1. Introduction

The migration of immune cells is a key step and major feature in the inflammatory response [

1]. Specifically, macrophage migration is a vital process in host defense and homeostasis maintenance [

2,

3]. Abnormal macrophage migration leads to cytokine accumulation, tissue destruction and tumor formation, and is a key factor in the development and progression of many autoimmune diseases, inflammatory diseases and cancers [

4,

5]. Therefore, macrophage migration is considered one of potential targets for therapeutic strategies of these diseases.

The DUSP2 protein regulates activation of members in the MAPK family [

6,

7]. MAPK family mainly includes extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), c-Jun amino-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38, and mediates the transduction pathway of inflammation induction [8-11]. Previous research demonstrated that DUSP2-deficient macrophages exhibited increased activation of JNK, decreased activation of p38 and ERK and reduced expression of inflammatory mediators, suggesting a positive role of DUSP2 in regulating innate immune function through the MAPK [

12]. However, DUSP2 adversely affected the differentiation of TH17 cells and the anti-tumor effect of T cells [

13,

14], suggesting a negative involvement of DUSP2 in adaptive immunity. Thus, DUSP2 is an important factor for the immune function of the organism.

Deletion of DUSP2 inhibited the expression of inflammatory mediators in macrophages, but it remained to be clarified whether DUSP2 affected macrophage migration and if it did, how [

12]. This study aimed to answer the question by using the macrophage reporter line Tg(mpeg1:mCherry)and the

dusp2-/- mutant previously generated in our lab [

15,

16].

There was a clear temporal separation between innate and adaptive immunity in zebrafish [

17,

18]. Furthermore, transparency in early developmental stages of zebrafish allowed visual manipulation and observation, and transgenic zebrafish lines that specifically label immune cells facilitate analysis of discrete immune events [

15,

19]. Taking these advantages, we investigated the effect of DUSP2 on macrophage migration and potential mechanisms in zebrafish larvae with tail fin injury model.

2. Materials and Methods

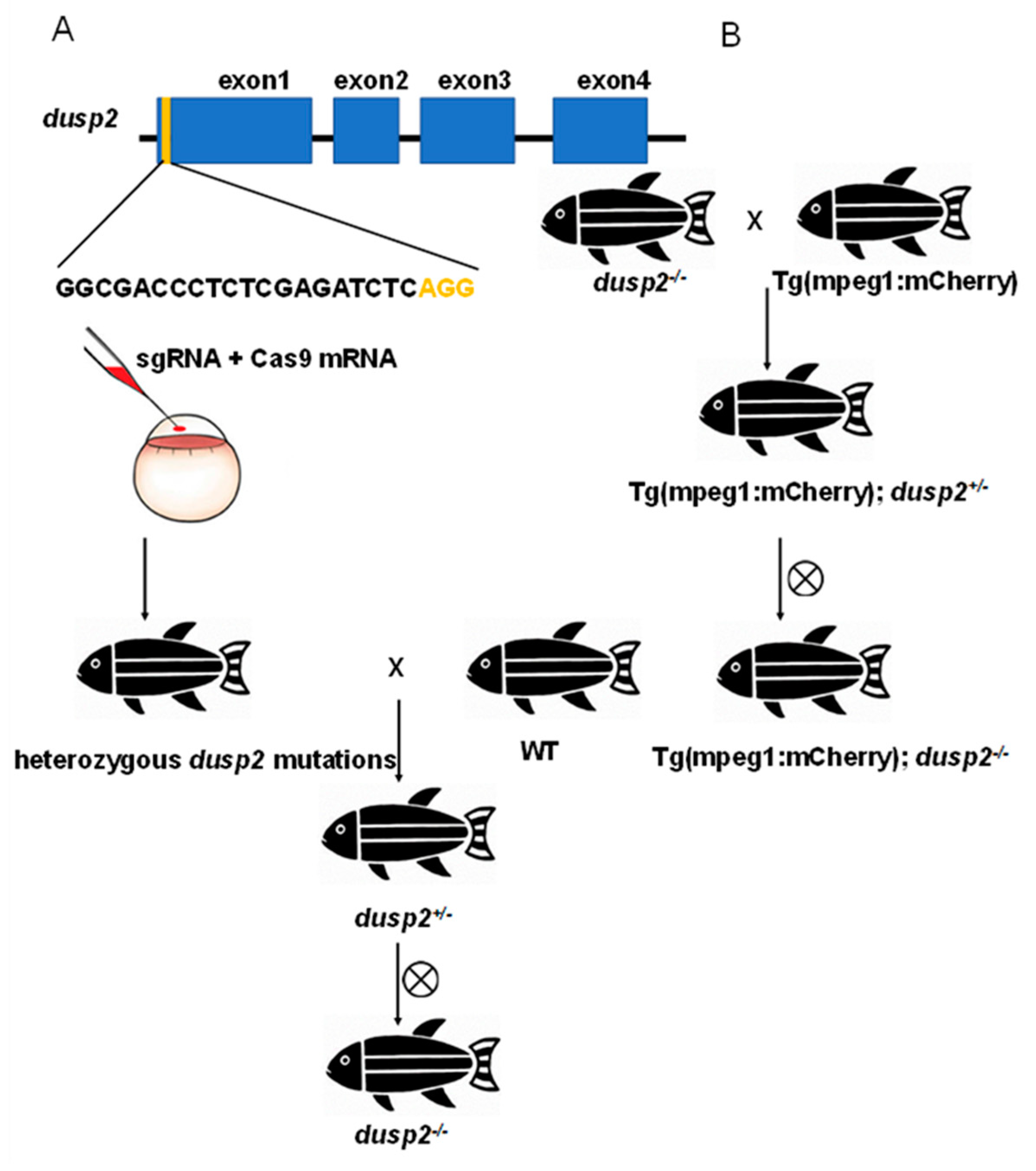

2.1. Zebrafish Lines

The zebrafish lines used in this experiment included Wild-type (WT) zebrafish,

dusp2-/- mutant zebrafish, transgenic zebrafish Tg (mpeg1:mCherry) and Tg(mpeg1:mCherry);

dusp2-/-. The

dusp2-/- mutant zebrafish was previously obtained by knocking out the

dusp2 gene by CRISPR/Cas9 [

16]. The

dusp2-/- mutant zebrafish was crossed with Tg(mpeg1:mCherry) to obtain the F

1 generation, and the Tg(mpeg1:mCherry);

dusp2-/- was identified after incross among F

1 littermates (

Figure 1). All animal experimental protocols were approved by the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC) Animal Resources Center and University Animal Care and Use Committee and the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments of the USTC (Permit Number: USTCACUC1103013).

2.2. Tail Fin Injury

The experimental model used in this study was a tail fin injury model. The slide and sterile scalpel were sterilized with 75% ethanol prior to tail fin injury. The zebrafish larvae at 4 dpf were then anesthetized with MS-222 (Sigma, E10505) and placed on the slide, and the tail fin was cut from the end of the spinal cord with a sterile scalpel under a stereomicroscope (Olympus SZX-16, Japan).

2.3. In Vivo Imaging

In the absence of tail fin injury, macrophages in the 800 μm region from the end of the spinal cord forward were imaged at 10× using a laser confocal microscope (Olympus FV1000, Japan), and macrophages in this area were enumerated, giving the total number of macrophages in the sample. At different time points after tail fin injury, macrophages in the 250 μm region from the end of the spinal cord forward were imaged at 10× using a fluorescence microscope (Olympus BX60, Japan), and similarly, macrophages in this region were counted, giving the number of macrophages that migrated to the injury site. For the analysis of macrophage motility velocity, a laser confocal microscope (Olympus FV1000, Japan) was used to image continuously for 30 min at 10x, scanning 1 z-stack every 1 min. The imaging time points were before tail fin injury and 2.5 hpi - 3 hpi for each group of 8 zebrafish larvae. The data obtained were analyzed for macrophage motility using the software ImageJ and only those macrophages that migrated towards the injury site were counted.

2.4. Drug Treatment

To investigate the effect of ERK protein on macrophage migration, we used an ERK inhibitor, PD0325901 (MCE, HY-10254) to inhibit phosphorylation of ERK protein [

20]. The working liquid concentration of PD0325901 was 20 μM, and the control group was treated with DMSO. Zebrafish larvae were treated with PD0325901 or DMSO three hours before tail fin injury. Zebrafish larvae continued to be treated with either inhibitor or DMSO after tail fin injury.

2.5. Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted using TRIZOL reagent (Takara) without tail fin injury or 1 hour after tail fin injury. The expression levels of

dusp2, inflammatory cytokines and chemokines were evaluated by qPCR and the SYBR Green kit (Vazyme,China). The samples were obtained from three independent experiments, each with three replicates, and were subjected to a standard protocol (pre-denaturation at 95 °C for 5 minutes, followed by 44 cycles of 95 °C for 15 seconds and 60 °C for 30 seconds, and finally 95° C for 15 seconds, 60 ° C for 60 seconds, and 95 °C for 15 seconds). Relative mRNA expression levels were obtained by standardizing to β-actin mRNA level using the 2

–ΔΔCt method.

Table 1 showed the specific primers used in PCR.

2.6. Western Blot

The zebrafish larvae were lysed with RIPA (Sangon, Shanghai, China) without tail fin injury or 1 hour after tail fin injury. The primary antibody of p-ERK (CST, 4370T,1:1000) from rabbits was incubated overnight at 4°C.The primary antibody of ERK (CST, 4695T, 1:1000) from rabbits and primary antibody of β-actin (HuaBio, Hangzhou, China, ET1701-80, 1:1000) from rabbits were incubated for 3 h at 37°C. The HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (Proteintech, SA00001-2, Chicago, IL, USA, 1:5000) was incubated for 1 h at 37°C. We used ImageJ (NIH, USA) software to calculate the gray value of the strip.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data were carried out with Student’s t-test using GraphPad Prism 8.0 (USA). One-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) were used as indicated in the results. All date were presented as mean ± SEM. p < 0.05 was supposed to be a significant difference.

3. Results

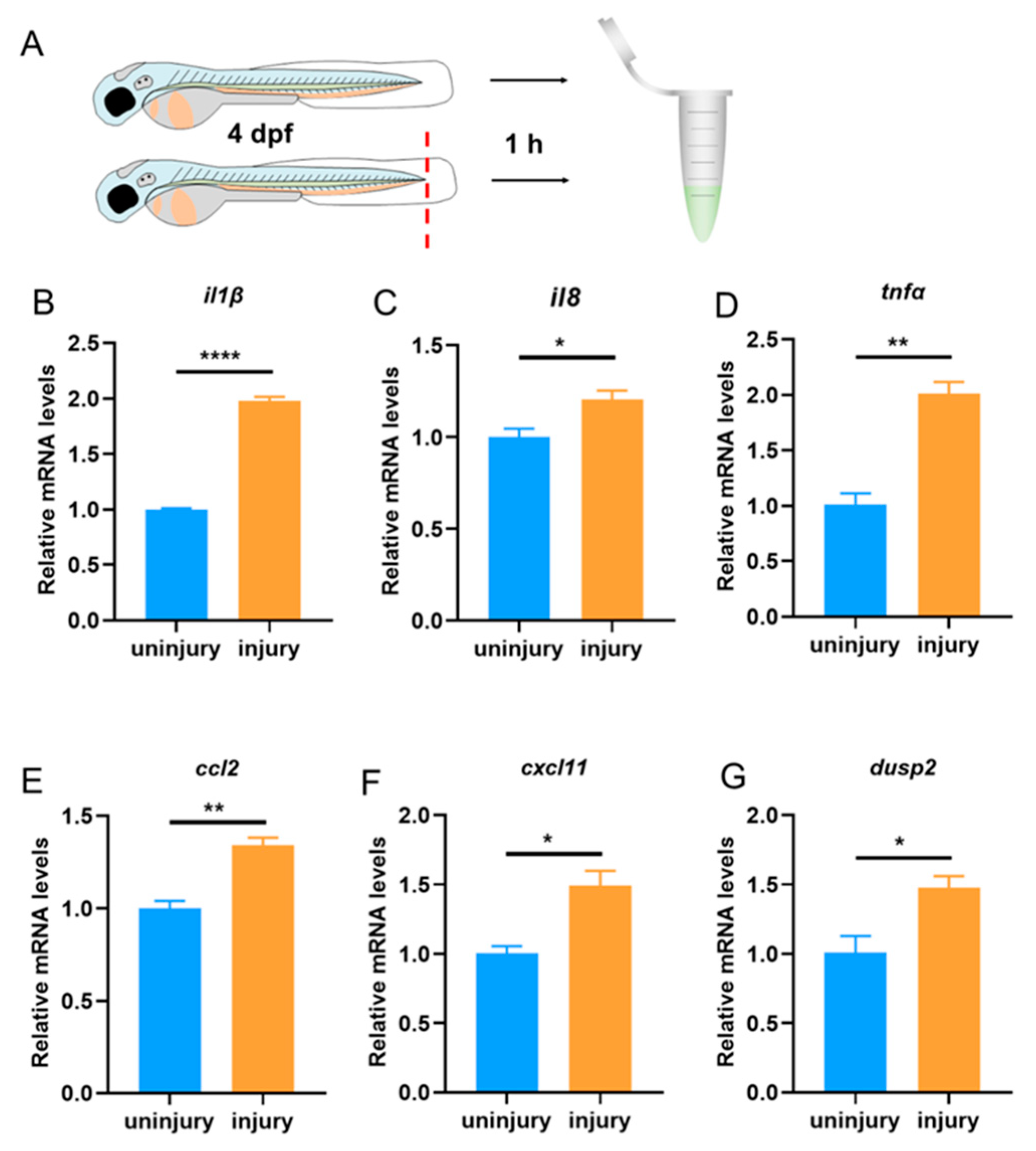

3.1. The Expression of dusp2 was Significantly Up-Regulated in Acute Inflammation Induced by Tail Fin Injury

First, we used a tail fin injury model to investigate whether DUSP2 is involved in acute inflammation induced by tail fin injury in zebrafish larvae (

Figure 2A). Expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines was up-regulated and neutrophils and macrophages were recruited to the injury site after tail fin injury [

21]. One hour after tail fin injury, qPCR results showed that the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-8, and TNF-α were significantly increased (

Figure 2B,C,D). Meanwhile, the expression of chemokines CCL2 and CXCL11 were also significantly up-regulated (

Figure 2E,F). These results suggested that the tail fin injury model successfully induced acute inflammation in zebrafish larvae. Furthermore, we found that the expression of

dusp2 was significantly up-regulated (

Figure 2G), indicating that DUSP2 might be involved in acute inflammation induced by tail fin injury in zebrafish larvae.

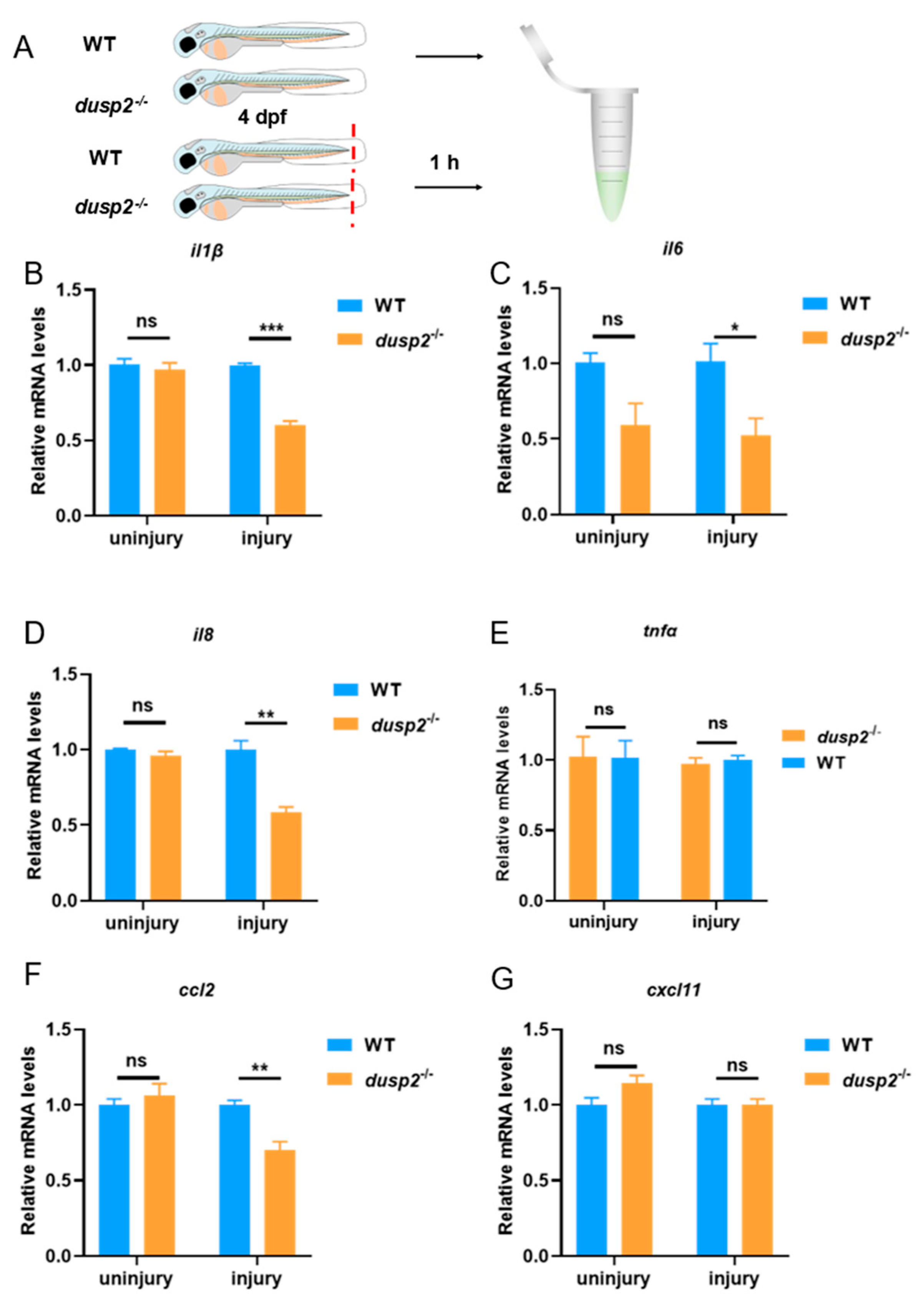

3.2. DUSP2 Deletion Significantly Decreased the Expression of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines and Chemokines after Tail Fin Injury

Next, we aimed to explore whether the deletion of DUSP2 affects the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in zebrafish larvae. Here, we mainly examined the expression of four pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α) and two macrophage chemokines (CCL2, CXCL11) in WT and

dusp2-/- zebrafish larvae before and after tail fin injury. The results of qPCR showed that the deletion of DUSP2 did not affect the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8,TNF-α and macrophage chemokines CCL2 and CXCL11 in the absence of tail fin injury (

Figure 3B–G). However, the deletion of DUSP2 suppressed the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and macrophage chemokine CCL2 after tail fin injury (

Figure 3B–D,F), and did not affect the expression of TNF-α and CXCL11 (

Figure 3E,G). These results suggested that DUSP2 was involved in acute inflammation induced by tail fin injury in zebrafish larvae and might be involved in the migration of macrophage.

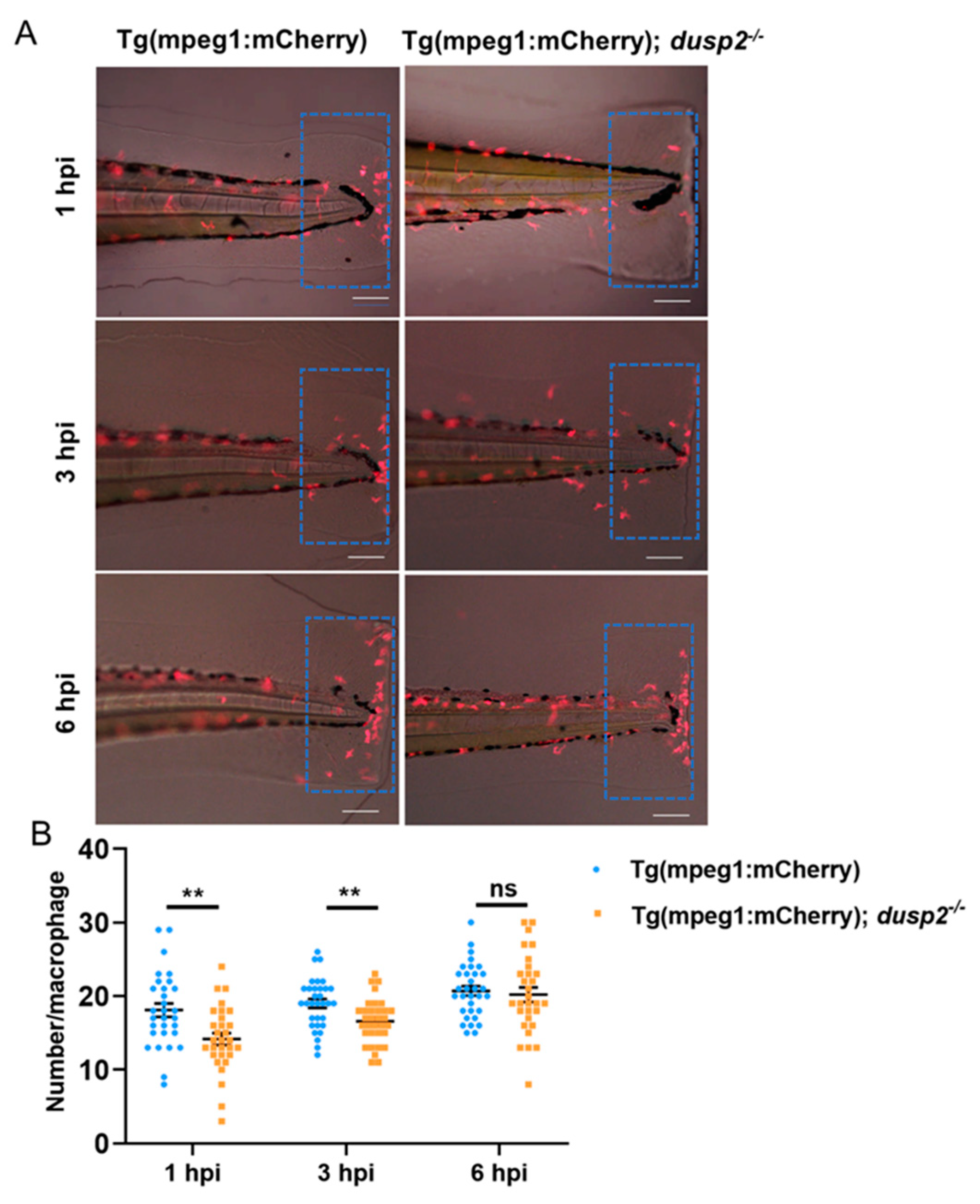

3.3. DUSP2 Deletion Inhibited Migration of Macrophages to the Injury

To investigate whether the deletion of DUSP2 affects the migration of macrophages, we used a fluorescent microscope to image and enumerated the macrophages at the injury site at 1, 3, and 6 hours after tail fin injury. The results showed that the deletion of DUSP2 inhibited the migration of macrophages to the injury site at 1 and 3, but not 6 h after tail fin injury (

Figure 4). Therefore, DUSP2 seems to only influence the early recruitment of macrophages.

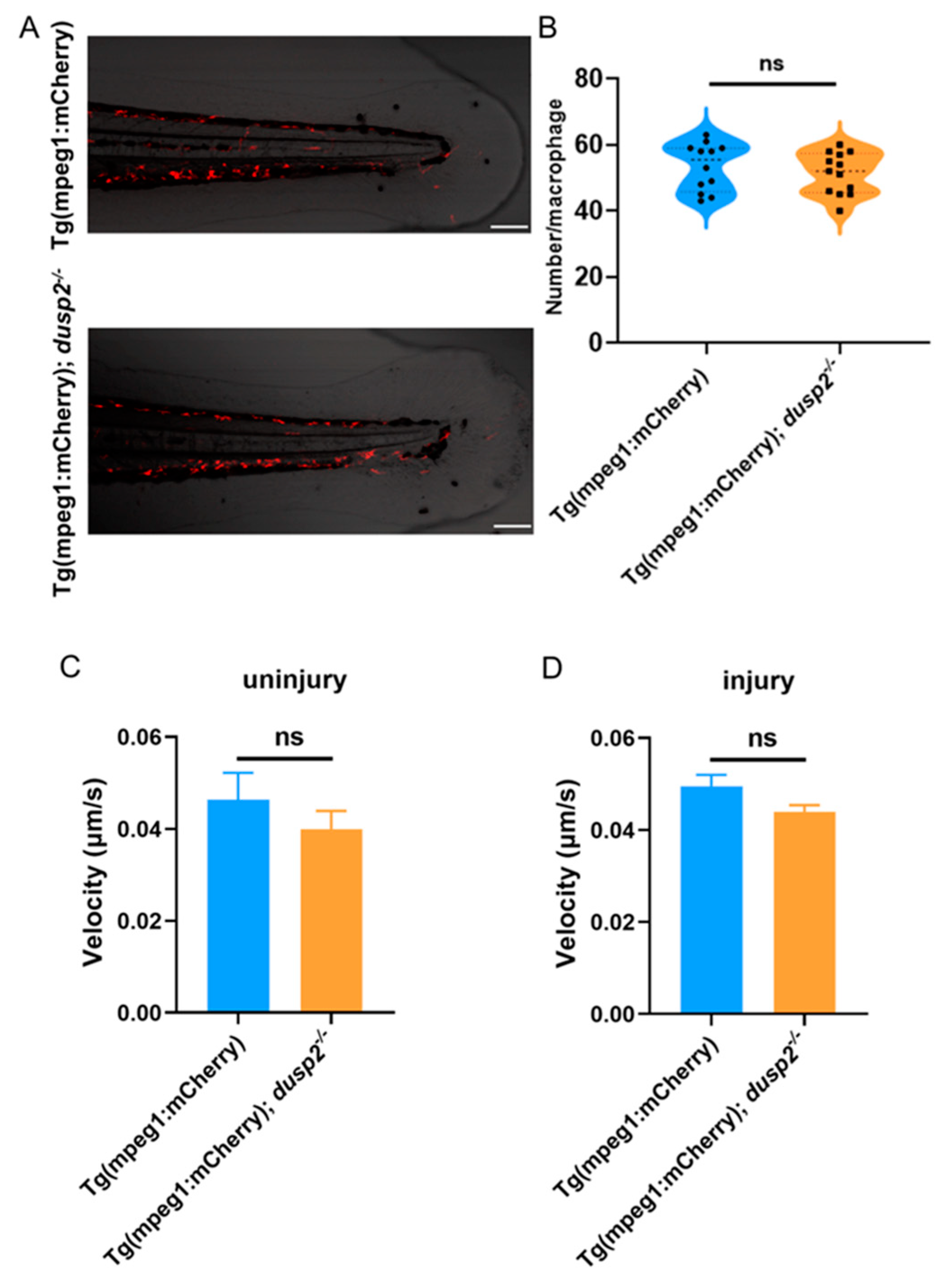

Next, we asked why DUSP2 knockout (KO) decreased the number of migrating macrophages at 1 and 3 h after injury. First, we checked if DUSP2 KO reduced the total number of macrophages in zebrafish larvae. Based on an established approach in our lab, the number of macrophages within 800 μm from the end of the spinal cord forward was used to characterize the total number of macrophages in zebrafish larvae [

22]. The results showed that there was no significant difference in the total number of macrophages between the mutant and control (

Figure 5A,B), indicating that the total number of macrophages was not the reason that caused fewer migrating macrophages after injury.

The second candidate that came to our attention is the motility rate of macrophages. After tail fin injury, neutrophils and macrophages migrated to the injury site at different velocity [

23]. We assessed the effect of DUSP2 on motility velocity of macrophage by real-time analysis. Results showed that DUSP2 KO had no significant effect on the motility of macrophages either at uninjured (

Figure 5C) or 2.5-3 h post injury (

Figure 5D). Hence the decreased number of migrating macrophages in DUSP2 KO larvae was not due to a decreased migrating rate.

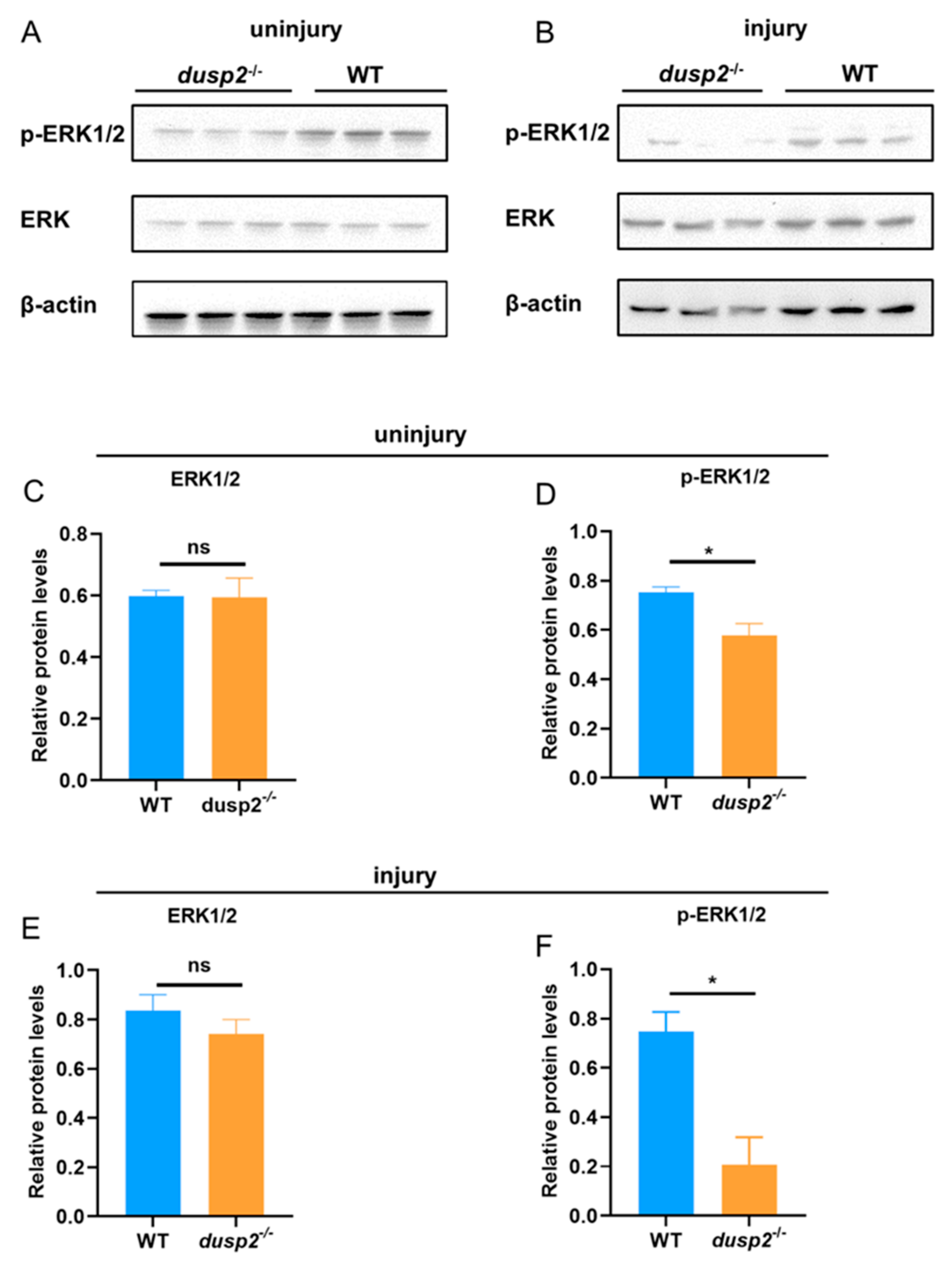

3.4. DUSP2 Deletion Inhibited ERK Protein Phosphorylation

After precluding the possible contributions of macrophage pool and motility, we hypothesized that DUSP2 KO may downregulate some signaling pathways that promote, and/or upregulate some that inhibit, macrophage migration. Based on a previous study that activation of ERK was decreased in DUSP2 deficient immune cells [

12], we speculated that the deletion of DUSP2 might reduce macrophage migration via ERK in zebrafish larvae. Western blotting results showed that even without injury, the phosphorylation level of ERK was significantly lower in DUSP2 KO than control (

Figure 6A,D), while the protein level of ERK was not significantly different (

Figure 6A,C). And it’s the same case after tail fin injury (

Figure 6B,E,F). These results suggested that the deletion of DUSP2 inhibited the activation of ERK. Coming back to our hypothesis, we have found a factor, ERK, whose activation was inhibited by DUSP2 KO.

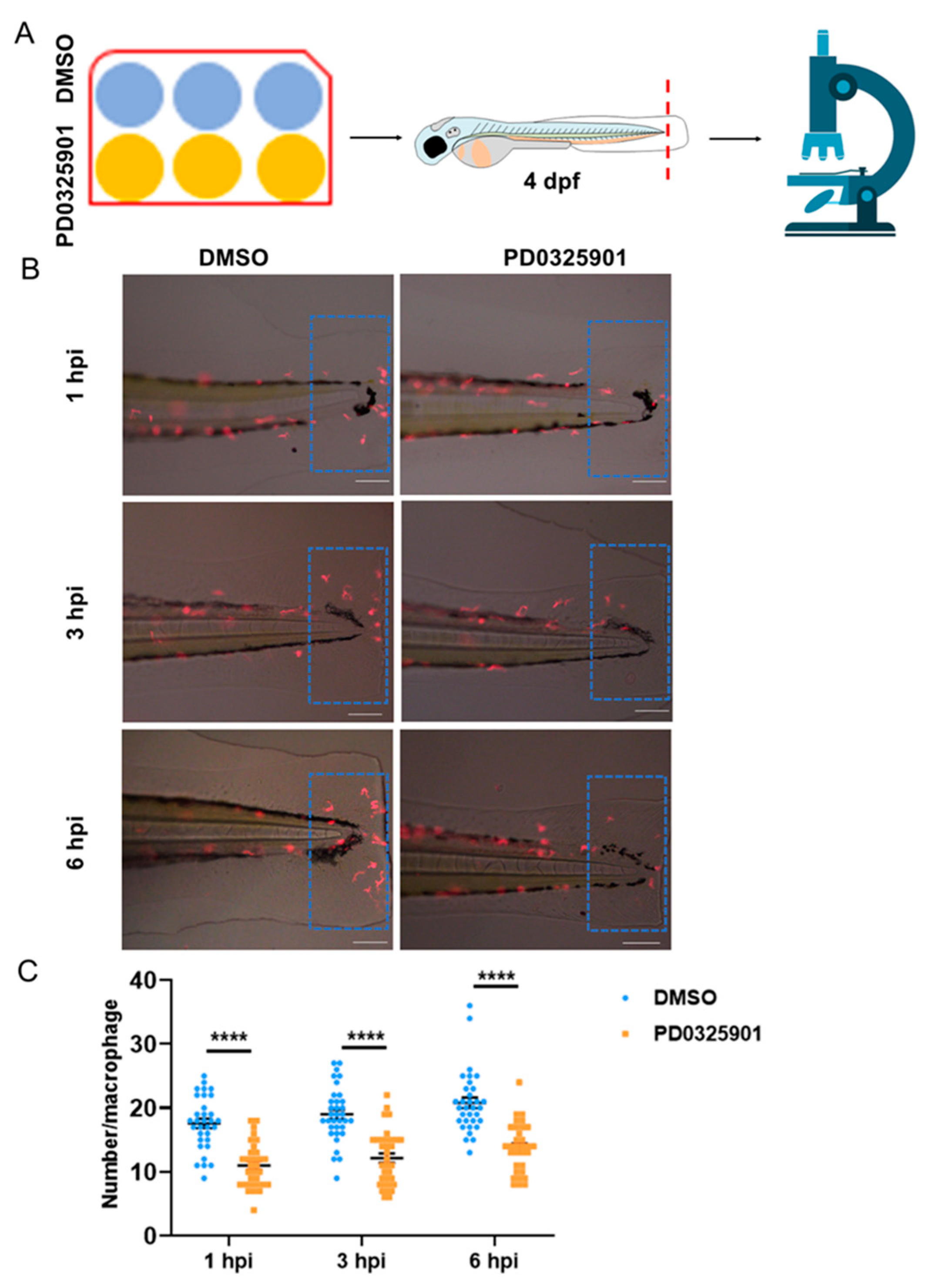

3.5. ERK Inhibitor Inhibited the Migration of Macrophages

Now the missing piece of the puzzle is to validate if reduced activation of ERK leads to fewer migrating macrophages. To this end, we used an inhibitor, PD0325901, to reduce the level of ERK activation [

20,

24]. As expected, the migration of macrophages to the injury site was significantly reduced in the inhibitor group than control (

Figure 7). Taken together, the figure is completed. The reduced migration of macrophages after DUSP2 KO is due to reduced activation of ERK.

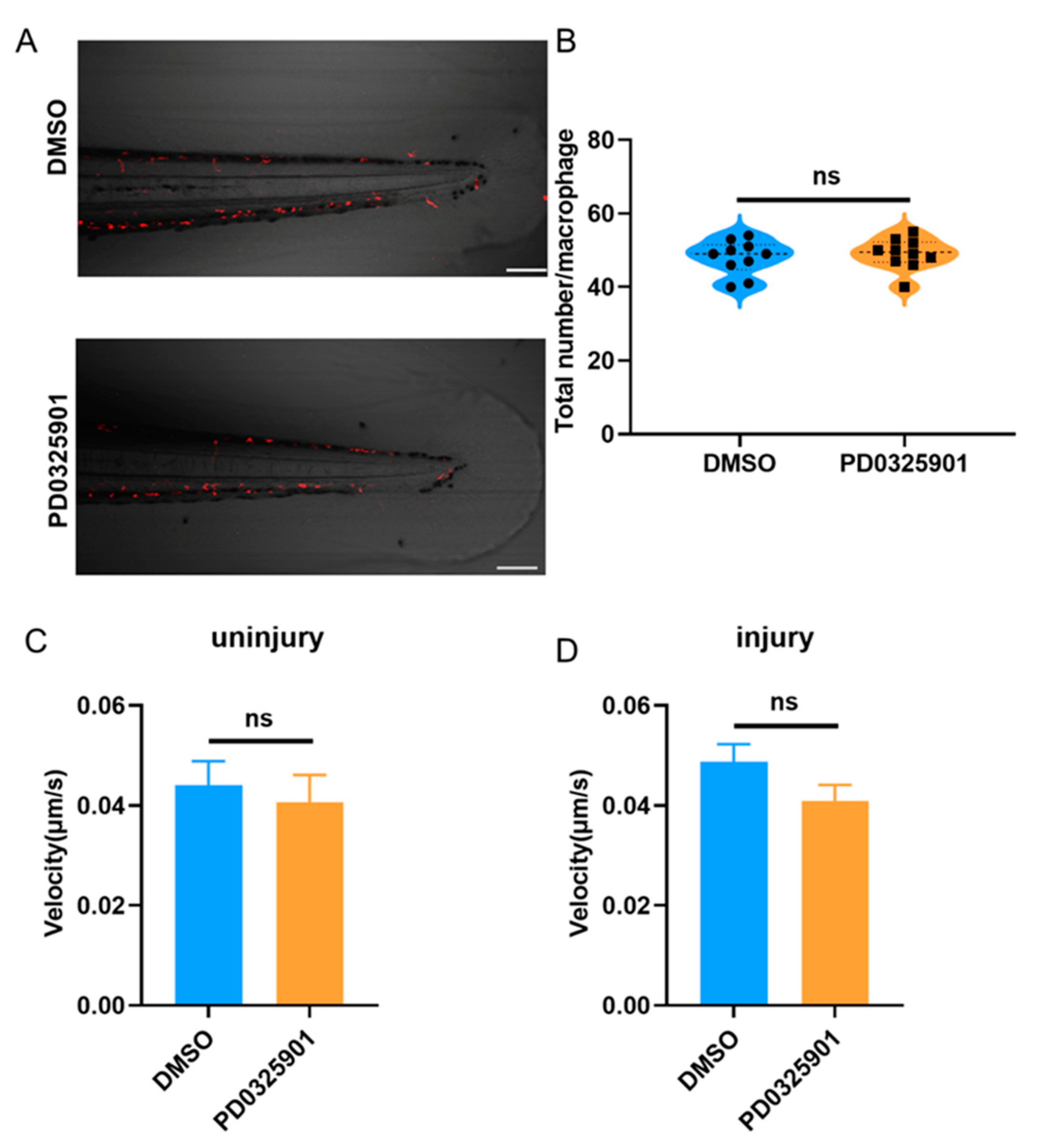

To consolidate our conclusion, we explored whether the total number or motility of macrophages were influenced by inhibitor treatment. Results showed no significant difference in either case (

Figure 8). Thus, ERK inhibitor had no effect on the total number or motility of macrophages in zebrafish larvae. We have further verified our hypothesis that DUSP2 KO reduced macrophage migration via inhibition of ERK activation.

4. Discussion

The acute inflammatory response was induced by tail fin injury. Neutrophils were recruited first at the site of injury, followed by macrophages, and the recruitment of TNF-α-positive pro-inflammatory macrophages peaked at 6 hpa [

25,

26]. In our study, we found that deletion of DUSP2 reduced the migration of macrophages to the injury site at 1 h and 3 h, but not at 6 h after tail fin injury. We speculated that the deletion of DUSP2 might mainly affect the early macrophages recruitment. However, the use of ERK inhibitor inhibited the migration of macrophages to the injury site at 1 h, 3 h, and 6 h after tail fin injury. This suggested that effect of ERK on macrophage was stronger than DUSP2, possibly because ERK was downstream of DUSP2.

The DUSP2 protein regulated the activation of MAPK family, which was involved in a series of cellular processes such as cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis and migration [7,27-31]. MAPK family members mainly included ERK, JNK and p38 [

32,

33]. ERK was involved in regulating the migration of a variety of cells, including macrophages [34-37]. Previous research indicated that deletion of DUPS2 would lead to increased level of phosphorylation of JNK but decreased levels of phosphorylation of ERK and p38 in immune cells [

12]. Our group also demonstrated that deletion of DUSP2 increased the level of phosphorylation of JNK [

16]. In this study, the deletion of DUSP2 led to a decreased level of phosphorylation of ERK, and the use of ERK inhibitor inhibited macrophages migration, suggesting that the effect of DUSP2 on macrophage migration was mediated by ERK activation.

CCL2 was one of the key chemokines of macrophages and was involved in macrophage migration of tail fin injury in zebrafish [

38,

39]. Consistently, in our study, the deletion of DUSP2 suppressed the expression of CCL2 after tail fin injury. This also suggested to us that DUSP2 was involved in the migration of macrophages.

Besides macrophages, another type of phagocytes that are recruited to the injury site in zebrafish are neutrophils. However, in our preliminary experiments, neutrophils behavior between control and DUSP2 KO did not displayed obvious difference. Previous research mentioned that DUSP2 mainly affected the function of macrophages [

12]. Therefore, in this research, we chose macrophage as our object and explored its behavior in detail after DUSP2 KO.

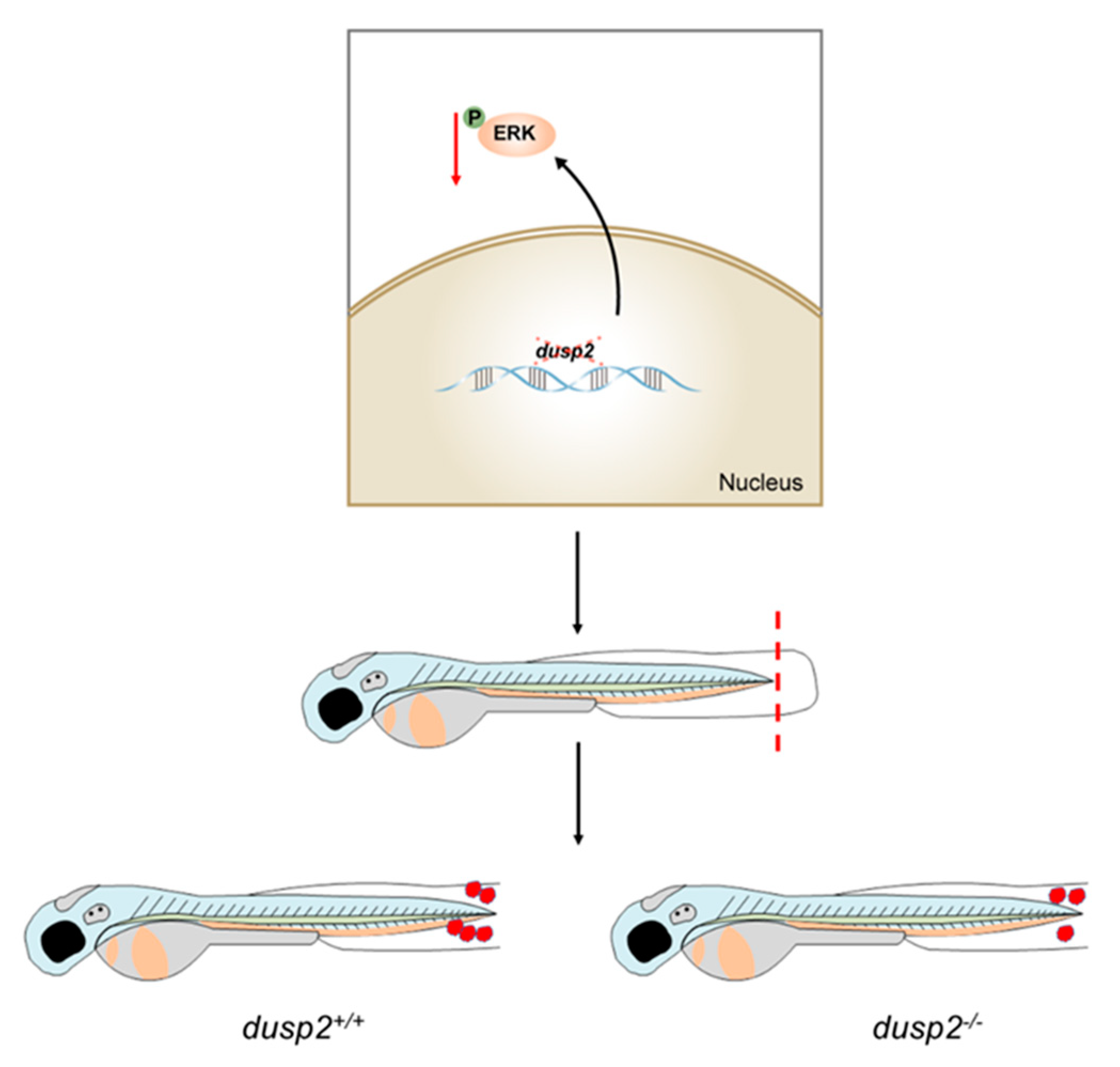

5. Conclusions

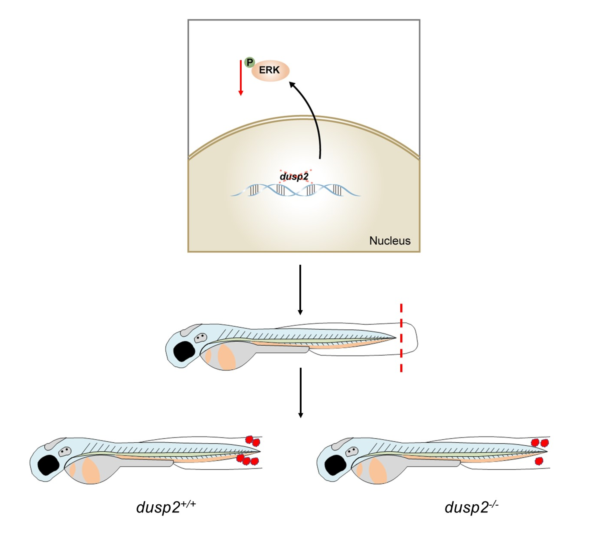

In this study, we found that the expression of

dusp2 was significantly up-regulated in acute inflammation induced by tail fin injury in zebrafish larvae. It was preliminarily speculated that DUSP2 might participate in acute inflammation induced by tail fin injury in zebrafish larvae. Subsequently, it was found that the deletion of DUSP2 inhibited the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and macrophage chemokines after tail fin injury. By using live imaging and conducting tail fin injury in Tg(mpeg1:mCherry);

dusp2-/-,it was found that the deletion of DUSP2 inhibited the migration of macrophages to the injury site. We verified that DUSP2 deletion might inhibit the migration of macrophages by inhibiting the activation of ERK by methods of western blot and ERK inhibitor. To sum up, DUSP2 was involved in the regulation of the migration of macrophages in zebrafish larvae through ERK signal pathway (

Figure 9).

Author Contributions

Yu-Jiao Li, Xin-Liang Wang and Bing Hu designed experiments. Yu-Jiao Li, Xin-Liang Wang, Ling-Yu Shi and Zi-Ang Zhao carried out experiments. Yu-Jiao Li analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. Xin-Liang Wang, Zong-Yi Wang Shu-Chao Ge and Bing Hu revised the manuscript. Yu-Jiao Li, Xin- Liang Wang, Ling-Yu Shi, Zong-Yi Wang, Zi-Ang Zhao, Shu-Chao Ge and Bing Hu had final agreement of the edition to be published. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was granted by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 82071357 and Ministry of Science and Technology of China, No. 2019YFA0405600 (both to BH).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All animal experimental protocols were approved by the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC) Animal Resources Center and University Animal Care and Use Committee and the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments of the USTC (Permit Number: USTCACUC1103013).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the core facility center for life sciences, University of Science and Technology of China.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Trepat, X.; Chen, Z.; Jacobson, K. Cell migration. Compr Physiol 2012, 2, 2369–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheu, K.M.; Hoffmann, A. Functional Hallmarks of Healthy Macrophage Responses: Their Regulatory Basis and Disease Relevance. Annu Rev Immunol 2022, 40, 295–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navegantes, K.C.; de Souza Gomes, R.; Pereira, P.A.T.; Czaikoski, P.G.; Azevedo, C.H.M.; Monteiro, M.C. Immune modulation of some autoimmune diseases: the critical role of macrophages and neutrophils in the innate and adaptive immunity. J Transl Med 2017, 15, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapouri-Moghaddam, A.; Mohammadian, S.; Vazini, H.; Taghadosi, M.; Esmaeili, S.A.; Mardani, F.; Seifi, B.; Mohammadi, A.; Afshari, J.T.; Sahebkar, A. Macrophage plasticity, polarization, and function in health and disease. J Cell Physiol 2018, 233, 6425–6440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, W.J.; Liu, J.X.; Liu, M.N.; Yao, Y.D.; Liu, Z.Q.; Liu, L.; He, H.H.; Zhou, H. Macrophage 3D migration: A potential therapeutic target for inflammation and deleterious progression in diseases. Pharmacol Res 2021, 167, 105563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, R.; Hammer, M.; Mages, J. DUSP meet immunology: dual specificity MAPK phosphatases in control of the inflammatory response. J Immunol 2006, 177, 7497–7504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.H.; Lin, S.C.; Hsiao, K.Y.; Tsai, S.J. Hypoxia-inhibited dual-specificity phosphatase-2 expression in endometriotic cells regulates cyclooxygenase-2 expression. J Pathol 2011, 225, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loesch, M.; Chen, G. The p38 MAPK stress pathway as a tumor suppressor or more? Front Biosci 2008, 13, 3581–3593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, R.R.; Gereau, R.W.t.; Malcangio, M.; Strichartz, G.R. MAP kinase and pain. Brain Res Rev 2009, 60, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Sheng, H.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, Y. Network pharmacology study to reveal active compounds of Qinggan Yin formula against pulmonary inflammation by inhibiting MAPK activation. J Ethnopharmacol 2022, 296, 115513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kciuk, M.; Gielecińska, A.; Budzinska, A.; Mojzych, M.; Kontek, R. Metastasis and MAPK Pathways. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffrey, K.L.; Brummer, T.; Rolph, M.S.; Liu, S.M.; Callejas, N.A.; Grumont, R.J.; Gillieron, C.; Mackay, F.; Grey, S.; Camps, M.; et al. Positive regulation of immune cell function and inflammatory responses by phosphatase PAC-1. Nat Immunol 2006, 7, 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dan, L.; Liu, L.; Sun, Y.; Song, J.; Yin, Q.; Zhang, G.; Qi, F.; Hu, Z.; Yang, Z.; Zhou, Z.; et al. The phosphatase PAC1 acts as a T cell suppressor and attenuates host antitumor immunity. Nat Immunol 2020, 21, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, D.; Liu, L.; Ji, X.; Gao, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; et al. The phosphatase DUSP2 controls the activity of the transcription activator STAT3 and regulates TH17 differentiation. Nat Immunol 2015, 16, 1263–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellett, F.; Pase, L.; Hayman, J.W.; Andrianopoulos, A.; Lieschke, G.J. mpeg1 promoter transgenes direct macrophage-lineage expression in zebrafish. Blood 2011, 117, e49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, G.J.; Wang, X.L.; Wei, M.L.; Ren, D.L.; Hu, B. DUSP2 deletion with CRISPR/Cas9 promotes Mauthner cell axonal regeneration at the early stage of zebrafish. Neural Regen Res 2023, 18, 577–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockhammer, O.W.; Zakrzewska, A.; Hegedûs, Z.; Spaink, H.P.; Meijer, A.H. Transcriptome profiling and functional analyses of the zebrafish embryonic innate immune response to Salmonella infection. J Immunol 2009, 182, 5641–5653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugman, S. The zebrafish as a model to study intestinal inflammation. Dev Comp Immunol 2016, 64, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoa, B.; Figueras, A. Zebrafish: model for the study of inflammation and the innate immune response to infectious diseases. Adv Exp Med Biol 2012, 946, 253–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Gong, Y.; Zhang, W.; Qiu, J.; Zheng, X.; Li, Z.; Yang, G.; Hong, Z. PD0325901, an ERK inhibitor, attenuates RANKL-induced osteoclast formation and mitigates cartilage inflammation by inhibiting the NF-κB and MAPK pathways. Bioorg Chem 2022, 132, 106321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Chi, M.; Laplace-Builhé, B.; Travnickova, J.; Luz-Crawford, P.; Tejedor, G.; Lutfalla, G.; Kissa, K.; Jorgensen, C.; Djouad, F. TNF signaling and macrophages govern fin regeneration in zebrafish larvae. Cell Death Dis 2017, 8, e2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, D.L.; Li, Y.J.; Hu, B.B.; Wang, H.; Hu, B. Melatonin regulates the rhythmic migration of neutrophils in live zebrafish. J Pineal Res 2015, 58, 452–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Yan, B.; Shi, Y.Q.; Zhang, W.Q.; Wen, Z.L. Live imaging reveals differing roles of macrophages and neutrophils during zebrafish tail fin regeneration. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 25353–25360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, L.; Sun, S.; Tang, L.S.; He, S.M.; Chen, A.Q.; Yao, L.N.; Ren, D.L. Cordycepin inhibits inflammatory responses through suppression of ERK activation in zebrafish. Dev Comp Immunol 2021, 124, 104178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Bos, R.; Cromwijk, S.; Tschigg, K.; Althuizen, J.; Zethof, J.; Whelan, R.; Flik, G.; Schaaf, M. Early Life Glucocorticoid Exposure Modulates Immune Function in Zebrafish (Danio rerio) Larvae. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohaud, C.; Johansen, M.D.; Jorgensen, C.; Ipseiz, N.; Kremer, L.; Djouad, F. The Role of Macrophages During Zebrafish Injury and Tissue Regeneration Under Infectious and Non-Infectious Conditions. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 707824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Whelan, E.C.; Guan, X.; Deng, B.; Wang, S.; Sun, J.; Avarbock, M.R.; Wu, X.; Brinster, R.L. FGF9 promotes mouse spermatogonial stem cell proliferation mediated by p38 MAPK signalling. Cell Prolif 2021, 54, e12933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Zhao, S.; Tan, Y.; Pan, S.; An, W.; Chen, Q.; Wang, X.; Xu, H. The SKA3-DUSP2 Axis Promotes Gastric Cancer Tumorigenesis and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition by Activating the MAPK/ERK Pathway. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 777612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, N.; Li, X.; Xue, C.; Zhang, L.; Wang, C.; Xu, X.; Shan, A. Astragalus polysaccharides alleviates LPS-induced inflammation via the NF-κB/MAPK signaling pathway. J Cell Physiol 2020, 235, 5525–5540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, G.I.; Kraakman, M.J.; Kammoun, H.L.; Langley, K.G.; Estevez, E.; Banerjee, A.; Grumont, R.J.; Febbraio, M.A.; Gerondakis, S. The dual-specificity phosphatase 2 (DUSP2) does not regulate obesity-associated inflammation or insulin resistance in mice. PLoS One 2014, 9, e111524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, W.Z.; Liu, T.; Feng, X.; Yang, N.; Zhou, H.F. Signaling pathway of MAPK/ERK in cell proliferation, differentiation, migration, senescence and apoptosis. J Recept Signal Transduct Res 2015, 35, 600–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.J.; Pan, W.W.; Liu, S.B.; Shen, Z.F.; Xu, Y.; Hu, L.L. ERK/MAPK signalling pathway and tumorigenesis. Exp Ther Med 2020, 19, 1997–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decean, H.P.; Brie, I.C.; Tatomir, C.B.; Perde-Schrepler, M.; Fischer-Fodor, E.; Virag, P. Targeting MAPK (p38, ERK, JNK) and inflammatory CK (GDF-15, GM-CSF) in UVB-Activated Human Skin Cells with Vitis vinifera Seed Extract. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol 2018, 37, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmo, A.A.; Costa, B.R.; Vago, J.P.; de Oliveira, L.C.; Tavares, L.P.; Nogueira, C.R.; Ribeiro, A.L.; Garcia, C.C.; Barbosa, A.S.; Brasil, B.S.; et al. Plasmin induces in vivo monocyte recruitment through protease-activated receptor-1-, MEK/ERK-, and CCR2-mediated signaling. J Immunol 2014, 193, 3654–3663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bose, S.; Kim, S.; Oh, Y.; Moniruzzaman, M.; Lee, G.; Cho, J. Effect of CCL2 on BV2 microglial cell migration: Involvement of probable signaling pathways. Cytokine 2016, 81, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samson, S.C.; Khan, A.M.; Mendoza, M.C. ERK signaling for cell migration and invasion. Front Mol Biosci 2022, 9, 998475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.L.; Hu, Z.Q.; Zhou, Z.J.; Dai, Z.; Wang, Z.; Cao, Y.; Fan, J.; Huang, X.W.; Zhou, J. miR-28-5p-IL-34-macrophage feedback loop modulates hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis. Hepatology 2016, 63, 1560–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talsma, A.D.; Niemi, J.P.; Pachter, J.S.; Zigmond, R.E. The primary macrophage chemokine, CCL2, is not necessary after a peripheral nerve injury for macrophage recruitment and activation or for conditioning lesion enhanced peripheral regeneration. J Neuroinflammation 2022, 19, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Tolmeijer, S.; Oskam, J.M.; Tonkens, T.; Meijer, A.H.; Schaaf, M.J.M. Glucocorticoids inhibit macrophage differentiation towards a pro-inflammatory phenotype upon wounding without affecting their migration. Dis Model Mech 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

(A) Previously constructed zebrafish strain with dusp2 mutation by CRISPR/Cas9. (B) Generation of Tg(mpeg1:mCherry); dusp2-/- zebrafish.

Figure 1.

(A) Previously constructed zebrafish strain with dusp2 mutation by CRISPR/Cas9. (B) Generation of Tg(mpeg1:mCherry); dusp2-/- zebrafish.

Figure 2.

(A) Collection of WT zebrafish larvae without tail fin injury and 1 h after tail fin injury for total RNA extraction. (B–F) The mRNA expression levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β (B), IL-8 (C) and TNF-α (D), and macrophage chemokines CCL2 (E) and CXCL11 (F) were significantly higher in tail fin injury samples than control. (G) The mRNA expression levels of dusp2 were significantly up-regulated in tail fin injury larvae. *p < 0.05, ** p< 0.01, ****p < 0.0001. Error bars represent SEM.

Figure 2.

(A) Collection of WT zebrafish larvae without tail fin injury and 1 h after tail fin injury for total RNA extraction. (B–F) The mRNA expression levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β (B), IL-8 (C) and TNF-α (D), and macrophage chemokines CCL2 (E) and CXCL11 (F) were significantly higher in tail fin injury samples than control. (G) The mRNA expression levels of dusp2 were significantly up-regulated in tail fin injury larvae. *p < 0.05, ** p< 0.01, ****p < 0.0001. Error bars represent SEM.

Figure 3.

(A) Collection of WT and dusp2-/- zebrafish larvae without tail fin injury and 1 h after tail fin injury for total RNA extraction. (B–F) The mRNA expression levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β (B), IL-6 (C), IL-8 (D) and TNF-α (E), and macrophage chemokines CCL2 (F) and CXCL11 (G) were not significantly different between the dusp2 mutant and WT groups in the absence of tail fin injury. The mRNA expression levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β (B), IL-6 (C) and IL-8 (D), and macrophage chemokine CCL2 (F) were significantly lower in dusp2 mutant than WT groups after tail fin injury. The mRNA expression levels of TNF-α (E) and CXCL11 (G) were not significantly different between the dusp2 mutant and WT groups after tail fin injury. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns: no significance; Error bars represent SEM.

Figure 3.

(A) Collection of WT and dusp2-/- zebrafish larvae without tail fin injury and 1 h after tail fin injury for total RNA extraction. (B–F) The mRNA expression levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β (B), IL-6 (C), IL-8 (D) and TNF-α (E), and macrophage chemokines CCL2 (F) and CXCL11 (G) were not significantly different between the dusp2 mutant and WT groups in the absence of tail fin injury. The mRNA expression levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β (B), IL-6 (C) and IL-8 (D), and macrophage chemokine CCL2 (F) were significantly lower in dusp2 mutant than WT groups after tail fin injury. The mRNA expression levels of TNF-α (E) and CXCL11 (G) were not significantly different between the dusp2 mutant and WT groups after tail fin injury. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ns: no significance; Error bars represent SEM.

Figure 4.

(A) Schematic diagram of macrophages migrating to the injury site at various time points after tail fin injury. (B) The number of macrophages migrating to the injury site were significantly reduced in dusp2 mutant groups than control at 1 h and 3 h after injury. The number of macrophages migrating to the injury site were not significantly different between the dusp2 mutant and control groups at 6 h after injury. The results of this experiment were obtained from three independent experiments; The blue dashed box indicates the statistical region of macrophage; scale bar: 100 μm; hpi: Hour post-injury. **p < 0.01, ns: no significance; Error bars represent SEM.

Figure 4.

(A) Schematic diagram of macrophages migrating to the injury site at various time points after tail fin injury. (B) The number of macrophages migrating to the injury site were significantly reduced in dusp2 mutant groups than control at 1 h and 3 h after injury. The number of macrophages migrating to the injury site were not significantly different between the dusp2 mutant and control groups at 6 h after injury. The results of this experiment were obtained from three independent experiments; The blue dashed box indicates the statistical region of macrophage; scale bar: 100 μm; hpi: Hour post-injury. **p < 0.01, ns: no significance; Error bars represent SEM.

Figure 5.

(A) Schematic diagram of macrophages within 800 μm from the end of the spinal cord forward. (B) The total number of macrophages in zebrafish larvae were not significantly different between the dusp2 mutant and control groups. (C) Movement velocity of macrophages were not significantly different between the dusp2 mutant and control groups in the absence of tail fin injury. (D) Movement velocity of macrophages migrating to the injury site were not significantly different between the dusp2 mutant and control groups at 2.5 hpi - 3 hpi. Scale bar: 100 μm; hpi: Hour post-injury; ns: no significance; Error bars represent SEM.

Figure 5.

(A) Schematic diagram of macrophages within 800 μm from the end of the spinal cord forward. (B) The total number of macrophages in zebrafish larvae were not significantly different between the dusp2 mutant and control groups. (C) Movement velocity of macrophages were not significantly different between the dusp2 mutant and control groups in the absence of tail fin injury. (D) Movement velocity of macrophages migrating to the injury site were not significantly different between the dusp2 mutant and control groups at 2.5 hpi - 3 hpi. Scale bar: 100 μm; hpi: Hour post-injury; ns: no significance; Error bars represent SEM.

Figure 6.

(A) Representative graph of the results of Western Blot in the absence of injury, with data from three sets of samples. (B) Representative graph of the results of Western Blot after tail fin injury, data from three sets of samples. (C) Statistical plot of ERK1/2 protein levels in the absence of injury: there was no significant difference in the background levels of ERK1/2 between the dusp2 mutant and control groups. (D) Statistical plot of p-ERK protein levels in the absence of injury: the levels of p-ERK were significantly decreased in the dusp2 mutant group. (E) Statistical plot of ERK1/2 protein levels after tail fin injury: there was no significant difference in the background levels of ERK1/2 between the dusp2 mutant and control groups. (F) Statistical plot of p-ERK protein levels after tail fin injury: the levels of p-ERK were significantly decreased in the dusp2 mutant group. *p < 0.05; ns: no significance; Error bars represent SEM.

Figure 6.

(A) Representative graph of the results of Western Blot in the absence of injury, with data from three sets of samples. (B) Representative graph of the results of Western Blot after tail fin injury, data from three sets of samples. (C) Statistical plot of ERK1/2 protein levels in the absence of injury: there was no significant difference in the background levels of ERK1/2 between the dusp2 mutant and control groups. (D) Statistical plot of p-ERK protein levels in the absence of injury: the levels of p-ERK were significantly decreased in the dusp2 mutant group. (E) Statistical plot of ERK1/2 protein levels after tail fin injury: there was no significant difference in the background levels of ERK1/2 between the dusp2 mutant and control groups. (F) Statistical plot of p-ERK protein levels after tail fin injury: the levels of p-ERK were significantly decreased in the dusp2 mutant group. *p < 0.05; ns: no significance; Error bars represent SEM.

Figure 7.

(A) Zebrafish larvae at 4 dpf were pretreated with PD0325901, and after tail fin injury, treatment with PD0325901 was continued, followed by observation of macrophages migrating to the injury site under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus BX60, Japan). (B) Schematic representation of macrophages migrating to the injury site at various time points after tail fin injury. (C) The number of macrophages migrating to the injury site was significantly reduced in the PD0325901 group than control. The results of this experiment were obtained from three independent experiments; The red dashed line indicates the site of injury; The blue dashed box indicates the statistical region of macrophage; hpi: Hour post-injury; scale bar: 100 μm.****p < 0.0001; Error bars represent SEM.

Figure 7.

(A) Zebrafish larvae at 4 dpf were pretreated with PD0325901, and after tail fin injury, treatment with PD0325901 was continued, followed by observation of macrophages migrating to the injury site under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus BX60, Japan). (B) Schematic representation of macrophages migrating to the injury site at various time points after tail fin injury. (C) The number of macrophages migrating to the injury site was significantly reduced in the PD0325901 group than control. The results of this experiment were obtained from three independent experiments; The red dashed line indicates the site of injury; The blue dashed box indicates the statistical region of macrophage; hpi: Hour post-injury; scale bar: 100 μm.****p < 0.0001; Error bars represent SEM.

Figure 8.

(A) Schematic diagram of macrophages within 800 μm from the end of the spinal cord forward. (B) The total number of macrophages in zebrafish larvae were not significantly different between the PD0325901 group and control. (C) Movement velocity of macrophages were not significantly different between the PD0325901 group and control in the absence of tail fin injury. (D) Movement velocity of macrophages migrating to the injury site were not significantly different between the PD0325901 group and control at 2.5 hpi - 3 hpi. Scale bar: 100 μm; hpi: Hour post-injury; ns: no significance; Error bars represent SEM.

Figure 8.

(A) Schematic diagram of macrophages within 800 μm from the end of the spinal cord forward. (B) The total number of macrophages in zebrafish larvae were not significantly different between the PD0325901 group and control. (C) Movement velocity of macrophages were not significantly different between the PD0325901 group and control in the absence of tail fin injury. (D) Movement velocity of macrophages migrating to the injury site were not significantly different between the PD0325901 group and control at 2.5 hpi - 3 hpi. Scale bar: 100 μm; hpi: Hour post-injury; ns: no significance; Error bars represent SEM.

Figure 9.

Working mechanism diagram of DUSP2.

Figure 9.

Working mechanism diagram of DUSP2.

Table 1.

Primers used in this study.

Table 1.

Primers used in this study.

| Gene |

Forward primer |

Reverse primer |

| il1β |

GTACTCAAGGAGATCAGCGG |

CTCGGTGTCTTTCCTGTCCA |

| il6 |

TTTGAAGGGGTCAGGATCAG |

TCATCACGCTGGAGAAGTTG |

| il8 |

CACTTAGGCAAAATGACCAGCA |

AGACCTCTCAAGCTCATTCCTTC |

| tnfα |

GCGCTTTTCTGAATCCTACG |

TGCCCAGTCTGTCTCCTTC |

| dusp2 |

ATCGGCGACCCTCTCGAGATCTC |

GACACCACGGAGCTCTTGGACCT |

| cxcl11 |

GGCACAGTGAAGAGCTCCAT |

TGAGCTTGTTTGGGCAGTGT |

| ccl2 |

TCTGCACTAACCCGACTGAGA |

CATCTTAGGCGCTGTCACCAG |

| β-actin |

TCCGGTATGTGCAAAGCCGG |

CCACATCTGCTGGAAGGTGG |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).