1. Introduction

The introduction should briefly place the study in a broad context and highlight why it is important. It should define the purpose of the work and its significance. The current state of the research field should be carefully reviewed and key publications cited. Please highlight controversial and diverging hypotheses when necessary. Finally, briefly mention the main aim of the work and highlight the principal conclusions. As far as possible, please keep the introduction comprehensible to scientists outside your particular field of research. References should be numbered in order of appearance and indicated by a numeral or numerals in square brackets—e.g., [

1] or [

2,

3], or [

4,

5,

6]. See the end of the document for further details on references.

Breast cancer is the most prevalent cancer and the second cause of cancer-related deaths among women. Early- diagnosis of this disease can significantly help the treatment process. Unfortunately, developed countries have a higher infection rate [

1]. Screening significantly impacts early diagnosis and decreases the breast cancer mortality rate by 25% [

2]. Mammography is an early diagnosis method of breast cancer before it becomes a palpable mass [

3,

4].

With developments in machine learning and artificial intelligence, many researchers have drawn attention to developing computer-aided systems (CADe, CADx) for breast cancer diagnosis. These systems assist physicians in the challenging and tedious task of interpreting medical images, preventing decisions from being influenced by errors, and enhancing the discovery of subtle but significant variations in tissues and anatomical structures, which are essential for the timely treatment of diseases [

5]. Deep learning models, especially Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), have significantly advanced computer vision, including medical image analysis [

6,

7,

8]. The reason for this success is the capability to directly learn hierarchical representations of features from data rather than utilizing handcrafted properties in terms of domain-specific knowledge.

This work presents state-of-the-art breast cancer CAD systems studies based on deep learning in mammography images. To meet the study's objective, we tried to respond to the research questions as follows:

What are the breast cancer screening methods, and what are public databases for mammography images applied in CAD systems?

What steps are in developing CAD systems for breast cancer detection?

What are the deep learning methods used to develop CAD systems?

What measurements are used to evaluate the CAD system’s performance?

What are CAD systems' future directions, limitations, and challenges for breast cancer diagnosis?

The paper is structured as follows. The most popular breast imaging modalities are presented in

Section 2, then

Section 3 gives public mammography databases available. We will have a famous CNN architecture in section 4, an introduction to the primary and new components of deep learning. In

Section 4, we briefly review the CAD systems. The current literature for segmentation of breast mass in mammography is presented. Then classification of breast mass literature is presented. We emphasize the strengths and limitations of studies.

Section 6 gives the assessment metrics for breast cancer CAD systems. Then, we discuss future trends and remaining problems in breast cancer in

Section 7. Finally, we provide a conclusion in section 8.

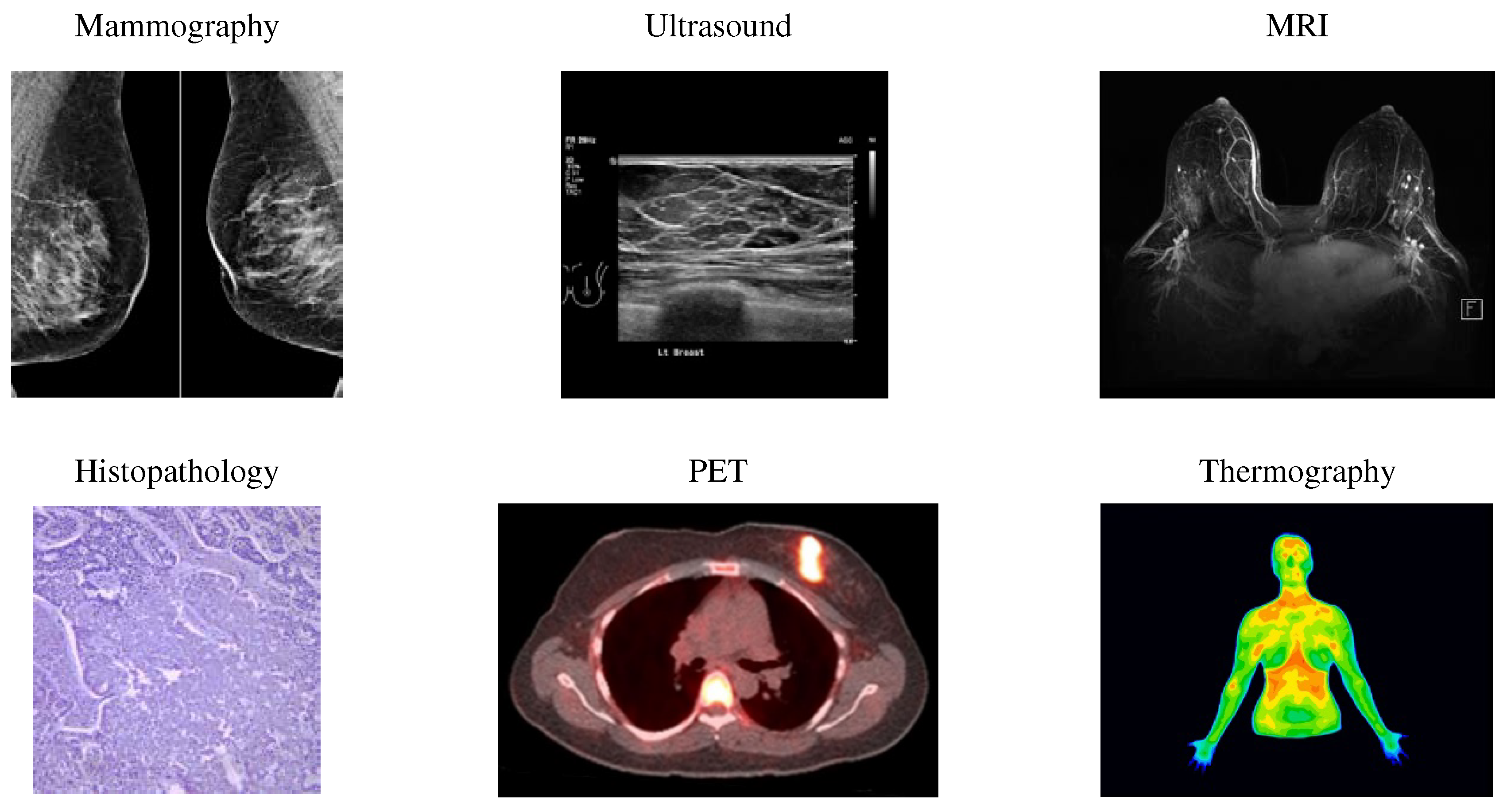

2. Imaging Modalities

By screening, abnormalities in the breast can detect in the early stages. Screening looks for signs of disease before symptoms appear. Various imaging modalities utilize for breast cancer screening, such as ultrasound, mammography, Positron Emission Tomography (PET), Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), histopathology, and thermography (

Figure 1).

Table 1 summarizes the benefits and drawbacks of different imaging modalities.

One of the most common breast cancer screening tests is mammography, using uses X-rays to image the breast and can identify and diagnose tiny and unpalpable masses. Mammography can detect abnormal cells around the breast duct, known as Ductal Carcinoma in Situ (DCIS). Factors like the skill and experience of the radiologist, tumor size, and breast tissue density can affect mammography sensitivity. Mammography is unsuitable for dense breasts because both dense tissue and breast abnormalities, such as calcification and tumors, are white in mammography images [

9].

Ultrasound is a painless procedure using high-frequency sound waves for black-and-white breast tissue and structure imaging. This imaging detects even the most minor abnormalities in dense breasts and helps to detect a solid mass or fluid-filled cysts that are difficult to see on a mammogram. Furthermore, ultrasound can direct the biopsy operation at the assembly area. Ultrasound is available extensively and relatively easy to perform while not giving radiation to a person. It is also less expensive than other imaging options.

MRI use for women with a higher risk of breast cancer. MRI is a method that uses magnets, a computer, and radio waves to form detailed images of breast tissue. Since X-rays do not operate in this method, the patient will not expose to radiation. MRI can detect some cancers that do not observe on mammograms; it possibly finds things that are not cancer (or false positives).

Histopathology is the microscopic examination of whole tissue samples. A histopathologist can view potentially cancerous or atypical tissues and assist other medical specialists in making diagnoses or assessing the effectiveness of treatments.

In a positron emission tomography scan as an imaging test, a radioactive drug (tracer) searches for the potential spread of breast cancer. Hence, it can recognize areas of cancer possibly not detected by a CT scan or MRI.

One of the natural indicators of breast tissue abnormalities is the temperature change in the cancerous area. Breast thermography is a non-invasive technique that detects early signs of breast cancer regarding blood circulation and body temperature changes. In the breast thermography screening method, infrared rays display a thermal image of the breast tissues.

3. Public Mammography Datasets

Mammography is the most popular screening test for breast cancer [

10]. Various datasets are available to the public that differs in size, resolution, image format, image type, and abnormalities included in the database.

Table 2 presents the detailed specifications of various public mammography databases.

The digital mammography database of the Mammographic Image Analysis Society (MIAS) [

26] is the oldest and very small set of mammography images comprising 322 MLO digital images of all groups. The scans are standardized to 1024×1024 pixels and stored in PGM format files. The dataset's size can not use for training. Nonetheless, it is a supplementary test data set for exploratory data analysis.

The Magic-5 database [

11] is an Italian database that provides 3369 images from 967 patients. These images, digitized with 12-bit resolution and saved in DICOM format, include several CC, MLO, and lateral views. Like MIAS, ground truth characterizes by centers of MCCs and masses and circles surrounding ROIs. The patient’s age is available as supplementary information, but there is no BI-RADS classification according to the ACR standard. Heterogeneity is the limitation of Magic-5, as the images gather in various environments.

The mammographic images database from LAPIMO (BancoWeb LAPIMO database) [

12] has 1473 images from 320 patients, including CC, MLO, and magnification. The database images are 12-bit files. The database contains information such as scanner brand, patient age, and hormone replacement therapy status.

The INbreast database [

13] contains about 410 images of 115 patients with different lesions (calcifications, masses, distortions, and asymmetries). XML format provides precise contours created by specialists. INbreast is powerful as it is made with full-field digital mammograms (against digitized mammograms) and offers various cases. Moreover, it is available publicly, together with accurate annotations.

The Digital Database for Screening Mammography (DDSM) [

14] contains 2,620 scan-film mammography studies. Normal, malignant, and benign cases with validated pathological information included. Extensive databases accompanied by ground truth verification make DDSM an effective instrument for developing and testing CAD systems. The Curated Breast Imaging Subset of the Digital Database for Screening Mammography (CBIS-DDSM) [

15] contains a subclass of DDSM data curated and selected by trained mammographers. The images are decompressed and transformed to DICOM format. Updated bounding boxes, ROI segmentation, and pathologic diagnosis are also included for training data. ROI annotation of DDSM abnormalities indicates the general location of lesions but without accurate segmentation.

The Breast Cancer Digital Repository (BCDR) [

16] is a comprehensive collection of digital content (digitized film mammography images) and related metadata such as segmented lesions, medical history, BI-RADS classification, image-based descriptors, and confirmed biopsies. The database includes anonymized cases of patients, which annotate by expert radiologists comprising lesion outlines, clinical data, and image-based properties computed from Mediolateral and Craniocaudal oblique mammography image views.

Table 2.

Detailed information on the most common public mammography databases.

Table 2.

Detailed information on the most common public mammography databases.

| Database |

# cases |

# Images |

Resolution (bit/pixel) |

Views |

Image type |

Pros |

Cons |

| MIAS [26](1994) |

161 |

322 |

8 |

MLO |

PGM |

Easy access to data |

Outdated film screen mammograms and lack of modern image sources such as 3D mammography |

Magic-5 [11]

(1999) |

967 |

3369 |

16 |

MLO, CC |

DICOM |

Optimized for use in a distributed setting with grid services |

heterogeneity |

| BancoWeb LAPIMO [12](2011) |

320 |

1400 |

12 |

MLO, CC |

TIFF |

Contain BI-RADs category

Include additional information (patient age, hormone replacement therapy status, and scanner brand). |

Requires administrator approvalLimited in size. |

INbreast [13]

(2012) |

115 |

410 |

14 |

MLO, CC |

DICOM |

Commonly cited by the literature. |

The database is now restricted; |

DDSM [14]

(1999) |

2620 |

10480 |

8-16 |

MLO, CC |

LJPEG |

Commonly cited by the literature. |

Consists of outdated film mammography scans, ROI annotation of abnormalities indicates the general location of lesions but without accurate segmentation. |

| CBIS-DDSM [15](2017) |

1644 |

3468 |

10 |

MLO, CC |

DICOM |

Included. ROI annotation |

Relatively small |

BCDR [16]

(2012) |

1834 |

7315 |

8-14 |

MLO, CC |

TIFF |

Accurate lesion positions contain BI-RADS density annotations, precise mass coordinates, and detailed segmentation plans, Additional patient data (lesion features, prior surgery, biopsy status) is also available. |

It restricts to merely 2D FFDM data, They are limited in size. |

VICTRE [17]

(2018) |

|

217913 |

- |

MLO, CC |

DICOM |

Accurate mammographic lesions. Wholly synthetic. |

Fully synthetic. |

OPTIMUM (2020)

[18] |

NA |

2889312 |

12-16 |

MLO, CC |

DICOM |

Extremely Large Dataset, Open-source API for simple image retrieval in Python |

Require administrator approval, Data only come from patients in the UK. |

A new paradigm was developed [

17] to evaluate digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT) instead of digital mammography (DM), utilizing exclusively in-silico approaches (VICTRE Trial dataset). About 2986 subjects were simulated with radiographic densities and breast sizes representing compressed thicknesses and screening population and imaged on in-silico types of DBT and DM systems utilizing fast Monte Carlo x-ray transport. VICTRE image datasets are in DICOM format. Metadata like image generation, clinical trial description, patient information, lesion absence or presence, imaging study conducted per modality, breast type, and compressed breast thickness are added as the DICOM tags to allow reproducibility.

The OPTIMAM Medical Image Database (OMI-DB) [

18] is an extensive database of mammogram images and related clinical data from multiple NHS Breast Cancer screening sites in the UK. The automated image collection, storage, and processing process facilitates easy expansion across novel imaging sites and the constant supply of new data. The unprocessed and processed medical images, rich associated clinical data, and expert mammography-reader-determined annotations are included in the database, making it appropriate for multiple research applications.

4. Convolutional Neural Networks

Deep learning is a kind of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning imitating how humans obtain definite knowledge types. Deep learning is a crucial element of data science, including predictive modeling and statistics. It benefits data scientists trying to collect, analyze, and interpret large quantities of data. Through deep learning, this process becomes easier and faster.

The convolutional neural network (CNN) architectures are the most common deep learning framework utilized for various applications, from computer vision to natural language processing [

19]. In this section, we will review the different CNN architecture types that frequently employ for object detection and image classification.

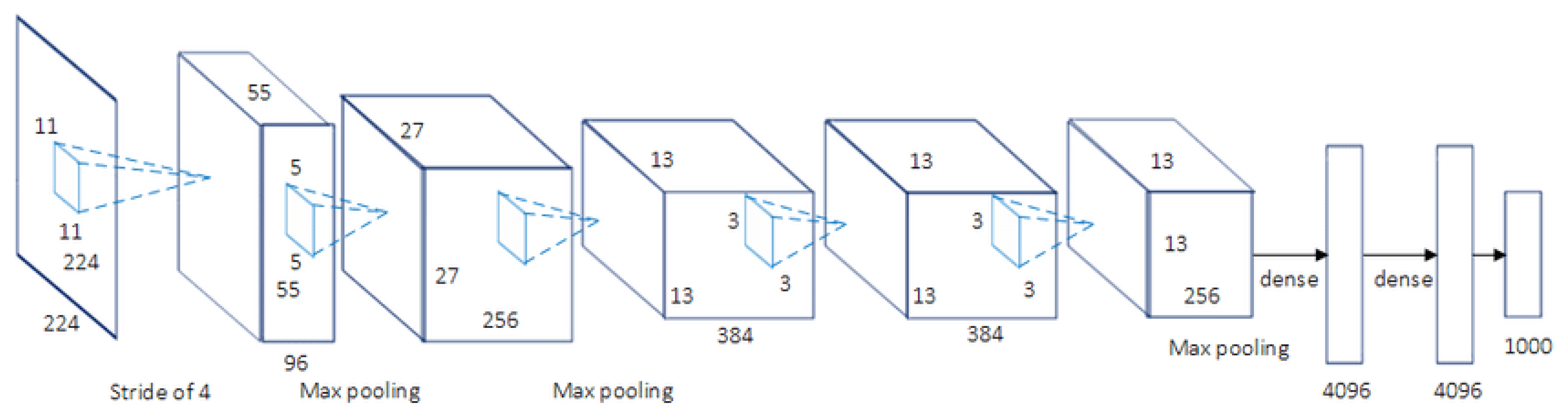

AlexNet [

20] is a famous CNN architecture, and its results have revolutionized image recognition and classification. AlexNet, as the first large-scale CNN, was utilized to conquest the ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge (ILSVRC) (2012). Large-scale image datasets were used to design the AlexNet architecture, and state-of-the-art results achieve for publication. Five convolutional layers are contained in AlexNet with a mixture of mdax-pooling layers, two dropout layers, and three fully connected layers. Relu is the activation function utilized in all layers, while Softmax uses the activation function in the output layer. About 60 million parameters include in this architecture. The AlexNet architecture is presented in

Figure 2.

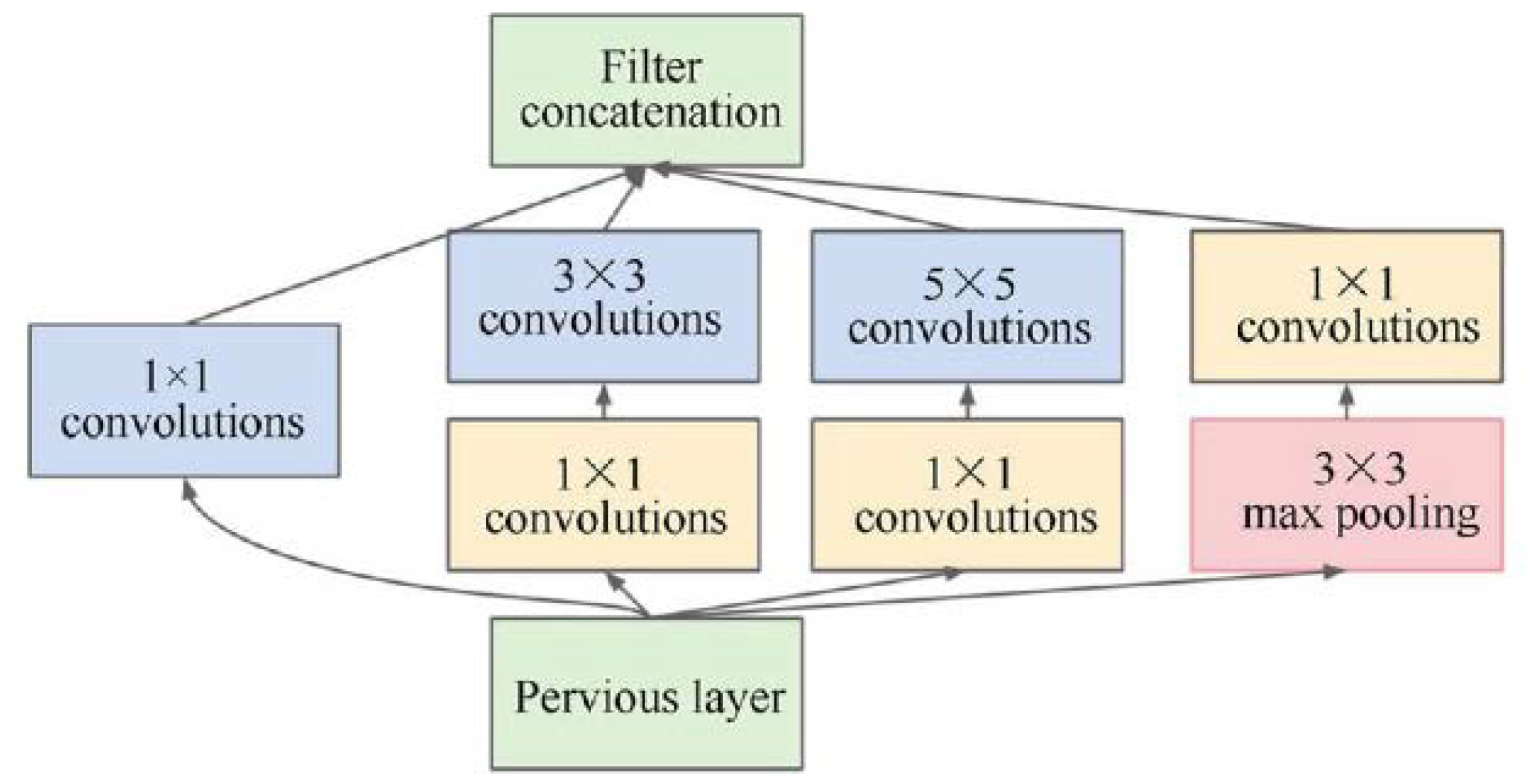

Google uses GoogLeNet, also called Inception-V1, as the CNN architecture to conquest ILSVRC 2014 classification task [

21]. It has a remarkably decreased error rate compared to former winners ZF-Net (Ilsvrc 2013 winner) and AlexNet (Ilsvrc 2012 winner). The error is less significant than VGG (2014 runner-up) based on the error rate. It presents more profound architecture using distinct methods, such as global average pooling and 1×1 convolution. Computationally, GoogleNet CNN architecture is expensive. Heavy unpooling layers are used on top of CNNs to decrease the parameters that must be learned and eliminate spatial redundancy during training. Features shortcut connections within the first two convolutional layers before adding new filters in later CNN layers. The basic architecture of the inception module is display in

Figure 3, along with the concepts of integration and division.

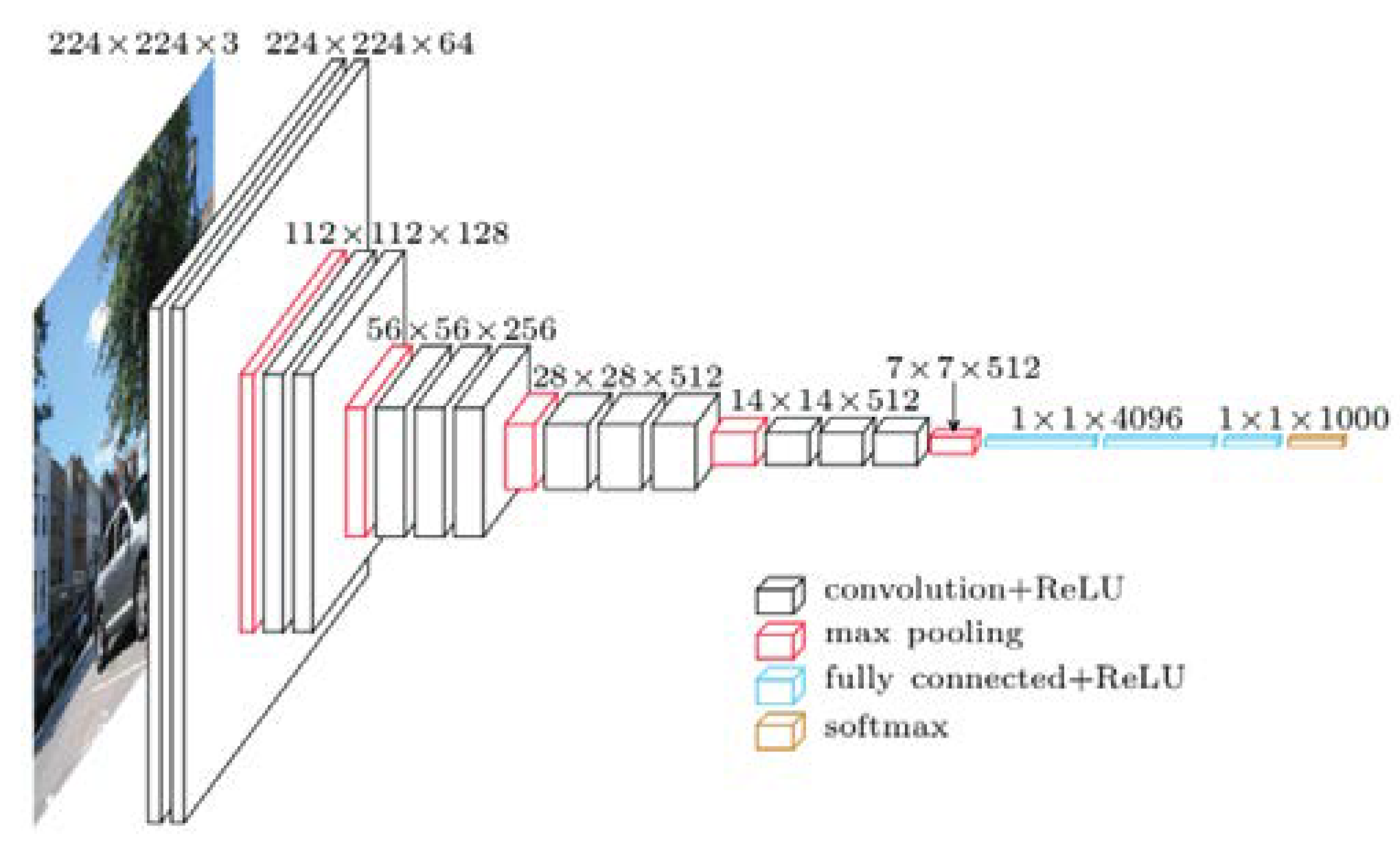

VGGNet was presented by Andrew Zisserman et al. and Karen Simonyan [

22] at Oxford University. As a 16-layer CNN, VGGNet is trained on over one billion images( 1000 classes) and has over 95 million parameters. It can take large input images with 4096 convolutional properties and 224×224-pixel resolutions. It is expensive to train CNNs with such large filters, thus requiring many data. As a result, for most image arrangement tasks requiring input images of 100×100 pixels and 350 × 350 pixels sizes, CNN architectures like GoogLeNet( AlexNet architecture) perform better than VGGNet [

23]. Due to its suitability for various tasks, including object detection, the VGG CNN model is computationally efficient and is an excellent foundation for many computer vision applications. Its deep feature representations are used in YOLO and other neural network architectures.

Figure 4 represents the standard VGG16 network architecture diagram.

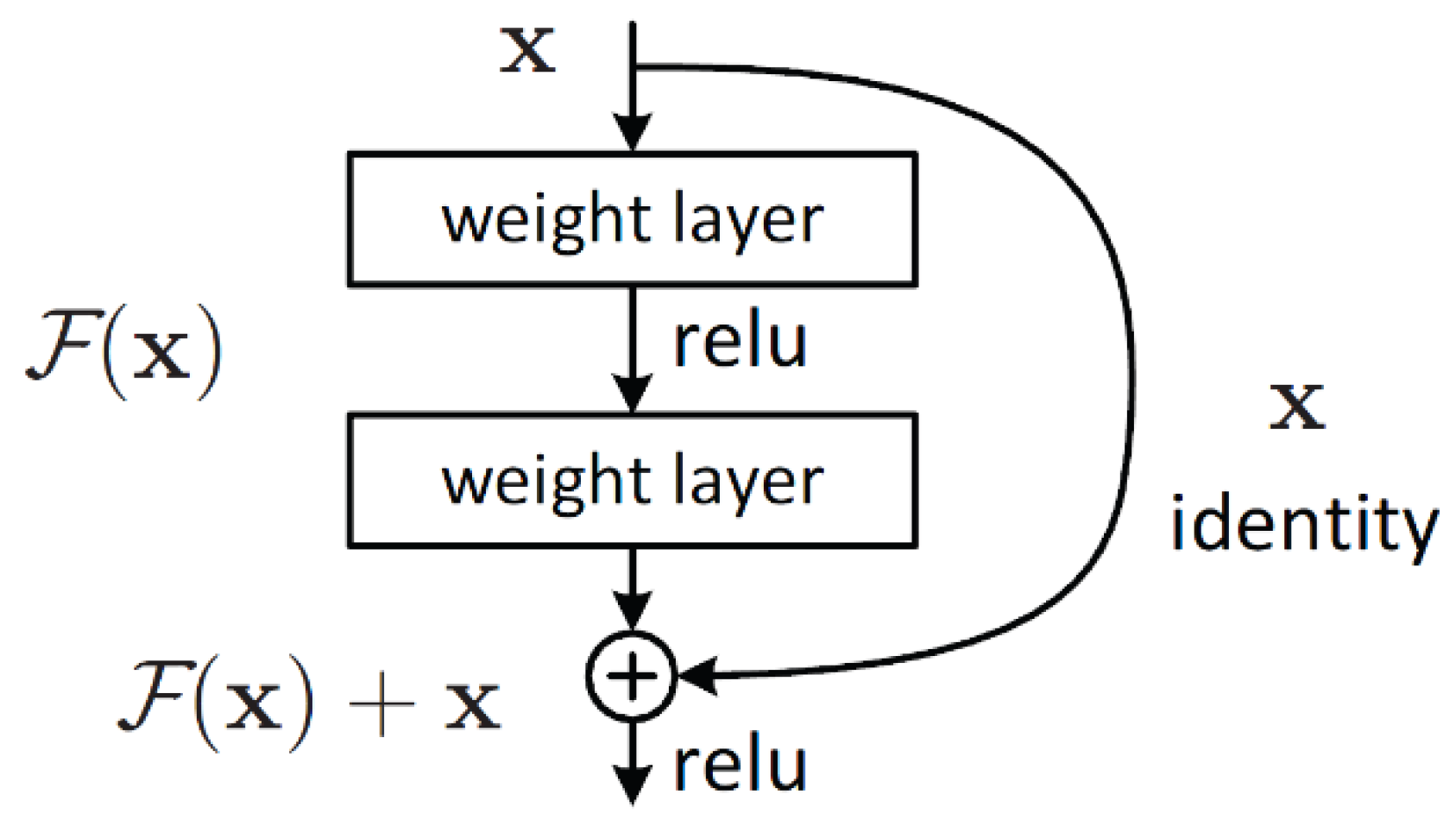

Kaiming He et al. developed ResNet as the CNN architecture [

24] to obtain the ILSVRC 2015 sorting task with a top-five error of only 15.43%. About 152 layers are contained in the network with more than one million parameters. It is considered deep even for CNNs, as training the network on the ILSVRC 2015 dataset takes over 40 days on 32 GPUs. Mainly, CNNs are utilized for image sorting tasks with 1000 classes. However, according to ResNet, CNNs can be successfully used to solve natural language processing problems such as machine comprehension or sentence completion. It was utilized by the Microsoft Research Asia team (2016, 2017).

Figure 5 represents the residual block architecture. In conclusion, ResNet overcomes the “vanishing gradient” problem, thus constructing networks with thousands of convolutional layers outperforming shallower networks. During backpropagation, a vanishing gradient happens.

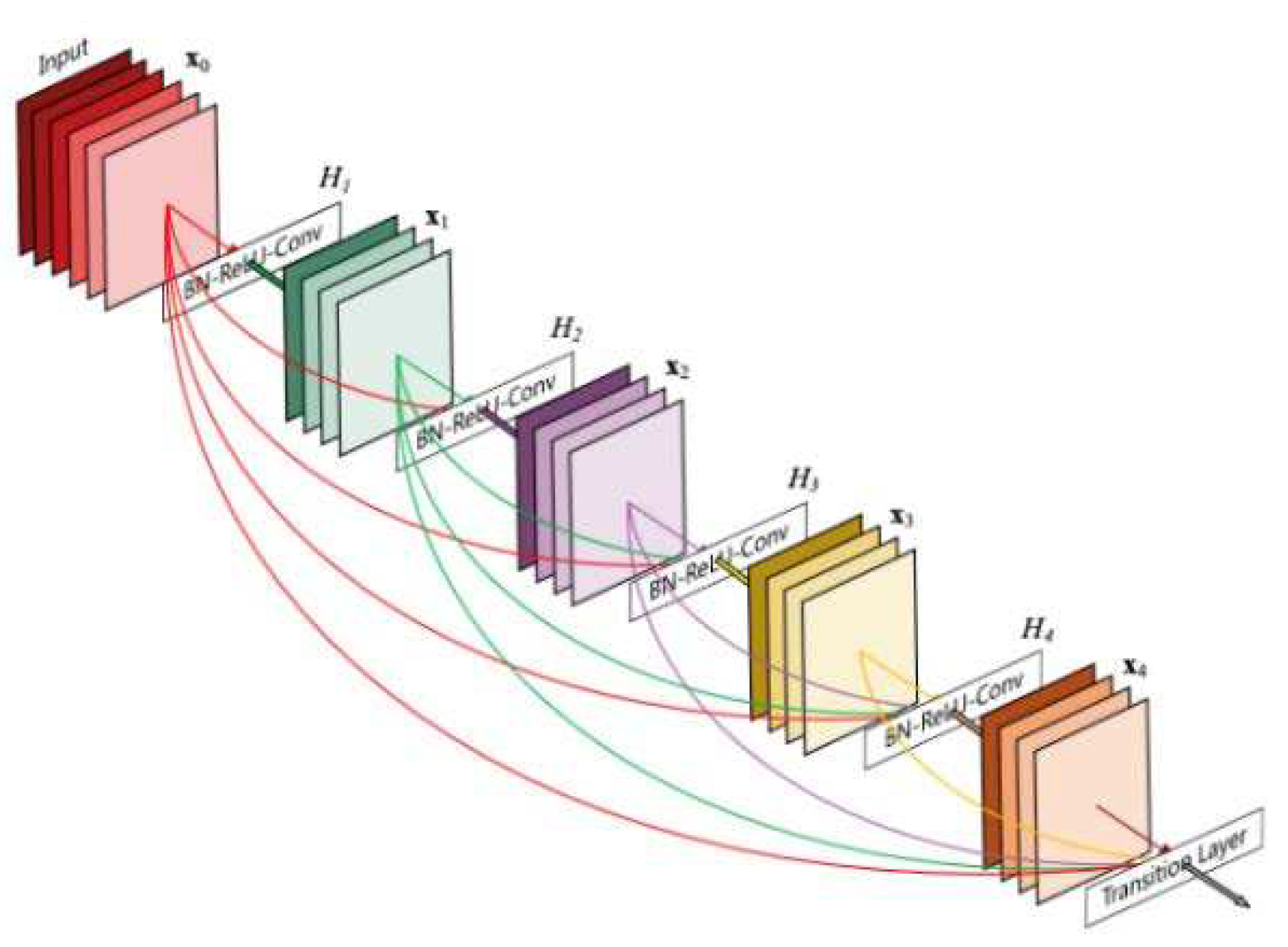

A DenseNet [

25] is a convolutional neural network that connects all layers directly (with matching feature-map sizes) using dense connections between layers through dense blocks. Each layer receives additional inputs from all previous layers and transmits them to all succeeding layers using its feature maps to maintain the feed-forward nature. The identity shortcut stabilizing the training also limits its representation capacity for ResNet, while there is a higher capacity for DenseNet with multilayer feature concatenation. A DenseNets has several compelling benefits, such as reducing the vanishing-gradient problem, encouraging feature reuse, bolstering feature propagation, and significantly reducing parameter count.

Figure 6.

DenseNet architecture.

Figure 6.

DenseNet architecture.

Google researchers developed Xception [

26] as an architecture for deep convolutional neural networks, including Depthwise Separable Convolutions. According to Google's interpretation of Inception modules, they are an intermediate step in convolutional neural networks between regular convolution and the depthwise separable convolution operation (a depthwise convolution after a pointwise convolution). Hence, it is possible to comprehend a depthwise separable convolution as an Inception module with numerous towers. Thus, a new deep convolutional neural network architecture was developed inspired by Inception, in which Inception modules were substituted with depthwise separable convolutions. Two key points orient XCeption as a compelling architecture: Shortcuts between Convolution blocks, as in ResNet, and depthwise Separable Convolution. Classical convolutions are replaced by depthwise separable convolutions that should be more effective based on computation time.

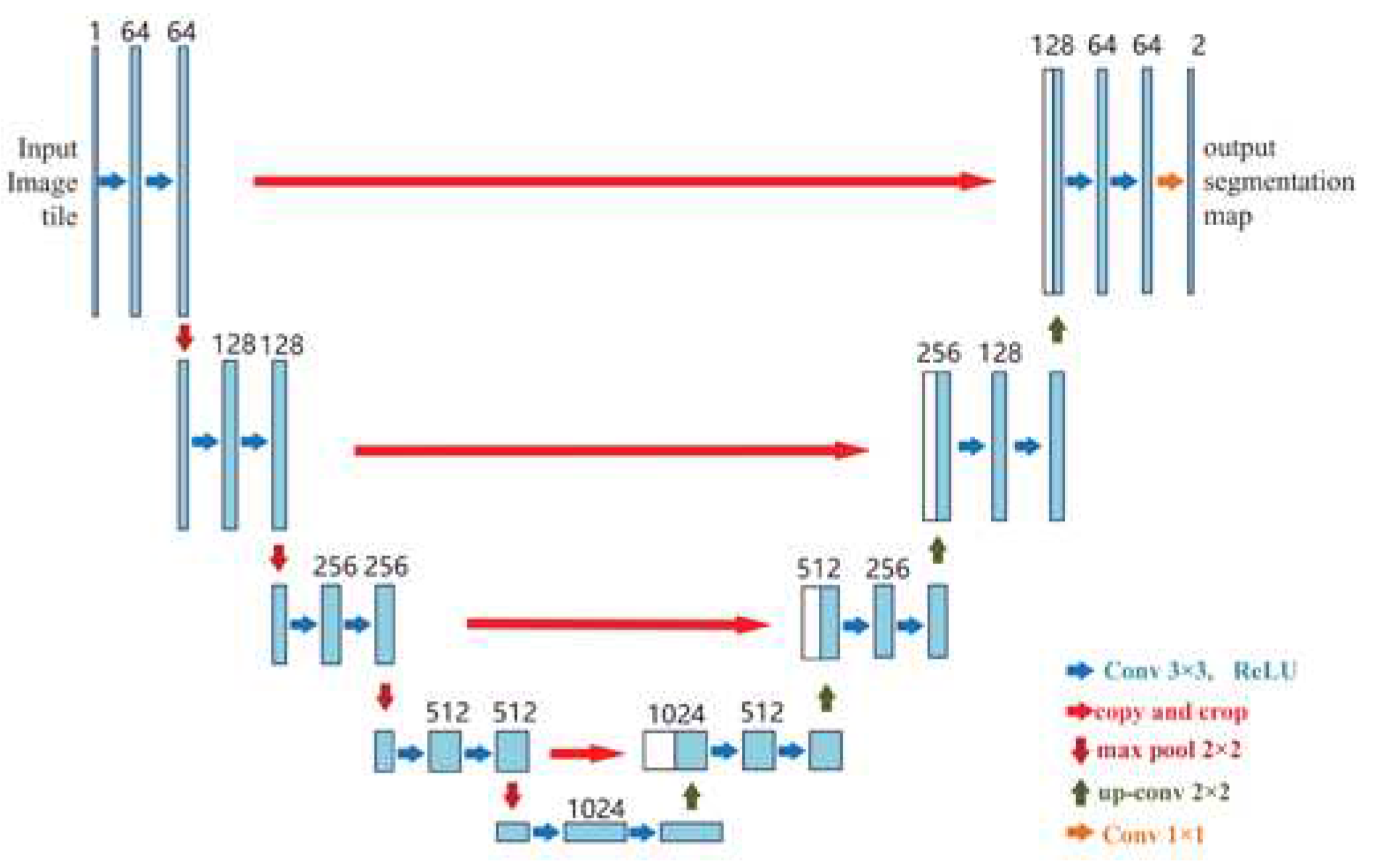

Ronneberger et al. proposed UNet as the first high-performance encoder-decoder structure [

27], widely used for medical image segmentation. The U-Net architecture is shown in

Figure 7. One of the notable points in the architecture of this network is the lack of fully connected layers, which reduces the complexity of the network. The idea hidden in this algorithm is to create a sequential contracting path that happens by replacing the pooling layers instead of the sampling layers. After collecting the desired features, a sequential expansion path is used. Such a path is used to reconstruct the original image and spread the background information into it. In short, the U-Net network has two symmetric and identical contraction and expansion paths so that whatever is removed in the contraction path is restored in the expansion path. U-Net has become the target for most medical image segmentation tasks, stimulating many significant improvements.

Mask R-CNN [

28] was developed on top of Faster R-CNN as a state-of-the-art model, for instance, segmentation [

29]. Faster R-CNNs are convolutional neural networks based on regions that return bounding boxes for each object and its class label with a confidence score. By Faster R-CNN, object class is predicted along with bounding boxes. Mask R-CNN is an extension of Faster R-CNN with a further branch for predicting segmentation masks on each Region of Interest (RoI) (

Figure 8).

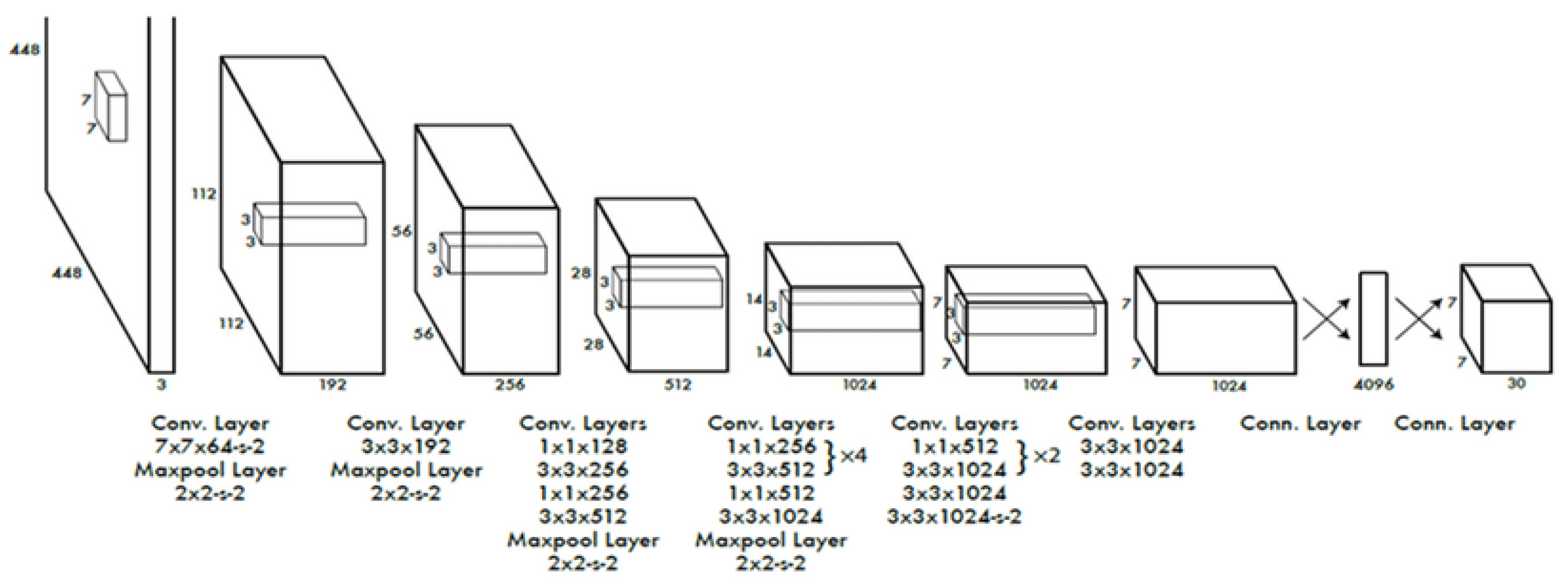

Among the most popular object detection algorithms and model architectures in real-time is You Only Look Once (YOLO) [

30], which utilizes one of the best neural network architectures to create higher accuracy and overall processing speed. A single neural network is used in the algorithm for the full image. Then, the image is divided into regions and bounding boxes to predict probabilities for each area. The estimated probabilities weight these bounding boxes.

Figure 9 represents the YOLO architecture.

Table 3 summarizes the pre-trained convolutional neural network architectures—the limitations and strengths of these models

Table 4 shows.

Table 4.

Comparison of popular pre-trained CNN architectures.

Table 4.

Comparison of popular pre-trained CNN architectures.

| Model |

Year |

Image Size |

Layer No. |

Filter No. |

Normalization |

Activation |

New Features |

| AlexNet |

2012 |

227×227 |

8 |

3,5,11 |

Data augmentation, Dropout |

softmax |

Overlap integration, local response normalization, ReLU |

| VGGNet |

2014 |

224×224 |

16/19 |

3 |

Data augmentation, Dropout |

softmax |

Uniform filter size (3x3) across the network |

| ResNet |

2014 |

224×224 |

22 |

1,3,5,6 |

Data augmentation, Dropout |

softmax |

An Inception module with the concept of division and integration |

| GoogleNet |

2015 |

224×224 |

50/101/152 |

1,3,7 |

Data augmentation, Dropout |

softmax |

Residual block concatenation |

| DenseNet |

2017 |

224×224 |

201 |

|

|

|

Cross-layer information flow |

| Xception |

2017 |

299×299 |

126 |

3 |

Data augmentation, Dropout |

softmax |

Depth separable convolution layers |

| U-Net |

2015 |

256×256 |

23 |

|

|

|

Encoder-decoder structure |

| Mask RCNN |

(2017). |

1024×1024 |

|

|

|

|

|

| YOLO |

2015 |

448× 448 |

24 |

s |

|

|

Bounding box regression |

Table 4.

The comparison of the model's strengths and limitations.

Table 4.

The comparison of the model's strengths and limitations.

| |

Strengths |

Limitations |

| AlexNet |

First primary CNN model that used GPUs for training, variable size filters to extract low, medium, and high-level features, deep and wide network |

The large size of filters causes an aliasing effect |

| VGGNet |

The decision function is more discriminative |

Higher cost to assess than shallow networks, using a massive deal of parameters and memory |

| ResNet |

Overcame the "vanishing gradient." |

Long training time, overfitting of hyperparameters |

| GoogleNet |

Using multi-scale filters in layers, using bottleneck layer to reduce the number of parameters |

The bottleneck layer's intricate structure and information loss |

| DenseNet |

It lets each layer access the features of all former layers, optimizing the gradient flow during training and allowing the network to acquire knowledge more effectively. |

The feature maps of each layer are spliced with the previous layer, and the data is replicated multiple times. |

| Xception |

Cardinality is used to introduce a depth-wise separable convolution to learn effective abstractions. |

High computational cost |

| UNet |

Possibility to use global context and location at the same time. |

Learning may slow down in the middle layers of deeper models |

| Mask RCNN |

It makes the training faster and deeper with more layers |

Poor edge segmentation owing to the poor segmentation of small targets and blurred bounding box of the target image |

| YOLO |

Fast inference speed (which allows it to process images in real-time), provides end-to-end training |

It struggles to detect smaller images within a group of images, unable to detect new or unusual shapes successfully |

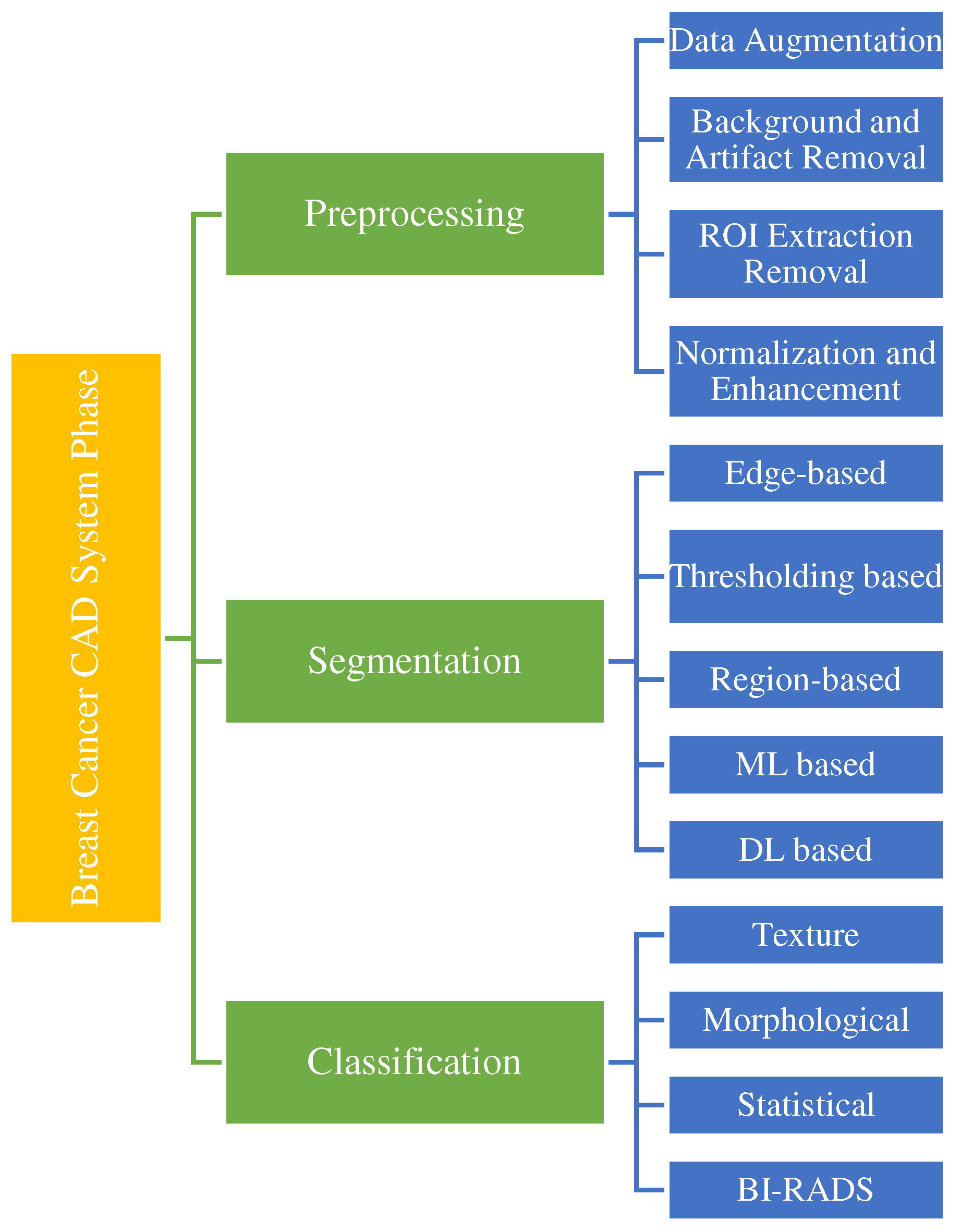

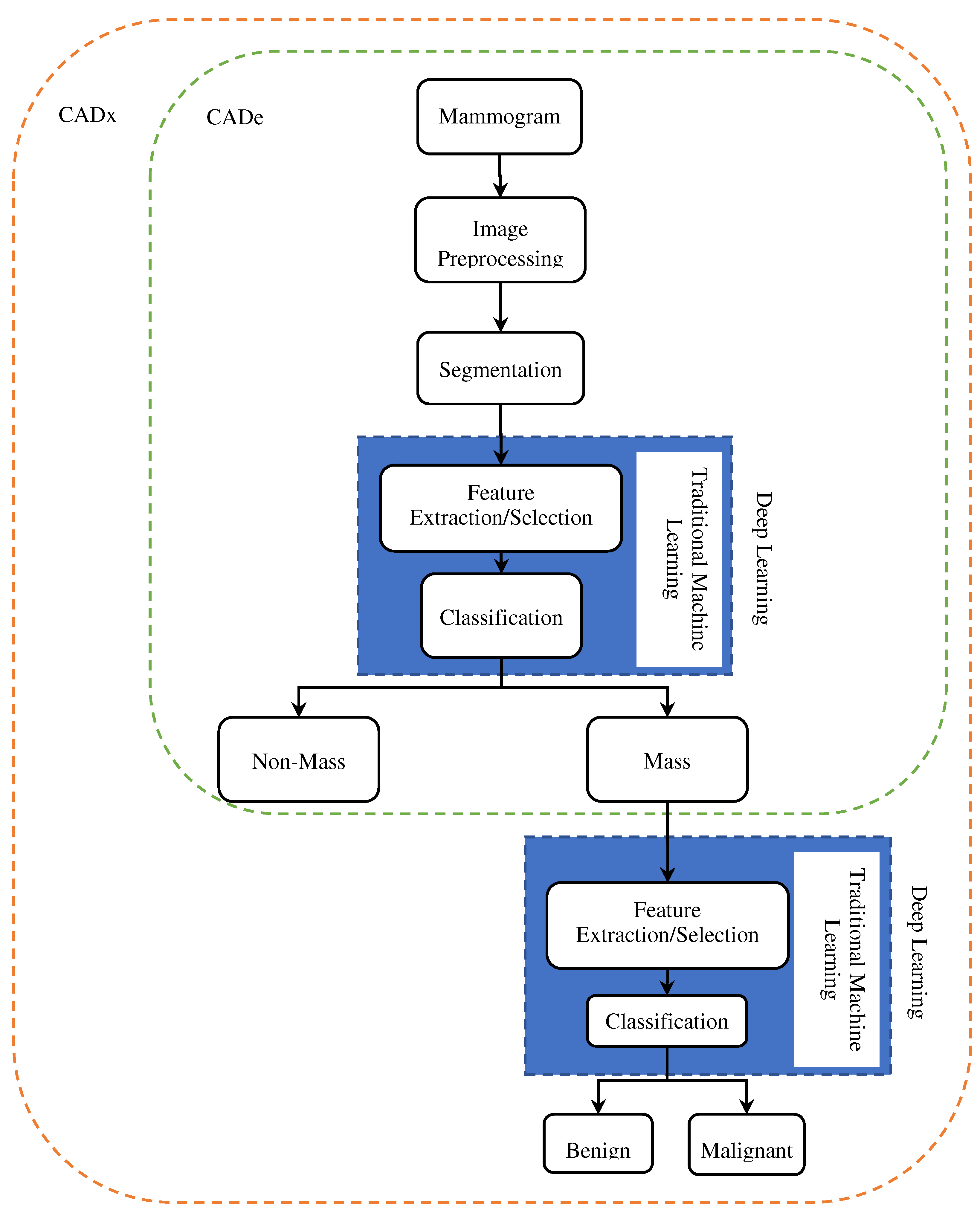

5. CAD Systems

Several effective CAD systems have been developed with considerable progress in computer-aided diagnosis (CAD). Novel avenues have been created by machine learning (ML) advances for computer-assisted diagnosis of medical images. Moreover, the enhancements in ML methods, primarily based on deep learning (DL), have impacted substantially the CAD systems' performance. CAD systems characteristically contain computer-aided diagnosis (CADx) and computer-aided detection (CADe). CADe systems can identify abnormal areas in mammograms for radiologists, though CADx systems can differentiate between abnormal and normal areas and classify them as benign or malignant.

Figure 10 shows the CAde/CADx pipeline based on deep learning and machine learning. As illustrated, in traditional machine learning, the classification and feature extraction process is done in two separate stages. Still, in deep understanding, the feature extraction process is completely automatic and combined with classification. CAde systems, the process continues to the stage of mass detection and cannot classify the masses.

Researchers have made many efforts in the last decade to develop CAD systems for breast cancer diagnosis and prognosis based on various imaging models like mammography, MRI, and ultrasound and have achieved significant results. As shown in

Figure 10, breast cancer CAD systems consist of steps, including preprocessing [

31,

32], mass detection and segmentation [

33,

34,

35], feature extraction [

36,

37,

38,

39], and classification [

40,

41,

42].

Preprocessing can significantly limit the searches for abnormalities on only the breast area with no effect from the background. By preprocessing, mammogram size is reduced, thus improving the images' quality

to make a more reliable feature extraction stage. By the presence of artifacts and noises, breast cancer detection can be disturbed, thus reducing the accuracy rate in analysis. Preprocessing removes all irrelevant information, excessive parts, artifacts, and noises. The mammogram images are texture in nature. Hence, appropriate enhancement should be obtained for these images. Contrast limit adaptive histogram enhancement (CLAHE) [

43] is a popular image contrast improvement technique.

Breast tumors can be quite adjustable in appearance and size. Therefore, outlining their margins and extent precisely on a mammography image can be effective in both monitoring treatment response or tumor progression and treatment planning. In the segmentation stage, a picture is partitioned into multiple parts or regions, often based on the characteristics of the pixels in the image, to identify a tumor's spatial location. Compared to traditional segmentation methods, CNN-based segmentation methods are more robust [

44].

Masses can be malignant (cancerous) or benign (noncancerous). The benign mass tends to grow slowly and does not spread. Malignant mass can rapidly develop, invade and destroy adjacent normal tissues, and spread throughout the body. In the classification stage, the masses categorize into two groups malignant and benign. In this section, firstly, we reviewed the studies done on mass segmentation by deep learning models, then discussed the breast cancer mass classification approaches.

Figure 11.

Techniques in different stages of breast cancer CAD systems.

Figure 11.

Techniques in different stages of breast cancer CAD systems.

5.1. Breast Masses Segmentation

Segmentation is a vital part of medical image analysis and part of CAD and pathology research. Medical image segmentation involves anatomical structure and locating lesions, masses, or any abnormalities in a medical image.

Radiologists can segment masses manually, which is expensive and time-consuming, or they can fully automate the process using CAD. With the recent advancements in computer vision, deep convolutional neural networks (DCNNs) have made breakthroughs in medical image segmentation applications. This section discusses different techniques for segmenting breast masses from mammographic images in the literature.

Table 5 summarizes studies on breast mass segmentation in terms of different DCNN architectures.

Dhungel et al. [

44] proposed statistical learning approaches via a conditional random field (CRF) model to segment breast masses from mammograms. They use tree re-weighted (TRW) belief propagation to discover the marginal of the CRF model and minimize the mass segmentation error.

Zhu et al. [

45] proposed an end-to-end breast mass segmentation model that makes use of a conditional random field (CRF) and a fully convolutional network (FCN). Adversarial learning has been employed to remove the overfitting owing to the small size of mammogram datasets.

Al-Antari et al. [46] developed a CAD for mass detection, classification, and segmentation using deep learning. They used You-Only-Look-Once (YOLO) to detect masses and applied a full-resolution convolutional network (FrCN) to segment the mass. Using a deep convolutional neural network (CNN), the mass is recognized and classified as malignant or benign.

Li et al. [

47] improved the performance of U-Net segmentation for mass segmentation by Conditional Residual U-Net (CRU-Net) by integrating the merits of probabilistic graphical modeling and residual learning.

The complex shape variation of pectoral muscle boundary and overlap of the breast tissue make Mammography image segmentation a challenge. Rampun et al. [

48] developed a method using a convolutional neural network (CNN) based on Holistically-nested Edge Detection (HED). By changing the architecture of the HED network, they discover "contour-like" objects, specifically in mammograms. The presented framework produces a probability map to estimate the pectoral muscle's initial boundary. It then processes these maps by extracting morphological features to discover the actual edge of the pectoral muscle.

A new framework was proposed by Shen et al. [

49] based on a conditional generative adversarial network (cGAN) to enhance breast mass segmentation performance. In their method, mapping between images and equivalent segmentation masks learns the mass image's distribution. Next, using cGAN produces several lesion images. Then, the created adversarial specimens are concatenated with the original samples to generate a dataset with incremented diversity. Also, they introduced an enhanced U-net and trained it on former augmented datasets for breast mass segmentation.

Usually, mass segmentation in mammography has restrictions of intra-class and inter-class inconsistency in distinction. Wang et al. [

50] presented a multi-level nested pyramid network (MNPNet) to address this limitation. MNPNet includes a decoder and an encoder. The encoder applies ASPP to encode high-level semantic, contextual, and low-level detail information. The segmentation results are refined by the decoder along mass boundaries.

Li et al. [

51] integrated attention gates( AGs) into a dense U-Net. A dense convolutional network comprises the encoder structure, and a U-Net decoder integrated with AGs serves as the decoding structure.

Shen et al. [

52] combined joint classification and segmentation using a mixed-supervision-guided and residual-aided classification U-Net model (ResCU- Net).

Abdelhafiz et al. [

53] improved the U-Net structure by adding residual attention modules (RU-Net) to segment mass lesions in mammogram images. Subsequently, the ResNet classifier (RU-Net) was used for classification.

Ghosh et al. [

54] used intuitionistic fuzzy soft sets (IFSS) and Multi-granulation rough sets for mammogram segmentation.

A conditional Generative Adversarial Network (GCN) was designed by Singh et al. [

55] to segment a breast tumor within a region of interest (ROI) in a mammogram.

Chen et al. [

56] proposed an enhanced U-Net as the segmentation network and multi-adversarial learning for capturing multi-scale image information for precise breast mass segmentation. To defeat the unbalanced class problem, they used weighted cross-entropy loss.

Abdelhafiz et al. [

57] presented a model based on U-Net architecture for automatically segmenting mass lesions in mammography images. Their model is trained on four databases, CBIS-DDSM, BCDR-01, INbreast, and UCHC, and an adaptive median filter was used to reduce noise in their model.

Yu et al. [

58] proposed a small-scale target detection model equivalent to Mask R-CNN's Dense Mask. They enhance small-scale mass detection accuracy. When using multilayer feature maps, their method produces redundant data.

Soleimani et al. [

59] developed a two-stage segmentation technique [

59]based on convolutional neural networks and graph-based image processing. First, using CNN, the position of the breast-pectoral boundary is predicted at various levels of spatial resolution. Then the found border is recovered using the shortest pathway problem on a graph designed specially.

Min [

60] developed a framework for breast mass detection and segmentation from mammograms regarding Mask R-CNN and pseudo-color mammograms. They utilized a multi-scale morphological sifter (MMS) to improve the detection performance of Mask R-CNN.

Al-Antari et al. [

61] proposed a wholly integrated CAD system oriented by deep learning for detecting, segmenting, and classifying breast lesions from mammograms. FrCN (Full resolution convolutional network) and YOLO are implemented to detect and segment breast lesions. Ultimately, three conventional deep learning models are adopted separately, including ResNet-50, regular feed-forward CNN, and InceptionResNet-V2, for classifying breast lesions as malignant or benign.

Safari et al. [

62] developed a system for segmenting the dense tissues in mammogram images using conditional Generative Adversarial Networks (GCN) and then classifying them based on convolutional neural networks.

Ahmed et al. [

63] applied two deep learning-based semantic segmentation frameworks, Mask RCNN and DeepLab, to segment the cancerous region in mammogram images.

For breast mass segmentation in whole mammograms, a new attention-guided dense-upsampling network( AUNet) was suggested in [

64]. Asymmetrical encoder-decoder architecture in AUNet makes combining low- and high-level features easier. To represent rich-information channels, it has a channel-attention feature.

Segmentation and multi-detection of breast lesions were developed by Bhatti et al. [

65] based on an RoI-based Convolutional neural network (CNN) and regional learning technique.

Zeiser et al. [

66] presented a mass segmentation system for mammogram images via the U-Net model.

Tsochatzidis et al. [

67] proposed a modified CNN convolutional layer based on the U-Net model. Moreover, a novel loss function was introduced that adds a term to the standard cross-entropy, intending to direct the attention of the network to the dense region and penalize the activation of stable features based on their location.

A deeply supervised U-Net (DS U-Net) model with dense conditional random fields( CRFs) was proposed by Ravitha et al. [

68]. They combined deep supervision with U-net to increase the network's focus on the edge of suspicious areas.

Salama et al. [

69] provided a CCN mammogram image classification and segmentation model. The breast region is segmented from the mammogram images using the modified U-Net model.

The proposed model in [

70] is inspired by the fact that the properties learned from the vertical and horizontal directions can present informative and complementary textual information to improve the ability to distinguish between various textures. Their proposed model, Crossover-Net, uses this fact to segment the masses.

Table 5.

Studies on the segmentation of breast cancer.

Table 5.

Studies on the segmentation of breast cancer.

| References |

Year |

Methods |

Dataset |

Model Performance |

| Dhungel et al. [44] |

2015 |

Tree Re-weighted Belief Propagation |

INbreast and DDSM-BCRP |

Dice: 89% |

| Zhu et al. [45] |

2018 |

End-to-End Adversarial FCN-CRF Network |

INbreast, DDSM- BCRP |

Dice: INbreast-90.97% DDSM-BCRP-91.30% |

| Al-Antari et al. [46] |

2018 |

YOLO, FrCN, DCNN |

INbreast |

Mass segmentation:

Accuracy: 92.97%,

MCC: 85.93%,

F1-score: 92.69%,

Jaccard: 86.37% |

| Li et al. [47] |

2018 |

Conditional Residual U-Net (CRU-Net) |

INbreast, DDSM-BCRP |

Dice:

INbreast 93.66%,

DDSM-BCRP 93.32% |

| Rampun et al. [48] |

2019 |

CNN based on Holistically Nested Edge detection |

MIAS, BCDR, INbreast, CBIS- DDSM |

Jaccard: INbreast: 92.6%, MIAS: 94.6%, CBIS-DDSM: 95.7%, BCDR: 96.9%

Dice: MIAS: 97.5%, INbreast: 95.6%, BCDR: 98.8%, CBIS-DDSM: 98.1% |

| Shen et al. [49] |

2019 |

cGAN, Unet |

INbreast, Private |

Private: 88.82%; Accuracy: INbreast: 92% |

| Wang et al. [50] |

2019 |

PyramidNet (Multi-level Nested Pyramid Network) |

INbreast, DDSM |

Dice: DDSM: 91.10%, INbreast: 91.69% |

| Li et al. [51] |

2019 |

Densely Connected U-Net with Attention Gates (AGs) |

DDSM |

F1-score:82.24±0.06

Sensitivity 77.89±0.08 |

| Shen et al. [52] |

2019 |

Residual-aided Classification U-Net Model (MS-ResCU-Net) and Mixed-Supervision-guided |

INbreast |

Accuracy: 94.16%

Dice: 91.78% |

| Abdelhafiz et al. [53] |

2019 |

Residual attention U-Net model (RU-Net) + ResNet classifier |

DDSM, BCDR-01,INbreast |

Accuracy: 98%

Dice: 98%

IOU: 94% |

| Ghosh et al. [54]] |

2020 |

Fuzzy Sets |

MIAS |

Accuracy:88.46% |

| Singh et al. [55] |

2020 |

cGAN |

INbreast, Private |

Dice:94%

IOU: 87% |

| Chen et al. [56] |

2020 |

Modified Unet |

INbreast, CBIS- DDSM |

Dice: INbreast: 81.64%, CBIS-DDSM: 82.16%

Accuracy: INbreast: 99.43%, CBIS-DDSM: 99,81% |

| Abdelhafiz et al. [57] |

2020 |

Vanilla U-Net |

Private |

Accuracy: 92.6%,

Dice:95.1%,

IOU: 90.9 % |

| Yu et al. [58] |

2020 |

Dense Mask-RCNN |

CBIS-DDSM |

Precision: 65% |

| Soleimani et al. [59] |

2020 |

End to End CNN |

CBIS-DDSM, INbreast, MIAS |

Average Dice: 97.22 ± 1.96%, Average Accuracy: 99.64±.27% |

| Min et al. [60] |

2020 |

Mask R-CNN |

INbreast |

Dice: 88% |

| Al-Antari et al. [61] |

2020 |

YOLO

Full Resolution Convolutional Network (FrCN)

Regular Feed-forward CNN, ResNet-50, and InceptionResNet-V2 |

INbreast |

Accuracy: 92.97%,

MCC: 85.93%,

F1-score: 92.69%,

Jaccard 86.37%. |

| Safari et al. [62] |

2020 |

Conditional Generative Adversarial Networks (cGAN) |

INbreast |

accuracy: 98&

Dice 88%

Jaccard 78% |

| Ahmed et al. [63] |

2020 |

DeepLab and mask RCNN |

MIAS, CBIS-DDSM |

AUC: mask RCNN: 98.0%, DeepLab: 95.0%

Precision: mask RCNN: 80%

DeepLab: 75% |

| Sun et al. [64] |

2020 |

Attention-guided Dense-Upsampling network (AUNet) |

CBIS-DDSM, INbreast. |

Dice: CBIS-DDSM: 81.8%, INbreast: 79.1% |

| Bhatti et al. [65] |

2020 |

Masked Regional Convolutional Neural Network fixed with Feature Pyramid Network (Mask RCNN-FPN) |

DDSM and INbreast |

Precision: 84%

Accuracy: 91% |

| Zeiser et al. [66] |

2020 |

Modified U-net |

DDSM |

Sensitivity: 92.32%

Specificity: 80.47%,

Accuracy: 85.95%

Dice: 79.39%,

AUC: 86.40% |

| Tsochatzidis et al. [67] |

2021 |

Modified U-Net |

DDSM-400 and

CBIS-DDSM |

AUC: DDSM-400: 88%, CBIS-DDSM: 860%

Accuracy: DDSM-400: 73.8%, CBIS-DDSM:77.4% |

| Ravitha et al. [68] |

2021 |

Deeply supervised U-Net model (DS U-Net) armed with Dense Conditional Random Fields (CRFs) |

DDSM and INbreast |

Dice: CBIS-DDSM: 82.9%, INBREAST: 79% |

| Salama et al. [69] |

2021 |

Modified UNet |

MIAS, CBIS-DDSM |

Accuracy 98.87%, AUC 98.88% sensitivity 98.98%, precision 98.79%, F1 score 97.99% |

| Yu et al. [70] |

2021 |

CrossoverNet |

DDSM, INbreast |

Dice: DDSM: 0.9250 INbreast: 0.9126 |

5.2. Breast Masses Classification

The emergence of deep learning caused huge success in image processing owing to its performance and ability to generalize across diverse data. Mass detection can generally be divided into two stages: mass localization and mass classification. These two steps can be done more easily and efficiently through deep CNNs,

This section reviews a CAD system oriented by a convolutional neural network (CNN) using deep learning for classifying mammogram images into normal, benign, and malignant from mammography images.

Table 6 summarizes the studies' proposed method to detect and classify breast abnormalities based on DCNN architectures.

Dhungel et al. [

71] proposed an integrated CAD system to detect, segment, and classify breast masses.

They apply a cascade of deep learning methods for selecting hypotheses refined in Bayesian optimization. They utilized deep structured output learning refined by a level set technique for the segmentation. Ultimately, fine-tuned pre-trained deep learning classifiers were applied for classification.

Kooi et al. [

72] compared different CAD systems for detecting and classifying mammography via a feature set designed manually and a convolutional neural network. The findings of DCNN were compared with a group of experts in medical imaging, indicating almost the same performance for DCNN and the human reader.

A graph-based semi-supervised learning scheme was developed by Sun et al. [

73] utilizing a deep convolutional neural network for breast cancer detection. Their proposed outline only needs a small portion of labeled data for training.

Al-Masnia et al. [

74] developed a CAD system for the YOLO algorithm for detecting breast mass. Through fully connected neural networks (FCNN), they performed mass classification. This study used six hundred mammography images of the DDSM data set. They also utilized data augmentation.

A fully integrated system was presented by Al-Antari et al. [

46] that includes all detection, classification, and segmentation tasks. In this work, the YOLO approach is used to detect the mass. The segmentation is done using the full convolutional network (FrCN). A deep convolutional neural network (DCNN) was utilized to detect the mass angroupassify it as malignant or benign.

Ribli et al. [

75] use the Faster R-CNN method to detect and classify masses. The suspicious region produced by this method is improved by fine-tuning the hyperparameters.

Diniz et al. [

76] used a simple CNN for mass detection in mammography images. This method creates a model for mass detection in dense and non-dense areas.

The framework proposed in [

77] exploited transfer learning to detect and classify cancer masses. They extracted properties from images using three pre-trained deep learning architectures, known as, GoogleNet, ResNet, and VGGNet, then fed them into a fully connected layer to classify benign and malignant masses using average pooling classification.

To minimize annotation efforts, Shen et al. [

78] proposed a new learning framework for mass detection by incorporating self-paced learning (SPL) and deep active learning (DAL). The annotation efforts of radiologists can be significantly reduced by DAL, thus improving the model training efficiency by achieving better performance with fewer overall annotated specimens. The SPL can lessen the data ambiguity and present a strong model capable of generalization in different scenarios.

Savelli et al. [

79] developed a multi-depth CCN method to detect small lesions in digital medical images. They also used a multi-text ensemble of CNN to learn different levels of the spatial texture of the image. Using multi-depth CNNs, they trained on image patches with various dimensions and then combined them. Hence, the final ensemble can discover and trace abnormalities in the images through the surrounding context of a lesion and the local features.

A new approach was developed by Bruno et al. [

80] based on a combination of two methods, scale-invariant feature transform (SIFT) key points and transfer learning with pre-trained CNNs like AlexNet fine-tuned and PyramidNet on digital mammograms to detect suspicious regions in mammograms. The SIFT method includes selection, preprocessing, and feature extraction steps. Then SIFT method-detected candidate suspicious regions validate by a deep learning network.

Agarwal et al. [

81] proposed a completely automated framework to detect masses in mammography images. Their model is oriented by a faster region-based convolutional neural network (Faster-RCNN).

An integrated CAD system was proposed [

82] for deep learning detection and classification. YOLO detector is used for breast lesion detection. Then, modified CNN architecture, namely ResNet-50, feed-forward CNN, and InceptionResNet-V2, was applied for breast lesion classification.

Li et al. [

83] have developed a two-way mass detection method, including two registration networks and the Siamese-Faster-RCNN network. Registration network for registration of bilateral mammography images and Siamese-Faster-RCNN network for mass detection utilizing images registered by registration network. First, a self-supervised learning network was created to learn the spatial transformation between bilateral mammograms. In the second stage, Siamese Fully Connected (Siamese-FC) network and Region Proposal Network (RPN) is designed.

Shen et al. [

84] proposed a new unsupervised domain-matching framework with adversarial learning for minimizing annotation exertions. The proposed framework uses a task-specific, fully convolutional (FCN) network to predict spatial density. Using adversarial training, annotated features could have been better aligned with well-annotated features. It was indicated that the proposed training converges rapidly. This method has limitations in the case of close masses; it cannot have good accuracy with small masses close to each other.

An end-to-end CAD system was proposed by Aly et al. [

85] based on YOLO. The YOLO is used to detect and classify processes, and their performance is compared. Inception and ResNet are utilized as feature extractors for comparing their classification performance against YOLO.

Xi et al. [

86] presented an abnormality detection method via deep Convolutional Neural Networks. They applied patch-based CNN classifiers for full mammogram images to localize abnormalities without segmentation.

Deb et al. [

87] provided a novel technique for extracting features from different convolutional layers of deep convolution neural network via global average pooling and later concatenation of all extracted properties before end classification.

The models of Rahman et al. [

88] were oriented by modified versions of the pre-trained Inception V3 and ResNet50 for classifying pre-segmented mammogram mass tumors as malignant or benign.

Zhang et al. [

89], including ResNet and Alexnet, developed and investigated [

89]different convolutional neural network-based models for whole mammogram classification. They found that CNN-based models have been optimized via transfer learning. They also found good potential for data augmentation for automatic breast cancer detection regarding the tomosynthesis data and mammograms.

Djebbar et al. [

90] proposed a YOLO-based CAD system for detecting the potential mass locations on mammograms and simultaneously classified them into malignant or benign. The proposed methodology could identify breast masses in the pectoral muscle and the dense tissues.

A Computer-Aided Detection system methodology can help radiologists to categorize mass lesions based on CNN with fewer layers while not losing properties to achieve a good prediction and scale to massive datasets [

91]. The proposed CNN model contains four max-pooling, eight convolutional, and two fully connected layers. The model presented better results than the pre-trained nets, such as VGG16 and AlexNet.

Two pooling structures were proposed [

92], and deep CNNs oriented an end-to-end architecture. A global group-max pooling (GGP) structure and region-based group max pooling (RGP) structure were explored to solve the challenges in categorizing large mammographic images with small lesions. Finally, the diagnostic result is calculated by feeding the aggregated properties into the classification network.

Al-many et al. [

93] propose a novel computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) system based on

the You Only Look Once (YOLO). YOLO. YOLO Algorithm is used for mass detection; mass classifies into benign or malignant using a fully connected neural network (FCNN). It can also overcome challenges in breast cancer cases, like the mass in dense regions or pectoral muscles.

Gardezi et al. [

94] presented a classification technique for abnormal and normal mammogram tissues via a VGG-16 CNN. To assess the results, 10-fold cross-validation was used on SVM, simple logistics binary trees, and KNN (with k=1, 3, 5 classifiers).

Tsochatzidis et al. [

95] examine the performance of several deep convolutional neural networks, including AlexNet, VGG, GoogLeNet/Inception, and ResNets. They compare each network's performance in two training scenarios: from scratch and pre-trained weights. Experimental results demonstrate that fine-tuning a pre-trained network attains superior performance compared to training from scratch.

Carneiro et al. [

96] demonstrated the effectiveness of pre-training a deep learning model utilizing large computer vision training experiments. They fine-tuned this same model to classify mammogram exams. They also revealed that it is optional to register the segmentation maps and multi-view mammograms to create precise classification results via such a fine-tuned deep-learning model.

Table 1.

Summary of Studies on breast cancer classification.

Table 1.

Summary of Studies on breast cancer classification.

| References |

Year |

Methods |

Task performed |

Dataset |

Model Performance |

| Dhungel et al. [71] |

2017 |

Multi-scale Deep Belief nets (M-DBN), R-CNN, Random Forest Classifier |

Detection, Classification |

INbreast |

Detection accuracy: 90%,

Segmentation accuracy: 85%

Classification: Sensitivity: 98%, specificity:7% |

| Kooi et al. [72] |

2017 |

DCNN |

Detection |

Private |

Accuracy: 85.2% |

| Sun et al. [73] |

2017 |

Semi-supervised DCNN |

Detection |

Private |

Accuracy of 82.43% |

| Al-magnet al. [74] |

2018 |

Fully Connected Neural Networks (FCNNs), YOLO |

Detection Classification |

DDSM |

Detection Accuracy of 99.7% Classification Accuracy of 97% |

| Al-Antari et al. [46] |

2018 |

YOLO, FrCN, DCNN |

Detection, segmentation, classification |

IINbreast |

Detection: accuracy: 98.96%, MCC: 97.62%, and F1-score: 99.24%

MCC: 85.93%, F1-score: 92.69%, Segmentation: accuracy: 92.97%, Jaccard: 86.37%

Classification: accuracy: 95.64%, AUC: 94.78%, MCC of 89.91%, F1-score;e96.84% |

| Ribli et al. [75] |

2018 |

Faster R-CNN |

Detection, Classification |

INbreast |

Accuracy: 95% |

| Diniz et al. [76] |

2018 |

DCNN |

Detection |

DDSM |

Accuracy for Non-dense regions: 95.6%

Accuracy for Dense area: 97.72% |

| Khan et al. [77] |

2019 |

GoogleNet, VGGNet, ResNet |

Detection Classification |

Private |

Accuracy: 97.67% |

| Shen et al. [78] |

2019 |

Self-Paced Learning, Deep Active Learning |

Detection |

Private |

AUC: 92% |

| Savelli et al. [79] |

2020 |

Multi-Depth CNN |

Detection |

INbreast |

Sensitivity of 83.54% |

| Bruno [80] |

2020 |

Scale Invariant Feature Transform, AlexNet, PyramidNet |

Detection |

mini-MIS, SuReMaPP |

mini-MIAS: Sensitivity: 94%, specificity 91%

SuReMaPP: Sensitivity: 98%, specificity: 90% |

| Agarwal et al. [81] |

2020 |

Faster R-CNN |

Detection |

OPTIMAM, INbreast |

INbreast: TPR of 0.99±0.03 at 1.17 Private: TPR of 0.91±0.06 at 1.69 FPI

FPI for benign masses

FPI for malignant 0.85±0.08 at 1.0 |

| Al-antari et al. [82] |

2020 |

YOLO, feed-forward CNN, InceptionResNet-V2, and ResNet-50 |

DetectionClassification |

DDSM, INbreast |

Detection: Accuracy: DDSM: 99.17%, INbreast: 97.27%

F1-scores: DDSM 99.28%, INbreast 98.02%

Classification: Accuracies DDSM: 94.50%,

CNN: 95.83%,

, ResNet-50:

InceptionResNet-V2: 97.50%,INbreast:

CNN: 88.74%,

InceptionResNet-V2: 95.32%, ResNet-50: 92.55% |

| Li et al. [83] |

2020 |

Convolution Neural Network based on Bilateral image analysis |

Detection |

INbreast Private |

INbreast: 88% TPR with 1.12 FPs/I

Private: 0.85 TPR with 1.86 FPs/I. |

| Shen [84] |

2020 |

FCNN (Adversarial Learning) |

Detection |

INbreast, PrivateCBIS-DDSM |

INbreast: AUC-0.85, TPR@ 2.0FPI-0.87

Private: AUC:0.90, TPR@2.0 FPI-0.94 |

| Aly et al. [85] |

2020 |

ResNet, YOLO, and Inception (for feature extraction) |

Detection Classification |

INbreast |

Detection Accuracy: 89.4%

Classification: average precision of 94.2% for benign

84.6% for malignant |

| Xi et al. [86] |

2018 |

VGGNet, ResNet, AlexNet, GoogleNet |

Detection |

CBIS-DDSM |

Accuracy:

GoogleNet: 91.10% ResNet:91.80%

VGGNet: 92.53%, AlexNet: 91.23% |

| Deb et al. [87] |

2020 |

Pre-trained CNN models with Global Average Pooling DCNN |

Detection, Classification |

CBIS-DDSM |

AUC: VGG16: 0.70 InceptionV3: 0.74 InceptionResNetV2: 0.76 Xception: 0.75 NasNet: 0.73 MobileNet: 0.76 |

| Rahman et al. [88] |

2020 |

ResNet50, InceptionV3 |

Classification |

DDSM |

Accuracy: ResNet50: 85.71 InceptionV3: 79.6 |

| Zhang et al. [89] |

2018 |

AleXNet, ResNet50 |

Classification |

Private |

AUC: AlexNet: 0.6749 ResNet50: 0.6239 |

| Djebbar et al. [90] |

2019 |

YOLOv3 |

Detection Classification |

DDSM |

Accuracy: 97%

AUC: 96.45% |

| Gnanasekaran et al. [91] |

2020 |

AlexNet VGGNet DCNN |

Classification |

DDSM, MIAS, Private |

AUC: MIAS: 0.85 DDSM: 0.96, Private: 0.94

Accuracy: MIAS: 92.54 DDSM: 96.47 Private: 95 |

| Shu et al. [92] |

2020 |

DCNN with Region-based Pooling Structures |

Classification |

INbreast CBIS-DDSM |

Accuracy: INbreast: 0.923 CBIS-DDSM: 0. 762

AUC: INbreast: 0.934 CBIS-DDSM: 0.838 |

| Al-masni et al. [93] |

2017 |

YOLO |

Detection Classification |

DDSM |

Detection Accuracy: 96.33%

Classification Accuracy: 85.52% |

| Gardezi et al. [94] |

2017 |

VGGNet |

Classification |

IRMA |

AUC:1.0 |

| Tsochatzidis et al. [95] |

2019 |

AlexNet, GoogleNet, VGGNet, InceptionV2, ResNet |

Classification |

DDSM-400 CBIS- DDSM |

ResNet outperforms the rest of the pre-trained networks with an accuracy of DDSM-400: 0.785 and CBIS-DDSM: 0.755 |

| Carneiro et al. [96] |

2017 |

Pre-trained CNN Models |

Classification |

INbreast DDSM |

AUC:0.9 |

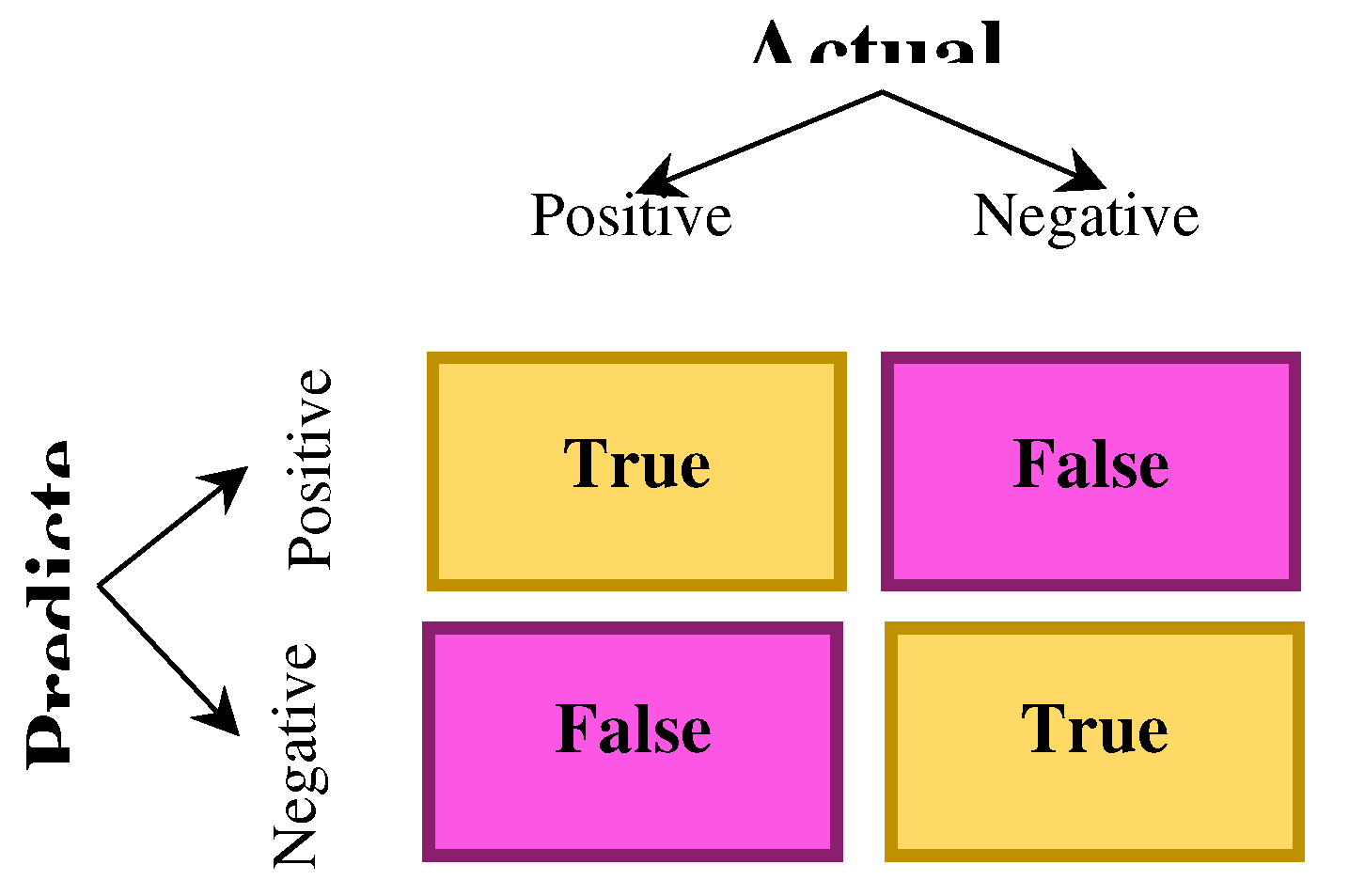

6. Assessment Metrics

Many criteria have been proposed to effectively measure the performance of CAD systems for cancer detection in medical images. There must be convincing reasons for choosing evaluation criteria because how to measure and compare the effectiveness of methods completely depends on your chosen criteria. Also, the selected criteria completely influence how to weigh the importance of different features in the results. This section presents some popular metrics to evaluate these methods' performance.

A confusion matrix is an N × N matrix to assess a classification model's performance, in which N represents the number of target groups. The actual target values are compared with the matrix and those estimated by the model. For a binary classification problem, a 2 x 2 matrix will exist (

Figure 11) with four values

Figure 11.

2×2 confusion matrix.

Figure 11.

2×2 confusion matrix.

Accuracy can measure the accurate prediction made by the classifier. It is the ratio between the total number of predictions and the number of correct predictions. The accuracy can be defined as

For imbalanced classes, the accuracy metric needs to be more suitable. Accuracy can be used to assess the classification problems which are not skewed and are well balanced, with no class imbalance.

Precision can measure the correctness obtained in true prediction. In other words, it shows the number of positive predictions from all the total positive predictions as follows:

Precision is a useful metric when there is a deeper concern about False Positive than False Negatives.

The recall is a measure of correctly predicted actual observations, i.e., the number of observations of positive class predicted as positive. It is also called sensitivity, which is shown as

The recall is a valid assessment metric for capturing as many positives as possible.

The proportion of true negatives is measured by

the Specificity identified correctly by the model. It shows another proportion of actual negative estimated as positive, known as false positive. The specificity can be defined as

Sensitivity measures the correct identification of instances of the positive class by the model, while specificity measures how well the model can correctly identify cases of the negative type.

The F1-Score shows the harmonic mean of precision and recall as a number between 0 and 1. Unlike simple averages, the harmonic mean is sued due to non-sensitivity to extremely large values.

F1-score sort maintains a balance between the recall and precision for a classifier. For lower precision, the F1 is common, and for lower recall, the F1 score is also low.

Pixel Accuracy is a semantic segmentation metric representing the percentage of the pixels in the image classified properly. It is obtained as:

Sometimes, misleading results are obtained by this for the smaller class representation within the image, as the measure will be biased mainly in identifying negative cases (for lack of class).

Dice score can assess the similarity between the ground truth (GT) segmentation mask and an estimated segmentation mask. The Dice score ranges from 0 (no overlap) to 1 (perfect overlap).

Where A and B represent GT and predicted segmentation maps, respectively.

Volumetric overlap error (VOE) is calculated using the ratio between union and intersection between two sets of segmentations (A and B). VOE complements the Jaccard index; it is defined as follows:

7. Challenge and Future Work

Recently, different Deep Convolutional Neural Networks methods have been used widely for diagnosing and screening breast cancer, which have outstanding performance. However, there are still challenges in research other than class imbalance and small data sets requiring further investigation. This section discusses potential future research directions to improve the results of the CAD system for breast cancer diagnosis.

Network architecture design: Improving network structure design affects CAD systems' performance and can be extended to other applications. The manual design of the model structure needs rich experiences, so the gradual replacement of Neural Architecture Search (NAS) is inevitable.NAS aims to discover the best architecture for a neural network for a specific need. Essentially, NAS takes the procedure of a human manually tweaking a neural network and learning better performance. It automates this task for discovering more complex architectures. Nevertheless, searching a large network directly is difficult owing to GPU limitations and memory. Thus, the future trend needs to include manual design and NAS technology. Initially, a backbone network is manually designed, and then NAS, before training, searches the small network modules.

Transfer learning: Limited access to annotated medical image data is a considerable problem explaining the restrictions of developing robust deep learning models. However, building a labeled dataset of sufficient size can be very expensive. Therefore, using pre-trained deep learning models on natural images is one of the future research directions. Furthermore, transfer learning is a key method for obtaining unsupervised medical image segmentation. By transfer learning, model parameters (or information learned by the model) can be shared with the new model, thus increasing the learning efficiency of the model. Therefore, the problem of inadequate labeling data can be solved by transfer learning.

Interactive image segmentation [

97] based on deep learning can decrease the user time and the number of user interactions owing to the superior performance of deep learning, which shows wider application prospects.

Graph Convolutional Neural Network: CNN has attained significant success in the last decade, especially in breast cancer diagnosis. However, many real-world data have underlying graph structures, which are non-Euclidean, and CNN has some limitations in non-Euclidean data. The non-regularity of data structures has resulted in the current advancements in Graph Convolutional Neural Networks (GCCN) [

97]. GCCNs are the generalized version of CNN acting on data with fundamental non-regular structures. Though, mammography images highly include heterogeneous textures with difficult classification solely based on their morphological shapes. Thus, it is essential to consider their dependencies and geometric relations [98]. Therefore, graph-based models can proficiently circumvent the availability restrictions of labeled mammograms by privileging the inherited dependencies and connections in data to reach improved accuracy with lower branded instances.

Despite all recent methods, detecting and classifying breast cancer in mammography with minimal needed annotated data while considering the pattern and relationship of the texture properties is still challenging. There is no semi-supervised or self-supervised graph-based method for processing the high-resolution mammogram images and performing multi-classification of the anomalous areas with less annotated data for the training procedure. The relations and features embedded in the graph orient the learning capacities of graph-based models. Hence, a well-engineered preprocess is required for transforming the raw data of digitized mammogram images into a rich relational graph network.

Medical Transformer: Convolution architectures lack learning long-range spatial dependencies in the image owing to inherent inductive biases. Recently, Transformer-based architectures could encode long-range dependencies by replacing convolution operations, leveraging the self-attention mechanism in the encoder-decoder structure, and learning highly expressive representations. Though, if transformers substitute all convolution operators in machine vision tasks, several problems occur, including high memory usage and computational cost. Considering that the local information of the image is extracted by the convolution block and the transformer depicts the complex relations between different spatial positions more, the combination of the transformer and CNN can result in better results.

8. Conclusions

The emergence of deep convolutional neural networks has attained significant progress in various domains, including CAD systems, especially breast cancer diagnosis. In the present work, we reviewed the recent advances of CNN-based deep learning techniques in breast cancer CAD systems. We also discussed in this study common CNN architectures to state these applications. A comparative analysis is presented in the paper based on the configuration and main characteristics of this model. The limitations and strengths of these pre-trained architectures direct researchers in this field in choosing the right model for their applications. This work highlights the main challenges of CNNs for mammography image training. Methods for improving model generalization are also presented. Although CNNs have achieved state-of-the-art achievements in breast cancer diagnosis and other image-processing tasks, several research questions remain to be explored further.

References

- J. Ferlay, I. Soerjomataram, R. Dikshit, S. Eser, C. Mathers, M. Rebelo, D. M. Parkin, D. Forman and F. Bray, "Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012," International journal of cancer 136 (5) (2015), vol. 136, no. 5, p. E359–E386, 2015.

- B. Hela, M. Hela, H. Kamel, B. Sana and M. Najla, "Breast cancer detection: a review on mammograms analysis techniques," in In 10th International Multi-Conferences on Systems, Signals & Devices 2013 (SSD13), Hammamet, Tunisia. , 2013.

- S. Misra, N. L. Solomon, F. L. Moffat and L. G. Koniaris, "Screening Criteria for Breast Cancer," Advances in Surgery, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 87-100, 2010. [CrossRef]

- H. G. Welch,. C. Prorok, . J. O'Malley and . S. Kramer, "Breast-Cancer Tumor Size, Overdiagnosis, and Mammography Screening Effectiveness," New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), vol. 375, no. 15, pp. 1438-1447, 2016.

- B. C. Patel and G. R. Sinha, "Abnormality Detection and Classification in Computer-Aided Diagnosis (CAD) of Breast Cancer Images," Journal of Medical Imaging and Health Informatics, vol. 4, no. 6, pp. 881-885(5), 2014. [CrossRef]

- B. A. F. H. a. S. T. B. B. A. F. H. a. S. T. Y. Benhammou, "Breakhis based breast cancer automatic diagnosis using deep learning: Taxonomy, survey and insights," Neurocomputing, vol. 375, pp. 9-24, 2020.

- E. Wulczyn, D. F. Steiner, Z. Xu, A. Sadhwani, H. Wang, I. Flament-Auvigne, C. H. Mermel, P.-H. C. Chen, Y. Liu and M. C. Stumpe, "Deep learning-based survival prediction for multiple cancer types using histopathology images vol. 15, no. 6, p," PLoS One, vol. 15, no. 6, p. p. e0233678, 2020..

- D. F. Y. L. P.-H. C. C. E. W. F. T. N. O. J. L. S. A. M. J. H. W. e. a. K. Nagpal, "Development and validation of a deep learning algorithm for improving gleason scoring of prostate cancer," NPJ digital medicine, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 1-10, 2019.

- A. Jalalian, S. B. T. Mashohor, H. R. Mahmud, M. I. B. Saripan, A. R. B. Ramli and B. Karasfi, "Computer-aided detection/ diagnosis of breast cancer in mammography and ultrasound: a review," Cliniacl Imaging, vol. 37, no. 3, pp. 420-426, 2013. [CrossRef]

- V. M., "Breast cancer screening methods: a review of the evidence," Health Care Women Int. , vol. 24, no. 9, p. 773-793, 2003.

- S. Tangaro, R. Bellotti, F. D. Carlo, G. Gargano, E. Lattanzio, P. Monno, R. Massafra, P. Delogu, M. E. Fantacci, A. Retico, M. Bazzocchi, S. Bagnasco, P. Cerello, S. C. Cheran, E. L. Torres, E. Zanon, A. Lauria, A. Sodano, D. Cascio, F. Fauci, R. Magro, G. Raso, R. Ienzi and U. B, "MAGIC-5: an Italian mammographic database of digitised images for research," Radiol Med, vol. 113, no. 4, p. 477-485, 2008. [CrossRef]

- S. H. Matheus BRN, "Online mammographic images database for development and comparison of CAD schemes," J Digit Imaging, vol. 24, no. 3, p. 500-506, 2011.

- C. Moreira, I. Amaral, I. Domingues, A. Cardoso, M. J. Cardoso and J. S. Cardoso, "INbreast: toward a full-field digital mammographic database," Acad Radiol., vol. 19, no. 2, p. 236-248, 2012. [CrossRef]

- M. H. KB, K. D and R. M. P. Jr., "The digital database for screening mammography," in In Proceedings of the 5th international workshop on digital mammography, 2000.

- R. J. Hooley, M. A. Durand and L. E. Philpotts, "A curated mammography data set for use in computer-aided detection and diagnosis research," Scientific Data., vol. 4, 2017.

- M. A. G. López, N. G. d. Posada, D. C. Moura, R. R. Pollán, J. M. F. Valiente, C. S. Ortega, M. R. d. Solar, G. D. Herrero, I. M. P. Ramos, J. P. Loureiro and T. C. Fernandes, "BCDR: A Breast Cancer Digital Repository," in In 15th International conference on experimental mechanics (Vol. 1215), Porto, Portugal, 2017.

- Aldo Badano, C. G. Graff, Andreu Badal and e. al., "Evaluation of Digital Breast Tomosynthesis as Replacement of Full-Field Digital Mammography Using an In Silico Imaging Trial," JAMA Network Ope, vol. 1, no. 7, p. e185474, 2018.

- M. D. Halling-Brown, L. M. Warren, D. Ward, E. Lewis, A. Mackenzie, M. G. Wallis, L. Wilkinson, R. M. Given-Wilson, R. McAvinchey and K. C. Young, "OPTIMAM mammography image database: a large scale resource of mammography images and clinical data.," Radiology: Artificial Intelligence, vol. 3, no. 1, p. e200103, 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. Yamashita, M. Nishio, R. K. G. Do and K. Togashi, "Convolutional neural networks: an overview and application in radiology," Insights Imaging, vol. 9, no. 4, p. 611–629, 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. Krizhevsky, I. Sutskever and G. E. Hinton, "Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks," Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 25, p. 1097–1105, 2012.

- C. Szegedy, W. Liu, Y. Jia, P. Sermanet, S. Reed, D. Anguelov, D. Erhan, V. Vanhoucke and A. Rabinovich, "Going deeper with convolutions," in In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2015.

- K. Simonyan and A. Zisserman, "Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition," arXiv preprint arXiv:14091556, 2014.

- A. Khan, A. Sohail, U. Zahoora and A. S. Qureshi, "A survey of the recent architectures of deep convolutional neural networks," Artificial Intelligence Review, vol. 53, no. 8, p. 5455–5516, 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. He, X. Zhang, S. Ren and J. Sun, "Deep residual learning for image recognition," in in Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2016.

- G. Huang, Z. Liu, L. v. d. Maaten and K. Q. Weinberger, "Densely Connected Convolutional Networks," in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, , 21-26 July 2017,, Honolulu, 2017.

- F. Chollet, "Xception: deep learning with depthwise separable convolutions," in Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition pp, 2017.

- O. Ronneberger, P. Fischer and T. Brox, "U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation," in In proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI), 2015.

- K. He, G. Gkioxari, P. Dollár and R. Girshick, "Mask R-CNN," in In Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2017.

- S. Ren, K. He, R. Girshick and J. Sun, "Faster r-cnn: towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks," IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, vol. 39, no. 6, pp. 1137-1149, 2015.

- J. Redmon, S. Divvala, R. Girshick and A. Farhadi, "You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection," in 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2016.

- K. Ganesan, U. R. Acharya, K. C. Chua, L. C. Min and K. T. Abraham, "Pectoral muscle segmentation: a review," Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 48-57, 2013.

- N. V. Slavine, S. Seiler, T. J. Blackburn and R. E. Lenkinski, "Image enhancement method for digital mammography," Medical imaging 2018: image processing, vol. 10574, 2018.

- M. Al-Bayati and A. El-Zaart, "Mammogram images thresholding for breast cancer detection using different thresholding methods," Advances in Breast Cancer Research, vol. 2, pp. 72-77, 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. J. George and S. P. Sankar, "Efficient preprocessing filters and mass segmentation techniques for mammogram images," in IEEE international conference on circuits and systems (ICCS), Thiruvananthapuram, India, 2017.

- L. S. Varughese and A. J, "A study of region based segmentation methods for mammograms," IJRET: International Journal of Research in Engineering and Technology, vol. 02, p. 421–425, 2013.

- M. M. Eltoukhy, I. Faye and B. B. Samir, "Curvelet based feature extraction method for breast cancer diagnosis in digital mammogram," in International conference on intelligent and advanced systems, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2010.

- M. M. Eltoukhy, I. Faye and B. B. Samir, "A statistical based feature extraction method for breast cancer diagnosis in digital mammogram using multiresolution representation," Computers in Biology and Medicine, vol. 42, no. 1, pp. 123-128, 2012. [CrossRef]

- D. Kulkarni, S. M. Bhagyashree and G. R. Udupi, "Texture Analysis of Mammographic images," International Journal of Computer Applications, vol. 5, no. 6, p. 12–17, 2010.

- R. Llobet, R. Paredes and J. C. Pérez-Cortés , "Comparison of Feature Extraction Methods for Breast Cancer Detection," Pattern Recognition and Image Analysis, vol. 3523, p. 495–502, 2005.

- C. Muramatsu and T. H. T. E. H. Fujita, "Breast mass classification on mammograms using radial local ternary patterns," Computers in Biology and Medicine, vol. 72, pp. 43-53, 2016.

- N. I. Yassin, S. Omran, E. M. E. Houby and H. Allam, "Machine learning techniques for breast cancer computer aided diagnosis using different image modalities: A systematic review," Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, vol. 156, pp. 25-45, 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. Li, X. Meng, T. Wang, Y. Tang and Y. Yin, "Breast masses in mammography classification with local contour features," BioMedical Engineering OnLine, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 44-55, 2017. [CrossRef]

- K. Zuiderveld, "Contrast limited adaptive histogram equalization," Graphics gems, pp. 474-485, 1994.

- N. Dhungel, G. Carneiro and A. P. Bradley, "Tree reweighted belief propagation using deep learning potentials for mass segmentation from mammograms," in IEEE 12th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging, Brooklyn; NY; USA, 2015.

- W. Zhu, X. Xiang, T. D. Tran, G. D. Hager and X. Xie, "Adversarial deep structured nets for mass segmentation from mammograms.," in IEEE 15th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI) : , Washington, DC, USA, 2018.

- M. A. Al-antaria, M. A. Al-masnia, M.-T. Choi, S.-M. Han and T.-S. Kim, "A fully integrated computer-aided diagnosis system for digital X-ray mammograms via deep learning detection, segmentation, and classification," International Journal of Medical Informatics, vol. 117, p. 44–54, 2018.

- H. Li, D. Chen, B. Nailon, M. Davies and D. Laurenson, "Improved breast mass segmentation in mammograms with conditional residual u-net," Image Analysis for Moving Organ, Breast, and Thoracic Images, vol. 11040, p. 81–89, 2018.

- A. Rampun, K. López-Linares, P. J. Morrow, B. W. Scotney, H. Wang, I. G. Ocaña, G. Maclair, R. Zwiggelaar, M. A. G. Ballester and v. Macía, "Breast pectoral muscle segmentation in mammograms using a modified holistically-nested edge detection network," Medical Image Analysis , vol. 57, pp. 1-17, 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. Shen, C. Gou, F.-Y. Wang, Z. He and W. Chen, " Learning from adversarial medical images for X-ray breast mass segmentation," Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, vol. 180, p. 105012, 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. Wang, Y. Ma, W. Sun, Y. Guo, W. Wang, Y. Qi and X. Gong, "Multi-level nested pyramid network for mass segmentation in mammograms," Neurocomputing, vol. 363, pp. 313-320, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Li, M. Dong, G. Du and X. Mu, "Attention dense-u-net for automatic breast mass segmentation in digital mammogram," IEEE Access, vol. 7, p. 59037–59047, 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. Shen, C. Gou, J. Wang and F.-Y. Wang, "Simultaneous segmentation and classification of mass region from mammograms using a mixed-supervision guided deep model," IEEE Signal Processing Letters , vol. 27, p. 196–200, 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. Abdelhafiz, S. Nabavi, R. Ammar, C. Yang and J. Bi, "Residual deep learning system for mass segmentation and classification in mammography," in BCB '19: Proceedings of the 10th ACM International Conference on Bioinformatics, Computational Biology and Health Informatics, Niagara Falls; NY; USA, 2019.