1. Introduction

Since the discovery by Iijima in 1991, carbon nanotubes (CNT) have been one of the most interesting and promising materials for use in various fields of application [

1]. Owing to their unique mechanical, optical, and electronic properties, CNTs are of scientific and practical interest for materials science [

2,

3,

4,

5]. The main advantages of CNTs are their high rigidity, thermal and electrical conductivity, low density, and high aspect ratio.

One of the possible applications of CNTs is their use as fillers to improve the strength properties of polymeric materials. The choice of polymer and filler is primarily determined by their compatibility. In the case of incompatibility, the resulting composite possesses reduced mechanical properties. A high level of interfacial adhesion makes it possible to distribute the load uniformly with a minimum value of stress concentration and obtain materials with high strength characteristics. Also, a decisive importance is the uniform dispersion of carbon nanotubes in the polymer matrix.

In the development of polymer composite materials, theoretical research is essential to predict the parameters for the use of CNTs. Experimental [

6,

7,

8,

9] and theoretical [

10,

11,

12,

13] studies showed that even a small percentage of CNTs in a polymer matrix changes its mechanical properties, such as stiffness and strength. For example, A.P. Sokolov et

al. reported that adding as small as 1% single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNT) to polypropylene results in a 3-fold increase in Young's modulus [

6]. They also noted a significant decrease in the slope of modulus vs. SWCNT concentration. L. Banks-Sills et

al. conducted a series of experimental and computerized tests to determine Young's modulus and Poisson's ratio for poly (methyl methacrylate) with CNTs. Their experiments showed that an increase in the concentration of CNTs in a polymer leads to a decrease and then to an increase in Young's modulus and Poisson's ratio [

9]. This behavior can be explained not only by the geometry and orientation of CNTs, but also by the presence of polymer–CNT interfacial interaction. Computer simulation studies also showed that the relationship between interfacial bonding and load transfer between matrix and fillers cannot be neglected and makes a great influence on the mechanical properties of nanocomposites [

12,

14,

15].

One of the key parameters of a composite is its ability to resist various deformations. Physical quantities that characterize the ability of a material to deform elastically when a force is applied are called elastic moduli. The measurement of stress and strain changes in a composite, including different directions of force, can be done in various ways, so there are several types of elastic moduli.

The matrix of elastic constants has the form in general:

where tensor components give the relationship between the stresses and the resulting deformations for anisotropic system in different directions.

Young's modulus, shear modulus, bulk modulus and Poisson's ratio are determined by the coefficients of the matrix

Cij and the coefficients of the inverse matrix

Sij= Cij-1, known as the elastic compliance matrix. It should be taken into account that the experimental values of the elastic moduli of polymers are affected by the methods of sample preparation, the presence of impurities, and equipment. During the modeling some errors in the values are acceptable since “ideal” composite samples are created, where the interaction of components is described by forcefields. In addition, the general macroscopic rule of mixtures cannot be directly applied to composites with strong interfacial interactions [

13]. Also, SWNT dispersion is a critical condition that allows one to control the mechanical properties of the composite [

33]. In Ref. [

10] the authors present a modeling approach for predicting the effective mechanical properties of polymer nanocomposites modified with SWNT. Their simulation results with the proposed approach showed good agreement with experimental data for epoxy-SWNT composites. In Ref. [

11], the mechanical behavior of CNT/PMMA composite materials subjected to tensile loading is studied using MD simulation. The results of their simulations showed that the Young's modulus of the PMMA composite reinforced with an infinitely long CNT increases significantly compared to pure PMMA. In addition, they noted that the strength of the CNT/polymer interfacial bond increases with increasing elongation of the CNT fibers and leads to high strength of the composite. In Ref. [

12], the results of MD simulation showed that the stronger the interfacial interaction between the CNT and the polymer matrix, the lower the Young's modulus as a result of the compressibility of the interfacial region; It was also concluded that the presence of an optimal interfacial interaction between a polymer and CNTs is one of the key factors in improving the mechanical properties of nanocomposites.

One of the key characteristics of a polymer composite material is the glass transition temperature (T

g), at which the polymer passes from a liquid or highly elastic state to a glassy one. This parameter allows to determine the application area of the composite material. Experiments show that the introduction of nanofillers affects the crystalline behavior and structure of the polypropylene matrix; in particular, the mechanisms of heterogeneous nucleation are accelerated [

16]. It was also found that the crystallinity of the polymer increases with the addition of CNTs [

17,

18]. For example, T. Sterzynski et

al. reported that the glass transition temperature of a PVC composite increases with increasing the multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNT) content using DSC and DMTA methods [

19]. The simulation results in Ref. [

44] showed that the addition of CNTs to epoxy resin leads to an increase in the glass transition temperature. By means of MD simulations Wei at

al. [

45] also showed that the addition of CNTs to a polymer leads to an increase in the glass transition temperature. In Ref. [

46], the authors also concluded by means of simulations that the addition of CNTs to polyethylene leads to an increase in T

g.

To sum up, many experimental and calculated works have been published to date considering composites of polymers and CNTs. And most works on computer simulation describe experimental work quite well. However, their implementation is rather complicated. That is related first of all with a significant computational resource required for that. Besides, there is no unified methodology for a polymer-SWNT composites description. Consequently, the purpose of this work is to present a molecular dynamics procedure for a polymer-SWNT composite mechanical properties as well as glass transition temperature evaluation and to predict the behavior of the elastic moduli in a polymer-SWNT composites using computer simulation in a wide range of SWNT concentrations. Composites with low (2-10%) and high (19-70%) SWCNTs are considered within the present research. The mass fraction of nanotubes in the composite was calculated using the following formula: where mcnt is the mass of the nanotube, mpol is the mass of the polymer chain. Also, in the paper the comparison with experimental and theoretical data is performed where available. Overall, in the research the influence of the concentration, diameter, and type of SWCNTs on the mechanical properties of polypropylene (PP), poly (ethyl methacrylate) (PEMA), and polystyrene (PS) is investigated.

2. Simulation methodology

In this work, we used the method of classical molecular dynamics, which is based on the laws of classical mechanics, statistical physics, and thermodynamics and takes into account the features of atomistic models and the chemical structure of the polymer chain. To determine these physical characteristics, in the present research the computer atomistic simulator MedeA® Software Environment was used [

20]. This software includes the LAMMPS code developed by S.J. Plimpton, which explores the method of classical molecular dynamics [

24]. The method considers the features of atomistic models and the chemical structure of the polymer composite. and the evolution of a system of interacting atoms or particles is tracked by integrating their equations of motion. However, it cannot be applicable when quantum effects must be taken into account and at times shorter than the relaxation time of physical quantities. To describe the interactions of atoms, functions called forcefields are used. In this work, a polymer matched forcefield (PCFF+) was chosen [

23]. This forcefield is applicable to polymers, organic and inorganic materials, and can also be used to calculate mechanical properties.

From a computational point of view, it is difficult to calculate the strength of large polymer systems, therefore, in this work, a representative elementary volume (RVE) of a polymer composite was simulated with periodic boundary conditions. According to the type of molecular structure, the polymers in this study were atactic. Nanotubes were in an arbitrary position for 30 simulated structures. The obtained values of the elastic moduli were all averaged over generated configurations.

It is also hard to calculate the strength of polymer composite systems for large deformations, since the probability of irreversible / plastic deformations increases. In addition, small deformation can increase the uncertainty in the calculations due to numerical errors. That is why the present study focuses only on the calculation of elastic moduli at low strain. Mechanical properties were calculated using a strain of 0.001 (0.1%). Thus, in this work, the general trends in the mechanical properties of composites versus CNTs composition are presented.

First, a polymer unit was created, then a polymer chain and a nanotube were built, from which a representative elementary volume (RVE) of a polymer composite was created at a temperature of 298.2 K and a polymer density of 0.9 g/cm3. For each study, 30 configurations were randomly constructed, the obtained values were all averaged.

The simulated cells were all equilibrated and deformed. The equilibration was carried out using NVT and NPT ensembles, which perform time integration, updating the coordinates and velocities at each time step of the simulated system. The Ewald summation method was used to calculate long-range interactions, and the cutoff radius was 9.5 Å [

25]. Temperature and pressure were controlled using a thermostat and barostat proposed by Berendsen [

26]. After equilibration, the energy was minimized by the conjugate gradient method [

21,

22]. The value of deformation used for structural analysis was 0.1%.

The calculations were performed in several stages. At the first stage, variables for the initial and final temperatures and pressures were set, and the integration step was also set. At the second stage, optimization of atomic positions was carried out with the following order: relaxation in the NVT ensemble at a temperature of 298.2 K for 5 ps; in the NVT ensemble, the cell temperature varied from 500 K to 298 K within 5 ps with a step of 1 fs; Then, in the NPT ensemble, the pressure was changed from 1000 atm to 1 atm for 50 ps with a step of 1 fs; In the NVT ensemble, the cell temperature varied from 500 K to 298 K within 50 ps with a step of 1 fs; in the NPT ensemble, relaxation was carried out at a temperature of 298.15 K for 100 ps. At the third stage, the resulting cell density was set. At the fourth stage, the cell was relaxed at a temperature of 298 K for 10 ps with an integrating step of 1 fs. At the fifth stage, the deformation of the polymer structure was set. With small deformations, about 90% mechanically stable structures can be obtained (with the stiffness matrix being positive and non-negative eigenvalues) as based on the mechanical properties calculation results. Thus, a matrix of elastic constants was calculated for chosen configurations, and the elastic moduli and Poisson's ratio were determined. The elastic moduli were calculated according to Voigt and Reuss, which represent the averaging of the elasticity matrix (

Cij) and compliance matrix (

Sij) and correspond to the extreme upper and lower bounds [

27,

28]. To determine the final value of the elastic moduli, the Hill approximation was used, which is the arithmetic mean of the boundaries according to Voigt and Reuss [

29]. According to the type of molecular structure, the polymers in this study were all atactic, i.e., stereoisomeric configurations at all centers of the main chain were arranged randomly. The nanotubes in the RVE were arranged randomly as shown in

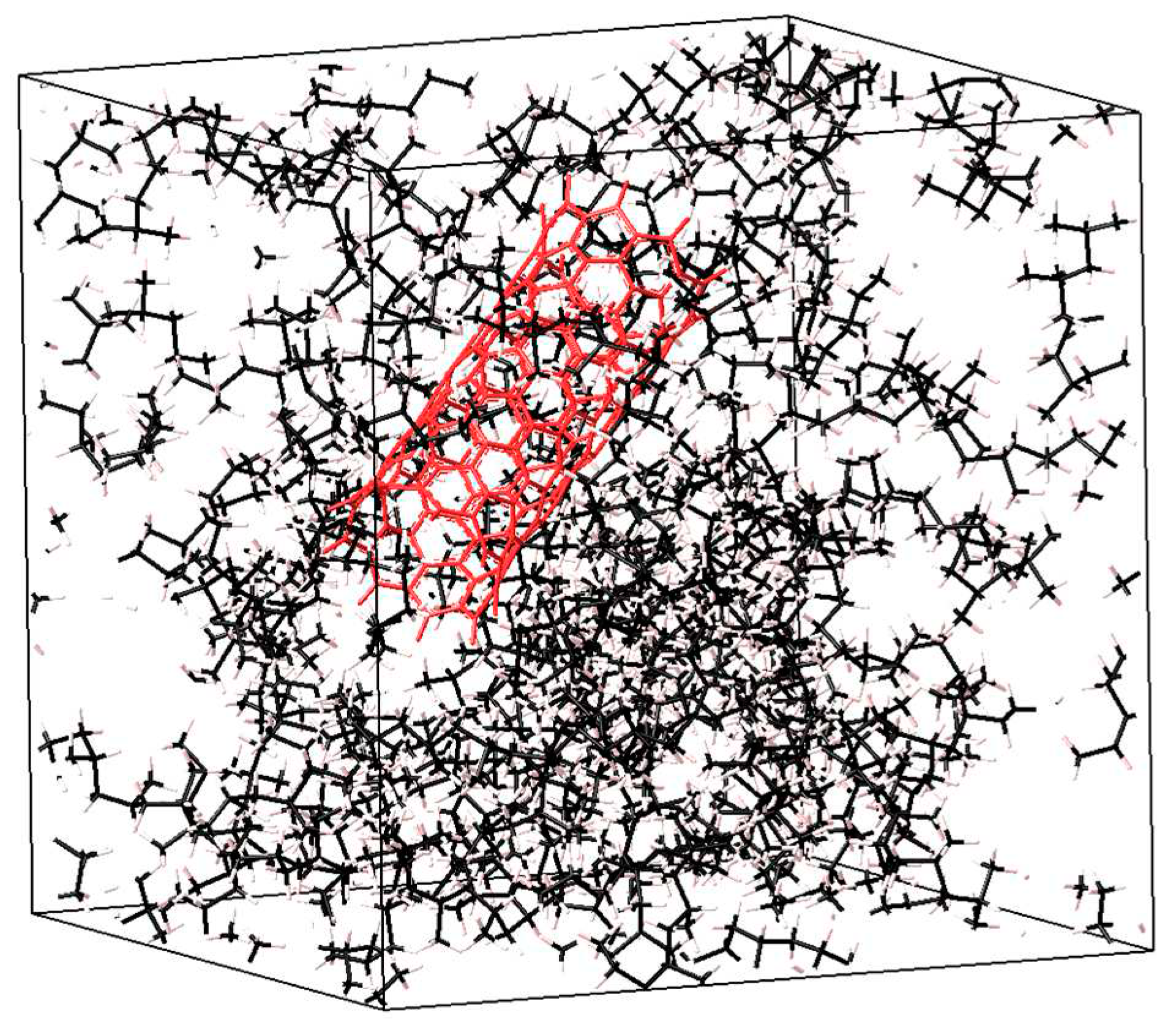

Figure 1. Besides, each modulus of elasticity was averaged over the values of 30 cells.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Effect of nanotube concentration

3.1.1. Determination of elastic moduli for polymer-SWCNT

At the first stage, the polypropylene (PP) with the addition of zig-zag CNTs was chosen for the impact of SWCNTs concentration onto the mechanical properties’ investigation. PP is thermoplastic, capable of reversibly transforming into a highly elastic or viscous state when heated. The molecular weight of considered PP for different SWCNT concentrations is given in

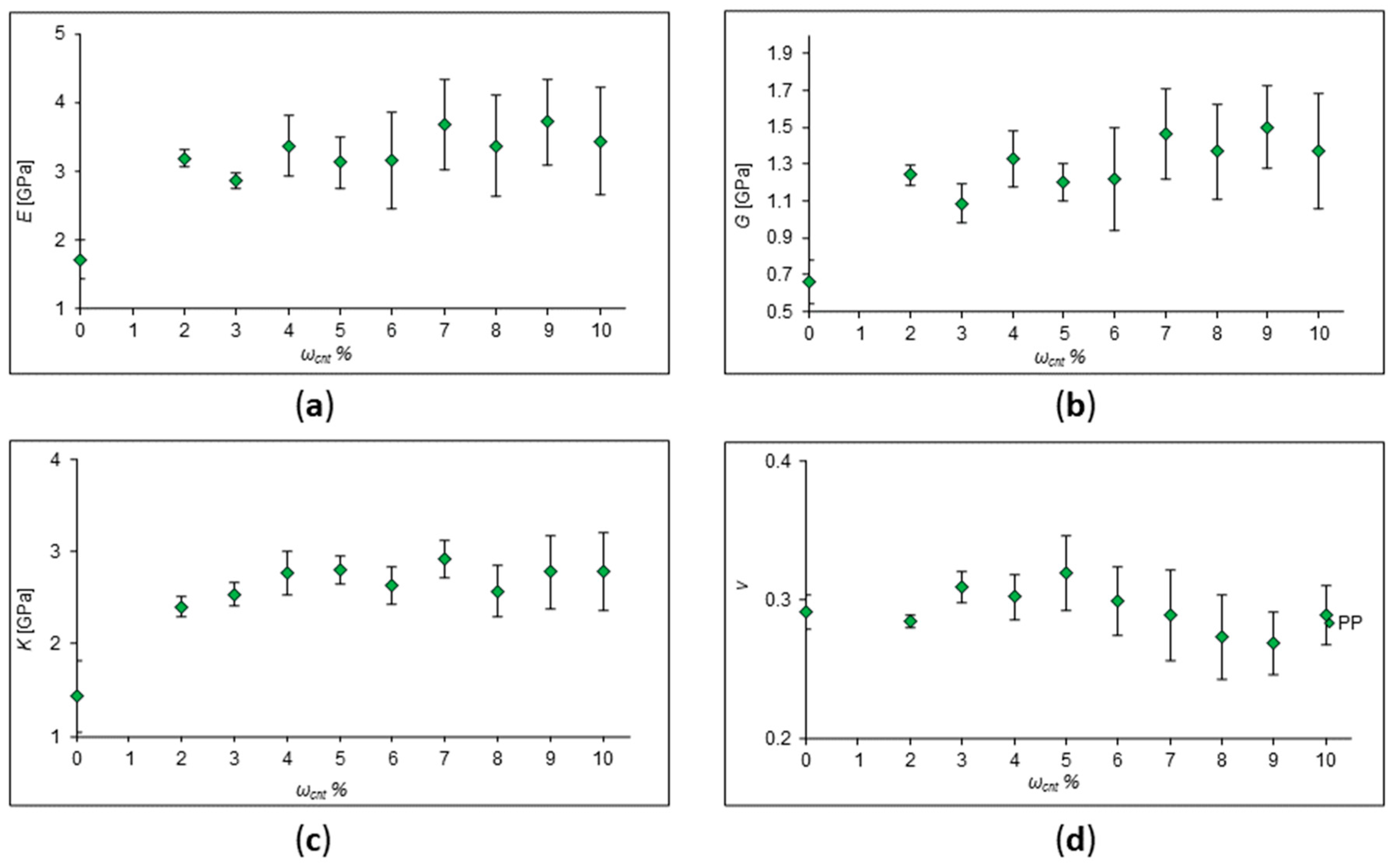

Table 1 along with the number of monomer units. The elastic moduli of polypropylene (PP) with the addition of zig-zag CNTs, chirality indices (9;0) and length 18 Å were calculated and plotted in

Figure 2, where values of Young's modulus (E), shear modulus (G), bulk modulus (K) and Poisson's ratio (ν) are presented. It is well seen from the plots that a possible nonlinear behavior of the polymer upon addition of CNTs takes place.

Let's discuss the obtained behavior. As a result of these calculations, we see that the ability of the material to resist deformation increases. However, this happens in a non-linear manner. The same behavior was observed in many experiments [

6,

9,

30,

31,

32]. This can be explained by the fact that there is an interfacial interaction between the nanotube and the polymer. The arrangement of nanotubes also plays an important role: the more ordered it is, the more rigid the composite in the direction of most nanotubes arrangement. In Ref. [

30], the results obtained from differential scanning calorimetry curves showed that the addition of SWCNTs to isotactic polypropylene in small amounts (less than 1 wt.%) leads to an increase in Young's modulus and tensile strength. At a concentration of 1%, both stiffness and strength decreased significantly. Also, the results of tensile test shave shown that the inclusion of nanotubes in an amount of less than 1% by weight increases the tensile strength due to the strong interfacial interaction relative to the un-reinforced polymer. In Ref. [

32], authors reported that CNT significantly affected the mechanical properties of PP/CNT, in particular, the modulus of elasticity and strain at failure. They claimed that the elastic modulus slightly increases at a low CNT content (1–5%). A further increase in the content of CNTs leads to a decrease in the elastic modulus, but it was still higher than that of pure PP. However, elongation at break sharply decreases with increasing CNT content in agreement with Ref. [

32] and other works. This is obvious since the nanotubes make the polymer more rigid and inelastic. S.C. Tjong et

al. studied polypropylene nanocomposites reinforced with 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, and 1.0 wt% MWCNTs [

18]. In their work, DMA analysis showed that the elastic modulus and thermal bending temperature of a PP/MWCNT nanocomposite are improved by about 33% by adding only 0.3–0.5 wt% of MWCNTs.

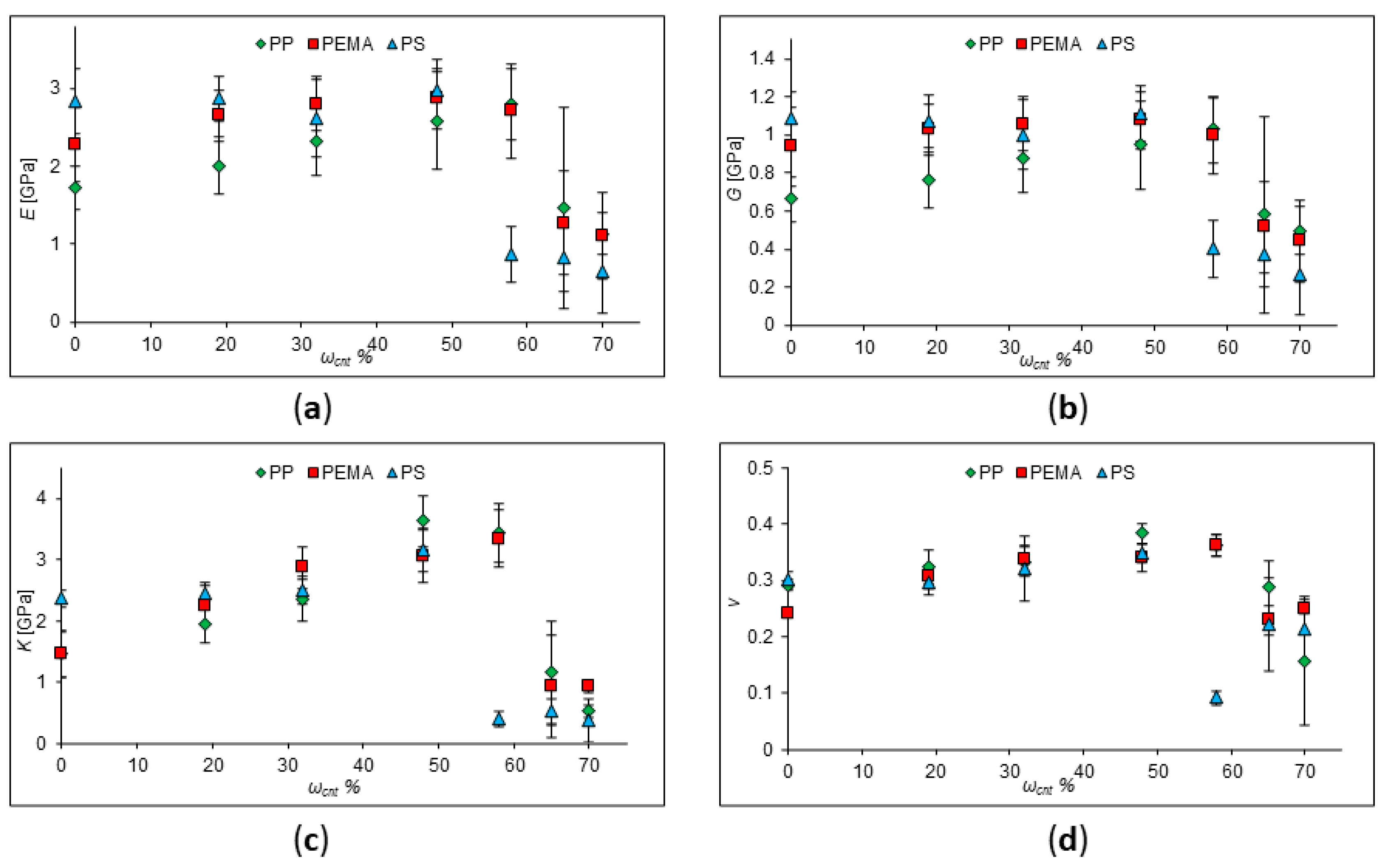

At the next stage, the change in the elastic moduli was determined at high (more than 19%) SWCNT concentrations. The elastic moduli of polypropylene (PP), poly (ethyl methacrylate) (PEMA) and polystyrene (PS) with the addition of CNTs, chirality indices (9;0) and length 18 Å were investigated (

Figure 3). Parameters of SWCNTs and polymer chains are given in

Table 2. For these cells, the values of Young's modulus, shear modulus, bulk modulus and Poisson's ratio were obtained. According to the data obtained for polypropylene, it can be seen that in the composite the values of the Young's modulus, shear modulus and bulk modulus decrease, but they are greater than for unfilled polymer as long as their concentration is less than 60%. The values of all elastic moduli drop sharply with a further increase in the SWCNT concentration. This may be due to the fact that an insufficient amount of polymer cannot hold the SWCNT together by van der Waals forces, and the composite is destroyed at the same values of the mechanical stress.

To sum up, we have shown that at low concentrations (less than 10 %), nanotubes can increase the elastic moduli of the polymer. However, this phenomenon will be maintained only within certain limits. Thus, for SWCNT (with a high modulus of elasticity and low strain to rupture), direct proportionality is not maintained at high degrees of reinforcement, since the matrix (binder) drags the fibers along during deformation, which leads to the destruction of the composite. At high degrees of reinforcement, the lack of a binder to fill the interfiber space above the critical value leads to a violation of the solidity of the composite and, accordingly, the appearance of uneven stresses in it; therefore, destruction occurs at lower values of mechanical stresses than for monolithic samples.

3.1.2. Determination of glass transition temperature for polypropylene

At the next stage, for these configurations the glass transition temperatures were calculated. The results are presented in

Figure 4 where the dependence of the glass transition temperature of the composite on the mass fraction of SWCNTs is shown. It was found that the incorporation of nanotubes leads to an increase in the glass transition temperature (T

g) of the composite, since the mobility of the polymer chain decreases, and the amorphous polymer becomes more rigid.

Obtained values show the dependence of the glass transition temperature of the composite on the mass fraction of SWCNTs. When CNTs are added to the composite, the ordered arrangement of some individual parts increases, which leads to an increase in the glass transition temperature. So, that agrees to the conclusions made by S.C. Tjong et

al.

[18]. They found that adding even a small amount of MWCNTs to PP results in a shift in the glass transition temperature towards higher temperatures. However, the addition of CNTs can also lead to a decrease in the glass transition temperature. So, in an article by Brian P. Grady et

al., composites based on polycarbonate with MWCNTs demonstrated a glass transition temperature lower than that of pure polycarbonate

[35]. They reported that MWCNT reduced the amount of polymeric material involved in the glass transition of composites, which affected T

g.

Thus, it has been demonstrated that the introduction of fillers affects the crystalline behavior and structure of the polypropylene matrix. The microstructure and distribution of CNTs in the polymer matrix are very important for obtaining a material with high strength characteristics. However, due to the weak interaction at the CNT-polymer interface in composites as well as defects in the structure, a decrease in the mechanical properties and thermal stability of the composite are possible, as a result of this the monolithicity of the composite is violated.

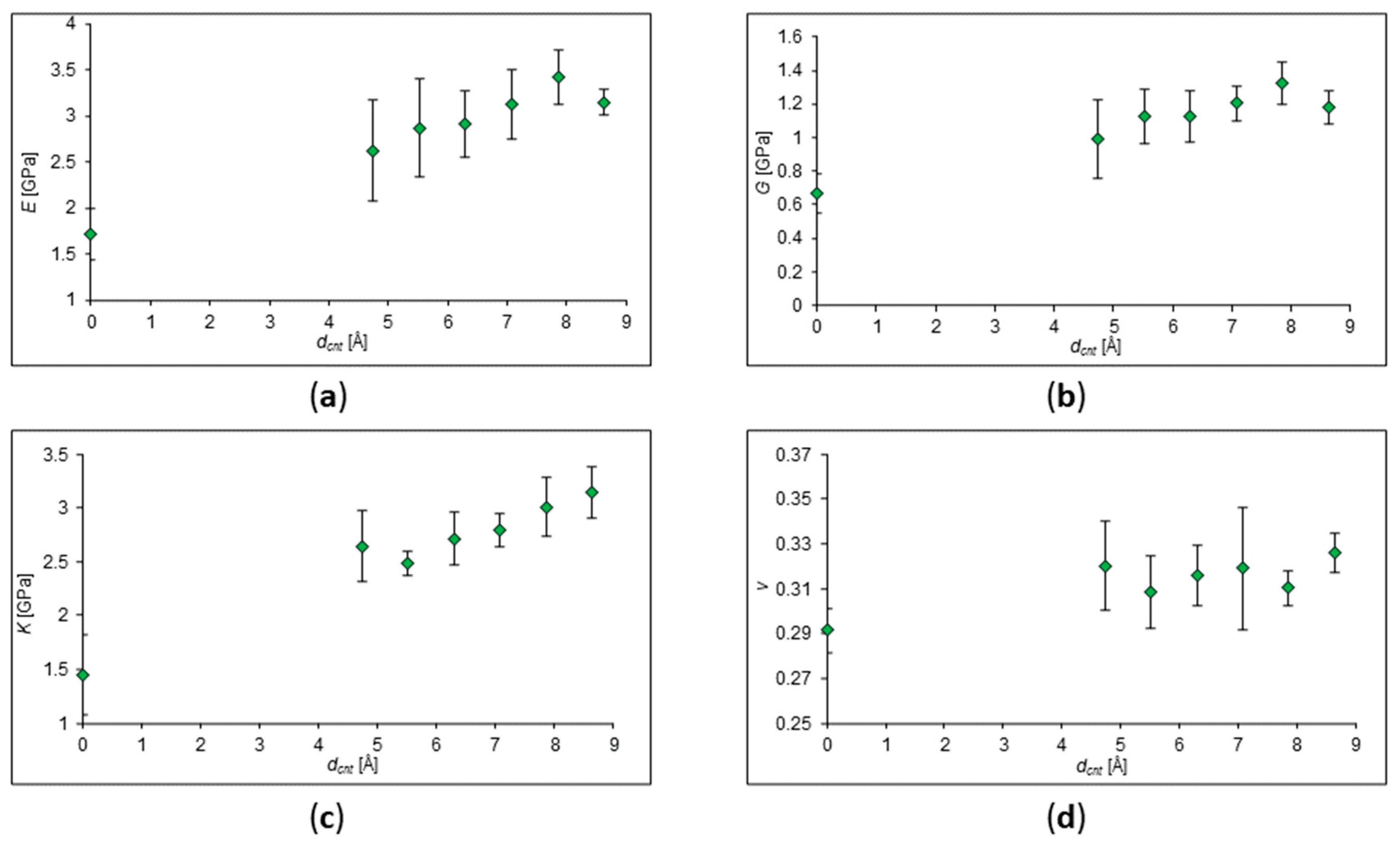

3.2. Effect of nanotube size

In the present chapter the effect of size of the filler on the strength characteristics of the composite were investigated. To maintain plasticity and strength, the filler must be “shrouded” in a polymer matrix. Parameters of SWCNTs and polymer chains are given in

Table 3. The dependences of the elastic moduli of polypropylene with the addition of zig-zag CNTs were obtained and demonstrated in

Figure 5. The concentration of CNTs in polypropylene was the same everywhere and equaled about 5%. It was obtained that with an increase in the radius of nanotubes, the values of the elastic moduli can also increase.

It can be seen from the obtained values that an increase in the SWCNT diameter in polypropylene leads to an increase in Young's modulus, bulk modulus, and shear modulus. That agrees with conclusion made by Tran Huu Nam et

al. for a CNT/epoxy composite: it is better to use smaller diameter aligned CNTs to achieve high mechanical properties

[37]. Besides, Hegde et

al. noticed a linear increase in Young's modulus with CNT diameter in poly (ether imide) [

38]. Moreover, in the article by Y. Zhu et

al., it was demonstrated that structural changes in the MWCNT/bismaleimide composite significantly affected the phonon and electron transport in the composite structure, but an increase in the length and diameter of CNTs did not lead to a noticeable change in the mechanical properties of the composites

[36]. However, a change in the CNT size can also lead to a deterioration in the strength characteristics of the composite

[34].

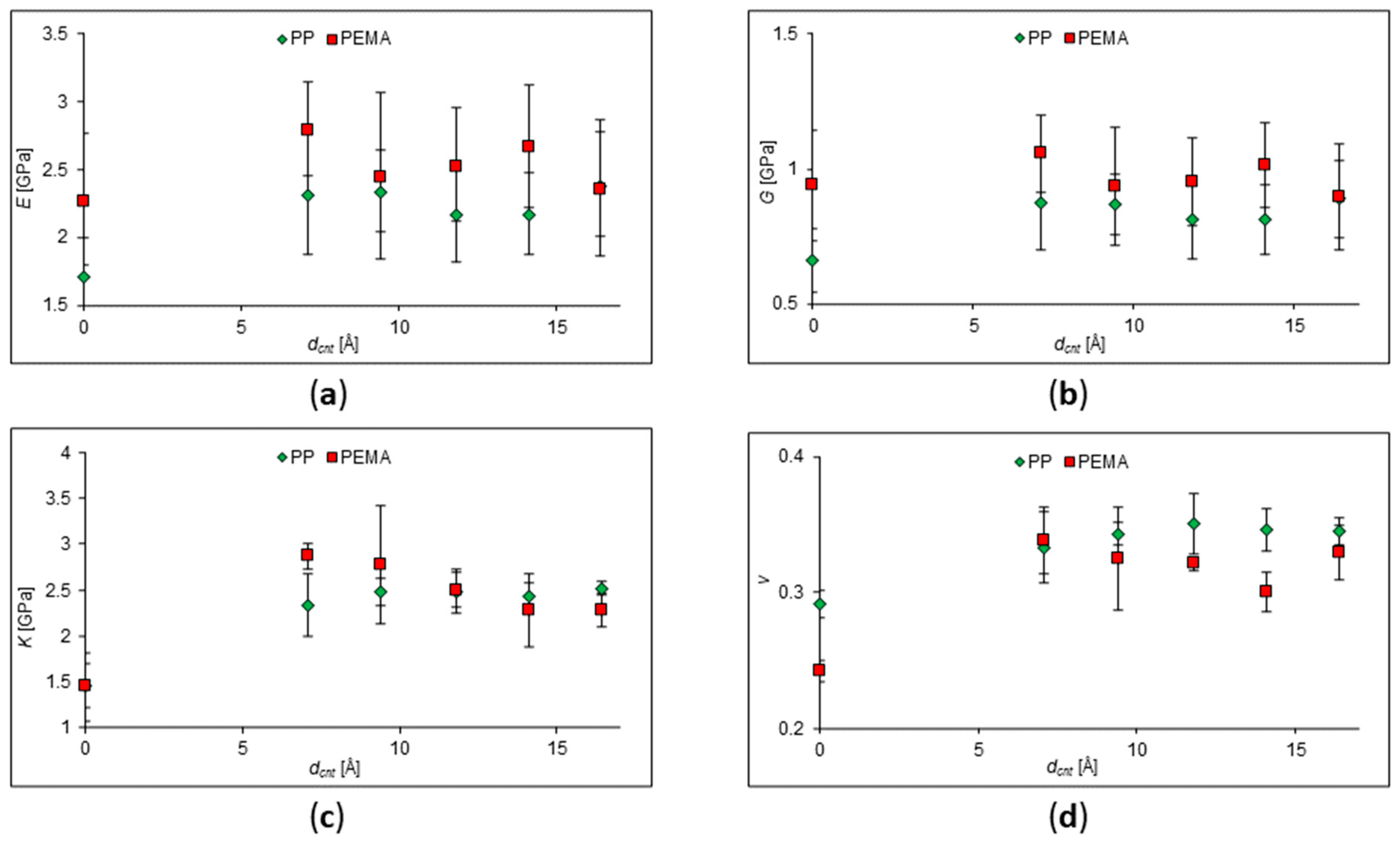

The dependences of the elastic moduli of polypropylene and poly (ethyl methacrylate) with the addition of zig-zag CNTs were obtained and presented in

Figure 6. The SWCNT concentration in this study is 30%. The parameters of SWCNTs and polymer chains are given in

Table 4. The obtained values indicate that the elastic moduli of the composites depend insignificantly on the diameter at high concentrations of carbon nanotubes. It can also be assumed that there is a critical value of the CNT diameter, after which the strength characteristics of the composite would decrease.

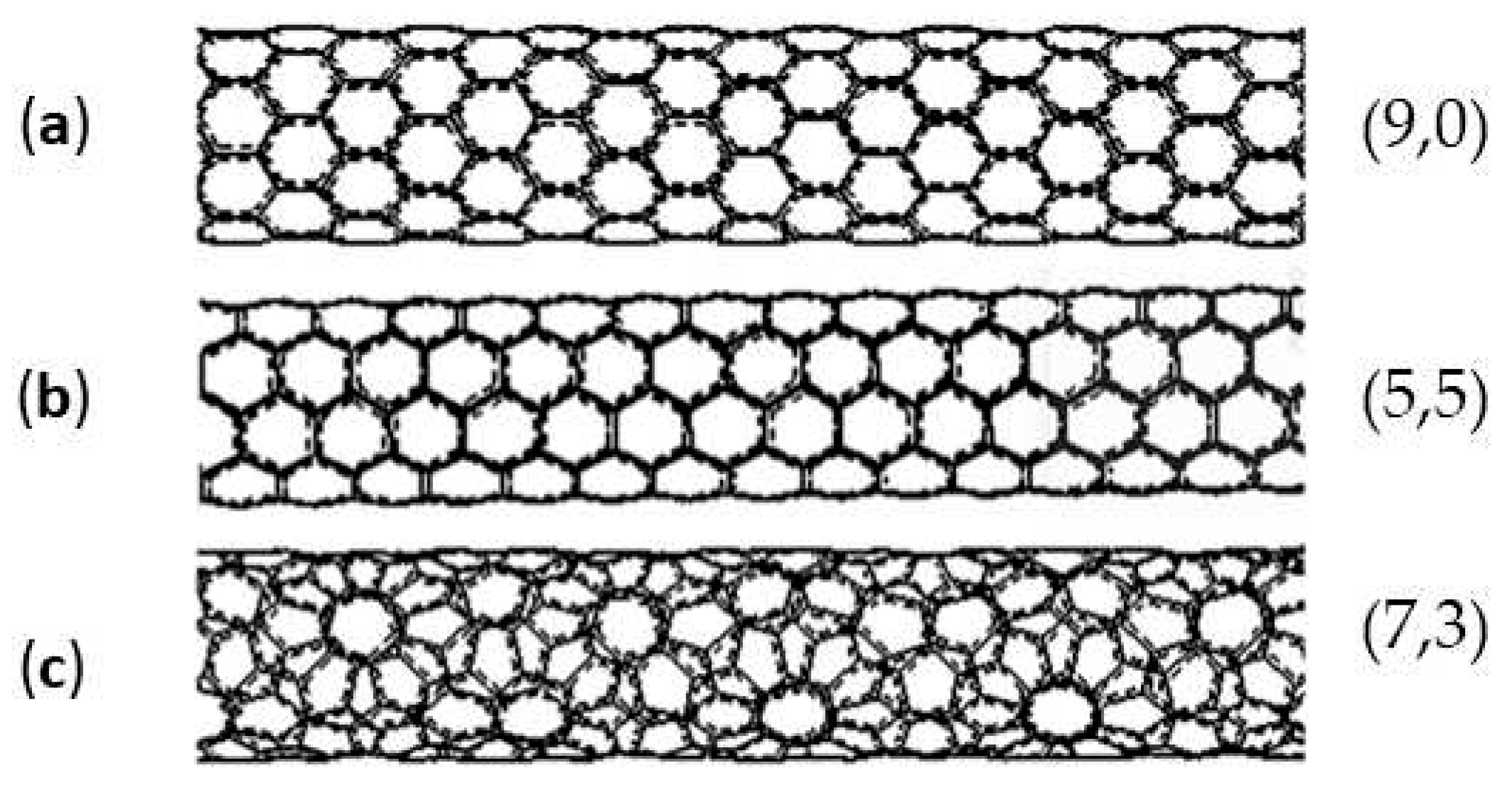

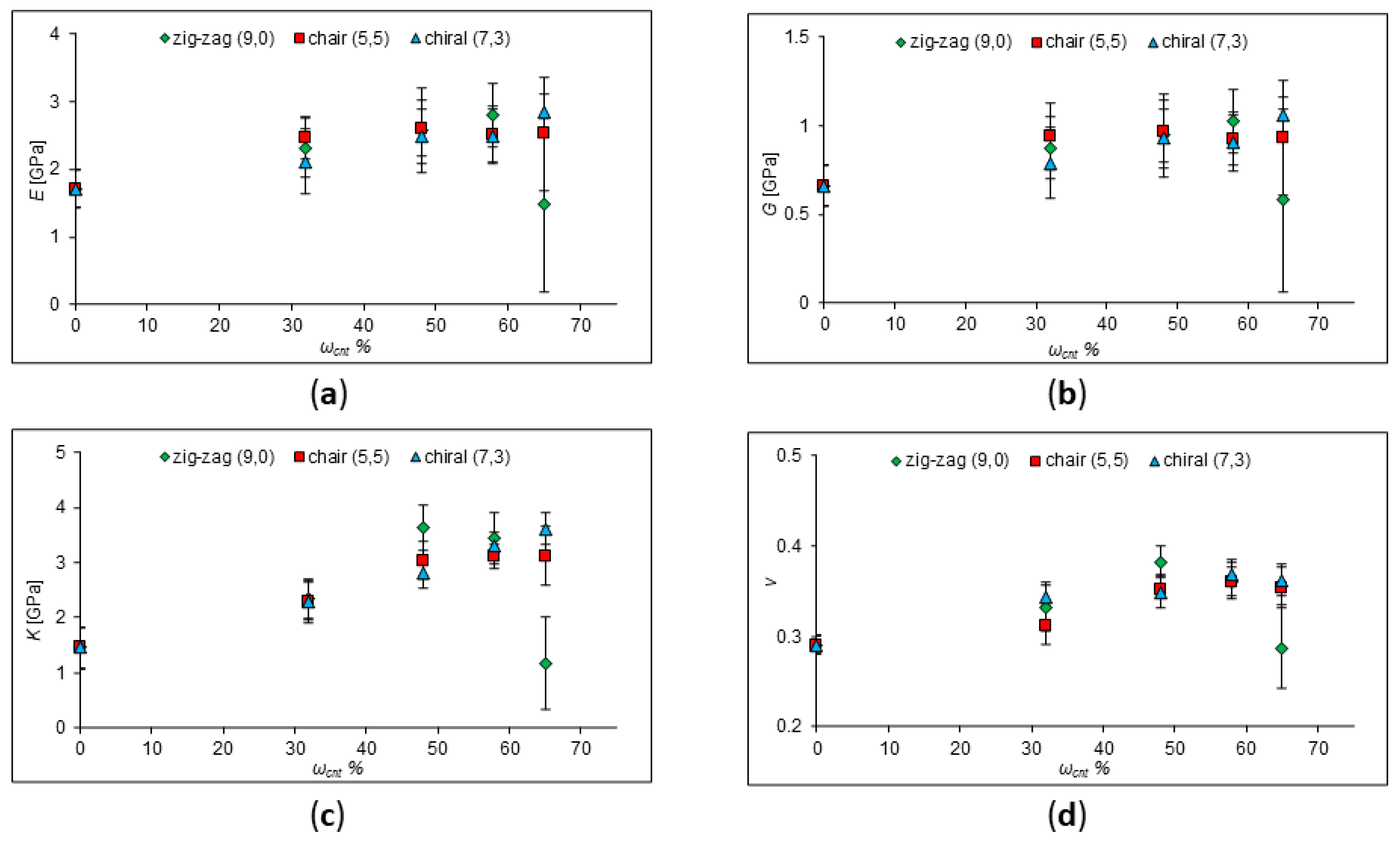

3.3. Effect of nanotube types

It is well known that a carbon nanotube is an allotropic modification of carbon, which is a hollow cylindrical structure. The nanotube has its own chirality and is characterized by two integers (m, n), which determine the mutual location of the hexagonal grids. The structure of a CNT significantly affects its properties, which can also affect the properties of composites. According to calculations of the Young's modulus, it was found that CNTs with an "armchair" and "zig-zag" configuration are stronger (E = 935.8 GPa and E = 935.3 GPa) than tubes with the same diameter, but with a chiral configuration (E = 918.3 GPa)

[39]. In the article of S. El-Borgi et

al., the chirality of CNTs significantly affected the elastic behavior of nanocomposites

[40]. Calculations by O. Aluko et

al. of epoxy/CNT nanocomposites revealed that chirality affects the mechanical characteristics of nanocomposites

[41]. A.K. Gupta et

al. investigated the effect of chirality on the properties of the composite using a multiscale simulation method and concluded that zig-zag nanotubes provide better reinforcement of the composite compared to armchair nanotubes

[42]. P. Kumar et

al. also investigated the effect of CNT chirality in a composite using computer simulations. Their results showed a strong effect of chirality at CNT volume fractions up to 0.06

[43]. Therefore, it is interesting to study the influence of the type of nanotube on the strength characteristics of polymer composites by means of molecular dynamic simulations. For this purpose, the effect of adding chair, zig-zag, and chiral nanotubes (chirality indices of nanotubes (5,5), (9,0) and (7,3), respectively, as presented in

Figure 7) on the strength characteristics of a polymer composite with a polypropylene matrix were determined and plotted in

Figure 8. The CNT diameters are the same and equal to 7 Å.

According to the dependences obtained, Young's modulus, shear modulus, Poisson's ratio, and bulk modulus do not differ much for different types of nanotubes at a high concentration of SCNTs. Therefore, it can be assumed that the type of CNTs affects the strength characteristics of the composite insignificantly, and the dispersion of CNTs, their concentration, and size have a much greater effect.

4. Conclusion

In this work, we studied the effect of nanotubes on the elastic moduli of polymer composite materials using atomistic simulation. The tendencies of the mechanical properties of composites depending on the concentration of SWCNTs were determined. In particular, it was evaluated that at low concentrations of SWCNTs, the value of the strength characteristics increases. However, after reaching the critical mass, their values decrease sharply. Besides, it was determined that with an increase in the concentration of nanotubes, the glass transition temperature of the composite increases. However, this dependence is observed only until the critical value of the filler content in the composite is reached. We obtained that the values of the elastic moduli of the polymer composite depending on the SWCNT diameter. In particular, the addition of large diameter SWCNTs can lead to a decrease in the strength characteristics of the composite. Finally, we obtained that the type of SWCNT structure did not exhibit a significant effect on the strength of the polymer composite at a high concentration of SWCNTs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.Sh. and O.N.; methodology, A.Sh.; software, A.E.; validation, A.Sh., A.E. and I.P.; formal analysis, O.N.; investigation, A.Sh.; resources, I.P.; data curation, O.N.; writing—original draft preparation, A.Sh.; writing—review and editing, I.P., O.N., D.T.; visualization, A.Sh.; supervision, O.N., D.T.; project administration, I.P.; funding acquisition, D.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper has been supported by the Kazan Federal University Strategic Academic Leadership Program (PRIORITY-2030).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Iijima, S. Helical microtubules of graphitic carbon. Nature 1991, 354, 56–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresselhaus, M. S.; Dresselhaus, G.; Saito, R. Physics of carbon nanotubes. Carbon 1995, 33, 883–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruoff, R. S.; Lorents, D. C. Mechanical and thermal properties of carbon nanotubes. Carbon 1995, 33, 925–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintmire, J. W.; White, C. T. Electronic and structural properties of carbon nanotubes. Carbon 1995, 33, 893–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, P.G.; Avouris, P. Nanotubes for electronics. Sci. Am. 2000, 283, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, T. E.; Jensen, L. R.; Kisliuk, A.; Pipes, R. B.; Pyrz, R.; Sokolov, A. P. Microscopic mechanism of reinforcement in single-wall carbon nanotube/polypropylene nanocomposite. Polymer 2005, 46, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, D.; Dickey, E. C.; Andrews, R.; Rantell, T. Load transfer and deformation mechanisms in carbon nanotube-polystyrene composites. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2000, 76, 2868–2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najipour, A.; Fattahi, A. M. Experimental study on mechanical properties of PE/CNT composites. JTAM 2017, 55, 719–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks-Sills, L.; Guy-Shiber, D.; Fourman, V.; Eliasi, R.; Shlayer, A. Experimental determination of mechanical properties of PMMA reinforced with functionalized CNTs. Compos. B. Eng. 2016, 95, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 10. Hu, Z.; Arefin, M. R. H.; Yan, X.; Fan, Q.H. Mechanical property characterization of carbon nanotube modified polymeric nanocomposites by computer modeling. Compos. B. Eng. 2014, 56, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arash, B.; Wang, Q.; Varadan, V. K. Mechanical properties of carbon nanotube/polymer composites. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikhnejad, O.; Nakamoto, T.; Kalteis, A.; Rajabtabar, A.; Major, Z. Molecular dynamic simulation of carbon nanotube reinforced nanocomposites: the effect of interface interaction on mechanical properties. MOJ Poly Sci. 2018, 2, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Elliott, J. Molecular dynamics simulations of the elastic properties of polymer/carbon nanotube composites. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2007, 39, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lordi, V.; Yao, N. Molecular mechanics of binding in carbon-nanotube–polymer composites. J. Mater. Res. 2000, 15, 2770–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, K.; Li, S. Interfacial characteristics of a carbon nanotube–polystyrene composite system. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2001, 79, 4225–4227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acierno, S.; Barretta, R.; Luciano, R.; Marotti de Sciarra, F.; Russo, P. Experimental evaluations and modeling of the tensile behavior of polypropylene/single-walled carbon nanotubes fibers. Composite Structures 2017, 174, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravchenko, T.P.; Gorbunova, I.Yu.; Filatov, S.N.; Kerber, M.L.; Rakov, E.G.; Kireev, V.V. Polypropylene-based nanostructured materials. Plasticheskie Massy. 2016, 43, 44–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.P.; Tjong, S.C. Mechanical behaviors of polypropylene/carbon nanotube nanocomposites: The effects of loading rate and temperature. Materials Science and Engineering A. 2008, 485, 508–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterzyński, T.; Tomaszewska, J.; Piszczek, K.; Skórczewska, K. The influence of carbon nanotubes on the PVC glass transition temperature. Composites Science and Technology 2010, 70, 966–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MedeA version 3.6; MedeA is a registered trademark of Materials Design, Inc., San Diego, USA.

- Hestenes, M. R.; Stiefel, E. Methods of conjugate gradients for solving linear systems. J. Res. Nat. Bur. Standards 1952, 49, 409–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiefel, E. Über einige Methoden der Relaxationsrechnung. ZAMP 1952, 3, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun,H. ; Mumby, S. J.; Maple, J. R.; Hagler A. T. Ab Initio Calculations on Small Molecule Analogs of Polycarbonates. J. Phys. Chem. 1995, 99, 5873–5882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plimpton, S.J. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. Journal of Comput. Phys. 1995, 117, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewald, P. Evaluation of Optical and Electrostatic Lattice Potentials. Ann. Phys. 1921, 64, 253–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berendsen, H.J.C.; Postma, J.P.M.; van Gunsteren, W.F.; Nola, A.D.; Haak, J.R. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J. Chem. Phys. 1984, 81, 3684–3690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Voigt, Lehrbuch Der Kristallphysik (Mit Ausschluss Der Kristalloptik); Publisher: Leipzig, Berlin, B.G. Teubner, Germany, 1928. [Google Scholar]

- Reuss, A. Berechnung der fließgrenze von mischkristallen auf grund der plastizitätsbedingung für einkristalle. ZAMM 1929, 9, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R. The elastic behaviour of a crystalline aggregate. Proc. Phys. Soc. A 1952, 65, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez Manchado, M.A.; Valentini, L.; Biagiotti, J.; Kenny, J.M. Thermal and mechanical properties of single-walled carbon nanotubes–polypropylene composites prepared by melt processing. Carbon 2005, 43, 1499–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngabonziza, Y.; Li, J.; Barry, C.F. Electrical conductivity and mechanical properties of multiwalled carbon nanotube-reinforced polypropylene nanocomposites. Acta Mech 2011, 220, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, B.; Di Maio, L.; Incarnato, L.; Tulliani, J.-M. Preparation and Characterization of Polypropylene/Carbon Nanotubes (PP/CNTs) Nanocomposites as Potential Strain Gauges for Structural Health Monitoring. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Cranford, S. W.; Minus, M. L. Nanotube Dispersion and Polymer Conformational Confinement in a Nanocomposite Fiber: A Joint Computational Experimental Study. J. Phys. Chem. B 2014, 118, 9476–9485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malagù, M.; Goudarzi, M.; Lyulin, A.; Benvenuti, E.; Simone, A. Diameter-dependent elastic properties of carbon nanotube-polymer composites: Emergence of size effects from atomistic-scale simulations. Composites Part B: Engineering 2017, 131, 260–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo F., Y.; Socher, R.; Krause, B.; Headrick, R.; Grady B., P.; Prada-Silvy, R.; Pötschke, P. Electrical, mechanical, and glass transition behavior of polycarbonate-based nanocomposites with different multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Polymer 2011, 52, 3835–3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jiang, Q.; Xu, W.; Cai, W.; Inoue, Y.; Zhu, Y. Effect of carbon nanotube length on thermal, electrical and mechanical properties of CNT/bismaleimide composites. Carbon 2013, 53, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, T. H.; Goto, K.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Premalal, E.V.A.; Shimamura, Y.; Inoue, Y.; Naito, K.; Ogihara, S. Effects of CNT diameter on mechanical properties of aligned CNT sheets and composites. Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing 2015, 76, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, M.; Lafont, U.; Norder, B.; Picken, S.J.; Samulski, E.T.; Rubinstein, M.; Dingemans, T. SWCNT induced crystallization in an amorphous all-aromatic poly(ether imide). Macromolecules 2013, 46, 1492–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WenXing, B.; ChangChun, Z.; WanZhao, C. Simulation of Young's modulus of single-walled carbon nanotubes by molecular dynamics. Physica B: Condensed Matter 2004, 352, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltaher, M.A.; El-Borgi, S.; Reddy, J.N. Nonlinear analysis of size-dependent and material-dependent nonlocal CNTs. Composite Structures 2016, 153, 902–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aluko, O.; Gowtham, S.; Odegard, G. M. The assessment of carbon nanotube (CNT) geometry on the mechanical properties of epoxy nanocomposites. J. Micromechanics Mol. Phys. 2020, 5, 2050005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Harsha, S.P. Analysis of mechanical properties of carbon nanotube reinforced polymer composites using multi-scale finite element modeling approach. Composites Part B: Engineering 2016, 95, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Srinivas, J. Numerical evaluation of effective elastic properties of CNT-reinforced polymers for interphase effects. Computational Materials Science 2014, 88, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Zhang, J.; Lin, S.; Ju, S.; Jiang, D. Effects of free organic groups in carbon nanotubes on glass transition temperature of epoxy matrix composites. Composites Science and Technology 2015, 118, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Srivastava, D.; Cho, K. Thermal Expansion and Diffusion Coefficients of Carbon Nanotube-Polymer Composites. Nano Letters 2002, 2, 647–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Kumar, D. Effect of temperature on elastic properties of CNT-polyethylene nanocomposite and its interface using MD simulations. J Mol Model 2018, 24, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

View of the simulated cell used in the present research. In this case, a cell of polypropylene is shown, consisting of 1 chain with a degree of polymerization N = 100. The molecular weight of polypropylene is Mn = 4210 g.mol-1. The nanotube has a chirality index (9;0) and a length of 18 Å. The nanotube was oriented in a random direction.

Figure 1.

View of the simulated cell used in the present research. In this case, a cell of polypropylene is shown, consisting of 1 chain with a degree of polymerization N = 100. The molecular weight of polypropylene is Mn = 4210 g.mol-1. The nanotube has a chirality index (9;0) and a length of 18 Å. The nanotube was oriented in a random direction.

Figure 2.

Calculated values of elastic moduli of pure PP and PP with SWCNT concentration of 2-10%. (a) Young's modulus behavior; (b) shear modulus behavior; (c) behavior of the bulk modulus; (d) behavior of Poisson's Ratio.

Figure 2.

Calculated values of elastic moduli of pure PP and PP with SWCNT concentration of 2-10%. (a) Young's modulus behavior; (b) shear modulus behavior; (c) behavior of the bulk modulus; (d) behavior of Poisson's Ratio.

Figure 3.

Calculated values of elastic moduli of pure PP, PEMA, PS and PP, PEMA, PS with SWCNT concentration of 19-70%. (a) Young's modulus behavior; (b) shear modulus behavior; (c) behavior of the bulk modulus; (d) behavior of Poisson's ratio.

Figure 3.

Calculated values of elastic moduli of pure PP, PEMA, PS and PP, PEMA, PS with SWCNT concentration of 19-70%. (a) Young's modulus behavior; (b) shear modulus behavior; (c) behavior of the bulk modulus; (d) behavior of Poisson's ratio.

Figure 4.

Dependence of the glass transition temperature on the mass fraction of CNTs with polypropylene matrix.

Figure 4.

Dependence of the glass transition temperature on the mass fraction of CNTs with polypropylene matrix.

Figure 5.

Dependencies of elastic moduli on different SWCNT diameters in the composite with PP matrix. SWCNT concentration in PP is 5%. (a) Young's modulus behavior; (b) shear modulus behavior; (c) behavior of the bulk modulus; (d) behavior of Poisson's Ratio.

Figure 5.

Dependencies of elastic moduli on different SWCNT diameters in the composite with PP matrix. SWCNT concentration in PP is 5%. (a) Young's modulus behavior; (b) shear modulus behavior; (c) behavior of the bulk modulus; (d) behavior of Poisson's Ratio.

Figure 6.

Dependencies of elastic moduli on different SWCNT diameters in the composite with PP and PEMA matrix. SWCNT concentration is 30%. (a) Young's modulus behavior; (b) shear modulus behavior; (c) behavior of the bulk modulus; (d) behavior of Poisson's Ratio.

Figure 6.

Dependencies of elastic moduli on different SWCNT diameters in the composite with PP and PEMA matrix. SWCNT concentration is 30%. (a) Young's modulus behavior; (b) shear modulus behavior; (c) behavior of the bulk modulus; (d) behavior of Poisson's Ratio.

Figure 7.

SWNT types used in calculations. (a) zig-zag; (b) chair; (c) chiral. The chirality indices of CNTs (m, n) are shown in the figure. In this study, they were selected so that SWNTs had approximately the same diameter 7 Å.

Figure 7.

SWNT types used in calculations. (a) zig-zag; (b) chair; (c) chiral. The chirality indices of CNTs (m, n) are shown in the figure. In this study, they were selected so that SWNTs had approximately the same diameter 7 Å.

Figure 8.

The calculated values of the elastic moduli of pure PP and PP with the addition of zig-zag, armchair and chiral SWCNTs at a concentration of 32-65%. (a) Young's modulus behavior; (b) shear modulus behavior; (c) behavior of the bulk modulus; (d) behavior of Poisson's Ratio.

Figure 8.

The calculated values of the elastic moduli of pure PP and PP with the addition of zig-zag, armchair and chiral SWCNTs at a concentration of 32-65%. (a) Young's modulus behavior; (b) shear modulus behavior; (c) behavior of the bulk modulus; (d) behavior of Poisson's Ratio.

Table 1.

Dependence of SWCNT concentration on polymer molecular weight. For each SWCNT concentration, a specific molecular weight Mn of polypropylene in the cell was selected as listed in the corresponding column. Each cell was represented by one chain consisting of N monomer units. Zig-zag nanotubes with a chirality index (9;0) and a length of 18 Å were used.

Table 1.

Dependence of SWCNT concentration on polymer molecular weight. For each SWCNT concentration, a specific molecular weight Mn of polypropylene in the cell was selected as listed in the corresponding column. Each cell was represented by one chain consisting of N monomer units. Zig-zag nanotubes with a chirality index (9;0) and a length of 18 Å were used.

SWCNT

concentration |

Mn [g.mol-1] |

N |

| pure |

4210 |

100 |

| 2% |

96232 |

2287 |

| 3% |

63500 |

1509 |

| 4% |

47136 |

1120 |

| 5% |

37315 |

887 |

| 6% |

30768 |

731 |

| 7% |

26092 |

620 |

| 8% |

22585 |

537 |

| 9% |

19857 |

472 |

| 10% |

17675 |

420 |

Table 2.

Dependence of SWCNT concentration on polymer molecular weight. In this study, zig-zag nanotubes with a chirality index (9;0) and a length of 18 Å were used. For each SWCNT concentration, a specific molecular weight Mn of PP, PEMA and PS in the cell was selected. The number of SWCNTs in a cell was n. Each cell was represented by one chain consisting of N monomer units.

Table 2.

Dependence of SWCNT concentration on polymer molecular weight. In this study, zig-zag nanotubes with a chirality index (9;0) and a length of 18 Å were used. For each SWCNT concentration, a specific molecular weight Mn of PP, PEMA and PS in the cell was selected. The number of SWCNTs in a cell was n. Each cell was represented by one chain consisting of N monomer units.

SWCNT

concentration |

n |

Mn [g.mol-1]

of PP |

N of PP |

Mn [g.mol-1] of PEMA |

N of PEMA |

Mn [g.mol-1] of PS |

N of PS |

| pure |

0 |

4210 |

100 |

4225 |

37 |

4168 |

40 |

| 19% |

1 |

8420 |

200 |

8450 |

74 |

8336 |

80 |

| 32% |

1 |

4210 |

100 |

4225 |

37 |

4168 |

40 |

| 48% |

2 |

4210 |

100 |

4225 |

37 |

4168 |

40 |

| 58% |

3 |

4210 |

100 |

4225 |

37 |

4168 |

40 |

| 65% |

4 |

4210 |

100 |

4225 |

37 |

4168 |

40 |

| 70% |

5 |

4210 |

100 |

4225 |

37 |

4168 |

40 |

Table 3.

Dependence of SWCNT diameter on polymer molecular weight. The concentration of CNTs in polypropylene is about 5%. For each SWCNT diameter, a specific molecular weight of Mn PP in the cell was chosen. The number of SWCNTs in a cell is one, (n,m) are chirality indices, l is the SWCNT length. Each cell was represented by one chain consisting of N monomer units.

Table 3.

Dependence of SWCNT diameter on polymer molecular weight. The concentration of CNTs in polypropylene is about 5%. For each SWCNT diameter, a specific molecular weight of Mn PP in the cell was chosen. The number of SWCNTs in a cell is one, (n,m) are chirality indices, l is the SWCNT length. Each cell was represented by one chain consisting of N monomer units.

SWCNT

diameter, [Å] |

(n,m) |

l, [Å] |

Mn [g.mol-1] |

N |

| - |

- |

- |

4210 |

100 |

| 4.7 |

(6,0) |

12 |

16661 |

396 |

| 5.5 |

(7,0) |

14 |

22633 |

538 |

| 6.3 |

(8,0) |

16 |

29517 |

702 |

| 7.1 |

(9,0) |

18 |

37314 |

887 |

| 7.8 |

(10,0) |

20 |

46025 |

1094 |

| 8.6 |

(11,0) |

22 |

55648 |

1323 |

Table 4.

Dependence of SWCNT diameter on polymer molecular weight. The concentration of CNTs in polymers is about 30%. For each SWCNT diameter, a specific molecular weight of Mn PP and PEMA in the cell was chosen. The number of SWCNTs in a cell is one, (n,m) are chirality indices, l is the SWCNT length. Each cell was represented by one chain consisting of N monomer units.

Table 4.

Dependence of SWCNT diameter on polymer molecular weight. The concentration of CNTs in polymers is about 30%. For each SWCNT diameter, a specific molecular weight of Mn PP and PEMA in the cell was chosen. The number of SWCNTs in a cell is one, (n,m) are chirality indices, l is the SWCNT length. Each cell was represented by one chain consisting of N monomer units.

SWCNT

diameter, [Å] |

(n,m) |

l, [Å] |

Mn [g.mol-1] of PP |

N of PP |

Mn [g.mol-1] of PEMA |

N of PEMA |

| - |

- |

- |

4210 |

100 |

4225 |

37 |

| 7.1 |

(9,0) |

18 |

4210 |

100 |

4225 |

37 |

| 9.4 |

(12,0) |

18 |

4210 |

100 |

4225 |

37 |

| 11.8 |

(15,0) |

18 |

4210 |

100 |

4225 |

37 |

| 14.1 |

(18,0) |

18 |

4210 |

100 |

4225 |

37 |

| 16.4 |

(21,0) |

18 |

4210 |

100 |

4225 |

37 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).