1. Introduction

The oxidation reactions are very usual in the cells although they can produce Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and free radicals [

1]. Oxygen free radicals are products of normal cellular metabolism and participate as signaling molecules in the regulation of physiological functions and in redox-regulatory mechanisms of cells in order to protect cells against oxidative stress [

2]. However, excessive production of free radicals causes oxidative damage to biomolecules (DNA, lipids, proteins) and is associated with development of different pathological conditions of the body [

2]. The harmful effect of free radicals is termed oxidative stress. Inhibition of oxidative stress can block (suppress) the damage or death of neuronal cells, thus much attention to substances with antioxidant properties is paid. Antioxidants inhibit the oxidation of biomolecules, prevent cell damage and protect the body from the effects of free radicals [

3]. As some synthetic antioxidants may cause hepatic toxicity, have endocrine disrupting effects or even be carcinogenic [

4], the greatest attention to medicinal plants known or researched to have antioxidant or neuroprotective effects is on the focus. One such plant is Oregano, used by people for thousands of years.

Oregano is one of the most cultivated aromatic plants in the world. The genus

Origanum L. (Lamiaceae) consists of 43 species and 15 hybrids [

5]. All Origanum species are rich in volatile oils and more than one hundred nonvolatile compounds have already been identified in this plant which includes flavonoids, depsides and origanosides [

6]. This abundance of biologically active compounds leads to the different biological properties of Origanum such as antioxidant, antimicrobial, antifungal, antitumor, cytotoxic activity, as well as anti-inflammatory, antispasmodic, antitussive, expectorant properties [

1,

5,

7,

8]. Therefore, it is widely use in the treatment of various diseases, such as rheumatism, muscle pains, indigestion, diarrhoea, headache and asthma [

7]. Medicinal properties are attributed to the antioxidant activity of essential oil and soluble phenolic fractions [

1,

16]. However, there are no consistent studies demonstrating what substances determine the antioxidant activity of Oregano. Some studies attribute the antioxidant activity to the presence of rosmarinic acid [

9,

10] or to phenolic compounds in the extracts [

1,

11,

12]. However, the antioxidant properties of Oregano are most often attributed to the main components of its essential oil - carvacrol and thymol [

8,

13].

Origanum vulgare L. is the most commonly studied, our previous study showed the largest amount of carvacrol in

Origanum onites L. [

9,

17]. Although primary responsibility for the properties of these plants is the essential oils [

1] significant attention is also paid to extract research.

However, essential oils have some disadvantages such as poor solubility, high volatility, sensitivity to UV light and heat and this limit the industrial application of essential oils [

14]. It is reported that encapsulation of biologically active compounds is an effective way to increase the stability of it. One of the widely used methods of nanoencapsulation is liposome technology. Liposomes as a carrier system of essential oils can improve the stability, solubility and bioavailability of bioactive compounds. Liposomes depict spherical bilayer membranes, which are formed by combining one or more various amphipathic phospholipids, yielding nanovesicles (i.e., nanoliposomes) with an aqueous inner core, a hydrophilic inner and outer phosphate surface layer, and a hydrophobic lipid bilayer. It has been studied that liposomes as carriers can not only to ensure compliance of the physicochemical properties with the proposed stability properties of the active compounds, but also increase the absorption of active substances, prolongs the release of the drug [

15].

Both, essential oils and extracts from aerial parts of the plants are used widely because the combination of the compounds present in them seems to be responsible of the activity of these plants, all acting synergistically [

1]. Although the essential oil and extract of Oregano have different compositions of biologically active compounds, both have antioxidant properties. Oregano extracts and essential oils are mainly studied in vitro [

16], while data on their antioxidant role in vivo are limited [

10]. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the antioxidant activity of

O. onites L. in vivo and to evaluate the effect of

O. onites L. extract and liposomes with OE. on oxidative stress markers (the concentrations of glutathione (GSH) and malondialdehyde (MDA)) in mice organs (the liver and brain). The obtained data allows to compare the effects of these preparations on the antioxidant system in the body.

3. Discussion

Liposomes as a nano delivery system was used in this research due to excellent encapsulation efficiency, biocompatibility and safety [

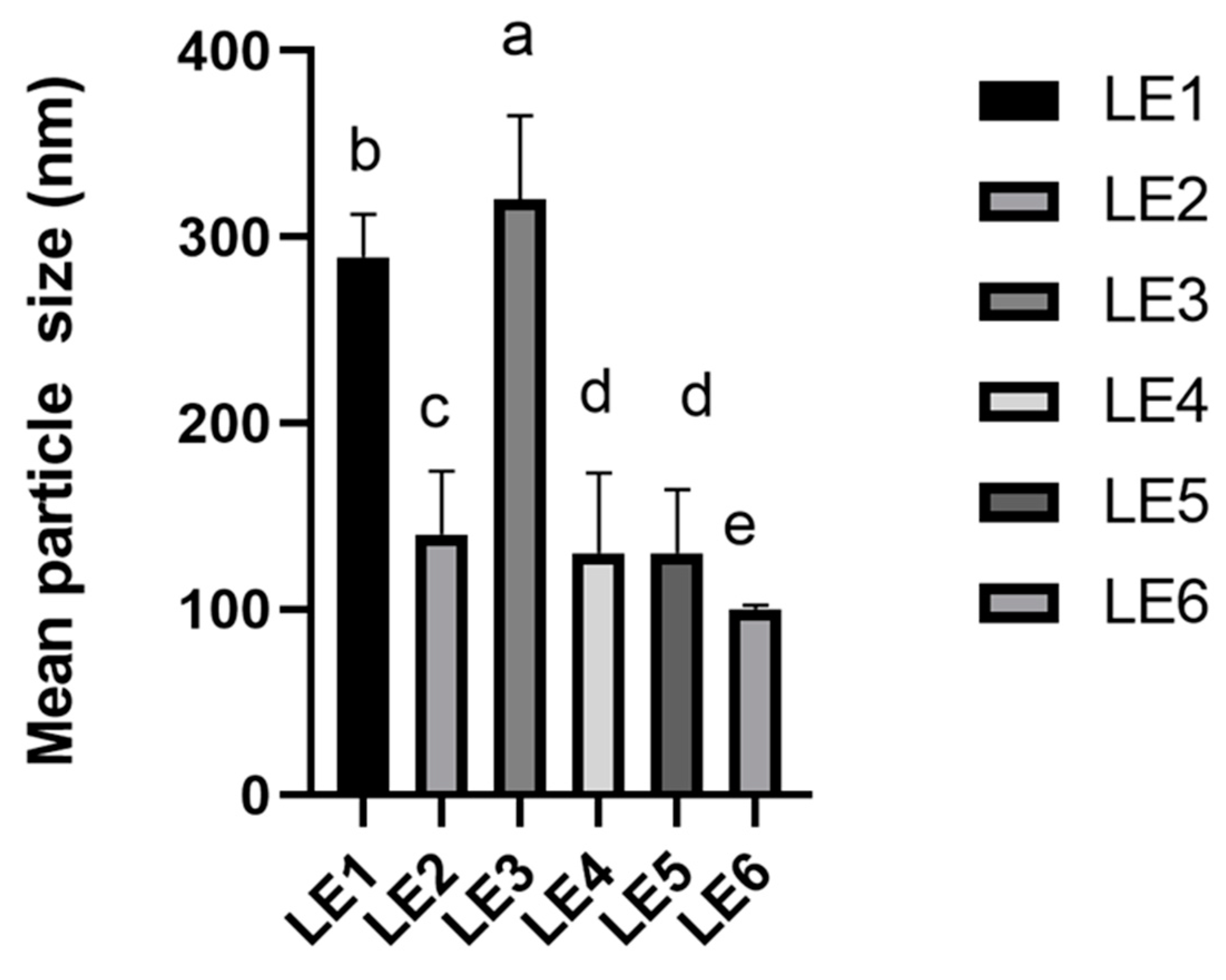

21]. The physicomechanical properties of liposome formulation was measured. The mean particle size of lipid nanocarriers are one of the most important parameters in the evaluation the quality of produced liposomes. The obtained results showed that the mean particle size of the produced formulations depended on the ratio of phospholipid in the mixture. According to scientific publications, if the size of liposome is between 70 nm and 200 nm, it is considered stable, they last longer in the systemic circulation and has a higher probability of reaching the desired target site [

22]. Results showed that the mean particle size of the formulations met the requirements. Moreover, the results showed that the increase in mean particle size in the OE loaded formulations was influenced by increasing amount of essential oil. These results could be explained by the chemical structure of OE with increasing hydrophobic phase the interaction with the acyl group in the phospholipid increases, so the transfer across the membrane layer may deteriorate [

15]. Lastly the homogeneous particle size distribution was obtained of the OE loaded liposome formulation produced by mixture of Lipoid S75 and Lipoid S100 phospholipids [

15].

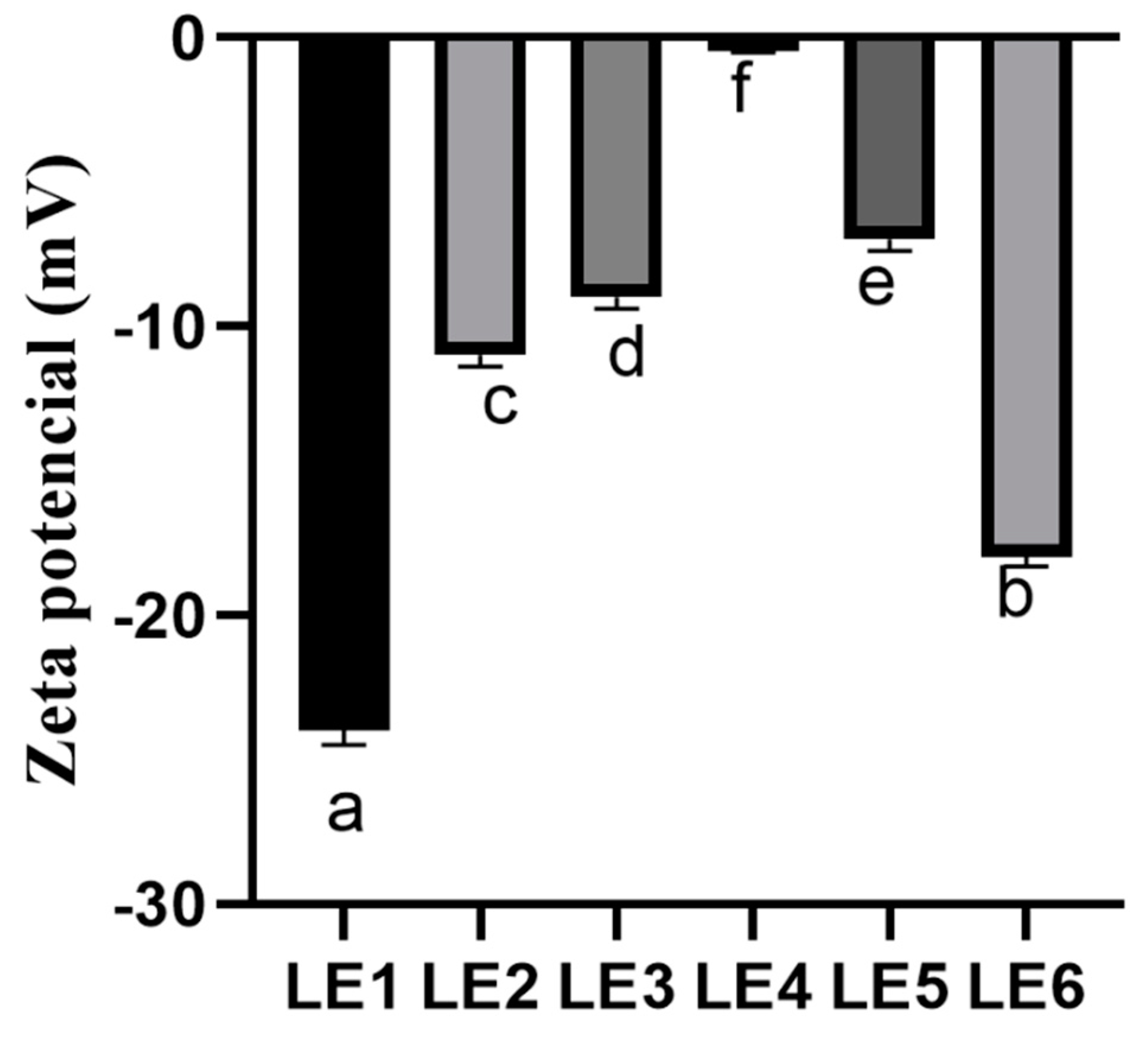

Zeta potential is an important parameter in evaluating the physical stability of lipid nanocarriers. According to literature, nanocarriers are considered to be stable if the zeta potential of the particles is <-30 mV or > 30 mV [

23]. The produced formulations were stable. Furthermore, physical stability of the formulations was influenced by the phospholipid mixture. Eroğlu with co-authors (2014) in the research used phospholipid Lipoid S100 to form the lipid nanocarriers and zeta potential of produced lipid nanocarriers ranged from −28.90 ± 0.80 mV to −24.50 ± 0.60 mV [

24]. Moreover, in another study, liposomes were produced with phospholipids Lipoid S75 and zeta potential reached -12.6±0.6 mV [

25]. Summarizing the results of other authors, it can be stated that in order to produce stable nanoparticles, it is relevant to choose a mixture of Lipoid S75 and Lipoid S100 phospholipids for the formulation of lipid nanocarriers. Lastly, only in LE3 formulation the PDI was greater than 0.3. The instability of the formulation could be explained by increased amount of essential oil. Moreover, this instability could be explained by chemical structure of OE the active compounds can interact with membrane layer. The obtained results was in agreement with other authors [

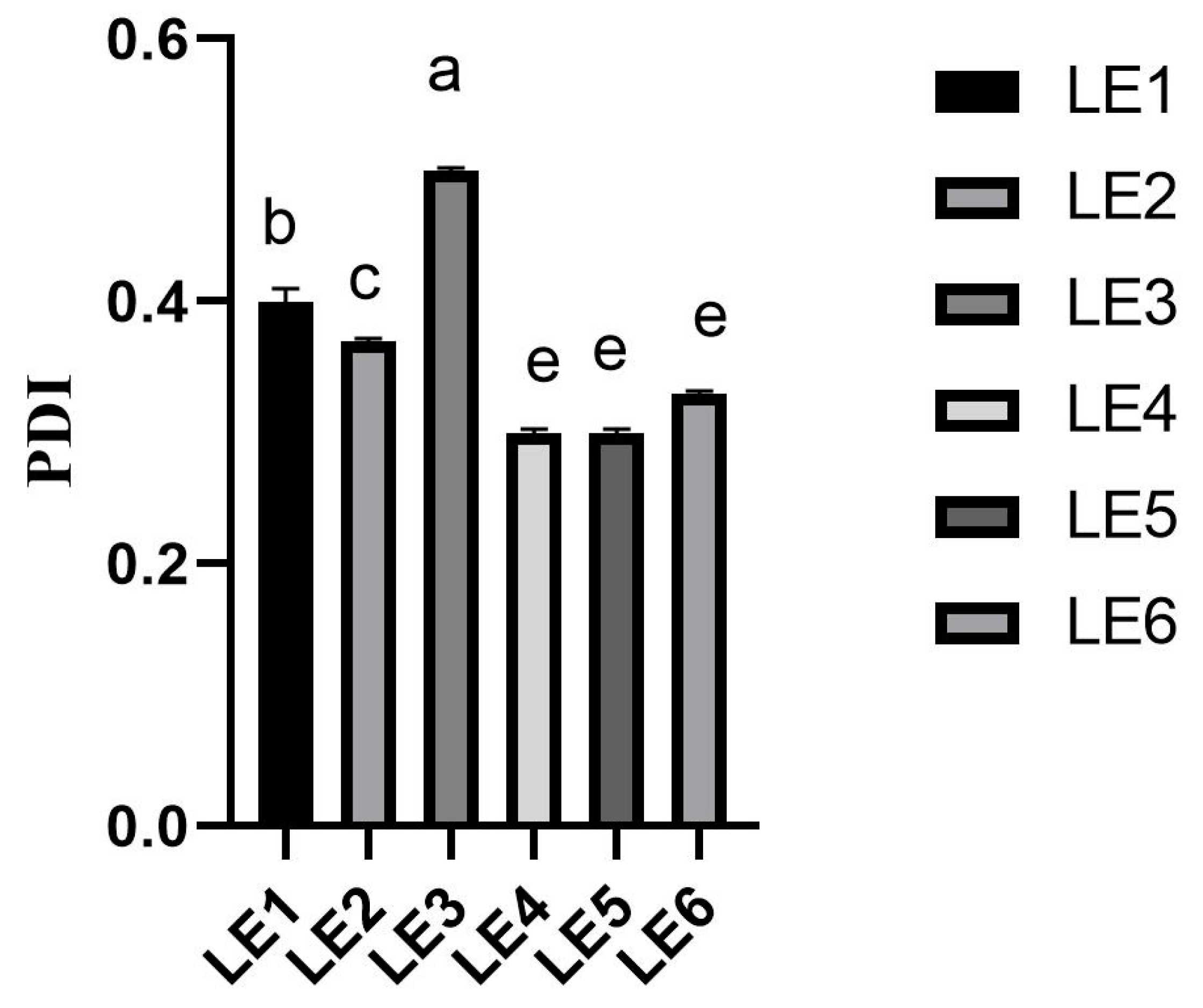

17].

PDI value is significant factor in terms of showing the size distribution of liposomes and being correlated with distribution stability. A PDI value of 1.0 specifies a very wide size distribution or the presence of large particles that can precipitate. An optimum PDI value is 0.30 or less, indicating that 66.7% of nanovesicles are the same size [

26]. The all prepared formulations had the homogenous particle size.

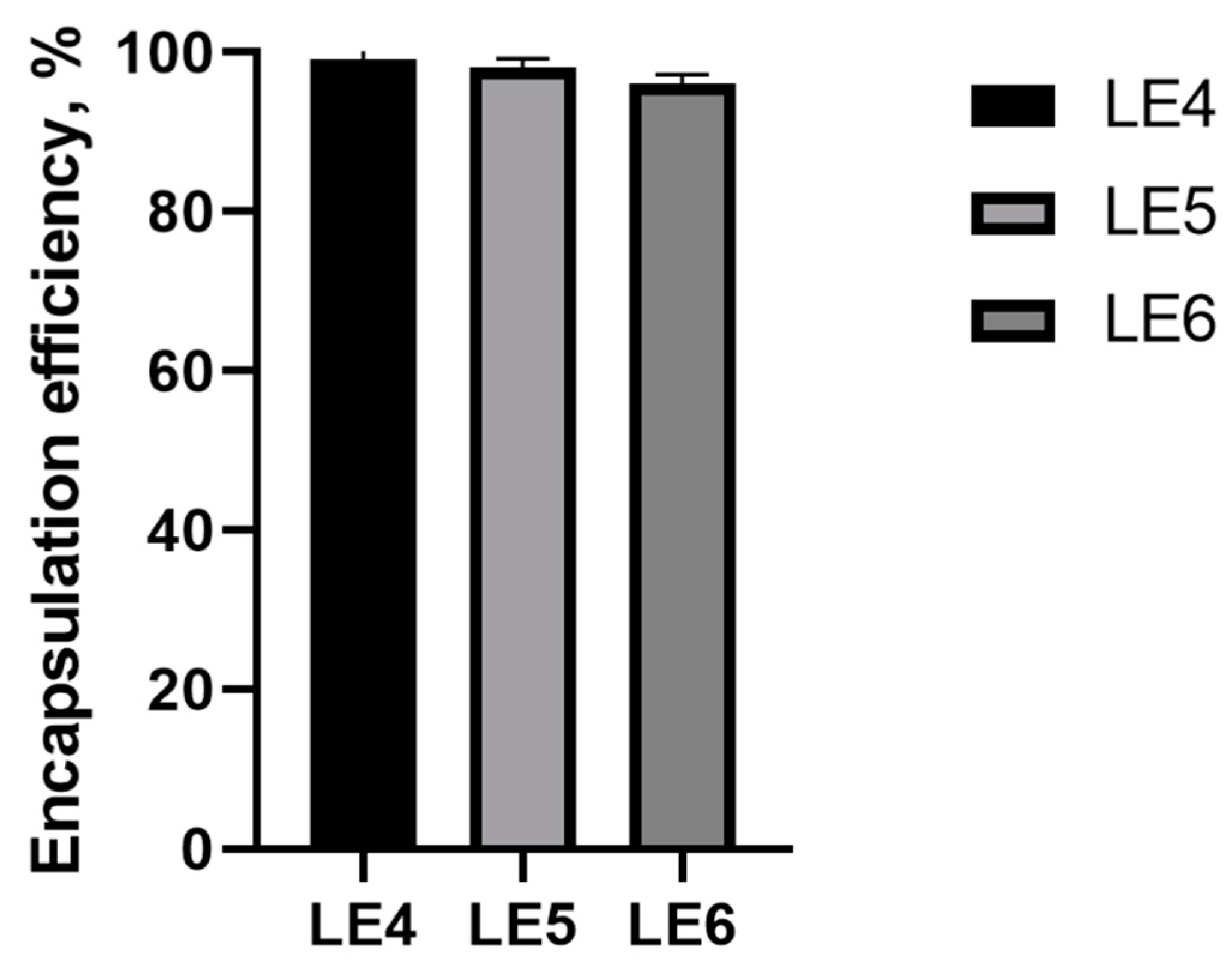

In order to evaluate the quality of lipid nanocarriers, it is important to determine the active compounds encapsulation efficiency and it should be close to 100%, then the maximum amount of active compounds is encapsulated in lipid carriers [

15]. The obtained results showed that increased lipid concentration in the formulation could affect the encapsulation efficiency results. The highest encapsulated amount of carvacrol was obtained in formulation with a mixture ratio of essential oil and phospholipids (Lipoid S75 and Lipoid S100) of 1:5. It has been observed that the encapsulation ability decreases as the lipid concentration decreases in the formulation [

15].

A wide spectrum of important classes of active principles were detected in Oregano, such as essential oil (with carvacrol and/or thymol, linalool, and p-cymene), polyphenols (flavonoids and phenolic acids), triperpenoids, and sterols [

10]. Terpenes, mainly carvacrol and thymol, are characteristic and main active compounds of the essential oil of Oregano species [

7] which have the highest antioxidant effect [

13]. Studies have demonstrated the antioxidant, neuroprotective, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antiviral, antiproliferative, etc. effects of

Origanum vulgare L. extract [

10]. However, increasing scientific attention is directed towards

O. onites for its antioxidative, antibacterial, antifungal and insecticidal effects on human healthy [

27]

O. onites showed strong antioxidant activity in different tests of extracts obtained from several solvents [

13].

A total of 134 terpenoids, 6 phenylpropanoids and 26 other components have been identified in the phystochemical studies of essential oil of

O. onites [

13].

The antioxidant activity of

O. vulgare extract evaluated using FRAP, CUPRAC, inhibition of lipid peroxidation catalyzed by cytochrome c and superoxide (SO) scavenging assays [

10]. The obtained results indicated a high antioxidant potential of this extract in vitro, in line with the total polyphenolic content. Possibility of

O. vulgare extract therapy as well as rosmarinic acid and carvacrol (active compounds of Oregano), to restore the antioxidant enzymes activity and to facilitate lipid peroxidation in vivo was detected [

10,

19].

The present study evaluated the effects of O. onites extract and essential oil as well as ethanol and blank liposomes on the oxidative stress markers in the brain and liver cells of mice.

Oxidative stress can cause damage to cell structures and consequently lead to various diseases and ageing [

2]. In case of oxidative stress reactive oxygen species (ROS) is forming. However, the accumulation of ROS is controlled in vivo by a wide spectrum of non-enzymatic antioxidant systems, such as glutathione (GSH) that scavenges free radicals or play as glutathione peroxidase substrate [

19], i.e. it has the main role in coordinating antioxidant defense processes in the body.

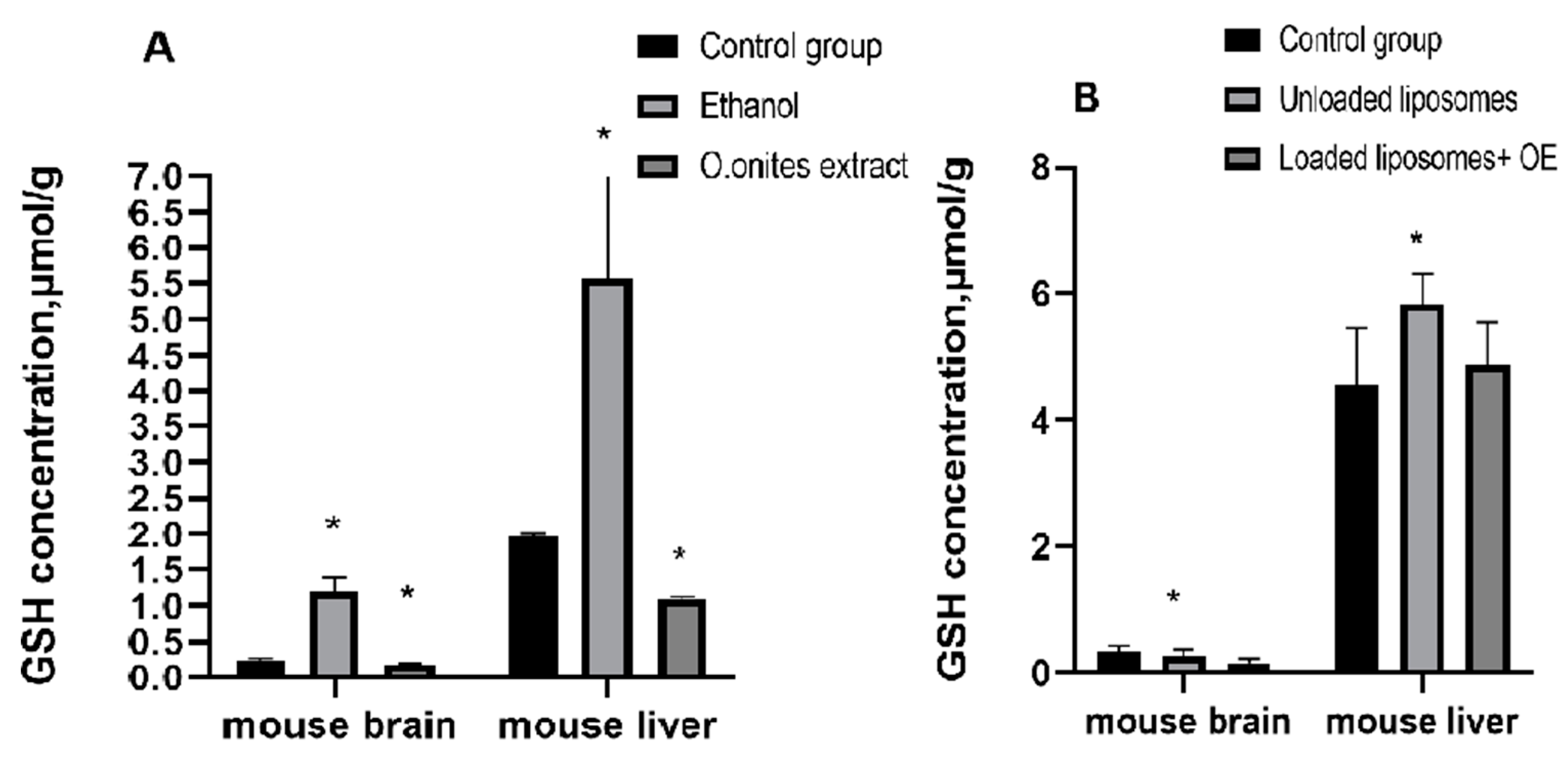

We assessed GSH concentrations in the liver and brain homogenates of experimental animals in the presence and absence of extract or liposomes with essential oil of O. onites L. as well as in the presence and absence of ethanol (control 2) or blank liposomes (control 3). Our results indicated that after 21 days of consumption of these preparations, GSH concentrations in the brain decreased by 24% and 33% accordingly, compared to control values. Whereas GSH amount in the liver of mice decreased by 45% in case of O. onites extract administration but increased by 9% in case of administration of loaded liposomes with OE. Ethanol as well as blank liposomes increased GSH concentration in both brain and liver of mice, compared to control values. Meanwhile liposomes with OE significantly decreased GSH levels in the brain and liver compared with blank liposomes.

The results of

Origanum onites L. extract study agree with previous studies that assessed the effects of rosmarinic acid (main compound of Origanum extract) on GSH levels in mice brain and [

19].

The obtained results of loaded liposome with OE agreed with the same study too, where the effect of the main essential oil component – carvacrol - on GSH level in the brain was evaluated. However, the changes of concentrations of GSH in the liver of mice were different. However, since the diminish of GSH level in liver after administration of liposomes with OE was not statistically significant, it suggests the potential of preparations to act as liver and brain protectants via the antioxidant effect.

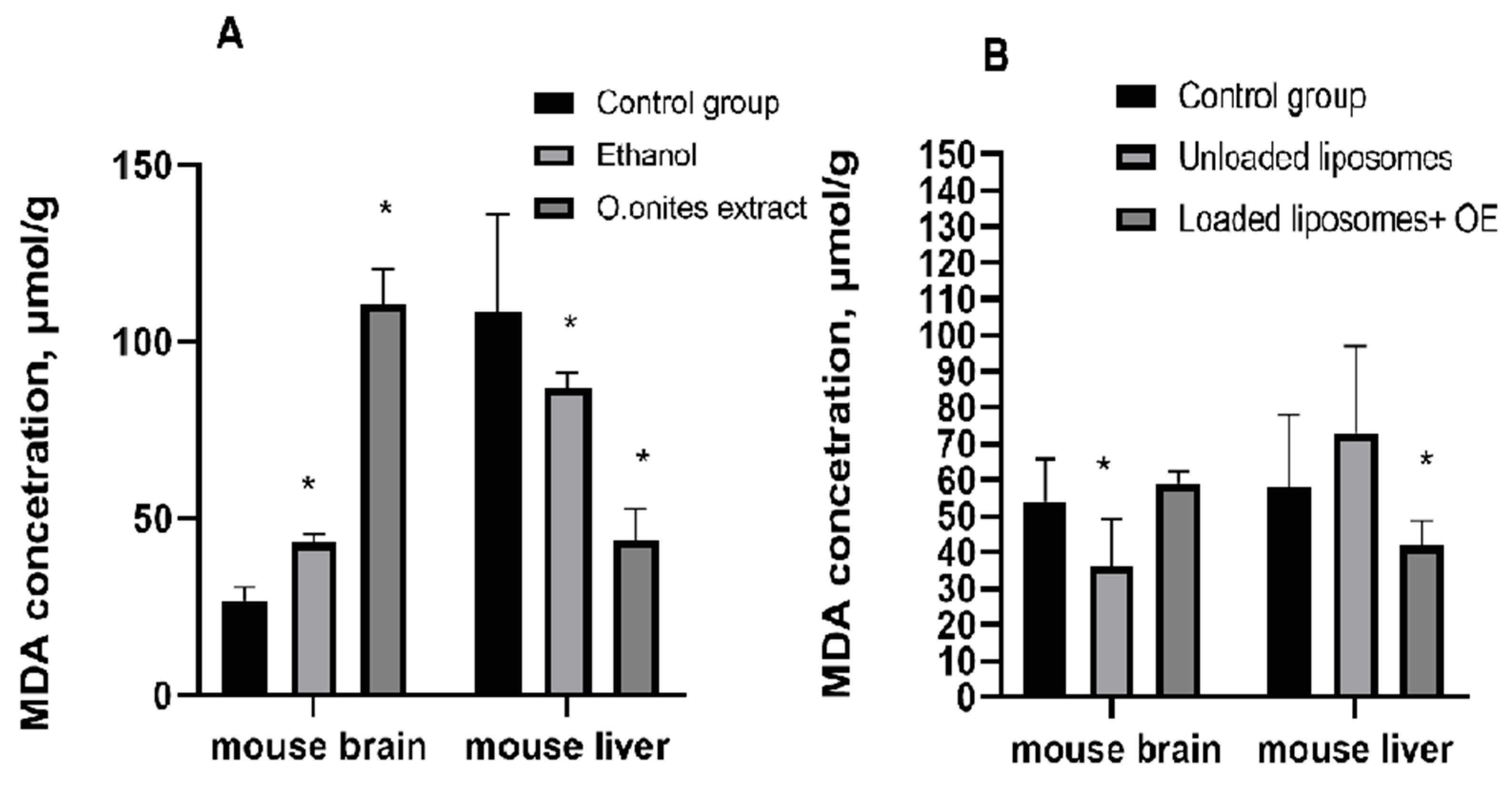

MDA level indicates the extent of oxidative stress as is the end product of lipid peroxidation [

19]. We evaluated the changes of MDA concentrations in the liver and brain of mice in the presence and absence of extract or loaded liposomes with OE as well as in the presence and absence of ethanol or blank liposomes too. Our results indicated that after 21 days of supplementation of

O. onites extract the experimental mice demonstrated significantly changes of the concentration of MDA in the liver and brain, compared with control values. Meanwhile liposomes with OE demonstrated marked changes of MDA only in the liver of mice. However, while MDA concentrations in the brain had a tendency to elevate, they were significantly decrease in the liver after extract or liposomes with essential oil of

O. onites.

Contrary changes in the MDA concentrations were observed after administration of blank liposomes in the liver and brain compared to control values: MDA level in the brain decreased by 33%, while in the liver it increases by 26%. Compared to blank liposomes, loaded liposomes with OE increase MDA level in the brain but decrease it in the liver.

Our results indicated that both, the extract and liposomes with essential oil of

O. onites, reduce MDA concentrations in the liver of mice and it is in agreement with previous study of rosmarinic acid and carvacrol [

19]. The main components of extract and essential oil - showing the ability of studied preparations to reduce oxidative stress. However, results in the brain were controversial. While rosmarinic acid as well as carvacrol decreased MDA concentration in the brain, both Oregano extract and loaded liposomes with OE increased levels of this enzyme.

The differences of changes of MDA and GSH levels in experimental mice brain and liver after administration of extract or liposomes with OE allow us to agree with the statement that pro-oxidant and antioxidant activities could be noticed at different doses of phenolic compounds [

28].

In general, our results obtained that O. onites L. extract as well as loaded liposomes with OE after 21 day of the experiment affected concentrations of GSH and MDA. Oregano extract and liposomes with essential oil significantly changed both MDA and GSH concentrations in mice liver and brain. A non-significant increase of MDA concentration in the brain and GSH in the liver were obtained after administration of loaded liposomes with OE. However, our study results showed that these liposomes significantly reduced the concentrations of tested oxidative stress markers, except MDA level in the brain, where a significant increase was detected, compared to administration of blank liposomes.

Administration of ethanol solution, which is the base of extract, affected MDA level in the liver and brain of mice as O. onites extract did, while the effect on changes in concentration of GSH was opposite.

The obtained results show that different consumption of

O. onites L. has different effect on oxidative stress markers in the body. And although it does not allow us to unequivocally state that the

O. onites extract and loaded liposomes with OE can reduce the level of oxidative stress markers in vivo, however, a mild degree of oxidative stress can increase the levels of antioxidant defenses and xenobiotic-metabolising enzymes, leading to overall cytoprotection. Thus, the pro-oxidative effect can be beneficial in practice [

29].

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant material.

Dried Origanum onites L. herb was purchased from “İnanTarım ECO DAB” Turkey.

4.2. Reagents

Lipoid S75, Lipoid S90 and Lipoid S100 were purchased from Lipoid GmbH, Ludwigshafen, Germany.

Methanol (99%) was supplied from Carl Roth GmbH, Germany.

Potassium chloride, hydrogen peroxide, phosphoric acid were supplied from Merc, Germany.

Ethanol (96%) was purchase from Vilnius degtine, Lithuania.

TBA (thiobarbituric acid), tris-HCl (tris-hydrochloride), DTNB (5,5-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) were supplied from Serva, Germany.

Formic acid was purchased from Fluka Vhemie, Switzerland.

Purified water was produced using a Millipore water purification system (Merck, United States).

Acetonitrile, chloroform (99.8%), acetic acid (99.8%), thymol (99%) and carvacrol (98%) were supplied from Sigma-Aldrich, Switzerland.

Helium (99.999%) was supplied from AGA Lithuania.

4.3. Preparation of extract

The preparation of extract was done based on the article of Baranauskaite et al. in 2017 [

9]. 5 g of dried, powdered plant material was poured into 100 mL of 90% (v/v) ethanol and extracted in a round bottom flask by heat-reflux extraction performed in a water bath for 4 h at 95°C [

9]. The extract has been passed through a 0.22 μm membrane filter. The extract was diluted to 10 % ethanol concentration before the administration to mice.

4.4. Preparation of essential oil

50 g of plant material with 500 mL of water are placed in a round-bottomed flask. The unit is carried to glycerol batch of 120°C temperature for 2 h. The vapour mixture of water–oil produced in the flask passes to the condenser, where it is condensed. After condensation, the oil is separated from water by decantation, measured on an analytical scale and kept in a cool, dark place.

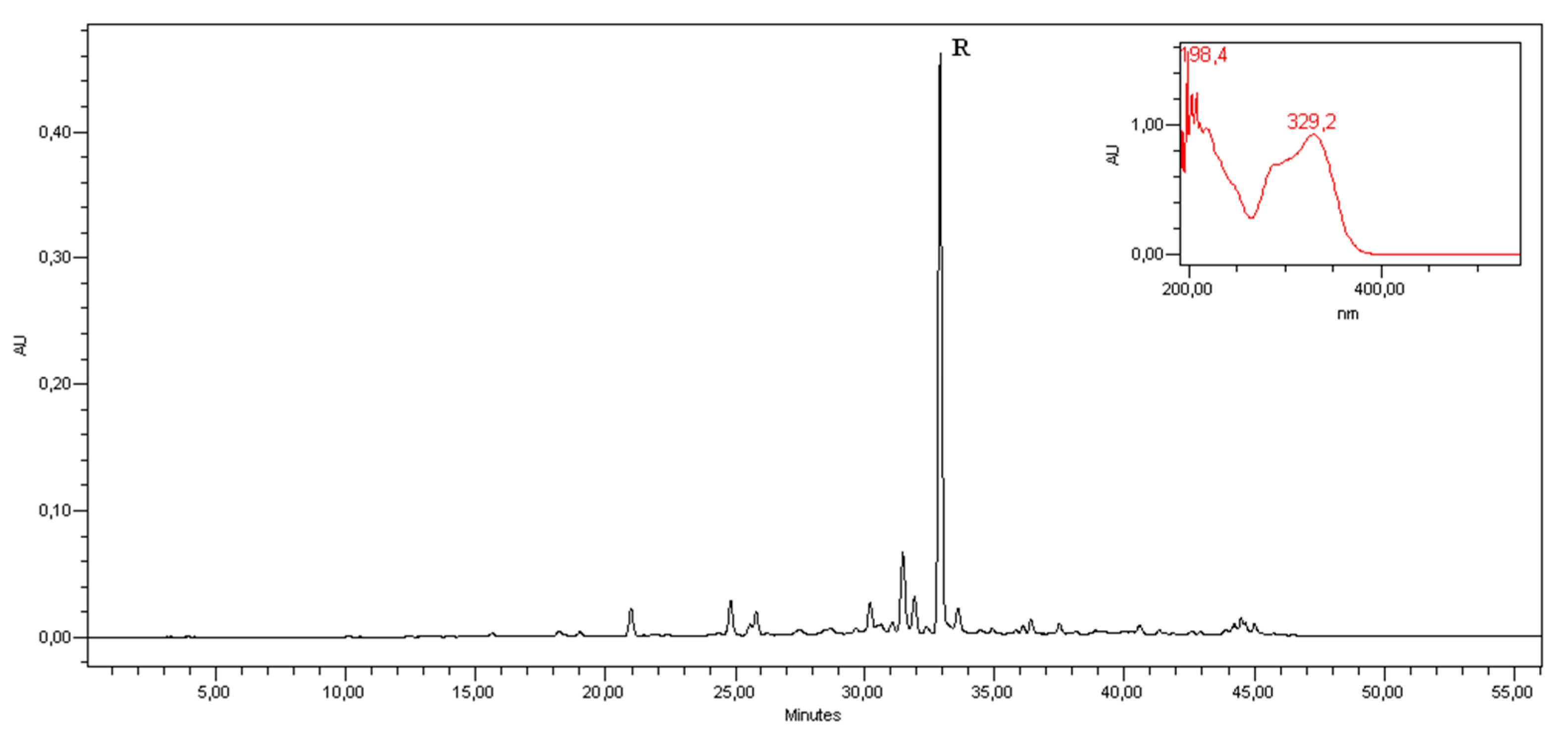

4.5. Analysis of extract

The HPLC methodology used for extract analysis was described in our previous study in 2017 [

9]. Waters 2695 chromatography system (Waters, Milford, USA) equipped with Waters 996 PDA detector and 250x4.6 mm 5-µm ACE C18 column (Advanced Chromatography Technologies, Scotland) for investigation of biologically active compounds in extract of

O. onites L. was used. Different HPLC conditions for determination of the main compounds of extract (rosmarinic acid (RA) and carvacrol (CA)) were used.

Determination of RA: the mobile phase consisted of a mixture of methanol (solvent A) and 0.5% acetic acid (v/v) (solvent B). Gradient elution profile was used as follow: 95% A/ 5% B–0 min, 40% A/60% B–40 min, 10% A/90% B–41–55 min, and 95% A/5% B–56 min. The solvent flow rate was 1 mL/min and injection volume was 10 μL. The identification was carried out at a wavelength of 329 nm.

Determination of CA: the mobile phase consisted of a mixture of methanol and water (60/40, v/v). The solvent flow rate was 0.6 mL/min, injection volume was 10 μL. The absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 275 nm.

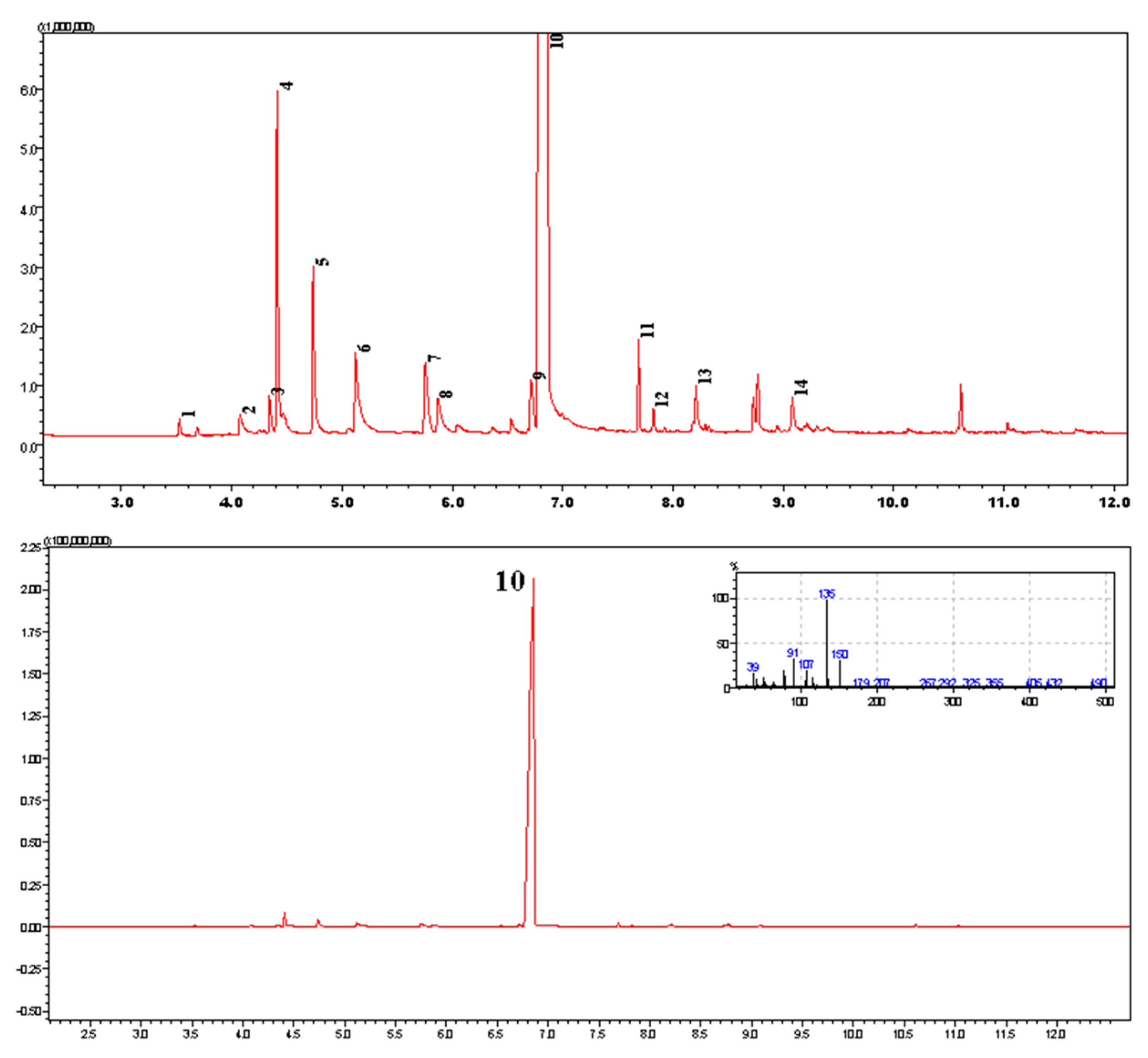

4.6. Gas chromatography analysis of Oregano essentials

Initial column temperature 60°C, injector temperature 290°C, amount of injected sample 1 μl. Helium was used as the carrier gas. The temperature is raised gradually: from 70°C to 250°C, 20°C/min. speed, from 250°C to 300°C is raised at 50°C/min. speed. One test sample is analyzed for 15 min. Chromatograms analyzed Lab Solution GMSS solution Shimadzu program. OE identification of components was performed by the NIST Mass spectral program by analyzing mass spectra.

4.7. Preparation of unloaded liposomes

The liposomes were prepared by Bangham method [

18]. The phosholipid mixture was dissolved using 2:1 (v/v) chloroform/methanol in round-bottomed flasks. The composition of the phospholipid mixture seen in

Table 4. The organic solvents were removed (20 min, 35°C) using a rotary evaporator (Schwabach, Germany) and in the last step solvent residue was removed with N

2 gas.

Table 4.

The composition of liposomes: weight ratio, mass and volume information, and formulation codes.

Table 4.

The composition of liposomes: weight ratio, mass and volume information, and formulation codes.

| Formulation code |

Composition |

Ratio |

| Lipoid S75 |

Lipoid S100 |

| L1 |

300 |

- |

- |

| L2 |

- |

300 |

- |

| L3 |

150 |

150 |

1:1 |

| L4 |

100 |

200 |

1:2 |

| L5 |

75 |

225 |

1:3 |

4.8. Preparation of OE loaded liposomes

To prepare the uniform particles by avoiding clustering into unloaded liposomes OE was incorporated according to Bangham method [

18]. To prepare loaded liposome formulations (LE1, LE2, LE3, LE4, LE5 and LE6) unloaded liposome L2 and L3 composition and desired OE was dissolved into 2:1 (v/v) chloroform/methanol solvent mixture in round-bottomed flasks. The organic solvents were removed (20 min, 35°C) using a rotary evaporator (Schwabach, Germany) and solvent residue was removed with N

2 gas. The thin film was dispersed into purified water and was homogenized (7k rpm, 8 min) using a Wise Tis HG-15D model homogenizer. The composition of loaded liposomes formulations is shown in

Table 5.

Table 5.

The composition of OE loaded liposome formulations.

Table 5.

The composition of OE loaded liposome formulations.

| Formulation code |

Code |

Composition of the formulations (mg) |

Ratio |

| OE |

Lipoid S100 |

Lipoid S75 |

| L2 |

LE1 |

90 |

90 |

- |

1:1 |

| LE2 |

60 |

120 |

- |

1:2 |

| LE3 |

30 |

150 |

- |

1:5 |

| L3 |

LE4 |

90 |

45 |

45 |

1:1 |

| LE5 |

60 |

60 |

60 |

1:2 |

| LE6 |

30 |

75 |

75 |

1:5 |

4.9. Characterization of particle size distribution and zeta potential

Differential light scattering (DLS) (Nano ZS 3600, USA) was used to measure mean particle size (PS) and particle size distribution (PDI). A low (<0.25) PDI value indicates a homogeneous particle size distribution, while a high (>0.5) indicates heterogeneity. Measurements of zeta potential were also obtained by operating the DLS in zeta mode. Electrocuvettes were used to measure the zeta potential.

4.10. Encapsulation efficiency

The encapsulation efficiency (EE) of the liposomes was determined by centrifuging the formulation at 10.000 rpm for 20 minutes (Spectra Por, Germany). The amount of active substance in the collected filtrate was analyzed using GC-MS method, and the amount of drug dissolved in water, if any, was also determined. For this purpose, the formulations were taken into a chambered centrifuge tube containing a membrane with a pore opening of 10 kDa (Merck Millipore, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) and centrifuged at 10000 rpm for 30 minutes, and the amount of active substance in the separated water phase (filtrate) was determined by GC-MS method (GC–QP2010, Japan) method [

15]. The EE was determined by the formula:

where qp is the amount of the active ingredients in liposomes (mg/mL) and qt is the total amount of active ingredients added into liposomes (mg/mL).

4.11. Evaluation of stability

To study storage stability, liposomes were stored (4°C, 1 month) in amber colored glass containers (4 oz.). Parameters were assessed such as particle size, zeta potential, PDI, EE% of CA.

4.12. Animal model

The experiment was carry out on 6-8 weeks-old white female BALB/c laboratory mice weighing 20-25 g. Tests with animals were performed according to the study protocol and was approved by the Lithuanian State Food and Veterinary Service, License no. G2–203.

The extract and liposomes (10 mL/kg body weight) were administrated intragastrically for 21 days. The mice received feed and drinking water ad libidum throughout the experiment and were kept on a 12 hours light-dark cycle. The mice were kept in group cages, containing 8 mice in each:

Control 1 group received NaCl 0.9% (the saline solution) for 21 days.

Control 2 group received 10% ethanol solution.

Control 3 group received blank liposomes (unloaded liposomes).

The 4th group received O. onites L. extract.

The 5th group received liposomes with O. onites L. essential oil (loaded liposomes + OE).

MDA and GSH concentrations were examined in all tested groups and compared with the control 1 group. These parameters were also assessed compared to ethanol group (control 2 group) or to blank liposomes group (control 3 group).

The brain and liver homogenates were prepared according to Baranauskaite et al. described procedure [

19]. The brain and liver of animal were removed, washed and immediately cooled on ice after cervical dislocation. Weighed organs were homogenized with 9 volumes of cold 1.15 % KCl solution (relative to organ weight). This results in a 10 % homogenate, which was further centrifuged at 15.000 × g for 15 min.

4.13. Evaluation of GSH

GSH concentration was estimated by the method described by Sadauskiene et al. [

20]. Weighed mouse liver or brain were homogenized in a 6-fold (relative to tissue weight) volume of 5% trichloroacetic acid solution and further centrifuged at 10,000 ×g for 7 min. GSH concentration was determined after reaction with DTNB (Ellman’s reagent or 5,5′-dithiobis (2-nitrobenzoic acid)). Each sample (3 mL) consisted of 2mL of 0.6 mM DTNB in 0.2M sodium phosphate (pH 8.0), 0.2 mL of supernatant fraction and 0.8mL of 0.2 M phosphate buffer. The formed compound absorbs light with a wavelength of 412 nm. The content of GSH was expressed as μmol/g of wet tissue weight.

4.14. Evaluation of MDA

MDA is one of the markers of lipid peroxidation which forms a complex with thiobarbituric acid (TBA) and can be detected by spectrophotometry. MDA content was evaluated in brain and liver samples and the obtained results were expressed in nmol/g of wet tissue weight [

20]. For sample preparation, 0.5 mL of liver/brain homogenate, 3 mL of 1 % phosphoric acid and 1 mL of 0.6 % TBA solution were mixed in a test tube. This made mixture was incubated in a boiling water bath for 45 min, cooled and mixed with 4 mL of n-butanol. Light absorbance of the supernatant was determined at 535 and 520 nm after separation of the butanol phase by centrifugation [

20].

4.15. Statistical analysis

Data was assessed using unpaired Student t-test and nonparametric Wilcoxon criterion for dependent samples. Statistical significance was taken as a value of p ≤0.05 (SPSS version 20.0, SPSS). Data were expressed as the mean ± SEM (standard error of mean) (n = 8).