1. Introduction

Over the past years, the world has been exposed to several adverse consequences of uncontrolled development of multiple anthropogenic activities such as transport, urbanization and agriculture. The ever-growing populations, along with the increase in consumer demand and high living standards have amplified pollution in the atmosphere, land and sea [

1]. These act as the ultimate sinks to emerging pollutants as well as persistent organic pollutants. Emerging pollutants encompass compounds of a synthetic origin which are of worldwide use and are deemed as indispensible to the modern society [

1]. Additionally, organic compounds which are resistant to degradation and that persist in the environment are referred to as persistent organic pollutants (POPs) [

2]. The bioaccumulative properties as well as the toxicological effects of such pollutants to ecological integrities and humans contributed to them being of great global concern to the public.

Anthropogenic activities such as personal care , industrial operation and healthcare entails the use of materials that generate waste which give rise to both emerging pollutants and POPs [

3]. This waste ends up in water bodies, consequently contaminating aquatic environments. Being constituents of emerging pollutants and POPs such contaminants are usually resistant to degradation. For this reason they tend to accumulate in the environment and persist for several decades rendering them hazardous to the ecosystem3. Another source of water pollution which contributes to the increase in concentration of emerging and POPs in aquatic environment is plastic [

4] .

Plastics are defined as synthetic organic polymers which are molded into different forms for diverse uses [

5]. Invented over 100 years ago, plastic is now the most used synthetic material [

5]. It is estimated that 280 million tons of plastic are produced annually for the production of packaging materials, storage containers and automobiles to mention a few [

5,

6]. Originally deemed harmless, multiple decades of plastic release in the environment have engendered a vast range of associated problems. Annually, about 500 billion used plastic bags and 35 million plastic bottles also end up in our oceans [

6]. Large bodies of water, primarily, the ocean gyres of the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific Ocean, are becoming sinks for myriad non-biodegradable polymers [

6]. As a result, Earth’s aquatic bodies are being contaminated with plastic and its constituents. The contaminants can be consumed by the aquatic species and persist in their system or even pass on from one generation hence threatening the Earth’s freshwater and ocean ecosystem and biodiversity [

6].

Plastics are composed of one or multiple polymers alongside other additives including inorganic fillers, flame retardants, colorants and plasticisers [

7]. Plasticisers are chemicals added to plastic to improve their flexibility and plasticity whilst decreasing its viscosity and friction during manufacturing of synthetic or semi-synthetic polymers such as polyvinyl chloride (PVC) [

8]. Their effectiveness in producing flexible materials has contributed them to being used in several industries ranging from the automotive industry to the medical field [

9]. There are about 418 additives used in modern European industries which have been established by the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) targeted to improve the polymer structure of specific plastics [

10]. Nowadays, phthalates account for the majority of the plasticiser market. Their popularity is sustained by their low volatility and cost, high durability and ability to generate elastic and flexible materials [

11].

Phthalates are diesters of 1,2-benzenedicarboxylic acid ( or phthalate acid) primarily used as plasticizers in the manufacture of vinyl and exhibit several industrial applications such as personal care products as solvents and plasticisers in making varnishes, lacquers and coatings [

12]. Owing to their large production volumes and their widespread use, phthalates are deemed as the most ubiquitous man-made materials found in the environment [

11,

13,

14]. They have been also detected throughout the worldwide environment in different matrices including: water, sediment, air, soil, sludge, biota and wastewater [

13].

Some of the most common phthalates used in consumer products and to which humans have high exposure rates include: di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP), di-n-butyl phthalate (DBP); diethyl phthalate (DEP); butyl benzyl phthalate (BBzP) and diisobutyl phthalate (DiBP) [

11,

14,

15]. Owing to their prevalence and adverse effects several studies have been conducted to assess phthalate exposure and achieve in-depth knowledge of their repercussions on human health [

15].

Phthalates not chemically bound to plasticisers and are able to leach, migrate or evaporate to different matrices including food [

16]. Moreover, most of consumer products contain phthalates and thus can result in both direct and indirect exposure. Direct exposure from consumer products results from direct use of these products whilst indirect exposure results from the leaching of phthalate acid esters (PAEs) into other products as well as from environment contamination [

16]. Throughout their life, humans are exposed to phthalates through inhalation, ingestion and dermal exposure, including during intrauterine development. For this reason, several authorities have established monitoring systems and risk assessments among societies to monitor the exposure and to safeguard the environment and humans from high exposure rates of phthalates [

16].

Recently, toxicological concerns about phthalates rose due to their possible endocrine- disrupting potency. The potential phthalates to cause negative effects on the development of humans and reproduction was evaluated by the National toxicology program centre for the evaluation of risks to human reproduction [

16]. Due to lack of human studies with regard to toxicity, experimental animals were investigated and their effects were compared to the estimations and human exposure data. Based on such data it was established that PAEs may result in histological changes in testes, reduced sperm count and reduced fertility. With regards to developmental studies, it was reported that exposure to phthalates may result in prenatal mortality, reduced birth weight and growth and promote visceral, skeletal and external malformations [

16].

The occurrences and persistence of phthalates in different environmental matrices, their exposure to species and their toxicological effects contribute in them being hazardous to the environment as well as to humans. Therefore, the monitoring of PAEs in different matrices is requisite to protect biological diversity, survey future natural events and implement effective environmental practices.

Being surrounded by the sea, the assessment of different classes of pollutants in the Maltese islands is usually performed in marine environment matrices. Vella et al. [

17] assessed the organotin pollution in Maltese coastal zone specifically, in seawater and sediment of the Maltese marine environment. In such study, the tributyltin levels were recorded the highest in yacht marinas’ sediments and seawater samples from harbours and drydocks. Results obtained in this study were linked to the anthropogenic sources including agricultural pesticides, antifouling marine paints and shipyards operations involving hull cleaning.

Similar studies were carried out by Huntingford and Turner [

18] in which trace metals were recorded in sediments from large harbours and public slipways in Malta. Comparison of data showed little difference between the sediments of the varied locations. Nonetheless, low concentrations of contaminant metals (Cr and Sn) were recorded lower ion slipways than in harbours thus attributing the sources of contaminant metals to diffuse and specific waste inputs from shipping and boating activities.

In a pilot study González-Mazo et al., [

19] ten predominant target compounds were monitored in the Northern Maltese coast. The most prominent groups of compounds detected were; pharmaceutical products, synthetic fragrances and UV filters. The occurrence of such compounds was presumed to be of human action origin such as wastewater discharges, recreational activities and ship traffic.

Azzopardi et al. [

20] assessed the presence of heavy metals pollution, primarily; Mn, Fe, Pb, Sr, Zn and Cu sandy beaches. In this study, bays of high heavy metal content were linked to the increased geological wear rate induced by waves and anthropogenic contamination. The results of the mentioned studies thus suggest that the major source of marine environment contamination is chiefly related to human interference.

The aim of this study is to investigate the presence of phthalates in the Maltese islands using sand as a matrix in two distinct categories of beaches exposed to different anthropogenic pressures. This study establishes whether the occurrence and distribution of phthalates in the Maltese shoreline sand are associated with different exposures to human activities. To our knowledge, this investigation is the first to report the occurrence of PAEs in the Maltese islands. The occurrence of phthalates in different matrices and the effect of anthropogenic sources are of great concern to the authorities to mitigate the pollution sources and safeguard the environment; thus, this study provides an in-depth overview of the occurrence of phthalates in conjunction with different artificial factors and human interferences, to improve such knowledge. This research is focused on the quantification of common PAEs, namely; Di-n-butyl phthalate (DBP) and Di-(2-ethyl) hexyl phthalate (DEHP) and their distribution in the Maltese shoreline sands. The sands from which the samples were collected were categorised as busy and secluded beaches to assess the occurrence with respect to the human impacts.

Assessment of PAEs in Maltese shoreline sand involved statistical analysis of the data acquired from the 75 samples collected which were analysed in triple repeatability. Statistical analysis allowed for comparison of data of occurrence of phthalates in different beaches. Moreover, statistical analysis also allowed for the characterisation of the distribution of DBP and DEHP along the shoreline and at perpendicular distances away from the tideline in different beaches to classify the occurrence of phthalates according to their possible anthropogenic sources.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The studied region

The presence of PAEs was studies in 6 sandy beaches in Malta (illustrated in

supplementary Figure S1). Three of the beaches were categorised as busy beaches whilst another three were categorised as secluded beaches. The different categories of beaches account for different anthropogenic activities in the beaches. The category of ‘Busy Beaches’ consists of popular beaches in Malta which are frequented by many locals and tourists and thus, are subject to increased anthropogenic pressures such as littering and /or increased boat activity. For this reason, they are considered as pollution hotspots when compared to the secluded beaches which are not as frequented as the busy beaches and are less subjected to human interference. The locations which were investigated in this study, along with their coordinates, and number of samples are listed in

Table 1.

Supplementary Figure S2 provides more detail of the locations of the beaches investigated through aerial views showing the sampling points of each beach.

2.2. Collection of samples

A standard sampling procedure was established to sample different beaches. Such procedure involved the establishments of a line transect which was placed at the length of the beach. The line transect was set perpendicularly to the shoreline and a distance of 20m was maintained between each sampling station. At each sampling station a 1m2 metal quadrat was placed at the high tideline (origin). Using a metal ruler and a metal hand shovel, the uppermost 10 cm of sand (amounting to approximately 150g) were collected. Starting from the origin, the transect line was then divided into 4 m segments and the quadrat was placed along the transect line at 4m interval. A maximum of 12 m away from the shoreline distance was maintained when sampling large beaches. The sand samples collected were transferred to amber bottles with metal caps and were subsequently stored at -18◦C until extraction.

2.3. Chemicals used

All chemicals used were of HPLC grade. Methanol was obtained from BDH chemicals. Acetone and n-Hexane were purchased from Riedel-de Haën™ and Carlo Erba respectively. Ultra-pure water for mobile phase was obtained from Ultra-pure water of 18MΩ obtained from ElgaPure Lab Classic purifier. Di-n-butyl phthalate (DBP) (purity: 99.5%) and Bis (2-ethyl hexyl) phthalate (DEHP) (purity 99.5%) were purchased from Chem Service.

2.3. Extraction Procedure

DBP and DEHP were extracted from sand using the method suggested by Chen at al, [

21] with some modifications. The sand samples were dried in an oven at a temperature of 105

°C for 24 hours. 5 grams of sand were weighed and placed in pre-cleaned glass vials. Subsequently, 15 mL of acetone/n-hexane solution with 1:1 volumetric ratio was added to the sand. Samples were placed in an ultrasonic device for 15 minutes. The extract was then filtered through a syringe filter of 0.45 µm to remove any sediment particles and to attain a clear extract. The extract was then evaporated to dryness under nitrogen flow and was the reconstituted to 0.5 mL with methanol for analysis.

2.4. PAEs Analysis and Instrumental Conditions

After extracting PAEs from the sieved sand samples, Ultra-performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC–MS/MS) was used to quantify the concentrations of phthalates, based on the response areas given by the peaks at their respective retention time. This technique has significant technological advances including high resolution, sensitivity and speed of analysis. Additionally, it has substantially lower run time than the conventional liquid chromatography method thus reduces the solvent consumption [

22].

In this investigation Waters® ACQUITY UPLC System coupled with TQ-D Detector (UPLC-MS/MS) was used for quantification of DBP and DEHP. MassLynx™ software v.4.1 was used for data acquisition and analysis of peaks. Chromatographic separation of phthalates was achieved using an ACQUITY UPLC® BEH C18 column 1.7µm (2.1× 500 mm). The system consisted of two mobile phases A and B. Mobile phases A and B were prepared by adding 0.1% formic acid in ultra-pure water and methanol respectively. The column temperature was increased to 40◦C and the injection volume was of 10 µL. The system had a flow rate was 0.5 mL/min and the total run time was 15 minutes. The UPLC MS/MS was also equipped with an ACQUITY UPLC isolator column (p/n: 186004476) between the mobile phase mixer and the sample manager injector. This allowed for any background phthalates to be retained on the Isolator column till they are eluted by the gradient via the analytical column at a later time than the analytes in the samples. In such manner, the separation of the analyte phthalate peak from the background phthalates peaks enable more reliable quantification as the background phthalates would be isolated. Additionally, week needle wash consisting of 1L of 25% methanol in water, strong needle wash consisting of 1L of 100% methanol and seal wash containing 1L of 10: 90 methanol/water were prepared. The wash solvents were used between each injection of the sample. The mass spectrometer conditions consisted of ES+ ionisation mode and source temperature and desolvation temperatures of 150 °C and 500 °C, respectively with desolvation gas rate of 500 L/ hr, 4kV capillary voltage, using Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM).

Quantification was performed by external standard method. A seven-point calibration curve at 0.0025, 0.005, 0.01, 0.05, 0.25, 0.5 and 1 ppm was plotted for DBP and DEHP respectively. The response areas were quantified at retention time 6.62 for DBP and at 7.91 for DEHP. The background phthalates of the respective analyte were detected at least 0.5 minutes later. The curves exhibited good linearity with R2 values greater than 0.9979. Each sample was quantified by triple repeatability, and an average concentration of the phthalates quantified was taken. A blank consisting of 100% methanol was injected between each sampling station, and none of the blanks showed contamination suggesting that there was no carryover from one sample to another. A calibration check was performed between each beach location by running a standard of a concentration within the calibration curve (0.05ppm) for both phthalates. After plotting the calibration curves, the limit of quantification (LOQ) and limit of detection (LOQ) were calculated for DBP and DEHP. The LOQ and LOD were 0.0008 µg/g and 0.0003 µg/g for respectively for DBP and 0.0084 µg/g and 0.0010 µg/g respectively for DEHP.

2.6. Recovery Studies

Prior to performing the above extraction procedure on all of the samples collected, three samples were collected to test the extraction efficiency. Different studies performed an extraction on different sand particle sizes [

21,

23,

24]. For this reason the sand samples were sieved at different sizes namely: >500, 250 and 125 µm. Subsequently, the extraction procedure was performed on the three samples and was analysed by UPLC. The fraction of sand collected at 125 µm was the best detected in all samples as this fraction attained the largest response areas overall with respect to the other fractions. Accordingly, extraction recovery was performed on the sand fraction collected at 125 µm.

The extraction recovery involved weighing 5g of sand obtained in the fraction of interest and dividing it into two portions of 2.5g. One of the portions was spiked with 0.05 ppm of DBP and DEHP standards prior to performing the extraction process. Conversely, the other sand portion was left unspiked and the extraction procedure was performed and repeated three times. The extraction recovery was calculated through the concentrations obtained of spiked and unspiked samples and the expected concentration of the spiked sample after evaporation as shown in the below formula.

The average extraction recovery values for DBP and DEHP were 94.7% (± 3.6 %) and 119.2% (± 9.4 %), respectively. Thus, both within the acceptance limits (70-120%, RSD< 20%), hence the extraction process was regarded as efficient.

In order to determine the stability of the sample after collection as well as to detect systematic errors due to sample matrix, spike recovery was performed. Spike recovery was achieved by performing the extraction procedure on the sand with particle size of >125 µm which attained and ideal extraction recovery value. The reconstituted sample was thereafter split into two equal parts- one of which was spiked and the other was left unspiked. The spike recovery was calculated using the concentrations obtained of spiked and unspiked samples and the expected concentration of the spiked sample after adding the standard, as shown in the below formula:

The spike recovery value for DBP and DEHP obtained were 96.05 % and 93.90%, respectively. Since the extraction recovery values and the spike recovery values were in an acceptable range, the above extraction procedure was efficient to be performed on the samples for quantification of DBP and DEHP in the Maltese shoreline sand.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

IBM SPSS (Version 25.0) was used to perform statistical tests involving the normality of data, independent samples test such as Kruskal-Wallis test, Mann-Whitney U test and pairwise- comparison of data. The tests were performed with a 95% confidence interval on the obtained data. JMP Trial 16 software was used for cluster analysis.

5. Conclusions

The results obtained provide the first data of the occurrence and distribution of phthalates acid esters in Maltese shoreline sand. The quantification of DBP and DEHP concentrations demonstrated that overall the Maltese shoreline sand is characterized by lower phthalate esters concentrations than those quoted in literature. Moreover, DEHP attained higher concentrations and more extensive concentration ranges than DBP. The occurrence of the two phthalate esters was investigated by statistical analysis of the comparison of concentration means in different beaches.

The comparison of mean DBP and DEHP concentrations in different beaches suggested that the occurrence of phthalate esters varies significantly. . The statistical significance in the average DBP and DEHP concentrations in different beaches was attributed to different factors such as littering, topography and agricultural activities that characterise the beaches distinctively. The presumed anthropogenic pressures were analysed by comparing the average DBP and DEHP concentrations in busy and secluded beaches. Statistical analysis demonstrated that the DBP and DEHP concentrations are related to anthropogenic activities as a higher mean rank was obtained by the two phthalates in beaches categorised as busy.

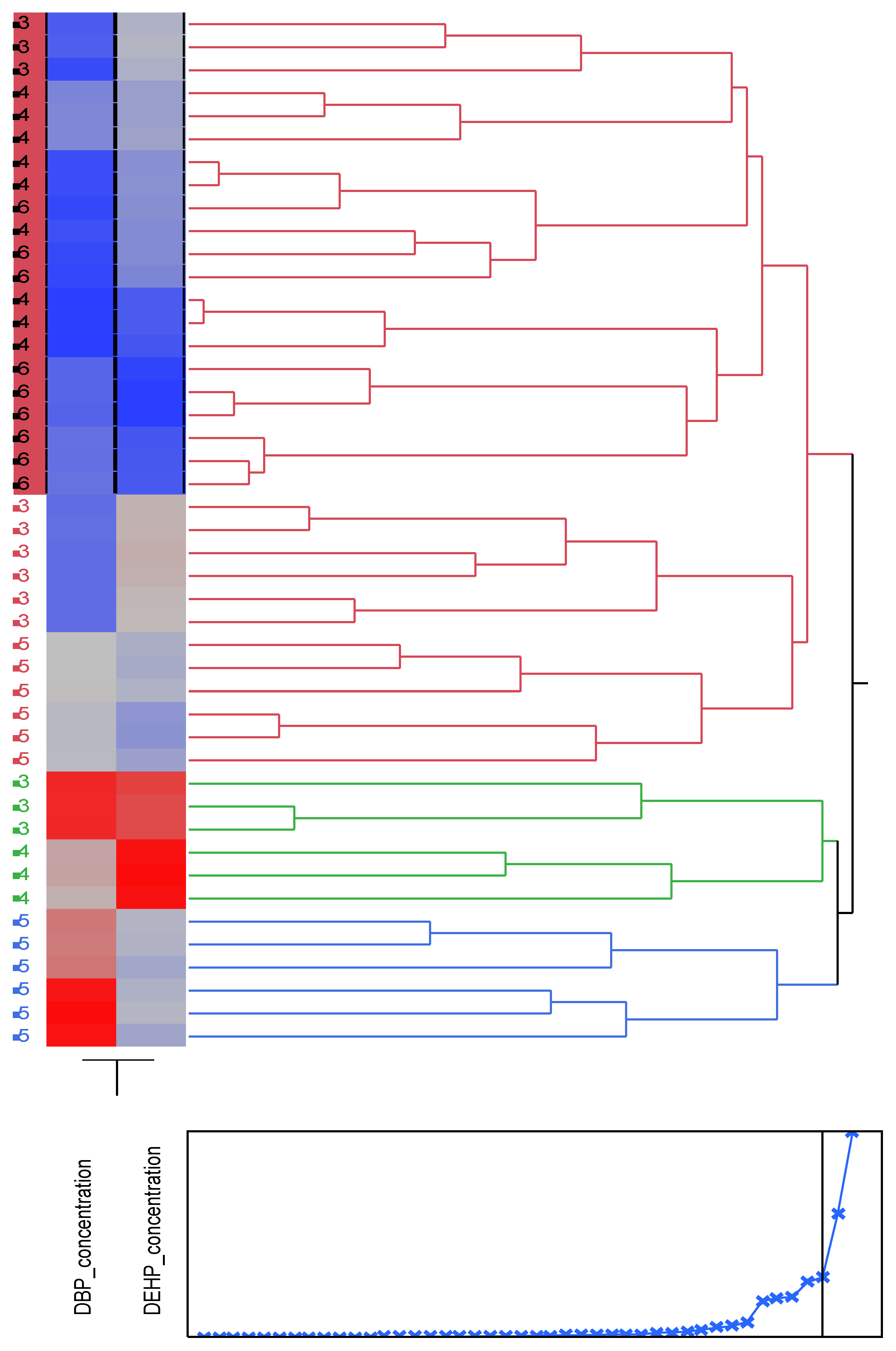

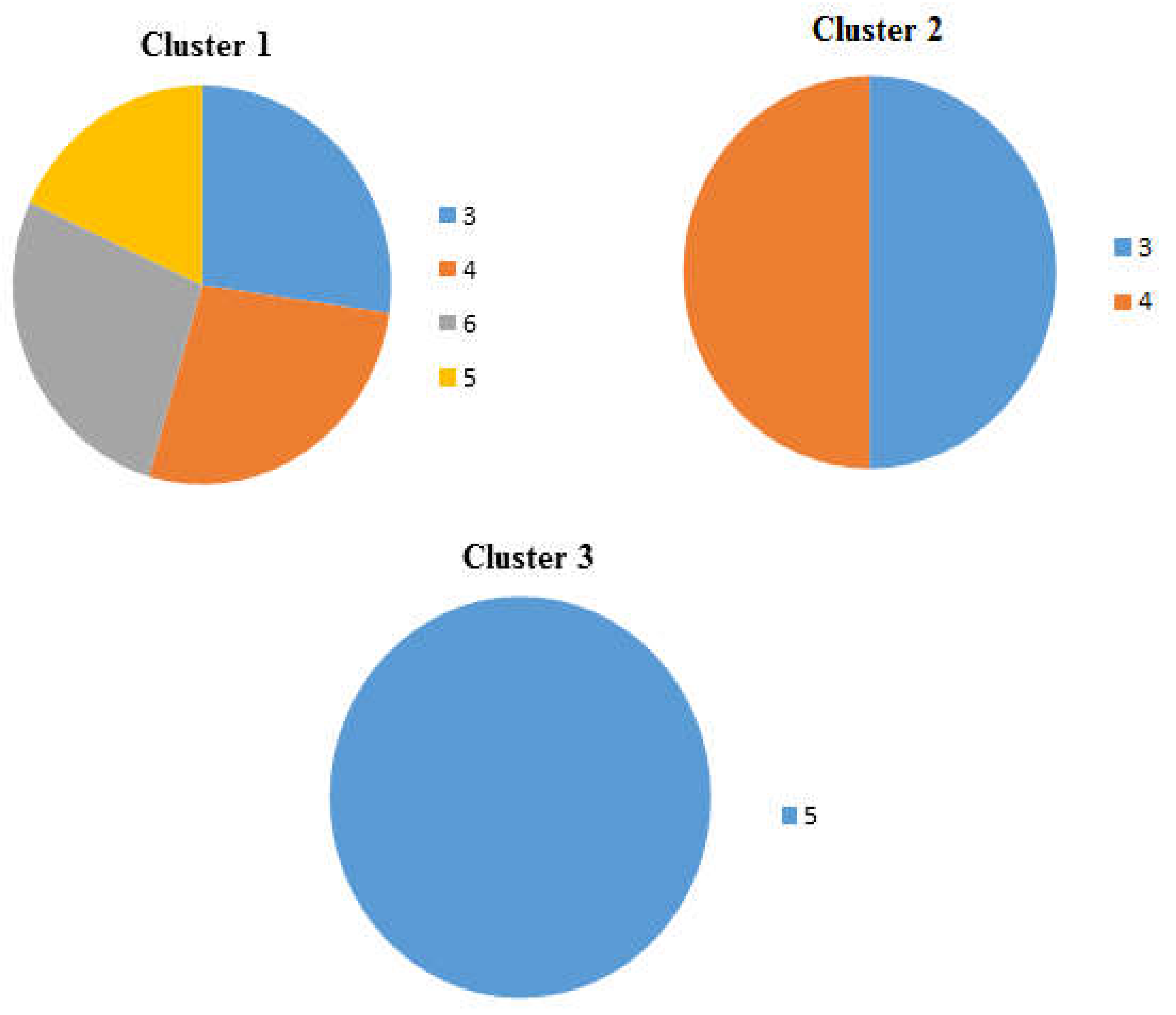

The study of the distribution of phthalates along the beach showed that the average concentrations along the shoreline vary, and both phthalates are not equally distributed. The analysis of the distribution of phthalates at distances away from the shore showed that DBP and DEHP exhibit different distributions. DBP showed a homogenous distribution, whilst DEHP showed an uneven distribution. The differences in distribution were attributed to the topography of the different chemodyanmic properties of the two phthalates, wave action and anthropogenic activities. Cluster Analysis confirmed that the increase in concentrations at distances away from the sea is attributed to wave action and anthropogenic stresses.

Further scientific analysis is suggested to assess the phthalates occurrences by investigating the presence of more PAEs and to scrutinize the distribution temporally in attempt of minimizing the pollution on sandy beaches and to reduce the ecological risks.

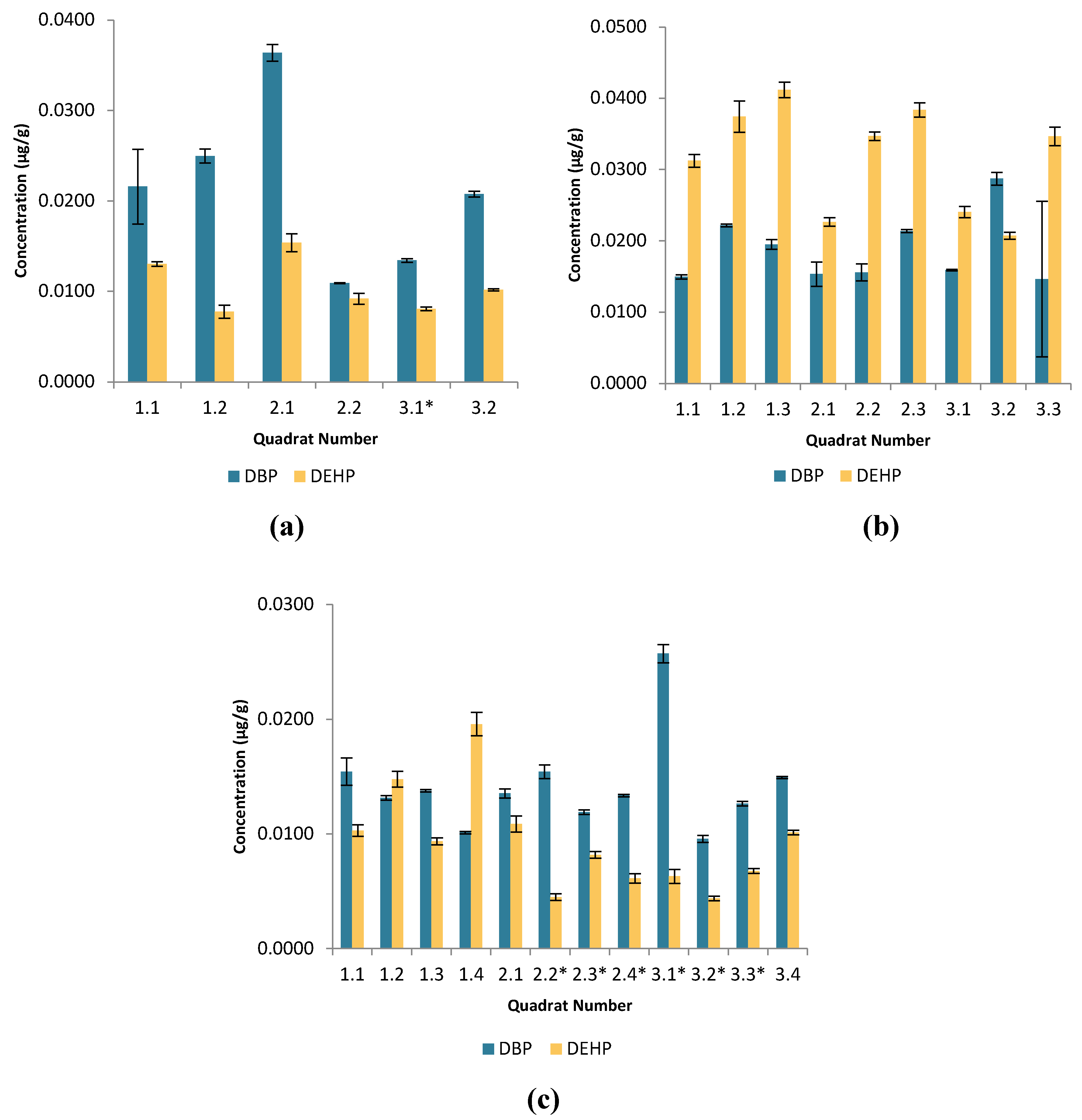

Figure 1.

Bar graphs showing the average DBP and DEHP concentrations (µg/g) in different quadrats at the secluded beaches of (a) Imgiebah (b) Ghar ahmar (c) White Tower and their respective standard deviation indicated by the error bars ; * represents DEHP concentrations <LOQ.

Figure 1.

Bar graphs showing the average DBP and DEHP concentrations (µg/g) in different quadrats at the secluded beaches of (a) Imgiebah (b) Ghar ahmar (c) White Tower and their respective standard deviation indicated by the error bars ; * represents DEHP concentrations <LOQ.

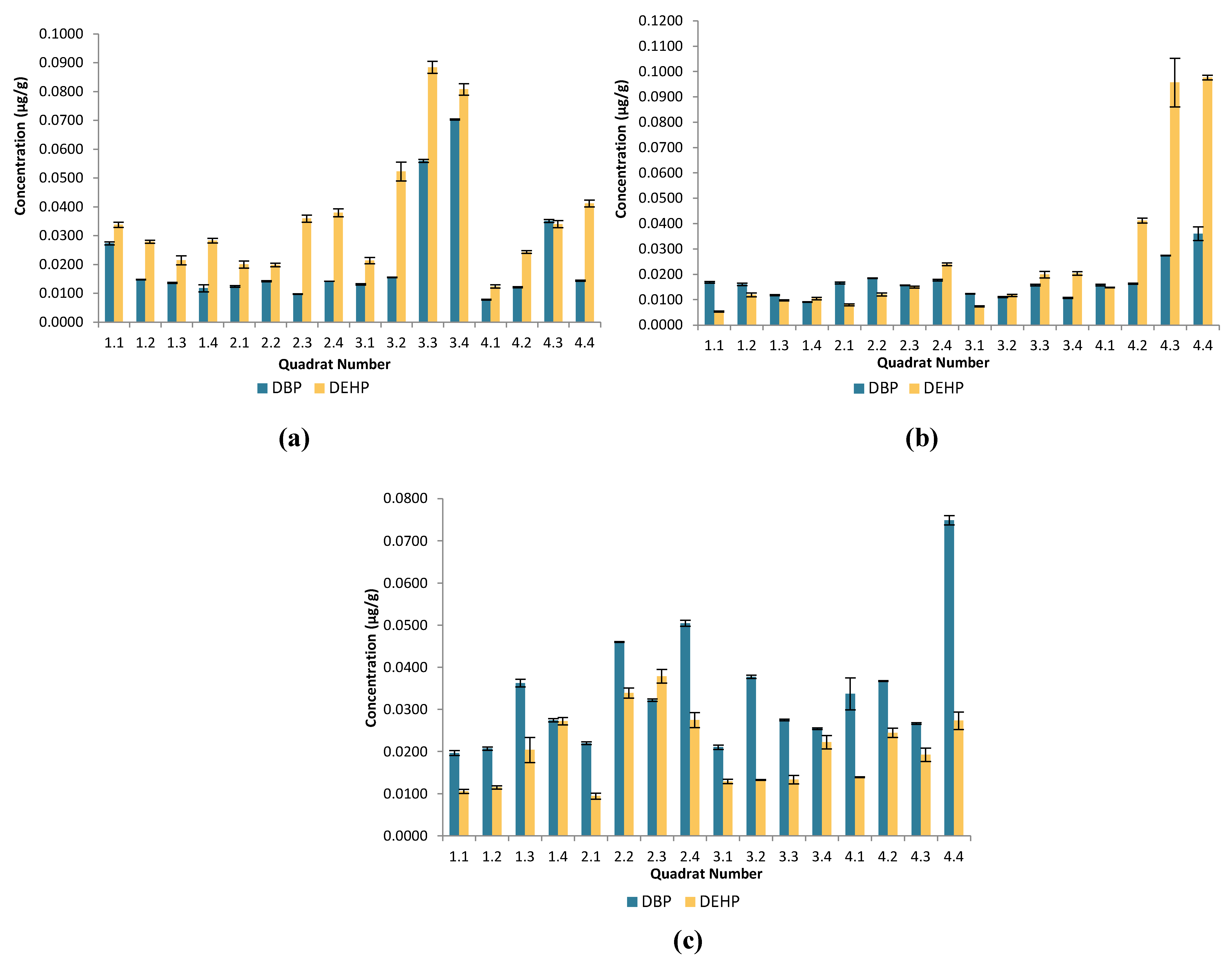

Figure 2.

Bar graphs showing the average DBP and DEHP concentrations (µg/g) in different quadrats at the busy beaches of (a) Paradise Bay (b) Ġnejna (c) Riviera and their respective standard deviation indicated by the error bars.

Figure 2.

Bar graphs showing the average DBP and DEHP concentrations (µg/g) in different quadrats at the busy beaches of (a) Paradise Bay (b) Ġnejna (c) Riviera and their respective standard deviation indicated by the error bars.

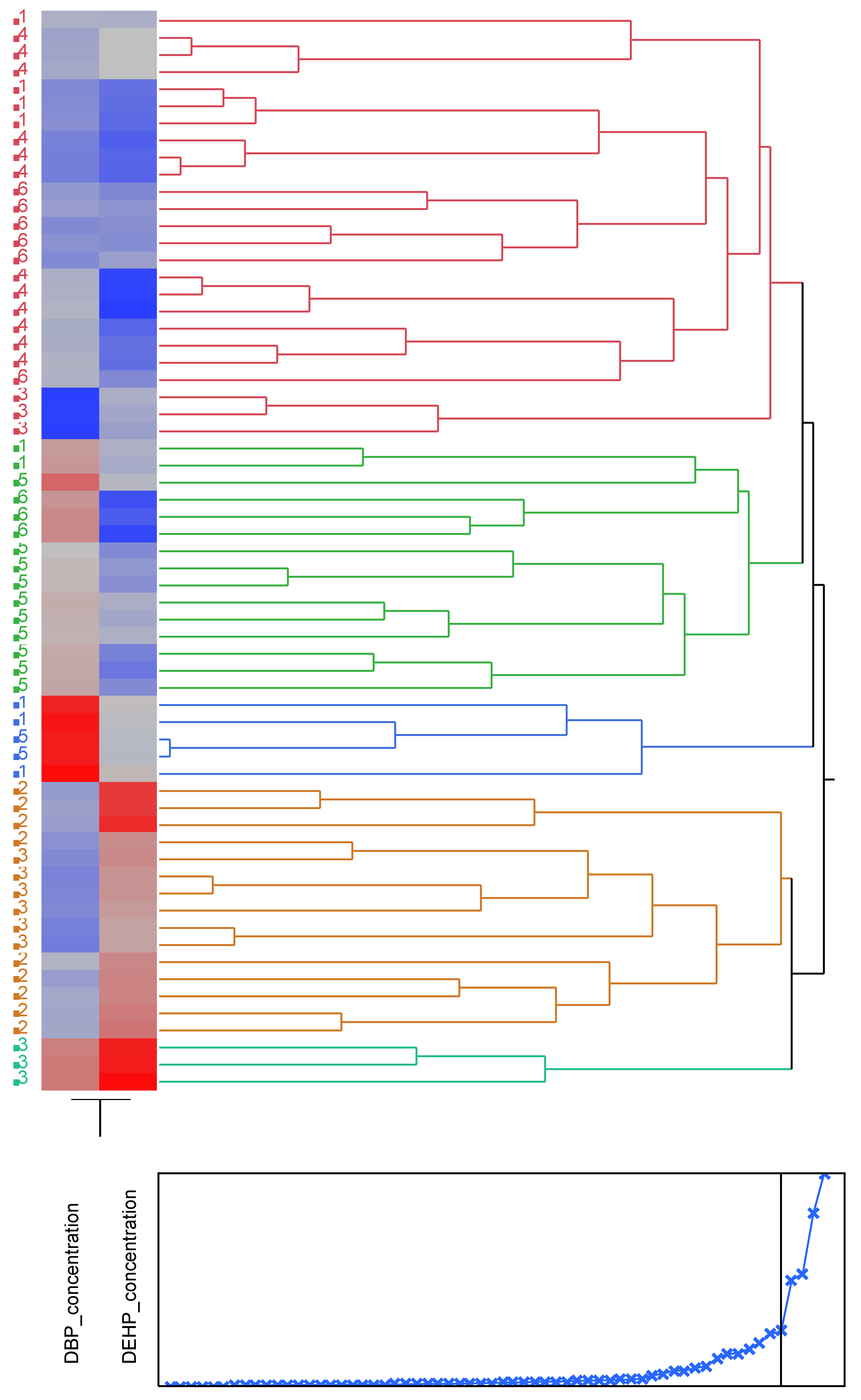

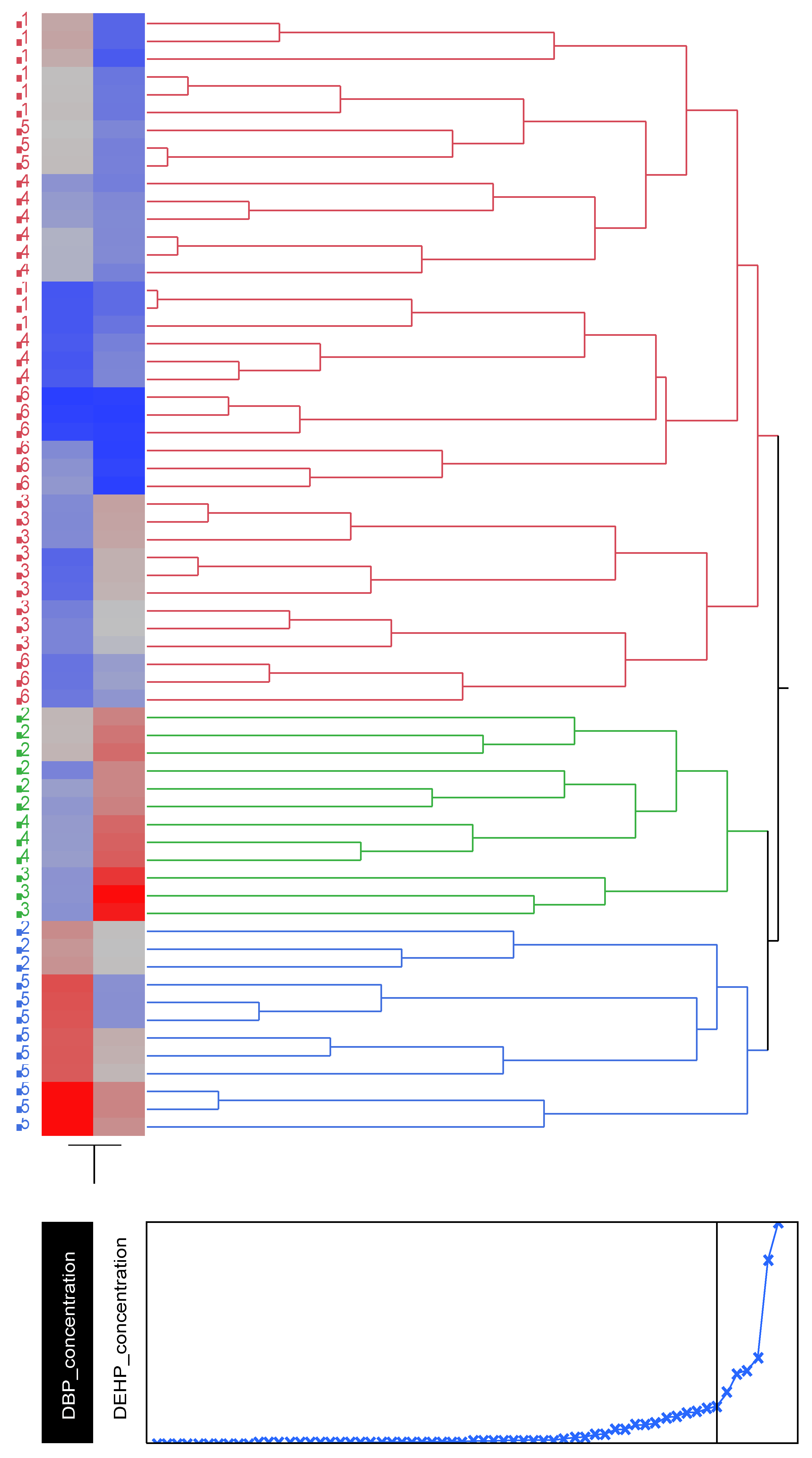

Figure 3.

Cluster analysis showing dendrogram and heat map (blue boxes representing low concentrations and red boxes representing high concentration) of the DBP and DEHP at a distance at the tideline (0m from the sea) , 1-Imġiebaħ 2- Għar Aħmar, 3-Paradise Bay, 4- Ġnejna, 5-Riviera, 6-White Tower.

Figure 3.

Cluster analysis showing dendrogram and heat map (blue boxes representing low concentrations and red boxes representing high concentration) of the DBP and DEHP at a distance at the tideline (0m from the sea) , 1-Imġiebaħ 2- Għar Aħmar, 3-Paradise Bay, 4- Ġnejna, 5-Riviera, 6-White Tower.

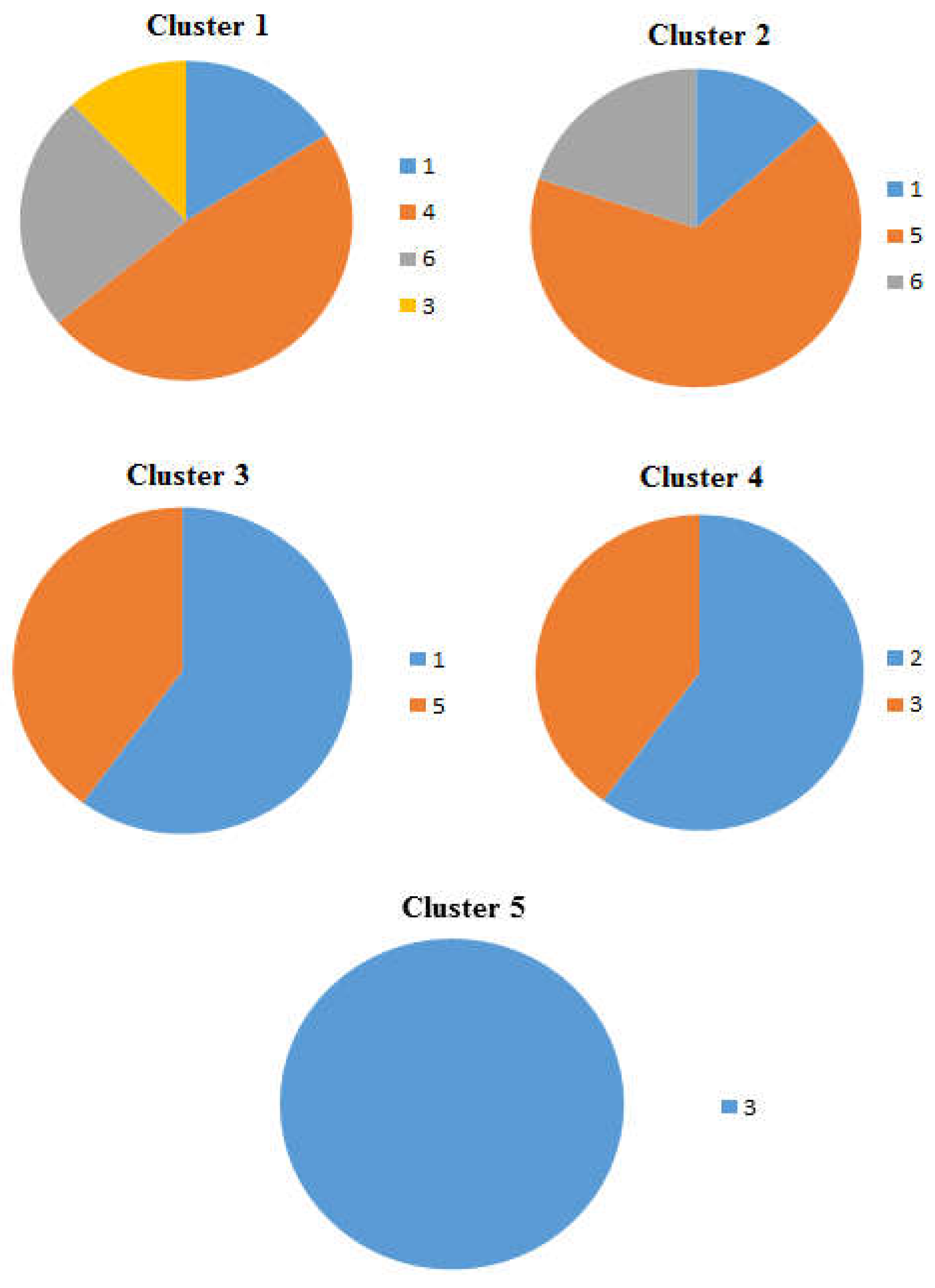

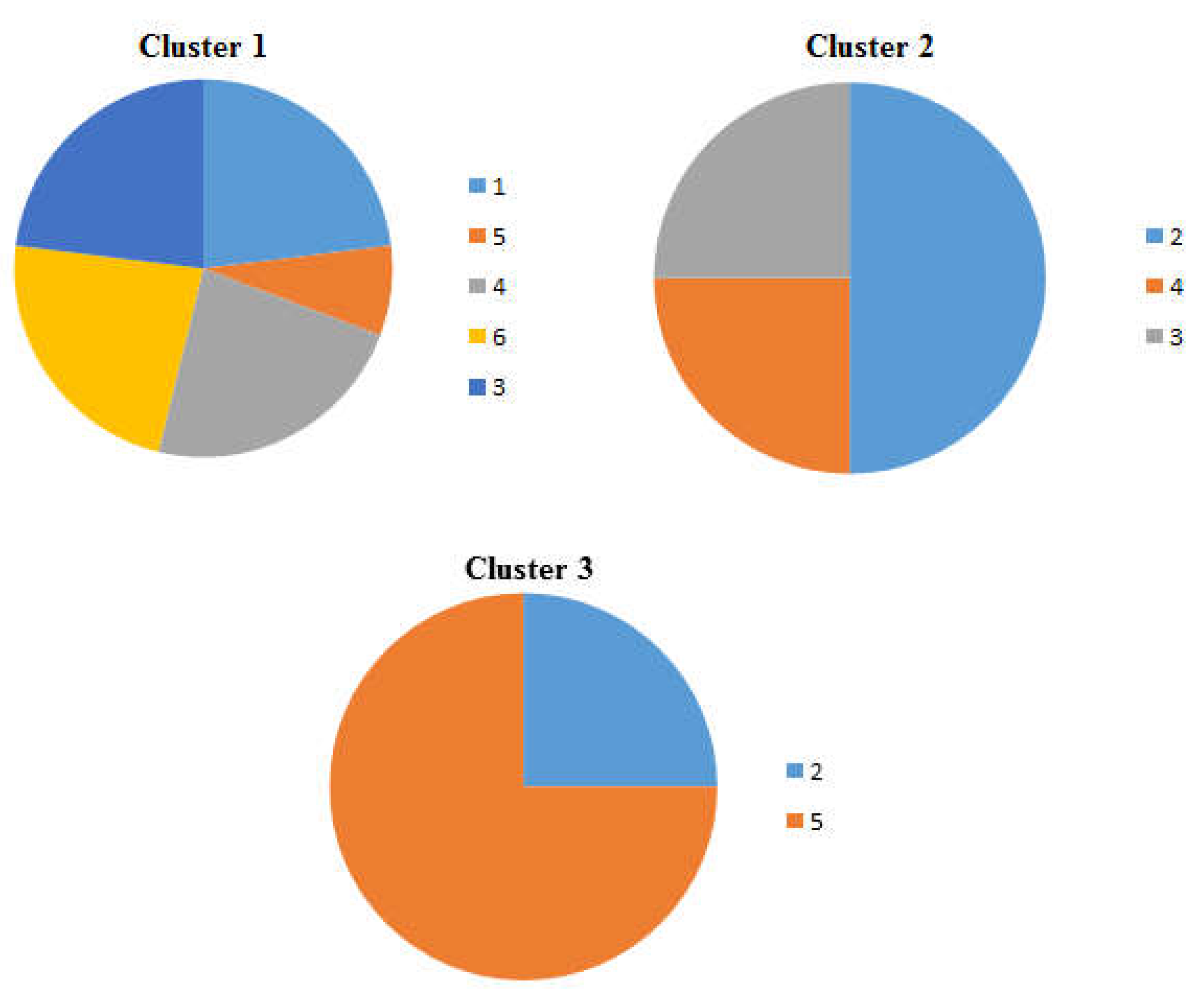

Figure 4.

Pie charts showing the percentage occurrence of the beaches in each cluster of the dendrogram and heat map at distance at the tideline (0 m from the sea) , 1-Imġiebaħ 2- Għar Aħmar, 3-Paradise Bay, 4- Ġnejna, 5-Riviera, 6- White Tower.

Figure 4.

Pie charts showing the percentage occurrence of the beaches in each cluster of the dendrogram and heat map at distance at the tideline (0 m from the sea) , 1-Imġiebaħ 2- Għar Aħmar, 3-Paradise Bay, 4- Ġnejna, 5-Riviera, 6- White Tower.

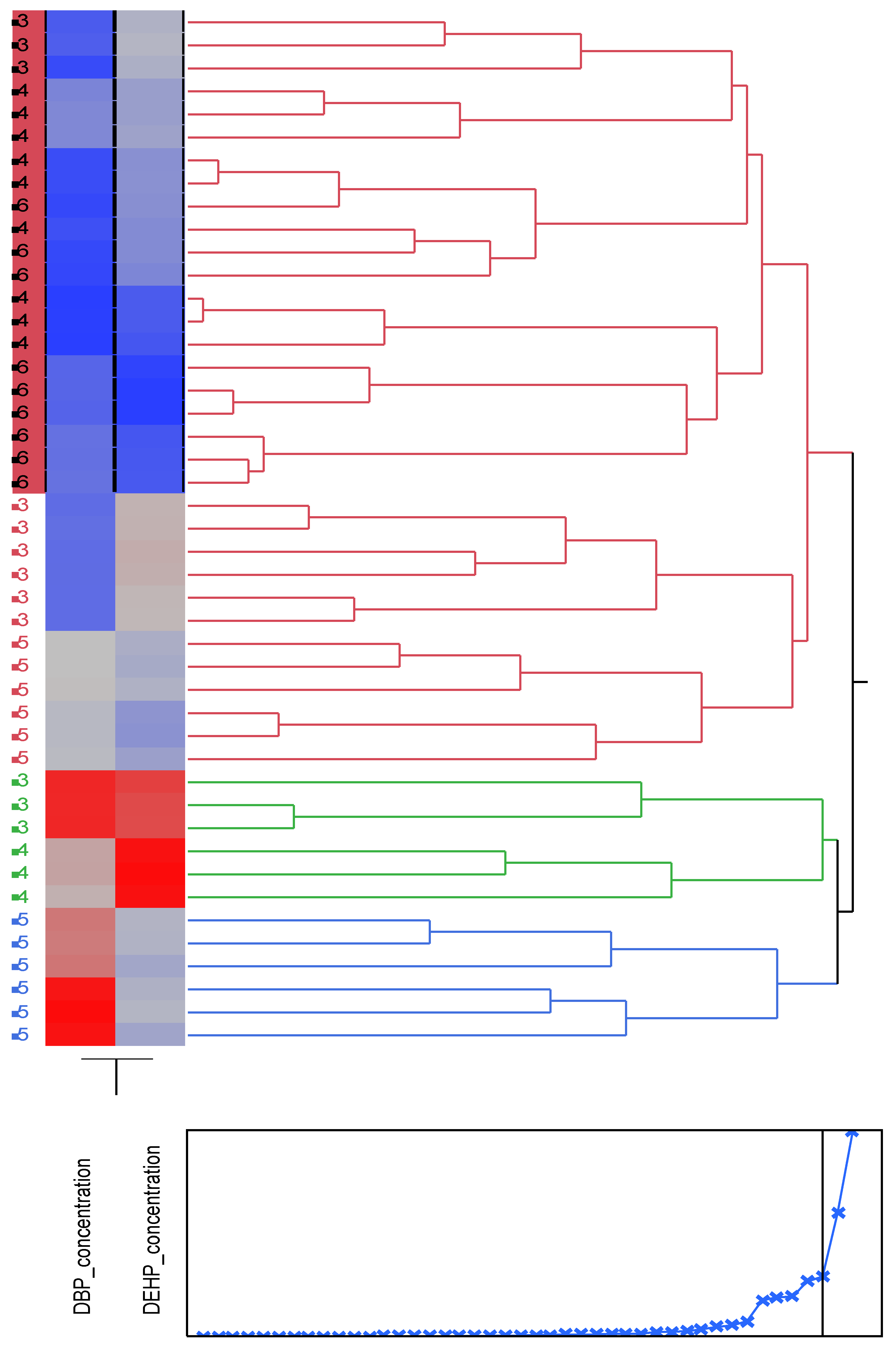

Figure 5.

Cluster analysis showing dendrogram and heat map (blue boxes representing low concentrations and red boxes representing high concentration) of the DBP and DEHP at a distance of 4 m from the tideline , 1-Imġiebaħ 2- Għar Aħmar, 3-Paradise Bay, 4- Ġnejna, 5-Riviera, 6-White Tower.

Figure 5.

Cluster analysis showing dendrogram and heat map (blue boxes representing low concentrations and red boxes representing high concentration) of the DBP and DEHP at a distance of 4 m from the tideline , 1-Imġiebaħ 2- Għar Aħmar, 3-Paradise Bay, 4- Ġnejna, 5-Riviera, 6-White Tower.

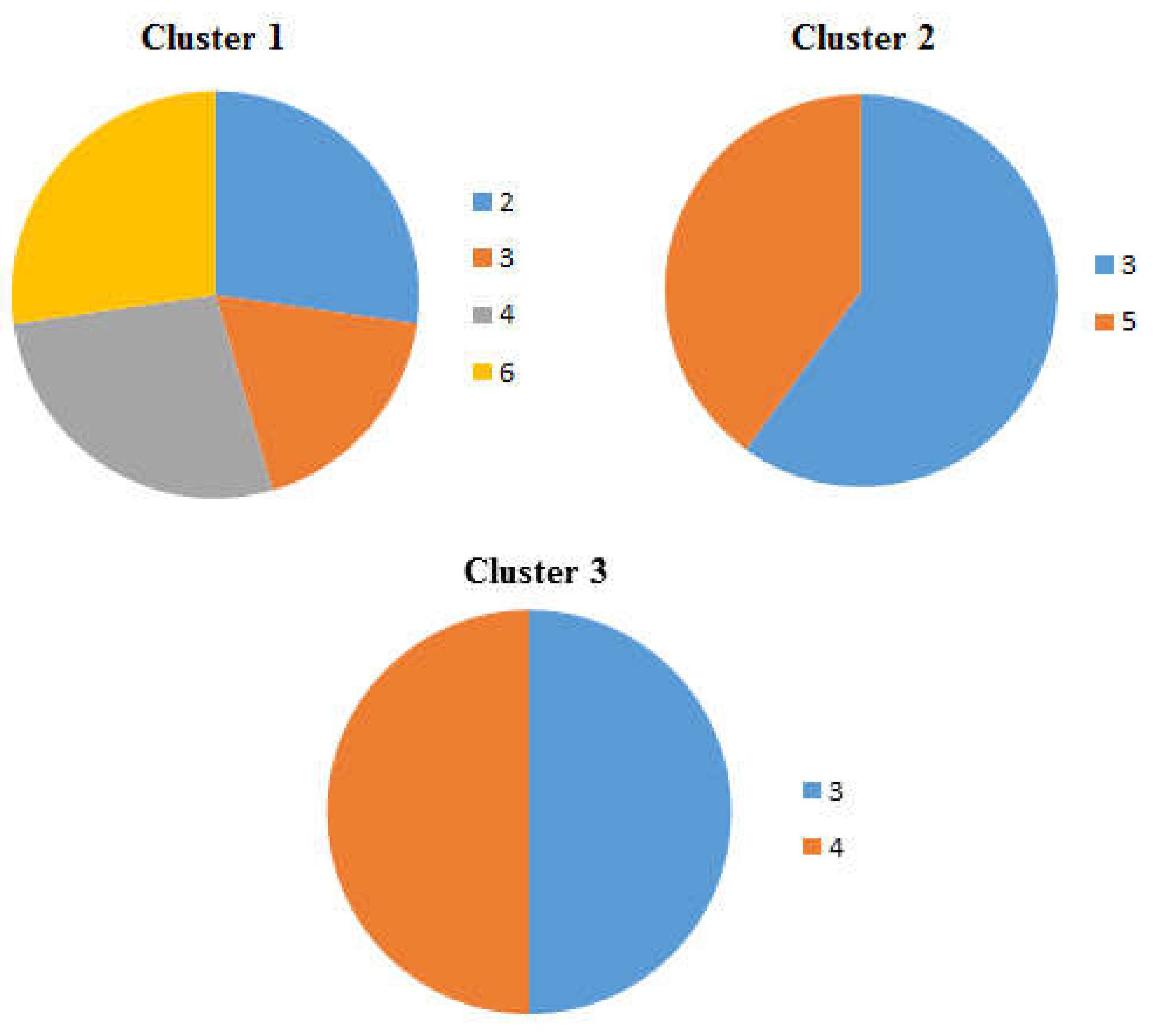

Figure 6.

Pie charts showing the percentage occurrence of the beaches in each cluster of the dendrogram and heat map at distance of 4 m from the tideline , 1-Imġiebaħ 2- Għar Aħmar, 3-Paradise Bay, 4- Ġnejna, 5-Riviera, 6- White Tower.

Figure 6.

Pie charts showing the percentage occurrence of the beaches in each cluster of the dendrogram and heat map at distance of 4 m from the tideline , 1-Imġiebaħ 2- Għar Aħmar, 3-Paradise Bay, 4- Ġnejna, 5-Riviera, 6- White Tower.

Figure 7.

Cluster analysis showing dendrogram and heat map (blue boxes representing low concentrations and red boxes representing high concentration) of the DBP and DEHP at a distance of 8 m from the tideline , 1-Imġiebaħ 2- Għar Aħmar, 3-Paradise Bay, 4- Ġnejna, 5-Riviera, 6-White Tower.

Figure 7.

Cluster analysis showing dendrogram and heat map (blue boxes representing low concentrations and red boxes representing high concentration) of the DBP and DEHP at a distance of 8 m from the tideline , 1-Imġiebaħ 2- Għar Aħmar, 3-Paradise Bay, 4- Ġnejna, 5-Riviera, 6-White Tower.

Figure 8.

Pie charts showing the percentage occurrence of the beaches in each cluster of the dendrogram and heat map at distance of 8 m from the tideline , 1-Imġiebaħ 2- Għar Aħmar, 3-Paradise Bay, 4- Ġnejna, 5-Riviera, 6- White Tower.

Figure 8.

Pie charts showing the percentage occurrence of the beaches in each cluster of the dendrogram and heat map at distance of 8 m from the tideline , 1-Imġiebaħ 2- Għar Aħmar, 3-Paradise Bay, 4- Ġnejna, 5-Riviera, 6- White Tower.

Figure 9.

Cluster analysis showing dendrogram and heat map (blue boxes representing low concentrations and red boxes representing high concentration) of the DBP and DEHP at a distance of 12 m from the tideline , 1-Imġiebaħ 2- Għar Aħmar, 3-Paradise Bay, 4- Ġnejna, 5-Riviera, 6-White Tower.

Figure 9.

Cluster analysis showing dendrogram and heat map (blue boxes representing low concentrations and red boxes representing high concentration) of the DBP and DEHP at a distance of 12 m from the tideline , 1-Imġiebaħ 2- Għar Aħmar, 3-Paradise Bay, 4- Ġnejna, 5-Riviera, 6-White Tower.

Figure 10.

Pie charts showing the percentage occurrence of the beaches in each cluster of the dendrogram and heat map at distance of 12 m from the tideline , 1-Imġiebaħ 2- Għar Aħmar, 3-Paradise Bay, 4- Ġnejna, 5-Riviera, 6- White Tower.

Figure 10.

Pie charts showing the percentage occurrence of the beaches in each cluster of the dendrogram and heat map at distance of 12 m from the tideline , 1-Imġiebaħ 2- Għar Aħmar, 3-Paradise Bay, 4- Ġnejna, 5-Riviera, 6- White Tower.

Table 1.

A list of the sandy beaches and their corresponding coordinates and number of samples.

Table 1.

A list of the sandy beaches and their corresponding coordinates and number of samples.

| Category |

Location Name |

Location Coordinates |

No. of Samples |

| Secluded Beaches |

Imġiebaħ |

35◦58’03.91”N |

6 |

| 14◦22’55.07”E |

| White Tower |

35◦59’32.91”N |

12 |

| 14◦21’55.63”E |

| Għar Aħmar |

35◦50’00.95”N |

9 |

| 14◦32’42.01”E |

| Busy Beaches |

Ġnejna |

35◦55’13.38”N |

16 |

| 14◦20’36.27”E |

| Paradise Bay |

35◦58’55.07”N |

16 |

| 14◦19’56.69”E |

| Riviera |

35◦55’45.57”N |

16 |

| 14◦20’41.94”E |

Table 2.

A summary of the bays which showed a statistical significance (p<0.05) upon pairwise comparisons of Kruskal-Wallis test when comparing PAEs concentrations in different beaches.

Table 2.

A summary of the bays which showed a statistical significance (p<0.05) upon pairwise comparisons of Kruskal-Wallis test when comparing PAEs concentrations in different beaches.

| Pairwise Comparison |

p values of pairwise comparisons of Kruskal-Wallis Test |

| Bay 1-Bay 2 |

DBP Concentrations |

DEHP Concentrations |

| Paradise Bay-Riviera Bay |

0.000 |

0.006 |

| Ġnejna Bay –Riviera Bay |

0.000 |

- |

| White Tower bay –Riviera Bay |

0.000 |

0.000 |

| Għar Aħmar – Riviera Bay |

0.002 |

0.011 |

| White tower Bay-Għar Aħmar |

0.006 |

- |

| Imġiebaħ- Riviera Bay |

0.012 |

0.007 |

| White tower Bay- Imġiebaħ |

0.035 |

- |

| Imġiebaħ-Għar Aħmar |

- |

0.000 |

| Imġiebaħ-Paradise bay |

- |

0.000 |

| Ġnejna Bay- Għar Aħmar |

- |

0.000 |

| Ġnejna Bay- Paradise Bay |

- |

0.000 |

| White Tower Bay- Għar Aħmar |

- |

0.000 |

| White Tower Bay –Paradise Bay |

- |

0.000 |

| White Tower Bay-Ġnejna Bay |

- |

0.001 |

Table 3.

The meak ranks of the concentrations of PAEs in secluded beaches and busy beaches.

Table 3.

The meak ranks of the concentrations of PAEs in secluded beaches and busy beaches.

| |

Mean Ranks |

| |

Secluded Beaches |

Busy Beaches |

| DBP Concentrations |

96.42 |

122.33 |

| DEHP Concentrations |

87.26 |

127.48 |

Table 4.

A summary of the distances along the shoreline at which the PAEs concentrations showed a statistical significance (p<0.05) upon pairwise comparisons of Kruskal-Wallis test.

Table 4.

A summary of the distances along the shoreline at which the PAEs concentrations showed a statistical significance (p<0.05) upon pairwise comparisons of Kruskal-Wallis test.

| Pairwise Comparisons |

p values of pairwise comparisons of Kruskal-Wallis Test |

| Distance along the shoreline (m) |

DBP Concentrations |

DEHP Concentrations |

| 0.00-60.00 |

0.037 |

0.001 |

| 20.00-60.00 |

- |

0.004 |

| 40.00-60.00 |

- |

0.000 |

Table 5.

A summary of the distances away from the shoreline at which the DEHP concentrations showed a statistical significance (p<0.05) upon pairwise comparisons of Kruskal-Wallis test.

Table 5.

A summary of the distances away from the shoreline at which the DEHP concentrations showed a statistical significance (p<0.05) upon pairwise comparisons of Kruskal-Wallis test.

| Pairwise Comparison |

p values of pairwise comparisons of Kruskal-Wallis Test |

| Distance (m) |

DEHP Concentrations |

| 0.00-8.00 |

0.000 |

| 0.00-12.00 |

0.000 |

| 4.00-12.00 |

0.048 |