1. Introduction

In recent times, the aquaculture industry has been focused on enhancing fish welfare and promoting the development of the personal aquarium market, while simultaneously increasing production [

1]. During the cultured period of fish, a plethora of diseases have been observed, associated with physical, infectious, and environmental factors [

2,

3]. Aquaculturists are advised to prioritize disease control to minimize mortality in the event of an outbreak, and numerous researchers have endeavored to provide effective treatment methods [

4]. However, unlike infectious and environmental problems, which can be resolved through chemotherapy and environmental improvement, respectively, physical injuries are difficult to cure due to the osmotic challenges that arise from aquatic living conditions [

5]. As a result, the importance of new surgical techniques for the aggressive treatment of physical diseases in both aquaculture and aquarium fish is gaining attention among researchers [

6]. Some researchers have suggested the availability of surgical techniques as an important aspect of treatment [

7,

8].

Surgery is a useful tool in the treatment of various diseases that require surgical intervention in fish [

9]. For instance, basic surgery can effectively treat physical conditions such as intussusception, ulcers, and tumors [

10,

11,

12]. Although laparotomy is a fundamental technique used in many surgical procedures for both humans and vertebrates, the study of fish surgery remains relatively scarce compared to that of humans and other vertebrates [

7]. Nevertheless, recent studies on the surgical operation of fish have been increasing [

13]. Furthermore, many researchers emphasize the necessity of histopathological analysis to investigate the relationship between wound healing and the microscopic structures of organs [

14].

In this context, sturgeon is a suitable fish species for conducting surgical experiments due to its characteristics of harvest and industrial significance [

15]. Sturgeons have been subjected to abdominal laparoscopic surgery for sex identification, as they have a long reproductive cycle and low spawning rates, making it difficult to distinguish between males and females [

16]. Sturgeon, one of the most widely cultivated freshwater fish, are often slaughtered for its fine food ingredients such as caviar and/or its meat [

17]. As the sturgeon takes a long time to reach maturity and has a low spawning rate, the roe is extracted from mature fish through a caesarian section and then stitched back to enable further spawning [

18]. Additionally, rearing sturgeon until they reach marketable size in a short period is challenging, and satisfying the demand for sturgeon food ingredients within a short period is difficult [

19]. In laparotomy and laparoscopic operations, many sturgeons have died due to infectious diseases, shock, unstable homeostasis, or accidents [

19]. Therefore, it is crucial to maintain the physiological activity of the fish before performing any surgical procedures [

7].

Maintaining homeostasis is crucial during surgical procedures [

7]. The liver is a major organ responsible for homeostasis and immune regulation [

20]. Many researchers suggest that maintaining healthy immunity and optimal physiological activity can aid in disease prevention [

5]. Physiological activity is regulated by temperature, and high temperature has been used in human medicine to improve physiological activity and treat certain injuries [

21]. Improving physiological activity can lead to more rapid wound healing compared to a depressed state [

19]. Therefore, this study focuses on the differences in hepatectomy patients' tolerance and the histopathological responses of internal organs, as well as investigating whether high temperature can provide advantages in wound healing.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fish

A total of forty-eight individuals of the sterlet sturgeon species (

Acipenser ruthenus) were obtained from a farm situated in Incheon, Republic of Korea. Before being allocated to individual experimental aquariums, the specimens were housed in a domestication tank for a period of four weeks, during which they were fed commercial diets. Further elaboration of the experimental parameters can be found in

Table 1.

To assess the health status of the experimental fish, the condition factors (CF) were calculated using the following formula [

22,

23]:

Sampling was performed at 4 weeks after the start of the experiment, with six sturgeons sampled from each group. All samples were labeled with identifiable tags on their fins, enabling the observation of hematological and histological changes specific to each individual.

2.2. Anesthesia

Except for the negative control group, all experimental groups were anesthetized with a concentration of 200 ppm MS-222 (Sigma-Aldrich, United States) [

2,

6], and oxygen was supplied at 30-second intervals through a 3 mL syringe during the surgical procedure.

The duration of anesthesia, handling time, and recovery time were measured for each individual, with anesthesia being based on the cessation of operculum movement and recovery being based on the point at which normal swimming behavior resumed in the tank.

2.3. Hepatectomy

The hepatectomy procedure was executed by employing a simple continuous suture technique (utilizing Blue nylon, 1 metric, Ailee, Republic of Korea), which involved excising roughly 0.1-0.3 g (approximately 20% of the total liver weight) of liver tissue per sample (

Figure 1). Subsequent to suturing, the incision site was coated with iodine, fusidate sodium, and Vaseline to prevent the onset of infection.

The hepatosomatic index (HSI) is an indicator used to assess the liver's relative weight in fish and is calculated as the ratio of liver weight to body weight, expressed as a percentage [

24]:

2.4. Hematological Analysis

Blood samples were collected via the caudal vein using vacutainer tubes such as the SST (serum separation tube) and EDTA (ethylene diamine tetra-acetic acid) tube, and subsequently centrifuged at 1,300 g for a duration of 10 minutes. The following nine parameters were analyzed: alkaline phosphatase (ALP), complement activity, cortisol, glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (GOT), glutamic pyruvic transaminase (GPT), hematocrit (Ht), hemoglobin (Hb), lysozyme activity, and total protein (TP).

The ALP (AM1055), GOT (AM103-K), GPT (AM-102), Hb (AM503), and TP (AM54-1011) measurements were performed using products from Asan Pharm, Republic of Korea, in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol. Complement activity was determined using 100% sheep red blood cells (Innovate-research, India) and following general methods [

25]. Cortisol was measured using the Cortisol ELISA kit (Enzo Life Sciences, Inc., United States) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Hematocrits were determined by transferring blood collected in EDTA tubes to heparin-treated capillary tubes (Sigma-Aldrich, United States), which were then centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 15 minutes before measurement. Lysozyme activity was measured using

Micrococcus lysodeikticus (Sigma-Aldrich, United States) and following general methods [

26,

27].

To observe hematological changes during the experimental period, blood collection was performed at the beginning of the experiment, and at 4 weeks after the start of the experiment, six sturgeons were sampled from each group to observe the changes.

2.5. Histological Analysis

For histological analysis, a total of 18 organs were examined in this study, including the anus (hindgut), body kidney, brain, eye, gall bladder, gill, gonad, head kidney, heart, intestine, liver, muscle, pancreas, pyloric caeca, skin, spleen, stomach, and swim bladder.

Each sample was fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin for a duration of 24 hours. Subsequently, all samples were collected and refixed in the same solution (10% neutral-buffered formalin) for an additional 24 hours prior to being gradually dehydrated through the use of an ethanol series (70-100%). The samples were then cleared with xylene, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned into slices with a thickness of 4 μm. Finally, the sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) following standard protocols, and examined under an optical microscope (Leica DM2500, Germany).

2.6. Image and Statistics Analysis

Image analysis for the histological data was conducted using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, United States).

The statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS 23 program (IBM, United States). To determine the significance of the data, the liver condition was calculated by measuring the cytoplasmic area of the hepatocytes (refer to

Figure 2). Furthermore, following hepatic resection, no significant differences were observed, and the treatment groups were regrouped into the 18°C and 28°C groups. Prior to grouping, every individual datum was checked for statistical insignificance under the same temperature conditions. Statistical significance was assessed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Duncan's multiple range test, with a significance level set at (

p < 0.05).

Due to the uneven distribution of liver tissue conditions among the groups, statistical analysis of liver status was performed using Kruskal-Wallis H test and Scheffe post-hoc analysis. The aforementioned analysis was conducted using R studio (version: 2023.03.0-386) for statistical computing.

2.7. Data Curation with Liver Condition

Data curation was performed on a per-group basis using image analysis, categorized according to the three conditions of hepatocytes: normal, fatty change, and atrophy (

Figure 2). Furthermore, statistical analyses were conducted separately for each liver condition, even within the same low (or high) temperature group.

2.8. Ethical Approval

All experimental protocols followed the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Gyeongsang National University (approval number: GNU-220202-E0016).

3. Results

3.1. Condition Factors and Hepatosomatic Index

3.1.1. Condition Factor (CF)

No mortalities occurred during the experimental period, and as the experiment progressed into its fourth week, a decreasing trend in CF values was observed throughout the entire period, including the control group (

Table 1).

3.1.2. Hepatosomatic Index (HSI)

Differences in HSI values were observed among the groups, with a significant decrease observed at the fourth week, particularly in the 18°C group (including low temperature control)

(Table 1).

3.2. Anesthesia and Recovery Time

The duration of anesthesia and recovery showed significant individual variation, with no significant differences observed among groups. The handling time was found to be longer in the hepatectomy group compared to the laparotomy group, and no significant difference was observed in the time required for anesthesia or recovery based on the condition of the liver tissue (

Table 1).

3.3. Hematological Analysis

The results indicate that there were no statistically significant differences observed in variables other than hematocrits, hemoglobin, and cortisol between the groups. Among the individuals sampled for four consecutive weeks, the high temperature group (including the control group) exhibited significantly higher levels of hematocrits and hemoglobin, while the low temperature group (including the control group) displayed a significant elevation in cortisol levels (

Table 2). At the termination of the experiment, specifically at the 4th week, higher levels of lysozyme activity were observed in the low temperature hepatectomy and laparotomy groups, in comparison to other groups (

Table 2). In particular, cortisol levels were found to be significantly higher in all groups that underwent anesthesia (control, hepatectomy, and laparotomy) compared to the negative control group that did not receive anesthesia. Furthermore, regardless of the presence of hepatic resection or water temperature, a significant negative correlation was observed between cortisol levels and the quality of liver tissue, indicating that cortisol levels decrease as liver tissue quality improves (

Figure 3).

3.4. Histological Analysis

Among the 18 organs analyzed, excluding the body kidney, head kidney, liver, muscle, and spleen, no significant changes were observed (

Figure S1).

Notably, in the head kidney, activation of reticuloendothelial system (RES) was observed in individuals subjected to hepatectomy and laparotomy, and this was more pronounced in the high temperature group (

Figure 4a). Furthermore, a relatively activated hematopoietic tissue was observed in the high temperature group (

Figure 4b). In addition, reticulocytes were observed in the spleen of the high temperature group, including the high temperature control (

Figure 4c). In the body kidney of the high temperature group, including the high temperature control, significant expansion (edema lesions) of the proximal tubule was observed (

Figure 4d). In the control group, the liver displayed normal conditions, whereas the low and high temperature groups exhibited fatty change and atrophy (

Figure 4e). Furthermore, the groups that underwent surgical procedures demonstrated the infiltration of inflammatory cells (including eosinophilic granuloma cells, EGC) and an increase in melanomacrophage centers (MMCs) (

Figure 4f). Obviously, leukocyte infiltration at the suture site was observed in groups that underwent hepatectomy or laparotomy (

Figure 4g-h); however, in the high temperature group, infiltration of muscle fibers indicating a relatively recovered level was also observed (

Figure 4h).

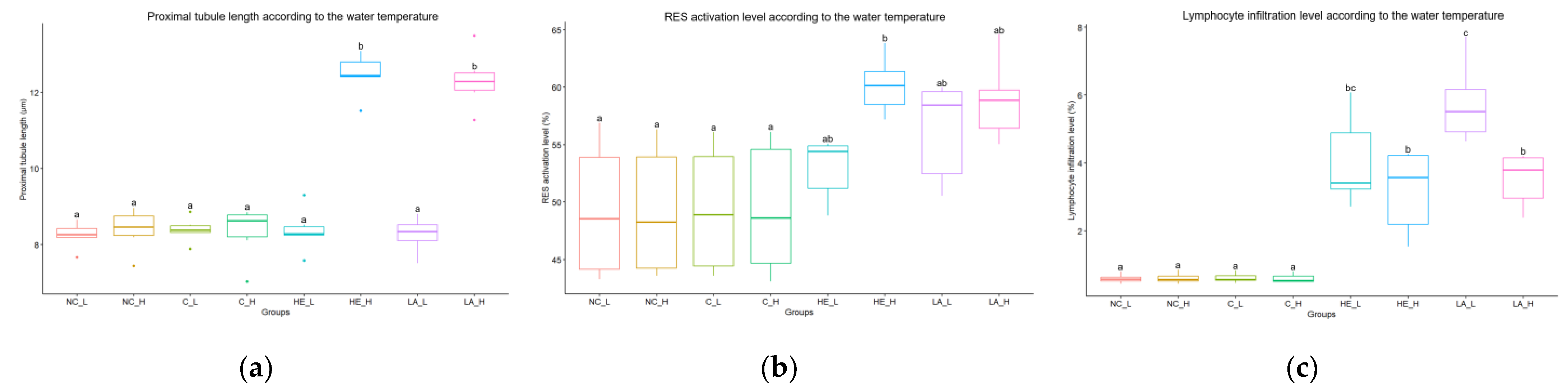

3.5. Image Analysis

The histological analysis of the kidneys and muscles was verified using an image analysis program (ImageJ) to ensure objectivity. The proximal tubule length in the body kidney was significantly higher in the high temperature group (with hepatectomy and laparotomy)

(Figure 5a). The activation level of the RES in the head kidney was significantly higher in the high temperature group (with hepatectomy and laparotomy), and the low temperature group (with hepatectomy and laparotomy) also showed a relatively higher level compared to the control group (

Figure 5b). Additionally, the level of leukocyte infiltration in the wounded muscle was also significantly higher in the low temperature group (with hepatectomy and laparotomy) (

Figure 5c). It has been found that the differences observed in the changes occurring in the kidney and wounded muscle are more significant based on water temperature rather than the condition of the liver tissue.

4. Discussion

It is postulated that the reason for the decline in CF and HSI as the experiment progresses is to facilitate recovery from the damage caused by blood sampling and incision, as evidenced by the relatively lesser decrease in control compared to the hepatectomy and laparotomy groups. Furthermore, it was observed that hematocrits and hemoglobin levels did not fully recover until the 4th week in the experimental group, including the control group sampled early on. This suggests that recovery from the damage caused by blood sampling requires a longer period of time, which warrants further investigation. However, this study has found that high temperatures can facilitate hematopoietic recovery, as demonstrated by the emergence of reticulocytes in the spleen, as well as increased levels of hematocrit and hemoglobin. Furthermore, there was an observed increase in the hematopoietic function of the head kidney [

28].

In this study, high temperature yielded significant results, particularly in the context of wound healing. Specifically, a significant degree of recovery was observed in the sutured areas following hepatectomy or laparotomy compared to the low temperature group. However, it was also noted that excessive induction of physiological activity caused damage (edema lesions) to the proximal tubules of the body kidney. High temperature is a type of thermotherapy used in humans and is known to induce physiological activity [

29,

30].

Moreover, the study demonstrated the pivotal role of liver condition in the statistical analysis, as evidenced by variations in response observed within each group based on the liver condition. Significantly, managing high temperatures and liver condition was found to induce a remarkable improvement in wound healing in the fish. While no significant differences in anesthesia and recovery times were observed based on liver condition, reorganizing the hematological and histological results according to liver condition revealed more notable differences, both visually and non-visually. Specifically, the study found a substantial variation in cortisol levels based on liver condition (depicted in

Figure 3). In contrast, lymphocyte infiltration in the wound site and edema lesions in the renal tubule, as well as RES activity in the head kidney, were found to be more strongly correlated with water temperature (illustrated in

Figure 5).

No significant differences in both hematological and histological analyses were observed between the low and high temperature Control groups. This suggests that hematological and histological changes between the groups were attributed to surgical procedures rather than temperature variations. In the hematological analysis of this study, no significant changes were observed in parameters other than hematocrits, hemoglobin, and cortisol. However, one parameter that requires special attention is cortisol. In this study, a negative control without anesthesia and a control group with anesthesia were compared, and a significant difference in cortisol levels was found between the two groups. In fact, cortisol levels did not show a significant difference between the control group with anesthesia and the group subjected to surgical procedures (

Table 2). This suggests that administering anesthesia itself can be a significant stressor for fish [

31]. Despite the daily administration of commercial diets throughout the experimental period, a significant reduction in weight (with confirmed decrease in CF) was observed in the region where the incision was made (

Table 1), suggesting the need for a greater amount of energy for wound healing.

Overall, based on this study, it has been confirmed that surgical procedures such as hepatectomy and/or laparotomy are not harmful to fish and are applicable techniques. However, further research is needed to clearly understand the stress factor increase caused by anesthesia, blood loss due to venipuncture and surgical procedures, and the time required for complete recovery of the sutured area. Additionally, to promote animal welfare and produce eco-friendly and sustainable fisheries products [

1,

32,

33], subsequent studies must be conducted to apply surgical procedures from a perspective of animal welfare enhancement.

5. Conclusions

The importance of disease control to minimize mortality in fish is emphasized, and surgical techniques are discussed as an important aspect of treatment for physical injuries. Sturgeon is a suitable fish species for conducting surgical experiments due to its industrial significance and long reproductive cycle. This study focuses on investigating whether high temperature can provide advantages in wound healing and improving physiological activity to aid in disease prevention. The use of high temperature has yielded significant results in facilitating hematopoietic recovery and wound healing, although excessive induction of physiological activity can also cause damage. Additionally, hepatectomy and laparotomy have been confirmed as feasible surgical procedures in fish. This study revealed that anesthesia acts as a significant stressor in fish and that there are significant differences in stress response depending on the hepatic tissue status. Thus, the development of anesthesia and analgesics for improving fish welfare is necessary in the future.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: Histological results of other organs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.K.; methodology, G.K.; software, G.K.; validation, G.K.; formal analysis, G.K., W-S.W., K-H.K., H-J.S, M-Y.S.; investigation, G.K.; resources, HJ.K., Y-O.K, D-G.K., EM.K., ES.N.; data curation, G.K.; writing—original draft preparation, G.K.; writing—review and editing, C-I.P.; visualization, G.K.; supervision, C-I.P.; project administration, C-I.P.; funding acquisition, HJ.K., Y-O.K., D-G.K., EM.K., ES.N. “All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research was funded by National Institute of Fisheries Science, Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries, Korea, grant number R2023019.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All experimental protocols followed the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Gyeongsang National University (approval number: GNU-220202-E0016).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Franks, B., et al. (2021). "Animal welfare risks of global aquaculture." Science Advances 7(14): eabg0677. [CrossRef]

- Murray, M. J. (2002). Fish surgery. Seminars in avian and exotic pet medicine, Elsevier.

- Nasr-Eldahan, S., et al. (2021). "A review article on nanotechnology in aquaculture sustainability as a novel tool in fish disease control." Aquaculture International 29: 1459-1480. [CrossRef]

- Neiffer, D. L. and M. A. Stamper (2009). "Fish sedation, anesthesia, analgesia, and euthanasia: considerations, methods, and types of drugs." ILAR journal 50(4): 343-360. [CrossRef]

- Mikryakov, D., et al. (2014). "Effect of dexamethasone on oxidative processes in the immunocompetent organs of sterlet Acipenser ruthenus L." Inland water biology 7: 397-400. [CrossRef]

- Sladky, K. K. and E. O. Clarke (2016). "Fish surgery: presurgical preparation and common surgical procedures." Veterinary Clinics: Exotic Animal Practice 19(1): 55-76.

- Harms, C. A. (2005). "Surgery in fish research: common procedures and postoperative care." Lab animal 34(1): 28-34. [CrossRef]

- Brown, R. S., et al. (2010). "Methods for surgical implantation of acoustic transmitters in juvenile salmonids." Prepared for the US Army Corps of Engineers, Portland District. Contract DE-AC25e76RL01830.

- Cannizzo, S. A., et al. (2016). "Effect of water temperature on the hydrolysis of two absorbable sutures used in fish surgery." Facets 1(1): 44-54. [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y. Z., et al. (2009). "A special type of postoperative intussusception: ileoileal intussusception after surgical reduction of ileocolic intussusception in infants and children." Journal of pediatric surgery 44(4): 755-758. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. W. and G. A. Sarosi (2011). "Emergency ulcer surgery." Surgical Clinics 91(5): 1001-1013.

- Campanella, F., et al. (2015). "Acute effects of surgery on emotion and personality of brain tumor patients: surgery impact, histological aspects, and recovery." Neuro-oncology 17(8): 1121-1131.

- Harms, C. A., et al. (2005). "Behavioral and clinical pathology changes in koi carp (Cyprinus carpio) subjected to anesthesia and surgery with and without intra-operative analgesics." Comparative Medicine 55(3): 221-226.

- Rizzo, A. L., et al. (2017). "Biochemical, histopathologic, physiologic, and behavioral effects of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss)." Comparative Medicine 67(2): 106-111.

- Matsche, M. (2013). "Relative physiological effects of laparoscopic surgery and anesthesia with tricaine methanesulfonate (MS-222) in A tlantic sturgeon A cipenser oxyrinchus oxyrinchus." Journal of Applied Ichthyology 29(3): 510-519.

- Falahatkar, B., et al. (2011). "Laparoscopy, a minimally-invasive technique for sex identification in cultured great sturgeon Huso huso." Aquaculture 321(3-4): 273-279. [CrossRef]

- MUSCALU-NAGY, C., et al. (2007). "OBTAINED RESULTS AFTER APPLYING THERMAL SHOCKS AND PITUITARY EXTRACT INJECTION IN ORDER TO ARTIFICIALLY BREED THE STERLET (ACIPENSER RUTHENUS)." Scientific Papers Animal Science and Biotechnologies 40(2): 37-42.

- Hoseinifar, S. H., et al. (2016). "Probiotic, prebiotic and synbiotic supplements in sturgeon aquaculture: a review." Reviews in Aquaculture 8(1): 89-102. [CrossRef]

- Chapman, F. A. and C. Park (2005). "Comparison of sutures used for wound closure in sturgeon following a gonad biopsy." North American Journal of Aquaculture 67(2): 98-101. [CrossRef]

- Boyer, T. D. and K. D. Lindor (2016). Zakim and Boyer's hepatology: A textbook of liver disease e-book, Elsevier Health Sciences.

- Portela, A., et al. (2010). "An in vitro and in vivo investigation of the biological behavior of a ferrimagnetic cement for highly focalized thermotherapy." Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine 21: 2413-2423. [CrossRef]

- Baxter, A. (1998). "Condition Factor, K, for Salmonid Fish.".

- Kang, G., et al. (2020). "The First Detection of Kudoa hexapunctata in Farmed Pacific Bluefin Tuna in South Korea, Thunnus orientalis (Temminck and Schlegel, 1844)." Animals 10(9): 1705.

- Kumar, P., et al. (2022). "Oocyte growth, gonadosomatic index, hepatosomatic index and levels of reproductive hormones in goldspot mullet Planiliza parsia (Hamilton, 1822) reared in captivity.". [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S., et al. (2018). "Analyzing complement activity in the serum and body homogenates of different fish species, using rabbit and sheep red blood cells." Veterinary immunology and immunopathology 199: 39-42.

- Parry Jr, R. M., et al. (1965). "A rapid and sensitive assay of muramidase." Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine 119(2): 384-386.

- Pridgeon, J. W., et al. (2013). "Chicken-type lysozyme in channel catfish: Expression analysis, lysozyme activity, and efficacy as immunostimulant against Aeromonas hydrophila infection." Fish & Shellfish Immunology 35(3): 680-688. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., et al. (2017). "Characterization of hematopoiesis in Dabry's sturgeon (Acipenser dabryanus)." Aquaculture and fisheries 2(6): 262-268.

- Boni, R. (2019). "Heat stress, a serious threat to reproductive function in animals and humans." Molecular Reproduction and Development 86(10): 1307-1323. [CrossRef]

- Toro-Córdova, A., et al. (2022). "The Therapeutic Potential of Chemo/Thermotherapy with Magnetoliposomes for Cancer Treatment." Pharmaceutics 14(11): 2443. [CrossRef]

- Souza, C. d. F., et al. (2019). "Essential oils as stress-reducing agents for fish aquaculture: a review." Frontiers in physiology 10: 785. [CrossRef]

- Broom, D. M. (2019). "Animal welfare complementing or conflicting with other sustainability issues." Applied Animal Behaviour Science 219: 104829. [CrossRef]

- Keeling, L., et al. (2019). "Animal welfare and the United Nations sustainable development goals." Frontiers in veterinary science 6: 336. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

An image of the abdomen of a sturgeon with the liver excised and sutured is presented: (a) shows the appearance of the excised liver, and (b) depicts a simple running suture.

Figure 1.

An image of the abdomen of a sturgeon with the liver excised and sutured is presented: (a) shows the appearance of the excised liver, and (b) depicts a simple running suture.

Figure 2.

The criteria for categorizing the state of liver tissue are as follows: (a) normal condition (30-45%), (b) fatty change (>45%), and (c) atrophy (<30%) (Scale bar = 50 μm).

Figure 2.

The criteria for categorizing the state of liver tissue are as follows: (a) normal condition (30-45%), (b) fatty change (>45%), and (c) atrophy (<30%) (Scale bar = 50 μm).

Figure 3.

The cortisol levels according to liver condition: (a) cortisol levels before the start of the experiment, (b) cortisol levels at the end of the experiment; NC = negative control, C = control, HE = hepatectomy, LA = laparotomy, N = normal, FC = fatty change, AT = atrophy.

Figure 3.

The cortisol levels according to liver condition: (a) cortisol levels before the start of the experiment, (b) cortisol levels at the end of the experiment; NC = negative control, C = control, HE = hepatectomy, LA = laparotomy, N = normal, FC = fatty change, AT = atrophy.

Figure 4.

Histological results of sturgeons undergoing hepatectomy or laparotomy are presented in the following figures: (a-b) head kidney, (c) spleen, (d) body kidney, (e-f) liver; red circles = the activation of reticuloendothelial system (RES), red arrows = activated hematopoietic tissues, black circles = reticulocytes, black arrows = edema lesions, a white circle = the infiltration of inflammatory cells, white arrows = melanomacrophage centers (MMCs), blue circles = the infiltration of lymphocytes, blue arrows = the infiltration of muscle fibers (Scale bar = 50 μm).

Figure 4.

Histological results of sturgeons undergoing hepatectomy or laparotomy are presented in the following figures: (a-b) head kidney, (c) spleen, (d) body kidney, (e-f) liver; red circles = the activation of reticuloendothelial system (RES), red arrows = activated hematopoietic tissues, black circles = reticulocytes, black arrows = edema lesions, a white circle = the infiltration of inflammatory cells, white arrows = melanomacrophage centers (MMCs), blue circles = the infiltration of lymphocytes, blue arrows = the infiltration of muscle fibers (Scale bar = 50 μm).

Figure 5.

The results of image analysis are presented according to temperature and group, including (a) the length of proximal tubules, (b) the activation level of the reticuloendothelial system (RES), and (c) the level of lymphocyte infiltration; NC = negative control, C = control, HE = hepatectomy, LA = laparotomy, L = low temperature, H = high temperature.

Figure 5.

The results of image analysis are presented according to temperature and group, including (a) the length of proximal tubules, (b) the activation level of the reticuloendothelial system (RES), and (c) the level of lymphocyte infiltration; NC = negative control, C = control, HE = hepatectomy, LA = laparotomy, L = low temperature, H = high temperature.

Table 1.

Samples and experimental conditions used in this study.

Table 1.

Samples and experimental conditions used in this study.

| Conditions |

Status1)

|

NegativeControl I |

NegativeControl II |

Control I |

Control II |

Hepatectomy I |

Hepatectomy II |

Laparotomy I |

Laparotomy II |

| Weight (g) |

Pre |

154.2 ± 34.7 |

156.6 ± 39.3 |

151.3 ± 28.0 |

160.4 ± 33.7 |

145.0 ± 41.6 |

153.7 ± 31.6 |

152.6 ± 37.5 |

145.1 ± 49.3 |

| End |

151.4 ± 33.7 |

153.9 ± 38.1 |

146.8 ± 25.6 |

156.9 ± 32.8 |

136.0 ± 43.8 |

137.7 ± 28.4 |

146.3 ± 38.6 |

131.3 ± 44.5 |

| Length (cm) |

Pre |

27.7 ± 2.7 |

27.4 ± 3.3 |

28.6 ± 2.8 |

27.9 ± 2.6 |

27.9 ± 2.4 |

28.7 ± 1.9 |

28.7 ± 2.2 |

27.6 ± 3.3 |

| End |

27.6 ± 2.7 |

27.3 ± 3.3 |

28.6 ± 2.8 |

27.9 ± 2.6 |

28.4 ± 2.3 |

28.7 ± 1.9 |

28.9 ± 2.4 |

27.8 ± 3.5 |

| ConditionFactor |

Pre |

0.72 ± 0.05 |

0.76 ± 0.11 |

0.64 ± 0.05 |

0.73 ± 0.06 |

0.65 ± 0.04 |

0.64 ± 0.01 |

0.63 ± 0.04 |

0.67 ± 0.04 |

| End |

0.72 ± 0.06 |

0.76 ± 0.11 |

0.59 ± 0.04 |

0.72 ± 0.06 |

0.58 ± 0.05 |

0.58 ± 0.03 |

0.59 ± 0.05 |

0.59 ± 0.05 |

| Hepatosomatic index (%) |

End |

1.03 ± 0.08 |

0.86 ± 0.21 |

1.11 ± 0.20 |

0.97 ± 0.15 |

0.97 ± 0.20 |

0.70 ± 0.15 |

0.97 ± 020 |

0.70 ± 0.11 |

| Temperature (°C) |

- |

18 ± 0.5 |

28 ± 0.7 |

18 ± 0.5 |

28 ± 0.7 |

18 ± 0.5 |

28 ± 0.7 |

18 ± 0.5 |

28 ± 0.7 |

| DO (mg/L) |

- |

9 ± 0.1 |

7.6 ± 0.1 |

9 ± 0.1 |

7.6 ± 0.1 |

9 ± 0.1 |

7.6 ± 0.1 |

9 ± 0.1 |

7.6 ± 0.1 |

| pH |

- |

6.5 ± 0.1 |

6.5 ± 0.1 |

6.5 ± 0.1 |

6.5 ± 0.1 |

6.5 ± 0.1 |

6.5 ± 0.1 |

6.5 ± 0.1 |

6.5 ± 0.1 |

| Time (seconds) |

Anesthesia |

Pre |

- |

- |

785.2 ± 113.8 |

808.5 ± 62.1 |

731.5 ± 204.1 |

777.3 ± 217.7 |

941.2 ± 264.8 |

690.0 ± 153.7 |

| End |

- |

- |

436.0 ± 41.2 |

445.3 ± 36.0 |

481.7 ± 121.4 |

749.7 ± 323.5 |

560.0 ± 138.3 |

795.8 ± 277.4 |

| Handling |

Pre |

306.7 ± 26.4 |

297.8 ± 26.9 |

305.5 ± 39.6 |

300.3 ± 14.6 |

621.5 ± 51.5 |

543.5 ± 17.6 |

492.5 ± 20.5 |

479.5 ± 23.8 |

| Recovery |

Pre |

- |

- |

1034.2 ± 295.3 |

828.3 ± 139.6 |

762.0 ± 335.6 |

229.5 ± 58.0 |

449.5 ± 182.7 |

263.3 ± 126.1 |

Table 2.

Results of hematological analysis.

Table 2.

Results of hematological analysis.

| Parameters |

Status1)

|

NegativeControl I |

NegativeControl II |

Control I |

Control II |

Hepatectomy I |

Hepatectomy II |

Laparotomy I |

Laparotomy II |

| Hematocrits(%) |

Pre |

28.8 ± 3.0 |

30.0 ± 1.5 |

28.5 ± 4.4 |

28.2 ± 1.3 |

26.7 ± 2.8 |

29.8 ± 1.2 |

29.7 ± 5.8 |

27.2 ±3.9 |

| End |

12.0 ± 1.4 |

19.0 ± 2.5 |

12.5 ± 1.6 |

19.2 ± 2.3 |

9.2 ± 4.2 |

18.2 ± 1.6 |

15.2 ± 2.8 |

19.2 ± 3.2 |

| Hemoglobin(g/dL) |

Pre |

8.53 ± 1.28 |

8.43 ± 0.37 |

6.86 ± 0.45 |

8.39 ± 0.71 |

6.49 ± 0.81 |

8.44 ± 0.88 |

7.59 ± 0.69 |

8.04 ± 0.93 |

| End |

4.07 ± 0.39 |

5.88 ± 0.73 |

4.07 ± 0.44 |

5.89 ± 1.14 |

3.84 ± 0.86 |

5.33 ± 0.58 |

4.91 ± 0.99 |

5.62 ± 0.67 |

| Cortisol(ng/mL) |

Pre |

5.82 ± 1.42 |

5.52 ± 1.85 |

14.51 ± 3.29 |

15.78 ± 5.75 |

13.06 ± 5.93 |

15.36 ± 4.97 |

18.82 ± 9.50 |

14.41 ± 5.12 |

| End |

6.06 ± 1.60 |

5.28 ± 1.64 |

18.54 ± 4.11 |

18.24 ± 5.13 |

13.67 ± 4.71 |

18.06 ± 6.76 |

14.53 ± 3.89 |

16.31 ± 6.32 |

| ALP(U/L) |

Pre |

17.89 ± 1.81 |

18.05 ± 2.04 |

18.10 ± 1.75 |

18.21 ± 2.15 |

13.42 ± 2.42 |

13.95 ± 3.84 |

12.96 ± 0.98 |

15.24 ± 5.56 |

| End |

10.53 ± 2.41 |

10.44 ± 2.06 |

10.67 ± 2.25 |

10.42 ± 2.15 |

9.49 ± 1.55 |

9.45 ± 1.36 |

8.36 ± 1.56 |

10.51 ± 2.28 |

| Complement activity (%) |

Pre |

3.59 ± 1.05 |

3.74 ± 0.72 |

3.67 ± 1.07 |

3.58 ± 1.27 |

2.98 ± 0.47 |

3.00 ± 1.01 |

2.89 ± 1.00 |

5.08 ± 2.96 |

| End |

5.57 ± 1.68 |

5.61 ± 1.58 |

5.75 ± 1.46 |

4.74 ± 0.74 |

4.83 ± 1.61 |

5.06 ± 2.06 |

5.02 ± 2.13 |

5.69 ± 2.51 |

| GOT(U/L) |

Pre |

224.77 ± 18.50 |

224.74 ± 18.06 |

224.92 ± 18.20 |

224.75 ± 18.06 |

224.83 ± 39.73 |

217.36 ± 18.82 |

219.79 ± 34.45 |

206.51 ± 11.33 |

| End |

191.42 ± 29.13 |

191.40 ± 28.86 |

191.24 ± 29.05 |

191.33 ± 28.95 |

182.40 ± 35.91 |

165.10 ± 20.05 |

171.91 ± 40.29 |

185.17 ± 37.58 |

| GPT(U/L) |

Pre |

51.37 ± 14.71 |

51.20 ± 14.45 |

51.41 ± 14.59 |

51.12 ± 14.61 |

42.43 ± 14.11 |

31.05 ± 7.70 |

47.62 ± 26.18 |

36.21 ± 10.07 |

| End |

20.42 ± 8.22 |

20.36 ± 8.18 |

20.46 ± 7.99 |

20.15 ± 8.27 |

21.85 ± 9.22 |

20.18 ± 4.50 |

22.16 ± 14.63 |

21.07 ± 5.20 |

| Lysozymeactivity(units/mL) |

Pre |

2.19 ± 1.04 |

5.78 ± 3.12 |

3.64 ± 2.97 |

5.09 ± 3.42 |

3.29 ± 1.57 |

3.75 ± 1.84 |

2.87 ± 1.21 |

4.44 ± 1.58 |

| End |

3.71 ± 1.09 |

3.73 ± 2.53 |

4.54 ± 2.24 |

3.88 ± 1.46 |

6.33 ± 5.09 |

3.54 ± 2.70 |

5.78 ± 3.68 |

2.94 ± 1.60 |

| TP(g/dL) |

Pre |

0.80 ± 0.20 |

0.80 ± 0.19 |

0.79 ± 0.21 |

0.78 ± 0.20 |

0.84 ± 0.29 |

1.09 ± 0.23 |

0.93 ± 0.28 |

1.13 ± 0.45 |

| End |

0.51 ± 0.09 |

0.52 ± 0.09 |

0.52 ± 0.09 |

0.52 ± 0.09 |

0.61 ± 0.25 |

0.47 ± 0.17 |

0.54 ± 0.31 |

0.36 ± 0.12 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).