Submitted:

23 May 2023

Posted:

24 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Rat Tumor Tissues for Proteomic Analyses

2.2. Proteomic Analyses

2.3. Histology and Immunohistochemical Analyses

3. Results

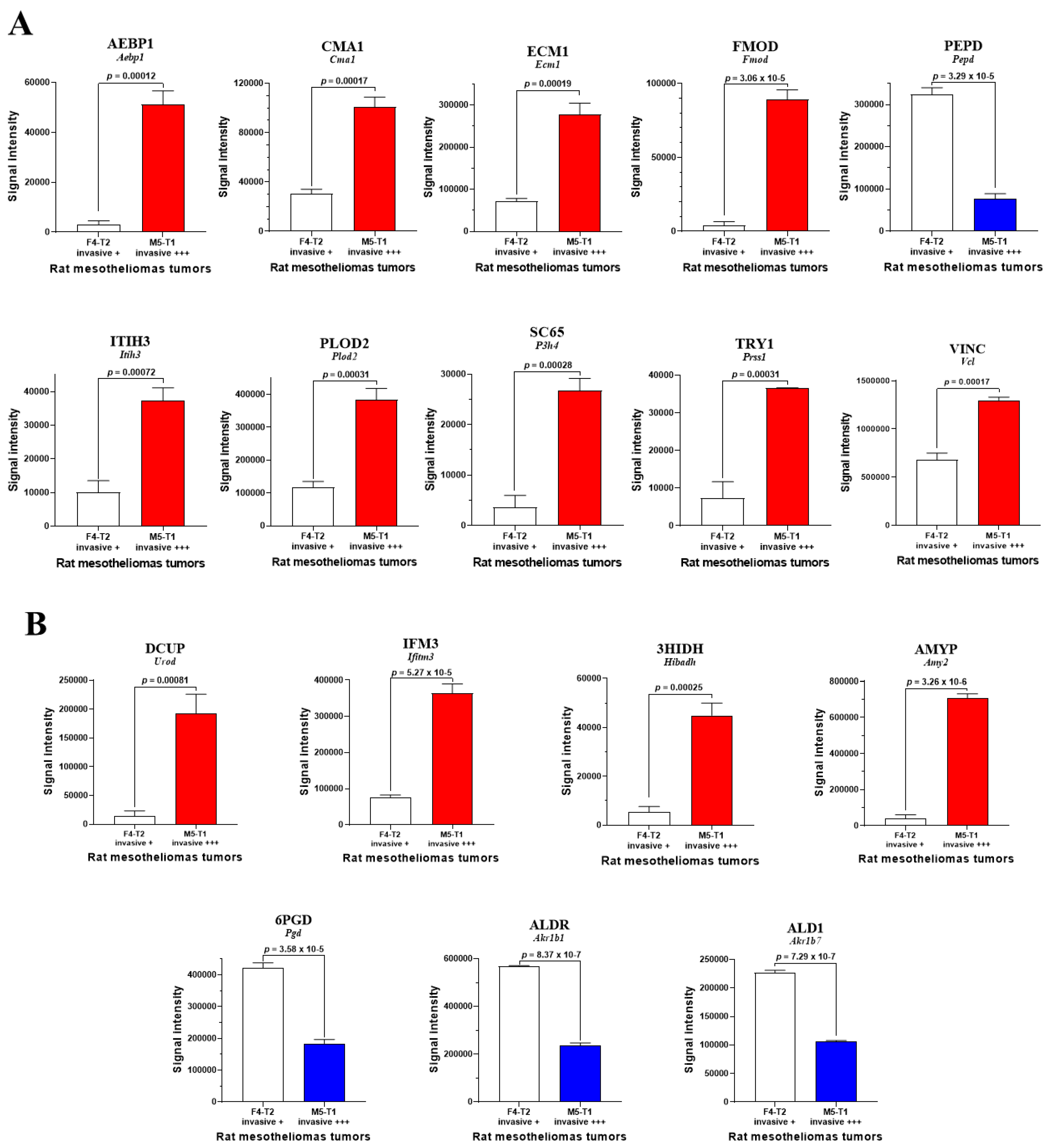

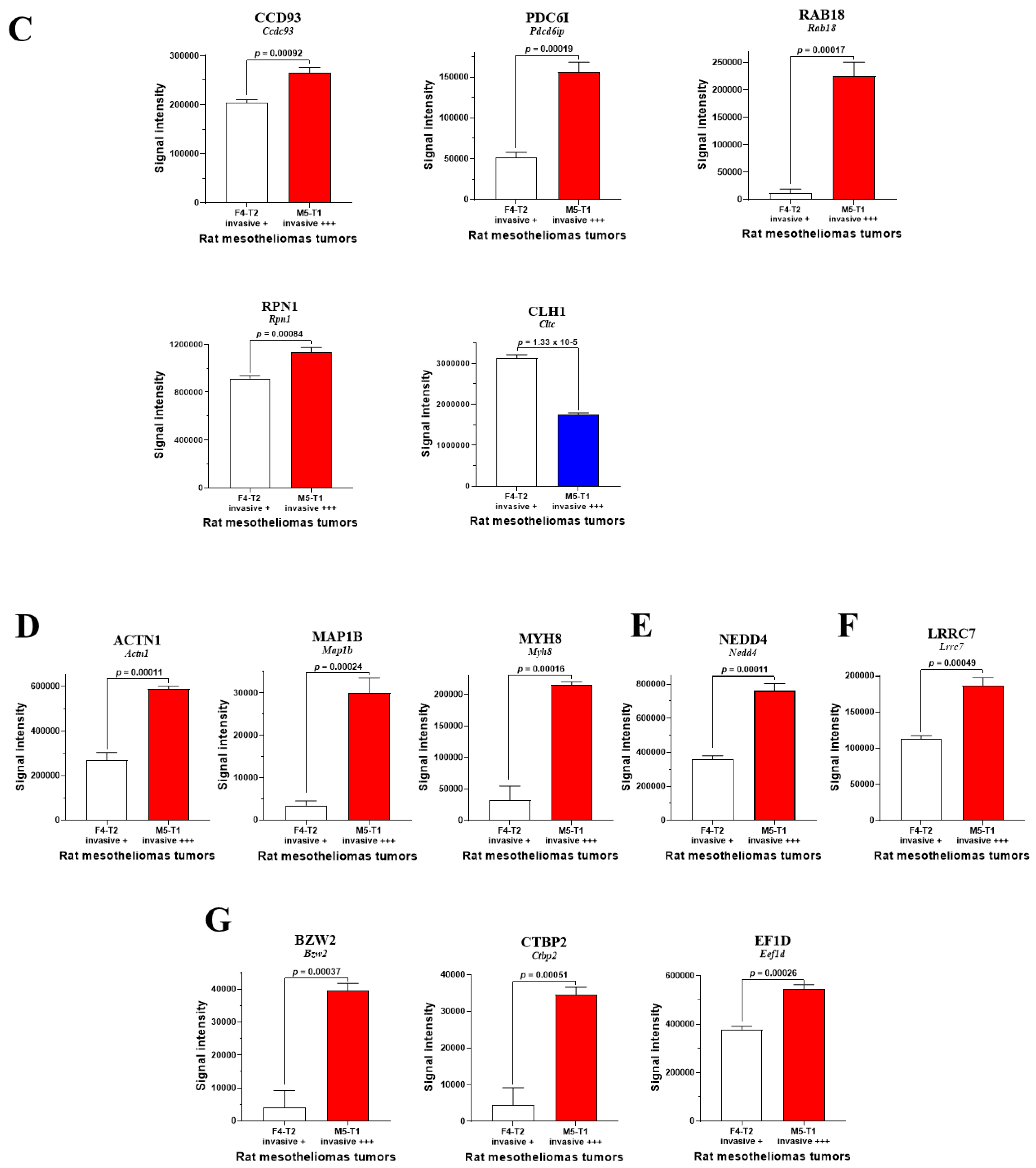

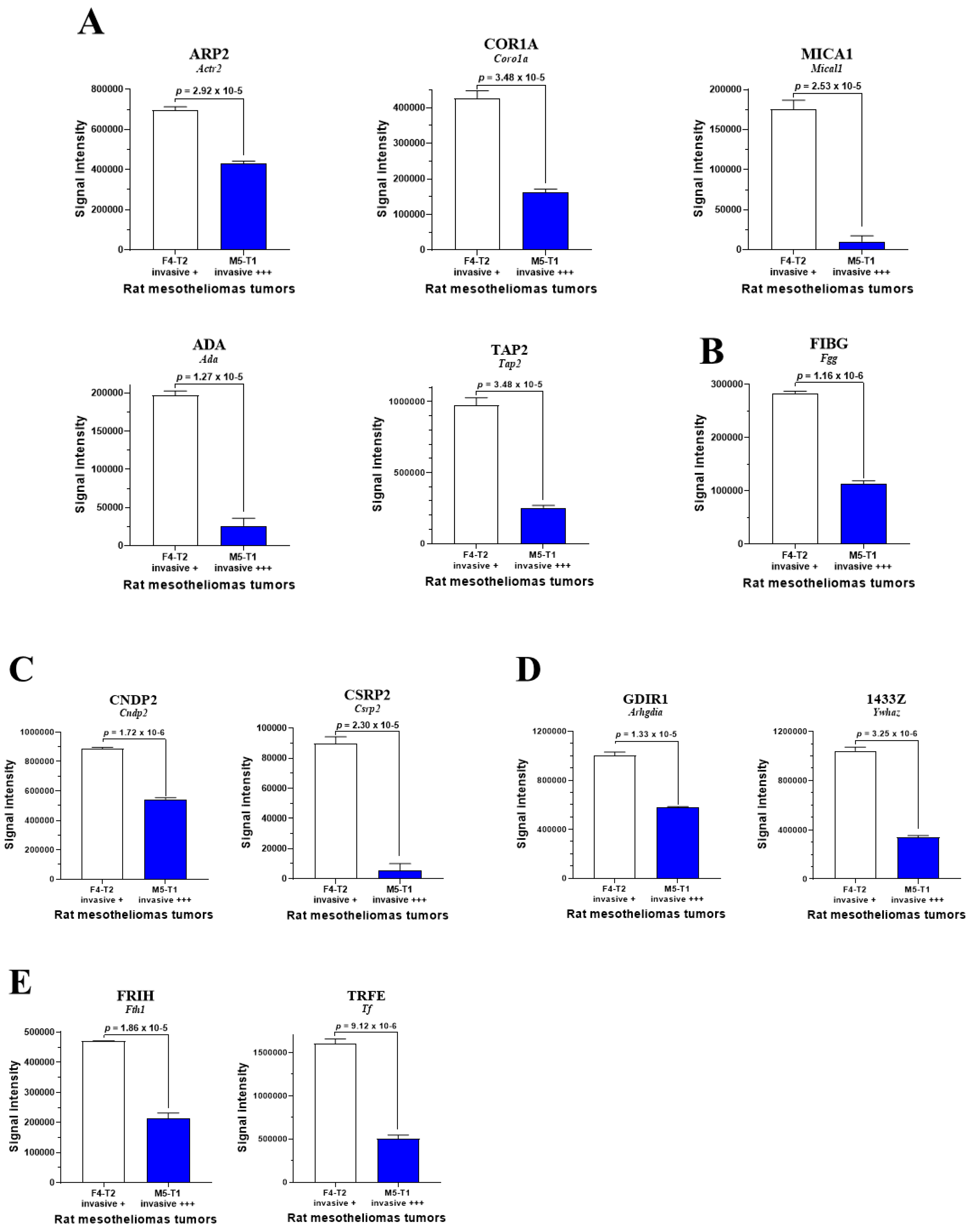

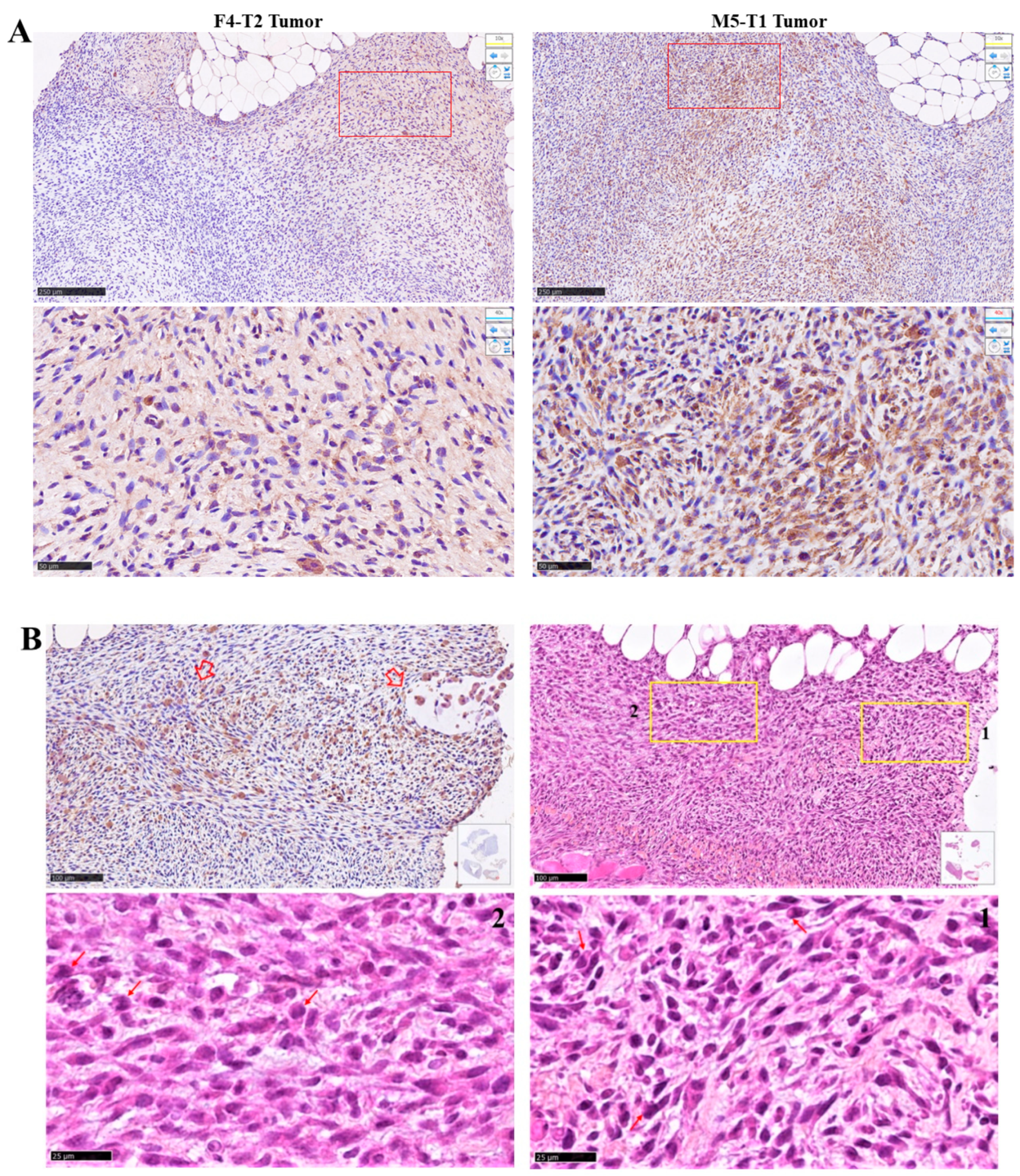

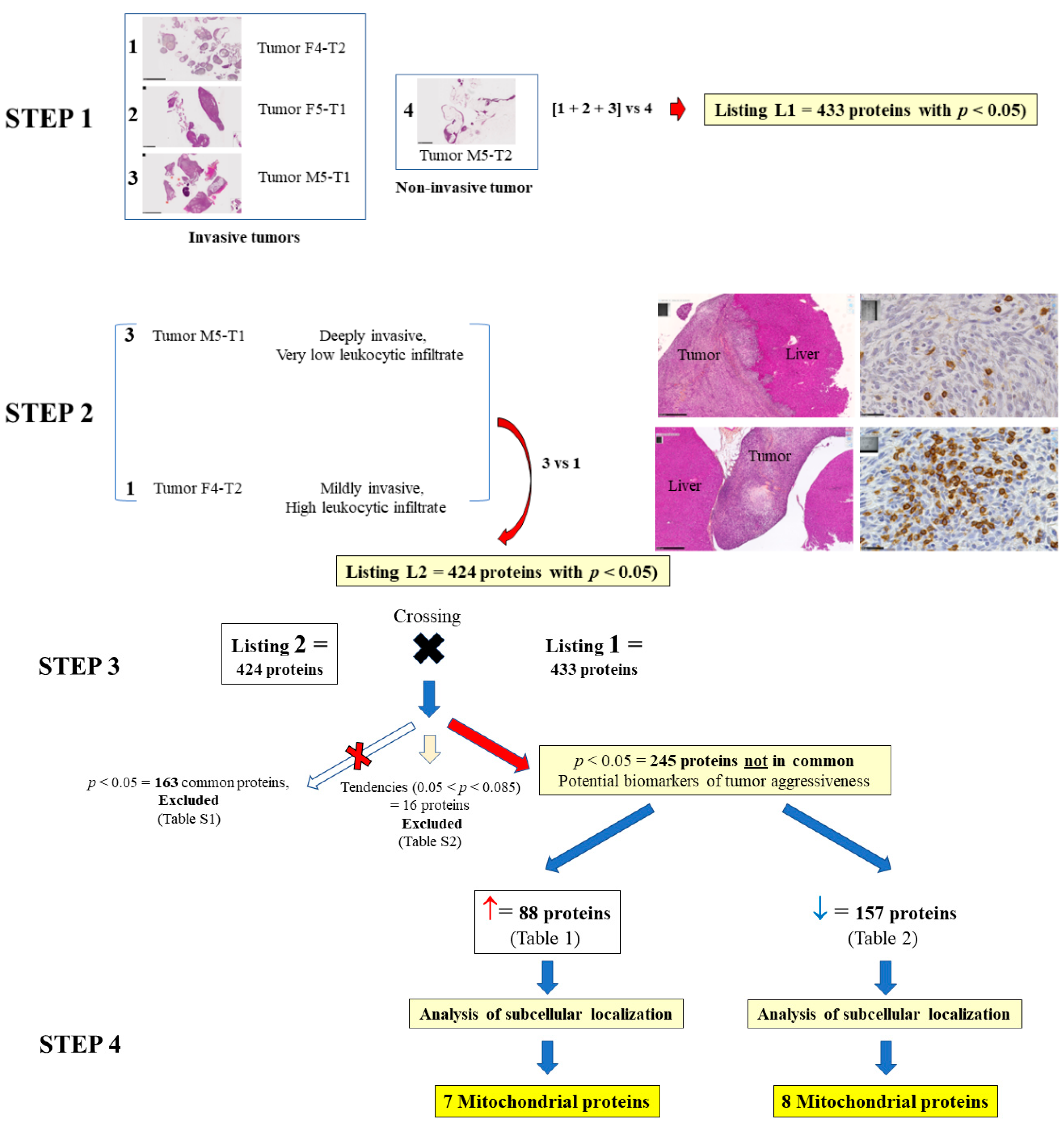

3.1. Biomarkers of Deep Invasiveness and Immunosuppression

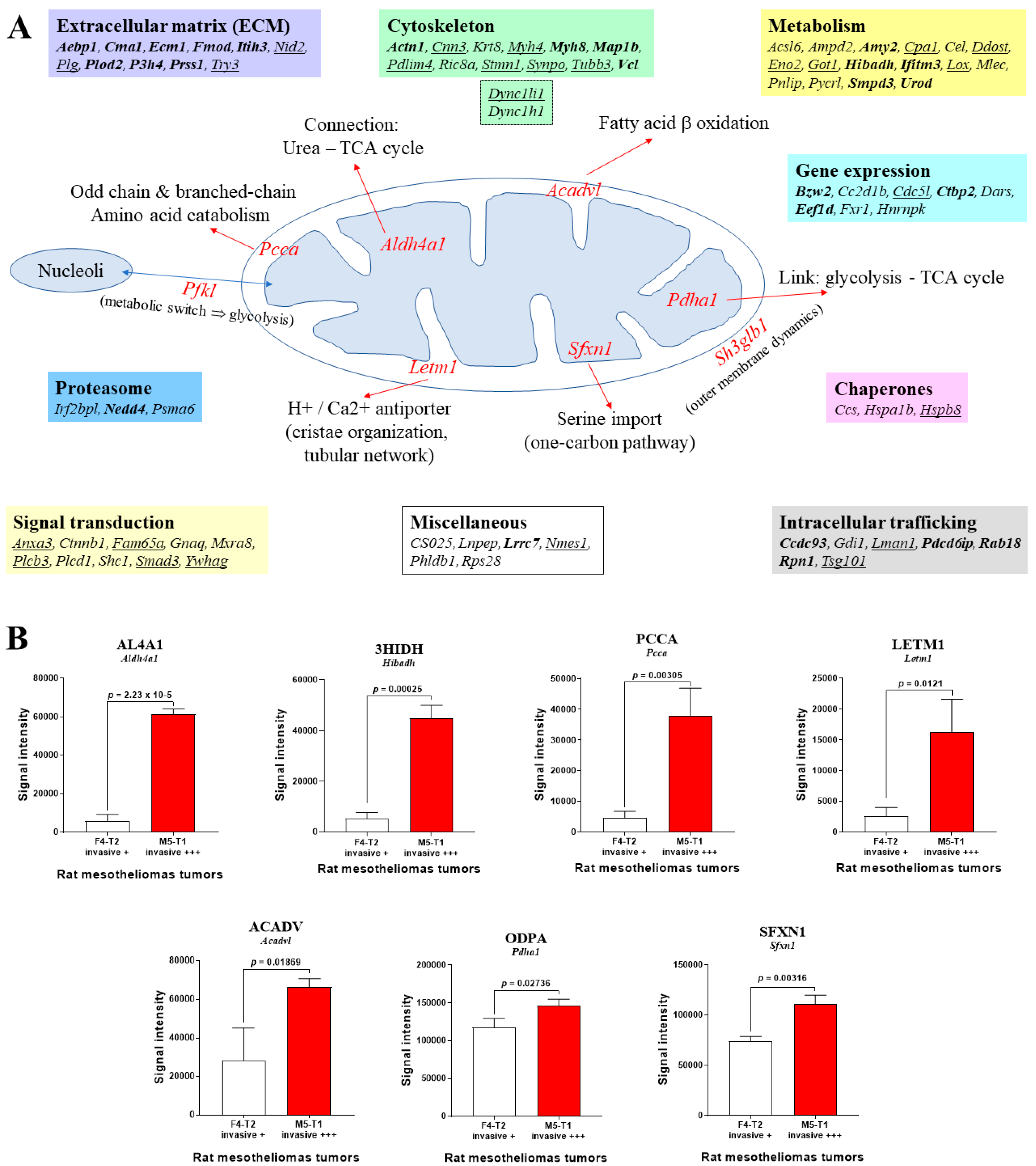

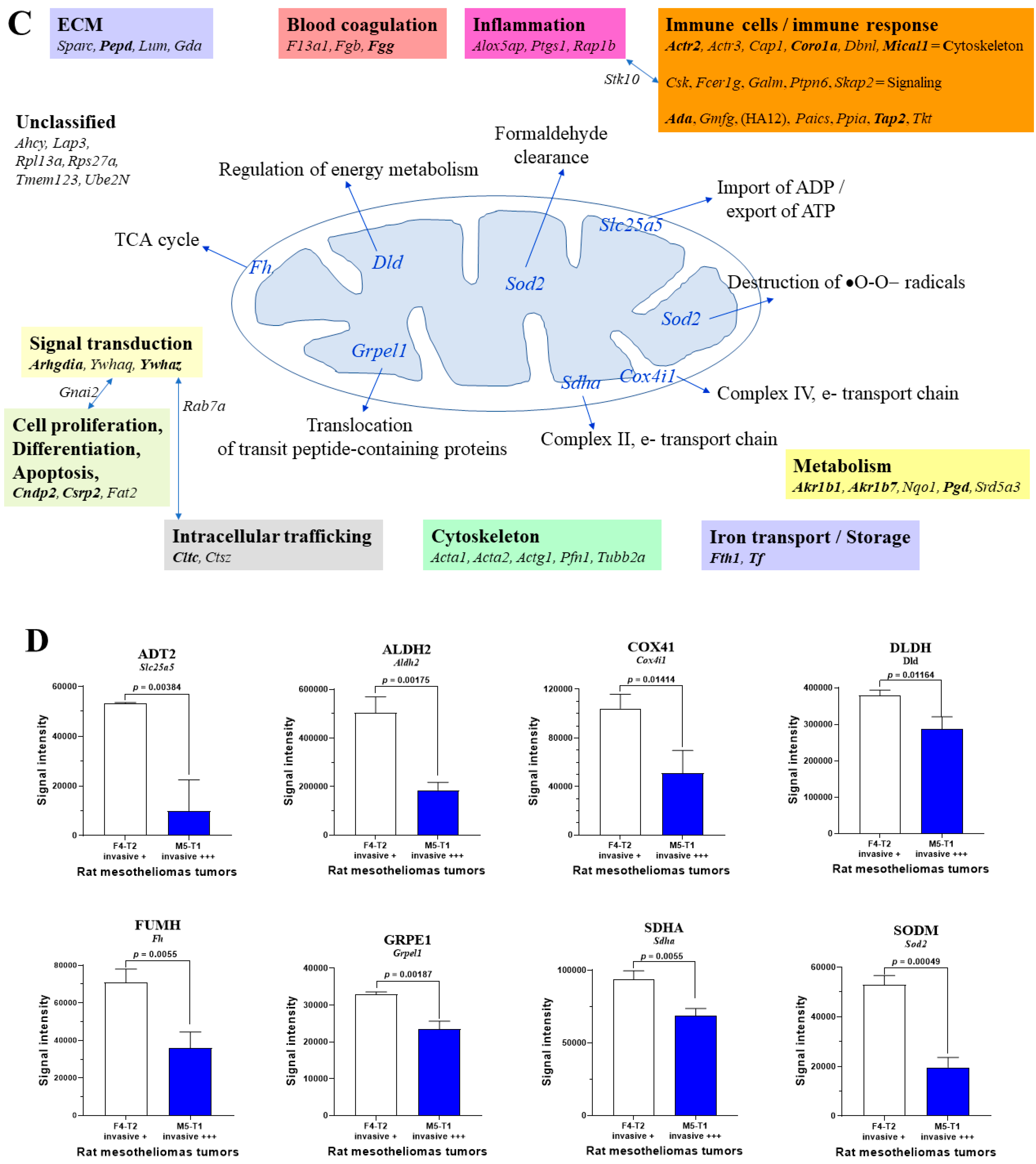

3.2. Mitochondrial Proteins Specifically Changed in the Deeply Invasive M5-T1 Tumor

3.3. Main Abundance Changes in Proteins Representing Potential co-Biomarkers of Aggressiveness

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Inaguma, S.; Ueki, A.; Lasota, J.; Komura, M.; Sheema, A.N.; Czapiewski, P.; Langfort, R.; Rys, J.; Szpor, J.; Waloszczyk, P.; et al. CD70 and PD-L1 (CD274) co-expression predicts poor clinical outcomes in patients with pleural mesothelioma. J. Pathol. Clin. Res. 2023, 9, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eickelschulte, S.; Riediger, A.L.; Angeles, A. K.; Janke, F.; Duensing, F.; Sültmann, H.; Görtz, M. Biomarkers for the detection and risk stratification of aggressive prostate cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 6094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Zhu, J.; Liu, Q.; Shi, Z.; Chambers, M.C.; Zimmerman, L.J.; Shaddox, K.F.; Kim, S.; et al. Proteogenomic characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature 2014, 513, 382–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Jung, M.; Moon, K.C.; Han, D.; Kim, K.; Kim, H.; Yang, S.; Lee, D.; Jun, H.; Lee, K.-M.; et al. Quantitative proteomics identifies TUBB6 as a biomarker of muscle-invasion and poor prognosis in bladder cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2023, 152, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pouliquen, D.L.; Boissard, A.; Henry, C.; Blandin, S.; Richomme, P.; Coqueret, O.; Guette, C. Curcumin treatment identifies therapeutic targets within biomarkers of liver colonization by highly invasive mesothelioma cells – potential links with sarcomas. Cancers 2020, 12, 3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, X.; Liu, R.; Meng, Y.; Xing, D.; Xu, D.; Lu, Z. Lipid metabolism and cancer. J. Exp. Med. 2020, 218, e20201606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.Y.; Ju, M.K.; Jeon, H.M.; Lee, Y.J.; Kim, C.H.; Park, H.G.; Han, S.I.; Kang, H.S. Oncogenic metabolism acts as a prerequisite step for induction of cancer metastasis and cancer stem cell phenotype. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 1027453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellerin, L.; Carrié, L.; Dufau, C.; Nieto, L.; Ségui, B.; Levade, T.; Riond, J.; Andrieu-Abadie, N. Lipid metabolic reprogramming: role in melanoma progression and therapeutic perspectives. Cancers 2020, 12, 3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouliquen, D.L.; Boissard, A.; Henry, C.; Coqueret, O.; Guette, C. Curcuminoids as modulators of EMT in invasive cancers: a review of molecular targets with the contribution of malignant mesothelioma studies. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 934534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, E.; Lazar, I.; Attané, C.; Carrié, L.; Dauvillier, S.; Ducoux-Petit, M.; Esteve, D.; Menneteau, T.; Moutahir, M.; Le Gonidec, S.; et al. Adipocyte extracellular vesicles carry enzymes and fatty acids that stimulate mitochondrial metabolism and remodeling in tumor cells. EMBO J. 2020, 39, e102525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nader, J.S.; Abadie, J.; Deshayes, S.; Boissard, A.; Blandin, S.; Blanquart, C.; Boisgerault, N.; Coqueret, O.; Guette, C.; Grégoire, M.; et al. Characterization of increasing stages of invasiveness identifies stromal/cancer cell crosstalk in rat models of mesothelioma. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 16311–16329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopecka, J.; Gazzano, E.; Castella, B.; Salaroglio, I.C.; Mungo, E.; Massaia, M.; Riganti, C. Mitochondrial metabolism: inducer or therapeutic target in tumor immune-resistance? Semin. Cell Develop. Biol. 2020, 98, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubey, S.; Ghosh, S.; Goswami, D.; Ghatak, D.; De, R. Immunometabolic attributes and mitochondria-associated signaling of tumor-associated macrophages in tumor microenvironment modulate cancer progression. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2023, 208, 115369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angajala, A.; Lim, S.; Phillips, J.B.; Kim, J.-H.; Yates, C.; You, Z.; Tan, M. Diverse roles of mitochondria in immune responses: novel insights into immuno-metabolism. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, H.; Mao, C.; Sun, M.; Dominah, G.; Chen, L.; Zhuang, Z. Fatty acid oxidation contributes to IL-1b secretion in M2 macrophages and promotes macrophage-mediated tumor cell migration. Mol. Immunol. 2018, 94, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Wei, D.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, H.; Li, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Y. FABP5 controls macrophage alternative activation and allergic asthma by selectively programming long-chain unsaturated fatty acid metabolism. Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 111668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoyama, T.; Ueno, I.; Kamijo, T.; Hashimoto, T. Rat very-long chain Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, a novel mitochondrial acyl-CoA dehydrogenase gene product, is a rate-limiting enzyme in long-chain fatty acid b-oxidation system. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 19088–19094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, M.; Gneist, M.; Owa, T.; Dittrich, C. Clinical complete long-term remission of a patient with metastatic malignant melanoma under therapy with indisulam (E7070). Melanoma Res. 2007, 17, 329–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Chen, S.; Pan, X.; Wang, Z.; Han, H.; Zheng, W.; Wang, X.; Li, F.; Qu, S.; Shao, R. Differential gene expression identified in Uigur women cervical squamous cell carcinoma by suppression substractive hybridization. Neoplasma 2010, 57, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedlová, N.; Kokáš, F.Z.; Hupp, T.R.; Vojtěšek, B.; Nekulová, M. IFITM protein regulation and functions: far beyond the fight against viruses. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1042368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, L.J.; Watson, Z.L.; Qamar, L.; Yamamoto, T.M.; Sawyer, B.T.; Sullivan, K.D.; Khanal, S.; Joshi, M.; Ferchaud-Roucher, V.; Smith, H.; et al. Multi-omic approaches identify metabolic and autophagy regulators important in ovarian cancer dissemination. iScience 2019, 19, 474–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tcheng, M.; Roma, A.; Ahmed, N.; Smith, R. W.; Jayanth, P.; Minden, M. D.; Schimmer, A. D.; Hess, D. A.; Hope, K.; Rea, K. A.; et al. Very long chain fatty acid metabolism is required in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2021, 137, 3518–3532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misheva, M.; Kotzamanis, K.; Davies, L.C.; Tyrrell, V.J.; Rodrigues, P.R.S.; Benavides, G.A.; Hinz, C.; Murphy, R.C.; Kennedy, P.; Taylor, P.R.; et al. Oxylipin metabolism is controlled by mitochondrial b-oxidation during bacterial inflammation. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nader, J.S.; Abadie, J.; Deshayes, S.; Boissard, A.; Blandin, S.; Blanquart, C.; Boisgerault, N.; Coqueret, O.; Guette, C.; Grégoire, M. Characterization of increasing stages of invasiveness identifies stromal/cancer cell crosstalk in rat models of mesothelioma. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 16311–16329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Li, Y.; Zhou, L.; Dorfman, R.G.; Liu, L.; Cai, R.; Jiang, C.; Tang, D.; Wang, Y.; Zou, X.; et al. SIRT3 elicited an anti-Warburg effect through HIF1a/PDK1/PDHA1 to inhibit cholangiocarcinoma tumorigenesis. Cancer Med. 2019, 8, 2380–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, L.; Jiang, A.; Zeng, H.; Peng, X.; Song, L. Comprehensive analyses of PDHA1 that serves as a predictive biomarker for immunotherapy response in cancer. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 947372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olou, A.A.; Ambrose, J.; Jack, J.L.; Walsh, M.; Ruckert, M.T.; Eades, A.E.; Bye, B.A.; Dandawate, P.; VanSaun, M.N. SHP2 regulates adipose maintenance and adipocyte-pancreatic cancer cell crosstalk via PDHA1. J. Cell Comm. Signal. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.-M.; Xiang, B.; Yu, Y.-H.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Z.-X.; Zhanghuang, C.; Jin, L.-M.; Wang, J.-K.; Mi, T.; Chen, M.-L.; et al. A novel cuproptosis-related subtypes and gene signature associates with immunophenotype and predicts prognosis accurately in neuroblastoma. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 999849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaude, E.; Frezza, C. Defects in mitochondrial metabolism and cancer. Cancer Metab. 2014, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, I.-M.; Hornick, J.L.; Bovée, J.V.M.G. The roles of metabolic enzymes in mesenchymal tumors and tumor syndromes: genetics, pathology, and molecular mechanisms. Lab. Invest. 2018, 98, 414–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-J.; Hong, W.-F.; Liu, M.-L.; Guo, X.; Yu, Y.-Y.; Cui, Y.-H.; Liu, T.-S.; Liang, L. An integrated bioinformatic investigation of mitochondrial solute carrier family 25 (SLC25) in colon cancer followed by preliminary validation of member 5 (SLC25A5) in tumorigenesis. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhar, S.K.; Tangpong, J.; Chaiswing, L.; Oberley, T.D.; St Clair, D.K. Manganese superoxide dismutase is a p53-regulated gene that switches cancers between early and advanced changes. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 6684–6695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, S.; Savanur, M.A.; Sinha, D.; Birje, A.; R. V.; Saha, P.P.; D’Silva, P. Regulation of mitochondrial protein import by the nucleotide exchange factors GrpEL1 and GrpEL2 in human cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 18075–18090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.-y.; Jiang, L.; Liu, J.-j.; He, T.; Cui, Y.-h.; Qian, F.; Yu, P.-w. AEBP1 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition of gastric cancer cells by activating the NF-kB pathway and predicts poor outcome of the patients. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Chi, F.; Zhou, Y.; Ren, S.; Zhao, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Piao, D. AEBP1, a prognostic indicator, promotes colon adenocarcinoma cell growth and metastasis through the NF-kB pathway. Mol. Carcinogenesis 2019, 58, 1795–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Song, L.; Chang, J.; Cao, P.; Liu, Q. AEBP1 promotes glioblstoma progression and activates the classical NF-kB pathway. Behav. Neurol. 2020, 8890452. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, L.; Shao, X.; Wang, Q.; Jiang, X.; Dai, Y.; Chen, S. Adipocyte enhancer binding protein 1 (AEBP1) knockdown suppresses human glioma cell proliferation, invasion and induces early apoptosis. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2020, 216, 152790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Chen, Z. Inhibition of AEBP1 predisposes cisplatin-resistant oral cancer cells to ferroptosis. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenger, J.M.; Bear, M.D.; Volinia, S.; Lin, T.-Y.; Harrington, B.K.; London, C.A.; Kisseberth, W.C. Overexpression of miR-9 in mast cells is associated with invasive behavior and spontaneous metastasis. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Ye, L.; Chen, Y.; Chen, P. P3H4 is correlated with clinicopathological features and prognosis in bladder cancer. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 16, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Zhou, H.; Song, J.; Cui, H.; Luo, Y.; Jiang, H. P3H4 overexpression seres as a prognostic factor in lung adenocarcinoma. Comput. Math. Meth. Med. 2021, 9971353. [Google Scholar]

- Du, H.; Pang, M.; Hou, X.; Yuan, S.; Sun, L. PLOD2 in cancer research. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 90, 670–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, X.; Wang, A.; Song, W. Clinicopathological significances of PLOD2, epithelial-mesenchymal transition markers, and cancer stem cells in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Medicine 2022, 101, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreße, N.; Schröder, H.; Stein, K.-P.; Wilkens, L.; Mawrin, C.; Sandalcioglu, I.E.; Dumitru, C.A. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6037. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, M.; Liu, X.; Li, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Sun, W.; Li, Z. Silencing PLOD2 attenuates cancer stem cell-like characteristics and cisplatin-resistant through Integrin b1 in laryngeal cancer. Transl. Oncol. 2022, 22, 101460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Fan, G.; Zhu, H.; Yu, L.; She, D.; Wei, Y.; Huang, J.; Li, T.; Zhan, S.; Zhou, S.; et al. PLOD2 high expression associates with immune infiltration and facilitates cancer progression in osteosarcoma. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 980390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, G.-f.; Zhao, L.-d.; Chen, Q.; Tang, D.-x.; Chen, Q.-y.; Lu, H.-f.; Cai, J.-r.; Chen, Z. High ACTN1 is associated with poor prognosis, and ACTN1 silencing suppresses cell proliferation and metastasis in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2020, 14, 1717–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Chen, T.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Z.; Zhao, K.; Zheng, K.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; et al. a-actinin1 promotes tumorigenesis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition of gastric cancer via the AKT/GSK3b/b-catenin pathway. Bioengineered 2021, 12, 5688–5704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Cao, W.; Qiu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, Q.; Gao, Y.; Lu, N. Oroxylin A suppresses ACTN1 expression to inactivate cancer-associated fibroblasts and restrain breast cancer metastasis. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 159, 104981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldmann, W.H.; Auernheimer, V.; Thievessen, I.; Fabry, B. Vinculin, cell mechanics and tumour cell invasion. Cell Biol. Int. 2013, 37, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, C.; Lan, L.; Behrens, A.; Tomaschko, M.; Ruiz, J.; Su, Q.; Zhao, G.; Yuan, C.; Xiao, X.; et al. High expression of vinculin predicts poor prognosis and distant metastasis and associates with influencing tumor-associated NK cell infiltration and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in gastric cancer. Aging 2021, 13, 5197–5225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punwani, D.; Pelz, B.; Yu, J.; Arva, N.C.; Schafernack, K.; Kondratowicz, K.; Makhija, M.; Puck, J.M. Coronin-1A: immune deficiency in humans and mice. J. Clin. Immunol. 2015, 35, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behring, M.; Ye, Y.; Elkholy, A.; Bajpai, P.; Agarwal, S.; Kim, H.-G.; Ojesina, A.I.; Wiener, H.W.; Manne, U.; Shrestha, S.; et al. Immunophenotype-associated gene signature in ductal breast tumors varies by receptor subtype, but the expression of individual signature genes remains consistent. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 5712–5720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aykut, A.; Durmaz, A.; Karaca, N.; Gulez, N.; Genel, F.; Celmeli, F.; Ozturk, G.; Atay, D.; Aydogmus, C.; Kiykim, A.; et al. Severe combined immunodeficiencies: expanding the mutation spectrum in Turkey and identification of 12 novel variants. Scand. J. Immunol. 2022, 95, e13163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucchetti, A.E.; Paillon, N.; Markova, O.; Dogniaux, S.; Hivroz, C.; Husson, J. Influence of external forces on actin-dependent T cell protrusions during immune synapse formation. Biol. Cell 2021, 113, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.C.; Peterfi, Z.; Hoffmann, F.W.; Moore, R.E.; Kaya, A.; Avanesov, A.; Tarrago, L.; Zhou, Y.; Weerapana, E.; Fomenko, D.E.; et al. MsrB1 and MICALs regulate actin assembly and macrophage function via reversible stereoselective methionine oxidation. Mol. Cell 2013, 51, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.-J.; Wang, P.-Z.; Gale, R.P.; Qin, Y.-Z.; Liu, Y.-R.; Lai, Y.-Y.; Jiang, H.; Jiang, Q.; Zhang, X.-H.; Jiang, B.; et al. Cysteine and glycine-rich protein 2 (CSRP2) transcript levels correlate with leukemia relapse and leukemia-free survival in adults with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and normal cytogenetics. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 35984–36000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, C.; Mao, X.; Brown-Clay, J.; Moreau, F.; Al Absi, A.; Wurzer, H.; Sousa, B.; Schmitt, F.; Berchem, G.; Janji, B.; et al. Hypoxia promotes breast cancer cell invasion through HIF-1-mediated up-regulation of the invadopodial actin bundling protein CSRP2. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 10191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Long, X.; Duan, S.; Liu, X.; Chen, J.; Lan, J.; Liu, X.; Huang, W.; Geng, J.; Zhou, J. CSRP2 suppresses colorectal cancer progression via p130Cas/Rac1 axis-mediated ERK, PAK, and HIPPO signaling pathways. Theranostics 2020, 10, 11063–11079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, R.; Wu, Z.; Fan, Y.; Li, M.; Li, M.; Li, T.; Li, Y.; et al. Inhibition of CSRP2 promotes leukemia cell proliferation and correlates with relapse in adults with acute myeloid leukemia. Onco Targets Ther. 2020, 13, 12549–12560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haikazian, S.; Olson, M.F. MICAL1 monooxygenase in autosomal dominant lateral temporal epilepsy: role in cytoskeletal regulation and relation to cancer. Genes 2022, 13, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, H.; Li, Y.; Cui, X.; Cao, H.; Hou, Z.; Ti, Y.; Liu, D.; Gao, J.; Wang, Y.; Wen, P. MICAL1 inhibits colorectal cancer cell migration and proliferation by regulating the EGR1/-catenin signaling pathway. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2022, 195, 114870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, D.F.; Belaguli, N.S.; Chang, J.; Schwartz, R.J. LIM-only protein, CRP2, switched on smooth muscle gene activity in adult cardiac myocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene | Full name |

|---|---|

| Ywhag | 14-3-3 protein gamma |

| Hibadh | 3-hydroxyisobutyrate dehydrogenase, mitochondrial |

| Got1 | Aspartate aminotransferase, cytoplasmic |

| Acadvl | Very long-chain specific acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, mitochondrial |

| Acsl6 | Long-chain-fatty-acid--CoA ligase 6 |

| Actn1 | Alpha-actinin-1 |

| Aebp1 | Adipocyte enhancer-binding protein 1 |

| Aldh4a1 | Delta-1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate dehydrogenase, mitochondrial |

| Ampd2 | AMP deaminase 2 |

| Amy2 | Pancreatic alpha-amylase |

| Anxa3 | Annexin A3 |

| Bzw2 | Basic leucine zipper and W2 domain-containing protein 2 |

| Cc2d1b | Coiled-coil and C2 domain-containing protein 1B |

| Cpa1 | Carboxypeptidase A1 |

| Ccdc93 | REVERSED Coiled-coil domain-containing protein 93 |

| Ccs | Copper chaperone for superoxide dismutase |

| Cdc5l | Cell division cycle 5-like protein |

| Cel | Bile salt-activated lipase |

| Cma1 | Chymase |

| Cnn3 | Calponin-3 |

| / | UPF0449 protein C19orf25 homolog |

| Ctbp2 | C-terminal-binding protein |

| Ctnnb1 | Catenin beta-1 |

| Ctrb1 | Chymotrypsinogen B |

| Dync1li1 | Cytoplasmic dynein 1 light intermediate chain |

| Urod | Uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase |

| Dync1h1 | Cytoplasmic dynein 1 heavy chain 1 |

| Ecm1 | Extracellular matrix protein |

| Eef1d | Elongation factor 1-delta |

| Eno2 | Gamma-enolas |

| Fam65a | Protein FAM65A |

| Fmod | Fibromodulin |

| Fxr1 | Fragile X mental retardation syndrome-related protein 1 |

| Gdi1 | Rab GDP dissociation inhibitor alpha |

| Gnaq | Guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(q) subunit alph |

| Hnrnpk | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K |

| Hspa1b | Heat shock 70 kDa protein 1B |

| Hspb8 | Heat shock protein beta-8 |

| Irf2bpl | Interferon regulatory factor 2-binding protein-like |

| Ifitm3 | Interferon-induced transmembrane protein 3 |

| Itih3 | Inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H3 |

| Krt8 | Keratin, type II cytoskeletal 8 |

| Lnpep | Leucyl-cystinyl aminopeptidase |

| Letm1 | LETM1 and EF-hand domain-containing protein 1, mitochondrial |

| Pnlip | Pancreatic triacylglycerol lipase |

| Lman1 | Protein ERGIC-53 |

| Lrrc7 | Leucine-rich repeat-containing protein 7 |

| Lox | Protein-lysine 6-oxidase |

| Map1b | Microtubule-associated protein 1B |

| Mlec | Malectin |

| Mxra8 | Matrix-remodeling-associated protein 8 |

| Myh4 | Myosin-4 |

| Myh8 | Myosin-8 |

| Ppp1r12a | Protein phosphatase 1 regulatory subunit 12A |

| Nedd4 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase NEDD4 |

| Nid2 | Nidogen-2 |

| Nmes1 | Normal mucosa of esophagus-specific gene 1 protein |

| Smpd3 | Sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase 3 |

| Pdha1 | Pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component subunit alpha, somatic form, mitochondrial |

| Ddost | Dolichyl-diphosphooligosaccharide--protein glycosyltransferase 48 kDa subunit |

| Pycrl | Pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase 3 |

| Pcca | Propionyl-CoA carboxylase alpha chain, mitochondrial |

| Pdcd6ip | Programmed cell death 6-interacting protein |

| Pdlim4 | PDZ and LIM domain protein 4 |

| Pfkl | ATP-dependent 6-phosphofructokinase, liver type |

| Phldb1 | Pleckstrin homology-like domain family B member 1 |

| Plcb3 | 1-phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate phosphodiesterase beta-3 |

| Plcd1 | 1-phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate phosphodiesterase delta-1 |

| Plg | Plasminogen |

| Plod2 | Procollagen-lysine,2-oxoglutarate 5-dioxygenase 2 |

| Psma6 | Proteasome subunit alpha type-6 |

| Rab18 | Ras-related protein Rab-18 |

| Ric8a | Synembryn |

| Rpn1 | Dolichyl-diphosphooligosaccharide--protein glycosyltransferase subunit 1 |

| Rps28 | 40S ribosomal protein S28 |

| P3h4 | Synaptonemal complex protein SC65 |

| Sfxn1 | Sideroflexin-1 |

| Shc1 | SHC-transforming protein 1 |

| Sh3glb1 | Endophilin-B1 |

| Smad3 | Mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 3 |

| Stmn1 | Stathmin |

| Dars | Aspartate--tRNA ligase, cytoplasmic |

| Synpo | Synaptopodin |

| Tubb3 | Tubulin beta-3 chain |

| Prss1 | Anionic trypsin-1 |

| Try3 | Cationic trypsin-3 |

| Tsg101 | Tumor susceptibility gene 101 protein |

| Vcl | Vinculin |

| Vkorc1l1 | Vitamin K epoxide reductase complex subunit 1-like protein 1 |

| Gene name | Full protein name |

|---|---|

| Ywhaq | 14-3-3 protein theta |

| Ywhaz | 14-3-3 protein zeta/delta |

| Slc3a2 | 4F2 cell-surface antigen heavy chain |

| Pgd | 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase, decarboxylating |

| Xdh | Xanthine dehydrogenase/oxidase |

| Yap1 | Transcriptional coactivator YAP1 |

| Acta2 | Actin, aortic smooth muscle |

| Actg1 | Actin, cytoplasmic 2 |

| Acta1 | Actin, alpha skeletal muscle |

| Ada | Adenosine deaminase |

| Slc25a5 | ADP/ATP translocase 2 |

| Aif1 | Allograft inflammatory factor 1 |

| Akr1a1 | Alcohol dehydrogenase [NADP(+)] |

| Alox5ap | Arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase-activating protein |

| Aldh9a1 | 4-trimethylaminobutyraldehyde dehydrogenase |

| Akr1b7 | Aldose reductase-related protein 1 |

| Aldh2 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase, mitochondrial |

| Akr1b1 | Aldose reductase |

| Rnpep | Aminopeptidase B |

| Lap3 | Cytosol aminopeptidase |

| Anxa6 | Annexin A6 |

| Ap1b1 | AP-1 complex subunit beta-1 |

| Ap2a2 | AP-2 complex subunit alpha-2 |

| Aprt | Adenine phosphoribosyltransferase |

| Arpc1b | Actin-related protein 2/3 complex subunit 1B |

| Actr2 | Actin-related protein 2 |

| Actr3 | Actin-related protein 3 |

| Arpc2 | Actin-related protein 2/3 complex subunit 2 |

| B2m | Beta-2-microglobulin |

| C1qb | Complement C1q subcomponent subunit B |

| Canx | Calnexin |

| Cand1 | Cullin-associated NEDD8-dissociated protein 1 |

| Cap1 | Adenylyl cyclase-associated protein 1 |

| Capzb | F-actin-capping protein subunit beta |

| Casp1 | Caspase-1 |

| Ctsz | Cathepsin Z |

| Capza2 | F-actin-capping protein subunit alpha-2 |

| Ccdc50 | Coiled-coil domain-containing protein 50 |

| Cltc | Clathrin heavy chain 1 |

| Cndp2 | Cytosolic non-specific dipeptidase |

| Cfl1 | Cofilin-1 |

| Copb2 | Coatomer subunit beta' |

| Coro1a | Coronin-1A |

| Coro1b | Coronin-1B |

| Coro7 | Coronin-7 |

| Cotl1 | Coactosin-like protein |

| Cox4i1 | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 4 isoform 1, mitochondrial |

| Csk | Tyrosine-protein kinase CSK |

| Csrp2 | Cysteine and glycine-rich protein 2 |

| Cux1 | Homeobox protein cut-like 1 |

| Dab2 | Disabled homolog 2 |

| Dbnl | Drebrin-like protein |

| Dld | Dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase, mitochondrial |

| Emc2 | ER membrane protein complex subunit 2 |

| Exoc4 | Exocyst complex component 4 |

| F13a1 | Coagulation factor XIII A chain |

| Fabp5 | Fatty acid-binding protein, epidermal |

| Fat2 | Protocadherin Fat 2 |

| Fcerg1 | High affinity immunoglobulin epsilon receptor subunit gamma |

| Fga | Fibrinogen alpha chain |

| Fgb | Fibrinogen beta chain |

| Fgg | Fibrinogen gamma chain |

| Fkbp9 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase FKBP9 |

| Fnta | Protein farnesyltransferase/geranylgeranyltransferase type-1 subunit alpha |

| Fth1 | Ferritin heavy chain |

| Fh | Fumarate hydratase, mitochondrial |

| Galm | Aldose 1-epimerase |

| Gdi2 | Rab GDP dissociation inhibitor beta |

| Arhgdia | Rho GDP-dissociation inhibitor 1 |

| Gphn | Gephyrin |

| Gimap4 | GTPase IMAP family member 4 |

| Gmfg | Glia maturation factor gamma |

| Gnai2 | Guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(i) subunit alpha-2 |

| Gpsm3 | G-protein-signaling modulator 3 |

| Hspa5 | 78 kDa glucose-regulated protein |

| Grpel1 | GrpE protein homolog 1, mitochondrial |

| Gda | Guanine deaminase |

| Hist1h4b | Histone H4 |

| / | RT1 class I histocompatibility antigen, AA alpha chain |

| Hexb | Beta-hexosaminidase subunit beta |

| Hmgn5 | High mobility group nucleosome-binding domain-containing protein 5 |

| Eif2s3 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 subunit 3, X-linked |

| Ilkap | Integrin-linked kinase-associated serine/threonine phosphatase 2C |

| Irgm | Immunity-related GTPase family M protein |

| Ckb | Creatine kinase B-type |

| Lasp1 | LIM and SH3 domain protein 1 |

| Lta4h | Leukotriene A-4 hydrolase |

| Lrrc15 | Leucine-rich repeat-containing protein 15 |

| Lum | Lumican |

| Gaa | Lysosomal alpha-glucosidase |

| Lyn | Tyrosine-protein kinase Lyn |

| Mical1 | [F-actin]-methionine sulfoxide oxidase MICAL1 |

| Mpdz | Multiple PDZ domain protein |

| Mx1 | Interferon-induced GTP-binding protein Mx1 |

| Nqo1 | NAD(P)H dehydrogenase [quinone] 1 |

| Ncl | Nucleolin |

| Pdcd4 | Programmed cell death protein 4 |

| Pdia3 | Protein disulfide-isomerase A3 |

| Pepd | Xaa-Pro dipeptidase |

| Ptgs1 | Prostaglandin G/H synthase 1 |

| Pip4k2a | Phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphate 4-kinase type-2 alpha |

| Srd5a3 | Polyprenol reductase |

| Tmem123 | Porimin |

| Ppp2ca | Serine/threonine-protein phosphatase 2A catalytic subunit alpha isoform |

| Ppia | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase |

| Pfn1 | Profilin-1 |

| Psmc5 | 26S protease regulatory subunit 8 |

| Psmb1 | Proteasome subunit beta type-1 |

| Ptbp3 | Polypyrimidine tract-binding protein 3 |

| Ptpn6 | Tyrosine-protein phosphatase non-receptor type 6 |

| Ptprc | Receptor-type tyrosine-protein phosphatase C |

| Ppat | Amidophosphoribosyltransferase |

| Paics | Multifunctional protein ADE2 |

| Rab1A | Ras-related protein Rab-1A |

| Rab7a | Ras-related protein Rab-7a |

| Rap1b | Ras-related protein Rap-1b |

| Renbp | N-acylglucosamine 2-epimerase |

| Rhoa | Transforming protein RhoA |

| Rpl11 | 60S ribosomal protein L11 |

| Rpl13a | 60S ribosomal protein L13a |

| Rpl23a | 60S ribosomal protein L23a |

| Rpl3 | 60S ribosomal protein L3 |

| Rpl7 | 60S ribosomal protein L7 |

| Rpl7a | 60S ribosomal protein L7a |

| Rpl8 | 60S ribosomal protein L8 |

| Hnrnpa1 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 |

| Rps2 | 40S ribosomal protein S2 |

| Rps27a | Ubiquitin-40S ribosomal protein S27a |

| Rps29 | 40S ribosomal protein S29 |

| Ahcy | Adenosylhomocysteinase |

| Ahcyl1 | Adenosylhomocysteinase 2 |

| Sec11a | Signal peptidase complex catalytic subunit SEC11A |

| Sdha | Succinate dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] flavoprotein subunit, mitochondrial |

| Sept9 | Septin-9 |

| Skap2 | Src kinase-associated phosphoprotein 2 |

| Smc1a | Structural maintenance of chromosomes protein 1A |

| Snap23 | Synaptosomal-associated protein 23 |

| Snx1 | Sorting nexin-1 |

| Snx3 | Sorting nexin-3 |

| Sod2 | Superoxide dismutase [Mn], mitochondrial |

| Sparc | SPARC |

| Srgap2 | SLIT-ROBO Rho GTPase-activating protein 2 |

| Stk10 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase 10 |

| Wars | Tryptophan--tRNA ligase, cytoplasmic |

| Tap2 | Antigen peptide transporter 2 |

| Tuba1c | Tubulin alpha-1C chain |

| Tubb2a | Tubulin beta-2A chain |

| Tubb5 | Tubulin beta-5 chain |

| Cct2 | T-complex protein 1 subunit beta |

| Cct4 | T-complex protein 1 subunit delta |

| Txn | Thioredoxin |

| Thy1 | Thy-1 membrane glycoprotein |

| Tkt | Transketolase |

| Tmed7 | Transmembrane emp24 domain-containing protein 7 |

| Tf | Serotransferrin |

| Txnl1 | Thioredoxin-like protein 1 |

| Ube2n | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 N |

| Ubxn1 | UBX domain-containing protein 1 |

| Ugt1a6 | UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1-6 |

| Ufl1 | E3 UFM1-protein ligase 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).