Submitted:

15 May 2023

Posted:

15 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Mathematical formulation

2.1. Conservation equations

2.2. Projection method

- Step 1

- 2.

- Step 2

- 3.

- Step 3

- 4.

- Step 4

3. Results and discussion

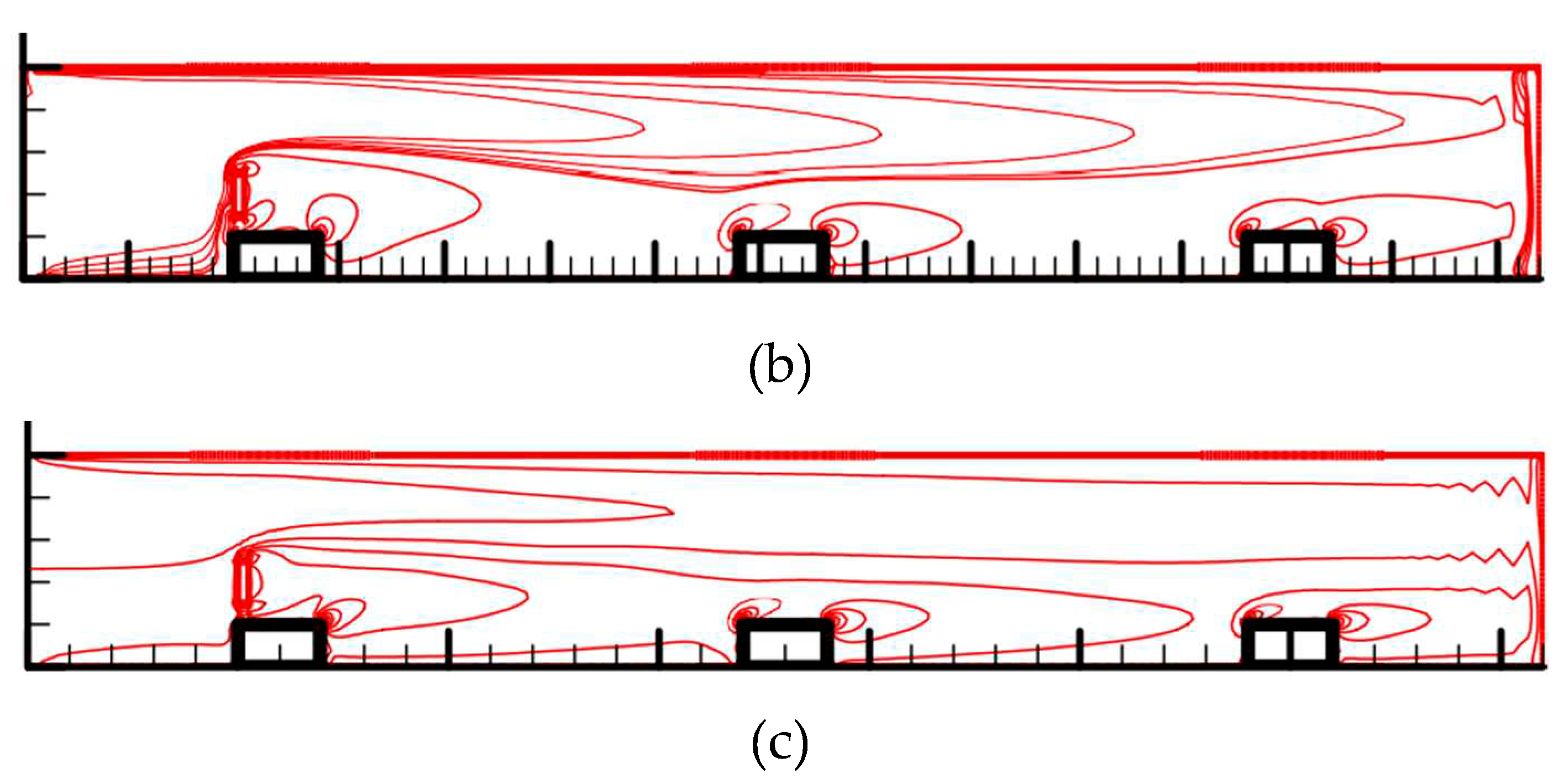

3.1. Mesh independence test and model validation

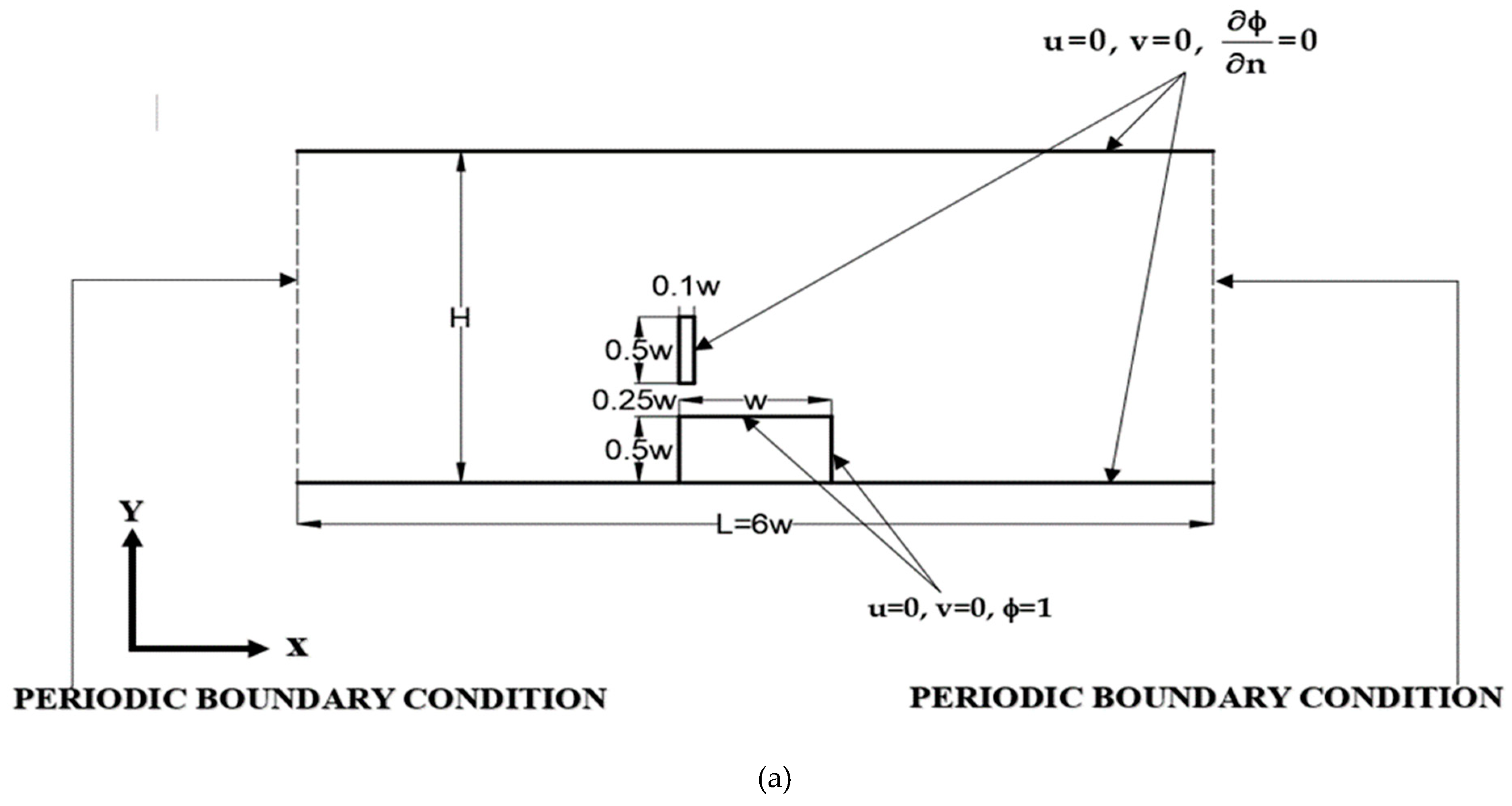

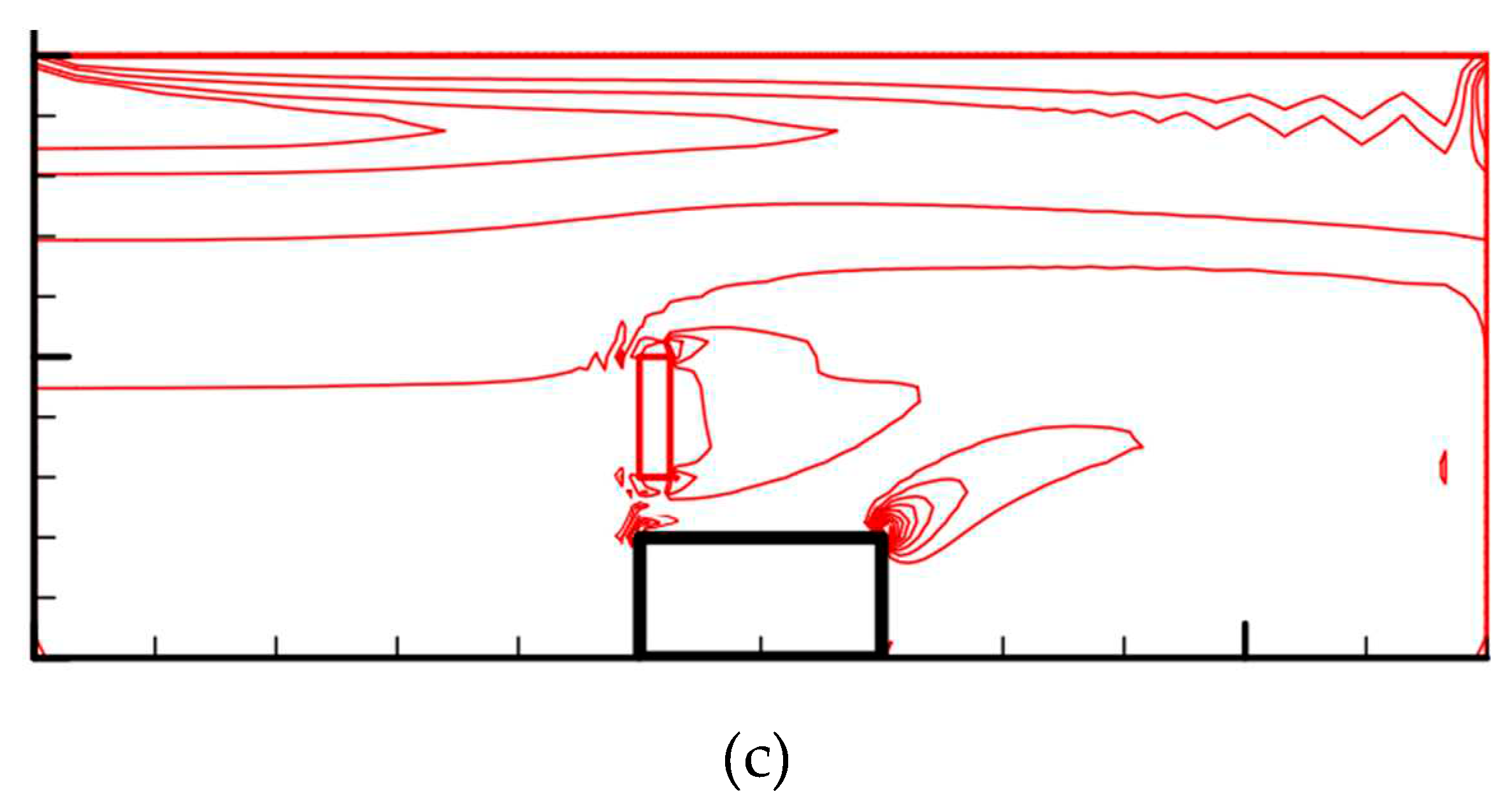

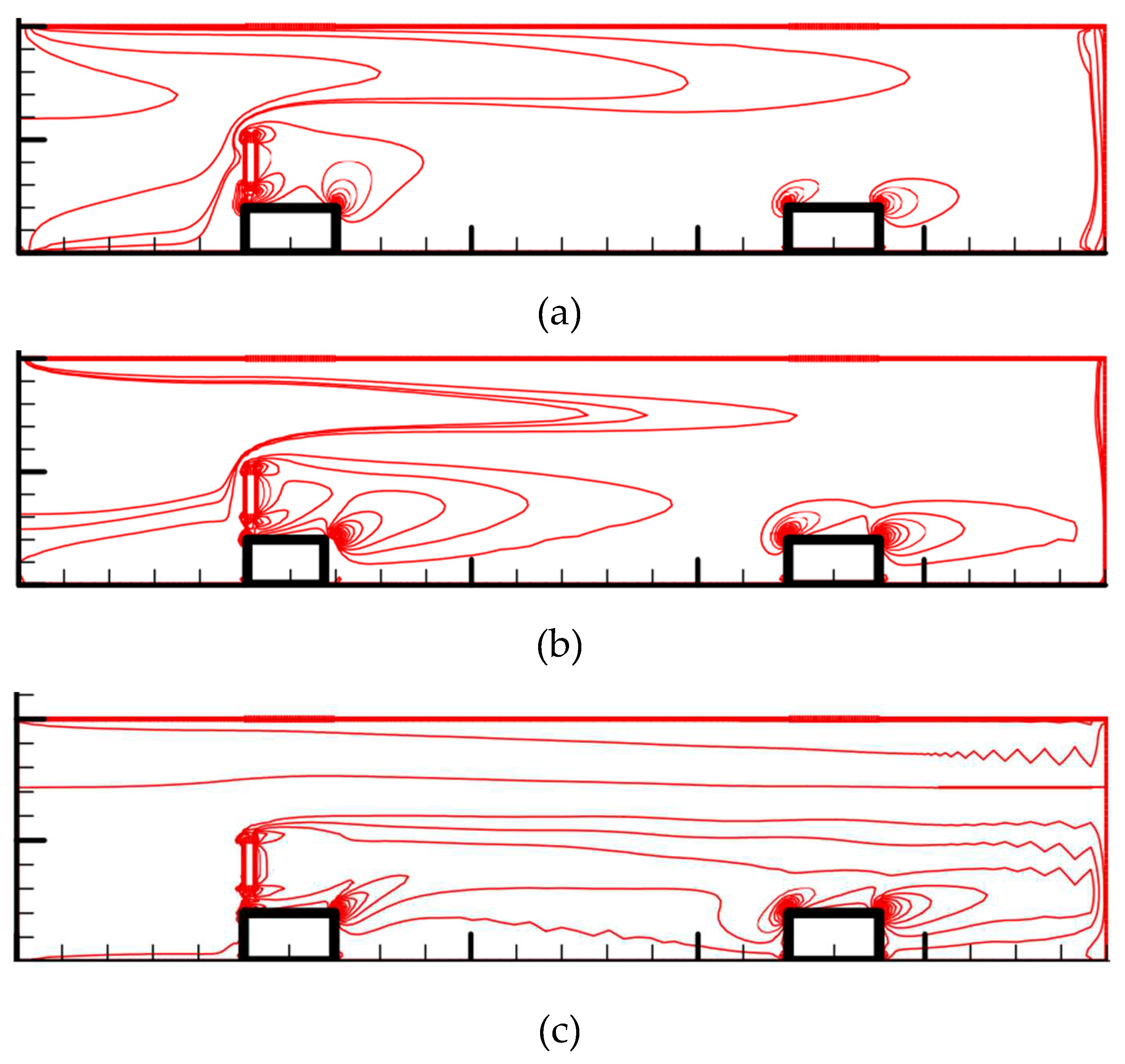

3.2. The arrangement geometries for periodic boundary conditions

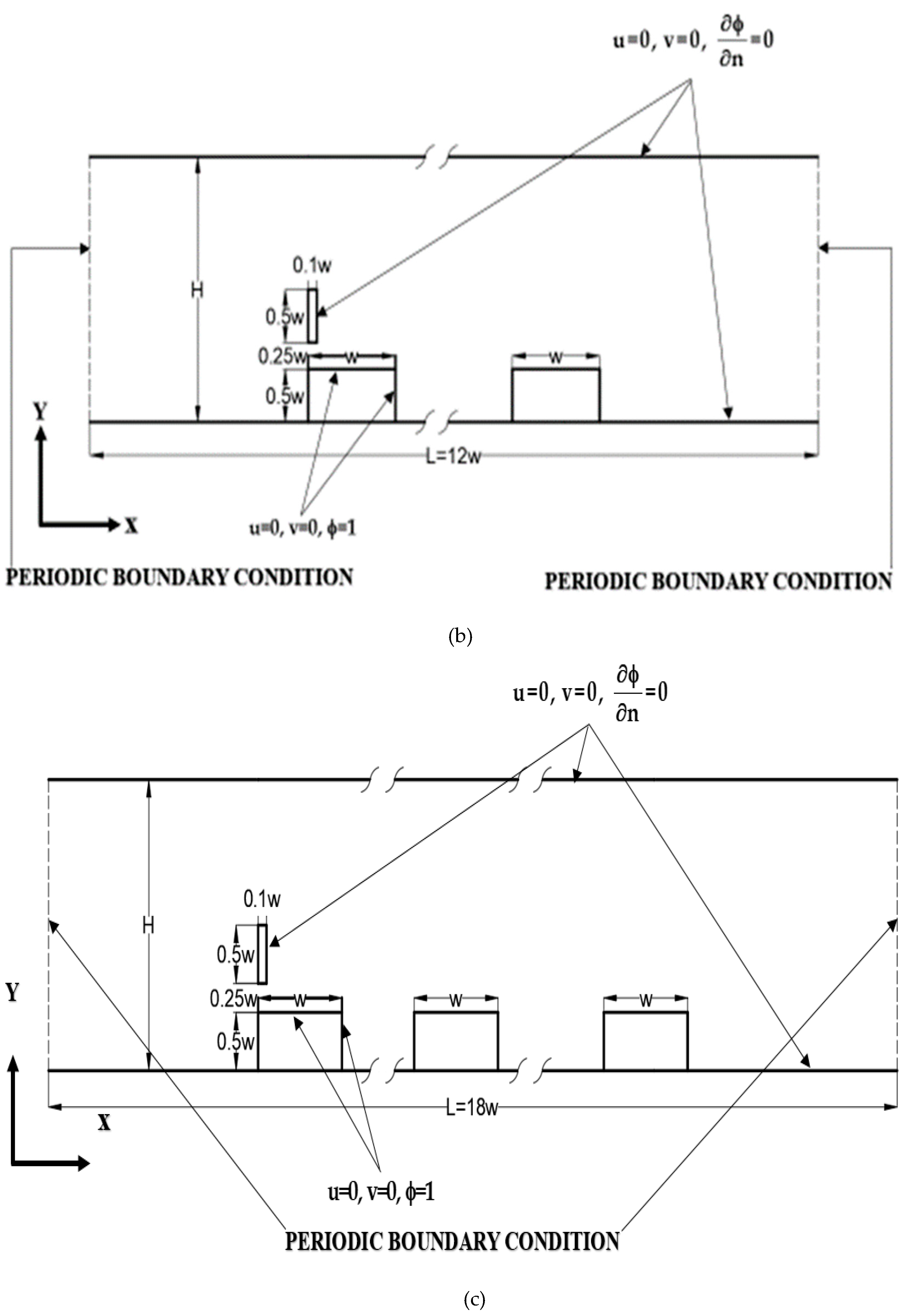

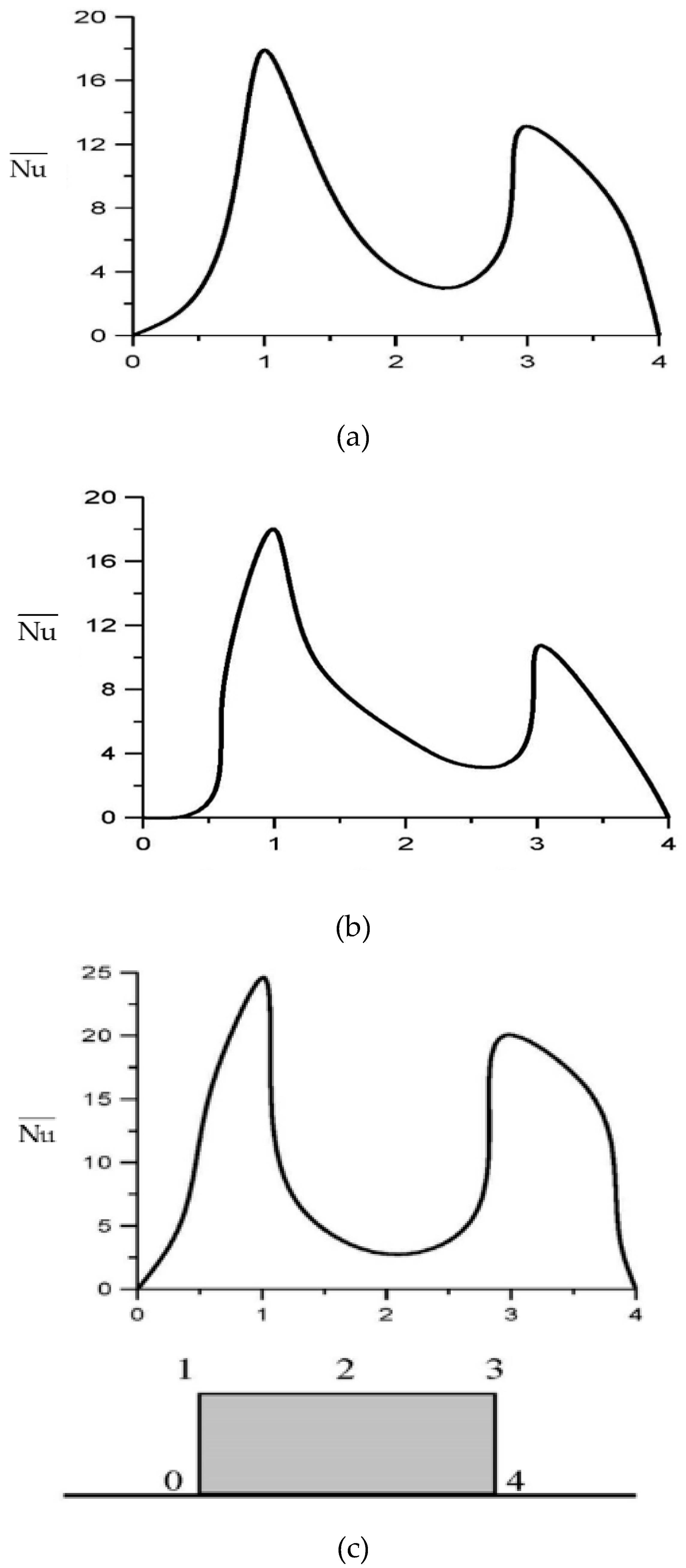

3.3. Time-averaged Nusselt number on heated blocks

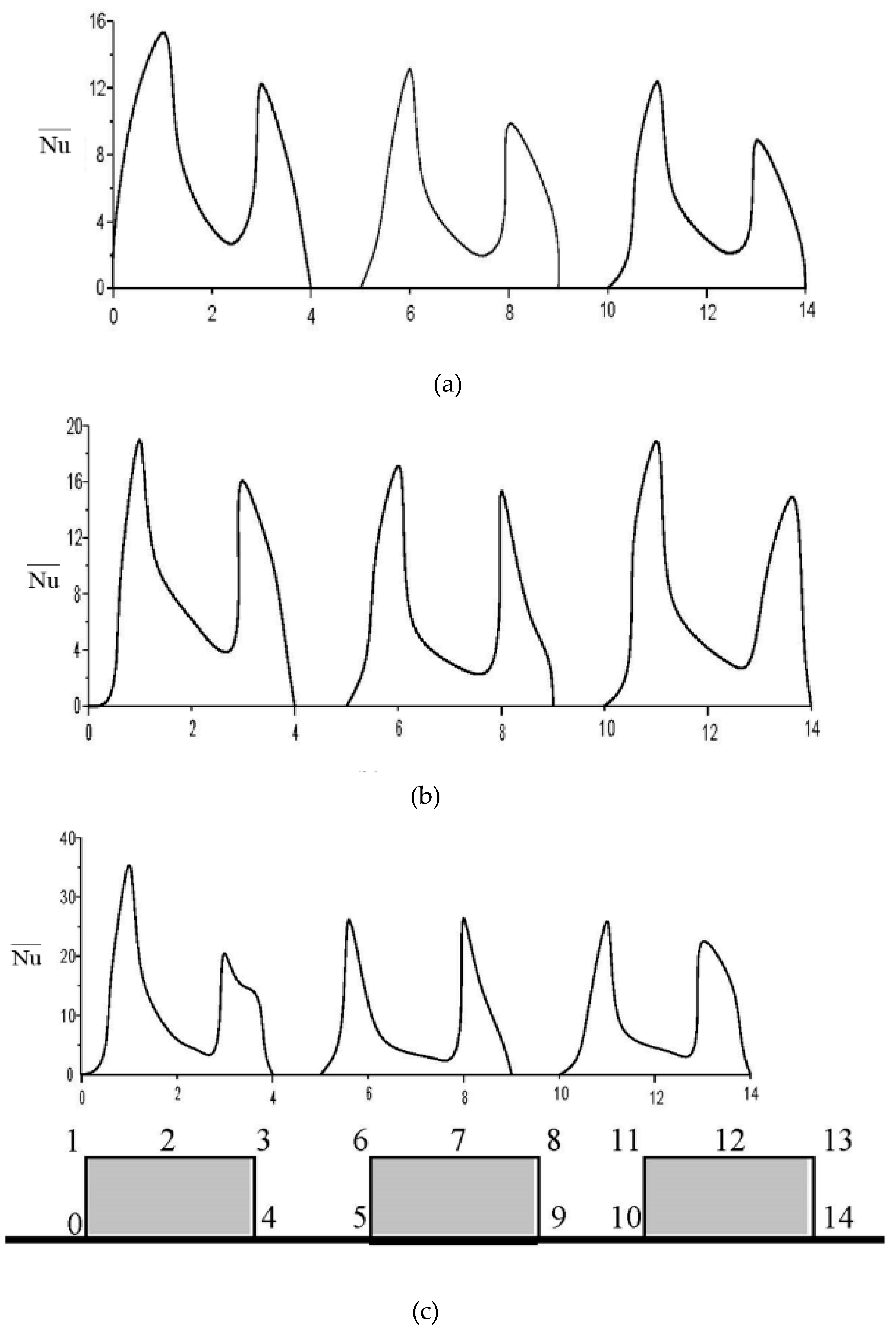

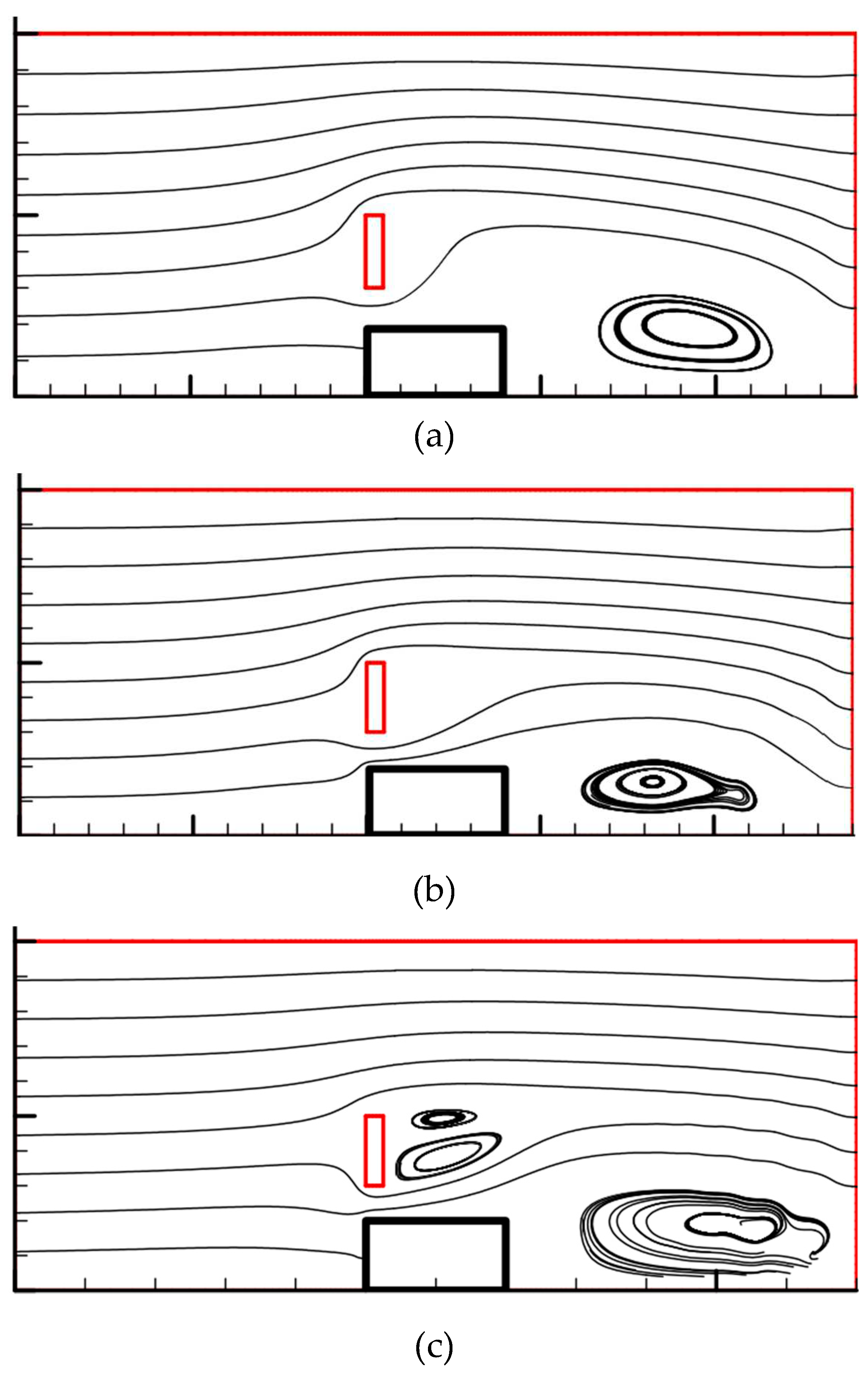

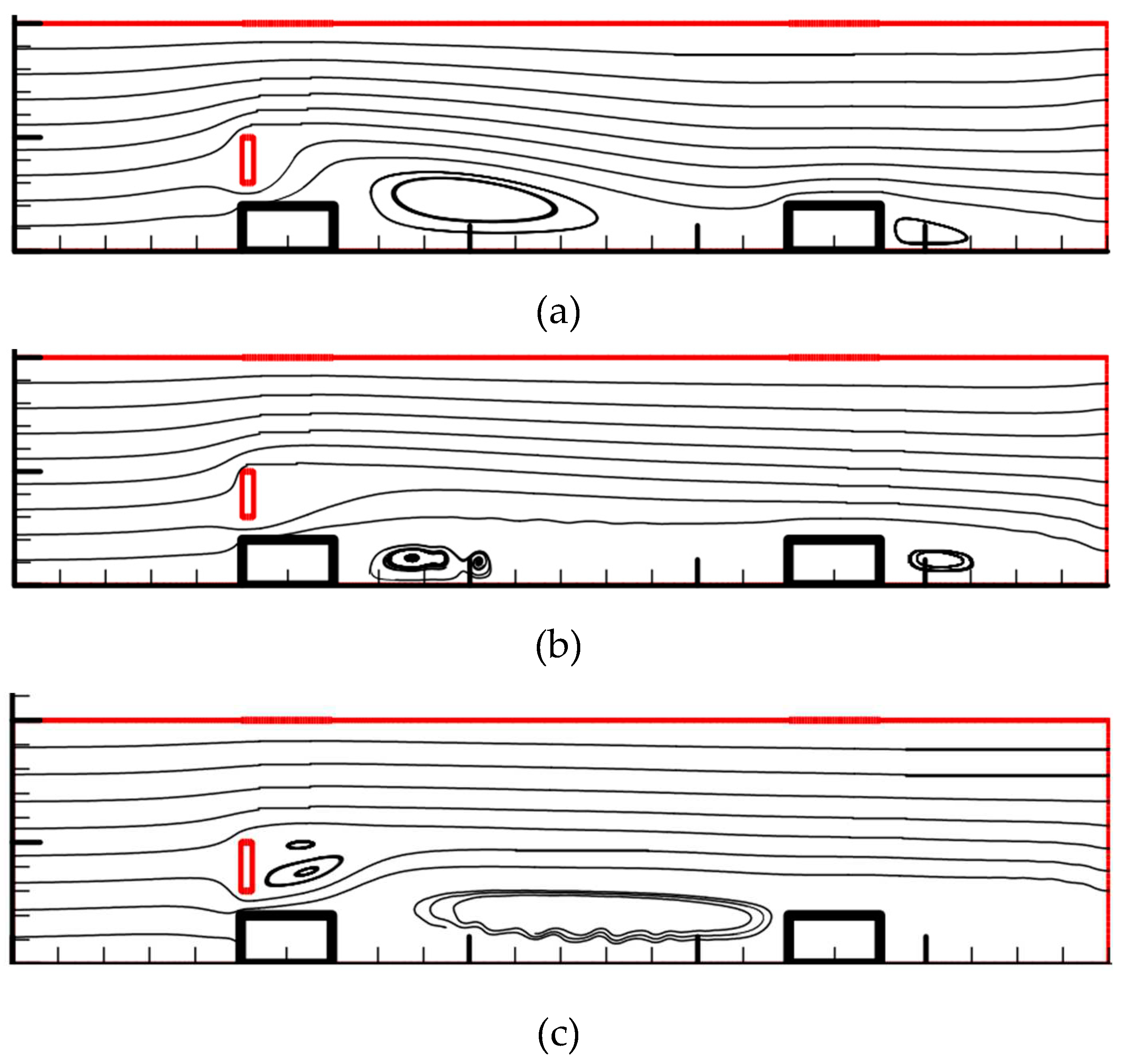

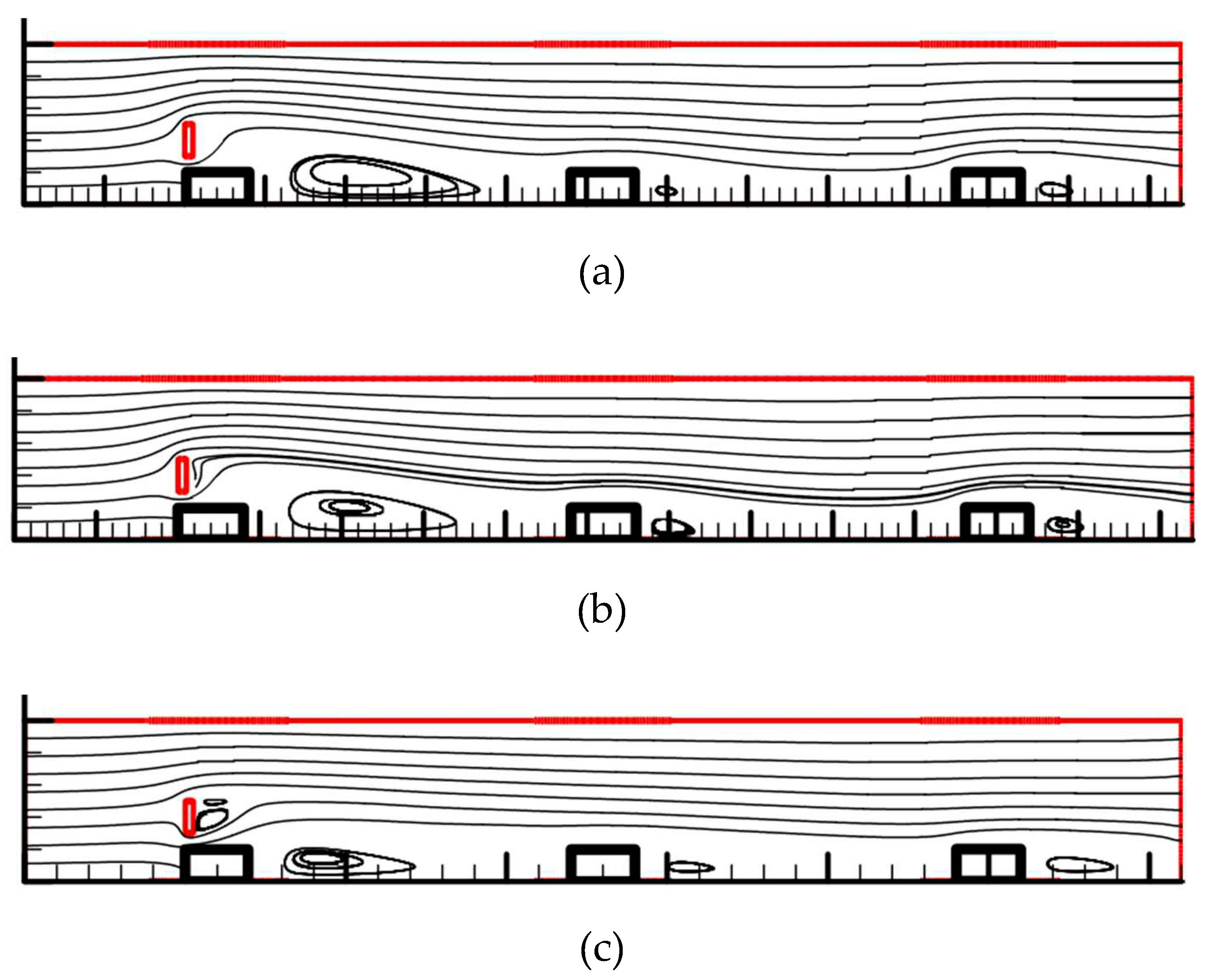

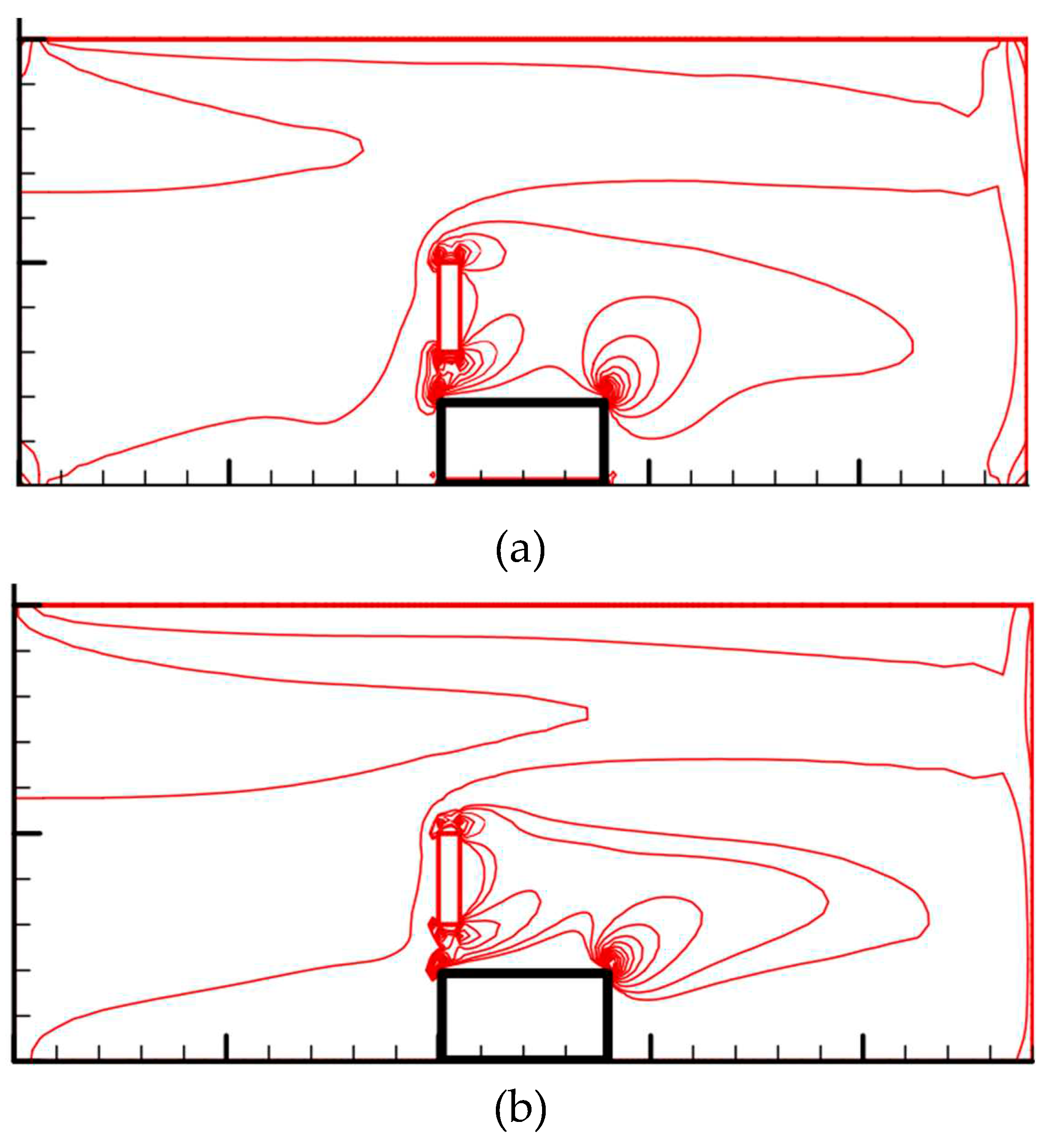

3.4. Streamlined patterns and temperature contours

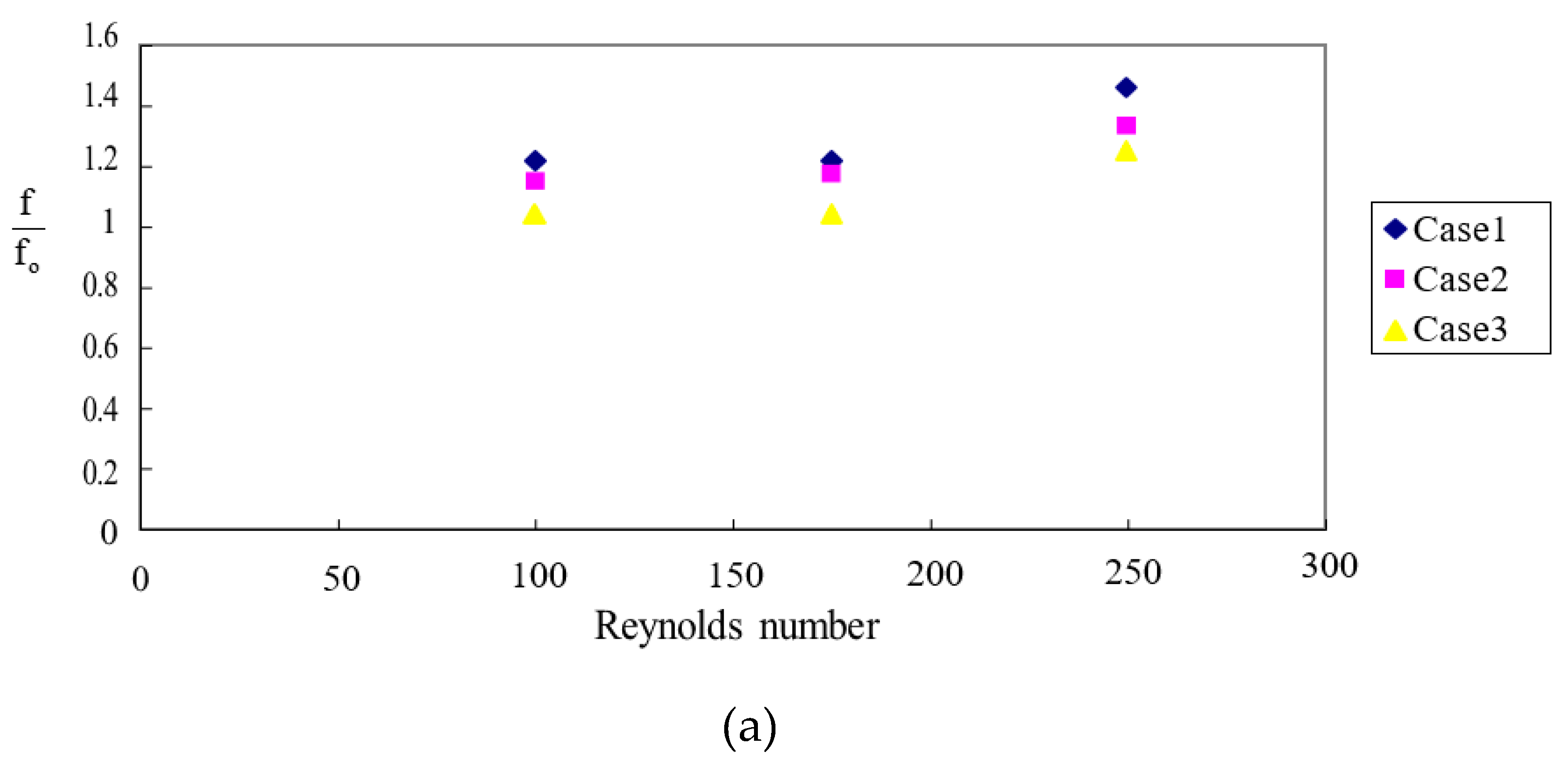

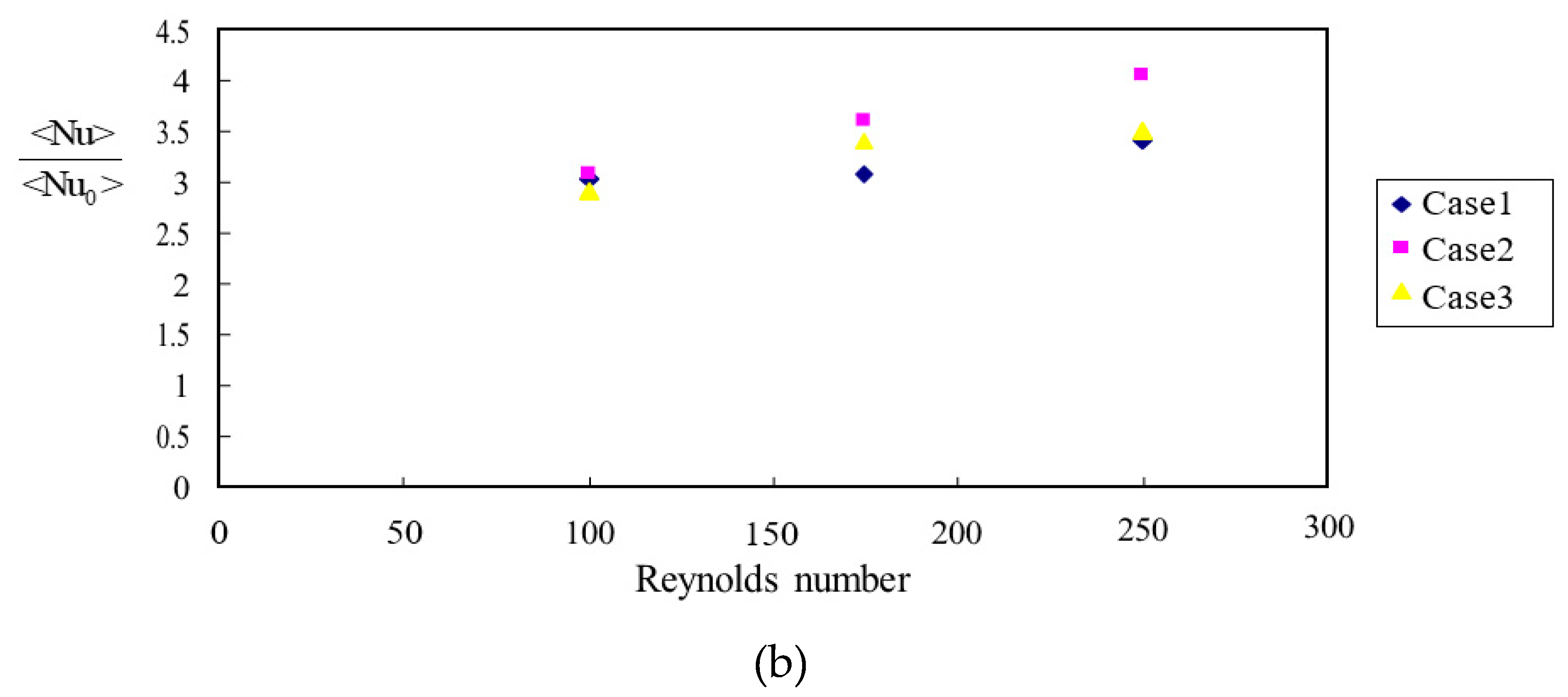

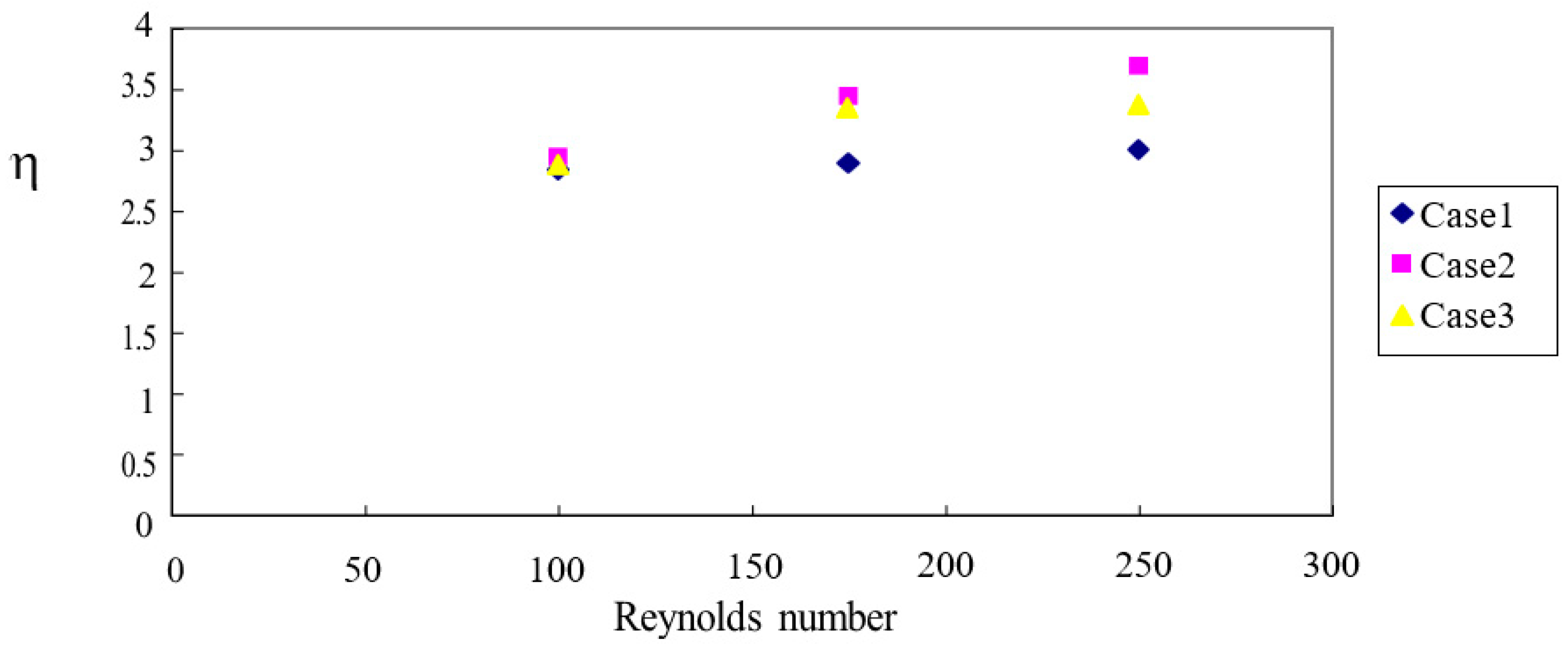

3.5. Friction enhancement, Nusselt number enhancement and thermal performance coefficient

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| A | duct cross-section area (m2) |

| A | diffusion matrix in energy equation |

| CD | drag coefficient |

| CL | lift coefficient |

| dh | hydraulic diameter (m) |

| f | friction factor () |

| H | duct height (m) |

| H | pressure gradient matrix or divergence matrix |

| h | convective coefficient (W/m2-oC) |

| K | convection matrix |

| L | duct length (m) |

| M | mass matrix |

| n | number of calculation |

| Nu | local Nusselt number (= hw/k) |

| time-mean Nusselt number | |

| area average of time-mean Nusselt number | |

| p* | pressure (kPa) |

| p | non-dimensional pressure |

| p | pressure vector of the node |

| Pr | Prandtl number (= ν /α ) |

| Re | Reynolds number (= u¥H /ν) |

| S | diffusion matrix in momentum equation |

| St | Strouhal number |

| t* | time(sec) |

| t | dimensionless time (t * /(w / u¥)) |

| T | temperature (oC) |

| T | reference temperature (oC) |

| u | dimensionless horizontal velocity |

| u¥ | the cross-section mean velocity (m/s ) |

| u | velocity vector at the node |

| v | dimensionless vertical speed |

| w | block width |

| x | dimensionless horizontal coordinate |

| y | dimensionless vertical coordinate |

| Δt | dimensionless time step size |

| Subscripts | |

| W | block surface |

| 0 | without rectangular cylinder |

| Superscript | |

| * | dimensional variables |

| Greeks | |

| thermal diffusivity (m2/s) | |

| H | thermal performance |

| kinematic viscosity coefficient (m2/s) | |

| density (kg/m3) | |

| non-dimensional temperature |

References

- Hughes, T.J.R. ; Levit I; Winget J. Element-By-Element Implicit Algorithms for Heat Conduction. Journal of Engineering Mechanics, 1983, 109, 576–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, T.J.; Levit, I.; Winget, J. An element-by-element solution algorithm for problems of structural and solid mechanics. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 1983, 36, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, M.; Pinsky, P.M.; Taylor, R.L. Unconditionally stable element-by-element algorithms for dynamic problems. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 1983, 36, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winget, J.M. Element by Element Solution Procedures for Nonlinear transient heat condition analysis. Ph.D. Thesis, California Institute of Technology, 1983.

- Hughes, T.J.R.; Winget, J. ; Levit I; Tezduyar T.E. New Alternate Directions Procedure in Finite Element Analysis Based Upon EBE Approximate Factorization, Proceedings of the Symposium on Recent Developments in Computer Methods for Nonlinear Solid and Structural Mechanics. Proceedings of the ASME Joint Meeting of Fluid Engineering, Applied Mechanics and Bioengineering, University of Houston, Texas, 1983.

- Hughes, T.J.R.; Raefsky, A.; Muller, A.; Winget, J.; Levit, I. A Progress Report on EBE Solution Proceedings in Solid Mechanics. Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Nonlinear Problems, Barcelona, Spain, 1984.

- Levit, I. Element by element solvers of order N. Comput. Struct. 1987, 27, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, G.F.; Jiang, B.-N. Element-by-element linear and nonlinear solution schemes. Commun. Appl. Numer. Methods 1986, 2, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wathen, A.J. An Analysis of Some Element-By-Element Techniques. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, 1989, 74, 271–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erhel, J.; Traynard, A.; Vidrascu, M. An element-by-element preconditioned conjugate gradient method implemented on a vector computer. Parallel Comput. 1991, 17, 1051–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadrakakis, M.; Dracopoulos, M.C. A global preconditioner for the element-by-element solution methods. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 1991, 88, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizukami, A. Element-by-Element Penalty / Uzawa Formulation for Large Scale Flow Problems. Computer Methods In Applied Mechanics and Engineering, 1994, 112, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Reed, M.B. Convergence Analysis for an Element-by-Element Finite Element Method. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, 1995, 123, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunmonu, A. Implementation of a novel element-by-element finite element method on the hypercube. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 1995, 123, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, M.; Reddy, J. Multigrid methods to accelerate convergence of element-by-element solution algorithms for viscous incompressible flows. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 1996, 132, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakabayashi, Y.; Okuda, H.; Yagawa, G. Parallel Finite Element Fluid Analysis on An Element-By-Element Basis. Computational Mechanics, 1996, 18, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chorin, A.J. Numerical Solution of Navier-Stokes Equations. Mathematics of computation, 1968, 22, 745–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy, B.; Jue, T.C.; Akin, J.E. Semi-implicit and explicit finite element schemes for coupled fluid/thermal problems. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 1992, 34, 675–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C.G.; Nithiarasu, P.; Bevan, R.L.T. The locally conservative Galerkin (LCG) method for solving the incompressible Navier-Stokes equations. Int. J. Numer. Methods Fluids 2007, 57, 1771–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savović, S.; Caldwell, J. Finite difference solution of one-dimensional Stefan problem with periodic boundary conditions. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2003, 46, 2911–2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, H.; Sawada, K.-I.; Suzuki, K. Applicability of spatially periodic boundary conditions to a numerical computation of flow in a channel obstructed by an array of square rods. Heat Transf. 2004, 33, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patankar, C. H. Liu and E. M. Sparrow, Fully developed flow and heat transfer in ducts having streamwise-periodic variation of cross-sectional area, Am. Sot. Mech. Enyrs, Series C, J. Heat Transfer 99, 180-186, (1977).

- Gunes, H. Analytical solution of buoyancy-driven flow and heat transfer in a vertical channel with spatially periodic boundary conditions. Heat Mass Transf. 2003, 40, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Li, Z.Y.; He Y., L.; Tao W., Q. Discussion on numerical treatment of periodic boundary condition for temperature. Numerical Heat Transfer, Part B, 2007, 52, 429–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, T.M.; Chang, S.W.; Hung, J.H.; Chiou, S.F. High rotation number heat transfer of a 45o rib-roughened rectangular duct with two channel orientations. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 2007, 50, 4063–4078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, T.M.; Chen, S.H.; Shih, K.C. Numerical simulation of turbulent flow field and heat transfer in a two-dimensional channel with periodic slit ribs. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 2002, 45, 4493–4505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, W.; Cai, J.; Huai, X. Numerical investigation on fluid-solid coupled heat transfer with variable properties in cross-wavy channels using half-wall thickness multi-periodic boundary conditions. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 2018, 122, 1040–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimian, S.M.; Straatman, A.G. A thermal periodic boundary condition for heating and cooling processes. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 2007, 28, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, E.; Vicente, W.; Salinas-Vazquez, M.; Carvajal, I.; Alvarez, M. Numerical simulation of turbulent air flow on a single isolated finned tube module with periodic boundary conditions. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2015, 92, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, B.; Rao, K.K.; Kumaran, V. Different shear regimes in the dense granular flow in a vertical channel. J. Fluid Mech. 2022, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, M ; Ha, MY; Min, JK A numerical study of the mixed convection around slanted-pin fins on a hot plate in vertical and inclined channels, International Communications in Heat and Mass Transfer, 2020, 118, Article No. 10 4878.

| Case | Mesh |

|---|---|

| Without Rectangular cylinder |

Mesh 1 (element number: 1722;node number: 1621) Mesh 2 (element number: 3314;node number: 3164) Mesh 3 (element number: 4002;node number: 3836) |

| 1 | Mesh 1 (element number: 727;node number: 700) Mesh 2(element number: 1451;node number: 1407) Mesh 3 (element number: 2176;node number:2114) |

| 2 | Mesh 1 (element number: 1454;node number: 1400) Mesh 2 (element number: 2902;node number: 2814) Mesh 3 (element number: 4352;node number: 4228) |

| 3 | Mesh 1 (element number: 2181;node number: 2100) Mesh 2 (element number: 4353;node number: 4221) Mesh 3(element number: 6528;node number:6342) |

| Murata et al. [21] | Present paper | |

|---|---|---|

| Strouhal number | 0.30 | 0.31 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).