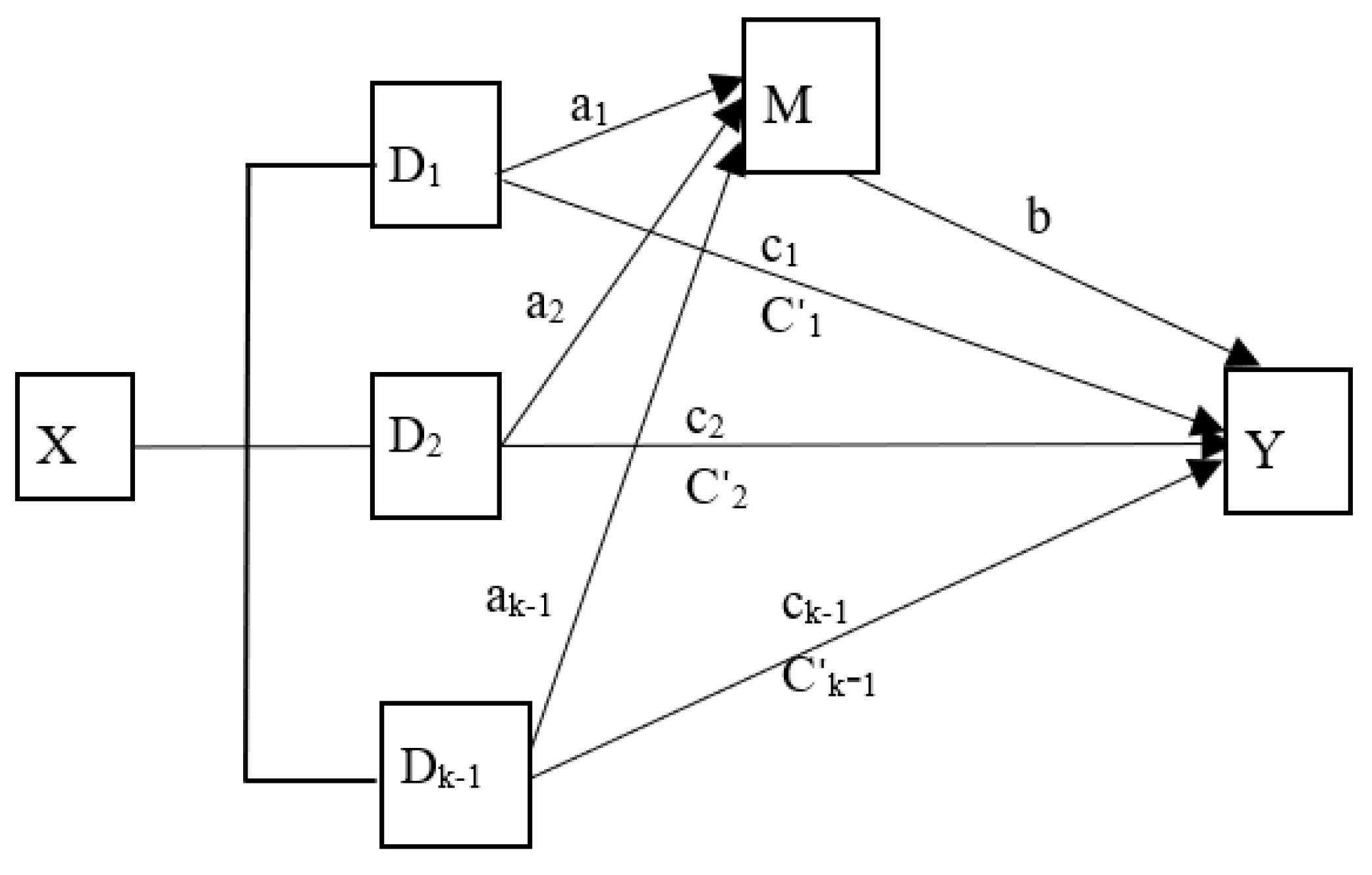

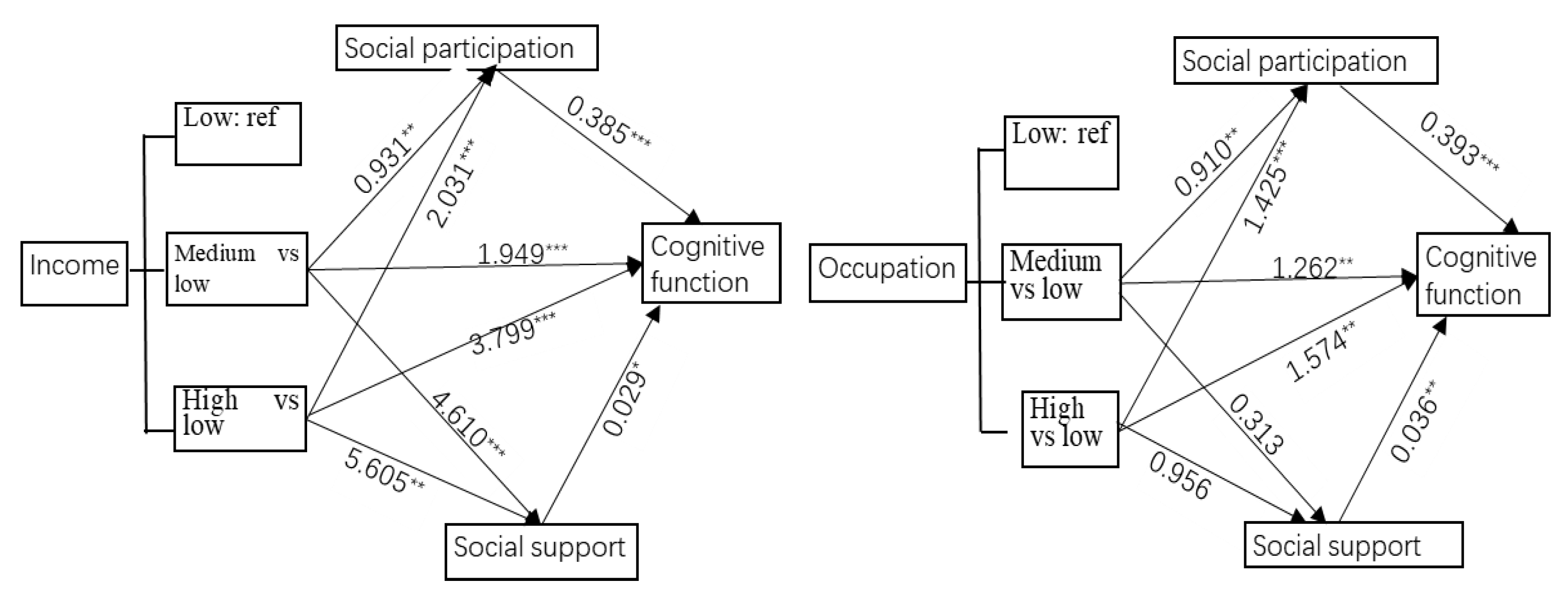

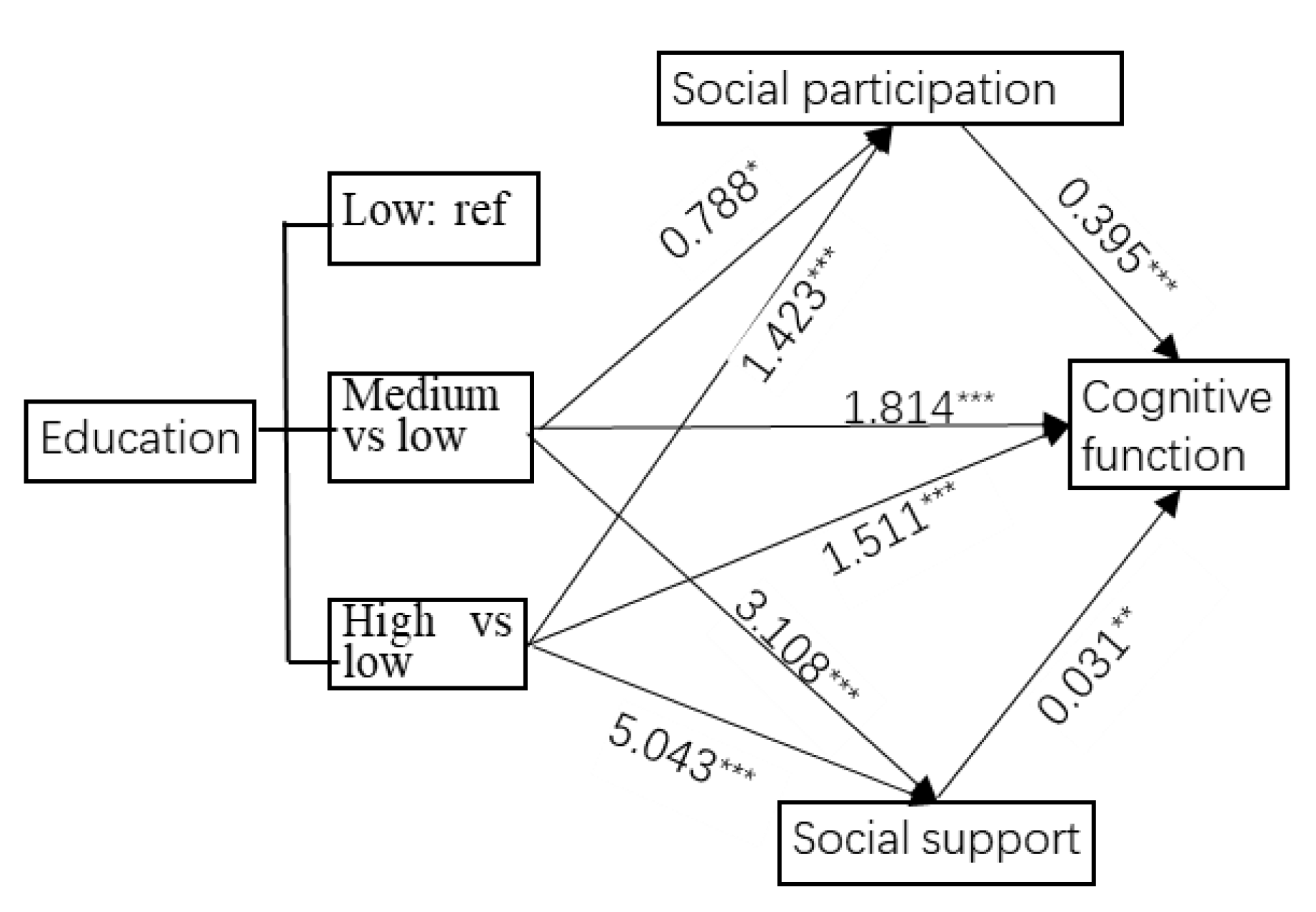

3.3.1. Omnibus Mediation Effect Analysis

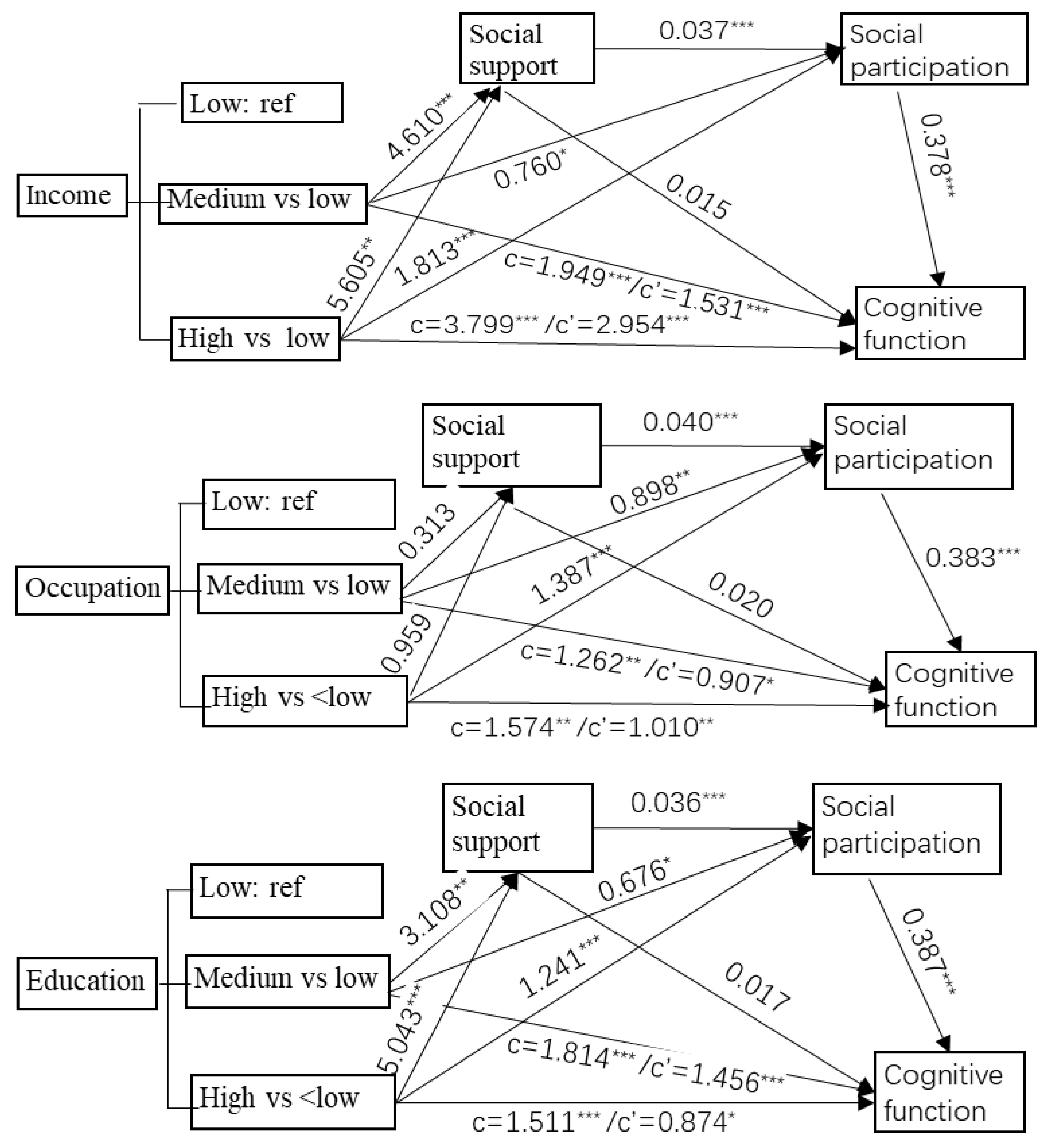

3.3.2. Relative Mediation Effect of Social Participation or Social Support

3.3.3. Relative Seral Mediating Effect of Social Support And Social Participation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Availability of data and materials

Acknowledgments

Competing interests

References

- Mobaderi T, Kazemnejad A, Salehi M. Exploring the impacts of risk factors on mortality patterns of global Alzheimer's disease and related dementias from 1990 to 2021. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):15583. [CrossRef]

- Tu WJ, Zeng X, Liu Q. Aging tsunami coming: the main finding from China's seventh national population census. Aging clinical and experimental research. 2022;34(5):1159-63. [CrossRef]

- Yuan L, Zhang X, Guo N, Li Z, Lv D, Wang H, et al. Prevalence of cognitive impairment in Chinese older inpatients and its relationship with 1-year adverse health outcomes: a multi-center cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21(1):595. [CrossRef]

- Cigolle CT, Langa KM, Kabeto MU, Tian Z, Blaum CS. Geriatric conditions and disability: the Health and Retirement Study. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(3):156-64. [CrossRef]

- Rivas-Sucari HC, Rodríguez-Eguizabal JL. Cognitive health in older adults, a public health challenge. Gaceta medica de Mexico. 2024;160(2):223-4. [CrossRef]

- Cox SR, Deary IJ. Brain and cognitive ageing: The present, and some predictions (…about the future). Aging brain. 2022;2:100032. [CrossRef]

- Oosterhuis EJ, Slade K, May PJC, Nuttall HE. Toward an Understanding of Healthy Cognitive Aging: The Importance of Lifestyle in Cognitive Reserve and the Scaffolding Theory of Aging and Cognition. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2023;78(5):777-88. [CrossRef]

- Reuter-Lorenz PA, Park DC. Cognitive aging and the life course: A new look at the Scaffolding theory. Current opinion in psychology. 2024;56:101781. [CrossRef]

- Joshi P, Hendrie K, Jester DJ, Dasarathy D, Lavretsky H, Ku BS, et al. Social connections as determinants of cognitive health and as targets for social interventions in persons with or at risk of Alzheimer's disease and related disorders: a scoping review. International psychogeriatrics. 2024;36(2):92-118. [CrossRef]

- Honeycutt AA, Khavjou OA, Tayebali Z, Dempsey M, Glasgow L, Hacker K. Cost-Effectiveness of Social Determinants of Health Interventions: Evaluating Multisector Community Partnerships' Efforts. Am J Prev Med. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Chen E, Miller GE. Socioeconomic status and health: mediating and moderating factors. Annual review of clinical psychology. 2013;9:723-49. [CrossRef]

- Braveman P, Gottlieb L. The social determinants of health: it's time to consider the causes of the causes. Public health reports (Washington, DC : 1974). 2014;129 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):19-31. [CrossRef]

- Jester DJ, Kohn JN, Tibiriçá L, Thomas ML, Brown LL, Murphy JD, et al. Differences in Social Determinants of Health Underlie Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Psychological Health and Well-Being: Study of 11,143 Older Adults. The American journal of psychiatry. 2023;180(7):483-94. [CrossRef]

- Crear-Perry J, Correa-de-Araujo R, Lewis Johnson T, McLemore MR, Neilson E, Wallace M. Social and Structural Determinants of Health Inequities in Maternal Health. Journal of women's health (2002). 2021;30(2):230-5. [CrossRef]

- Rusmaully J, Dugravot A, Moatti JP, Marmot MG, Elbaz A, Kivimaki M, et al. Contribution of cognitive performance and cognitive decline to associations between socioeconomic factors and dementia: A cohort study. PLoS medicine. 2017;14(6):e1002334. [CrossRef]

- Lawson KM, Sutin AR, Atherton OE, Robins RW. Are trajectories of personality and socioeconomic factors prospectively associated with midlife cognitive function? Findings from a 12-year longitudinal study of Mexican-origin adults. Psychology and aging. 2023;38(8):749-62. [CrossRef]

- Clarke AJ, Brodtmann A, Irish M, Mowszowski L, Radford K, Naismith SL, et al. Risk factors for the neurodegenerative dementias in the Western Pacific region. The Lancet regional health Western Pacific. 2024;50:101051. [CrossRef]

- Chapko D, McCormack R, Black C, Staff R, Murray A. Life-course determinants of cognitive reserve (CR) in cognitive aging and dementia - a systematic literature review. Aging Ment Health. 2018;22(8):915-26. [CrossRef]

- Levasseur M, Lussier-Therrien M, Biron ML, Raymond É, Castonguay J, Naud D, et al. Scoping study of definitions of social participation: update and co-construction of an interdisciplinary consensual definition. Age Ageing. 2022;51(2). [CrossRef]

- Zhang H, Hao X, Qin Y, Yang Y, Zhao X, Wu S, et al. Social participation classification and activities in association with health outcomes among older adults: Results from a scoping review. J Adv Nurs. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Tomioka K, Kurumatani N, Hosoi H. Social Participation and Cognitive Decline Among Community-dwelling Older Adults: A Community-based Longitudinal Study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2018;73(5):799-806. [CrossRef]

- Cunha C, Rodrigues P, Voss G, Martinez-Pecino R, Delerue-Matos A. Association between formal social participation and cognitive function in middle-aged and older adults: a longitudinal study using SHARE data. Neuropsychology, development, and cognition Section B, Aging, neuropsychology and cognition. 2024;31(5):932-55. [CrossRef]

- Hou J, Chen T, Yu NX. The Longitudinal Dyadic Associations Between Social Participation and Cognitive Function in Older Chinese Couples. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2024;79(6). [CrossRef]

- Li H, Li C, Wang A, Qi Y, Feng W, Hou C, et al. Associations between social and intellectual activities with cognitive trajectories in Chinese middle-aged and older adults: a nationally representative cohort study. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2020;12(1):115. [CrossRef]

- Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological bulletin. 1985;98(2):310-57.

- Lu S, Wu Y, Mao Z, Liang X. Association of Formal and Informal Social Support With Health-Related Quality of Life Among Chinese Rural Elders. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(4). [CrossRef]

- Gellert P, Häusler A, Suhr R, Gholami M, Rapp M, Kuhlmey A, et al. Testing the stress-buffering hypothesis of social support in couples coping with early-stage dementia. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0189849. [CrossRef]

- McHugh Power J, Carney S, Hannigan C, Brennan S, Wolfe H, Lynch M, et al. Systemic inflammatory markers and sources of social support among older adults in the Memory Research Unit cohort. Journal of health psychology. 2019;24(3):397-406. [CrossRef]

- Gui S, Wang J, Li Q, Chen H, Jiang Z, Hu J, et al. Sources of perceived social support and cognitive function among older adults: a longitudinal study in rural China. Frontiers in aging neuroscience. 2024;16:1443689. [CrossRef]

- Du C, Dong X, Katz B, Li M. Source of perceived social support and cognitive change: an 8-year prospective cohort study. Aging Ment Health. 2023;27(8):1496-505. [CrossRef]

- Smith L, Shin JI, López Sánchez GF, Oh H, Kostev K, Jacob L, et al. Social participation and mild cognitive impairment in low- and middle-income countries. Preventive medicine. 2022;164:107230. [CrossRef]

- Chanda S, Mishra R. Impact of transition in work status and social participation on cognitive performance among elderly in India. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):251. [CrossRef]

- Chiao, C. Beyond health care: Volunteer work, social participation, and late-life general cognitive status in Taiwan. Social science & medicine (1982). 2019;229:154-60. [CrossRef]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior research methods. 2009;41(4):1149-60. [CrossRef]

- Hong Y, Zeng X, Zhu CW, Neugroschl J, Aloysi A, Sano M, et al. Evaluating the Beijing Version of Montreal Cognitive Assessment for Identification of Cognitive Impairment in Monolingual Chinese American Older Adults. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2022;35(4):586-93. [CrossRef]

- Cao T, Zhang S, Yu M, Zhao X, Wan Q. The Chinese Translation Study of the Cognitive Reserve Index Questionnaire. Front Psychol. 2022;13:948740. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Chen Z, Zhou C. Social engagement and physical frailty in later life: does marital status matter? BMC Geriatr. 2021;21(1):248. [CrossRef]

- Zhou K, Li H, Wei X, Yin J, Liang P, Zhang H, et al. Reliability and validity of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support in Chinese mainland patients with methadone maintenance treatment. Comprehensive psychiatry. 2015;60:182-8. [CrossRef]

- Zhang C, Zhang H, Zhao M, Li Z, Cook CE, Buysse DJ, et al. Reliability, Validity, and Factor Structure of Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in Community-Based Centenarians. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:573530. [CrossRef]

- Kaiser MJ, Bauer JM, Ramsch C, Uter W, Guigoz Y, Cederholm T, et al. Validation of the Mini Nutritional Assessment short-form (MNA-SF): a practical tool for identification of nutritional status. The journal of nutrition, health & aging. 2009;13(9):782-8. [CrossRef]

- The PROCESS macro for SPSS, SAS, and R. PROCESS macro for SPSS and SAS.

- Hayes AF, Preacher KJ. Statistical mediation analysis with a multicategorical independent variable. The British journal of mathematical and statistical psychology. 2014;67(3):451-70. [CrossRef]

- Duncan GJ, Magnuson K. Socioeconomic status and cognitive functioning: moving from correlation to causation. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews Cognitive science. 2012;3(3):377-86. [CrossRef]

- Marengoni A, Fratiglioni L, Bandinelli S, Ferrucci L. Socioeconomic status during lifetime and cognitive impairment no-dementia in late life: the population-based aging in the Chianti Area (InCHIANTI) Study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;24(3):559-68. [CrossRef]

- Rakesh D, Whittle S. Socioeconomic status and the developing brain - A systematic review of neuroimaging findings in youth. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021;130:379-407. [CrossRef]

- Isbell E, Rodas De León NE, Richardson DM. Childhood family socioeconomic status is linked to adult brain electrophysiology. PLoS One. 2024;19(8):e0307406. [CrossRef]

- Thanaraju A, Marzuki AA, Chan JK, Wong KY, Phon-Amnuaisuk P, Vafa S, et al. Structural and functional brain correlates of socioeconomic status across the life span: A systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2024;162:105716. [CrossRef]

- Thomas MSC, Coecke S. Associations between Socioeconomic Status, Cognition, and Brain Structure: Evaluating Potential Causal Pathways Through Mechanistic Models of Development. Cognitive science. 2023;47(1):e13217. [CrossRef]

- Osler M, Avlund K, Mortensen EL. Socio-economic position early in life, cognitive development and cognitive change from young adulthood to middle age. European journal of public health. 2013;23(6):974-80. [CrossRef]

- Lövdén M, Fratiglioni L, Glymour MM, Lindenberger U, Tucker-Drob EM. Education and Cognitive Functioning Across the Life Span. Psychological science in the public interest : a journal of the American Psychological Society. 2020;21(1):6-41. [CrossRef]

- Fujishiro K, MacDonald LA, Crowe M, McClure LA, Howard VJ, Wadley VG. The Role of Occupation in Explaining Cognitive Functioning in Later Life: Education and Occupational Complexity in a U.S. National Sample of Black and White Men and Women. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2019;74(7):1189-99. [CrossRef]

- Kivimäki M, Walker KA, Pentti J, Nyberg ST, Mars N, Vahtera J, et al. Cognitive stimulation in the workplace, plasma proteins, and risk of dementia: three analyses of population cohort studies. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2021;374:n1804. [CrossRef]

- Boots EA, Schultz SA, Almeida RP, Oh JM, Koscik RL, Dowling MN, et al. Occupational Complexity and Cognitive Reserve in a Middle-Aged Cohort at Risk for Alzheimer's Disease. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2015;30(7):634-42. [CrossRef]

- Rydström A, Darin-Mattsson A, Kåreholt I, Ngandu T, Lehtisalo J, Solomon A, et al. Occupational complexity and cognition in the FINGER multidomain intervention trial. Alzheimers Dement. 2022;18(12):2438-47. [CrossRef]

- Azizi M, Mohamadian F, Ghajarieah M, Direkvand-Moghadam A. The Effect of Individual Factors, Socioeconomic and Social Participation on Individual Happiness: A Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research : JCDR. 2017;11(6):Vc01-vc4. [CrossRef]

- Barakat C, Konstantinidis T. A Review of the Relationship between Socioeconomic Status Change and Health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(13). [CrossRef]

- Ashida T, Kondo N, Kondo K. Social participation and the onset of functional disability by socioeconomic status and activity type: The JAGES cohort study. Preventive medicine. 2016;89:121-8. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Su D, Chen Y, Tan M, Chen X. Effect of socioeconomic status on the physical and mental health of the elderly: the mediating effect of social participation. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):605. [CrossRef]

- Achdut N, Sarid O. Socio-economic status, self-rated health and mental health: the mediation effect of social participation on early-late midlife and older adults. Israel journal of health policy research. 2020;9(1):4. [CrossRef]

- Uchino, BN. Social support and health: a review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. Journal of behavioral medicine. 2006;29(4):377-87. [CrossRef]

- Inagaki, TK. Neural mechanisms of the link between giving social support and health. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2018;1428(1):33-50. [CrossRef]

- Chang Q, Peng C, Guo Y, Cai Z, Yip PSF. Mechanisms connecting objective and subjective poverty to mental health: Serial mediation roles of negative life events and social support. Social science & medicine (1982). 2020;265:113308. [CrossRef]

- Moorman SM, Pai M. Social Support From Family and Friends, Educational Attainment, and Cognitive Function. J Appl Gerontol. 2024;43(4):396-401. [CrossRef]

- Adkins-Jackson PB, George KM, Besser LM, Hyun J, Lamar M, Hill-Jarrett TG, et al. The structural and social determinants of Alzheimer's disease related dementias. Alzheimers Dement. 2023;19(7):3171-85. [CrossRef]

- Wilding A, Munford L, Sutton M. Estimating the heterogeneous health and well-being returns to social participation. Health economics. 2023;32(9):1921-40. [CrossRef]

- Sharifian N, Grühn D. The Differential Impact of Social Participation and Social Support on Psychological Well-Being: Evidence From the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study. International journal of aging & human development. 2019;88(2):107-26. [CrossRef]

| Variables | Variable definition and assignment |

| Dependent variable | |

| Cognitive function | MoCA scores. Value range: 0-30 scores |

| Independent variables | |

| Income | Retire pension monthly. 1=less than 2000 yuan/month; 2=2000-6000 yuan/month; 3=more than 6000 yuan/month |

| Education | Educational scores. 1=less than 6 scores; 2=6-10 scores; 3=more than 10 scores. |

| Occupation | Occupational complexity scores. 1=less than 53 scores; 2=53-90 scores; 3=more than 90 scores. |

| Mediating variables | |

| Social participation | Scores. Value range:5-20 scores |

| Social support | Scores: value range: 12-84 scores |

| Covariates | |

| Age | 1=60-65 years old; 2=66-75 years old; 3=71-75 years old; 4=more than 75 years old. |

| Sex | 1=male; 2=female |

| Marital status | 1=married and living with a spouse; 2=separated (widowed or divorced) |

| Sleep quality | PSQI scores: 1=less than 5 scores; 2=5-10 scores; 3=more than 10 scores |

| Smoking status | 1=current smoking; 2=never or quit smoking |

| Drinking status | 1=current drink; 2=never or occasional drinking |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 1=less than 24; 2=more than or equal to 24. |

| Nutrition status | MNA scores: 1=less than 12 scores; 2=more than and equal to 12 |

| Co-morbidities | 1=none; 2=one chronic disease; 3=more than two diseases |

| Categorical measures | N (%) |

MoCA (scores) Mean (SD) |

P value | |

| Income (yuan/month) | <2000 | 205 (20.9%) | 18.06±5.60 | |

| 2000~6000 | 695 (71.0%) | 20.31±5.30 | ||

| >6000 | 79 (8.1%) | 22.40±5.08 | <0.001 | |

| Occupation (scores) | <53 | 325 (33.2%) | 19.12±5.86 | |

| 53~90 | 336 (34.2%) | 20.33±5.29 | ||

| >90 | 318 (32.5%) | 20.57±5.10 | 0.01 | |

| Education (scores) | <6 | 315 (32.2%) | 18.50±6.03 | |

| 6~10 | 330 (33.7%) | 20.85±4.61 | ||

| >10 | 331 (33.8%) | 20.56±5.40 | <0.001 | |

| Sex | Male | 413 (42.4%) | 20.14±5.40 | |

| Female | 564 (57.6%) | 19.91±5.50 | 0.501 | |

| Age (years) | 60~65 | 288 (29.4%) | 21.33±4.57 | |

| 66~70 | 336 (34.3%) | 20.48±4.89 | ||

| 71~75 | 169 (17.3%) | 19.99±5.61 | ||

| >75 | 185 (18.9%) | 17.07±6.44 | <0.001 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | <24 | 586 (59.9%) | 19.96±5.40 | |

| >=24 | 374 (38.2%) | 20.05±5.58 | 0.794 | |

| missing | 19 (1.9%) | |||

| Marital status | married | 848 (86.6%) | 20.33±5.27 | |

| separated | 131 (13.4%) | 17.89±6.13 | <0.001 | |

| Smoking | Yes | 177 (18.1%) | 20.67±4.85 | |

| No or quit | 802 (81.9%) | 19.86±5.58 | 0.050 | |

| Drinking | Yes | 154 (15.7%) | 20.90±4.71 | |

| No or quit | 825 (84.3%) | 19.84±5.57 | 0.014 | |

| Co-morbidities | None | 163 (16.6%) | 19.90±5.80 | |

| 1 | 375 (38.3%) | 20.09±5.43 | ||

| ≥2 | 242 (24.7%) | 19.39±5.64 | 0.311 | |

| missing | 199 (20.3%) | |||

| Nutrition status | <=12 | 30 (6.1%) | 19.32±5.67 | |

| (MNA, scores) | >12 | 465 (93.9%) | 20.29±5.35 | 0.011 |

| Sleep Quality | <5 | 573 (58.5%) | 20.63±5.26 | |

| (PSQI, scores) | 5~10 | 327 (33.4%) | 19.38±5.57 | |

| >10 | 79 (8.1%) | 18.12±5.72 | <0.001 | |

| Variables | Mean (SD) | Cognitive function (MoCA, scores) |

Social participation (scores) | Social support (scores) |

| Cognitive function (MoCA,scores) | 20.1 (5.46) | 1 | ||

| Social participation (scores) | 11.3 (4.1) | 0.350*** | 1 | |

| Social support (scores) | 59.1 (14.8) | 0.139*** | 0.169*** | 1 |

| Mediation variable | Independent variables | Dependent variable (cognitive function) | ||

| Omnibus total effect | Omnibus direct effect | Bootstrap 95% CI | ||

| Social participation | Income | 18.294*** | 12.759*** | 0.307~0.461 |

| Occupation | 8.487*** | 4.088** | 0.313~0.471 | |

| Education | 11.120*** | 7.481*** | 0.316~0.472 | |

| Social support | Income | 18.294*** | 16.301*** | 0.005~0.053 |

| Occupation | 8.487*** | 8.258*** | 0.013~0.058 | |

| Education | 11.120*** | 9.594*** | 0.008~0.054 | |

| Mediation variables | Socioeconomic conditions | Cognitive function | |||

| ci | aib | Bootstrap 95% CI | |aib/ci| | ||

| Social participation | Income (ref:<2000 yuan/month) | ||||

| 2000~6000 | 1.949*** | 0.358 | 0.110~0.614 | 18.36% | |

| >6000 | 3.799*** | 0.777 | 0.349~1.222 | 20.45% | |

| Occupation(ref:<53scores) | |||||

| 53~90 | 1.262** | 0.358 | 0.123~0.614 | 28.36% | |

| >90 | 1.574** | 0.561 | 0.299~0.851 | 35.64% | |

| Education (ref:<6 scores) | |||||

| 6~10 | 1.814*** | 0.311 | 0.058~0.572 | 17.14% | |

| >10 | 1.511*** | 0.562 | 0.294~0.853 | 39.19% | |

| Social support | Income (ref:<2000 yuan/month) | ||||

| 2000~6000 | 1.949*** | 0.132 | 0.019~0.282 | 6.77% | |

| >6000 | 3.799*** | 0.160 | 0.017~0.372 | 4.21% | |

| Occupation(ref:<53scores) | |||||

| 53~90 | 1.262** | 0.011 | -0.073~0.103 | -- | |

| >90 | 1.574** | 0.034 | -0.042~0.132 | -- | |

| Education (ref:<6 scores) | |||||

| 6~10 | 1.814*** | 0.096 | 0.013~0.214 | 5.29% | |

| >10 | 1.511*** | 0.156 | 0.035~0.318 | 10.32% | |

| Relative direct effects | β | S.E | t | P | 95%CI of β | |

| LLCI | ULCI | |||||

| Income (refer=low income level) | ||||||

| Medium income →social support | 4.610 | 1.144 | 4.029 | <0.001 | 2.365 | 6.855 |

| Medium income →social participation | 0.760 | 0.319 | 2.384 | 0.017 | 0.134 | 1.385 |

| Medium income →cognitive function | 1.531 | 0.394 | 3.887 | <0.001 | 0.758 | 2.303 |

| High income →social support | 5.605 | 1.937 | 2.894 | 0.004 | 1.805 | 9.406 |

| High income →social participation | 1.813 | 0.537 | 3.373 | 0.001 | 0.758 | 2.868 |

| High income →cognitive function | 2.954 | 0.666 | 4.437 | <0.001 | 1.647 | 4.261 |

| Social support →social participation | 0.037 | 0.009 | 4.175 | <0.001 | 0.020 | 0.055 |

| Social support →cognitive function | 0.015 | 0.011 | 1.321 | 0.184 | -0.007 | 0.036 |

| Social participation →cognitive function | 0.378 | 0.04 | 9.535 | <0.001 | 0.300 | 0.455 |

| Occupation (refer=low level of occupation complexity) | ||||||

| Medium occupation →social support | 0.313 | 1.123 | 0.278 | 0.781 | -1.891 | 2.516 |

| Medium occupation →social participation | 0.898 | 0.307 | 2.928 | 0.003 | 0.296 | 1.499 |

| Medium occupation →cognitive function | 0.907 | 0.383 | 2.366 | 0.018 | 0.155 | 1.660 |

| High occupation →social support | 0.956 | 1.137 | 0.841 | 0.401 | -1.276 | 3.188 |

| High occupation→ social participation | 1.387 | 0.311 | 4.465 | <0.001 | 0.777 | 1.997 |

| High occupation →cognitive function | 1.010 | 0.391 | 2.583 | 0.010 | 0.243 | 1.776 |

| Social support →social participation | 0.040 | 0.009 | 4.559 | <0.001 | 0.023 | 0.057 |

| Social support →cognitive function | 0.020 | 0.011 | 1.841 | 0.066 | -0.001 | 0.042 |

| Social participation →cognitive function | 0.383 | 0.040 | 9.562 | <0.001 | 0.304 | 0.461 |

| Education (refer=low educational level) | ||||||

| Medium education →social support | 3.108 | 1.138 | 2.732 | 0.006 | 0.875 | 5.341 |

| Medium education →social participation | 0.676 | 0.316 | 2.141 | 0.033 | 0.056 | 1.296 |

| Medium education →cognitive function | 1.456 | 0.392 | 3.713 | <0.001 | 0.687 | 2.226 |

| High education →social support | 5.043 | 1.138 | 4.431 | <0.001 | 2.810 | 7.276 |

| High education →social participation | 1.241 | 0.318 | 3.906 | <0.001 | 0.618 | 1.865 |

| High education →cognitive function | 0.874 | 0.397 | 2.203 | 0.028 | 0.096 | 1.653 |

| Social support →social participation | 0.036 | 0.009 | 4.044 | <0.001 | 0.019 | 0.053 |

| Social support →cognitive function | 0.017 | 0.011 | 1.529 | 0.127 | -0.005 | 0.039 |

| Social participation →cognitive function | 0.387 | 0.040 | 9.704 | <0.001 | 0.309 | 0.465 |

| Socioeconomic conditions | Mediation path | Cognitive function | |||

| ci | aib | Bootstrap 95% CI of aib | |aib/ci| | ||

| Income (ref: low income level) | |||||

| Medium level | Social support | 1.949*** | 0.067 | -0.032~0.193 | --- |

| Social participation | 1.949*** | 0.287 | 0.042~0.539 | 14.7% | |

| Social support→social participation | 1.949*** | 0.065 | 0.025~0.115 | 3.3% | |

| High level | Social support | 3.799*** | 0.082 | -0.038~0.243 | --- |

| Social participation | 3.799*** | 0.685 | 0.261~1.136 | 18.0% | |

| Social support→social participation | 3.799*** | 0.078 | 0.023~0.152 | 2.0% | |

| Occupation (ref: low level of occupation complexity) | |||||

| Medium level | Social support | 1.262** | 0.006 | -0.047~0.070 | --- |

| Social participation | 1.262** | 0.344 | 0.117~0.591 | 27.3% | |

| Social support→social participation | 1.262** | 0.005 | -0.030~0.044 | --- | |

| High level | Social support | 1.574** | 0.019 | -0.028~0.090 | --- |

| Social participation | 1.574** | 0.531 | 0.277~0.824 | 33.7% | |

| Social support→social participation | 1.574** | 0.015 | -0.019~0.055 | --- | |

| Education (ref: low educational level) | |||||

| Medium level | Social support | 1.814*** | 0.053 | -0.013~0.150 | --- |

| Social participation | 1.814*** | 0.262 | 0.020~0.515 | 14.4% | |

| Social support→social participation | 1.814*** | 0.043 | 0.010~0.089 | 2.4% | |

| High level | Social support | 1.511*** | 0.086 | -0.022~0.223 | --- |

| Social participation | 1.511*** | 0.480 | 0.224~0.761 | 31.8% | |

| Social support→social participation | 1.511*** | 0.070 | 0.027~0.129 | 4.6% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).