1. Introduction

Early detection of wound status via wound biomarker examination has the potential to prevent acute and chronic wounds from worsening. In addition to facilitating early clinical detection of symptomatic wounds, wound-related biomarkers serve as surrogate markers to predict wound outcomes and promote prompt therapeutic intervention. Some wound-fluid or tissue-derived factors, such as metalloproteinase enzymes (MMPs), growth factors, and interleukins, have been reported to serve as potential markers for predicting wound outcomes [

1].

It is clear that microRNA (miRNA), involved in gene regulation to control cellular pathways, has become a powerful diagnostic tool with medical implications. The role of miRNAs in skin wound healing is well-established [

2]. MiRNA-155 was reported to be highly expressed in the inflammatory phase of wound repair [

3]. MicroRNA-21(MiR-21) has also been shown to have an anti-inflammatory role and was upregulated in macrophages when alleviating inflammation [

4]. Extracellular vesicles such as exosomes have been developed as important mediators for transmitting intercellular biological signals, including miRNAs, to modulate cellular function [

5]. Although nucleic acid testing (NAT) has been widely used for disease diagnosis, food safety control, and environmental monitoring, it currently requires laborious off-chip exosome separation and nucleic acid extraction prior to detection. Exosomal miRNAs have been shown to act as better biomarkers than non-exosomal miRNAs for disease diagnosis [

6]. However, using exosomal miR-21 to determine wound prognosis has not been studied until now.

Paper-based ELISA (P-ELISA), a well-developed and convenient tool in diagnostic medicine, has been widely applied to examine the state and severity of various diseases [

7,

8]. We successfully identified high human neutrophil elastase expression levels in chronic wound fluids using P-ELISA [

9]. Here, we developed an easy-to-use, rapid, paper-based microfluidic-extraction device to investigate wound status by analyzing exosomal miR-21 in wound fluids using real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). Results may be used to help determine wound prognosis and consequently provide better wound management.

2. Results

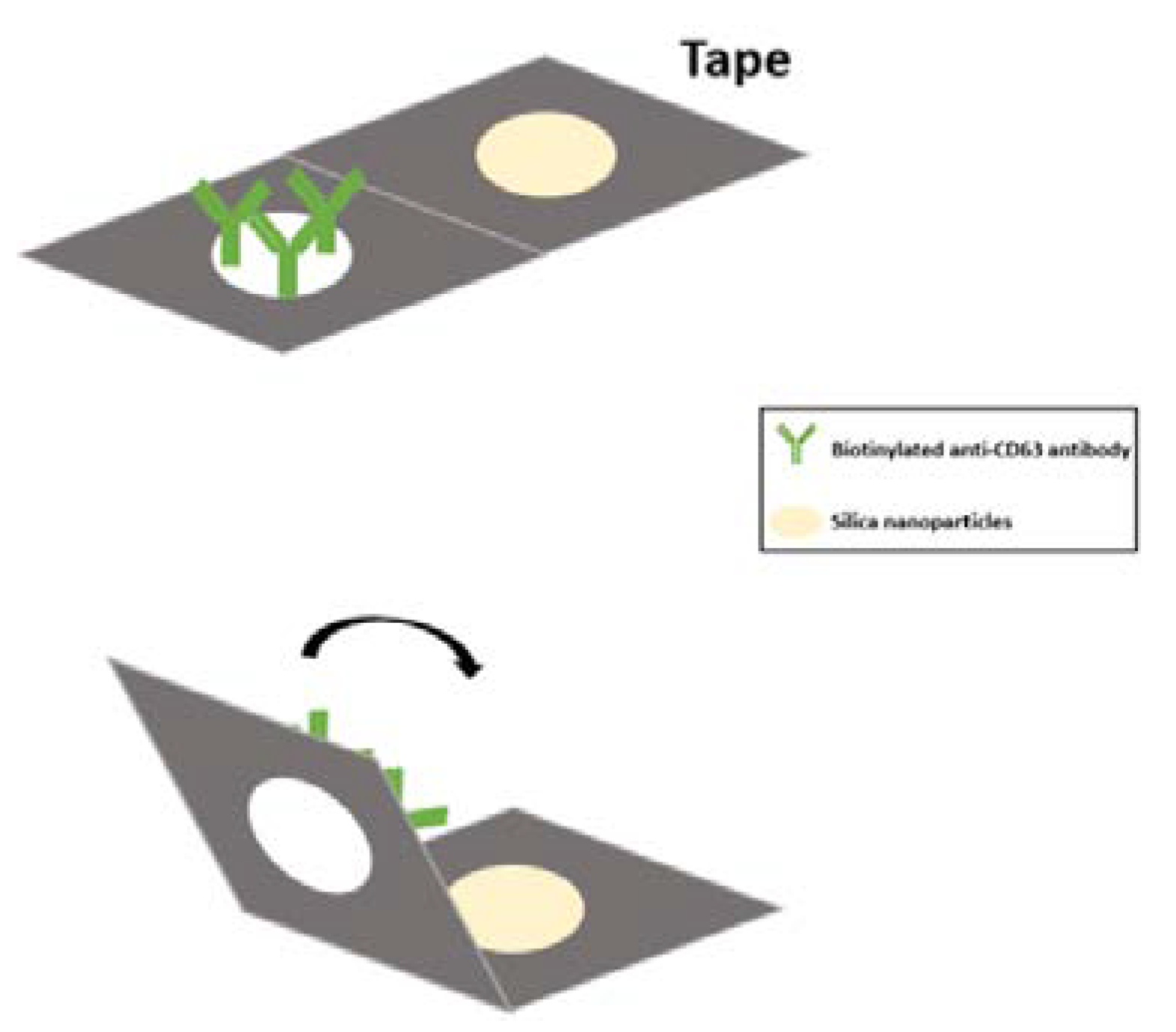

2.1. Development of Paper-based Nucleic Acid Extraction Device

To detect a particular nucleic acid in our wound fluid samples, we developed a 3D paper-based nucleic acid extraction device by coating Whatman grade 1 filter paper with silica to reinforce nucleic acid binding (

Figure 1). Nucleic acids were then adsorbed onto the silica nanoparticle surface using a binding solution with a pH value lower than the pKa value of the silicon OH group (pH=4) [

10]. In this manner, Whatman grade 1 filter paper was made suitable for use as a paper-based immunoaffinity device and a paper-based nucleic acid extraction device. Hydrophobic and hydrophilic areas were clearly divided by All Purpose Duct Tape DT8 (3M™) to create different microfluidic device types. Specific exosomal antibody, anti-CD63 antibody, was coated onto the device to isolate exosomes from wound fluids. Based on this design, sample fluid was added to the inlet port on the paper-based immunoaffinity device to capture exosomes by CD63 binding. After exosomal cleavage with lysis buffer, nucleic acids in the exosomes were adsorbed by the silica nanoparticle onto the paper-based nucleic acid extraction device in a salt buffer solution at pH higher than the pKa of silicon surface OH groups or in dd water at an elevated temperature (55°C). Morphology and size of captured exosomes were analyzed by SEM and qNano, respectively. We further used paper-based exosomal nucleic acid extraction devices and antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase to produce a colorimetric readout. The miRNA expression levels could be quantified by real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) to assess wound status within 30 min.

To achieve rapid assessment of nucleic acid for point-of-care testing (POCT), a paper-based nucleic acid extraction device was developed to replace traditional nucleic acid extraction procedures. This approach requires no expensive or large instruments, and ultracentrifugation or ultrafiltration are not necessary. This paper-based approach easily handles exosome extraction and serves as an avenue for point-of-care testing development. In this process, Whatman grade 1 filter paper was cut to a suitable size. The filter paper was coated with 20 µL of Silanol solution (3 mg/mL in dH2O) on both sides and was desiccated at room temperature. In order to maintain clinical result consistency, all parameters such as adsorption time, elution time, temperature, and pH value used were fixed [

10]. To improve the efficiency of the device and facilitate maximal adsorption and elution ability of nucleic acid, the binding buffer was set at pH=4. At room temperature, hydroxyl on the silanol surface reduced negative charge repulsion force and provided more room for hydrogen binding with nucleic acid. The adsorptive ability of nucleic acid was aided by a reduced electrostatic repulsive force and promoted by the hydrogen and possible salt bridge between nucleic acid and the silicon-surface OH group, which was relatively stable in the pH 4 and room-temperature environment. To meet POCT criteria, we aimed to assess nucleic acid levels at room temperature. According to a previous study, elution rate was better at 55°C than room temperature [

11]. We then chose a pH 9 solution as our elution buffer and warmed it up to 55°C for 45 min to increase deprotonation and negative charges on the Silanol surface. Thus, elution of nucleic acid was made by cleavage of hydrogen bonds between silica and nucleic acid.

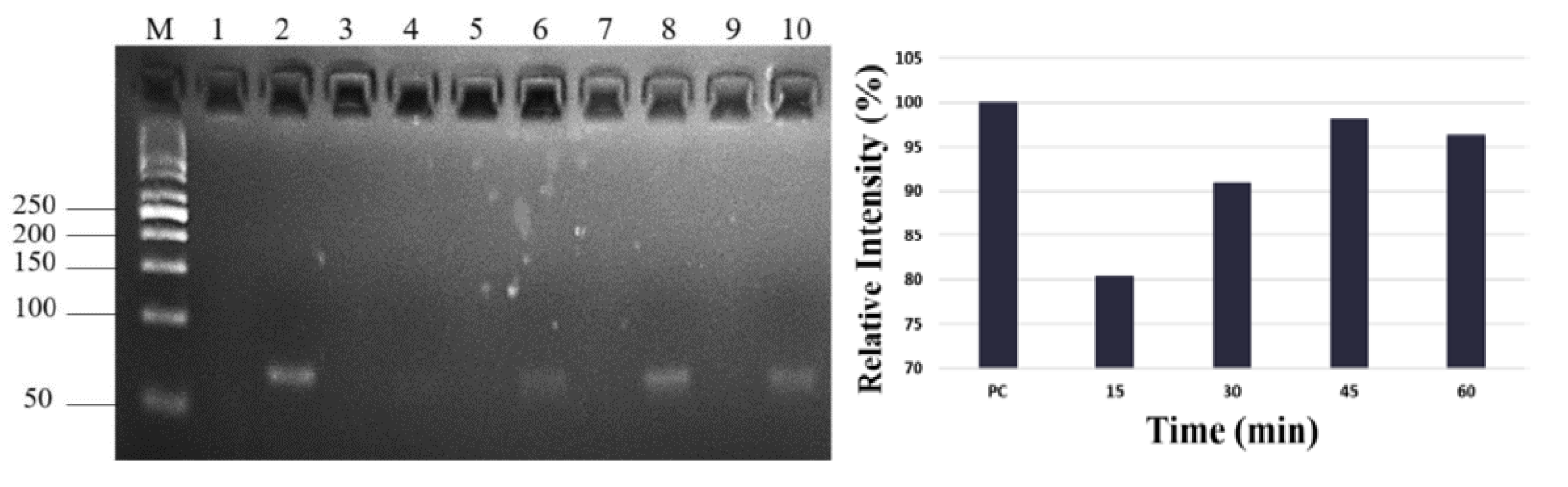

We then chose miR-21 samples to study elution time. Elution time points for observation via electrophoresis were 15 min, 30 min, 45 min, and 60 min (

Figure 2A). The data show that elution concentration increased with time and reached its highest capacity at 45 min (

Figure 2B). To reduce the unstable pH value and examination bias of qRT-PCR caused by the tiny sample volume, we selected ddH2O as our binding and elution buffer. To determine optimal PCR reaction conditions, synthesized miR-21 was diluted into 109 copies/µL, 108 copies/µL, 107 copies/µL, 106 copies/µL, and 105 copies/µL and applied to the paper-based nucleic acid extraction device. Samples were bound with ddH2O for 3 min at room temperature and then desorbed for 45 min at 55°C. A PCR calibration curve and an amplification plot were used to determine the quantitative levels of miR-21.

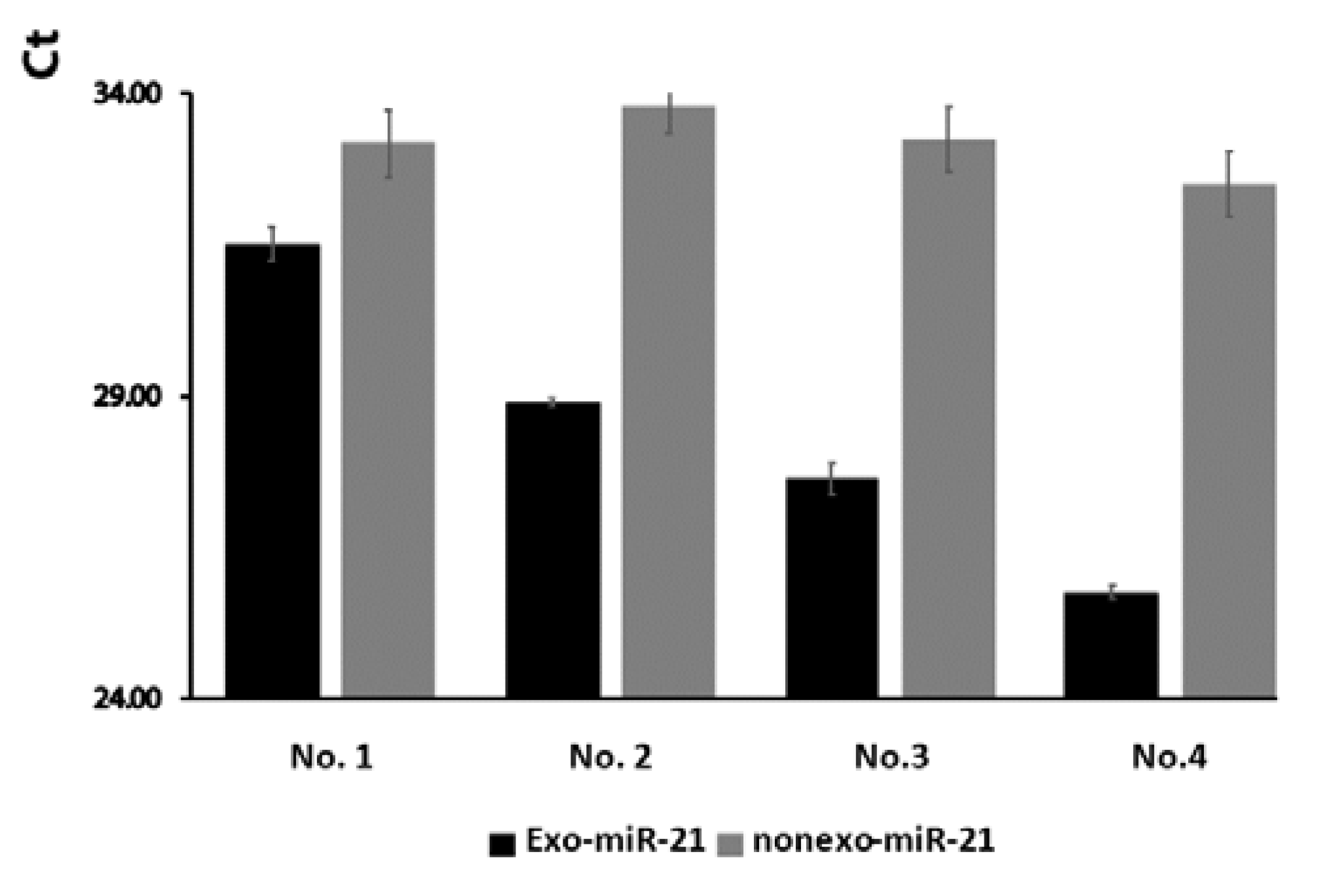

2.2. The Expression Levels of Exosomal miR-21 were Higher than Non-Exosomal miR-21 from Wound Fluids

Previous study has shown that a majority of miRNAs are expressed in the exosomal serum of hepatocellular carcinoma patients [

12] and exosomal saliva [

13]. However, differences in miR-21 concentration in accordance with different wound conditions have not been previously addressed. We thus examined the differences between exosomal and non-exosomal miR-21 in wound fluids. Our data show that expression levels of exosomal miR-21 were higher than those for non-exosomal miR-21 from wound tissue (

Figure 3).

To further understand the role of exosomal miR-21 in clinical wound status, we used a paper-based nucleic acid extraction device to investigate exosomal miR-21 in wound fluids. We first tested 3 chronic wound samples originating from three different body parts (left leg, right leg, left elbow) of one patient with multiple simultaneous injuries. Samples were added directly to the antibody-coated zones without preprocessing, and RT-qPCR was once again used as a finished product evaluation tool. The obtained Ct values show negligible differences in exosomal miR-21 levels between the three samples (Ct values, left leg=32.86+/-0.49; Right leg=32.85+/-0.40; left elbow=33.67+/-0.29), indicating that exosomal miRNA-21 in wound fluid was independent of the injured location as long as the same physiological and treatment conditions were experienced.

2.3. Higher Exosomal miR-21 is Associated with Poor Wound Healing

A previous study demonstrated that all significant miRNAs could be detected in circulating exosomes of tongue cancer patients, compared to less detectable miRNAs in patient plasma [

14]. We, therefore, studied the value of exosomal miR-21 and non-exosomal, free miR-21 in wound tissue for wound assessment. Exosomal miR-21 was isolated from patients with normal tissue and acute and chronic wound fluids. Normal tissue displayed a wide range of exosomal miR-21 expression. There were no significant differences in miR-21 expression between normal tissue, acute, and chronic wounds (Ct values, normal tissue=28.95+/-1.29, 25.77-31.69, n=11, acute=29.73+/-1.53, n=36; chronic=29.93+/-1.17, n=21, P=0.71). This result may is in keeping with a previous report indicating limitations in studying patient miRNAs due to such characteristics as age [

15]. Although no significant differences in exosomal miR-21 expression were observed between acute and chronic wounds, we did observe a differential exosomal miR-21 expression in the same patient in accordance with different wound status. This study also examined changes in wound tissue exosomal miR-21 among 13 patients before and after wound debridement. Eight improving wounds displayed lower levels of exosomal miR-21 expression after wound debridement. However, 4 cases of increased exosomal miR-21 expression levels were noticed in poor healing wounds despite aggressive wound debridement (

Table 1), indicating a predictive role of exosomal miR-21 for wound outcome (same patient).

3. Discussion

With the increasing need for point-of-care wound assessment, we developed an inexpensive and easy-to-use paper-based nucleic acid detection device to investigate exosomal miR-21 in wound fluids that was superior to traditional methods that require expensive infrastructure and time-consuming processes. This paper-based nucleic acid extraction device provides a potent, user-friendly approach for capturing exosomes for analysis by SEM and qNano to examine morphology and size, respectively. When exosomal miR-21 was successfully extracted from wound fluids, a colorimetric readout was produced within 30 min. The data was analyzed using real-time PCR to provide information for wound assessment. Our data suggest that exosomal miR-21 is a reliable marker for the early detection of wound status. The paper-based exosomal miR-21 extraction device developed in this study may be leveraged to produce a promising, first-of-its-kind screening tool for clinical wound monitoring.

MiR-21 is the most widely studied miRNAs in cancer and heart diseases [

16,

17]. MiR-21 could be found in the cytosol, exosome, neoplastic and non-neoplastic cells [

18]. As a result of interaction with cell membrane protein, exosomal miR-21 was less vulnerable to extracellular RNase degradation [

16]. After activation, miR-21 could be released from exosome and remain stable by natural leakage in the serum or body fluids [

19]. In addition, a previous study demonstrated a similar expression profile for miR-21 between tissue and plasma samples from breast cancer patients [

20], and most studies have shown that a majority of miRNAs are expressed in the exosomal serum of hepatocellular carcinoma patients [

12] and exosomal saliva [

13]. Sensitivity was higher when using exosomal miR-21 as a biomarker for diagnosing hepatocellular carcinoma compared to detection by serum miR-21 [

21], which further supports our finding that exosomal miR-21, rather than non-exosomal miR-21 in wound tissue, might be a better prognostic marker for wound assessment. Furthermore, miR-21 was detected in different kinds of body fluids such as urine, saliva, tears and breast milk [

22]. MiRNAs in body fluids might indicate specific role associated with the surrounding tissues [

22]. We showed here that exosomal miR-21 was exceptional stability present in the wound tissue fluids, indicating the development of exosomal miR-21 as a novel tool of tissue-based wound biomarkers.

MicroRNAs have recently been recognized as important regulators in skin wound healing [

23]. They have been reported to regulate healing processes such as proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis [

24]. MiR-21 was found to be up-regulated in activated epithelial cells and mesenchymal cells and involved in wound contracture and collagen deposition in mice [

25]. However, differences in miR-21 concentration in accordance with different wound conditions have not been previously addressed. Our study highlighted the value of exosomal miR-21in wound prognosis. A previous study demonstrated that higher miR-21 expression was related to the poor outcome of colorectal cancer patients [

26]. Moreover, miR-21 was overexpressed in nonhealing venous ulcers [

27]. Synthetic miR-21 was shown to inhibit epithelialization in a human skin organ culture wound model and to decrease granulation tissue formation in a rat model [

27]. Consistent with that notion, our study suggests that higher exosomal miR-21 is associated with poor wound healing. Together, these results demonstrate that paper-based devices are well suited for extracting tissue-derived exosomal miR-21 from wound fluids for the determination of wound status. Clinical validation of this device is, however, limited by the fact that low levels of wound exudate and complicating the wound environment may affect sample collection and the cross-section of exosomal miR-21 and substrate. Additionally, a temperature-controlled environment is a basic requirement for PCR amplification. Combining loop-mediated isothermal amplification with lateral flow assay or a field-effect transistor to examine exosomal miRNAs will allow our device to become more efficient and convenient and also increase the possibilities for clinical application. Additional investigations will be needed to confirm this hypothesis. Future study should be conducted regarding the sensitivity and specificity of exosomal miR-21 for detecting and monitoring various wound conditions. In conclusion, we establish proof-of-principle of paper-based extraction device for tissue-based exosomal miR-21 wound status detection by using clinical wound fluids from wound patients.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Patient Samples

To study miR-21 expression in wound fluids, a total of 68 tissue samples (normal: 11, acute: 36, chronic: 21) were harvested using standard surgical treatment procedures. The normal tissue samples were obtained from patients undergoing reconstructive surgery. All samples were mixed with protein extraction buffer (RIPA, Merck, Millipore) and protein inhibitor (Merck, Millipore) and centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C. Informed consent was obtained from all patients receiving the treatment, and all study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at National Cheng Kung University Hospital (No. B-ER-110-506).

4.2. Paper Modification for Exosome Isolation

To isolate exosomes from multicomponent samples, we modified the surface of Whatman cellulose paper by adding anti-CD63 to specifically bind with tetraspanin protein CD63 on the exosomal membrane via specific and high-affinity antigen-antibody interaction. Briefly, circular pieces of Whatman cellulose chromatography paper (Grade 1) with a diameter of 6 mm were prepared as test zones and incubated in 50 μL of 3-mercaptopropyl trimethoxysilane (MPTMS) solution (4% in 99% ethanol) and N-γ-maleimidobutyryloxy succinimide ester (GMBS) solution (0.01 μmol/mL in 99% ethanol) for 30 minutes and 15 minutes, respectively. The papers were then incubated in 50 μL of NeutrAvidin solution (10 μg/mL in PBS) for 60 minutes at 4°C. Afterward, 20 µL of 1% BSA (w/v) in PBS was added as a blocking solution 3 times every 10 min. Finally, 20 μL of biotinylated anti-CD63 antibody solution (20 μg/mL in PBS containing 1% (w/v) BSA) was dispensed onto the test zones 3 times every 10 min to bind with NeutrAvidin. Removing unbound molecules with three PBS washes provided us with anti-CD63-modified paper. Heterogeneous wound fluid samples (20 µL) were dispensed onto these coated papers, which were incubated for 20 min to capture exosomes by virtue of the specific antibody-antigen binding. Unwanted materials were washed off with PBS. All steps were performed at room temperature unless otherwise stated.

4.3. Paper-based Procedure for Exosomal Nucleic Acid Extraction

Once isolated, exosomes were lysed by adding 95°C ddH2O to the experimental area, whereupon the released nucleic acids were adsorbed with silica particles. Specifically, 10 μL of 95°C ddH2O was slowly added to the exosome capture zones 6 times every 5 min, followed by the addition of 20 µL of silica solution (3 mg/mL in diH2O) to allow the silica particles to absorb the released nucleic acids. The experimental papers were then rinsed 3 times with 20 μL of ddH2O to remove unwanted materials before being immersed in a tube containing 20 µL of ddH2O (an equal volume to the originally used volume of sample) and incubated at 55°C for 45 minutes for nucleic acid elution. After incubation and paper removal, the solution obtained represented the exosomal nucleic acid solution with the same concentration as the original sample.

4.4. Paper-based Procedure for Free Nucleic Acid Collection

After adding chronic wound fluid to the antibody-coated paper to capture exosomes and using PBS to wash away unbound molecules, the wash solution was collected to analyze it for free nucleic acids. A piece of paper with dimensions of 0.5 mm x 3 mm was prepared and silica particles were coated on the first third of the paper. The solution containing the obtained exosome-free nucleic acids was slowly added to the silica-coated paper. Leveraging the capillary phenomenon without the need for external force, the nucleic acids were absorbed onto the silica surface while other impurities followed the liquid flow to the rest of the paper. One-third of the paper containing nucleic acid-absorbing silica particles was cut off and dipped in 20 µL of ddH2O (an equal volume to the originally used sample volume) and incubated at 55˚°C for 45 minutes for nucleic acid elution. After incubation and paper removal, the solution obtained represented the free nucleic acid solution with the same concentration as the original sample.

4.5. RT-qPCR for Nucleic Acid Quantification

Reverse transcription and real-time PCR were used to analyze miRNA expression. These steps were performed using a Veriti™ Thermal Cycler and a StepOnePlus™ Real-Time PCR (RT-PCR) System (Applied Biosystems, USA), respectively. Experimental procedures and primer design were inspired as previously reported. (I. Balcells, S. Cirera, and P. K. J. B. b. Busk, "Specific and sensitive quantitative RT-PCR of miRNAs with DNA primers," vol. 11, no. 1, p. 70, 2011.). In the RT reaction, each 10.2 µL reaction mixture contained 1.0 µL of ATP, 1.0 µL of dNTP, 1.0 µL of 10X Poly(A) buffer, 1.0 µL of reverse transcription primer, 0.5 µL of reverse transcriptase, 0.2 µL of E.coli Poly(A) polymerase, 0.2 µL of RNAse inhibitor, 4.3 µL of nuclease-free water, and 1.0 µL of RNA sample. The reverse transcription reaction temperature flow was 60 min at 42°C, 5 min at 95°C, and incubation was at 4°C. The reverse transcription product containing synthesized cDNA was then amplified using the SYBR Green qPCR method. The 10 µL of SYBR Green qPCR mixture included 5.0 µL of SYBR Green I Master mix, 1.0 µL forward primer, 1.0 µL reverse primer, 2.0 µL nuclease-free water, and 1.0 µL of reverse transcription product. Thermocycling conditions were 5 min at 95°C for initial heat activation, and 40 cycles of 10s at 95°C and 30s at 60°C for annealing. Finally, Ct values were measured to represent the expression of target miRNA.

Universal Reverse Transcription Primer: 5’-CAGGT CCAGT TTTTT TTTTV N-3

miR-21 Forward Primer: 5’-TCAGT AGCTT ATCAG ACTGA TG-3’

miR-21 Reverse Primer: 5’-CGTCC AGTTT TTTTT TTTTT TTCAA C-3’

4.6. Statistical Analysis

Analysis of variance was used to determine statistical differences of exosomal miR-21 among normal tissue, acute, and chronic wound fluids. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The results were expressed as mean ± SD.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: S.C.P., C.M.C., W.Y.C.; Formal analysis: S.C.P., C.H.L., V.T.V., C.A.V., C.J.H.; Funding Acquisition: S.C.P., C.M.C., W.Y.C.; Investigation: C.H.L., V.T.V., C.A.V.; Supervision: S.C.P., C.M.C., C.J.H., W.Y.C.; Original Draft Preparation: S.C.P.; Writing—Review and Editing: C.M.C., W.Y.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is funded by the research grant from Taiwan’s National Science and Technology Council (111-2314-B-006-093 to S.C.P.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board at National Cheng Kung University Hospital (No. B-ER-110-506).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all patients receiving the treatment.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lindley, L.E.; Stojadinovic, O.; Pastar, I.; Tomic-Canic, M. Biology and Biomarkers for Wound Healing. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016, 138, 18S–28S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, J.; Chan, Y.C.; Sen, C.K. MicroRNAs in skin and wound healing. Physiol Genomics. 2011, 43, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Solingen, C.; Araldi, E.; Chamorro-Jorganes, A.; Fernandez-Hernando, C.; Suarez, Y. Improved repair of dermal wounds in mice lacking microRNA-155. J Cell Mol Med. 2014, 18, 1104–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herter, E.K.; Xu Landen, N. Non-Coding RNAs: New Players in Skin Wound Healing. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 2017, 6, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maacha, S.; Bhat, A.A.; Jimenez, L.; Raza, A.; Haris, M.; Uddin, S.; Grivel, J.C. Extracellular vesicles-mediated intercellular communication: roles in the tumor microenvironment and anti-cancer drug resistance. Mol Cancer. 2019, 18, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nik Mohamed Kamal, N.; Shahidan, W.N.S. Non-Exosomal and Exosomal Circulatory MicroRNAs: Which Are More Valid as Biomarkers? . Front Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, C.K.; Huang, H.Y.; Chen, W.R.; Nishie, W.; Ujiie, H.; Natsuga, K.; Fan, S.T.; Wang, H.K.; Lee, J.Y.; Tsai, W.L.; Shimizu, H.; Cheng, C.M. Paper-based ELISA for the detection of autoimmune antibodies in body fluid-the case of bullous pemphigoid. Anal Chem. 2014, 86, 4605–4610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.Y.; Yang, C.Y.; Hsu, W.H.; Lin, K.H.; Wang, C.Y.; Shen, Y.C.; Chen, Y.C.; Chau, S.F.; Tsai, H.Y.; Cheng, C.M. Monitoring the VEGF level in aqueous humor of patients with ophthalmologically relevant diseases via ultrahigh sensitive paper-based ELISA. Biomaterials. 2014, 35, 3729–3735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Pan, S.C.; Cheng, C.M. Paper-based human neutrophil elastase detection device for clinical wound monitoring. Lab Chip. 2020, 20, 2709–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melzak, K.A.; Sherwood, C.S.; Turner, R.F.B.; Haynes, C.A. Driving forces for DNA adsorption to silica in perchlorate solutions. J Colloid Interf Sci. 1996, 181, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.P.; Chen, Y.C.; Chen, W.Y. Improve sample preparation process for miRNA isolation from the culture cells by using silica fiber membrane. Sci Rep. 2020, 10, 21132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohn, W.; Kim, J.; Kang, S.H.; Yang, S.R.; Cho, J.Y.; Cho, H.C.; Shim, S.G.; Paik, Y.H. Serum exosomal microRNAs as novel biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma. Exp Mol Med. 2015, 47, e184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallo, A.; Tandon, M.; Alevizos, I.; Illei, G.G. The majority of microRNAs detectable in serum and saliva is concentrated in exosomes. PLoS One. 2012, 7, e30679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinowits, G.; Bowden, M.; Flores, L.M.; Verselis, S.; Vergara, V.; Jo, V.Y.; Chau, N.; Lorch, J.; Hammerman, P.S.; Thomas, T.; Goguen, L.A.; Annino, D.; Schoenfeld, J.D.; Margalit, D.N.; Tishler, R.B.; Haddad, R.I. Comparative Analysis of MicroRNA Expression among Benign and Malignant Tongue Tissue and Plasma of Patients with Tongue Cancer. Front Oncol. 2017, 7, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rani, A.; O'Shea, A.; Ianov, L.; Cohen, R.A.; Woods, A.J.; Foster, T.C. miRNA in Circulating Microvesicles as Biomarkers for Age-Related Cognitive Decline. Front Aging Neurosci. 2017, 9, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribas, J.; Ni, X.; Castanares, M.; Liu, M.M.; Esopi, D.; Yegnasubramanian, S.; Rodriguez, R.; Mendell, J.T.; Lupold, S.E. A novel source for miR-21 expression through the alternative polyadenylation of VMP1 gene transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 6821–6833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhang, C. MicroRNA-21 in cardiovascular disease. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2010, 3, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Wu, W.; Zheng, L.; Lin, X.; Tai, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L. Roles of MicroRNA-21 in Skin Wound Healing: A Comprehensive Review. Front Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 828627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzywinska, O.; Bracha, M.; Jeanniere, C.; Recchia, E.; Kornatowska, K.K.; Kozakiewicz, M. Meta-Analysis of the Potential Role of miRNA-21 in Cardiovascular System Function Monitoring. Biomed Res Int, 2020, 2020, 4525410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalighfard, S.; Alizadeh, A.M.; Irani, S.; Omranipour, R. Plasma miR-21, miR-155, miR-10b, and Let-7a as the potential biomarkers for the monitoring of breast cancer patients. Sci Rep. 2018, 8, 17981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Hou, L.; Li, A.; Duan, Y.; Gao, H.; Song, X. Expression of serum exosomal microRNA-21 in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Biomed Res Int. 2014, 2014, 864894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, J.A.; Baxter, D.H.; Zhang, S.; Huang, D.Y.; Huang, K.H.; Lee, M.J.; Galas, D.J.; Wang, K. The microRNA spectrum in 12 body fluids. Clin Chem. 2010, 56, 1733–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soliman, A.M.; Das, S.; Abd Ghafar, N.; Teoh, S.L. Role of MicroRNA in Proliferation Phase of Wound Healing. Front Genet. 2018, 9, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ning, M.S.; Andl, T. Control by a hair's breadth: the role of microRNAs in the skin. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013, 70, 1149–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Feng, Y.; Sun, H.; Zhang, L.; Hao, L.; Shi, C.; Wang, J.; Li, R.; Ran, X.; Su, Y.; Zou, Z. MiR-21 regulates skin wound healing by targeting multiple aspects of the healing process. Am J Pathol. 2012, 181, 1911–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schetter, A.J.; Leung, S.Y.; Sohn, J.J.; Zanetti, K.A.; Bowman, E.D.; Yanaihara, N.; Yuen, S.T.; Chan, T.L.; Kwong, D.L.; Au, G.K.; Liu, C.G.; Calin, G.A.; Croce, C.M.; Harris, C.C. MicroRNA expression profiles associated with prognosis and therapeutic outcome in colon adenocarcinoma. JAMA. 2008, 299, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastar, I.; Khan, A.A.; Stojadinovic, O.; Lebrun, E.A.; Medina, M.C.; Brem, H.; Kirsner, R.S.; Jimenez, J.J.; Leslie, C.; Tomic-Canic, M. Induction of specific microRNAs inhibits cutaneous wound healing. J Biol Chem. 2012, 287, 29324–29335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).