1. Introduction

The fungal cell wall is a complex and well-ordered structure composed of a backbone of polysaccharides, including chitin/chitosan and α/ β-glucans, (galacto)-mannans, and glycosylated proteins. Most fungi have a common alkali-insoluble inner wall layer of branched β-(1,3) glucan, β-(1,6) glucan, and chitin but differ substantially in the components in outer layers that are more heterogeneous and tailored to the physiology of particular fungi. The branched β-(1,3):β-(1,6) glucan is bound to proteins and/or other polysaccharides, whose composition may vary with the fungal species [

1].

Chitin is one of the most common polysaccharides in nature, found in the majority of fungi, as well as many insects and invertebrates [

2]. Chitin makes up about 1–15% of the fungal cell mass with a higher concentration in the cell walls [

3,

4]. The cell walls and septa of many fungi belonging to the Basidiomycota, Ascomycota, Zygomycota, and Deuteromycota contain chitin to support the strength, shape, and integrity of cell structure. The amount of chitin in the fungal cell wall is specific to species, environmental conditions, and age [

5].

Chitosan is less frequent in nature occurring in some fungi (Mucoraceae). Chitosan is produced by deacetylation of chitin; in this process, some N-acetylglucosamine moieties are converted into glucosamine units [

6]. Commercial chitosan is mainly produced from chemical deacetylation of chitin from crustacean sources. More recently, chitosan from fungi is gaining interest in the market driven by vegan demands [

7].

Chitin and chitosan have many desirable properties such as non-toxicity, biodegradability, bioactivity, biocompatibility and good adsorption properties which make them suitable alternatives to synthetic polymers [

3]. These biopolymers have a large number of potential agricultural, environmental and biomedical applications [

4,

7,

8]. The global chitosan market size was valued at USD 6.8 billion in 2019, and is expected to expand in future. The market growth is influenced by increasing application of the polymer in water treatment and high-value industries such as the pharmaceutical, biomedical, cosmetics and food [

7].

Major advantages of chitin and chitosan production from fungal mycelia over crustacean sources include simpler extraction process, low levels of inorganic materials, not required demineralization, availability with no seasonal or geographic limitations, consistent physico-chemical properties, and low cost of waste management [

3]. In this regard, the present work was intended to extract the biopolymers from selected species of Basidiomycota with different environmental distribution, ecological importance, and industrial application. More specifically,

Heterobasidion annosum is the most economically important forest pathogen in the northern hemisphere causing the root rot in softwoods [

9].

Phanerochaete chrysosporium is the model white rot (WR) fungus for lignin degradation, and is studied for potential application in bioethanol production [

10], food industry [

11], pulp and paper industry [

12], bioremediation and biosorption [

13,

14].

Pleurotus ostreatus is very important, widely cultivated edible mushroom [

15], also studied for the enzymatic application in pulp and paper industry [

16].

Trametes versicolor is used in traditional medicine and has shown effect in cancer therapy, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, antimalarial, diabetic, and hepatitis treatment [

15,

17].

Lentinus lepideus is an edible mushroom, cultivated for nutritional and medicinal purposes, including anti-tumor and immunomodulatory activities [

18] and bioethanol production [

19].

Agaricus bisporus is one of the most cultivated edible mushrooms in the world [

15], with remarkable nutritional, medicinal, and cosmetic values of bioactive compounds [

20]. The WR fungus

Ganoderma applanatum has phytochemical properties with potential application in nanotechological engineering for clinical use [

21].

The aim of this study was to obtain the mycelial biomass from fungi H. annosum, P. chrysosporium, P. ostreatus, T. versicolor and L. lepideus in two types of cultivation systems (solid and submerged), followed by chitosan extraction, and the biopolymer analyses with elemental and instrumental methods. The fruiting bodies of P. ostreatus, A. bisporus and G. applanatum were used as a reference material of chitosan content in basidiocarps.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fungal material

For determination of mycelial biomass and chitosan yield, the following strains of basidiomycetes were selected: H. annosum S.S. V str 28 was provided by the Latvian State Forest Research Institute "Silava", P. chrysosporium LMKK 407 and P. ostreatus LMKK 685 were purchased from the Microbial Strain Collection of Latvia (MSCL), T. versicolor CTB 863 A and L. lepideus BAM 114 were purchased from the Federal Institute for Materials Research and Testing (BAM, Berlin). To compare the chitosan yield in mycelial biomass and fungal fruiting bodies, the basidiocarps of commercial mushrooms P. ostreatus and A. bisporus were purchased from a local grocery, and wood destroying fungus G. applanatum was collected from a forest ecosystem.

2.2. Inoculum preparation

The fungal strains were maintained on malt extract agar (MEA) slants at 6oC. For inoculum preparation, the mycelium plugs were aseptically transferred to the Petri dishes with MEA medium containing 5% malt extract concentrate, 3% agar (pH 6.0) and cultivated for 14 days in cultivation chamber at temperature 21±2oC and relative humidity (RH) 70±5%.

2.3. Biomass cultivation

Two types of fermentation systems were applied: solid-state fermentation (SSF) and submerged fermentation (SF), both of which can be used for biomass production and chitosan isolation.

Initially, the study of mycelium growth dynamics was conducted in SF. 250 mL Erlenmeyer flasks were filled with 100 mL nutrient medium containing (g/L distilled water): glucose – 15.0; peptone – 3.0; yeast extract – 3.0; NaH2PO4 – 0.8; K2HPO4 – 0.4; MgSO4 – 0.5, pH 6.0. Sterilized flasks were inoculated with the 1 cm2 mycelium discs and cultivated for 7, 14, 21, 28 and 35 days in rotary shaker incubator (Infors, Switzerland) at 28±1oC/ 150 rpm.

After the growth dynamics experiments, the SSF and SF were applied to produce fungal biomass within a period of 14 days for isolation of chitosan biopolymer. For SSF, the Petri dishes containing sterile MEA medium (as previously mentioned), were inoculated with the 1 cm2 mycelium discs and cultivated in controlled conditions at 21±2oC/ 70±5 RH. For SF, the medium and inoculation procedure was identical as described previously. The biomass was cultivated both in stationary culture and shaken culture. After cultivation, the dry weight biomass was quantified by filtered through the synthetic fabric filter, washed twice with 100 mL deionized water and dried in oven at 70oC until a constant weight. Biomass concentration from filtration was expressed in grams of dry weight per 100 mL medium.

2.4. Chitosan extraction

Chitosan from (a) mycelial biomass, obtained after 14 days of cultivation in SSF and shaken SF, as well as from (b) fungal fruiting bodies was extracted by the chemical method in a two-step procedure. In Step I, dried fungal biomass was pulverized and subjected to alkaline treatment with 1M NaOH in the ratio 1:20 (v/v) at 90°C for 3 h to remove proteins, glycoproteins and branched polysaccharides.

After treatment, the sample was washed with deionized water until a neutral reaction and filtered. Obtained alkali-insoluble (AIS) material was washed with ethanol, acetone and dried at 100°C. Then the sample was heated at 90°C for 3 h in 2% acetic acid (1:40 (m/m)). Acid insoluble (AIS/Acid IS) part or chitin-containing part was washed with water, filtered and washed with ethanol and acetone, and dried. Acid soluble part or glucans were sedimented from the filtrate by changing the acid pH to 9 with NaOH. Sediments were collected on a glass filter, washed with ethanol and acetone, and dried at 100°C.

In Step II deacetylation was implemented. The dried Acid IS part or chitin-containing part was subjected to alkaline treatment with 10M (40%) NaOH in the ratio 1:20 (v/v) at 90°C for 3 h. After treatment, the sample was washed with deionized water until a neutral reaction and filtered. Obtained alkali-insoluble (40% AIS) material was washed with ethanol and acetone, and dried at 100°C. Then the sample was heated at 90°C for 3 h in 2% acetic acid (1:40 (m/m)). Acid insoluble (40% AIS/Acid IS) part was washed with water, filtered and dried. Acid soluble part or chitosan was sediment from the filtrate by changing the acid pH to 9 with NaOH. Sediments were collected on the glass filter, washed with ethanol and acetone, and dried at 100°C. The yield of each stage was determined gravimetrically. Moisture content of air dry fungal material was determined according to ISO 18134-32015.

2.5. Nitrogen content

Nitrogen elemental analysis was determined according to the CEN/TS 15104: 2011. Homogenized samples (30 mg) were packed in a tin foil, weighed, placed into the carousel of an automatic sample feeder and analyzed with an Elementar Analysensysteme GmbH (Germany) Vario MACRO CHNS with a combustion tube temperature of 1150°C. The original matrix of the sample was destroyed under these conditions through subsequent catalytic reactions.

2.6. Fourier transform infrared spectrometry (FTIR)

The milled sample (2 mg) was mixed with 198 mg KBr powder (IR 145 grade, Sigma Aldrich) and pressed into a small tablet. FTIR spectra were recorded by Nicolet iS50 spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) in the range of 4000–450 cm−1 (resolution: 4 cm−1, 32 scans per sample).

2.7. Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was conducted using RStudio version 4.2.2. Pearson correlation (function: cor.test) was used to explore the relationships between different variables. All statistical tests were conducted at a significance level of α=0.05, meaning that a p-value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant and would lead to rejection of the null hypothesis.

3. Results

3.1. Growth dynamics

The screening of fungal strains at equal cultivation conditions (temperature; rpm) in SF was performed to observe the differences in biomass concentration versus duration of incubation with the aim to select the optimal period for collection of biomass for chitosan extraction. The hypothesis was that the higher biomass yield will give a higher chitosan yield.

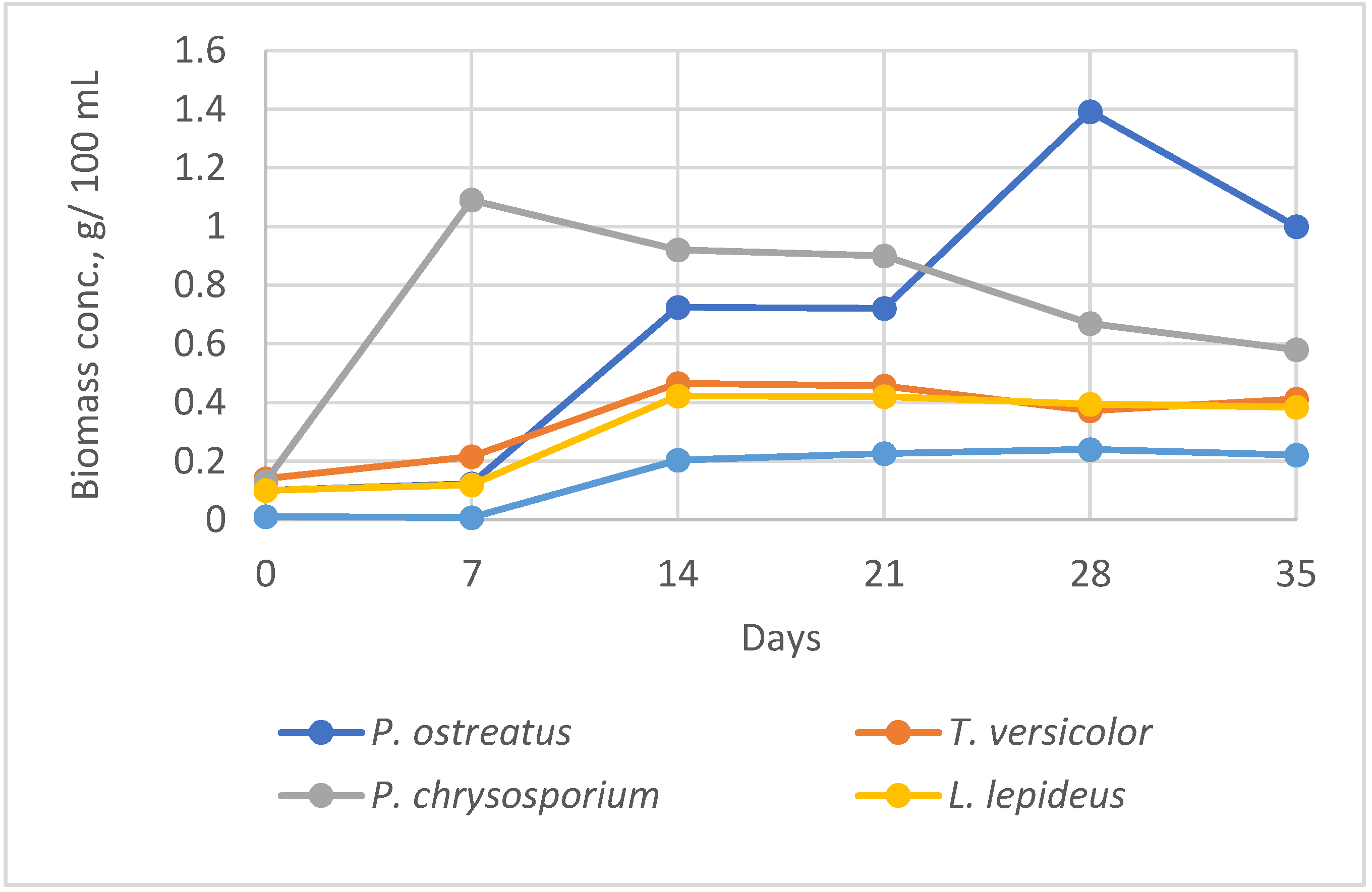

The maximum biomass yield in liquid SF within 7-35 days varied depending on the fungal strain and duration of cultivation (

Figure 1). The highest biomass concentration (1.39 g 100 mL

–1) was achieved by

P. ostreatus after longer cultivation of 28 days. High biomass yield (1.09 g 100 mL

–1) in the shortest cultivation time of 7 days was obtained from

P. chrysosporium. Fungi

L. lepideus and

T. versicolor accumulated lower biomass amount in the range of 0.4-0.5 g 100 mL

–1.

The lowest mycelial growth and biomass concentration at the given cultivation conditions performed

H. annosum (0.2 g 100 mL

–1). The fungus had very low adaptation to the physical and chemical growth conditions. After 7 days cultivation of

H. annosum the fungal growth still was not observed, followed by limited growth until 14 days. In the next cultivation periods, the growth a reached plateau and biomass remained at relatively constant level. Similar tendency with a maximum specific growth rate until 14 days was observed in

L. lepideus and

T. versicolor cultures. Contrary,

P. chrysosporium reached the maximum growth rate within the first 7 days, with the following gradual decline of biomass production. However, after 14 days, the fungus had the highest biomass concentration among the other strains at the given period. The highest biomass yield by

P. ostreatus was collected after long incubation and cannot be considered as economically effective for further experiments. Similar results were obtained by screening more than 50 Basidiomycetes where the majority of species produced higher biomass yield after 14 days than 7 days of incubation [

22].

Based on the growth dynamics observations, 14 days period was chosen for the further SSF and SF methods as the most appropriate period in relation to fungus: yield: duration.

3.2. Biomass concentration

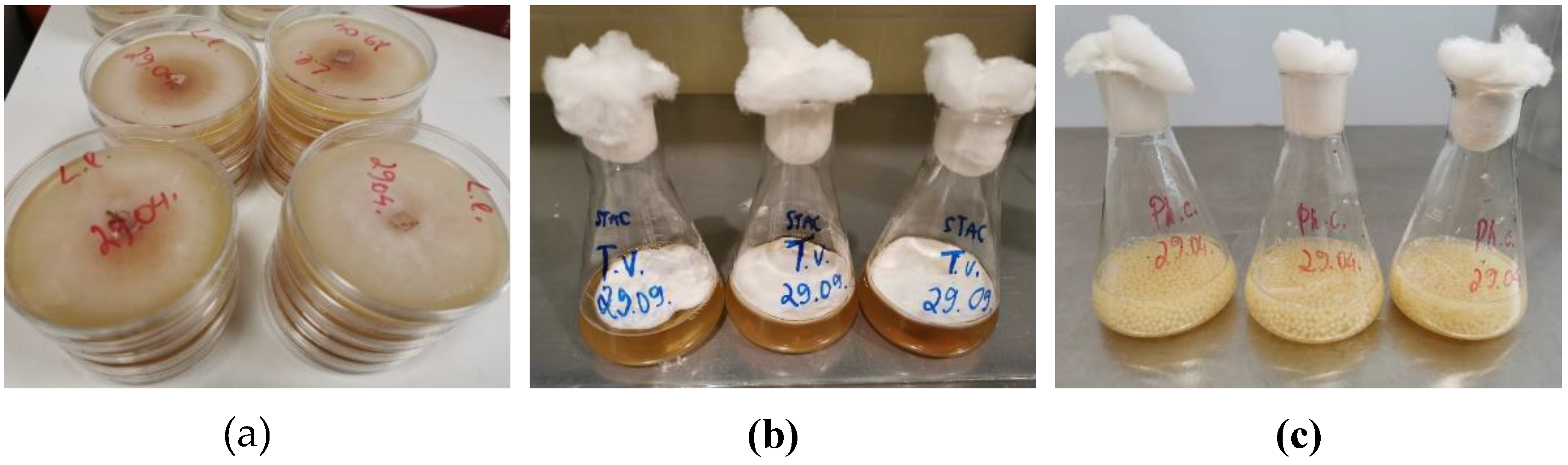

It was observed that mycelium of all tested strains in solid culture radially expanded and formed a typical aerial mycelium above the substrate (

Figure 2a), in static liquid culture the fungi grew as floating pellicles (

Figure 2b), and in agitated liquid culture the spherical pellets of aggregated mycelia were formed (

Figure 2c). Different mycelial growth forms locally experience different micro-environmental conditions, which affect fungal physiology and hence fermentation processes [

23]. The hyphal branching allows filamentous fungi to fill space in an efficient and appropriate way according to local environmental circumstances. Dense mycelium is produced in nutrient-rich substrata for resource exploitation, whereas hyphae colonizing nutrient-poor substrate branch less frequently, producing effuse mycelia [

23].

Stationary cultivation in the liquid medium gave the lowest biomass yield in comparison with solid and liquid shaken cultures (

Table 1). The exception was

H. annosum producing the lowest biomass amount in shaken SF. The role of aeration and agitation in biomass production was clearly observed in shaken SF. The shaken SF was most favorable for

P. chrysosporium giving the highest yield of 1.03 g 100 mL

–1 among other strains. The highest biomass yield in SSF produced

P. ostreatus and

T. versicolor, 3.04 g 100 mL

–1 and 3.65 g 100 mL

–1, respectively. The biomass of these strains exceeding the yield in the shaken culture around five to seven times. The pH after fermentation laid between 3.7 - 5.7 depending on the fungal strain, and cultivation method used, with lower values in SSF. The optimal initial pH is from 3.0 to 9.0 for mycelial growth, and depends on the fungal species, strains of the same fungus, and also include some other cultivation conditions like culture medium [

24].

The process of microbial pellet formation and mycelial cell aggregation is influenced by many factors, including the strain used, growth rate, medium composition, shear force, aeration, agitation, and many others. These factors can be divided into three main categories: strain dependent factors, nutrition dependent factors and cultivation conditions [

25].

In our experiments, the medium and cultivation conditions were equal for all tested fungi. The differences in biomass yield were determined by the strain specific factors and duration of cultivation (

Figure 1). The combination: SSF/ nutrition MEA / temperature 21

oC was more favorable for most tested strains than combination: SF/ synthetic medium/ temperature 28

oC. Earlier study [

26] showed that optimum culture conditions for

P. chrysosporium strain were pH 7, temperature 37°C and incubation time of 15 days to obtain the maximum yield of the biomass in stationary liquid medium. Experiments with

P. ostreatus indicated that the optimal temperature for mycelium growth was at 28

oC [

27]. The temperature factor can be related to the process of assimilation and translocation of sugar and nitrogen, respiration, and biosynthesis. Most of the fungi are characterized by a preference for a definite temperature regime with subsequent growth enhancement, however some of them may have the same level of mycelial growth at different temperatures [

24].

The effect of cultivation conditions such as temperature, oxygen supply, etc. as well as medium components such as the C source, N source, C/N ratio, complex organic materials are reflected in the specific growth rate of the microorganisms [

25]. Many microorganisms have strict requirements for certain mineral elements, among them K, P, Mg, Ca, Mo, Fe, Cu and Zn [

28]. In our study, among the applied cultivation methods and fungal strains, the SSF provided the highest biomass yield (1.85-3.65 g 100 mL

–1) in 14 days period. Also the study by Crestini et al. (1996) [

29] showed that SSF was more efficient in fungal biomass production than SF. The authors reported that SSF of the fungus

Lentinus edodes yielded a greater biomass concentration (up to 50 times) after 12 days of incubation, than that of SF. In our opinion, SSF method was more time and labor consuming in the final biomass collecting phase than SF. These conditions pushed toward the use of SF instead of SSF for biomass production and following chitosan isolation.

3.3. Chitin content and chitosan yield

Table 2 shows the results of chitosan isolation steps – deproteinization fraction (AIS), chitin-containing fraction (AIS/Acid IS), acid soluble part or beta-glucans, alkali insoluble (40% AIS) part, acid insoluble (40% AIS/Acid IS) part and chitosan after deacetylation. The content of chitin, glucans and chitosan within the fungal strains varied depending on the cultivation method. The chitin-containing part in fungal cell walls comprised 9% to 27% with the highest amount in

T. versicolor cells. In

T. versicolor culture, it was observed that chitin content depended on the cultivation method with 50% higher content in SSF than SF. Within the other strains there was not a distinct difference found between both cultivation methods regarding chitin content.

Comparing the yield of extracted glucans and chitosan in fungal hyphae, the cultivation in SF resulted in a higher yield of both biopolymers. Glucans at higher amounts of 0.54% and 0.82% were extracted from

P. chrysosporium and

P. ostreatus mycelium, respectively. The highest yield of chitosan was obtained from the mycelium of

P. chrysosporium (0.38%) and

T. versicolor (0.37%). The cell walls of filamentous fungi are mainly composed of different polysaccharides according to the taxonomic group. They may contain chitin, glucans, mannoproteins, chitosan, polyglucuronic acid, together with smaller quantities of proteins and glycoproteins. Basidiomycota contains fibrillar polymers chitin and β (1,3)-β (1,6) glucans while Zygomycota is reported to contain chitin and chitosan polymers in the cell wall [

23]. However, further studies have proved that chitosan is also present in Ascomycota and Basidiomycota species. In Basidiomycota, it has been described in

Lentinus edodes and

Pleurotus sajo-caju [

30].

Chitosan from the fruiting bodies of

P. ostreatus and

G. applanatum was obtained at a considerably lower amount than that from

A. bisporus. Thus,

A. bisporus with 1.7% chitosan yield was the most efficient source of biopolymer among the species under this study. If comparing chitosan yield in the mycelium and fruiting body within the species level, a three times higher chitosan amount was obtained from

P. ostreatus mycelium in SF than from the fruiting body. Chitosan from

P. ostreatus mycelium in SSF and the fruiting body was extracted in similar quantities (

Table 2). This observation gave evidence that chitosan yield depended on the fungal development stage (mycelium/ fruiting body), even more, between the cultivation methods. The quantity and/or quality of chitin and chitosan in the fungal cell wall may change due to environmental and nutritional conditions and the intrinsic characteristics of producing species [

30].

Statistically significant correlation between biomass yield and chitosan yield among the tested fungi was not found as p value was above the significance level (0.42). For example, the highest biomass yield of

P. ostreatus and

T. versicolor in SSF (

Table 1) resulted in a low chitosan yield in this fermentation system (

Table 2). Similarly, no relation between biomass and exopolysaccharide production and in some cases a considerable decrease of biopolymer was observed for screened Basidiomycetes after 14 days of incubation [

22]. Fungi are usually harvested at their late exponential growth phase to obtain the maximum yield for chitin and chitosan [

28]. In this regard, our experiments were conducted to screen the specific Basidiomycetes regarding biomass yield in 14 days period of incubation and its relation to chitosan production.

3.4. Nitrogen content in fungal material

Nitrogen was determined to identify and characterize the isolated biopolymers. In

Table 3, the results of nitrogen content in raw material, after deproteinization (AIS), in chitin-containing (AIS/Acid IS), glucan and chitosan fractions are presented. The raw material contained nitrogen from different biopolymers found in fungal cells such as proteins, glucoproteins, and chitin. Nitrogen is structurally and functionally linked with fungal cellular functions as organic amino nitrogen in proteins and enzymes [

23]. The highest total nitrogen was found in the mycelium of

H. annosum, T. versicolor and

L. lepideus in liquid cultures reaching more than 6%. These strains in solid cultures contained 2 to 3 times lower amount of nitrogen.

After protein removal the nitrogen remained in structural components of cell wall including chitin. The nitrogen in chitin containing fraction depended on the cultivation method with a higher content in liquid medium. In fruiting bodies the highest nitrogen percentage in chitin containing fraction was determined for

A. bisporus. Smalls amounts (0.14 - 0.54%) of nitrogen were found in glucan fraction of the mycelial biomass and fruiting bodies. This can be explained by the small amount of chitin released together with glucans in the form of chitin-glucan complexes [

31].

The nitrogen in isolated chitosan comprised over 6% both in the mycelium and fruiting bodies depending on the fungal species. This is close to the actual nitrogen content of chitosan (6.6-8.2%) reported in the literature [

32]. Alvarenga (2011) [

33] found that the percentage of nitrogen in fully deacetylated chitosan was 8.695, and in fully acetylated chitin - 6.896. In our study, the nitrogen content in the chitosan fraction was lower than in pure chitosan, because a small amount of chitin-glucan, chitosan-glucan complexes remains in the chitosan fraction [

34]. In order to completely break down the chitin-glucan complexes, it is necessary to use enzymatic treatment [

35]. The highest nitrogen content was determined in fungal samples containing the highest chitosan yield i.e. mycelium of

P. chrysosporium and

T. versicolor, and the fruiting body of

A. bisporus (

Table 2).

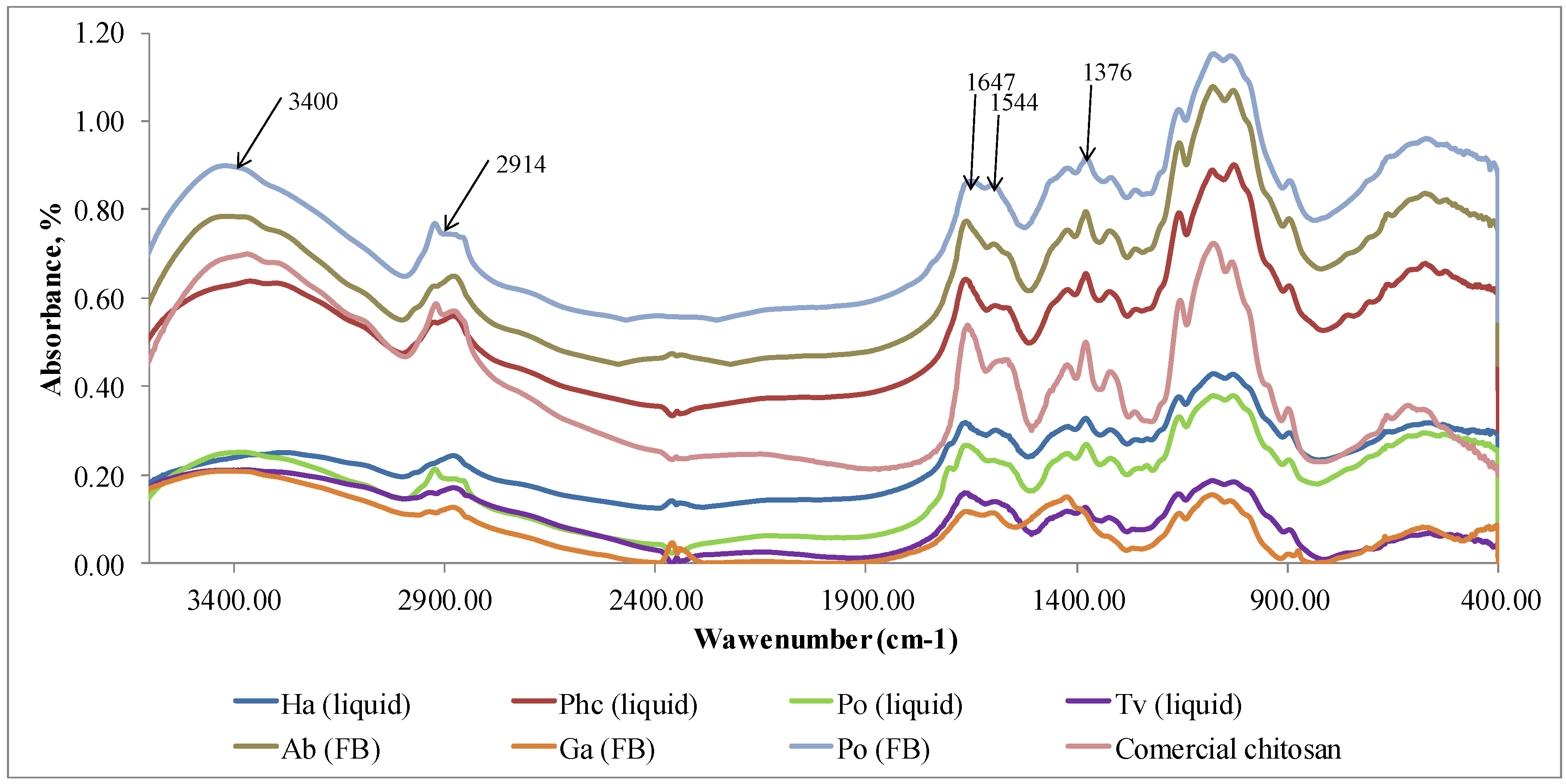

3.5. Fourier transform infrared spectra

FTIR method was used to identify the eluted chitosan samples and compare them with a commercial chitosan (Sigma Aldrich). Characteristic peaks for the identification of chitosan at 1376 cm

-1 corresponds to the amide III, 1544 cm

-1 is connected with doubling group NH2, 1647 cm

-1 indicates amide I, 2914 cm

-1 shows stretching band C–H and –C=O of the amide group CONH–R of the polymers [

32], 3400 cm

-1 indicates the presence of -OH stretching and amine N-H symmetric vibrations [

36].

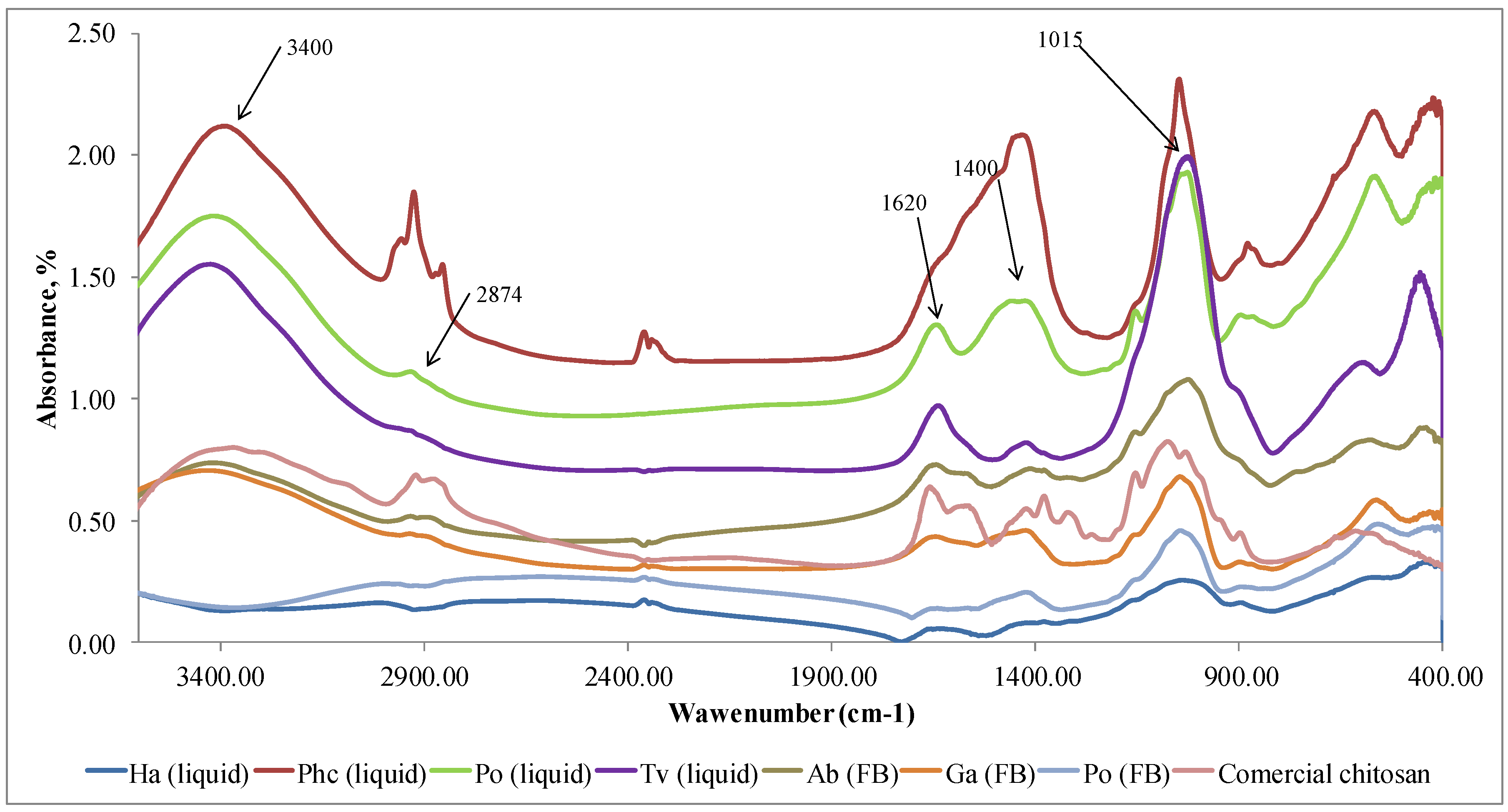

The results confirmed (

Figure 3) that polymer samples isolated from fungi in Step I did not have the characteristic FTIR peaks of chitosan but the peaks of other polysaccharides. Characteristic FTIR spectra of polysaccharides in the region of 3300-3500 cm

−1 indicates the stretching vibrations of OH groups. The peak at 2874 cm

−1 corresponds to the stretching vibrations of the C–H groups and 1662 cm

−1 connected with deformational vibrations of OH-groups of bound water. The FTIR peaks in the region of 1400-1500 cm

−1 show CH

2 bending. The FTIR bands in the range of 1500–1200 cm

−1 are sensitive to chemical and molecule structural transformations. The region of 1000–1200 cm

−1 is connected with stretching C–O–C and C–O vibrations [

37,

38]. It can be concluded that in Step I, glucans [

39,

40] together with other compounds, were released from mycelium and fruiting bodies. FTIR method is sensitive to the position and anomeric configuration of glycosidic linkages in glucans. Fruiting bodies of mushrooms contain two main types of glucans: branched (1→3) (1→6)-β-D-glucan and linear (1→3)-α-D-glucan [

41].

The FTIR spectra of extracted chitosan coincided with the spectrum of commercially produced chitosan (

Figure 4). All peaks identifying chitosan are visible in the FTIR spectra. Similar result was obtained in research by Ospina et al. (2015) [

42] where chitosan was isolated from the

Ganoderma lucidum basidiomycete through the deacetylation of chitin. The FTIR spectra of chitosan obtained from this mushroom had a significant similitude with commercial chitosan.

Based on our results (

Table 2) chitosan isolation method is applicable to obtain a pure biopolymer (

Figure 4) from fungal material with the highest amount extracted from cultivated mycelium of

P. chrysosporium and fruiting body of mushroom

A. bisporus. Despite the presence of hydrophilic amine and-OH groups, films of chitosan exhibit hydrophobic character [

43]. The solubilized chitosan films can be considered for food-contact purposes[

44,

45] as they can resist wetting by water. The chitosan as a functional biopolymer additive is suggested as a substitute of synthetic wet and dry strength agents in packaging materials.

4. Conclusions

The screening of fungi in SF indicated that the maximum biomass concentration within the period of 7-35 days depended on the fungal strain and duration of cultivation. 14 days cultivation proved to be the most appropriate duration in relation to fungal strain: yield. Based on the applied cultivation methods and fungal strains, SSF provided a higher biomass yield than SF.

With the selected two-step chemical extraction method, it was possible to isolate chitosan from cultured fungal mycelia as well as from collected fruiting bodies. In Step I glucans were separated to produce chitosan with fewer impurities in Step II. The content of chitin/ chitosan within fungal species varied depending on the method of cultivation. There was not found a statistically significant correlation between biomass and chitosan yield among the tested fungi. The highest chitosan yield among the cultivated strains was obtained from mycelium of P. chrysosporium and T. versicolor in SF. Thus, these strains have potential application in biotechnological processes for chitosan production. The highest chitosan amount in fungal fruiting bodies showed commercially cultivated mushroom A. bisporus. Consequently, the remains (stalks) of A. bisporus food production have potential use as a raw material in chitosan isolation. The extracted chitosan as a functional biopolymer additive could substitute synthetic wet and dry strength agents in packaging materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.I. and L.A.; methodology, I.I., L.A. and I.F.; formal analysis, M.B., A.V. and J.Z.; investigation, M.B., A.V. and J.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, I.I.; writing—review and editing, L.A.; project administration, I.F.; funding acquisition, I.F. and L.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Regional Development Fund Contract No.1.1.1.1/20/A/113 “Development of ecological and biodegradable materials from natural fibres with functional biopolymer additives”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gow Neil, A.R.; Latge, J.-P.; Munro Carol, A. The Fungal Cell Wall: Structure, Biosynthesis, and Function. Microbiology Spectrum 2017, 5, 5.3.01. https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.FUNK-0035-2016. [CrossRef]

- Zabel, R.M., J. Wood Microbiology. Decay and Its Prevention, Academic Press, 2020; pp. 576.

- Abo Elsoud, M.M.; El Kady, E.M. Current trends in fungal biosynthesis of chitin and chitosan. Bulletin of the National Research Centre 2019, 43, 59. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42269-019-0105-y. [CrossRef]

- Brown, H.E.; Esher, S.K.; Alspaugh, J.A. Chitin: A “Hidden Figure” in the Fungal Cell Wall. In The Fungal Cell Wall : An Armour and a Weapon for Human Fungal Pathogens, Latgé, J.-P., Ed. Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; https://doi.org/10.1007/82_2019_184pp. 83-111. [CrossRef]

- Kirk PM, C.P., Minter DW, Stalpers JA (eds) (2008) Dictionary of the Fungi,; 10th edn. CAB International, W.

- Pellis, A.; Guebitz, G.M.; Nyanhongo, G.S. Chitosan: Sources, Processing and Modification Techniques. Gels 2022, 8, 393. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels8070393. [CrossRef]

- Aranaz, I.; Alcántara, A.R.; Civera, M.C.; Arias, C.; Elorza, B.; Heras Caballero, A.; Acosta, N. Chitosan: An Overview of Its Properties and Applications. In Polymers, 2021; Vol. 13. [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Upadhyay, S.K.; Singh, M.; Sharma, I.; Sharma, P.; Pooja; Kamboj; Saini, A.K.; Voraha, R.; Sharma, A., et al. Chitin, Chitinases and Chitin Derivatives in Biopharmaceutical, Agricultural and Environmental Perspective. Biointerface Research in Applied Chemistry 2020.

- Gaitnieks, T.; Bruna, L.; Zaluma, A.; Burnevica, N.; Klavina, D.; Legzdina, L.; Jansons, J.; Piri, T. Development of Heterobasidion spp. fruit bodies on decayed Piecea abies. Forest Ecology and Management 2021, 482, 118835. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2020.118835. [CrossRef]

- García-Torreiro, M.; López-Abelairas, M.; Lu-Chau, T.A.; Lema, J.M. Fungal pretreatment of agricultural residues for bioethanol production. Industrial Crops and Products 2016, 89, 486-492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2016.05.036. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhary, P.; More, N.; Yadav, A.; Bharagava, R.N. Chapter 12 - Ligninolytic Enzymes: An Introduction and Applications in the Food Industry. In Enzymes in Food Biotechnology, Kuddus, M., Ed. Academic Press: 2019; https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-813280-7.00012-8pp. 181-195. [CrossRef]

- Mittar, D.; Khanna, P.K.; Marwaha, S.S.; Kennedy, J.F. Biobleaching of Pulp and Paper Mill Effluents by Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Journal of Chemical Technology & Biotechnology 1992, 53, 81-92. https://doi.org/10.1002/jctb.280530112. [CrossRef]

- Fulekar, M.H.; Pathak, B.; Fulekar, J.; Godambe, T. Bioremediation of Organic Pollutants Using Phanerochaete chrysosporium. In Fungi as Bioremediators, Goltapeh, E.M., Danesh, Y.R., Varma, A., Eds. Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2013; https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-33811-3_6pp. 135-157. [CrossRef]

- de Mattos-Shipley, K.M.J.; Ford, K.L.; Alberti, F.; Banks, A.M.; Bailey, A.M.; Foster, G.D. The good, the bad and the tasty: The many roles of mushrooms. Studies in Mycology 2016, 85, 125-157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.simyco.2016.11.002. [CrossRef]

- Hyde, K.D.; Xu, J.; Rapior, S.; Jeewon, R.; Lumyong, S.; Niego, A.G.T.; Abeywickrama, P.D.; Aluthmuhandiram, J.V.S.; Brahamanage, R.S.; Brooks, S., et al. The amazing potential of fungi: 50 ways we can exploit fungi industrially. Fungal Diversity 2019, 97, 1-136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13225-019-00430-9. [CrossRef]

- Skočaj, M.; Gregori, A.; Grundner, M.; Sepčić, K.; Sežun, M. Hydrolytic and oxidative enzyme production through cultivation of Pleurotus ostreatus on pulp and paper industry wastes. 2018, 72, 813-817, https://doi.org/10.1515/hf-2017-0179. [CrossRef]

- Habtemariam, S. Trametes versicolor (Synn. Coriolus versicolor) Polysaccharides in Cancer Therapy: Targets and Efficacy. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines8050135. [CrossRef]

- Doskocil, I.; Havlik, J.; Verlotta, R.; Tauchen, J.; Vesela, L.; Macakova, K.; Opletal, L.; Kokoska, L.; Rada, V. In vitro immunomodulatory activity, cytotoxicity and chemistry of some central European polypores. Pharmaceutical Biology 2016, 54, 2369-2376. https://doi.org/10.3109/13880209.2016.1156708. [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, K.; Kanawaku, R.; Masumoto, M.; Yanase, H. Efficient xylose fermentation by the brown rot fungus Neolentinus lepideus. Enzyme and Microbial Technology 2012, 50, 96-100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enzmictec.2011.10.002. [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Murtaza, G.; Ditta, A. Nutritional, Medicinal, and Cosmetic Value of Bioactive Compounds in Button Mushroom (Agaricus bisporus): A Review. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 5943. [CrossRef]

- Manasseh, A.T.; Godwin, J.T.A.; Emanghe, E.U.; Borisde, O.O. Phytochemical properties of Ganoderma applanatum as potential agents in the application of nanotechnology in modern day medical practice. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine 2012, 2, S580-S583. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2221-1691(12)60277-9. [CrossRef]

- Maziero, R.; Cavazzoni, V.; Bononi, V.L.R. Screening of basidiomycetes for the production of exopolysaccharide and biomass in submerged culture. Revista de Microbiologia 1999, 30.

- Walker, G.M.; White, N.A. Introduction to Fungal Physiology. In Fungi, 2017; https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119374312.ch1pp. 1-35. [CrossRef]

- Krupodorova T.A., B.V.Y., Sekan A.S.S (2021) Review of the basic cultivation conditions influence on the growth of basidiomycetes.Current Research in Environmental & Applied Mycology (Journal of Fungal Biology) 11(1), 494–531.

- El-Enshasy, H.A. Chapter 9 - Filamentous Fungal Cultures – Process Characteristics, Products, and Applications. In Bioprocessing for Value-Added Products from Renewable Resources, Yang, S.-T., Ed. Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2007; https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-044452114-9/50010-4pp. 225-261. [CrossRef]

- Khamrai, M.; Banerjee, S.L.; Kundu, P.P. A sustainable production method of mycelium biomass using an isolated fungal strain Phanerochaete chrysosporium (accession no: KY593186): Its exploitation in wound healing patch formation. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology 2018, 16, 548-557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcab.2018.09.013. [CrossRef]

- Hoa, H.T.; Wang, C.L. The Effects of Temperature and Nutritional Conditions on Mycelium Growth of Two Oyster Mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus and Pleurotus cystidiosus). Mycobiology 2015, 43, 14-23. https://doi.org/10.5941/myco.2015.43.1.14. [CrossRef]

- Akila, R.M. Fermentative production of fungal Chitosan, a versatile biopolymer(perspectives and its applications). Advances in Applied Science Research 2014, 5.

- Crestini, C.; Kovac, B.; Giovannozzi-Sermanni, G. Production and isolation of chitosan by submerged and solid-state fermentation from Lentinus edodes. Biotechnology and bioengineering 1996, 50, 207-210. https://doi.org/10.1002/bit.260500202. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Herrera, J.F.C.W.S., Synthesis, and Assembly, Second Edition (2nd ed.). CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/b11873. [CrossRef]

- Huq, T.; Khan, A.; Brown, D.; Dhayagude, N.; He, Z.; Ni, Y. Sources, production and commercial applications of fungal chitosan: A review. Journal of Bioresources and Bioproducts 2022, 7, 85-98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobab.2022.01.002. [CrossRef]

- Ssekatawa, K.; Byarugaba, D.K.; Wampande, E.M.; Moja, T.N.; Nxumalo, E.; Maaza, M.; Sackey, J.; Ejobi, F.; Kirabira, J.B. Isolation and characterization of chitosan from Ugandan edible mushrooms, Nile perch scales and banana weevils for biomedical applications. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 4116. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-81880-7. [CrossRef]

- Elson Santiago de, A. Characterization and Properties of Chitosan. In Biotechnology of Biopolymers, Magdy, E., Ed. IntechOpen: Rijeka, 2011, p. Ch. 5. https://doi.org/10.5772/17020. [CrossRef]

- Araújo, D.; Ferreira, I.C.; Torres, C.A.; Neves, L.; Freitas, F. Chitinous polymers: extraction from fungal sources, characterization and processing towards value-added applications. Journal of Chemical Technology & Biotechnology 2020, 95, 1277-1289. https://doi.org/10.1002/jctb.6325. [CrossRef]

- Nwe, N.; Stevens, W.F.; Tokura, S.; Tamura, H. Characterization of chitosan and chitosan–glucan complex extracted from the cell wall of fungus Gongronella butleri USDB 0201 by enzymatic method. Enzyme and Microbial Technology 2008, 42, 242-251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enzmictec.2007.10.001. [CrossRef]

- Martín-López, H.; Pech-Cohuo, S.C.; Herrera-Pool, E.; Medina-Torres, N.; Cuevas-Bernardino, J.C.; Ayora-Talavera, T.; Espinosa-Andrews, H.; Ramos-Díaz, A.; Trombotto, S.; Pacheco, N. Structural and Physicochemical Characterization of Chitosan Obtained by UAE and Its Effect on the Growth Inhibition of Pythium ultimum. In Agriculture, 2020; Vol. 10. [CrossRef]

- Atykyan, N.; Revin, V.; Shutova, V. Raman and FT-IR Spectroscopy investigation the cellulose structural differences from bacteria Gluconacetobacter sucrofermentans during the different regimes of cultivation on a molasses media. AMB Express 2020, 10, 84. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13568-020-01020-8. [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.; Yin, J.-Y.; Nie, S.-P.; Xie, M.-Y. Applications of infrared spectroscopy in polysaccharide structural analysis: Progress, challenge and perspective. Food Chemistry: X 2021, 12, 100168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fochx.2021.100168. [CrossRef]

- Manal G Mahmoud, E.E.K., Mohsen S Asker. Chitin, Chitosan and Glucan, Properties and Applications. World J Agri & Soil Sci. 3(1): 2019. WJASS.MS.ID.000553.

- Fesel, P.H.; Zuccaro, A. β-glucan: Crucial component of the fungal cell wall and elusive MAMP in plants. Fungal Genetics and Biology 2016, 90, 53-60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fgb.2015.12.004. [CrossRef]

- Synytsya, A.; Novak, M. Structural analysis of glucans. Ann Transl Med 2014, 2, 17-17. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2014.02.07. [CrossRef]

- Mesa Ospina, N.; Ospina Alvarez, S.P.; Escobar Sierra, D.M.; Rojas Vahos, D.F.; Zapata Ocampo, P.A.; Ossa Orozco, C.P. Isolation of chitosan from Ganoderma lucidum mushroom for biomedical applications. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine 2015, 26, 135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10856-015-5461-z. [CrossRef]

- Szlek, D.B.; Reynolds, A. M.; and Hubbe, M. A. Hydrophobic molecular treatments of cellulose-based or other polysaccharide barrier layers for sustainable food packaging: A Review. BioResources 2022, 17(2), 3551-3673. [CrossRef]

- Vikele, L.; Laka, M.; Sable, I.; Rozenberga, L.; Grinfelds, U.; Zoldners, J.; Passas, R.; Mauret, E. Effect of chitosan on properties of paper for packaging Cellulose Chem. Technol. 2017, 51 (1-2), 67-73.

- Andze L.; Zoldners, J.; Rozenberga L.; Sable I.; Skute M.; Laka M.; Vecbiskena L.; Andzs M.; Actins A. Effect of molecular chitosan on recovered paper properties described by mathematic model. Cellulose Chem. Technol., 2018, 52 (9-10), 873-881.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).