Submitted:

12 May 2023

Posted:

15 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Plant material

2.2. Experimental design

2.3. Analysis

2.3.1. FTIR

2.3.2. Fresh mass loss

2.3.3. Firmness

2.3.4. Colorimetric analysis

2.3.5. Soluble solids (SS)

2.3.6. Titratable acidity (TA)

2.3.7. Hydrogenionic potential

2.3.8. Ascorbic acid (AA)

2.3.9. Lycopene and β-carotene

2.3.10. Total phenolic compounds (CF)

2.3.11. Total sugars

2.3.12. Total proteins

2.3.13. Enzyme catalase

2.3.14. Minerals Fe, Cu, K, Na, Mg, and Mn

3. Results

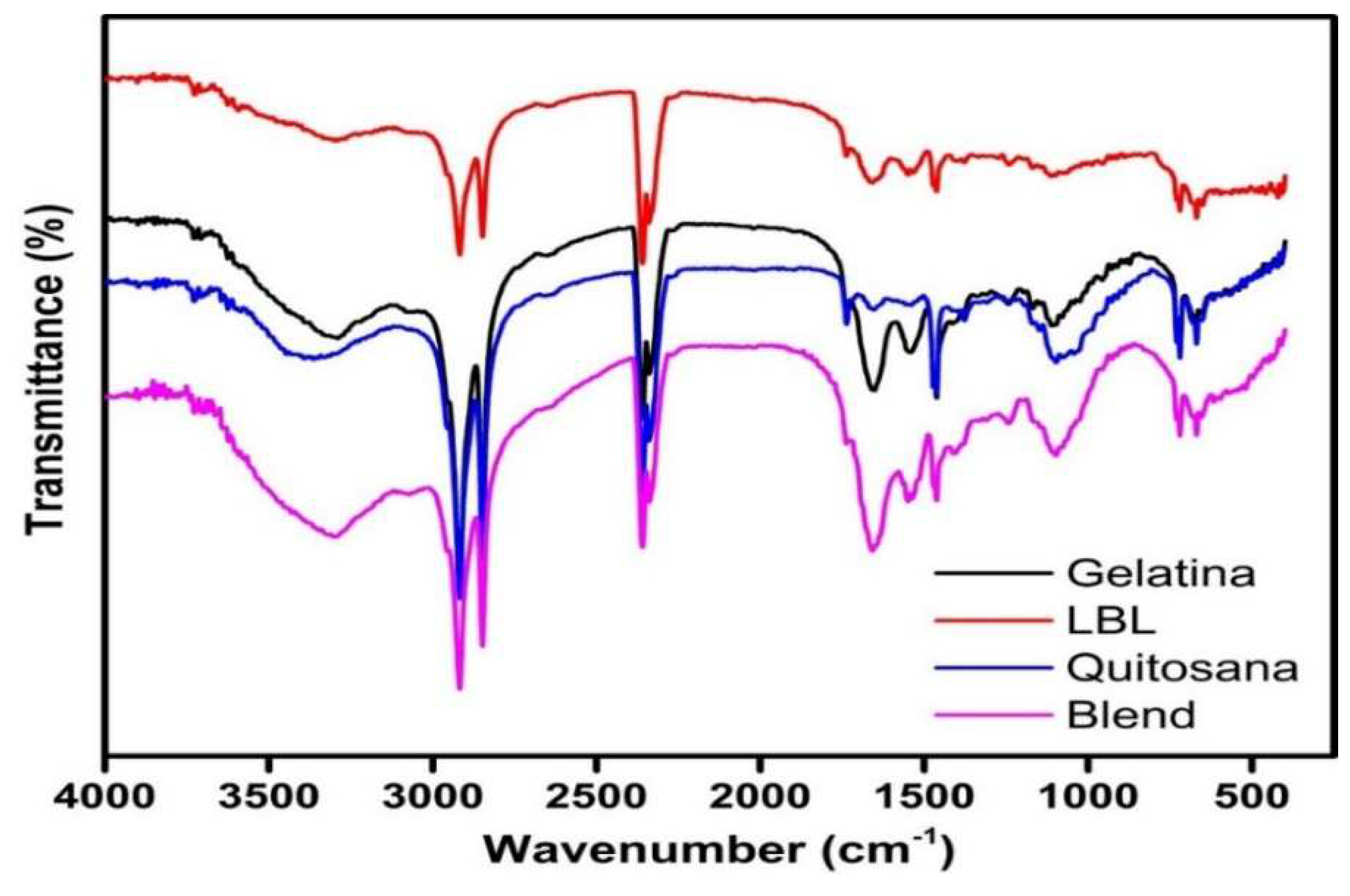

3.1. FTIR of gelatin and chitosan coatings and electron micrographs

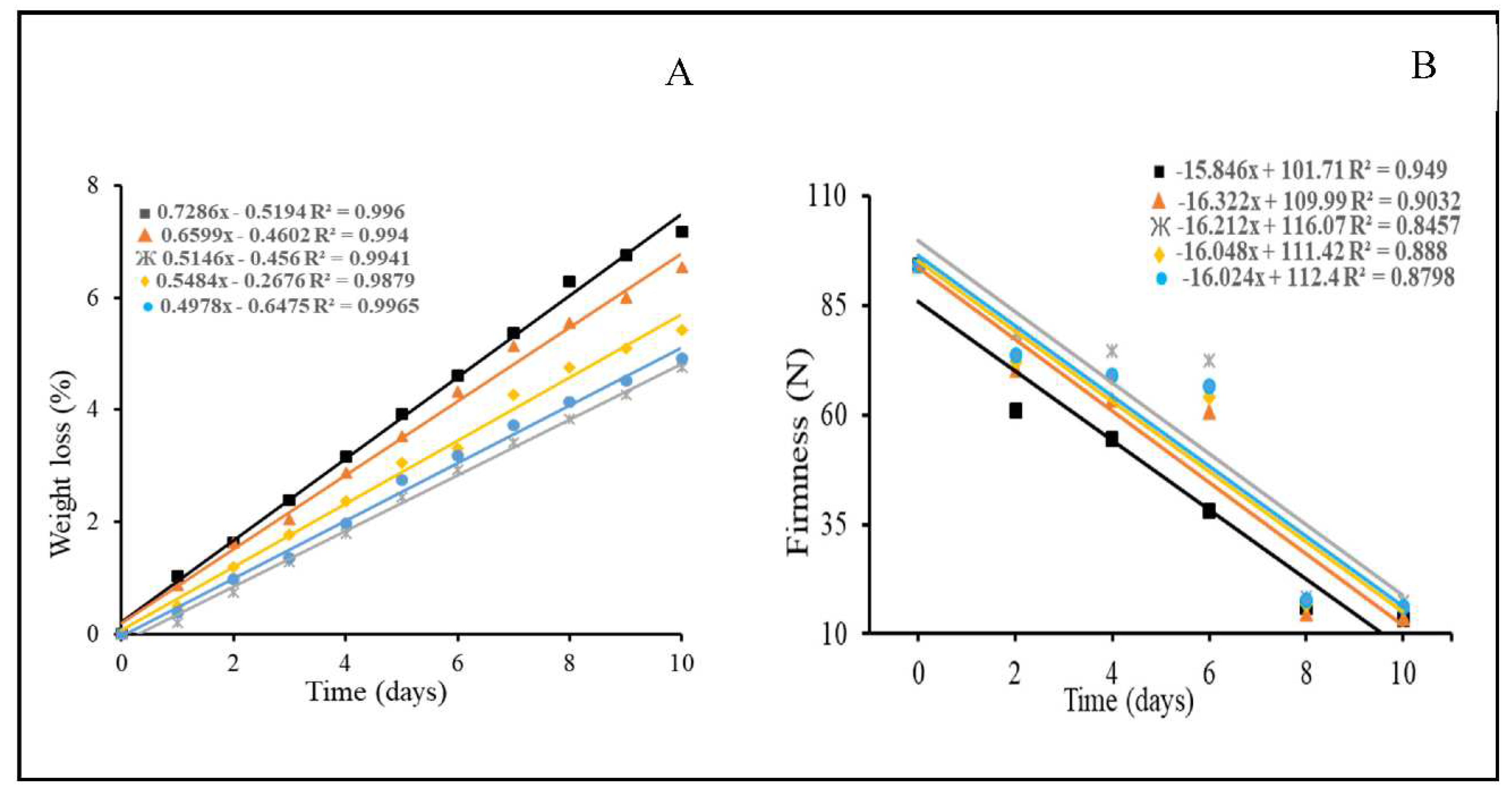

3.2. Loss of fresh mass and firmness

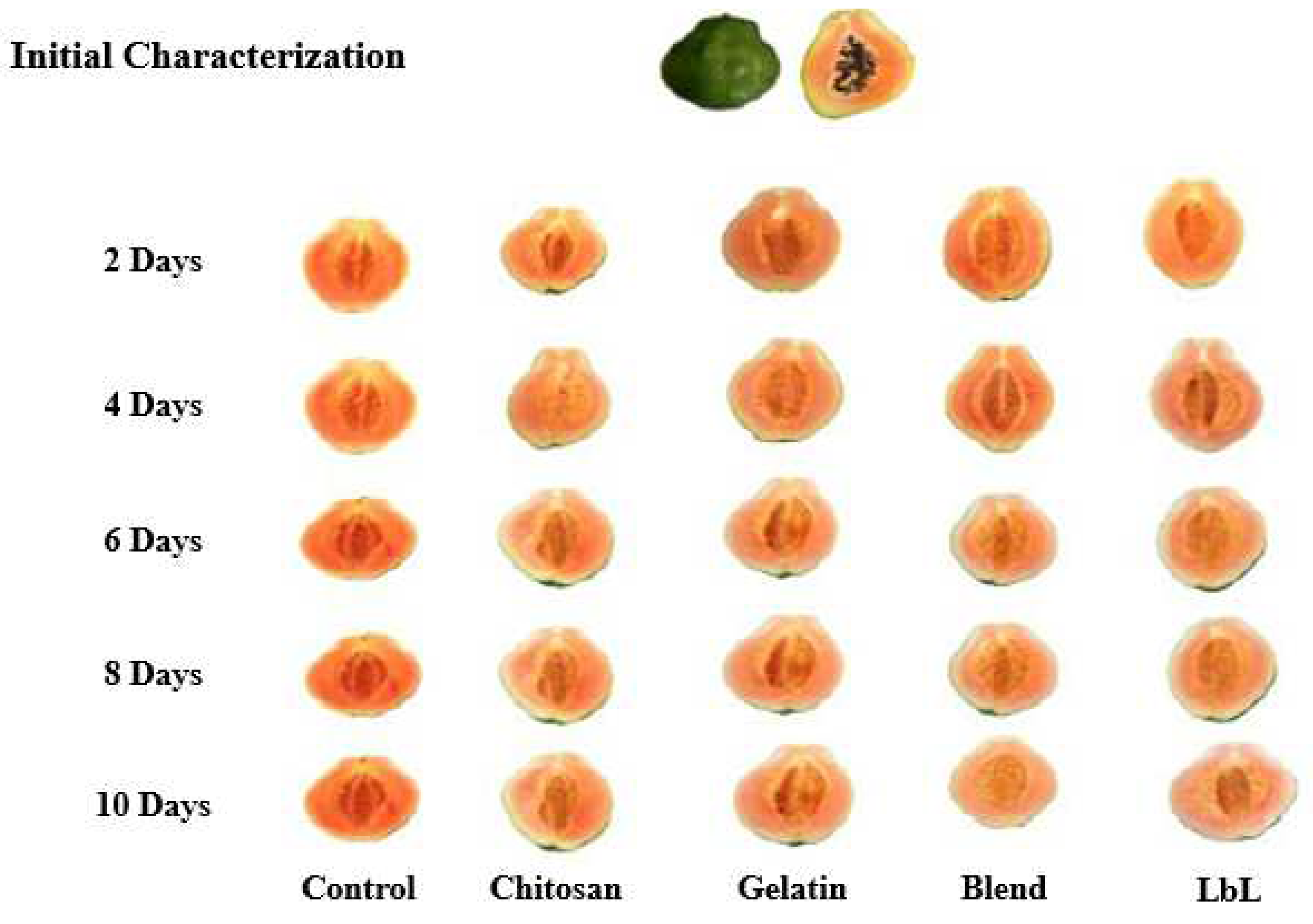

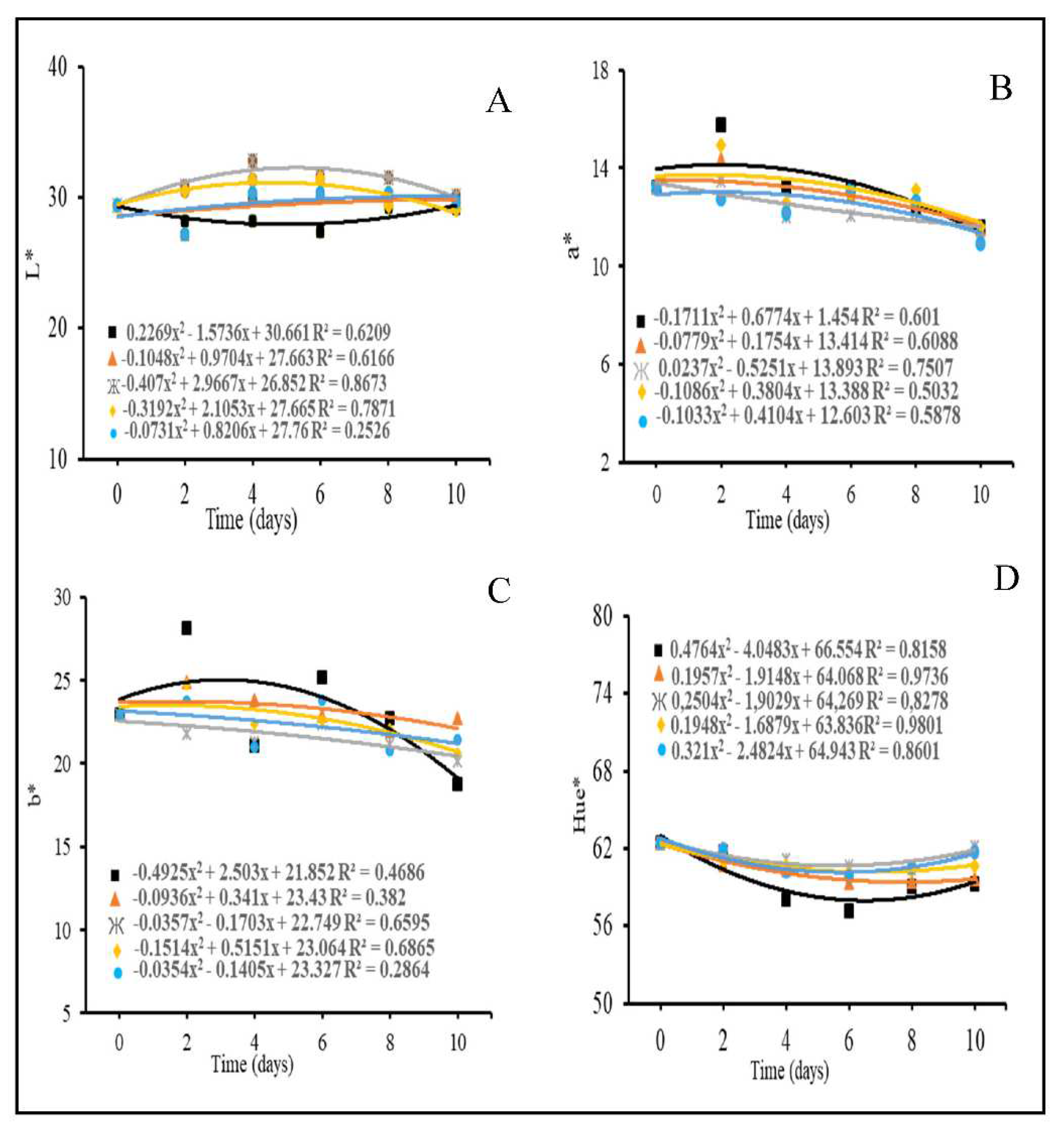

3.3. Pulp Color

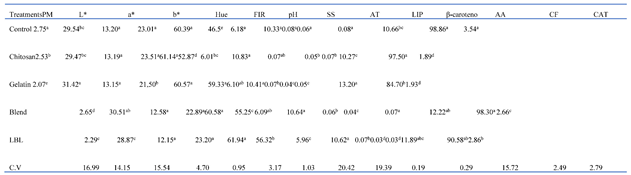

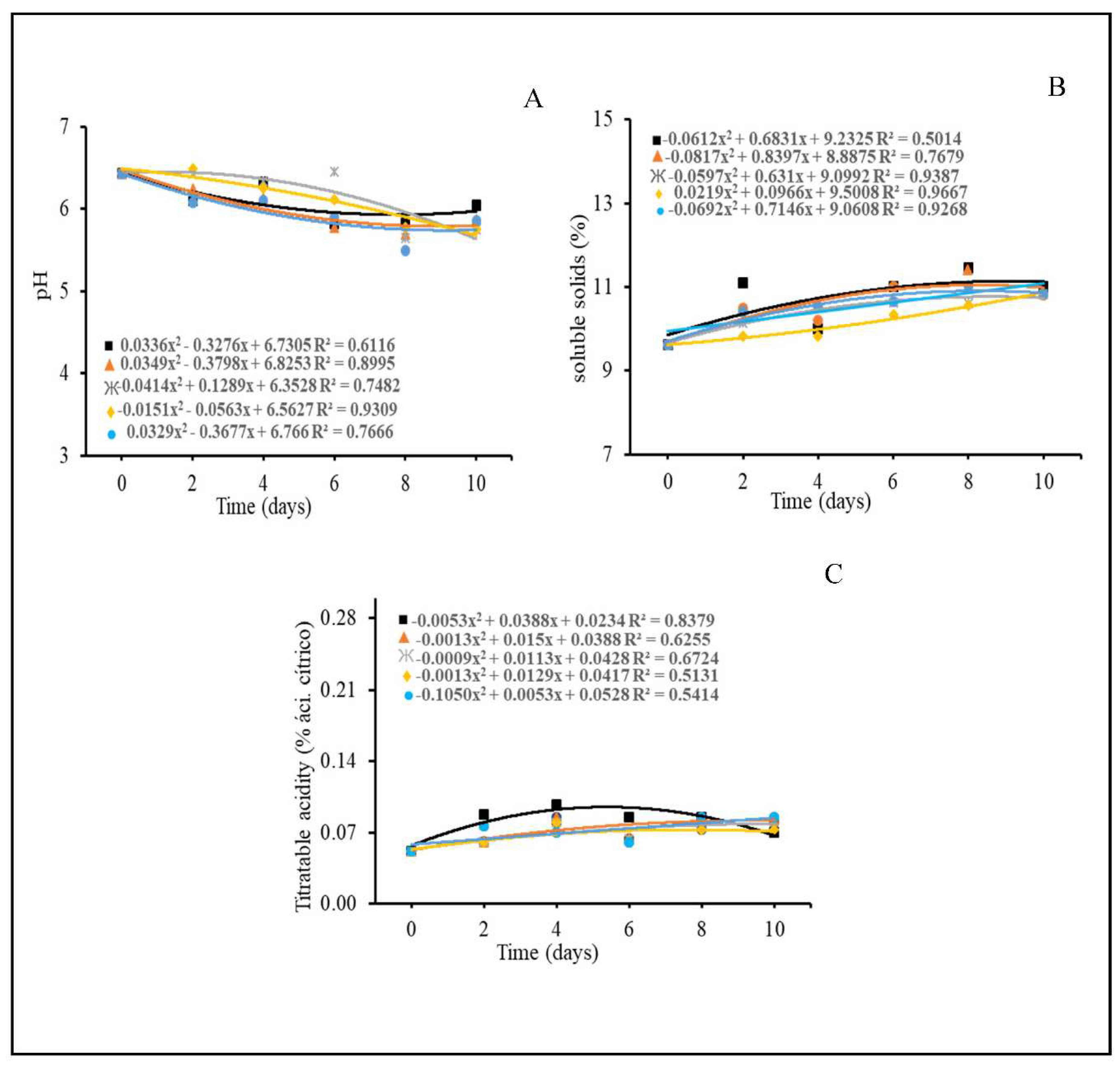

3.4. Physicochemical characteristics

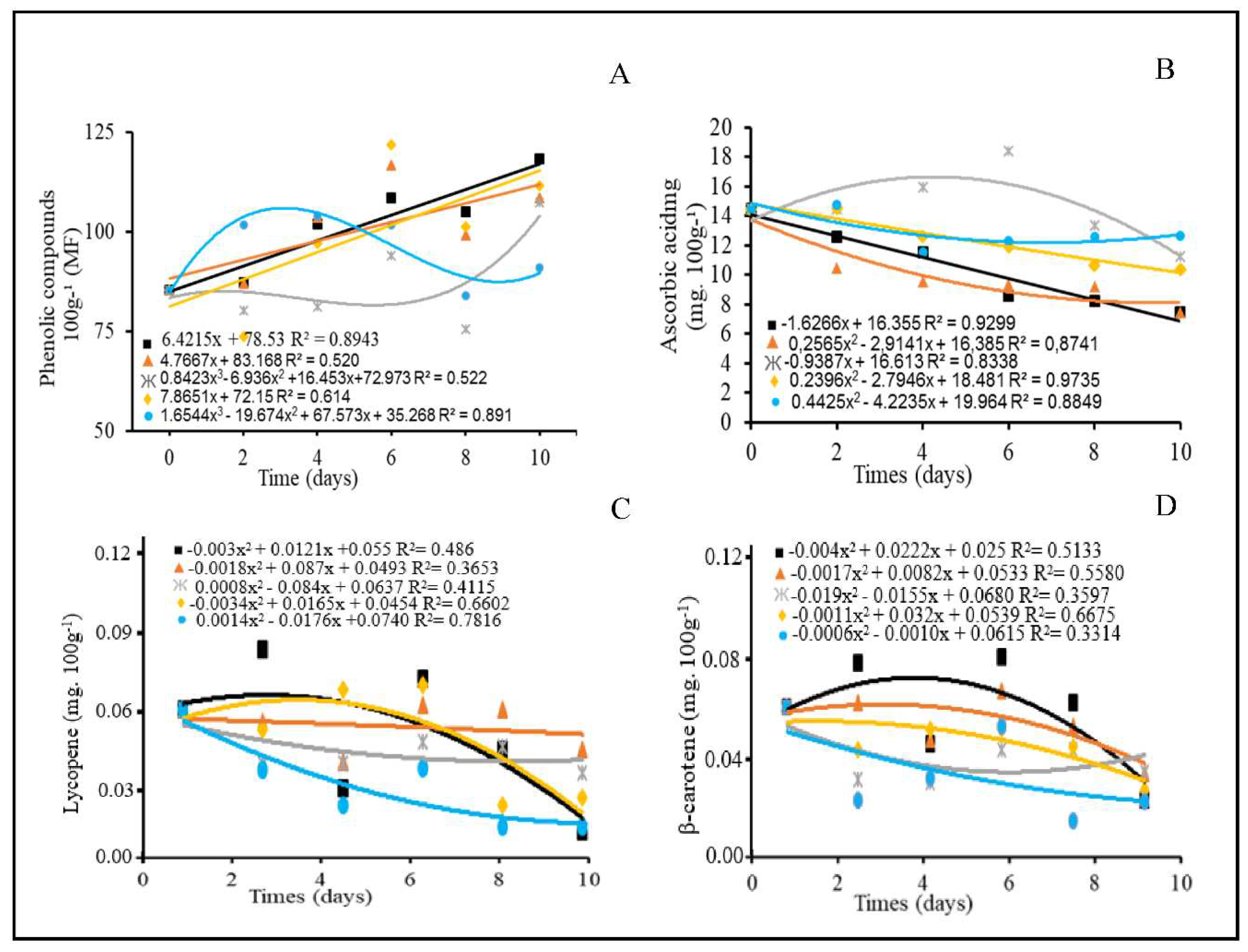

3.5. Contents of bioactive compounds and Pigment contents

3.6. Total sugar contents and catalase enzyme

3.7. Contents of macro and microminerals

4. Discussion

4.1. FTIR of gelatin and chitosan coatings

4.2. Loss of fresh mass and firmness

4.3. Pulp Color

4.4. Physicochemical characteristics

4.5. Contents of bioactive compounds

4.6. Total sugar contents and catalase enzyme

4.7. Contents of macro and microminerals

5. Conclusion

Credit authorship contribution statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

Appendix A

|

| FV | GL | PM | Fir | L* | a* | b* | Hue | pH | SS | AT | LIP | β-car | AA | CF | Cat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coating(R) | 4 | 0.2035ns | 0.00ns | 0.0ns | 2.42ns | 0.0ns | 0.0ns | 0.0ns | 1.05ns | 3.83** | 955.0** | 0.0ns | 7.19** | 0.0ns | 0.0ns |

| Time (T) | 5 | 37.46* | 3903.7** | 13.93** | 7.35** | 11.23** | 2.74* | 103.91** | 6.54** | 34.32** | 2053.9** | 2523.5** | 26.64** | 18.06** | 33835** |

| R x T | 20 | 0.2012ns | 5.5061** | 4.17** | 1.02ns | 2.90** | 0.73ns | 7.43** | 1.66ns | 3,19** | 807.66** | 853.45** | 1.12ns | 4.93** | 3396.2** |

| Residue | 57 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| CV (%) | - | 16.99 | 1.75 | 14.15 | 15.54 | 4.70 | 0.95 | 1.03 | 20.42 | 19.39 | 0.19 | 0.29 | 15.72 | 2.49 | 2.79 |

| FV | GL | Na | Mg | K | Mn | Fe | Cu |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coating (R) | 4 | 0.0ns | 0. 00ns | 0.0ns | 0.0ns | 0.0ns | 0.0ns |

| Time (T) | 5 | 36801** | 524061** | 1899483.071** | 3937.2** | 21314** | 388.72** |

| R x T | 20 | 703.28** | 7906.3** | 5347.5** | 754.06** | 520.32** | 67.602** |

| Residue | 57 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| CV (%) | - | 0.28 | 0.17 | 0.11 | 49.19 | 0.50 | 2.64 |

References

- Aktaruzzaman, M. D. , Afroz, T., Kim, B. S. Post-harvest anthracnose of papaya caused by Colletotrichumtruncatum in Korea, European Journal of Plant Pathology 2018, 150, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO (2018). Production of Papayas: top 10 producers. Available online: http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC/visualize (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- IBGE (2020). BrazilianInstitute of Geography and Statistics. Municipal AgriculturalProduction. Available online: http://sidra.ibge.gov.br/tabela/5457#resultado (accessed on 25 March 2023).

- Barros, T. F. S. , Rios, E.S. C., Maia, L. D. M., Dantas, R. L., Silva, S. M. Fruit quality of papaya cultivarssold in supermarkets in Campina Grande-PB. Revista Agropecuária Técnica 2018, 39, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewajulige, I. G. N. Dhekney, S. A. (2016). Papayas, 209-212.

- Cortez-vega, W. R. , Piotrowicz, I.B. B., Prentice, C., Borges, C. D. Conservation of minimally processed papaya usingediblecoatingsbasedonxanthangum. AgriculturalSciences 2014, 34, 1753–1764. [Google Scholar]

- Moretti, C. L. (2017). Minimal processing manual for fruits and vegetables. Available online: https://www.sisbin.ufop.br/novoportal/wpcontent/uploads/2015/03/Manual-de Processamento-Minimode-Frutas-e-Hortalicas.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- Kluge, R. A. , Geerdink, G.M., Tezotto-uliana, J. V., Guassi, S. A. D., Zorzeto, T. Q.; Sasaki, F. F. C., Mello, S. C. Quality of minimally processed yellow bell pepper treated with antioxidants. Semina: Agricultural Sciences 2014, 35, 801–812. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, E. N. A. , Santos, D. C. Technology and Processing of Fruits and Vegetables. Minimally processed fruits and vegetables 2015, 193-225. Christmas.

- Almino, H. A. , Santos, S.C. L. Effect of application of ediblecoatingsonminimally processed fruits and vegetables. BrazilianJournal of Environmental Management 2020, 14, 100–104. [Google Scholar]

- Atarés, L. , Chiralt, A. Essential oils as additives in biodegradable films andcoatings for active food packaging. Trends in Food Science and Technology 2016, 48, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhouri, F. M. , Martelli, S. M., Caon, T., Velasco, J. I., Mei, L. H. I. Edible films and coatings based on starch/gelatin: Film properties and effect of coatings on quality of refrigerated Red Crimson grapes. Postharvest Biology and Technology 2015, 109, 56-64. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, E.M. , Borges, C.D.,Formiga, A.S., Junior, J.S.P.,Mattiuz,B. Monteiro, S.S. Conservation of red guava ’Pedro Sato’ using chitosan and gelatin-based coatings produced by the layer-by-layer technique. Process Biochemistry 2022, 121, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q. I, Cao, Jun., Y. U, Huan., Zhang, Jiahui., Yuan, Y., Shen, X., Li, C. The effects of EGCG on the mechanical, bioactivities, cross-linking and release properties of gelatin film. Food Chemistry 2019, 271, 204-210.

- Galindo, M. V. Paglione, I. S., Coelho, A. R., Leimann, F. V., Shirai, M. A. (2020). Production of chitosan nanoparticles and application as a coating in blends of cassava starch and poly(lactic acid). Research, Society and Development, 9, 3-15.

- Freire, L. F. A. , Formiga, W. J. F., Lagden, M. G., Luna, A. S., Alves, F. L., Corrêa, M. A., Santos, M. A. G. Evaluation of TextileEffluentAdsorptionby Chitosan Composites. Revista Processos Químicos 2018, 12, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnon-Rips, H. , Poverenov, E. Improving food products' quality and storability by using Layer - by Layer edible coatings. Trends in food science & technology 2018, 75, 81-92. [CrossRef]

- Hammond, P. T. Building biomedical materials layer-by-layer. MaterialsToday 2012, 15, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J. J. , Bjoernmalm, M., Caruso, F. (2015). Technology-driven layer-by-layer assembly of nanofilms, Science,6233.

- De Paoli, M. A. Degradation and Stabilization of polymers. 2nd revised online version. Ed. Chemkeys 2008, 1, 2–10. [Google Scholar]

- Araújo, E. M. , Hage J. R, E., Carvalho, A. J. F. (2003). Compatibility of Polyamide 6/ABS Blends using MMAGMA and MMA-MA Reactive Acrylic Copolymers. Part 1: rheologicalbehavior and mechanicalproperties of blends.

- Khan, I. , Chohan, M. M., Mazumder, M. A. J. (2018). PolymerBlends. In: JafarYoshida, C. M. P., Oliveira, E. N., Jr., Franco, T. T. Chitosan tailor-made films: the effects of additives on barrier and mechanical properties. Packing Technology and Science 2009, 22, 161-170.

- Barbosa, J. C. , Maldonado Júnior, W. (2015). AgroEstat: System for statistical analysis of agronomic tests. Jaboticabal: GráficaMultipress LTDA. Available online: https://www.agroestat.com.br.

- Zenebon, O. , Pascuet, N.S., Tiglea, P., (2008). Physical-chemical methods for food analysis, fourth ed.Instituto Adolfo Lutz (IAL), São Paulo.

- Instituto Adolfo Lutz. (2008). Physical-chemical methods for food analysis. São Paulo – SP, Instituto Adolfo Lutz, 1020.

- Pearson, D. (1976). Laboratory techniques for food analysis. Zaragoza, Spain.

- Nagasaki, M e I.Yamashita. Simple method for simultaneous determination of chlorophyll and carotenoids in tomato fruit. NipponShokuhinKogyoGakkaishi 1992, 39, 925–928.

- Waterhouse, A. Folinciocalteau micro method for total phenol in wine. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture 2006, 3 – 5.

- Yemm, E. W. , Willis, A.J. The estimation of carbohydrates in plant extracts by anthrone. BiochemicalJournal 1954, 57, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boaretto, L. F. , Carvalho, G., Borgo, L., Creste, S., Landell, M. G. A., Mazzafera, P., Azevedo, R. A. Water stress reveals differential antioxidant responses of tolerant and non-tolerant sugarcane genotypes. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2014, 74, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford M., M. Rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 71, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cia, M.C. , Guimarães A. C. R., Medici L. O., Chabregas S. M., Azevedo R. A. Antioxidant response to water deficit by drought-tolerant and -sensitive sugarcane varieties. Ann. Ap. Biol. 2012, 161, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abugoch, L. E. , Tapia, C., Villaman, M. C., Yazdani-Pedram, M., Diaz-Dosque, M. Characterization of quinoa proteinchitosan blend edible films. Food Hydrocolloids 2011, 25, 879–886.

- Lima, C. G. A. , De Oliveira, R. S., Figueiro, S. D., Wehmann, C. F., Goes,J. C., & Sombra, A. S. B. DC conductivity and dielectricpermittivity of collagen-chitosan films. Materials Chemistry and Physics 2006, 99, 284–288. [CrossRef]

- Gennadios, A. (2002). Soft gelatin capsules. In A. Gennadios (Ed.), Protein-based films and coatings, 1, 1-41.

- Pranoto, Y. , Lee, C. M., Park, H. J. Characterizations of fish gelatin films added with gellan and κ-carrageenan. LWT- Food Science and Technology 2007, 40, 766–774.

- Poverenov, E. , Rutenberg, R. Danino, S., Horev, B., Rodov, V. (2014). Gelatin-chitosan composite films and edible coatings to enhance the quality of food products: Layer-by-layer vs. Blended formulations. Food and Bioprocess Technology 2014, 7, 3319–3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitarra, M. I. F. Chitarra, A. B. (2005). Postharvest of fruits and vegetables: physiology and handling. 2.ed. Mines: UFLA.

- Kumar, P. , Sethi, S., Sharma, R. R., Srivastav, M., Varghese, E. Effect of chitosan coating on postharvest life and quality of plum during storage at low temperature. ScientiaHorticulturae 2017 v. 226, n. 13, p. 104–109.

- Fagundes, C. , Palou, L., Monteiro, A. R., Pérez-gago, M. B. Hydroxypropyl methylcellulose-beeswax edible coatings formulated with antifungal food additives to reduce alternaria black spot and maintain postharvest quality of coldstored cherry tomatoes. ScientiaHorticulturae 2015, 193, 249-257.

- Brackmann, A. , Anese, R.O., Both V., Thewes, F. R., Fronza, D. Controlled atmosphere for the storage of guava cultivar “Paluma”. Ceres Magazine 2012, 59, 151–156. [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda, L. M. F. 2013. Evaluation of chitosan and cassava starch, applied post-harvest in the coating of apples. Thesis (Doctorate in Fitotecnia) - Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre.

- Brasil, I. M. , Gomes, C., Puerta-Gomez, A., Castell-Perez, M. E., Moreira, R. G. Polysaccharide-based multilayered antimicrobial edible coating enhances quality of fresh-cut papaya. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2012, 47, 39-45.

- Lima, A. S. , Ramos, A.L. D., Marcellini, P. S., Batista, R. A., Faraoni, A. S. Addition of Anti-Browning and Antimicrobial Agents and Use of Different Plastic Films in Minimally Processed Papaya. Revista Brasileira de Fruticultura 2005, 27, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argoñosa, A. C. S. , Rapos, O, M. F. J., Teixeira, P., Morais, A. M. (2008) Effect of cuttype on quality of minimally processed papaya. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2008, 88, 2050–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, J. D. R. , Souza, D.S., Oliveira, T. V., Oliveira, M. C., Bastos, V. S., Castro, A. A. Study of conservation of papaya in Hawaii using edible skins at different temperatures. Scientia Plena 2011, 7, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigo, J. M. , Albertini, S., Spoto, M. H. F., Sarmento, S. B. S., Lai Reyes, A. E., Sarriés, G. A. Effect of ediblecoatingson the conservation of minimally processed papayas. BrazilianJournal of Food Technology 2012, 15, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, G. FoodChemicalCompositionTable. 9 ed. São Paulo: Atheneu, 1999. p. 53-58.

- Martiñon, M. E. , Moreira, R. G., Castell-Perez, M. E., Gomes, C. Development of a multilayered antimicrobial edible coating for shelf life extension of fresh-cut cantaloupe (Cucumismelo L.) stored at 4 °C. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2014, 55, 341–350.

- Huber, L. S. , Rodriguez-Amaya, D. B. (2008).Flavonols and flavones: Braziliansources and factorsthatinfluencefoodcomposition. Food and NutritionAraraquara, 19.

- Besinela Junior, E. , Monarim, M.M. S., Camargo, M., Mahl, C. R. A., Simões, M. R.,Silva, C. F. Effect of differentbiopolymersonminimally processed papaya (Carica papaya L.) coating. Revista Varia Scientia Agrárias 2010, 01, 131–142. [Google Scholar]

- Ayón-Reyna, L. E., Tamayo-Limón, R., Cárdenas-Torres, F., López-López, M. E.,López-Angulo,G.,López-Moreno,H. S.,López-Cervántes,J.,López-Valenzuela,J. A.&Vega-Garcia, M. O. EffectivenessofHydrothermal-CalciumChlorideTreatmentandChitosanon QualityRetentionandMicrobialGrowthduringStorageofFresh-CutPapaya.JournalofFood Science 2015, 80, 594–601. [CrossRef]

- Germano, T. A. (2016). Effects of edible coating based on galactomannan and carnauba wax on the quality and antioxidant metabolism of guavas. Thesis (Master's degree). Federal University of Ceará, Fortaleza, CE, Brazil.

- Boonkorn, P. Impact of hot water soaking on antioxidant enzyme activities and some qualities of storage tomato fruits. International Food Research Journal 2016, 23, 934–938. [Google Scholar]

- Malavolta, E. Plant mineral nutrition manual Piracicaba: Ceres, 2006. 638p.

- Epstein, E. , Bloom, A. J. Mineral nutrition of plants: principles and perspectives. London: Ed. Plant, 2006. 401p.

| Treatments | |||||

| Minerals (mg.kg-1) | Control | Chitosan | Gelatin | BLEND | LBL |

| Na | 558.34b | 522.57b | 559.17a | 394.11d | 505.88d |

| Mg | 843.23c | 949.14c | 982.22a | 633.98d | 956.15b |

| K | 5721.0d | 4958.7e | 7579.6a | 6509.1b | 6197.8c |

| Mn | 0.93c | 0.86d | 1.02b | 1.06a | 1.02b |

| Fe | 24.13b | 21.92d | 25.57a | 19.33e | 21.99c |

| Cu | 5.602b | 5.39c | 5.80a | 5.72ab | 5.23d |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).