Submitted:

25 May 2023

Posted:

29 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

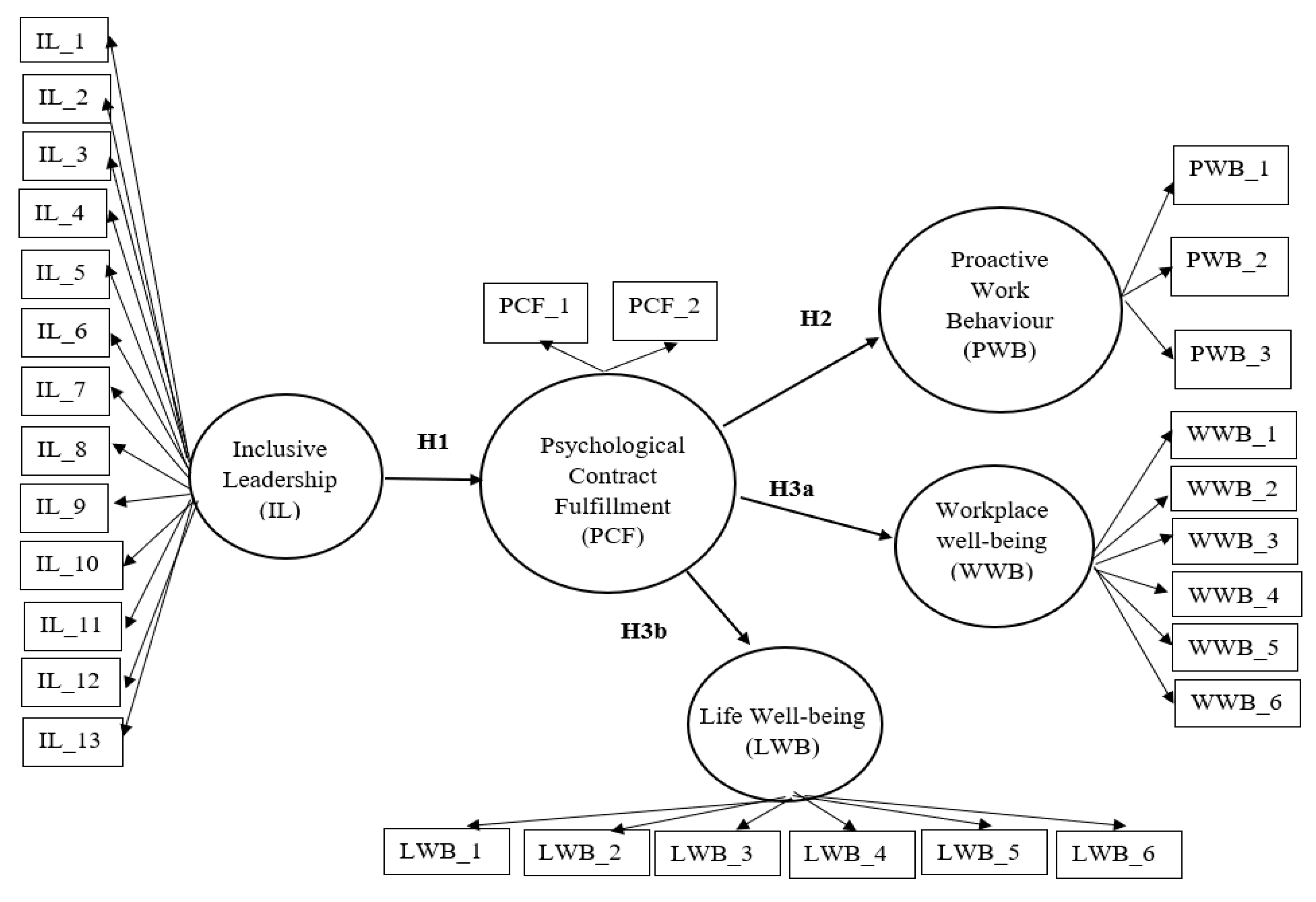

2. Theoretical Framework and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Inclusive Leadership and the Fulfillment of the Psychological Contract

2.2. The Psychological contract Fulfillment and Proactive Work Behavior

2.3. Psychological Contract Fulfillment and Employee Well-being

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Procedure and Participants of the Study

3.2. Research Instruments

4. Results

4.1. Statistical Analysis

4.2. Reliability and Validity Analysis

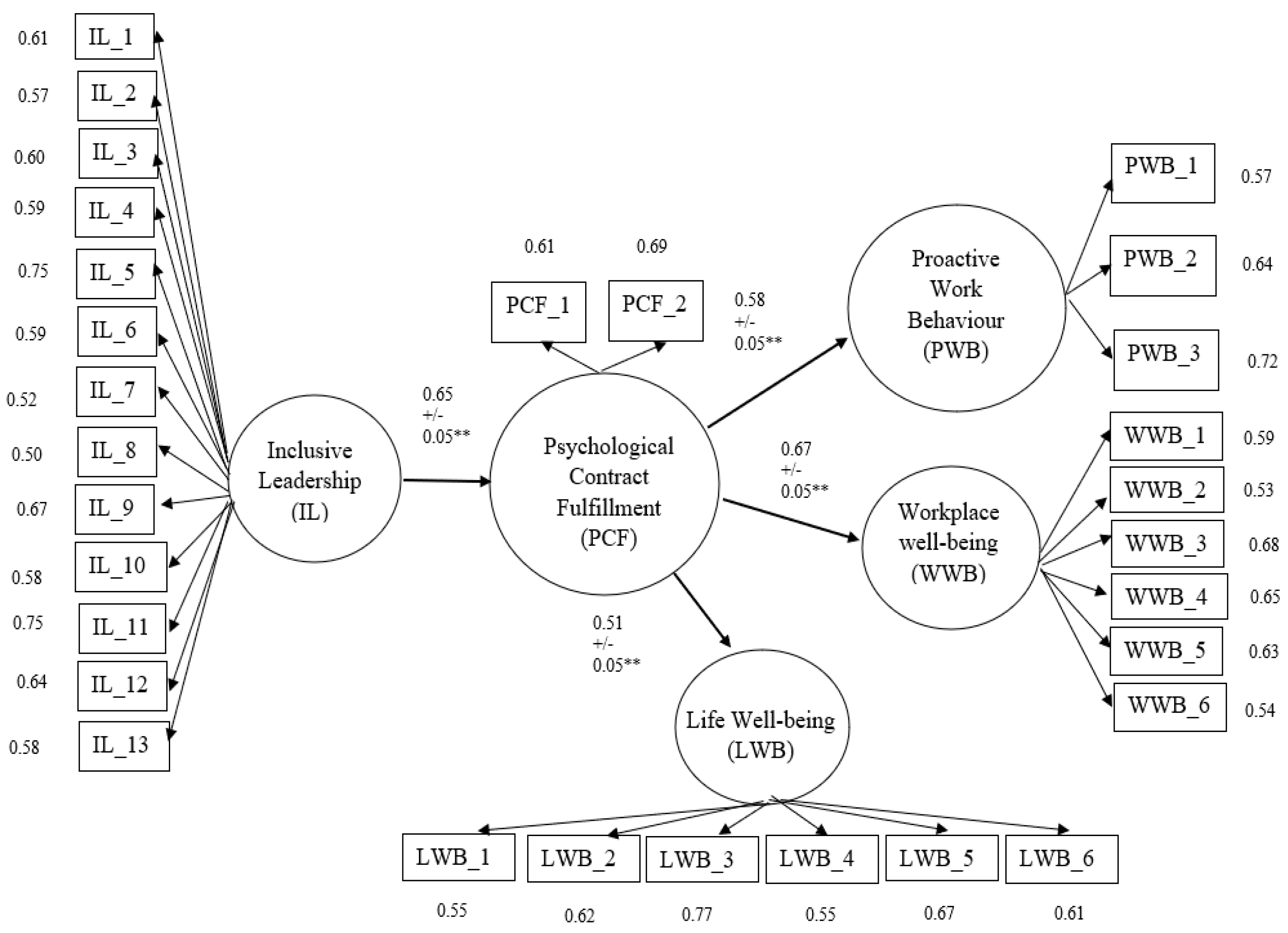

4.3. Measurement Model

4.4. Structural Model

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Further Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brinkmann, S. ; Character, personality, and identity: On historical aspects of human subjectivity. Nord. Psychol. 2010, 62, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Donovan, R.; McAuliffe, E. Exploring psychological safety in healthcare teams to inform the development of interventions: combining observational, survey and interview data. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruokolainen, M.; Mauno, S.; Diehl, M.R.; Tolvanen, A.; Mäkikangas, A.; Kinnunen, U. Patterns of psychological contract and their relationships to employee well-being and in-role performance at work: Longitudinal evidence from university employees. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 29, 2827–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S. Why the Emotional WellBeing of Your Employees Should Be a Top Priority during COVID-19. Tata Consultancy Services, India, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, K.; Parker, S.K. Intervening to enhance proactivity in organizations: Improving the present or changing the future. J. Manage. 2018, 44, 1250–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nembhard, I.M.; Edmondson, A.C. Making it safe: The effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams. J. Organ. Behav. 2006, 27, 941–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Zafar, M.A. Impact of psychological contract fulfillment on organizational citizenship behavior. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag., Emerald Publishing Limited, 2018; 30, 1001–1015. [Google Scholar]

- Korkmaz, A.V.; van Engen, M.L.; Knappert, L.; Schalk, R. About and beyond leading uniqueness and belongingness: A systematic review of inclusive leadership research. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2022, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, J.; Biswas, S. . The mediator analysis of psychological contract: relationship with employee engagement and organisational commitment. Int. J. Indian Cult. Bus. Manag., Inderscience Enterprises Ltd. 2012, 5, 644–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogozińska-Pawełczyk, A. Work satisfaction and the relationship between the psychological contract and an employee’s intention to quit. The results of a survey of public administration employees in Poland. J. East Eur. Manag. 2020, 25, 301–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S.; Jena, D.; Patnaik, S. Mediation framework connecting knowledge contract, psychological contract, employee retention, and employee satisfaction: An empirical study. Int. J. Eng. Bus. Manag. 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, H.; Mert, I.S.; Sen, C. The effect of inclusive leadership on the work engagement: an empirical study from Turkey, J. Asian Finance Econ. Bus. 2021, 8, 169–178. [Google Scholar]

- Carmeli, A.; Reiter-Palmon, R.; Ziv, E. Inclusive leadership and employee involvement in creative tasks in the workplace: The mediating role of psychological safety. Creat. Res. J. 2010, 22, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randel, A.E.; Galvin, B.M.; Shore, L.M.; Ehrhart, K.H.; Chung, B.G.; Dean, M.A.; Kedharnath, U. Inclusive leadership: Realizing positive outcomes through belongingness and being valued for uniqueness. Hum. Resour. Manag Rev. 2018, 28, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.; Kim, S.; Kim, K.; Cho, A.; Chang, W. Conceptualizing meaningful work and its implications for HRD. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2020, 45, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashikali, T.; Groeneveld, S.; Kuipers, B. The Role of Inclusive Leadership in Supporting an Inclusive Climate in Diverse Public Sector Teams. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2021, 41, 497–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minehart, R.D.; Foldy, E.G.; Long, J.A. , Weller, J.M. Challenging gender stereotypes and advancing inclusive leadership in the operating theatre. Br. J. Anaesth. 2020, 124, e148–e154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meeuwissen, S.N.E.; Gijselaers, W.H.; van Oorschot, T.D.; Wolfhagen, I.H.A.P.; Oude Egbrink, M.G.A. Enhancing team learning through leader inclusiveness: A one-year ethnographic case study of an interdisciplinary teacher team. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Ferdman, B.M.; Deane, B.R. Diversity at work: The practice of inclusion. John Wiley & Sons, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, U.A.; Dixit, V.; Nikolova, N.; Jain, K.; Sankaran, S. A psychological contract perspective of vertical and distributed leadership in project-based organizations, Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2021, 39, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, U.A.; Avey, J.B. Abusive supervisors and employees who cyberloaf: Examining the roles of psychological capital and contract breach. Internet Res. 2020, 30, 789–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oorschot, J.; Moscardo, G.; Blackman, A. Leadership style and psychological contract. Aust. J. Career Dev. 2021, 30, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and power in social life. Transaction Publishers, 1964.

- Levinsonv, H.; Price, C.R.; Munden, K.J.; Mandl, H.J.; Solley, C.M. Men, Management, and Mental Health. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1962.

- Schein, E.H. Organisational Psychology, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs–New York,1965.

- Rousseau, D.M. Psychological and implied contracts in organisations. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 1989, 2, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulac, T.; Coyle-Shapiro, J.A.; Henderson, D.J.; Wayne, S.J. Not all responses to breach are the same: The interconnection of social exchange and psychological contract processes in organizations. Acad. Manage. J. 2008, 51, 1079–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadomska-Lila, K.; Rogozińska-Pawełczyk, A. The Role of Pro-Innovative HR Practices and Psychological Contract in Shaping Employee Commitment and Satisfaction: A Case from the Energy Industry. Energies. 2021, 15, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M.; Parker, S.K. 7 redesigning work design theories: the rise of relational and proactive perspectives. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2009, 3, 317–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bammens, Y.P. Employees’ innovative behavior in social context: A closer examination of the role of organizational care. J Prod Innov. Manage. 2016, 33, 244–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibert, S.E.; Kraimer, M.L.; Crant, J.M. What do proactive people do? A longitudinal model linking proactive personality and career success. Pers. Psychol. 2001, 54, 845–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammeyer-Mueller, J.D.; Livingston, B.A.; Liao, H. Perceived similarity, proactive adjustment, and organizational socialization. J. Vocat. Behav. 2011, 78, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkutlu, H.; Chafra, J. Effects of trust and psychological contract violation on authentic leadership and organizational deviance. Manag. Res. Rev. 2013, 36, 828–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philipp, B.L.U.; Lopez, P.D.J. The moderating role of ethical leadership: Investigating relationships among employee psychological contracts, commitment, and citizenship behavior. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2013, 20, 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogozińska-Pawełczyk, A.; Gadomska-Lila, K. The Mediating Role of Organisational Identification between Psychological Contract and Work Results: An Individual Level Investigation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022, 19, 5404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D. Psychological well-being revisited: advances in science and practice. Psychother. Psychosom. 2014, 83, 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggeri, K.; Garcia-Garzon, E.; Maguire, Á.; Matz, S.; Huppert, F.A. Well-being is more than happiness and life satisfaction: a multidimensional analysis of 21 countries. Psychother. Psychosom. 2020, 18, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K. ; Noblet, A J. Organisational interventions for health and well-being: A handbook for evidence-based practice. Routledge, 2018.

- Jeffrey, K.; Mahony, S.; Michaelson, J.; Abdallah, S. Wellbeing at Work: A Review of the Literature. New Economics Foundation, London, 2014.

- Carolan, S.; Harris, P.R.; Cavanagh, K. Improving employee well-being and effectiveness: Systematic review and meta-analysis of web-based psychological interventions delivered in the workplace. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, A. Conceptualizing and measuring occupational social well-being: a validation study. Int. J. Organ, Emerald Publishing Limited, 2017; 25, 45–61. [Google Scholar]

- Meske, C. and Junglas, I. Investigating the elicitation of employees’ support towards digital workplace transformation, Behaviour and Information Technology. Taylor & Francis, 2020.

- Zheng, X.; Zhu, W.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, C. Employee well-being in organizations: theoretical model, scale development, and cross-cultural validation, J. Organ. Behav. 2015, 36, 621–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, P.I.Jr.; Finkel, E.J.; Fitzsimons, G.M.; Gino, F. The energizing nature of work engagement: toward a new need-based theory of work motivation. Res. Organ. Behav. 2017, 37, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagán-Castaño, E.; Maseda-Moreno, A.; Santos-Rojo, C. Wellbeing in work environments. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 115, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeg, M.; May, D.R. The Benefits to the Human Spirit of Acting Ethically at Work: The Effects of Professional Moral Courage on Work Meaningfulness and Life Well-Being. J. Bus. Ethics. 2021, 181, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Boltz, A.; Wang, C.W.; Lee, M.K. Algorithmic management reimagined for workers and by workers: centering worker well-being in gig work, CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. 2022.

- Cooke, P.J.; Melchert, T.P.; Connor, K. Measuring well-being: A review of instruments. Couns. Psychol. 2016, 44, 730–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.; Robertson, I.; Cooper, C.L. Well-being: Productivity and happiness at work. Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

- Van der Vaart, L.; Linde, B.; De Beer, L.; Cockeran, M. Employee well-being, intention to leave and perceived employability: A psychological contract approach. S. Afr. J. Econ. Manag, 2015; 18, 32–44. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M. PERMA and the building blocks of well-being. J. Posit. Psychol. 2018, 13, 333–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.I.; Firman, K.; Smith, H.N.; Smith, A. Psychological contract fulfilment and wellbeing. Adv. Soc. Sci. Res. J. 2018, 5, 90–101. [Google Scholar]

- ABSL Sektor nowoczesnych usług biznesowych w Polsce 2022. 2023. https://absl.pl/storage/app/uploads/public/5ee/887/8d5/5ee8878d59858995982318.pdf.

- Groves, R.M.; Fowler, F.J.; Couper, M.P.; Lepkowski, J.M.; Singer, E.; Tourangeau, R. Survey Methodology; Wiley: New York, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E. Method variance as an artifact in self-reported affect and perceptions at work: Myth or significant problem. J. Appl. Psychol. 1987, 72, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinzi, V.; Chin, W.; Henseler, J. Handbook of Partial Least Squares, Concepts, Methods and Applications. Springer-Verlag. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Stratton, S.J. Population Research: Convenience Sampling Strategies. Prehosp. Disaster. Med. 2021, 36, 373–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashikali, T. Leading Towards Inclusiveness: Developing a Measurement Instrument for Inclusive Leadership. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2019; 16444. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau, D.M.; Tijoriwala, S.A. Assessing psychological contracts: Issues, alternatives, and types of measures. J. Organ. Behav. 1998, 19, 679–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, D.; Conway, N. Communicating the psychological contract: An employer’s perspective. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2002, 12, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.K.; Collins, C.G. Taking stock: integrating and differentiating multiple proactive behaviors, J. Manage. 2010, 36, 633–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behling, O.; Law, K.S. Translating questionnaires and other research instruments. Problems and solutions. Series: Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences, Sage Publications. 2000.

- Jacobsen, C.B.; Andersen, L.B. Is leadership in the eye of the beholder? A study of intended and perceived leadership practices and organizational performance. Public Adm. Rev. 2015, 75, 829–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, JC. Psychometric Theory. McGraw-Hill: NY, 1978.

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Mena, J.A. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, M.; Diener, E. Intraindividual Variability in Affect: Reliability, Validity, and Personality Correlates. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 76, 662–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, P. Structural equation modeling: Adjudging model fit. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2007, 42, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, A.; Farrukh, M. , Wu, Y.; Abdul Wahab, S. Does inclusive leadership incite innovative work behavior? Hum. Syst. Manag. 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Stinglhamber, F.; Vandenberghe, C.; Sucharski, I.L.; Rhoades, L. Perceived supervisor support: contributions to perceived organizational support and employee retention. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 87, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xanthopoulou, B.; Demerouti, A.B.; Schaufeli, E.; Wilmar, B. Work engagement and financial returns: a diary study on the role of job and personal resources. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2009, 82, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillie, P.; Raineri, N. Linking perceived corporate environmental policies and employees eco-initiatives: the influence of perceived organizational support and psychological contract breach. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 2404–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, M.E.; Mosquera, P. “Fostering work engagement: the role of the psychological contract. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 101, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A.M.; Bartels, L.K. The impact of onboarding levels on perceived utility, organizational commitment, organizational support, and job satisfaction. J. Organ. Psychol. 2017, 17, 10–27. [Google Scholar]

- Siegrist, J.; Li, J. Associations of extrinsic and intrinsic components of work stress with health: A systematic review of evidence on the effort-reward imbalance model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2016, 13, 432–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, J.R.; Diehl, M.R.; Dougan, W. Towards a social-cognitive theory of multiple psychological contracts. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psy. 2020, 29, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criteria | Values | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | ||

| 1000 | 100.0 | ||

| Gender | Male | 433 | 43.3 |

| Female | 567 | 56.7 | |

| Age | Under 30 years | 53 | 5.3 |

| 30-39 years | 341 | 34.1 | |

| 40-49 years | 323 | 32.3 | |

| 50-54 years | 185 | 18.5 | |

| 55 and over | 97 | 9.7 | |

| Education level | Bachelor | 75 | 7.5 |

| Master | 824 | 82.4 | |

| PhD. | 75 | 7.5 | |

| Prof. | 26 | 2.6 | |

| Total length of service | Up to 5 years | 56 | 5.6 |

| 6 - 10 years | 132 | 13.2 | |

| Over 10 years | 811 | 81.1 | |

| Length of service with current company | Up to one year | 81 | 8.1 |

| One to five years | 350 | 35.0 | |

| 6 - 10 years | 290 | 29.0 | |

| Over 10 years | 279 | 27.9 | |

| Size of the organisation's workforce | 10-49 | 279 | 27.9 |

| 50-249 | 298 | 29.8 | |

| 250 or more | 423 | 42.3 | |

| Form of ownership of the organisation | Public | 110 | 11.0 |

| Prywate | 890 | 89.0 | |

| Type of work position | Manager | 500 | 50.0 |

| Non-manager | 500 | 50.0 | |

| Dimentions | M | Me | SD | S | K | p | IL | PCF | PWB | WWB | LWB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL | 4.18 | 3 | 1.05 | -0.10 | -0.48 | <0,001*** | 1.00 | ||||

| PCF | 5.72 | 5 | 1.18 | -0.33 | -0.42 | <0,009*** | 0.243*** | 1.00 | |||

| PWB | 5.25 | 3 | 0.89 | -0.09 | -0.45 | <0,001*** | 0.176*** | 0.140*** | 1.00 | ||

| WWB | 6.12 | 5 | 1.23 | -.024 | -0.39 | <0,001*** | 0.114*** | 0.136*** | 0.122*** | 1.00 | |

| LWB | 6.22 | 5 | 1.27 | -0.15 | -0.28 | <0,001*** | 0.201*** | 0.108*** | 0.119*** | 0.206*** | 1.00 |

| Specification | IL | PCF | PWB | WWB | LWB | EWB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KMO | 0.851 | 0.776 | 0.724 | 0.816 | 0.732 | 0.830 |

| Bartlett's sphericity test | χ2 (13) = 1062.5 p < 0.001** |

χ2 (17) = 2561.2 p < 0.001** |

χ2 (24) = 2614.0 p < 0.001** |

χ2 (6) = 2264.1 p < 0.001** |

χ2 (6) = 1056.1 p < 0.001** |

χ2 (12) = 2041.5 p < 0.001** |

| Cronbach's Alpha | 0.874 | 0.814 | 0.791 | 0.803 | 0.859 | 0.896 |

| Factor | Value factor |

|---|---|

| χ2 =1845.7, df =953 p < 0,0001 | |

| χ2 df = 1.937 | |

| RMSEA | 0.059 |

| 90% CI | 0.058-0.061 |

| CFI | 0.909 |

| GFI | 0.864 |

| AGFI | 0.919 |

| SRMR | 0.06 |

| CR | α | AVE | IL | PCF | PWB | WWB | LWB | EWB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL | 0.79 | 0.87 | 0.52 | - | |||||

| PCF | 0.86 | 0.81 | 0.49 | 0.19*** | - | ||||

| PWB | 0.90 | 0.79 | 0.41 | 0.14*** | 0.61*** | - | |||

| WWB | 0.89 | 0.80 | 0.49 | 0.24*** | 0.49*** | 0.21*** | - | ||

| LWB | 0.88 | 0.86 | 0.51 | 0.22*** | 0.71*** | 0.28*** | 0.76*** | - | |

| EWB | 0.91 | 0,90 | 0.49 | 0.31*** | 0.56*** | 0.49*** | 0.51*** | 0.49*** | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).