Submitted:

25 May 2023

Posted:

26 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Ti substrates

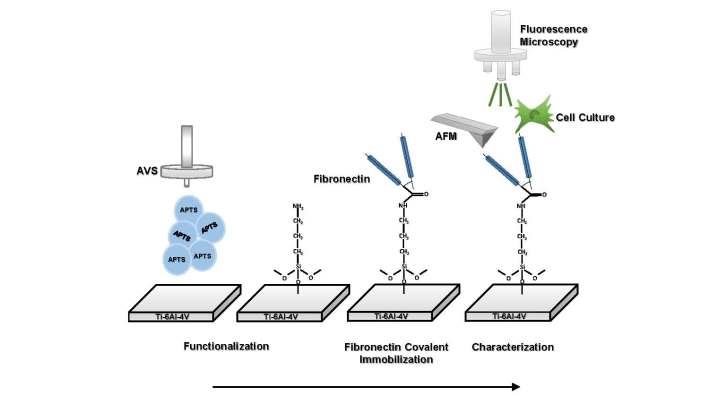

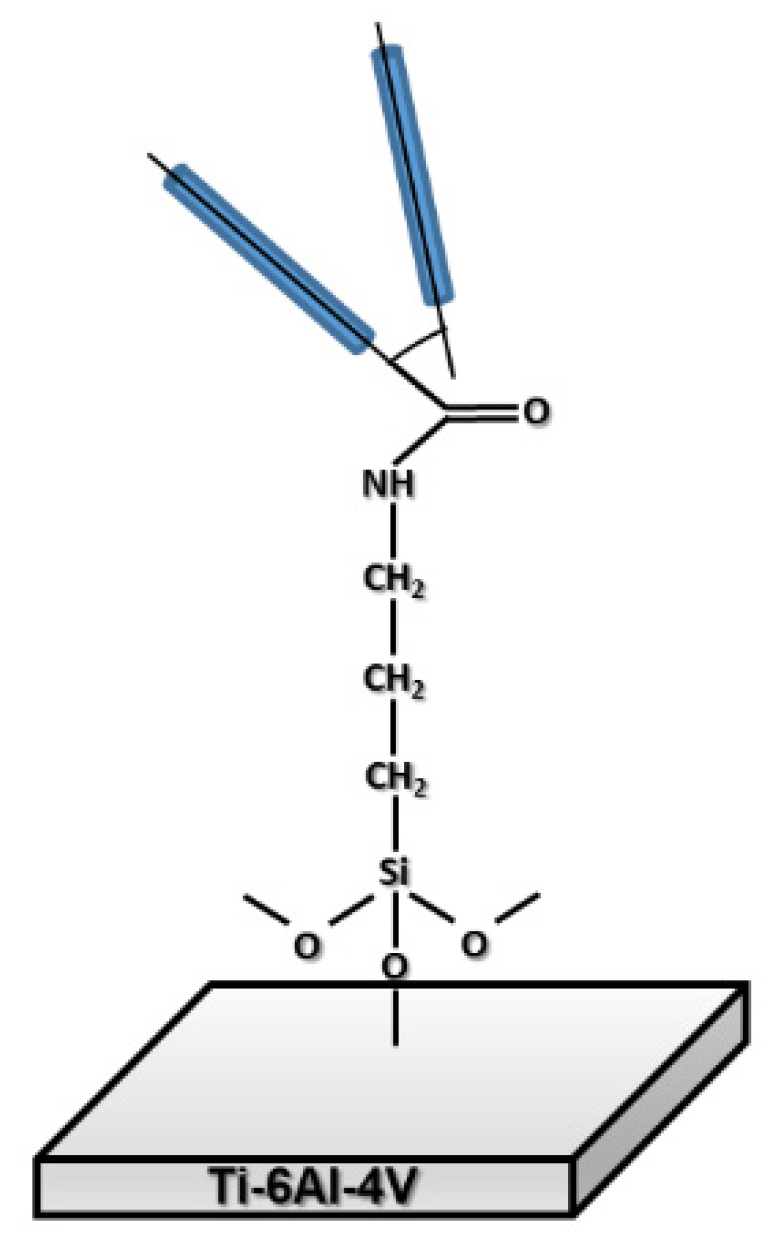

2.2. Covalent immobilization of fibronectin

2.2.1. Functionalization

2.2.2. Covalent immobilization of fibronectin on Ti substrates

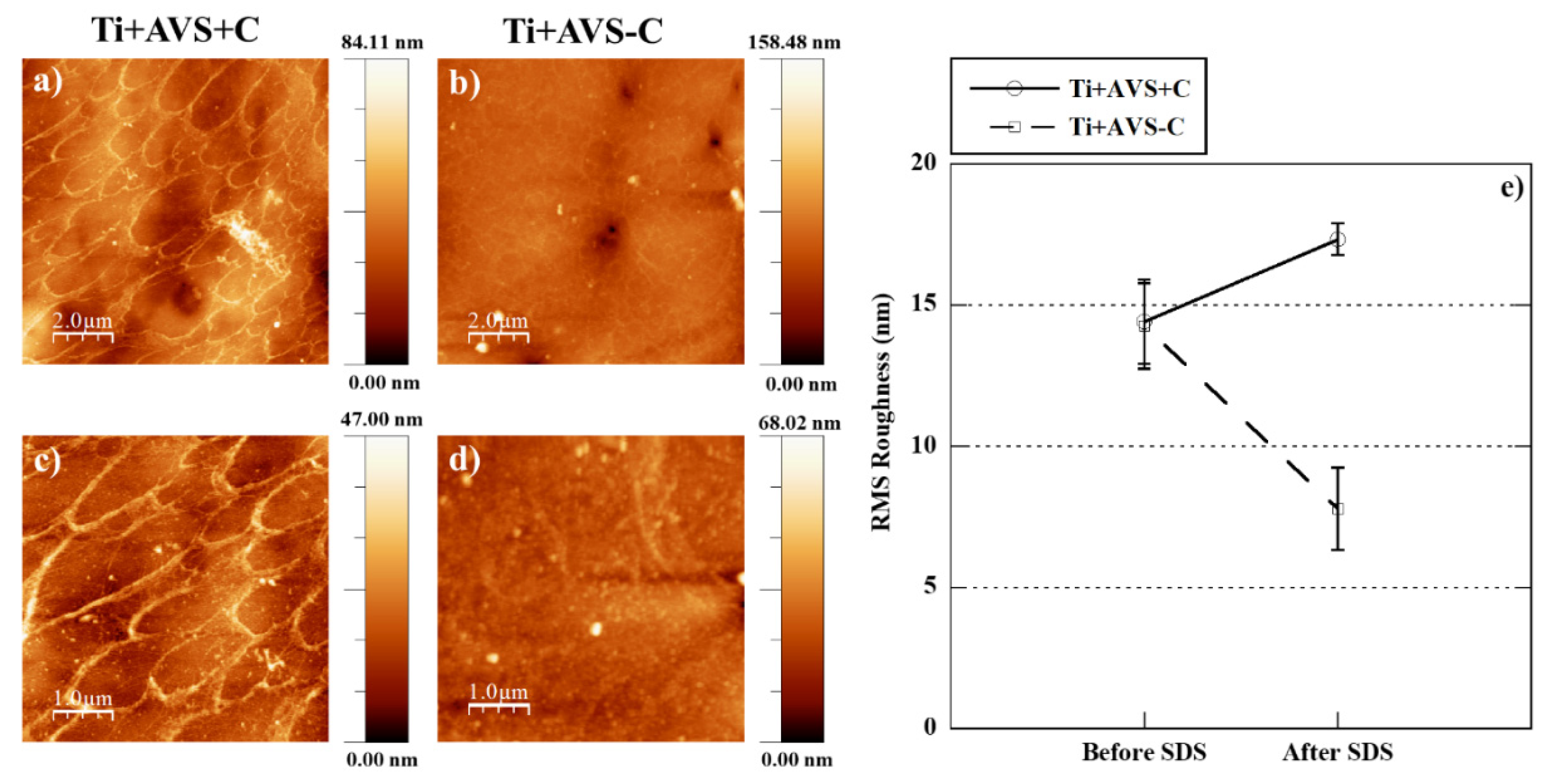

2.3. Stability testing

2.4. Characterization

2.4.1. Fluorescence microscopy

2.4.2. Atomic force microscopy

2.5. Cell cultures

2.5.1. Cell viability

2.5.2. Cell proliferation

2.5.3. Cell spreading

2.6. Statistical analysis

3. Results

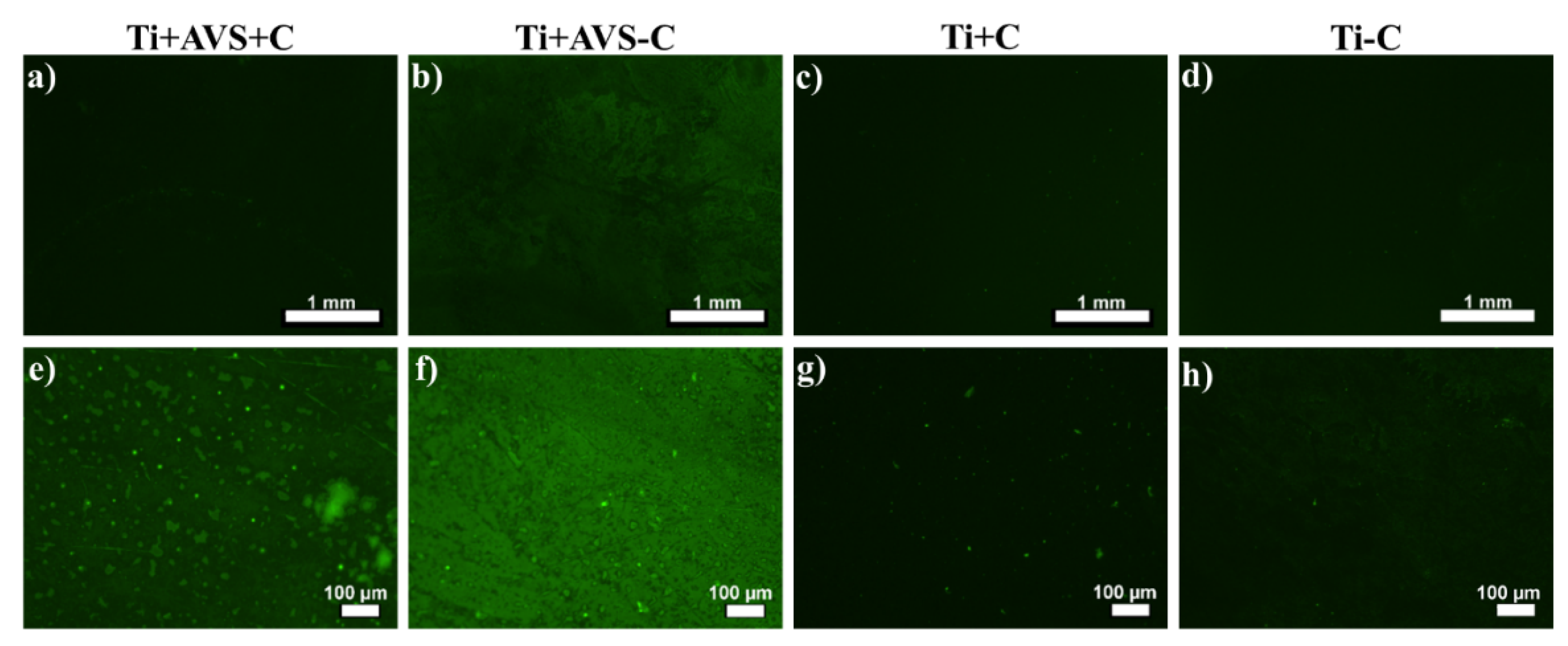

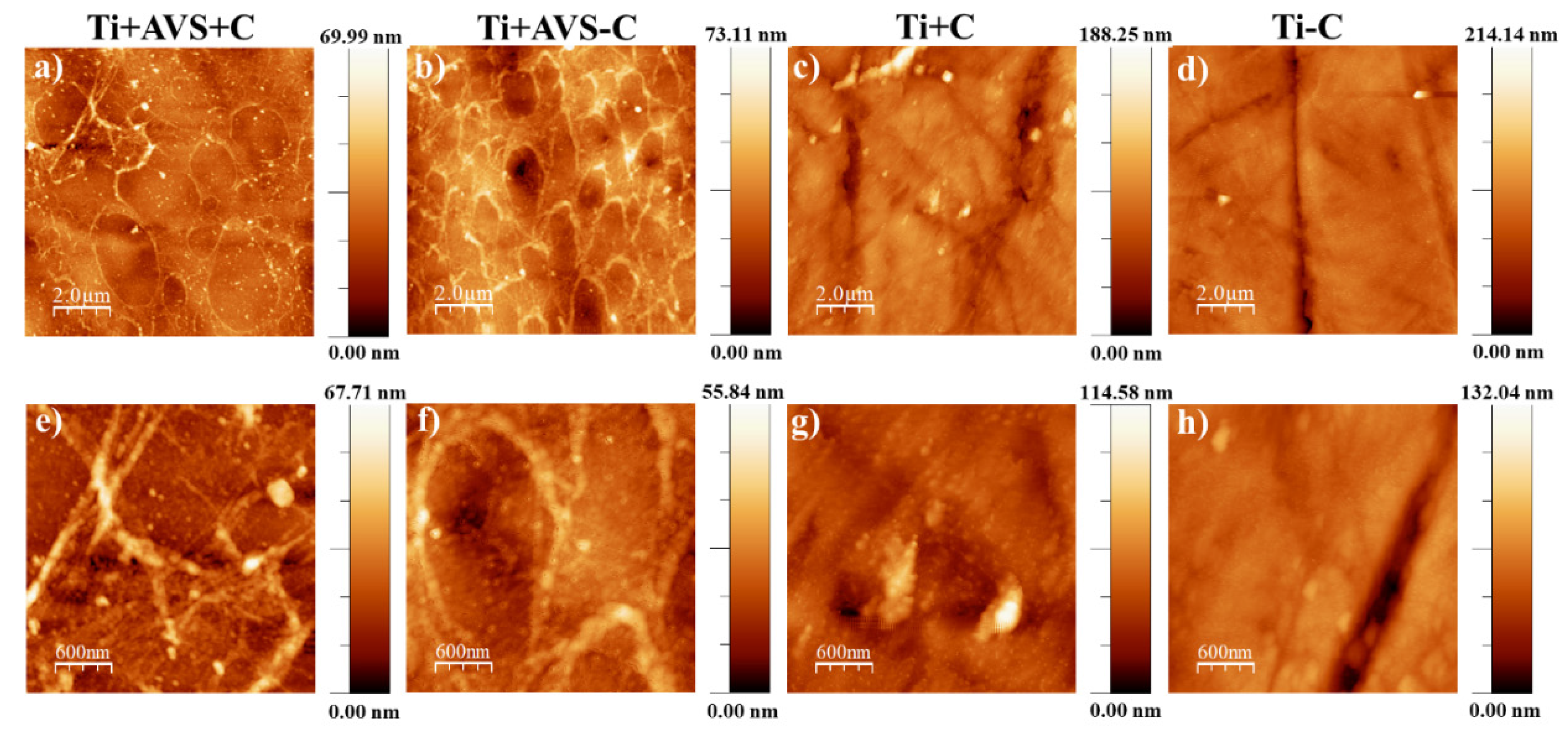

3.1. Evaluation of fibronectin attachment

3.1.1. Fluorescence microscopy

3.1.2. Atomic force microscopy

3.2. Biological assessment

3.2.1. Cell adhesion and proliferation

3.2.2. Cell morphology and spreading

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brunette, D.M.; Tengvall, P.; Textor, M.; Thomsen, P. Titanium in medicine: Material science, surface science, engineering, biological responses and medical applications; Springer Science & Business Media, 2012.

- Liu, X.; Chu, P.K.; Ding, C. Surface modification of titanium, titanium alloys, and related materials for biomedical applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2004, 47, 49–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Thouas, G.A. Metallic implant biomaterials. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2015, 87, 1–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geetha, M.; Singh, A.K.; Asokamani, R.; Gogia, A.K. Ti based biomaterials, the ultimate choice for orthopaedic implants – A review. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2009, 54, 397–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratner, B.D.; Hoffman, A.S.; Schoen, F.J.; Lemons, J.E. Biomaterials Science: An Introduction to Materials in Medicine; Elsevier Science, 2004.

- Coleman, D.L.; King, R.N.; Andrade, J.D. The foreign body reaction: A chronic inflammatory response. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1974, 8, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santavirta, S.; Gristina, A.; Konttinen, Y.T. Cemented versus cementless hip arthroplasty. A review of prosthetic biocompatibility. Acta Orthop. Scand. 1992, 63, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, R.; Garcia, A.J. Biomaterial strategies for engineering implants for enhanced osseointegration and bone repair. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2015, 94, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stich, T.; Alagboso, F.; Křenek, T.; Kovářík, T.; Alt, V.; Docheva, D. Implant-bone-interface: Reviewing the impact of titanium surface modifications on osteogenic processes in vitro and in vivo. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2022, 7, e10239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wroblewski, B.M. Current trends in revision of total hip arthroplasty. Int. Orthop. 1984, 8, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanawa, T. Titanium–Tissue Interface Reaction and Its Control With Surface Treatment. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-Pareja, N.; Salvagni, E.; Guillem-Marti, J.; Aparicio, C.; Ginebra, M. Collagen-functionalised titanium surfaces for biological sealing of dental implants: Effect of immobilisation process on fibroblasts response. Colloids Surf. B: Biointerfaces 2014, 122, 601–610.

- Kurth, D.G.; Bein, T. Thin Films of (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane on Aluminum Oxide and Gold Substrates. Langmuir 1995, 11, 3061–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trino, L.D.; Bronze-Uhle, E.S.; George, A.; Mathew, M.T.; Lisboa-Filho, P.N. Surface Physicochemical and Structural Analysis of Functionalized Titanium Dioxide Films. Colloids Surf. Physicochem. Eng. Aspects 2018, 546, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celesti, C.; Gervasi, T.; Cicero, N.; Giofrè, S.V.; Espro, C.; Piperopoulos, E.; Gabriele, B.; Mancuso, R.; Lo Vecchio, G.; Iannazzo, D. Titanium Surface Modification for Implantable Medical Devices with Anti-Bacterial Adhesion Properties. Materials 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, L.D.; Tripp, C.P. Reaction of (3-Aminopropyl)dimethylethoxysilane with Amine Catalysts on Silica Surfaces. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2000, 232, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arkles, B.; Steinmetz, J.R.; Zazyczny, J.; Mehta, P. Factors contributing to the stability of alkoxysilanes in aqueous solution. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 1992, 6, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, V.; Thomas, W.E.; Craig, D.W.; Krammer, A.; Baneyx, G. Structural insights into the mechanical regulation of molecular recognition sites. Trends Biotechnol. 2001, 19, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aota, S.; Nomizu, M.; Yamada, K.M. The short amino acid sequence Pro-His-Ser-Arg-Asn in human fibronectin enhances cell-adhesive function. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 24756–24761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphries, M.J.; Akiyama, S.K.; Komoriya, A.; Olden, K.; Yamada, K.M. Identification of an alternatively spliced site in human plasma fibronectin that mediates cell type-specific adhesion. J. Cell Biol. 1986, 103, 2637–2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komoriya, A.; Green, L.J.; Mervic, M.; Yamada, S.S.; Yamada, K.M.; Humphries, M.J. The minimal essential sequence for a major cell type-specific adhesion site (CS1) within the alternatively spliced type III connecting segment domain of fibronectin is leucine-aspartic acid-valine. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 15075–15079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, D.S.W.; Anseth, K.S. The effect on osteoblast function of colocalized RGD and PHSRN epitopes on PEG surfaces. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 5209–5220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, C.; Cheng, H.; Huang, C.; Li, H.; Ou, M.; Huang, J.; Khoo, K.; Yu, H.W.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Fibronectin in cell adhesion and migration via N-glycosylation. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 70653–70668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruoslahti, E. Fibronectin in cell adhesion and invasion. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1984, 3, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seitz, T.L.; Noonan, K.D.; Hench, L.L.; Noonan, N.E. Effect of fibronectin on the adhesion of an established cell line to a surface reactive biomaterial. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1982, 16, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dessau, W.; Sasse, J.; Timpl, R.; Jilek, F.; von der Mark, K. Synthesis and extracellular deposition of fibronectin in chondrocyte cultures. Response to the removal of extracellular cartilage matrix. J. Cell Biol. 1978, 79, 342–355. [Google Scholar]

- Rapuano, B.E.; MacDonald, D.E. Surface oxide net charge of a titanium alloy: Modulation of fibronectin-activated attachment and spreading of osteogenic cells. Colloids Surf. B: Biointerfaces 2011, 82, 95–103.

- Ku, Y.; Chung, C.; Jang, J. The effect of the surface modification of titanium using a recombinant fragment of fibronectin and vitronectin on cell behavior. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 5153–5157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Säuberlich, S.; Klee, D.; Richter, E.; Höcker, H.; Spiekermann, H. Cell culture tests for assessing the tolerance of soft tissue to variously modified titanium surfaces. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 1999, 10, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannas, M.; Denicolai, F.; Webb, L.X.; Gristina, A.G. Bioimplant surfaces: Binding of fibronectin and fibroblast adhesion. J. Orthop. Res. 1988, 6, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugita, Y.; Saruta, J.; Taniyama, T.; Kitajima, H.; Hirota, M.; Ikeda, T.; Ogawa, T. UV-Pre-Treated and Protein-Adsorbed Titanium Implants Exhibit Enhanced Osteoconductivity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadhab, S.; Bilem, I.; Guay-Bégin, A.; Chevallier, P.; Auger, F.A.; Ruel, J.; Pauthe, E.; Laroche, G. Fibronectin grafting to enhance skin sealing around transcutaneous titanium implant. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2021, 109, 2187–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugdee, K.; Shibata, Y.; Yamamichi, N.; Tsutsumi, H.; Yoshinari, M.; Abiko, Y.; Hayakawa, T. Gene expression of MC3T3-E1 cells on fibronectin-immobilized titanium using tresyl chloride activation technique. Dent. Mater. J. 2007, 26, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, T.; Yoshida, E.; Yoshimura, Y.; Uo, M.; Yoshinari, M. MC3T3-E1 Cells on Titanium Surfaces with Nanometer Smoothness and Fibronectin Immobilization. Int. J. Biomater. 2012, 2012, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, M.T.; Reuther, H.; Maitz, M.F. Native extracellular matrix coating on Ti surfaces. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2003, 66A, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-Palma, R.J.; Manso, M.; Pérez-Rigueiro, J.; García-Ruiz, J.P.; Martínez-Duart, J.M. Surface biofunctionalization of materials by amine groups. J. Mater. Res. 2004, 19, 2415–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvanian, P.; Arroyo-Hernández, M.; Ramos, M.; Daza, R.; Elices, M.; Guinea, G.V.; Pérez-Rigueiro, J. Development of a versatile procedure for the biofunctionalization of Ti-6Al-4V implants. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 387, 652–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulouin, L.; Gallet, O.; Rouahi, M.; Imhoff, J. Plasma Fibronectin: Three Steps to Purification and Stability. Protein Expr. Purif. 1999, 17, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvanian, P.; Daza, R.; López, P.A.; Ramos, M.; González-Nieto, D.; Elices, M.; Guinea, G.V.; Pérez-Rigueiro, J. Enhanced Biological Response of AVS-Functionalized Ti-6Al-4V Alloy through Covalent Immobilization of Collagen. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, C.; Leroy-Dudal, J.; Patel, S.; Gallet, O.; Pauthe, E. Fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled human plasma fibronectin in extracellular matrix remodeling. Anal. Biochem. 2008, 372, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horcas, I.; Fernández, R.; Gómez-Rodríguez, J.M.; Colchero, J.; Gómez-Herrero, J.; Baro, A.M. WSXM: A software for scanning probe microscopy and a tool for nanotechnology. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2007, 78, 013705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo-Hernandez, M.; Martin-Palma, R.J.; Perez-Rigueiro, J.; Garcia-Ruiz, J.P.; Garcia-Fierro, J.L.; Martinez-Duart, J.M. Biofunctionalization of surfaces of nanostructured porous silicon. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2003, 23, 697–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tooney, N.M.; Mosesson, M.W.; Amrani, D.L.; Hainfeld, J.F.; Wall, J.S. Solution and surface effects on plasma fibronectin structure. J. Cell Biol. 1983, 97, 1686–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinner, M.; Gerlach, J.; Ensinger, W. Formation of titanium oxide films on titanium and Ti6Al4V by O2-plasma immersion ion implantation. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2000, 132, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Sánchez, J.; Gallardo-Moreno, A.M.; Bruque, J.M.; González-Martín, M.L. Adsorption of human fibrinogen and albumin onto hydrophobic and hydrophilic Ti6Al4V powder. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 376, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, D.E.; Rapuano, B.E.; Schniepp, H.C. Surface Oxide Net Charge of a Titanium Alloy; Comparison Between Effects of Treatment With Heat or Radiofrequency Plasma Glow Discharge. Colloids Surf. B: Biointerfaces 2010, 82, 173–181.

- Parisi, L.; Toffoli, A.; Ghezzi, B.; Mozzoni, B.; Lumetti, S.; Macaluso, G.M. A glance on the role of fibronectin in controlling cell response at biomaterial interface. Jpn. Dent. Sci. Rev. 2020, 56, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brighton, C.T.; Albelda, S.M. Identification of integrin cell-substratum adhesion receptors on cultured rat bone cells. J. Orthop. Res. 1992, 10, 766–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, S.; Katz, B.Z.; Lafrenie, R.M.; Yamada, K.M. Fibronectin and integrins in cell adhesion, signaling, and morphogenesis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1998, 857, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersel, U.; Dahmen, C.; Kessler, H. RGD modified polymers: Biomaterials for stimulated cell adhesion and beyond. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 4385–4415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver-Cervelló, L.; Martin-Gómez, H.; Mas-Moruno, C. New trends in the development of multifunctional peptides to functionalize biomaterials. J. Pep. Sci. 2022, 28, e3335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straface, E.; Natalini, B.; Monti, D.; Franceschi, C.; Schettini, G.; Bisaglia, M.; Fumelli, C.; Pincelli, C.; Pellicciari, R.; Malorni, W. C3-fullero-tris-methanodicarboxylic acid protects epithelial cells from radiation-induced anoikia by influencing cell adhesion ability. FEBS Lett. 1999, 454, 335–340. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, C.H.; Lhoest, J.B.; Castner, D.G.; McFarland, C.D.; Healy, K.E. Surfaces designed to control the projected area and shape of individual cells. J. Biomech. Eng. 1999, 121, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.S.; Mrksich, M.; Huang, S.; Whitesides, G.M.; Ingber, D.E. Geometric control of cell life and death. Science 1997, 276, 1425–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Chen, C.S.; Ingber, D.E. Control of cyclin D1, p27(Kip1), and cell cycle progression in human capillary endothelial cells by cell shape and cytoskeletal tension. Mol. Biol. Cell 1998, 9, 3179–3193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avraham, H.K.; Lee, T.H.; Koh, Y.; Kim, T.A.; Jiang, S.; Sussman, M.; Samarel, A.M.; Avraham, S. Vascular endothelial growth factor regulates focal adhesion assembly in human brain microvascular endothelial cells through activation of the focal adhesion kinase and related adhesion focal tyrosine kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 36661–36668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwivedi, A.; Sala-Newby, G.B.; George, S.J. Regulation of cell-matrix contacts and beta-catenin signaling in VSMC by integrin-linked kinase: Implications for intimal thickening. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2008, 103, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamir, E.; Geiger, B. Molecular complexity and dynamics of cell-matrix adhesions. J. Cell. Sci. 2001, 114, 3583–3590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khetan, J.; Shahinuzzaman, M.; Barua, S.; Barua, D. Quantitative Analysis of the Correlation between Cell Size and Cellular Uptake of Particles. Biophys. J. 2019, 116, 347–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assoian, R.K.; Klein, E.A. Growth control by intracellular tension and extracellular stiffness. Trends. Cell. Biol. 2008, 18, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacakova, L.; Filova, E.; Parizek, M.; Ruml, T.; Svorcik, V. Modulation of cell adhesion, proliferation and differentiation on materials designed for body implants. Biotechnol. Adv. 2011, 29, 739–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingber, D.E.; Prusty, D.; Sun, Z.; Betensky, H.; Wang, N. Cell shape, cytoskeletal mechanics, and cell cycle control in angiogenesis. J. Biomech. 1995, 28, 1471–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, L.M.; Smith, M.A.; Jensen, C.C.; Yoshigi, M.; Blankman, E.; Ullman, K.S.; Beckerle, M.C. Mechanical stress triggers nuclear remodeling and the formation of transmembrane actin nuclear lines with associated nuclear pore complexes. Mol. Biol. Cell 2020, 31, 1774–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Details |

|---|---|

| Ti+AVS+C | AVS-functionalized Ti-6Al-4V incubated with fibronectin and EDC/NHS cross-linkers |

| Ti+AVS-C | AVS-functionalized Ti-6Al-4V incubated with fibronectin solution without addition of EDC/NHS cross-linkers |

| Ti+C | Bare Ti-6Al-4V incubated with fibronectin solution and EDC/NHS cross-linkers |

| Ti-C | Bare Ti-6Al-4V incubated with fibronectin solution without addition of EDC/NHS cross-linkers |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).