Submitted:

03 May 2023

Posted:

04 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Bottom sediments

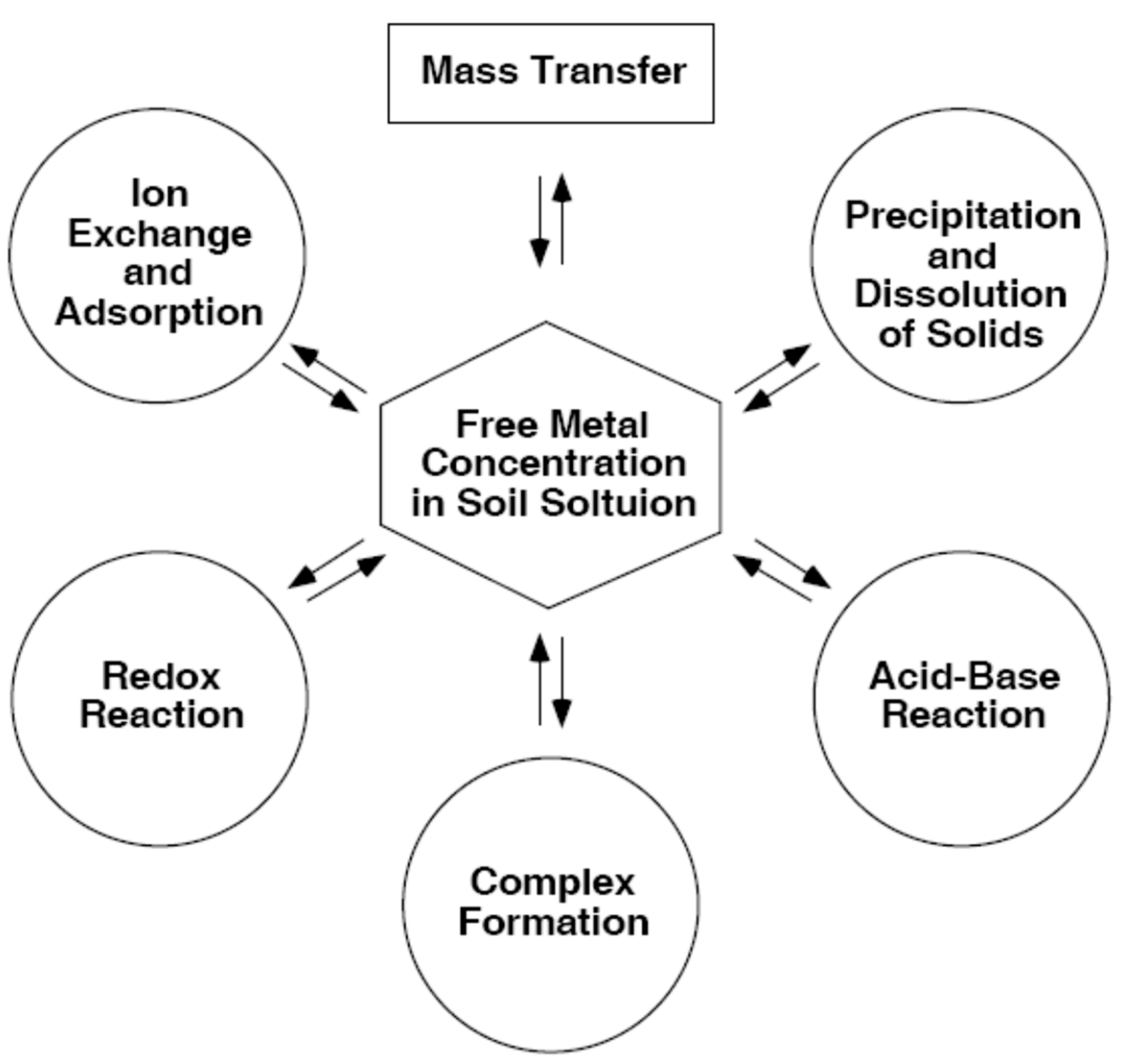

2.1. Mass transfer processes in bottom sediments and soils

2.2. Processes of metal and radionuclide accumulation by bottom sediments

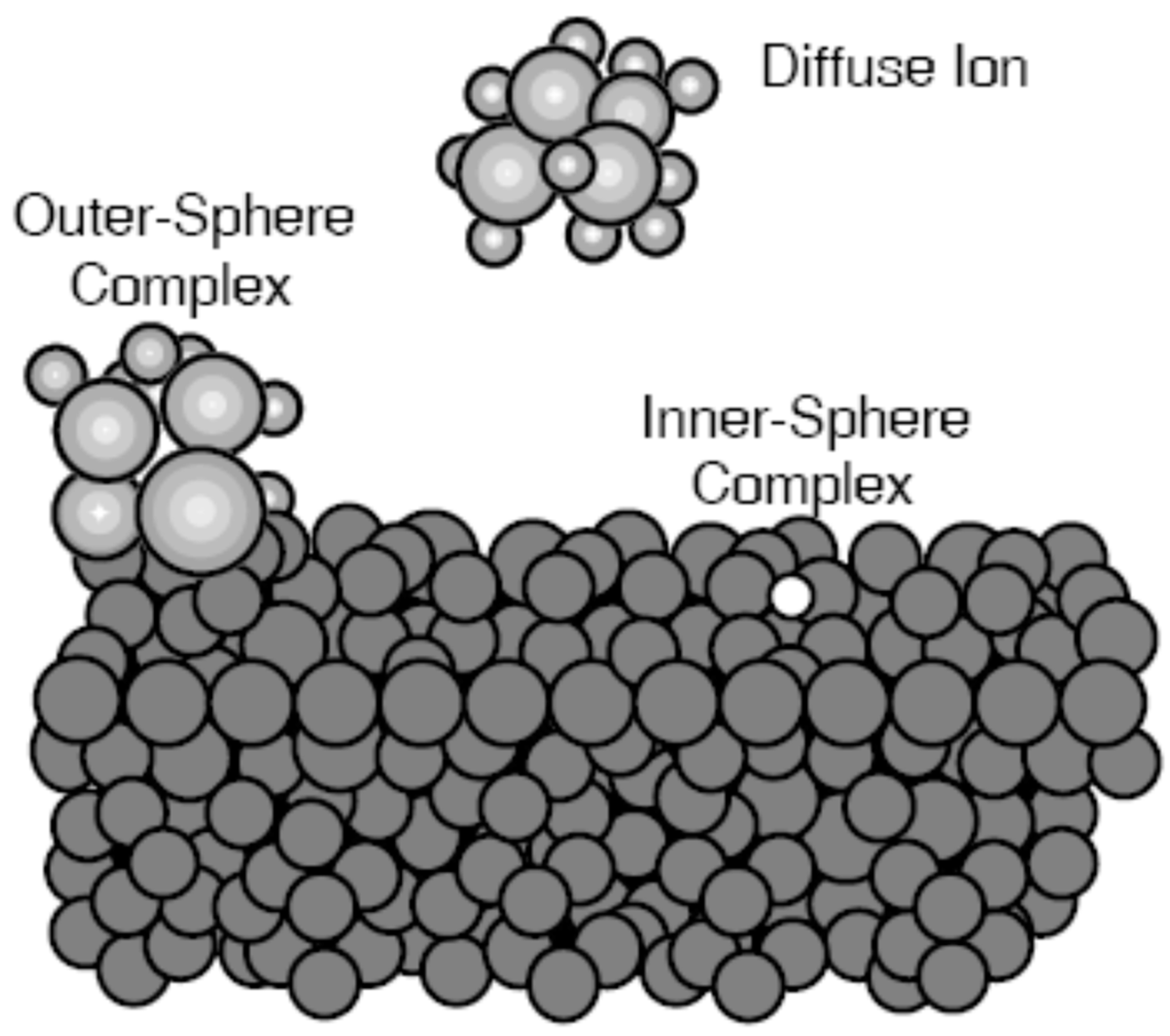

2.3. Reactions proceeding on the particles of bottom sediments

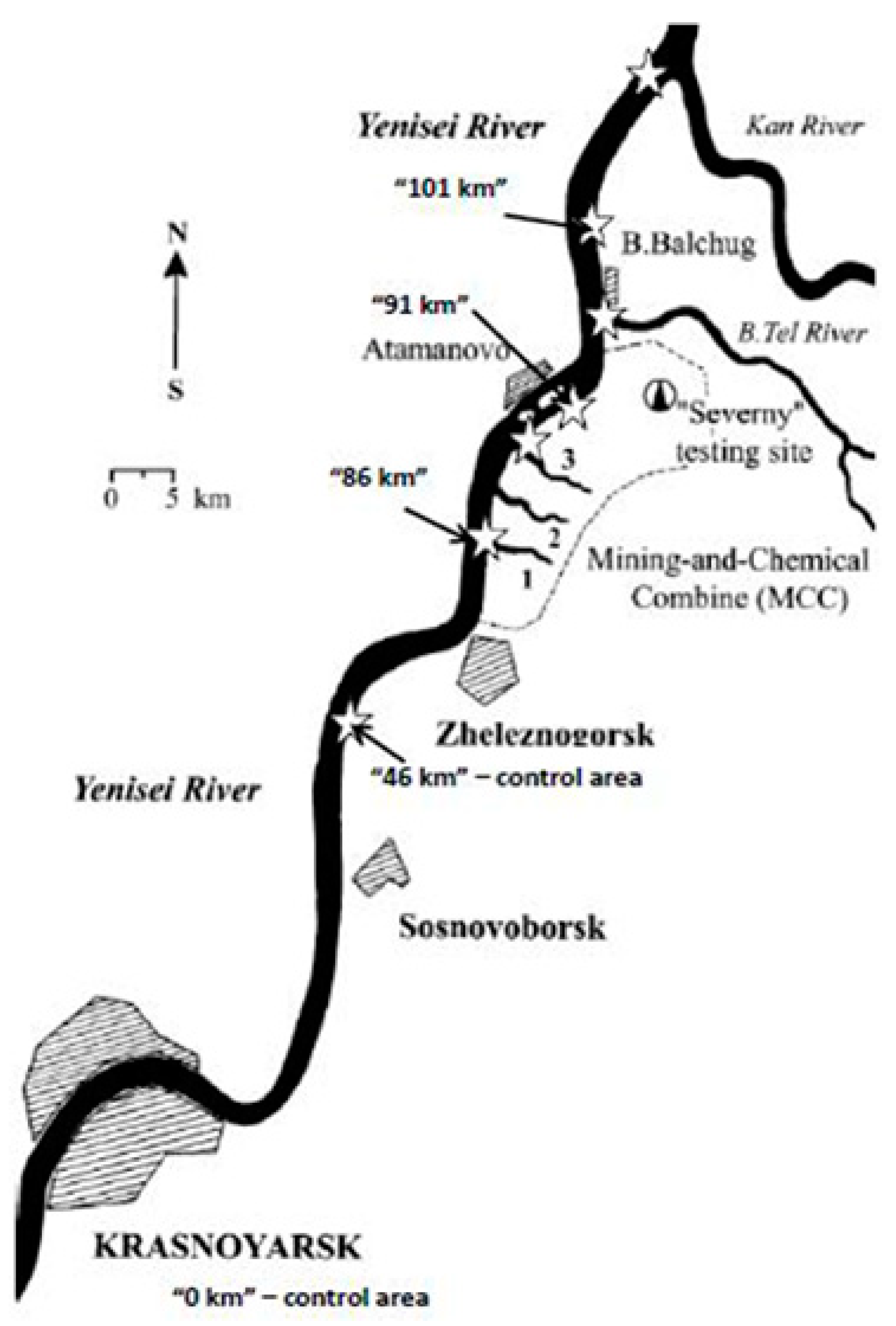

3. Mechanisms of including man-made radionuclides into the structures of the Yenisei River bottom sediments. Migration capability and mass transfer in the water flow of the Yenisei River

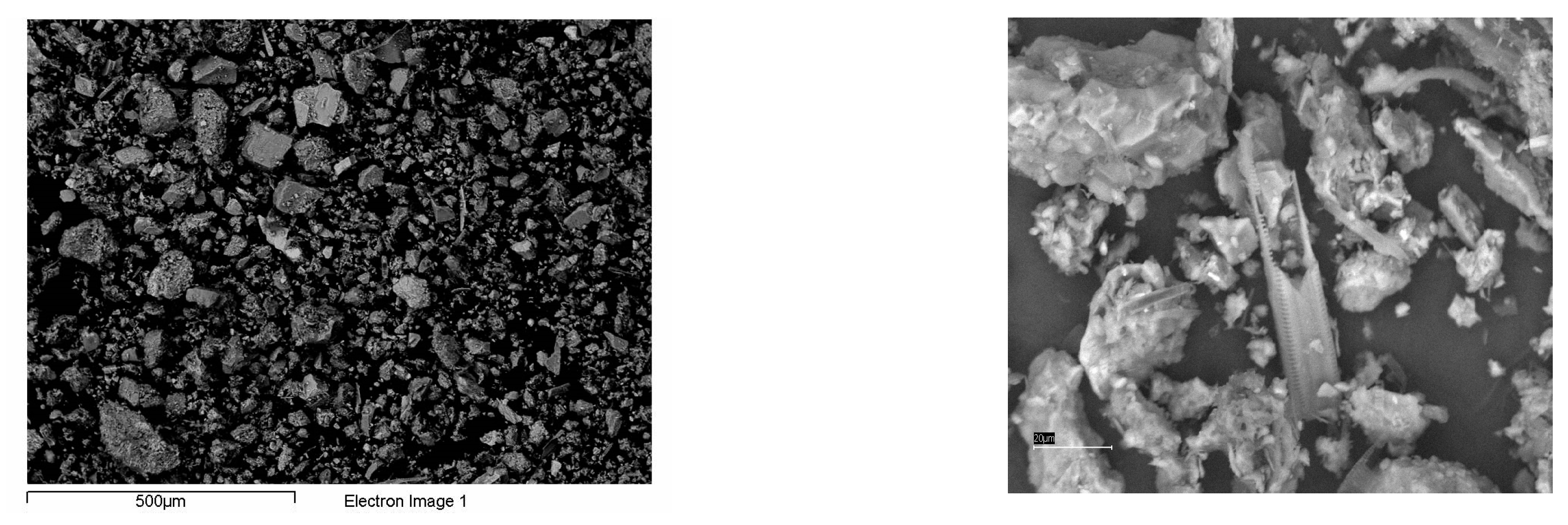

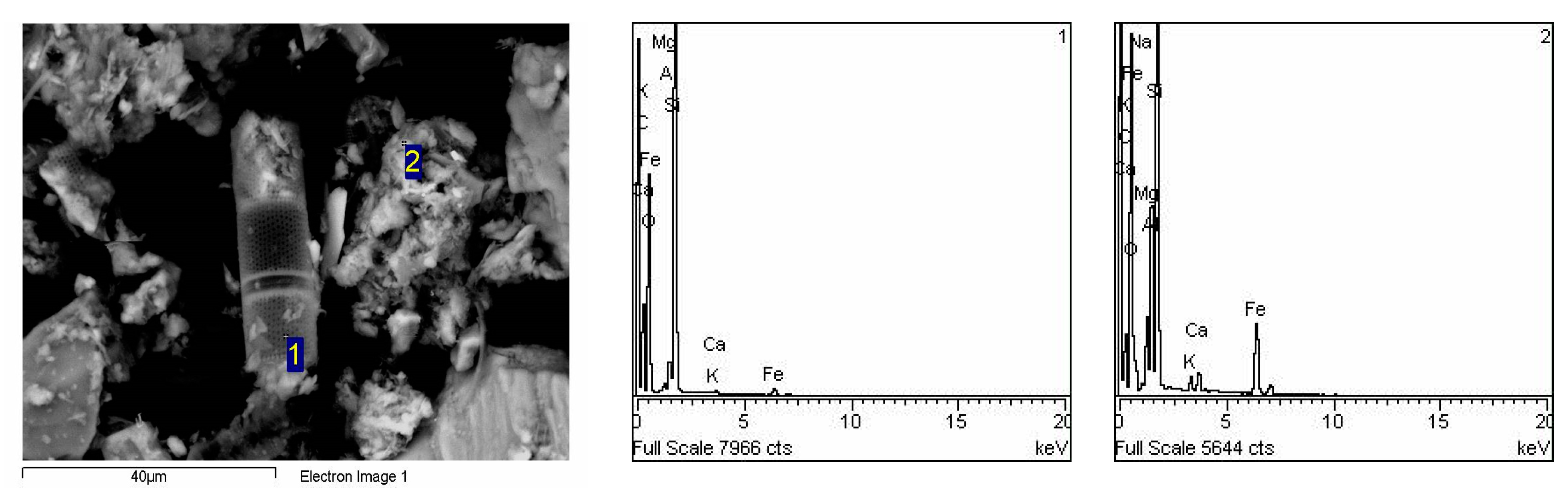

3.1. Geochemical properties of the bottom sediments of the river Yenisei

- Silicon compounds in the majority of bottom sediments and soils create their material basis, playing, thereby, a constitutional role.

- The quantitative distribution of silicon along the soil profile is one of the most important indicators of the occurring processes, and, according to the ratio SiO2:R2O3 or SiO2:Al2O3 the types of weathering profiles are distinguished.

- Many important properties of bottom sediments and flood-plane soils are directly connected with silicon compounds. The cohesion and viscosity of soils, their swelling capacity, capacity for the cation exchange etc. depend on the content and composition of aluminum silicates, i.e clay minerals.

- 1)

- Inhomogenuity of the rock, resulting in:

- 2)

- Absolute accumulation or release of elements due to the transfer of their compounds in the geologic profile and (or)

- 3)

- Relative accumulation (release) of elements due to the release (accumulation) of other chemical substances in the given layer.

4. Conclusion

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- https://www.epa.ie/our-services/monitoring--assessment/waste/chemicals/ (accessed on 15.03.2023).

- https://www.epa.ie/our-services/monitoring--assessment/radiation/# (accessed on 15.03.2023).

- Hupfer, M.; Kleeberg, A. State and pollution of freshwater ecosystems - Warning signals of a changing environment. Global Change: Enough water for all? In: Lozán, J. L., H. Grassl, P. Hupfer, L.Menzel & C.-D. Schönwiese. Wissenschaftliche Auswertungen, Hamburg. 2007, 384 S.

- Ali, H.; Khan, E. Environmental chemistry in the twenty-first century. Environmental Chemistry Letters. 2017, 15(2), 329–346. Contaminated Sediment Management Strategy Forum; Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Water: Washington, DC, USA, 1992, 215 p.

- Quemerais, B.; Lum, K. R.; Lemieux, C. Concentrations and transport of trace metals in the St. Lawrence River. Aquat. Sci. 1996, 58, 52–68. [CrossRef]

- Schafer, J.; Blanc, G.; Audry, S. et al. Mercury in the Lot-Garonne River system (France): Sources, fluxes and anthropogenic component. Appl. Geochem. 2006, 21, 515–527. [CrossRef]

- Moatar, F.; Person, G.; Meybeck, M. et al. The influence of contrasting suspended particulate matter transport regimes on the bias and precision of flux estimates. Sci. Total Environ. 2006, 370, 515–531.

- Azadi, N. Ali; Mansouri, B.; Spada, L.; Sinkakarimi, M. H.; Hamesadeghi, Y.; Mansouri, A. Contamination of lead (Pb) in the coastal sediments of north and south of Iran: a review study. Chemistry and Ecology. 2018, 34(9), 884–900. [CrossRef]

- Marais, B. N.; Brischke, Ch.; Militz, H. Wood durability in terrestrial and aquatic environments – A review of biotic and abiotic influence factors. Wood material science and Engineering. 2020, 17(1), 2-24. [CrossRef]

- Franklin J. Mapping species distributions: spatial inference and prediction. (Cambridge University Press, 2009).

- Wisz M. S. Julien Pottier, W Daniel Kissling, Loïc Pellissier, et al. The role of biotic interactions in shaping distributions and realised assemblages of species: implications for species distribution modelling. Biological Reviews 88, 15–30 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Fôrstner, U.; Wittman, G.T.W. Metal Pollution in the Aquatic Environment (2nd edn). Springer Verlag, Berlin, 1983.

- Abril, J.M.; Fraga, E. Some physical and Chemical features of the variability of Kd distribution coefficient for radionuclides. J. Environ.Radioact. 1996, 30(3), 253-270. [CrossRef]

- C. Duvert, N. Gratiot, J. N´emery, A. Burgos, and O. Navratil Sub-daily variability of suspended sediment fluxes in small mountainous catchments – implications for community-based river monitoring. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss. 2010, 7, 8233–8263.

- Budko, D.F.; Demina, L.L.; Travkina, A.V.; Starodymova, D.P.; Alekseeva, T.N. The Features of Distribution of Chemical Elements, including Heavy Metals and Cs-137, in Surface Sediments of the Barents, Kara, Laptev and East Siberian Seas. Minerals. 2022, 12, 328. [CrossRef]

- Turekian, K.K.; Wedepohl, K.H. Distribution of the elements in some major units of the earth’s crust. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 1961, 72, 175–182. [CrossRef]

- Davidson, C.; Ure, A. Chemical Speciation in the Environment. Wiley-Blackwell; 2 edition, 2001. 480 p.

- Logvinenko, N.V. Petrography of sedimentary rocks. M.: Higher. school 3rd ed., 1984. 416 p. (in Russian).

- Alloway, B. J. Sources of heavy metals and metalloids in soils. In: Heavy Metals in Soils: Trace Metals and Metalloids in Soils and their Bioavailability, Springer, Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2013, p. 11–50.

- Bondareva, L. Regularities of distribution of radionuclides in the ecosystem of the Yenisei River. Thesis of the Doctorate Degree, Moscow State University, Moscow, 2013, 368 p. (accessed on 15.03.2023). (in Russian).

- Shvanov, V. N.; Frolov, V. T.; Sergeeva, E. I. et al. Systematics and classification of sedimentary rocks and their taxes. St. Petersburg: Nedra, 1998, 352 p. (in Russian).

- Gitelson, I.I.; Abrosov, N.S.; Gladyshev, M.I. The main hydrological and hydrobiological characteristics of the Yenisei River. In book: Transport of carbon and minerals in major world rivers, lakes and estuaries. Part 5. Degens, E.T.; Kempe, S.; Naidu, A.S.; Mitt. Geol.-Palãont. Inst. Univ. Hamburg Heft. 1988, 66, 43-46.

- Sposito, G. The Chemistry of Soils. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1989.

- Van Olphen, H. Clay Mineralogy, An Introduction to Clay Colloid Chemistry. John Wiley & Sons, 1977.

- Yashin, I.M.; Shishov, L.L.; Raskatov, V.A. Methodology and experience in studying the migration of substances. Moscow, MSHA. 2001. 173 p.

- Machate, O., Schmeller, Dirk S.; Schulze, T.; Brack, W. Review: mountain lakes as freshwater resources at risk from chemical pollution. Environmental Sciences Europe, 2023, 35 (3), 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Orlov, D.S. Humic substances in the biosphere. Moscow, Nauka, 1993, 238 p. (in Russian).

- Orlov, D.S. Soil chemistry. Moscow, MGU. 1992, 487 p. (in Russian).

- Abrams, I.M., Organic Fouling of ion Exchange Resins, in: Pawlowski, L. (Ed.), Physicochemical Methods for Water and Wastewater Treatment, Studies in Environmental Science. Elsevier, 1982. pp. 213–224. [CrossRef]

- Baken, S.; Degryse, F.; Verheyen, L.; Merckx, R.; Smolders, E. Metal Complexation Properties of Freshwater Dissolved Organic Matter Are Explained by Its Aromaticity and by Anthropogenic Ligands. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 2584–2590. 1009. [CrossRef]

- Buffle, J.; Altmann, R.S.; Filella, M.; Tessier, A. Complexation by natural heterogeneous compounds: site occupation distribution functions, a normalized description of metal complexation. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1990, 54, 1535–1553. [CrossRef]

- Perelman, A.I. Geochemistry of the landscape. Moscow, MGU, 1975, 342 p. (in Russian).

- Richter, D. D. Humanity’s transformation of earth’s soil: pedology’s new frontier. Soil Sci. 2007, 172, 957−967.

- USDA. Keys to Soil Taxonomy by Soil Survey Staff, 12th ed.; United States Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service: Washington, DC, 2014; https://www.nrcs. usda.gov/wps/PA_NRCSConsumption/download?cid= stelprdb1252094&ext=pdf (accessed on 07.04.2023).

- United States Geological Survey, 2011. Mineral commodity summaries. Reston, VA: http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/mcs/2011/mcs2011.pdf. (accessed on 07.04.2023).

- Yaron, B.; Dror, I.; Berkowitz, B. Soil-Subsurface Change. Berlin, Heidelberg. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. 2012. (also available at http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978- 3-642-24387-5) (accessed on 07.04.2023).

- Wuana, R.A.; Okieimen, F.E. Heavy Metals in Contaminated Soils: A Review of Sources, Chemistry, Risks and Best Available Strategies for Remediation. ISRN Ecology, 2011: 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Barange, M.; Field, J.G.; Harris, R.P.; Eileen E.; Hofmann, E.E.; Perry R.I.; Werner, F. Marine ecosystems and global change. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2010. p. 464.

- Harper, M.P.; Davison, W.; Zhang, H. Kinetics of metal exchange between solids and solutions in sediments and soils. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 1998, 62, 2757-2770. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Geng, K.; Wang, C.; Wu, X.; Wei, C. Impact of Fulvic Acid and Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidan Inoculum Amount on the Formation of Secondary Iron Minerals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4736. [CrossRef]

- Abhijit, D.; Kumar, S. P.; Yogesh, C. S. Metallic contamination of global river sediments and latest developments for their remediation. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 298, 113827. [CrossRef]

- Bashir, I.; Lone, F. A.; Bhat, R. A.; Mir, S. A.; Dar, Z. A.; Dar, S. A. Concerns and Threats of Contamination on Aquatic Ecosystems. Bioremediation and Biotechnology. 2020, 27, 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Aranganathan, L.; Rajasree, S. R. R.; Govindaraju, K.; Kumar, S. S.; Gayathri, S.; Remya, R. R.; et al. Spectral and microscopic analysis of fulvic acids isolated from marine fish waste and sugarcane bagasse co-compost. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2020, 29, 101762. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Orellana, J.; Pates, J.M.; Masque, P. et al. Distribution of artificial radionuclides in deep sediments of the Mediterranean Sea. Sc. Total Environ. 2009, 407, 887-898. [CrossRef]

- Harper, M.P.; Davison, W.; Zhang, H. Kinetics of metal exchange between solids and solutions in sediments and soils. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 1998, 62, 2757-2770. [CrossRef]

- Bragea, M.; Perju, D.; Brusturean, A. et al. Influence of distribution coefficients on the transfer of radionuclides from water to geological formation. Buletinul Stiitific al Universitatii “Politehnica” din Timisoara. Seria Chimie Si Ingineria Mediului. Chem. Bull. “Politehnica” Univ. (Timisoara). 2008, 53, 1-2.

- Bryan, G.W., Langston, W.J. Bioavailability, accumulation and effects of heavy metals in sediments with special reference to United Kingdom estuaries: a review. Environ Pollut. 1992, 76(2), 89–131. [CrossRef]

- Orlov, D.S.; Sadovnikova, L.K.; Sukhanova, N.I. Soil chemistry. Moscow, Higher School, 2005, 558 p. (in Russian).

- Mattigod, S.V.; Sposito, G.; Page, A.L. Factors affecting of trace metals in soils. In book: Chemistry in the soil environment. Am. Soc. Agron. Madison Wis. 1981, p. 203-221.

- Stevenson, F.J. Humus Chemistry: genesis, composition, reactions. 2nd ed. – New York: Wiley. 1994, 496 p.

- Uspenskaya, E.V.; Syroeshkin, A.V.; Pleteneva, T.V.; Kazimova, I.V.; Grebennikova, T.V.; Fedyakina, I.T.; Lebedeva, V.V.; Latyshev, O.E.; Eliseeva, O.V.; Larichev, V.F.; et al. Nanodispersions of Polyelectrolytes Based on Humic Substances: Isolation, Physico-Chemical Characterization and Evaluation of Biological Activity. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1954. [CrossRef]

- YAO, Wen-bin; HUANG, Lei; YANG, Zhi-hui; ZHAO, Fei-ping. Effects of organic acids on heavy metal release or immobilization in contaminated soil. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China. 2022, 32, 1277−1289. [CrossRef]

- Aromaa, H.; Voutilainen, M.; Ikonen, J.; Yli-Kaila, M.; Poteri, A.; Siitari-Kauppi, M. Through diffusion experiments to study the diffusion and sorption of HTO, 36Cl, 133Ba and 134Cs in crystalline rock. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2019, 222,101-111. [CrossRef]

- Boomer, D.W.; Powell, M.J. Determination of uranium in environmental samples using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Analytical Chemistry. 1987, 59, 2810–2813. [CrossRef]

- Bostick, W.D. et al. Use of apatite and bone char for the removal of soluble radionuclides in authentic and simulated DOE groundwater. Advances in Environmental Research. 2000, 3 (4), 488–498.

- Wauters, J.; Sweeck, L.; Valcke, E.; Elsen A.; Cremers A. Availability of radiocaesium in soils: a new methodology. SPRI-CEC Meeting The dynamic behaviour of radionuclides in forests, May 18-22 1992, Stockholm, Sweden, 1992.

- Mattigod S.V., Sposito G., Page A.L. Factors affecting of trace metals in soils. In Chemistry in the soil environment // Am. Soc. Agron. Madison Wis. – 1981. – P. 203-221.

- Suazo-Hernández, J.; Arancibia-Miranda, N.; Mlih, R.; Cáceres-Jensen, L.; Bolan, N.; Mora, M.d.l.L. Impact on Some Soil Physical and Chemical Properties Caused by Metal and Metallic Oxide Engineered Nanoparticles: A Review. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 572. [CrossRef]

- Bermond, A.; Yousfi, I.; Ghestem, J.P. Kinetic approach to the chemical speciation of trace metals in soils. Analyst, 1998, 123, 785-789. [CrossRef]

- Cances, B.; Ponthieu, M.; Castres-Rouelle, M.; Aubry, E.; Benedetti, M.F. 2003. Metal ions speciation in a soil and its solution: experimental data and model results. Geoderma, 2003, 113, 341-355. [CrossRef]

- Rolland, B. Transfert des radionucléides artificiels par voie fluviale : conséquences sur les stocks sédimentaires rhodaniens et les exports vers la Méditerranée. Thèse, Université Paul Cézanne d'Aix-Marseille, 2006, 243p.

- Meyers, S. K., Deng S., Basta N. T., et al. Long-Term Explosive Contamination in Soil: Effects on Soil Microbial Community and Bioremediation. Soil and Sediment Contamination. An International Journal. 2007, 16, 61-77. [CrossRef]

- Jenne, E.A. Controls on Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu and Zn Concentrations in Soils and Water: The Significant Role of Hydrous Mn and Fe Oxides. Advances Chemistry Series. 1968, 73, 337-388.

- Santillan-Medrano, J.; Jurinak, J.J. The chemistry of lead and cadmium in soil: Solid phase formation. Soil Sci. Soc. Amer. Proc. 1975, 39, 851-856. [CrossRef]

- McLean, Joan E.; Bledsoe, Bert E. Behavior of Metals in Soils. United States Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Research and Development, EPA/540/S-92/018, October 1992.

- McBride, M. B.; Blasiak, J. J. Zinc and copper solubility as a function of pH in an acidic soil. Soil Sci.Soc. Am. J. 1979, 43, 866-870. [CrossRef]

- McBride, M. B. Chemisorption of Cd2+ on calcite surfaces. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1980, 44, 26-28. [CrossRef]

- Jurinak, J. J.; Bauer, N. Thermodynamics of zinc adsorption on calcite, colomite, and magnesite-type minerals. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. Proc. 1956, 20, 466-471. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, Y.M.; Lion, L. W. Formation of biogenic manganese oxides and their influence on the scavenging of toxic trace metals”. In book: Geochemical and Hydrological Reactivity of Heavy Metals in Soils. Ed by: H.M. Selim and W.L. Kingerly, Eds., CRC Press. 2003.

- Nelson, Y.M., Lion, L. W., Shuler, M.L. et al. Lead adsorption to mixtures of biogenic Mn oxides and Fe oxides. Environmental Science and Technology. 2002, 36, 421-425.

- Nelson, Y.M.; Lion, L.W.; Ghiorse, W.C. Production of biogenic Mn oxides by Leptothrix discophora SS-1 in a chemically defined growth medium and evaluation of their Pb adsorption characteristics. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 65, 175-180. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, Y. M. Modeling toxic metal adsorption in aquatic environments. Presented to the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Institute of Geochemistry, Guangzhou, China, Sept. 20, 1999 and at Jilin University Dept. of Environmental Science, Changchun, China, Sept. 15, 1999.

- Silviera, D. J.; Sommers, L. E. Extractability of copper, zinc, cadmium, and lead in soils incubated with sewage sludge. J. Environ. Qual. 1977, 6, 47-52. [CrossRef]

- Latterell, J. J.; Dowdy, R. H.; Larson W. E. Correlation of extractable metals and metal uptake of snap beans grown on soil amended with sewage sludge. J. Environ. Qual. 1978, 7, 435-440. [CrossRef]

- Raewyn, M. Town and Montserrat Filella. Size fractionation of trace metal species in freshwaters: implications for understanding their behaviour and fate. Reviews in Environmental Science and Biotechnology. 2002, 1 (4), 277-297.

- Comber, S.D.W.; Gunn, A.M. Heavy metals entering sewage treatment works from domestic sources. J.CIWEM. 1996, 10, 137-142. [CrossRef]

- Millward, G.E.; Liu, Y.P. Modelling metal desorption kinetics in estuaries. Science of The Total Environment. 2003, 314-316, 613-623. [CrossRef]

- Hatje, V.; Payne, T.E.; Hill, D.M. Kinetics of trace element uptake and release by particles in estuarine waters: effects of pH, salinity, and particle loading. Environment International, 2003, 29, 619–629. [CrossRef]

- Francois, L.L.; Kester, Dana R. Voltammetric determination of the complexation parameters of zinc in marine and estuarine waters. Marine Chemistry. 1991, 33, 71-90.

- Titley, J.G.; Glegg, G.A.; Glasson, D.R. et al. Surface areas and porosities of particulate matter in turbid estuaries. Continental Shelf Research. 1987, 7, 1363-1366. [CrossRef]

- Jannasch, H.W.; Honeyman, B.D.; Balistrieri, L.S. et al. Kinetics of trace element uptake by marine particles. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1988, 52, 567–77. [CrossRef]

- Honeyman, B.D.; Santschi, P.H. Metals in aquatic systems. Environ Sci Technol. 1988, 22, 862–871. [CrossRef]

- Honeyman, B.D.; Santschi, P.H. A Brownian-pumping model for oceanic trace metal scavenging: evidence from Th isotopes. J Mar Res. 1989, 47, 951–992. [CrossRef]

- McNaught, A.D.; Wilkinson, A. Compendium of Chemical Terminology – IUPAC Recommendations 2nd Edn. Oxford: Blackwell Science Ltd, 1997.

- OECD Nuclear Energy Agency. – 1999. Speciation Techniques and Facilities for Radioactive Materials at Synchrotron Light Sources, Paris: OECD Nuclear Energy Agency. Workshop Proceedings from the 1st Euroconference and NEA Workshop on Speciation Techniques and Facilities for Radioactive Materials at Synchrotron Light Sources, Grenoble, 1998.

- Vakulovski, S.M.; Kryshev, I.I.; Nikitin, A.I.; Savitski, Yu.V.; Malyshev, S.V.; Tertyshnik, E.G. Radioactive contamination of the Enisey-river. J. Environ.Radioactivity, 1995, 29(3), 225–236.

- Vakulovsky, S.M.; Tertyshnik, E.G.; Kabanov A. I. Radionuclide transport in the Enisei River. Atomic Energy, 2008, 105 (5), 367–375.

- Sukhorukov, F.V., Degermendzhy, A.G., Belolipetsky, V.M., et al. Distribution and Migration of Radionuclides in the Yenisei Plain. Publ. House of SB RAS “Geo”, Novosibirsk, 2004, 286 p.

- Bondareva, L.; Rakitskii, V.; Tananaev, I. The behavior of natural and artificial radionuclides in a River System: The Yenisei River, Russia as a case study. In book: Water quality. Ed. by Hlanganani Tutu, 2017, ISBN: 978-953-2882-3, 361-375.

- Bondareva, L. The relationship of mineral and geochemical composition to artificial radionuclide partitioning in Yenisei River sediments downstream from Krasnoyarsk. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment. 2012, 184 (6), 3831–3847. [CrossRef]

- Drever, J. I. The geochemisty of natural waters. Prentice Hall. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, 1997, 437 p.

- Garrels, R. M.; Christ, C. L. Solutions, Minerals, and Equilibria: Harper and Row. New York, 1995, 450 p.

- Sparks, D. L. Environmental Soil Chemistry. Academic Press. San Diego,USA, 2003, 267 p.

- Baeyens, W.; Monteny, F.; Leermakers, M. et al. Evalution of sequential extractions on dry and wet sediments. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2003, 376, 890–901. [CrossRef]

- Bondareva, L.; Fedorova, N. The effect of humic substances on metal migration at the border of sediment and water flow. Environmental Research, 2020, 109985. [CrossRef]

- Pavlotskaya, F.I. Migration of radioactive products of global fallout in soils. Moscow, Atomizdat, 1974, 216 p. (in Russian).

|

Fraction |

Radionuclides, Bq·kg-1 (% from the total content) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60Сo | 137Cs | 152Eu | 241Am | |||||

| At | Е | At | Е | At | Е | At | Е | |

| I, exchangeable | 7 ± 1,4 (1,3 ± 0,3) |

3,7 ± 0,7 (2,2 ± 0,4) |

26 ± 3 (1,1 ± 0,1) |

18 ± 1,7 (3,8 ± 0,4) |

16 ± 3 (1,4 ± 0,3) |

< MDA | < MDA | < MDA |

| II, carbonates | 11 ± 3 (3,0 ± 0,8) |

9,7 ± 0,9 (5,8 ± 0,5) |

15 ± 3 (0,6 ± 0,1) |

9,3 ± 1 (1,9 ± 0,2) |

24 ± 3 (2,1 ± 0,6) |

22 ± 1 (7,0 ± 0,3) |

4 ± 1 (7 ± 2) |

15 ± 2 (27 ± 4) |

| III, sesquioxides and hydroxides | 47 ± 4 (8,9 ± 0,8) |

9,7 ± 1,3 (5,8 ± 0,8) |

15 ± 5 (0,6 ± 0,2) |

4,4 ± 1,4 (0,9 ± 0,3) |

171 ± 11 (14,8 ± 0,9) |

20 ± 2 (6,4 ± 0,6) |

4 ± 1 (7 ± 2) |

6,6 ± 0,4 (12 ± 1) |

| IV, organic matter | 61 ± 4 (11,6 ± 0,8) |

30 ± 1 (18 ± 1) |

80 ± 4 (3,3 ± 0,2) |

41 ± 4 (8,6 ± 0,8) |

465 ± 11 (40 ± 1) |

214 ± 6 (68 ± 2) |

19 ± 4 (34 ± 7) |

25 ± 3 (46 ± 6) |

| V, amorphous silicates | 30 ± 3 (5,7 ± 0,6) |

< MDA | 23 ± 4 (0,9 ± 0,2) |

3 ± 1 (0,7 ± 0,2) |

< MDA | < MDA | < MDA | < MDA |

| VI, undecomposed residue | 371 ± 14 (70 ± 3) |

115 ± 2 (68 ± 1) |

2284 ± 122 (93,5 ± 5) |

410 ± 29 (84 ± 6) |

481 ± 13 (41,7 ± 1) |

58 ± 3 (18,6 ± 0,9) |

29 ± 4 (52 ± 7) |

8,1 ± 1,1 (15 ± 2) |

| Initial content |

527 ± 42 (100) |

168 ± 19 (100) |

2443 ± 147 (100) |

486 ± 44 (100) |

1157 ± 46 (100) |

314 ± 13 (100) |

56 ± 7 (100) |

55 ± 8 (100) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).