Submitted:

29 May 2023

Posted:

30 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

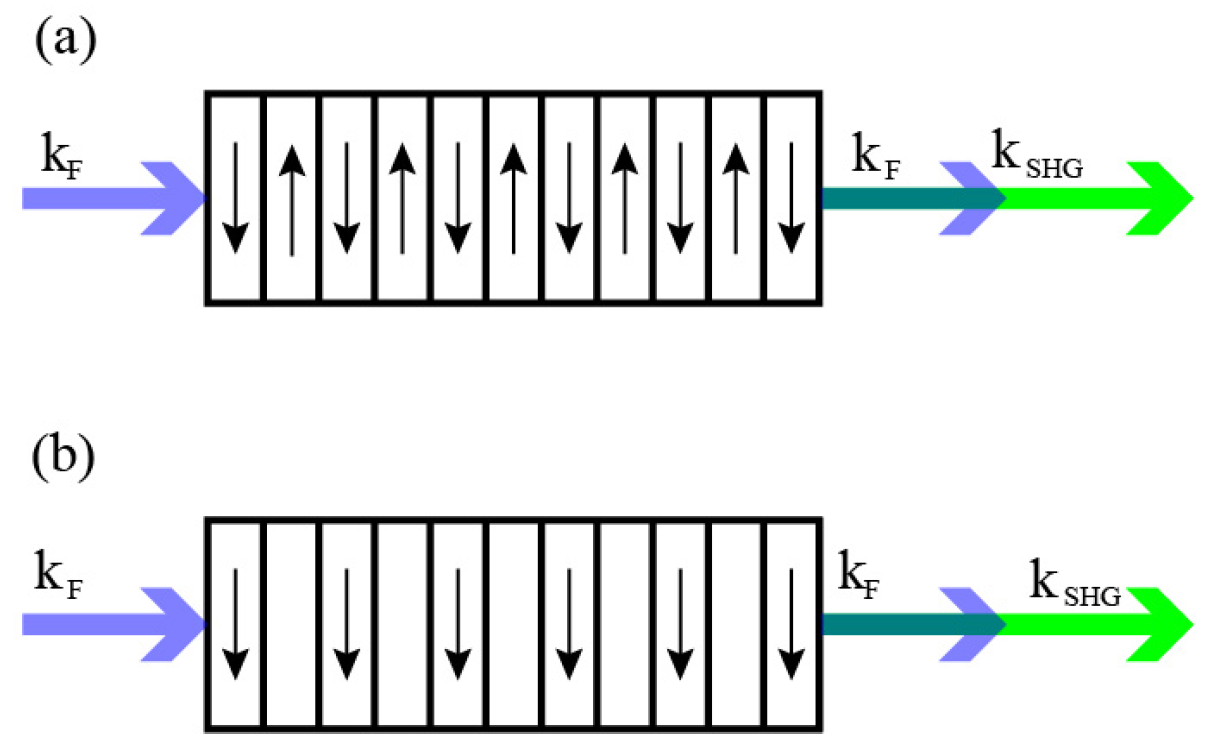

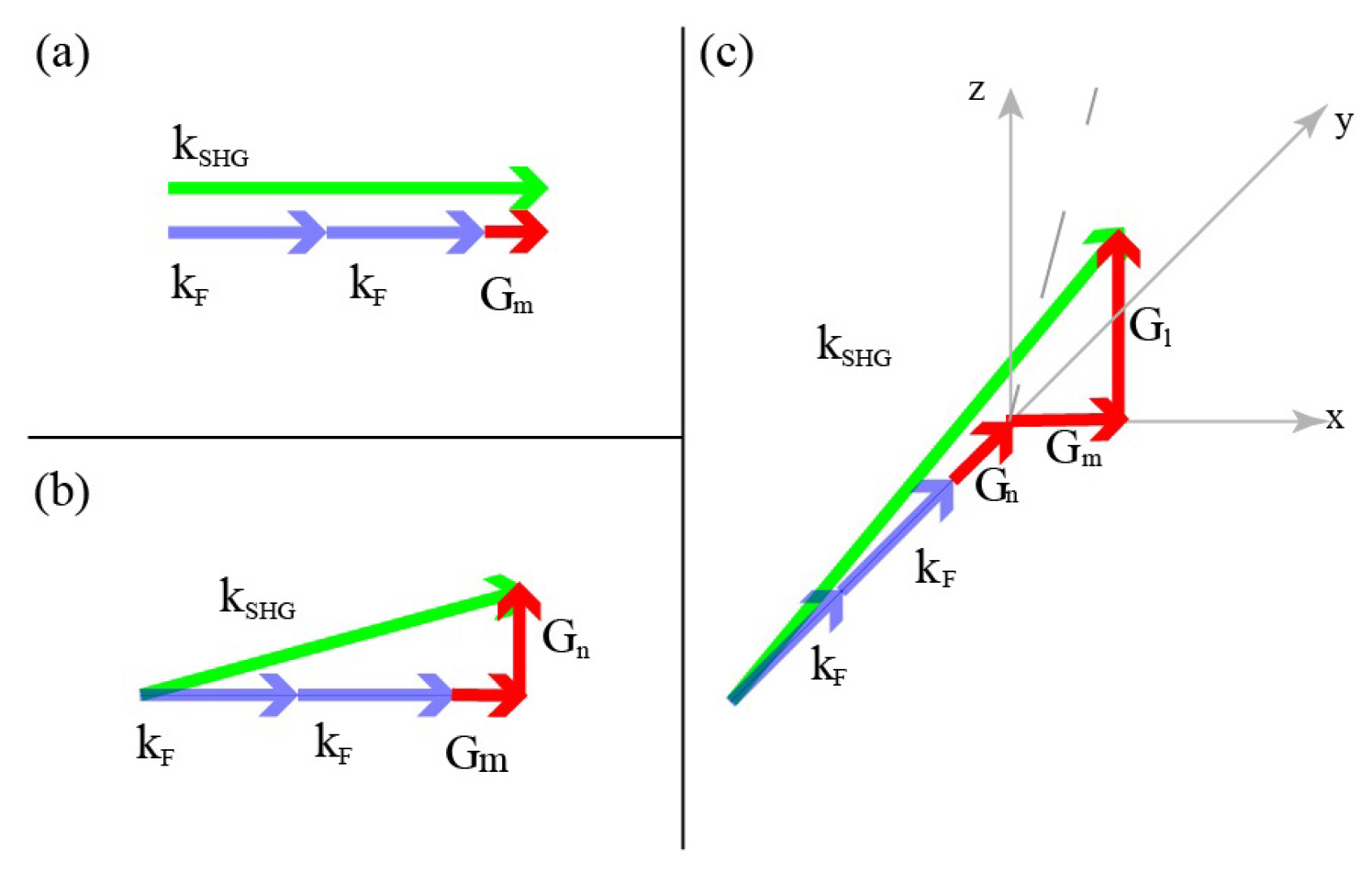

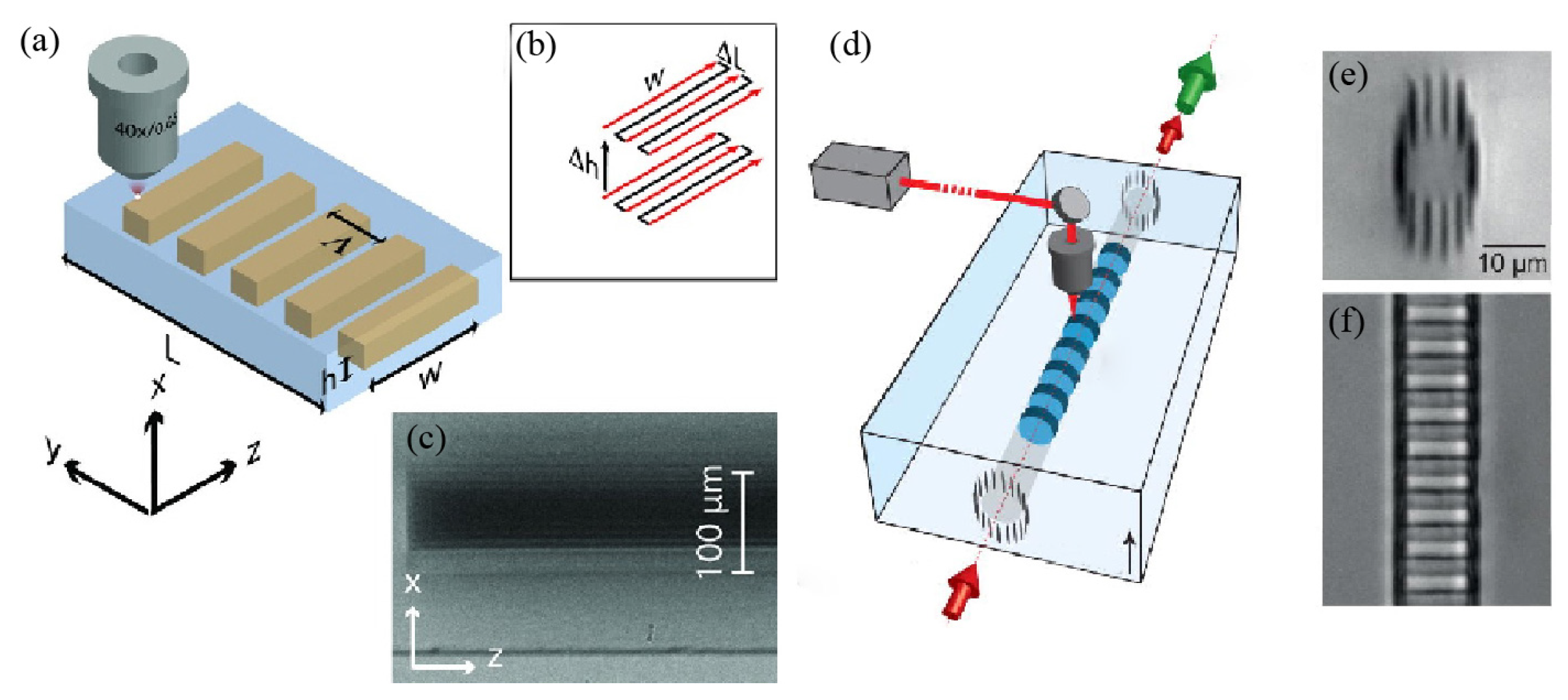

2. -erasing technique by femtosecond laser

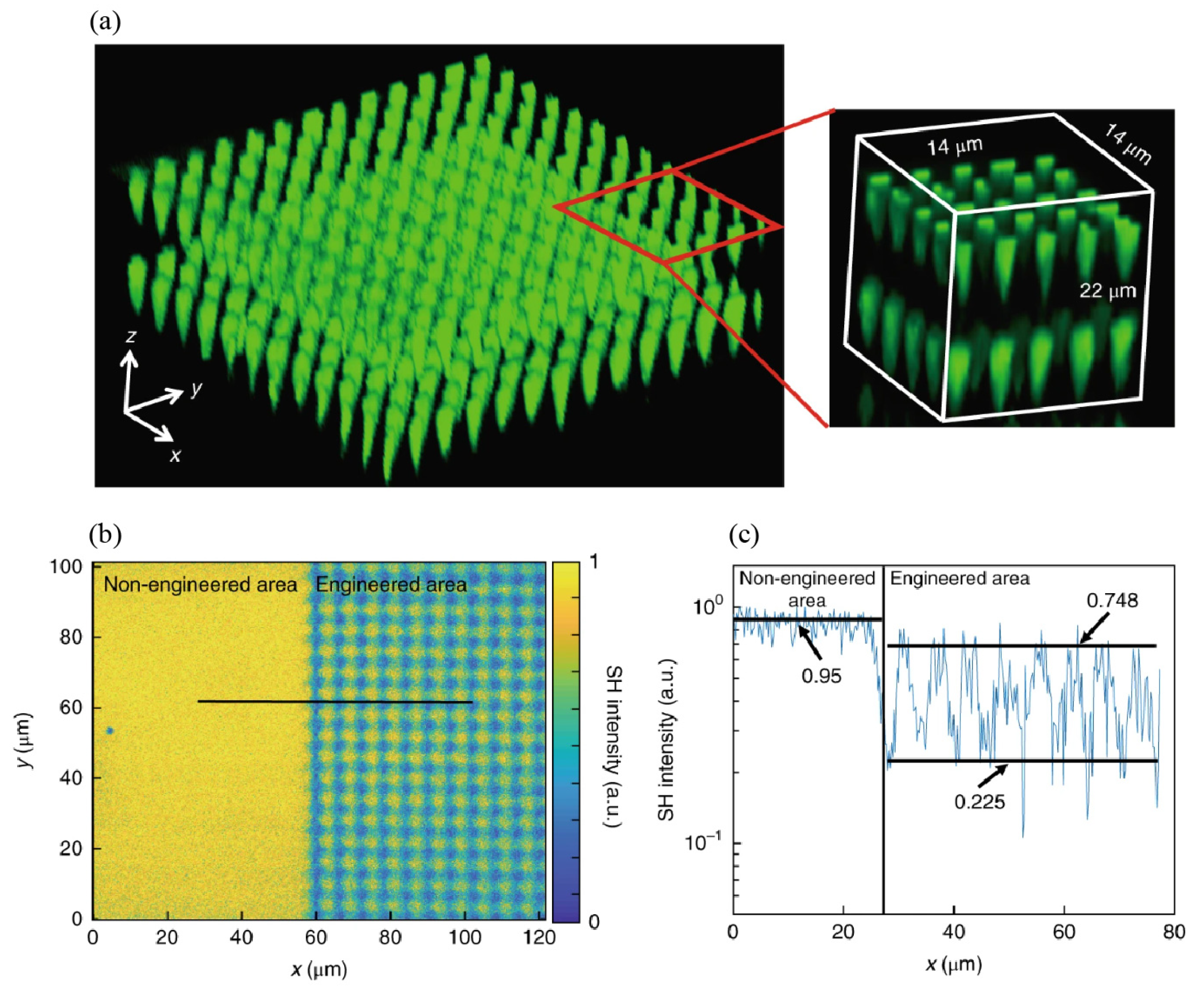

3. -poling technique by femtosecond laser

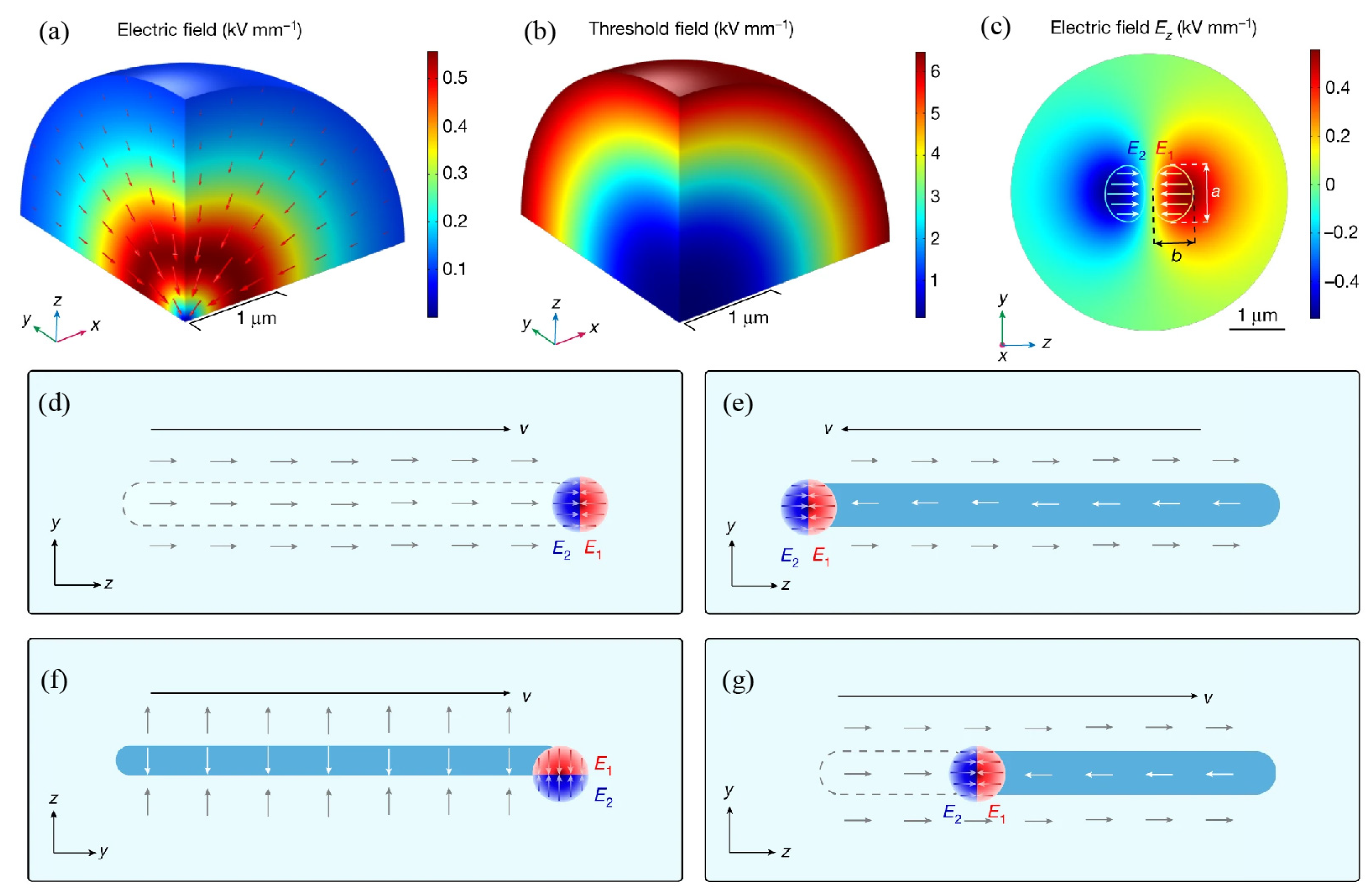

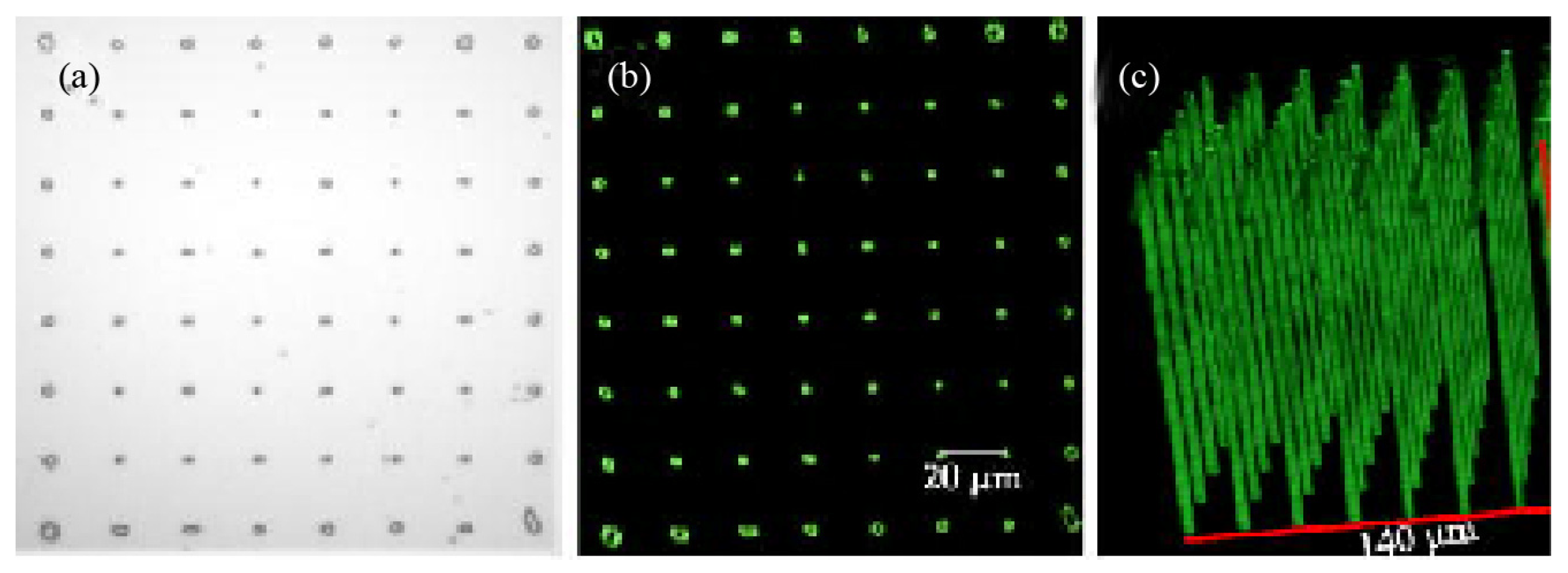

3.1. The primary domain inversion:

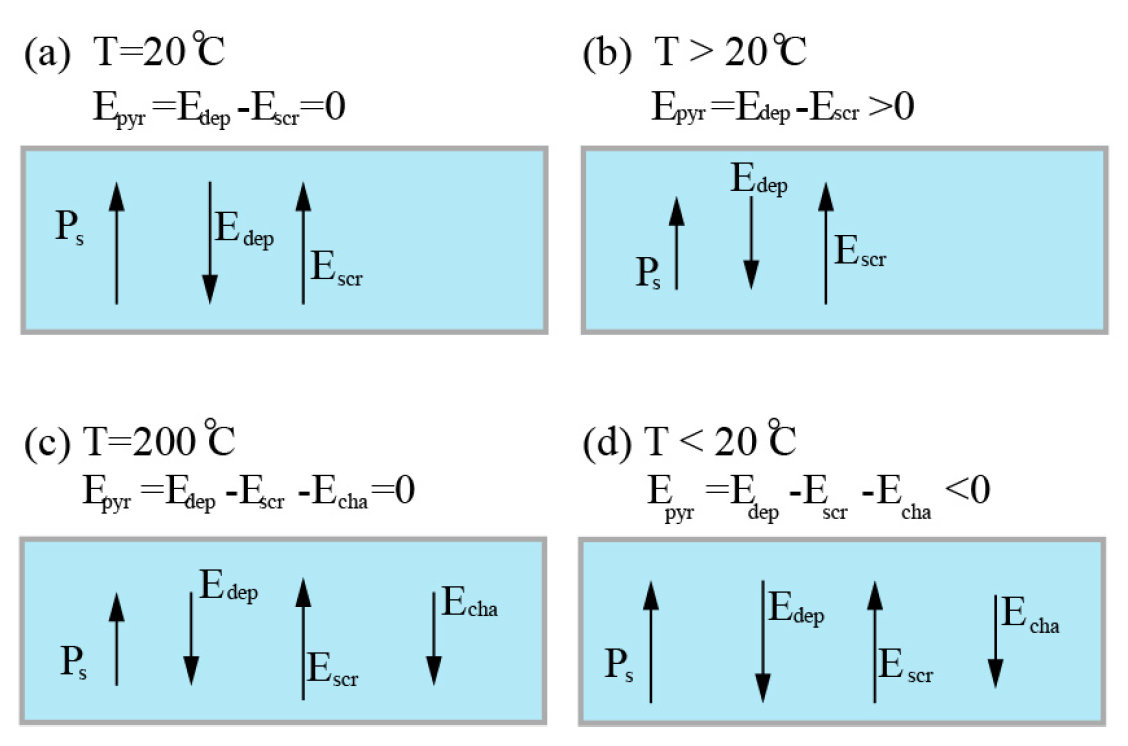

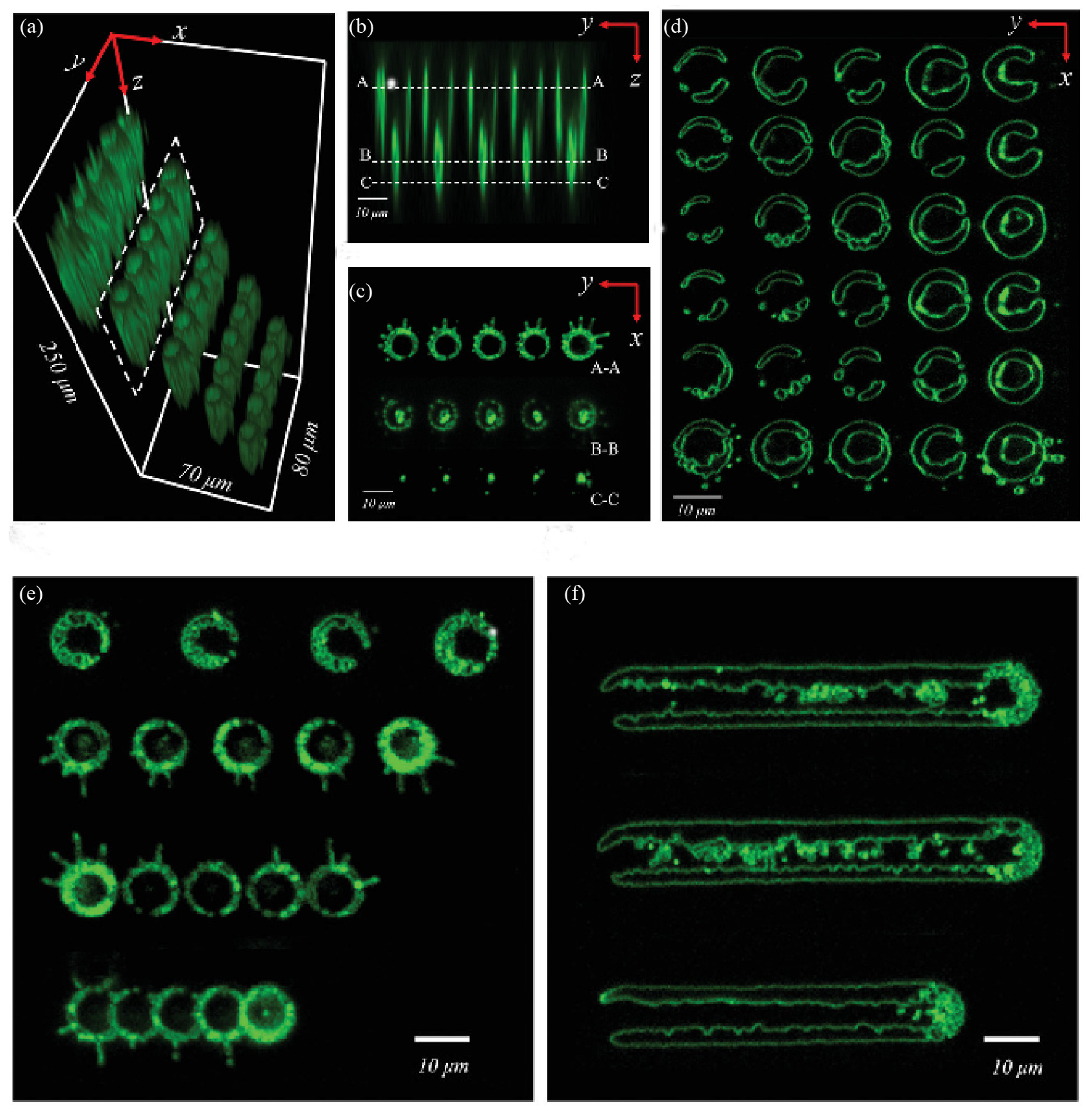

3.2. The secondary domain inversion

3.3. Two types of domain inversion showing up simultaneously

4. Laser writing parameters

5. Conclusion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 1D | One-dimensional |

| 2D | Two-dimensional |

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

| SHG | Secpnd harmonic generation |

| DFG | Difference-frequency generation |

| SFG | Summer-frequency generation |

| OPO | Optical parametric generation |

| SH | Second harmonic |

| BPM | Birefringence Phase Matching |

| QPM | Quasi-phase matching |

| RVL | reciprocal vector |

| PPLN | Periodically poled lithium noibate |

| NPC | Nonlinear photonic crystal |

| PC | Photonic crystal |

References

- Wu, A.; Xu, J.; Zheng, Y. and Liang, X. Crystal growth and application of large size YCOB crystal for high power laser. Opt. Mater. 2014, 36, 12, 2000–2003. [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, N.; Balla, N.K.; Zhuo, G.; Kistenev, Y.V.; Kumar, R.; Kao, F.; Brasselet, S.; Nikolaev, V.V.; and Krivova, N.A. Label-free nonlinear multimodal optical microscopy–basics, development, and applications. Frontiers in Physics 2019, 7, 170. [CrossRef]

- Gibson, G.; Courtial, J.; Padgett, M.J, Vasnetsov, M.; Pas’ko, V.; Barnett, S.M. and Franke-Arnold, S. Free-space information transfer using light beams carrying orbital angular momentum. Opt. Express 2019, 12, 22, 5448–5456. [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.H.; Yang, B.; Zhang, C.; Qin, Y.Q.; and Zhu,Y.Y. Nonlinear volume holography for wave-front engineering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 113, 163902. [CrossRef]

- Bowman, P.M.; and Bowman, R. Tweezers with a twist. Nature Photon, 2003, 5, 343–348. [CrossRef]

- Grier, D.G. A revolution in optical manipulation. Nature, 2003, 424, 810–816. [CrossRef]

- Vaziri, A.; Pan, J.W.; Jennewein, T.; Weihs, G.; Zeilinger, A. Concentration of higher dimensional entanglement: Qutrits of photon orbital angular momentum. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003, 91, 227902. [CrossRef]

- Leng, H.Y.; Yu, X.Q.; Gong, Y.X.; Xu, P.; Xie, Z.D.; Jin, H.; Zhang, C. and Zhu, S.N. On-chip steering of entangled photons in nonlinear photonic crystals. Nat Commun 2011, 2, 429. [CrossRef]

- Powers, P.E.; Haus, J.W. ; Chapter 5: Quasi-phase matching. In Fundamental of nonlinear optics; ed. Liu, H.; CRC Press: Beijing, China, 2020; pp. 161–181. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, J.A.; Bloembergen, N.; Ducuing, J.; and Pershan, P.S. Interactions between light waves in a nonlinear dielectric. Phys. Rev. 1962, 127, 1918. [CrossRef]

- Franken, P.A.; Hill, A.E.; Peters, C.W.; Weinreich, G. Generation of optical harmonics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1961, 7, 118. [CrossRef]

- Franken, P.A. and Ward, J.F. Optical harmonic and nonlinear phenomena. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1963, 35, 23. [CrossRef]

- Fejer, M.M.; Magel, G.A.; Jundt, D.H. and Byer, R.L. Quasi-phase-matched second harmonic generation: tuning and tolerances. IEEE J. Quantum Elect. 1992, 28, 11, 2631–2654. [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.H.; Ming, N.B.; Zhu, J.S. and Feng, D. The second harmonic generation in LiNbO3 crystals with period laminar ferroelectric domains. Chinese Phys. 1984, 4, 554–564. [CrossRef]

- Feisst, A. and Koidl, P. Current induced periodic ferroelectric domain structures in LiNbO3 applied for efficient nonlinear optical frequency mixing. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1985, 47,1125–1127. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.S.; Zhou, Q.; Geng, Z.H. and Feng, D. Study of LiTaO3 crystals grown with a modulated structure I. second harmonic generation in LiTaO3 crystals grown with period laminar ferroelectric domains. Journal of Crystal Growth 1986, 79, 706–709. [CrossRef]

- Shur, V. Y.; Akhmatkhanov , A.R. and Baturin, I.S. Micro- and nano-domain engineering in lithium niobate. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2015, 2, 040604. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Chen, P.; Xu, Ch.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, D.; Hu, X.; Zhao, G.; Xiao,M. and Zhu, S. Periodically poled LiNbO3 crystals from 1D and 2D to 3D. Sci. China Technol SC 2020, 63, 7, 1110–1126. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.L.; Lu, Y.Q. ; Xue, C.C.; Ming, N.B. Growth of Nd3+-doped LiNbO3 optical superlattice crystals and its potential applications in self-frequency doubling. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1996, 68, 1467–1469. [CrossRef]

- Zheng,J.J.; Lu, Y.Q.; Luo,G.P.; Ma, J.; Lu, Y.L.; Ming, N.B.; He, J.L.; Xu, Z.Y. Visible dual-wavelength light generation in optical superlattice Er:LiNbO3 through upconversion and quasi-phase-matched frequency doubling. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1998, 72, 1808–1810. [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.X.; Lu, D.Z.; Yu, H.H.; Zhang, H.J.; Zhang, Y. Wang, J.Y. A naturally grown three-dimensional nonlinear photonic crystal. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2016, 108, 051907. [CrossRef]

- Rosenman, G.; Urenski, P.; Agronin, A.; Rosenwaks, Y.; Molotskii, M. Submicron ferroelectric domain structures tailored by high-voltage scanning probe microscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2003, 82, 103–105. [CrossRef]

- Yamada, M. and Kishima, K. Fabrication of periodically reversed domain structure for SHG in LiNbO3 by direct electron beam lithography beam lithography at room teperature. Electronics Letters 1991, 27, 828–829. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, W.; Gupta, M.C. Domain inversion in LiTaO3 by electron beam. Appl. Phys. Lett.1992, 60, 1–3. [CrossRef]

- Muir, A. C.; Sones, C.L.; Mailis, S.; Eason, R.W.; Jungk, T.; Hoffmann, Á.; Soergel, E.; Direct-writing of inverted domains in lithium niobate using a continuous wave ultra violet laser. Opt. Express 2008, 162336–2350. [CrossRef]

- Boes, A.; Steigerwald, H.; Crasto, T.; Wade, S.A.; Limboeck,T.; Soergel, E. and Mitchell, A. Tailor-made domain structures on the x- and y-face of lithium niobate crystals. Appl. Phys. B, 2014, 115, 577–581. [CrossRef]

- Berger, V. Nonlinear photonic crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1998, 81, 4136. [CrossRef]

- John, S. Strong localization of photons in certain disordered dielectric superlattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1987, 58, 2486–2489. [CrossRef]

- Yablonovitch, E. Inhibited spontaneous emission in solid-state physics and electronics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1987, 58, 2059–2062. [CrossRef]

- Saltiel, S. M.; Neshev, D.N.; Fischer, R.; Krolikowski, W.; Arie, A.; Kivshar, Y.S. Generation of second-harmonic conical waves via nonlinear bragg diffraction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 103902. [CrossRef]

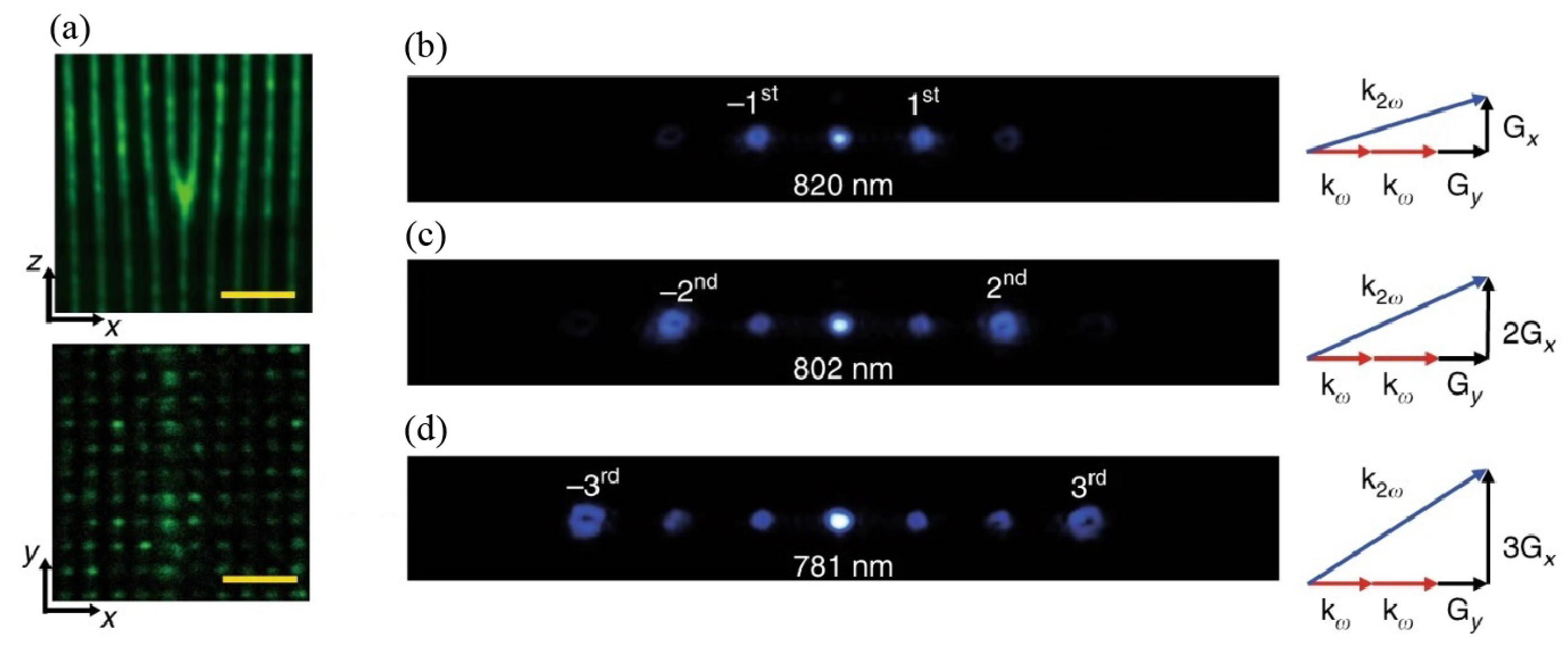

- Saltiel, S.M.; Neshev, D.N.; Krolikowski, W.; Arie, A.; Bang, O.; Kivshar, Y.S. Multiorder nonlinear diffraction in frequency doubling processes. Opt. Lett. 2009, 34 848–850. [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Y.; Kong, Q.; Roppo, V.; Kalinowski, K.; Wang, Q.; Cojocaru, C.; Krolikowski, W. Theoretical study of Čerenkov type second-harmonic generation in periodically poled ferroelectric crystals.J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 2012, 29, 312–318. [CrossRef]

- Kurz, J.R.; Schober, A.M.; Hum, D.S.; Saltzman, A.J. and Fejer, M.M. Nonlinear physical optics with transversely patterned quasi-phase matching gratings. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron 2002, 8, 377–378. [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Ji, S.H.; Zhu, S.N.; Yu, X.Q.; Sun, J.; Wang, H.T.; He, J.L.; Zhu, Y.Y.; and Ming, N.B. Conical second harmonic generation in a two dimensional photonic crystal: a hexagonally poled LiTaO3 crystal. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004, 93, 133904. [CrossRef]

- Trajtenberg-Mills, S.; Juwiler, I. and Arie, A. On-axis shaping of second-harmonic beams. Laser Photon. Rev. 2015, 9, L40–L44. [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Xu, P.; Luo, X.W.; Leng, H.Y.; Gong, Y.X.; Yu, W.J.; Zhong, M.L.; Zhao, G.; Zhu, S.N. Compact engineering of path-entangled sources from a monolithic quadratic nonlinear photonic crystal. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 111, 023603. [CrossRef]

- Trajtenberg-Mills, S.; Karnieli, A.; Voloch-Bloch, N.; Megidish, E.; Eisenberg, H.S.; Arie, A. Simulating correlations of structured spontaneously down-converted photon pairs. Laser Photonics Rev. 2020, 14, 1900321. [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.D.; Zhu, L.; Chen, S.; Du, C.; Mo, Q.; Wang, J. Characterization of LDPC-coded orbital angular momentum modes transmission and multiplexing over a 50-km fiber. Opt. Express 2016, 24, 11716–11726. [CrossRef]

- Yamada, M.; Nada, N.; Saitoh, M. and Watanabe, K. First order quasi-phase matched LiNbO3 waveguide periodically poled by applying an external field for efficient blue second harmonic generation. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1993, 62, 435-436. [CrossRef]

- Broderick, N.G.R.; Ross, G.W.; Offerhaus, H.L.; Richardson, D.J. and Hanna, D.C. Hexagonally poled lithium niobate: a two-dimensional nonlinear photonic crystal. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 84, 4345–4348. [CrossRef]

- Mizuuchi, K.; Morikawa, A.; Sugita, T. and Yamamoto, K. Electric-field poling in Mg-doped LiNbO3. J. Appl. Phys. 2004, 96, 6585–6590. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, L. and Chen, F. Recent advances in femtosecond laser processing of LiNbO3 crystals fir photonics applications. Laser Photonivs Rev. 2000, 14, 8, 1900407. [CrossRef]

- Lin, J. T.; Bo, F.; Cheng, Y.; Xu,J.J. Advances in on-chip photonic devices based on lithium niobate on insulator. Photonics Research 2020, 8, 12, 1910-1936. [CrossRef]

- Stoian, R.; Amico, C.D.; Bhuyan, M.K.; Cheng, G. [INVITED] Ultrafast laser photoinscription of large-mode-area waveguiding structures in bulk dielectrics. Opt. Laser Technol. 2016, 80, 98–103. [CrossRef]

- Stuart, B. C.; Feit, M.D.; Herman, S.; Rubenchik, A. M. ; Shore, B. W. and Perry, M. D. Nanosecond-to-femtosecond laser-induced breakdown in dielectrics. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 53, 1749. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Miura, K.; Hirao, K. Three-dimensional optical memory using glasses as a recording medium through a multi-photon absorption process. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 1998, 37, 2263. [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.W. ; Huser, T.; Risbud, S.; Krol, D.M. Structural changes in fused silica after exposure to focused femtosecond laser pulses. Opt. Lett. 2001, 26, 21, 1726–1728. [CrossRef]

- Gorelik, T.; Will, M.; Nolte, S.; Tuennermann, A.; Glatzel, U. Transmission Electron Microscopy Studies of Femtosecond Laser Induced Modifications in Quartz. Appl. Phys. A 2003, 76, 309–311. [CrossRef]

- Couairon, A.; Sudrie, L.; Franco, M.; Prade, B.; Mysyrowicz, A. Filamentation and damage in fused silica induced by tightly focused femtosecond laser pulse. Phys. Rev. B 2005, 71, 125435. [CrossRef]

- Reichman, W.J.; Chan, J.W.; Smelser, S.W.; Mihailov, S.J.; Krol, D.M. Spectroscopic characterization of different femtosecond laser modification regimes in fused silica. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 2007, 24, 1627–1632. [CrossRef]

- Little, D.J.; Ams, M.; Dekker, P.; Marshall, G.D.; Dawes, J.M.; Withford, M.J. Femtosecond laser modification of fused silica: the effect of writing polarization on Si-O ring structure. Opt. Express 2008, 16, 20029–20037. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shimizu, M.; Zhu, B.; Dai, Y.; Qian, B.; Qiu, J.R.; Shimotsuma, Y.; Miura, K.; Hirao, K. Micromodification of element distribution in glass using femtosecond laser irradiation. Opt. Lett. 2009, 34, 2, 136–138. [CrossRef]

- Mishchik, K.; Cheng, G.; Huo, G.; Burakov, I.M.; Mauclair, C.; Mermillod-Blondin, A.; Rosenfeld, A.; Ouerdane, Y.; Boukenter, A.; Parriaux, O.; Stoian, R. Nanosize structural modifications with polarization functions in ultrafast laser irradiated bulk fused silica. Opt. Express 2010, 18, 24809-24824. [CrossRef]

- Lancry, M.; Poumellec, B.; Chahid-Erraji, A.; Beresna, M.; Kazansky, P.G. Dependence of the femtosecond laser refractive index change thresholds on the chemical composition of doped-silica glasses. Opt. Mat. Express 2011, 1, 711–723. [CrossRef]

- Toney Fernandez, T.; Haro-González, P.; Sotillo, B.; Hernandez, M.; Jaque, D.; Fernandez, P.; Domingo, C.; Siegel, J.; Solis, J. Ion migration assisted inscription of high refractive index contrast waveguides by femtosecond laser pulses in phosphate glass. Opt. Lett. 2013, 38, 5248–5251. [CrossRef]

- Stuart, B.C.; Feit, M.D.; Rubenchik, A.M.; Shore, B.W. and Perry, M.D. Laser-Induced Damage in Dielectrics with Nanosecond to Subsecond Pulses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1995,74, 2248–2251. [CrossRef]

- Yamada, K.; Watanabe, W.; Toma, T. and Itoh, K. In situ observation of photoinduced refractive-index changes in filaments formed in glasses by femtosecond laser pulses. Opt. Lett. 2001, 26, 19–21. [CrossRef]

- Ponader, C.W.; Schroeder, J.F.; Streltsov, A.M. Origin of the refractive-index increase in laser-written waveguides in glasses. J. Appl. Phys. 2008, 103, 6, 063516. [CrossRef]

- Glezer, E.N.; Milosavljevic, M.; Huang, L.; Finlay, R.J.; Her, T.-H.; Callan, J.P. and Mazur, E. Three-Dimensional Optical Storage Inside Transparent Materials. Opt. Lett. 1996, 21, 2023–2025. [CrossRef]

- Eberlea, G.; Schmidtb, M.; Pudec, F.; Wegenera, K. Laser surface subsurface of sapphireusing femtosecond pulses. Appl. Sur. Sci. 2016, 378, 504–512. [CrossRef]

- Kroesen, S.; Horn, W.; Imbrock, J. and Denz, C. Electro-optical tunable waveguide embeded multiscan Bragg grattings in Lithium niobate by direct femtosecond laser writting. Opt. Express 2014, 22, 23339–23348. [CrossRef]

- Shivakumar V.B.; Jedrkiewicz, O.; Hadden, J.P.; Sotillo, B.; Vázquez, M.R.; Dentella, P.; Fernandez, T.T.; Chiappini, A.; Giakoumaki, A.N.; Phu, T.L.; Bollani, M.; Ferrari, M.; Ramponi, R.; Barclay, P.E. and Eaton, S.M. Femtosecond laser written photonic and microfluidic circuits in diamond. J. Phys. Photonics 2019, 1, 022001. [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.M.; Miura, K.; Sugimoto, N. and Hirao, K. Writing waveguides in glass with a femtosecond laser. Opt. Lett. 1996, 21, 1729–1731. [CrossRef]

- Miura, K.; Qiu, J.R.; Inouye, H. and Mitsuyu, T. Photowritten optical waveguides in various glasses with ultrashort pulse laser. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1997, 71, 3329–3331. [CrossRef]

- Burghoff, J.; Grebing, C.; Nolte, S.; Tünnermann, A. Waveguides in lithium niobate fabricated by focused ultrashort laser pulses. Appl. Sur. Sci. 2007, 253, 7899–7902. [CrossRef]

- Burghoff, J.; Nolte, S.; Tünnermann, A. Origins of waveguiding in femtosecond laser-structured LiNbO3. Appl. Phys. A 2007, 89, 127–132. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, S.; Thomson, R.R.; Hand, D.P.; Kar, A.K.; Reid, D.T.; Canalias, C.; Pasiskevicius,V. and Laurell, F. Frequency-doubling in femtosecond laser inscribed periodically-poled potassium titanyl phosphate waveguides. Opt. Express 2007, 15, 17146–17150. [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.C.; Vázquez de Aldana, J.R.; Lu, Q.M.; Jaque, D. and Chen, F. Second harmonic generation of violet light in femtosecond-laser-inscribed BiB3O6 cladding waveguides. Opt. Mat. Express, 2013, 3, 1279–1284. [CrossRef]

- Hasse, K.; Calmano, T.; Deppe, B.; Liebald, C.; Kränkel, C. Efficient Yb+3CaGdAlO4 bulk and Femtosecond Laser-written Waveguide Lasers. Opt. Lett. 2015, 40, 15, 3552–3555. [CrossRef]

- Mishchik, K.; D’Amico, C.; Velpula, P.K.; Mauclair, C.; Boukenter, A.; Ouerdane, Y. and Stoiana, R. Ultrafast laser induced electronic and structural modifications in bulk fused silica. J. Appl. Phys. 2013, 114, 13, 133502. [CrossRef]

- Glezer, E.N.; Mazur, E. Ultrafast-laser driven micro-explosions in transparent materials. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1997, 71, 882–884. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Hilbert, V.; Geiss, R.; Pertsch, T.; Tünnermann, A.; Nolte, S. Quasi phase matching in femtosecond pulse volume structured x-cut lithium niobate. Laser Photon. Rev. 2013, 7, L17–L20. [CrossRef]

- Kroesen, S.; Tekce, K.; Imbrock, J. and Denz, C. Monolithic fabrication of quasi phase-matched waveguides by femtosecond laser structuring the χ(2) nonlinearity. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015, 107, 101109. [CrossRef]

- Imbrock, J.; Wesemann, L.; Kroesen, S.; Ayoub, M. and Denz, C. Waveguide-integrated three-dimensional quasi-phase-matching structures. Optica 2020, 7, 28–34. [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Wang, C.; Wang, H.; Hu, X.; Wei, D.; Fang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, D.; Hu, Y.; Li, J.; Zhu, Sh.; Xiao, M. Experimental demonstration of a three-dimensional lithium niobate nonlinear photonic crystal. Nature Photon 2018, 12, 596–600. [CrossRef]

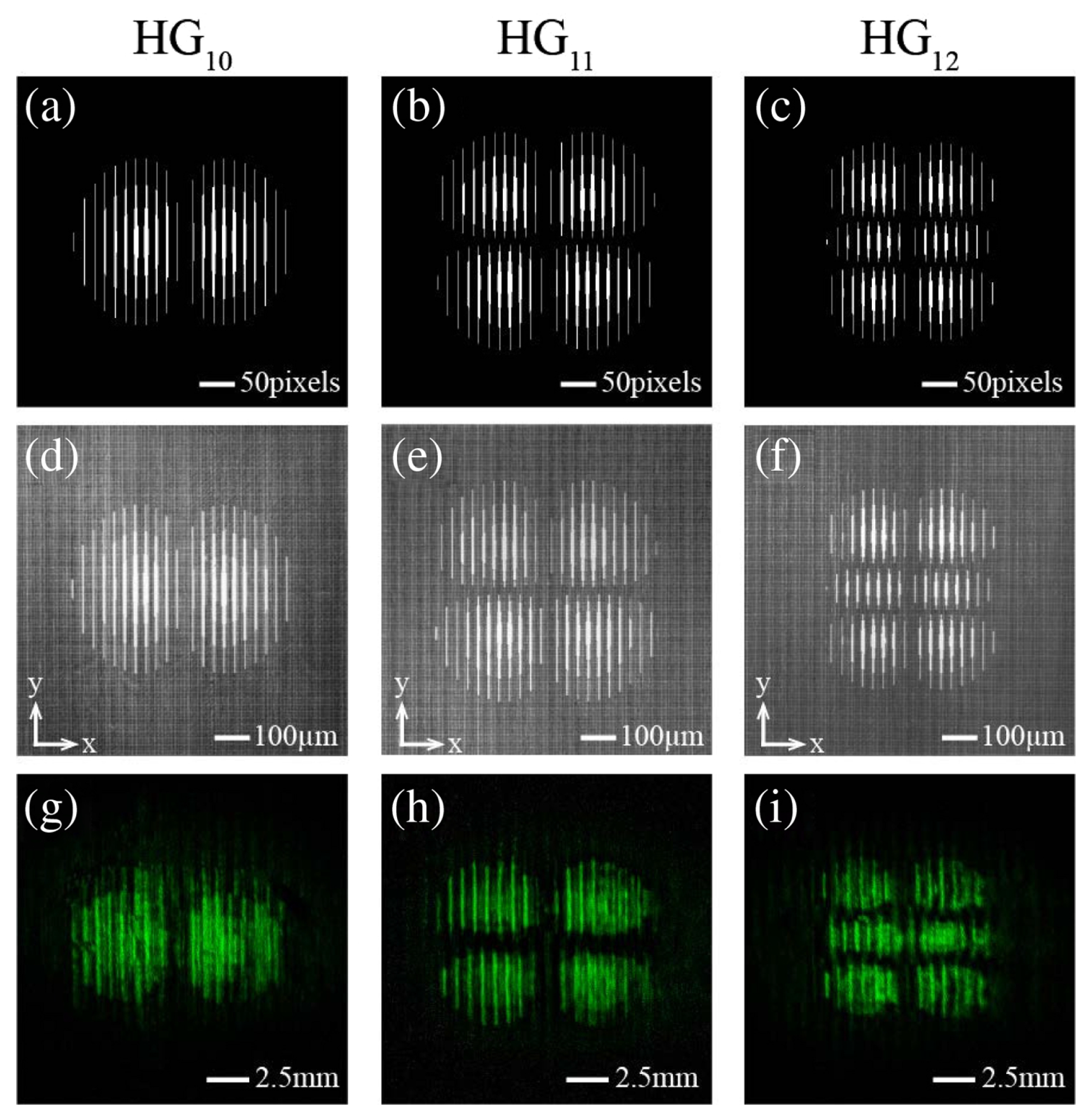

- Wei, D.; Wang, C.; Xu, X.; Wang, H.; Hu, Y.; Chen, P.; Li, J.; Zhu, Y.; Xin, C.; Hu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, D.; Chu, J.; Zhu, S.; Xiao, M. Efficient nonlinear beam shaping in three-dimensional lithium niobate nonlinear photonic crystals. Nat. Commun 2019, 10, 4193. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Liu, H.G.; Chen, Y.P. and Chen, X.F. High conversion efficiency second-harmonic beam shaping via amplitude-type nonlinear photoniccrystals. Opt. Lett. 2019, 45, 220–223. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Liu, H.G.; Liu, Y.A.; Yan, X.S.; Chen, Y.P. and Chen, X.F. Second-harmonic computer-generated holographic imaging through monolithic lithium niobate crystal by femtosecond laser micromachining. Opt. Lett. 2020, 45, 4132–4135. [CrossRef]

- Shao, M.; Liang, F.; Yu, H. and Zhang, H. Pushing periodic-disorder induced phase matching into the deep-ultraviolet spectral region: theory and demonstration. Light Sci Appl 2020, 9, 45. [CrossRef]

- Shao, M.; Liang, F.; Yu, H. and Zhang, H. Angular engineering strategy of an additional periodic phase for widely tunable phase-matched deep-ultraviolet second harmonic generation. Light Sci Appl 2022, 11, 31, 2047–7538. [CrossRef]

- Fujimura, M.; Sohmura, T. and Suhara, T. Fabrication of domain-inverted gratings in MgO:LiNbO3 by applying voltage under ultraviolet irradiation through photomask at room temperature. Electronics Letters 2003, 39, 9, 719–721. [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.; Soergel, E.; Buse, K. Influence of ultraviolet illumination on the poling characteristics of lithium niobate crystals. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2003, 83, 1824–1826. [CrossRef]

- Dierolf, V. and Sandmann, C. Direct-write method for domain inversion patterns in LiNbO3. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2004, 84, 3987-3989. [CrossRef]

- Wengler, M.C.; Fassbender, B.; Soergel, E. and Buse, K. Impact of ultraviolet light on coercive field, poling dynamics and poling quality of various lithium niobate crystals from different sources. J. Appl. Phys. 2004, 96, 2816–2820. [CrossRef]

- Sones, C.L.; Muir, A.C.; Ying, Y.J.; Mails, S.; Eason, R.W.; Jungk, T.; Hoffman, Á. and Soergel, E. Precision nanoscale domain engineering of lithium niobate via UV laser induced inhibition of poling. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2008, 92, 072905. [CrossRef]

- Fujimura, M. and Suhara, T. Formation of MgO:LiNbO domain-inverted gratings by voltage application under UV light irradiation at room temperature. Adv. Optoelectron. 2008, 2008, 421054. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.J.; Kong, Y.F.; Liu, H.D.; Hu, Q.; Liu, S.G.; Chen, S.L. and Xu, J.J. Light-induced domain reversal in doped lithium niobate crystals. J. Appl. Phys. 2009, 105, 043105. [CrossRef]

- Fujimura, M.; Kitado, E.; Inoue, T. and Suhara, T. MgO:LiNbO3 waveguide quasi-phase-matched second-harmonic generation devices fabricated by two-step voltage application under UV light. IEEE Photonics Tech. L. 2011, 23, 1313–1315. [CrossRef]

- Kitado, E.; Fujimura, M. and Suhara, T. Ultraviolet Laser Writing of Ferroelectric-Domain-Inverted Gratings for MgO:LiNbO3 Waveguide Quasi-Phase-Matching Devices. Appl. Phys. Express 2013, 6, 102204. [CrossRef]

- Boes, A.; Steigerwald, H.; Yudistira, D.; Sivan, V.; Wade, S.; Mailis, S.; Soergel, E. and Mitchell, A. Ultraviolet laser-induced poling inhibition produces bulk domains in MgO-doped lithium niobate crystals. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 105, 092904. [CrossRef]

- Fahy, S.; Merlin, R. Reversal of ferroelectric domains by ultrashort optical pulses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1994, 73, 1122. [CrossRef]

- Valdivia, C.E.; Sones, C.L.; Scott, J.G.; Mailis, S.; Eason, R.W.; Scrymgeour, D.A.; Gopalan, V.; Jungk, T. ; Soergel, E. and Clark, I. Nanoscale surface domain formation on the +z face of lithium niobate by pulsed ultraviolet laser illumination. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2005, 86, 022906. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.S.; Chen, X.F.; Chen, H.G.; and Deng, X.W. Formation of domain reversal by direct irradiation with femtosecond laser in lithium niobate. Chin. Opt. Lett. 2009, 7, 169–172.

- Lao, H.Y.; Zhu, H.S. and Chen, X.F. Threshold fluence for domain reversal directly induced by femtosecond laser in lithium niobate. Appl. Phys. A 2010, 101, 313–317. [CrossRef]

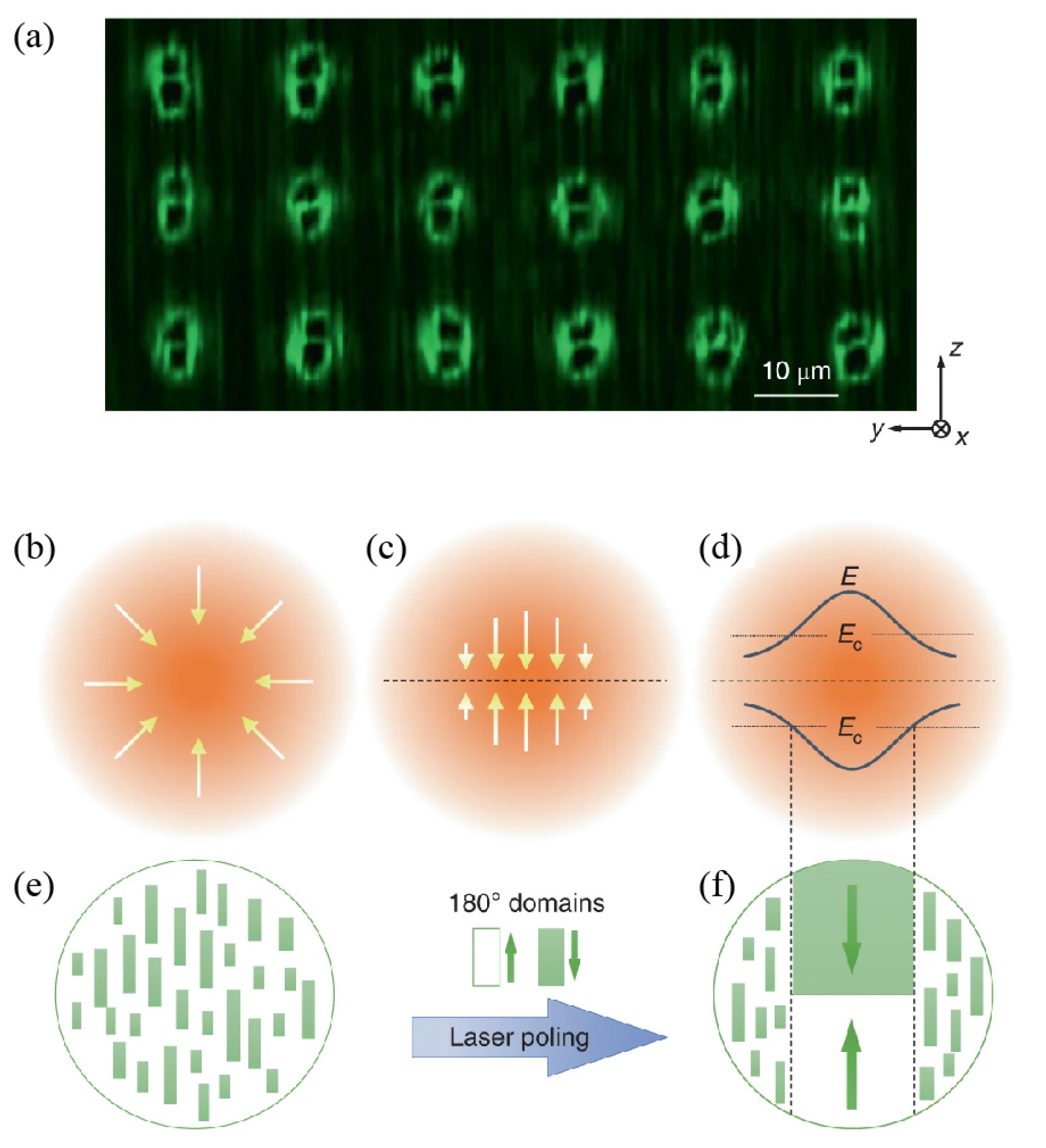

- Chen, X.; Karpinski, P.; Shvedov, V.; Koynov, K.; Wang, B.X.; Trull, J.; Cojocaru, C.; Krolikowski, W. and Sheng, Y. Ferroelectric domain engineering by focused infrared femtosecond pulses. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015, 107, 141102. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Karpinski, P.; Shvedov, V.; Boes, A.; Mitchell, A.; Krolikowski, W. and Sheng, Y. Quasi-phase matching via femtosecond laser-induced domain inversion in lithium niobate waveguides. Opt. Lett. 2016, 41, 11, 2410. [CrossRef]

- Imbrock, J.; Hanafi, H.; Ayoub, M. and Denz, C. Local domain inversion in MgO-doped lithium niobate by pyroelectric field-assisted femtosecond laser lithography. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2018, 113, 252901. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wang, T.; Chen, P.; Zhou, C.; Ma, J.; Wei, D.; Wang, H.; Niu, B.; Fang, X.; Wu, D.; Zhu, S.; Gu, M.; Xiao, M. and Zhang, Y. Femtosecond laser writing of lithium niobate ferroelectric nanodomains. Nature 2022, 609, 469-501. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cao, Q.; Wang, R.-N.; Cao, X. and Liu, S. Manipulation of ferroelectric domain inversion and growth by optically induced 3D thermoelectric field in lithium niobate. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2022, 121, 181111. [CrossRef]

- Maekawa, S. et al. Appendices D. Thermoelectric Effects. In Physics of Transition Metal Oxides; eds Cardona, M. et al.; Springer Berlin, Heidelberg, 2004; pp. 323–331.

- Ashcroft, N.W. and Mermin, N.D.; In Solid State Physics; ed. Crane, D. G.; Harcourt College, 1976; pp. 253–258.

- Kosorotov, V.F.; Kremenchugskij, L.S.; Levash, L.V. and Shchedrina, L.V. Tertiary pyroelectric effect in lithium niobate and lithium tantalate crystals. Ferroelectrics, 1986, 70, 27–37. [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, R.; Kar, S.; Bartwal, K.S.; Shula, V.; Sen, P.; Sen, P.K.; Wadhawan, V.K. Studies on nonlinear optical properties of ferroelectric MgO-LiNbO3 single crystals. Ferroelectrics 2005, 323, 165–169. [CrossRef]

- Reddy, J.N.B.; Elizabeth, S.; Bhat, H.L.; Venkatram, N. and Rao, D.N. Influence of non-stoichiometric defects on nonlinear absorption and refraction in Nd:Zn co-doped lithium niobate. Opt. Mater. 2009, 31, 1022–1026. [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Switkowski, K.; Chen, X.; Liu, S.; Koynov, K.; Yu, H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Sheng, Y. and Krolikowski W. Three-dimensional nonlinear photonic crystal in ferroelectric barium calcium titanate. Nature Photon 2018, 12, 591–595. [CrossRef]

- Saltiel, S.M.; Neshev, D.N.; Krolikowski, W.; Voloch-Bloch, N.; Arie, A.; Bang, O. and Kivshar, Y.S. Nonlinear diffraction from a virtual beam. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 104, 083902. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Jesacher, A.; Booth, M.; Wilson, T.; Ródenas, A.; Jaque, D. and Gu, M. Axial birefringence induced focus splitting in lithium niobate. Opt. Express 2009, 17, 17970–17975. [CrossRef]

- Karpinski, P.; Shvedov, V.; Krolikowski, W. and Hnatovsky, C. Laser-writing inside uniaxially birefringent crystals: fine morphology of ultrashort pulseinduced changes in lithium niobate. Opt. Express 2016, 24, 7, 7456-7476. [CrossRef]

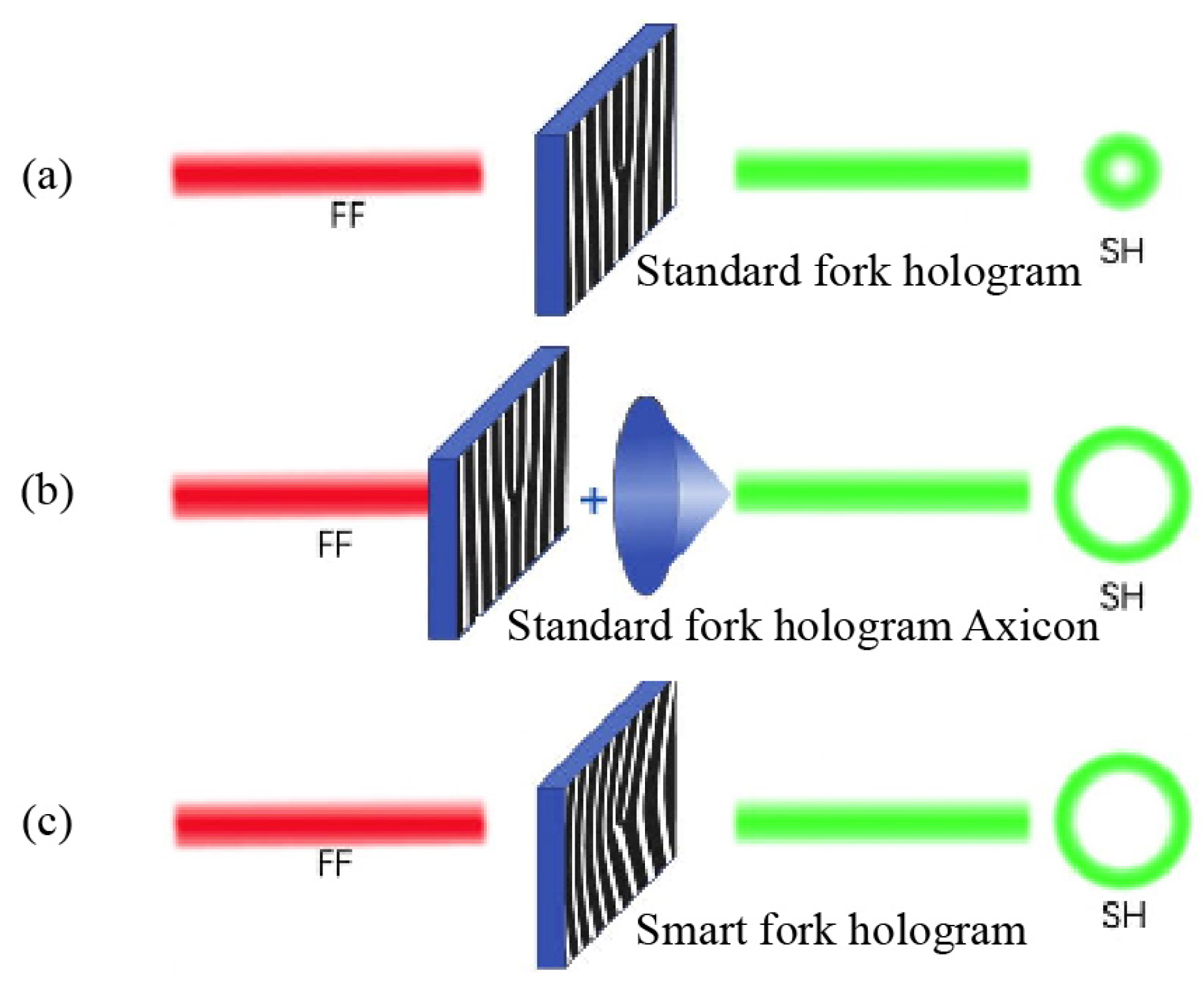

- Liu, Sh.; Switkowski, K.; Xu, C.; Tian, J.; Wang, B.; Lu, P.; Krolikowski, W. and Sheng, Y. Nonlinear wavefront shaping with optically induced three-dimensional nonlinear photonic crystals. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 3208. [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Liu, S.; Mazur, L.M.; Wang, B.; Lu, P.; Krolikowski, W. and Sheng, Y. Smart optically induced nonlinear photonic crystals for frequency conversion and control. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2020, 116, 051104. [CrossRef]

- Ostrovsky, A.S.; Rickenstorff-Parrao, C. and Arrizŏn, V. Generation of the perfect optical vortex using a liquid-crystal spatial light modulator. Opt. Lett. 2013, 38, 534–536. [CrossRef]

- Topuzoski, S. Generation of optical vortices with curved fork-shaped holograms. Opt Quantum Electron 2016, 48, 138. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Mazur, L.M.; Krolikowski, W. and Sheng, Y. Nonlinear volume holography in 3D nonlinear photonic crystals. Laser Photonics Rev 2020, 14, 2000224. [CrossRef]

- Mazur, L.M.; Liu, S.; Chen, X.; Krolikowski, W. and Sheng,Y. Localized ferroelectric domains via laser poling in monodomain calcium barium niobate crystal. Laser Photonics Rev. 2021, 15, 2100088. [CrossRef]

- Imbrock, J.; Szalek, D.; Laubrock, S.; Hanafi, H. and Denz, C. Thermally assisted fabrication of nonlinear photonic structures in lithium niobate with femtosecond laser pulses. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 22, 39340-39352. [CrossRef]

- Bhalla, A.S.; Newnham, R.E. Pyroelectric properties and phase transition in TRIS (dimethylammonium) nonabromodiantimonate uppercaseiii . Solid State Commun 1988, 67, 1079-1083. [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Fang, B.; Xu, H.; Luo, H. Crystal orientation dependence of dielectric and piezoelectric properties of tetragonal Pb(Mg1/3Nb2/3)O3–38%PbTiO3 single crystalMater. Res. Bull. 2002, 37, 2135–2143. [CrossRef]

- Gopalan, V.; Mitchell, T.E.; Furukawa, Y. and Kitamura, K. The role of nonstoichiometry in 180∘ domain switching of LiNbO3 crystals. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1998, 72, 1981–1983. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Gopalana, V. and Gruverman, A. Coercive fields in ferroelectrics: A case study in lithium niobate and lithium tantalate. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2002, 80, 2740-2742. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, D.; Liu, S.; Mazur, L.M.; Liu, X.; Wei, X.; Xu, Z.; Wang, I.; Sheng, Y.; Wei, Z. and Krolikowski, W. Optical induction and erasure of ferroelectric domains in tetragonal PMN-38PT crystals. Adv Optical Mater 2021, 10, 2102115. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Mazur, L.M.; Liu, D.; Liu, S.; Liu, X.; Xu, Zh.; Wei, X.; Wang, J.; Sheng, Y.; Wei, Z. and Krolikowski, W. Quasi-phase matched second harmonic generation in a PMN-38PT crystal. Opt. Lett. 2022, 47, 8, 2056–2059. [CrossRef]

| -erasing | References | Nonlinear Crystal | Repeat frequency | Bandwidth | Wavelength | Pulse energy | Scan speed | N.A. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ref. [72] | LiNbO | 100 kHz | 170 fs | 800 nm | 650 nJ | 1 mm/s | 0.5 | |

| Ref. [73] | LiNbO | 1 kHz | 120 fs | 800 nm | 60-72 nJ | 80 m/s | 0.8 | |

| Ref. [75] | LiNbO | 1 kHz | 104 fs | 800 nm | 100-200 nJ | 100-55 m/s | 0.8 | |

| Ref. [77] | MgO-doped LiNbO | 1 kHz | 500 fs | 1030 nm | 900 nJ | 280 m/s | 0.5 | |

| Ref. [79] | LiNbO | 200 kHz | 350 fs | 1040 nm | 16/20 nJ | 1mm/s | 0.3 | |

| Quartz | 8/12 nJ | |||||||

| -poling | References | Nonlinear Crystal | Repeat frequency | Bandwidth | Wavelength | Pulse energy | Scan speed | N.A. |

| Ref. [95] | LiNbO | 76 MHz | 180 fs | 800 nm | 0-5 nJ | 10 m/s | 0.65 | |

| Ref. [105] | BCT | 76 MHz | 180 fs | 800 nm | ~6 nJ | 10 m/s | 0.65 | |

| Ref. [109] | CBN | 76 MHz | 180 fs | 800 nm | 3.6-6.6 nJ | 10 m/s | 0.65 | |

| Ref. [120] | PMN-38PT | 80 MHz | 180 fs | 800 nm | 0-5 nJ | 0.4 | ||

| Seeds | Ref. [97] | MgO-doped LiNbO | 1 kHz | 100 fs | 800 nm | 50-500 nJ | 0.8 | |

| LM | Ref. [99] | MgO-doped LiNbO | 1000 kHz | 170 fs | 1026 nm | 150 nJ | 0.42 | |

| LI | 500 kHz | 300-900 nJ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).