Submitted:

25 May 2023

Posted:

26 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Cell lines and cell culture

2.3. RNAi and transfection

2.4. Immunoblotting and antibodies

2.5. Immunofluorescence microscopy

2.6. Immunoprecipitation analysis

3. Results

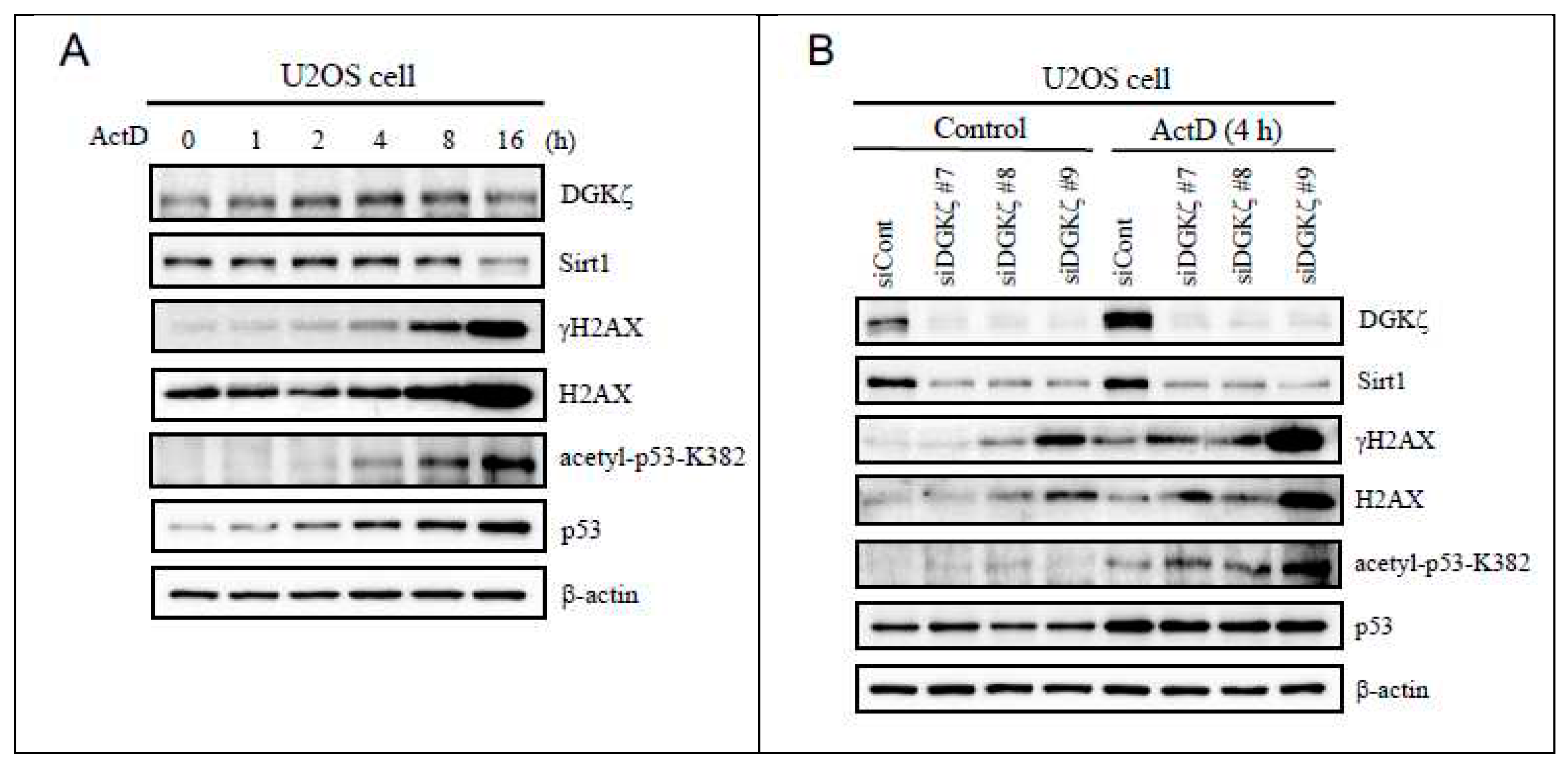

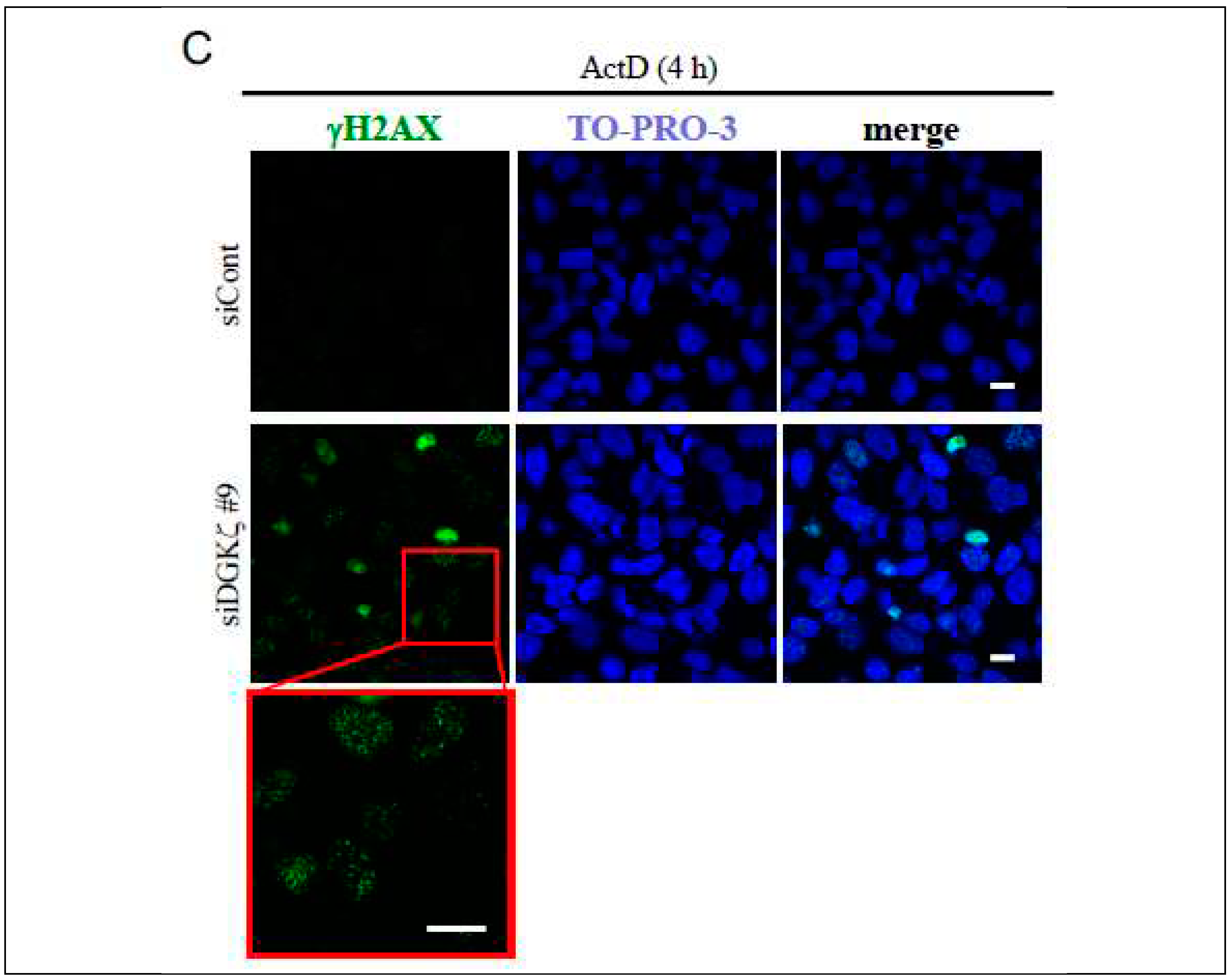

3.1. Depletion of DGK enhances DNA double strand break

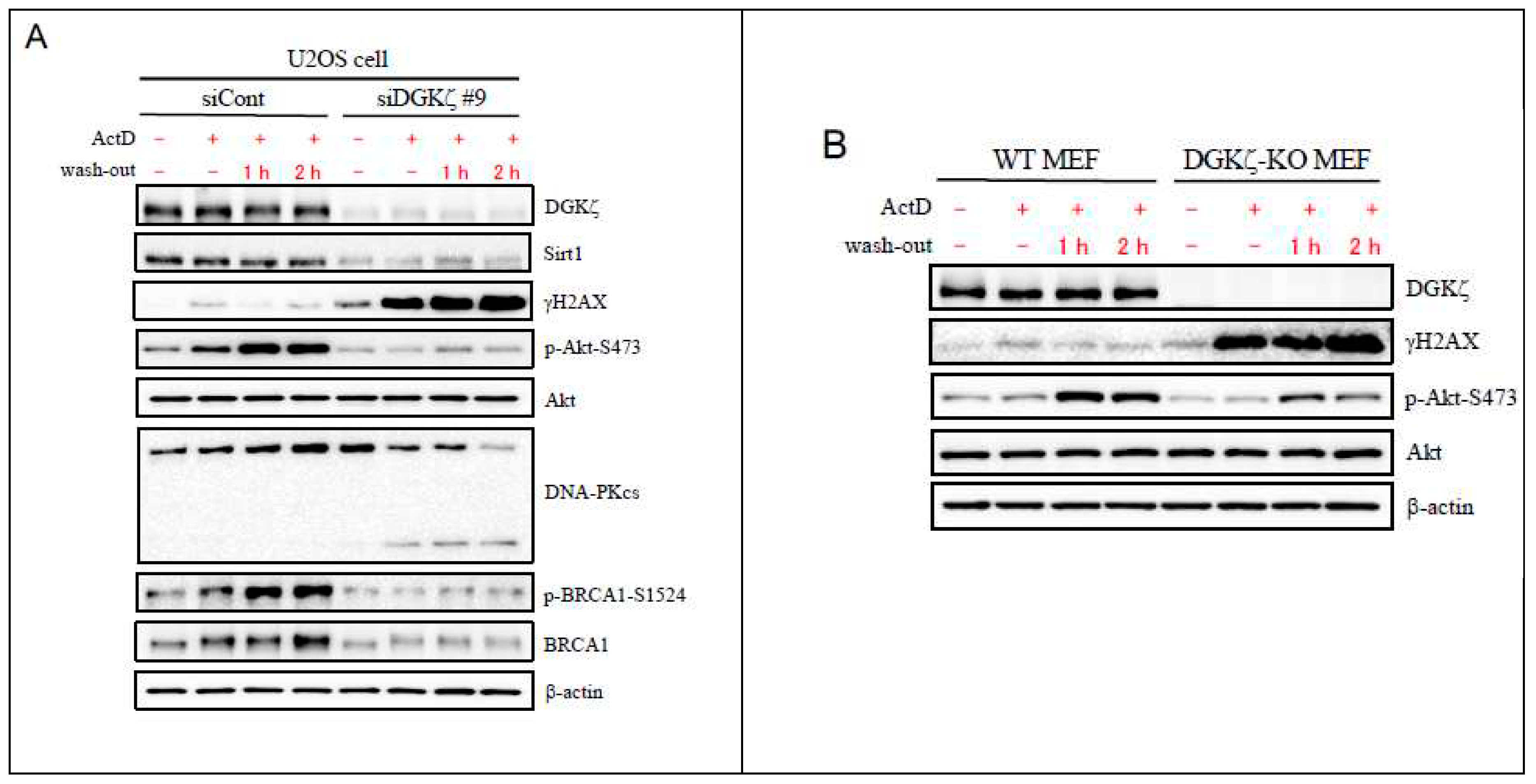

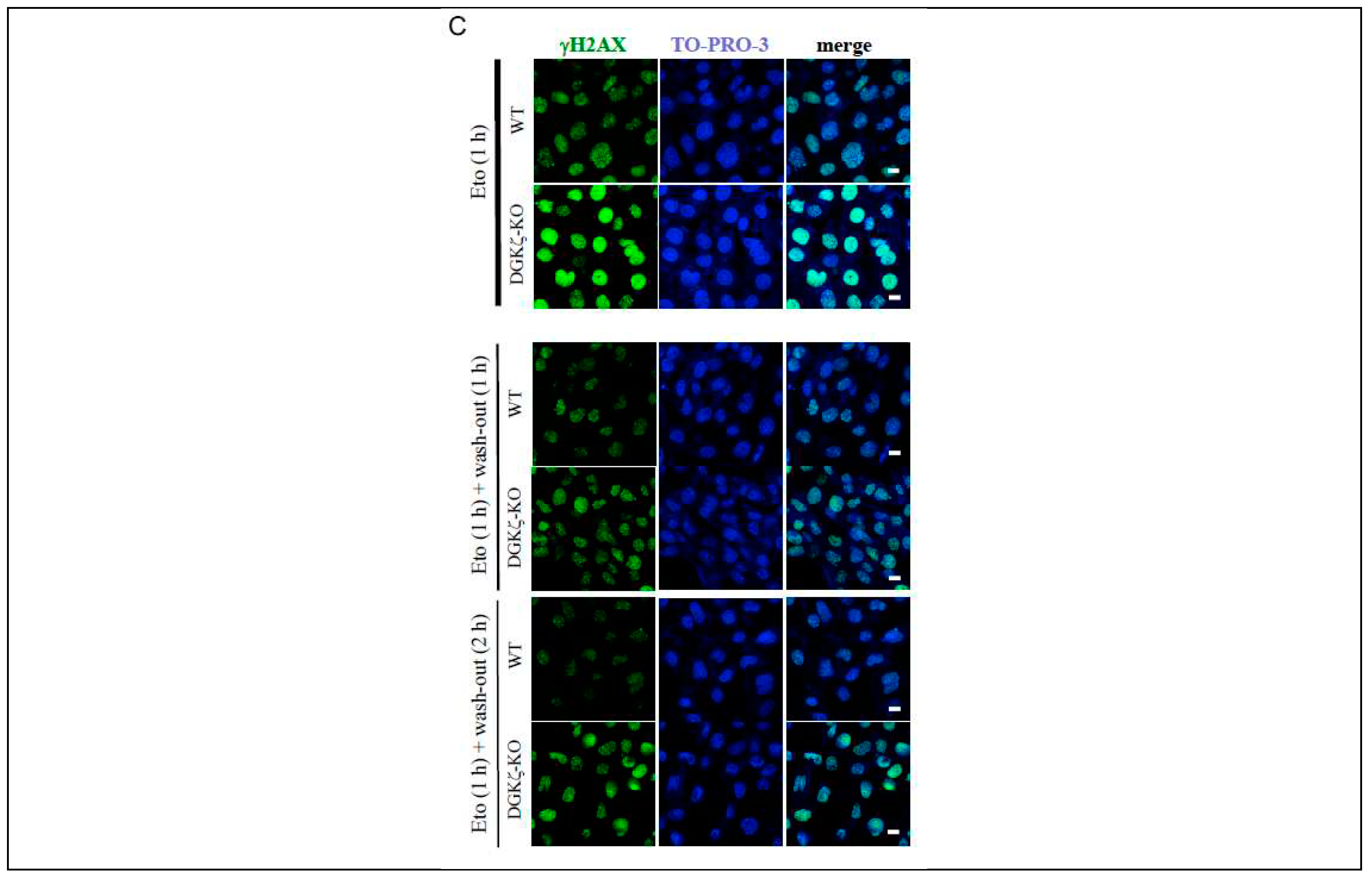

3.2. DNA repair is delayed in DGK-depleted cells

3.3. DGK depletion attenuates BRCA1-mediated DNA repair mechanism.

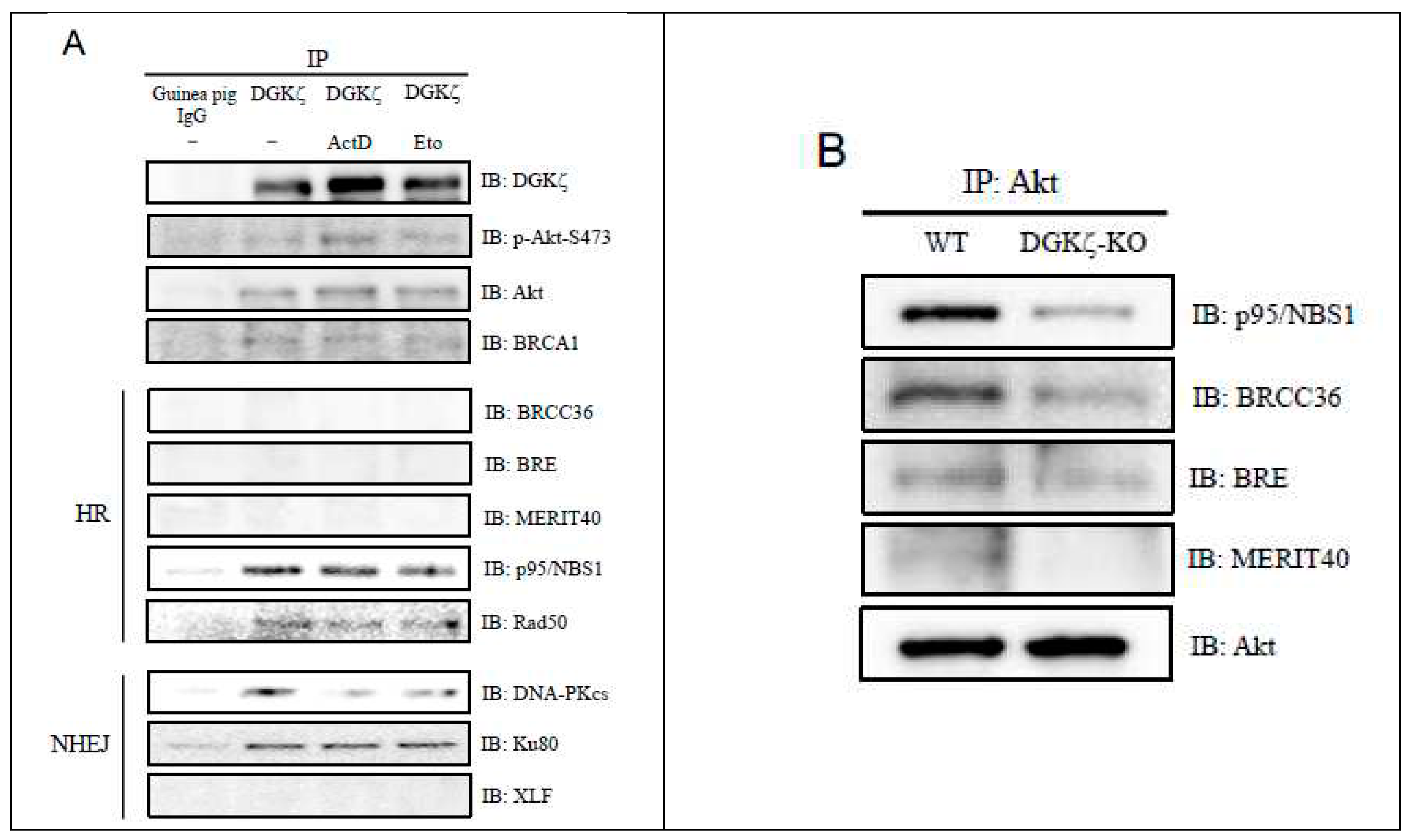

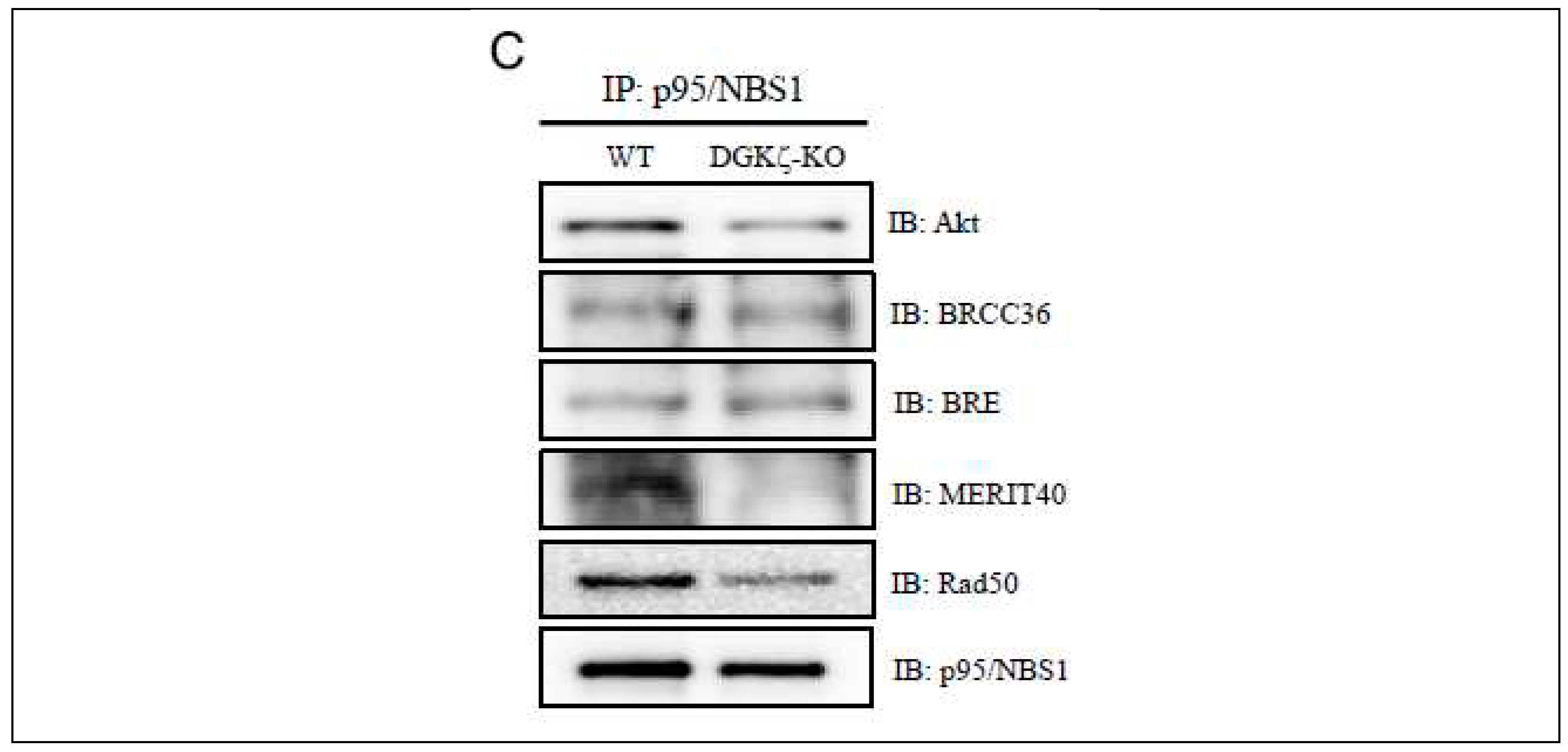

3.4. DGKζ co-immunoprecipitates with DNA damage-repair proteins.

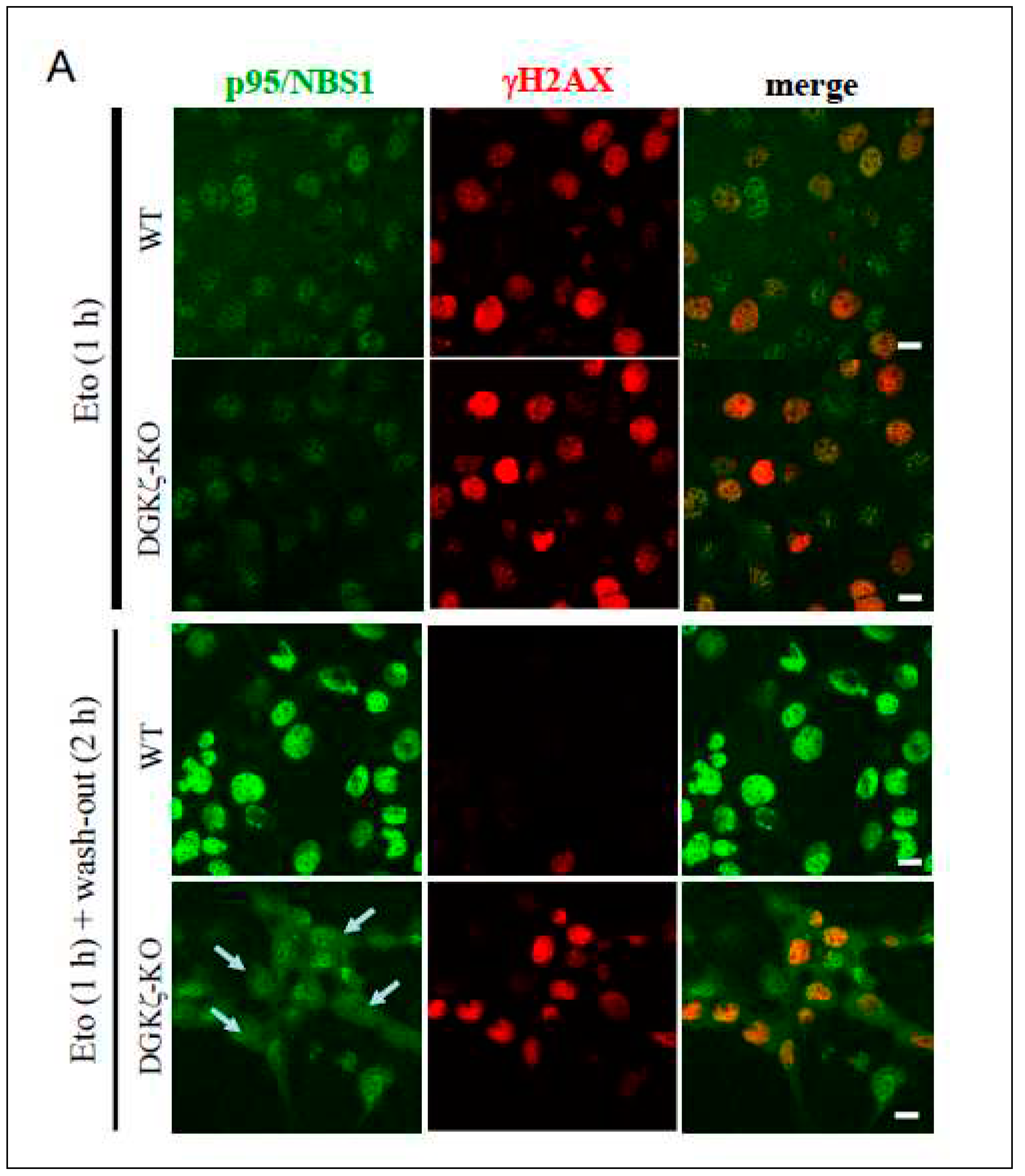

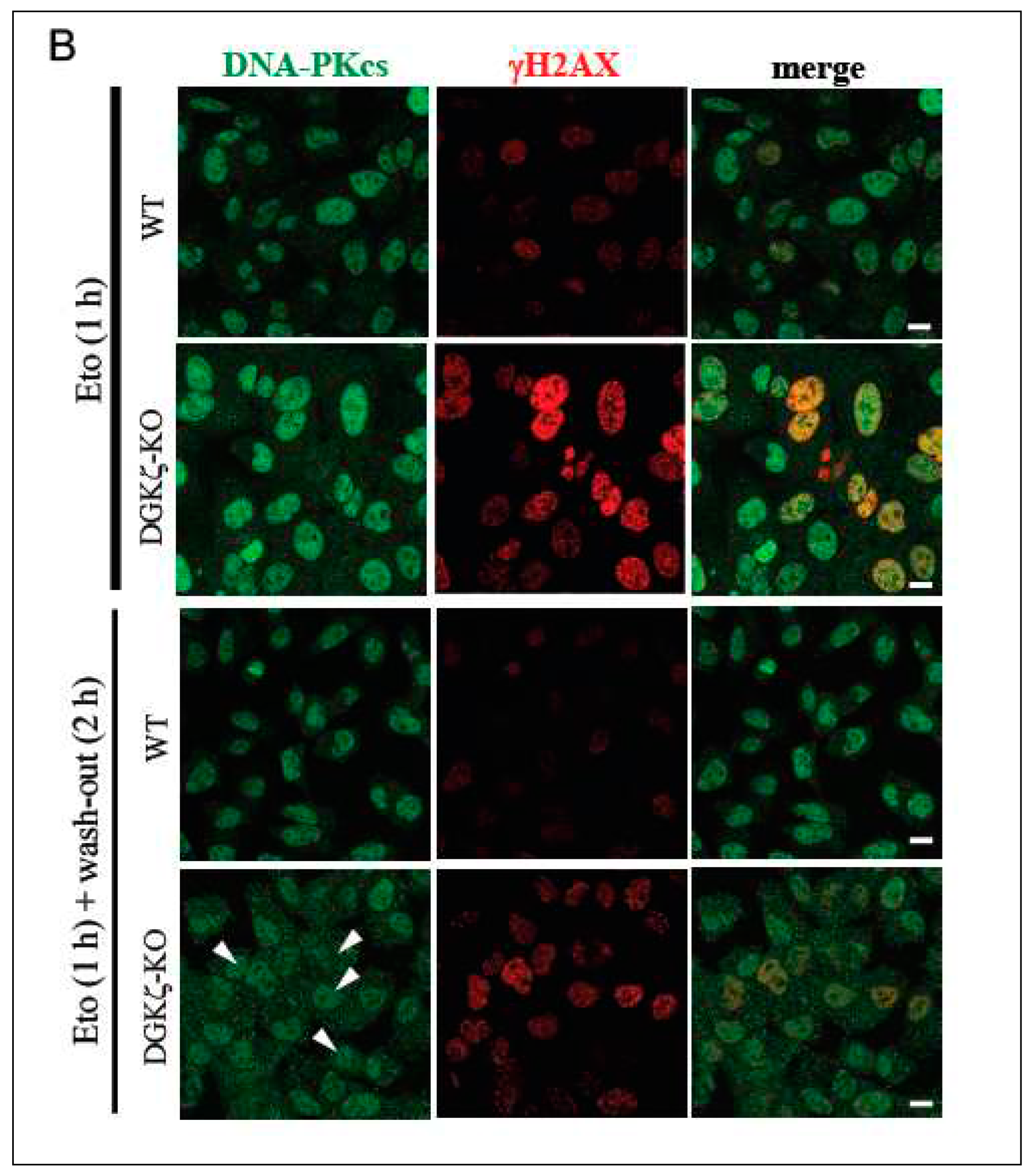

3.5. Depletion of DGK induces cytoplasmic retention of p95/NBS1 and DNA-PKcs during DNA repair

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chang, H. H. Y.; Pannunzio, N. R.; Adachi, N.; Lieber, M. R. Non-homologous DNA end joining and alternative pathways to double-strand break repair. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 495–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tergaonkar, V.; Pando, M.; Vafa, O.; Wahl, G.; Verma, I. p53 stabilization is decreased upon NFkappaB activation: a role for NFkappaB in acquisition of resistance to chemotherapy. Cancer Cell 2002, 1, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanoh, H.; Yamada, K.; Sakane, F. Diacylglycerol kinase: a key modulator of signal transduction? Trends Biochem. Sci. 1990, 15, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakane, F.; Imai, S.; Kai, M.; Yasuda, S.; Kanoh, H. Diacylglycerol kinases: why so many of them? Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2007, 1771, 793–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goto, K.; Hozumi, Y.; Nakano, T.; Saino, S. S.; Kondo, H. Cell biology and pathophysiology of the diacylglycerol kinase family: morphological aspects in tissues and organs. Int. Rev. Cytol. 2007, 264, 25–63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Topham, M. K.; Epand, R. M. Mammalian diacylglycerol kinases: molecular interactions and biological functions of selected isoforms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009, 1790, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, T.; Nakano, T.; Hozumi, Y.; Martelli, A. M.; Goto, K. Regulation of p53 and NF-κB transactivation activities by DGKζ in catalytic activity-dependent and -independent manners. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2021, 1868, 118953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, K.; Kondo, H. A 104-kDa diacylglycerol kinase containing ankyrin-like repeats localizes in the cell nucleus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996, 93, 11196–11201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hozumi, Y.; Ito, T.; Nakano, T.; Nakagawa, T.; Aoyagi, M.; Kondo, H.; Goto, K. Nuclear localization of diacylglycerol kinase zeta in neurons. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2003, 18, 1448–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, K.; Tanaka, T.; Nakano, T.; Okada, M.; Hozumi, Y.; Topham, M. K.; Martelli, A. M. DGKζ under stress conditions: “to be nuclear or cytoplasmic, that is the question”. Adv. Biol. Regul. 2014, 54, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Okada, M.; Hozumi, Y.; Tachibana, K.; Kitanaka, C.; Hamamoto, Y.; Martelli, A. M.; Topham, M. K.; Iino, M.; Goto, K. Cytoplasmic localization of DGKζ exerts a protective effect against p53-mediated cytotoxicity. J. Cell Sci. 2013, 126 Pt 13, 2785–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, M.; Hozumi, Y.; Tanaka, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Yanagida, M.; Araki, Y.; Evangelisti, C.; Yagisawa, H.; Topham, M. K.; Martelli, A. M.; et al. DGKζ is degraded through the cytoplasmic ubiquitin-proteasome system under excitotoxic conditions, which causes neuronal apoptosis because of aberrant cell cycle reentry. Cell. Signal. 2012, 24, 1573–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, D. R.; Kroemer, G. Cytoplasmic functions of the tumour suppressor p53. Nature 2009, 458, 1127–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchenko, N. D.; Wolff, S.; Erster, S.; Becker, K.; Moll, U. M. Monoubiquitylation promotes mitochondrial p53 translocation. Embo J. 2007, 26, 923–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, T.; Iseki, K.; Tanaka, K.; Nakano, T.; Iino, M.; Goto, K. DGKζ ablation engenders upregulation of p53 level in the spleen upon whole-body ionizing radiation. Adv. Biol. Regul. 2018, 67, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fei, P.; El-Deiry, W. S. P53 and radiation responses. Oncogene 2003, 22, 5774–5783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Ojima, M.; Kodama, S.; Watanabe, M. Radiation-induced DNA damage and delayed induced genomic instability. Oncogene 2003, 22, 6988–6993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, W. G.; Kastan, M. B. DNA strand breaks: the DNA template alterations that trigger p53-dependent DNA damage response pathways. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994, 14, 1815–1823. [Google Scholar]

- Vousden, K. H.; Prives, C. Blinded by the Light: The Growing Complexity of p53. Cell 2009, 137, 413–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, R.; Tanaka, T.; Hozumi, Y.; Nakano, T.; Okada, M.; Topham, M. K.; Iino, M.; Goto, K. Downregulation of diacylglycerol kinase ζ enhances activation of cytokine-induced NF-κB signaling pathway. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1853, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habraken, Y.; Piette, J. NF-kappaB activation by double-strand breaks. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2006, 72, 1132–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okada, M.; Hozumi, Y.; Ichimura, T.; Tanaka, T.; Hasegawa, H.; Yamamoto, M.; Takahashi, N.; Iseki, K.; Yagisawa, H.; Shinkawa, T.; et al. Interaction of nucleosome assembly proteins abolishes nuclear localization of DGKζ by attenuating its association with importins. Exp. Cell Res. 2011, 317, 2853–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karpinich, N. O.; Tafani, M.; Rothman, R. J.; Russo, M. A.; Farber, J. L. The course of etoposide-induced apoptosis from damage to DNA and p53 activation to mitochondrial release of cytochrome c. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 16547–16552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porcedda, P.; Turinetto, V.; Lantelme, E.; Fontanella, E.; Chrzanowska, K.; Ragona, R.; De Marchi, M.; Delia, D.; Giachino, C. Impaired elimination of DNA double-strand break-containing lymphocytes in ataxia telangiectasia and Nijmegen breakage syndrome. DNA Repair (Amst) 2006, 5, 904–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choong, M. L.; Yang, H.; Lee, M. A.; Lane, D. P. Specific activation of the p53 pathway by low dose actinomycin D: a new route to p53 based cyclotherapy. Cell Cycle 2009, 8, 2810–2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedelnikova, O. A.; Rogakou, E. P.; Panyutin, I. G.; Bonner, W. M. Quantitative detection of (125)IdU-induced DNA double-strand breaks with gamma-H2AX antibody. Radiat. Res. 2002, 158, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaguchi, K.; Herrera, J. E.; Saito, S.; Miki, T.; Bustin, M.; Vassilev, A.; Anderson, C. W.; Appella, E. DNA damage activates p53 through a phosphorylation-acetylation cascade. Genes Dev. 1998, 12, 2831–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akimoto, R.; Tanaka, T.; Nakano, T.; Hozumi, Y.; Kawamae, K.; Goto, K. DGKζ depletion attenuates HIF-1α induction and SIRT1 expression, but enhances TAK1-mediated AMPKα phosphorylation under hypoxia. Cell. Signal. 2020, 71, 109618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H. L.; Mostoslavsky, R.; Saito, S.; Manis, J. P.; Gu, Y.; Patel, P.; Bronson, R.; Appella, E.; Alt, F. W.; Chua, K. F. Developmental defects and p53 hyperacetylation in Sir2 homolog (SIRT1)-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sc.i U.S.A. 2003, 100, 10794–10799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogakou, E. P.; Boon, C.; Redon, C.; Bonner, W. M. Megabase chromatin domains involved in DNA double-strand breaks in vivo. J. Cell Biol. 1999, 146, 905–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tebbs, R. S.; Zhao, Y.; Tucker, J. D.; Scheerer, J. B.; Siciliano, M. J.; Hwang, M.; Liu, N.; Legerski, R. J.; Thompson, L. H. Correction of chromosomal instability and sensitivity to diverse mutagens by a cloned cDNA of the XRCC3 DNA repair gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1995, 92, 6354–6358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iliakis, G.; Wang, H.; Perrault, A. R.; Boecker, W.; Rosidi, B.; Windhofer, F.; Wu, W.; Guan, J.; Terzoudi, G.; Pantelias, G. Mechanisms of DNA double strand break repair and chromosome aberration formation. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2004, 104, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toulany, M.; Lee, K. J.; Fattah, K. R.; Lin, Y. F.; Fehrenbacher, B.; Schaller, M.; Chen, B. P.; Chen, D. J.; Rodemann, H. P. Akt promotes post-irradiation survival of human tumor cells through initiation, progression, and termination of DNA-PKcs-dependent DNA double-strand break repair. Mol. Cancer Res. 2012, 10, 945–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozulic, L.; Surucu, B.; Hynx, D.; Hemmings, B. A. PKBalpha/Akt1 acts downstream of DNA-PK in the DNA double-strand break response and promotes survival. Mol. Cell 2008, 30, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winograd-Katz, S. E.; Levitzki, A. Cisplatin induces PKB/Akt activation and p38(MAPK) phosphorylation of the EGF receptor. Oncogene 2006, 25, 7381–7390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suwa, A.; Hirakata, M.; Takeda, Y.; Jesch, S. A.; Mimori, T.; Hardin, J. A. DNA-dependent protein kinase (Ku protein-p350 complex) assembles on double-stranded DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994, 91, 6904–6908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, A. C.; Lyons, T. R.; Young, C. D.; Hansen, K. C.; Anderson, S. M.; Holt, J. T. AKT regulates BRCA1 stability in response to hormone signaling. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2010, 319, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouchi, T. BRCA1 phosphorylation: biological consequences. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2006, 5, 470–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. H.; Mand, M. R.; Deshpande, R. A.; Kinoshita, E.; Yang, S. H.; Wyman, C.; Paull, T. T. Ataxia telangiectasia-mutated (ATM) kinase activity is regulated by ATP-driven conformational changes in the Mre11/Rad50/Nbs1 (MRN) complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 12840–12851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hari, F. J.; Spycher, C.; Jungmichel, S.; Pavic, L.; Stucki, M. A divalent FHA/BRCT-binding mechanism couples the MRE11-RAD50-NBS1 complex to damaged chromatin. EMBO Rep. 2010, 11, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciccia, A.; Elledge, S. J. The DNA damage response: making it safe to play with knives. Mol. Cell 2010, 40, 179–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B. B.; Elledge, S. J. The DNA damage response: putting checkpoints in perspective. Nature 2000, 408, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldecott, K. W. Single-strand break repair and genetic disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008, 9, 619–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, J.; Juhn, K.; Lee, H.; Kim, S. H.; Min, B. H.; Lee, K. M.; Cho, M. H.; Park, G. H.; Lee, K. H. SIRT1 promotes DNA repair activity and deacetylation of Ku70. Exp. Mol. Med. 2007, 39, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, R. D.; Quinn, J. E.; Johnston, P. G.; Harkin, D. P. BRCA1: mechanisms of inactivation and implications for management of patients. Lancet 2002, 360, 1007–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, R. D.; Quinn, J. E.; Mullan, P. B.; Johnston, P. G.; Harkin, D. P. The role of BRCA1 in the cellular response to chemotherapy. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2004, 96, 1659–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).