Submitted:

08 May 2023

Posted:

09 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

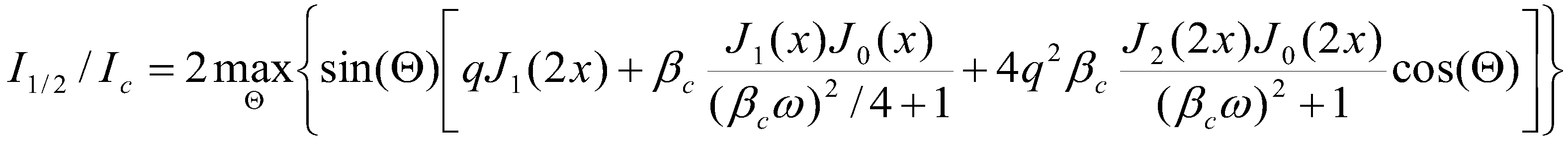

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

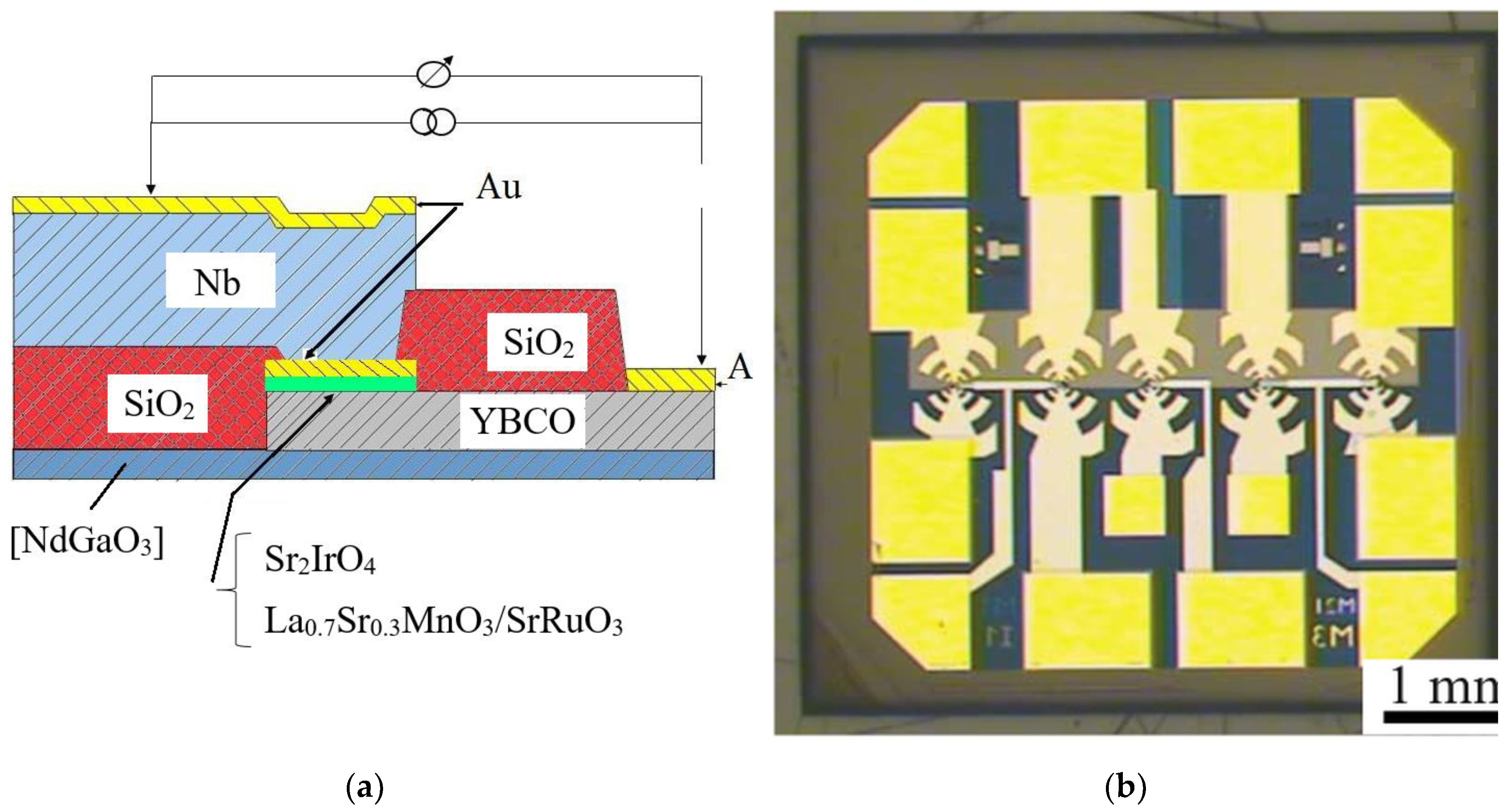

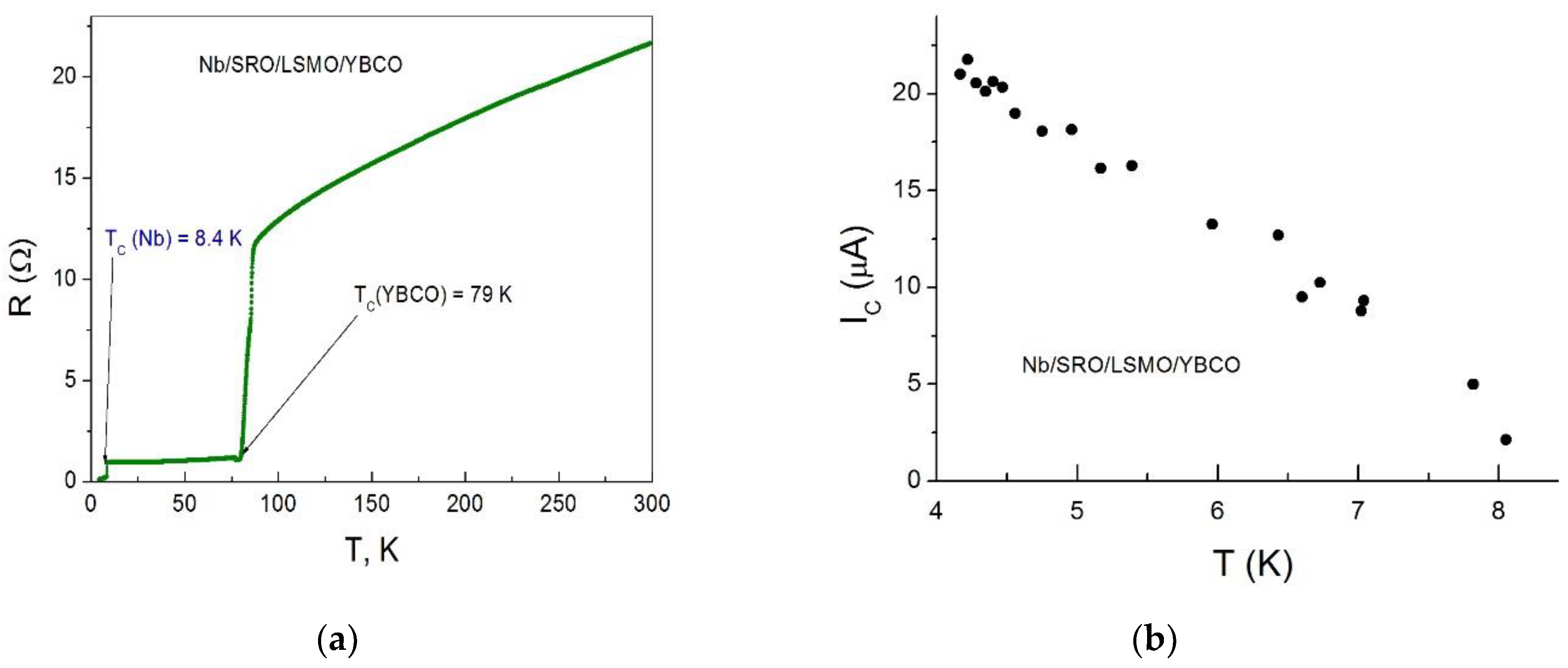

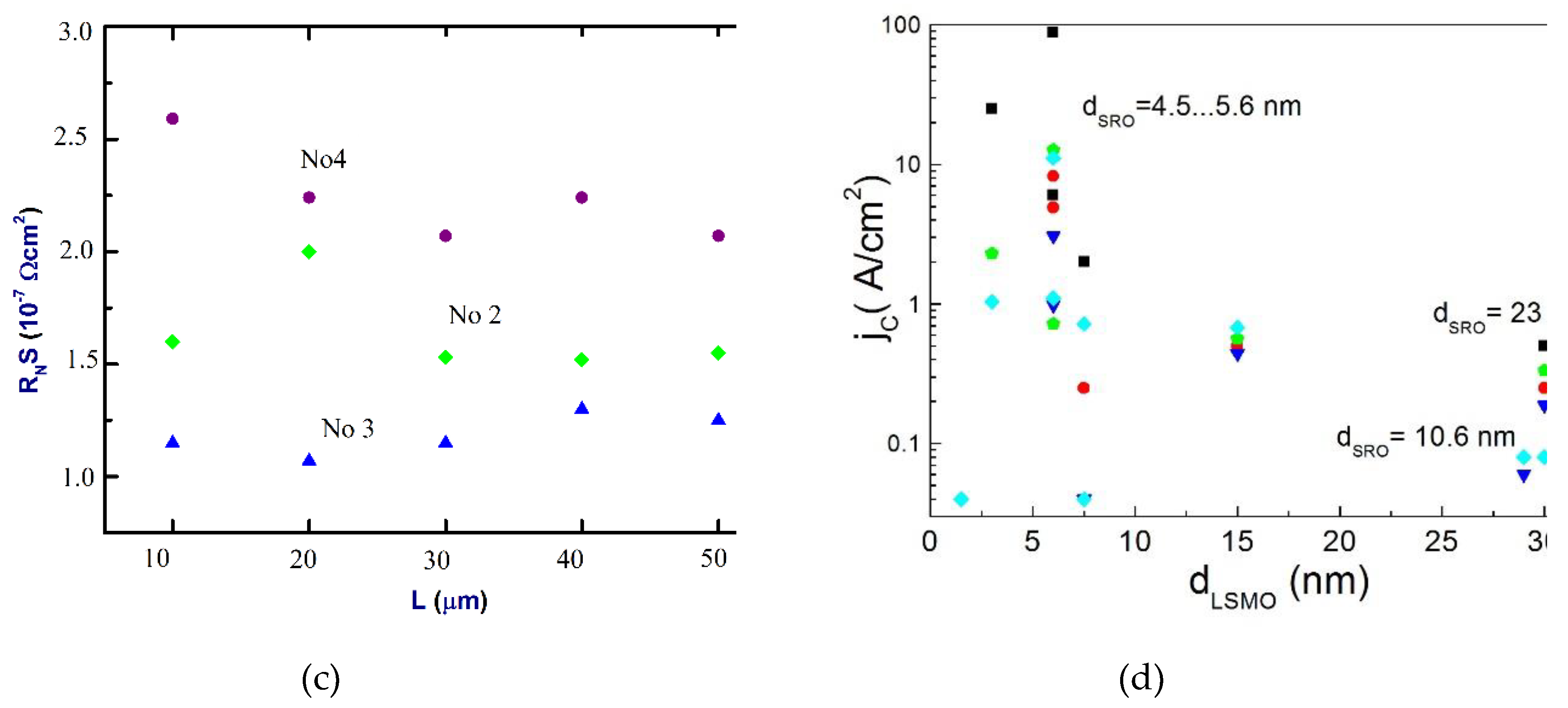

3.1. DC transport characteristics

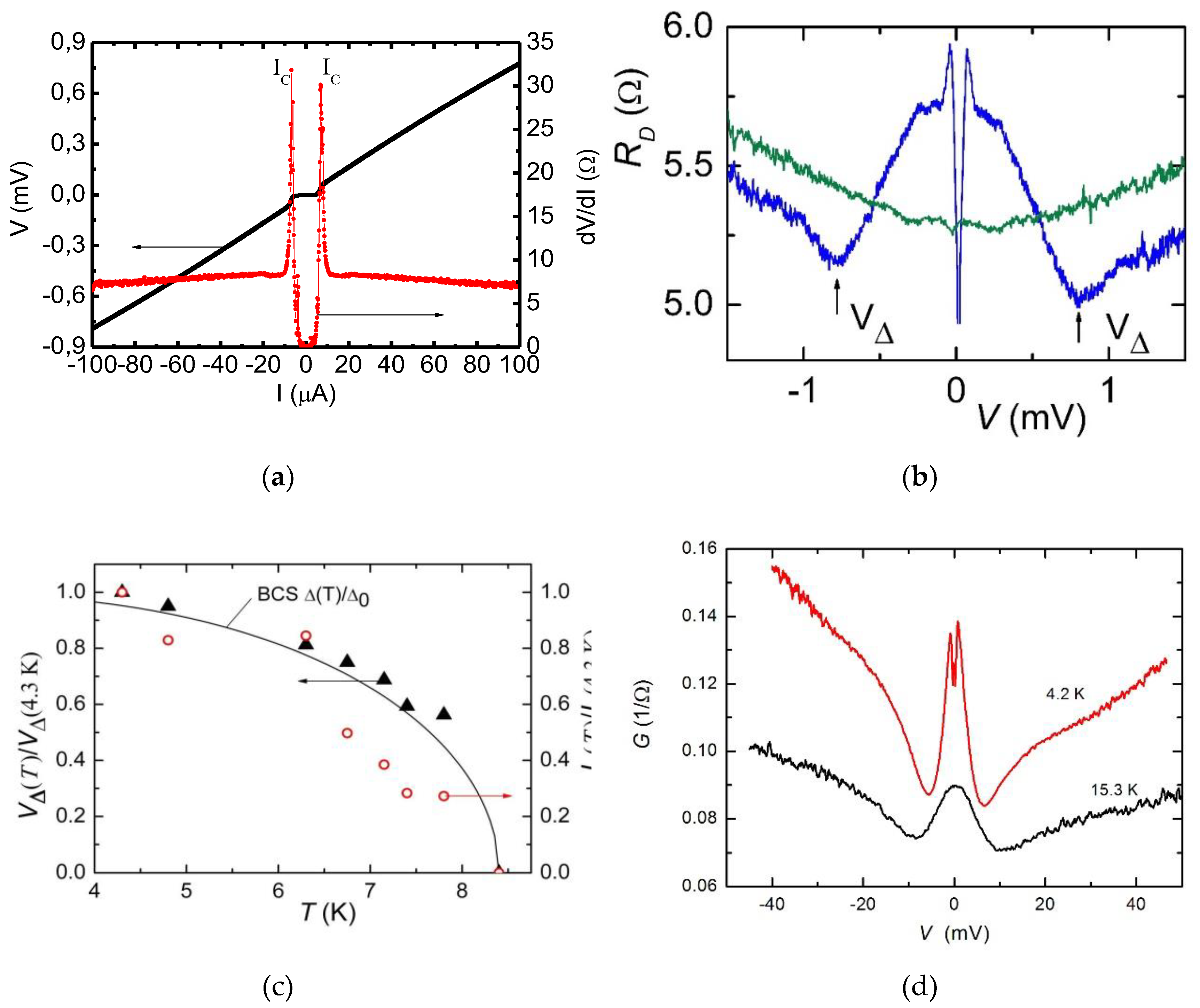

3.2. Magnetic field dependences.

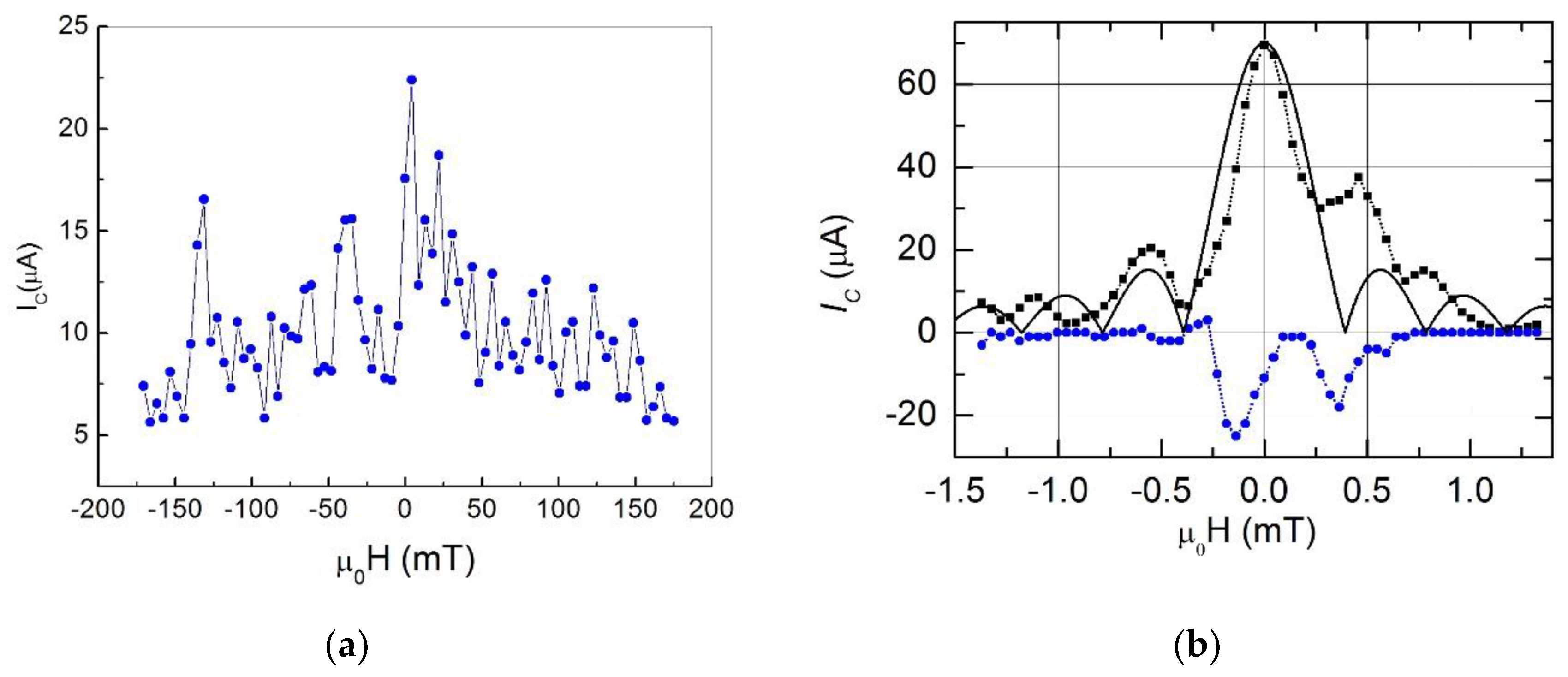

3.3. Microwave characteristics

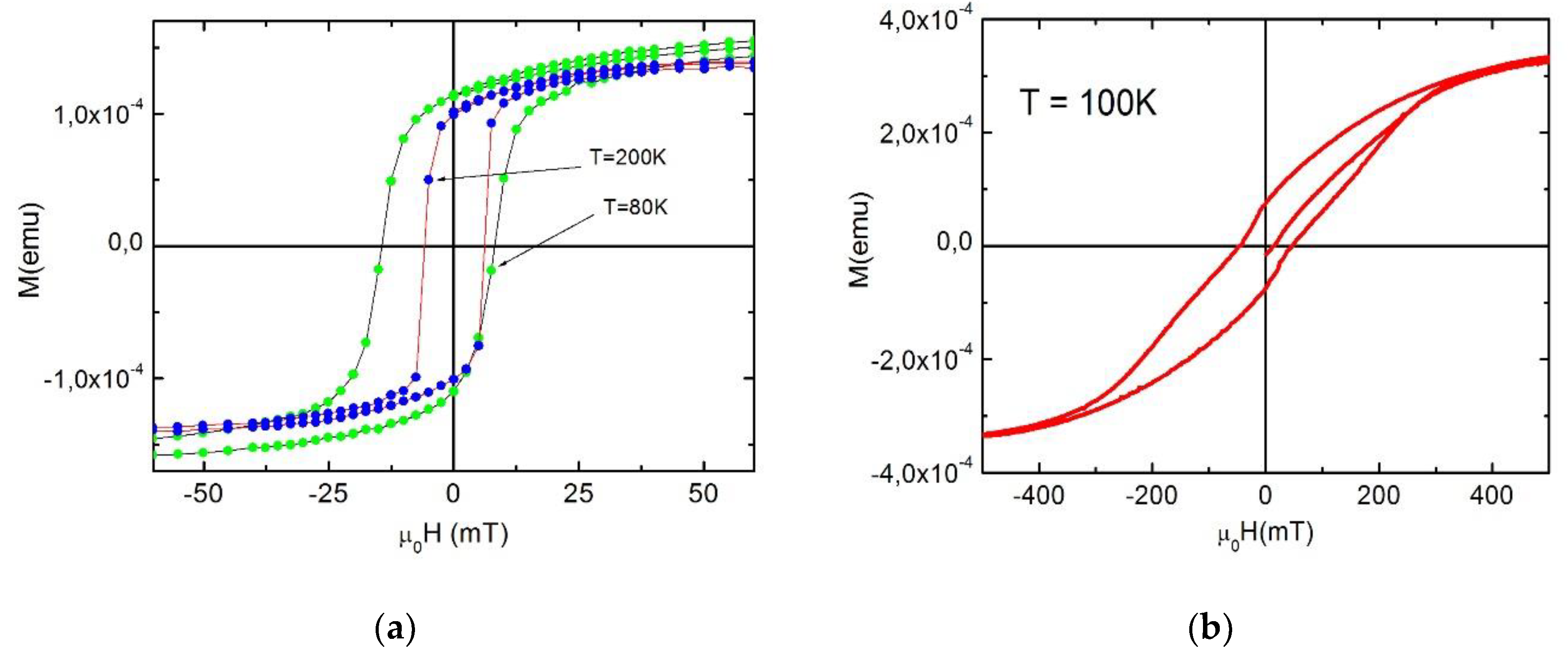

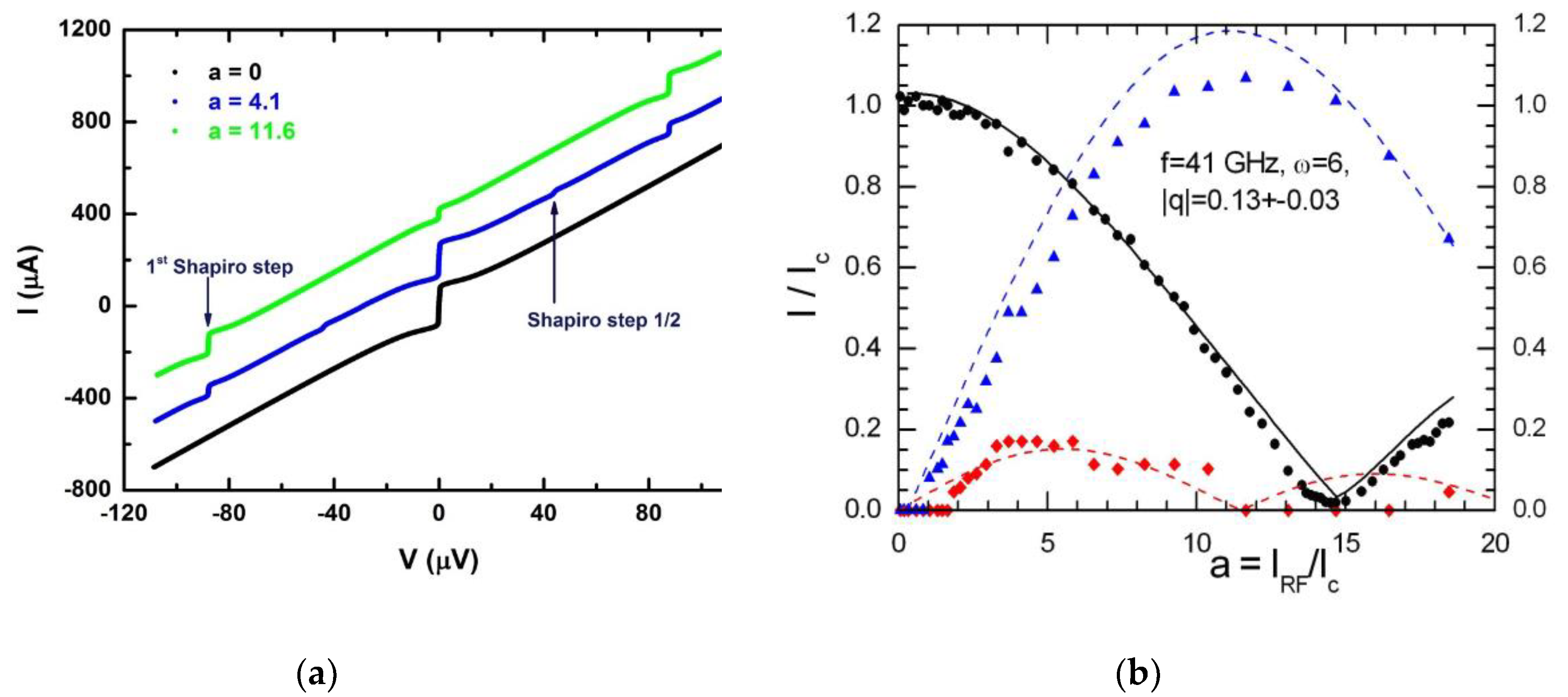

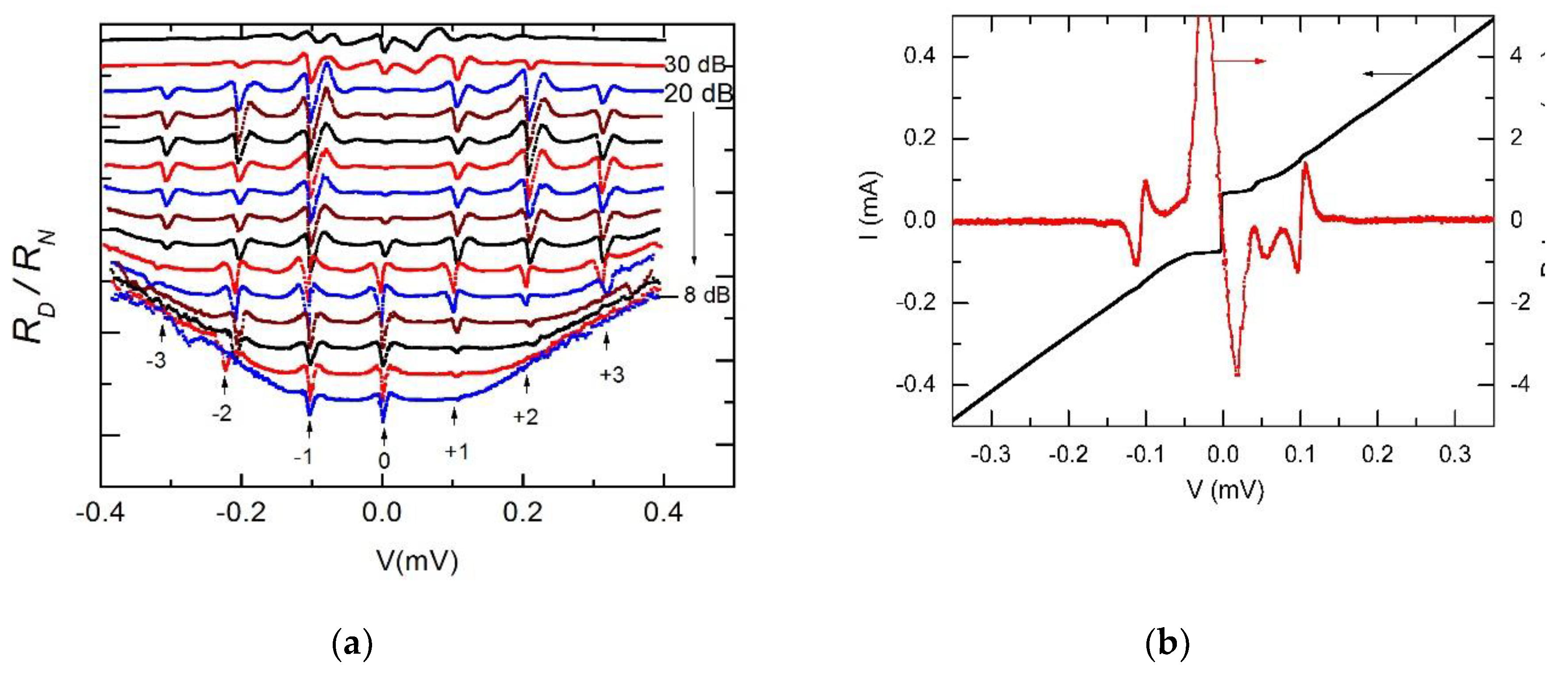

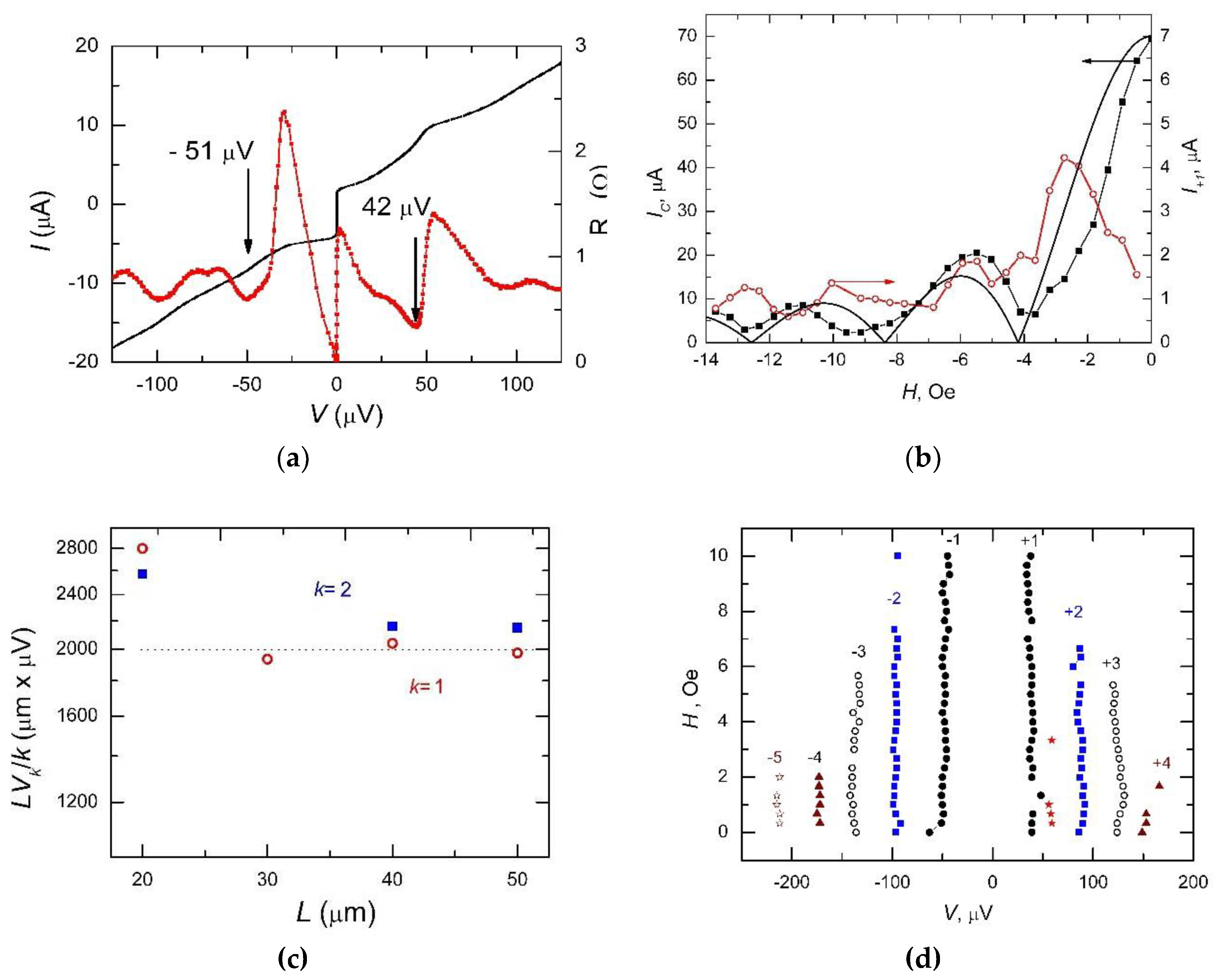

3.4. Resonance steps

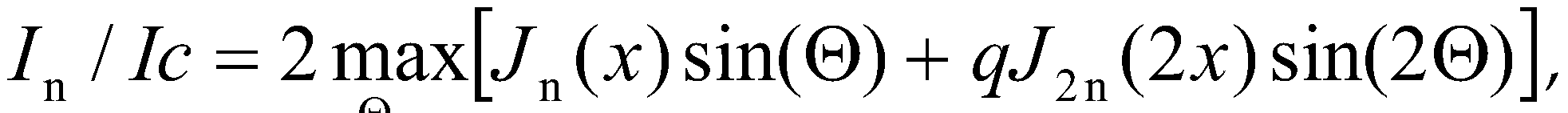

3.5. Determination of the 2nd harmonic from CPR.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bergeret, F. S.; Volkov, A. F.; Efetov, K. B. Long-Range Proximity Effects in Superconductor-Ferromagnet Structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001, 86(18), 4096–4099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, J. W. A.; Witt, J. D. S.; Blamire, M. G. Controlled Injection of Spin-Triplet Supercurrents into a Strong Ferromagnet. Science 2010, 329(5987), 59–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houzet, M.; Buzdin, A. I. Long Range Triplet Josephson Effect through a Ferromagnetic Trilayer. Phys. Rev. B 2007, 76(6), 060504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trifunovic, L. Long-Range Superharmonic Josephson Current. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 107(4), 047001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richard, C.; Houzet, M.; Meyer, J. S. Superharmonic Long-Range Triplet Current in a Diffusive Josephson Junction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 110(21), 217004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosnin, I.; Cho, H.; Petrashov, V. T.; Volkov, A. F. Superconducting Phase Coherent Electron Transport in Proximity Conical Ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 96(15), 157002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, M. S.; Czeschka, F.; Hesselberth, M.; Porcu, M.; Aarts, J. Long-Range Supercurrents through Half-Metallic Ferromagnetic CrO2. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 82(10), 100501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keizer, R. S.; Goennenwein, S. T. B.; Klapwijk, T. M.; Miao, G.; Xiao, G.; Gupta, A. A Spin Triplet Supercurrent through the Half-Metallic Ferromagnet CrO2. Nature 2006, 439(7078), 825–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Singh, M.; Tian, M.; Kumar, N.; Liu, B.; Shi, C.; Jain, J. K.; Samarth, N.; Mallouk, T. E.; Chan, M. H. W. Interplay between Superconductivity and Ferromagnetism in Crystalline Nanowires. Nat. Phys. 2010, 6(5), 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprungmann, D.; Westerholt, K.; Zabel, H.; Weides, M.; Kohlstedt, H. Evidence for Triplet Superconductivity in Josephson Junctions with Barriers of the Ferromagnetic Heusler Alloy Cu2MnAl. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 82(6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klose, C.; Khaire, T. S.; Wang, Y.; Pratt, W. P.; Birge, N. O.; McMorran, B. J.; Ginley, T. P.; Borchers, J. A.; Kirby, B. J.; Maranville, B. B.; Unguris, J. Optimization of Spin-Triplet Supercurrent in Ferromagnetic Josephson Junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108(12). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaire, T. S.; Khasawneh, M. A.; Pratt, W. P.; Birge, N. O. Observation of Spin-Triplet Superconductivity in Co-Based Josephson Junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 104(13). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bousquet, E.; Dawber, M.; Stucki, N.; Lichtensteiger, C.; Hermet, P.; Gariglio, S.; Triscone, J.-M.; Ghosez, P. Improper Ferroelectricity in Perovskite Oxide Artificial Superlattices. Nature 2008, 452(7188), 732–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohta, H.; Kim, S.; Mune, Y.; Mizoguchi, T.; Nomura, K.; Ohta, S.; Nomura, T.; Nakanishi, Y.; Ikuhara, Y.; Hirano, M.; Hosono, H.; Koumoto, K. Giant Thermoelectric Seebeck Coefficient of a Two-Dimensional Electron Gas in SrTiO3. Nat. Mater. 2007, 6(2), 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohtomo, A.; Hwang, H. Y. A High-Mobility Electron Gas at the LaAlO3/SrTiO3 Heterointerface. Nature 2004, 427(6973), 423–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. Z.; Trier, F.; Wijnands, T.; Green, R. J.; Gauquelin, N.; Egoavil, R.; Christensen, D. V.; Koster, G.; Huijben, M.; Bovet, N.; Macke, S.; He, F.; Sutarto, R.; Andersen, N. H.; Sulpizio, J. A.; Honig, M.; Prawiroatmodjo, G. E. D. K.; Jespersen, T. S.; Linderoth, S.; Ilani, S.; Verbeeck, J.; Van Tendeloo, G.; Rijnders, G.; Sawatzky, G. A.; Pryds, N. Extreme Mobility Enhancement of Two-Dimensional Electron Gases at Oxide Interfaces by Charge-Transfer-Induced Modulation Doping. Nat. Mater. 2015, 14(8), 801–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trier, F.; Prawiroatmodjo, G. E. D. K.; Zhong, Z.; Christensen, D. V.; von Soosten, M.; Bhowmik, A.; Lastra, J. M. G.; Chen, Y.; Jespersen, T. S.; Pryds, N. Quantization of Hall Resistance at the Metallic Interface between an Oxide Insulator and SrTiO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 117(9), 096804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagotto, E.; Hotta, T.; Moreo, A. Colossal Magnetoresistant Materials: The Key Role of Phase Separation. Phys. Rep. 2001, 344(1–3), 1–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalcheim, Y.; Kirzhner, T.; Koren, G.; Millo, O. Long-Range Proximity Effect in La2/3Ca1/3MnO3/(100)YBa2Cu3O7 − δ Ferromagnet/Superconductor Bilayers: Evidence for Induced Triplet Superconductivity in the Ferromagnet. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 83(6), 064510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visani, C.; Sefrioui, Z.; Tornos, J.; Leon, C.; Briatico, J.; Bibes, M.; Barthélémy, A.; Santamaría, J.; Villegas, J. E. Equal-Spin Andreev Reflection and Long-Range Coherent Transport in High-Temperature Superconductor/Half-Metallic Ferromagnet Junctions. Nat. Phys. 2012, 8(7), 539–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zalk, M.; Brinkman, A.; Aarts, J.; Hilgenkamp, H. Interface Resistance of YBa2Cu3O7 − δ / La0.67Sr0.33MnO3 Ramp-Type Contacts. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 82(13), 134513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrzhik, A. M.; Ovsyannikov, G. A.; Shadrin, A. V.; Konstantinyan, K. I.; Zaitsev, A. V.; Demidov, V. V.; Kislinskii, Yu. V. Electron Transport in Hybrid Superconductor Heterostructures with Manganite Interlayers. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. 2011, 112(6), 1042–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkov, A. F.; Efetov, K. B. Odd Spin-Triplet Superconductivity in a Multilayered Superconductor-Ferromagnet Josephson Junction. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 81(14), 144522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasawneh, M. A.; Khaire, T. S.; Klose, C.; Pratt Jr, W. P.; Birge, N. O. Spin-Triplet Supercurrent in Co-Based Josephson Junctions. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2011, 24(2), 024005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leksin, P. V.; Garif’yanov, N. N.; Garifullin, I. A.; Fominov, Ya. V.; Schumann, J.; Krupskaya, Y.; Kataev, V.; Schmidt, O. G.; Büchner, B. Evidence for Triplet Superconductivity in a Superconductor-Ferromagnet Spin Valve. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 109(5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zdravkov, V. I.; Kehrle, J.; Obermeier, G.; Lenk, D.; Krug von Nidda, H.-A.; Müller, C.; Kupriyanov, M. Yu.; Sidorenko, A. S.; Horn, S.; Tidecks, R.; Tagirov, L. R. Experimental Observation of the Triplet Spin-Valve Effect in a Superconductor-Ferromagnet Heterostructure. Phys. Rev. B 2013, 87(14), 144507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trifunovic, L.; Popović, Z.; Radović, Z. Josephson Effect and Spin-Triplet Pairing Correlations in S F1 F2 S Junctions. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 84(6), 064511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperstad, I. B.; Linder, J.; Sudbø, A. Josephson Current in Diffusive Multilayer Superconductor/Ferromagnet/Superconductor Junctions. Phys. Rev. B 2008, 78(10), 104509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knežević, M.; Trifunovic, L.; Radović, Z. Signature of the Long Range Triplet Proximity Effect in the Density of States. Phys. Rev. B 2012, 85(9), 094517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, A.; Barber, Z. H.; Robinson, J. W. A.; Blamire, M. G. Pure Second Harmonic Current-Phase Relation in Spin-Filter Josephson Junctions. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5(1), 3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovsyannikov, G. A.; Sheyerman, A. E.; Shadrin, A. V.; Kislinskii, Yu. V.; Constantinian, K. Y.; Kalabukhov, A. Triplet Superconducting Correlations in Oxide Heterostructures with a Composite Ferromagnetic Interlayer. JETP Lett. 2013, 97(3), 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaydukov, Yu. N.; Ovsyannikov, G. A.; Sheyerman, A. E.; Constantinian, K. Y.; Mustafa, L.; Keller, T.; Uribe-Laverde, M. A.; Kislinskii, Yu. V.; Shadrin, A. V.; Kalaboukhov, A.; Keimer, B.; Winkler, D. Evidence for Spin-Triplet Superconducting Correlations in Metal-Oxide Heterostructures with Noncollinear Magnetization. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 90(3), 035130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheyerman, A.; Ovsyannikov, G.; Kislinskii, Y.; Constantinian, K.; Shadrin, A. Current-Phase Relation of Superconductor-Ferromagnet-Superconductor Junctions with a Composite Interlayer. Solid State Phenom. 2015, 233–234, 737–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheyerman, A. E.; Constantinian, K. Y.; Ovsyannikov, G. A.; Kislinskii, Yu. V.; Shadrin, A. V.; Kalabukhov, A. V.; Khaydukov, Yu. N. Spin-Triplet Electron Transport in Hybrid Superconductor Heterostructures with a Composite Ferromagnetic Interlayer. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. 2015, 120(6), 1024–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovsyannikov, G. A.; Constantinian, K. Y.; Demidov, V. V.; Khaydukov, Yu. N. Magnetic Proximity Effect and Superconducting Triplet Correlations at the Cuprate Superconductor and Oxide Spin Valve Interface. Low Temp. Phys. 2016, 42(10), 873–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinian, K.; Ovsyannikov, G.; Kislinskii, Y.; Sheyerman, A.; Shadrin, A.; Kalabukhov, A.; Mustafa, L.; Khaydukov, Y.; Winkler, D. Spin-Triplet Superconducting Current in Metal-Oxide Heterostructures with Composite Ferromagnetic Interlayer. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2016, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eschrig, M. Spin-Polarized Supercurrents for Spintronics: A Review of Current Progress. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2015, 78(10), 104501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, J.; Robinson, J. W. A. Superconducting Spintronics. Nat. Phys. 2015, 11(4), 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsdal, M.; Khaliullin, G.; Hyart, T.; Rosenow, B. Enhancing Triplet Superconductivity by the Proximity to a Singlet Superconductor in Oxide Heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 93(22), 220502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergeret, F. S.; Tokatly, I. V. Spin-Orbit Coupling as a Source of Long-Range Triplet Proximity Effect in Superconductor-Ferromagnet Hybrid Structures. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 89(13), 134517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, S. H.; Linder, J. Giant Triplet Proximity Effect in π-Biased Josephson Junctions with Spin-Orbit Coupling. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 92(2), 024501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konschelle, F. Transport Equations for Superconductors in the Presence of Spin Interaction. Eur. Phys. J. B 2014, 87(5), 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergeret, F. S.; Volkov, A. F.; Efetov, K. B. Odd Triplet Superconductivity and Related Phenomena in Superconductor-Ferromagnet Structures. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2005, 77(4), 1321–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobkova, I. V.; Bobkov, A. M. Quasiclassical Theory of Magnetoelectric Effects in Superconducting Heterostructures in the Presence of Spin-Orbit Coupling. Phys. Rev. B 2017, 95(18), 184518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeg, C. R.; Maslov, D. L. Proximity-Induced Triplet Superconductivity in Rashba Materials. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 92(13), 134512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yano, R.; Koyanagi, M.; Kashiwaya, H.; Tsumura, K.; Hirose, H. T.; Sasagawa, T.; Asano, Y.; Kashiwaya, S. Unusual Superconducting Proximity Effect in Magnetically Doped Topological Josephson Junctions. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2020, 89(3), 034702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sau, J. D.; Lutchyn, R. M.; Tewari, S.; Das Sarma, S. Generic New Platform for Topological Quantum Computation Using Semiconductor Heterostructures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 104(4), 040502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suominen, H. J.; Danon, J.; Kjaergaard, M.; Flensberg, K.; Shabani, J.; Palmstrøm, C. J.; Nichele, F.; Marcus, C. M. Anomalous Fraunhofer Interference in Epitaxial Superconductor-Semiconductor Josephson Junctions. Phys. Rev. B 2017, 95(3), 035307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, F.; Kashuba, O.; Bocquillon, E.; Wiedenmann, J.; Deacon, R. S.; Klapwijk, T. M.; Platero, G.; Molenkamp, L. W.; Trauzettel, B.; Hankiewicz, E. M. Josephson Junction Dynamics in the Presence of 2 π - and 4 π - Periodic Supercurrents. Phys. Rev. B 2017, 95(19), 195430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedenmann, J.; Bocquillon, E.; Deacon, R. S.; Hartinger, S.; Herrmann, O.; Klapwijk, T. M.; Maier, L.; Ames, C.; Brüne, C.; Gould, C.; Oiwa, A.; Ishibashi, K.; Tarucha, S.; Buhmann, H.; Molenkamp, L. W. 4π-Periodic Josephson Supercurrent in HgTe-Based Topological Josephson Junctions. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7(1), 10303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedder, C. J.; Meng, T.; Tiwari, R. P.; Schmidt, T. L. Missing Shapiro Steps and the 8 π -Periodic Josephson Effect in Interacting Helical Electron Systems. Phys. Rev. B 2017, 96(16), 165429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S. J.; Jin, H.; Kim, K. W.; Choi, W. S.; Lee, Y. S.; Yu, J.; Cao, G.; Sumi, A.; Funakubo, H.; Bernhard, C.; Noh, T. W. Dimensionality-Controlled Insulator-Metal Transition and Correlated Metallic State in 5 d Transition Metal Oxides Srn + 1IrnO3n + 1 ( n = 1, 2, and ∞ ). Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 101(22), 226402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witczak-Krempa, W.; Chen, G.; Kim, Y. B.; Balents, L. Correlated Quantum Phenomena in the Strong Spin-Orbit Regime. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 2014, 5(1), 57–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffer, R.; Kin-Ho Lee, E.; Yang, B.-J.; Kim, Y. B. Recent Progress on Correlated Electron Systems with Strong Spin–Orbit Coupling. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2016, 79(9), 094504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, E. E.; Xiang, H.; Köhler, J.; Whangbo, M.-H. Spin Orientations of the Spin-Half Ir 4+ Ions in Sr3NiIrO6, Sr2IrO4, and Na2IrO3 : Density Functional, Perturbation Theory, and Madelung Potential Analyses. J. Chem. Phys. 2016, 144(11), 114706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gim, Y.; Sethi, A.; Zhao, Q.; Mitchell, J. F.; Cao, G.; Cooper, S. L. Isotropic and Anisotropic Regimes of the Field-Dependent Spin Dynamics in Sr2IrO4 : Raman Scattering Studies. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 93(2), 024405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. K.; Sung, N. H.; Denlinger, J. D.; Kim, B. J. Observation of a D-Wave Gap in Electron-Doped Sr2IrO4. Nat. Phys. 2016, 12(1), 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hikino, S. Magnetization Reversal by Tuning Rashba Spin–Orbit Interaction and Josephson Phase in a Ferromagnetic Josephson Junction. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2018, 87(7), 074707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovsyannikov, G. A.; Grishin, A. S.; Constantinian, K. Y.; Shadrin, A. V.; Petrzhik, A. M.; Kislinskii, Yu. V.; Cristiani, G.; Logvenov, G. Superconducting Heterostructures Interlayered with a Material with Strong Spin–Orbit Interaction. Phys. Solid State 2018, 60(11), 2166–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrzhik, A. M.; Cristiani, G.; Logvenov, G.; Pestun, A. E.; Andreev, N. V.; Kislinskii, Yu. V.; Ovsyannikov, G. A. Growth Technology and Characteristics of Thin Strontium Iridate Films and Iridate–Cuprate Superconductor Heterostructures. Tech. Phys. Lett. 2017, 43(6), 554–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yu, S.-L.; Li, J.-X. Fermi Arcs, Pseudogap, and Collective Excitations in Doped Sr2IrO4: A Generalized Fluctuation Exchange Study. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 91(16), 165138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takei, S.; Fregoso, B. M.; Galitski, V.; Das Sarma, S. Topological Superconductivity and Majorana Fermions in Hybrid Structures Involving Cuprate High-Tc Superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 2013, 87(1), 014504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Kee, H.-Y. Helical Majorana Fermions and Flat Edge States in the Heterostructures of Iridates and High-TC Cuprates. Phys. Rev. B 2018, 97(8), 085155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrzhik, A. M.; Constantinian, K. Y.; Ovsyannikov, G. A.; Zaitsev, A. V.; Shadrin, A. V.; Grishin, A. S.; Kislinski, Yu. V.; Cristiani, G.; Logvenov, G. Superconducting Current and Low-Energy States in a Mesa-Heterostructure Interlayered with a Strontium Iridate Film with Strong Spin-Orbit Interaction. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 100(2), 024501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komissinskiy, P.; Ovsyannikov, G. A.; Constantinian, K. Y.; Kislinski, Y. V.; Borisenko, I. V.; Soloviev, I. I.; Kornev, V. K.; Goldobin, E.; Winkler, D. High-Frequency Dynamics of Hybrid Oxide Josephson Heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 2008, 78(2), 024501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovsyannikov, G. A.; Petrzhik, A. M.; Borisenko, I. V.; Klimov, A. A.; Ignatov, Yu. A.; Demidov, V. V.; Nikitov, S. A. Magnetotransport Characteristics of Strained La0.7Sr0.3MnO3 Epitaxial Manganite Films. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. 2009, 108(1), 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izyumov, Y. A.; Skryabin, Y. N. Double Exchange Model and the Unique Properties of the Manganites. Phys.-Uspekhi 2001, 44(2), 109–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Santoro, A.; Lynn, J. W.; Erwin, R. W.; Borchers, J. A.; Peng, J. L.; Greene, R. L. Structure and Magnetic Order in Undoped Lanthanum Manganite. Phys. Rev. B 1997, 55(22), 14987–14999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fita, I. M.; Szymczak, R.; Baran, M.; Markovich, V.; Puzniak, R.; Wisniewski, A.; Shiryaev, S. V.; Varyukhin, V. N.; Szymczak, H. Evolution of Ferromagnetic Order in LaMnO3.05 Single Crystals: Common Origin of Both Pressure and Self-Doping Effects. Phys. Rev. B 2003, 68(1), 014436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mieville, L.; Worledge, D.; Geballe, T. H.; Contreras, R.; Char, K. Transport across Conducting Ferromagnetic Oxide/Metal Interfaces. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1998, 73(12), 1736–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinian, K. Y.; Ovsyannikov, G. A.; Shadrin, A. V.; Kislinski, Y. V.; Petrzhik, A. M.; Kalaboukhov, A. S. Hybrid superconducting heterostructures with magnetic interlayers. Radioelectron. Nanosyst. Inf. Technol. 2021, 13(4), 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashiwaya, S.; Tanaka, Y. Tunnelling Effects on Surface Bound States in Unconventional Superconductors. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2000, 63(10), 1641–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petković, I.; Aprili, M.; . Barnes, S. E.; Beuneu, F.; Maekawa, S. Direct dynamical coupling of spin modes and singlet Josephson supercurrent in ferromagnetic Josephson junctions. Phys. Rev. B 2009, 80(22), 220502(R). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryazanov, V. V.; Oboznov, V. A.; Rusanov, A. Yu.; Veretennikov, A. V.; Golubov, A. A.; Aarts, J. Coupling of Two Superconductors through a Ferromagnet: Evidence for a Junction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001, 86(11), 2427–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohn, J. L.; Neumeier, J. J.; Popoviciu, C. P.; McClellan, K. J.; Leventouri, Th. Local Lattice Distortions and Thermal Transport in Perovskite Manganites. Phys. Rev. B 1997, 56(14), R8495–R8498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostic, P.; Okada, Y.; Collins, N. C.; Schlesinger, Z.; Reiner, J. W.; Klein, L.; Kapitulnik, A.; Geballe, T. H.; Beasley, M. R. Non-Fermi-Liquid Behavior of SrRuO 3 : Evidence from Infrared Conductivity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1998, 81(12), 2498–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodfield, B. F.; Wilson, M. L.; Byers, J. M. Low-Temperature Specific Heat of La1-xSrxMnO3+δ. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997, 78(16). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asulin, I.; Yuli, O.; Koren, G.; Millo, O. Evidence for Induced Magnetization in Superconductor-Ferromagnet Heterostructures: A Scanning Tunneling Spectroscopy Study. Phys. Rev. B 2009, 79(17), 174524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonio Barone, G. P. Physics and Applications of the Josephson Effect; Wiley: New York, 2005. Wiley: New York.

- Constantinian, K. Y.; Ovsyannikov, G. A.; Petrzhik, A. M.; Shadrin, A. V.; Kislinskii, Yu. V.; Cristiani, G.; Logvenov, G. Resonant Current Steps in Josephson Structures with a Layer from a Material with Strong Spin–Orbit Interaction. Phys. Solid State 2020, 62(9), 1549–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinian, K. Y.; Petrzhik, A. M.; Ovsyannikov, G. A.; Shadrin, A. V.; Kislinskii, Y. V.; Cristiani, G.; Logvenov, G. Superconducting Heterostructure with Barrier with Strong Spin-Orbit Interaction. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1559(1), 012023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silaev, M. A.; Tokatly, I. V.; Bergeret, F. S. Anomalous Current in Diffusive Ferromagnetic Josephson Junctions. Phys. Rev. B 2017, 95(18), 184508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, S.; Pajerowski, D. M.; Stone, M. B.; May, A. F. Spin-Gap and Two-Dimensional Magnetic Excitations in Sr2IrO4. Phys. Rev. B 2018, 98(22), 220402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, S.; Kandelaki, E.; Volkov, A. F.; Efetov, K. B. Interaction of Josephson and Magnetic Oscillations in Josephson Tunnel Junctions with a Ferromagnetic Layer. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 84(14), 144519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hikino, S.; Mori, M.; Maekawa, S. Zero-Field Fiske Resonance Coupled with Spin-Waves in Ferromagnetic Josephson Junctions. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2014, 83(7), 074704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komissinski, P. V.; Il’ichev, E.; Ovsyannikov, G. A.; Kovtonyuk, S. A.; Grajcar, M.; Hlubina, R.; Ivanov, Z.; Tanaka, Y.; Yoshida, N.; Kashiwaya, S. Observation of the Second Harmonic in Superconducting Current-Phase Relation of Nb/Au/(001)YBa2Cu3Ox Heterojunctions. Europhys. Lett. EPL 2002, 57(4), 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blais, A.; Zagoskin, A. M. Operation of Universal Gates in a Solid-State Quantum Computer Based on Clean Josephson Junctions between d - Wave Superconductors. Phys. Rev. A 2000, 61(4), 042308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y.; Kashiwaya, S. Theory of the Josephson Effect in d -Wave Superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 53(18), R11957–R11960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldobin, E.; Koelle, D.; Kleiner, R.; Buzdin, A. Josephson Junctions with Second Harmonic in the Current-Phase Relation: Properties of φ Junctions. Phys. Rev. B 2007, 76(22), 224523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrzhik, A. M.; Ovsyannikov, G. A.; Shadrin, A. V.; Konstantinyan, K. I.; Zaitsev, A. V.; Demidov, V. V.; Kislinskii, Yu. V. Electron Transport in Hybrid Superconductor Heterostructures with Manganite Interlayers. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. 2011, 112(6), 1042–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korneta, O. B.; Qi, T.; Chikara, S.; Parkin, S.; De Long, L. E.; Schlottmann, P.; Cao, G. Electron-Doped Sr2IrO4 − δ ( 0 ≤ δ ≤ 0.04 ) : Evolution of a Disordered Jeff = 1/2 Mott Insulator into an Exotic Metallic State. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 82(11), 115117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsdal, M.; Hyart, T. Robust Semi-Dirac Points and Unconventional Topological Phase Transitions in Doped Superconducting Sr2IrO4 Tunnel Coupled to t2g Electron Systems. SciPost Phys. 2017, 3(6), 041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, P.; Siegel, M.; Heinz, E. Microwave-Induced Steps in High-Tc Josephson Junctions. Phys. C Supercond. 1991, 180(1–4), 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coon, D. D.; Fiske, M. D. Josephson Ac and Step Structure in the Supercurrent Tunneling Characteristic. Phys. Rev. 1965, 138(3A), A744–A746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, G.; Probst, C.; Marx, A.; Gross, R. Josephson Coupling and Fiske Dynamics in Ferromagnetic Tunnel Junctions. Eur. Phys. J. B 2010, 78(4), 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, J.; Kemmler, M.; Koelle, D.; Kleiner, R.; Goldobin, E.; Weides, M.; Feofanov, A. K.; Lisenfeld, J.; Ustinov, A. V. Static and Dynamic Properties of 0, π, and 0 − π Ferromagnetic Josephson Tunnel Junctions. Phys. Rev. B 2008, 77(21), 214506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- I.O. Kulik. JETP Lett. 1965, 2 (84).

- J. C. Swihart. J. Appl. Phys. 1961, 32 (461).

- Boardman, A. D.; Nikitov, S. A.; Waby, N. A. Existence of Spin-Wave Solitons in an Antiferromagnetic Film. Phys. Rev. B 1993, 48(18), 13602–13606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahr, S.; Alfonsov, A.; Jackeli, G.; Khaliullin, G.; Matsumoto, A.; Takayama, T.; Takagi, H.; Büchner, B.; Kataev, V. Low-Energy Magnetic Excitations in the Spin-Orbital Mott Insulator Sr 2 IrO 4. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 89(18), 180401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaco, R.; Costabile, G.; Martucciello, N. Influence of the Idle Region on the Dynamic Properties of Window Josephson Tunnel Junctions. J. Appl. Phys. 1995, 77(5), 2073–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikara, S.; Korneta, O.; Crummett, W. P.; DeLong, L. E.; Schlottmann, P.; Cao, G. Giant Magnetoelectric Effect in the Jeff = 1/2 Mott Insulator Sr2IrO4. Phys. Rev. B 2009, 80(14), 140407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J. Microscopic Origin of Magnetoelectric Coupling in Noncollinear Multiferroics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100(7), 140407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komissinskiy, P.; Ovsyannikov, G. A.; Borisenko, I. V.; Kislinskii, Yu. V.; Constantinian, K. Y.; Zaitsev, A. V.; Winkler, D. Josephson Effect in Hybrid Oxide Heterostructures with an Antiferromagnetic Layer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 99(1), 017004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barash, Yu. S. Quasiparticle Interface States in Junctions Involving d -Wave Superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 2000, 61(1), 678–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löfwander, T.; Shumeiko, V. S.; Wendin, G. Andreev Bound States in High- T c Superconducting Junctions. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2001, 14(5), R53–R77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedel, R. A.; Bagwell, P. F. Low-Temperature Josephson Current Peak in Junctions with d -Wave Order Parameters. Phys. Rev. B 1998, 57(10), 6084–6089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Quindeau, A.; Deniz, H.; Preziosi, D.; Hesse, D.; Alexe, M. Crossover of Conduction Mechanism in Sr2IrO4 Epitaxial Thin Films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 105(8), 082407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gor’kov, L.; Kresin, V. Giant Magnetic Effects and Oscillations in Antiferromagnetic Josephson Weak Links. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2001, 78(23), 3657–3659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornev, V. K.; Karminskaya, T. Y.; Kislinskii, Y. V.; Komissinki, P. V.; Constantinian, K. Y.; Ovsyannikov, G. A. Dynamics of Underdamped Josephson Junctions with Non-Sinusoidal Current-Phase Relation. Phys. C Supercond. Its Appl. 2006, 435(1–2), 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number | dSRO, nm | dLSMO, nm | L, μm | RNS, μΩcm2 | jC A/cm2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 14 | 0 | 20 | 0.11 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 2 | 20 | 120 | 0 |

| 3 | 4.5 | 3 | 50 | 0.45 | 0.75 |

| 4 | 8.5 | 3 | 10 | 0.13 | 25 |

| 5 | 8.5 | 6 | 10 | 0.16 | 88 |

| 6 | 5.6 | 15 | 50 | 0.20 | 1.1 |

| 7 | 10 | 9 | 30 | 0.15 | 2.2 |

| Number | L, μm | RNS, μΩcm2 | jC, A/cm2 | ICRN,μV | λJ,μm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 50 | 125 | 0.75 | 32 | 725 |

| 2 | 40 | 114 | 25 | 43 | 600 |

| 3 | 30 | 94 | 88 | 31 | 645 |

| 4 | 20 | 83 | 13 | 10 | 1065 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).