1. Introduction

Carbon nanotubes define the dielectric properties of polymer nanocomposites, electrical conductivity of the carbon nanotubes, its aspect ratio, as well as dispersion in the polymer. The sensor is one of the potential applications of polymer nanocomposites having carbon nanotubes. The dielectric loss can be determined from the measurements of their dielectric properties such as complex permittivity, ac and dc electrical conductivities, impedance, and tan loss. Nanofillers such as carbon nanotubes (CNTs) have risen as a promising alternative to the high amount of carbon black that is required to obtain optimum reinforcing properties [

1]. CNTs at low percentage content provide high mechanical and electrical properties that carbon black provides at high filler content [

2]. Therefore, CNT are often used as a reinforcing nanofiller to improve the properties of polymer composites [

3,

4]. The incorporation of CNT nanofillers significantly improves the mechanical and electrical properties of rubber nanocomposites [

5]. However, the use of a high amount of CNT may lead to lower properties due to CNT aggregation in the rubber matrix [

6,

7]. Significant progress is also being made in CNT dispersion, processing, and their use in silicone rubber. Solution mixing is preferred as it leads to uniform dispersion of CNT in a silicone rubber matrix [

8]. Studies report that the reinforcement of silicone rubber with CNT hybrid fillers leads to higher electrical sensitivity [

9]. The effect of the purity of CNT in silicone rubber was also studied, and the results show that CNT with high chemical purity show higher mechanical and electrical properties [

10]. In recent years, dielectric materials have attracted a great attention on account of their potential applications such as electric energy storage devices, dielectric actuators, and sensors. to name a few. The feature of dielectric materials is to transmit, store, and record the effects of electricity in the form of electric polarization, that is, electric field induced separation and alignment of electric charges. As the real application of dielectric materials, dielectric constant, and dielectric loss are the two main points focused as the large dielectric constant and low dielectric loss are demanded [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. It has been cleared that Polymers are typically immiscible and usually acquire a small-scale arrangement of the phases when mixed together because of the unfavorably low mixing entropy. “Double percolation” formed by co-continuous structure of immiscible polymer system has been investigated to achieve higher electrical conductivity with reduced conductive filler content “carbon nanotubes” and decreased percolation threshold [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Thus, this paper has been studied dielectric properties of silicon rubber in presence of carbon nanotubes with variant thermal conditions (up to 40 °C). In this study, the effect of carbon nanotubes (CNTs) on the microstructure, electrical conductivity and relative dielectric permittivity of silicon rubber nanocomposites were investigated with variant thermal temperatures over all frequencies up to 1 kHz. The proposed experiment samples take into account the different between tradition silicon rubber and the new SR/MWCNT nanocomposites that are used as sensors applications. Also, this research success for specifying optimal dielectric properties of variant thermal conditions for enhancing polymeric insulations for sensors applications. It has been investigated dielectric properties (dielectric constant, modulus, dielectric loss) with variant thermal temperatures over all frequencies up to 1kHz. Virgin and compressed samples explain the operation state of materials before and after usage for a long-life time.

2. Characterization and Material Design

Polymer composites with CNTs investigated in recent research exhibited improved thermal stability, and thus some research aiming to clarify the mechanism of the improvement by CNTs has been conducted [

26,

27,

28]. In recent years, dielectric response technology has attracted more and more attention as a non-destructive test method on insulating materials. The polarization and depolarization current (PDC) measurement in time-domain is especially suitable for the on-field diagnosis of electrical equipment because of its fast, accurate and abundant test information [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33].

2.1. Nanostructure Materials

Monitoring of structures constantly for crack initiation and propagation is a critical issue for reducing inspection costs and increasing safety. The MWCNTs (procured from Nanostructured and Amorphous Materials, Inc. USA) used with RTV-SR are relatively short (10–50 _m), 8-15 nm diameter (density 2.1 g/cm

3), with surface area 230 m

2/g (> 95% purity) less tangled, and quite straight. In this research, the maximum MWCNT’s loading was limited to3.0 wt.% (2.16 vol%) of MWCNT in liquid SR. Two component silicone elastomer which cures at room temperature by a poly addition reaction (commercially known as BLUESIL RTV 3428 A&B) is used as received. The density of both SR component is 1.1 g/cm

3 whereasthe viscosities of RTV-A and RTV-B are 25,000 and 8000 mPa.s, respectively. At low CNT concentrations in the nanocomposite, large conductivity fluctuations may occur due to the strong influence of destruction and formation of conductive paths [

23]. When using MWCNTs, the main problem is their characteristic property of agglomeration due to their physical size and the van-der Waals forces between the nano particles. Using surfactants (e.g., poly carboxylic acid or sodium dodecylbenzene sulfonate NaDDBS) and low-power, high-frequency (12 W, 55 kHz) sonication for 16–24 h is required to achieve MWCNTs dispersion in polymer, which are normally very elaborate and complicated. The SR/MWCNT nanocomposite samples are prepared according to the weight percent (wt.%) of the MWCNTs and SR. The samples are produced by melt-mixing of MWCNTs with SR without surfactants using a laboratory mixer with a high shear mixing blade. The tendency of MWCNTs agglomerations in polymer matrix may be minimized by appropriate application of shear during the melt-mixing [

24,

25]. It is shown that a good dispersion and wetting of the MWCNTs can be achieved with RTV polymer by the shear mixing. It is useful to mention that the viscosity of the mixture increases with the increasing wt.% of the carbon nanotubes. When MWCNTs are visibly wetted-out, the mixing speed is gradually increased until the mixture exhibits no visible signs of lumps. After 4 min of cooling, RTV-B is added and mixed at low speed for two minutes. The SR/MWCNT blend is then poured into molds with different forms according to the desired shape and size of the flexible sensor.

2.2. Fabrication Materials

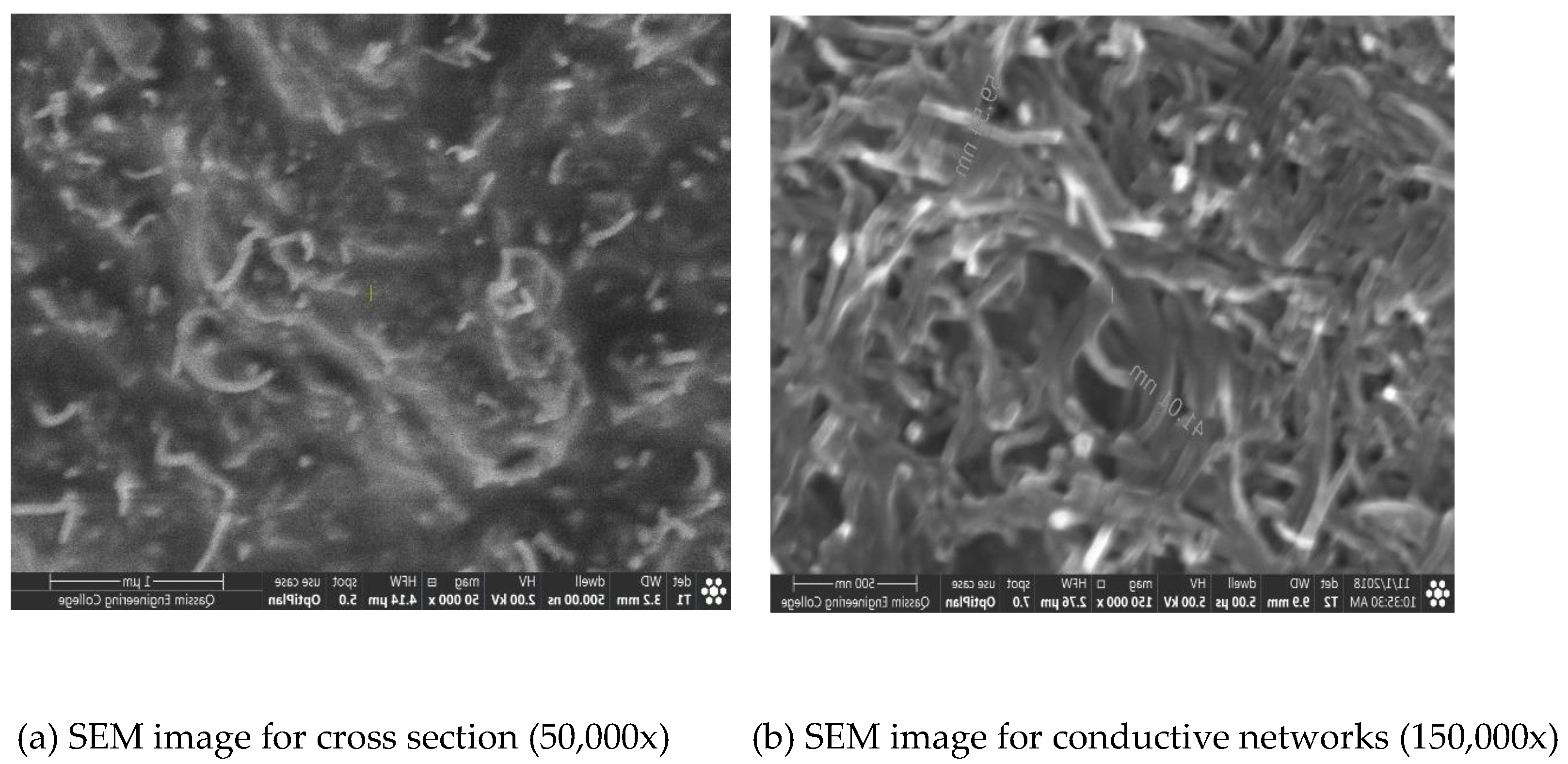

The high electrical, dielectric and mechanical properties have been improved in thermal conditions and thermal stability with attractive of high-performance CNTs. The MWCNT’s dispersion inside the cured RTV (rubber silicone) is examined by SEM using a FEI-Apreo Electron Microscope, operating at 2.0 and 20 kV. The SR/MWCNT samples are prepared to SEM investigation by immersing small trimmed pieces from molded blocks (dimensions 5 × 5 × 2 mm) in liquid nitrogen at room temperature and then fracturing the frozen pieces laterally into two pieces such that the fracture surface is perpendicular to the electric current direction to show the SR/MWCNTs phase and the RTV polymer phase. The morphology of the cross-section area of this fractured piece in

Figure 1a shows how the carbon nanotube networks are embedded within the silicon rubber matrix. The shapes of the nanotubes. SEM image in

Figure 1b shows the morphology of the SR/MWCNTs sample at higher magnification to show the uniform spatial distribution of individual MWCNTs that result in the high conductivity of the SR/MWCNT nanocomposites. One of the two fractured pieces is fractured again in a direction perpendicular to the first fractured cross section area to reveal the convolution, entanglement and the degree of alignment of MWCNTs within the conductive networks in the SR as shown in

Figure 1c; The explored area reveals the well dispersion and the high density of the MWCNTs conductive networks within the polymer matrix.

2.3. Fabrication Test Samples

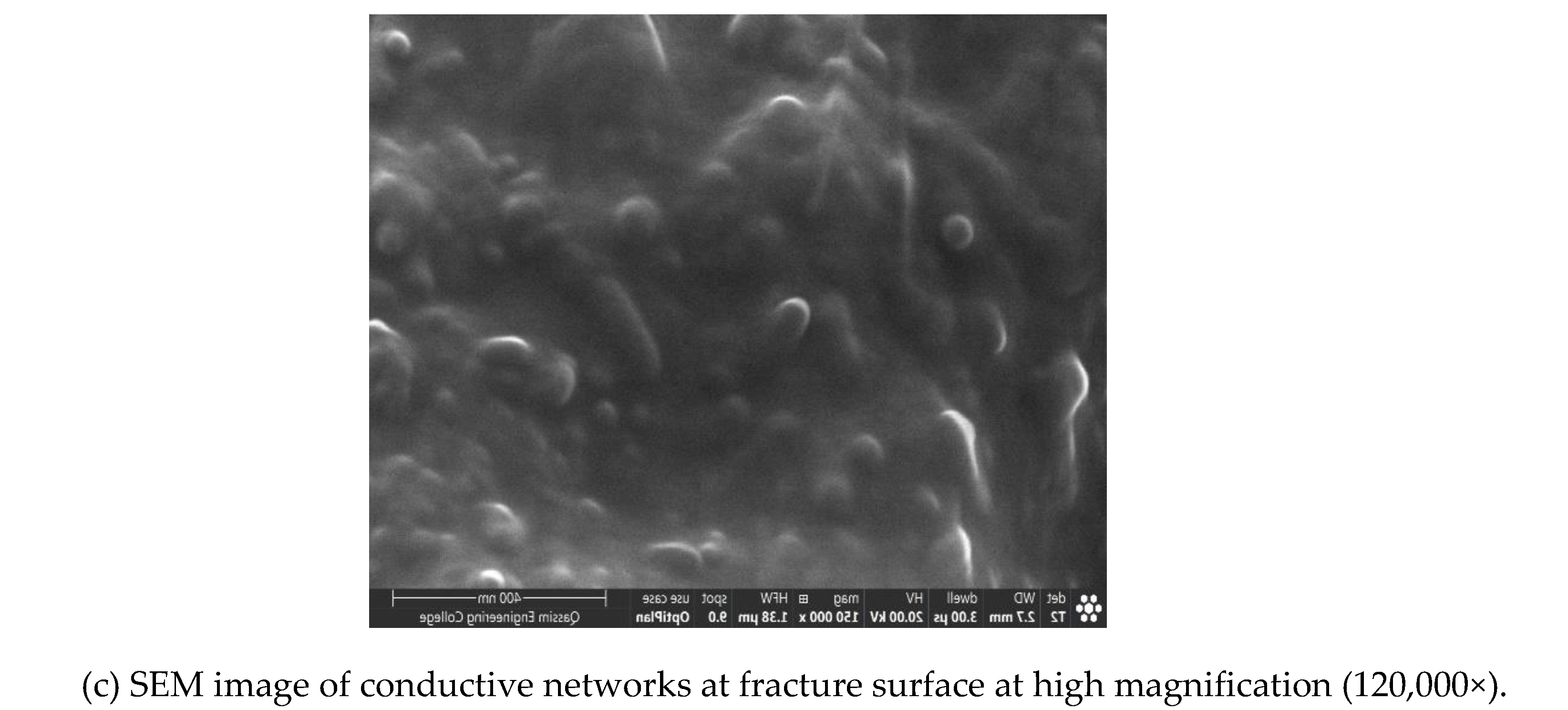

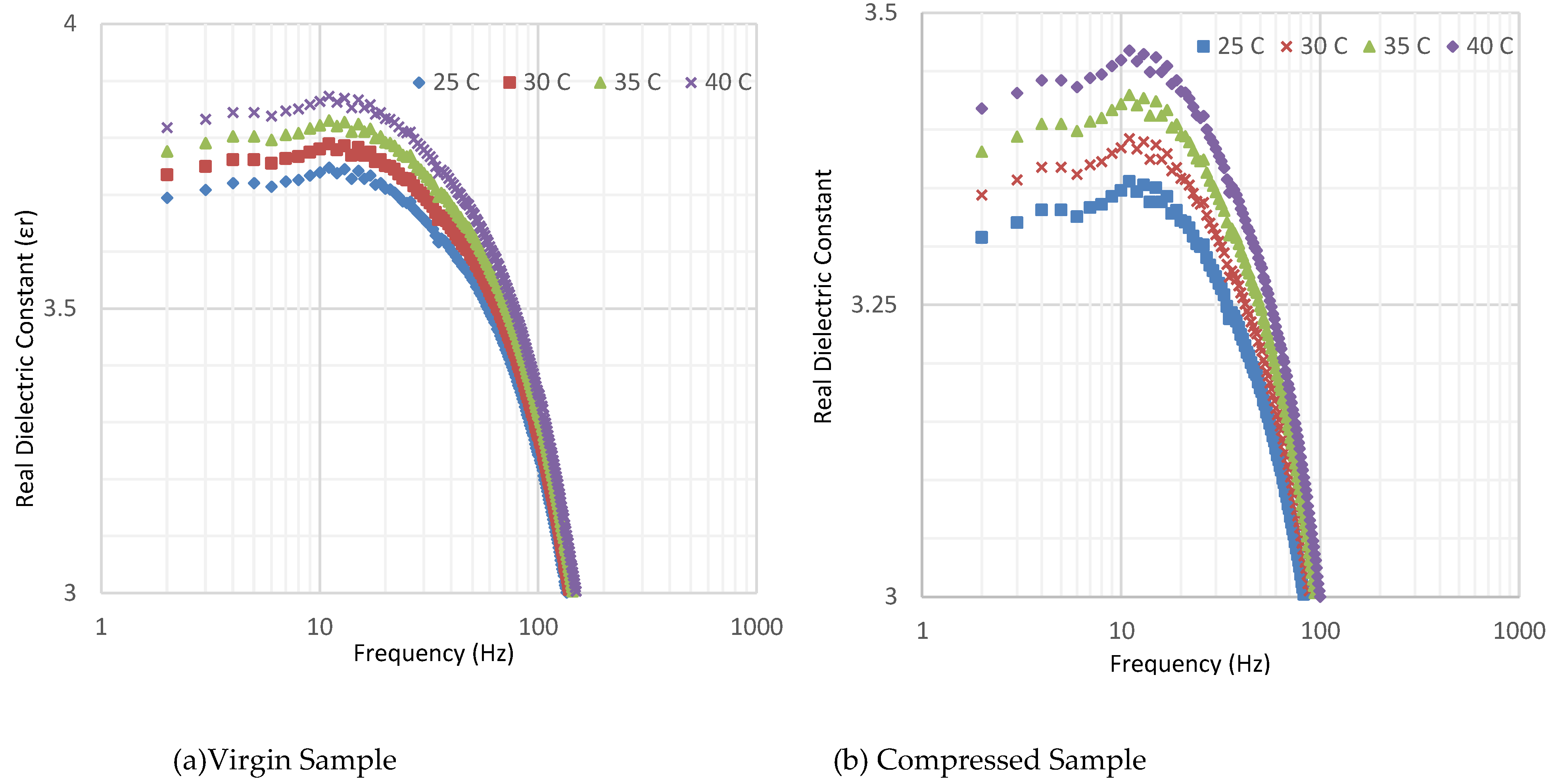

Fabrication prototypes of nanocomposite samples are made either by slicing or trimming of the desired shapes and sizes from the SR/MWCNT molded block or directly by molding the desired shape and size of the RTV.

Figure 2a shows different shapes and dimensions of sliced and trimmed SR/MWCNT samples from molded block B. The dimensions of trimmed sensors in

Figure 2b range from 1 × 2 × 12 mm (it can be used as strain sample for axial tension) to 4 × 4 × 12 mm (it can be used as bending force sample).

3. Characterization & Measurements

Dielectric Spectroscopy is a powerful experimental method to investigate the dynamical behavior of a sample through the analysis of its frequency dependent dielectric response. This technique is based on the measurement of the capacitance as a function of frequency of a sample sandwiched between two electrodes. The resistance (R), inductance (L) and capacitance [C] were measured as a function of frequency in the range of 0.1 Hz to 1 MHz at variant temperatures for all the test samples. HIOKI 3522-50 LCR Hi-tester device has been measured characterization of Silicon rubber/CNTs nanocomposite sensor materials, it has been used for measuring electrical parameters of nanometric sensors specimens at various frequencies. Specification of LCR is Power supply: 100 V, 120 V, 220 V or 240 V (_10%) AC (selectable), 50/60 Hz, and Frequency: DC, 1 MHz to 100 kHz, Display Screen: LCD with backlight/99999 (full 5 digits), Basic Accuracy:Z: 0:08% rdg.: 0:05, and External DC bias_40 Vmax. (option) (3522-50 used alone_10 Vmax./using 9268_40 Vmax.). It can be varied thermal conditions of the specimens with respect to high digital oven (20 °C up to 100 °C).

4. Results and Discussion

The role of matrix viscosity and type of nanotubes on the dielectric and conductivity that has been explained reinforced with SR/MWCNT nanocomposites samples. It has been observed that the shape of the nanotubes and viscosity of the matrix influenced the magnitude of dc conductivity at percolation threshold, whereas the ac conductivity keeps on increasing with increasing fill loading in all matrices.

4.1. Characterization of Traditional Silicon Rubber Samples

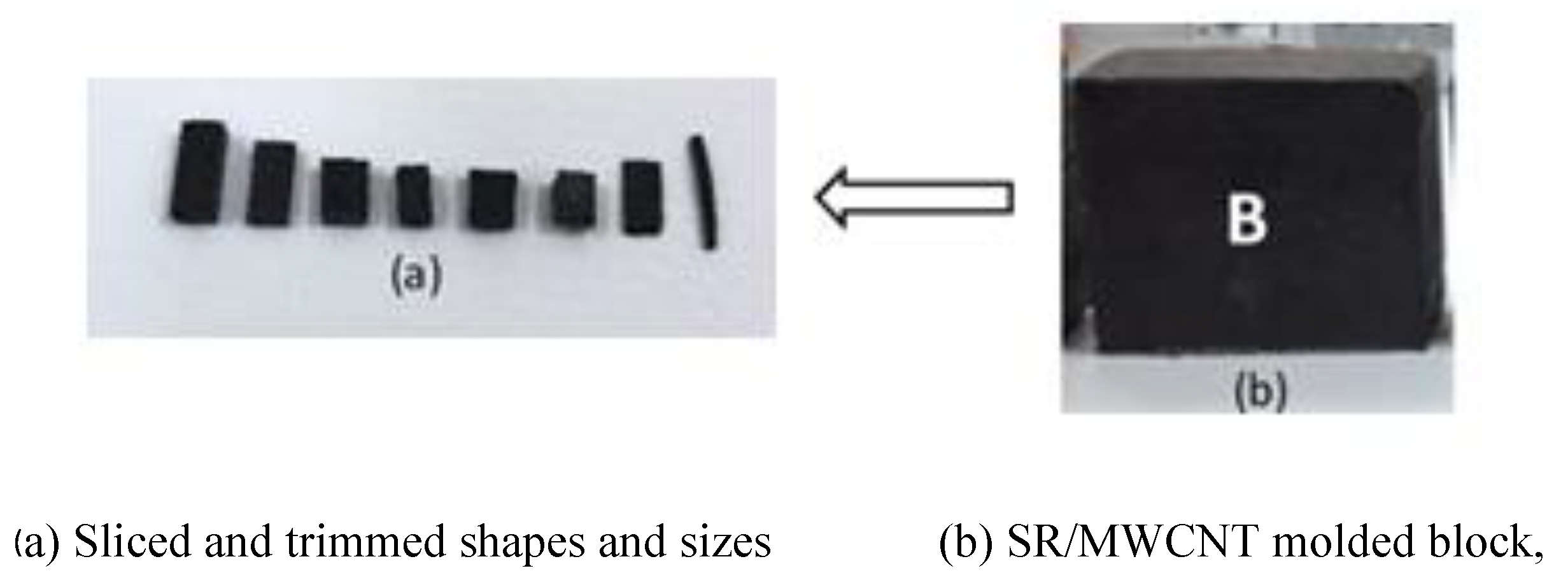

The dielectric characterization of the tested samples (virgin and compressed) is shown in

Figure 3a,b as a function of frequency for Silicon rubber at variant thermal temperatures (up to 40 °C). The measured real dielectric constant in

Figure 3a contrasts on increasing real part of dielectric constant with increasing thermal temperatures, whatever, there is a slight increasing via increasing frequency up to 10 Hz but decreasing is done via increasing frequency. Also,

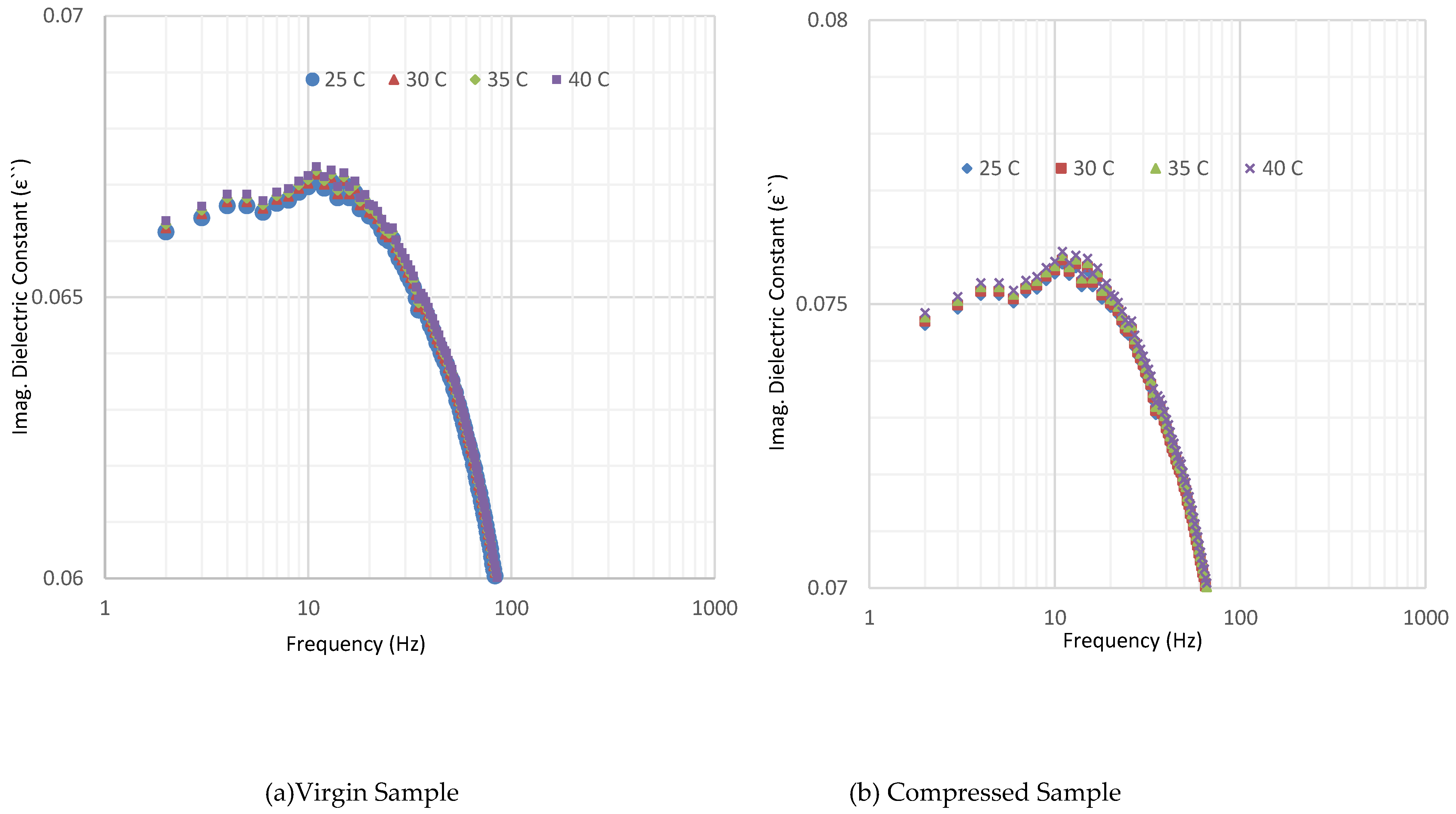

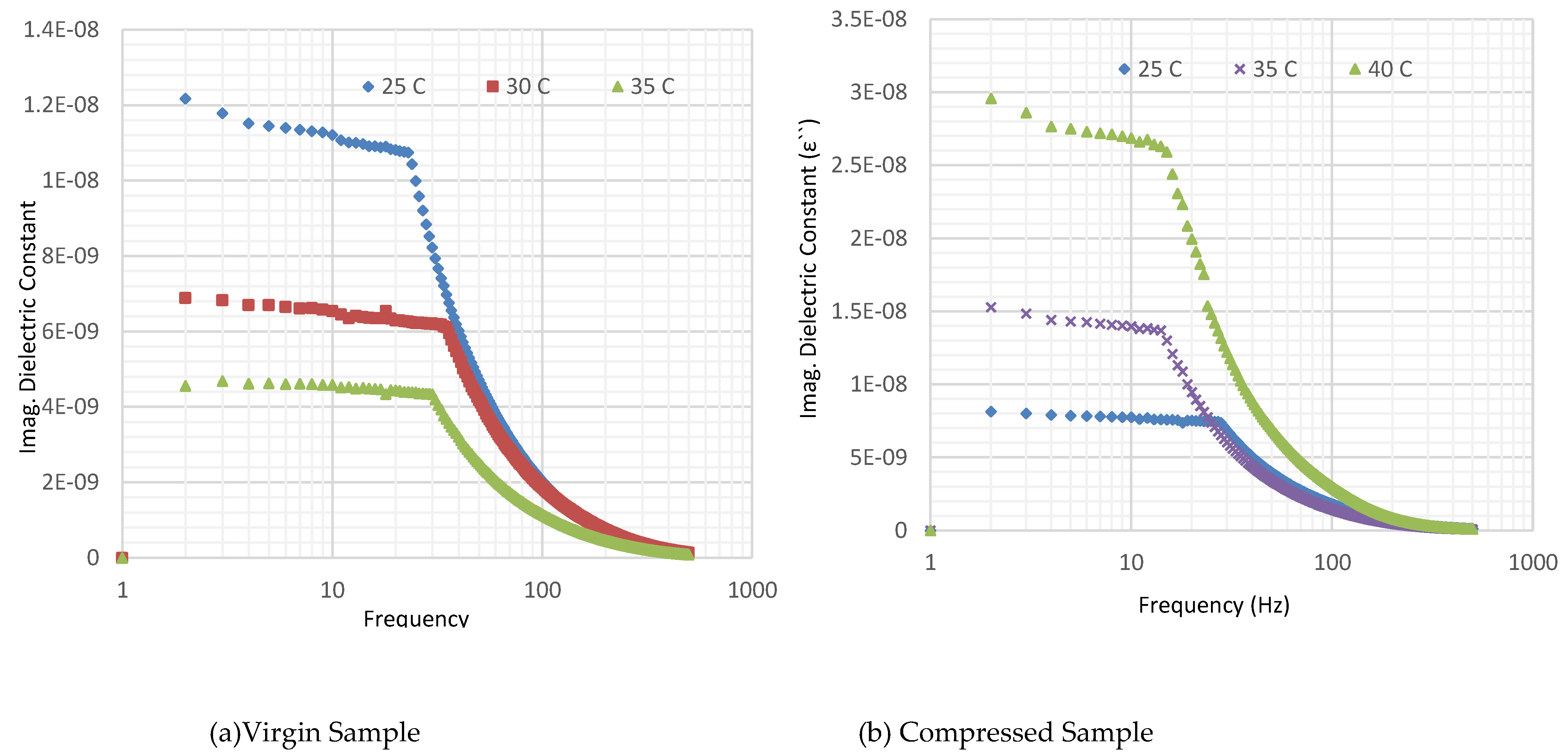

Figure 3b clarifies that a reduction of the real dielectric constant of compressed silicon rubber samples versus variant thermal temperatures (up to 40 °C) with respect to virgin samples, whatever, there is a slight increasing via increasing frequency up to 10 Hz but decreasing is done via increasing frequency. Analysis of imaginary dielectric constant characterization can be shown in

Figure 4a,b that shows the imaginary part of dielectric constant of the tested samples (virgin and compressed) as a function of frequency for Silicon rubber at variant thermal temperatures (up to 40 °C). The measured imaginary dielectric constant in

Figure 4a contrasts on a closed increasing imaginary part of dielectric constant with increasing thermal temperatures, whatever, there is a slight increasing via increasing frequency up to 10 Hz but decreasing is done via increasing frequency. Also,

Figure 4b clarifies that a closed reduction of the real dielectric constant of compressed silicon rubber samples versus variant thermal temperatures (up to 40 °C) with respect to virgin samples, whatever, but there is a slight increasing via increasing frequency up to 10Hz but decreasing is done via increasing frequency.

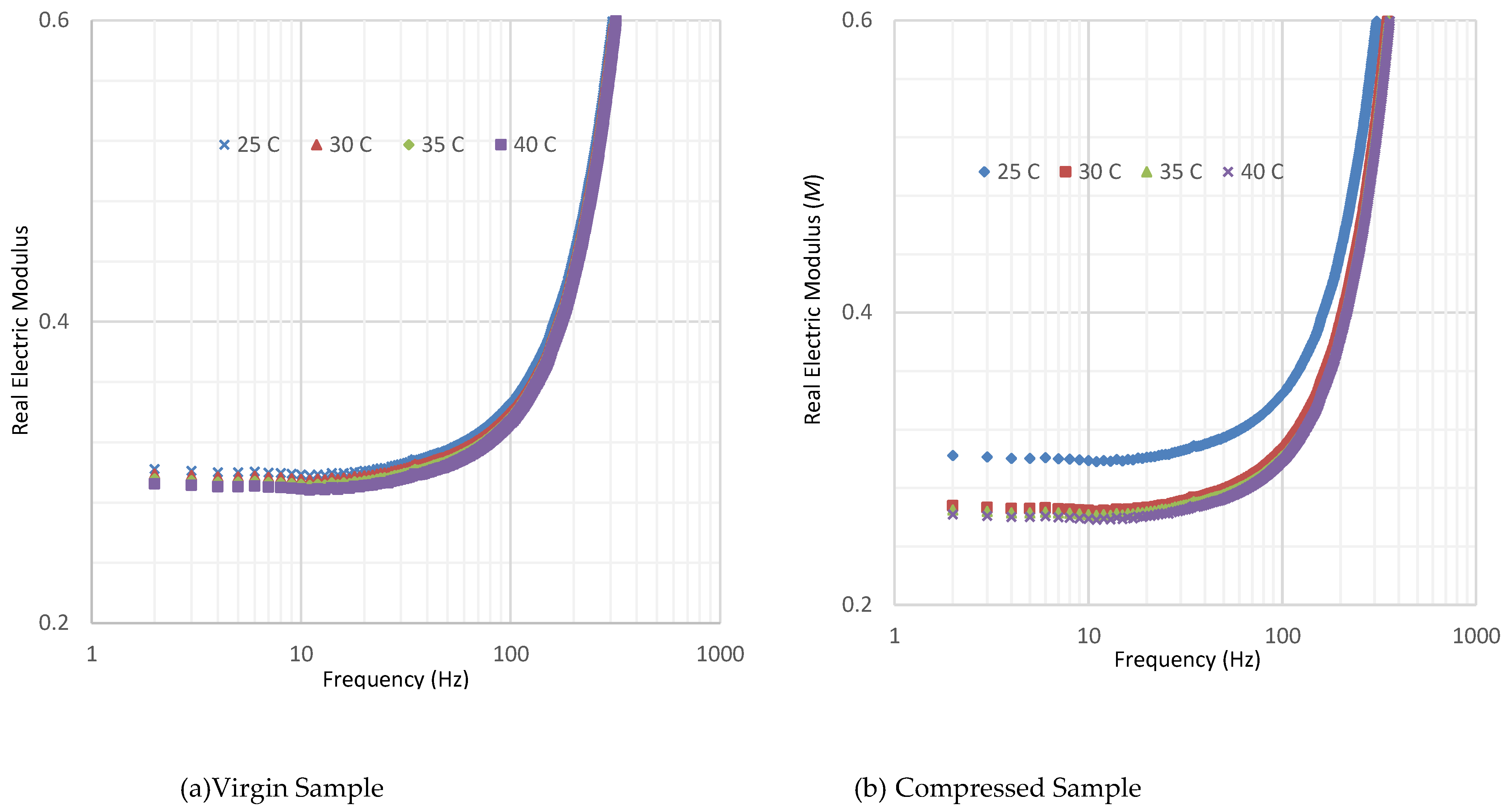

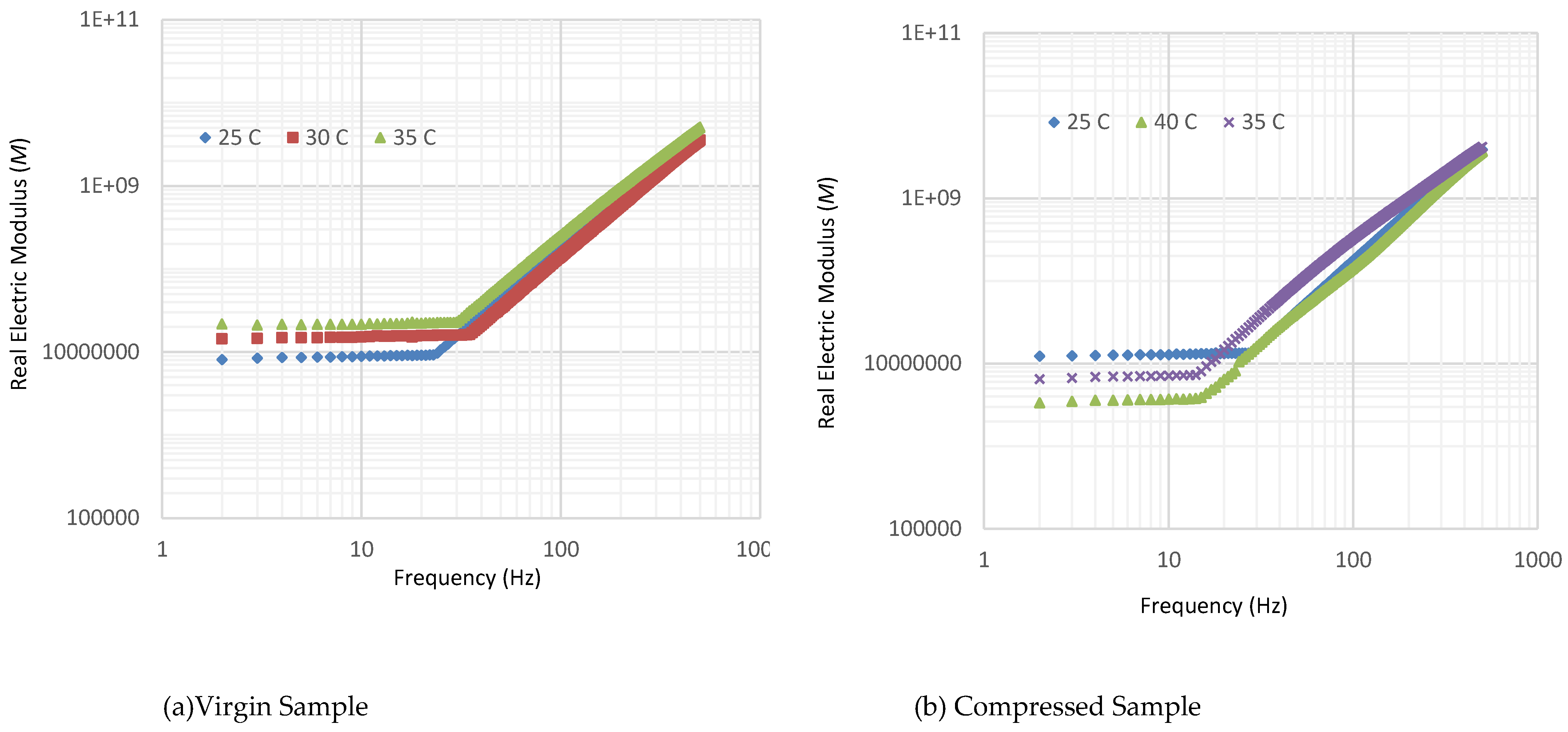

Real electric modulus characterization is shown in

Figure 5a,b for the tested samples (virgin and compressed) as a function of frequency for Silicon rubber at variant thermal temperatures (up to 40 °C). The measured real electric modulus in

Figure 5a contrasts on decreasing real electric modulus with increasing thermal temperatures; whatever, fixation real electric modulus values occur at low frequencies (up to 100 Hz) but increasing the real electric modulus happened at high frequencies (More than 100 Hz). On the other hand,

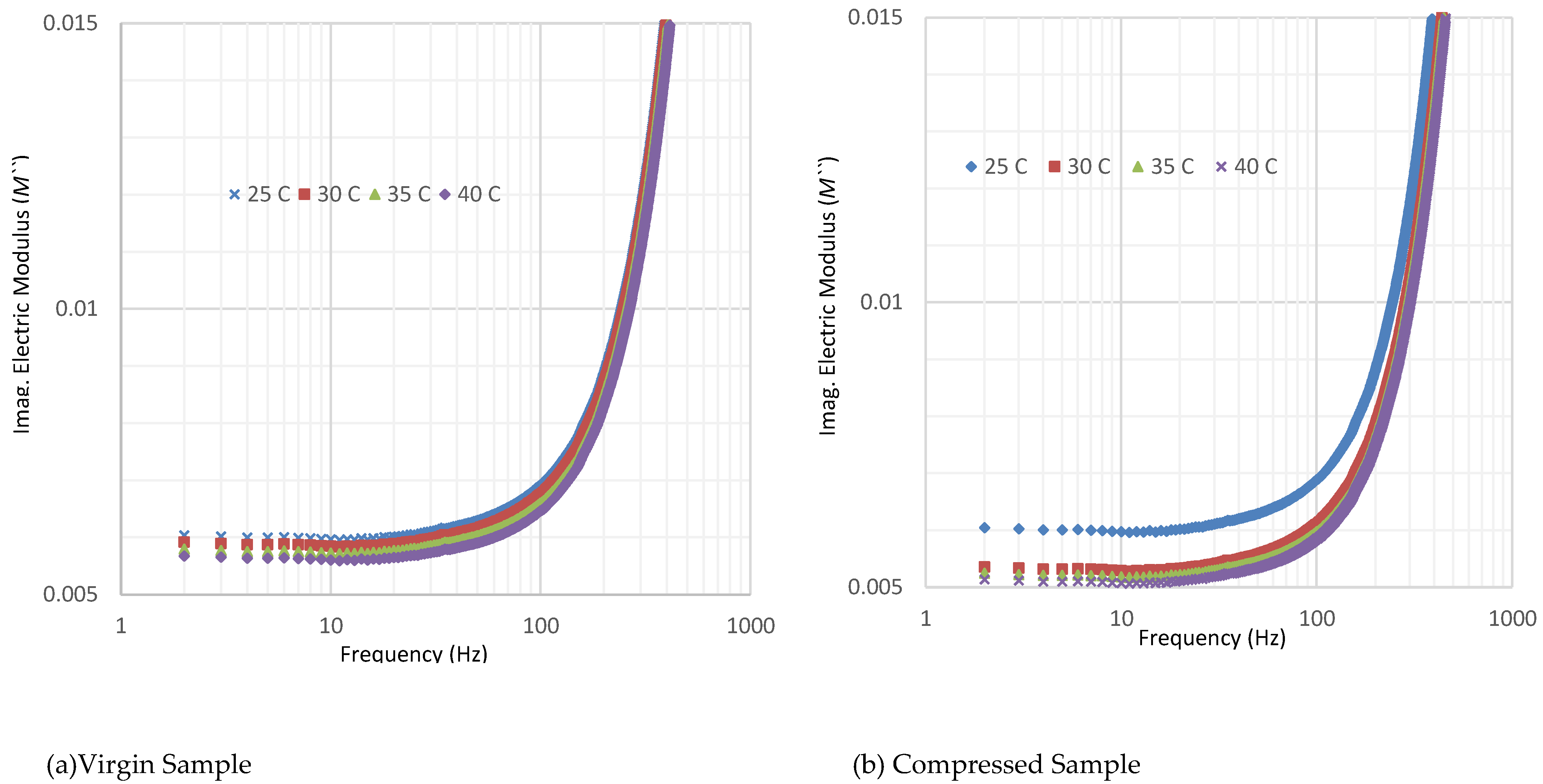

Figure 5b clarifies the decreasing in real electric modulus values for compressed silicon rubber samples with respect to the same performance of virgin samples at variant thermal temperatures (up to 40 °C) over all frequencies. On the other hand, imaginary electric modulus characterization is shown in

Figure 6a,b that clarifies the electric modulus of the tested samples (virgin and compressed) as a function of frequency for Silicon rubber at variant thermal temperatures (up to 40 °C). The measured imaginary electric modulus in

Figure 6a contrasts on decreasing imaginary electric modulus with variant thermal temperatures; whatever, a closed increasing imaginary electric modulus values occurs at low frequencies (up to 100 Hz) but the increasing the imaginary electric modulus is happened at high frequencies (More than 100 Hz). Also,

Figure 6b clarifies the decreasing in imaginary electric modulus values of compressed silicon rubber samples with respect to the same performance of virgin samples versus frequency at variant thermal temperatures (up to 40 °C).

4.2. Characterization of MWCNTs

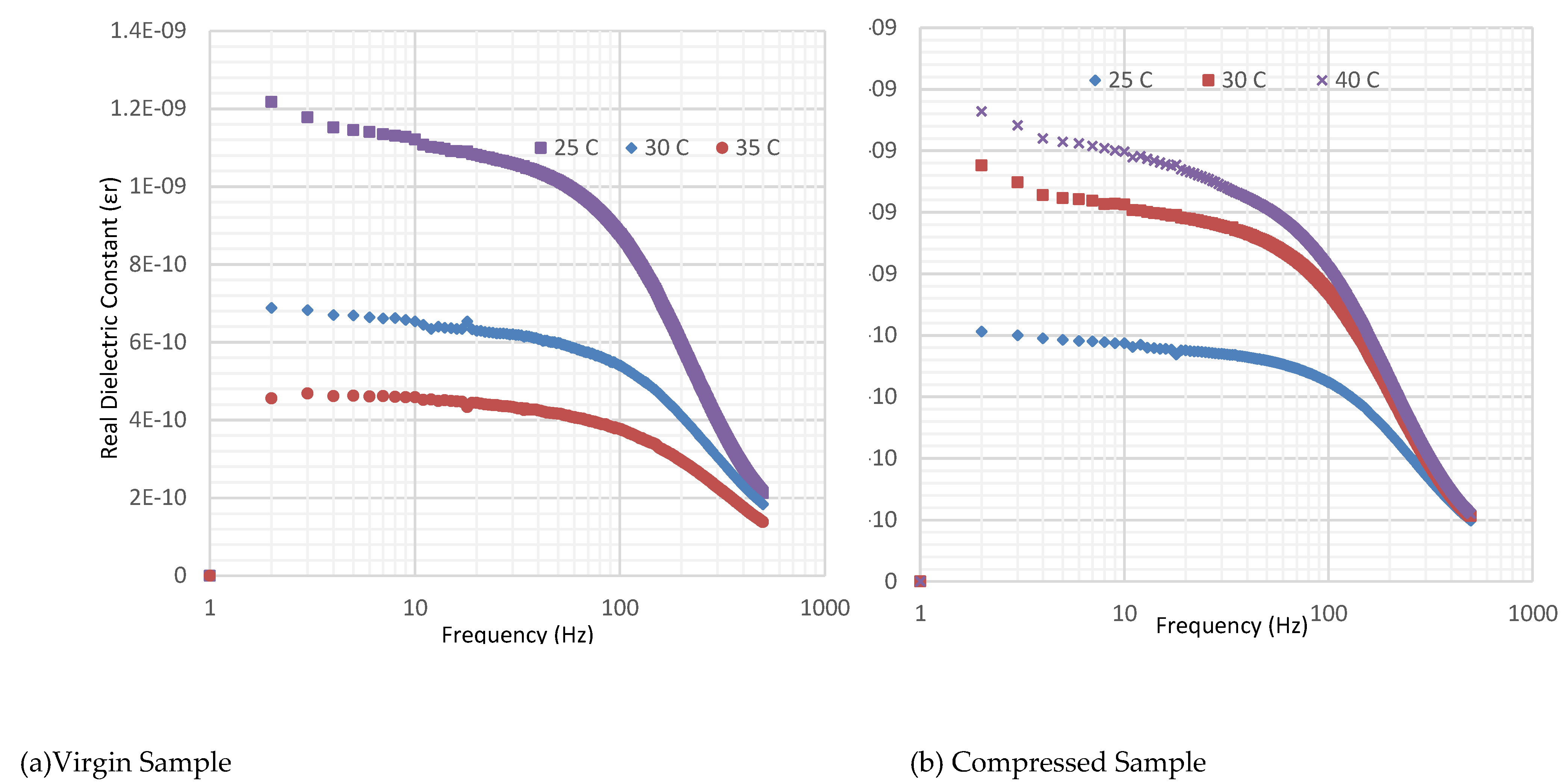

The dielectric characterization of the tested samples (virgin and compressed) is shown in

Figure 7a,b as a function of frequency for SR/MWCNT nanocomposites at variant thermal temperatures (up to 40 °C). The measured real dielectric constant in

Figure 7a contrasts on decreasing real part of dielectric constant with increasing thermal temperatures, whatever, there is decreasing via increasing frequency up to 1 kHz. Also,

Figure 7b clarifies that a reduction of the real dielectric constant of compressed SR/MWCNT nanocomposites samples versus variant thermal temperatures (up to 40 °C) with respect to virgin samples, whatever, there is decreasing the real dielectric constant via increasing frequency up to 1 kHz. Analysis of imaginary dielectric constant characterization can be shown in

Figure 8a,b that shows the imaginary part of dielectric constant of the tested samples (virgin and compressed) as a function of frequency for SR/MWCNT nanocomposites at variant thermal temperatures (up to 40 °C). The measured imaginary dielectric constant in

Figure 8a contrasts on decreasing imaginary part of dielectric constant with increasing thermal temperatures, and so, there is decreasing via increasing frequency up to 1 kHz. On the other hand,

Figure 8b clarifies that excess of the imaginary dielectric constant of compressed SR/MWCNT nanocomposites samples versus variant thermal temperatures (up to 40 °C) with respect to virgin samples, whatever, but there is decreasing via increasing frequency up to 1 kHz.

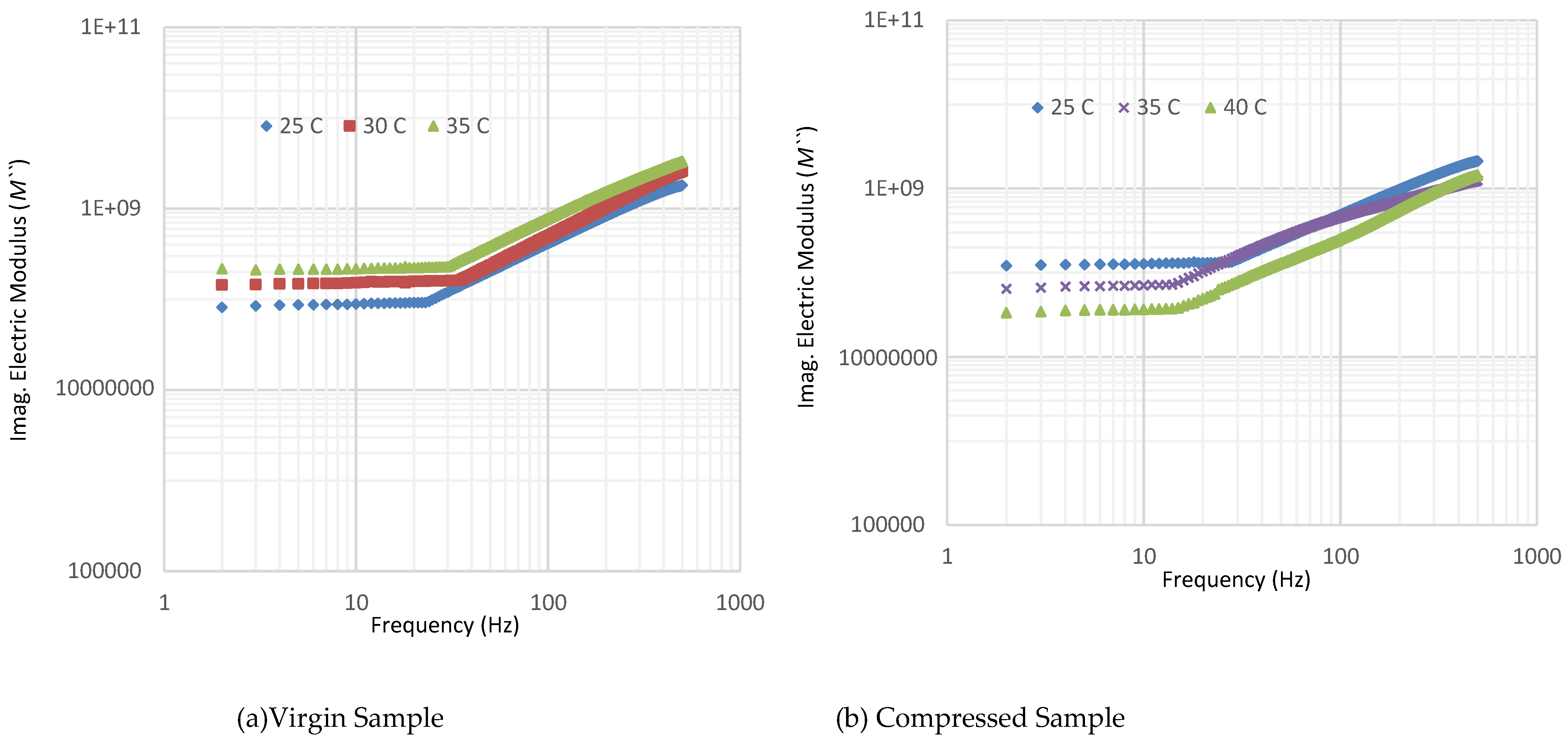

Real electric modulus characterization is shown in

Figure 9a,b that shows the real electric modulus of the tested samples (virgin and compressed) as a function of frequency for SR/MWCNT nanocomposites at variant thermal temperatures (up to 40 °C). The measured real electric modulus in

Figure 9a contrasts on increasing real electric modulus with increasing thermal temperatures; whatever, fixation real electric modulus values occur at low frequencies (up to 50 Hz) but the real electric modulus excess happened at frequencies (More than 50 Hz). On the other hand,

Figure 9b clarifies the reduction in real electric modulus values of compressed SR/MWCNT nanocomposites samples with respect to the same performance of virgin samples versus frequency at variant thermal temperatures (up to 40 °C). On the other hand, imaginary electric modulus characterization is shown in

Figure 10a,b that shows the electric modulus of the tested samples (virgin and compressed) as a function of frequency for SR/MWCNT nanocomposites at variant thermal temperatures (up to 40 °C). The measured imaginary electric modulus in

Figure 10a contrasts on increasing imaginary electric modulus with thermal temperatures; whatever, fixation imaginary electric modulus values occur at low frequencies (up to 50 Hz) but increasing the imaginary electric modulus happened at high frequencies (More than 50 Hz). On the other hand,

Figure 10b clarifies the reduction occur in imaginary impedance values of compressed SR/MWCNT nanocomposites samples with respect to the same performance of virgin samples over all measured frequencies at variant thermal temperatures except that there is a decreasing imaginary electric modulus with increasing thermal temperatures (up to 40 °C).

5. Effect of MWCNTs in Dielectric Loss

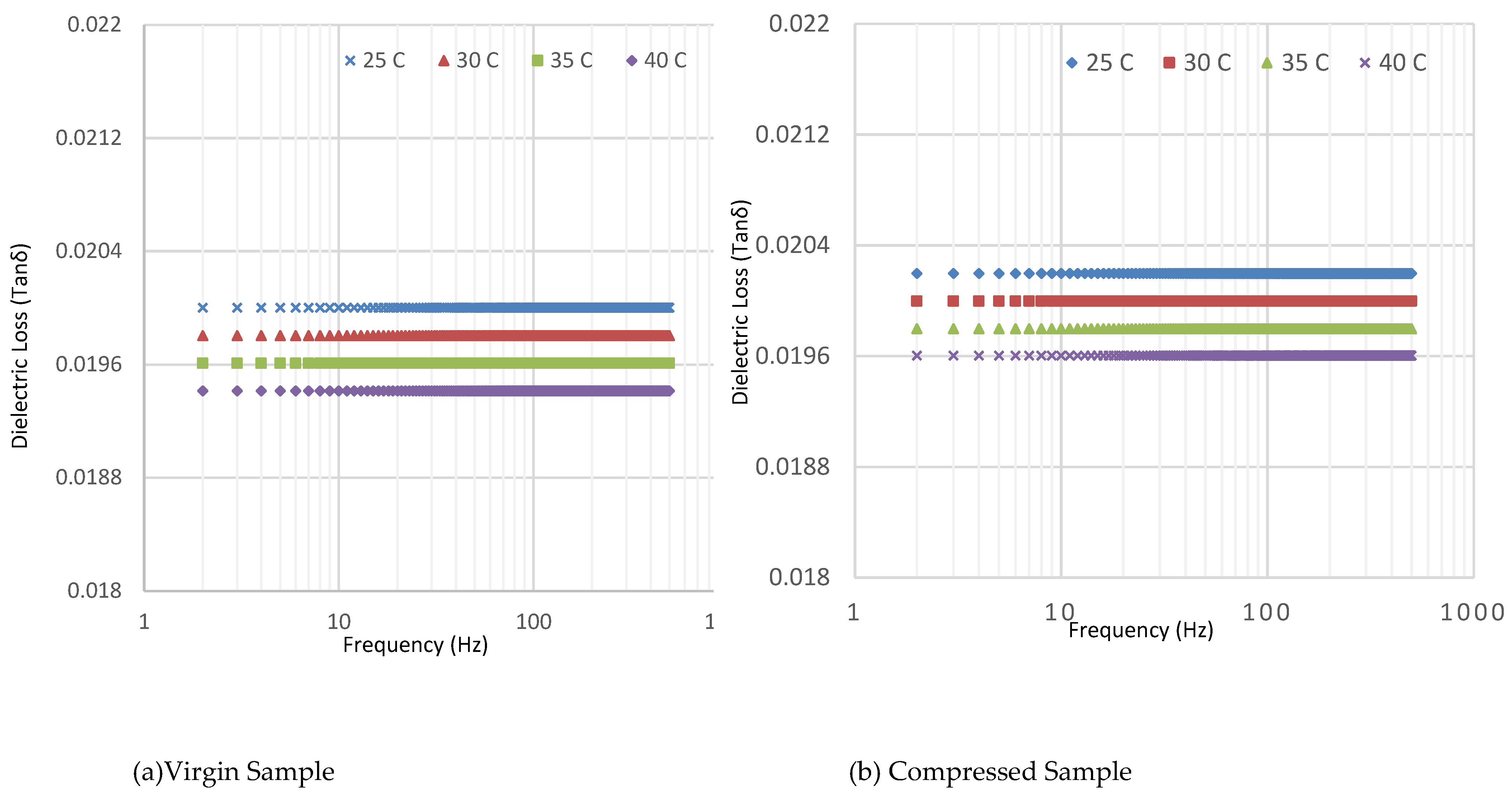

Currently, a strong demand comes from electric and dielectric industrial applications, the manufacturing for largest application market for piezoelectric devices, followed by the automotive industry. According to the dielectric loss that quantifies a dielectric material's inherent dissipation of electromagnetic energy,

Figure 11a,b has been investigated that the dielectric loss of the tested samples (virgin and compressed) as a function of frequency for silicon rubber at variant thermal temperatures (up to 40 °C). The measured dielectric loss in

Figure 11a contrasts on decreasing dielectric loss with increasing thermal temperatures; whatever, fixation dielectric loss values occur over all frequencies (up to 1 kHz). Also,

Figure 11b clarifies that a reduction of the dielectric loss of compressed silicon rubber samples versus variant thermal temperatures (up to 40 °C) with respect to virgin samples, whatever, there is fixation the dielectric loss via increasing frequency up to 1 kHz. Furthermore,

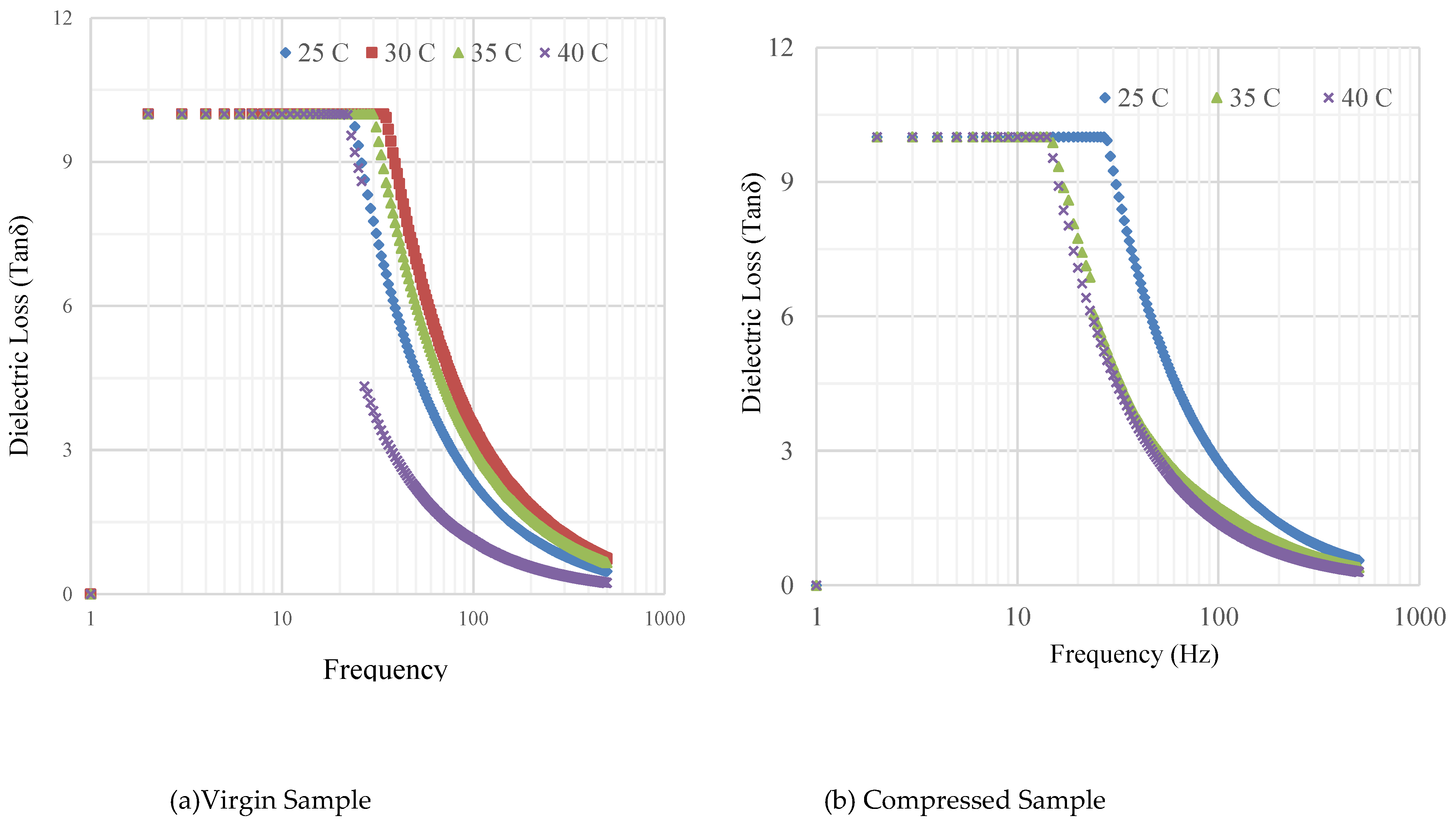

Figure 12a,b shows the dielectric loss characterization of the tested samples (virgin and compressed) as a function of frequency for SR/MWCNT nanocomposites at variant thermal temperatures (up to 40 °C). The measured dielectric loss in

Figure 12a contrasts on reduction of dielectric loss with increasing thermal temperatures; whatever, fixation dielectric loss values occur at low frequencies (up to 50 Hz) but the decreasing of dielectric loss happened at frequencies (More than 50 Hz). Whatever,

Figure 12b clarifies the reduction occur in dielectric loss values of compressed SR/MWCNT nanocomposites samples with respect to the same performance of virgin samples over all measured frequencies at variant thermal temperatures.

6. Thermal and Frequency Analysis

In case of pure silicon rubber samples, it is noticed that the measured real dielectric constant focus on increasing real part of dielectric constant with increasing thermal temperatures, whatever, there is a slight increasing via increasing frequency up to 10 Hz but decreasing is done via increasing frequency. Also, it clarifies that a reduction of the real dielectric constant of compressed silicon rubber samples versus variant thermal temperatures (up to 40 °C) and follow the same behavior with respect to virgin samples. The measured imaginary dielectric constant focus on a closed increasing imaginary part of dielectric constant with increasing thermal temperatures, whatever, there is a slight increasing via increasing frequency up to 10 Hz but decreasing is done via increasing frequency. Also, it clarifies that a closed reduction of the real dielectric constant of compressed silicon rubber samples versus variant thermal temperatures (up to 40 °C) and follow the same behavior with respect to virgin samples. The measured real electric modulus contrasts on decreasing real electric modulus with increasing thermal temperatures; whatever, fixation real electric modulus values occur at low frequencies (up to 100 Hz) but increasing the real electric modulus happened at high frequencies (More than 100 Hz). On the other hand, it clarifies the decreasing in real electric modulus values for compressed silicon rubber samples with respect to the same performance of virgin samples at variant thermal temperatures (up to 40 °C) over all frequencies. Finally, the measured imaginary electric modulus contrasts on decreasing imaginary electric modulus with variant thermal temperatures; whatever, a closed increasing imaginary electric modulus values occurs at low frequencies (up to 100 Hz) but the increasing the imaginary electric modulus is happened at high frequencies (More than 100 Hz). Also, it clarifies the decreasing in imaginary electric modulus values of compressed silicon rubber samples with respect to the same performance of virgin samples versus frequency at variant thermal temperatures (up to 40 °C).

In case of SR/MWCNT samples, it is noticed that the measured real dielectric constant focus on decreasing real part of dielectric constant with increasing thermal temperatures, whatever, there is decreasing via increasing frequency up to 1kHz. Also, it clarifies that a reduction of the real dielectric constant of compressed SR/MWCNT nanocomposites samples versus variant thermal temperatures (up to 40 °C) with respect to the same performance of virgin samples. The measured imaginary dielectric constant contrasts on decreasing imaginary part of dielectric constant with increasing thermal temperatures, and so, there is decreasing via increasing frequency up to 1 kHz. On the other hand, it clarifies that excess of the imaginary dielectric constant of compressed SR/MWCNT nanocomposites samples versus variant thermal temperatures (up to 40 °C) with respect to the same performance of virgin samples. The measured real electric modulus focusses on increasing real electric modulus with increasing thermal temperatures; whatever, fixation real impedance values occur at low frequencies (up to 50 Hz) but the real impedance excess happened at frequencies (More than 50 Hz). On the other hand, it clarifies the reduction in real electric modulus values of compressed SR/MWCNT nanocomposites samples with respect to the same performance of virgin samples versus frequency at variant thermal temperatures (up to 40 °C).The measured imaginary electric modulus contrasts on increasing imaginary electric modulus with thermal temperatures; whatever, fixation imaginary electric modulus values occur at low frequencies (up to 50 Hz) but increasing the imaginary impedance happened at high frequencies (More than 50 Hz). On the other hand, it clarifies the reduction occur in imaginary impedance values of compressed SR/MWCNT nanocomposites samples with respect to the same performance of virgin samples over all measured frequencies at variant thermal temperatures except that there is a decreasing imaginary electric modulus with increasing thermal temperatures (up to 40 °C).

7. Conclusions

This study investigates electrical characterization for conductive SR/MWCNT nanocomposites with different embedded electrical conductors. According to the adopted SR/MWCNT nanocomposites of impact, the material sensitivity depends on the rate of increase of interparticle separation with the impact force. The SR/MWCNT nanocomposites with piezoelectric property can simply be used to fabricate highly sensitive, light weight and small dimensions elastic sensors according to the desired force range.

Experimental tests deduced multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWC-NTs) are decreasing real part of dielectric constant via increasing thermal temperatures and increasing frequency up to 1 kHz. Also, it clarifies that a reduction of the real dielectric constant of compressed SR/MWCNT nanocomposites samples.

It has been deduced that multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWC-NTs) are decreasing imaginary part of dielectric constant with increasing thermal temperatures, but there is decreasing via increasing frequency up to 1 kHz. There is an excess of the imaginary dielectric constant of compressed SR/MWCNT nanocomposites samples.

Multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWC-NTs) are deduced experimentally the increasing real electric modulus with increasing thermal temperatures; whatever, a reduction in real electric modulus values of compressed SR/MWCNT nanocomposites samples occurs with respect to the same performance of virgin samples.

Experimental tests deduced multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWC-NTs) are increasing imaginary electric modulus with thermal temperatures; whatever, a reduction occur in imaginary electric modulus values of compressed SR/MWCNT nanocomposites samples with respect to the same performance of virgin samples.

Multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWC-NTs) are deduced that decreasing of dielectric loss with increasing thermal temperatures; whatever, the reduction occurs in dielectric loss values of compressed SR/MWCNT nanocomposites samples with respect to the same performance of virgin samples over all measured frequencies at variant thermal temperatures.

Acknowledgments

The present work is appreciated the fabrication and SEM observations laboratories in College of Engineering at Qassim University for functional structure preparation SR/MWCNT nanocomposites specimens and so, all greatly appreciation for Nanotechnology Research Center in Faculty of Energy Engineering at Aswan University for research cooperation in dielectric characterization and thermal measurements.

References

- Jia, Z.; Wang, Z.; Xu, C.; Liang, J.; Wei, B.; Wu, D.; Zhu, S. Study on poly(methyl methacrylate)/carbon nanotube composites. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1999, 271, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Lee, D.-J. Studies of nanocomposites based on carbon nanomaterials and RTV silicone rubber. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2017, 134, 44407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, R.; Weisenberger, M.C. Carbon nanotube polymer composites. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2004, 8, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saleh, M.H.; Sundararaj, U. Electromagnetic interference shielding mechanisms of CNT/polymer composites. Carbon 2009, 47, 1738–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Lee, G.; Choi, J.; Lee, D.J. Studies on composites based on HTV and RTV silicone rubber and carbon nanotubes for sensors and actuators. Polymer 2020, 190, 122221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; He, X.; Liu, X.; Leng, F.; Mai, Y. The effective properties and local aggregation effect of CNT/SMP composites. Compos. B Eng. 2012, 43, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, B.; Anthony, C.; Arnaud, A.; Lionel, F. CNT aggregation mechanisms probed by electrical and dielectric measurements. J. Mater. Chem. C 2015, 3, 5769–5774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Lee, J.-Y.; Lee, D.-J. Synergistic effects of hybrid carbon nanomaterials in room-temperature-vulcanized silicone rubber. Polym. Int. 2017, 66, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, N.; Tang, Y.; Ye, L.; Fang, L. Silicone rubber nanocomposites containing a small amount of hybrid fillers with enhanced electrical sensitivity. Mater. Des. 2013, 45, 548–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Lee, D.-J. Effects of purity in single-wall carbon nanotubes into rubber nanocomposites. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2019, 715, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Lin, Y.H.; Nan, C.W. Interfacial effect on dielectric properties of polymer nanocomposites filled with core/shell-structured particles. Adv Funct Mater 2007, 17, 2405–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallone, G.; Carpi, F.; Rossi, D.D.; et al. Dielectric constant enhancement in a silicone elastomer filled with lead magnesium niobate-lead titanate. Mater Sci Eng C 2007, 27, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kussmaul, B.; Risse, S.; Kofod, G.; et al. Enhancement of dielectric permittivity and electromechanical response in silicone elastomers: molecular grafting of organic dipoles to the macromolecular network. Adv Funct Mater 2011, 21, 4589–4594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannsfeld, S.C.B.; Benjamin, C.K.T.; Randall, M.S.; et al. Highly sensitive flexible pressure sensors with microstructured rubber dielectric layers. Nature Mater 2010, 9, 859–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, D.J.; Mitra, D.; Peterson, K.; et al. A highly elastic, capacitive strain gauge based on percolating nanotube networks. Nano Lett 2012, 12, 1821–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Huang, Y.; Zheng, S.; Liu, Z.; Yang, M. Improved dielectric properties of polymer-based composites with carboxylic functionalized multiwalled carbon nanotubes. Journal of Thermoplastic Composite Materials 2018, 32, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dil, E.J.; Arjmand, M.; Navas, I.O.; Sundararaj, U.; Favis, B.D. Interface bridging of multiwalled carbon nanotubes in polylactic acid/poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate): morphology, rheology, and electrical conductivity. Macromolecules 2020, 53, 10267–10277. [Google Scholar]

- Navas, I.O.; Arjmand, M.; Sundararaj, U. Effect of carbon nanotubes on morphology evolution of polypropylene/polystyrene blends: understanding molecular interactions and carbon nanotube migration mechanisms. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 54222–54234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas, I.O.; Kamkar, M.; Arjmand, M.; Sundararaj, U. Morphology evolution, molecular simulation, electrical properties, and rheology of carbon nanotube/polypropylene/polystyrene blend nanocomposites: effect of molecular interaction between styrene-butadiene block copolymer and carbon nanotube. Polymers 2021, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Otero-Navas, I.; Arjmand, M.; Sundararaj, U. Carbon nanotube induced double percolation in polymer blends: morphology, rheology and broadband dielectric properties. Polymer 2017, 114, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas, I.O.; Arjmand, M.; Sundararaj, U. Effect of carbon nanotubes on morphology evolution of polypropylene/polystyrene blends: understanding molecular interactions and carbon nanotube migration mechanisms. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 54222–54234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Tian, Y.; Xu, P.; Wei, H.; Li, Y.; Peng, H.-X.; Qin, F. Effect of the selective localization of carbon nanotubes and phase domain in immiscible blends on tunable microwave dielectric properties. Composites Science and Technology 2021, 213, 108919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, G.; Hu, N.; Karube, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Fukunaga, H.; et al. A carbon nanotube/polymer strain sensor with linear and anti-symmetric piezo resistivity. Mech. Compos. Mater. Struct. 2011, 45, 1315–1323. [Google Scholar]

- Potschke, P.; Bhattacharyya, A.R.; Janke, A.; Pege, S.; Leonhardt, A.; Taschner, C.; et al. Melt mixing as method to disperse carbon Nanotubes intothermoplastic polymers. Fuller. Nanotub. Car. N. 2005, 13, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherif, H.A.; Almufadi, F.A. Fabrication and characterization of silicone rubber/multiwalled carbon nanotubes nanocomposite sensors under impact force. Sensors and Actuators A 2019, 297, 111479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Jiang, B.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y. Influence of wall number and surface functionalization of carbon nanotubes on their antioxidant behavior in high density polyethylene. Carbon 2012, 50, 1005–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamane, S.; Ata, S.; Chen, L.; Sato, H.; Yamada, T.; Hata, K.; Mizukado, J. Experimental analysis of stabilizing effects of carbon nanotubes (CNTs) on thermal oxidation of poly(ethylene glycol)-CNT composites. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2017, 670, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ata, S.; Hayashi, Y.; Nguyen Thi, T.B.; Tomonoh, S.; Kawauchi, S.; Yamada, T.; Hata, K. Improving thermal durability and mechanical properties of poly(ether ether ketone) with single-walled carbon nanotubes. Polymer 2019, 176, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thabet, A.; Salem, N. Experimental verification on dielectric breakdown strength using individual and multiple nanoparticles in polyvinyl chloride. Transactions on Electrical and Electronic Materials Journal 2020, 21, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.T. Design and Investment of High Voltage NanoDielectrics. IGI Global, Publisher of Timely Knowledge; ISBN13: 9781799838296, ISBN10: 1799838293, EISBN13: 9781799838302; August 2020; Pages 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thabet, A.; Salem, N. Experimental Investigation on Dielectric Losses and Electric Field Distribution inside Nanocomposites Insulation of Three-Core Belted Power Cables. Advanced Industrial and Engineering Polymer Research 2021, 4, 1857–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thabet, A.; Fouad, M. Assessment of Dielectric Strength and Partial Discharges Patterns in Nanocomposites Insulation of Single-Core Power Cables. Journal of Advanced Dielectrics (JAD) 2021, 11, 2150022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.T. Emerging Nanotechnology Applications in Electrical Engineering. IGI Global, Publisher of Timely Knowledge; ISBN13: 9781799885368, ISBN10: 1799885364, EISBN13: 9781799885382, ISBN13 Softcover: 9781799885375; June 2021; Pages 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).