1. Introduction

According to the National Institute of Deafness and Other Communication, it is estimated that 90% of the deaf parents have hearing children [

1]. These children are referred to as children of deaf adults (CODA). CODA implies a unique cultural and linguistic identity, a heritage of Deaf Culture infused with the auditory abilities of an individual [

2]. However, there has yet to be a firm agreement on the title and spelling of the abbreviation [

3,

4]. Young hearing children of Deaf adults are referred to as kids of Deaf adults (KODA), Hearing Mother Father Deaf (HMFD) in the United Kingdom [

5].

CODAs have had a tumultuous relationship with the hearing world. Alexander Graham Bell’s mother was deaf. However, he supported the oralist movement and advocated using oral language for the Deaf community [

1]. The deaf community inherently perceives inferior to the hearing world. Johann Conrad Amman [

6] in 1873 wrote that deaf people differed from animals very little due to their inability to communicate orally. CODAs take on the deafness stigma of their parents. Deaf parents might not acquire mainstream principles of parental competencies because of various communication barriers and the absence of incidental learning during childhood [

7,

8,

10]. Family experiences of CODAs often differ from those of hearing families because of role switching. Children become interpreters, protectors, and decision-makers [

4,

11]. In a hearing family, children absorb the traditions and values of their caregivers through experiences and communication [

12]. In a family with CODAs, there is a generational gap between parents and children. “One Generation Thick (OGT)” is a concept of interrupted culture and experiences between deaf parents and hearing children [

13].

1.1. Unique family circumstances create unique challenges for CODAs

In addressing the needs of CODAs, researchers have mainly focused on CODA

s’ bimodal bilingualism and language development. The scientific world was intrigued with the code-blending and code-switching of bimodal bilinguals with a unique ability to use two modalities simultaneously for communication [

14,

15]. Due to having severe language delays and dysfunctional communication, many CODAs are placed in special education classrooms and receive speech therapy services [

16,

17]. Culturally diverse deaf families with low socioeconomic status (SES) often have limited literacy skills, and those parents cannot fully support or participate in the school lives of their hearing children [

18]. Research identifies that secure attachment at home and school and well-balanced parental support positively influence academic engagement [

19]. CODAs share the “deafness” of their parents in every single aspect, except for being hearing. These unusual circumstances could result in their difficulties [

19] with behavior and academic engagement [9

. 12,54], and communication in hearing school environments. The literature reports that children with limited communication skills often exhibit problem behavior due to difficulties expressing their needs and wants [

12,

53]. CODAs represent a marginalized cultural group, and unfortunately, their difficulties in adjusting to a classroom environment and academic engagement have received little attention from the researchers [

53,

54,

55].

1.2. Unique family circumstances create unique challenges for CODAs

Integrating behavior support into the learning environment positively affects student academic engagement. A review of over 250 studies that used single-case designs concluded that antecedent interventions for individuals with various abilities were successful [

31,

32]. However, current literature on PSP has primarily targeted students with emotional and behavioral disorders or autism. Pre-session pairing (PSP) [

21,

22,

23] and group contingency [

24,

26] are evidence-based interventions that have been documented to increase student engagement and decrease problem behavior. Researchers who have used PSP with students of all genders, from diverse environments, with varying abilities and academic levels, concluded that this type of antecedent intervention was highly effective in preventing and remedying problem behavior [

34]. PSP effectively improves behavioral outcomes for students with various demographic backgrounds, including genders, diverse racial and ethnic groups, age groups, and abilities and disabilities [

29,

30]. PSP is a rapport-building procedure that creates a sense of trust between the learner and practitioner [

27]. PSP is an antecedent-based intervention, during which the implementer engages in a preferred activity with a student exhibiting problem behavior immediately preceding a problematic situation [

22]. Pairing the practitioner and the learning environment with a highly preferred activity before the instruction without any demands decreased problem behavior during the instructional session [

21,

22] [

28].

Group contingency (GC), another evidence-based behavior strategy, has been found to improve student classroom behavior. In utilizing GC to improve individual or group behavior [

40], students receive a predetermined preference activity or item contingent on compliance with specific expectations [

25]. Independent GC is characterized as using the same criterion and consequence for the same target behavior for the entire class of students, but each individual student’s performance determines consequences. Meta-analyses of single case designs from 1960 to 2017 and from 1980 to 2010, demonstrated that independent GCs positively affect students’ classroom behavior during academic instruction from kindergarten to the 12th grade, including those from diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds with different abilities [

25,

39].

1.3. Current Study, Purpose, and Research Question

This study was designed to extend the literature on the multicomponent behavioral interventions that included PSP and independent GC by evaluating changes in off-task behavior in the classroom. While the literature has documented PSP and independent GC separately [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40], the effectiveness in combination has not been investigated. Combining these two intervention strategies is expected to enhance behavioral outcomes in a relatively short timeframe, especially for students whose changes in behavior did not reach the desired levels through either intervention alone. Furthermore, more research on CODAs should be conducted because it is difficult to determine whether the findings of studies on other populations can be generalized to CODAs. To effectively address the needs of CODAs in an inclusive classroom, we aimed to explore the use of a multicomponent intervention joining PSP and independent GC to improve classroom behavior among these students.

We evaluated the implementation of the antecedent-based PSP intervention first to decrease off-task behavior, followed by the PSP combined with independent GC when the reduction of off-task behavior was minimal applying PSP alone. To our knowledge, there is yet to be any available information about behavior support for CODAs. Thus, the present study aimed to close the gap in the literature by identifying effective strategies for improving behaviors among hearing students from deaf households in inclusive classrooms. By comparing the baseline behavior to the behavior after the introduction of PSP and then PSP with independent GC to three hearing students from deaf households, this study aimed to explore how implementing PSP with independent GC decreased off-task behavior during instructional activities for CODAs.

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Setting

Participants were recruited from a first-grade classroom at an elementary school in the northeastern part of the United States. The elementary school had approximately 200 students, and the majority were CODAs. The students comprised 45% Hispanic, 25% White, 21% Black, 1% two or more races, 5% Asian or Pacific Islander, and 3% Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander. In addition, 68% of the students qualified for free lunch, 78% have Individualized Educational Plans (IEPs), and 80% have English as a New Language (ENL) services.

The following five criteria were used to determine the eligibility for the current study. First, the participant’s first language was American Sign Language (ASL). Second, the participant used ASL daily to communicate with caregivers. Third, participants were in an inclusive classroom. Fourth, the participant had to engage in disruptive behavior during at least one academic period (e.g., ELA, math, American Sign Language, or morning circle time). Fifth, participants exhibited delays in reading and mathematics measured by the online-based i-Ready assessment required of all students each year in this school district. The assessment consisted of diagnostic and personalized instruction [

56]. The diagnostic part of the assessment was used in the current study. Each participant who met the criteria was female and had an IEP for speech and langauge impairments.

Linda

Linda was 7 years and 6 months old and Hispanic. She lived with several siblings and stepsiblings in a relatively crowded household. As a result, her parents did not meet her academic and emotional needs; there was an educational and emotional neglect case against her parents with the city Administration for Children’s Services. Linda repeated kindergarten due to severe social-emotional and language delays. Although Linda enjoyed dancing, playing with other children, and doing arts and crafts, she exhibited several academic and behavioral issues. Linda often persisted in speaking without being recognized by teachers or peers. She made loud and distracting noises or repeatedly approached the teacher’s desk without permission. She struggled to follow teacher directions and to communicate her needs. Her expressive and receptive vocabulary was limited. She used gestures, homemade signs, and various noises to communicate. The i-Ready assessment showed that Linda was at the emerging kindergarten level in math and reading. As a result, she received Tier 2 reading interventions.

Mary

Mary was 6 years and 8 months old and Hispanic. She was conceived via surrogate in the Dominican Republic, then moved to U.S. to live with her biological father and his husband, both deaf. Mary was often observed helping her classmates to transition, preparing for a lesson, and offering help and advice to peers and teachers. Mary was an active child who liked dancing and playing with her friends and enjoyed talking to her teachers and peers about her family and home life. While she had several strengths, her off-task behavior was a major concern for her teacher. Mary engaged in untimely conversations with peers during instruction and independent work periods. She was often found to start unyielding arguments or debates with peers or teachers during instruction. In the context of academics, Mary was one level below in math and approaching first-grade level competency in reading according to the i-Ready assessment, which resulted in her receiving Tier 1 math interventions.

India

India was 6 years and 5 months old and African American. India always offered to help her classmates and teachers. She was a sociable child and easily made friends. However, she was often observed conversing with her peers during academic instruction and independent work periods while rules were not to talk. She interrupted the teacher and could not stay on-task during instruction. According to the i-Ready assessment, India was at grade one level in math and an emerging kindergarten level in reading. As a result, she received Tier 2 reading interventions.

2.2. Experimental design

The study used a component analysis with a multiple baseline design with an ABC sequence (baseline, PSP, and PST with GC). Before collecting baseline data, a trial-based behavior analysis was conducted to identify the function of each student’s problem behavior. Data were collected at baseline, duing intervention, and at a fading phase.

2.3. Procedures

2.3.1. Functional Behavior Analysis (FBA)

The FBA started with the completion of the Functional Assessment Checklist for the Teachers and Staff (FACTS) [

41]. The FACTS inquired about antecedents, consequences, and instructional periods associated with the target behavior. The FACTS results showed that the off-task behavior was maintained by teacher attention and escape from difficult tasks for all three participants [

42]. Each condition was tested during 2-min trials during small group instruction or individual work time in the classroom. Each trial consisted of a 1-min test segment and a 1-min control segment.

During the attention condition, the teacher was near the student providing noncontingent attention for 1 min (control segment). The teacher provided verbal attention every 5 s by stating, “You are doing very well today. Please focus and continue your work.” During the test segment of the attention condition, the teacher sat at her table with the student and began testing by stating, “I need to do some work“ and then turning away from the student. She provided attention to the student for 15 s immediately after the occurrence of problem behavior, and then terminated the trial.

When testing the escape condition, the teacher did not place any academic demands on the student for the duration of the control segment. During the test segment, the teacher provided an activity that placed high academic engagement demands on the student and was associated with a high rate of problem behavior. The teacher then terminated the trial after removing the task demand contingent on the occurrence of problem behavior. When no problem behavior occurred, the trial was terminated after 2 min. Two to four daily trials for each condition were performed for three days per participant. Testing of each condition lasted approximately 12 to 24 min.

2.3.2. Baseline

Once the baseline phase began, procedures were conducted on consecutive school days. The teacher implemented typical classroom procedures followed by ongoing classroom management strategies (e.g., transition warnings, redirections, and reprimands). The first author observed 15-25 min of teaching during core subjects to establish the baseline behavior. Observation and video recording started at the beginning of the most challenging activity of the day (e.g., reading instruction) and ended when the students transitioned to the next activity.

The dependent variable, off-task behavior was defined as: (a) not having eyes oriented toward a given assignment or the teacher during instruction or directions, (b) off-topic comments or questions, (c) not working on an assigned task (e.g., having a conversation with peers, moving around the classroom, asking to get water or to use the bathroom), (d) not using the materials appropriately (e.g., drawing on the paper, playing with the writing tools, playing with the manipulatives), (e) not interacting with teacher and peers when requested, or (f) inappropriate vocalizations (e.g., saying that they know the answer, complaining, asking for assistance without an effort to work independently, commenting on the weather or talking about the actions of their peers) [

43,

44]. The off-task behavior was measured using a 20-s whole interval recording system in which the interval was scored whenever off-task behavior occurred during the entire 20-s. To calculate the percentage of time engaged in off-task, the sum of the intervals with off-task was divided by the total number of the intervals and multiplied by 100.

2.3.3. Preference assessment

The teacher performed a preference assessment to determine a high-interest activity for all participants. The participants were informed of a list of activities that included arts and crafts, board games or puzzles, and reading or storytelling. They were then directed to select three activities they would like to engage in for 5 min with the teacher and classmates. Upon the completion of the assessment, the researchers created a script for PSP implementation and a fidelity checklist which was modified based on the procedural steps [

45].

2.3.4. Pre-session pairing (PSP) phase

Participants were randomly selected for the PSP intervention. After the order of the participants was detrermined, each participant was asked to choose an activity from the preference assessment. During the intervention for each participant, the teacher engaged in the preferred activity from the list with the participant for 5 min before academic instruction was given to the whole class. Off-task behaviors were recorded right after the teacher announced that the instruction had begun. Data were graphed right after each session to ensure the need for any adjustments.

2.3.5. PSP with Independent Group Contingency (GC) phase

Although the PSP intervention phase decreased off-task behavior for all participants, we added the independent GC to maximize the intervention effects [

46]. For the independent GC, tokens were used as a conditioned reinforcer [

47]. Each participant could earn up to five tokens during each instructional time when they met the teacher’s set class-wide expectations and rules. Some examples of the expections were (i) show respect for teachers, learners, and the learning environment; (ii) show engagement by asking questions, completing assignments; and (iii) participate in class discussions and activities. Examples for rules include (i) be ready to begin learning at the start of class; (ii) raise your hand before speaking; use manipulatives or technology appropriately; and (iii) follow teacher’s directions. The earned tokens could be exchanged for a choice-based activity (e.g., drawing; doing a puzzle; or reading a favorite book) from a classroom treasure box at the end of the day.

2.3.6. IOA and Treatment Integrity

Interobserver agreement (IOA) and treatment integrity were assessed for 33.3%-43% of sessions for each student across phases. The fourth author, a special education doctoral student, was trained in data collection and independently recorded participants’ target behavior to assess IOA. The observers compared interval-by-interval. The number of intervals was divided by the total number of intervals to calculate IOA for off-task behaviors. The calculations resulted in a percentage agreement between the two observers. IOA on treatment integrity (teacher fidelity of intervention implementation) was obtained during 39% of pre-session pairing sessions. The number of steps agreed upon by both observers was divided by the total number of steps and multiplied by 100. IOA for off-task behavior averaged 98% for Linda, 97% for Mary, and 98% for India. IOA for implementation fidelity was 100% for all three participants.

2.3.7. Social Validity

Results of the teacher social validity survey, and student interview indicated that both the teacher and the students had a positive experience. The overall ratings were consistently high (e.g., 4 or 5 on the Likert scale), suggesting that both the teacher and students found the intervention to be useful in promoting a positive classroom environment. The teacher indicated that she benefited from the process. For example, she reported that she successfully created rapport with the participants and the rest of the class, using PSP. She further described the Independent GC as a great motivating tool to use to decrease off-task behavior and to successfully engage the participatants in academic instruction. According to her, PSP and independent GC were cost-efficient methods of providing behavior support for her students and she would continue to use in the future. As such, the student participants expressed their pleasure in selecting preferred activities for the class and found collecting tokens to be fun. Overall, the participants and teacher found the interventions to be highly desirable.

3. Results

3.1. Trial-Based Functional Behavior Analysis

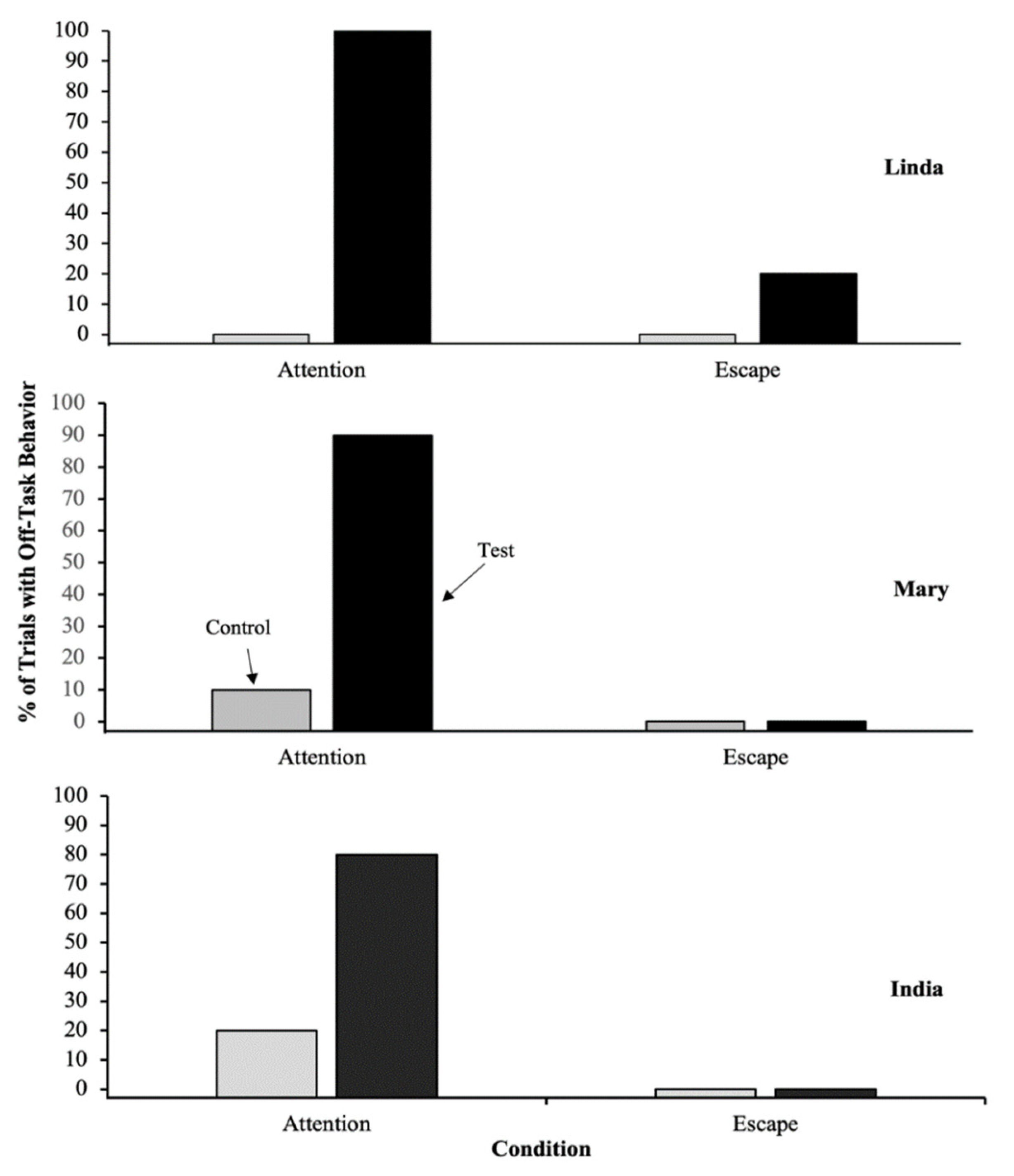

The results indicated that the function of off-task behavior was to gain attention for all three participants. As

Figure 1 shows, the participants’ off-task behavior was maintained by the teacher’s attention. For Linda, off-task behavior occurred in 100% of the testing segments and 0% of the control segments of the attention trials. Off-task behavior occurred in 90% of the testing and 10% of the control segments for Marry and 80% of the testing and 20% of the control segments for India during attention trials.

Escape was found not to serve as a function of any participant’s problem behavior. As the figure presents, Linda’s off-task occurred in 20% of the testing segments and 0% of the control segments of the escape trials. For India and Mary, off-task occurred in 0% of the control and test segments.

3.2. Off-Task Behavior

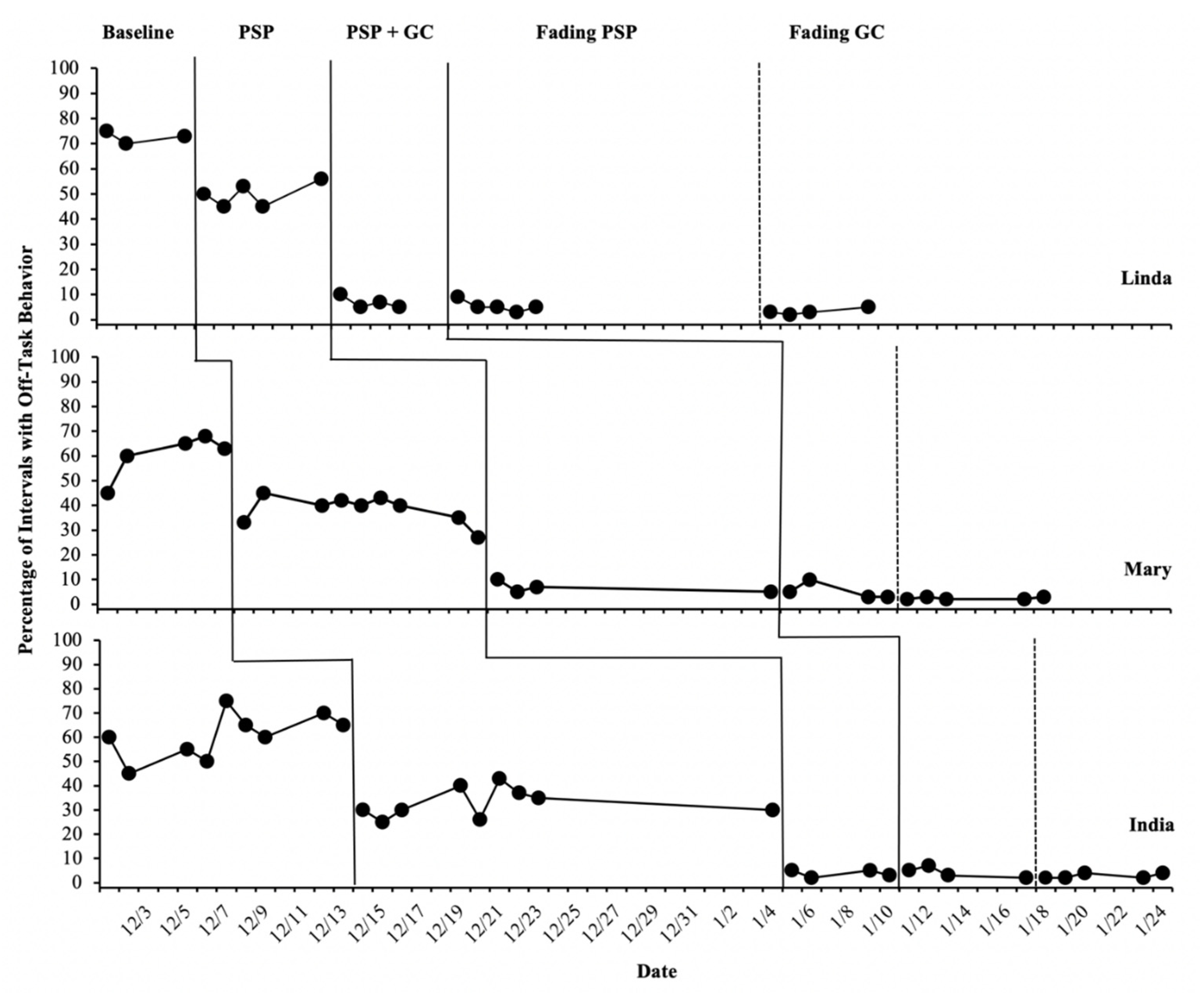

Figure 2 shows that off-task behavior for all participants decreased when PSP was implemented. However, when the independent GC was added to PSP, their off-task behaviors decreased even further, and the reduction was maintained during the fading phase. While Linda’s the baseline mean was 72.6% (range, 70-75%) for off-task behavior, it decreased to 49.8% (range, 45-56%) during the PSP intervention. When the independent GC was added to PSP, her off-task was further reduced to 5.5% (range, 5-7%). Her off-task behavior occurred around 5.5% (range, 3-9%) at the PSP fading and around 3.6% (range, 2-5%) at the independent GC fading phase. Their off-task behavior remained relatively stable.

Mary’s baseline mean for off-task behavior was 60.2% (range, 45-68%). When the PSP was added, the off-task behavior decreased to 38.3% (range, 27-45%) and then to 6.75% (range, 5-10%) when the independent GC was applied. The behavior was maintained at 4.25% (range, 1-10%) during the PSP fading, and 2.75% (range, 2-3%) at the independent GC fading phase. For India, baseline mean for her off-task behavior was 60.5% (range, 45- 75%). During the PSP intervention, it decreased to 32.8% (range, 25-43%), further reducing it to 3.75% (range, 3-5%) during the PSP with independent GC Phase. During PSP fading, the off-task behavior was maintained at around 3.75% (range, 2-5%). During the independent GC fading, it occurred around 2.5% (range, 2 4%).

Overall, the PSP successfully decreased the off-task behavior of all three participants to some degree, but the addition of independent GC markedly decreased the level of off-task behavior. The behavior remained stable and low, as indicated by approximately 5% across all participants during the fading phases. The results demonstrate that PSP with independent GC is an effective strategy to decrease CODAs’ off-task behavior.

4. Discussion

This study was designed to extend the literature on the multi-component intervention to the CODA population by applying PSP and independent GC to three elementary students who exhibited off-task behavior. The focus was examining the relative contributions of PSP and independent GC on decreasing off-task behavior. In particular, off-task was examined under two conditions, PSP and PSP plus GC, in which a new component, GC, would enhance the treatment outcomes. The results revealed that the use of the PSP decreased the off-task behavior of all participating CODAs; however, the PSP alone was not sufficient in decreasing their off-task behavior to the desired levels. When GC was added to PSP, the off-task behavior dramatically decreased, close to zero levels. This result suggests that their off-task behaviors will decrease when an intervention that uses PSP and independent GC is individually tailored and implemented on each CODA during instruction.

This study provides a preliminary exploration of the effectiveness of using PSP with independent GC for the CODA population. It demonstrates that off-task could be better addressed for CODAs when PSP is used in conjunction with GC. These findings support previous research [

29,

30,

31,

32] in that combining an antecedent strategy with reinforcement (GC) effectively addresses problem behavior in CODAs attending an inclusive classroom. The results also suggest that individualized behavior support embedded in whole-class academic instruction could be an inexpensive, time-saving solution for educators of learners from diverse backgrounds and abilities [

22].

CODAs often exhibit deficits in behavioral engagement, an essential component of academic engagement [

9]. Literature suggests that high academic engagement strongly correlates with high academic performance [

9,

49]. Further research should examine the relationship between decreased off-task behavior and academic performance among CODAs. In the current study, the first author was one of two teachers to the participating children. While her co-teacher was teaching, she observed that their academic performance improved when the children’s off-task behavior decreased. The effectiveness of PSP could be linked to the classical conditioning model [

50]. During the implementation of PSP, the first author acted as a conditioned reinforcer paired with a preferred activity. During PSP fading, the children’s off-task behavior remained low, suggesting that the children may have associated the author with a preferred activity. The classical conditioning paradigm is a cornerstone of most incentive-based behavioral interventions [

51]. Hence, the introduction of independent GC, in the form of a token economy, became a natural continuation of the intervention because the focus remained on the individual behavior of the participants, and the intervention occurred during the whole-class instruction. Independent GC intervention was applied to help improve the individual behavior of CODAs by focusing on teaching them the classroom expectations and rules. The results showed a marked improvement in all three participants.

To learn and to adhere to class expectations and rules is an essential skill for CODAs. This population has unique needs due to the non-traditional home environment [

3,

8,

13,

17]. While their home environment demands to sign, CODAs must learn to function in a hearing classroom and to follow group expectations for the first time when they enter the school environment. As a result of this situation, CODAs could exhibit problem behavior and struggle with synchronizing to group expectations and rules. The current research demonstrates that CODAs can learn the necessary classroom rules and expectations when PSP and independent GC are systematically applied in classrooms. The time constraint prevented collecting data to evaluate the long-term maintenance and generalization effects of the intervention. Future research should collect data at these phases to ensure PSP with GC can be maintained and generalized to this population.

In conclusion, more research is needed to understand what strategies effectively address various challenging behaviors CODAs may exhibit in the classroom. The current study shed light on using PSP and Independent GC with the CODA population. These interventions are easy to administer and take little class time without disrupting instruction. Using PSP with independent GC will likely allow educators to reach a marginalized, culturally and linguistically diverse sector of learners, CODAs. Teachers could support and improve the behavioral engagement of this diverse and unique group by introducing PSP in conjunction with independent GC into daily classroom life.

References

- National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/directory/children-deaf-adults-international-inc-coda (accessed on 27.03.2023).

- Bull, T.H. , On the edge of deaf culture: Hearing Children/deaf Parents: Annotated Bibliography. 1998: Deaf Family Research Press.

- Preston, P. Mother father deaf: The heritage of difference. Soc. Sci. Med. 1995, 40, 1461–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, M.; Hicks, S. Orange Eyes: Bimodal Bilingualism in Hearing Adults from Deaf Families. Sign Lang. Stud. 2005, 5, 188–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, D. and G. Kennedy, Lexical comparison of signs from American, Australian, British and New Zealand sign languages. The signs of language revisited: An anthology to honor Ursula Bellugi and Edward Klima, 2000. 20(0): p. 0.

- Bahan, B.; Bauman, H-D. L. Audism: Mapping a postmodern theory of deaf studies. Presentation at the Seventh Deaf Studies conference, Orlando, FL, April 19-21 2001. 19 April.

- Hoffmeister, R.J. Families with deaf parents: A functional perspective. Children of handicapped parents: Research and clinical perspectives, 1985: p. 111-130.

- Singleton, J.L. and M.D. Tittle, Deaf parents and their hearing children. Journal of Deaf studies and Deaf Education, 2000. 5(3): p. 221-236.

- Fredricks, J.A.; Blumenfeld, P.C.; Paris, A.H. School Engagement: Potential of the Concept, State of the Evidence. Rev. Educ. Res. 2004, 74, 59–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieffe, C. Rieffe, C., et al., The role of the environment in children’s emotion socialization. Educating deaf learners: Creating a global evidence base, 2015: p. 369-388.

- Brown, M.C. On the Beat of Truth: A Hearing Daughter's Stories of Her Black Deaf Parents. 2013: Gallaudet University Press.

- Pizer, G.; Walters, K.; Meier, R.P. "We Communicated That Way for a Reason": Language Practices and Language Ideologies Among Hearing Adults Whose Parents Are Deaf. J. Deaf. Stud. Deaf. Educ. 2013, 18, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmeister, R. , Language and the deaf world: Difference not disability. Language, culture, and community in teacher education, 2008: p. 71-98.

- Frederiksen, A.T.; Kroll, J.F. Regulation and Control: What Bimodal Bilingualism Reveals about Learning and Juggling Two Languages. Languages 2022, 7, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Quadros, R.M. Bimodal Bilingual Heritage Signers: A Balancing Act of Languages and Modalities. Sign Lang. Stud. 2018, 18, 355–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.; Bard, B.; Johnson, M.L. Language learning with restricted input: Case studies of two hearing children of deaf parents. Appl. Psycholinguist. 1981, 2, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, K.; Chilla, S. Bimodal bilingual language development of hearing children of deaf parents. Eur. J. Spéc. Needs Educ. 2014, 30, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimentová, E. Dočekal, and K. Hynková, Hearing children of deaf parents–a new social work client group? European Journal of Social Work, 2017. 20(6): p. 846-857.

- Martins, J.; Cunha, J.; Lopes, S.; Moreira, T.; Rosário, P. School Engagement in Elementary School: A Systematic Review of 35 Years of Research. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 34, 793–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Otter, C. and S.-Å. Stenberg, Social capital, human capital and parent–child relation quality: interacting for children’s educational achievement? British Journal of Sociology of Education, 2015. 36(7): p. 996-1016.

- Kruger, A.M.; Strong, W.; Daly, E.J.; O'Connor, M.; Sommerhalder, M.S.; Holtz, J.; Weis, N.; Kane, E.J.; Hoff, N.; Heifner, A. Setting the stage for academic success through antecedent intervention. Psychology in the Schools. Psychol. Sch. 2016, 53, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, A.N.; Axe, J.B.; Allen, R.F.; Maguire, R.W. Effects of Presession Pairing on the Challenging Behavior and Academic Responding of Children with Autism. Behav. Interv. 2015, 30, 135–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rispoli, M.J. , et al., Effects of presession satiation on challenging behavior and academic engagement for children with autism during classroom instruction. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 2011: p. 607-618.

- Ennis, C.R., K. -S. Cho Blair, and H.P. George, An evaluation of group contingency interventions: The role of teacher preference. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 2016. 18(1): p. 17-28.

- Maggin, D.M.; Pustejovsky, J.E.; Johnson, A.H. A Meta-Analysis of School-Based Group Contingency Interventions for Students With Challenging Behavior: An Update. Remedial Spéc. Educ. 2017, 38, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamps, D.; Wills, H.P.; Heitzman-Powell, L.; Laylin, J.; Szoke, C.; Petrillo, T.; Culey, A. Class-Wide Function-Related Intervention Teams: Effects of Group Contingency Programs in Urban Classrooms. J. Posit. Behav. Interv. 2011, 13, 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shillingsburg, M.A.; Bowen, C.N.; Shapiro, S.K. Increasing social approach and decreasing social avoidance in children with autism spectrum disorder during discrete trial training. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2014, 8, 1443–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, C.; Tanaka-Matsumi, J. Positive Behavior Support for a Child With Inattentive Behavior in a Japanese Regular Classroom. J. Posit. Behav. Interv. 2011, 13, 250–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briesch, A.M.; Chafouleas, S.M.; Nissen, K.; Long, S. A Review of State-Level Procedural Guidance for Implementing Multitiered Systems of Support for Behavior (MTSS-B). J. Posit. Behav. Interv. 2020, 22, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hintze, J.M., R. J. Volpe, and E.S. Shapiro, Best practices in the systematic direct observation of student behavior. Best practices in school psychology, 2002. 4: p. 993-1006.

- Malik, T. Classroom Behaviour Management: Increase Student Engagement and Promoting Positive Behaviour. Learn. Teach. 2020, 9, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledford, J.R. , et al., Antecedent social skills interventions for individuals with ASD: What works, for whom, and under what conditions? Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 2018. 33(1): p. 3-13.

- Conroy, M.A. and J.P. Stichter, The application of antecedents in the functional assessment process: Existing research, issues, and recommendations. The Journal of Special Education, 2003. 37(1): p. 15-25.

- Eckert, T.L.; Ardoin, S.P.; Daly, E.J.; Martens, B.K. Improving oral reading fluency: A brief experimental analysis of combining an antecedent intervention with consequences. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 2002, 35, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, L., C. M. Choutka, and N.G. Sokol, Assessment-based antecedent interventions used in natural settings to reduce challenging behavior: An analysis of the literature. Education and Treatment of Children, 2002: p. 113-130.

- Kelly, A.N.; Axe, J.B.; Allen, R.F.; Maguire, R.W. Effects of Presession Pairing on the Challenging Behavior and Academic Responding of Children with Autism. Behav. Interv. 2015, 30, 135–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.J. , Choice as an Antecedent Intervention Provided to Children with Emotional Disturbances. 2019.

- Lugo, A.M.; McArdle, P.E.; King, M.L.; Lamphere, J.C.; Peck, J.A.; Beck, H.J. Effects of Presession Pairing on Preference for Therapeutic Conditions and Challenging Behavior. Behav. Anal. Pr. 2019, 12, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, S.G., A. Akin-Little, and K. O’Neill, Group contingency interventions with children—1980-2010: A meta-analysis. Behavior Modification, 2015. 39(2): p. 322-341.

- Jaquett, C.M.; Skinner, C.H.; Moore, T.; Ryan, K.; McCurdy, M.; Cihak, D. Interdependent Group Rewards: Rewarding On-Task Behavior Versus Academic Performance in an Eighth-Grade Classroom Serving Students With Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. Behav. Disord. 2021, 46, 238–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, R.E. , et al., Functional assessment checklist for teachers and staff (FACTS). Eugene, OR: Educational and Community Supports, 2000.

- Bloom, S.E.; Iwata, B.A.; Fritz, J.N.; Roscoe, E.M.; Carreau, A.B. Classroom application of a trial-based functional analysis. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 2011, 44, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, K.R. , et al., Self-monitoring of attention versus self-monitoring of academic performance: Effects among students with ADHD in the general education classroom. The Journal of Special Education, 2005. 39(3): p. 145-157.

- Wills, H.; Wehby, J.; Caldarella, P.; Kamps, D.; Romine, R.S. Classroom Management That Works: A Replication Trial of the CW-FIT Program. Except. Child. 2018, 84, 437–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, S.E.; Lambert, J.M.; Dayton, E.; Samaha, A.L. Teacher-conducted trial-based functional analyses as the basis for intervention. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 2013, 46, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kehle, T.J.; Bray, M.A.; Theodore, L.A.; Jenson, W.R.; Clark, E. A Multi-Component intervention designed to reduce disruptive classroom behavior. Psychol. Sch. 2000, 37, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Fienup, D.M.; Oh, A.E.; Wang, Y. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Token Economy Practices in K-5 Educational Settings, 2000 to 2019. Behav. Modif. 2022, 46, 1460–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, V.; Sullivan, W.E.; Baxter, E.L.; DeRosa, N.M.; Roane, H.S. Renewal during functional communication training. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 2018, 51, 603–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunuc, S. , The relationships between student engagement and their academic achievement. International Journal on New Trends in Education and their implications, 2014. 5(4): p. 216-231.

- Skinner, B.F. , Operant conditioning. The Encyclopedia of Education, 1971. 7: p. 29-33.

- McSweeney, F.K. and E.S. Murphy, The Wiley Blackwell handbook of operant and classical conditioning. 2014: John Wiley & Sons.

- Pennington, B.; Simacek, J.; McComas, J.; McMaster, K.; Elmquist, M. Maintenance and Generalization in Functional Behavior Assessment/Behavior Intervention Plan Literature. J. Behav. Educ. 2019, 28, 27–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, E.G.; Durand, V.M. Reducing behavior problems through functional communication training. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 1985, 18, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stredler-Brown, A. , & Johnson, R. (2017). Behavioral concerns of children of deaf adults: A literature review. American Annals of the Deaf, 162(3), 238-250.

- Blenner, S. R.; O'Connor, K. Assessing child behavior problems in families with deaf parents. Journal of Child and Family Studies 2021, 26(9), 2356–2367. [Google Scholar]

- https://ireadycentral.com.

- Kazdin, A. E. (2021). Single-case experimental designs: Characteristics, changes, and challenges. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 115(1), 56-85.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).