1. Introduction

A few investigations (e.g., Eby et al. [

1] and Lussier et al. [

2]) have explored the characteristics and formation mechanism of shocked quartz grains resulting from the 1945 Trinity nuclear detonation at the Alamogordo Bombing Range, New Mexico. These studies revealed the presence of linear fractures considered to result from the high shock pressures of these detonations, leading Lussier et al. [

2] to conclude that they may represent the initial deformational feature of quartz formed in a progression of increasing shock pressures. In another investigation related to the 1945 Hiroshima nuclear detonation, Wannier et al. [

3] investigated glassy spherules but found that any shocked quartz grains that may have been present in the melt had been fully amorphized due to the extremely high temperatures.

Several laboratory experiments have investigated the shock-related transformation of quartz to amorphous silica at pressures of <10 GPa. In one study, Ebert et al. [

4] reported that the experimental amorphization of rocks occurs mainly upon decompression of shocked material when the temperature remains high as the pressure decreases. In quartz grains experimentally shocked at 5 to 17.5 GPa, Fazio et al. [

5] observed glass veins composed of amorphous silica that extend across several microns in length and that are generally thicker than 50 nm. Wilk et al. [

6] found amorphous silica in experimentally shocked rocks called shatter cones that formed at low shock pressures of 0.5–5 GPa. In addition, Carl et al. [

7] conducted experiments demonstrating that extensive amorphization of quartz begins at ~10 GPa. Regarding the importance of amorphous silica in studies of shock metamorphism, French and Koeberl [

8] wrote “amorphous or ‘glassy’ phases ... constitute another set of unique and distinctive criteria for the recognition of shock-metamorphosed rocks....” Similarly, Bohor et al. [

9] wrote “the formation of quartz glass within fractures ... allows a definitive distinction ... between these shock PDFs and the glass-free dislocation trails marking slow tectonic deformation.”

Even with these pioneering investigations, numerous questions remain about the formation of shock fractures and amorphous silica associated with nuclear airbursts. Is the process of formation similar to that of planar fractures (PFs) and planar deformation features (PDFs) found in shocked quartz grains associated with cosmic impact craters? Are these features similar to or different from tectonic lamellae found in some deformed metamorphic rocks? In this contribution, we explore these and other questions.

We investigated quartz grains exposed to near-surface nuclear airbursts, in which the blast wave and fireball intersected the ground surface. For comparison, we also investigated shocked quartz grains from Arizona’s Meteor Crater, a relatively small (1.2-km-wide) impact cratering event. Our objective was to compare quartz grains exposed to pressures and temperatures associated with these two different types of high-temperature, high-pressure events. The hypothesis we explored is that low-altitude nuclear airbursts marked by relatively-low pressures can produce shock fractures in quartz grains that became filled with amorphous silica. Secondarily, we investigated whether these characteristic shock fractures in quartz grains formed similarly to those during crater-forming impacts, such as at Meteor Crater.

1.1. Shock metamorphism in quartz.

Previous studies of impact cratering events have described relatively low shock fractures in quartz and given them various names, including shock extension fractures (SEFs) [

10,

11,

12,

13]; shock fractures [

14,

15]; and vermicular (i.e., wormlike) microfractures [

11,

13,

16]. Here, we adopt the term “shock fractures” to denote non-planar, shock-induced microfractures in quartz. We also use the term “amorphous silica” interchangeably with “glass.”

Multiple studies have reported characteristics of the different types of shock metamorphism observed in quartz, including planar deformation features (PDFs) [

8,

9,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26], planar fractures (PFs) [

8,

27], tectonic deformation lamellae (DLs) [

8,

9,

14,

19,

21,

24,

28,

29,

30,

31], and sub-planar shock micro-fractures [

26,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. Here, the term “lamellae” is used to denote typically closed high-pressure stress features in quartz, whereas “fractures” denote typically open lower-pressure stress features.

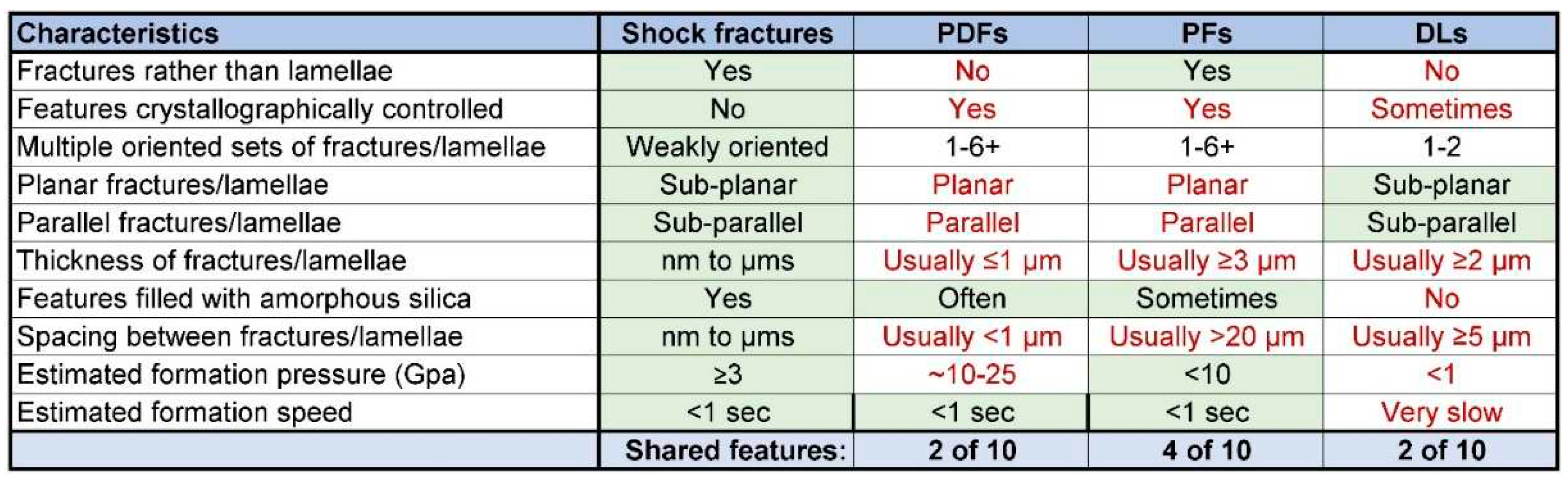

Table 1 compares some of the commonalities and differences among the types of shock features. Our analysis of this previous work shows that shock fractures share 2 of 10 characteristics with PDFs, 4 of 10 are shared with PFs, and 2 of 10 with DLs. Thus, shock fractures are substantially different from the other shock metamorphic features: PDFs, PFs, and DLs. The most important reported differences are that shock fractures are typically sub-planar, non-parallel, not crystallographically oriented, and form at lower shock pressures.

1.2. Key analytical studies of shock fractures.

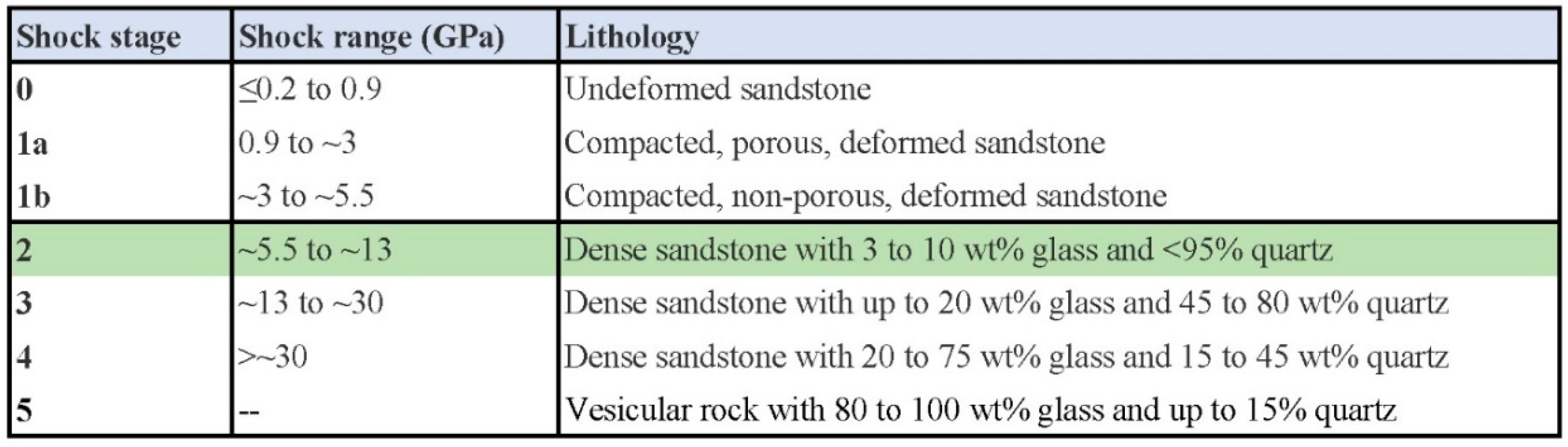

Kieffer [

32] performed analyses of shocked sandstone from Meteor Crater and concluded that impact-related microfractures began to form at 5.5 GPa (

Table 1, adapted from

Table 2 of ref. [

32]). Later, Kieffer et al. [

33] described rocks weakly shocked at <10 GPa and displaying fractured quartz grains that were partially transformed into amorphous silica. In moderately and strongly shocked rocks, they observed a process called “jetting,” in which molten quartz was extruded under pressure into shock-formed fractures in the grains.

Christie et al. [

18] performed laboratory experiments on quartz by generating slow-strain conditions to produce glassy lamellae using a confining pressure of 1.5 GPa and a stress differential of up to 3.6 GPa. Their experiment attempted to replicate the features known to form in quartz grains during tectonic motion along fault planes. They reported the presence of deformation lamellae closely associated with amorphous silica at low pressures under laboratory conditions. Their experiment suggests that glass-filled lamellae may form in quartz at pressures as low as 1.5 GPa.

Importantly, Christie et al. [

18] did not report amorphous silica associated with naturally-formed tectonic deformation lamellae in quartz [

19], suggesting that their laboratory experiments did not replicate natural, real-world conditions. Co-author H.-R.W. has performed multiple analyses of tectonic lamellae and notably, never observed amorphous silica associated with tectonic lamellae in quartz grains [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44]. In addition, Houser et al. [

45] described finding tectonically-formed, nano- to micro-scale amorphous silica particles and nanofilms along active fault planes, but they reported no quartz grains with fractures containing amorphous silica. Multiple studies have observed amorphous silica within fractures, but only in impact-related shocked quartz and not in tectonic deformation lamellae [

9,

14,

19].

For the Trinity nuclear airburst (24.8 ± 2 kiloton (kt); previously estimated at 20-22 kt [

1]), numerous studies determined the requisite formation pressures for various minerals: ~8 to <10 GPa for shocked quartz [

1,

2]; ~7-10 GPa for shocked zircon [

46]; <25–60 GPa for vesiculated feldspar [

47]; >8 GPa based on the fractionation of zinc [

48]; and 5-8 GPa based on quasi-crystalline minerals in trinitite [

49].

Laboratory experiments by Kowitz et al. [

11,

15,

50] investigated the shock alteration of quartz grains when a steel plate was explosively driven into cylinders of quartz-rich sandstone at pressures of ~5, 7.5, 10, and 12.5 GPa (

Figure 1). Visible shock fractures and amorphous silica (~1.6 wt%) first appeared at ~5 GPa [

11]. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images reveal shock fractures that they called “sub-planar, intra-granular fractures [

11].” This result is important because most shocked material within small impact craters forms within this lower shock pressure range. The combined shock effects from studies by Kieffer [

32,

33] and Kowitz et al. [

11,

15,

50] are summarized in

Table 2.

2. Methods

Samples were collected as described in the Appendix, Methods-Samples. Candidate grains were processed as described in the Appendix, Methods-Processing Steps. Selected grains were investigated using multiple standard analytical techniques and preparation methods, as described here and in the Appendix, Methods-Analytical Techniques. The Appendix also lists the locations of laboratories where analyses were performed.

2.1. Sample Locations

2.1.1. Meteor Crater, Arizona

This site, also known as the Barringer Crater, is a 1.2-km-wide hypervelocity impact feature located east of Flagstaff, Arizona [

51]. The 180-m-deep crater is surrounded by an ejecta blanket that is elevated ~30 to 60 m above the local surface (

Figure 2). The 50,000-year-old impact crater is estimated to have been produced by an ~50-m-wide bolide, now known as the Canyon Diablo meteorite [

51]. The bedrock inside Meteor Crater contains shocked quartz with high-pressure planar deformation features (PDFs) [

32,

51], but we limited our study to shock-fractured quartz grains embedded in samples of meltglass that had been ejected from the crater. They were collected in 1966 by Bunch [

51] on the rim ~500 m north of the center of the crater at ~35.032206° N, 111.023988° W.

2.1.2. Russia, Joe-1/4 nuclear test, near-surface airburst

The first Soviet nuclear bomb test, nicknamed “Joe 1” by the Americans, was conducted in 1949 in Kazakhstan (~50.590664° N, 77.847319° E). The ~20-kt nuclear test was detonated aerially on a 30-m-tall tower (

Figure 3). “Joe 4” is the American nickname for a 400-kt Russian test that was detonated on a 30-m-tall tower at the same location in 1953. This study analyzed fractured quartz grains in loose sediment and embedded in multi-mm-sized fragments of meltglass. A surface sediment sample was collected by Byron Ristvet on 9/1/2012 at ~100 meters from ground zero for both tests. It could not be determined which nuclear test produced the sample that was collected and investigated.

2.1.3. U.S., Trinity nuclear test, near-surface airburst

The Trinity nuclear bomb was detonated aerially in 1945 at the Alamogordo Bombing Range, New Mexico on a tower at an altitude of 30 m [

1] with an estimated energy of 24.8 kilotons (kt) of TNT equivalent [

52]. The fireball was ~300-m-wide at ~25 ms after detonation (

Figure 4A). A blast zone of the ejected materials extended more than 400 m radially from ground zero [

1]. The airburst formed a crater that was ~80 m in diameter [

53] and ~1.4 m deep [

54] (

Figure 4B). This study analyzed fractured quartz grains embedded in meltglass, called trinitite, which was collected by co-author, R.E.H., on 9/30/2011 from the ground surface ~400 m north of ground zero (33.68100° N, 106.4756° W). R.E.H. also processed another sample (JIE) of loose quartz grains found on an anthill near ground zero, collected by Jim Eckles in 2003.

2.2. Analytical techniques

This investigation has required a robust series of analyses using a wide range of sophisticated, high-resolution techniques.

Optical transmission microscopy (OPT). For this study, we made polished thin sections of quartz grains and meltglass to search for potentially shocked quartz grains at three sites. For Meteor Crater, 36 quartz grains were analyzed at concentrations of 600 grains/cm

2 (Appendix,

Figure S1); for the Joe-1/4 site, 24 grains at 150/cm

2 (Appendix,

Figure S2) and for Trinity, 42 grains at 700/cm

2 (Appendix,

Figure S3).

Epi-illumination microscopy (EPI). This optical technique uses reflected light to image the surfaces of the grains investigated.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Standard practices were used for SEM analyses.

Scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM). STEM images were acquired on focused ion beam foils. Standard practices were used for STEM analyses.

Focused ion beam milling (FIB). This is a technique to prepare a thin specimen (avg: ~175 nanometers (nm) thick) by milling a quartz grain with focused gallium (Ga) ions. The resulting specimen, called a foil, is then analyzed using TEM.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM). TEM images were also acquired on the FIB foils. Standard practices were used for TEM analyses.

Fast-Fourier transform (FFT). The diffraction characteristics of the FIB foils were investigated using FFT, an image processing technique for analyzing high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) images in reciprocal space. The FFT algorithm calculates the frequency distribution of pixel intensities in an HRTEM image, and then, any periodicity is displayed as spots in an output image, thus revealing the crystal’s structure. HRTEM and FFT allow the measurement of interatomic spacings, which are known as d-spacings and are measured in nm or angstroms (Å).

TEM energy dispersive spectroscopy (TEM-EDS). Standard practices were used for TEM analyses.

Cathodoluminescence (CL). We used SEM-mounted CL to explore the luminescence properties of the same areas of quartz grains as imaged with SEM. Standard practices were used for CL analyses.

SEM energy dispersive spectroscopy (SEM-EDS). SEM-based EDS exposes a specimen to an electron beam that generates X-rays that vary according to the elements present in the sample.

Electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD). EBSD is an SEM-based analytical technique, in which an electron beam scans across a crystalline sample tilted at 70°. The diffracted electrons produce what are called Kikuchi patterns that reveal the microstructural properties of the sample. EBSD was also used to determine the quartz grains’ crystallographic orientations.

At the University of California, Berkeley, SEM analyses were performed with a Zeiss EVO for imaging operated at 20 kV and EDS analyses used an EDAX-AMETEK spectrometer with corresponding Genesis software. EBSD mapping used a Digiview detector and TSL-OIM software. At the University of Utah, a Velocity Super EBSD camera (EDAX, Pleasanton, CA) was used to collect diffracted electrons for crystal structure analysis.

Micro-Raman. Although we attempted investigations using micro-Raman, the fracturing and extensive amorphization of quartz grains precluded acquiring usable Raman spectra.

Universal stage. We also attempted the analysis of shock fractures using the universal stage but the results were poor because most fractures are non-planar and not oriented along quartz’s crystallographic planes.

Figures. Most Figures were globally adjusted for balance, brightness, contrast, and sharpness, and some images were cropped to fit the space. A few images were rotated for clarity and the legends and scale bars were repositioned at the bottom of the Figures. For RGB images and some resized images, legends sometimes became unreadable and so, they were replaced with the original legible legend. EDS Figures were composited from multiple printouts. No data within the Figures were changed or obscured in making any adjustments.

3. Results and Interpretations

We employed ten analytical techniques to investigate shock fractures containing amorphous silica, as follows:

Optical transmission microscopy (OPT). Using this technique, we observed that >50% of the grains examined for each of the three sites displayed shock fractures. Representative optical and SEM images of quartz grains are shown in

Figure 5. These images are comparable to those from the experimental study shown in

Figure 1. Most displayed a single set of shock fractures, meaning all are oriented in approximately the same direction. However, a few grains display multiple sets that are oriented along different axes.

Some grains with shock fractures display undulose extinction (

Figure 5), defined as a grain’s failure to become uniformly extinct (dark) when rotated under crossed polars. Instead, the grains exhibit waves of extinction that are typically oriented perpendicular to the trend of the grain’s lamellae. Kowitz et al. [

15] reported that the extinction of quartz grains is sharp in unshocked sandstone. In contrast, they noted that undulose extinction becomes apparent in sandstone shocked to 5 GPa, transitioning to weak but still prominent mosaicism (i.e., irregular patchwork extinction) (

Figure 5).

Epi-illumination microscopy (EPI). This analytical technique is particularly useful in viewing HF-etched quartz grains (

Figure 5) that display previously hidden glass-filled fractures. Multiple studies [

9,

14,

19,

21,

55,

56] have demonstrated the usefulness of performing analyses after etching quartz grains with HF. According to Gratz et al. [

19], the HF-etching removes some amorphous silica filling the shock features, allowing for the “unambiguous visual distinction between glass-filled PDFs and glass-free tectonic deformation arrays in quartz.” Other techniques are necessary to identify and characterize the filled material as amorphous silica, a key indicator of shock metamorphism [

9,

19].

In contrast, lamellae in tectonically-deformed grains are not visible in EPI as open fractures but may appear as shallow, closed depressions without filling material. Our investigations of six tectonically-deformed quartz grains and six unshocked natural quartz grains reveal that none contain amorphous silica. See Appendix,

Figures S4 and S5.

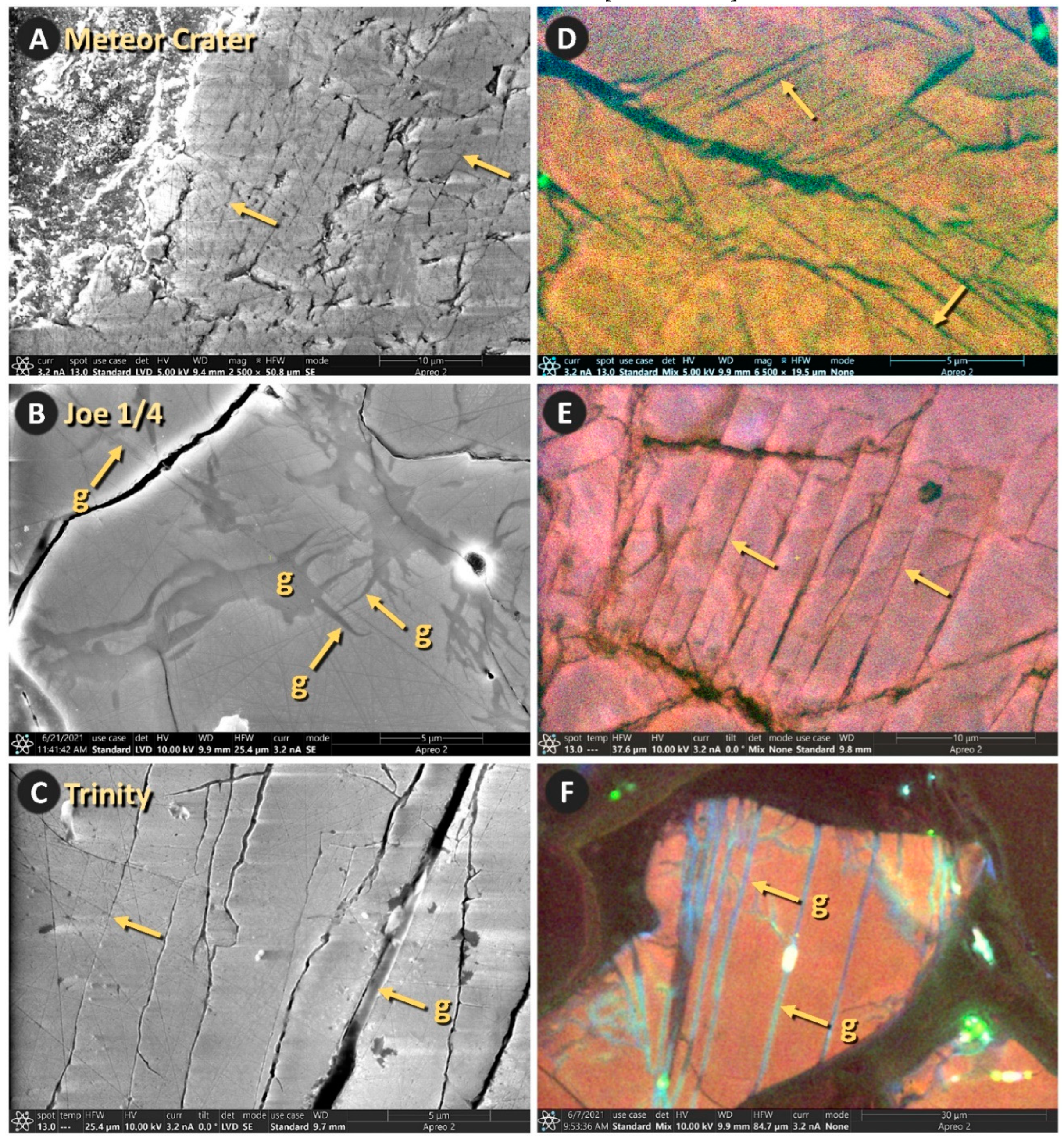

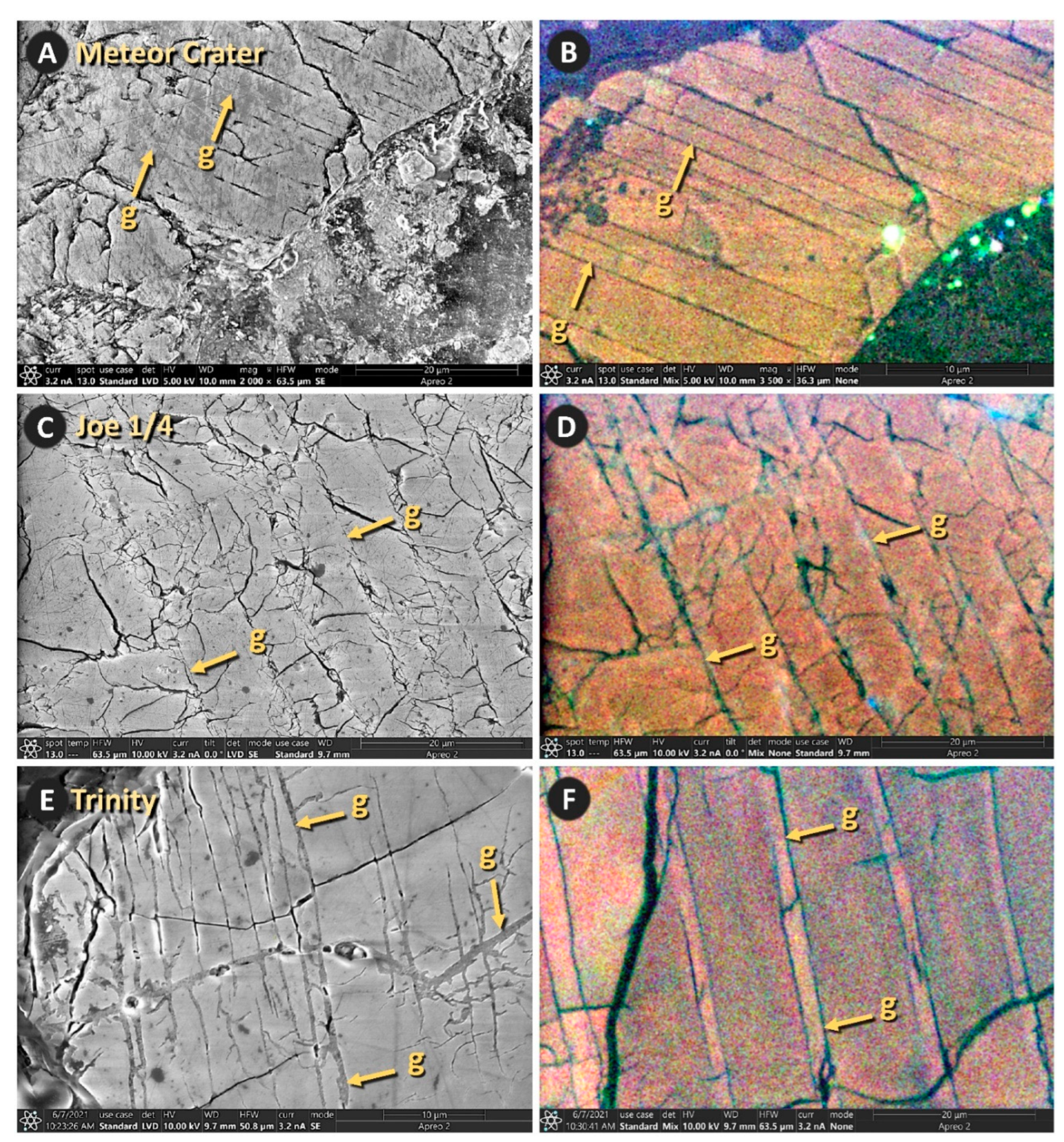

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Analyses using SEM revealed filled fractures in quartz grains that appeared mostly as linear features, although some were curvilinear. Here, too, other analyses are necessary to identify and characterize the material filling the fractures.

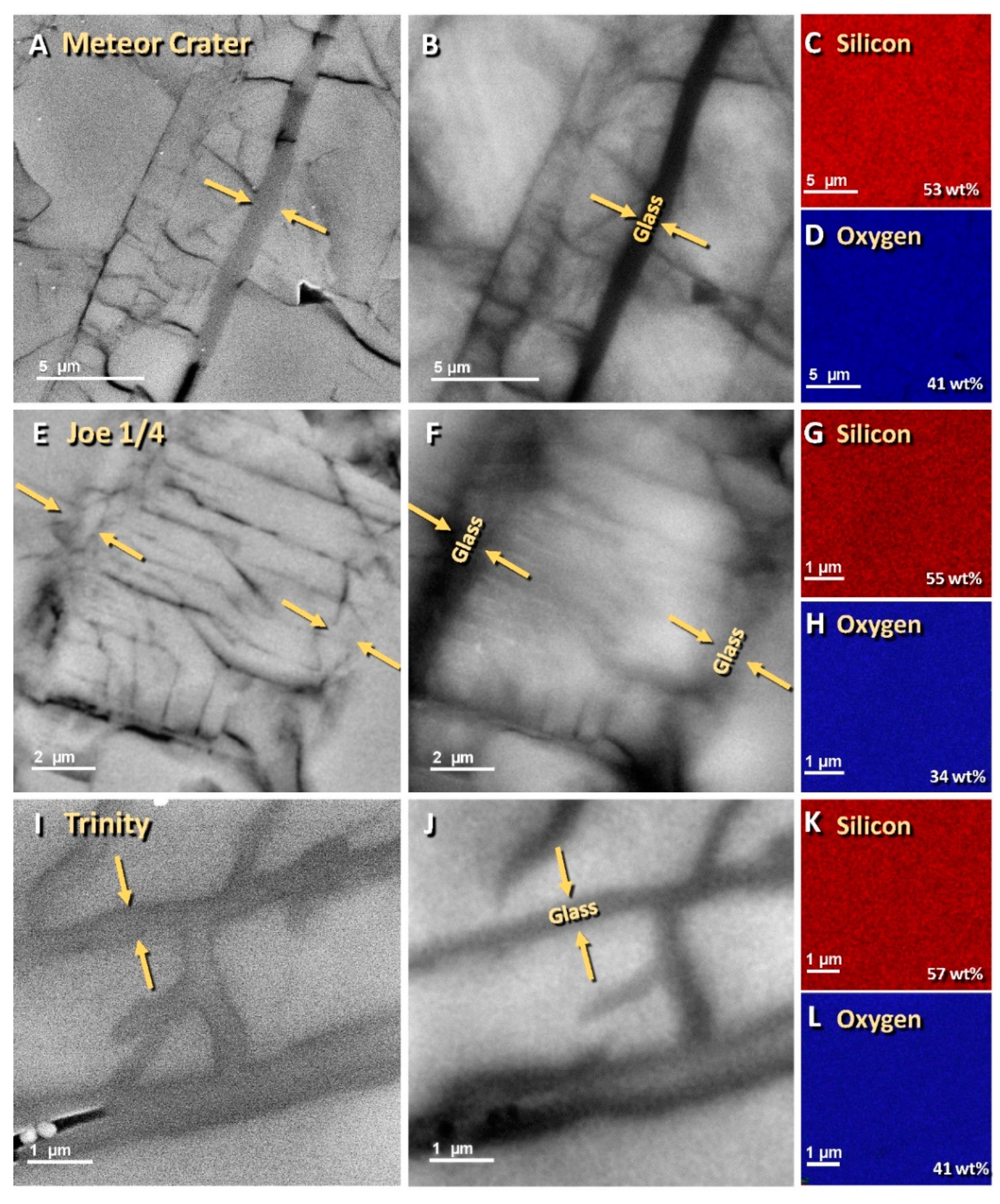

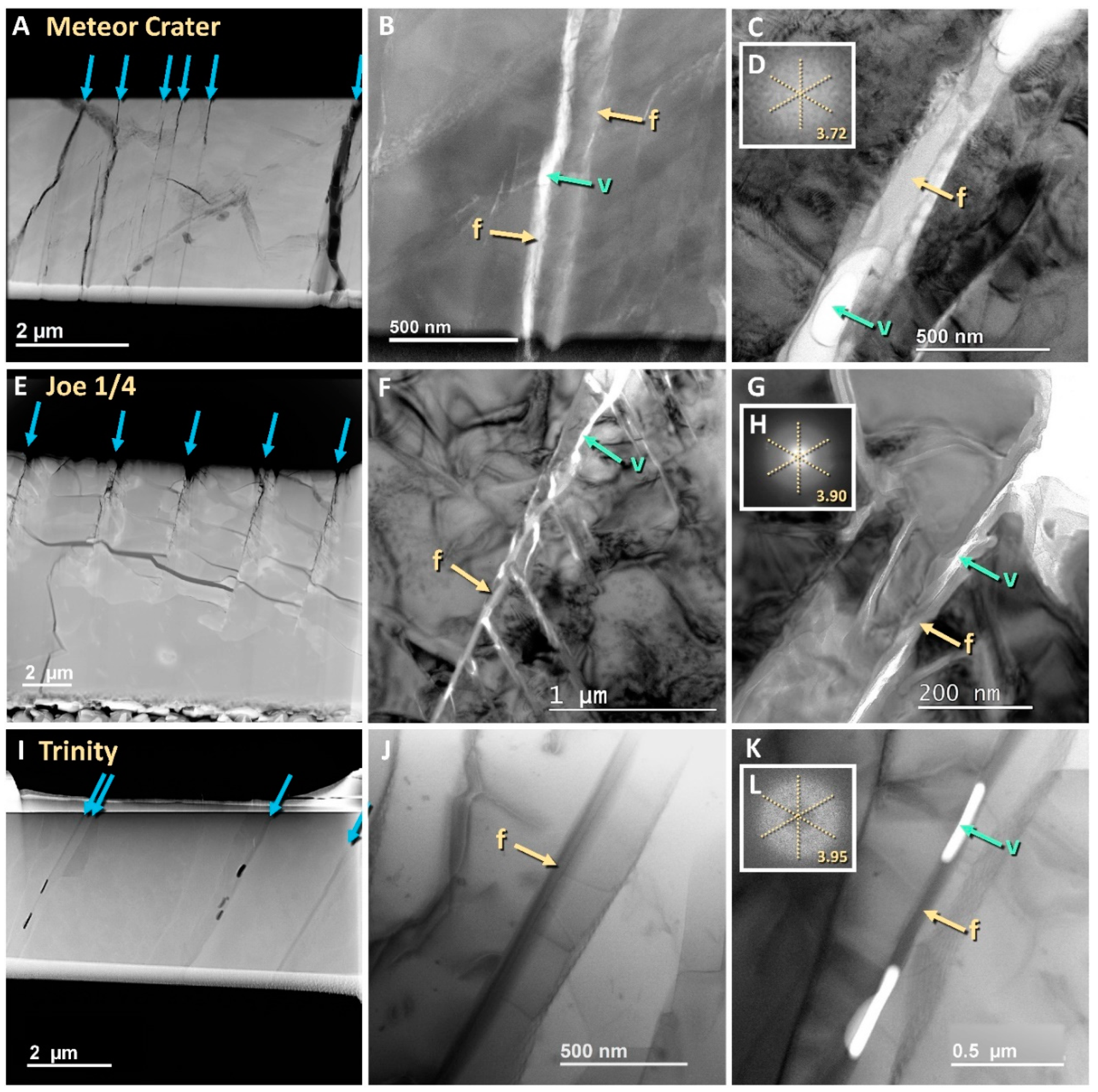

Scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM). FIB locations on the grains analyzed are shown in

Figure 5. Using STEM, the 8- to 15-µm-wide foils display inter-fracture spacings ranging from ~250 nm to 3

μm (Figure 6). Nearly all shock fractures were observed to contain material that was shown to be amorphous silica discontinuously filling the fractures, while, in contrast, HF-etched grains with visible tectonic deformation lamellae have not been observed to display any associated

amorphous silica (Appendix,

Figure S4A). Similarly, unshocked, HF-etched, natural quartz grains display no visible lamellae (Appendix,

Figure S5).

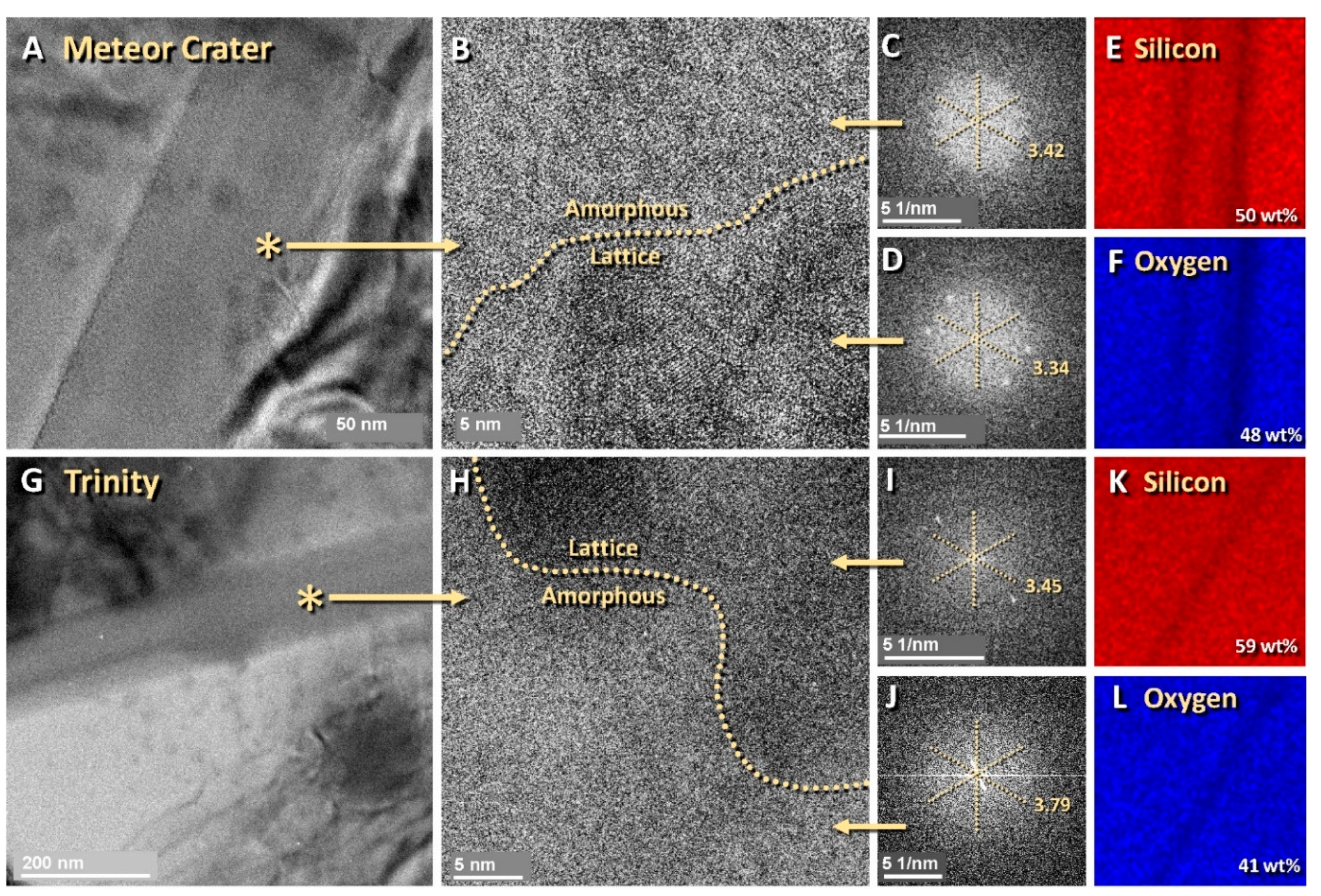

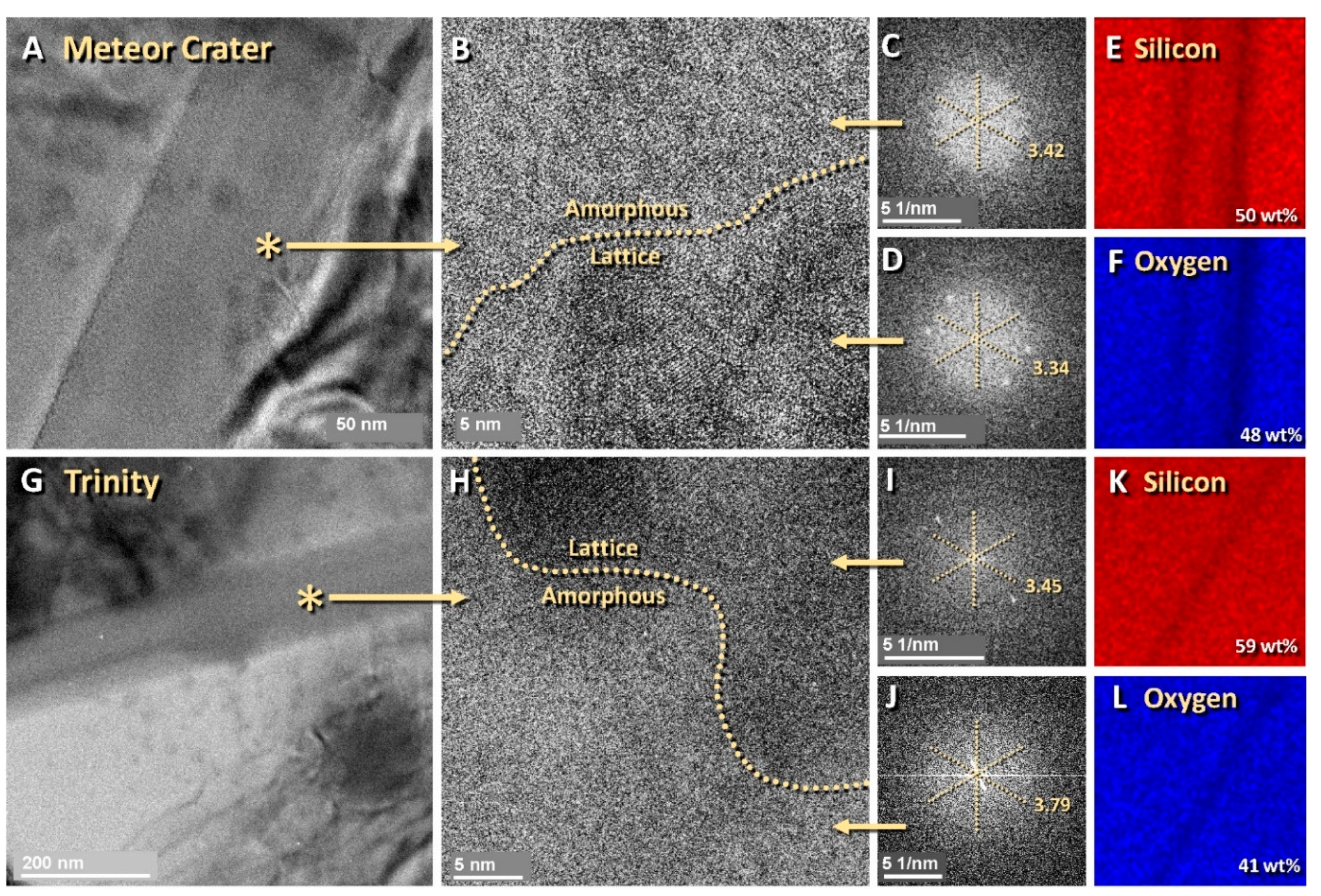

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Images acquired using TEM show sub-planar shock fractures containing thin bands of amorphous silica (

Figure 6). We confirmed the amorphous state of the fill material using high-resolution TEM that can image individual atoms (

Figure 7).

Numerous inclusions, also known as decorations or vesicles, are filled with glass or gases and are closely associated with shock fractures (

Figure 6). Madden et al. [

57] reported that multi-phase inclusions of glass, gases, and fluids are common at Meteor Crater in sandstone lightly shocked at ≥5.5 to 13 GPa. In contrast, that study observed no multi-phase inclusions in samples formed at >13 GPa in shock stages 3 or 4, suggesting that the high shock pressures collapsed the inclusions [

57]. Thus, the evidence suggests that these grains with shock fractures formed at low shock pressures of 5 to 13 GPa at shock stages 1 to 2. In contrast, unshocked tectonically-deformed quartz grains may display lines of bubbles, known as decorations, that instead, form by the dissolution of quartz by water rather than by shock-related processes (Appendix,

Figure S4).

Fast-Fourier transform (FFT).The areas of the grains from which the foils were extracted are shown in

Figure 5. In this study, the

FFT analyses commonly displayed crystalline structure in the quartz matrix away from the shock fractures, but most shock fractures displayed a diffuse halo or ring indicative of amorphous material [

33,

58,

59]

, especially in the thin bands of glass along the shock fractures (Figure 6 and

Figure 7).

FFTs of the filling along these thin fractures display the diffuse halo-like patterns characteristic of amorphous material [

33,

58,

59].

The halos have average d-spacings of ~3.72 Å

for Meteor Crater, ~3.90 Å

for Joe-1/4; and ~3.95 Å

for Trinity (Figure 6)

. Other average halo d-spacings for Meteor Crater are 3.42 and 3.34 Å and for Trinity, they are 3.45 and 3.79 Å (Figure 7). The mean value of 10 grains is 3.60 Å with a range of 3.34 to 3.95 Å.

Plots of average halo d-spacings are 3.50, 3.60, and 3.70 Å for each of the three sites,

showing close correspondence to a reported halo d-spacing of 4.2 Å

for quartz glass [

60] (

Figure 8).

Gleason et al. [

61]

conducted experiments on amorphous silica and noted that unshocked amorphous silica had a d-spacing of about 4.20 Å

. In contrast, quartz that had been exposed to shock pressures ranging from 4.7 to 33.6 GPa transformed into amorphous silica that permanently densified, causing the normal glass d-spacing to decrease to within a

range of 3.36 to 4.00 Å. Thus, in our study, the d-spacing values (mean = 3.62 Å) are consistent with Gleason’s range, supporting our interpretation that amorphous silica from the three sites was shocked and

densified at high pressures.

TEM energy dispersive spectroscopy (TEM-EDS). Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) is an analytical technique used to determine the elemental composition of materials. EDS analyses of multiple grains demonstrated that most of the material filling fractures is predominantly composed of silicon and oxygen (range: 98-99 wt%). Together with the presence of the diffuse rings exhibited in the FFT results (

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8), this finding confirms that the material filling the fractures is amorphous silica. On the other hand, this Si-rich material is inconsistent with being hydrated silica (opal, hyalite) that potentially can precipitate into fractures, because the filling lacks spherical micro-structures typically present in opal [

62]. Furthermore, TEM-EDS analyses reveal insufficient levels of oxygen to account for the hydration of silica (opal, hyalite) [

62]. Concentrations typically total ~66 wt% oxygen in opal and hyalite [

62], compared with ~28 to 48 wt% in the filling of our samples. For EDS spectra and other details, see Appendix,

Figures S6–S9.

Most material that fills the fractures is amorphous silica, but some fractures are intermittently filled with C, Al, Mg, Fe, or Ca. These represent secondary materials possibly injected into the fractures during their formation, precipitated later into the fractures, or introduced during the preparation and polishing of samples.

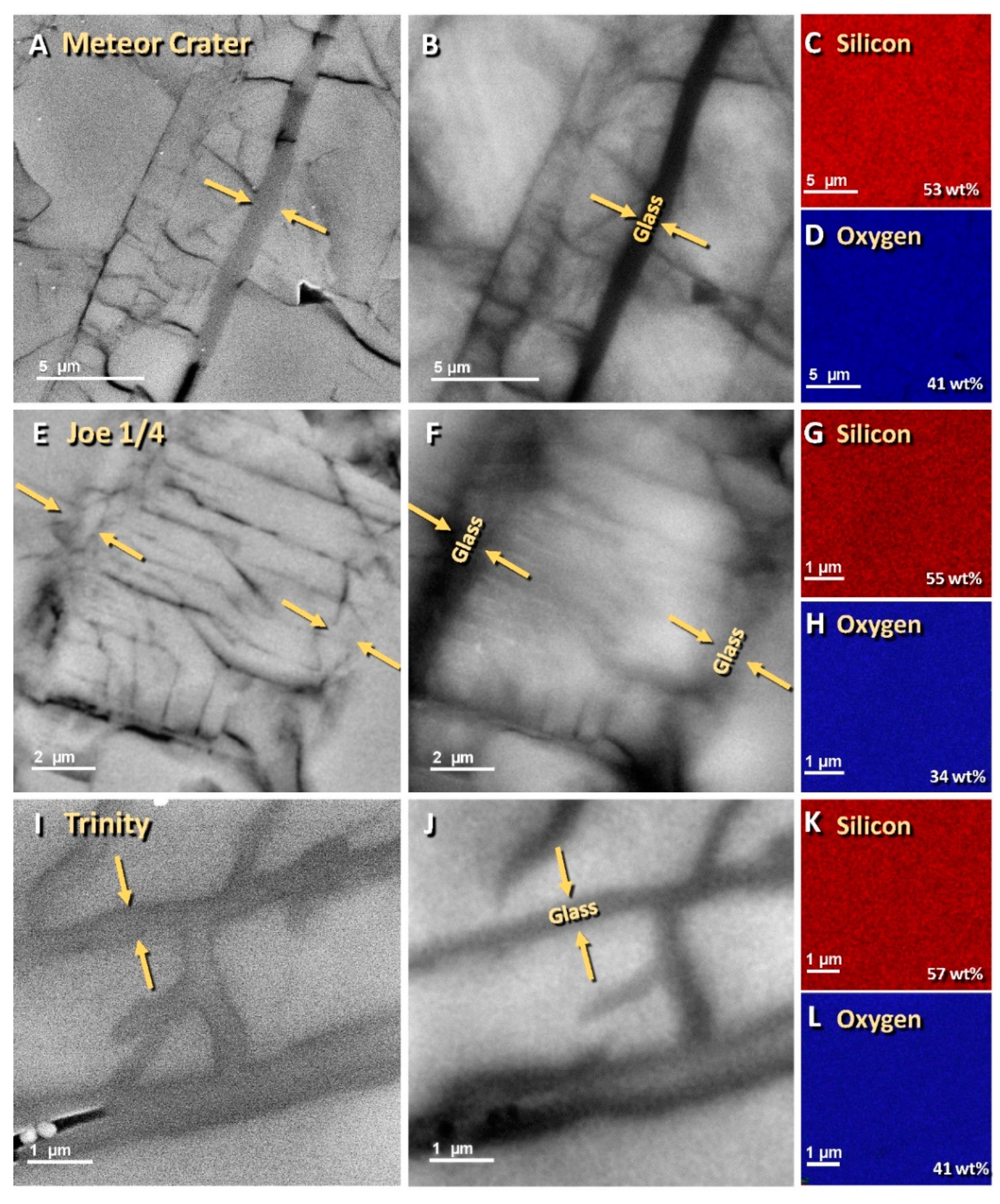

Cathodoluminescence (CL). The areas of grains analyzed for CL are shown in

Figure 5. Representative CL images are shown in

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11. Under CL, fractures filled with amorphous silica have been reported to be commonly non-luminescent, i.e., black [

21,

59,

63], although some defect structures in amorphous silica have been reported to luminesce red [

64]. Alternately, natural, open fractures also appear black, and therefore, the possible presence of amorphous silica must be confirmed by TEM and EDS. According to previous studies [

21,

59,

63,

65], if quartz luminesces red, it has been heated or melted and re-crystallized but does not contain amorphous silica. In addition, tectonic deformation lamellae may appear red but never black [

21,

59,

63,

65]. Typically, non-shocked quartz lattice luminesces blue under CL but never black [

21,

59,

63,

65].

SEM energy dispersive spectroscopy (SEM-EDS). For these analyses, we selected multiple areas that displayed fractures filled with material (

Figure 7 and

Figure 8). In most cases, EDS analyses indicated the quartz matrix and filling material were predominantly silica and oxygen (range: 89-98 wt%). The balance was made up of carbon, presumably from the carbon-coating that was evenly dispersed across the area analyzed. For EDS spectra and other details, see Appendix,

Figures S10–S14.

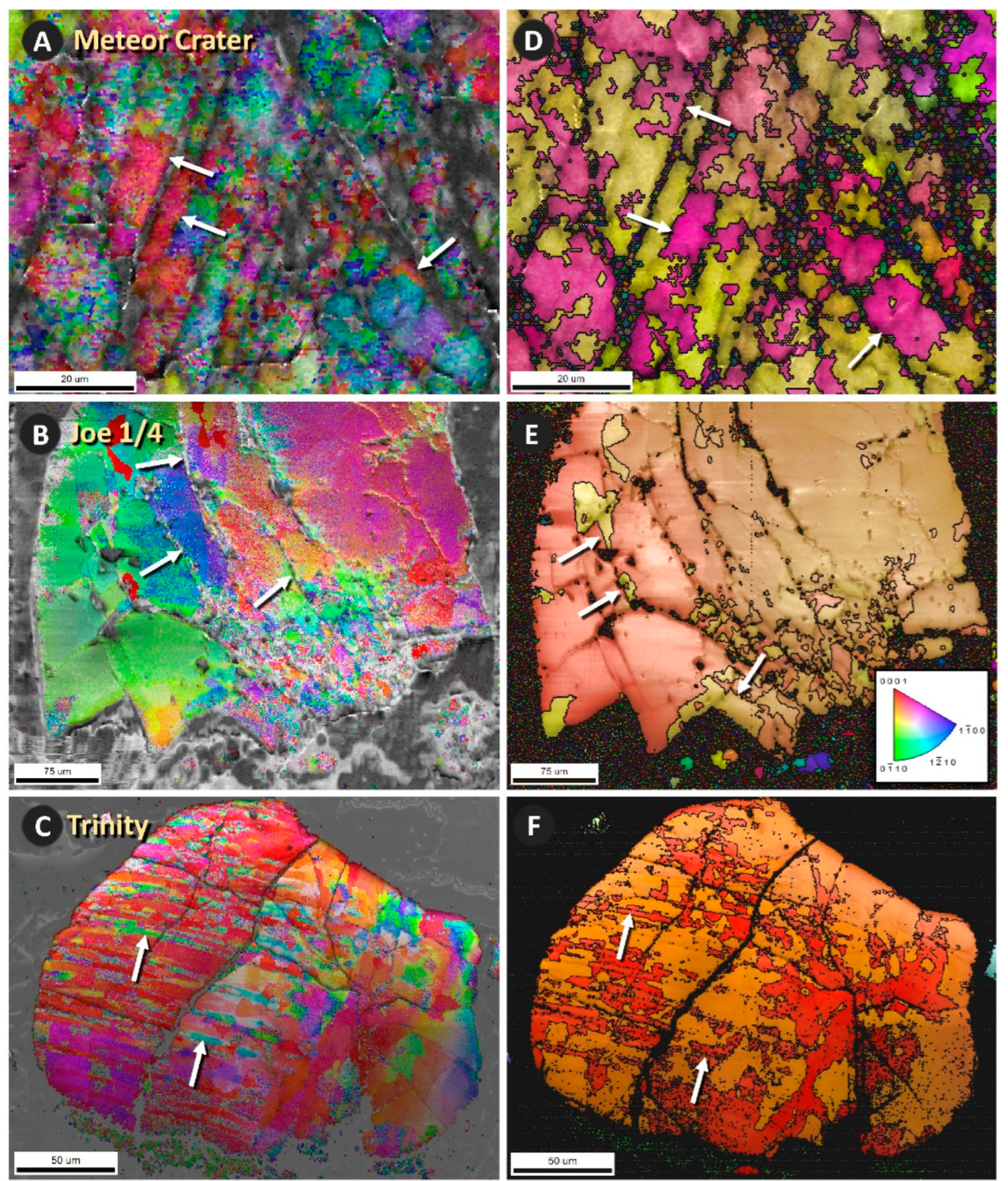

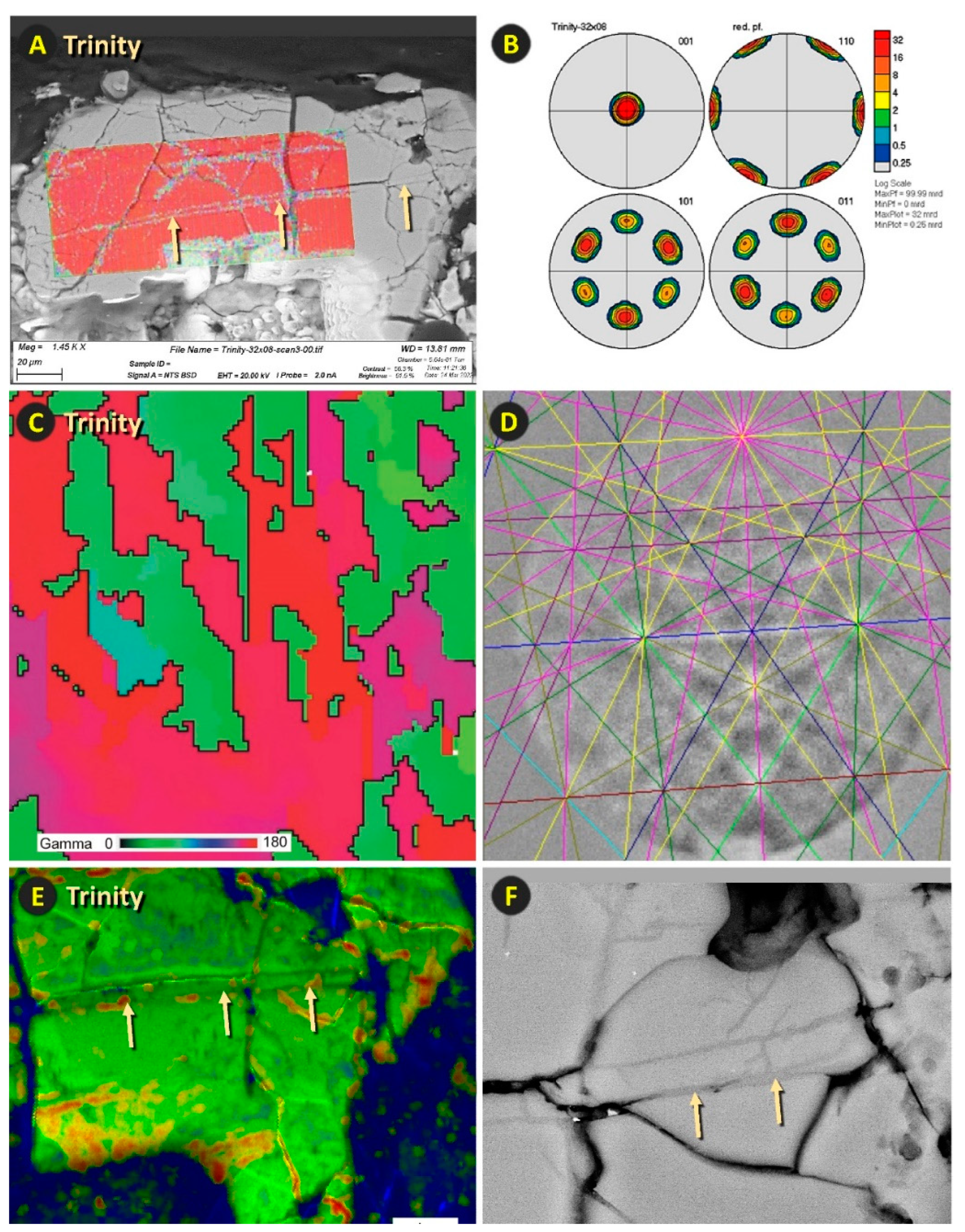

Electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD). Analyses performed using EBSD rely on varying comparisons of the Kikuchi patterns in a given grain, as shown in Appendix,

Figures S15–S18. We used multiple EBSD routines, including one called “virtual backscatter,” and the images produced by this routine reveal an extensive network of oriented shock fractures for all three sites (

Figure 12). Importantly, the majority of the hundreds of quartz grains in each sample from the three sites display these shock fractures. These images closely match those from shock experiments at ≥5.5 GPa by Kowitz et al. [

11] (

Figure 1).

Each grain’s crystallographic orientation is indicated for each image in the left column by the lattice diagram in the lower right corner (

Figure 12A–C). The red-colored plane represents (0001), the basal plane, with the

c-axis perpendicular to it. Although the shock fractures are non-planar, their general orientations correspond well with the crystallographic planes depicted on each pole Figure. This suggests that the shock fractures form similarly to high-shock planar deformation features (PDFs) and planar fractures (PFs) but are unlike tectonically-deformed lamellae [

8,

66].

EBSD “local orientation spread” (LOS). The high pressures during shock metamorphism damage and distort the crystalline lattice of quartz grains. To identify and quantify any potential grain damage, we used an EBSD routine called “local orientation spread” that generates Kikuchi patterns of the quartz lattice. The EDAX EBSD software compares these short-range patterns to reveal possible rotations or misorientations of the crystalline lattice, after which, the average misorientation of any given point is calculated relative to neighboring points. For the three sites, we observed values ranging from 0° to ~5° of misorientation, and this misoriented lattice tends to be concentrated along the shock fractures (

Figure 12). We found that such misorientations are common in quartz with shock fractures but are atypical in unshocked quartz grains (e.g., Appendix,

Figure S5).

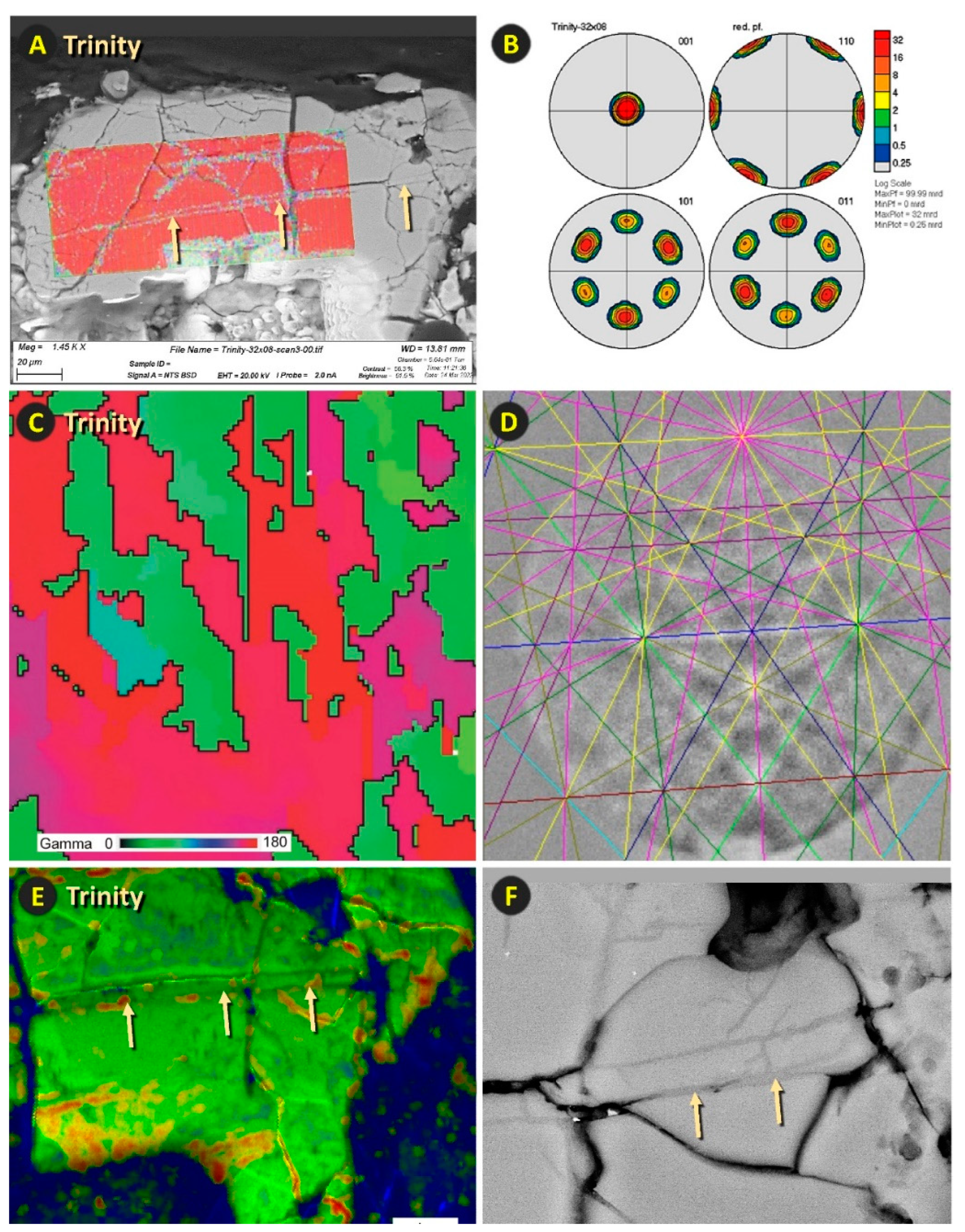

Trinity grain 32x08 was scanned with a scanning electron microscope (

Figure 13A) that recorded EBSD data from a ~20 nm area and indexed the crystallographic patterns automatically (

Figure 13B). This provides information about the orientation of the crystal at that spot relative to sample coordinates, generally defined by three Euler angles that relate sample and crystal coordinate systems.

Figure 13C is a map over the same Trinity quartz grain with colors indicative of Euler angle f2; the Kikuchi pattern is shown in

Figure 13D. The pole figure in

Figure 13B shows that across the selected area, two main orientations are present. The quartz grain has a

c-axis roughly perpendicular to the sample surface (001 pole figure) and two orientations of rhombohedral planes (101 and 011) related by a 60° (180°) rotation around the

c-axis. This orientation relationship is known as Dauphiné twinning which can form in multiple ways: during growth; during the phase transition from hexagonal high quartz to trigonal low quartz; during mechanical deformation; or during recrystallization after thermal shock. Several studies have observed Dauphiné twins in quartz subjected to stress (e.g. Schubnikow and Zinserling [

67]; Tullis [

68]; and Wenk et al. [

41]). From the Euler angle relationships, twin boundaries can be defined and the Dauphiné twin boundaries are plotted as black lines in

Figure 13C.

EBSD “grain reference orientation deviation” values superimposed on EBSD “image quality” values. Orientation deviation maps (

Figure 14) assist with visualizing the distribution of local lattice angular misorientations by color-coding the variations. EDAX’s EBSD software analyzes and colorizes individual points to illustrate any rotation of the crystalline lattice around an arbitrary common point on the grain with a wide range of colors that each represents areas with short-range misorientations relative to the common point. In contrast, unshocked grains and tectonically-deformed grains display few misorientations (Appendix,

Figures S4 and S5).

Several of the grains in

Figure 14 exhibit shock fractures that are curved. As the shock fractures formed, the lattice may have become distorted at high ambient temperatures or by shock melting, as suggested by Buchanan and Reimold [

16] and Reimold and Koeberl [

13].

EBSD “inverse pole Figure” values superimposed on EBSD “image quality” values. The inverse pole Figures (right column of

Figure 14) reveal variations in the lattice axes of quartz relative to a frame of reference, which, in these examples, is the (0001) basal plane. The EBSD results indicate that these are monocrystalline grains. In each case, measurements show that areas of quartz grains known as Dauphiné twins are rotated 60° relative to the c-axis. Dauphiné twinning is undetectable by standard optical microscopy and SEM but can easily be seen using EBSD.

Our analyses indicate that, although Dauphiné twins are nearly ubiquitous in all quartz grains, including unshocked or tectonically deformed grains, they are typically distributed randomly in the latter (Appendix,

Figures S4 and S5). In contrast, for the shocked quartz analyzed in our study, Dauphiné twins typically align with the trend of the shock fractures, suggesting that they crystallized as the fractures formed under high stress. It has long been recognized that Dauphiné twins form when quartz is subjected to mechanical stress [

67]. Later, Wenk et al. [

41] further concluded that Dauphiné twinning occurs under high thermal stress, as well as mechanical stress. Subsequently, Wenk et al. [

42] reported that Dauphiné twinning provides evidence for an impact-related origin of shocked quartzite collected from the Vredefort crater in South Africa.

Additional supporting evidence. In the Appendix, we provide additional images in support of the presence of glass-filled shock fractures in quartz grains from Trinity, Joe, and Meteor Crater. These include images acquired using the same analytical techniques presented above (optical, epi, SEM, TEM, STEM, CL, and EBSD). See Appendix,

Figures S19–S21.

3. Discussion

This investigation supports the hypothesis that glass-filled shock fracturing can occur both in nuclear detonations and in impact-cratering events. Next, we discuss potential formation mechanisms.

Shock fracturing by compression. Evidence indicates that shock fractures, as well as shock PDFs and PFs, form when quartz grains are subjected to shock pressures above their Hugoniot elastic limit (HEL), which, for quartz, ranges from ~3–8 GPa [

27]. This pressure range corresponds with that estimated for the nuclear tests of Trinity and Joe-1/4. For shock metamorphism to occur, the shockwave must exceed the velocity of the elastic wave for quartz. A pressure database [

69] reveals that in quartz, velocities of the pressure wave range from 6.3 to 6.9 km/sec, depending on a quartz grain’s orientation.

When quartz is exposed to a high-pressure shockwave, the crystalline lattice compresses only in the propagating direction, while the other two perpendicular directions remain at ambient pressure. At the moment of greatest pressure, the grain cannot fracture easily because it is constrained by the confining pressure. The lattice, unable to transmit the shockwave elastically, develops a set of microfractures to accommodate the additional stress. When quartz grains are embedded in porous bedrock, such as sandstone, the rock medium may reflect the shockwave in different directions and this leads to multiple sets of shock fractures and to amorphization that can form at lower pressures in porous rock [

4].

High shock pressures commonly produce quartz phases called coesite or stishovite. However, we found no evidence of these phases, which have been previously observed at Meteor Crater [

1,

2,

32,

47,

48,

70,

71,

72,

73]. This supports the hypothesis that the shocked grains investigated in this study from Trinity, Joe, and Meteor Crater formed at the lower range of shock pressures, estimated to be ≤8 GPa.

Shock fracturing by tension. In both airbursts and crater-forming events, the fracturing of quartz grains may also occur from tensile forces or, more specifically, due to spallation [

26,

35,

37,

74,

75,

76]. This shock process occurs when a compressive shockwave enters a material, such as a quartz grain, and then is reflected off the grain boundary, producing a rarefaction wave. This wave can exceed the tensile strength of the material, thus producing multiple oriented fractures. This process frequently produces the most mechanical damage, because the tensile strength of quartz is typically lower than its compressive strength.

Thermal shock fracturing. For shock fractures to form in quartz, the crystalline lattice must experience high stress and strain, not just from high pressures but also typically from high-temperature gradients. Nuclear tests like Trinity generate fireballs with extreme temperatures that rise to ~200,000 °C within 10

-4 sec but then after 3 sec, drop to below the melting point of quartz [

77]. Such extreme, short-lived temperatures followed by rapid quenching are capable of fracturing quartz grains due to sudden thermal expansion followed by rapid cooling. In addition, the intense thermal and gamma radiation may heat the quartz grains to near-melting and thus, reduce the pressures needed to form shock fractures.

Most importantly, the high temperatures appear to vaporize quartz grains and sediment, after which the high blast pressures inject molten silica vapor and other molten material into fractures and any other zones of weakness in exposed quartz grains [

33,

37]. Molten silica appears to enter the grains along multiple possible pathways: (i) fractures produced by the shockwave; (ii) fractures produced by high temperatures; (iii) pre-existing quartz fractures; (iv) pre-existing PDFs and PFs; (v) pre-existing tectonic lamellae; and (vi) pre-existing subgrain boundaries. In the cases of the pre-existing features, the shock fracturing overprints and modifies the existing features. Even though these types of fractures may form under substantially different shock and non-shock conditions, all have one common characteristic: they eventually become injected with amorphous silica.

Proposed model for producing shock fractures. To summarize, we propose that shock fractures in nuclear airbursts and cratering events form in the following sequence. (i) Fractures in quartz grains either pre-exist or are produced by the high-pressure shockwave and thermal pulse; (ii) some quartz grains are vaporized by the blast and this vapor is transported away from ground zero in the expanding fireball; (iii) the outer surfaces of some quartz grains melt at >1720 °C, the melting point of quartz; (iv) the extreme pressures inject molten silica or silica vapor into the fractures; and (v) both thermal and pressure shock may cause further random melting in the interior of some grains.

Future studies. Several studies [

34,

36,

37,

75,

78] have reported evidence that shock fractures are produced in cosmic airbursts when a high-pressure, high-temperature fireball intersects the surface, similar to the nuclear airbursts described here. These cosmic airbursts may produce shallow craters rather than classic hard-impact craters. It is recommended that future studies further investigate the hypothesis that low-shock, glass-filled shock fractures are produced in quartz grains during near-surface cosmic airbursts. Similarly, we suggest further research to better understand glass-filled fractures in hard-impact craters of all sizes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: R.E.H., H.-R.W., J.P.K., T.E.B., G.K., A.W. Formal analysis: R.E.H., H.-R.W., J.P.K., T.E.B., C.R.M., M.A.L., G.K., A.V.A., K.L., J.J.R., M.W.G., S.M., J.P.P., R.P., M.N., A.W. Investigation: R.E.H., H.-R.W., J.P.K., T.E.B., C.R.M., M.A.L., G.K., A.V.A., K.L., J.J.R., M.W.G., S.M., J.P.P., R.P., M.N., A.W. Writing-original draft: R.E.H., H.-R.W., J.P.K., T.E.B., C.R.M., M.A.L., G.K., A.W. Writing-review and editing: R.E.H., H.-R.W., J.P.K., C.R.M., M.A.L., G.K., A.W. Funding acquisition: R.E.H., H.-R.W., J.P.K., G.K., A.W. All authors reviewed and approved this manuscript.

Figure 1.

Low-shock fractures in quartz. SEM backscatter electron (BSE) images of polished, thin-sectioned grains from shock experiments by Kowitz et al. [

11] showing (

A) original unshocked quartz grains; (

B) grains with non-planar, intra-granular microfractures initially produced at 5 GPa; (

C) grains shocked at 7.5 GPa. Red arrows mark the direction of the applied shock from the top of the images down; yellow arrows mark selected representative fractures. Adapted and cropped from Kowitz et al. [

11] Used with permission.

Figure 1.

Low-shock fractures in quartz. SEM backscatter electron (BSE) images of polished, thin-sectioned grains from shock experiments by Kowitz et al. [

11] showing (

A) original unshocked quartz grains; (

B) grains with non-planar, intra-granular microfractures initially produced at 5 GPa; (

C) grains shocked at 7.5 GPa. Red arrows mark the direction of the applied shock from the top of the images down; yellow arrows mark selected representative fractures. Adapted and cropped from Kowitz et al. [

11] Used with permission.

Figure 2.

Meteor Crater, Arizona. 1.2-km-wide impact crater near Flagstaff in northern Arizona [

51]. The 180-m-deep crater is surrounded by an ejecta blanket elevated ~30 to 60 m above the surrounding plateau. Source: “Meteor Crater” 35.032206° N, 111.023988° W. Google Earth. Imagery date: 2022. Yellow pin marks the location of sample analyzed. Accessed: 10/08/2022. Permissions:

https://about.google/brand-resource-center/products-and-services/geo-guidelines/.

Figure 2.

Meteor Crater, Arizona. 1.2-km-wide impact crater near Flagstaff in northern Arizona [

51]. The 180-m-deep crater is surrounded by an ejecta blanket elevated ~30 to 60 m above the surrounding plateau. Source: “Meteor Crater” 35.032206° N, 111.023988° W. Google Earth. Imagery date: 2022. Yellow pin marks the location of sample analyzed. Accessed: 10/08/2022. Permissions:

https://about.google/brand-resource-center/products-and-services/geo-guidelines/.

Figure 4.

Trinity Test Site in New Mexico. (A) Trinity ~300-meter-wide nuclear fireball, taken 25 ms after 24.8-kt detonation. Photo date: 16 July 1945. Courtesy of US Govt. Defense Threat Reduction Agency. Source:

http://www.nucleararchive.com/Photos/Trinity/image8.shtml This work is in the public domain. (B) Post-detonation photograph. The photo was taken in July 1945 approximately 28 hours after the blast. The dark color represents trinitite glass within a ~400-meter-radius blast zone, which was discontinuously covered with ejected dark trinitite glass. Note that dark streaks of material radiate from ground zero. Source: “Trinity”, 33.68100° N, 106.4756° W. Google Earth. Imagery accessed: 10/08/2022. Permissions:

https://about.google/brand-resource-center/products-and-services/geo-guidelines/.

Figure 4.

Trinity Test Site in New Mexico. (A) Trinity ~300-meter-wide nuclear fireball, taken 25 ms after 24.8-kt detonation. Photo date: 16 July 1945. Courtesy of US Govt. Defense Threat Reduction Agency. Source:

http://www.nucleararchive.com/Photos/Trinity/image8.shtml This work is in the public domain. (B) Post-detonation photograph. The photo was taken in July 1945 approximately 28 hours after the blast. The dark color represents trinitite glass within a ~400-meter-radius blast zone, which was discontinuously covered with ejected dark trinitite glass. Note that dark streaks of material radiate from ground zero. Source: “Trinity”, 33.68100° N, 106.4756° W. Google Earth. Imagery accessed: 10/08/2022. Permissions:

https://about.google/brand-resource-center/products-and-services/geo-guidelines/.

Figure 5.

Images of quartz grains. Optical microscopy (OPT), left panels A, D, G. Epi-illumination (EPI), middle panels B, E, H. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM), right panels C, F, I. (A-C) Grains from Meteor Crater, Arizona. (D-F) Grains from the Russian Joe-1/4 nuclear test. (G-I) Grains from the Trinity nuclear test site. Optical images (left column) were acquired under crossed polarizers. Yellow arrows indicate random representative shock fractures. Panels A and D show dark bands of undulose extinction between orange lines labeled “u”. The Trinity grain in panels G and H displays oriented pairs of shock fractures between blue arrows. Red arrows in panels C, F, and I (right column) mark sites from which micron-sized slices of the quartz grain were removed using the focused ion beam (FIB) and then analyzed using TEM and TEM-EDS. The red asterisks in the right column mark locations of CL and SEM-EDS analyses.

Figure 5.

Images of quartz grains. Optical microscopy (OPT), left panels A, D, G. Epi-illumination (EPI), middle panels B, E, H. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM), right panels C, F, I. (A-C) Grains from Meteor Crater, Arizona. (D-F) Grains from the Russian Joe-1/4 nuclear test. (G-I) Grains from the Trinity nuclear test site. Optical images (left column) were acquired under crossed polarizers. Yellow arrows indicate random representative shock fractures. Panels A and D show dark bands of undulose extinction between orange lines labeled “u”. The Trinity grain in panels G and H displays oriented pairs of shock fractures between blue arrows. Red arrows in panels C, F, and I (right column) mark sites from which micron-sized slices of the quartz grain were removed using the focused ion beam (FIB) and then analyzed using TEM and TEM-EDS. The red asterisks in the right column mark locations of CL and SEM-EDS analyses.

Figure 6.

Images using STEM, TEM, and fast-Fourier transform (FFT). (A-D) Grain #10x-12 from Meteor Crater, Arizona. (E-H) Grain #14x-04 from the Russian Joe-1/4 nuclear test. (I-L) Grain #09x11 from Trinity meltglass. The blue arrows mark shock fractures (left column) in these STEM images, in which the dark lines represent fractures and the black areas represent voids. For TEM brightfield analyses (middle and right columns), arrows labeled “f” mark material that discontinuously fills the shock fractures. Green arrows labeled “v” indicate voids that appear white in TEM mode, rather than black as in STEM. Panels D, H, and L are FFTs. The diffuse halo in each indicates that the material filling of some shock fractures is amorphous; halo d-spacings were measured along dashed yellow lines and averaged 3.72 Å in panel D, 3.90 Å in panel H, and 3.95 Å in panel L. These d-spacings indicate that the filling of the fractures is amorphous silica. The diameter of the TEM beam spot was ~0.5 µm. Insets of diffraction spectra were acquired at “f” in each corresponding TEM image.

Figure 6.

Images using STEM, TEM, and fast-Fourier transform (FFT). (A-D) Grain #10x-12 from Meteor Crater, Arizona. (E-H) Grain #14x-04 from the Russian Joe-1/4 nuclear test. (I-L) Grain #09x11 from Trinity meltglass. The blue arrows mark shock fractures (left column) in these STEM images, in which the dark lines represent fractures and the black areas represent voids. For TEM brightfield analyses (middle and right columns), arrows labeled “f” mark material that discontinuously fills the shock fractures. Green arrows labeled “v” indicate voids that appear white in TEM mode, rather than black as in STEM. Panels D, H, and L are FFTs. The diffuse halo in each indicates that the material filling of some shock fractures is amorphous; halo d-spacings were measured along dashed yellow lines and averaged 3.72 Å in panel D, 3.90 Å in panel H, and 3.95 Å in panel L. These d-spacings indicate that the filling of the fractures is amorphous silica. The diameter of the TEM beam spot was ~0.5 µm. Insets of diffraction spectra were acquired at “f” in each corresponding TEM image.

Figure 7.

TEM images of quartz shock fractures filled with amorphous silica. A)-F) is from Meteor Crater (grain #09x-11); G)-L) is from Trinity (grain #09x11). A) TEM brightfield image of the region of interest. (B) A close-up brightfield image exhibits the crystalline lattice below the dotted line and the amorphous silica above; acquired at the asterisk in panel A. (C) Fast-Fourier transform (FFT) of the top part of panel B exhibits a diffuse halo indicative of amorphous silica with a d-spacing of 3.42 Å. (D) FFT of the bottom part of panel B exhibits diffraction spots with a halo indicative of a mix of crystalline lattice with amorphous silica. The halo measures 3.34 Å. (E-F) EDS panels show a composition of 98 wt% silica. (G) TEM brightfield image of the region of interest. (H) A close-up brightfield image exhibits the crystalline lattice above the dotted line and the amorphous silica below the line; the image was acquired at the asterisk in panel G. (I) FFT of the top part of panel H shows diffraction spots with a halo that measures 3.45 Å. (J) FFT of the bottom part of panel H displays a diffuse halo indicative of amorphous silica. The d-spacing of the amorphous halo is 3.79 Å. (K-L) EDS panels showing a composition of 100 wt% silica.

Figure 7.

TEM images of quartz shock fractures filled with amorphous silica. A)-F) is from Meteor Crater (grain #09x-11); G)-L) is from Trinity (grain #09x11). A) TEM brightfield image of the region of interest. (B) A close-up brightfield image exhibits the crystalline lattice below the dotted line and the amorphous silica above; acquired at the asterisk in panel A. (C) Fast-Fourier transform (FFT) of the top part of panel B exhibits a diffuse halo indicative of amorphous silica with a d-spacing of 3.42 Å. (D) FFT of the bottom part of panel B exhibits diffraction spots with a halo indicative of a mix of crystalline lattice with amorphous silica. The halo measures 3.34 Å. (E-F) EDS panels show a composition of 98 wt% silica. (G) TEM brightfield image of the region of interest. (H) A close-up brightfield image exhibits the crystalline lattice above the dotted line and the amorphous silica below the line; the image was acquired at the asterisk in panel G. (I) FFT of the top part of panel H shows diffraction spots with a halo that measures 3.45 Å. (J) FFT of the bottom part of panel H displays a diffuse halo indicative of amorphous silica. The d-spacing of the amorphous halo is 3.79 Å. (K-L) EDS panels showing a composition of 100 wt% silica.

Figure 8.

TEM images [left column]; FFT patterns and plots [middle column]; EDS elemental maps [right column]. All images were acquired from FIB foils. (A-D) Grain #10x-12 from Meteor Crater, Arizona. (E-H) Grain #14x-04 from the Russian Joe-1/4 nuclear test. (I-L) Grain #30x08 from the Trinity JIE sediment sample. TEM images in the left column show the micron-sized areas analyzed; asterisks mark the locations used to generate the FFTs (middle column insets) and the EDS analyses (right column). Panel I (Trinity) shows a glass-filled shock fracture that intersects a glass-filled vesicle. In the middle column, the graphs show intensities plotted against d-spacings, generated from FFTs using the Profile function of Digital Micrograph, version 3.32.2403.0. Each grain shows a decrease in slope at d-spacings ranging from 3.50 to 3.70 Å (black line), marking the edges of the diffuse halos shown in the FFT insets. The yellow dashed lines plot a reference profile of non-shocked amorphous silica (melted quartz) [

60] with a slope change at 4.20 Å. The slopes of the yellow and black lines are similar, consistent with the presence of amorphous silica in the grains in this study. EDS analyses in right-hand panels confirm that the areas centered on the asterisks at left are predominantly silica and oxygen (range: 98-99 wt%).

Figure 8.

TEM images [left column]; FFT patterns and plots [middle column]; EDS elemental maps [right column]. All images were acquired from FIB foils. (A-D) Grain #10x-12 from Meteor Crater, Arizona. (E-H) Grain #14x-04 from the Russian Joe-1/4 nuclear test. (I-L) Grain #30x08 from the Trinity JIE sediment sample. TEM images in the left column show the micron-sized areas analyzed; asterisks mark the locations used to generate the FFTs (middle column insets) and the EDS analyses (right column). Panel I (Trinity) shows a glass-filled shock fracture that intersects a glass-filled vesicle. In the middle column, the graphs show intensities plotted against d-spacings, generated from FFTs using the Profile function of Digital Micrograph, version 3.32.2403.0. Each grain shows a decrease in slope at d-spacings ranging from 3.50 to 3.70 Å (black line), marking the edges of the diffuse halos shown in the FFT insets. The yellow dashed lines plot a reference profile of non-shocked amorphous silica (melted quartz) [

60] with a slope change at 4.20 Å. The slopes of the yellow and black lines are similar, consistent with the presence of amorphous silica in the grains in this study. EDS analyses in right-hand panels confirm that the areas centered on the asterisks at left are predominantly silica and oxygen (range: 98-99 wt%).

Figure 9.

SEM (A-C) images and cathodoluminescence (CL) images (D-F) of shock fractures in quartz grains. A) SEM image of quartz from Meteor Crater, grain 11x08. Shock fractures at arrows. (B) SEM image from the Joe-1/4 site, grain 03x16. Most shock fractures contain darker-contrast glass (g) along the shock fractures. The web-like structure is consistent with the high-pressure injection of molten silica or in situ melting. (C) SEM image of quartz from the Trinity site, grain 09x11. The arrow at “g” marks non-luminescent glass. (D) CL image of a different Meteor Crater grain 13x11 showing small, feather-like fractures angling away from the large irregular shock fracture. (E) CL image of a different grain from the Joe-1/4 site, grain 14x-04b. (F) CL image of a different grain, 06x14, from Trinity meltglass. Note that shock fractures are filled with bluish-gray-to-black, non-luminescent glass.

Figure 9.

SEM (A-C) images and cathodoluminescence (CL) images (D-F) of shock fractures in quartz grains. A) SEM image of quartz from Meteor Crater, grain 11x08. Shock fractures at arrows. (B) SEM image from the Joe-1/4 site, grain 03x16. Most shock fractures contain darker-contrast glass (g) along the shock fractures. The web-like structure is consistent with the high-pressure injection of molten silica or in situ melting. (C) SEM image of quartz from the Trinity site, grain 09x11. The arrow at “g” marks non-luminescent glass. (D) CL image of a different Meteor Crater grain 13x11 showing small, feather-like fractures angling away from the large irregular shock fracture. (E) CL image of a different grain from the Joe-1/4 site, grain 14x-04b. (F) CL image of a different grain, 06x14, from Trinity meltglass. Note that shock fractures are filled with bluish-gray-to-black, non-luminescent glass.

Figure 10.

SEM and cathodoluminescence (CL) images of shock fractures in quartz. (A, B) Grain 14x-04a from Meteor Crater, Arizona. (C, D) Grain 09x14 from the Russian Joe-1/4 nuclear test. (E, F) Grain 32x08 from Trinity meltglass. In the SEM images (left column) and CL images (right column), the red arrows point to sub-parallel pairs of shock fractures. In SEM images (left column), yellow arrows point to thin, dark-gray bands of amorphous silica, labeled “g”. In the CL images (right column), the bluish-gray-to-black bands at arrows labeled “g” indicate non-luminescent, glass-filled shock fractures. As confirmed by EDS, the material is amorphous silica (glass).

Figure 10.

SEM and cathodoluminescence (CL) images of shock fractures in quartz. (A, B) Grain 14x-04a from Meteor Crater, Arizona. (C, D) Grain 09x14 from the Russian Joe-1/4 nuclear test. (E, F) Grain 32x08 from Trinity meltglass. In the SEM images (left column) and CL images (right column), the red arrows point to sub-parallel pairs of shock fractures. In SEM images (left column), yellow arrows point to thin, dark-gray bands of amorphous silica, labeled “g”. In the CL images (right column), the bluish-gray-to-black bands at arrows labeled “g” indicate non-luminescent, glass-filled shock fractures. As confirmed by EDS, the material is amorphous silica (glass).

Figure 11.

Images acquired using SEM [left column]; grayscale panchromatic cathodoluminescence (CL) [middle column]; and energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) [right column]. (A-D) Grain #10x-12 from Meteor Crater, Arizona. (E-H) Grain #14x-04B from the Russian Joe-1/4 nuclear test. (I-L) Grain #32x08 from Trinity meltglass. In the SEM images (left column), the yellow arrows point to shock fractures filled with gray material. In the grayscale panchromatic CL images (spectrum: 185–850 nm; middle column), the yellow arrows point to the corresponding region, marked as glass. The gray-to-black color indicates that the filling material is non-luminescent, consistent with being amorphous silica [

21,

59,

63,

65]. The SEM-EDS panels (right column) are of approximately the same field of view as in the left column and confirm that the material is predominantly composed of silicon and oxygen (see EDS spectra for panels in Appendix,

Figures S10–S14). Thus, the evidence indicates the filling in the fractures is amorphous silica.

Figure 11.

Images acquired using SEM [left column]; grayscale panchromatic cathodoluminescence (CL) [middle column]; and energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) [right column]. (A-D) Grain #10x-12 from Meteor Crater, Arizona. (E-H) Grain #14x-04B from the Russian Joe-1/4 nuclear test. (I-L) Grain #32x08 from Trinity meltglass. In the SEM images (left column), the yellow arrows point to shock fractures filled with gray material. In the grayscale panchromatic CL images (spectrum: 185–850 nm; middle column), the yellow arrows point to the corresponding region, marked as glass. The gray-to-black color indicates that the filling material is non-luminescent, consistent with being amorphous silica [

21,

59,

63,

65]. The SEM-EDS panels (right column) are of approximately the same field of view as in the left column and confirm that the material is predominantly composed of silicon and oxygen (see EDS spectra for panels in Appendix,

Figures S10–S14). Thus, the evidence indicates the filling in the fractures is amorphous silica.

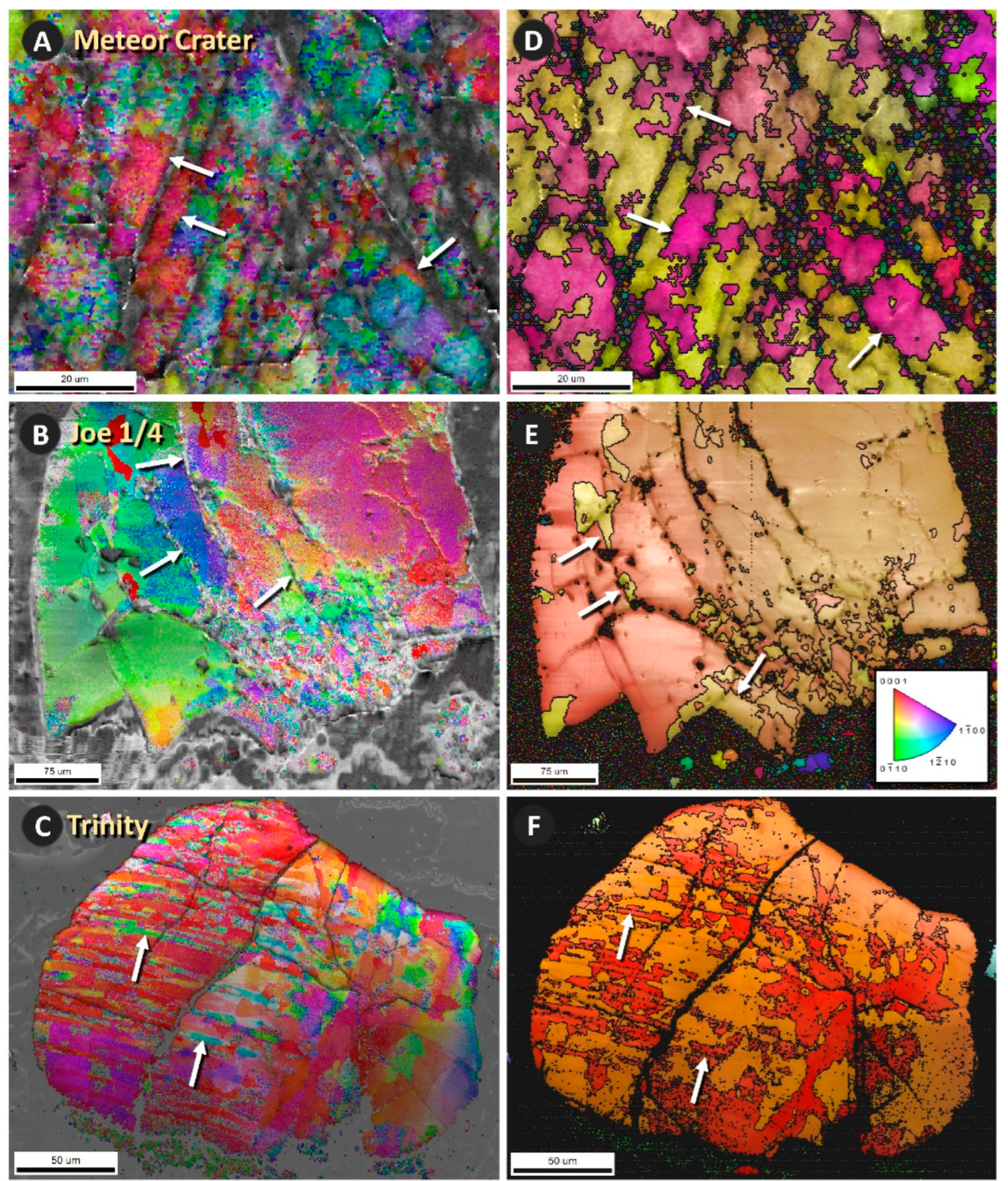

Figure 12.

Images using EBSD “virtual backscatter.” (A, D) Grain #10x-12 from Meteor Crater, Arizona. (B, E) Grain #14x-04B from the Russian Joe-1/4 nuclear test. (C, F) Grain #09x11 from Trinity meltglass. Virtual backscatter images in the left column show numerous oriented shock fractures, with arrows marking a few representative examples among the many fractures present. The lattice diagram at the lower right of each image (left column) represents the crystalline structure of that grain. In EBSD, the routines for image quality and local orientation spread (right column) were used to analyze the crystalline lattice to determine the degree of damage to each quartz grain. A multi-colored misorientation scale is inset into the lower right of panel D and applies to all images in the right column. The colors represent the degrees of misorientation, ranging from 0 degrees (blue) to ~5 degrees (red). Note that the greatest degree of misorientation (i.e., damage) is concentrated along shock fractures.

Figure 12.

Images using EBSD “virtual backscatter.” (A, D) Grain #10x-12 from Meteor Crater, Arizona. (B, E) Grain #14x-04B from the Russian Joe-1/4 nuclear test. (C, F) Grain #09x11 from Trinity meltglass. Virtual backscatter images in the left column show numerous oriented shock fractures, with arrows marking a few representative examples among the many fractures present. The lattice diagram at the lower right of each image (left column) represents the crystalline structure of that grain. In EBSD, the routines for image quality and local orientation spread (right column) were used to analyze the crystalline lattice to determine the degree of damage to each quartz grain. A multi-colored misorientation scale is inset into the lower right of panel D and applies to all images in the right column. The colors represent the degrees of misorientation, ranging from 0 degrees (blue) to ~5 degrees (red). Note that the greatest degree of misorientation (i.e., damage) is concentrated along shock fractures.

Figure 13.

Images of selected portions of shock-fractured quartz grain 32x08 from Trinity meltglass. A) EBSD “image quality” scan in red is superimposed on an SEM image; arrows mark a pair of oriented, sub-parallel shock fractures with damaged lattice, as indicated by the lack of an EBSD signal (red). (B) Pole figures across the grain with the c-axis (0001) nearly perpendicular to the surface but with Dauphine twins that share two orientations rotated 60 degrees (101 and 011). (C) EBSD map of Euler angle gamma which displays mainly two orientations (green and red). They are related by Dauphine twinning (180 - 30 deg rotation around the c-axis, black lines). Equal area projection. (D) Kikuchi patterns corresponding to EBSD scan in panel C. (E) Image quality and local orientation spread (LOS) image of lattice misorientations (yellow to red) that correspond to the sub-parallel shock fractures at arrows. (F) Close-up SEM-BSE image of oriented shock fractures. Medium gray areas represent amorphous silica, as separately confirmed by SAD, FFT, and TEM-EDS.

Figure 13.

Images of selected portions of shock-fractured quartz grain 32x08 from Trinity meltglass. A) EBSD “image quality” scan in red is superimposed on an SEM image; arrows mark a pair of oriented, sub-parallel shock fractures with damaged lattice, as indicated by the lack of an EBSD signal (red). (B) Pole figures across the grain with the c-axis (0001) nearly perpendicular to the surface but with Dauphine twins that share two orientations rotated 60 degrees (101 and 011). (C) EBSD map of Euler angle gamma which displays mainly two orientations (green and red). They are related by Dauphine twinning (180 - 30 deg rotation around the c-axis, black lines). Equal area projection. (D) Kikuchi patterns corresponding to EBSD scan in panel C. (E) Image quality and local orientation spread (LOS) image of lattice misorientations (yellow to red) that correspond to the sub-parallel shock fractures at arrows. (F) Close-up SEM-BSE image of oriented shock fractures. Medium gray areas represent amorphous silica, as separately confirmed by SAD, FFT, and TEM-EDS.

Figure 14.

[Left column] EBSD images using “orientation deviation” values superimposed on “image quality” values and [right column] EBSD “inverse pole Figure” values superimposed on “image quality” values. (A, D) Grain #10x-12 from Meteor Crater, Arizona. (B, E) Grain #19x-12C from the Russian Joe-1/4 nuclear test. (C, F) Grain #09x11 from Trinity meltglass. The inset legend in panel E shows the color-coded crystalline axes for all six panels. These color patterns (not contoured intensity plots) usually correlate with the sample normal relative to crystal orientation. Orientation deviation analyses (left column) show the crystalline misorientation of the grain relative to an average value. Note that the misorientations tend to align with shock fractures (gray-to-black colored) at the white arrows. Inverse pole Figure analyses (right column) illustrate the rotations of areas around the c-axis. In each Figure, the white arrows mark the black outlines of Dauphiné twins that are rotated 60° around the c-axis of these mono-crystalline quartz grains. Panels D through F display good evidence for Dauphine twinning, i.e., a 60 deg rotation around the c-axis. This twinning is represented by the magenta color in panel D, yellow color in E, and red in F. Note that most Dauphiné twins are oriented along shock fractures (gray-to-black colored), suggesting that the twinning formed synchronously with the shock fractures and is common in all quartz grains from the three sites investigated here.

Figure 14.

[Left column] EBSD images using “orientation deviation” values superimposed on “image quality” values and [right column] EBSD “inverse pole Figure” values superimposed on “image quality” values. (A, D) Grain #10x-12 from Meteor Crater, Arizona. (B, E) Grain #19x-12C from the Russian Joe-1/4 nuclear test. (C, F) Grain #09x11 from Trinity meltglass. The inset legend in panel E shows the color-coded crystalline axes for all six panels. These color patterns (not contoured intensity plots) usually correlate with the sample normal relative to crystal orientation. Orientation deviation analyses (left column) show the crystalline misorientation of the grain relative to an average value. Note that the misorientations tend to align with shock fractures (gray-to-black colored) at the white arrows. Inverse pole Figure analyses (right column) illustrate the rotations of areas around the c-axis. In each Figure, the white arrows mark the black outlines of Dauphiné twins that are rotated 60° around the c-axis of these mono-crystalline quartz grains. Panels D through F display good evidence for Dauphine twinning, i.e., a 60 deg rotation around the c-axis. This twinning is represented by the magenta color in panel D, yellow color in E, and red in F. Note that most Dauphiné twins are oriented along shock fractures (gray-to-black colored), suggesting that the twinning formed synchronously with the shock fractures and is common in all quartz grains from the three sites investigated here.

Table 1.

Characteristics of metamorphism of quartz. Shock micro-fractures investigated in this study share 2 of 10 characteristics with planar deformation features (PDFs), 4 of 10 characteristics with planar fractures (PFs), and 2 of 10 with tectonic deformation lamellae (DLs). The green shading represents features in common with shock fractures in our study. Data are mostly derived from French et al. [

8].

Table 1.

Characteristics of metamorphism of quartz. Shock micro-fractures investigated in this study share 2 of 10 characteristics with planar deformation features (PDFs), 4 of 10 characteristics with planar fractures (PFs), and 2 of 10 with tectonic deformation lamellae (DLs). The green shading represents features in common with shock fractures in our study. Data are mostly derived from French et al. [

8].

Table 2.

Classification of shock stages for quartz. Based on a study of quartz-rich sandstone from Meteor Crater [

32,

33]. The scale ranges from unshocked quartz at shock stage 0 to highly shocked quartz at shock stage 4 and melted quartz glass at shock stage 5. Shock-generated fractures with amorphous silica (glass) first appeared at ~5.0 to 5.5 GPa, as indicated by green highlighting. This classification is from Kowitz et al. [

11], based on

Table 2 of Kieffer [

32,

33] and modified by others [

38,

39].

Table 2.

Classification of shock stages for quartz. Based on a study of quartz-rich sandstone from Meteor Crater [

32,

33]. The scale ranges from unshocked quartz at shock stage 0 to highly shocked quartz at shock stage 4 and melted quartz glass at shock stage 5. Shock-generated fractures with amorphous silica (glass) first appeared at ~5.0 to 5.5 GPa, as indicated by green highlighting. This classification is from Kowitz et al. [

11], based on

Table 2 of Kieffer [

32,

33] and modified by others [

38,

39].