Submitted:

08 May 2023

Posted:

08 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Model establishment and simulation process

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Mechanical properties of PI composites

3.2. Tribological properties of PI composites

4. Conclusion

- Adding graphene based nanomaterials can improve the mechanical properties of PI composites, in which K5-GO exhibits the best effect, increasing the Young’s modulus to 6.87 GPa and the shear modulus to 1.8 GPa, which are 94% and 16% higher than pure PI. Besides, the enhancement mechanism was revealed by analyzing the interaction energy between the modifiers and PI molecular. The higher the interaction energy, the stronger the adsorption effect, and resulting in the the better the mechanical performance.

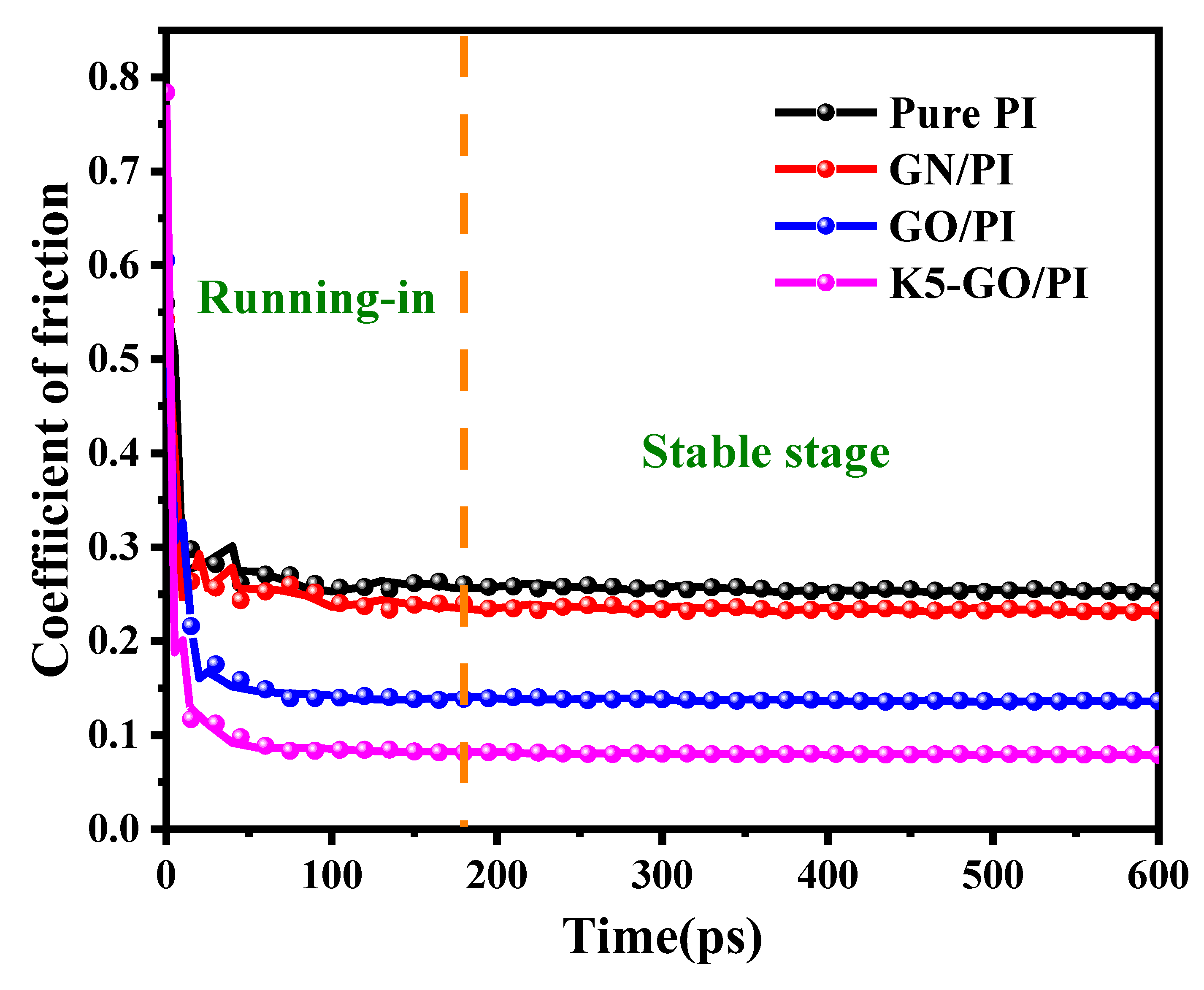

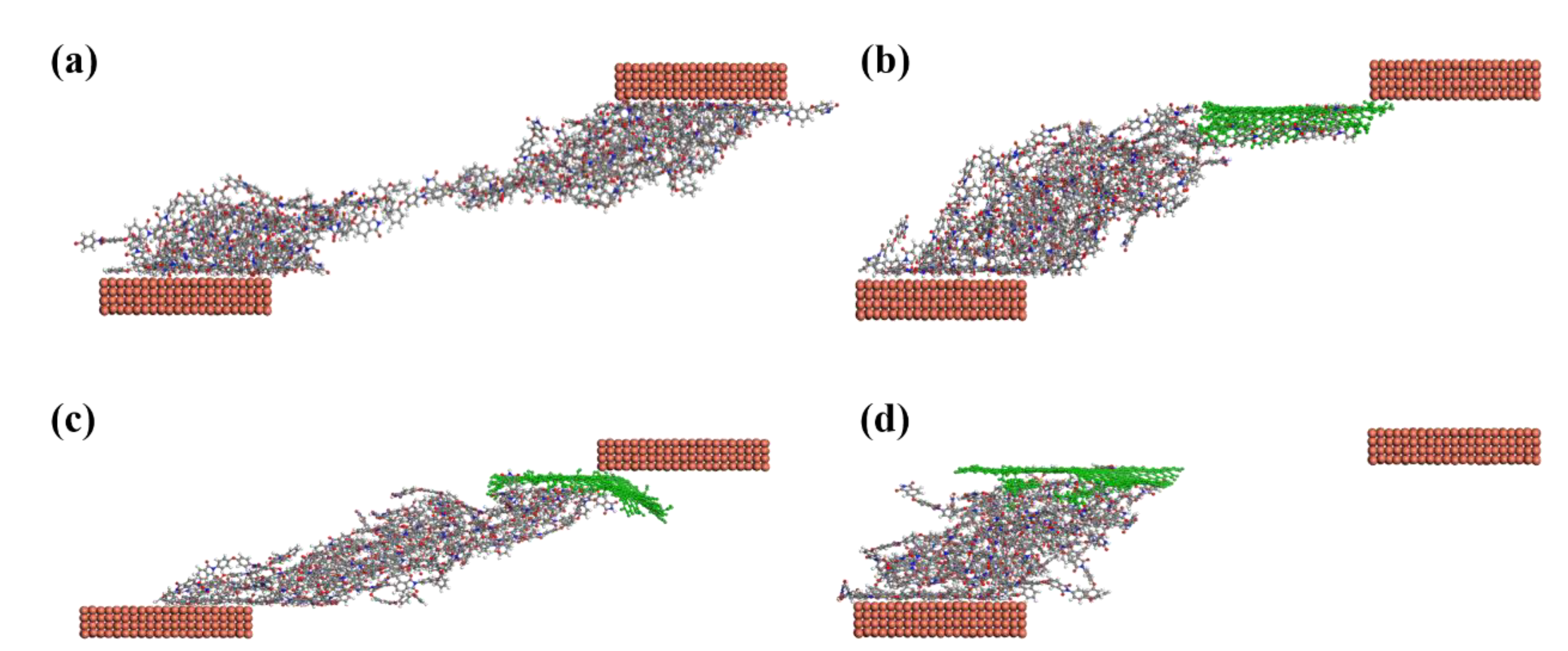

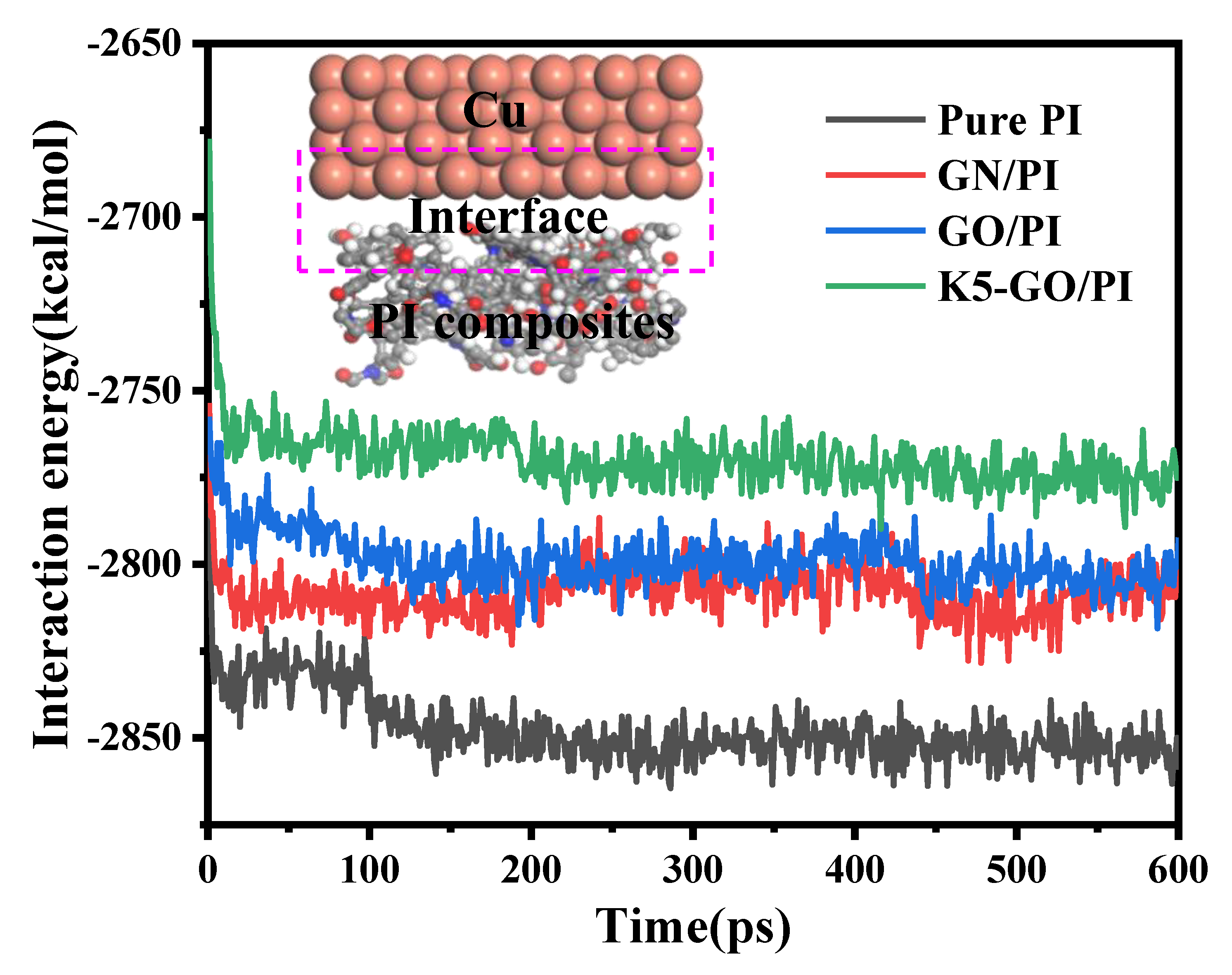

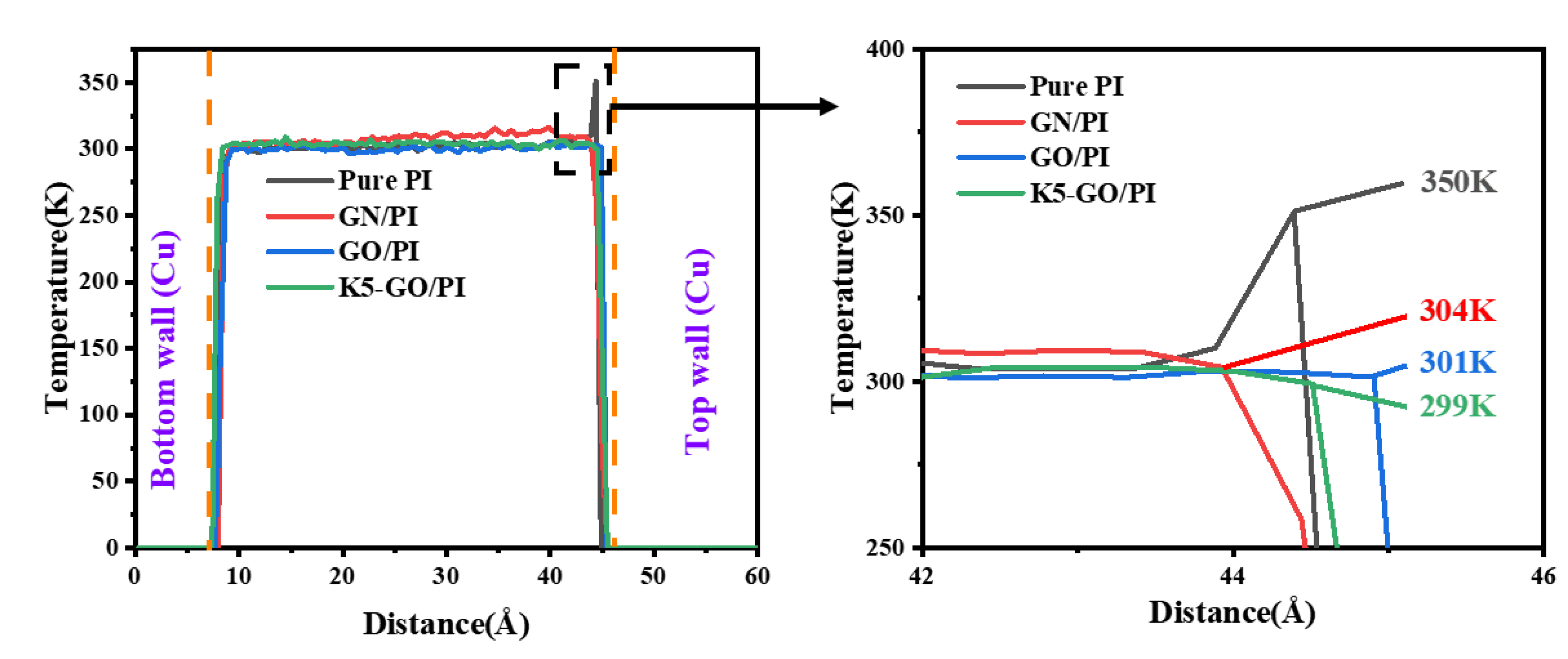

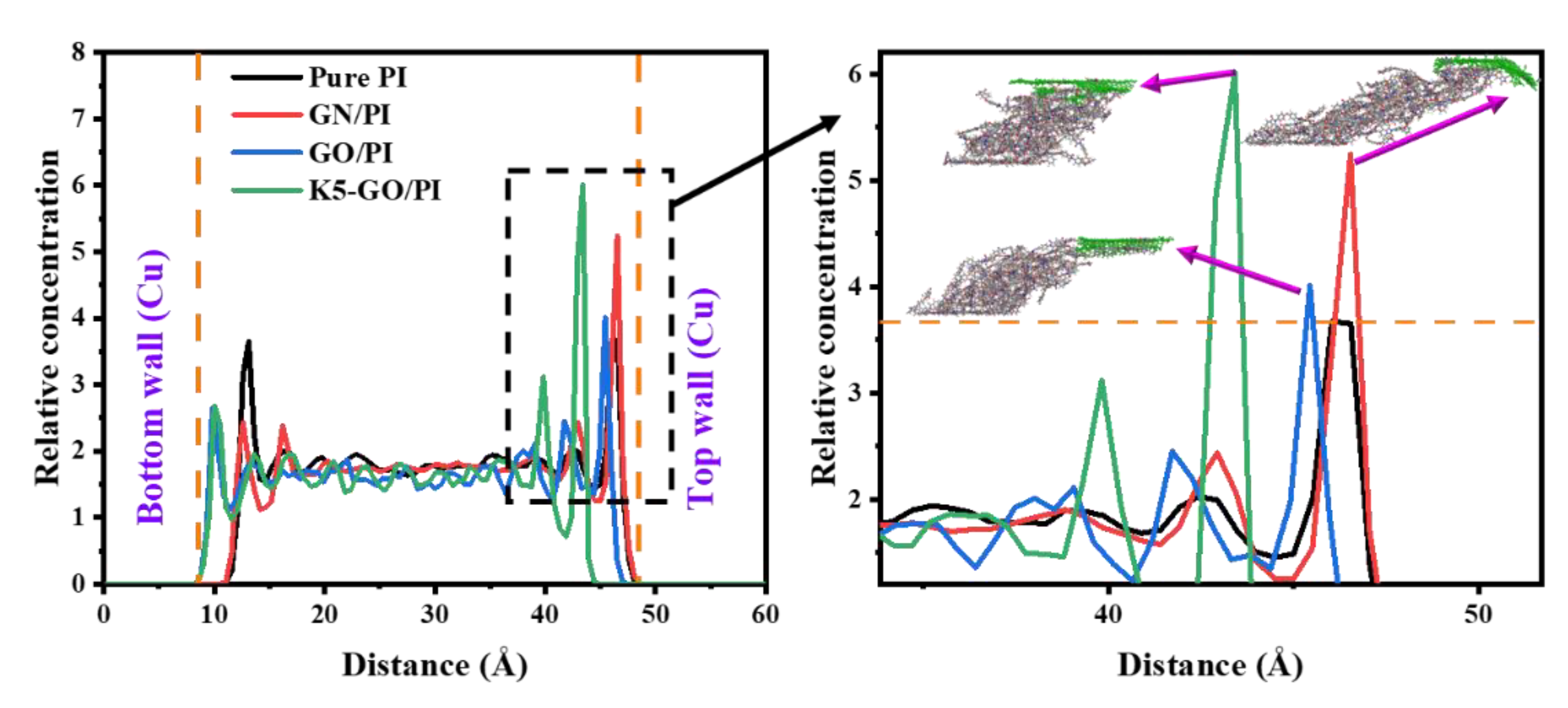

- Compared with pure PI, the surface modified PI composites have smaller friction coefficients, among which K5-GO can reduce the friction coefficient to one-third of the original value. The K5-GO/PI also shows the smallest shear deformation. By analyzing the interfacial interaction energy between PI and the Cu layer, it was found that the interfacial interaction between PI and the friction pair would decrease after the addition of modifiers, further confirming the enhanced effect of modifiers on the PI matrix. These results are helpful for a deeper understanding of the structure and properties of polymer-based composites, and provide important references for the design and manufacture of high-performance polymer composites.

Acknowledgments

References

- Li, B.; Lv, W.; Zhao, N.; Li, J.; Peng, D.; Yu, Y.; Mu, Q.; Zhang, F.; Wang, F.; Wang, Z. Research development of polyimide based solid lubricant. New Chemical Materials 2017, 45, 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Kitoh, M.; Honda, Y. Preparation and tribological properties of sputtered polyimide film. Thin Solid Films 1995, 271, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feger, C.; Franke, H. Polyimides fundamentals and applications; CRC Press, 2018; pp. 759–814. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, K.S. Handbook of thermoset plastics; Elsevier, 2014; pp. 297–424. [Google Scholar]

- Ree, M. High performance polyimides for applications in microelectronics and flat panel displays. Macromolecular Research 2006, 14, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.Y.; He, J.J.; Yang, H.X.; Yang, S.Y. Progress in Aromatic Polyimide Films for Electronic Applications: Preparation, Structure and Properties. Polymers 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuanhao, Y.; Gai, Z.; Jingfu, S.; Qingjun, D. Mechanical and Tribological Properties of Polyimide Composites for Reducing Weight of Ultrasonic Motors. Key Eng. Mater. (Switzerland) 2019, 799, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Bahadur, S. The development of transfer layers and their role in polymer tribology. Wear 2000, 245, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadur, S.; Fu, Q.; Gong, D. THE EFFECT OF REINFORCEMENT AND THE SYNERGISM BETWEEN CUS AND CARBON-FIBER ON THE WEAR OF NYLON. Wear 1994, 178, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijwe, J.; Indumathi, J.; Rajesh, J.J.; Fahim, M. Friction and wear behavior of polyetherimide composites in various wear modes. Wear 2001, 249, 715–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, K.; Lu, Z.; Hager, A.M. Recent advances in polymer composites’ tribology. Wear 1995, 190, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, G.J.; Zhang, Z. Sliding wear of polyetherimide matrix composites I. Influence of short carbon fibre reinforcement. Wear 2005, 258, 776–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.F.; Meng, Z.J.; Xin, X.C.; Liu, H.; Yan, F.Y. Tribological Behavior and Thermal Stability of Thermoplastic Polyimide/Poly (Ether Ether Ketone) Blends at Elevated Temperature. Journal of Macromolecular Science Part B-Physics 2020, 60, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.X.; Wong, J.F.; Petru, M.; Hassan, A.; Nirmal, U.; Othman, N.; Ilyas, R.A. Effect of Nanofillers on Tribological Properties of Polymer Nanocomposites: A Review on Recent Development. Polymers 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breki, A.D.; Vasilyeva, E.S.; Tolochko, O.V.; Didenko, A.L.; Nosonovsky, M. Frictional Properties of a Nanocomposite Material With a Linear Polyimide Matrix and Tungsten Diselinide Nanoparticle Reinforcement. Journal of Tribology-Transactions of the Asme 2019, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Yan, F.; Xue, Q. Tribological behavior and SEM investigation of the polyimide/SiO_2 nanocomposites. Journal of Chinese Electronic Microscopy Society 2003, 22, 420–425. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.R.; Pei, X.Q.; Wang, Q.H. Friction and wear studies of polyimide composites filled with short carbon fibers and graphite and micro SiO2. Materials & Design 2009, 30, 4414–4420. [Google Scholar]

- Panin, S.V.; Luo, J.K.; Buslovich, D.G.; Alexenko, V.O.; Kornienko, L.A.; Bochkareva, S.A.; Byakov, A.V. Experimental-FEM Study on Effect of Tribological Load Conditions on Wear Resistance of Three-Component High-Strength Solid-Lubricant PI-Based Composites. Polymers 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Kou, Z.M.; Cui, G.J. The tribological properties of carbon fiber reinforced polyimide matrix composites under distilled water condition. Industrial Lubrication and Tribology 2016, 68, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Q.; Jia, X.H.; Xiao, Q.F.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.Z.; Yang, J.; Song, H.J.; Zhang, Z.Z. CuO nanowires uniformly grown on carbon cloth to improve mechanical and tribological properties of polyimide composites. Materials Chemistry and Physics 2022, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Yan, F.Y.; Xue, Q.J. Investigation of tribological properties of polyimide/carbon nanotube nanocomposites. Materials Science and Engineering a-Structural Materials Properties Microstructure and Processing 2004, 364, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.B.; Wang, J.Z.; Liu, N.; Yan, F.Y. Synergism of several carbon series additions on the microstructures and tribological behaviors of polyimide-based composites under sea water lubrication. Materials & Design 2014, 63, 325–332. [Google Scholar]

- Sekiguchi, I.; Takumi, K.; Naitoh, K.; Saitoh, T.; Watanabe, Y. On the effects of fillers upon the tribological properties of thermosetting polyimide. Res. Rep. Kogakuin Univ. (Japan) 1996, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Yan-jiang, S.; Li-jian, H.; Peng, Z.H.U.; Xiao-dong, W.; Pei, H. Friction and Wear of Coupling Agent Treated Glass Fiber Modified Polyimide Composites. Journal of Materials Engineering 2009, 58–62. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.L.; Wang, S.J.; Wang, Q.; Xing, M. Enhancement of fracture properties of polymer composites reinforced by carbon nanotubes: A molecular dynamics study. Carbon 2018, 129, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, C.Y.; Shen, C.; Zeng, M.; Nie, P.; Song, H.J.; Li, S.J. Influence of graphene oxide as filler on tribological behaviors of polyimide/graphene oxide nanocomposites under seawater lubrication. Monatshefte Fur Chemie 2017, 148, 1301–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.L.; Huang, W.J. 3rd International Conference on Chemical Engineering and Advanced Materials (CEAM 2013); Guangzhou,PEOPLES R CHINA, 2013; Volume 785-786, pp. 138–144. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Y.; Lei, H.; Song, J.; Zhao, G.; Ding, Q. Molecular Dynamics Simulation on the Tribological Properties of Polytetrafluoroethylene Reinforced with Modified Graphene. Tribology 2022, 42, 598–608. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.Z.; Ma, T.B.; Wang, H. Energy dissipation in atomic-scale friction. Friction 2013, 1, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Optimization process | Algorithm | Convergence criterion | Temperature | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geometry optimization | Smart | 1×10-4 kcal/mol 0.005 kcal/mol/Å |

/ | |

| Anneal | Nose thermostat | / | 300-600 K | |

| NVT | Nose thermostat | / | 300 K | 300 ps |

| NPT | Berendsen barostat | / | 300 K | 600 ps |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).