Submitted:

12 May 2023

Posted:

12 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

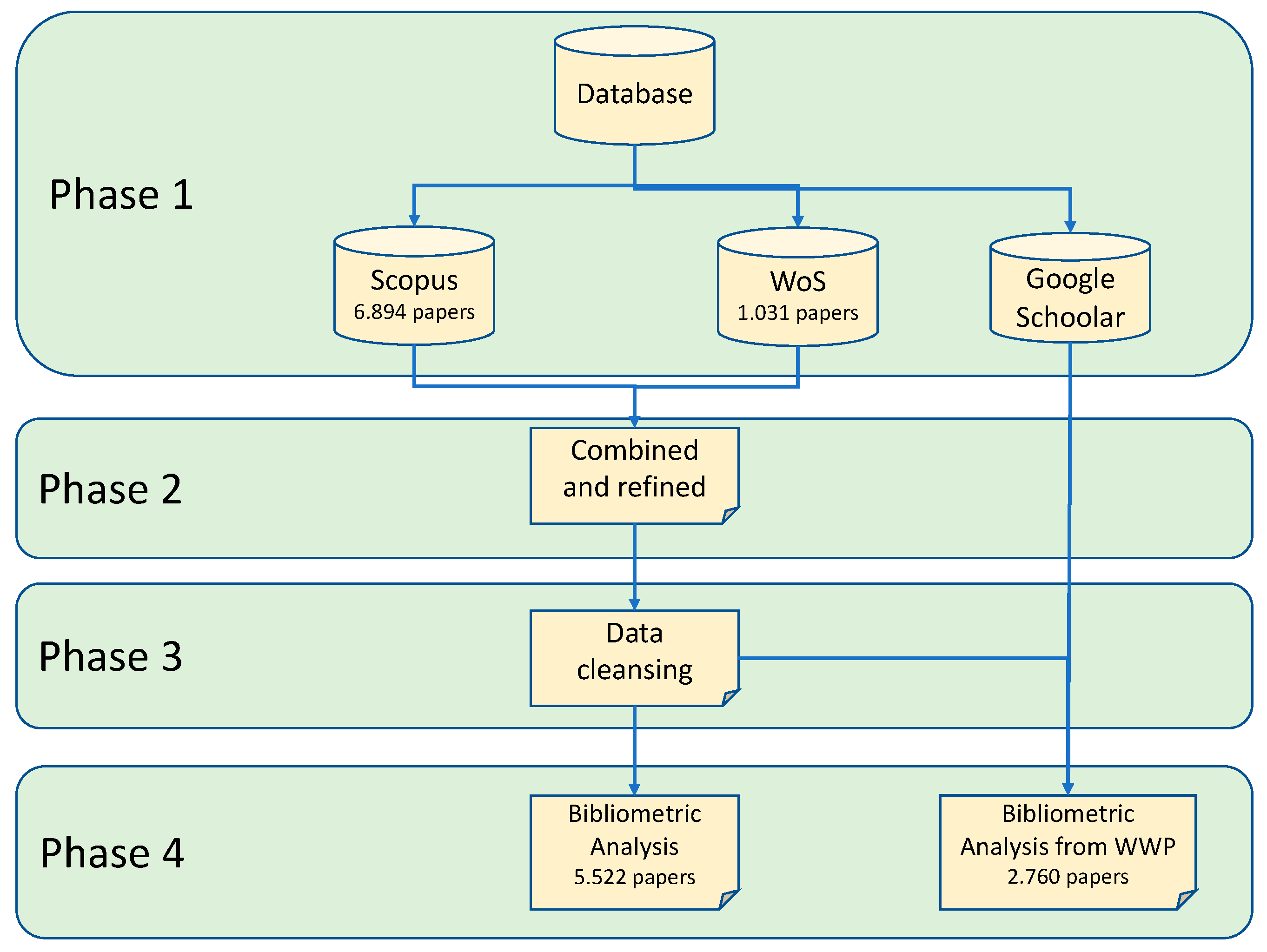

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results of the bibliometric analysis

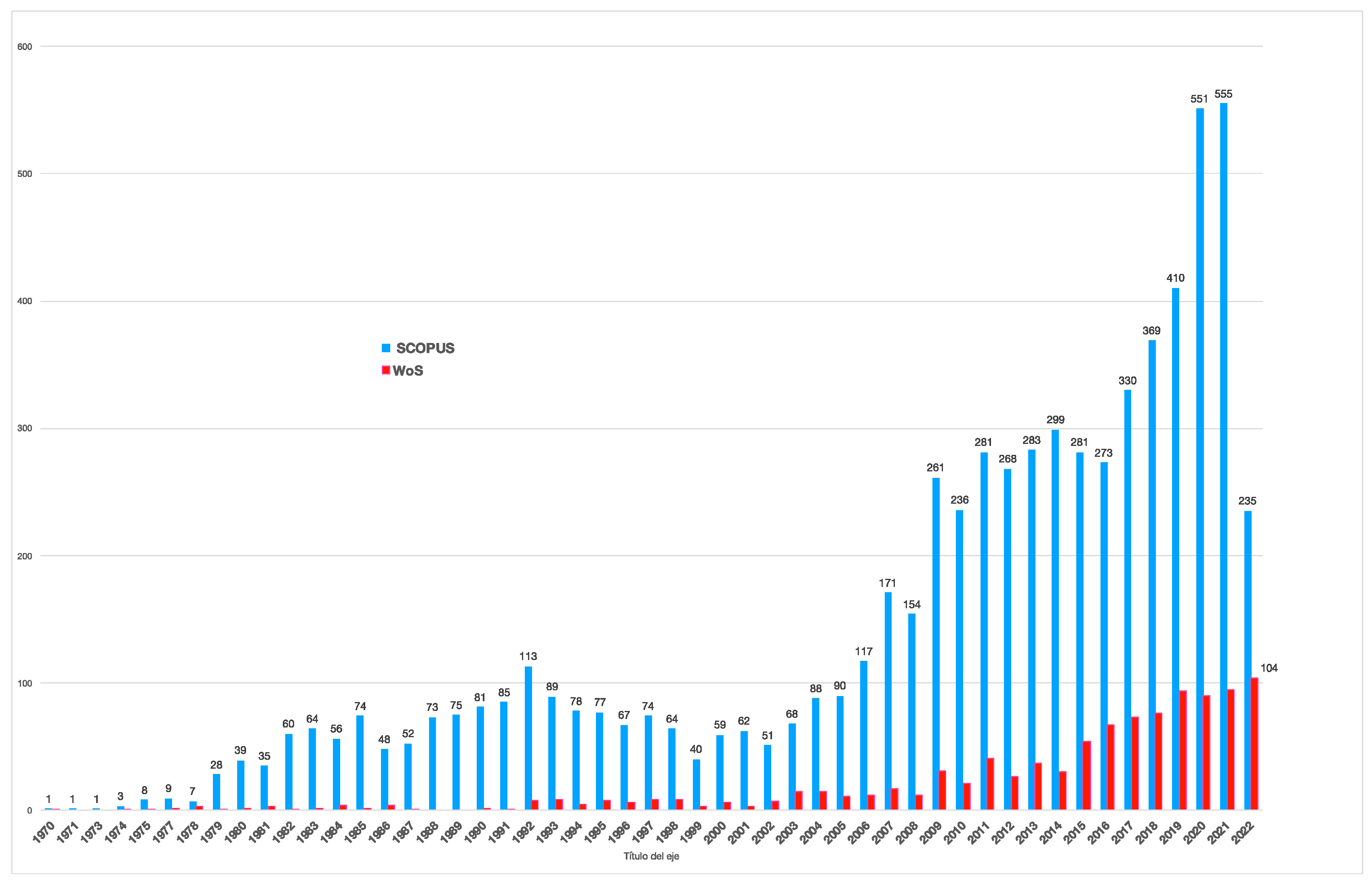

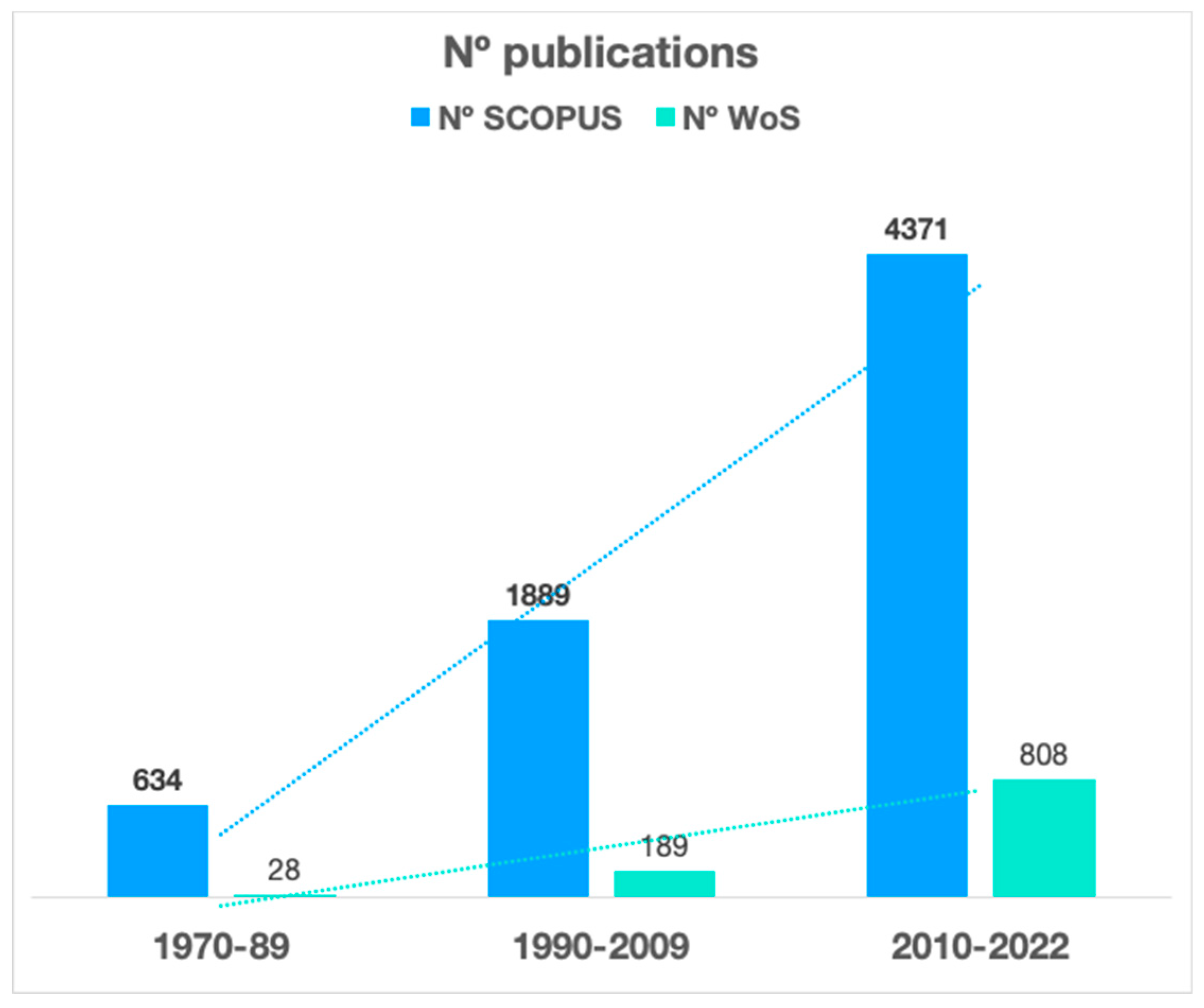

3.1. General indicators for activity and scientific publications

| Document type | TP1 | % TP | TC1 | % TC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Article | 4645 | 68,45% | 78190 | 83,49% |

| Book | 16 | 0,24% | 2250 | 2,40% |

| Book Chapter | 70 | 1,03% | 174 | 0,19% |

| Conference Paper | 1813 | 26,70% | 4517 | 4,82% |

| Review | 242 | 3,57% | 8516 | 9,09% |

| Total, general | 6786 | 100,00% | 93647 | 100,00% |

3.2. Analysis of influential authors by periods

3.2.1. First period 1970-89: introduction and the first influential authors

3.2.2. Second period 1990-2009: transition based on the human dimension.

3.2.3. Third period 2010-2022: maturity and new approaches.

| Authors | Title | Year | Source title | Cited by |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shucksmith, M. | Disintegrated rural development? Neo-endogenous rural development, planning and place-shaping in diffused power contexts | 2010 | Sociologia Ruralis | 241 |

| Li, Y., Westlund, H., Liu, Y. | Why some rural areas decline while some others not: An overview of rural evolution in the world | 2019 | Journal of Rural Studies | 235 |

| Neumeier, S. | Social innovation in rural development: identifying the key factors of success | 2017 | Geographical Journal | 149 |

| Long, H., Tu, S. | Rural restructuring: Theory, approach and research prospect | 2017 | Acta Geographica | 89 |

| Cazorla, A., de los Ríos, I., Salvo, M. | Working With People (WWP) in rural development projects: A proposal from social learning | 2013 | Cuadernos de Desarrollo Rural | 41 |

| Ryser, L., Halseth, G. | Rural economic development: A review of the literature from industrialized economies | 2010 | Geography Compass | 37 |

| Frank, K.I., Reiss, S.A. | The Rural Planning Perspective at an Opportune Time | 2014 | Journal of Planning Literature | 25 |

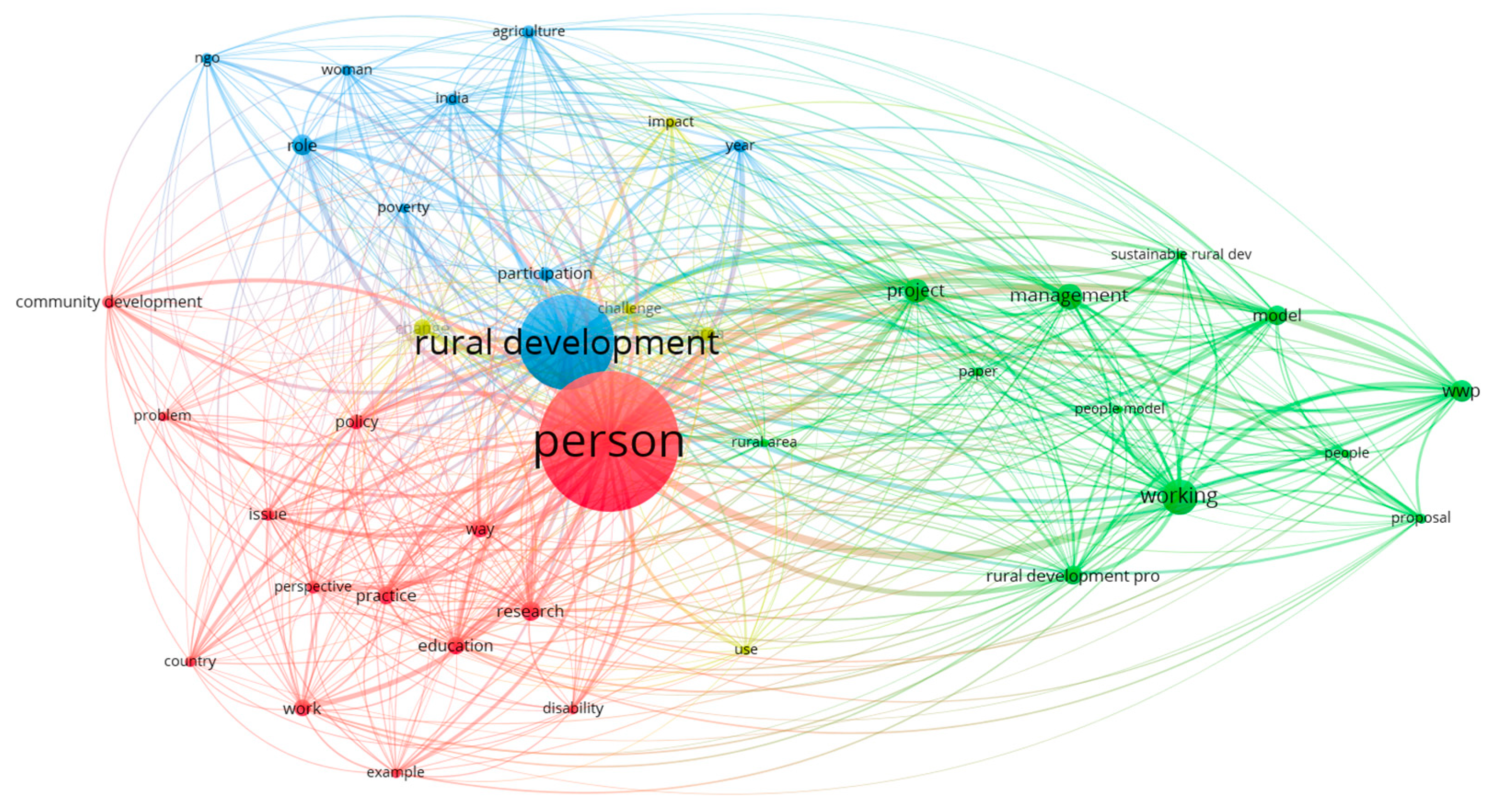

3.3. Analysis of the co-occurence of keywords and clustering

3.4. “From Putting the Last first” to “Working with People” in Rural Development research

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Taylor, P.J. The error of developmentalism in human geography» in Horizons in Human Geography (Gregory, D. y Walford, R., eds.). Londres, Macmillan, 1989, 303-319.

- Pike, A.; Rodríguez-Pose, A. Y Tomaney, J. What Kind of Local and Regional Development and for Whom? Regional Studies 2007, 41, 1253–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdoch, J.; Pratt, A. Rural studies: modernism, postmodernism and the "post rural". Journal of Rural Studies 1993, 9, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philo, C. Postmodern rural geography? A reply to Murdoch and Pratt. Journal of Rural Studies 1993, 9, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazorla, A.; De los Ríos, I.; Salvo, M. Working with People (WWP) in Rural Development Projects: A Proposal from Social Learning. Cuad. Desarro. Rural 2013, 10, 131–157. [Google Scholar]

- Aguillo, I.; Bar-Ilan, J.; Levene, M.; Ortega, J. Comparing university rankings. Scientometrics 2010, 85, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguillo, I.F. Is Google Scholar useful for bibliometrics? A webometric analysis. Scientometrics 2012, 91, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harzing, A.W.; and Alakangas, S. Google Scholar, Scopus and the Web of Science: a longitudinal and cross-disciplinary comparison. Scientometrics 2016, 106, 787–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas-Bleda, A.; Thelwall, M.; Kousha, K.; Aguillo, I.F. Do highly cited researchers successfully use the social web? Scientometrics 2014, 101, 337–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Martín, A.; Orduna-Malea, E.; Thelwall, M.; López-Cózar, E.D. Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus: A systematic comparison of citations in 252 subject categories. Journal of informetrics 2018, 12, 1160–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harzing, A.W. K.; van der Wal, R. Google Scholar as a new source for citation analysis. Ethics in Science and Environmental Politics 2008, 8, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prins, Ad A. M.; Costas, R., van Leeuwen, Thed N., Eds.; Wouters, P.F. Using Google Scholar in research evaluation of humanities and social science programs: A comparison with Web of Science data, Research Evaluation 2016; Volume 25, Issue 3, July, Pages 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikki, S. Comparing Google Scholar and ISI Web of Science for earth sciences. Scientometrics 2009, 82, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harzing, A.W. (2007). Publish or Perish Retrieved from. http://www.harzing.com/pop.htm.

- Garcia-Lillo, F.; Claver-Cortés, E.; Marco-Lajara, B.; Úbeda-García, M. Mapping the Intellectual Structure of Research on ‘Born Global’ Firms and INVs: A Citation/Co-citation Analysis. Manag Int Rev 2017, 5, 631–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W.M. How to Conduct a Bibliometric Analysis: An Overview and Guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effendi, D.N.; Irwandani; Anggraini, W. ; Jatmiko, A.; Rahmayanti, H.; Ichsan, I.Z.; Rahman, M.M. Bibliometric Analysis of Scientific Literacy Using VOS Viewer: Analysis of Science Education. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1796, 012096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merigo, J.M. & Yang, J.B. Accounting research: A bibliometric analysis. Australian Accounting Review 2017, 27, 71–100. [Google Scholar]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. 2014. Visualizing bibliometric networks. Measuring scholarly impact (pp.285– 320). Cham: Springer. [CrossRef]

- Morss, E.R. Implementing rural development projects: Lessons from AID and World Bank Experiences. Routledge. 2019.

- Friedmann, J. and Alonso, W. Regional Policy: Readings in Theory and Applications; M.I.T. Press: Cambridge, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann, J. Planning as Social Learning; Institute of Urban and Regional Development: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1981; Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0q47v754 (accessed on 3 February 2018).

- Musto, S. Search of a new paradigm. En S. (. Musto,. In Endogenous Development: A Myth or a Path? (págs. 5-18). Berlin: EADI Books. 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Haan, H.; Van Der Ploeg, J. Endogenous Regional Development in Europe: Theory, Method and Practice. Brussels: European Commission.

- Stöhr, W.; Taylor, D.R. F. (1981). Development from above or below? The dialectics of regional planning in developing countries.

- Leupolt, M. Integrated rural development: key elements of an integrated rural development strategy. Sociologia ruralis 1977, 17, 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, I. On the concept of ‘integrated rural development planning’in less developed countries. Journal of Agricultural economics 1979, 30, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruttan, V.W. Integrated rural development programs: a skeptical perspective. International Development Review 1975, 17, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, K. Policy options for rural development. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 1973, 35, 239–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, L.J. Non-monetary capital formation and rural development. World Development 1975, 3, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, G. Logical framework approach to the monitoring and evaluation of agricultural and rural development projects. Project Appraisal 1987, 2, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyanwu, C.N. The technique of participatory research in community development. Community Development Journal 1988, 23, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hague, W. (1975) Towards a Theory of Rural Development. UN Asian Development Institute.

- Hulme, D. Learning and not learning from experience in rural project planning. Public Administration and Development 1989, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morss, E.R.; Gow, D.D. Implementing Rural Development Projects: Lessons from AID and World Bank Experiences, Boulder. 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Hulme, D. Projects, politics and professionals: alternative approaches for project identification and project planning. Agricultural Systems 1995, 47, 211–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, R. In Search of Professionalism, Bureaucracy and Sustainable Livelihoods for the 21st Century’, IDS Bulletin 1991, 22.4: 5–11. [CrossRef]

- Chambers, R.; and Conway, G. Sustainable rural livelihoods: practical concepts for the 21st century. Institute of Development Studies (UK). 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, R. The Self-Deceiving State, IDS Bulletin 1992, 23.4: 31–42. [CrossRef]

- Chambers, R. All Power Deceives, IDS Bulletin 1994, 25.2: 14–26. [CrossRef]

- Chambers, R. Participatory rural appraisal (PRA): Challenges, potentials and paradigm. World development 1994, 22, 1437–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, R. Putting the first last. Rugby: Intermediate Technology Publications. 1997.

- Scoones, I.; and Thompson, J. Beyond farmer first: rural people's knowledge, agricultural research and extension practice. Intermediate Technology Publications. 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Scoones, I. Livelihoods perspectives and rural development. The journal of peasant studies 2009, 36, 171–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernea, M.M. Putting people first: sociological variables in rural development. No. BOOK. Oxford University Press. USA. 1991.

- Cernea, Michael M. The sociologist's approach to sustainable development. Finance and development 1993, 30, 11–13.

- Ramos, A. ¿Por qué la conservación de la naturaleza? Discurso leído en el acto de recepción de la Real Academia de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales, Madrid. 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Burkey, S. People first: a guide to self-reliant participatory rural development. 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch, J. Networks - A new paradigm of rural development. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann, J. Toward and Non-Euclidean Mode of Planning. Journal of American Planning Association”, 482, Chicago. 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Pretty, J. Towards a learning paradigm: new professionalism and institutions for a sustainable agriculture. Beyond Farmer First: Rural people's knowledge, agricultural research and extension practice. 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Pretty, J.N.; Guijt, I.; Thompson, J.; Scoones, I. (1995). Participatory learning and action–A trainers guide.

- Leeuwis, C. 2000. T: Reconceptualizing participation for sustainable rural Development: Towards a negotiation approach.

- Cazorla, A. (Ed.) Planning Experiences in Latin America and Europe. Colegio de Postgraduados: Texcoco, México, 2015.

- Cazorla, A.; De los Ríos, I.; Díaz-Puente, J. The LEADER community initiative as rural development model: Application in the capital region of Spain. Agrociencia 2005, 39, 697–708. [Google Scholar]

- Barke, M.; and Newton, M. The EU LEADER initiative and endogenous rural development: the application of the programme in two rural areas of Andalusia, southern Spain." Journal of rural studies 1997, 13.3: 319-341.

- Bruckmeier, K. LEADER in Germany and the discourse of autonomous regional development. Sociologia ruralis 2000, 40, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- High, C.; Nemes, G. Social learning in LEADER: Exogenous, endogenous and hybrid evaluation in rural development. Sociologia ruralis 2007, 47, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, R.V.V. Rural development within the EU LEADER+ programme: new tools and technologies. AI & society, 2009; 23, 575–602. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, C. Towards a meta-framework of endogenous development: repertoires, paths, democracy and rights. Sociologia ruralis 1999, 39, 522–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, F.; Biggs, S. Evolving themes in rural development 1950s-2000s. Development policy review 2001, 19, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renting, H.; Rossing, W.A.; Groot, J.C.; Van der Ploeg, J.D.; Laurent, C.; Perraud, D. Exploring multifunctional agriculture. A review of conceptual approaches and prospects for an integrative transitional framework. Journal of environmental management 2009, 90, S112–S123. [Google Scholar]

- Cazorla, A.; De los Ríos, I.; Díaz-Puente, J. The LEADER community initiative as rural development model: Application in the capital region of Spain. Agrociencia 2005, 39, 697–708. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Puente, J.M.; Cazorla, A.; De Los Ríos, I. Empowering communities through evaluation: Some lessons from rural Spain. Community Dev. J. 2009, 44, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boswell, M. ; and Ivonne Audirac. Rural sustainable development: A new regionalism." Rural Sustainable Development in America 1997, 271. [Google Scholar]

- Marsden, T.; Bristow, G. Progressing integrated rural development: a framework for assessing the integrative potential of sectoral policies. Regional Studies 2000, 34, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, M. Planning Through Dialogue for Rural Development: The European Citizens' Panel Initiative. Planning, Practice & Research 2008, 23, 265–279. [Google Scholar]

- Cazorla, A. (Ed.) Planning Experiences in Latin America and Europe. Colegio de Postgraduados: Texcoco, México, 2015.

- Cazorla, A.; De los Ríos, I. Rural Community Management in the Global Economy: A planning model based on innovation and Entrepreneurial Activity. In Rural Communities in the Global Economy: Beyond the Classical Rural Economy Paradigms; Nicolae, I., De los Ríos, I., Vasile, A., Eds.; Eds.; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Shucksmith, M. Disintegrated rural development? Neo-endogenous rural development, planning and place-shaping in diffused power contexts. Sociologia ruralis 2010, 50, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De los Ríos, I.; Díaz-Puente, J.; Cadena-Iñiguez, J. The Initiative LEADER as a model for rural development: Implementation to some territories of México. Agrociencia 2011, 45, 609–624. [Google Scholar]

- De los Ríos, I.; Cadena, J.; Díaz, J.M. Creating local action groups for rural development in México: Methodological approach and lessons learned. Agrociencia 2011, 45, 815–829. [Google Scholar]

- Stratta, R.; De los Ríos, I. Developing Competencies for Rural Development Project Management through Local Action Groups: The Punta Indio (Argentina) Experience. In International Development; Appiah-Opoku, S., Ed.; InTech: London, UK, 2017; Chapter 8, pp. 153–172. [Google Scholar]

- Šūmanea, S.; Kunda, I.; Knickel, K.; De los Rios, I.; Rivera, M. Local and farmers’ knowledge matters! How integrating informal and formal knowledge enhances sustainable and resilient agriculture. J. Rural Stud. 2018, 59, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Westlund, H.; Liu, Y. Why some rural areas decline while some others not: An overview of rural evolution in the world. Journal of Rural Studies 2019, 68, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumeier, S. Social innovation in rural development: identifying the key factors of success. The geographical journal 2017, 183, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazorla-Montero, A.; de los Ríos-Carmenado, I.; Pasten, J. Sustainable development planning: master’s based on a project-based learning approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazorla, A.; De los Ríos, I.; Díaz-Puente, J.M. How to prepare planners in the Bologna European education context: Adapting Friedmann’s planning theories to practical pedagogy. In Insurgencies and Revolutions. Reflections on John Friedmann’s Contributions to Planning Theory and Practice; Rangan, H., Kam, M., Porter, L., Chase, J., Eds.; Routledge Publisher: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 46–58. [Google Scholar]

- Long, H.; Tu, S. Rural restructuring: Theory, approach and research prospect. Acta Geographica Sinica 2017, 72, 563–576. [Google Scholar]

- Ryser, L.; Halseth, G. Rural economic development: A review of the literature from industrialized economies. Geography Compass 2010, 4, 510–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, K.I.; Reiss, S.A. The rural planning perspective at an opportune time. Journal of Planning Literature 2014, 29, 386–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazorla, A.; Negrillo, X.; Montalvo, V.; De Nicolas, V.L. Institutional Structuralism as a Process to Achieve Social Development: Aymara Women’s Community Project Based on the Working with People Model in Peru. J. Sociol. Soc. Welf. 2018, 45, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobšinská, Z.; Šálka, J.; Sarvašová, Z.; Lásková, J. Rural development policy in the context of actor-centred institutionalism. Journal of Forest science 2013, 59, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De los Ríos, I.; Rivera, M.; García, C. Redefining rural prosperity through social learning in the cooperative sector: 25 years of experience from organic agriculture in Spain. Land Use Policy 2016, 54, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, P. The concept of participation in development. Landscape and urban planning 1991, 20, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, J. Regional Development and Planning: The Story of Collaboration. Int. J. Reg. Sci. 2001, 24, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPMA. Individual Competence Baseline; Version 4.0; International Project Management Association (IPMA): Nijkerk, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- De los Ríos-Carmenado, I.; Ortuño, M.; Rivera, M. Private–Public Partnership as a Tool to promote entrepreneurship for Sustainable Development: WWP Torrearte Experience. Sustainability 2016, 8, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, A.; De los Ríos, I.; Villanueva, J.; Lloa, J.; Santander, D. Sustainability of a Food Production System for the prosperity of Low-Income Populations in an Emerging Country: Twenty Years of Experience of the Peruvian Poultry Association. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sastre-Merino, S.; Negrillo, X.; Hernández-Castellano, D. Sustainability of Rural Development Projects within the Working with People Model: Application to Aymara Women Communities in the Puno Region, Peru. Cuad. Desarro. Rural 2013, 10, 219–243. [Google Scholar]

- Bugueño, F.; De los Ríos, I.; Castañeda, R. Responsible Land Governance and Project Management Competences for Sustainable Social Development. The Chilean-Mapuche Conflict. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 2017, 7, 202–211. [Google Scholar]

- Ortuño, M.; De los Ríos, I.; Sastre-Merino, S. The Development of Skills as a Key Factor of the Cooperative System: Analysis of the Cooperative of Artisan Women Tejemujeres-Gualaceo-Ecuador from the WWP Model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, M.; Cazorla, A.; Panta, M.D. P. Rural entrepreneurship strategies: Empirical experience in the Northern Sub-Plateau of Spain. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, J.P. S.; De los Ríos Carmenado, I.; González, M.L. Management of entrepreneurship projects from project-based learning: Coworking startups project at UPS Ecuador. In Case Study of Innovative Projects-Successful Real Cases. IntechOpen. 2017. .

- Avila Ceron, C.A.; De los Rios, I.; Martín, S. Illicit crops substitution and rural prosperity in armed conflict areas: A conceptual proposal based on the Working with People model in Colombia. Land Use Policy 2018, 72, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda, R. Avila, C.; De los Ríos-Carmenado, I., Ed.; Domínguez, L. & Gomez, S. Implementing the voluntary guidelines on the responsible governance of tenure of land, fisheries and forests from the working with people model: lessons from Colombia and Guatemala, The Journal of Peasant Studies 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliaga, R.; De los Ríos-Carmenado, I.; San Martín Howard, F.; Calle Espinoza, S.; Huamán Cristóbal, A. Integration of the Principles of Responsible Investment in Agriculture and Food Systems CFS-RAI from the Local Action Groups: Towards a Model of Sustainable Rural Development in Jauja, Peru. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, A.T.; De los Ríos-Carmenado, I. & Martínez-Almela, J. Project-based governance framework for an agri-food cooperative. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1881. [Google Scholar]

| 1st selection Scopus |

2nd selection WoS |

3rd. data cleansing | 4th bibliometric analysis |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural development and planning | 6.894 | 1.031 | 5.522 | 5.522 |

| Journal | WoS | Scopus | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP1 | TC | TP | TC | TC | % TC | |

| Land Use Policy | 52 | 1622 | 125 | 4756 | 6378 | 17,9% |

| Landscape and Urban Planning | 14 | 1419 | 70 | 4739 | 6158 | 17,3% |

| Journal of Rural Studies | 23 | 715 | 125 | 3657 | 4372 | 12,3% |

| World Development | 5 | 523 | 20 | 2630 | 3153 | 8,9% |

| Sociologia Ruralis | 8 | 619 | 25 | 1372 | 1991 | 5,6% |

| Journal of Cleaner Production | 7 | 200 | 43 | 1311 | 1511 | 4,2% |

| Science of the total Environment | 5 | 125 | 47 | 1378 | 1503 | 4,2% |

| Journal of Geographical Sciences | 8 | 410 | 50 | 1034 | 1444 | 4,1% |

| Sustainability | 48 | 277 | 113 | 1098 | 1375 | 3,9% |

| Habitat International | 7 | 161 | 28 | 899 | 1060 | 3,0% |

| Journal of Environmental Management | 8 | 264 | 25 | 647 | 911 | 2,6% |

| Applied Geography | 5 | 130 | 12 | 718 | 848 | 2,4% |

| Agricultural Systems | 5 | 174 | 13 | 498 | 672 | 1,9% |

| Biomass & Bioenergy | 6 | 134 | 25 | 529 | 663 | 1,9% |

| Geoforum | 5 | 132 | 16 | 524 | 656 | 1,8% |

| Regional Environmental Change | 6 | 113 | 3 | 495 | 608 | 1,7% |

| European Planning Studies | 6 | 113 | 21 | 332 | 445 | 1,3% |

| International Regional Science Review | 9 | 61 | 19 | 331 | 392 | 1,1% |

| Mountain Research and Development | 7 | 170 | 17 | 195 | 365 | 1,0% |

| I.J. Of Environmental R. & Public Health | 5 | 31 | 34 | 245 | 276 | 0,8% |

| Computers and Electronics In Agriculture | 8 | 93 | 12 | 160 | 253 | 0,7% |

| Cuadernos de Desarrollo Rural | 6 | 91 | 6 | 68 | 159 | 0,4% |

| European Countryside | 11 | 58 | 19 | 100 | 158 | 0,4% |

| Land | 28 | 114 | 4 | 10 | 124 | 0,3% |

| Third World Planning Review | 4 | 19 | 8 | 73 | 92 | 0,3% |

| Authors | Title | Year | Source title | Cited by |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coleman, G. | Logical framework approach to the monitoring and evaluation of agricultural and rural development projects | 1987 | Project Appraisal | 63 |

| Hulme, D. | Learning and not learning from experience in rural project planning | 1989 | Public Administration and Development | 34 |

| Anyanwu, C.N. | The technique of participatory research in community development | 1988 | Community Development Journal | 22 |

| Morss, E.R., Gow, D.D. | Implementing rural development projects: lessons from AID and World Bank experiences. | 1985 | World Bank experiences. | 13 |

| Livingstone, I. | On the concept of ‘integrated rural development planning’ in less developed countries | 1979 | Journal of Agricultural Economics | 12 |

| Leupolt, M. | Integrated rural development: key elements of an integrated rural development strategy | 1977 | Sociologia Ruralis | 11 |

| Authors | Title | Year | Source title | Cited by |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chambers, R. | Whose reality counts? Putting the first last | 1997 | Whose reality counts? Putting the first last | 2029 |

| Chambers, R. | The origins and practice of participatory rural appraisal | 1994 | World Development | 1376 |

| Murdoch, J. | Networks - A new paradigm of rural development? | 2000 | Journal of Rural Studies | 473 |

| Renting, H, Rossing, W.A.H., Groot, J.C.J., Van der Ploeg, J.D. | Exploring multifunctional agriculture. A review of conceptual approaches and prospects for an integrative transitional framework | 2009 | Journal of Environmental Management | 341 |

| Brandon, K.E., Wells, M. | Planning for people and parks: Design dilemmas | 1992 | World Development | 304 |

| Ellis, F., Biggs, S. | Evolving themes in rural development 1950s-2000s | 2001 | Development Policy Review | 254 |

| Leeuwis, C. | Reconceptualizing participation for sustainable rural Development: Towards a negotiation approach | 2000 | Development and Change | 226 |

| Burkey, S. | People first: a guide to self-reliant participatory rural development | 1993 | People first: a guide to self-reliant participatory rural development | 224 |

| Cernea, M.M. | Putting people first: sociological variables in rural development. Second edition | 1991 | Putting people first: sociological variables in rural development. | 132 |

| High, C., Nemes, G. | Social learning in LEADER: Exogenous, endogenous and hybrid evaluation in rural development | 2007 | Sociologia Ruralis | 111 |

| Ray, C. | Towards a meta-framework of endogenous development: Repertoires, paths, democracy and rights | 1999 | Sociologia Ruralis | 100 |

| Bruckmeier, K. | LEADER in Germany and the discourse of autonomous regional development | 2000 | Sociologia Ruralis | 63 |

| Barke, M., Newton, M. | The EU LEADER initiative and endogenous rural development: The application, of the programme in two rural areas of Andalusia, Southern Spain | 1997 | Journal of Rural Studies | 59 |

| Perez, J.E. | The LEADER programme and the rise of rural development in Spain | 2000 | Sociologia Ruralis | 56 |

| Cazorla, A. De los Ríos, I &. Díaz-Puente, J.M. | The LEADER community initiative as rural development model: Application in the capital region of Spain | 2005 | Agrociencia | 37 |

| Diaz-Puente, J.M., Yage, J.L., Afonso, A. | Building evaluation capacity in Spain: A case study of rural development and empowerment in the European union | 2008 | Evaluation Review | 26 |

| Marsden, T., Bristow, G. | Progressing integrated rural development: A framework for assessing the integrative potential of sectoral policies | 2000 | Regional Studies | 21 |

| Hulme, D. | Projects, politics and professionals: Alternative approaches for project identification and project planning | 1995 | Agricultural Systems | 20 |

| OECD | Better policies for rural development | 1996 | Better policies for rural development | 13 |

| Vidal, R.V.V. | Rural development within the EU LEADER+ programme: new tools and technologies | 2009 | AI and Society | 8 |

| Murray, M. | Planning through dialogue for rural development: The European citizens' panel initiative | 2008 | Planning Practice and Research | 5 |

| Keywords and Cluster | % Links strength | % Occurrences | % Nº keywords |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green Cluster | 59,81% | 40,46% | 46,10% |

| Social Planning | 29,63% | 18,86% | 25,97% |

| Economic Development | 9,21% | 7,44% | 3,90% |

| Rural Development Policy | 6,91% | 4,68% | 5,84% |

| Developing Countries | 6,59% | 4,75% | 3,25% |

| Social Development | 3,88% | 2,67% | 5,19% |

| Economic factors | 3,60% | 2,07% | 1,95% |

| Red Cluster | 28,59% | 47,76% | 40,26% |

| Rural Planning | 8,56% | 16,29% | 12,99% |

| Environmental Planning | 5,38% | 5,91% | 7,79% |

| Rural Development | 3,74% | 7,16% | 3,25% |

| Urban Planning | 3,52% | 4,23% | 5,19% |

| Participatory Approach | 3,12% | 2,64% | 5,19% |

| Sustainable Development | 1,81% | 4,76% | 1,30% |

| Regional Planning | 1,41% | 4,46% | 1,30% |

| Land Use Planning | 0,93% | 2,00% | 2,60% |

| Governance Approach | 0,12% | 0,31% | 0,65% |

| Blue cluster | 11,59% | 11,78% | 13,64% |

| Organization And Management | 3,64% | 2,91% | 4,55% |

| Human Resources | 2,52% | 2,90% | 1,95% |

| Rural Population | 1,81% | 1,64% | 0,65% |

| Project Management | 1,71% | 2,48% | 4,55% |

| Health Care Planning | 1,25% | 1,10% | 0,65% |

| Governance Approach | 0,37% | 0,34% | 0,65% |

| Community Development | 0,29% | 0,41% | 0,65% |

| Total General | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Topic | Authors | Nº documents |

|---|---|---|

| “Putting the last first" and "rural development" | Chambers, R. | 7.730 |

| "Putting people first" and "rural development" | Cernea, MM | 3.730 |

| “Working with people" and "rural development" | Cazorla A. De los Ríos, I. | 2.860 |

| “Planning as social learning” | Friedmann, J. | 230 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).