Submitted:

06 May 2023

Posted:

08 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

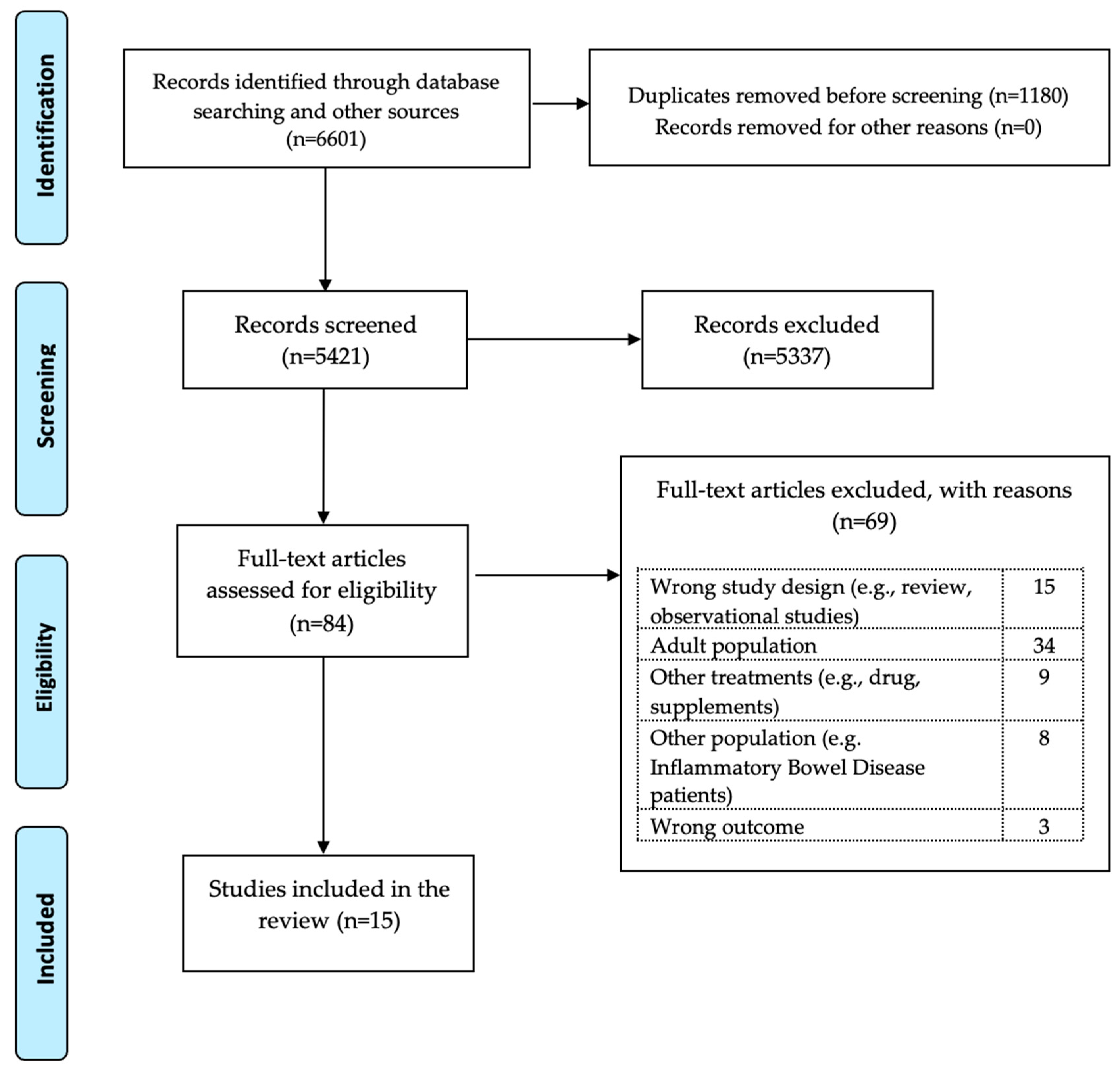

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

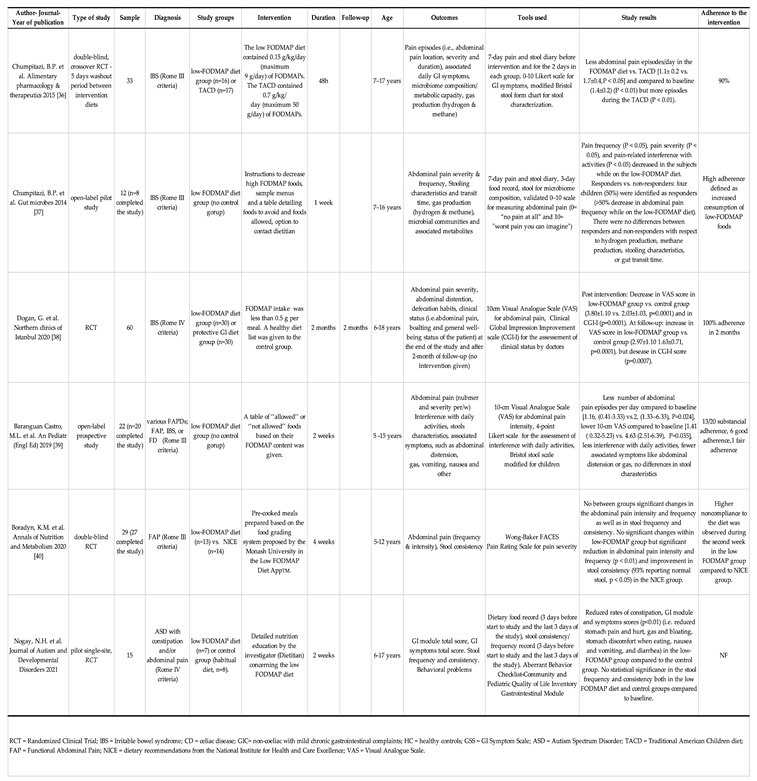

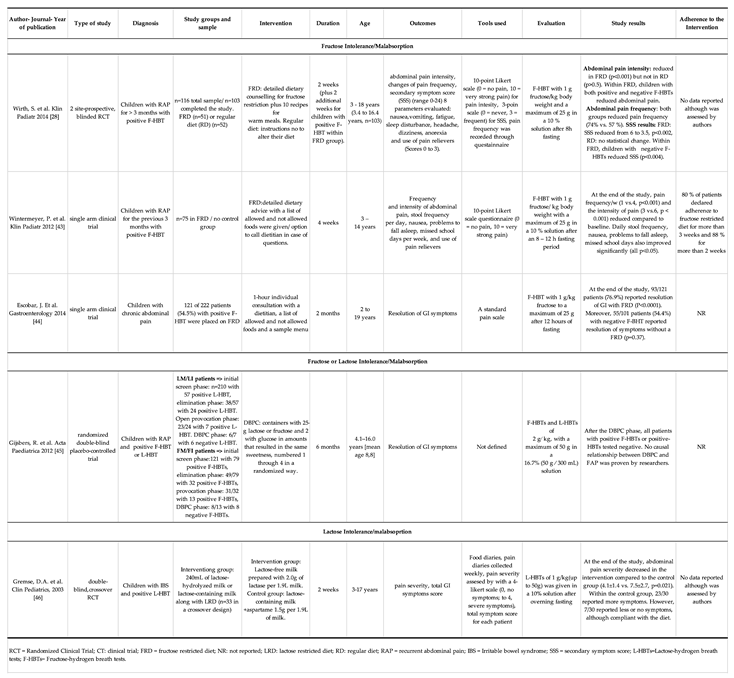

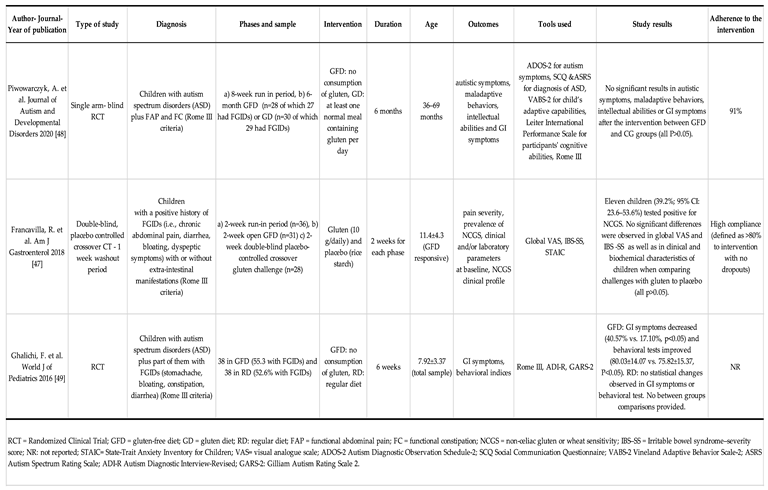

2.2. Data extraction

2.3. Outcome Measured

2.4. Study Quality

3. Results

3.1. Low-FODMAP diet

3.2. Fructose restricted diet

3.3. Gluten Free diet

3.4. Mediterranean diet

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of the primary and secontary outcomes

4.2. Literature documention

4.3. Strengths and limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lewis, M.L.; Palsson, O.S.; Whitehead, W.E.; van Tilburg, M.A. Prevalence of functional gastrointestinal disorders in children and adolescents. The Journal of pediatrics 2016, 177, 39–43.e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baaleman, D.F.; Di Lorenzo, C.; Benninga, M.A.; Saps, M. The Effects of the Rome IV Criteria on Pediatric Gastrointestinal Practice. Current Gastroenterology Reports 2020, 22, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robin, S.G.; Keller, C.; Zwiener, R.; Hyman, P.E.; Nurko, S.; Saps, M.; Di Lorenzo, C.; Shulman, R.J.; Hyams, J.S.; Palsson, O. Prevalence of pediatric functional gastrointestinal disorders utilizing the Rome IV criteria. The Journal of pediatrics 2018, 195, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyams, J.S.; Di Lorenzo, C.; Saps, M.; Shulman, R.J.; Staiano, A.; van Tilburg, M. Childhood functional gastrointestinal disorders: child/adolescent. Gastroenterology 2016, 150, 1456–1468.e1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyman, P.E.; Milla, P.J.; Benninga, M.A.; Davidson, G.P.; Fleisher, D.F.; Taminiau, J. Childhood functional gastrointestinal disorders: neonate/toddler. Gastroenterology 2006, 130, 1519–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasquin, A.; Di Lorenzo, C.; Forbes, D.; Guiraldes, E.; Hyams, J.S.; Staiano, A.; Walker, L.S. Childhood functional gastrointestinal disorders: child/adolescent. Gastroenterology 2006, 130, 1527–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernon-Roberts, A.; Alexander, I.; Day, A.S. Systematic Review of Pediatric Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders (Rome IV Criteria). J Clin Med 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boronat, A.C.; Ferreira-Maia, A.P.; Matijasevich, A.; Wang, Y.-P. Epidemiology of functional gastrointestinal disorders in children and adolescents: a systematic review. World Journal of Gastroenterology 2017, 23, 3915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strisciuglio, C.; Cenni, S.; Serra, M.R.; Dolce, P.; Kolacek, S.; Sila, S.; Trivic, I.; Bar Lev, M.R.; Shamir, R.; Kostovski, A. , et al. Diet and Pediatric Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders in Mediterranean Countries. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drossman, D.A. Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: History, Pathophysiology, Clinical Features, and Rome IV. Gastroenterology 2016, 150, 1262–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M.; Carlson, P.; McKinzie, S.; Zucchelli, M.; D'Amato, M.; Busciglio, I.; Burton, D.; Zinsmeister, A.R. Genetic susceptibility to inflammation and colonic transit in lower functional gastrointestinal disorders: preliminary analysis. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2011, 23, 935–e398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, E.A.; Ryu, H.J.; Bhatt, R.R. The neurobiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Mol Psychiatry 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azpiroz, F.; Bouin, M.; Camilleri, M.; Mayer, E.A.; Poitras, P.; Serra, J.; Spiller, R.C. Mechanisms of hypersensitivity in IBS and functional disorders. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2007, 19, 62–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, G.L.; Hoedt, E.C.; Walker, M.M.; Talley, N.J.; Keely, S. Physiological mechanisms of unexplained (functional) gastrointestinal disorders. The Journal of Physiology 2021, 599, 5141–5161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Palma, G.; Collins, S.M.; Bercik, P. The microbiota-gut-brain axis in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gut Microbes 2014, 5, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koloski, N.; Holtmann, G.; Talley, N.J. Is there a causal link between psychological disorders and functional gastrointestinal disorders? Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020, 14, 1047–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Defrees, D.N.; Bailey, J. Irritable bowel syndrome: epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Primary Care: Clinics in Office Practice 2017, 44, 655–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco-Benítez, C.A.; Gómez-Oliveros, L.F.; Rubio-Molina, L.M.; Tovar-Cuevas, J.R.; Saps, M. Diagnostic Accuracy of the Rome IV Criteria for the Diagnosis of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders in Children. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 2021, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, A.; Dziechciarz, P.; Szajewska, H. Systematic review of randomized controlled trials: fiber supplements for abdominal pain-related functional gastrointestinal disorders in childhood. Ann Nutr Metab 2012, 61, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capozza, M.; Laforgia, N.; Rizzo, V.; Salvatore, S.; Guandalini, S.; Baldassarre, M. Probiotics and Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders in Pediatric Age: A Narrative Review. Front Pediatr 2022, 10, 805466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyams, J.S.; Di Lorenzo, C.; Saps, M.; Shulman, R.J.; Staiano, A.; van Tilburg, M. Childhood Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: Child/Adolescent. Gastroenterology 2016, 150, 1456–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palermo, T.M. Pain prevention and management must begin in childhood: the key role of psychological interventions. Pain 2020, 161, S114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinn, D.; Aroniadis, O.; Brandt, L. Is fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) an effective treatment for patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGID)? Neurogastroenterology & Motility 2015, 27, 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla, S.; Nurko, S. Focus on the use of antidepressants to treat pediatric functional abdominal pain: current perspectives. Clinical and experimental gastroenterology 2018, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korterink, J.J.; Rutten, J.M.; Venmans, L.; Benninga, M.A.; Tabbers, M.M. Pharmacologic treatment in pediatric functional abdominal pain disorders: a systematic review. The Journal of pediatrics 2015, 166, 424–431.e426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Zogg, H.; Ghoshal, U.C.; Ro, S. Current Treatment Options and Therapeutic Insights for Gastrointestinal Dysmotility and Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 808195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuck, C.J.; Reed, D.E.; Muir, J.G.; Vanner, S.J. Implementation of the low FODMAP diet in functional gastrointestinal symptoms: A real-world experience. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2020, 32, e13730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirth, S.; Klodt, C.; Wintermeyer, P.; Berrang, J.; Hensel, K.; Langer, T.; Heusch, A. Positive or negative fructose breath test results do not predict response to fructose restricted diet in children with recurrent abdominal pain: results from a prospective randomized trial. Klinische Pädiatrie 2014, 226, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rej, A.; Avery, A.; Aziz, I.; Black, C.J.; Bowyer, R.K.; Buckle, R.L.; Seamark, L.; Shaw, C.C.; Thompson, J.; Trott, N. , et al. Diet and irritable bowel syndrome: an update from a UK consensus meeting. BMC Medicine 2022, 20, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenni, S.; Sesenna, V.; Boiardi, G.; Casertano, M.; Di Nardo, G.; Esposito, S.; Strisciuglio, C. The Mediterranean Diet in Paediatric Gastrointestinal Disorders. Nutrients 2023, 15, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Annals of internal medicine 2009, 151, W-65–W-94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. bmj 2016, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.; Hernán, M.A.; McAleenan, A.; Reeves, B.C.; Higgins, J.P. Assessing risk of bias in a non-randomized study. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions 2019, 621–641. [Google Scholar]

- Sterne, J.A.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. bmj 2019, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.; Li, T.; Sterne, J. Revised Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2): Additional considerations for crossover trials. Cochrane Methods 2021, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chumpitazi, B.P.; Cope, J.L.; Hollister, E.B.; Tsai, C.M.; McMeans, A.R.; Luna, R.A.; Versalovic, J.; Shulman, R.J. Randomised clinical trial: gut microbiome biomarkers are associated with clinical response to a low FODMAP diet in children with the irritable bowel syndrome. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics 2015, 42, 418–427. [Google Scholar]

- Chumpitazi, B.P.; Hollister, E.B.; Oezguen, N.; Tsai, C.M.; McMeans, A.R.; Luna, R.A.; Savidge, T.C.; Versalovic, J.; Shulman, R.J. Gut microbiota influences low fermentable substrate diet efficacy in children with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut microbes 2014, 5, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, G.; Yavuz, S.; Aslantas, H.; Ozyurt, B.; Kasirga, E. Is low FODMAP diet effective in children with irritable bowel syndrome? Northern clinics of Istanbul 2020, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Baranguan Castro, M.L.; Ros Arnal, I.; Garcia Romero, R.; Rodriguez Martinez, G.; Ubalde Sainz, E. [Implementation of a low FODMAP diet for functional abdominal pain]. An Pediatr (Engl Ed) 2019, 90, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boradyn, K.M.; Przybyłowicz, K.E.; Jarocka-Cyrta, E. Low FODMAP diet is not effective in children with functional abdominal pain: a randomized controlled trial. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism 2020, 76, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyrkot, S.; Marcon, M.; Brill, H.; Mileski, H.; Dowhaniuk, J.; Frankish, A.; Carroll, M.W.; Persad, R.; Turner, J.M.; Mager, D.R. FODMAP intake in children with coeliac disease influences diet quality and health-related quality of life and has no impact on gastrointestinal symptoms. International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition 2021, 72, 956–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogay, N.H.; Walton, J.; Roberts, K.M.; Nahikian-Nelms, M.; Witwer, A.N. The effect of the low FODMAP diet on gastrointestinal symptoms, behavioral problems and nutrient intake in children with autism spectrum disorder: A randomized controlled pilot trial. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 2021, 51, 2800–2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wintermeyer, P.; Baur, M.; Pilic, D.; Schmidt-Choudhury, A.; Zilbauer, M.; Wirth, S. Fructose malabsorption in children with recurrent abdominal pain: positive effects of dietary treatment. Klin Padiatr 2012, 224, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar Jr, M.A.; Lustig, D.; Pflugeisen, B.M.; Amoroso, P.J.; Sherif, D.; Saeed, R.; Shamdeen, S.; Tuider, J.; Abdullah, B. Fructose intolerance/malabsorption and recurrent abdominal pain in children. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition 2014, 58, 498–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gijsbers, C.F.; Kneepkens, C.M.; Buller, H.A. Lactose and fructose malabsorption in children with recurrent abdominal pain: results of double-blinded testing. Acta Paediatr 2012, 101, e411–e415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gremse, D.A.; Greer, A.S.; Vacik, J.; Dipalma, J.A. Abdominal Pain Associated with Lactose Ingestion in Children with Lactose Intolerance. Clinical Pediatrics 2003, 42, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francavilla, R.; Cristofori, F.; Verzillo, L.; Gentile, A.; Castellaneta, S.; Polloni, C.; Giorgio, V.; Verduci, E.; D'angelo, E.; Dellatte, S. Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled crossover trial for the diagnosis of non-celiac gluten sensitivity in children. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology| ACG 2018, 113, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwowarczyk, A.; Horvath, A.; Pisula, E.; Kawa, R.; Szajewska, H. Gluten-free diet in children with autism spectrum disorders: a randomized, controlled, single-blinded trial. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 2020, 50, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghalichi, F.; Ghaemmaghami, J.; Malek, A.; Ostadrahimi, A. Effect of gluten free diet on gastrointestinal and behavioral indices for children with autism spectrum disorders: a randomized clinical trial. World J Pediatr 2016, 12, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Biltagi, M.; El Amrousy, D.; El Ashry, H.; Maher, S.; Mohammed, M.A.; Hasan, S. Effects of adherence to the Mediterranean diet in children and adolescents with irritable bowel syndrome. World J Clin Pediatr 2022, 11, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, C.J.; Staudacher, H.M.; Ford, A.C. Efficacy of a low FODMAP diet in irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and network meta-analysis. Gut 2022, 71, 1117–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, A.C.; Moayyedi, P.; Lacy, B.E.; Lembo, A.J.; Saito, Y.A.; Schiller, L.R.; Soffer, E.E.; Spiegel, B.M.; Quigley, E.M. American College of Gastroenterology monograph on the management of irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology| ACG 2014, 109, S2–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moayyedi, P.; Marsiglio, M.; Andrews, C.N.; Graff, L.A.; Korownyk, C.; Kvern, B.; Lazarescu, A.; Liu, L.; MacQueen, G.; Paterson, W.G. Patient engagement and multidisciplinary involvement has an impact on clinical Guideline development and decisions: a comparison of two irritable bowel syndrome guidelines using the same data. Journal of the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology 2019, 2, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullin, G.E.; Shepherd, S.J.; Chander Roland, B.; Ireton-Jones, C.; Matarese, L.E. Irritable bowel syndrome: contemporary nutrition management strategies. Journal of parenteral and enteral nutrition 2014, 38, 781–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halmos, E.P.; Power, V.A.; Shepherd, S.J.; Gibson, P.R.; Muir, J.G. A diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2014, 146, 67–75.e65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Lanen, A.-S.; de Bree, A.; Greyling, A. Efficacy of a low-FODMAP diet in adult irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European journal of nutrition 2021, 60, 3505–3522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomassen, R.; Luque, V.; Assa, A.; Borrelli, O.; Broekaert, I.; Dolinsek, J.; Martin-de-Carpi, J.; Mas, E.; Miele, E.; Norsa, L. An ESPGHAN Position Paper on the Use of Low-FODMAP Diet in Pediatric Gastroenterology. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 2022, 75, 356–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaie, A.; Buresi, M.; Lembo, A.; Lin, H.; McCallum, R.; Rao, S.; Schmulson, M.; Valdovinos, M.; Zakko, S.; Pimentel, M. Hydrogen and methane-based breath testing in gastrointestinal disorders: the North American Consensus. The American journal of gastroenterology 2017, 112, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storhaug, C.L.; Fosse, S.K.; Fadnes, L.T. Country, regional, and global estimates for lactose malabsorption in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017, 2, 738–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misselwitz, B.; Butter, M.; Verbeke, K.; Fox, M.R. Update on lactose malabsorption and intolerance: pathogenesis, diagnosis and clinical management. Gut 2019, 68, 2080–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiecień, J.; Hajzler, W.; Kosek, K.; Balcerowicz, S.; Grzanka, D.; Gościniak, W.; Górowska-Kowolik, K. No Correlation between Positive Fructose Hydrogen Breath Test and Clinical Symptoms in Children with Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: A Retrospective Single-Centre Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, P.R.; Newnham, E.; Barrett, J.S.; Shepherd, S.J.; Muir, J.G. Review article: fructose malabsorption and the bigger picture. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007, 25, 349–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozinsky, A.C.; Boé, C.; Palmero, R.; Fagundes-Neto, U. Fructose malabsorption in children with functional digestive disorders. Arq Gastroenterol 2013, 50, 226–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawłowska, K.; Umławska, W.; Iwańczak, B. Prevalence of Lactose Malabsorption and Lactose Intolerance in Pediatric Patients with Selected Gastrointestinal Diseases. Adv Clin Exp Med 2015, 24, 863–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pensabene, L.; Salvatore, S.; Turco, R.; Tarsitano, F.; Concolino, D.; Baldassarre, M.E.; Borrelli, O.; Thapar, N.; Vandenplas, Y.; Staiano, A. Low FODMAPs diet for functional abdominal pain disorders in children: critical review of current knowledge. Jornal de pediatria 2019, 95, 642–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bland, J.M.; Altman, D.G. Comparisons against baseline within randomised groups are often used and can be highly misleading. Trials 2011, 12, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volta, U.; Pinto-Sanchez, M.I.; Boschetti, E.; Caio, G.; De Giorgio, R.; Verdu, E.F. Dietary Triggers in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Is There a Role for Gluten? J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2016, 22, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koumbi, L.; Giouleme, O.; Vassilopoulou, E. Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity and Irritable Bowel Disease: Looking for the Culprits. Current Developments in Nutrition 2020, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesiekierski, J.R.; Newnham, E.D.; Irving, P.M.; Barrett, J.S.; Haines, M.; Doecke, J.D.; Shepherd, S.J.; Muir, J.G.; Gibson, P.R. Gluten causes gastrointestinal symptoms in subjects without celiac disease: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology| ACG 2011, 106, 508–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroccio, A.; Mansueto, P.; Iacono, G.; Soresi, M.; D'alcamo, A.; Cavataio, F.; Brusca, I.; Florena, A.M.; Ambrosiano, G.; Seidita, A. Non-celiac wheat sensitivity diagnosed by double-blind placebo-controlled challenge: exploring a new clinical entity. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology| ACG 2012, 107, 1898–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bruijn, C.M.; Rexwinkel, R.; Gordon, M.; Sinopoulou, V.; Benninga, M.A.; Tabbers, M.M. Dietary interventions for functional abdominal pain disorders in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Review of Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2022, 16, 359–371. [Google Scholar]

- Barbaro, M.R.; Cremon, C.; Wrona, D.; Fuschi, D.; Marasco, G.; Stanghellini, V.; Barbara, G. Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity in the Context of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devulapalli, C.S. Gluten-free diet in children: a fad or necessity? Archives of Disease in Childhood 2021, 106, 628–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devulapalli, C.S. Non-coeliac gluten sensitivity in children. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2020, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catassi, C.; Elli, L.; Bonaz, B.; Bouma, G.; Carroccio, A.; Castillejo, G.; Cellier, C.; Cristofori, F.; de Magistris, L.; Dolinsek, J. , et al. Diagnosis of Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity (NCGS): The Salerno Experts' Criteria. Nutrients 2015, 7, 4966–4977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, W.C.; Sacks, F.; Trichopoulou, A.; Drescher, G.; Ferro-Luzzi, A.; Helsing, E.; Trichopoulos, D. Mediterranean diet pyramid: a cultural model for healthy eating. The American journal of clinical nutrition 1995, 61, 1402S–1406S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinu, M.; Pagliai, G.; Casini, A.; Sofi, F. Mediterranean diet and multiple health outcomes: an umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies and randomised trials. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2018, 72, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwingshackl, L.; Morze, J.; Hoffmann, G. Mediterranean diet and health status: Active ingredients and pharmacological mechanisms. British journal of pharmacology 2020, 177, 1241–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zito, F.P.; Polese, B.; Vozzella, L.; Gala, A.; Genovese, D.; Verlezza, V.; Medugno, F.; Santini, A.; Barrea, L.; Cargiolli, M. Good adherence to mediterranean diet can prevent gastrointestinal symptoms: A survey from Southern Italy. World journal of gastrointestinal pharmacology and therapeutics 2016, 7, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmaliklis, I.-N.; Liveri, A.; Ntelis, B.; Paraskeva, K.; Goulis, I.; Koutelidakis, A.E. Increased functional foods’ consumption and Mediterranean diet adherence may have a protective effect in the appearance of gastrointestinal diseases: a case–control study. Medicines 2019, 6, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stróżyk, A.; Horvath, A.; Szajewska, H. FODMAP dietary restrictions in the management of children with functional abdominal pain disorders: A systematic review. Neurogastroenterology & Motility 2022, 34, e14345. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S.C.; Whelan, K.; Gearry, R.B.; Day, A.S. Low FODMAP diet in children and adolescents with functional bowel disorder: A clinical case note review. JGH Open 2020, 4, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turco, R.; Salvatore, S.; Miele, E.; Romano, C.; Marseglia, G.L.; Staiano, A. Does a low FODMAPs diet reduce symptoms of functional abdominal pain disorders? A systematic review in adult and paediatric population, on behalf of Italian Society of Pediatrics. Italian Journal of Pediatrics 2018, 44, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelrod, C.H.; Saps, M. The Role of Fiber in the Treatment of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders in Children. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pärtty, A.; Rautava, S.; Kalliomäki, M. Probiotics on Pediatric Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korterink, J.J.; Ockeloen, L.; Benninga, M.A.; Tabbers, M.M.; Hilbink, M.; Deckers-Kocken, J.M. Probiotics for childhood functional gastrointestinal disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatrica 2014, 103, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojsak, I.; Kolaček, S.; Mihatsch, W.; Mosca, A.; Shamir, R.; Szajewska, H.; Vandenplas, Y.; van den Akker, C.H.; Berni Canani, R.; Dinleyici, E.C. Synbiotics in the Management of Pediatric Gastrointestinal Disorders: Position Paper of the ESPGHAN Special Interest Group on Gut Microbiota and Modifications. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 2023, 76, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpato, E.; Auricchio, R.; Penagini, F.; Campanozzi, A.; Zuccotti, G.V.; Troncone, R. Efficacy of the gluten free diet in the management of functional gastrointestinal disorders: a systematic review on behalf of the Italian Society of Paediatrics. Italian Journal of Pediatrics 2019, 45, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelrod, C.H.; Saps, M. Global Dietary Patterns and Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. Children (Basel) 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabbers, M.; DiLorenzo, C.; Berger, M.; Faure, C.; Langendam, M.; Nurko, S.; Staiano, A.; Vandenplas, Y.; Benninga, M. Evaluation and treatment of functional constipation in infants and children: evidence-based recommendations from ESPGHAN and NASPGHAN. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition 2014, 58, 258–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro Cruz, L.; Minard, C.; Guffey, D.; Chumpitazi, B.P.; Shulman, R.J. Does a Minority of Children With Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders Receive Formal Diet Advice? Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 2020, 44, 1525–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Gil, J.F.; García-Hermoso, A.; Sotos-Prieto, M.; Cavero-Redondo, I.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V.; Kales, S.N. Mediterranean diet-based interventions to improve anthropometric and obesity indicators in children and adolescents: a systematic review with meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Advances in Nutrition 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouhanick, B.; Sosner, P.; Brochard, K.; Mounier-Véhier, C.; Plu-Bureau, G.; Hascoet, S.; Ranchin, B.; Pietrement, C.; Martinerie, L.; Boivin, J.M. , et al. Hypertension in Children and Adolescents: A Position Statement From a Panel of Multidisciplinary Experts Coordinated by the French Society of Hypertension. Frontiers in Pediatrics 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mearin, M.L.; Agardh, D.; Antunes, H.; Al-Toma, A.; Auricchio, R.; Castillejo, G.; Catassi, C.; Ciacci, C.; Discepolo, V.; Dolinsek, J. , et al. ESPGHAN Position Paper on Management and Follow-up of Children and Adolescents With Celiac Disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2022, 75, 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llanos-Chea, A.; Fasano, A. Gluten and Functional Abdominal Pain Disorders in Children. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesiekierski, J.R.; Newnham, E.D.; Irving, P.M.; Barrett, J.S.; Haines, M.; Doecke, J.D.; Shepherd, S.J.; Muir, J.G.; Gibson, P.R. Gluten Causes Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Subjects Without Celiac Disease: A Double-Blind Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology | ACG 2011, 106, 508–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesiekierski, J.R.; Peters, S.L.; Newnham, E.D.; Rosella, O.; Muir, J.G.; Gibson, P.R. No Effects of Gluten in Patients With Self-Reported Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity After Dietary Reduction of Fermentable, Poorly Absorbed, Short-Chain Carbohydrates. Gastroenterology 2013, 145, 320–328.e323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agakidis, C.; Kotzakioulafi, E.; Petridis, D.; Apostolidou, K.; Karagiozoglou-Lampoudi, T. Mediterranean Diet Adherence is Associated with Lower Prevalence of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders in Children and Adolescents. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howatson, A.; Wall, C.; Turner-Benny, P. The contribution of dietitians to the primary health care workforce. Journal of Primary Health Care 2015, 7, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro-Cruz, L.; Heitkemper, M.; Chumpitazi, B.P.; Shulman, R.J. Literature review: dietary intervention adherence and adherence barriers in functional gastrointestinal disorder studies. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 2020, 54, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).