Introduction

Over the evolution of modern Homo sapiens, pathogens co-evolve with us and pose a persistent threat to our survival and well-being. On occasions, dangerous pathogen emerge that threaten a large fraction of the extant population. Modern medicine and medical technologies have helped to ameliorate the threat from pathogens through detection, treatment, and vaccination, all of which aided by medical research. To be fair, modern medicine has done a good job at protecting the world’s population from dangerous pathogens, and limiting the spread of new and emerging pathogens. However, on rare occasions, a new, highly infectious pathogen could break through our defences in disease surveillance and containment that ultimately overwhelms our medical systems. One such pathogen is SARS-CoV-2 that causes COVID-19 disease.

For a pathogen that has spread worldwide and broken through our surveillance and containment system, and for which curative treatment do not exists, early detection and isolation of cases remain crucial for successful containment of the pathogen, and limiting its spread and penetration into the population. Hence, clinical diagnostics for detecting and confirming cases of SARS-CoV-2 plays crucial roles in aiding containment of the virus, as well as providing early treatment for those infected to help retard clinical progression towards dangerous disease and serious complications. Overall, the world’s population is fortunate that, in the current pandemic, key technologies for early detection of SARS-CoV-2, and informing of its viral load, and whether someone is exposed and recovering from the virus is available globally, and at a reasonable price-point to aid widespread use of clinical testing for containing the virus.

As a virus enters human cells and replicates, there exists multiple points at which modern medical technologies could detect and assess the abundance of the virus. The first point of contact is the virus itself, where modern reverse transcriptase quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) could detect the presence/absence of the virus with high sensitivity and reasonable speed. As will be detailed later, assay time and overall cost of each test makes a big difference in the extent in which testing is deployed at the city, state, and national level to contain SARS-CoV-2. But, PCR tests remain at a relatively high price-point, involves the use of expensive and specialised equipment, and require trained personnel for the test. Herein comes the next approach of detecting some quintessential fragment of the virus in what is known as an antigen rapid test (ART). In its most typical configuration, the ART test resembles somewhat a pregnancy test, where the same analytical concept is used to detect some protein on the viral surface as compared to biomarkers for pregnancy. Deployed as a lateral flow assay format, modified antibodies on the assay strip will bind to target antigens from the virus, and deliver a readout in 10 to 30 minutes, all at room temperature, and without the need for specialised equipment. Hence, ART affords high speed and could be deployed at scale such as in pre-event testing, but it is less sensitive compared to PCR test.

Beyond detecting the virus itself, there is also value in evaluating whether an individual has been exposed to the virus, has mild or no symptoms, and who is recovering. This then brings forth the use of antibody or serology tests, where the assay kit assesses the IgM and IgG levels of the individual in determining whether he is in the active infection phase or whether he is in remission and recovering. For example, a person with high IgM levels and accompanying low IgG levels would be in the active infection phase, and thus, requiring treatment and isolation. On the other hand, a person with low IgM level but high IgG level suggests that he has been previously exposed to the virus, and is recovering with possible long-lasting immunity. Hence, such serological antibody tests also augment our testing regimen in picking out individuals in the active infection phase, and who require more medical attention. Finally, newly developed breathlyzer tests also provides early indications of a person in the active infection phase, and could serve as a more precise and sensitive screening tool compared to temperature screening. However, the test remains in the evaluation stage, and must be augmented with the gold standard PCR test.

This review article focuses on summarizing the technological tools and innovations that have aided the fight against SARS-CoV-2 in Singapore on the clinical diagnostics front. Besides detailing the types of diagnostics used, emphasis would also be laid on mechanisms as well as unique modifications to standard assays to help cater to the circumstances in Singapore. More broadly, the article would also assess the elements that have helped put together a unified and coherent technological response to combat COVID-19 pandemic in Singapore through the key arm of clinical diagnostics.

Confluence of Factors that Enable Technology to Play A Larger Role in Combating this Pandemic

SARS-CoV-2 is the third major coronavirus to hit humans in the 21st century following on the heels of SARS in 2003 and MERS in 2009. In the earlier two epidemics, SARS and MERS did not reach global pandemic proportions largely because of their higher case fatality rate as well as their lower transmissivity. SARS-CoV-2, however, is different due to its higher binding affinity to the ACE2 receptor of human cells. Hence, this calls for a screening tool that could help identify individuals in the early phase of infection, and thus, help reduce the transmission of the virus into a country or population.

One crucial lesson the world learns from the SARS epidemic was the value of temperature screening in identifying suspected cases of the disease. Deployed at airports and other points of entry into a country, temperature screening proved to be useful for rapid, non-invasive profile of suspected cases of the disease, thereby, providing a means for early diagnosis and intervention to prevent onset of severe disease. Similarly in the current SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, temperature screening sensors and cameras are the first line of defence against the virus entering the virus. However, higher transmissivity of the virus and delayed symptom manifestation meant that temperature screening is not as effective in identifying individuals at the initial phase of infection in this pandemic compared to the SARS epidemic.

Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) quickly became the tool of choice for identifying positive cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection in this pandemic due to a large part to declining cost of PCR, increasing maturity of the quantitative PCR technique, and increasing availability of PCR thermocyclers. Specifically, many diagnostic companies and research groups in Singapore has developed diagnostic methods based on PCR for a variety of viral and microbial pathogens. Thus, techniques such as primer and probe design, selection of appropriate high fidelity polymerases and assembly of a complete test skills are core skills that have been gradually built up in the Singapore R&D ecosystem in the intervening years between the SARS epidemic in 2003 and the current SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Hence, Singapore is fortunate to have the requisite R&D capability and manpower to quickly develop its own RT-qPCR test kit for SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis early in the pandemic, which is important given supply disruptions in enzymes and primers and other kit components during the outbreak.

Besides RT-qPCR, another favourable development before the current pandemic is the increasingly maturity of lateral flow assays and their declining cost. Specifically, lateral flow assays were first popularized by pregnancy test kit. But, the technique shows promise for application in disease diagnosis, and indeed a plethora of tests have been developed, around the world, for the detection and diagnosis of many disease pathogens including viruses, bacteria and fungi. In addition, the concept governing lateral flow assay has also been applied to detecting antibodies diagnostic of the type of immune response triggered in serological antibody tests. In this area, Singapore also has seen an increasing interest, amongst local biotechnology and disease diagnostic companies in developing diagnostic kits based on the lateral flow assay format. Simple, easy to learn and use, and available at the point of care or in remote regions of the world, availability and steady interest in developing diagnostic tests based on the lateral flow assay format meant that the world does possess the technological means (not the initial capacity) to detect SARS-CoV-2 infection. More specifically, given the similarity of the surface proteins of SARS and SARS-CoV-2, antibodies and technologies developed in the preceding decade to detect SARS infection could be repurposed, in the initial stages of the fight, to detect the then nascent SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The wheels of technology continue to turn, and this help bring forth enabling tools that we now possess to detect SARS-CoV-2 more cheaply, accurately, and with fewer resources. One approach is the use of isothermal amplification to replace the thermal cycling involved in conventional RT-PCR. This helps reduce the need for specialized equipment, and enables the diagnostic tests to be developed for point of care application or use in remote locations in the world. Another approach is in the use of CRISPR-based detection method for specific genes in the viral genome. Unlike conventional antibody-based or PCR amplification-based detection methods, CRISPR based techniques may eventually remove the need for PCR amplification, as well as the time and effort needed to develop monoclonal antibodies for a particular antigen target as in conventional antigen rapid test employed in this pandemic. Finally, new modes of diagnostics are constantly being developed, and one of particular interest in the present pandemic is the use of mass spectrometry powered breath test to detect specific biomarker sets of volatile organic compounds in the breath of patients with SARS-CoV-2. This represents a quantum leap in analytical speed and performance, which, for the first time, afford a non-invasive, rapid (1 min), and quantitative measure of a person’s set of volatile organic compounds in his breath for the purpose of SARS-CoV-2 infection detection. Capable of being applied for the diagnosis of other pathogens, breath analyzer may become the tool of choice for rapid screening at airports and other points of entry in the future for detecting other aetiological agents that will, inevitably, emerge.

Taken together, the world does possess, at a reasonable price-point, the technological tools for detecting SARS-CoV-2 at the early stage of the outbreak. What is lacking is an appreciation of the virus transmissivity, and crucially, delayed onset of clinically detectable symptoms that break through the world’s defence system of temperature screening and RT-PCR diagnosis. Even though SARS-CoV-2 is a different but related virus of SARS and possess slightly different surface proteins, the world did possess sufficient tools to detect SARS-CoV-2 infection whether at the nucleic acid, protein or serological level at the early part of the outbreak. This comes about due to the continuous investment, especially in Western countries, in diagnostic technology based on the proven platform of RT-PCR, and lateral flow assay, as well as reusing and repurposing technologies previously developed to detect SARS infection in 2003. However, the speed at which the virus spread as well as the scale that the pandemic evolved into meant that the world could not rely on diagnostics developed for SARS, and this forms the basis on which the world put in resources to develop new diagnostic tests for SARS-CoV-2 based on established technologies, as well as develop new innovative solutions that may disrupt the diagnostic field in years to come. The latter constitutes tests based on CRISPR and mass spectrometry-enabled breath analysis.

Overview of Diagnostic Tests Developed to Combat SARS-CoV-2

Similar to other virus and microbial pathogens, the goal of diagnostic tests is two-fold: (i) the detection of cases, and (ii) identification of aetiological agent to aid patient treatment. Often the two-goals are intertwined, and distinction between them are blurred. In general, there are two approaches for detecting a pathogen mediated infection in humans. First, the direct approach would be to detect the virus itself or some parts of it if it has been damaged by the body’s immune system. Second, an indirect methodology would be to detect and identify the type of immune response provoked by the microbial or viral infection. Usually, this would be either an innate immune response or adaptive immune response. Both types of immune responses could be detected by modern diagnostic tests, and these have been developed, refined, and deployed in the fight against SARS-CoV-2. Typically, these tests use immunochromatographic methods to detect either IgM or IgG or both.

In the area of direct detection of virus or viral fragment, the gold standard approach has been nucleic acid-based molecular tests. These typically rely on high specificity primer to fish out particular DNA or RNA genetic fragment, and amplify them with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to afford ready detection of virus, and importantly, to gain an estimate of viral load in patient. The second objective of which is particularly important to patient care, and downstream contact tracing efforts if the viral load of the patient is high that meant potential for super-spreading of virus. In the current COVID-19 pandemic, reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) detects specific viral gene in the RNA genome of the virus, and is the gold standard approach, and is highly sensitive. However, RT-PCR requires specialized equipment (e.g., thermocycler, and specialised reagents), and the process takes between 1 to 4 hours depending on the number of genes profiled.

Beyond nucleic acid-based molecular tests are antibody-based tests which profile for specific proteins on the surface of the virus. These proteins could detect a live virus, or fragments of a virus that have been partially damaged by the immune system. Known as antigen rapid tests, these tests profile for specific viral proteins of SARS-CoV-2 to aid the direct detection and identification of cases. Positive result would mean that the person has been exposed to the virus or is having an active infection. Further RT-PCR test would provide an estimate of the viral load of the patient. Although able to detect cases of viral infection, antigen rapid tests are typically employed to complement RT-PCR tests.

Besides PCR-based tests, antigen rapid tests, and antibody-based tests, there are also other modalities in which diagnostics have been used to detect SARS-CoV-2. One variant is nucleic acid-based test with isothermal amplification, that in removing the need for temperature cycling, help afford the approach to be usable at the point-of-care or even in remote settings. Another method is the use of CRISPR-based nucleic acid detection and cleavage to identify specific gene of the virus, and aid in the detection of positive cases. Finally, there is also emerging interest in the use of specific ensemble of volatile organic compounds in the breath of SARS-CoV-2 positive patients in detecting positive cases of viral infection.

Polymerase Chain Reaction COVID-19 Tests

Given its sensitivity and specificity, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests were the first tool of choice for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Since SARS-CoV-2 has an RNA-based genome, reverse transcription is needed to transcribe RNA to cDNA prior to PCR amplification. Up until now, RT-PCR remains the gold standard approach for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

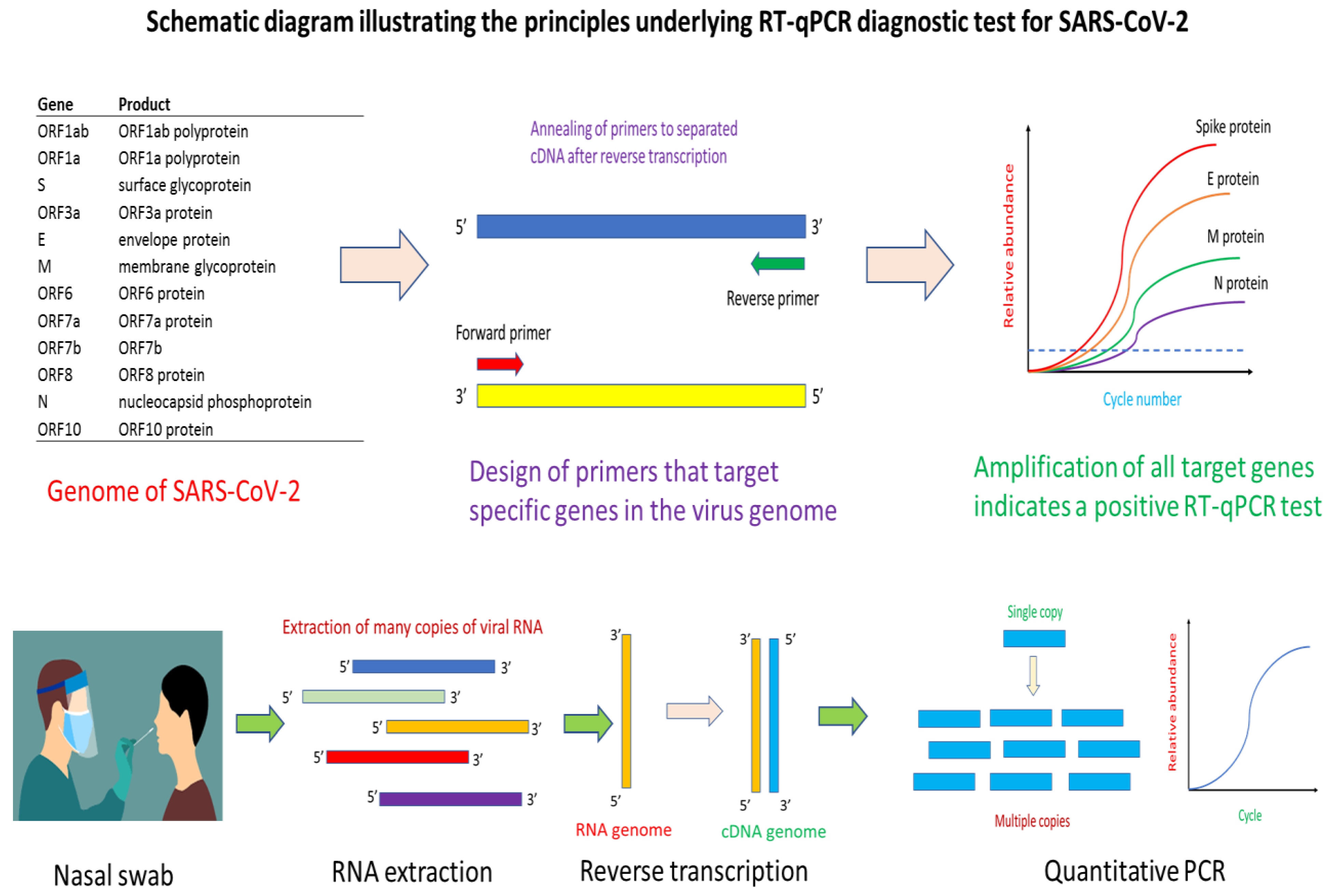

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram illustrating the principles underlying the RT-qPCR approach for detecting SARS-CoV-2. The key principle of the approach is the use of genomic information to design primers specific to the gene of interest, whereupon a quantitative PCR assay would help confirm whether the virus is present in a patient’s sample. Essentially, the method starts with a nasal swab to obtain the viral sample. This would be subjected to a RNA extraction step to obtain the needed viral RNA for the downstream reverse transcription step. After reverse transcription, the complementary DNA obtained will serve as template for the binding of quantitative PCR (qPCR) primers for thermal cyclic amplification. Successful amplification of gene of interest, and observation of fluorescence signal informs the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in patient’s sample.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram illustrating the principles underlying the RT-qPCR approach for detecting SARS-CoV-2. The key principle of the approach is the use of genomic information to design primers specific to the gene of interest, whereupon a quantitative PCR assay would help confirm whether the virus is present in a patient’s sample. Essentially, the method starts with a nasal swab to obtain the viral sample. This would be subjected to a RNA extraction step to obtain the needed viral RNA for the downstream reverse transcription step. After reverse transcription, the complementary DNA obtained will serve as template for the binding of quantitative PCR (qPCR) primers for thermal cyclic amplification. Successful amplification of gene of interest, and observation of fluorescence signal informs the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in patient’s sample.

The first step in the design of a RT-PCR test kit is to obtain a reliable genome sequence of the virus. With automated or manual annotation of the open reading frames or genes in the genome, it would then form the basis for the design of primers and probe for specific targeting and amplification of genes of interest in the virus genome that help identifies positive cases of infection. Key to success in the RT-PCR approach is the use of highly specific primers and probes that do not cross-reactive with genes from other viruses and microbes. Essentially, the primers help identify the region of a gene for PCR amplification while the probe quantifies, in a specific manner, the amount of PCR amplicons that have been generated. RT-PCR can be multiplexed for increasing its selectivity. Depending on the number of genes targeted in a multiplex RT-PCR assay, correct amplification of all target genes would mean the identification of a positive case of infection. In the current pandemic, many RT-PCR tests for SARS-CoV-2 have been developed. Similar in concept, the various tests differ in the types of primers and probes used, genes targeted, as well as specificity and sensitivity of the assay.

Typically, a RT-PCR SARS-CoV-2 test starts with obtaining the sample which could be a nasal swab. Other types of samples such as nasopharyngeal, oropharyngeal and throat could be used for RT-PCR analysis for SARS-CoV-2 virus. The sample is quickly dipped into a universal transfer medium to protect the RNA nucleic acid material prior to RNA extraction. Given the difficulty of obtaining reagents in the pandemic, many tests and assays have successfully engineered a workaround RT-PCR assay that avoids the need for RNA extraction, in what is known as extraction-free RT-PCR SARS-CoV-2 assay. After RNA extraction, the reverse transcriptase step helps convert the RNA into a complementary DNA (cDNA) in preparation for PCR amplification. At this step, there are two variants of RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2 detection. One variant is a one-step approach where the reagents for reverse transcription and PCR are in one-pot. Another variant is the separation of the reverse transcription step and PCR step into a two-step approach. Typically, the one-step RT-PCR approach is easier to implement, and require fewer sample handling steps. The cDNA obtained after reverse transcription would be used for PCR amplification aided by binding of primers and probe to appropriate nucleic acid sequence. In a quantitative PCR (qPCR) approach, fluorescence signal from the binding of the probe to PCR amplicons increases with PCR cycle number, and help generate a characteristic qPCR curve that affords identification of positive amplification of target gene. Secondly, the Ct value (which is the cycle number at which the fluorescence signal crosses a pre-defined threshold) helps provide a semi-quantitative measure of viral load in the patient’s sample.

RT-PCR is a mature technology, and many biotech and diagnostic companies as well as universities and research institutes in Singapore step into the fold early in the current pandemic to develop RT-PCR based assays for detecting SARS-CoV-2. As of August 2021, a total of 12 locally designed and manufactured tests have been granted provisional authorisation by the Health Sciences Authority of Singapore. In keeping with international trends in RT-PCR diagnostics for SARS-CoV-2, extraction free diagnostic kits were also developed by Singapore researchers, which significantly reduces sample workaround and analysis time for the diagnostic. Examples of such kits are the Resolute 1.0 and Resolute 2.0 kits. Many of the tests delivered results within the time frame of 1 to 2 hours with sensitivity down to 10 to 20 copies of RNA per reaction. In detecting SARS-CoV-2 infection, multiplex PCR is commonly used, and this is also the case for many of the RT-qPCR tests developed in Singapore. Similar to other tests developed internationally, ORF1ab and N genes are the most common target genes. But, the coronavirus’s spike (S) protein was also a target gene in a three gene multiplex system in one of the tests. All in all, most of the tests were developed for a well-equipped laboratory with trained personnel. However, there are signs that the biotech and clinical diagnostic industry in Singapore is moving towards developing automated analytical tools and systems that complements the SARS-CoV-2 diagnostic kit that they developed. For example, the extraction-free Resolute 2.0 kit could be used with the RAVE automated system. In another example, the VereCoV™ OneMix Detection Kit is designed for use with the VerePlex bioanalytical system. Beyond automation that helps relieve sample preparation pressure especially in mass screening, companies in Singapore are also moving towards developing point-of-care SARS-CoV-2 diagnostics that is especially timely as many countries are trying to use pre-event testing to allow more sectors of the economy to re-open or for more types of events to resume. One example of such point of care COVID-19 diagnostics developed in Singapore is the VitaPCR™ SARS-CoV-2 Gen 2 Assay.

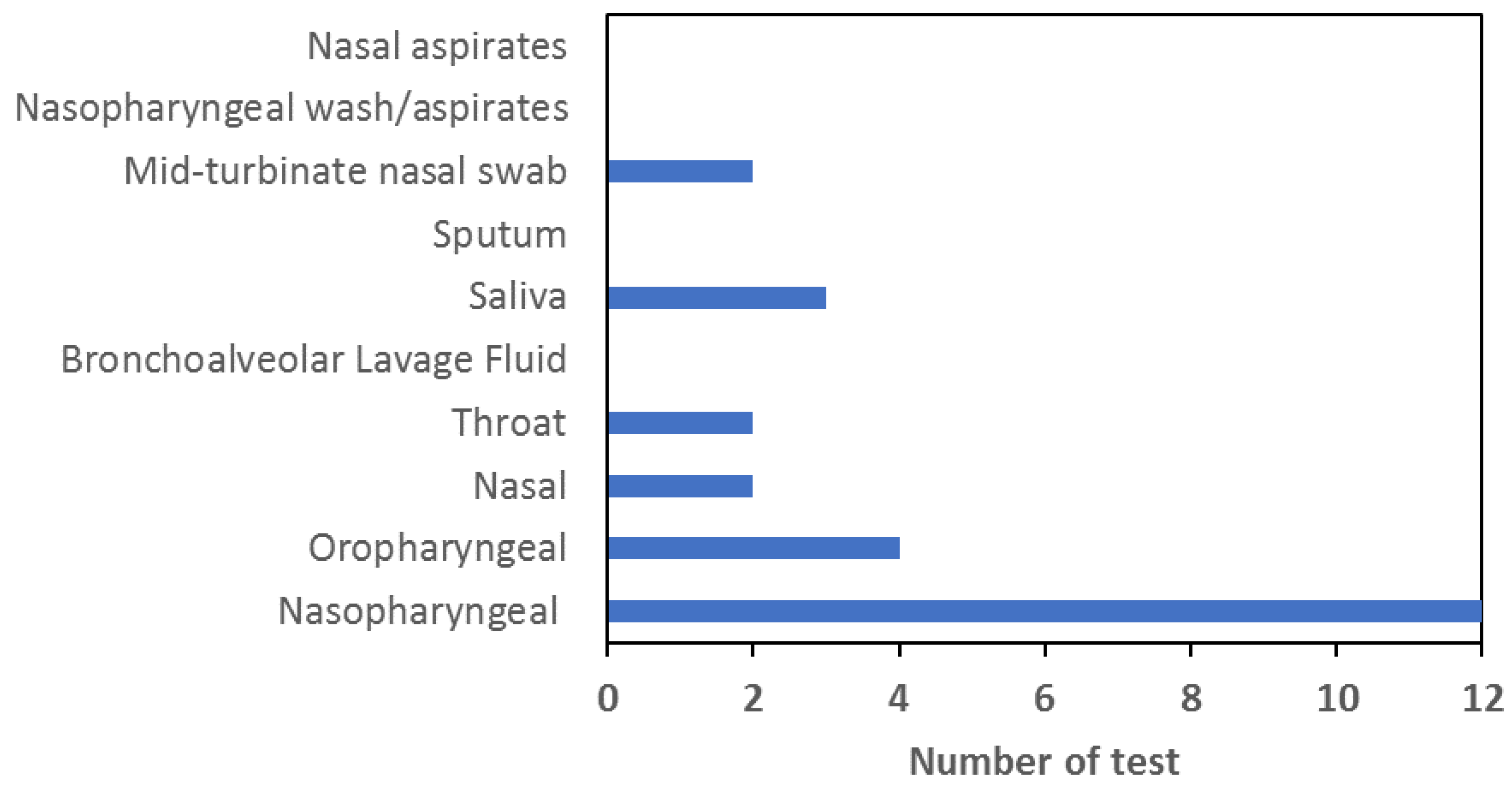

One of the major hindrances towards getting more people to come forward for voluntary testing is the perceived unpleasant nature of nasal swab. Thus, there is an ongoing effort in clinical diagnostics for SARS-CoV-2 to expand the types of samples that could be used for accurate, fast, and easy detection of the virus. But, different types of samples such as those from the throat or saliva carries different fluid elements or enzymes and inhibitors to PCR. Hence, developing a PCR master mix cocktail that could handle or at least ameliorate the potential inhibitors of PCR demands additional chelators or other components that would inevitably add to the cost. In addition, some of the additives that could chelate PCR inhibitors are proprietary or protected by patents, and would thus be not available to biotech start-ups interested to expand the types of samples that could be handled by their diagnostic kits. A meta-analysis of the documentation supplied by companies developing SARS-CoV-2 RT-qPCR test kits in Singapore under the provisional authorisation regiment reveals a preponderance of tests capable of handling nasopharyngeal sample. As can be discerned from the figure, no Singapore developed tests could be applied to nasal aspirates, nasopharyngeal wash/aspirates, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid or sputum sample. In addition, most of the tests could only handle one or two types of samples with nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal being the most common.

Antigen Rapid Tests for SARS-CoV-2 Detection

While molecular nucleic acid-based tests for SARS-CoV-2 provides sensitive and high specificity detection of the virus, the approach typically requires PCR and thermal cycling which requires specialized equipment and personnel to perform the tests. In addition, depending on the number of genes quantified and the length of the amplicons, assay time varies between 1 and 4 hours. The relatively lengthy nature of nucleic acid-based tests thus motivates the development of quicker antibody-based detection of some proteins or fragments of a virus in what is known generally as immunochromatographic antigen rapid test. Such tests are specific given the highly specific nature in which antibodies bind to the target antigen.

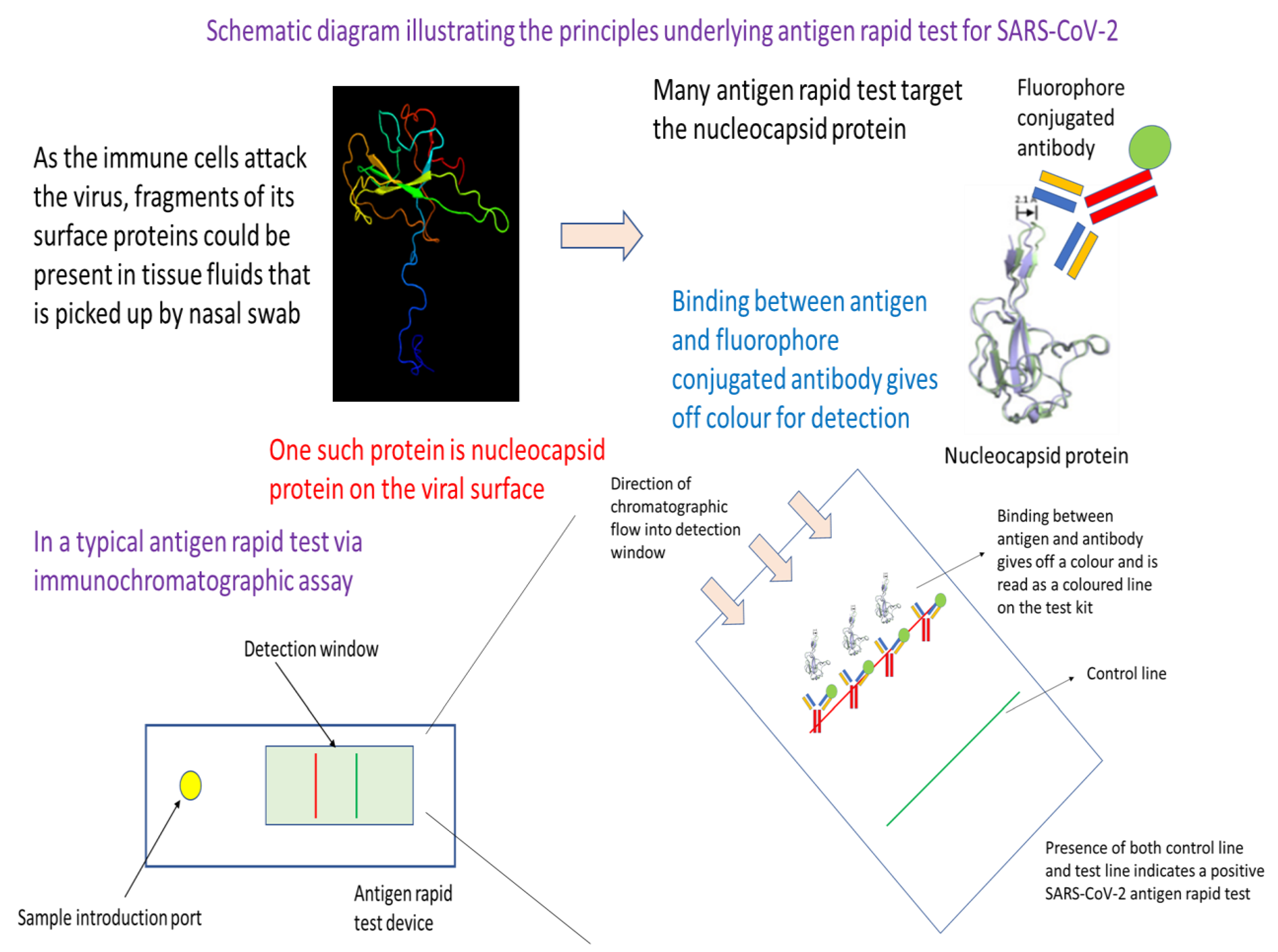

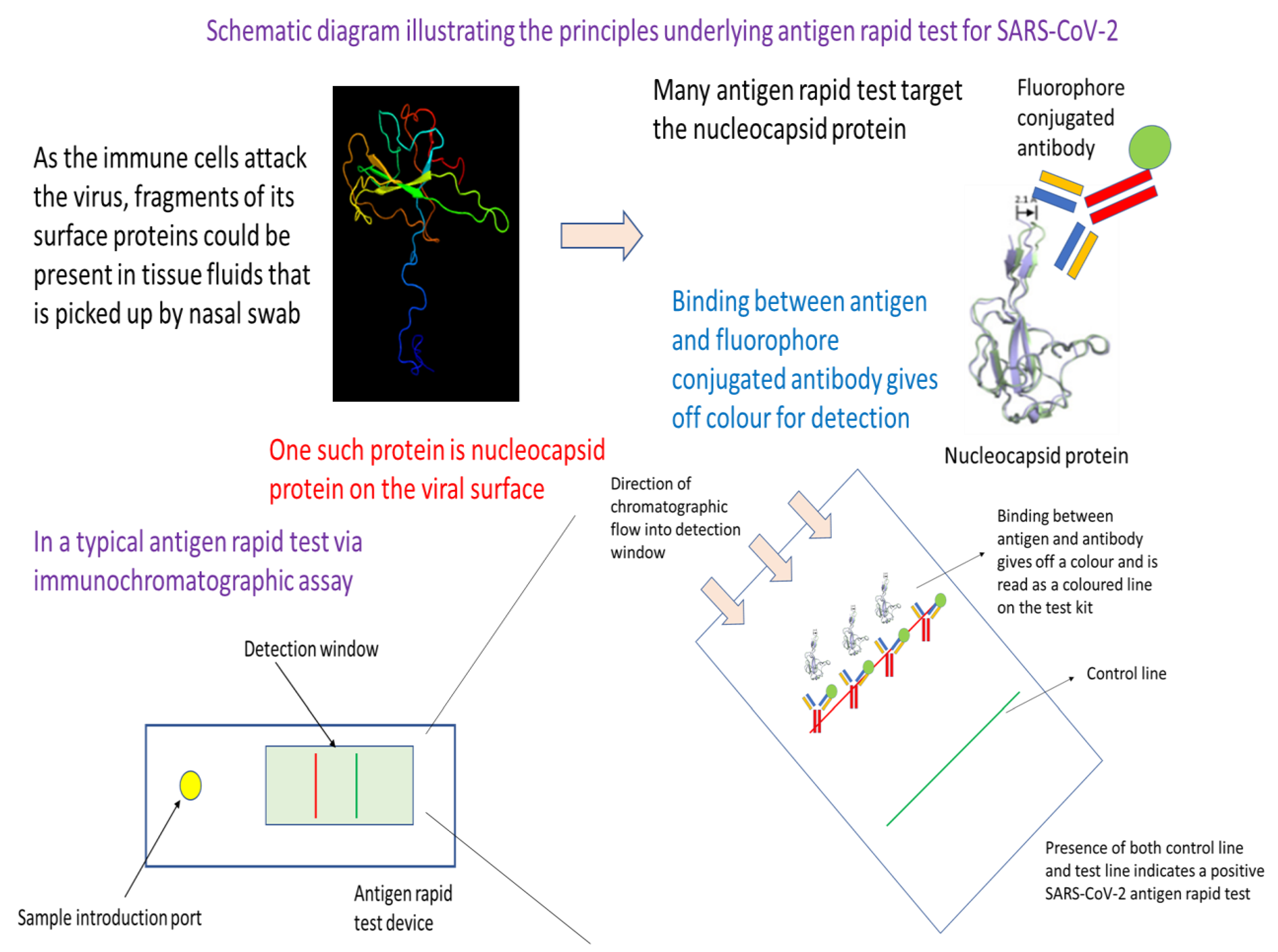

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram illustrating the underlying principles of antigen rapid test for SARS-CoV-2. In essence, this testing approach utilizes the specificity in binding between an antibody and an antigen of SARS-CoV-2. Readout is through an antigen-antibody binding mediated release of colour or fluorescence that is visible or which could be detected by an instrument or plate reader. The approach starts off with the collection of a nasal swab. After dipping into a transfer medium, the sample is then added to the sample introduction port of a antigen rapid test device. Capillary action from the lateral flow device moves the sample fluid down the chromatographic channel in the membrane. Binding of the antigen with its complement antibody at the detection line would result in colour formation or fluorescence that is indicative of a positive test. Emergence of the control line would indicate that the test has been successfully carried out, and the reagents have covered the full length of the testing window of the device.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram illustrating the underlying principles of antigen rapid test for SARS-CoV-2. In essence, this testing approach utilizes the specificity in binding between an antibody and an antigen of SARS-CoV-2. Readout is through an antigen-antibody binding mediated release of colour or fluorescence that is visible or which could be detected by an instrument or plate reader. The approach starts off with the collection of a nasal swab. After dipping into a transfer medium, the sample is then added to the sample introduction port of a antigen rapid test device. Capillary action from the lateral flow device moves the sample fluid down the chromatographic channel in the membrane. Binding of the antigen with its complement antibody at the detection line would result in colour formation or fluorescence that is indicative of a positive test. Emergence of the control line would indicate that the test has been successfully carried out, and the reagents have covered the full length of the testing window of the device.

The logic for the design of an antigen rapid test comes from the realisation that it is possible to use specific antibody to recognise some surface proteins of a virus, or fragments of a virus resulting from immune attack on the virus. Such recognise can happen at room temperature over a relatively short span of time without the aid of specialized analytical instrument. Readout of the test could be calorimetric, which meant that such antigen rapid tests could be deployed at home or point-of-care or for pre-event screening. The key to mass adoption of such tests is in developing the technologies and methods for manufacturing these antigen rapid tests cheaply.

Generally, antigens selected for antigen rapid test detecting viral infections are usually viral surface proteins. Present on intact virus or fragments of virus resulting from immune system attack on the virus, these viral surface antigens are good targets for the development of specific antibodies that in recognising them help provide calorimetric reading for an antigen rapid test. In the current SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, viral nucleocapsid protein (or N protein) is commonly the target antigen for detecting the presence of intact virus or viral fragments. Antibody used to recognise the N protein is typically conjugated to a fluorophore, which would emit a calorimetric signal upon binding to capture antibodies at the test line of the immunochromatographic lateral flow assay device. To help avoid the need for specialized equipment such as PCR thermocycler, antigen rapid tests are typically built on mature lateral flow assay format commonly used in pregnancy test kits. The principles are the same, but what differs are the antibodies used as well as the method for emitting calorimetric signal.

In a typical antigen rapid test, the nasal swab sample is dipped into a combinatorial test solution that help bring the antigen protein or fragments of the virus containing the antigen into the test solution. The test solution contains specific antibodies that target the viral surface antigen of interest, which in this case is the nucleocapsid protein (N protein). Binding of the antibody with the target antigen then create an immunocomplex that latter would be captured by the capture antibodies at the test line of the test device. The next step in the test procedure involves dropping an approximate 4 drops of test solution with dipped nasal swab sample into the sample well of the antigen rapid test. Through rapid capillary action, the test solution containing the aforementioned immunocomplex will migrate towards the nitrocellulose membrane where there are different capture antibodies at the test and control line. Capture antibodies at the control line profile for a control human antigen that provides feedback on whether the test procedures have been performed correctly. If a coloured band is visible at the control line after a defined period of about 10-15 minutes, then the test has been performed correctly and is valid. In the case of the test line, capture antibodies there would recognise any aforementioned immunocomplex between target antigen and antibody. Presence of immunocomplex would result in a binding event at the test line, and resulting emission of a calorimetric signal which is visible as a coloured line. Together, presence of coloured bands at the test and control line meant that the test result is positive, and the patient’s sample has intact SARS-CoV-2 virus or fragments of the virus.

Antigen rapid test is a frontline tool of Singapore’s effort to contain the spread of SARS-CoV-2. Deployed at entry checkpoints and also available as a self-test kit for retail sale at pharmacies around the city-state, antigen rapid test (ART) provides fast, reliable result to aid in pre-event screening as well as an initial screen at home to assess infection status. Currently, there are 4 ART tests developed in Singapore. All of them uses the sandwich lateral flow assay format described above with colloidal gold technology for providing calorimetric readout. Nucleocapsid protein is the antigen that these tests profile for in detecting SARS-CoV-2 infection. In terms of types of samples that could be used with these tests, nasal swab and nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal are still most common. But, an ART test developed by Camtech Diagnostics uses throat swab sample as input. Finally, all the ART tests deliver fast results within 10 to 15 minutes.

Antibody Test for Testing Immunological Reactions to SARS-CoV-2 Infection

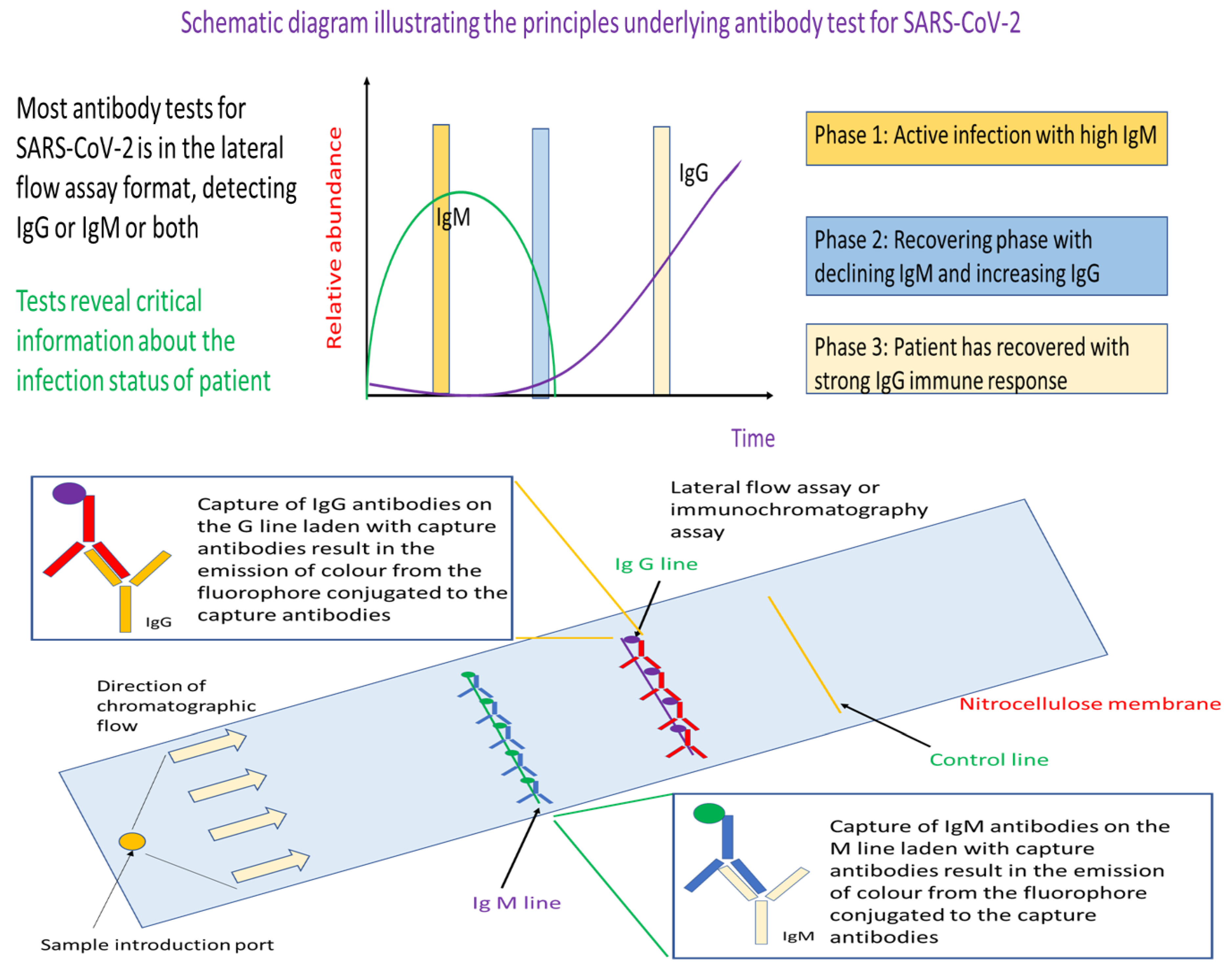

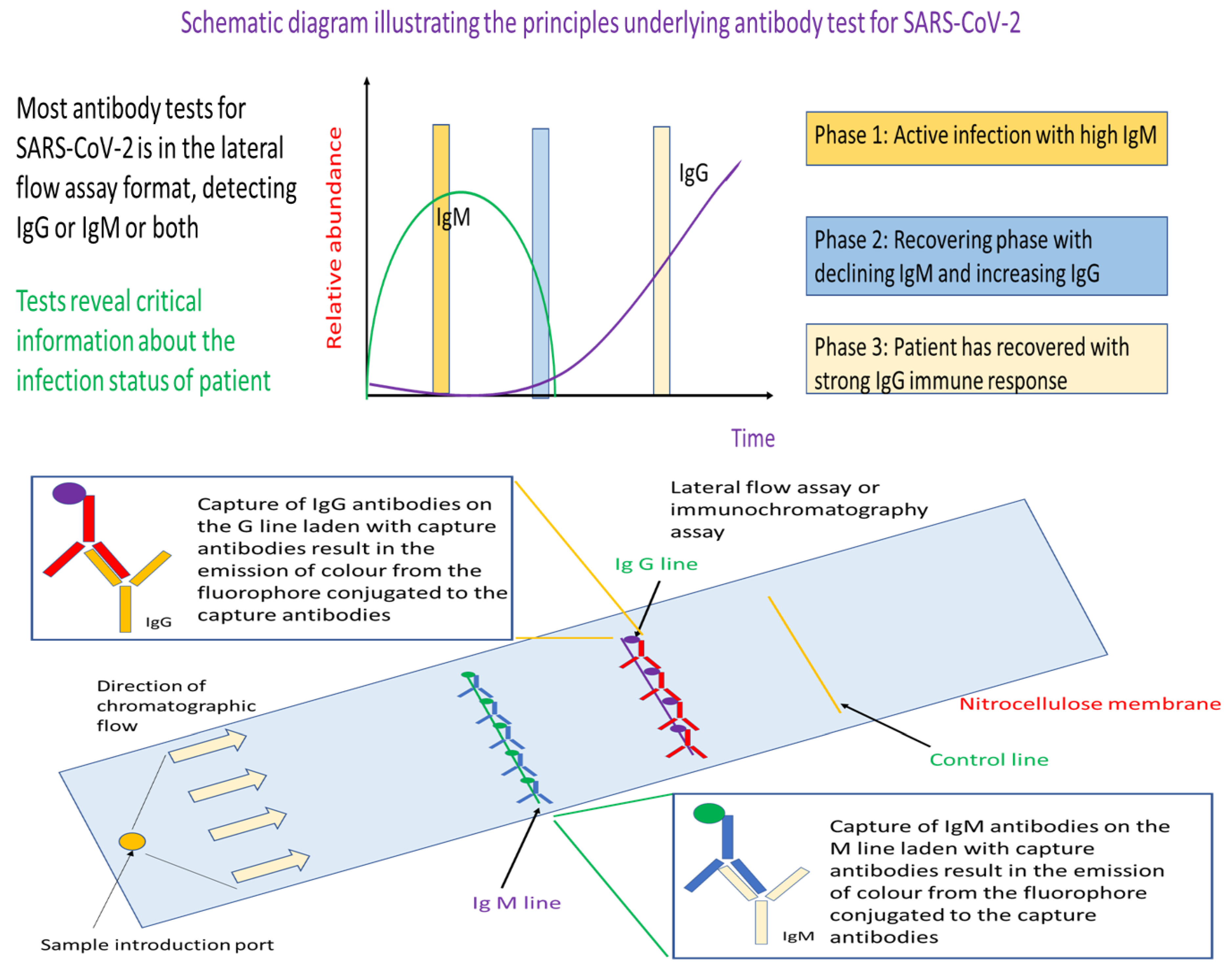

Up until now, the focus has been on technologies that perform direct detection of the virus either through detecting surface viral protein of the virus or testing for presence of the virus nucleic acids. But, there is another approach of testing which can, in addition, to providing evidence of whether a person has SARS-CoV-2 virus, also probe for the strength of the immunological reaction provoked by the virus. The latter is of particular importance for infection control and patient treatment given that different control strategies and treatment options are available for patients either in the active infection phase or someone who are partially recovered from the viral infection. In general, such antibody tests profile for IgM, IgG or both. Presence of IgM and no IgG represents the active phase of infection where the patient is infectious. As the patient’s immune system is activated to fight the virus, there will be production of IgG followed by a decline in IgM. Hence, detection of IgG and relatively little IgM meant that the patient is recovering from the viral infection and is less infectious.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram illustrating the key principles underlying the antibody (serology) tests for detecting active infection cases and recovering patients of SARS-CoV-2. This test has a strong immunological basis where it seeks to detect the type and concentration of antibody typical of different immune response to assess the infection status of an individual. Specifically, if IgM is detected predominantly, the individual is still in the active infection phase. On the other hand, detection of IgG with no or little IgM indicates that the person has prior exposure to the virus and is recovering. In essence, the workflow starts with a blood draw with the plasma fraction is isolated to serve as sample for this antibody test. The sample is added to the sample introduction port of the lateral flow assay device. Capillary action will move the sample fluid towards the antibodies that would bind IgM or IgG. Such binding would result in colour formation at the IgM or IgG line that would serve as readout for the test. Emergence of the control line would indicate that sufficient sample fluid has reach the line, and the test is working properly.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram illustrating the key principles underlying the antibody (serology) tests for detecting active infection cases and recovering patients of SARS-CoV-2. This test has a strong immunological basis where it seeks to detect the type and concentration of antibody typical of different immune response to assess the infection status of an individual. Specifically, if IgM is detected predominantly, the individual is still in the active infection phase. On the other hand, detection of IgG with no or little IgM indicates that the person has prior exposure to the virus and is recovering. In essence, the workflow starts with a blood draw with the plasma fraction is isolated to serve as sample for this antibody test. The sample is added to the sample introduction port of the lateral flow assay device. Capillary action will move the sample fluid towards the antibodies that would bind IgM or IgG. Such binding would result in colour formation at the IgM or IgG line that would serve as readout for the test. Emergence of the control line would indicate that sufficient sample fluid has reach the line, and the test is working properly.

Different from RT-PCR and antigen rapid tests, antibody tests rely on whole blood, plasma or serum as samples. The assay format is an established lateral flow assay, where we have the technologies to manufacture at a relatively low price-point for mass deployment such as during the event of a pandemic. In a typical assay, the sample is injected into the sample introduction port of the lateral flow assay. The sample will be move through capillary action through the nitrocellulose membrane where the IgM and/or IgG antibodies will be separated captured by fluorophore conjugated anti-IgM or anti-IgG antibodies at the respective IgM and IgG line. As the respective capture antibodies are conjugated with fluorophore, binding of the target antibodies such as IgM or IgG would result in emission of colour that is visible as a coloured band on the test device at the respective test lines.

In contrast to antigen rapid test, serological antibody tests for determining the infection status of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Similar to ART, a total of 4 antibody tests were developed by Singapore companies. All profile for IgM and IgG antibodies for SARS-CoV-2 in a single lateral flow assay format. This is a proven technology that is of open-architecture, which means that it could be adapted to detect other pathogens of concern in future simply by changing the antibodies used on the nitrocellulose membrane. Finally, except for one test, all tests developed in Singapore could be used with whole blood, serum or plasma sample, which is significant given the difficulty to analyse whole blood samples. Ability to analyse whole blood sample without prior sample preparation also meant that the antibody body tests could be used as point of care devices, which helps expand the use scenario of these tests to the common clinic. Availability of antibody test results at the clinic level provides the general physician with a better view of the infectious status of the patient’s with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Using Breath to Detect Volatile Organic Compounds Unique to Patients with COVID-19

Rapid mass screenings and pre-event testing are requisite for safe reopening of many aspects of economic and social life in cities around the world during this pandemic. But, current diagnostic tests for SARS-CoV-2 still require fairly elaborate sampling and sample processing steps prior to the actual test even for the case of antigen rapid test. Clearly, RT-PCR, antigen rapid test and antibody tests are not suitable as diagnostic tool for mass screenings at airports or other point of entries. What is needed is a diagnostic modality that is equivalent in speed to a temperature screen by infrared camera, is low-cost, and requires little or no sample processing steps. This then motivates the development of breath analysis as a modality for detecting SARS-CoV-2 given the presence of unique volatile organic compounds in the breath of patients with COVID-19.

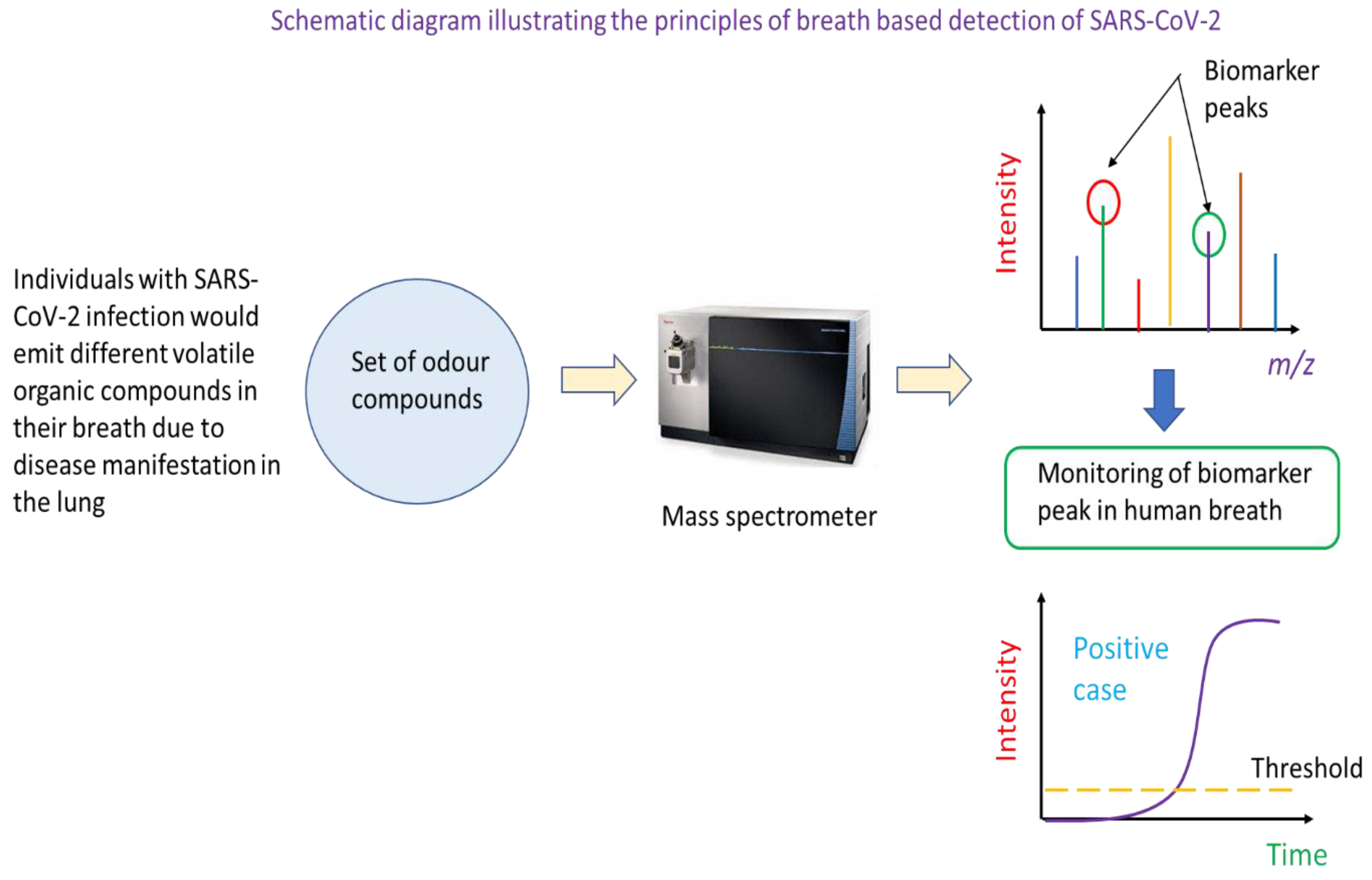

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram showing the principles underlying breath-based analysis of volatile organic compounds for SARS-CoV-2 infection detection. Individuals with SARS-CoV-2 infection may have a unique set of volatile organic compounds in their breath. This then constitutes the basis for the identification of infected persons using mass spectrometric analysis. In this detection modality, a suspected case would be asked to breathe into a breath analyser. This would be drawn into a mass spectrometer which has been programmed to monitor the ion count (or intensity) of specific mass to charge ratio ions. These ions are biomarkers of SARS-CoV-2 infection as they are volatile organic compounds resultant from the infection. A positive case would be called if the ion counts of specific mass ions are above a threshold for a specified analysis duration.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram showing the principles underlying breath-based analysis of volatile organic compounds for SARS-CoV-2 infection detection. Individuals with SARS-CoV-2 infection may have a unique set of volatile organic compounds in their breath. This then constitutes the basis for the identification of infected persons using mass spectrometric analysis. In this detection modality, a suspected case would be asked to breathe into a breath analyser. This would be drawn into a mass spectrometer which has been programmed to monitor the ion count (or intensity) of specific mass to charge ratio ions. These ions are biomarkers of SARS-CoV-2 infection as they are volatile organic compounds resultant from the infection. A positive case would be called if the ion counts of specific mass ions are above a threshold for a specified analysis duration.

Mass spectrometry is the instrumented analysis technology that powers breath-based detection of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Specifically, the breath of individuals with SARS-CoV-2 infection is different in the types of volatile organic compounds present, and this can be determined through a broad-spectrum scan of compounds in the breath of healthy and infected persons. Mass ions unique to infected persons could serve as biomarkers diagnostic of SARS-CoV-2 infection. In the application of the technique to real samples, the mass spectrometer would be tuned to monitor the number of molecules of particular mass to charge ratio in the person’s breath (i.e., the ion count of a biomarker mass ion). Such monitoring can be captured and display as real-time ion intensity count on the instrument’s screen. Once the ion count of the mass ion biomarker peak is above a pre-determined threshold, the person could be identified as a potential COVID-19 positive test. But, a confirmatory RT-PCR test is needed to confirm COVID-19 infection. Currently, two companies, Breathonix Pte Ltd and Silver Factory Technology Pte Ltd are developing and refining the breath test for SARS-CoV-2 detection. Provisional use authorisation has been obtained for Breathonix, and the test has been deployed for use at the land check-point between Singapore and Malaysia [

1]. Silver Factory Technology uses a different approach that rely on surface-enhanced Raman scattering to detect specific volatile organic compounds in the breath of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection [

2].

Diagnostic Tests in Development in Singapore

Besides the diagnostics test described above, research is underway in Singapore to develop cheaper, faster, more accurate diagnostics, particularly for the point-of-care settings given the recent emphasis of testing in combination with vaccination as the two-pronged strategy to resume more social and economic activities as the pandemic progressed into its third year. Efforts in this direction include the development of CRISPR-based tests for faster, more precise, and sensitive detection of SARS-CoV-2 as well as microfluidic devices to bring the typical lab-based RT-PCR assay to the point-of-care.

In the area of CRISPR-based test, researchers in Singapore are refining the technique to make the test simpler and deployable at the point-of-care as well as able to profile for SARS-CoV-2 variants. One effort is the development of VaNGuard CRISPR-based SARS-CoV-2 test. Specifically, this test is designed to pick out variants of SARS-CoV-2 through specific guide RNA targeting each variant. Different from conventional RT-PCR, the method only requires isothermal heating at 60 to 65

oC for about 22 minutes to amplify the target nucleic acid. If target amplicons are present, these would be cleaved off by the Cas protein through recognition by the guide RNA in the subsequent incubation step. Finally, a paper test strip is dipped into the reaction mixture to provide readout where presence of two bands is indicative of a positive test [

3]. Use of a paper-based test strip and lack of thermocycler meant that VaNGuard may be amenable to point-of-care application. Sensitivity of the test is about 50 copies of RNA per reaction, which is an order of magnitude less sensitive than the gold standard RT-PCR test.

Separately, Singapore researchers are also working hard to develop analytical instrumentation that could bring RT-PCR assay to the point-of-care at a cheaper price-point. Specifically, a microfluidics chip-based RT-qPCR device known as Epidax is under development to expedite the RT-qPCR process to within 1 hour. Compatible with either extraction or extraction-free assays, the method has been shown to be useful for detecting SARS-CoV-2 [

4]. The system uses micro-channels to perform different steps prior to PCR amplification. More importantly, a special reagent is used to perform RNA extraction on chip that eliminate the need to conduct manual RNA extraction. Device uses fluorescence detection to obtain readout of PCR test. The current sensitivity of the system is 10 RNA copies per microlitre of sample.

Similarly, Cell ID in Singapore has also developed a point-of-care laptop powered real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction biochip that runs either the RT-PCR assay or the isothermal reverse transcriptase loop mediated isothermal amplification (RT-LAMP) assay. The test requires 10 µL of nasal swab or saliva as specimen, and can deliver a positive result in 5 minutes, and a negative result is returned within 1 hour [

5]. Available as a palm-sized device that could be powered by a laptop, the test could offer general practitioner a point-of-care polymerase chain reaction type of COVID-19 test.

Conclusions

Technology has often come to the aid in infectious disease control in the modern era. Starting with SARS in 2003 and continuing on to the current SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, modern medicine is closely intertwined with technology development in diagnostics and treatment. Diagnostics, in particular, stood out in the COVID-19 pandemic given the peculiar characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 in high transmissivity and delayed onset of symptoms, which calls for early identification of cases and subsequent quarantine and isolation. While technologies developed in the past decade to detect SARS infection could be used to detect SARS-CoV-2 in the early phase of outbreak due to the similarity in nucleic acid sequence and structure of surface proteins between the two coronaviruses, new technologies and methods are needed to first rapidly detect new cases as well as cope with the expanded capacity needed in a global pandemic.

With supply disruptions and time pressure to rapidly contain the virus, it is inevitable that the world turned to established technologies to help expedite assay development to combat the new virus. Such technologies include RT-PCR and lateral flow assays. Specifically, RT-PCR technologies matured and declined in cost in the years prior to the current outbreak, and the world is fortunate to have ready a technology that could deliver sensitive and specific detection of SARS-CoV-2 at the outset of the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak. More importantly, the lateral flow test that powers home pregnancy test kit lays the foundation for the development of a suite of antigen and antibody immunochromatographic tests for SARS that could be adapted for SARS-CoV-2 detection. Indeed, lateral flow assay-based antigen rapid test has become the go-to testing tool for aiding pre-event screenings and serving as front-line detection at points of entry due to the failure of conventional temperature screening to detect SARS-CoV-2 positive cases with delayed symptoms. Similarly, antibody-based test relying on lateral flow assays provide clinically important answers to ascertain the infection phase of a positive case, which helps formulate an appropriate treatment plan for the individual as well as inform necessary isolation and quarantine measures during treatment at a care facility.

Although established technologies lead the way in the development of specific diagnostics for SARS-CoV-2, this pandemic has also saw the development of new modalities in diagnosing viral infection. One interesting route that is likely to become important in future is the more widespread use of isothermal amplification in polymerase chain reaction. Able to operate without a thermocycler, such assays make RT-PCR closer to the point-of-care, which is important given the myriad applications that the diagnostic tool is able to offer to the clinician. Another technology to watch is the use of breath tests to profile for specific biomarkers in the ensemble of volatile organic compounds in a patient’s breath. Once clinically validated, such volatile organic compounds could be robust biomarkers for rapid and sensitive detection of positive cases that do not manifest an elevated temperature in fever. Current RT-qPCR assays rely on a calorimetric or fluorometric readout enabled by sophisticated optics, possibilities exist in using CRISPR-based detection to deliver an analytical calorimetric readout in a lateral flow assay format. This is particularly important given the expensive nature of optical readout, but CRISPR-based technologies also offer an added dimension of specificity and versatility compared to conventional probe technology in RT-qPCR where expensive fluorophore are conjugated to probe molecules. In place of probe molecules are guide RNA that could be easily “reprogrammed” to new target gene and variants in less time. Finally, converting the conventional PCR tube-based assays into the microfluidic chip format that may become automated is another technology poised to gain importance in future.

Overall, years of investment in development of various types of clinical diagnostics based on PCR and lateral flow assays have laid down a strong intellectual foundation and have built strong capabilities in diagnostic design and development in Singapore. Thus, Singapore was relatively well-positioned to develop its own RT-qPCR test kit for SARS-CoV-2 detection early in the pandemic. Later, companies in Singapore’s biotech scene also developed antigen rapid test and antibody tests based on the established lateral flow assay format. Besides these technologies, the biotech sector in Singapore is also focusing on developing chip-based solutions for a variety of modalities ranging from RT-PCR to breath tests. But, a broader theme remains: i.e., the development of faster, cheaper, and more reliable test especially in the point-of-care context.

Materials and Methods

The raw data that goes into this review manuscript comes from documentation deposited by the different companies with the Health Sciences Authority of Singapore as well as academic journal articles retrieved by Google and Google Scholar search. Documentation deposited with the Health Sciences Authority of Singapore are those seeking provisional use authorisation for the kit or assay. These data for each kit and company were used alone or in aggregate to derive other useful parameters that help provide a better picture of the state of the art of COVID-19 diagnostics developed in Singapore. An example of which is the use of type of samples that could be used with each test kit to help derive the aggregate statistic that informs on the sample type that is most compatible with RT-PCR test kits developed in Singapore.

Funding

No funding was used in this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).