1. Introduction

The most conventional formulation of quantum mechanics [

1] holds that a physical system is characterized by a wavefunction (Hilbert-space vector) which,

between measurements, evolves smoothly and unitarily in time according to Schroedinger’s equation, but which evolves discontinuously and non-unitarily at the moment of measurement. The quantity being measured is characterized by a Hermitian operator, and at the moment of measurement, the wavefunction is projected (collapses) onto a random eigenvector of this operator, with probability given by the absolute-value-squared of the inner product between the eigenvector in question and the state just prior to measurement, i.e. the Born rule.

This seems to say, counterintuitively, that Nature is thoroughly oblivious to even the finest details of experiments that, today, can be designed down to the atomic level. And yet, this picture, as far as it’s been tested, has genuine empirical support, from interference experiments to qubit readout [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. There have been many creative attempts to make this situation more intuitively palatable, from reconceiving the moment of measurement as a splitting of the world into multiple copies [

8], to introducing explicitly random sub-layers of novel physical process [

9,

10]. But, in one way or another, all these attempts have in common an axiomatic treatment of discontinuous measurement, random state selection and Born-rule probability, so it’s not clear what’s really gained conceptually.

The cleanest outcome would be to eliminate the apparent reliance on explicit measurement axioms altogether, either by refuting them experimentally or deriving them in some form from unitary dynamics. The challenge of doing so is known as the quantum measurement problem. Recent developments underscore the problem. History [

11,

12] calls into question the original logic behind the conventional measurement axioms. The concept of quantum non-demolition measurement [

13] – important for engineering quantum systems – creates a distinction between projective and non-projective measurements that wasn’t foreseen by the framers and confounds the conventional axiomatic formulation. Proton-decay experiments [

14] search for events with probability many orders of magnitude smaller than in any test of the Born rule to date. And quantum computers [

15] perform measurements in quantities so voluminous that even small departures from the Born rule could conceivably leave subtle statistical signatures that could bias elaborate calculations.

If there are no universal measurement axioms, then the outcomes of quantum experiments must be understood case-by-case, although there can be recurring themes. In Reference [

16], I proposed a physical mechanism to account for a Born rule for the starting locations of alpha particle tracks from radioactive decay in a cloud chamber (Mott problem), without invoking measurement axioms. In References [

17,

18], I supported my findings with publicly available, if circumstantial, video data. The Born rule followed from the existence of sites – almost-critical condensed clusters of supercooled vapor molecules – at which the cross section for ionization by a passing charged particle is singular at ionization threshold. The randomness of the detection location (i.e. the origin of the cloud chamber track) was not intrinsic to quantum mechanics, but reflected the statistical mechanics of vapor condensation. The singularity arose from a Penning-like process involving molecular polarization in the cluster. In what follows, for reasons that will become clear, I refer to this threshold singularity enabled by induced collective polarization as “leveraged ionization.”

The cloud chamber is of great pedagogical and heuristic significance because one doesn’t have to imagine condensed vapor clusters: when they’re big enough, one can see them with the naked eye in the aggregate as vapor trails, and under low-power magnification as individuated little spherical droplets. But we are left wondering how to explain the probabilistic nature of other techniques for detecting radioactive decay products – and beyond that, more general types of quantum measurement – that don’t involve condensation of supercooled vapor. In the present paper I consider a particularly simple non-condensing detector, the Geiger counter [

19]. I propose a very simple experiment to investigate whether the same ionization physics that takes place in cloud chamber sub-critical vapor clusters also occurs at defects in the thin mica window of a Geiger counter. I do not have a microscopic theory of such defects, but I report on a proof of concept for the experiment, and present results that are consistent with the leveraged-ionization picture. If confirmed more rigorously, it may not be a stretch to imagine that similar physics could take place in other solid-state media, for example the detector in a Stern-Gerlach experiment or the analog-to-digital converters in superconducting-qubit measurement systems.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews the cloud chamber picture.

Section 3 introduces the novel Geiger-counter experiment and details the proof-of-concept test that I performed.

Section 4 applies the concept of leveraged ionization to the Stern-Gerlach experiment, and

Section 5 does the same thing for superconducting qubits.

Section 6 summarizes our work, including a roadmap for future investigation.

2. Cloud chamber

This section includes paraphrased content from Reference [

18].

A diffusion cloud chamber is an enclosure containing air commonly supersaturated with an ethyl alcohol vapor. A passing charged particle ionizes air molecules, and the ions nucleate visible vapor droplets (drive vapor molecule clusters supercritical). This picture is easy to understand when the charged particle wavefunction is strongly collimated (so the particle can be treated as a point at one location moving in one direction). But the actual wavefunction of an alpha particle near the source of an s-wave radioactive decay is spherically symmetric and not collimated in any meaningful sense.

To initiate the well-defined track seen in experiments, the diffuse alpha wavefunction interacts with a vapor cluster (generated randomly by thermal fluctuations) that is just barely sub-critical. A barely sub-critical cluster turns out to have a very large cross section for ionization by the alpha, so that even a very weak alpha wavefunction can provoke the subcritical droplet to grow quickly in a supercritical fashion and become visible, and also provoke the alpha wavefunction to collimate into a narrow beam originating at the point of ionization. This is so because, in a vapor cluster, single-molecule ionization can proceed with very small energy loss: the ion can induce (negative) potential energy due to cluster polarization that can nearly balance the (positive) energy needed for the alpha to excite the ejected electron (a form of Penning ionization [

20]). I.e., ionization is levered by induced collective polarization. This near-degeneracy drives the cross section of this quantum Coulomb interaction to singularity. The singularity takes the specific form

for

R close to

Rc, where

R is cluster radius and

Rc is a critical value. The condition for a track to successfully form at a specific cluster is

where

s is alpha particle speed (momentum divided by mass),

τ is cluster lifetime and

ψ is alpha wavefunction. [We can separate

τ and |

ψ|

2 in this way because for a slow decay, the charged decay product is in a Gamow state [

21] and |

ψ|

2 in the detector varies slowly with time.] If

ρdR is the number of clusters per unit volume and unit time with radius between

R and

R+

dR, then the probability of track initiation per unit volume and time is

For a point radiation source, this depends as distance

r from the source as

for some position-independent coefficient

C.

Bear in mind that clusters are not in fact continuous media, but are made of discrete molecular units, so there can actually be a minimum attainable value of

Rc-

R. That can make Equations (2.3) and (2.4) break down for small enough

ψ. This possibility is discussed in greater detail in [

17].

It’s easy to extend the argumentation in [

16] to the case of a moving charged particle wave packet (group velocity =

s, not just momentum/mass =

s) that crosses the ionization site in time less than

τ. Then the combination

sτ|

ψ|

2 in Equations (2.2) and (2.3) would be replaced by

where the integration path is along the particle’s group velocity. Moreover, Equation (2.3) would then refer to a probability per unit volume but not per unit time, and

ρdR would need to refer to the number of clusters with radius between

R and

R+

dR, per unit volume, but not per unit time. This will be relevant in

Section 4 and

Section 5.

3. Geiger counter

The heart of a Geiger counter is a metallic (Geiger-Muller – GM) tube containing a noble gas (plus inert buffer), with an electrified wire running down the center, sealed by a thin mica window at one end (the entrance) and metal at the other. A charged particle passing through the tube, entering through the window, ionizes a trail of gas atoms, and the resulting ions and electrons trigger an avalanche whose arrival at the wire produces an observable voltage pulse. There are no thermal-fluctuation-driven clusters in the far-from-supersaturated gas. So if the charged particle to be detected arrives at the window as a spherically symmetric wavefunction emitted by radioactive decay, there is nothing in the gas inside (or air outside) the tube to trigger wavefunction collimation and initiate a track. But alpha emitters since time immemorial have been placed close to Geiger counter windows, producing many detection counts, so wavefunction collimation must happen somewhere. If it’s not air or tube gas, the next places to look are inside the source, or inside the solid window itself at hypothetical sites (presumed transient crystal defects) where, as in cloud chambers, ions can induce just the right amount of (negative) potential energy – by polarizing the surrounding medium – to cancel the (positive) energy of ionization. (Rc in this case becomes a critical defect size, and I ignore any complication in the distribution of defect shapes that undercuts using R and Rc as meaningful parameters.)

I do not have a microscopic theory of such defects. Instead, I propose probing them indirectly through an experiment in which a point-like alpha source is placed near a Geiger counter window, and count rate is measured as a function of source-window separation. One can easily derive (see below) the form that this function should take if the underlying process is governed by Equation (2.4) in the window. If this derived form fits poorly, that rules out the leveraged ionization picture.

In May 2022, I conducted a test of this experimental concept (

Figure 1). I mounted a needle source [

22] of the alpha emitter

210Po on a manual analog linear stage calibrated in fractions of an inch. I dialed the stage until the “hot” end of the needle just touched the center of the 16-mm-diameter mica window of a commercial Geiger-Muller tube [

23] (I first exposed the window by removing a protective wire mesh). I then dialed the stage back by multiples of 1/40 in = 0.64 mm, and, at each multiple, I watched the analog dial of an activity meter [

24] and recorded the lowest value of counts per minute (CPM) attained during a 30 sec interval (this minimum is much easier to judge by eye than the mean value). The background was 50 CPM (compare with 40 CPM per the detector spec sheet [

23]). For each stage setting, I subtracted this background from the recorded counts per minute with the source in place, and then corrected the resulting values (

N) by adding a simple scaled square root to back out what the

average count rates should be. I used the specific scaled square root (15

N)

1/2 because the meter integrated for 4 sec and there are fifteen such integration periods in a minute. This is how I arrived at the values on the horizontal axes in Figures 3 and 4 below.

To analyze the results, I compare the measurements with two models. One model is naively geometric; it assumes spherical wavefunctions convert to collimated wavefunctions in the source medium, so that detector CPM is the total source activity into 4π steradians multiplied by the fraction of solid angle subtended by the mica window, but cut off as dictated by alpha stopping power in air and mica. The other model assumes track collimation takes place inside the window according to the Born rule Equation (2.4), again cut off as dictated by alpha stopping power in air and mica.

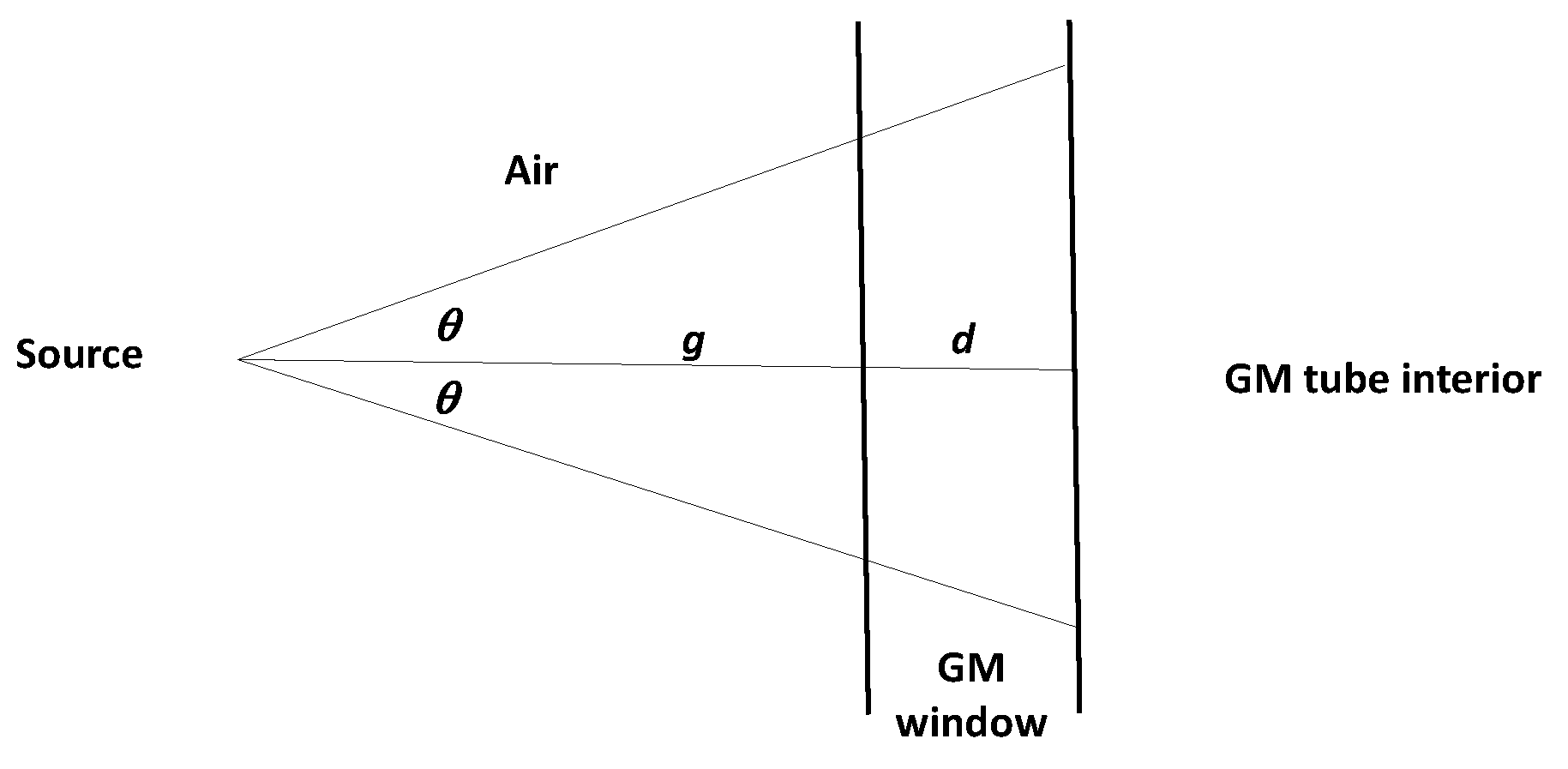

The stopping correction for an ideal point source is diagrammed in

Figure 2. (In actuality, the needle source is about 4 mm long [

17], I correct for that in Figure 4) The parameter

d is the thickness of the window

scaled to the distance in air that gives equivalent alpha stopping (the actual thickness is small enough to be irrelevant for now). As a practical matter, I do not actually know the precise value of

d a priori and have to fit it to the data, as appropriate (see below). The parameter

θ is the smaller of the angle of a ray that just intersects the window’s edge, and the angle of a ray whose total length in the diagram is equivalent to the alpha-particle extinction length

L in air (roughly 4 cm for

210Po alphas [

25]). In either case, real or virtual alphas corresponding to rays with angles greater than

θ cannot produce ion trails in the GM tube. In formulas, we have

where

D is window diameter. The count rate in the geometric model is then the total source activity

F multiplied by the fraction of solid angle subtended by a cone of angle

θ, i.e.

For the radioactive source that I used, F=(0.01±20%) μCurie = 22,200±20% CPM.

The count rate in the model based on the cloud-chamber Born rule is derived from the integral of Equation (2.4) over the interior of the window, cut off by angle

θ. The integral, using polar coordinates in the plane of the window, is

where

z is non-scaled distance into the window, and

Z is non-scaled total window thickness.

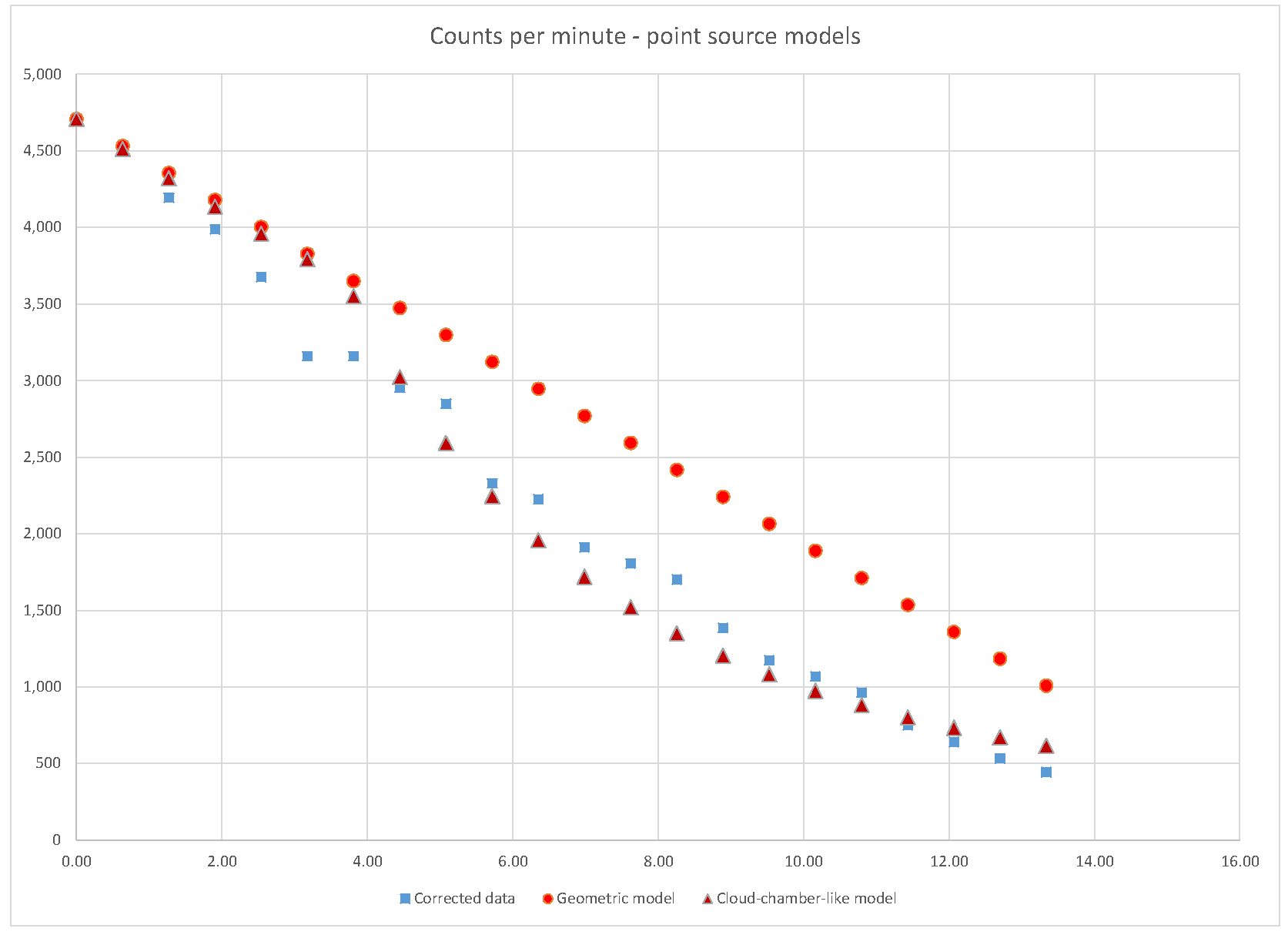

The model comparisons for a point source idealization are shown in

Figure 3.

The parameter

d in the geometric model is fixed by total source activity and normalizing to the experimental count rate 4708 CPM at zero separation,

This model comes as close as it can to the rest of the data points when F is as large as possible, i.e. 1.2 μCurie, whence d=23mm. In the alternative cloud-chamber-inspired model, the parameter d is set by hand and the coefficient C’ is then fixed by d and the experimental count rate at zero separation. The best fit achievable in this case has d=14mm. The cloud-chamber-inspired model seems to provide a much better fit to the data than the geometric model.

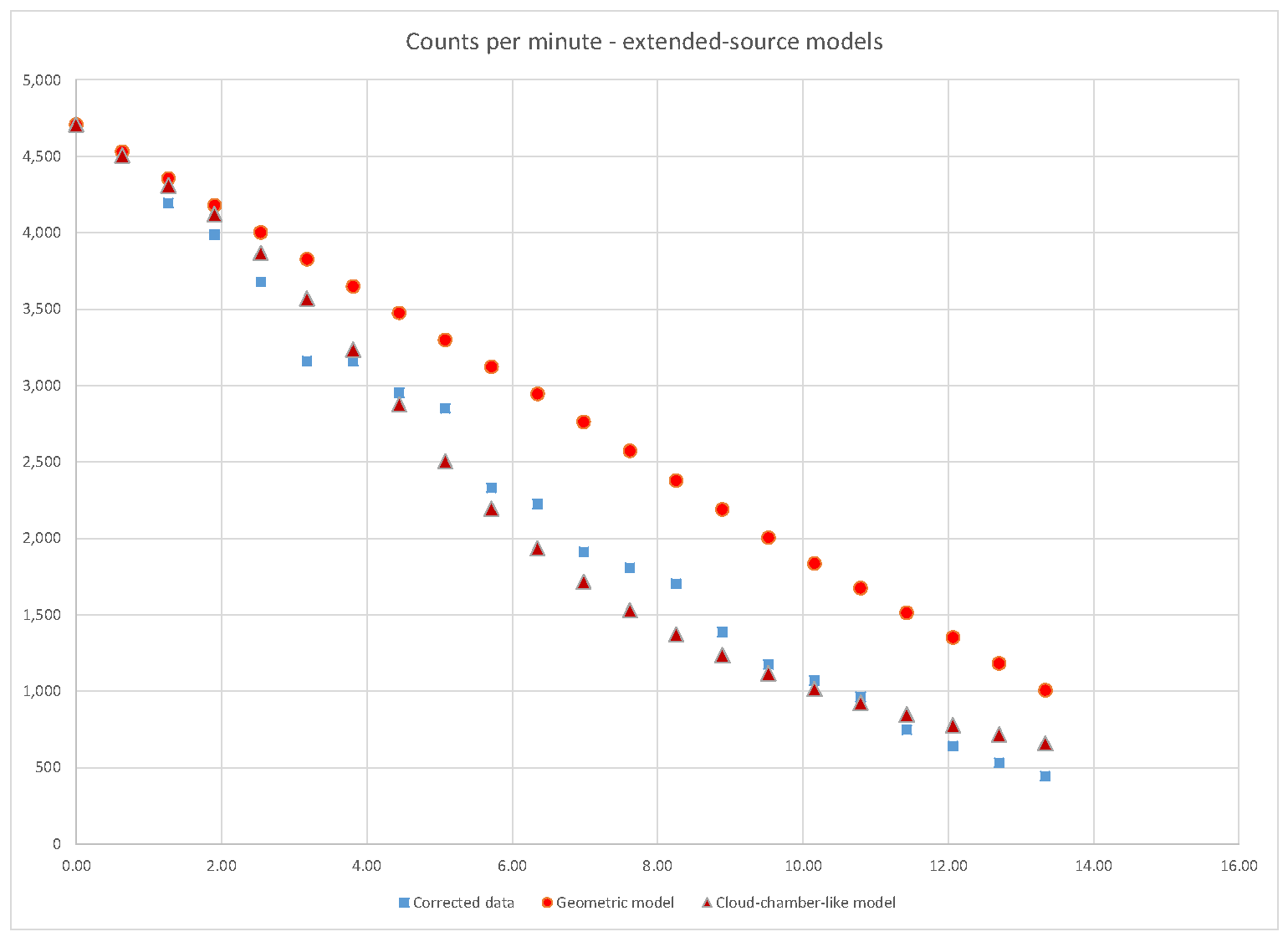

The comparisons for extended-source versions of the models are shown in

Figure 4. To get each model point in

Figure 4, I averaged each point-source model value over five successive values of source-window separation, and then adjusted parameters for best fit. Best fit for the geometric model again has total activity of 1.2 μCurie, but this time with

d=22mm. Best fit for the model based on Equation (2.4) has

d=16mm. Again the cloud chamber model seems to provide a much better fit to the data than the geometric model, and the extended-source model seems to provide a better fit than the point source model.

The derived value of

d is an independent check on these results. According to Fig. 3 in [

26], for an alpha particle from

210Po decay (5.4 MeV, 1.6x10

9 cm/s), 1 cm of air has the same stopping power as 1.44 mg/cm

2 of mica. In this experiment’s Geiger counter [

23], the window is rated at 2.0±0.3 mg/cm

2. That means

d=(2.0±0.3)/1.44 cm = 14±2 mm, in line with the cloud-chamber-model results.

A more detailed model might take into account the GM tube’s metallic wall or central wire, but nothing in these results appears to cry out for such effects. This is perhaps to be expected, since wall and wire are much farther than window from the source.

These results seem at odds with student-level demonstrations of an inverse-square law for detections from a radioactive source [

27], because the inverse square law is essentially the geometrical model disfavored above. I can only conclude that the source media used in such demonstrations are thick enough to contain plenty of their own sites for spherical-to-collimated wavefunction conversion. By contrast, the radioactive film at the tip of the needle source must not be thick enough, leaving the Geiger-counter window to pick up the slack.

4. Stern-Gerlach experiment

If leveraged ionization operates in a Geiger counter window, then maybe it operates in other quantum experiments with charged particles and solid-state instrumentation. In this section, we consider the particular case of the Stern-Gerlach experiment, and in the next section we consider superconducting qubits.

In the original Stern-Gerlach experiment [

28,

29], a collimated beam of spin-1/2 neutral silver atoms passed through a region with a spatially varying magnetic field. The beam was then detected as two distinct smears deposited on a glass plate. Later experiments (e.g., Rabi oscillations in Fig. 2A of [

30]) refined the experiment to use electronic detectors and verify the Born rule.

If leveraged ionization applies, then the probability per unit area of a charged particle (say, electron in CCD; see third paragraph in

Section 6) liberated by a spin-1/2 beam particle hitting the detector of a Stern-Gerlach apparatus at a particular coordinate “

x” perpendicular to the beam direction is

if the ionization process is insensitive to spin, so that we can write|

ψ|

2 as the sum of the absolute-squared spatial wavefunctions for the two incoming spin components. (We have also assumed that the singular cross-section as parametrized in Equation (2.1) is large enough to encompass the combined transverse spreads of both up and down components of

ψ.) If the incoming beam particle is prepared as

a|spin up>+

b|spin down>, where |spin up> and |spin down> are equivalently normalized, then, trivially, we can write the probability in Equation (4.1) as

for some equivalently normalized functions

Φ. If the

Φup and

Φ down spots don’t overlap, then the probabilities of landing in the up and down spots are

where the last equality comes from equivalence of normalization. This is the Born rule for spin.

5. Superconducting qubit

A superconducting qubit is an artificial atom made from Josephson junctions coupled to an RF resonating cavity [

31]. It is typically configured so that the lowest two excited states |

g> and |

e> are close in energy and can be treated together as a self-contained two-level system. The state of this two-level system is typically measured (“read out”) by sending a microwave pure-tone at the cavity via a transmission line, and recording the reflected signal. If the frequency of the pure tone is chosen appropriately, the signal reflected from an only-|

g> qubit has a phase shift that is detectably different from the phase shift due to reflection from an only-|

e> qubit. The reflected signal goes through several stages of amplification and then passes through an A/D converter, after which it is recorded as a digitized voltage time series. The phase shift is extracted from the time series via traditional I/Q processing, and the measured state is inferred directly from the result. As a practical matter, phase shifts not corresponding to only-|

g> or only-|

e> are not observed, since the outcome appears to accord with the canonical measurement axioms: measurement seems to collapse a linear combination

a|

g>+

b|

e> randomly to one or another of the two constituent energy levels, with Born-rule probabilities.

This complicated setup involves many parts acting over a nontrivial time period [

32]: Josephson junctions, a resonator, the machinery of initial state preparation (strings of Rabi pulses), a transmission line, several levels of amplification, A/D conversion, digitized signal recording, and computational processing. If the canonical measurement outcome reflects some underlying physical process founded on Schroedinger’s equation, there is a surfeit of places where the canonical output might actually happen. In this section I pursue the simplest option: all that matters to the canonical nature of the outcome are the initial qubit state and the final digitization of the reflected and amplified voltage signal, because the A/D converter is the first place along the signal chain where I can imagine that discrimination between only-|

g> and only-|

e> can take place.

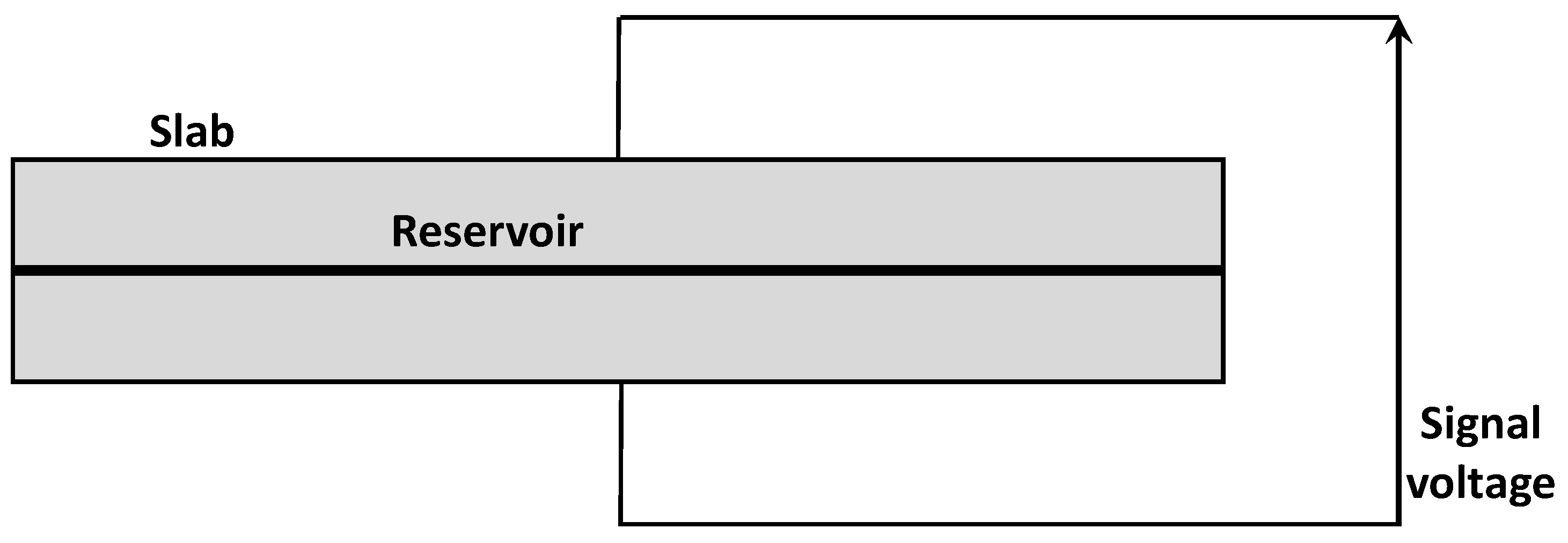

In one of the simplest designs [

33], A/D conversion starts by passing a signal through a multi-level voltage divider to generate multiple scaled copies; then it runs the copies through comparators (basically diodes) that output saturated digital 0 or 1 pulses depending on whether the voltages are larger or smaller than some built-in reference values. To get at the essential physics, I (over)simplify the divider network and comparator bank to be a single slab (

Figure 5). In this idealization, the signal is manifested as a voltage difference between the slab’s top and bottom faces; and a reservoir of mobile electrons occupies a thin planar sheet midway between top and bottom. I imagine that electron transport in the slab is observed at a time when only-|

g> and only-|

e> voltages are expected to have known and opposite signs. This is conceivable – at least for large enough phase shifts – because the entirety of the only-|

g> and only-|

e> signals are in principle known and predictable from the timing of the tone generator, together with the configuration of the qubit/resonator system, the amplifier delays, and the signal path.

When a single electron is in the reservoir, it’s entangled with the prepared qubit state

a|

g>+

b|

e>; below the reservoir, it’s entangled only with

a|

g>; above, it’s entangled only with

b|

e>. This is virtually identical to the Stern-Gerlach case, with |

g> and |

e> taking the roles of |spin down> and |spin up>. So, if leveraged ionization can take place in the slab, then the Born rule for this two-level system falls out in the same way as discussed in

Section 4 for a Stern-Gerlach apparatus.

6. Conclusion

I have attempted to explain the behavior of a Geiger counter in the presence of a slow radioactive decay from a point source as a generalization of an earlier account of the Mott problem in a cloud chamber. Although I do not have a microscopic theory of relevant defects in the Geiger counter window, I have proposed an experiment to investigate this generalization further, and have presented results from an early proof of concept. I have raised the possibility that similar physics accounts for canonical quantum measurement outcomes in Stern-Gerlach experiments, and in superconducting qubits. If the ideas in this paper are borne out by further work, it opens the possibility of quantitatively characterizing when canonical behavior breaks down and how that limits quantum computing technology, or even our ability to measure the lifetime of the proton.

An alternative way to test the track-initiation physics of Geiger counter windows might be to observe alpha tracks in a cloud chamber with a Geiger counter window inserted very close to a small radioactive source. One would expect to see a preponderance of tracks originating at the window itself, rather than at locations elsewhere in the cloud chamber medium.

Similar physics could operate in photographic film, where a photon excites an electron into the conduction band of a silver-halide grain, eventually to be captured by a trap composed of silver atoms [

34]. The conduction-band electron wavefunction is spread over the entire grain, but it may need collimation to be trapped effectively, and perhaps that’s accomplished by a site of leveraged ionization. Something similar might hold for electrons in a CCD pixel.

If leveraged ionization sites somehow existed in liquids, we could calculate limits on the ability of large water-based experiments to detect proton decay [

14] at lifetimes of current theoretical interest.

This picture could possibly also help us understand a pervasive but unquestioned aspect of our everyday world, namely, that almost all particles we observe follow tracks. Perhaps the wavefunctions of particles we deal with every day become collimated by interacting with leveraged ionization sites in condensed matter. (I first pointed out the lack of a practical theory of particle wavepackets in Reference [

35].)

It is obvious that further work is needed. This includes:

A carefully controlled cloud chamber experiment to measure how the origins of tracks from radioactive decay are distributed (making rigorous the data in [

17]).

A carefully controlled cloud chamber experiment in which a Geiger counter window is placed very close to a point source of alpha decay.

A carefully controlled repeat of the experiment described in

Section 3.

A microscopic theory of leveraged ionization in solids and liquids, with particular attention to Geiger-counter windows, real analog-to-digital converters (not just the toy model of

Section 5), photographic grains, CCD pixels, and water.

A careful analysis of the lower limits to |Rc-R| at a leveraged ionization site. This can drive limits to the Born rule.