Submitted:

25 May 2023

Posted:

29 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

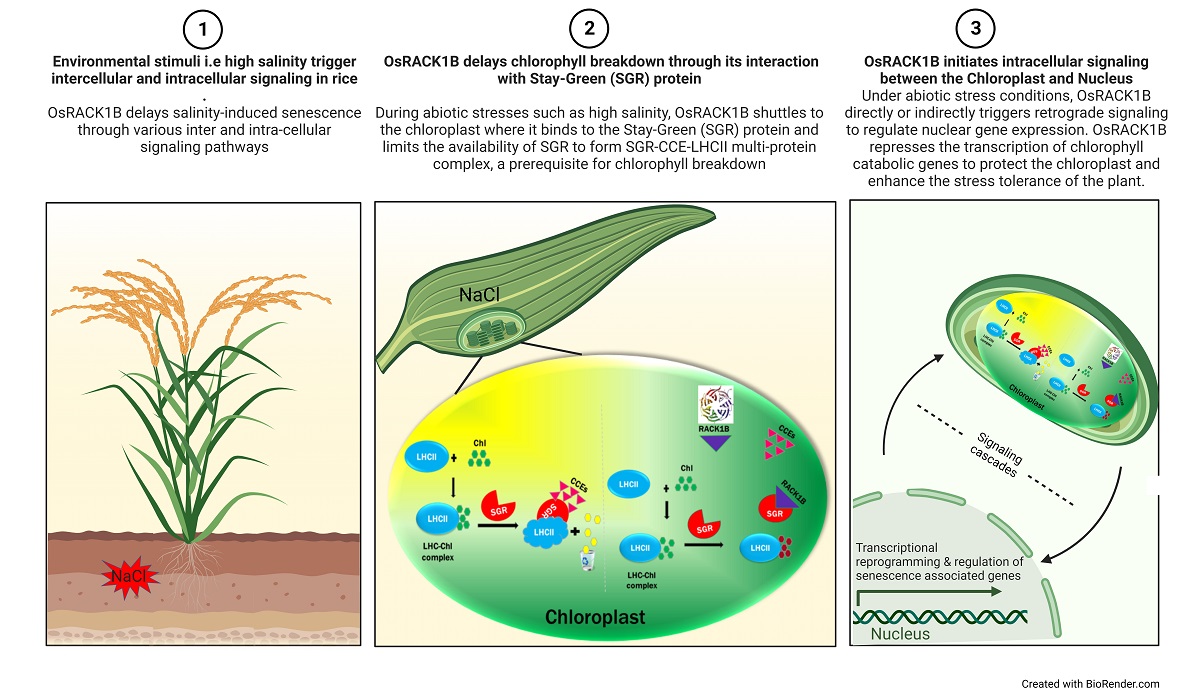

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

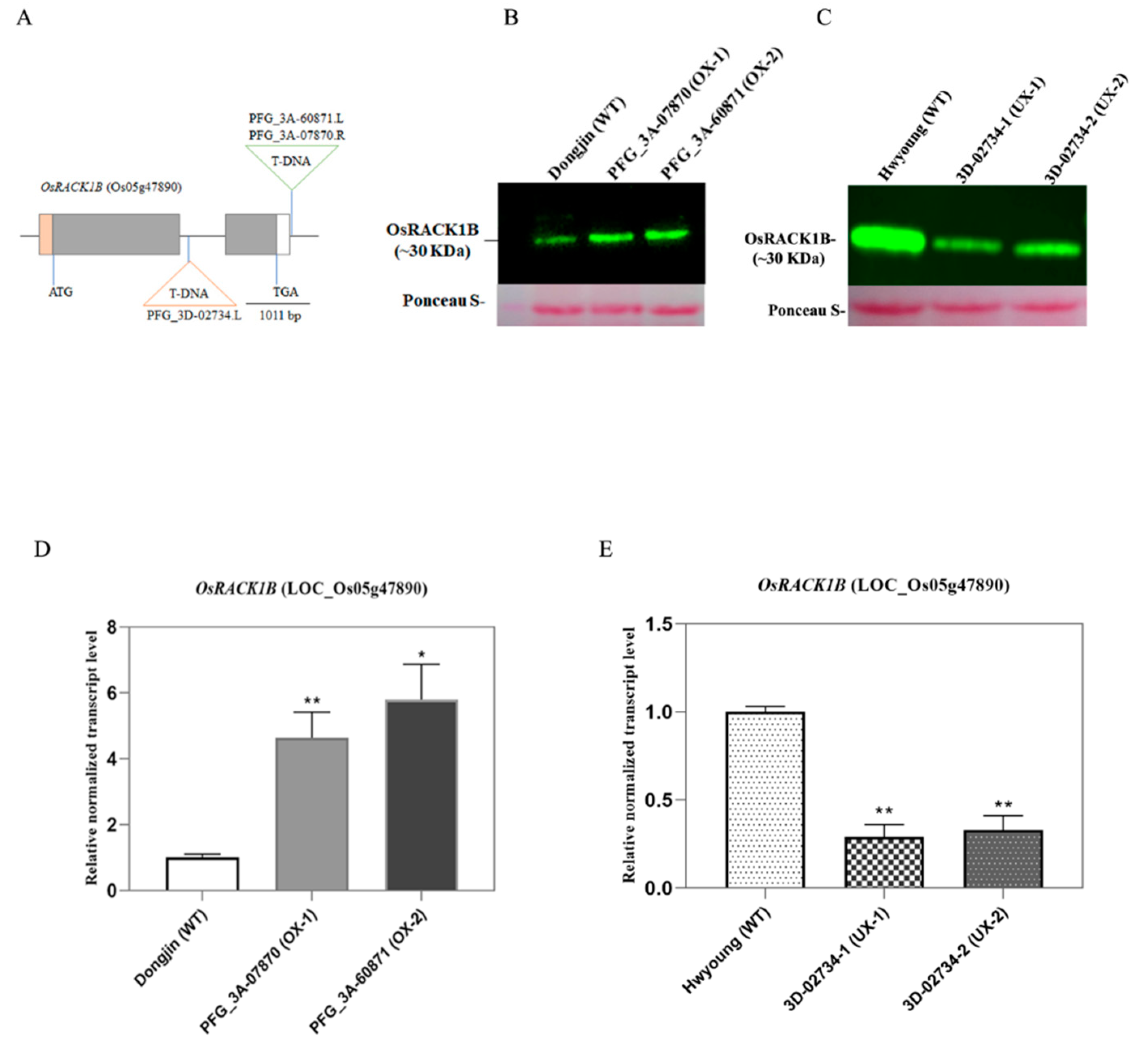

2.1. Identification of T-DNA insertion Activation Tagged rice plants overexpressing and down-regulating OsRACK1B

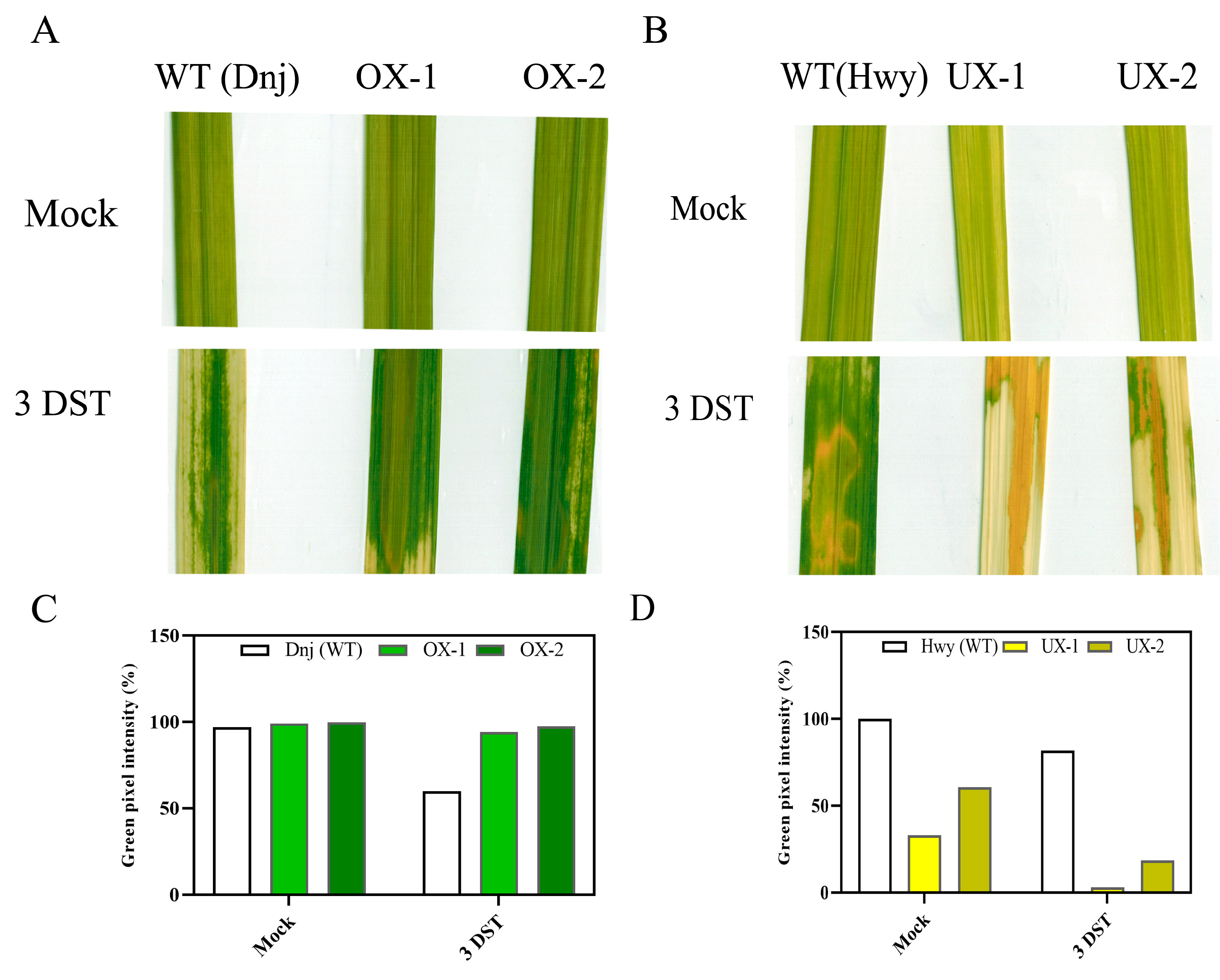

2.2. Transgenic rice plants overexpressing OsRACK1B exhibit stay-green phenotype under salinity stress

2.3. OsRACK1B down-regulated plant leaves display premature senescence in salinity stress

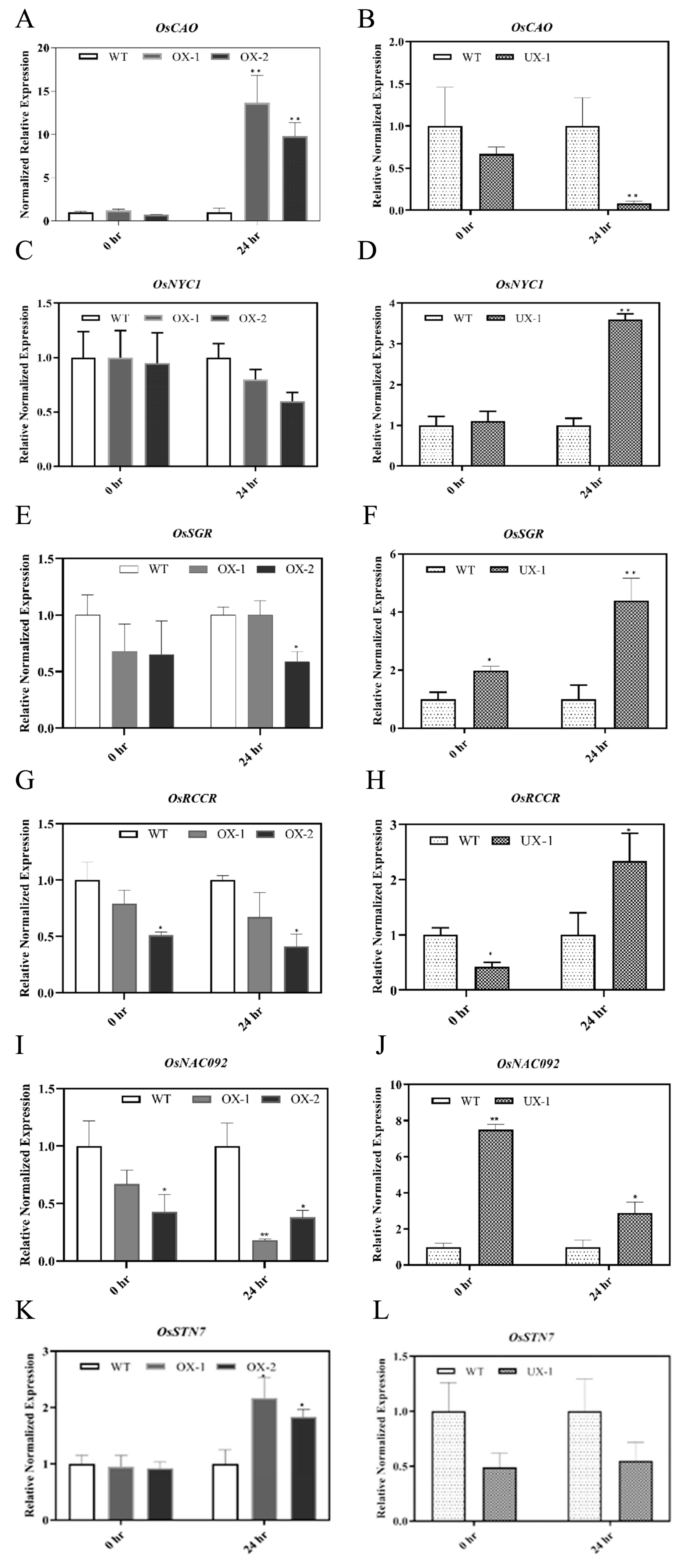

2.4. OsRACK1B negatively regulates the expression of chlorophyll degradation and senescence-associated genes

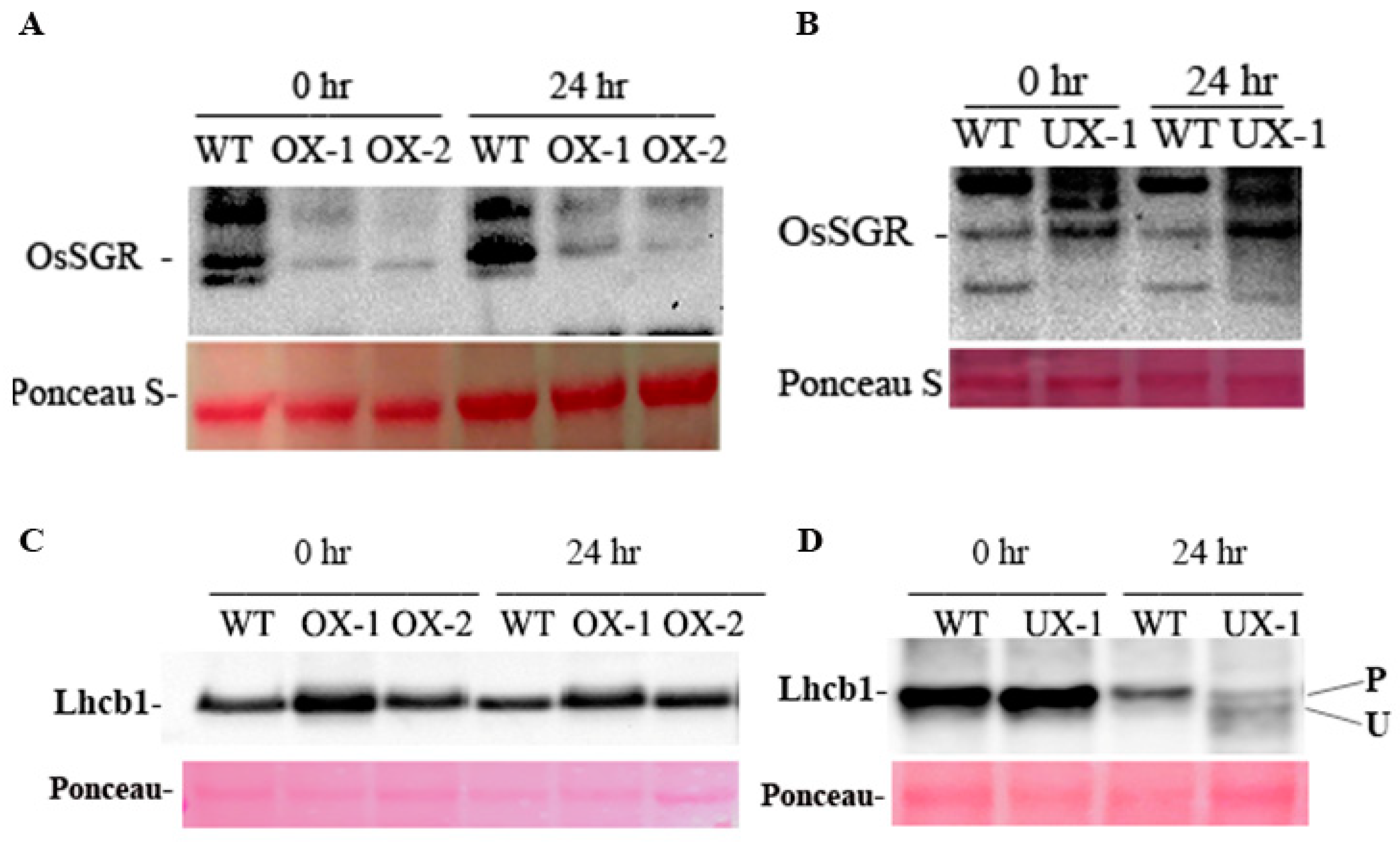

2.5. OsRACK1B regulates the expression of OsSGR

2.6. A functional OsRACK1 is required for LHCII state transition

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant materials, growth condition, and stress treatment

4.2. Genotyping of the T-DNA flanking region of OsRACK1B transgenic lines

4.3. RNA extraction, Complementary DNA (cDNA) Synthesis and quantitative Reverse Transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis

4.4. Protein Extraction and Western blot analysis

4.5. Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation (BiFC) Assay

4.6. Leaf disc assay and chlorophyll pigment analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Islas-Flores, T.; Rahman, A.; Ullah, H.; Villanueva, M.A. The Receptor for Activated C Kinase in Plant Signaling: Tale of a Promiscuous Little Molecule. Front Plant Sci 2015, 6, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, D.R.; Ron, D.; Kiely, P.A. RACK1, A multifaceted scaffolding protein: Structure and function. Cell Commun Signal 2011, 9, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCahill, A.; Warwicker, J.; Bolger, G.B.; Houslay, M.D.; Yarwood, S.J. The RACK1 scaffold protein: a dynamic cog in cell response mechanisms. Mol Pharmacol 2002, 62, 1261–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, M.H.; Flygaard, R.K.; Jenner, L.B. Structural analysis of ribosomal RACK1 and its role in translational control. Cell Signal 2017, 35, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ron, D.; Adams, D.R.; Baillie, G.S.; Long, A.; O'Connor, R.; Kiely, P.A. RACK1 to the future--a historical perspective. Cell Commun Signal 2013, 11, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, T.; Zhu, W.; Huang, W.; Lu, S.S.; Li, X.H.; Xiao, Z.Q.; Yi, H. RACK1 promotes tumorigenicity of colon cancer by inducing cell autophagy. Cell Death Dis 2018, 9, 1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.G. Phosphorylation of RACK1 in plants. Plant Signal Behav 2015, 10, e1022013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, H.; Scappini, E.L.; Moon, A.F.; Williams, L.V.; Armstrong, D.L.; Pedersen, L.C. Structure of a signal transduction regulator, RACK1, from Arabidopsis thaliana. Protein Sci 2008, 17, 1771–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.G.; Ullah, H.; Temple, B.; Liang, J.; Guo, J.; Alonso, J.M.; Ecker, J.R.; Jones, A.M. RACK1 mediates multiple hormone responsiveness and developmental processes in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot 2006, 57, 2697–2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Chen, J.G. RACK1 genes regulate plant development with unequal genetic redundancy in Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biol 2008, 8, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Fennell, H.; Ullah, H. Receptor for Activated C Kinase1B (OsRACK1B) Impairs Fertility in Rice through NADPH-Dependent H2O2 Signaling Pathway. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 8455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Wang, Y.; Shen, J.; Yin, J.; Li, D.; Gao, Y.; Xu, W.; Liang, J. OsRACK1A, encodes a circadian clock-regulated WD40 protein, negatively affect salt tolerance in rice. Rice (N Y) 2018, 11, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kundu, N.; Dozier, U.; Deslandes, L.; Somssich, I.E.; Ullah, H. Arabidopsis scaffold protein RACK1A interacts with diverse environmental stress and photosynthesis related proteins. Plant Signal Behav 2013, 8, e24012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urano, D.; Czarnecki, O.; Wang, X.; Jones, A.M.; Chen, J.G. Arabidopsis receptor of activated C kinase1 phosphorylation by WITH NO LYSINE8 KINASE. Plant Physiol 2015, 167, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakashima, A.; Chen, L.; Thao, N.P.; Fujiwara, M.; Wong, H.L.; Kuwano, M.; Umemura, K.; Shirasu, K.; Kawasaki, T.; Shimamoto, K. RACK1 functions in rice innate immunity by interacting with the Rac1 immune complex. Plant Cell 2008, 20, 2265–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T.M.; Moghaddam, L.; Williams, B.; Khanna, H.; Dale, J.; Mundree, S.G. Development of salinity tolerance in rice by constitutive-overexpression of genes involved in the regulation of programmed cell death. Front Plant Sci 2015, 6, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allu, A.D.; Soja, A.M.; Wu, A.; Szymanski, J.; Balazadeh, S. Salt stress and senescence: identification of cross-talk regulatory components. J Exp Bot 2014, 65, 3993–4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.; Harris, P. Photosynthesis under stressful environments: an overview. Photosynthetica 2013, 51, 163–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suo, J.; Zhao, Q.; David, L.; Chen, S.; Dai, S. Salinity Response in Chloroplasts: Insights from Gene Characterization. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, V.; Hille, J.; Mueller-Roeber, B.; Gechev, T.S. ROS-mediated abiotic stress-induced programmed cell death in plants. Front Plant Sci 2015, 6, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hautegem, T.; Waters, A.J.; Goodrich, J.; Nowack, M.K. Only in dying, life: programmed cell death during plant development. Trends Plant Sci 2015, 20, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balazadeh, S.; Riano-Pachon, D.M.; Mueller-Roeber, B. Transcription factors regulating leaf senescence in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Biol (Stuttg) 2008, 10 Suppl 1, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balazadeh, S.; Siddiqui, H.; Allu, A.D.; Matallana-Ramirez, L.P.; Caldana, C.; Mehrnia, M.; Zanor, M.I.; Kohler, B.; Mueller-Roeber, B. A gene regulatory network controlled by the NAC transcription factor ANAC092/AtNAC2/ORE1 during salt-promoted senescence. Plant J 2010, 62, 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz-Mendoza, M.; Velasco-Arroyo, B.; Santamaria, M.E.; Gonzalez-Melendi, P.; Martinez, M.; Diaz, I. Plant senescence and proteolysis: two processes with one destiny. Genet Mol Biol 2016, 39, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hortensteiner, S. Chlorophyll degradation during senescence. Annu Rev Plant Biol 2006, 57, 55–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hortensteiner, S.; Krautler, B. Chlorophyll breakdown in higher plants. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011, 1807, 977–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sade, N.; Del Mar Rubio-Wilhelmi, M.; Umnajkitikorn, K.; Blumwald, E. Stress-induced senescence and plant tolerance to abiotic stress. J Exp Bot 2018, 69, 845–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakuraba, Y.; Schelbert, S.; Park, S.Y.; Han, S.H.; Lee, B.D.; Andres, C.B.; Kessler, F.; Hortensteiner, S.; Paek, N.C. STAY-GREEN and chlorophyll catabolic enzymes interact at light-harvesting complex II for chlorophyll detoxification during leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusaba, M.; Ito, H.; Morita, R.; Iida, S.; Sato, Y.; Fujimoto, M.; Kawasaki, S.; Tanaka, R.; Hirochika, H.; Nishimura, M.; et al. Rice NON-YELLOW COLORING1 is involved in light-harvesting complex II and grana degradation during leaf senescence. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 1362–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Li, M.; Liang, N.; Yan, H.; Wei, Y.; Xu, X.; Liu, J.; Xu, Z.; Chen, F.; Wu, G. Molecular cloning and function analysis of the stay green gene in rice. Plant J 2007, 52, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Yu, J.W.; Park, J.S.; Li, J.; Yoo, S.C.; Lee, N.Y.; Lee, S.K.; Jeong, S.W.; Seo, H.S.; Koh, H.J.; et al. The senescence-induced staygreen protein regulates chlorophyll degradation. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 1649–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, G.; An, K.; Liao, Y.; Zhou, X.; Cao, Y.; Zhao, H.; Ge, X.; Kuai, B. Identification of a novel chloroplast protein AtNYE1 regulating chlorophyll degradation during leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 2007, 144, 1429–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuraba, Y.; Park, S.Y.; Paek, N.C. The Divergent Roles of STAYGREEN (SGR) Homologs in Chlorophyll Degradation. Mol Cells 2015, 38, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christ, B.; Hörtensteiner, S. Mechanism and significance of chlorophyll breakdown. Journal of plant growth regulation 2014, 33, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Chen, Y.; Li, M.; Xu, X.; Wu, G. Overexpression of SGR results in oxidative stress and lesion-mimic cell death in rice seedlings. J Integr Plant Biol 2011, 53, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, H.; Howarth, C.J. Five ways to stay green. Journal of experimental botany 2000, 51, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, R.S.; Lopes, M.S.; Collins, N.C.; Reynolds, M.P. Modelling and genetic dissection of staygreen under heat stress. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 2016, 129, 2055–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ülker, B.; Peiter, E.; Dixon, D.P.; Moffat, C.; Capper, R.; Bouché, N.; Edwards, R.; Sanders, D.; Knight, H.; Knight, M.R. Getting the most out of publicly available T-DNA insertion lines. The Plant Journal 2008, 56, 665–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.; Park, S.; Jeong, D.-H.; Lee, D.-Y.; Kang, H.-G.; Yu, J.-H.; Hur, J.; Kim, S.-R.; Kim, Y.-H.; Lee, M. Generation and analysis of end sequence database for T-DNA tagging lines in rice. Plant physiology 2003, 133, 2040–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, D.H.; An, S.; Park, S.; Kang, H.G.; Park, G.G.; Kim, S.R.; Sim, J.; Kim, Y.O.; Kim, M.K.; Kim, S.R.; et al. Generation of a flanking sequence-tag database for activation-tagging lines in japonica rice. Plant J 2006, 45, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murashige, T.; Skoog, F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiologia plantarum 1962, 15, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citovsky, V.; Lee, L.Y.; Vyas, S.; Glick, E.; Chen, M.H.; Vainstein, A.; Gafni, Y.; Gelvin, S.B.; Tzfira, T. Subcellular localization of interacting proteins by bimolecular fluorescence complementation in planta. J Mol Biol 2006, 362, 1120–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollender, C.A.; Liu, Z. Bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assay for protein-protein interaction in onion cells using the helios gene gun. Journal of visualized experiments: JoVE 2010.

- Sabila, M.; Kundu, N.; Smalls, D.; Ullah, H. Tyrosine Phosphorylation Based Homo-dimerization of Arabidopsis RACK1A Proteins Regulates Oxidative Stress Signaling Pathways in Yeast. Front Plant Sci 2016, 7, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiscox, J.; Israelstam, G. A method for the extraction of chlorophyll from leaf tissue without maceration. Canadian journal of botany 1979, 57, 1332–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnon, D.I. Copper Enzymes in Isolated Chloroplasts. Polyphenoloxidase in Beta Vulgaris. Plant Physiol 1949, 24, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, J.H.; Lyu, J.I.; Woo, H.R.; Lim, P.O. New insights into the regulation of leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot 2018, 69, 787–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, Y.; Ye, G.; Zeng, D. Genetic Dissection of Leaf Senescence in Rice. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, J.H.; Yoo, E.S.; Lee, C.H.; Hirochika, H.; An, G. Differential regulation of chlorophyll a oxygenase genes in rice. Plant Mol Biol 2005, 57, 805–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, R.; Koshino, Y.; Sawa, S.; Ishiguro, S.; Okada, K.; Tanaka, A. Overexpression of chlorophyllide a oxygenase (CAO) enlarges the antenna size of photosystem II in Arabidopsis thaliana. The Plant Journal 2001, 26, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuraba, Y.; Jeong, J.; Kang, M.Y.; Kim, J.; Paek, N.C.; Choi, G. Phytochrome-interacting transcription factors PIF4 and PIF5 induce leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Nat Commun 2014, 5, 4636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.J.; Liu, K.K.; Li, D.W.; Arisha, M.H.; Chai, W.G.; Gong, Z.H. Cloning and characterization of the pepper CaPAO gene for defense responses to salt-induced leaf senescence. BMC Biotechnol 2015, 15, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauf, M.; Arif, M.; Dortay, H.; Matallana-Ramirez, L.P.; Waters, M.T.; Gil Nam, H.; Lim, P.O.; Mueller-Roeber, B.; Balazadeh, S. ORE1 balances leaf senescence against maintenance by antagonizing G2-like-mediated transcription. EMBO Rep 2013, 14, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimoda, Y.; Ito, H.; Tanaka, A. Arabidopsis STAY-GREEN, Mendel's Green Cotyledon Gene, Encodes Magnesium-Dechelatase. Plant Cell 2016, 28, 2147–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hortensteiner, S. Stay-green regulates chlorophyll and chlorophyll-binding protein degradation during senescence. Trends Plant Sci 2009, 14, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rong, H.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wu, P.; Chen, Y.; Li, M.; Wu, G.; Jiang, H. The Stay-Green Rice like (SGRL) gene regulates chlorophyll degradation in rice. J Plant Physiol 2013, 170, 1367–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuai, B.; Chen, J.; Hortensteiner, S. The biochemistry and molecular biology of chlorophyll breakdown. J Exp Bot 2018, 69, 751–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, K.; Shimoda, Y.; Tanaka, A.; Ito, H. Chlorophyll a is a favorable substrate for Chlamydomonas Mg-dechelatase encoded by STAY-GREEN. Plant Physiol Biochem 2016, 109, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzykowska, M.; Suorsa, M.; Semchonok, D.A.; Tikkanen, M.; Boekema, E.J.; Aro, E.M.; Jansson, S. The light-harvesting chlorophyll a/b binding proteins Lhcb1 and Lhcb2 play complementary roles during state transitions in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 3646–3660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellafiore, S.; Barneche, F.; Peltier, G.; Rochaix, J.D. State transitions and light adaptation require chloroplast thylakoid protein kinase STN7. Nature 2005, 433, 892–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leoni, C.; Pietrzykowska, M.; Kiss, A.Z.; Suorsa, M.; Ceci, L.R.; Aro, E.M.; Jansson, S. Very rapid phosphorylation kinetics suggest a unique role for Lhcb2 during state transitions in Arabidopsis. Plant J 2013, 76, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Hoehenwarter, W. Changes in the phosphoproteome and metabolome link early signaling events to rearrangement of photosynthesis and central metabolism in salinity and oxidative stress response in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology 2015, 169, 3021–3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minagawa, J. State transitions--the molecular remodeling of photosynthetic supercomplexes that controls energy flow in the chloroplast. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011, 1807, 897–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakuraba, Y.; Kim, D.; Kim, Y.S.; Hortensteiner, S.; Paek, N.C. Arabidopsis STAYGREEN-LIKE (SGRL) promotes abiotic stress-induced leaf yellowing during vegetative growth. FEBS Lett 2014, 588, 3830–3837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cha, K.W.; Lee, Y.J.; Koh, H.J.; Lee, B.M.; Nam, Y.W.; Paek, N.C. Isolation, characterization, and mapping of the stay green mutant in rice. Theor Appl Genet 2002, 104, 526–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morita, R.; Sato, Y.; Masuda, Y.; Nishimura, M.; Kusaba, M. Defect in non-yellow coloring 3, an alpha/beta hydrolase-fold family protein, causes a stay-green phenotype during leaf senescence in rice. Plant J 2009, 59, 940–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Li, M.; Chen, Y.; Wu, P.; Wu, G.; Jiang, H. Knockdown of OsPAO and OsRCCR1 cause different plant death phenotypes in rice. J Plant Physiol 2011, 168, 1952–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pruzinska, A.; Anders, I.; Aubry, S.; Schenk, N.; Tapernoux-Luthi, E.; Muller, T.; Krautler, B.; Hortensteiner, S. In vivo participation of red chlorophyll catabolite reductase in chlorophyll breakdown. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruzinska, A.; Tanner, G.; Anders, I.; Roca, M.; Hortensteiner, S. Chlorophyll breakdown: pheophorbide a oxygenase is a Rieske-type iron-sulfur protein, encoded by the accelerated cell death 1 gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003, 100, 15259–15264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, Y.; Morita, R.; Katsuma, S.; Nishimura, M.; Tanaka, A.; Kusaba, M. Two short-chain dehydrogenase/reductases, NON-YELLOW COLORING 1 and NYC1-LIKE, are required for chlorophyll b and light-harvesting complex II degradation during senescence in rice. Plant J 2009, 57, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakizaki, T.; Inaba, T. New insights into the retrograde signaling pathway between the plastids and the nucleus. Plant Signal Behav 2010, 5, 196–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamaitha, M.J.; Yamamoto, R.; Wong, H.L.; Kawasaki, T.; Kawano, Y.; Shimamoto, K. OsRap2.6 transcription factor contributes to rice innate immunity through its interaction with Receptor for Activated Kinase-C 1 (RACK1). Rice (N Y) 2012, 5, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dongping, Z.; Li, C.; Bing, L.; Jiansheng, L. The scaffolding protein RACK1: a platform for diverse functions in the plant kingdom. Journal of Plant Biology & Soil Health 2013, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.J.; Xie, D. RACK1, a versatile hub in cancer. Oncogene 2015, 34, 1890–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pulido, P.; Zagari, N.; Manavski, N.; Gawronski, P.; Matthes, A.; Scharff, L.B.; Meurer, J.; Leister, D. CHLOROPLAST RIBOSOME ASSOCIATED Supports Translation under Stress and Interacts with the Ribosomal 30S Subunit. Plant Physiol 2018, 177, 1539–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstead, I.; Donnison, I.; Aubry, S.; Harper, J.; Hortensteiner, S.; James, C.; Mani, J.; Moffet, M.; Ougham, H.; Roberts, L.; et al. Cross-species identification of Mendel's I locus. Science 2007, 315, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barry, C.S.; McQuinn, R.P.; Chung, M.Y.; Besuden, A.; Giovannoni, J.J. Amino acid substitutions in homologs of the STAY-GREEN protein are responsible for the green-flesh and chlorophyll retainer mutations of tomato and pepper. Plant Physiol 2008, 147, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Han, L.; Pislariu, C.; Nakashima, J.; Fu, C.; Jiang, Q.; Quan, L.; Blancaflor, E.B.; Tang, Y.; Bouton, J.H.; et al. From model to crop: functional analysis of a STAY-GREEN gene in the model legume Medicago truncatula and effective use of the gene for alfalfa improvement. Plant Physiol 2011, 157, 1483–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuraba, Y.; Park, S.Y.; Kim, Y.S.; Wang, S.H.; Yoo, S.C.; Hortensteiner, S.; Paek, N.C. Arabidopsis STAY-GREEN2 is a negative regulator of chlorophyll degradation during leaf senescence. Mol Plant 2014, 7, 1288–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Yang, C.; Wang, T.; Ouyang, B.; Li, H.; Giovannoni, J.; Ye, Z. A STAY-GREEN protein SlSGR1 regulates lycopene and beta-carotene accumulation by interacting directly with SlPSY1 during ripening processes in tomato. New Phytol 2013, 198, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, H.; Yoshimoto, K. Chloroplasts are partially mobilized to the vacuole by autophagy. Autophagy 2008, 4, 961–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izumi, M.; Nakamura, S. Chloroplast Protein Turnover: The Influence of Extraplastidic Processes, Including Autophagy. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, S.; Ishida, H.; Izumi, M.; Yoshimoto, K.; Ohsumi, Y.; Mae, T.; Makino, A. Autophagy plays a role in chloroplast degradation during senescence in individually darkened leaves. Plant Physiol 2009, 149, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Blumwald, E. Stress-induced chloroplast degradation in Arabidopsis is regulated via a process independent of autophagy and senescence-associated vacuoles. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 4875–4888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fristedt, R.; Willig, A.; Granath, P.; Crevecoeur, M.; Rochaix, J.-D.; Vener, A.V. Phosphorylation of photosystem II controls functional macroscopic folding of photosynthetic membranes in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 2009, 21, 3950–3964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonardi, V.; Pesaresi, P.; Becker, T.; Schleiff, E.; Wagner, R.; Pfannschmidt, T.; Jahns, P.; Leister, D. Photosystem II core phosphorylation and photosynthetic acclimation require two different protein kinases. Nature 2005, 437, 1179–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaresi, P.; Hertle, A.; Pribil, M.; Kleine, T.; Wagner, R.; Strissel, H.; Ihnatowicz, A.; Bonardi, V.; Scharfenberg, M.; Schneider, A.; et al. Arabidopsis STN7 kinase provides a link between short- and long-term photosynthetic acclimation. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 2402–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregersen, P.L.; Culetic, A.; Boschian, L.; Krupinska, K. Plant senescence and crop productivity. Plant molecular biology 2013, 82, 603–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sade, N.; Umnajkitikorn, K.; Rubio Wilhelmi, M.d.M.; Wright, M.; Wang, S.; Blumwald, E. Delaying chloroplast turnover increases water-deficit stress tolerance through the enhancement of nitrogen assimilation in rice. Journal of experimental botany 2017, 69, 867–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).